Abstract

This study sought to estimate the frequency of harassment, threats, assault and stalking faced by Victorian Members of Parliament (MPs), with a focus on gender and experience of online abuse. 46 of 128 MPs completed an online survey (36%). 82% reported experiences of harassment, 85% reported threats of harm, and 35% reported stalking, with most reporting lifestyle changes in response. Female MPs were more likely than males to report all these experiences. Almost 100% of MPs using social media reported online abuse. Abuse about political positions or general defamatory statements were most common (95% and 87% respectively) and were experienced equally by male and female MPs. 50% reported gender-based abuse, with 85% of female MPs reporting such abuse. Results highlight the frequency and impact of abuse and harassment of MPs by the public, and support the need for increased awareness of, and accessibility to, expert advice, threat assessment and interventions.

Introduction

I think there used to be an aura around someone who was an MP, they were seen as a terribly important person and people would be very deferential to them… That esteem is no more. Some of this has been self-inflicted, but it is not all down to the MPs. (Amess, Citation2020, p. 8)

In his part autobiography, part guidebook, ironically titled Ayes and Ears: A Survivor’s Guide to Westminster, long-serving Conservative MP Sir David Amess emphasised the importance of members being accessible to their constituents, listening to their problems and helping to fix them, but he lamented the erosion of trust in politicians and growing incursions into the private lives of elected officials, raising security concerns and forcing MPs to change the way they connect with the public. Tragically, Sir Amess was stabbed to death on 15 October 2021 at a political surgeryFootnote1 by a male voter with ideologically-driven motives.

Reports of intrusive and aggressive behaviour towards elected officials by members of the public are becoming more frequent. Five years prior to the assassination of David Amess, British Labour Party MP, Jo Cox, was murdered by another lone, male, mentally disturbed constituent. At that time, it was noted that attacks or attempted attacks on politicians were common to all liberal democracies, and that serious attacks were ‘predominantly the work of mentally ill, isolated loners, who have been nursing a grievance, often for years, which they sometimes wrap in a political (or ideological) flag’ (from James, Citation2016).

While it has only attracted the attention of behavioural scientists in the past three decades, there is evidence that public figures have long been the subject of grievance-filled fixations that culminate in physical violence (Fein & Vossekuil, Citation1988; Meloy et al., Citation2004). For example, in 1881 the American President, James Garfield, was assassinated by Charles Guiteau, who had longstanding delusions of grandeur, including the belief that he had written Garfield’s winning presidential speech. Guiteau stalked Garfield via repeated letters and approaches, demanding a diplomatic post in Paris for his vital contribution. The shooting of President Garfield at a train station in Washington, DC as he was leaving for a much-publicised summer holiday, was primarily motivated by Guiteau’s pathological grievance and hunger for revenge (Millard, Citation2011). Serious assaults on public figures are fortunately rare in Australia, with just two recorded assassination attempts by mentally ill, fixated individuals: the near-fatal shooting in 1868 of Prince Alfred, son of Queen Victoria, by a man who had been recently released from a psychiatric institution (James et al., Citation2008); and the attempted shooting in 1966 of Australian political party leader, Arthur Calwell, by a mentally ill teenager (Freudenberg, Citation2006). Mullen et al. (Citation2009) provide an overview of such attacks.

While physical attacks on politicians remain relatively rare, stalking and harassment are far more common. Surveys of public officials and office holders (POH) in several liberal democracies suggest that approximately one third have experienced stalking, while four out of five report unwanted harassment in the course of their public life (James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016; Narud & Dahl, Citation2015). This can be contrasted to approximately 15% of adults in the general population reporting lifetime stalking victimisation, with approximately half of those cases involving former intimate partners (McEwan & Pathé, Citation2013). As with violent offences in general, stalking of private citizens is a predominantly male offence and their victims are mostly female (Purcell, Pathé & Mullen, Citation2002). It has been suggested that women are more likely to be targets of gender-based violence due to the effects of patriarchal social norms on behaviour, with women who are perceived to step outside the bounds of appropriate or acceptable behaviour being more likely to be targets of misogynistic behaviour intended to police their actions (Manne, Citation2017).

POH are likely stalked more frequently due to the nature of their role, which brings them into contact with a wide range of people and places them in a position of power and responsibility (Jutasi & McEwan, Citation2021). They are often required to court approval and credence through their accessibility to members of the public but this can also invite harassment and unwanted intrusions, particularly during political scandals and controversies (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015; James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016). Indeed, the power and influence of public figures can be a beacon for frustrated, unrealistic, and discontented citizens.

Studies of stalking in the general population and of fixated individuals who stalk public figures have helped shape our response to those who pose a threat to POH and public safety. Fixation is a psychological concept defined as ‘obsessive preoccupation with a person or a cause, pursued to an excessive, extreme or irrational degree’ (Mullen et al., Citation2009, p. 34). Those who are fixated on a cause, as opposed to a person, typically pursue political figures, since they perceive the politician as a symbol, an obstacle, or a potential source of help or harm to their grievance or quest for justice. The risk of serious harm is greater among individuals who are fixated on a cause, as they are more likely to hold a grudge against the politician and to plan and commit an attack (Fixated Research Group, Citation2006; James et al., Citation2011).

Other key findings to emerge from the literature on public figure stalking and fixated persons are the prominence of mental illness among the fixated (Barry-Walsh et al., Citation2020; James et al., Citation2008; Pathé et al., Citation2016), and the importance of fixated warning behaviours. These behaviours, which include inappropriate correspondence and approaches to POH, provide opportunities for prevention and intervention (James, Mullen, et al., Citation2007; Meloy et al., Citation2012). This research underpins the Fixated Threat Assessment Centre (FTAC) model, first established in the UK in 2006, which aims to protect dignitaries and the community from fixated loners while facilitating care for the high proportion of fixated cases with serious, untreated mental illness (James, Kerrigan, et al., Citation2010; Wilson et al., Citation2021). The FTAC is a fully integrated police-mental health intelligence agency with a secure framework for gathering, analysing and sharing relevant law enforcement and health information. The overrepresentation of mental illness among fixated persons who target POH has since been replicated in studies of other forms of targeted or planned violence including mass murder and lone actor terrorism (Gill et al., Citation2021). The FTAC paradigm provides a blueprint for the development of preventative approaches to these other forms of lone actor targeted violence. FTACs have since been established in parts of Europe, New Zealand and all Australian states and territories, and a number of these jurisdictions have expanded the original model to include the prevention of other targeted, grievance-fueled violence by lone actors, including lone actor terrorism (Barry-Walsh et al., Citation2020; Pathé et al., Citation2018; van der Meer et al., Citation2012; Wilson et al., Citation2021).

While not all people who harass politicians have a pathological fixation or pose a risk of serious violence, the following studies highlight the range of detrimental impacts caused by members of the public who persistently intrude upon and threaten POHs, their family and/or staff, including interference with the MP’s function and the democratic process (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015; James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016; Pathé et al., Citation2014).

Surveys of harassing behaviours experienced by politicians

Pre-pandemic surveys conducted in England, Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand have explored the frequency, nature and impacts of inappropriate communications, approaches and attacks on Members of Parliament. The largest of these involved 239 MPs in Westminster Parliament in the UK in 2010 (James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016; James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016). MPs were invited to complete a survey that was adapted from a questionnaire developed for an Australian epidemiological study of stalking victimisation among the general public (Purcell et al., Citation2002). Of the 38% of Members who completed the questionnaire, 81% had experienced aggressive or intrusive behaviour from constituents. More than half the respondents reported behaviour that met stringent study criteria for stalking (53%).

The UK survey was later adopted and employed in studies in Queensland, Australia (Pathé et al., Citation2014), Norway (Bjelland & Bjørgo, Citation2014) and New Zealand (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015). Despite differing parliamentary structures, sample sizes and response rates, there is some consistency in the key findings of these studies with comparable methodologies: very high proportions of respondents reported having experienced at least one form of harassment ().

Table 1. Summary of response rates and key findings from surveys of stalking experiences of parliamentarians with similar methodologies.

Overall harassment rates have been less consistent in studies employing different questionnaires and definitions. A Canadian survey of federal and provincial politicians in office in 1998 (response rate 50%) found a high frequency of intrusive behaviours (85% of MPs reporting inappropriate telephone calls, often repeated, three quarters of which contained overt threats and unwanted approaches in 60%: Adams et al., Citation2009). In a 2001/2002 survey of politicians in the Netherlands (35% response rate), a third of respondents indicated they had been stalked (Malsch et al., Citation2002). A large Swedish survey of local and national MPs (68% response rate) found that over a third were exposed to harassment or physical violence in the year 2011 (Brottsförebyggande rådet, Citation2012). In 2012 a more streamlined questionnaire administered to Swedish MPs with a similar response rate found levels of harassment, predominantly via social media, of almost 60% (Wallin & Wallin, Citation2014). A later study of Norwegian parliamentarians reported victimisation rates of 75%, with 28% of respondents experiencing serious stalking (Narud & Dahl, Citation2015).

In summary, the majority of parliamentarians responding to these surveys experienced threats of harm. These threats were often repeated and encompassed threats of violence towards the parliamentarian, harm towards their family, damage to property, bomb threats, veiled threats, threats to ruin the MP’s reputation and threats to commit suicide. Interference with the MP’s property was reported by 22% of the UK sample and a third of the Queensland and New Zealand samples, while only 8% of Norwegian parliamentarians endorsed this item. Comparable levels of actual or attempted physical assault were experienced by these MPs (18% of UK respondents, 14% in Queensland and Norway and 15% in New Zealand). There were reports in the UK study of MPs being hit with a brick and shot with an air rifle; in New Zealand, a Member was repeatedly punched in the face and another received agricultural poison in the mail, and a staffer at a Queensland MP’s electoral office was held captive in a siege with a loaded shotgun.

In these surveys, reports of online harassment through social media, blogs, websites and email have increased over time with the burgeoning popularity and accessibility of these platforms. In 2010, 10% of UK MPs surveyed reported inappropriate social media contact from constituents. This figure increased to 37% in the 2011 Queensland survey, 38% of Norwegian MPs in 2013, and 60% of New Zealand MPs surveyed in 2014 (Bjelland & Bjørgo, Citation2014; Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015; James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016; Pathé et al., Citation2014). A 2018 survey of the UK House of Commons that specifically explored the extent and nature of social media abuse found that 100% of respondents (28% of 650 MPs) actively used social media, most commonly Twitter, and all experienced some form of online abuse or ‘trolling’, defined as ‘experiencing one form of online abuse (posting of defamatory or false materials, racial abuse, sexual abuse, abuse on political grounds/beliefs, abuse on religious grounds/beliefs) and one form of online threatening behaviour (death threats, physical violence, rape, physical violence to friends and family, reputational damage, property damage)’ (Akhtar & Morrison, Citation2019, p. 323). Much of this was political and reactionary, relating to the MP’s public profile, controversial views, and presence on social media. While female MPs reported similar levels of trolling as did their male counterparts, women experienced more racial and sexual (sexist; misogynistic) abuse. Male MPs reported greater concern about reputational damage, whereas females were most concerned about their safety. Female MPs were also more likely to report emotional stress in response to abuse.

The characteristics of victimised MPs varied, with some studies revealing more frequent harassment among younger parliamentarians (Wallin & Wallin, Citation2014) and more frequent stalking experiences in younger parliamentarians (James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016). Westminster MPs who had been in office for less than five years (also a significantly younger group) were more likely to be stalked. The authors postulated that this might reflect the tendency for newer parliamentarians to try to resolve all complaints by constituents, however unrealistic the constituent’s expectations.

Conversely, UK MPs who had been in parliament for more than five years or those in urban constituencies were more likely to report an attack or attempted attack. The Canadian study found an increased likelihood of harassment of federal politicians with more years in office (Adams et al., Citation2009). Higher rates of victimisation have been reported by MPs holding more senior positions, who are more active and visible, and those who chair certain boards, such as planning and building, and social welfare (Wallin & Wallin, Citation2014). Most studies have reported no significant differences between political affiliation and stalking or harassment experiences or have not explored this.

Gender associations are similarly inconsistent or not explored. The UK study found that gender differences were associated with years in parliament; females in office for five years or less were most likely to have been stalked and harassed (James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016). There were no gender differences among Canadian MPs reporting harassment (Adams et al., Citation2009), but female parliamentarians in Sweden were more likely to report threats and harassment than their male counterparts (Wallin & Wallin, Citation2014). The Swedish study also found gender differences in MPs’ reasons for not reporting their experience of victimisation. While women most commonly attributed this to a perceived acceptance of victimisation as part of their role, men attributed it to a perception that a report would not result in any meaningful action. In some cases, these behaviours occurred over a protracted period, particularly if they met the threshold for stalking. Across surveys, the duration of the harassment ranged from less than one hour to 16 years.

The motives for unwanted intrusions were congruent across studies. Despite singular reports of amorous gestures towards Canadian Members, individuals who harassed were predominantly pursuing personal agendas and grievances (Adams et al., Citation2009). The surveys have found that the majority of people who intrude upon POHs are male, and many are known to the MP: almost 42% of UK Members and 38% of the Queensland sample knew the identity of the perpetrator. In the UK, this number increased to 50% if the perpetrator was stalking them. The remainder were strangers or unidentified persons.

All studies have highlighted the negative impact of these intrusions on the parliamentarians’ work, health and personal life. Three quarters of the Westminster sample experienced fear in response to the harassment, a third acknowledging they were ‘moderately’ or ‘very’ fearful, citing concerns for their own safety and that of their family and office staff. A concerning proportion (22%) felt anxious about going out in public and 16% disclosed their fear of being home alone (James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016). Similarly, 28% of Queensland survey participants and 20% of their New Zealand counterparts reported fear of at least moderate severity, concerns for their personal safety and that of significant others, and 20% of the Queensland sample and 12% of the New Zealand MPs said they felt concerned about going out in public (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015; Pathé et al., Citation2014). Parliamentarians who experienced more serious incidents including stalking and harassment reported higher levels of distress. Of the targeted Norwegian MPs, 17% had considered leaving politics and reported that their victimisation either restricted their freedom of speech on a political issue, made them hesitate to take a public position on an issue, discouraged them from engaging with a specific issue, or influenced them to make a different decision (Bjelland & Bjørgo, Citation2014).

Most MPs in these surveys had sought assistance, either formally or informally, especially those subjected to more serious abuse. Sources of help included colleagues, family, friends, police, parliamentary security personnel, private security companies and/or lawyers. The MPs’ assessment of the benefits of these interventions varied across and within studies. In the UK survey, 80% of affected MPs sought advice from law enforcement agencies, but fewer than half considered this to be ‘very helpful’, while 17% rated this intervention ‘unhelpful’ (James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016).

Study aims

This study extended the literature on harassment and stalking of MPs in a different Australian jurisdiction. We sought to establish estimates of the frequency of unwanted approaches, threats, assault and stalking faced by Victorian MPs in their parliamentary role, with a particular focus on gender and their experiences of online abuse, which have been a lesser focus in previous research. The study also sought to explore the impact of these behaviours on the MPs’ personal and public life, and the perceived effectiveness of any sources of help.

Materials and methods

This study was commissioned by the Victorian Department of Parliamentary Services with the support of the Presiding Officers and Clerks and received ethical approval from the Office of Research Ethics and Integrity, University of Melbourne (HREC No. 1954685).

The study population comprised all 128 sitting members of the Victorian Parliament. The survey was based on that used in previous research (e.g. Pathé et al., Citation2014), but was expanded to collect information pertaining to experiences of online harassment and social media use. Data was collected online between February 2020 and January 2021 with a link distributed to MPs via email. Three reminders were sent at intervals to all MPs, given the survey responses were anonymous. The survey consisted of 122 items in total, with a selection of items that were completed only by those who endorsed victimisation experiences within their parliamentary role.

To preserve anonymity, some potentially identifying demographic information was not collected, but the survey did seek the MP’s age, gender and years in office. The questionnaire did not request the MP’s party affiliation but instead employed a measure of political alignment.

To determine the presence of stalking, participants were asked about their experience of a pattern of repeated and unwanted approaches, contact or pursuit during their time as an MP. Those who endorsed this item were asked further questions about the nature of the behaviour and its impacts. Stalking was considered present if there was a pattern of unwanted contact by a single perpetrator involving at least five separate intrusions persisting for more than two weeks that caused fear for safety or significant distress (McEwan et al., Citation2021). The definition of stalking used in this study is adapted from work by Purcell et al. (Citation2004), who reported that the most sensitive indicator for distinguishing between victims in terms of psychological and social impacts is the continuation of the intrusions beyond two weeks. Lesser intrusions (where duration is less than two weeks) overlap with experiences that are more commonplace and less damaging. These experiences are referred to as ‘harassment’ throughout this article. Survey participants who endorsed multiple episodes of victimisation were encouraged to reflect on their most serious experience by considering the case that ‘stuck most in their mind’.

Results

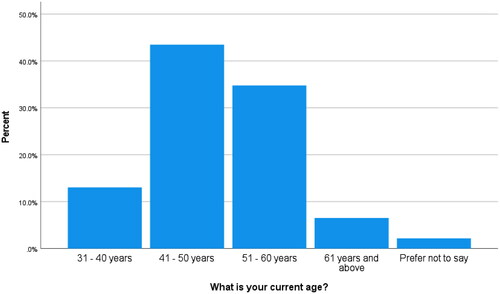

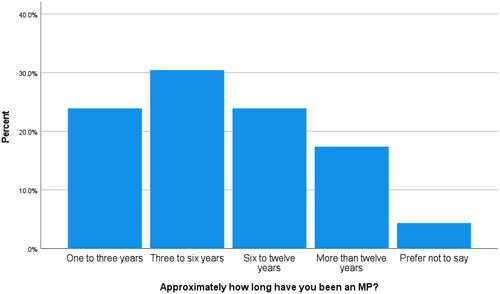

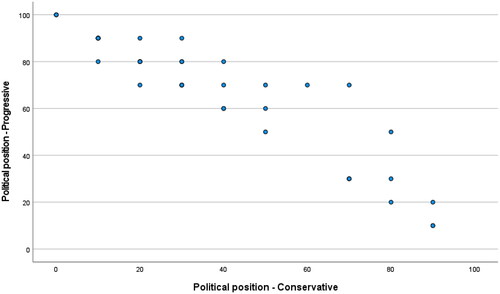

The 46 MPs who participated in the study (a response rate of 36%) represented a diverse group from across the political spectrum and levels of experience, as shown in to . Female members were overrepresented among survey participants, constituting 30% of the Victorian Parliament, but 56% of survey respondents. One respondent identified as non-binary. We have chosen not to report data pertaining to this individual’s experience alone and have excluded them from gender-based comparisons. Thirty-one MPs (67%) completed the survey, in an average time of 15 minutes (range 8 minutes to 28 minutes). Half of those who didn’t finish the questionnaire spent up to 10 minutes on the task, and their responses are included where available.

Figure 3. Political alignment of survey respondents, progressive to conservative. Each dot represents a participant, plotting their stated level of progressive politics against their stated level of conservative politics.

Experience of unwanted approach or persistent unwanted contact

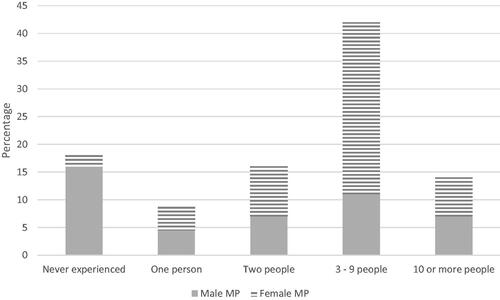

Eighty-two percent of participants reported unwanted approaches or persistent unwanted contact during their time as an MP. Almost half (44%) estimated that they had been targeted by between 3 and 9 different people, and in six cases by more than 10 different people (). There was no observable relationship between time in parliament and the experience of unwanted approach or contact by different people. One respondent commented: ‘It happens often, sometimes a one-off at an event and others a few times. During a major dispute multiple people in an effort to distract me.’

There were observable gender differences in the proportion of women and men who reported some form of harassment, and in the estimated number of different harassers. Over one third of male participants reported no experiences of this nature, whereas the same was true of only 4% of responding female MPs.

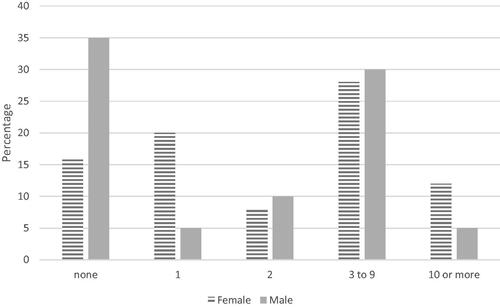

Experience of threats

Thirty-nine participants (85%) responded to a question about being threatened with harm during their time as an MP; 61% of these said that they had been threatened, of whom 86% experienced threats more than once (). There was no relationship between experiencing threats of harm, years as an MP or political alignment. Again, there was a gender difference in the overall experience of threats, with women more likely to report threats than men (68% vs 50%). However, once an MP indicated they had been threatened at least once, there were no marked gender differences in the number of times MPs reported being threatened.

Experience of assault

Two out of 38 participants (4%), both women, indicated that they had been the target of an attempted or actual physical assault on 3–9 separate occasions in the course of their parliamentary duties.

Experience of stalking

Thirty of the 46 participants (65%; 18 female) reported that they had experienced a pattern of harassment during their time as an MP. Rates for both male and female participants were high, with 72% of women and 60% of men reporting some unwanted pursuit. When these experiences were examined further, 35% met the stringent threshold for stalking (16 individuals; 9 female). In 11 cases the stalker was a male, 2 stalkers were female, and in 3 cases the stalker’s gender was not known to the MP. In 7 cases the stalker was a stranger to the MP, in a further 7 they were someone the MP had met through their parliamentary role, and in 2 cases they were former friends. None of the respondents reported being a target of stalking by a former intimate partner. Stalking episodes ranged in duration from 1 month to 72 months, and 9 MPs reported ongoing stalking at the time of the study.

A further 30% of participants (15 MPs) reported a pattern of harassment that either continued for longer than two weeks but did not occasion significant distress or fear (8 MPs), or caused distress or fear but did not persist for more than two weeks (7 MPs). While these individuals were not classified as stalking victims (as per the definition of ‘stalking’ used), it is notable that in each of these cases, the person engaging in unwanted pursuit was male, and, again, were either strangers or a person the MP had met in the course of their duties. There were six other responses where an MP indicated that they had experienced some form of unwanted pursuit, but further information was lacking to clearly determine whether their experience met the threshold for definition as stalking.

Associations with stalking versus harassment

There were no differences in gender, age, time in office or political alignment between MPs whose experiences of harassment met the stalking criteria and those whose experiences did not. Overall, the stalking group generally reported more unwanted pursuit behaviours and a longer duration of unwanted behaviour (median duration 20 months vs 6 months), but these differences were not statistically significant.

Experience of online abuse and threats

Of the 46 participants, 38 MPs (83%) said they were active on some form of social media (the remainder provided no response to the question). The four most common platforms used were Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn. With the exception of the two participants who did not provide any further responses, all but one MP using social media reported some experience of threats or abuse via these platforms.

The majority of MPs felt that the frequency of online threats and abuse had definitely (45%) or possibly (34%) increased in the two years prior to the survey. Only 16% of respondents felt there had been no change. Of MPs who had received abuse or threats via social media, 84% thought that the person(s) responsible was male.

Facebook was the predominant platform where online abuse or threats were experienced, partially reflecting the fact that all MPs had a Facebook presence, and it was the most commonly used social media platform by the general Australian community at the time this survey was conducted (Yellow, Citation2020). Only one MP reported that they had never received abuse or threats via Facebook. Twitter was the platform on which online abuse or threats were next most likely to occur, again likely reflecting the frequency with which this form of social media is used by both MPs and the community. LinkedIn was used less frequently by MPs, and the vast majority of those using it did not report abuse on this platform. Frequency of online abuse or threats ranged from less than once a year on a single social media platform, to daily abuse across multiple platforms. There was no relationship between the MP’s age or gender and the frequency of threats and abuse on any platform, apart from Twitter, where female MPs reported more frequent abuse (51.6% of women reported some experience of abuse on Twitter compared to 33.3% men). There were significant positive correlations between being abused or threatened via Facebook and receiving abuse or threats via Twitter (Kendall’s τ = .52) and Instagram (Kendall’s τ = .30). This indicates that those reporting abuse on one of these platforms often experienced abuse on multiple platforms.

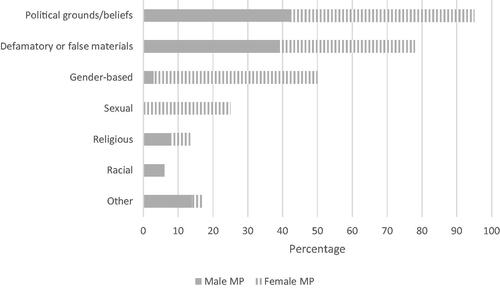

As shown in , the most common theme of online abuse was the MP’s political party or beliefs, followed by false or defamatory statements about the MP. Neither of these forms of abuse differed markedly by the MP’s gender. Abuse focusing on the MP’s gender (‘gender-based abuse’) was the third most commonly reported theme, affecting almost half of the sample. Of those reporting gender-based abuse, all but one was female, and gender-based abuse was reported by 85% of female respondents. Similarly, a quarter of MPs reported abuse containing sexually graphic threats such as rape or threats of sexual harm (‘sexual abuse’), all of whom were women (accounting for 55% of female respondents). Abuse on religious and racial grounds was relatively rare, perhaps reflecting the lack of religious and racial diversity in the Victorian Parliament (Zhou, Citation2021). ‘Other’ abuse included threats to the MP’s family, generic abusive language, or abuse pertaining to specific topics, such as climate change.

Of the 36 participants who responded to the question, 40% stated that those who had targeted them with abusive or threatening messages online had also targeted them offline (e.g. via telephone calls, letters or direct approaches). When asked to estimate the proportion of anonymous online abuse, MPs’ estimates varied widely, from more than 80% of abuse received anonymously in three cases, to less than 10% anonymous in six cases. In two thirds of cases, at least half of the abuse directed at MPs was from an identifiable person, while in the remaining third the majority of abuse was communicated from anonymous online accounts.

Explicit online threats

Explicit threats made to the 36 MPs via social media were diverse in content, with threats of reputational harm reported by 42% of those threatened (71% of male respondents vs 33% of female respondents). Threats of physical violence were reported by 16% of participants, targeting female MPs in all but one case (reported by 28% of responding female MPs). Similarly, threats of sexual violence were reported by 22% of women but no men. Other types of threat were reported by 13% of participants, evenly distributed by MP gender. In 7 cases there was no response to the survey question regarding type of threat, despite reporting abuse on social media.

When questioned about possible reasons for being targeted, 55% of the 36 MPs believed that the threats were motivated by their political beliefs. A further 29% believed the threats were based on their gender or sexual orientation, while 8% reported being threatened for other unspecified reasons. Again, while approximately equal proportions of male and female participants reported threats motivated by the MP’s political beliefs, threats motivated by the MP’s gender or sexual orientation were exclusively reported by female MPs.

MPs’ responses to online abuse and threats

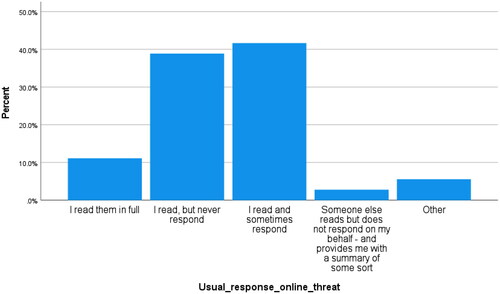

MPs reported a range of responses, with the majority reading the communication and either not responding or sometimes responding (). There were no marked gender differences in MPs’ responses.

The majority of the 36 MPs who reported online threats and abuse indicated that they always (24%) or sometimes (47%) deleted the messages. A substantial majority also reported always (34%) or sometimes (42%) blocking people who were being abusive or threatening online. Blocking was perceived to be effective by about a quarter of those who used this strategy, while 45% thought it was sometimes effective; 5% believed that blocking was ineffective in preventing abuse or threats online.

Impact of harassment, stalking and online abuse on MPs

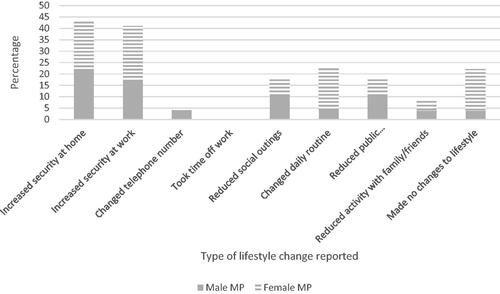

Twenty-eight MPs who had experienced unwanted approaches, stalking, threats, assault or online abuse reported adverse impacts on their lifestyle and well-being, with 22 (85%) reporting lifestyle changes in response (). Increased security at home and work were by far the most common responses. One MP acknowledged that they had looked at alternative employment and removing themselves from public life in response to the behaviour to which they had been subjected. Among those who reported no lifestyle changes, the substantial majority were women, despite women being more likely to report feeling concern or fear and experiencing threats of physical or sexual violence.

Figure 8. Percentage of MPs who reported lifestyle changes in response to unwanted approaches, threats, stalking, harassment and online abuse.

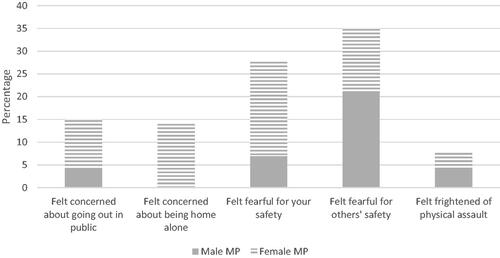

Half of the 28 MPs who responded indicated that they felt some fear as a consequence of the unwanted approaches, threats, stalking, harassment or online abuse (). Female MPs were more likely to report fear for their own personal safety, either in isolation or in addition to fear for those close to them (6 of 8 who reported fear), while male MPs were more likely to report exclusively being fearful for the safety of those close to them (4 of 6 reporting fear).

MPs identified mental or emotional stress (33% of female and 22% of male MPs) and damage to reputation (22% of male and 14% of female MPs) as the primary problems they experienced. A small number of MPs reported conflict with friends or family, or problems at work due to the intrusions.

Help-seeking by MPs

Given the frequency and impacts of the victimisation reported by MPs, it was prudent to explore where MPs sought help and the perceived effectiveness of these sources of help.

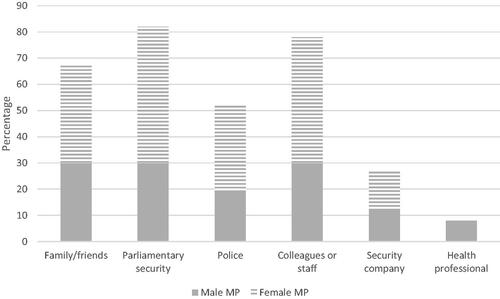

Of the 27 MPs who had experienced some form of harassment and responded to the help-seeking questions, the majority indicated they had sought assistance from someone else to manage the situation (). Most (80%) had reported the experiences to Parliamentary Security, colleagues or staff, and half reported the incidents to police.

Each MP was asked to rate the usefulness or otherwise of the help they obtained, from 0 (not at all useful/helpful) to 100 (completely useful/helpful). Responses varied widely, though for all forms of help-seeking, three quarters of the ratings were over 50, indicating that the majority of MPs who sought help found it to be at least somewhat helpful or useful.

Help-seeking MPs who consulted Parliamentary Security considered them to be quite useful or helpful. Half the MPs rated Parliamentary Security at least 75 out of 100 on the scale provided, with only 4 MPs rating it below 50. Only consulting family or friends received a higher rating (80 out of 100), and it could be surmised that the type of help received from family or friends would differ from that of Parliamentary Security. Private security companies were considered helpful by the majority of MPs who consulted them (half rating them at least 71 out of 100). Victoria Police were not considered to be particularly helpful or useful by a sub-group of MPs, but were perceived to be extremely helpful by others: 8 MPs rated police 0–54, while 6 MPs scored them 73–100.

Discussion

Harassment is commonly experienced by Victorian MPs

Overall, more than 80% of participating Victorian MPs reported unwanted communications or approaches by at least one person during their time in office. In this study, explicit threats were reported by over 60% of participants and, contrary to previous studies by Wallin and Wallin (Citation2014) and James, Farnham, et al. (Citation2016), appeared unrelated to MPs’ years in office or their political alignment. These findings are consistent with the rates of victimisation reported in other comparable surveys, particularly in the previous Australian sample of Queensland State MPs (Pathé et al., Citation2014).

Stalking – rigorously defined as per McEwan et al. (Citation2021) – affected at least a third of the Victorian sample. The overall rate of stalking is similar to that reported by James, Farnham et al. (Citation2016) and Narud and Dahl (Citation2015) and is approximately twice the rate of stalking reported in studies of the general community (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2016; McEwan & Pathé, Citation2013; Purcell et al., Citation2002). This is more remarkable for the fact that none of the respondents indicated that their pursuer was a former intimate partner. This latter group account for nearly half of stalking cases in the general population (ABS, Citation2016; Purcell et al., Citation2002). Even if all MPs who did not respond to the survey had never experienced stalking behaviours, the identified incidence could be extrapolated to a minimum rate of 12.5% of Victorian MPs, twice the rate of stalking victimisation reported by males in an Australian epidemiological survey (ABS, Citation2016). Although the experiences reported by proportionally more male MPs met criteria for stalking among those who responded fully to these questions (77% of male MPs versus 60% of female MPs), the small sample (only 24 MPs responded to all necessary items) and the fact that male MPs were more likely to have missing data on relevant items precludes firm conclusions about gender and stalking victimisation. Nonetheless, studies of stalking experiences in other professional groups have also shown male victimisation rates that are at least equivalent to those reported by female victims (Jutasi & McEwan, Citation2021). It is noted that many of the experiences reported by MPs would accord with the legal definition of stalking within Victoria, even if they did not meet the strict definition of stalking applied in the study.

Online harassment is ubiquitous

Consistent with the findings of the House of Commons online abuse survey (Akhtar & Morrison, Citation2019), this study observed that the occurrence of online abuse and threats is pervasive among MPs who use social media. Online threats to Victorian MPs most commonly focused on their political beliefs, targeting men and women in similar numbers. The most common perceived reason for online harassment – the MP’s political persuasion – highlights the prominence of resentment and grievances, not infatuation, as a driving force. Notably, online abuse does not happen in isolation, with just under half of the survey participants indicating that their abuser targeted them both online and offline.

Most participants considered that online abuse was a growing problem. Indeed, the first of the methodologically comparable MP harassment surveys was administered in the early 2000s, when email and social media were far less common, with only 10% of UK MPs reporting inappropriate social media contact at that time (James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016). Subsequent MP surveys have reported increasing rates of online harassment – 37% of Queensland MPs in 2011 (Pathé et al., Citation2014) and 60% of New Zealand MPs in 2014 (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015) – as the use and abuse of these platforms have increased in the general population. In the current study, all but one MP using social media reported some instance of threats or abuse via these platforms.

In a study of harassment and ‘uncivil interactions’ between citizens and US Members of Congress, Theocharis et al. (Citation2016) commented: ‘an anonymous platform for direct and publicly visible communication with one’s representatives can be a natural channel for citizens to communicate …. frustration in the form of heated remarks. (p. 1008)’ These authors acknowledged that although the interactive properties of social media can strengthen the relationship between MPs and their constituents, it is increasingly a tool for harassment. They also observed that politicians who make engaging use of Twitter are more likely to receive impolite or harassing tweets than those who confine their use of Twitter to a ‘broadcast’.

There are gender differences in the victimisation of Victorian MPs

There were notable gender differences in the experiences of participating MPs. More than a third of male MPs but only 4% of female members reported no experience of inappropriate contacts or communications. Women in this study were more likely to have been threatened than men and to report threats of physical and sexual violence, and they were more likely to be targeted based on their gender (whereas being targeted based on political beliefs was less divided). The online abuse of female politicians reflects high levels of misogyny online in general (Bartlett et al., Citation2014).

This study appears to confirm the hypothesis that while being an MP carries increased risk of abuse and threats, being a female MP changes the nature of the abuse and threats experienced and may result in greater overall levels of abuse and threat. There has been an increase in female MPs in the pursuit of gender equality, gender sensitivity and inclusivity among MPs and the community they serve, often through implementation of quotas (Hough, Citation2021). However, disproportionate harassment of female members and the fear it engenders is likely to discourage female representation. Furthermore, it threatens the proper functioning of parliament, as threats directed against female MPs can represent attempts to delegitimise women in politics and to restrict their right to communicate and participate in the political arena (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2016). Moreover, this is consistent with feminist theoretical positions that women are more likely to receive gender-based abuse, given patriarchal social structures and misogynistic attitudes (Manne, Citation2017) Parliamentary security services need to be aware of the nature and impact on these abuses on their female protectees.

Threats, harassment and stalking are harmful

Half of respondents reported experiencing fear as a result of victimisation, and in 85% of affected cases the harassment had caused disruptions to the MP’s lifestyle, most often through increased security at home and work, but also changes in daily routine, time off work and reduced social outings. Even if there was no victimisation of MPs who did not respond to this survey (which seems unlikely), these results suggest that nearly one in five Victorian MPs are making lifestyle changes in response to the experience of threats, harassment or stalking. The level of reported fear and distress was significantly higher if the MP had experienced unwanted approaches from their harasser. There is some justification for these concerns, given the importance to threat assessment professionals of any evidence of progression from ‘pre-approach’ behaviours (e.g. correspondence, telephone calls, online threats) to approaches, as one requires proximity to the target in order to attack (Meloy et al., Citation2004).

As in previous studies in the UK, Australia and New Zealand, fear was disabling in some cases, with 15% of MPs acknowledging concerns about public outings and of being home alone. Gender differences were again apparent in the levels of mental or emotional stress reported, being higher in female members. While fears for their own or others’ physical safety were at the forefront of their concerns, male MPs more commonly feared reputational damage.

Politicians share the risks of stalking victims in the general public, including fear and psychological and physical harm, but they have additional vulnerabilities. The harassment may lead to public embarrassment and disruption of parliamentary duties. While it was not asked in this survey, the Norwegian survey suggested that 17% of MPs had changed their position on an issue or not engaged on a topic due to victimisation (Bjelland & Bjørgo, Citation2014). Furthermore, the ubiquity of harassment towards parliamentarians means that policing resources may be diverted to relatively harmless offenders (the ‘background noise’), while the small number of people who present a genuine risk of physical violence are overlooked.

Not all sources of help are helpful

Like their peers surveyed in other jurisdictions, the majority of Victorian MPs who reported experiences of threats, stalking, online abuse or physical violence sought help to manage the situation. This is unsurprising, given the significant impacts on the majority of afflicted MPs discussed above. With the exception of MPs who sought help from police, most MPs reported benefit from their help-seeking. However, it remains unclear from this survey how often the resulting interventions effectively ended the intrusions. This is now the second survey to highlight that MPs frequently find police responses to be unhelpful in managing unwanted intrusive behaviour by the general public (the UK survey by James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016, reported similar findings). Over the past two decades, specialist units for responding to this kind of behaviour have become more common in liberal democracies (Barry-Walsh et al., Citation2020), but it is unclear whether MPs are routinely accessing these specialist services. The very divided views on whether police were helpful may indicate that some MPs who responded to this survey had accessed specialist help available through Victoria’s FTAC, while others had not, or simply that some police are better at responding to these kinds of issues. It is worth noting that many stalking victims in the general population have similarly dim views of police responses, suggesting that MPs may not be particularly remarkable in this regard (Taylor-Dunn et al., Citation2021).

A substantial majority of MPs who reported online threats and abuse indicated that they sometimes or always deleted problematic online messages. This suggests that MPs are responding to harassment in ways that may impede effective investigation and risk management. These counterproductive practices, and the role and availability of the specialist services available through FTAC units, could be addressed through awareness training for MPs and their staff.

Limitations

This study focused on intrusive and aggressive behaviours by members of the public towards politicians in the course of their parliamentary duties.

The modest participation rate in the Victorian survey was typical of most other studies of this nature. The exceptional response rate of 84% in the New Zealand survey (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015) was ascribed to politicians’ interest in the subject at that time. The small sample size in this study limited exploratory analyses of the associations of the reported behaviours. However, given it is possible that the 36% of Victorian respondents were not a representative sample, these findings should be interpreted with caution. It is conceivable that those who had experienced harassment during their time as an MP were more inclined to participate, but these MPs may, equally, have declined the survey to avoid rekindling stressful memories. Moreover, data collection coincided with the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has unleashed a groundswell of community tensions and problematic behaviours towards politicians, driven by the anger and uncertainty of job losses and deprivations, distrust in government and its responses to the crisis, and increased online activity during isolation and lockdown, exposing the vulnerable to disinformation and conspiracy theories (Cruickshank & Rassler, Citation2020; Williams, Citation2020). The effect of the pandemic on responses to this survey are unclear: while it may have encouraged some to participate who otherwise would not have, the workload and stress associated with the first year of the pandemic may also have reduced participation by MPs.

Respondents were not identified in this study, nor were their harassers. Their communications were not analysed. Some of the participants did provide helpful qualitative data, illustrating the nature and context of their experiences.

While the comparability of MP harassment surveys in Australia and Europe has been limited by variation in the behavioural definitions and constructs employed, the Victorian study adopted the questionnaire that was administered to Westminster parliamentarians (James, Farnham, et al., Citation2016; James, Sukhwal, et al., Citation2016) and subsequently adopted by studies conducted in Queensland (Pathé et al., Citation2014), Norway (Bjelland & Bjørgo, Citation2014) and New Zealand (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2015).

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the caveats outlined above, several key findings emerged from this study. Stalking and other harassment of POH is common, affecting the majority of Victorian MPs who responded to this survey, with at least a third experiencing serious stalking. MP gender has been inadequately assessed in most previous surveys, but in this survey female MPs were disproportionately threatened by members of the public, and they were far more likely to receive online threats of physical and/or sexual violence and gender-based abuse.

This survey highlighted the central and growing role of social media in abuse of MPs and the destructive impact that incursions from members of the public can have on parliamentarians carrying out their duties. While it was reassuring to find that affected participants sought help, these interventions were not necessarily consistent or evidence-based. This suggests a need for increased awareness and accessibility to expert advice, threat assessment and interventions.

Public figure protection is complicated by the fact that members of the public generally have a right of access to their MP. Politicians may feel under pressure to be more accommodating of the problematic behaviours of their constituents than many of us would tolerate. This study and similar surveys indicate that some MPs are more at risk than others of victimisation and its impacts. Parliamentarians who are new to the role, female and gender-diverse members, those who are more exposed and accessible, and MPs who experience stalking are particularly vulnerable. Although the wider impact was not explored in this survey, previous research demonstrates that MPs’ family and staff are also frequent targets (Lowry et al., Citation2015; Pathé et al., Citation2014; Sheridan et al., Citation2019). The vulnerability of parliamentarians can be minimised through education focused upon the nature of fixation, the associated risks, and strategies to respond effectively to abuse and/or behaviours that pose a threat to public figures.

The issue of online harassment is complex, and it calls for further research that weighs the advantages and disadvantages of social media use by public figures. Similarly, the gender differences apparent in this study require more detailed analysis, with larger, more representative samples, including individuals with non-binary gender identification. The implications of disproportionate gender-based abuse by members of the public towards female MPs are disconcerting, as any actions that discourage appropriate representation of today’s society in politics are a threat to the democratic process.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Lisa J. Phillips has declared no conflicts of interest.

Michele Pathé has declared no conflicts of interest.

Troy McEwan has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Melbourne (application number 1954685). and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jon Breukel, formerly of the Victorian Parliamentary Library and Information Service and Peter Lochert, former Secretary, Department of Parliamentary Services for their support and assistance in conducting this research. We would also like to thank all Members of Parliament who responded to the survey.

Notes

1 One-to-one meetings between MPs and constituents.

References

- Adams, S. J., Hazelwood, T. E., Pitre, N. L., Bedard, T. E., & Landry, S. D. (2009). Harassment of members of parliament and the legislative assemblies in Canada by individuals believed to be mentally disordered. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(6), 801–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940903174063

- Akhtar, S., & Morrison, C. M. (2019). The prevalence and impact of online trolling of UK members of parliament. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 322–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.015

- Amess, D. (2020). Ayes & ears: A survivor’s guide to Westminster. Luath Press.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. (2016). Personal Safety, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/personal-safety-australia/latest-release#articles

- Barry-Walsh, J., James, D. V., & Mullen, P. E. (2020). Fixated threat assessment centers: Preventing harm and facilitating care in public figure threat cases and those thought to be at risk of lone-actor grievance-fueled violence. CNS Spectrums, 25(5), 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920000152

- Bartlett, J., Norrie, R., Patel, S., Rumpel, R., Wibberley, S. (2014). Mysogyny on Twitter. https://demosuk.wpengine.com/files/MISOGYNY_ON_TWITTER.pdf?1399567516

- Bjelland, H. F., & Bjørgo, T. (2014). Trusler og Trusselhendelser mot Politikere: En Spɸrreundersɸkelse Blant Norske Stortingsrepresentanter og Regjeringsmedlemmer [‘Threats and threat events against politicians: A survey of Norwegian Members of Parliament and Government Officials’].

- Brottsförebyggande rådet [Crime Prevention Council]. (2012). Politikernas Trygghetsundersökning 2012; Fökningrtroendevaldas utsatthet och oro för hot, våld och trakasserier Rapport 2012:14 [Politicians: The security survey 2012: Elected officials, vulnerability and concern for threats, violence and harassment. Report 2012:14.

- Cruickshank, P., & Rassler, D. (2020). A view from the CT Foxhole: A virtual roundtable on COVID-19 and counterterrorism with Audrey Kurth Cronin, Lieutenant General (Ret) Michael Nagata, Magnus Ranstorp, Ali Soufan, and Juan Zarate. CTC Sentinel, 13(6), 1–34. https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CTC-SENTINEL-062020.pdf

- Every-Palmer, S., Barry-Walsh, J., & Pathé, M. (2015). Harassment, stalking, threats and attacks targeting New Zealand politicians: A mental health issue. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 634–641.

- Fein, R. A., & Vossekuil, B. (1988). Preventing attacks on public officials and public figures: A Secret Service perspective. In J. R. Meloy (Ed.), The psychology of stalking: Clinical and forensic perspectives (pp. 175–192). Elsevier.

- Fixated Research Group. (2006). Inappropriate communications, approaches and attacks on the british royal family, with additional consideration of attacks on politicians (Research Report). 68.

- Freudenberg, G. (2006). Calwell, Arthur Augustus (1896–1973). In Australian dictionary of biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Gill, P., Silver, J., Horgan, J., Corner, E., & Bouhana, N. (2021). Similar crimes, similar behaviors? Comparing lone-actor terrorists and public mass murderers. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 66(5), 1797–1804. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14793

- Hough, A. (2021, April 19). Quotas for women in parliament. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2021/April/Quotas_for_women_in_parliament

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2016). Sexism, harassment and violence against women parliamentarians. https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/issue-briefs/2016-10/sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-parliamentarians

- James, D. (2016, June 20). Some MPs think putting up with violent behaviour is part of their job. It isn’t. The Guardian: UK edition. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/20/mps-violent-behaviour-part-job-attacks-jo-cox-protection

- James, D. V., Farnham, F. R., Sukhwal, S., Jones, K., Carlisle, J., & Henley, S. (2016). Aggressive/intrusive behaviours, harassment and stalking of members of the United Kingdom Parliament: A prevalence study and cross-sectional comparison. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2015.1124908

- James, D. V., Kerrigan, T., Forfar, R., Farnham, F., & Preston, L. (2010). The fixated threat assessment centre: Preventing harm and facilitating care. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789941003596981

- James, D. V., Mullen, P. E., Meloy, J. R., Pathé, M. T., Farnham, F. R., Preston, L., & Darnley, B. (2007). The role of mental disorder in attacks on European politicians 1990–2004. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 116(5), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01077.x

- James, D. V., Mullen, P. E., Pathé, M. T., Meloy, J. R., Farnham, F. R., Preston, L., & Darnley, B. (2008). Attacks on the British Royal Family: The role of psychotic illness. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 36(1), 59–67.

- James, D. V., Mullen, P. E., Meloy, J. R., Pathé, M. T., Preston, L., Darnley, B., Farnham, F. R., & Scalora, M. J. (2011). Stalkers and harassers of Royalty: An exploration of proxy behaviours for violence. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.922

- James, D. V., Sukhwal, S., Farnham, F. R., Evans, J., Barrie, C., Taylor, A., & Wilson, S. P. (2016). Harassment and stalking of Members of the United Kingdom Parliament: Associations and consequences. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(3), 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2015.1124909

- Jutasi, C., & McEwan, T. E. (2021). Stalking of professionals: A scoping review. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 8(3), 94–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000160

- Lowry, T. J., Pathé, M. T., Phillips, J. H., Haworth, D. J., Mulder, M. J., & Briggs, C. J. (2015). Harassment and other problematic behaviors experienced by the staff of public office holders. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 2(1), 1–10. (https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000039

- Malsch, M., Visscher, M., & Blaauw, E. (2002). Stalking van bekende personen [Stalking of celebrities].

- Manne, K. (2017). Down girl: The logic of Misogyny. Oxford University Press.

- McEwan, T. E., & Pathé, M. (2013). Stalking. In G. Bruinsma, & Weisburd, D. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 5026–5038). Springer.

- McEwan, T. E., Simmons, M., Clothier, T., & Senkans, S. (2021). Measuring stalking: The development and evaluation of the Stalking Assessment Indices (SAI). Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 28(3), 435–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1787904

- Meloy, J. R., Hoffman, J., Guldimann, A., & James, D. V. (2012). The role of warning behaviors in threat assessment: An exploration and suggested typology. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 30(3), 256–279.

- Meloy, J. R., James, D. V., Farnham, F. R., Mullen, P. E., Pathe, M., Darnley, B., & Preston, L. (2004). A research review of public figure threats, approaches, attacks, and assassinations in the United States. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 49(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS2004102

- Millard, C. (2011). Destiny of the Republic: A tale of madness, medicine and the murder of a president. Doubleday.

- Mullen, P. E., James, D. V., Meloy, J. R., Pathé, M. T., Farnham, F. R., Preston, L., Darnley, B., & Berman, J. (2009). The fixated and the pursuit of public figures. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940802197074

- Narud, K., & Dahl, A. V. (2015). Stalking experiences reported by Norwegian members of parliament compared to a general population sample. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 26(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2014.981564

- Pathé, M., Phillips, J., Perdacher, E., & Heffernan, E. (2014). The harassment of Queensland Members of Parliament: A mental health concern. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 21(4), 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2013.858388

- Pathé, M. T., Haworth, D. J., Goodwin, T-a., Holman, A. G., Amos, S. J., Winterbourne, P., & Day, L. (2018). Establishing a joint agency response to the threat of lone-actor grievance-fuelled violence. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2017.1335762

- Pathé, M. T., Lowry, T., Haworth, D. J., Winterbourne, P., & Day, L. (2016). Public figure fixation: Cautionary findings for mental health practitioners. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 34(5), 681–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2252

- Purcell, R. M., Pathé, M. T., & Mullen, P. E. (2002). The prevalence and nature of stalking in the Australian community. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(1), 114–120.

- Purcell, R., Pathé, M., & Mullen, P. E. (2004). When do repeated intrusions become stalking? Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 15(4), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940412331313368

- Sheridan, L., Pyszora, N., Cooper, B., & Bendlin, M. (2019). Problematic behaviors experienced by electorate and ministerial office staff: Results of and responses to a Western Australian survey. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 6(3–4), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000130

- Taylor-Dunn, H., Bowen, E., & Gilchrist, E. A. (2021). Reporting harassment and stalking to the Police: A qualitative study of victims’ experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11–12), NP5965–NP5992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518811423

- Theocharis, Y., Barberá, P., Fazekas, Z., Popa, S. A., & Parnet, O. (2016). A bad workman blames his tweets: The consequences of citizens’ uncivil Twitter use when interacting with party candidates. Journal of Communication, 66(6), 1007–1031. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12259

- van der Meer, B. B., Bootsma, L., & Meloy, R. (2012). Disturbing communications and problematic approaches to the Dutch Royal Family. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 23(5–6), 571–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2012.727453

- Wallin, L., & Wallin, S. (2014). Politikernas Trygghetsundersökning 2013: Utsatthet och oro för trakasserier, hot och våld [Politicians security survey 2013: Vulnerability and concern – harassment, threats and violence].

- Williams, C. (2020). Terrorism in the era of Covid-19. The Strategist. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/terrorism-in-the-era-of-covid-19/

- Wilson, S. P., Pathé, M. T., Farnham, F. R., & James, D. V. (2021). The Fixated Threat Assessment Centers – the joint policing and psychiatric approach to risk assessment and management in cases of public figure threat and lone actor grievance-fuelled violence. In J. R. Meloy & J. Hoffmann (Eds.), International Handbook of Threat Assessment (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Yellow. (2020). Social Media Report 2020: Part 1-Consumers. https://www.yellow.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/07/Yellow_Social_Media_Report_2020_Consumer.pdf

- Zhou, N. (2021, August 6). Australia’s state parliaments lagging on racial and cultural diversity, report finds. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/aug/06/australias-state-parliaments-lagging-on-racial-and-cultural-diversity-report-finds