ABSTRACT

Although economic nationalist governments in East Central Europe (ECE) have strongly challenged FDI-dependence, FDI-led growth has remained stable across the region. The political economy literature explains this puzzle with enduring business-state elite interactions and the disciplining role of the EU. Instead, we show that the EU’s regional investment aid rules, which provide central governments in relatively backward member states with considerable policy space, serve as the main policy tool for reinforcing FDI-dependence. Using a unique dataset on regional investment aid granted between 2004 and 2022 in the Visegrád countries (V4), we show that each government, regardless of its ideological background, granted the vast majority of this type of aid to foreign firms. In addition, contrary to their political rhetoric, economic nationalist governments in Hungary and Poland outperformed their non-nationalist counterparts in granting aid to foreign firms. This suggests an instrumental use of this transnationally rooted policy opportunity: as their European political isolation grew, economic nationalists increasingly resorted to the promotion of foreign firms because the continued inflow of foreign capital has a legitimising effect both at home and abroad.

Introduction

The EU’s ability to accommodate different types of capitalist systems is a recurring question in political economy scholarship (Johnston & Regan, Citation2018). At stake in the debate is whether the EU is able to manage its own heterogeneity, including its East–West divide, and provide sustainable catch-up opportunities for less developed members, or whether it fails in this task, which would also undermine its long-term viability. Scholarly accounts of this topic are either more positive (Bruszt & Langbein, Citation2020) or less optimistic (Höpner & Schäfer, Citation2015). Recent political and economic developments seem to support the pessimistic views. After the great financial crisis of 2008, secular stagnation has characterised the advanced market economies (Baccaro et al., Citation2022) and in this context, political divergence and a persistent development gap burdened relations between the core and peripheral EU members.

Despite generally good economic performance, economic catching-up in East Central Europe (ECE) has been rather limited: average GDP per capita in ECE is still less than half that of the older member states, suggesting only minimal convergence to Western standards (Epstein, Citation2020; Volintiru et al., Citation2021). ECE countries face limited innovation and upgrading potential and their competitive advantage in low-wage segments may threaten with a middle-income trap (Győrffy, Citation2022; Myant, Citation2018). High dependence on foreign capital and exports also raises their vulnerability to external shocks (Vukov, Citation2021). These weaknesses led some researchers to conclude that the dependent model had reached its limits (Galgóczi & Drahokoupil, Citation2017).

After the 2008 crisis, the politicisation of the East–West development divide (Volintiru et al., Citation2021) and the subsequent rise of economic nationalism in several ECE countries questioned the foreign capital-based dependent market economies in ECE (Bluhm & Varga, Citation2020; Toplišek, Citation2020). Democratic backsliding, particularly in Hungary and Poland, has challenged the EU’s core democratic values (Börzel & Langbein, Citation2019), which can be seen as a symptom of a global phenomenon of rising populism and a backlash against neoliberalism (Crouch, Citation2019). Economic nationalists regularly criticised the influence of foreign investors on central governments (Epstein, Citation2020), condemned neoliberal economic policies as the main reason for creating a heavy dependence on low value-added manufacturing FDI, and urged greater domestic ownership of the economy (Naczyk, Citation2022).

Putting the anti-FDI rhetoric into practice, Hungarian and Polish economic nationalists initiated a nationalisation project in the banking sector to increase domestic ownership of banking assets and reduce external control over public finances (Johnson & Barnes, Citation2015). This was accompanied by reforms in banking supervision and regulation to promote national interests (Mérő & Piroska, Citation2016). While some scholars portray these changes as the implementation of a ‘grand strategy’ to break with neoliberal practices and regain control over domestic finances (Sebők & Simons, Citation2022), others attribute to them less noble motives of rent-seeking, serving political rather than developmental goals (Ádám, Citation2019; Oellerich, Citation2022).

However, despite the rise of anti-foreign political rhetoric and the politicisation of dependency, the basic pillars of FDI-led models have not changed. ECE capitalism still relies on external capital, even in countries led by the most overt economic nationalists (Ban & Adascalitei, Citation2022; Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2019). Empirical data on the contribution of foreign firms to exports and economic growth also suggest continuity of FDI-led growth, as reliance on foreign investment remained similar across the region even after the 2008 crisis (Johnston & Matthijs, Citation2022). It follows that, contrary to their political rhetoric, nationalist governments have not broken with FDI-friendly practices, but have instead built a national variant of neoliberalism, with extended state control over domestic finance and some services, leaving the competitive, foreign-owned sectors untouched (Ban et al., Citation2023).

The stability of FDI-dependent market economies is puzzling, given the contestation they face. The political economy literature has yet to provide a convincing explanation for this phenomenon. Some authors argue that the mutually beneficial ties established between foreign manufacturing investors and the domestic political elite strengthen dependent growth in ECE (Bohle & Regan, Citation2021) but this conclusion is based on limited empirical data derived from the observation of a single country, Hungary. Others overestimate the EU’s disciplining regulatory influence on ECE countries, which may reinforce those policies that serve the interests of FDI (Vukov, Citation2020).

In this paper, we argue that one of the most important instruments serving systemic stability is indeed transnationally rooted: EU rules on regional investment aid provide ECE governments with ample policy space to promote foreign investors. However, central governments’ reliance on regional investment aid is instrumental rather than driven by informal ties with foreign firms. On the one hand, foreign capital being the main source of economic growth poses a structural constraint on these states. On the other hand, foreign investments play a legitimising role, an aspect that becomes more important for economic nationalists tending towards authoritarianism. Promoting FDI is thus part of their ‘autocratic hedging’ strategy, which involves foreign investors as ‘external rebalancers’ to legitimise these governments and increase their external and domestic approval (Camba & Epstein, Citation2023).

Focusing on the Visegrád countries (Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, hereafter V4), this paper examines the foundations of FDI-dependent capitalisms by comparing the regional investment aid practices of all V4 governments in power since 2004. V4 growth models are very similar in that they all rely on FDI-dependent, export-oriented growth, which has remained stable despite some recalibration (Vukov, Citation2023). However, while economic nationalist governments have been in power in Hungary (since 2010) and Poland (2015–2023), subsequent Czech and Slovak governments have not shared this disposition. After 2004, anti-liberal ideologies were either absent or substantially contained in both Czechia and Slovakia (Scheiring, Citation2021), hence neoliberalism proved resilient (Šitera, Citation2021). Although populist leaders such as Andrij Babiš in Czechia and Robert Fico in Slovakia were elected in both countries, they did not challenge the FDI-led economic model. Thus, the similarity of structural economic factors in the V4 and the divergence in the political ideologies of the central governments provide an ideal context for a comparative analysis.

Hungary and Poland are therefore the most likely cases where regional aid policies would favour domestic over foreign firms. Contrary to this expectation, our empirical observations reveal that the V4 governments, irrespective of their ideological background, have uniformly promoted foreign investors through regional investment aid. They have used this transnationally rooted regulatory opportunity to support export-oriented, foreign manufacturing firms, thereby reinforcing FDI-dependence and the semi-peripheral position of these economies.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section presents the theoretical background and discusses the limitations of current explanations of the stability of FDI-led growth models in ECE. The subsequent section outlines our argument, followed by an empirical analysis of the beneficiaries of regional investment aid in the V4 and the conclusion.

Explaining the stability of FDI-led growth regimes: the limitations of the literature

Exploring the factors that stabilise economic systems has long been a central question in both comparative and international political economy (CPE and IPE, respectively). Researchers in both fields have mostly focused on advanced capitalist countries, and only recently has attention shifted to the semi-periphery. Within CPE, the varieties of capitalism (VoC) stream attributes stability to the institutional architecture of capitalist systems, while the theory of business power sees the interactions between corporate and state elites as the foundation of systemic stability. In IPE, countries’ position in the global market and various transnational forces such as multinational corporations and international organisations interacting with domestic actors can contribute to the stability (or change) of national economic systems. However, each approach has its limitations, especially when applied to the semi-peripheral ECE context.

The VoC framework is based on the argument that the strong institutional complementarities and specific competitive advantages that characterise the two ideal types, liberal and coordinated market economies, stabilise economic systems (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001). However, VoC places too much emphasis on structural circumstances and downplays domestic agency, particularly the role of the state, in shaping capitalist varieties (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2009). Thus, VoC’s static approach fails to address why capitalist varieties could remain stable if they face economic shocks.

In contrast, the business power literature argues that in the realm of ‘quiet politics’, informal and mutually beneficial ties between dominant firms and political elites drive systemic stability (Culpepper, Citation2010). The recent innovation in the CPE literature, the growth model perspective, outlines a similar argument by identifying social blocs as the supporting element of a growth model, which are cross-class and cross-sector coalitions of dominant economic actors (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2019). However, the rise of populism and the backlash against neoliberalism after the 2008 global financial crisis extended the sphere of ‘noisy politics’ and undermined the traditional channels through which businesses used to exert influence on political elites in advanced economies (Feldmann & Morgan, Citation2022). Traditional social blocs and business power have therefore weakened and their stabilising function have also decreased.

In contrast to CPE, IPE attributes a significant role to transnational influences in shaping capitalist systems. This literature is particularly developed in the EU context because, as the most advanced transnational regulatory integration in the world, the EU profoundly affects each member state, be it a core or a semi-peripheral economy. Before the 2008 crisis, the institutional architecture of the EU allowed several capitalist varieties to flourish, but since then, the hardening rules of European monetary integration and the increasing fiscal pressure on central governments have put a straitjacket on consumption-led economies but promoted export-led models (Brazys & Regan, Citation2017). From this perspective, the EU has simultaneously contributed to the stability of export-led growth models in the European core while weakening consumption-led systems, especially in Southern Europe (Johnston & Regan, Citation2016). This argument assumes only a limited role for domestic agency, moreover, the constraints imposed by the eurozone do not fully apply to those EU members that have stayed out of European monetary integration, such as the V4, except Slovakia.

The above approaches have been adapted to semi-peripheral contexts, but their limitations in explaining systemic stability have remained. Nölke and Vliegenthart (Citation2009) extended the VoC framework to the V4 and argued that these economies have developed into dependent market economies where the export performance of foreign-owned manufacturing sectors has become the main contributor to economic growth. Export-driven growth rests on the functional specialisation in the low value-added segments of complex manufacturing, where primarily German (and recently, several East Asian) multinational manufacturing firms have invested.

Although Nölke and Vliegenthart (Citation2009) do not discuss the role of politics and domestic political agency in the birth of DMEs, other political economists have convincingly shown that the ‘hyper-integration’ of these economies (Šćepanović, Citation2013) into the European and global markets through foreign investment was the result of a deliberate domestic political strategy (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012) actively supported by the EU (Medve-Bálint, Citation2014). Central governments facilitated the emergence of the FDI-led growth regimes by introducing generous investment support schemes to promote foreign firms (Drahokoupil, Citation2009; Tőrös et al., Citation2017). As central governments tried to attract the same multinationals, they often aimed to outbid competing offers by promising more generous incentives. Investment competition put a considerable strain on national budgets, but secured a growing number of foreign investments. State aid therefore constituted one of the backbones of the FDI-led model, and became the main instrument for central governments to influence the location decisions of foreign investors. From the theoretical lens of DME, however, state aid remains an apolitical, technocratic building block of dependent market economies, an approach of little analytical value when it comes to exploring the reasons for its persistence or change.

In contrast, IPE scholarship has placed state aid practices in ECE in a transnational regulatory context, thereby taking an important but still incomplete step in explaining the resilience of FDI-led growth models. This scholarship argues that ECE has mastered EU state aid rules and that its generosity in state aid is accompanied by an exceptionally high level of compliance with European rules. Vukov (Citation2020) explains compliance with the presence of highly Europeanised domestic institutions specialised in the provision of state aid. She concludes that the enduring commitment to state aid in ECE (and especially in the V4) ensures the persistence of the FDI-led model. While Vukov’s argument recognises state aid policy as the key domain serving the dependent market economy, she overestimates the influence of transnational (EU-level) capacity building in a single policy domain in a region where, in the post-2008 period, right-wing populist and economic nationalist governments have regularly sought to undermine even the most basic EU principles. Without examining the beneficiaries, the author also implicitly assumes that state aid is routinely granted to foreign companies. But even if an economic nationalist government remains committed to the provision of state aid, it can use it to support domestic rather than foreign firms. The continued provision of EU-compliant state aid alone therefore does not explain the stability of FDI-led growth models.

Adapted to the ECE context, the business power literature offers a more dynamic but still limited explanation for the persistence of FDI-led economies. The promotion of foreign firms has created ties between ECE central governments and foreign investors that resemble the dependent development model observed by Peter Evans (Citation1979) in Brazil in the 1970s. However, an important difference is that the triple alliance between domestic capital, foreign investors and the central state, which created a dominant social bloc in Brazil, has mostly been reduced to two players in ECE: foreign capital and the state, without any significant involvement of domestic capital. Taking the case of Hungary, Bohle and Regan (Citation2021) argue that bargains between leading foreign manufacturing investors (mainly German multinationals) and the political elite reinforce the continuity of the FDI-led model. The economic nationalist Hungarian government has excluded non-manufacturing foreign firms from this deal and extended it to some carefully selected domestic capital owners (Scheiring, Citation2020).

Although business-state elite interactions may indeed play a central role in shaping dependent market economies, even the above Hungarian example reveals that those bargains are too vulnerable to serve as a strong pillar of continued FDI-led growth. On the one hand, the Orbán government gradually excluded foreign-owned banks, telecommunication and energy companies from the social bloc, which increased investment risks also in other sectors. On the other hand, such strong ties between the domestic political elite and the German investors as in Hungary could not develop in Poland because of the openly Germanophobic narrative of the Law and Justice (PiS) government (Riedel, Citation2020), which, among others, manifested in the formal submission of WWII reparation claims to Germany (Kołodko, Citation2023).

In sum, three main arguments have been formulated about the stability of the FDI-led and export-oriented dependent economies in ECE. The first relates to the EU’s monetary and economic governance rules, which favour export-oriented models. However, with the exception of Slovakia, none of the V4 countries has joined the eurozone, so its strict monetary and fiscal rules do not apply in their case. Moreover, this view downplays domestic political agency. The second approach recognises that the promotion of investors through a transnationally anchored, Europeanised state aid policy is the backbone of sustained foreign capital inflows. However, it only provides empirical evidence on the high compliance of ECE countries with European state aid rules and does not empirically test whether compliance indeed serves FDI dependence. The third argument focuses on business-state elite interactions, claiming that mutually beneficial ties between foreign investors and the political elite ensure the continuity of FDI-led development in ECE, despite rising economic nationalism and an anti-FDI narrative. Although this argument is the most actor-centred and dynamic, it is empirically based on a single country study (Hungary), which may not be transferable to other contexts.

Explaining the stability of FDI-led economies in ECE therefore needs a more refined theoretical framing and a more substantive empirical support. In this paper, we combine the EU’s transnational regulatory influence in state aid with the domestic political elite’s determination to use aid in favour of foreign investors. We argue that a specific part of European state aid rules, the regional investment aid serves as the primary tool to attract foreign investors to ECE. European regional aid rules are more favourable to less developed member states and regions (as in the case of ECE) because higher regional aid ceilings apply in these areas. Regional aid rules thus provide ECE governments with a broad and flexible mandate, and they take advantage of this opportunity by justifying aid to foreign investors on the grounds that the investment projects contribute to regional development. This leads to an instrumental use of state aid by ECE governments, rather than following any normative considerations: ensuring the flow of foreign capital contributes to economic growth, which governments strive to secure for their self-interest. This is in line with the creative compliance argument developed by Lindstrom (Citation2021), who shows that ECE governments, in particular Hungary, use their administrative capacity to formally adhere to EU state aid rules but substantively challenge their original objectives. Furthermore, in the case of the economic nationalist Hungarian and Polish governments, their commitment to supporting foreign companies may have contributed to their external approval and legitimacy as part of their hedging strategy (Camba & Epstein, Citation2023).

European regional aid rules and how they serve FDI-led growth models in ECE

Free and undistorted market is the founding principle of the EU, which implies that any measure that interferes into market competition may violate this basic principle. However, state aid may be necessary to achieve certain objectives that the free market fails to deliver. Therefore, instead of completely banning all state aid measures, the EU Treaties allow for the provision of aid. As Article 107(3) TFEU specifies, aid may be compatible with the EU’s internal market if it is granted to promote the development of backward areas or certain economic activities or facilitates the completion of an important project of common European interest. The Commission distinguishes sectoral aid from horizontal aid. The former is explicitly discouraged, but horizontal aid promoting objectives in line with the EU’s broad socio-economic agenda is encouraged. Regional aid belongs to the category of horizontal aid (Schito, Citation2022).

Through regulating subsidies by public authorities, EU-level state aid control is meant to prevent aid competition between member states (Cini, Citation2001). In the past, member states had to notify the Commission before granting any type of aid. To ease the growing burden of notified aid on the Commission, in 1998, a Council regulation allowed the creation of block exemptions, which released entire categories of aid from the notification requirement. While sectoral aid has mostly been ruled out, horizontal aid for SMEs, training, research and innovation, regional development, and employment have been included in the block exemptions. In 2008, the Commission adopted the General Block Exemptions Regulations (GBER) that created a unified framework (Heimler & Jenny, Citation2012) and the scope of exemptions from prior notifications have been extended since then.

The regulation on regional investment aid stipulates that if a region’s GDP per capita is below the EU average, then higher regional aid intensities apply for investment projects that are expected to enhance regional development. The regional aid maps, which set maximum aid levels, allow for generous investment support in ECE because nearly the whole area classifies as backward. In 2007–2013, the regional aid intensity set by the Commission was in the vast majority of ECE regions either 40 or 50 per cent, meaning that this proportion of the eligible investment value was possible to grant as aid to the prospective investor. The current regional aid maps (2022–2027)Footnote1 still allow for 30–40 per cent regional aid intensity in most of the ECE regions.

In essence, the regional aid ceilings are regulatory imprints of the East–West development divide and they offer an opportunity for ECE governments to grant generous state aid to investors by referring to the investments’ anticipated contribution to regional development. Capitalising on this transnational framework, ECE governments tended to justify state aid granted to foreign investors by referring to their contribution to regional development (Szent-Iványi, Citation2017), and launched aid schemes complying with the regional investment aid regulations.Footnote2

After assessing whether regions are converging towards or diverging from the European average, the Commission regularly updates the regional aid maps. Following one of these assessments, the Commission recognised that the GDP per capita of most Czech regions was approaching the EU average and reduced the regional aid intensity from 40% (in 2007–2013) to 25% for all Czech regions for the period 2014–2017. Bohuslav Sobotka, Czech Prime Minister at the time, sharply criticised the European Commission for lowering the regional aid threshold in Czechia while leaving the high aid ceilings almost untouched in the other ECE countries.Footnote3 He argued that the Commission’s move had put Czechia at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis its regional rivals.

Sobotka’s reaction illustrates that V4 central governments see EU regional aid rules as a means to attract foreign investors, while the policy’s original objective of stimulating economic growth in the least developed regions remains secondary. Paradoxically, if the V4 governments want to maintain generous regional aid to foreign investors, then it is not in their interest to catch up with the core, as the Commission would immediately lower their regional aid ceilings. Low aid ceilings would signal a narrowing of the East–West development gap, but would also mean a significant loss of state aid policy space for V4 governments.

Regional aid is thus one of the main channels through which V4 governments can support foreign investments. The commitment to provide aid may be motivated by several political and economic considerations. First, the functional specialisation of the V4 in low value-added manufacturing reflects the competitive advantages of these semi-peripheral economies and represents an important structural constraint on domestic economic policy. Turning against the foreign investors at the heart of this model would entail a dramatic loss of export performance, a decline in industrial employment, a loss of confidence in international capital markets and a negative prospect for growth. In addition, foreign firms account for a large share of total output, value added and employment in the V4, as well as a high share of value added in exports (see Table A1 and Figure A1 and A2 in the Online Supplement). Consequently, any government measures weakening export-oriented foreign firms would jeopardise the economic fundamentals of these countries.

Furthermore, the provision of regional aid to foreign investors may have a legitimising effect, which may become more important for economic nationalist governments that also tend towards authoritarianism. Drawing on Fritz Scharpf’s (Citation1970) distinction between input and output legitimacy, central governments need to maintain popular support both by demonstrating to the electorate that their decisions reflect the will of the people (input) and by delivering policy outcomes that serve the interests of the people (output). In the case of a dominant economic nationalist narrative, central governments can gain input legitimacy among their electorate through an anti-liberal rhetoric of economic nationalism (Coman & Volintiru, Citation2023). At the same time, maintaining the FDI-led model provides them with external approval and contributes to domestic output legitimacy, as the inflow of foreign capital has a legitimation effect abroad and a potential legitimation effect domestically through its contribution to jobs and economic growth. Once the growth engine stutters, these rulers find it much harder to win the support of their populations and are likely to resort to increasing coercion (e.g., Gerschewski, Citation2013). It is therefore no coincidence that both the nationalist Hungarian and Polish governments have regularly boasted about their achievements in attracting FDI and used it as a signal of broader economic success, which is part of their hedging strategy (Camba & Epstein, Citation2023).

Regional investment aid in the V4

We collected data on regional investment aid awarded between 2004 and 2022 in the V4 countries through individual government decisions. These are large, non-competitive grants, decided on a one-on-one basis following intensive and confidential negotiations with the prospective investors. The beneficiaries therefore clearly reveal the investment preferences of the governments and are suitable to identify whether regional aid practices favour domestic or foreign investors.

We relied on official publications of ministries, investment promotion agencies and the national competition authoritiesFootnote4 and identified 1729 cases of regional investment aid over the whole period (Czechia: 870 grants, Hungary: 408, Poland: 200, Slovakia: 251). The reason for the relatively high number of beneficiaries in Czechia is that until recently the Czech government was the most active in granting aid to investors (Vukov, Citation2020). Conversely, the low number of Polish awards may seem surprising, but this can be explained by the country’s unique incentive system. In the 1990s, to stimulate regional economic development, Poland established Special Economic Zones (SEZs) where investors were granted exemptions from corporate or personal income tax (Domański, Citation2005). In 2018, the economic nationalist PiS government consolidated the SEZs and expanded their territories, effectively making the country a single zone, which served the interests of foreign companies (Toplišek, Citation2020). The managers of the SEZs decide autonomously on the granting of support without consulting a higher authority (Wróblewska, Citation2022). Thus, individual government decisions on regional investment aid are taken only if, in addition to the tax relief, the investor receives cash grants, too. Our dataset only includes enterprises that received cash grants from the Polish government as regional investment aid, which is a much smaller number than all enterprises that ever received tax exemptions in SEZs.

Because of the above differences in reporting practices, the regional aid data are not strictly comparable across countries but are entirely comparable across governments within each country, thus the dataset allows for investigating variation in regional aid practices along different electoral cycles. We complemented the official data with company information obtained from EMIS, a commercial dataset specialising in emerging markets. We matched the grant recipients with corresponding data on ownership (country of origin of the ultimate owner). In this way, we could distinguish between domestic and foreign-owned enterprises, and among foreign firms by the country of the ultimate owner. Finally, based on the date of decision of awarding the aid, we matched each recipient with the government that granted the support, using the ParlGov database. The final dataset thus contains the name of the beneficiaries, their economic sector, the country of origin of the investor, the year of aid decision, the aid amount calculated in constant 2010 euros, and the central government that awarded the regional investment aid.

We treated those governments as a single unit where the main coalition partners remained the same even if the prime minister changed. Similarly, if the main parties of the governing coalition stayed in power after a general election, we treated the two cabinets as a single government. For instance, we considered the government led by the Polish Civic Platform (PO) between 2007 and 2015 as a single government, although two prime ministers, Donald Tusk and Ewa Kopacz served in this period. We applied the same logic to the Hungarian coalition led by the socialist party between 2002 and 2010 and treated it as a single government although three different prime ministers served during the two parliamentary cycles. Also, we considered the caretaker Fischer government in Czechia together with the cabinets of prime ministers Topolanek and Necas, because Fischer’s government was supported by the same conservative party (ODS, Civic Democratic Party) that was the leading coalition partner in the other two formations. In the end, we identified 14 different V4 governments in the examined period.

Next, for each cabinet, we calculated the share of aid to foreign companies from the total regional aid awarded and the share of aid supporting German companies from the total regional aid granted to foreign firms. The former indicator reveals the proportion of aid going to foreign companies, while the latter indicator demonstrates the weight of German firms within the aid benefiting foreign enterprises. We emphasise the German link, because Germany is the largest European investor in the V4 and plays a leading role in embedding these countries in global value chains.

lists some of the main indicators we calculated based on the regional aid data. It shows that foreign firms were the main beneficiaries of regional investment aid, receiving more than 82% of total aid in Czechia and Hungary and more than 93% in Poland and Slovakia. Almost all the large multinationals that have invested in these countries have benefited from this support, confirming that regional investment aid has been an important industrial policy instrument to attract foreign firms thereby contributing to FDI dependence.Footnote5 Regional aid thus represents a peculiar case of ‘reverse’ economic patriotism (Clift & Woll, Citation2012): although it is open to domestic entrepreneurs, in practice it has mainly benefited foreign firms.

Table 1. Selected indicators of regional investment aid in the V4 in 2004–2022.

Following the Eurostat’s classification, we divided the beneficiaries to medium high-tech, high-tech, knowledge-intensive, and other firm types. Medium high-tech includes the automotive industry as it refers to the manufacture of chemicals, electrical and transport equipment. High-tech includes pharmaceuticals and the manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products, while knowledge-intensive covers a wide range of activities requiring highly qualified labour, such as software development, engineering, research and development, telecommunications, financial, insurance and information services.

The figures (see Table A2 in the Online Supplement) show that, with the exception of Poland, the sectoral profile of the aided investments was similar. In Poland, however, high-tech firms received the largest share of aid, partly due to the generous aid in 2006–2007 to a big cluster of South Korean electronic equipment manufacturing firms. The number of jobs created in the knowledge-intensive sector was also high, because the PO government in 2007–2015 preferred to grant regional aid to investors in business services. German firms received the highest share of support in Czechia and Hungary (33 and 31 per cent of total regional aid to foreign firms respectively) and South Korean companies in Poland and Slovakia (40 and 27 per cent, respectively). German companies, mostly involved in car manufacturing, were among the top three aid recipients in each country, further evidence that the German growth model is thriving on the back of the successful transnational reorganisation of its automotive industry, partly based on the concentration of production in ECE (Gerőcs & Pinkasz, Citation2019).

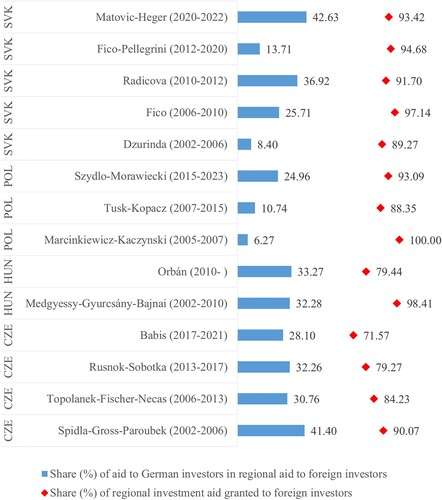

shows the share of regional aid granted to foreign investors and the share of German beneficiaries of the aid granted to foreign firms by each V4 government between 2004 and 2022. The main objective is to contextualise the aid practices of the economic nationalist governments in Hungary (the Fidesz government led by Orbán since 2010) and Poland (the PiS government led by Szydlo and her successor, Morawiecki, between 2015 and 2023), in order to determine whether they differ from other V4 governments that do not share their ideological dispositions.

Figure 1. Regional investment aid awarded in the V4 countries by the central governments (2004–2022). Note: parentheses indicate the period each government was in power. Source: authors’ own calculation based on individual regional aid data (see full list of sources in note no. 4) and the ParlGov database.

Although the share of regional investment aid granted to foreign companies under the Orbán government (79 per cent) was significantly lower than under the previous socialist-liberal coalition (98 per cent), the Orbán cabinet granted far more aid to foreign companies than the socialists (€51 million vs. €16 million per 100 days in office). The PiS government does not appear to be very different from its centre-right predecessor either, granting 93 per cent of individual regional aid to foreign companies, compared to 88 per cent under the PO cabinet. The difference in aid amounts to foreign beneficiaries is not notable either (€9.5 million versus €8.2 million per 100 days in office). However, if we take into account all regional aid distributed, which includes tax breaks in SEZs, the difference between the PO and the PiS governments becomes striking. According to the latest State Aid Scoreboard (2022), the Szydlo-Morawiecki (PiS) government spent an average of 0.29 per cent of GDP on regional investment aid in 2016–2021, compared to 0.21 per cent for the PO government in 2007–2015. In nominal terms, the difference is even greater: over the same period, the PiS government spent an average of €1529 million a year (in constant prices) on regional investment aid, compared with €829 million by the PO government. Not only did the Hungarian and Polish economic nationalists continue to promote foreign investors through regional state aid, but they also spent significantly more than previous governments.

Since the economic nationalists came to power, their commitment to attracting foreign capital has taken many forms, contrary to the official anti-FDI narrative. The PiS government’s economic policy was based on the ‘Strategy for Responsible Development’, which set out an economic roadmap for the country. Although the strategy emphasised the development of endogenous potential, it also relied on foreign investment in high value-added segments (Riedel, Citation2021). In Hungary, measures such as the lowering of the corporate tax rate to 9 per cent, the reduction of social security contributions and a new labour law that allowed for further flexibilisation of the labour market (Scheiring, Citation2020) have been important tools of the Orbán government to lure foreign investors. However, a key difference between the two countries is that, in line with the developmentalist stance of Polish post-communist governments (Naczyk, Citation2022), the PiS cabinet was explicitly trying to avoid the middle-income trap by securing high value-added foreign investment. In contrast, the Orbán government encouraged FDI in low value-added manufacturing activities.

The more the Hungarian and Polish governments’ conflict with the EU deepened and the more they became isolated in European politics, the more they intensified the granting of regional aid to foreign companies. Due to the continuous deterioration of the rule of law in both countries, the Article 7 procedure, which threatens to suspend voting rights in EU bodies, was initiated first against Poland in December 2017 and then against Hungary in September 2018. In March 2019, Fidesz was suspended from the European People’s Party (EPP) and two years later left the EPP. Besides their political isolation, the two governments also faced serious financial consequences: funds from the EU’s Cohesion Policy and the Recovery and Resilience Facility have been suspended. In parallel, the Hungarian and Polish governments have stepped up the provision of regional investment aid to foreign investors: in 2019–2022, in just four years, the Fidesz government spent €1480 million for this purpose, which is 52 per cent of all regional investment aid paid to foreign companies in Hungary since 2004. In the same period, the PiS government allocated 73 per cent of the regional aid it has granted since coming to power in 2015 to foreign companies, which is 25 per cent of Poland’s total spending since 2004. The coronavirus pandemic is not the reason for the increased spending in Hungary and Poland, as the regional aid schemes are separate from the Covid schemes. The Czech and Slovak cases confirm this: in 2019–2022, the Czech and Slovak governments granted €410 million and €150 million, respectively, in regional investment aid to foreign companies, which in both instances represents only 8 per cent of the regional investment aid granted to foreign firms since 2004.

Unlike the economic nationalists in Hungary and Poland, the Czech and Slovak governments have recently shifted their focus from regional aid to environmental and energy saving aid, bringing their aid profiles closer to the most frequently granted aid categories in the EU (Ambroziak, Citation2022). According to Eurostat data, in Czechia, compared to the previous Rusnok-Sobotka cabinet (2013–2017), which spent on average 0.46 per cent of GDP on regional aid, the Babis government (2017–2021) significantly reduced regional aid spending to 0.17 per cent of GDP. A smaller but similar trend can be observed in Slovakia, where the Matovic-Heger government (in power from 2020 to 2023) spent 0.12 per cent of GDP on regional aid annually, compared to 0.17 per cent during the Fico-Pellegrini cabinet (2012–2020).

Changes in FDI do not explain the increased regional aid to foreign investors in Hungary and Poland. Since 2012, FDI stock has barely increased in Hungary and Slovakia (which is also an indicator of heavily volatile FDI inflows), whereas by 2022 it has increased by 50 per cent in Czechia and 37 per cent in Poland (see Figure A3 in the Online Supplement). However, while the Fidesz government intensified the provision of regional aid to foreign investors, the Slovak governments facing similar FDI trends reduced it. Although the PiS government’s more generous regional aid to foreign investors corresponds to the growth in FDI stock, regional aid practices do not reflect the similar FDI pattern in Czechia.

A shift in the sectoral composition of FDI towards manufacturing may have led to an increase in regional aid expenditure because capital-intensive manufacturing projects tend to receive high amounts of aid. However, since 2005, with the exception of Hungary, the share of manufacturing FDI in total FDI stock gradually declined in the V4 (see Figure A4 in the Online Supplement). In Hungary, the huge slump in the figure in 2015 was caused by General Electric’s reorganisation of its energy division, which involved the sale of its Hungarian subsidiary to a Swiss subsidiary, and the magnitude of this transaction heavily influenced Hungary’s national accounts (Máténé Bella & Ritzlné Kazimir, Citation2020). The recovery in the figure in 2016 is related to a more than 40 per cent drop in FDI stock in financial services due to the government’s purchase of several foreign-owned banks (Karas, Citation2022). In subsequent years, the share of manufacturing FDI in total FDI stock in Hungary remained stable around 43 per cent, despite the government’s increased spending on regional aid.

Greater aid generosity could potentially also compensate for declining competitiveness, but the World Competitiveness Index of Hungary and Poland (see Figure A5 in the Online Supplement) has shown stability since 2010, so this could not have motivated an increase in aid either. Poland’s ranking deteriorated only very recently, in 2021–2022, while Hungary’s position improved slightly in these two years. The Czech index remained stable throughout the period, while Slovakia lost some of its former position after 2016 but Slovak regional aid practices did not seem to compensate for this.

As multinationals already present in the host country may have insider links with the government, their reinvested profits may encourage governments to provide regional aid to them. Indeed, reinvestment is a stable source of FDI in the V4 but it does not convincingly explain why economic nationalists in Hungary and Poland increased regional aid to foreign firms. As the data show, reinvested earnings as a percentage of GDP have been very similar in Czechia and Poland since the 2008 crisis, although their regional aid practices have become increasingly divergent (see Figure A6 in the Online Supplement). Slovakia shows a more volatile trend in these figures, while reinvested earnings in Hungary increased considerably after 2013. Thus, in Hungary the increase in reinvested earnings seems to correspond to an increase in regional aid. However, a closer look at the data (see Figure A7 in the Online Supplement) does not suggest a direct link between the two figures. The big jump in the granting of regional aid to foreign firms compared to previous years occurred after 2018, when reinvested earnings fell after peaking at almost 5 per cent of GDP in 2017. In 2021, when Hungary recorded the highest ever amount of regional aid disbursed to foreign companies (EUR 720 million), this figure dropped to 3.5 per cent.

Of course, the above facts do not rule out the possibility that central governments are more likely to provide aid to those foreign companies with which they have close ties. In the V4, the Orbán government developed the closest relations with German investors (Panyi, Citation2020) that regularly received regional aid from the government. However, this is not surprising because Germany is the largest European investor in the V4, and as German multinationals usually establish capital-intensive manufacturing activities, they tend to take a larger share of the total aid. German companies are on average satisfied with their experience in the V4 (see Figure A8 in the Online Supplement). However, our data does not suggest that German firms received special treatment compared to other foreign investors. As shows, in Hungary, the share of regional investment aid to German companies out of all aid granted to foreign investors was almost identical during the socialist-liberal government in 2002–2010 and the Orbán cabinet (32 vs. 33 per cent), which is very close to the share they received in Czechia. Although the Orbán government has been more generous to foreign investors overall than previous Hungarian governments, German firms have not received a bigger slice of this larger ‘pie’. Moreover, after 2019, when Fidesz was suspended from the European People’s Party, which is dominated by German Christian Democrats, German firms’ share of regional aid for foreign firms fell from 47 per cent (between 2010 and 2018) to 25 per cent. The recent increase in government pressure on German retail and construction firms to leave Hungary (Puhl & Sauga, Citation2023) also means that the country of origin is not bailing them out in sectors where the government wants to increase Hungarian ownership. While export-oriented German manufacturing firms praise the Orbán government for its strong support for their industry, German firms in other sectors report a conflictual relationship with the government (Sallai et al., Citation2023). This suggests a selective approach to foreign investors driven by an autocratic hedging strategy rather than intimate business-state relations.

The example of the PiS government’s pragmatic stance to German investors also demonstrates that the use of regional investment aid is instrumental rather than ideological. Foreign firms are thus used as ‘external rebalancers’ for legitimising the regime (Camba & Epstein, Citation2023). During the first coalition government led by the PiS in 2005–2007, only one German firm received regional aid, which may reflect the strong Germanophobe attitude of the party. However, after they had returned to power in 2015, they substantially increased the share of German companies from regional investment aid. Compared to the previous centre-right government, the PiS coalition more than doubled the share of regional aid to German companies (25 vs. 11 per cent, see ). This change is driven by the recognition of Germany’s important role in the Polish economy, rather than a shift in PiS’s ideological position. As PM Morawiecki expressed, Germany was the leading economic partner of Poland and the relations developed based on qualified workforce, infrastructure and investment incentives (i.e., regional investment aid), thus nothing beyond pure business.Footnote6 Commenting on a new German greenfield investment he indirectly reflected on the rise of the Polish economy and portrayed Poland as an equal economic partner: ‘Not so long ago, Poles used to go to Germany to pick asparagus. Today, German technological investments are coming to Poland’ (Kędzierski, Citation2022). Another indication of the far from cordial relationship between the PiS government and German investors was that the government filed an official complaint to the European Commission against illegal waste transportation by German companies to PolandFootnote7. Nevertheless, the PiS-led coalition kept subsidising German firms through regional investment aid because of the anticipated economic gains and the investments’ legitimising effect.

Further evidence for autocratic hedging can be traced in how Hungarian and Polish economic nationalists emphasised their countries’ economic performance and how they sought support from powerful external rebalancers. Former Polish Deputy PM Konrad Szymański expressed that Poland’s position in the EU was clearly influenced by its economic success (Bayer, Citation2018), while PM Morawiecki declared that Poland had successfully attracted foreign investors that were the litmus test of a country’s position in the international arena (PAP, Citation2023). Similarly, PM Orbán boasted about Hungary’s record investment and exports in 2022–2023, despite the suspension of EU funding to the country (Orbán, Citation2023). During a recent visit to China, Hungarian Minister of Economic Development expressed the government’s desire to become the region’s top destination for Chinese investors and urged more Chinese investment in Hungary (Losonczi, Citation2023). Meanwhile, the PiS government generously subsidised US tech giant Intel’s new investment, the largest foreign investment project ever in Poland (Hartmann, Citation2023). Morawiecki commented that his government was ‘particularly happy to cement and consolidate transatlantic cooperation’ with the US through Intel’s project (The Chancellery of the Prime Minister, Citation2023). These developments suggest that both the Hungarian and Polish governments used foreign investment as legitimisers for their autocratic-leaning regimes, a clear indication of a hedging strategy. At the same time, these moves contradict their anti-FDI rhetoric and reinforce the FDI-dependent economic model.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have refined the argument for the stability of FDI-dependent market economies in ECE and provided novel empirical evidence on this topic. We have shown that one of the backbones of systemic stability is a particular domain of European state aid policy, regional investment aid, whose regulatory framework is embedded in the East–West development gap. As relatively backward EU members, regional state aid rules provide ECE governments with considerable policy space to promote investment. Using a comprehensive dataset on regional investment aid in the V4, we showed that, irrespective of their ideological background, central governments granted the vast majority of regional investment aid to foreign firms.

While the reinforcement of FDI-led growth through regional aid can be partly explained by structural economic constraints (i.e., growth is highly dependent on the export performance of foreign-dominated sectors), this argument does not fully apply in the case of economic nationalists who question the exposure to foreign capital and, at least in their political rhetoric, challenge the dependent economic model. We have shown that instead of providing regional aid to foster mutually beneficial informal ties between multinationals and the political elite, economic nationalists used this policy tool instrumentally as part of their hedging strategy. The politicisation of the dependent market economy by economic nationalists in Hungary and Poland does not mean that they reject FDI dependence altogether. We have shown that, as their European political isolation grew, they increasingly resorted to the promotion of foreign investment, ultimately granting more aid to foreign firms than their non-nationalist predecessors. On the one hand, FDI may to some extent replace the suspended EU funds. On the other hand, the selective economic nationalism of both governments served short-term political goals. This means that they have used investment aid to attract foreign investors to certain sectors of the economy to gain external approval and increase domestic output legitimacy through the contribution of these investments to employment and growth.

We have also shown that ECE governments enjoy more economic agency than would follow from the dependent market economy model. Ironically, the ability of economic nationalists in ECE to challenge European democratic values may depend on their capacity to maintain the FDI-led growth model that is deeply embedded in European and global markets. As long as they can ensure the continued flow of foreign capital, they may secure external and domestic support to continue their political divergence from the European mainstream, although the defeat of the PiS government in Poland’s 2023 parliamentary elections shows that successful hedging may not be enough to stay in power.

Continued reliance on FDI may reinforce the functional specialisation of these economies in low value-added manufacturing, although there are some notable exceptions of supported high value-added foreign firms, especially in Poland. The question then is whether economic upgrading is possible in ECE when the main contributors to economic growth are foreign firms enjoying a low-cost advantage and generous investment support. Nevertheless, upgrading would be essential to substantially reduce the East–West development gap and to prevent the further strengthening of those political forces that undermine European integration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (223.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at an international workshop organised at the Centre for Social Sciences in Budapest in 2022 and at the 2022 CEPSA and the 2022 EACES conference. We thank the constructive and insightful comments of Dorothee Bohle, Nils Oellerich, and three anonymous reviewers. We are grateful to Adam Fagan, Cristian Neculai-Surubaru, Rachel A. Epstein and Clara Volintiru for inviting us to the special issue and for their great feedback and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gergő Medve-Bálint

Gergő Medve-Bálint is an associate professor at the Institute of Social and Political Sciences at the Corvinus University of Budapest and a senior research fellow at the Institute for Political Science, HUN-REN Centre for Social Sciences, Budapest, Hungary. His research lies at the intersection of comparative and international political economy, focusing on institutional stability and change in (semi-)peripheral growth regimes in Europe, and exploring the role of industrial and regional policies in economic upgrading and stagnation in these economies. His publications have appeared in JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, Studies in Comparative International Development, Review of International Political Economy, East European Politics, Competition and Change, among others.

Andrea Éltető

Andrea Éltető is a senior research fellow at the Institute of World Economics, HUN-REN Centre for Economic and Regional Studies (IWE CERS), in Budapest, where she is the leader of the Integration Research Group. Her fields of research include foreign direct investment in Central Europe, global value chains, industrial policy, foreign trade, EU integration and political economy of Hungary. She regularly publishes in and reviews articles for higher-ranked international and local economic journals (such as Competition & Change, European Journal of International Management and Intersections: East European Journal of Society and Politics). She has coordinated several international and national research projects, funded by the International Visegrad Fund, EULAC and the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office, among others.

Notes

2 These aid schemes (Poland: SA.18043, SA.22361, SA.24543, SA.24413, SA.25696, SA. 38730, Slovakia: SA.21786, SA. 24172, SA. 25884, Hungary: SA.25641, SA. 22707, Czechia: SA.17738, SA.22409) have been adjusted to the EU’s budgetary cycles and have been regularly updated or extended with further budget allocations.

3 Sobotka held his speech at the Prague International Symposium on Foreign Direct Investments, Prague, Hrzán Palace, 19 February 2014.

4 The Czech regional state aid data (https://www.czechinvest.org/en/For-Investors/Investment-Incentives) is available on CzechInvest’s website, which is the national investment promotion agency. The Slovak data is published by the Ministry of Economy (https://www.economy.gov.sk/uploads/files/Rvg2Rhsh.xlsx), the Hungarian (https://cdn.kormany.hu/uploads/document/c/c6/c63/c63982fb6469a8c5025694659e9dac4f4cc68e2f.pdf) by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the annual state aid reports of the Polish competition authority are the sources of the Polish data (https://uokik.gov.pl/raporty_i_analizy2.php).

5 The full dataset on regional investment aid is available as supplementary material to this paper.

References

- Ádám, Z. (2019). Explaining orbán: A political transaction cost theory of authoritarian populism. Problems of Post-Communism, 66(6), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2019.1643249

- Ambroziak, A. A. (2022). State aid in the European union. Similarities and differences among Visegrad group countries. In M. Staníčková & L. Melecký (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th international conference on European integration 2022 (pp. 29–38). VSB – Technical University of Ostrava. https://doi.org/10.31490/9788024846057

- Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., & Pontusson, J. (2022). Diminishing returns: The new politics of growth and stagnation. Oxford University Press.

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2019). Social blocs and growth models: An analytical framework with Germany and Sweden as illustrative cases (Unequal Democracies: Working Papers, 7). https://unequaldemocracies.unige.ch/files/7815/5421/4353/wp7.pdf

- Ban, C., & Adascalitei, D. (2022). The FDI-Led growth models of the east-central and the south-eastern European periphery. In L. Baccaro, M. Blyth, & J. Pontusson (Eds.), Diminishing returns. The new politics of growth and stagnation (pp. 189–209). Oxford University Press.

- Ban, C., Scheiring, G., & Vasile, M. (2023). The political economy of national-neoliberalism. European Politics and Society, 24(1), 96–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2021.1956241

- Bayer, L. (2018). Europe’s eastern tigers roar ahead. Politico. 23 January 2018. https://www.politico.eu/article/central-and-eastern-eu-gdp-growth-economies/

- Bluhm, K., & Varga, M. (2020). Conservative developmental statism in East Central Europe and Russia. New Political Economy, 25(4), 642–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1639146

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. (2009). Varieties of capitalism and capitalism « tout court ». European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 50(3), 355–386. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975609990178

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. (2012). Capitalist diversity on Europe’s periphery. Cornell University Press.

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. (2019). Politicising embedded neoliberalism: Continuity and change in Hungary’s development model. West European Politics, 42(5), 1069–1093. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1511958

- Bohle, D., & Regan, A. (2021). The comparative political economy of growth models: Explaining the continuity of FDI-led growth in Ireland and Hungary. Politics & Society, 49(1), 75–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220985723

- Börzel, T. A., & Langbein, J. (2019). Core–periphery disparities in Europe: Is there a link between political and economic divergence? West European Politics, 42(5), 941–964. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1558534

- Brazys, S., & Regan, A. (2017). The politics of capitalist diversity in Europe: Explaining Ireland’s divergent recovery from the euro crisis. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717000093

- Bruszt, L., & Langbein, J. (2020). Manufacturing development: How transnational market integration shapes opportunities and capacities for development in Europe’s three peripheries. Review of International Political Economy, 27(5), 996–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1726790

- Camba, A., & Epstein, R. A. (2023). From Duterte to Orbán: The political economy of autocratic hedging. Journal of International Relations and Development, 26(2), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-022-00287-7

- The Chancellery of the Prime Minister. (2023). Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki: It is of immense importance that Poland will be the location for investments that ensure security and influence technological development. Gov.Pl. 16 June 2023. https://www.gov.pl/web/primeminister/prime-minister-mateusz-morawiecki-it-is-of-immense-importance-that-poland-will-be-the-location-for-investments-that-ensure-security-and-influence-technological-development

- Cini, M. (2001). The soft law approach: Commission rule-making in the EU’s state aid regime. Journal of European Public Policy, 8(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110041541

- Clift, B., & Woll, C. (2012). Economic patriotism: Reinventing control over open markets. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(3), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.638117

- Coman, R., & Volintiru, C. (2023). Anti-liberal ideas and institutional change in Central and Eastern Europe. European Politics and Society, 24(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2021.1956236

- Crouch, C. (2019). The globalization backlash. Polity Press.

- Culpepper, P. D. (2010). Quiet politics and business power. Corporate control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Domański, B. (2005). Transnational corporations and the post-socialist economy: Learning the ropes and forging new relationships in contemporary Poland. In C. G. Alvstam & E. W. Schamp (Eds.), Linking industries across the world: Processes of global networking (pp. 147–172). Ashgate Publishing.

- Drahokoupil, J. (2009). Globalization and the state in central and eastern Europe: The politics of foreign direct investment. Routledge.

- Epstein, R. A. (2020). The economic successes and sources of discontent in East Central Europe. Canadian Journal of European and Russian Studies, 13(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.22215/cjers.v13i2.2619

- Evans, P. (1979). Dependent development: The alliance of multinational, state, and local capital in Brazil. Princeton University Press.

- Feldmann, M., & Morgan, G. (2022). Business elites and populism: Understanding business responses. New Political Economy, 27(2), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1973397

- Galgóczi, B., & Drahokoupil, J. (Eds.). (2017). Condemned to be left behind? Can Central and Eastern Europe emerge from its low-wage model? European Trade Union Institute (ETUI). https://www.etui.org/content/download/32615/302859/file/post-FDI-WEB.pdf

- Gerőcs, T., & Pinkasz, A. (2019). Relocation, standardization and vertical specialization: Core–periphery relations in the European automotive value chain. Society and Economy, 41(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2019.001

- Gerschewski, J. (2013). The three pillars of stability: Legitimation, repression, and co-optation in autocratic regimes. Democratization, 20(1), 13–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738860

- Győrffy, D. (2022). The middle-income trap in Central and Eastern Europe in the 2010s: Institutions and divergent growth models. Comparative European Politics, 20(1), 90–113. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00264-3

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Hartmann, T. (2023). Intel launches ‘largest investment in Polish history’. 16 June 2023. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/industrial-strategy/news/intel-launches-largest-investment-in-polish-history/.

- Heimler, A., & Jenny, F. (2012). The limitations of European Union control of state aid. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 28(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grs005

- Höpner, M., & Schäfer, A. (2015). Integration among unequals: How the heterogeneity of European varieties of capitalism shapes the social and democratic potential of the EU. In J. M. Magone (Ed.), Routledge handbook of European politics (pp. 725–745). Routledge.

- Johnson, J., & Barnes, A. (2015). Financial nationalism and its international enablers: The Hungarian experience. Review of International Political Economy, 22(3), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2014.919336

- Johnston, A., & Matthijs, M. (2022). The political economy of the eurozone’s post-crisis growth model. In L. Baccaro, M. Blyth, & J. Pontusson (Eds.), Diminishing returns. The new politics of growth and stagnation (pp. 117–142). Oxford University Press.

- Johnston, A., & Regan, A. (2016). European monetary integration and the incompatibility of national varieties of capitalism. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(2), 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12289

- Johnston, A., & Regan, A. (2018). Introduction: Is the European union capable of integrating diverse models of capitalism? New Political Economy, 23(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1370442

- Karas, D. (2022). Financialization and state capitalism in Hungary after the global financial crisis. Competition & Change, 26(1), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294211003274

- Kędzierski, R. (2022). Niemcy zbudują w Polsce olbrzymią fabrykę, Morawiecki przypomina, gdzie Polacy jeździli na szparagi. nextgazetapl. 15 July 2022. https://next.gazeta.pl/next/7,151003,28690650,niemcy-zbuduja-w-polsce-olbrzymia-fabryke-morawiecki-przypomina.html

- Kołodko, G. W. (2023). Global consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Springer.

- Lindstrom, N. (2021). Aiding the state: Administrative capacity and creative compliance with European state aid rules in new member states. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(11), 1789–1806. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1791935

- Losonczi, M. (2023). Hungary committed to becoming region’s top destination for Chinese investors, Minister States in Shanghai. Hungarian Conservative. 6 November 2023. https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/current/hungary_regions_top_destination_for_chinese_investors_minister_nagy_shanghai_expo/

- Máténé Bella, K., & Ritzlné Kazimir, I. (2020). Effects of multinational corporations’ strategic decisions on the production side of Hungarian GDP. Statisztikai Szemle, 98(3), 212–241. https://doi.org/10.20311/stat2020.3.hu0212

- Medve-Bálint, G. (2014). The role of the EU in shaping FDI flows to East Central Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12077

- Mérő, K., & Piroska, D. (2016). Banking union and banking nationalism—explaining opt-out choices of Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. Policy and Society, 35(3), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2016.10.001

- Myant, M. (2018). Dependent capitalism and the middle-income trap in Europe and East Central Europe. International Journal of Management and Economics, 54(4), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.2478/ijme-2018-0028

- Naczyk, M. (2022). Taking back control: Comprador bankers and managerial developmentalism in Poland. Review of International Political Economy, 29(5), 1650–1674. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1924831

- Nölke, A., & Vliegenthart, A. (2009). Enlarging the varieties of capitalism: The emergence of dependent market economies in East Central Europe. World Politics, 61(4), 670–702.

- Oellerich, N. (2022). Promoting domestic bank ownership in central and eastern Europe: A case study of economic nationalism and rent-seeking in Hungary. East European Politics, 38(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2021.1937137

- Orbán, V. (2023). Viktor Orbán’s speech at the anniversary celebrations of Weltwoche weekly. 22 November 2023. https://miniszterelnok.hu/orban-viktor-eloadasa-a-weltwoche-hetilap-jubileumi-unnepsegen/

- Panyi, S. (2020). How Orbán played Germany, Europe’s great power. Direkt36.Hu. 18 September 2020. https://www.direkt36.hu/en/a-magyar-nemet-kapcsolatok-rejtett-tortenete/

- PAP. (2023). Otwarcie nowej fabryki PepsiCO. Premier: Będzie tu ponad 600 miejsc pracy. Polish Press Agency. 31 May 2023. https://www.pap.pl/aktualnosci/news%2C1579111%2Cotwarcie-nowej-fabryki-pepsico-premier-bedzie-tu-ponad-600-miejsc-pracy

- Puhl, J., & Sauga, M. (2023). ‘Mafia methods’: Viktor Orbán ups the pressure on German companies to leave Hungary. Der Spiegel. 31 March 2023. https://www.spiegel.de/international/business/mafia-methods-viktor-orban-ups-the-pressure-on-german-companies-to-leave-hungary-a-cf38f4d2-1576-4f55-896a-b65f19542f43

- Riedel, R. (2020). Undermining the standards of liberal democracy within the European union: The polish case and the limits of post-enlargement democratic conditionality. In J. Bátora & J. E. Fossum (Eds.), Towards a segmented European political order (pp. 175–205). Routledge.

- Riedel, R. (2021). Poland and the middle-income trap. In A. Visvizi, A. Matysek-Jedrych, & K. Mroczek-Dabrowska (Eds.), Poland in the single market (pp. 86–102). Routledge.

- Sallai, D., Schnyder, G., Kinderman, D., & Nölke, A. (2023). The antecedents of MNC political risk and uncertainty under right-wing populist governments. Journal of International Business Policy. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-023-00154-3

- Šćepanović, V. (2013). FDI as a solution to the challenges of late development: Catch-up without convergence? PhD Dissertation. Budapest: Central European University. http://www.etd.ceu.hu/2014/scepanovic_vera.pdf

- Scharpf, F. W. (1970). Demokratietheorie zwischen Utopie und Anpassung. Universitätsverlag.

- Scheiring, G. (2020). The retreat of liberal democracy. Authoritarian capitalism and the accumulative state in Hungary. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Scheiring, G. (2021). Varieties of dependency, varieties of populism: Neoliberalism and the populist countermovements in the Visegrád four. Europe-Asia Studies, 73(9), 1569–1595. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.1973376

- Schito, M. (2022). The effects of state aid policy trade-offs on FDI openness in Central and Eastern European Countries. International Review of Public Policy, 4(2). Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4000/irpp.2725

- Sebők, M., & Simons, J. (2022). How Orbán won? Neoliberal disenchantment and the grand strategy of financial nationalism to reconstruct capitalism and regain autonomy. Socio-Economic Review, 20(4), 1625–1651. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab052

- Šitera, D. (2021). Exploring neoliberal resilience: The transnational politics of austerity in Czechia. Journal of International Relations and Development, 24(3), 781–810. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-021-00214-2

- Szent-Iványi, B. (Ed.). (2017). Foreign direct investment in central and eastern Europe: Post-crisis perspectives. Springer.

- Toplišek, A. (2020). The political economy of populist rule in post-crisis Europe: Hungary and Poland. New Political Economy, 25(3), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598960

- Tőrös, Á., Mészáros, Á., & Dani, Á. (2017). Investment promotion in the Visegrad Countries: A comparative analysis. In B. Szent-Iványi (Ed.), Foreign direct investment in central and eastern Europe: Post-crisis perspectives (pp. 193–217). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40496-7_9

- Volintiru, C., Bargaoanu, A., Ștefan, G., & Durach, F. (2021). East-west divide in the European Union: Legacy or developmental failure? Romanian Journal of European Affairs, 21(1), 93–118.

- Vukov, V. (2020). More Catholic than the Pope? Europeanisation, industrial policy and transnationalised capitalism in Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(10), 1546–1564. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1684976

- Vukov, V. (2021). Dependency, development, and the politics of growth models in Europe’s peripheries. In A. Madariaga & S. Palestini (Eds.), Dependent capitalisms in contemporary Latin America and Europe (pp. 157–181). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71315-7_7

- Vukov, V. (2023). Growth models in Europe’s eastern and southern peripheries: Between national and EU politics. New Political Economy, 28(5), 832–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2023.2189695

- Wróblewska, D. (2022). Regional investment aid in Poland and Czechia. Review of European and Comparative Law, 50(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.31743/recl.13960