ABSTRACT

The attractiveness of a city is an issue that has received much attention from scholars, regulators and authorities. In terms of a built environment, many attempts have been made to build an attractive city with its own identity through pattern language and form language; however, these languages are developed based on the language of geometry and on how human beings interact with their surrounding environment. Meanwhile, multiple studies on the factors that create motivation to attract visitors to a certain place (e.g. motivation theory) also identified the factors that makes a city attractive, but such studies are still general, incomplete, and only focus on the perspective of tourists. This research builds a system of factors that contributes to urban attractiveness from the perspective of both visitors and residents, through qualitative research methods such as Group Focused Discussion, In-depth Interview and Capture Evaluation Method Survey. The research findings discovered many more factors that affect urban attractiveness and then built nine Conceptual categories of Urban staycation Attraction Factors with 141 factors. The nine main categories are (1) Architectural and Built Environment, (2) Natural, (3) Works of Art and Humanity, (4) Folklore, (5) Community Civilization, (6) Green & Blue Infrastructure, (7) Sense of Place, (8) Services, and (9) Other. Moreover, the research also determined 134 factors that contribute to the attractiveness of Ho Chi Minh City and proposed an additional six important groups of factors that need to be developed to improve urban quality. These findings play an important role in supporting regulators, authorities, urban planners, designers, and tourism and cultural managers to enhance quality of urban life, then create an attractive urban environment for both tourists and local residents.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The outbreak of COVID-19 brought about unprecedented changes which can be seen as either positive or negative, but there is no doubt that these changes have had a direct impact on human lifestyle. A significant series of events at that time included blockades and restrictions in movement in many areas of Vietnam, especially in the bigger cities.

Restrictions in movement, and even blockades, are said to exert adverse impacts on people’s lives, especially raising the issues of the economy and mental health (Borio Citation2020; Hossain et al. Citation2020; Kumar and Rajasekharan Nayar Citation2021; Muritala, Hernández-Lara, and Sánchez-Rebull Citation2022; Talevi et al. Citation2020)

Indeed, social interactions and exposure natural surroundings are strongly associated with mental and physical health of different age groups (Pachucki et al. Citation2015; Steptoe and Di Gessa Citation2021; Sugiyama et al. Citation2008). Stress Reduction Theory and Attention Recovery Theory also highlights the importance of exposure to green settings by consistently encouraging an individual’s capacity to pay attention and reducing psychological and physiological symptoms of stress (Kaplan Citation1985).

Staycation is a portmanteau of stay and vacation that implies a period in which people stays home and participates in leisure activities within day trip distance of their home, which does not require overnight accommodation. This term prevailed in the US during the economic crisis of 2007–2010 and became globally common in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fox Citation2009; Muritala, Hernández-Lara, and Sánchez-Rebull Citation2022). Staycation plays a critical role, in not only encouraging leisure activities within a neighborhood but also, developing an economy by promoting sustainable tourism (Muritala, Hernández-Lara, and Sánchez-Rebull Citation2022). Recently, the research of Wong et al. (Citation2023) reinforces the idea that staycations help improve the psychological wellbeing of participants through short local excersions. Furthermore, this research also clarifies the new form of mental sustainability through psychological values associated with a staycation (Wong, Lin, and Esther Kou Citation2023).

Since 1980, urban spaces and cities have become increasingly important within the framework of contemporary international tourism. It has been possible to observe a gradual touristification of many cities and also an urbanization of the tourist experience (Sirkis et al. Citation2022). That is to say, cities have become more attractive as tourist destinations.

Scholars seek theories to build an attractive and distinctive city to serve the quality of people’s lives. Typically, in the book The Image of City, Kevin Lynch identified the elements of urban spatial layout on the basis of visual perception of urban images that include nodes, paths, districts, landmarks, and edges (Lynch Citation1960). This theory focuses on building an attractive city through form language that includes geometrical rules for putting matter together. Meanwhile, Christopher Alexander, in the book A Pattern Language, defined the language system for design through the so-called pattern language (Alexander Citation1977). Pattern languages contain rules for building the patterns of human interaction with built forms surroundings (Nguyen Citation2015; Salingaros Citation2000). Motivation theory suggests that pull factors and push factors help create a motivation for people to choose a travel destination over other places (Dann Citation1981; Zhang and Peng Citation2014). The attractiveness of a city is shown through its identity, which is constituted by both physical and non-physical features.

It can be seen that the above theories focus on a single dimension of creating an environment to interact with people. Kevin Lynch focuses solely on satisfying people’s visual needs through the geometric properties of the built environment; Christopher Alexander focuses on people’s perception and behaviors towards the built environment to diversify the pattern of human experience in that space. Meanwhile, the attractiveness of a city or a certain place from the user’s point of view is diverse and complicated, but the sole use of theories proposed by Lynch and Alexander is not enough to meet people’s different demands. Moreover, the relationship between the two mentioned theories during the process of identifying the attractive factors of a city is still limited to urban geometrical elements (Nguyen Citation2015). Similarly, motivation theory focuses on understanding the internal and external forces of people to build an activated behavior. This theory is a broad topic that is categorized into two main groups: content and process. Content models of motivation focus on what people need in their lives (i.e., what motivates them). Process theories look at the psychological and behavioral processes that affect and individual’s motivation. In social science, current studies also focus on understanding the forces behind a particular type of behavior instead of considering a series of physical and non-physical factors to form a series of different behaviors in order to achieve the attractiveness perception of a place or built environment.

The staycation appeal of a certain place in a city is strongly linked to both the perception of tourists and residents. Indeed, the interdependence between attractiveness as perceived by tourists and attractiveness rooted in the relationship of local residents with the place is key to addressing the attractiveness or identity of urban areas.

1.2. Research status

Research on the attractiveness of a city involving staycations or tourism was carried out. Typically, Alhazzani et al. (Citation2021) identified urban attractors through the concept of points of interests in the road network. This research also determined attraction patterns based on the number of visitors, distribution of distance traveled by visitors and spatial spread of the origin of visitors. However, this approach could lead to inaccuracies in identifying urban attractors because the method of identifying points of interests is limited in cases of congestion arising when visitors move around in the street network (Alhazzani et al. Citation2021). In addition, this research has not yet identified specific attractiveness factors.

Another research of Kobi Cohen-Hattab and Katz (Citation2001) studied the role of a place’s history in creating attractiveness. This article indicated that attraction factors, supply and demand helped build tourism infrastructure (Cohen-Hattab and Katz Citation2001). Nevertheless, this research only focuses on an historical perspective instead of all aspects of an ordinary city.

A series of other studies went further to identify conclusions in relations to tourism attraction factors of a city. In particular, Gabriela Sirkis (Citation2022) examined the tourist’s recognition of different attractions and proposed four main factors that affect a tourist’s attraction of a city including (1) the nucleus, (2) the tourism ecosystem, (3) Meetings, Incentives, Conventions and Exhibitions/Events (MICE) and shows, and the (4) related services (Sirkis et al. Citation2022). However, this research only considered cities in Latin America rather than worldwide. In addition, the research findings only identified the overall attributes of a city’s attraction factors. Boivin and Tanguay (Citation2019) studied the tourist’s perceptions of a city at four different levels including context, tourist belt, complementary attractions, and nucleus (Boivin and Tanguay Citation2019). Still, these findings are not generalizable. Indeed, different cities have their own characteristics and attractiveness.

Identity and attractiveness of a place are explained in literature in many ways according to objectives and fields involved. Some suggest that a city’s attractiveness mainly focuses on physical features which include physical elements and its layout. Others argue that the attractiveness of a city is determined by, not only environmental features but also, memories and the symbolic meanings. Identity in this sense refers to the characteristics of the place as perceived by people (Bernardo and Manuel Palma-Oliveira Citation2012).

Numerous studies on tourism attractiveness variables of a city concluded that the main variables that attract visitors include historic buildings, urban neighborhoods, and special events. Meanwhile, secondary variables are related to infrastructure that a city provides to visitors (Ashworth and Page Citation2011; Chan et al. Citation2018; Crouch Citation2011; Jansen-Verbeke Citation1986; Wang, Fang, and Law Citation2018). The studies only focuses on visitors instead of learning about the perception of all users.

In terms of staycation research, Pawłowska-Legwand and Matoga (Citation2016) studied tourism products and assessed the connection of staycations with the current demands of residents. The local cultural heritage and the natural environment are considered fundamental to the formation of urban attractiveness (Pawłowska-Legwand and Matoga Citation2016). The research of Jeuring and Haartsen (Citation2017) clarified subjective understandings of both distance and proximity in relation to perceived attractiveness of and touristic behavior in places near home (Jeuring and Haartsen Citation2017). The research finding also indicated both distance and proximity are important variables in staycation tourism. However, these studies only look at the distance-related aspect of staycation decision-making.

1.3. Objective and significance of research

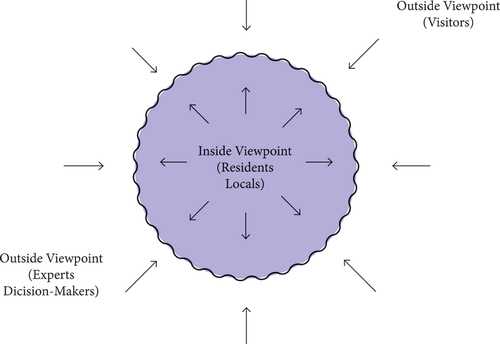

Urban staycation attraction relates to urban identity or/and attractiveness, which involves theories of the competitiveness of tourist destinations. Indeed, urban tourist attractions are the key factor for the competitiveness of these destinations (Crouch Citation2011; Mikulić et al. Citation2016; Xinhua, Sheng, and Lei Citation2022; Zehrer and Hallmann Citation2015). Similar to determining urban identity through the point of view of different users, urban staycation attraction is examined from two points of view (): (1) one by which a place is seen as a source of identity and as contributing to the collective identity of its residents (Bernardo and Manuel Palma-Oliveira Citation2012) and (2) the external observer’s viewpoint that focuses on what makes a place attractive.

This research, therefore, attempts to identify the factors that attract staycations from both tangible and intangible aspects. The main objective of this paper is to identify determinants and conceptual categories of urban staycation attractiveness that emphasize the importance of including both points of view, and thus contribute to impact of urban design and management on tourism, staycation development and mental sustainability.

The research findings provide urban managers, tourism managers, urban designers and urban planners with a fundamental conceptual category to develop an attractive and distinctive city. The research findings also provide a scientific basis for identifying the attractive elements of a city. The findings answer the question of which elements shape peoples’ place perceptions or the attractiveness of a place. Depending on the mentioned determinants and conceptual categories, this research specifies the attractive elements of Ho Chi Minh City, thereby clarifying the main conflicts that occur in preserving and developing the uniqueness and attractiveness of a city.

2. Materials and methods

Having gone through multiple stages, this research explores determinants and conceptual categories of urban staycation attractiveness based on different perspectives. A methodology framework was developed to specify research goals and methods accordingly ().

At an early stage, a literature study was carried out to conclude the main dimensions of urban attractiveness. In the second stage, based on the main dimensions drawn from the first stage, a series of different surveys were conducted to determine urban staycation attractiveness factors.

2.1. Urban staycation attractiveness

Urban attractiveness is recognized through two indicators perceived by residents and visitors (Romão et al. Citation2018). A city’s attractiveness is also recognized through urban identity and territory of residents (Servillo, Atkinson, and Paolo Russo Citation2012). Urban attractiveness is shown through different functional indicators of the economy, environment, livability, accessibility, cultural interaction, research and development (Romão et al. Citation2018).

This research conducted a literature review of the afore mentioned different indicators under the perspective of urban tourism/staycation attractiveness. The theory of the competitiveness of tourist destinations suggests that a place can become more competitive when it provides more valuable products and services to visitors who are using basic resources and visiting attractions in a place (Crouch Citation2011; Enright and Newton Citation2004; Xinhua, Sheng, and Lei Citation2022).

Variables related to urban staycation attractiveness are the attributes of a place such as geography, climate, weather, culture, history, activities available for visitors, entertainment options, natural attractions, and built infrastructure or structure (Ashworth and Page Citation2011; Chan et al. Citation2018; Crouch Citation2011; Jansen-Verbeke Citation1986; Wang, Fang, and Law Citation2018). The main tourism attractiveness variables are also those that determine the destinations of tourists which include historic buildings, urban neighborhoods, and special events. Meanwhile, secondary variables include social infrastructure that is offered to visitors including shops, convention centers, lodgings, and transportation (Jansen-Verbeke Citation1986).

Studies on variables impacting urban tourism attractiveness suggested four groups as follows: (1) Variables related to the social infrastructure of a place, such as hotels and shops (Ashworth and Page Citation2011; Enright and Newton Citation2004; Hurst and Niehm Citation2012); (2) Variables related to the history and culture of a place, such as museums and monuments, festivals, cultural attractions, historical – cultural heritage, lifestyle, nightlife and gastronomy (Ashworth and Page Citation2011; Borges, Cunha, and Lopes Citation2021; Brida, Meleddu, and Pulina Citation2012; Campa et al. Citation2019; Fraiz, de Carlos, and Araújo Citation2020; Mariani and Okumus Citation2022); (3) Variables related to urban life such as transportation, tourist information, signage at the destination, and public spaces, which affect the destination’s image (Jansen-Verbeke Citation1986; Mikulić et al. Citation2016; Romão and Bi Citation2021); (4) Variables related to the sustainability of the destination and environmental sustainability (Boivin and Tanguay Citation2018; Rigall-I-Torrent Citation2008).

There is a combination of needs and desires when a visitor decides on a place to visit (Meng, Tepanon, and Uysal Citation2008). According to the motivation theory, pull factors and push factors could help explain why a person chooses a travel destination (Dann Citation1981; Gnoth Citation1997; Prayag and Hosany Citation2014; Uysal and Jurowski Citation1994; Zhang and Peng Citation2014). This theory suggests that pull factors come from a travel destination and attract visitors to visit. Pull factors consist of tourist sites, historical attractions that are relevant to their cities’ heritage, entertainment facilities (Romão et al. Citation2015; Lim and Giouvris Citation2020; Crompton Citation1979; Van der; Merwe, Slabbert, and Saayman Citation2011; Bansal and Eiselt Citation2004; Andreu, Enrique Bigne, and Cooper Citation2000), urban tourism landscape (García-Hernández, De la Calle-Vaquero, and Yubero Citation2017), and sustainable urban tourism (Miller, Merrilees, and Coghlan Citation2015).

Although pull factors are described in the motivation theory, scholars state that these factors vary across different cities and places. For example, in the research of Bozic et al. (Citation2017), pull factors that attract tourists the most are cultural events, entertainment, nightlife, shopping, festivals, and gastronomy (Bozic et al. Citation2017). Meanwhile, in China, Wu and Wall (Citation2017) indicated that heritage sites and museums are the most important pull factors (Wu and Wall Citation2017). Other attractive factors such as smart cities, cultural dynamics, the sustainability of a place and the pro-environmental behavior of the visitors are also important (Miller, Merrilees, and Coghlan Citation2015; Romão et al. Citation2018).

On the other hand, push factors arise from the psychological impulse of visitors. These factors are their intrinsic motivations that come from a need to relieve stress, build new connections, make a discovery, learn new things, and “get away from it all”(Van der Andreu, Enrique Bigne, and Cooper Citation2000; Botha, Crompton, and Kim Citation1999; Merwe, Slabbert, and Saayman Citation2011). Push factors help address emotional imbalances that people experience in their social and work environments. To some extent, these factors are also relevant to urban attraction factors.

To cover all general factors of urban attractiveness, when a city is seen as an attractive destination, four dimensions were suggested based on the collection and analysis of all the factors proposed in previous studies, including (1) Heritage & Identity: Staying in the city means to get to know a city, its identity, its characteristics, to fall in love or to dislike its overall character. What constitutes heritage and identity? And how does that relate to being able to stay in your own city, to feeling at home or to receive people in a city?; (2) Publicness and Nature: Making a city livable means having openness in density. In a city, where so many people are living together in a small area, means the pooling of space and resources are necessary. Where do we find publicness in the city? What typologies do you find? How does nature appear here? How can this evolve to become a resilient city in the future?; (3) Daily Life and Hospitality: A livable city is a hospitable city, friendly to local and non-local visitors. Citizens can discover their own city, take walks, have a drink somewhere, or use their city as a living room. Visitors from afar can be received by this area’s citizens. How do we make our city friendly and hospitable towards each other? How do we receive people, and how will that occur in a resilient city?; and (4) Local Economy and Creativity: A livable city is a city where we can do lots of things, not only sleep and eat, but also create, make and produce. “A good city has industry.” How can we connect cultures? How can we make a city more resilient? How can we create local and resilient jobs? Who makes this city unique?

2.2. Field survey/investigation strategy

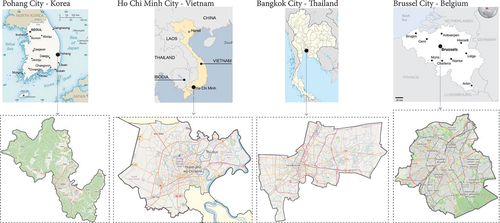

This research was conducted using qualitative methods and over two different survey phases. In the first stage, an international survey was carried out to collect data from responders in four countries (i.e., Vietnam, Thailand, Belgium, and Korea) and then the research built a fundamental conceptual category in regard to urban staycation attractiveness factors. In the second stage, a field survey was carried out in Ho Chi Minh City to identify the attractive factors of the city based on variables developed in the first stage ().

2.2.1. Focus group discussion

Focus Group Discussion (FGD) is a qualitative research method and a data collection technique in which a selected group of people hold an in-depth discussion on a given topic or issue, assisted by a moderator (). This method is used to ask participants for their attitudes, perceptions, knowledge, experiences, and practices, which are shared during interactions with different people (Hennink Citation2013). This technique is based on the presumption that group processes enabled in FGD helps determine and clarify knowledge shared among communities and groups, which would be otherwise hard to achieve through a series of individual interviews. However, this method does not assume that (a) all knowledge is equally shared amongst a studied group; or (b) each community has a common, fundamental, consistent knowledge. Instead, FDG allows investigators to learn about participants’ shared stories and their differences in terms of experiences, perceptions, and world views in such “open” discussion rounds. The discussion took place in two rounds ():

Table 1. Characteristics of focus group Discussion (FGD).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants of the first stage of investigation.

Round 1 – A National Group Discussion (22 January 19 to 26 February 2021) was held face to face to discuss four dimensions that consist of identity/heritage, open space, lifestyles, and local economy. Also, survey participants could spot local staycation opportunities in their cities generally based on their personal experiences and data extracted from the hands-on survey.

Round 2 - Mixed Group Discussion (from March 1st to 5th, 2021) was held to discuss, spot, and classify local staycation opportunities from a global perspective through online tools (e.g., Google Meet, Miro board, Discord and Cisco).

The project leader selected representive participants from four countries based on convenience sampling. This method allows the selection of representive samples of countries in their interconnection network. Subsequent participants were then selected by the representive of each country based on snowball sampling. As a purposeful method of data collection in qualitative research, snowball sampling has the strength in choosing samples with the target characteristics that are not easily accessible and with the attendees of educational programs or samples of research studies (Naderifar, Goli, and Ghaljaie Citation2017). In fact, this research requires participants to have interests and awareness about the research topic, thus snowball sampling can be effectively used to analyze special groups or individuals who have particular experiences.

2.2.2. In-depth interview

The technique of face-to-face interviews was used to solicit open data from interviewees about attractive destinations, hidden gems, and other factors that makes a place, or a city where they live, attractive. This interview data were collected through a hierarchical structure to maximize information. The hierarchical structure and information about participants in the survey are illustrated in and .

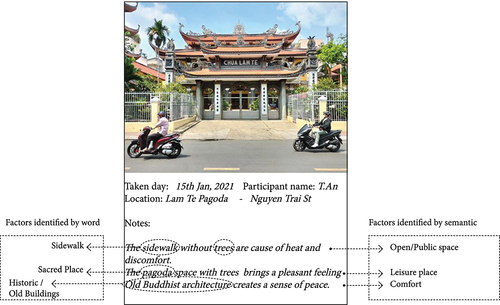

2.2.3. Capture evaluation method survey

CEMs is a method applied by Koga based on Noda’s PPM (photo projective method) and the “Evaluation Grid Method” proposed by Sanui and Inui (Koga et al. Citation1999; Sanui and Inui Citation1986). Noda’s photo projective method is a psychological method to understand the perceptions of participants in the survey through the photos they take. Over the years, this method has been commonly used in the field of urban architecture (Neto et al. Citation2016).

This method allows participants to experience the real environment and freely discover factors/elements that they care about or encounter. Participants move freely around the survey area in the center of Ho Chi Minh City and use their cameras to take the photos of a factor that is thought to attract their attention or be an attraction for them, then make a report card describing that factor.

The responses were collected from 25 participants (8F, 17 M) who are architecture students and architectural experts. Some researchers presume that there is no difference in the perceptions of architects and laypeople in assessing factors related to attractiveness as well as urban characteristics (Nasar Citation1994), so it is appropriate to choose participants from the field of architecture. CEMs was conducted from 17 February 2023 to 9 March 2023 which falls in the dry season with hardly any rain and low average humidity. This time has ideal weather conditions for tourists and local people to experience different activities.

A total of 485 report cards were interpreted semantically and classified into groups by similarity via an Affinity Diagram (sometimes called the KJ method), which helps identify elements/factors contributing to urban staycation attractiveness in Ho Chi Minh City ().

2.3. Research area

Because the purpose of this study is to explore the qualitative data, the strategy of selecting the research area based on how participants are familiar with the research area maximizes the data efficiency.

For selection of countries, four nations (Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, and Brussels) were selected based on convenience sampling which related to paticipant selection process and mentioned in Focus Group Discussion section. Even so, it still covers both Western and Eastern nations.

For city selection, four universities that participated in FGD are located in the four mentioned cities. Hence, participants selected the city with which they are most familiar. All cities have their own long history and functions for both locals and tourists.

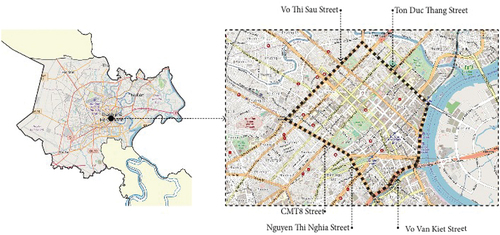

In Stage 1, this research selected four different cities in four countries based on their long history of development and the roles of urban areas in socio-economic development. The selected areas include: (1) the center of Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam); (2) Brussels (Belgium); (3) Bangkok (Thailand); (4) Pohang (Korea) ()

In the second batch of investigations, the center of Ho Chi Minh City, which has a long history of development and also functions as home to both locals and expats, was chosen for the survey. Because staycation attractiveness factors are considered attractive not only to travelers but also locals, the selected area in below is suitable for identifying the attractive factors of Ho Chi Minh City.

3. Results

3.1. Urban staycation attractiveness factors

The survey findings of Stage 1 (Focus Group Discussion) were collected through two survey rounds including national and international rounds; then, urban staycation attractiveness factors were classified into nine main categories as follows: (1) Architectural & Built Environment, (2) Natural, (3) Works of Art & Humanity, (4) Folklore, (5) Community Civilization, (6) Green& Blue Infrastructure, (7) Sense of Place, (8) Services, and (9) Others. The details of factors in each main category can be found in.

Table 3. Conceptual categories of urban staycation attractiveness factors.

In group 1 (Architectural and Built Environment): there are 11 Heritage and Identity Dimension factors including Historic Buildings, Old Buildings, Traditional Buildings, Traditional Markets, Monuments, Shophouses/Localshops, Co-housing, Local Material/Technology, Landmarks, War remnants, Archieological; one Publicness and Natural factor (e.g., Street Market); nine Daily Life and Hospitality Dimension factors including Houses/homes, Workplaces, Sacred Places, Leisure Places, Indoor Sports, Educational Places, Food Node/Spots, Accomodation, Restaurants; 19 Local Economy and Creativity Dimension factors that contribute to urban attractiveness and consist of Pop-up Urban Spaces, Mini Buses Decoration, Galleries, Skate Parks, Interactive Spaces, Temporary use of vacant places/buildings, Using the public building as perfomance places, Walking Streets, Cultural Centers, Handicraft & Art Shops, Workshop Places, Street Vendors, Street Stalls, Burden Streets, Grocery Stores, Shopping Malls, Cafe Shops, Bars, Beauty Salons.

In group 2 (Natural), there are three factors, including factors Geomorphological Topography, Natural landscapes, and Climate.

Group 3 has 12 factors, being Works of Art and Humanity factors. Most of the factors in this group come from Heritage and Identity Dimension such as Musical instruments, Ideologist/Book, Local craftmanship, Local artists, Local fashion.

Local products, Posters, Street art, Paintings/Pictures, Sculptures, Antiquities; Graffiti is the sole factor that belongs to Local Economy and Creativity Dimension.

Group 4 (Folklore) has 16 factors, among which there are nine Heritage and Identity Dimension factors including: Traditonal food, Traditions/Legends, History events/Local festivals, Traditional music/Folk music, Ceremonies, Worshiping customs, Traditional dance styles, Traditional sports, Belief/Religions. Daily Life and Hospitality Dimension has seven factors including Multicultural societies, Multi religions, Relaxation and enjoyment, Beverages, Open mindedness, Being friendly, Guides.

Group 5 (Community Civilization) has 14 factors distributed in the following groups: there are five Heritage and Identity Dimension factors including Language, Indigenous knowledge, Ideology, Culture of agriculture, Traditional beauty standards; the only factor that belongs to Daily Life and Hospitality Dimension is Coffee/Tea culture; Local Economy and Creativity Dimension has eight factors Stories/gossip, Local broadcasts, Competitions, Quality label/Mark/Brand value, Perennial brands, Maketing skills, Online presence, Advertisements.

Group 6 (Community Civilization) is recognized through 20 factors, among which Heritage and Identity Dimension factors include Alleyways, Transport and mobility; Publicness and Natural factors include Sidewalks, Subways, Public buildings, Public squares/Plazas, Streets, Parks, Couryards, Public transport, Open spaces, Green spaces, Greenery, Water surfaces, Trails, Bike paths, Trees, Beaches, Species, Bus stations.

Group 7 (Sense of Place) has ten factors, most of which come from Publicness and Natural Dimension with eight factors such as Sound, Smell, Crowds, Safety/lack of safety, Cleanliness, Tidiness, Comfort/Discomfort, Huge intensity of space; the two remaining factors including Friendly alleys and Friendly neighborhoods belong to Daily Life and Hospitality Dimensions.

Group 8 (Services) includes 17 factors provided or equipped or the city. Among them, Publicness and Natural Dimension has eight factors such as Evening activities, Commercial activities, Various functions, Freely accessible, Community cohension, Clean air, Recreation, and Hazard protection. Daily Life and Hospitality Dimensions has six factors including Trading, Internet, Street performances, Communication with people, Interaction in the streets, and Social interaction. Local Economy and Creativity Dimension has three factors including Pedlars, Shippers, and Local tour guides.

Finally, group 9 (Other) only records two factors including Garbage and Jobs which belong to Daily Life and Hospitality Dimension.

3.2. Staycation attractiveness factors of Ho Chi Minh city

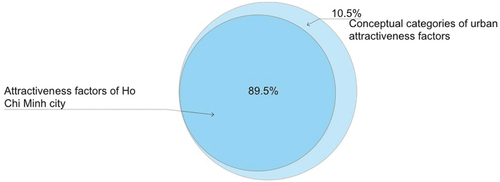

As can be seen in , the survey data from CEMs indicated that 89.5% of factors mentioned in Conceptual categories of urban staycation attractiveness factors () overlap with urban attractiveness factors in Ho Chi Minh City and 10.5% of the factors (14 factors) are not recognized. Factors that are not discovered in the case of Ho Chi Minh City include: Skate Parks, Public buildings as performance places, War remnants and Archaeological aspects that belong to Architectural and Built Environment; Musical Instruments and Ideologist/Books that come from Works of Art and Humanity; Traditional Dance Styles and Traditional Sports in Folklore; Subways, Trails, Bike Paths, and Waterfront/Beaches in Green & Blue Infrastructure; and finally Hazard Protection as the only Services factor.

Figure 6. Attractiveness factors of Ho Chi Minh overlaps with conceptual categories of urban attractiveness factors.

Likewise, differences in cultures and lifestyles, these different factors show up because the specific characteristics of infrastructure, economy, and urban structure in Vietnam are different from those of other countries.

4. Discussions

4.1. Expanding conceptual categories of urban staycation attraction factors

When comparing the findings of this research with previous studies, we can see certain overlaps and differences between urban attractiveness factors from a perspective of visitors and residents ().

Semantic overlaps that are found in previous studies include: (1) Historical/cultural heritage, which is clarified and specified through the main categories such as Architectural and Built Environment, Works of Art and Humanity, Folklore, Community Civilization; (2) Lifestyle semantically overlaps with Folklore; (3) Signature of place is an attractive factor described in previous studies (Jansen-Verbeke Citation1986; Mikulić et al. Citation2016; Romão and Bi Citation2021), but in this research, this factor is classified and detailed through the main categories such as Architectural and Built Environment, Natural, Works of Art and Humanity, Folklore, Community Civilization, Green & Blue Infrastructure, Services; (4) Entertainment Options includes such specific categories as Architectural and Built Environment, Natural, Works of Art and Humanity, Folklore, Community Civilization, Services.

Figure 7. Comparative analysis of conceptual main categories of urban staycation attractiveness and its factors between this research and previous researchs.

Only eight urban attractiveness factors in this research overlap with factors in previous studies. This suggests that this research greatly expanded urban attractiveness factors to 134 factors detailed in the above.

Compared with previous studies, eight factors that are not found in this research include Convention Centers, Climate/Weather, Pro-Environments, Gastronomy, Smart city cultural dynamics, Nightlife, and Sustainable urban tourism. To explain this difference, one understandable reason is that from the angle of staycation, the mentioned factors are beyond the concern of visitors or travelers. Indeed, for example, from the perspective of staycation, people have no need to stay, and are not concerned about climate adaptation because those who choose staycation tourism are usually not those who come from regions with large difference in climate and weather (Fox Citation2009). However, to expand and perfect the Conceptual categories of Urban Attraction Factors, it is necessary to add these seven factors to the group of urban attractiveness factors and build the conceptual categories with 141 factors.

4.2. Implications for livable Ho Chi Minh city

Research findings indicated that Ho Chi Minh City has sufficient factors that contribute to urban attractiveness. Therefore, this city holds a strong attraction for both international and domestic travelers.

However, scholars, authorities, and administers have not yet recognized urban attractiveness from the overall view of a system of factors, but only focused on isolated factors such as waterfront urban landscape heritage (Tam Citation2022); focused on local culture and architectural heritage (Pham Citation2018, Citation2019); life on sidewalks (Kim Citation2015).

This research stated that the creation of urban attractiveness and identity needs a consistent and simultaneous combination of different factors.

To optimize the attractiveness of Ho Chi Minh City, apart from maintaining 134 factors mentioned in the section 3.2, it is necessary to pay attention to developing other factor groups as follows: (1) space for the activities of younger generations such as Skate Parks, Public buildings for performance places; (2) develop and renovate space for sightseeing and exploration activities such as War Remnants and Archaeological; (3) develop and provide spaces and infrastructure for commuting, physical, and recreational activities such as Subways, Trails, Bike Paths, and the Waterfront; (4) develop a service system of securing, warning, and protecting visitors against dangers (e.g., Hazard Protection); (5) administers need mechanisms to develop and highlight the roles of Ideology/Philosophy in the society to create urban attractiveness (e.g., Japanese Tea Ceremony); (6) develop and recover various types of folk games, folk arts, and centers for cultural and folk art exchanges.

5. Conclusions

Urban attractiveness is explained through various secondary concepts. Scholars have attempted to build different theories that contribute to the construction of a more attractive city. Although theories on pattern language and form language coined by C. Alexander and K. Lynch were developed to build an attractive city and improve the quality and image of space, their scope of application is at a macro scale and not specific as yet. Meanwhile, such theories as a motivation theory identify the attractiveness of a place through the lens of tourism. This research learned about urban attractiveness from the perspective of different scientific fields.

This research is also an independent study that aims to confirm previous studies by comparing variables and factors that affect urban attractiveness. Research findings expand and systematically build the comprehensive conceptual categories of urban attractiveness factors including 141 factors that contribute to creating urban attractiveness. These micro-level factors can be used to develop criteria that evaluate the attractiveness of cities all over the world.

For the case study of Ho Chi Minh City, 134 urban attractiveness factors were identified, which proves that Ho Chi Minh City has a diversity of attributes to build an attractive city. However, urban administrators, planners, and designers still focus on single factors instead of developing and renovating a system of factors consistently and comprehensively. Therefore, it is essential to have policies to develop them consistently. Moreover, Ho Chi Minh City needs to consider adding 12 factors described in the six following groups: (1) space for the activities of the young; (2) develop and renovate space for sightseeing and exploration activities; (3) develop and provide space and infrastructure for commuting, physical, recreational activities; (4) develop a service system of securing, warning, and protecting visitors against dangers; (5) develop and highlight the roles of Ideology/Philosophy in the society to build attractiveness; (6) develop and recover types of folk games, folk arts, and centers for cultural and folk art exchanges.

In terms of limitation, in the case study of Ho Chi Minh City, this research has not yet examined the difference between demographics and perceptions on urban attractiveness factors. Furthermore, this research has not clarified the evaluation of those experiencing urban attractiveness factors. Future studies will focus on discovering people’s perception of urban attractiveness factors.

For the conceptual categories of urban attractiveness factors, this research is limited to samples collected from four countries and four cities in two continents (Europe and Asia) and the coverage of samples is limited as well. However, this is a qualitative and data-mining study, therefore future research on case studies like Ho Chi Minh City is essential to verify and expand factors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express the sincere gratitude for Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology and Education (HCMUTE), Vietnam for partial financial assistance - Article Processing Charge (APC) through the project No. T2022-142. The authors would like to thank all of the help from professors and students at Hasselt University, Institute of Smart City and Management – University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Ton Duc Thang University, Hochiminh University of Technology and Education, Handong Global University, Techonological University Mandalay, Thammasat University who supported the authors to this investigation. Sincerest appreciation to people hosting the workshop – Global strategies for Local Tourism International Design Week including Dr. Tu Anh Trinh, Prof. Peggy Winkels, Prof. Els Hannes, Prof. Le-Minh Ngo, Prof. Oswald Devisch, Prof. Bie Plevoets, Prof. Ducksu Seo, Prof. Pawinee Iamtrakul.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alexander, C. 1977. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York, NY, United States: Oxford university press.

- Alhazzani, M., F. Alhasoun, Z. Alawwad, and M. C. González. 2021. “Urban Attractors: Discovering Patterns in Regions of Attraction in Cities.“ PLoS One 16: e0250204.

- Andreu, L., J. Enrique Bigne, and C. Cooper. 2000. “Projected and Perceived Image of Spain as a Tourist Destination for British Travellers.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 9 (4): 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v09n04_03.

- Ashworth, G., and S. J. Page. 2011. “Urban Tourism Research: Recent Progress and Current Paradoxes.” Tourism Management 32 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.02.002.

- Bansal, H., and H. A. Eiselt. 2004. “Exploratory Research of Tourist Motivations and Planning.” Tourism Management 25 (3): 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00135-3.

- Bernardo, F., and J. Manuel Palma-Oliveira. 2012. “Place Identity: A Central Concept in Understanding Intergroup Relationships in the Urban Context.” The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments 35–46. https://www.google.com.vn/books/edition/The_Role_of_Place_Identity_in_the_Percep/WM2e9gV9UxMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=A+central+concept+in+understanding+intergroup+relationships+in+the+urban+context.+role+place+identity+perception,+understanding&pg=PA35&printsec=frontcover.

- Boivin, M., and G. A. Tanguay. 2018. “How Urban Sustainable Development Can Improve Tourism Attractiveness.” Ara: Revista de Investigación En Turismo 8 (2): 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1344/ara.v8i2.27144.

- Boivin, M., and G. A. Tanguay. 2019. “Analysis of the Determinants of Urban Tourism Attractiveness: The Case of Québec City and Bordeaux.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 11:67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.11.002.

- Borges, A. P., C. Cunha, and J. Lopes. 2021. “The Main Factors That Determine the Intention to Revisit a Music Festival.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 13 (3): 314–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2020.1817051.

- Borio, C. 2020. “The COVID-19 Economic Crisis: Dangerously Unique.” Business Economics 55 (4): 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-020-00184-2.

- Botha, C., J. L. Crompton, and S.-S. Kim. 1999. “Developing a Revised Competitive Position for Sun/Lost City, South Africa.” Journal of Travel Research 37 (4): 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903700404.

- Bozic, S., J. Kennell, M. D. Vujicic, and T. Jovanovic. 2017. “Urban Tourist Motivations: Why Visit Ljubljana?” International Journal of Tourism Cities 3 (4): 382–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-03-2017-0012.

- Brida, J. G., M. Meleddu, and M. Pulina. 2012. “Understanding Urban Tourism Attractiveness: The Case of the Archaeological Ötzi Museum in Bolzano.” Journal of Travel Research 51 (6): 730–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512437858.

- Campa, J. L., F. Pagliara, M. Eugenia López-Lambas, R. Arce, and B. Guirao. 2019. “Impact of High-Speed Rail on Cultural Tourism Development: The Experience of the Spanish Museums and Monuments.” Sustainability 11 (20): 5845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205845.

- Chan, C.-S., S. Kan Yuen, X. Duan, and L. M. Marafa. 2018. “An Analysis of Push–Pull Motivations of Visitors to Country Parks in Hong Kong.” World Leisure Journal 60 (3): 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2018.1496527.

- Cohen-Hattab, K., and Y. Katz. 2001. “The Attraction of Palestine: Tourism in the Years 1850–1948.” Journal of Historical Geography 27 (2): 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhge.2001.0296.

- Crompton, J. L. 1979. “Motivations for Pleasure Vacation.” Annals of Tourism Research 6 (4): 408–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5.

- Crouch, G. I. 2011. “Destination Competitiveness: An Analysis of Determinant Attributes.” Journal of Travel Research 50 (1): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362776.

- Dann, G. M. S. 1981. “Tourist Motivation an Appraisal.” Annals of Tourism Research 8 (2): 187–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(81)90082-7.

- Enright, M. J., and J. Newton. 2004. “Tourism Destination Competitiveness: A Quantitative Approach.” Tourism Management 25 (6): 777–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.06.008.

- Fox, S. 2009. “Vacation or Staycation.” The Neumann Business Review 1–7. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=8813cd72703ab190395cae6a6a8596b329d197b4.

- Fraiz, J. A., P. de Carlos, and N. Araújo. 2020. “Disclosing Homogeneity within Heterogeneity: A Segmentation of Spanish Active Tourism Based on Motivational Pull Factors.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 30:100294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100294.

- García-Hernández, M., M. De la Calle-Vaquero, and C. Yubero. 2017. “Cultural Heritage and Urban Tourism: Historic City Centres Under Pressure.” Sustainability 9 (8): 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081346.

- Gnoth, J. 1997. “Tourism Motivation and Expectation Formation.” Annals of Tourism Research 24 (2): 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80002-3.

- Hennink, M. M. 2013. Focus Group Discussions. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199856169.003.0001.

- Hossain, M. M., S. Tasnim, A. Sultana, F. Faizah, H. Mazumder, L. Zou, E. L. J. McKyer, H. Uddin Ahmed, and P. Ma. 2020. “Epidemiology of Mental Health Problems in COVID-19: A Review.” F1000research 9. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.24457.1.

- Hurst, J. L., and L. S. Niehm. 2012. “Tourism Shopping in Rural Markets: A Case Study in Rural Iowa.” International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 6 (3): 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181211246357.

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. 1986. “Inner-City Tourism: Resources, Tourists and Promoters.” Annals of Tourism Research 13 (1): 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(86)90058-7.

- Jeuring, J. H. G., and T. Haartsen. 2017. “The Challenge of Proximity: The (Un)attractiveness of Near-Home Tourism Destinations.” Tourism Geographies 19 (1): 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1175024.

- Kaplan, R. 1985. “The Analysis of Perception via Preference: A Strategy for Studying How the Environment is Experienced.” Landscape Planning 12 (2): 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3924(85)90058-9.

- Kim, A. M. 2015. Sidewalk City: Remapping Public Space in Ho Chi Minh City. University of Chicago Press.

- Koga, T., A. Taka, J. Munakata, T. Kojima, K. Hirate, and M. Yasuoka. 1999. “Participatory Research of Townscape, Using” Caption Evaluation Method“-Studies of the Cognition and the Evaluation of Townscape, Part 1.” JOURNAL of ARCHITECTURE PLANNING and ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING 64 (517): 79–84. https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.64.79_2.

- Kumar, A., and K. Rajasekharan Nayar. 2021. “COVID 19 and Its Mental Health Consequences.“ Journal of Mental Health 30 (1): 1–2.

- Lim, S., and E. Giouvris. 2020. “Tourist Arrivals in Korea: Hallyu as a Pull Factor.” Current Issues in Tourism 23 (1): 99–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1372391.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Vol. 11. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Mariani, M., and B. Okumus. 2022. “Features, Drivers, and Outcomes of Food Tourism.” British Food Journal 124 (2): 401–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2022-022.

- Meng, F., Y. Tepanon, and M. Uysal. 2008. “Measuring Tourist Satisfaction by Attribute and Motivation: The Case of a Nature-Based Resort.” Journal of Vacation Marketing 14 (1): 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766707084218.

- Merwe, P. V. D., E. Slabbert, and M. Saayman. 2011. “Travel Motivations of Tourists to Selected Marine Destinations.” International Journal of Tourism Research 13 (5): 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.820.

- Mikulić, J., D. Krešić, D. Prebežac, K. Miličević, and M. Šerić. 2016. “Identifying Drivers of Destination Attractiveness in a Competitive Environment: A Comparison of Approaches.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 5 (2): 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.003.

- Miller, D., B. Merrilees, and A. Coghlan. 2015. “Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding and Developing Visitor Pro-Environmental Behaviours.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23 (1): 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.912219.

- Muritala, B. A., A.-B. Hernández-Lara, and M.-V. Sánchez-Rebull. 2022. “COVID-19 Staycations and the Implications for Leisure Travel.” Heliyon 8 (10): e10867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10867.

- Naderifar, M., H. Goli, and F. Ghaljaie. 2017. “Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research.” Strides in Development of Medical Education 14 (3): 3. https://doi.org/10.5812/sdme.67670.

- Nasar, J. L. 1994. “Urban Design Aesthetics: The Evaluative Qualities of Building Exteriors.” Environment and Behavior 26 (3): 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659402600305.

- Neto, O. A., S. Jeong, J. Munakata, Y. Yoshida, T. Ogawa, and S. Yamamura. 2016. “Physical Element Effects in Public Space Attendance.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 15 (3): 479–485. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.15.479.

- Nguyen, N. H. 2015. Understanding the Generative Process in Traditional Urbanism: An Application Using Pattern and Form Languages. Phoenix, Arizona, USA: Arizona State University.

- Pachucki, M. C., E. J. Ozer, A. Barrat, and C. Cattuto. 2015. “Mental Health and Social Networks in Early Adolescence: A Dynamic Study of Objectively-Measured Social Interaction Behaviors.” Social Science & Medicine 125: 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.015.

- Pawłowska-Legwand, A., and Ł. Matoga. 2016. “Staycation as a Way of Spending Free Time by City Dwellers: Examples of Tourism Products Created by Local Action Groups in Lesser Poland Voivodeship in Response to a New Trend in Tourism.” World Scientific News 51: 4–12. https://www.worldscientificnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/WSN-51-2016-4-12.pdf.

- Pham, P. C. 2018. “Giá Trị Kiến Trúc Đô Thị Đặc Trưng Của Khu Vực Trung Tâm Lịch Sử Sài Gòn - Tp Hồ Chí Minh.” Tạp Chí Kiến Trúc (1). https://www.tapchikientruc.com.vn/chuyen-muc/gia-tri-kien-truc-thi-dac-trung-cua-khu-vuc-trung-tam-lich-su-sai-gon-tp-ho-chi-minh.html

- Pham, P. C. 2019. “Tính Đa Dạng Văn Hoá và Diện Mạo Kiến Trúc Đô Thị Sài Gòn-Tp Hồ Chí Minh.” Tạp Chí Kiến Trúc (10). https://www.tapchikientruc.com.vn/chuyen-muc/tinh-da-dang-van-hoa-va-dien-mao-kien-truc-do-thi-sai-gon-tp-hcm.html

- Prayag, G., and S. Hosany. 2014. “When Middle East Meets West: Understanding the Motives and Perceptions of Young Tourists from United Arab Emirates.” Tourism Management 40: 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.05.003.

- Rigall-I-Torrent, R. 2008. “Sustainable Development in Tourism Municipalities: The Role of Public Goods.” Tourism Management 29 (5): 883–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.004.

- Romão, J., and Y. Bi. 2021. “Determinants of Collective Transport Mode Choice and Its Impacts on Trip Satisfaction in Urban Tourism.” Journal of Transport Geography 94: 103094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103094.

- Romão, J., K. Kourtit, B. Neuts, and P. Nijkamp. 2018. “The Smart City as a Common Place for Tourists and Residents: A Structural Analysis of the Determinants of Urban Attractiveness.” Cities 78: 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.11.007.

- Romão, J., B. Neuts, P. Nijkamp, and E. Van Leeuwen. 2015. “Culture, Product Differentiation and Market Segmentation: A Structural Analysis of the Motivation and Satisfaction of Tourists in Amsterdam.” Tourism Economics 21 (3): 455–474. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2015.0483.

- Salingaros, N. A. 2000. “The Structure of Pattern Languages.” ARQ: Architectural Research Quarterly 4 (2): 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1359135500002591.

- Sanui, J., and M. Inui. 1986. “Extraction of Residential Environment Evaluation Structures Using Repertory Grid Development Technique–A Study on Residential Environment Evaluation Based on Cognitive Psychology–.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, (367): 15–22.

- Servillo, L., R. Atkinson, and A. Paolo Russo. 2012. “Territorial Attractiveness in EU Urban and Spatial Policy: A Critical Review and Future Research Agenda.” European Urban and Regional Studies 19 (4): 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411430289.

- Sirkis, G., O. Regalado-Pezúa, O. Carvache-Franco, and W. Carvache-Franco. 2022. “The Determining Factors of Attractiveness in Urban Tourism: A Study in Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Bogota, and Lima.” Sustainability 14 (11): 6900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116900.

- Steptoe, A., and G. Di Gessa. 2021. “Mental Health and Social Interactions of Older People with Physical Disabilities in England During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Cohort Study.” The Lancet Public Health 6 (6): e365–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00069-4.

- Sugiyama, T., E. Leslie, B. Giles-Corti, and N. Owen. 2008. “Associations of Neighbourhood Greenness with Physical and Mental Health: Do Walking, Social Coherence and Local Social Interaction Explain the Relationships?” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 62 (5): e9–e9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.064287.

- Talevi, D., V. Socci, M. Carai, G. Carnaghi, S. Faleri, E. Trebbi, A. di Bernardo, F. Capelli, and F. Pacitti. 2020. “Mental Health Outcomes of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Rivista Di Psichiatria 55 (3): 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1708/3382.33569.

- Tam, B. 2022. “Đánh Thức Bản Sắc Đô Thị Sông Nước Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh.” Báo Xây Dựng. https://baoxaydung.com.vn/danh-thuc-ban-sac-do-thi-song-nuoc-thanh-pho-ho-chi-minh-331211.html.

- Uysal, M., and C. Jurowski. 1994. “Testing the Push and Pull Factors.” Annals of Tourism Research 21 (4): 844–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90091-4.

- Wang, L., B. Fang, and R. Law. 2018. “Effect of Air Quality in the Place of Origin on Outbound Tourism Demand: Disposable Income as a Moderator.” Tourism Management 68: 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.007.

- Wong, I. A., Z. Lin, and I. Esther Kou. 2023. “Restoring Hope and Optimism Through Staycation Programs: An Application of Psychological Capital Theory.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 31 (1): 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1970172.

- Wu, M.-Y., and G. Wall. 2017. “Visiting Heritage Museums with Children: Chinese Parents’ Motivations.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 12 (1): 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2016.1201085.

- Xinhua, G., L. Sheng, and C. Lei. 2022. “Specialization or Diversification: A Theoretical Analysis for Tourist Cities.” Cities 122: 103517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103517.

- Zehrer, A., and K. Hallmann. 2015. “A Stakeholder Perspective on Policy Indicators of Destination Competitiveness.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 4 (2): 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.03.003.

- Zhang, Y., and Y. Peng. 2014. “Understanding Travel Motivations of Chinese Tourists Visiting Cairns, Australia.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management 21: 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2014.07.001.