ABSTRACT

The research objective was to analyse the representation of the US presidential election in selected programmes of the Czech Radio and assess to what extent it met the requirements of public service media. Five programmes were analysed by quantitative content analysis and qualitative interpretive approaches, mainly discourse analysis. This text presents key findings of the research that are relevant for the study of political communication in the context of media studies, news discourse analysis and public service broadcasting. The dominant topic covered in pre-election period was mainly the representation related to pre-election campaign of two main presidential candidates and information on the course of pre-election polling. In post-election period, the election results and possible consequences of Donald Trump victory were mainly thematised. A considerable part of the representation of the election even in pre-election period was related to the characteristics, activities, opinions, etc. of one of the candidates only (namely D. Trump), which points out a significant bias in the overall media representation what is alarming as the broadcasting of public service media was analysed.

Introduction to the research

What information did Czech Radio provide on the US presidential election of 2016 in its broadcasts? The research objective was to analyse the representation of the US presidential election in selected programmes on Czech Radio and assess to what extent it met the requirements of public service media (in accordance with Act 484/1991 Coll. and Czech Radio broadcasting Code of Practice).Footnote1 This text presents key research findings which are relevant for the study of political communication in the context of media studies and news discourse analysis.Footnote2

The analysis is based on media constructionism (Luhmann Citation2000; Schulz Citation2000). Media content reflects and spreads dominant ideologies, values, standards and attitudes and interests of groups/persons who have access to power in society (Cottle Citation1997). Media contribute in this fashion to the reproduction of the social status quo. News reporting is not an exemption and the authors’ world views can be identified in it or the content might also reflect the perspectives of the owners of the medium. This is why, according to Hall, the most important question is not what reality is created by the media but whose message is communicated (Hall Citation1997, 228).

There are topics and events that are covered more frequently and repeatedly by the media, while others are neglected.Footnote3 McCombs and Shaw (Citation1991), in their theory of agenda-setting, revealed how media draw the attention of their audience to the themes selected by them. The main effect of agenda-setting is the shaping of public opinion,Footnote4 i.e., directing attention at highly mediated topics. In light of the fact that the majority of objects can be described by a significant number of characteristics/attributes, it is important which ones are specifically selected. Along with the selection of events (phenomena/persons/themes) covered, there is also the selection of the attributes used for their presentation and specification. In this way, media suggest to the recipients not only what they are supposed to think about but also in which categories.

The approach used to analyse framing is derived from the theory of agenda-setting,Footnote5 i.e., the topics or frames in which journalists represent particular events. Several concepts of framing exist. Their difference lies mainly in whether the frames relate to individual perception or whether they are considered part of social discourse. McCombs (Citation2004) views a frame as a special complex kind of attribute of an object that is characterised by a dominant perspective which is used to deal with the object. Maher (Citation2003) opposes him and argues that a frame is a wider concept, which directly determines and structures the object. Reese (Citation2003, 11) comprehends frames as organisational principles shared in society and permanent in time, operating symbolically to substantially structure the social world. While framing makes certain aspects more important, others are deliberately ignored. In this way, framing is a manifestation of social power and reflects the dominant order. Frames anchor the message, suggesting and directing its possible decoding by recipients. According to the frequently referred – to Entman (Citation1993, 52), framing means: ‘to select some of the aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in the communicated text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described’. Key questions raised in relation to the above approaches focus on how the US presidential electionFootnote6 was framed in selected programmes of Czech Radio and which attributes were assigned to and systematically mentioned with the individual candidates.

Much has been publish concerning not only the Trump presidential candidacy and politics but also on the Trump’s personality. Studies had been published analysing the political uncertainty during U.S. presidential elections affecting stock market volatility (Goodell and Vähämaa Citation2013). Texts that show Trump's character features correspond with psychopathic or anti-social personality disorder definitions of American Psychiatric Association (Ashcroft Citation2016). Analysis of word usage (e.g., words per sentence, words longer 6 letters, Twitter usage) and style of speech in early campaign speeches which describe his populist communication style as grandiose, dynamic and informal (Ahmadian, Azarshahi, and Paulhus Citation2017). However, Argina (Citation2018) found out, that frequency of presupposition triggers use by Clinton and Trump in their first campaign speech was not significantly different. But while Clinton used lexically, factive and pronoun more frequently iterative lexical trigger was more frequently used by Trump. Gökariksel and Smith (Citation2016, 1) argue that: ‘Trump's rhetoric and performance of white masculinity as formative of a fascist body politics that seeks to preserve white male supremacy’. Gounari and Morelock (Citation2018) analysed Trump's tweets as an instrument of discourse production, reorientation and social control and Twitter as a dissemination platform which is used to promote his brand of authoritarian, corporate capitalism and reactionary politics.

There are also articles discussing the change of the media and the decline of trust to them in so called Trump’s era, especially in the context of fake news, alternative media and post facts society. E.g., Pickard (Citation2016) argues that ongoing changes and news media failure made American journalism in crisis which threatens democratic self-governance. Jutel (Citation2017) characterises Trump's populism as the culmination of a media politics of jouissance.

Another analysed topic is how media can help voters with their decision making during campaigns (Gregor Citation2016). However, few texts could be find on representation of Trump as president in media, none dealing with public service media. It is questionable to compare the results of this case study with other researches conducted in country with different media system as media could vary from the commercial one, to the public service and even the state one. It could be possible to compare the results with the analogical study analysing Trump’s representation in the media from the central European region, e.g., some of the V4 countries, but there is no such study published yet.

Key events of the presidential pre-election campaign in the autumn of 2016

Media are key instruments in political communication and essential in all pre-election campaigns. Potential aspirants to a post in politics strive to win favour with the electorate and use it to obtain decision-making powers. A publication of the Institute for Political Marketing American Election 2016 (2017) analyses the presidential campaign from various points of view. The events selected here are those that provide an idea concerning the development in the pre-election period in autumn 2016 for a further understanding of the conducted analysis of broadcasting during the culmination of the election campaign:

there were more candidatesFootnote7 to the post of US president than the two most mediated ones Hillary Clinton (further HC) and Donald Trump (further DT) in 2016;

HC's physical collapse during the memorial service on 11 September 2016;

media thematizing DT's tax evasion and his non-public tax returns;

the incumbent president Barack Obama and the First Lady showing active support for HC;

armed attacks, considered to be terrorist, occurred in New York and New Jersey;

the first presidential debate took place on 26 September in which HC received a more favourable rating. It was believed that she would have won if the election had taken place at the beginning of October;

support for other candidates gradually diminished (also among young voters);

a recording was released in which DT admitted sexual assaults of women and his popularity and his polling dropped;

on 9 October, the second presidential debate took place (with a much lower viewer ratings) in which DT stated that he would place HC in prison if elected;

in the third TV debate, DT denounced all the allegations of sexual harassment as fabricated;

in November, HC still came out as the winner in polls;

eleven days before the election, James Comey, FBI director announced that further e-mails of HC were being investigated, which meant the case of her e-mail correspondence was open again (on 5 November 2016 he stated that the e-mails did not reveal any new information and that no new charges would be brought against HC);

DT's victory was one of the narrowest election results in history in terms of the number of votes and electoral votes. (Institute for Political Marketing Citation2017)

Study methodology

The text focuses on an analysis of media representation of the US presidential election on selected programmes of Czech Radio (further CRo) broadcasts. The analysis was aimed at identification of the following points: (i) significant characteristics of the event thematisationFootnote8; (ii) methods of constructing the representation of the topic – the narrativeFootnote9 methods used for the representation of a specific event/aspect and for what purpose; (iii) specific methods of constructing the representation with regard to the individual participants/events – over-represented or under-represented phenomena/attributes. These were the key areas of the qualitative research. The quantitative work was carried out through a set of partial research questions: How much space was granted to the theme of the election and the candidates in the analysed programmes? How were both candidates represented and framed? Which themes were the US presidential election and both candidates linked to? What kind of speakers were quoted?

The following programmes were selected for the analysis of the broadcasting of CRo Radiozurnal and CRo Plus: ‘Main News – Interviews and Commentaries’, ‘Opinions and Arguments’, ‘The World in 20 Minutes’, ‘Reading from the International Press’, ‘The Day According To … ’. These are the key programmes of Czech radio focused on news analysis, news commentary and foreign politics. The selection contained in total 75 episodes of the programmes broadcast from 31 October 2016.Footnote10 Although the sample was selected as intentional and also combined news and documentary, all the analysed programmes revealed similar tendencies in relation to the key findings of the analysis (see below). Our objective was not to describe the representation of the election in the individual episodes of the individual programmes but to capture the more general characteristics and tendencies typical for CRo broadcasting. As saturation was achieved in the qualitative analysis, it can be argued that the obtained findings concerning the information provided on the presidential election in the programmes of CRo are of wider validity.

The unit of the research analysis was one news item; a thematically coherent and clearly distinguishable unit, usually marked by an introduction in the form of the programme presenter's entry, or a signature tune or jingle. For the analysis, triangulation of the research methods was used and both quantitative content analysis (Neuendorf Citation2002), and qualitative methods of textual interpretation (Kronick Citation1997), namely discourse analysisFootnote11 and semiotic analysisFootnote12 were applied. All the programmes were initially listened to in full and thematically relevant research units were identified and transcribed. For the analysis, all the news items were selected that reported on the US presidential election or one of the candidates, including minor references.Footnote13 Coding of all data was carried out by one researcher and potentially unclear cases were consulted with the authors’ team. The initial qualitative analysis for all the sample items included inductive procedures and principles of grounded theory (a sequence of open, selective and axial coding). This process was then repeated for the individual programmes with the aim of testing the obtained findings and, at the same time, disclosing differences between individual programmes and identifying the specific characteristics of the construction and the final form of the representation of the theme in the individual programmes.

Findings from the quantitative analysis

In the analysed programmes, 128 news items referring to the US presidential election were recorded, and also 37 headlines relevant to the topic that were not further processed. The coverage of the topic was uneven, with the event being most frequently mentioned in the news summary programmes: ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ (49 times) and ‘Opinions and Arguments’ broadcasting (39 times).Footnote14

13 hours and 10 minutes of broadcasting time were devoted in total to the topic. These news items took up more than one third of the broadcasting time in some of the programmes (‘Main News – Interviews and Commentaries’ of Radiozurnal, ‘Opinions and Arguments’, ‘The World in Citation20 Minutes’). Most of the news items (77%) appeared as one of the first four pieces in the programme, which indicates the significance that journalists assigned to them.

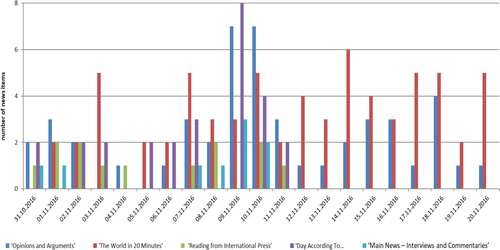

The journalists in CRo tended to cover the topic more frequently in the week following the election date, 7 November, than over the course of the presidential campaign.Footnote15 The question arises as to what extent the frequency of coverage was related to the victory of the given candidate and whether the same attention/broadcasting time would have been granted to him if Hillary Clinton had won the election? ().

Chart 1. Coverage of the US presidential election in the analysed programmes over the examined period.

Note: The programmes ‘Main News’, ‘Reading from the International Press’ and ‘Day According To … ’ were analysed in the period 31 October–11 Nov. 2016 only.

Three quarters (94) of the news presented the theme as the primary one and another one fifth (24 news) as a secondary one.Footnote16 10 news items contained a reference to the US election or the candidates and these were not included in a detailed analysis. The following analyses report on 118 news in total; namely 47 taken from ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ programme, 32 from ‘Opinions and Arguments’, 17 from ‘Day According To … ’, 13 from Reading from the International Press and 9 from the ‘Main News – Interviews and Commentaries’ programme.

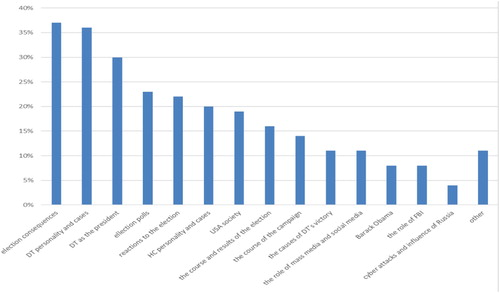

The news explained the different aspects of the presidential election and drew attention to various aspects and events related to the presidential candidates. One fifth (25) of the news covered one frame only.Footnote17 As shown in , the most frequent theme in the analysed programmes of Czech Radio related to the US presidential election were the consequences of the election in general for the U.S.A., Europe and other continents and the possible impact on the situation in international relations, and also the possibility that this candidate's victory might incite the rise of populist parties in Europe. One third (30%) of the news items introduced thoughts on how DT would perform in the role of president and whether he would change his ‘controversial’ and ‘unpredictable’ behaviour, who would be in his government team and the nature of his behaviour during his first speech after being elected president. A considerable proportion of namely these frames are undoubtedly affected by the fact that the election was covered to a great extent mainly in the post-election period.

Chart 2. Themes in the analysed news items related to the US presidential election.

Note: Considering the fact that only a small number of the news items were monothematic, the total of the shown values is higher than the total number of the analysed news.

DT's personality was also distinctively thematized, i.e., information on his activities as a candidate, both negatively tinged (controversial statements, judgments on his un/suitability for the role of US president, etc), and neutral or positive ones (for example, information on DT's career thus far, information about his family, or evaluation of his strengths). News reporting on HC in similar tones (for example, the use of her private e-mail when she was the US Secretary of State) were covered less frequently (on HC in 20% of the news items, on DT in 36%). Approximately every fourth news item (23%) informed on the polls of voting preferences among US citizens. After the election, journalists often focused on why the polls (in which HC was favoured) were ‘wrong’.

When taking into account the events considered essential for the presidential election by the authors from the Institute for Political Marketing (Institut politického marketingu Citation2017), it is apparent that those topics (e.g., HC's collapse, DT's tax evasion and his non-public tax returns, terrorist attacks in New York and New Jersey, and the decline in support for the other candidates), were in fact not covered in the analysed sample of CRo programmes over the selected period. What should also be noted is that – with one only exception (a reference to G. Johnson and J. Stein on 10 November 2016 in the programme ‘Opinions and Arguments’) – there was no information given about the other US presidential candidates. It should not be excluded, however, that it was covered in other parts of the programmes that were not analysed.

Out of the total number of 118 analysed news items, three quarters (86%) mentioned the candidate HC and all of them, except two, referred to DT. Considering the fact that the majority of the news items were broadcast only after the election day (see above), it is not a surprise that some of them only focused on the winner and thoughts on his next steps. The stronger focus on DT also reflects the above specified thematic structure of the news, i.e., the fact that the personality of the future US president and the cases related to him represented the most frequently discussed frames. Detailed information on the candidates’ election programmes and their pre-election activities tended to be pushed to the side. Information on pre-election platforms and the campaign contents was provided by 16 news items only.

shows which attributes were assigned to the candidatesFootnote18 in the analysed period (both before the election date and after). DT was presented mainly as a Republican or the Republican Party candidate (or rival candidate, aspirant or competitor). He was also presented as a billionaire (or a millionaire or multi-millionaire) and businessman (also entrepreneur, magnate, real estate tycoon and developer), i.e., as a person familiar with economics and financially secure. The link between DT, business and money was mentioned roughly in every sixth news item. Further attributes included a reference to some of DT's potentially controversial features; expressions such as a boor, eccentric or obscene, chauvinist, yokel, misogynist or controversial appeared in one tenth of the news. There were less frequent references to his assumed insufficient competence for the presidency (e.g., incompetence for the presidency, politically inexperienced, chaotic, not familiar with politics, incompetent candidate) or to his media popularity (TV celebrity, reality show star), assumed populism (populist, exhorter of the people), or physical characteristics (alpha male, strong man, person in good shape).

Table 1. Attributes assigned to D. Trump and H. Clintona.

The most frequent attributes associated with HC were also those focusing on her candidacy (candidate, rival, competitor, etc.). The journalists in CRo also presented her as an experienced politician and referred to her former roles as First Lady, Secretary of State, or Senator but also labelled her as a careerist politician or a professional bureaucrat. This is how HC was presented in about one fifth of the news. Less frequent attributes included references to her weakness and alleged dishonesty (weak, unpopular, unelectable, corrupt, a crook, dishonest) or, on the contrary, to her strength and dominance in the polls (favourite, the most competent, sane, resilient). She was also sporadically referred to as a political party colleague of Barack Obama, Bill Clinton's wife, a feminist or a lawyer.

The above listed expressive and emotive labels of both candidates were used mainly in the programme ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ where they were presented with a reference to the foreign media in which they were used. Expressive or negative evaluation labels in the analysed programmes were used more frequently with DT.

shows the spectrum of speakers who expressed their opinions on the US presidential election in the analysed programmes. Not surprisingly, politicians and political scientists were the most frequently invited guests. Other categories of experts were significantly minimised in the broadcast programmes over the researched periods. In this context, the absence of views of sociologists and public opinion and pre-election poll specialists might seem surprising. If one excludes the CRo employees and associates, only 30 other speakers were broadcast. This means that the views of individuals outside CRo were presented in only one third of the news items. We consider this to be one of the key findings. We are of the opinion that the discourse of CRo itself is being closed in this way, and the range of opinions heard in the broadcasting is being narrowed at the same time (for more details see below).

Table 2. Guests taking part in the programmes, number of broadcasted speeches.

Findings from the qualitative analysis

The findings from the analysis carried out using qualitative research methods are outlined below. We focus on the identification of the journalist practices used for the construction of narratives on the US presidential election in the broadcasting of CRo that appeared in the majority of the analysed programmes. Although attempting to describe more general characteristics and trends specific for CRo broadcasting, the differences between the formats of the individual programmes cannot be ignored. The sample included both the programmes focused mainly on news and exclusively discussion programmes. The findings here are presented in relation to individual programmes. The key characteristics of the representation are explained using examples from the analysed sample.Footnote19

Disproportionate thematisation of the candidates’ personal characteristics and activities

The dominant aspect of the represented topic in selected programmes was the thematisation of the personal characteristics of the individual candidates. This was achieved through disproportionate representations of the individual candidates, and not by, for example, presenting their platform declarations or pre-election statements. When their political plans were presented, these became a significant feature of those news items presenting negative characteristics of DTFootnote20 and rather neutral, although significantly under-represented, characteristics of HC. Possible insufficient competencies and negative characteristics or actions were mentioned in relation to both candidates. An alternative and frequently used method was their representation as a lesser/greater evil. Closer to the election date and linked to the development of voting preferences for both candidates, the narrative based on (speculative) anticipation of the consequences of the election resultFootnote21 was used which associated the less-favoured candidate with a risk, threat or danger by both experts and common Americans.

After the election results were declared, certain aspects of the construction of the narrative changed and HC received even less space. In addition, the narrative of risk/threat/danger associated with the election winner proliferated in the post-election period, being primarily based on the future development predictionsFootnote22 (while in many cases these predictions were not supported by any arguments and/or facts or appeared in the form of unverifiable statementsFootnote23) or through the disqualification of the event's result by describing the election result as a ‘fault’, ‘mistake’, etc.Footnote24 The narrative of ‘a manipulated election’ was also thematized in the post-election period. This method can be considered paradoxical in many aspects as the pre-election statements of DT on ‘manipulating the election’ were used by the media as an instrument for his disqualification.Footnote25

The general disproportionate representation of the individual candidates resulted from the two below – described methods used in broadcasting:

the construction of the narrative with the use of semantic dichotomisation of the victim/aggressor

The disproportionate approach to the coverage of the candidates is apparent in the different ways of communicating the same aspect with the individual candidates. When the negative characteristic/activity of HC was mentioned, it was done so through the narrative of ‘a victim’Footnote26 (e.g., the announcement of the FBI director to Congress about further ‘questionable e-mails of H. Clinton’ that was represented in the media as an intrusion into the pre-election campaign with the aim of harming this candidate – ‘All these steps damage Clinton in the duel with Trump’).Footnote27 This narrative usually also made use of the semantic disqualification of the ‘aggressor’, rival candidate, DT.

This dichotomisation was intensified by disproportionate under/over/representation of the thematisation of the individual participants’ activities. While (negative) activities of DT were covered in relative detail (not only as for the nature of these activities per se but also their possible consequences and risks, etc.),Footnote28 the activities that could have been perceived as negative with HC were only mentioned (official e-mail communication via a private server, sponsored speeches given to financial institutions).

A typical instrument of the dichotomous representation of the candidates appeared to be the use of labelling, disproportionate nominalization of the candidates, which means using different types of identifiers for each of them. The example below clearly demonstrates the change in the use of the participants’ names in the syntagmatic construction of the news item. In the first part, both participants are referred to by their full names while in the other part (from the point of view of the pragmatics of communication, there is syntactic shortening in the nominalization of the already mentioned, i.e., known to the participants of the communication) the shortened form is used for identification of one specific person, however, in a disproportionate way:

… Hillary Clinton … Donald Trump … Donald Trump … Hillary Clinton … Trump … Trump … Trump's … Trump … Trump … Trump … Hillary … Trump … Hillary … Hillary … Hillary Clinton … Trump … Trump … in ‘Opinions and Arguments’17 Oct. 2016, 18:36–23:05

disqualification of the supporters/voters of one of the candidates

Individual candidates were often characterised through references to their electorate. The construction of their image was (predominately in the programme ‘The World in 20 Minutes’) repeatedly saturated with selective characteristics of their potential voters. While in the case of DT's electorate, they tended to be negative characteristics which were stated (low/incomplete/insufficient education, long-term and/or multiple unemployment, or even drug addiction), for HC's voters the identification was not value-laden (Afro-Americans, Hispanics, women). The disproportion in the final representation is the consequence of the following implication: if DT voters tend to be uneducated men, often unemployed and mostly white,Footnote31 those who vote for HC, in contrast, will be educated people, diverse in race, nationality and gender. This implication suffers, however, from significant logical lapses.

The characteristics of the potential voters (predominantly DT's) were legitimised by (selectively chosen) statistical data and the construction of the news emphasised the link between DT and the negative characteristics of his potential voters, while in case of his rival candidate any equivalent link was absent.Footnote32 Although some characteristics of Afro-Americans, e.g., high unemployment rate, were mentioned, they were not explicitly associated with HC while the negative characteristics of voters were associated with DT (‘ … white men without a higher education as the main electorate Donald Trump relies on’). The ‘imprudence’ of these potential voters was also confirmed by DT's disqualification and doubts about ‘a possible change’ through the reference to ‘expert knowledge’ (see below: ‘However, most of the economists, including the conservative ones consider Trump's economic plans as a chimera’).

The most comprehensive representations in the ‘Opinions and Arguments’ programme

Compared to other programmes, it was the ‘Opinions and Arguments’Footnote33 programme that provided the most comprehensive and most balanced depiction of the US presidential election in autumn 2016. The programme presented more specific thematisation and more detailed argumentation, covering a wider range of aspects of both the event itself and the activities related to its participants. It contained a better structured representation of the pre-election statements on both candidates’ intentions, interpretation of their TV debate, the theme of the election ‘Super Tuesday’, and also the reference to the Obamas’ support, etc. The representation of the election topic also included facts that were not covered by any other analysed programmes, were mentioned only marginally, or were used to disqualify one of the participants. It was only here, for example, where the attack on the Republican Party headquarters was thematized (17 November 2016).Footnote34

Nearly all the news items presented a relatively balanced image of both candidates (both in the sense of the ‘attention’ paid to each of them, and in the sense of the argumentative construction of the evaluation of their characteristics and activities) and represented the activities of both main participants in the election. Increased attention was also paid to the personality, activities and intentions of HC, per se and not as a means of defavourization or disqualification of the other candidate. Although an evaluation of a specific aspect of an event or candidate/s appeared frequently in the individual broadcast news items, in the vast majority of cases they were supported by facts and/or logical arguments.Footnote35

The above described higher comprehensiveness and quality of the coverage of the event can be, in part, assigned namely to the format of the programme that provided more space to the individual news items (which is, along with the higher diversity in the range of authors, reflected in the more varied thematisation of the event's representation); it is designed as a reading of news items prepared in advance (which enables the authors to construct their texts more comprehensively and support them with sufficient arguments) and also contains contributions from external authors (which might play its role in the more diverse thematisation and argumentation of the event supported by a broader range of sources).

A mostly balanced ‘Main News – Interviews and Commentaries’ programme

In the editorial part of the midday news broadcast ‘Main News – Interviews and Commentaries’, the way of representation of the topic in the examined period corresponded with the commonly used standard forms of the coverage of the event by a public service medium. The thematisation method used in this programme did not manifest any obvious fundamental imbalances regarding either the methods of the event's narrativization, or in terms of the final form of its representation. Apart from proportionally insignificant exceptions,Footnote36 the analysis did not identify fundamentally distorted or stereotyped media representation of the US election or the individual candidates. What predominated in the representation of the topic in the post-election period was thematisation of: (1) the causes of the election results, and (2) their possible consequences. Thematisation of more detailed information on the election results and also on the protests against DT's victory was rather marginal. The presented information was factual and the overall representation of the theme of the US presidential election was balanced. Of importance, however, is the fact that only 9 news items related to the US election were broadcast in this programme in the selected period (4 of them before the election date).

Intermediality in the programmes ‘Reading from the International Press’ and ‘The World in 20 Minutes’

The programmes ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ and ‘Reading from the International Press’ were based on presenting the information with references to the sources, to the representations published in foreign media.Footnote37 The selection of the reference media targeted, however, more or less mainstream media only which were commonly called liberal (e.g., the New York Times, the Guardian, BBC). This group of media more or less explicitly declared support for one of the candidates, HC. In this way, they expressed not only their preference and consequent bias in the presentation of the individual candidates.Footnote38 Regardless of the high degree of intertextuality and intermediality in the programmes, they became messages presented by CRo when broadcast. This means that CRo implicitly, and probably unintentionally, declared support for one of the candidates, which might be considered questionable in relation to a public service medium.

When comparing both programmes, ‘Reading from the International Press’ proved to be more comprehensive, heterogeneous and balanced. Especially the case of the HC emails was, in comparison with the programme ‘The World in 20 Minutes’, represented in a diametrically different way (01 Nov. 2016, 30:18–31:06: ‘At the same time, Comey publicly refused to blame Russia for the hacker attacks aimed at influencing the election … According to some unsupported allegations, Russian attacks were targeted … ’). Although the fact of blaming Russia for the above-mentioned activity was used, it was, in fact, not related to DT but presented as an ‘unofficial possibility’. The narrativization of HC as a victim was also absent. Similarly, in the post-election period, when the narrative of a hazard, threat, and danger derived from the negative predictions of the future development dominated the programme ‘The World in 20 Minutes’, the programme ‘Reading from the International Press’ thematically framed two aspects, namely: (1) quoting/paraphrasing the evaluation of the election results in the international media,Footnote39 and (2) possible further development.

One of the possible explanations of the distinction from ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ programme is the more limited space for individual news items that ‘pushes’ the authors towards more factual construction of the news. The final form of representation of the event in ‘Reading from the International Press’ was then, compared to the other programme, more balanced and, despite the rather limited time, also more diverse and generally less biased.

Bias in the editorial programme ‘Day According To … ’

The programme ‘Day According To … ’ stands out among the other ones as it is an editorial programme (which is also suggested by its title). The programme is based on using the genre of the interview which is supposed to take a form of an investigative interview. In some episodes over the observed period it acquired, however, more of the character of legitimisation of comparatively disproportionate media representation of the theme of the US presidential election through experts’ opinionsFootnote40 (mainly through the form and the method of conducting an interview with them). The extent of balance/bias in the thematisation of the event and favourization/disqualification of the individual participants varied substantially in the individual episodes.

The specific personality of both the presenter and the guest played a significant part in this programme. In certain cases, the leading of the interview could have been considered questionable, despite the fact that the broadcasting was live. The presenter usually led the interview in line with the event's framing and with the construction of the narrative of the theme established at the beginning of the programme, and the phrasing of questions frequently reflected their implicitly present attitudes.Footnote41 We noticed that they asked leading questionsFootnote42 or questions requiring a speculative answer.Footnote43

The role of the interviewed guest proved to be absolutely essential, primarily as to the extent to which they were able to oppose the presenter's strategies used for directing the interview towards their intentions. It was specifically thanks to the guests’ opinions that the final form of the representation of the event in the examined period was, in comparison with the other analysed programmes, more heterogeneous. Most of them interpreted the event in a way that in many aspects went beyond the frames typical for media representation of the topic in the other analysed CRo programmes.

Conclusion

The US presidential election is a highly complex and large-scale international event, occupying a considerable length of time and impacting a large geographic area. It is also linked to many partial events (which had already taken place and relevant information on which was not easily available and which was therefore mostly re-represented based on previously published media interpretations). It was therefore understandable that the dominant part of the information used for the representation of the event in CRo was taken from media representations in the US (and not only US) media. It is apparent that a significant emphasis is placed on the importance of the selection of sources from which the already created representations were borrowed and used for constructing their own way of representations of the specific event. A vast majority of (not only) US media expressed support for one of the participants in the event (candidates) over the course of the campaign and, by doing so, also declared (an intentional) bias in the representation of the event and provided further information on the related partial events through this prism. As these media became the primary sources of a not insignificant part of the information published in the examined CRo programmes, the above tendency is also reflected to a great extent in the final form of the presented CRo media representation. While this method can be perceived as legitimate with corporate media, in the case of a public service medium – CRo – it is considered questionable.

From the point of view of thematisation of the represented event, all the analysed programmes over the selected period revealed a comparatively high degree of similarity. The dominant feature in the majority of the examined programmes in the pre-election period was mainly the representation related to the course of the pre-election campaign and information on the course of the pre-election polling. In the post-election period, it was primarily thematisation of the causes of the election results and their possible consequences. A surprising finding was that only minimum attention was paid to one of the aspects usually associated with this kind of event – the candidates’ election platforms. The fact that a considerable part of the information on the election, even in the pre-election period, was related to the representation (e.g., characteristics, activities, opinions, etc.) of one of the participants only, namely DT, points out a significant bias in the overall media representation. Considering the requirements established by the legislation framework for CRo practice, it can be expected that – as a public service radio station – it provides space in its programmes to all candidates, i.e., including those with lower preference scores or ‘alternative’ opinions or who are ‘ideologically inconsistent’. In the case of the two main candidates for the post of US president, D. Trump and H. Clinton, it is to be expected that the space allocated to each of them would be approximately equivalent. The broadcasting otherwise manifests signs of a media producing their own ideological frame, a priori marginalising or disqualifying alternatives and, by doing so, playing a role in maintaining the ideological status quo.

Despite the facts, that Trump complained about media bias during the campaign and accused media of conspiring to rig the election, he profited from the media attention a lot (Talbot Citation2016). He got the highest media attention of presidential candidates in history. According to Tyndal report (2016) the presidential campaign in 2016 received the standard amount of coverage, however it was more contest of personalities rather than of public policy issues. Trump (1144 min) gained more than twice as much airtime as the coverage of Clinton (506 min) in tracked media (ABC: 434×199 min, CBS: 317×149 min, NBC: 393×159 min). We can speculate that it was the media, who helped Trump become the President of the U.S. The key factor was not that he got more TV news coverage than his oponents but because fake news conveyed by social media were more pro-Trump and more shared. In light of the growing sceptical attitudes of the public towards the media per se, is it also possible that such a (theoretically explicable) disproportionate approach to the individual candidates might, under certain circumstances, paradoxically result in unwanted support for the alternative candidate?

However, on the academic level it is not possible to advice the media how they should cover the events/topics. Various media coverage of key political figures, their used social practices, speeches tropes and metaphors applied in political discourses should be crossdisciplinarily studied in both synchronous and diachronous comparative perspective. Future research on media representation of political discourse in diverse countries can only help to understand the media operation in detail.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Mgr. Renáta Sedláková, Ph.D., graduated from Sociology at the Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University, Brno. She works as an assistant professor at the Department of Media and Cultural Studies and Journalism at the Faculty of Arts, Palacky University in Olomouc. She is mainly interested in the media effects on the society of late modernity and the ways of using media in everyday life (audience analysis). Her broader field of interest covers the media representation of reality, especially the case of minorities (e.g., older people, Roma minority, migrants) and the methodology of media studies.

Mgr. Marek Lapčík, Ph.D., graduated from Sociology at the Faculty of Arts at Palacky University in Olomouc. He works as an assistant professor at the Department of Media and Cultural Studies and Journalism in Olomouc. His main professional interest area is the theory of news discourse. He specialises in news discourse analysis and the ways how the news narratives are constructed in the contemporary media.

Mgr. Zdenka Burešová: Currently a PhD student, she received her Master’s degree in Media Studies at the Department of Media and Cultural Studies and Journalism at the Faculty of Arts at Palacky University in Olomouc. Ms. Buresova specialises in the field of news geography, which is the way the world is (re)presented in the news and media in general, with an emphasis on quantitative research techniques.

ORCID

Renáta Sedláková http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9761-978X

Marek Lapčík http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1858-5118

Zdenka Burešová http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4620-0548

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There is a dual broadcasting system in the Czech Republic. The public service media are represented by the Czech Radio and the Czech Television. Both of them runs several channels.

2 This article was conducted within the project Sinophone Borderlands – Interaction at the Edges and its findings will be used to compare the political discourses in the U.S. and China. The goal of the research was to find out how the discorses of international political relation between these supreme countries could change in the incomming new era of American politics.

3 Cf., e.g., Tuchman (Citation1978); Hartley (Citation2001); Bennett (Citation1996).

4 The effect of shaping was documented in, for example, research on political preferences amongst the German electorate in 1986 (McCombs Citation2004).

5 In sociology, the concept is associated with Goffman (Citation1974) who understand frames as an elementary cognitive scheme for organising and interpretation of reality of importance for a person's orientation in everyday life.

6 The second level agenda was examined, for example, in the images of the candidates in the Spanish election in 1995 (McCombs Citation2004).

7 Other candidates for the Democratic Party were, for example, Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley; for the Republican Party Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, John Kasich, Chris Christie, Ben Carson. Additionally, there were Gary Johnson for the Libertarian Party and Jill Stein for the Green Party and several others who withdrew over the course of the campaign.

8 Thematisation is, for the purpose of the analysis, understood as a specific method of articulation of a certain phenomenon/event/participant, i.e., those, out of a virtually unlimited range of possible and mediatable aspects of the phenomenon/event/participant, that were used for the construction of the representation of the phenomenon/event/participant.

9 The concept of a narrative is used here in the sense of a specific method for the construction of the news on a specific phenomena/aspect/participant, through both the selection of the means of expression and the selection of the organization of the structure of the news item. Here we use the concept of the narrative based on the duality of the story (created within the context of the related to each other events) and the discourse (structuring the method of the story narration, selection of events, their succession, etc.) Narrativization means a specific, currently used method of construction of the news, e.g., the selection of certain aspects (out of all potentially representable) of the specific phenomenon/event and the specific method of their representation (selection of the specific means of expression, implication of elementary semantic contours and by this also the preferred interpretation, etc.). For further details, see Chatman (Citation2008); Labov and Waletsky (Citation1967).

10 The programmes selected for the research were ‘Main News – Interviews and Commentaries’, ‘Reading from the International Press’ and ‘Day According To … ’ broadcast between 31 October – 11 Nov. 2016, ‘Opinions and Arguments’ and ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ between 31 October – 20 Nov. 2016. The research sample was established by the Czech Radio Board.

11 The aim of discourse analysis is to reveal how social reality is created, confirmed and maintained through social practice. Its essential aim is to examine the reproduction and legitimisation of ideologies and dominance of power elites and the discourse methods of maintaining the current status quo (Van Dijk Citation1983, Citation1993; Fairclough Citation2003; Phillips and Hardy Citation2002; Wodak and Meyer Citation2002).

12 Semiotic analysis attempts to understand the social use of signs in various contexts and identify elementary signs in a text and reveal the principles of its structure and use them to interpret its meaning (Chandler Citation2002).

13 For more details on the research methodology, see (Sedláková, Lapčík, and Burešová Citation2017).

14 18 times in the programme ‘Day According to … ’, 13 times in ‘Reading from the International Press’ and 9 times in ‘Main News’.

15 The lower ratio of coverage of the theme in October is supported by an analysis of the longer time span than the one presented in this text (Sedláková, Lapčík, and Burešová Citation2017).

16 The significance of the information referring to the election in the research item was coded. We distinguished between: (1) primary theme, i.e., key theme, dominant considering the time allocated to it; (2) secondary theme that provided information related to the election and expanding or complementing the other primary theme; and (3) mentions news items that contained a reference to the topic but was not further analysed and, in relation to the given piece of news, this information was completely peripheral.

17 For the frames in the news, so-called emergent coding was used, i.e., based on the records of all the research sample, and individual themes were grouped into several more general categories.

18 The analysis did not include the attributes associated with D. Trump as the ‘elected president’ and ‘election winner’ as the analysis objective was to determine whether both candidates were or were not presented with an emphasis placed on their different characteristics or features.

19 Considering the fact that the material used was broadcast in the Czech language and a number of conveyed semantic nuances might not be easy to translate, we often use the references to the programme only, the day and time where the excerpt that serves as an example of the described phenomenon comes from.

20 E.g., ‘The World in 20 Minutes’ (28 Oct. 2016, 9:01–13:35), where the economic plans of D. Trump were (with no detailed specification) framed by the opinion of generalised experts (‘Most of the economists, including the conservative ones … ’) who classified them as ‘a chimera’.

21 ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 9 Nov. 2016, 8:09–13:04: ‘What to expect from Trump in international relations, that's what we have no idea about. His ideas were very vague and what emerged in them was mainly his fondness for strong and not always democratic leaders of other countries. When Trump grows fully acquainted with the complexities of American security and the foreign-policy machine, he will probably find out very quickly that the momentum of the American system is particularly strong in this area and that any fundamental changes will not be possible. The greatest risk in foreign policy is related to Trump's self-centeredness and megalomania which he used to sell successfully to his voters as decisiveness and intransigence against the established system. In the foreign policy, however, of the most powerful country in the world, fallacies and placing personal ambitions above the whole are not possible because it could cause a global conflict. Trump will have to learn and accept the fact that the American president serves the system, and not the other way round. If he cannot cope with this transformation, the world in the upcoming years will be facing serious risks’.

22 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 18 Nov. 2016, 2:11–7:29.

23 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’15 Nov. 2016, 7:51–12:21.

24 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 12 Nov. 2016, 0:44–4:55: ‘The elected president is a man who, purely technically, in his campaign, ruined whatever he touched. He divided his own party, he pointlessly insulted women, Hispanics, Muslims, and others. And we could go on. … But let's not delude ourselves. We won't win anything. What happened on Tuesday is a disaster for both liberalism and the world. Once president Trump starts getting his own back on his former rivals, he will provoke rifts with other countries and he will send his special deportation police on this or that group, we will very soon have a reason for regretting electing him the president, says The Guardian columnist Thomas Frank’.

25 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 9 Nov. 2016, 6:28–11:57.

26 The narrative of HC as a victim is in some cases used together with the narrative of (an unverifiable) prediction. For example ‘Opinions and Arguments’10 Nov. 2016, 7:12–10:25: ‘The fact is also that Clinton became a victim of unprecedented attacks from her rival. According to him, she was weak and distasteful. The seventy-year-old Trump alleged that the one year younger politician lacked courage, that she was not as fit as him, that she led the campaign while she needed to have a rest in bed. Presidential debates were a display of how a man … should not communicate with a woman … From Trump's side, they were full of prejudice, patronising and suggestions that Clinton did not know what she was talking about and therefore, did not deserve respect. Not because she was his political opponent but because she was a woman … ’.

27 ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 1 Nov. 2016, 0:39–7:25: ‘FBI director … turned the course of the pre-election campaign … caused problems for Clinton in the election fight … by making public unverified indications, he purposefully caused confusion … by his actions he supports Clinton's political death without her having a chance to defend herself … ’

28 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 20. Oct. 2016, 0:33–4:38.

29 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 30. Oct. 2016 9:08–13:43.

30 Enli (Citation2017).

31 In a certain sense, this implication can be considered even racist.

32 E.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 28 Oct. 2016, 9:01–13:35.

33 This programme consists of commentaries and analyses on the current political situation with a focus on international affairs. On the weekend, however, it changes into a discussion forum with the parties not represented in the Parliament and on Sunday into a 50-minute-long round-table discussion on the topic of the day, which makes it less comparable with the other analysed programmes also due to its considerably longer broadcast time.

34 If the activities of such a kind were mentioned in the other programmes (e.g., ‘Day According To … ’), they were associated with DT only and represented as consequences of his activities.

35 Here, it means an argumentative approach as such, respecting the necessity for supporting the stated information with its sources (obvious, above all, in the news items prepared beforehand to be read– see below). Although the individual authors’ opinions varied considerably, they all could be considered as supported by the arguments. While in the narratives in some other programmes, some aspects were represented as ‘self-evident’, ‘indisputable’, or as facts supporting another thesis, in this programme they were either supported by arguments, or even problematised.

36 These included, for example, some of the commentators’ pointlessly metaphorical statements (e.g., ‘Opinions and Arguments’ 1 Nov. 2016, 15:38–16:16: ‘The tables in the US presidential election are, apparently, turning one week before the vote … ’ 7 Nov. 2016, 11:38–11:47: ‘ … something like what you call a pointer showing how the scales tilt’).

37 Compared to others, ‘Reading from the International Press’ adopted the news from a more diverse range of media, concerning both their number and the country of origin.

38 For example, the HC email case was dominantly construed as the FBI director's intervention in the course of the election aimed at harming the candidate.

39 E.g., ‘Reading from the International Press’ 10 Nov. 2016, 37:19–40:54: ‘In the American press worries mingle with the hope that Trump will not continue in the style of the campaign … ’.

40 A considerable proportion of the respondents were experts in the field that was thematized (a political scientist, an Americanist, an economist), and participants with the ascribed position of experts (e.g., ‘V.Vetvicka, who works at an American University’). On the other hand, the role of an ‘expert on the United States’ was assigned to journalists who were present on the spot (which is all the U.S.A.), and alsothea chief editor of one of the online daily newspapers.

41 E.g., ‘Day According To … ’ 7 Nov. 2016, 0:38–18:02 Presenter: ‘Well then, how did educated Americans justify the fact that they were not going to vote for Hillary Clinton and would instead vote for uncertainty with Donald Trump?’ At the same time, it should be mentioned that some of the guests in their utterances rejected the frame suggested by the presenter. This occurred, for example, in an interview with a reporter of Czech Radio in the U.S.A.: 6 Nov. 2016, 0:35–8:18.

42 E.g., ‘Day According To … ’ 2 Nov. 2016, 09:02–16:46: Presenter: ‘And the last question for you, Julie. How do you rate the involvement of the FBI this year in the election, of course I mean metaphorically because I know that officially the FBI denies any involvement, nevertheless it intervened in it substantially through their actions, and one cannot help feeling a bit confused’.

43 E.g., ‘Day According To … ’ 3 Nov. 2016, 27:05–30:33.

References

- Ahmadian, Sara, Sara Azarshahi, and L. Delroy Paulhus. 2017. “Explaining Donald Trump via Communication Style: Grandiosity, Informality, and Dynamism.” Personality and Individual Differences 107: 49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.018

- Argina, Ade W. 2018. “Presupposition and Campaign Rhetoric: A Comparative Analysis of Trump and Hillary’s First Campaign Speech.” International Journal of English and Literature 8 (3): 1–14. doi: 10.24247/ijeljun20181

- Ashcroft, Anton. 2016. “Donald Trump: Narcissist, Psychopath or Representative of the People?” Psychotherapy and Politics International 14 (3): 217–222. doi: 10.1002/ppi.1395

- Bennett, W. Lance. 1996. News: The Politics of Illusion. New York: Longman Publishers USA.

- Chandler, David. 2002. Semiotics. The Basics. London: Routledge.

- Chatman, Seymour. 2008. Příběh a diskurs [Story and discourse]. Brno: Host.

- Cottle, Simon. 1997. Television and Ethnic Minorities: Producers’ Perspectives. Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Day According To … (Den podle …). 2016. Episodes Broadcast from 31 October 31 to November 11, Czech Radio (Plus). Accessed 4 December 2018. https://plus.rozhlas.cz/den-podle-6482951.

- Enli, Gunn. 2017. “Twitter as Arena for the Authentic Outsider: Exploring the Social Media Campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election.” European Journal of Communication 32 (1): 50–61. doi: 10.1177/0267323116682802

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Psychology Press.

- Goffman, Erwing. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Gökariksel, Banu, and Sara Smith. 2016. “‘Making America Great Again’?: The Fascist Body Politics of Donald Trump.” Political Geography 54: 79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.07.004

- Goodell, W. John, and Sami Vähämaa. 2013. “U.S. Presidential Elections and Implied Volatility: The Role of Political Uncertainty.” Journal of Banking and Finance 37 (3): 1108–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.12.001

- Gounari, Panayota, and J. Morelock. 2018. “Authoritarianism, Discourse and Social Media: Trump as the ‘American Agitator’.” In Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism, 207–227. London: University of Westminster Press.

- Gregor, Miloš. 2016. “Rise of Donald Trump: Media as a Voter-Decision Accelerator.” In US Election Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign, edited by Darren Lilleker, Daniel Jackson, Eeinar Thorsen, and Anastasia Veneti, 18–19. Poole, UK: Bournemouth University.

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage.

- Hartley, John. 2001. Understanding News. London: Routledge.

- Institute for Political Marketing. 2017. Americké volby. Nejdražší show světa [American Elections. The Most Expensive Show in the World]. Praha/Brno: Institut politického marketing. Accessed 15 March 2017. http://politickymarketing.com/glossary/politicky-marketing.

- Jutel, Olivier. 2017. “American Populism, Glenn Beck and Affective Media Production.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, 1–18.

- Kronick, Jane C. 1997. Alternativní metodologie pro analýzu kvalitativních dat [Alternative Methodology for Qualitative Data Analysis]. Czech Sociological Review 33 (1): 57–68.

- Labov, William, and Joshua Waletsky. 1967. “Narrative Analysis.” In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts, edited by June Helm, 12–44. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Luhmann, Niklas. 2000. The Reality of the Mass Media. Cambridge, Oxford: Polity Press, Blackwell University Press.

- Maher, T. Michael. 2003. “Framing: An Emerging Paradigm or a Phase of Agenda Setting?” In Framing Public Life. Perspectives on Media and Our Understanding of the Social World, edited by Stephen D. Reese, et al., 83–94. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Main News – Interviews and Commentaries (Hlavní zprávy – rozhovory a komentáře). 2016. Episodes Broadcast from October 31 to November 11, Czech Radio (Radiozurnal/Plus). Accessed 4 December 2018. https://plus.rozhlas.cz/hlavni-zpravy---rozhovory-komentare-6483152/o-poradu.

- McCombs, Maxwell. 2004. Setting the Agenda. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- McCombs, Maxwell, and Donald Shaw. 1991. “The Agenda Setting Function of Mass Media.” In Agenda Setting – Readings on Media Public Opinion and Policy Making, edited by David Protess, and Maxwell McCombs, 17–26. Hillsdale, Hove, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. London: Sage.

- Opinions and Arguments (Názory a argumenty). 2016. Episodes Broadcast from October 31 2016 to November 21 2016, Czech Radio (Plus). Accessed 4 December 2018. https://plus.rozhlas.cz/nazory-a-argumenty-6504158.

- Phillips, Nelson, and Cynthia Hardy. 2002. Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Pickard, Victor. 2016. “Media Failures in the Age of Trump.” The Political Economy of Communication 4 (2): 118–122.

- Reading from the International Press (Četba ze zahraničního tisku). 2016. Episodes Broadcast from October 31 to November 11, Czech Radio (Plus). Accessed 4 December 2018. https://plus.rozhlas.cz/ranni-plus-6126378/o-poradu.

- Reese, Stephen D. 2003. “Prologue – Framing Public Life: A Bridging Model for Media Research.” In Framing Public Life. Perspectives on Media and Our Understanding of the Social World, edited by Stephen D. Reese, Oscar H. Gandy, and August E. Grant, 7–31. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Schulz, Winfried. 2000. “Masová média a realita ‘Ptolemaiovské’ a ‘Kopernikovské’ pojetí [Mass Media and Reality. The ‘Ptolemaic’ and ‘Copernican’ View].” In Politická komunikace a media, edited by Jan Jirák, and Blanka Říchová, 24–40. Praha: Karolinum.

- Sedláková, Renáta, Marek Lapčík, and Zdenka Burešová. 2017. Analýza mediální reprezentace amerických prezidentských voleb roku 2016 ve vybraných pořadech Českého rozhlasu [Analysis of the Media Representation of the US Presidential Elections in 2016 in Selected Czech Radio Programs]. Accessed 15 March 2019. http://media.rozhlas.cz/_binary/03830543.pdf.

- Talbot, Margaret. 2016. “Trump and the Truth: The «Lying» Media.” The New Yorker, September 28. Accessed 14 July 2019. http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/trump-and-the-truth-the-lying-media.

- The World in 20 Minutes (Svět ve 20 minutách). 2016. [Radio Program], Episodes Broadcast from October 31 to November 21, Czech Radio (Plus). Accessed 4 December 2018. https://plus.rozhlas.cz/svet-ve-20-minutach-6504146.

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1978. Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: Free Press.

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 1983. “Discourse Analysis: Its Development and Application to the Structure of News.” Journal of Communication 33 (2): 20–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1983.tb02386.x

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 1993. “Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis.” Discourse and Society 4: 249–283. doi: 10.1177/0957926593004002006

- Wodak, Ruth, and Michael Meyer. 2002. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.