ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to analyse which ecological conditions (professional background and support from the environment) and interpersonal skills (values, attitudes and emotional competences) predict ECE teacher competences in working with immigrant children. The results of the hierarchical regression analysis revealed that interpersonal skills are stronger predictors of teachers’ competences than ecological conditions. The results of network analysis indicate specific in-depth relations among teachers’ competences and the analysed variables. The study is important as it combines ecological conditions as contextual factors and interpersonal skills to better understand how to support ECE teachers in a multicultural environment.

Introduction

Teachers in early childhood education (ECE) face several challenges in working with immigrant children. The most common challenges concern how to appropriately adapt ECE programmes for multicultural education (Tobin Citation2020; Chan Citation2011; Onchwari, Ariri, and Keengwe Citation2008), to deal with stereotypes and prejudices toward immigrant children and families (Keys Adair Citation2012), to overcome challenges related to language learning (Moin, Schwartz, and Breitkopf Citation2011; Pacini-Ketchabaw and Armstrong de Almeida Citation2006), to provide an inclusive environment and facilitate a successful collaboration with parents (Lazzari et al. Citation2020; Block et al. Citation2014; Souto-Manning Citation2007). Research also shows that teachers often report they feel unprepared to work with immigrant children, mostly because they received little or no preparation for teaching in a multicultural educational environment (Licardo Citation2020; Tobin Citation2020; Tobin, Keys Adair, and Arzubiaga Citation2013; Jerlean and Friedman Citation2005). They mostly develop their competences in work with immigrant children in everyday practice, which is based on their attitudes, values, beliefs, experiences, environment support, and self-education; all of which can broadly differ between individual teachers (Tobin, Keys Adair, and Arzubiaga Citation2013; Ray and Bowman Citation2003; Firstater, Sigad, and Frankel Citation2015).

Teacher competences are vital because the experiences of immigrant children in early education set the foundation for positive relationships between parents, kindergartens, children’s educational achievements, can alleviate disadvantages and increase equity (Pianta, Steinberg, and Rollins Citation1995; Genishi and Dyson Citation2009; Matthews, Ulrich, and Cervantes Citation2018; UNHCR et al. Citation2019). Capacity building for ECE professionals is also recognised as one of the key recommendations in helping refugee and migrant children access quality education (UNHCR et al. Citation2019; UNESCO Citation2018). On the other hand, lack of good educational practice with immigrant children has a negative impact on children’s long-term capabilities to overcome discrimination in wider society and achieve educational success (Janta and Harte Citation2016; Gandara and Contreras Citation2009).

ECE teacher competences in literature are defined as qualities of individual teacher, that can be acquired through training and continuing professional development. Competences of individuals include series of skills and specific knowledge to perform a particular task. Being and becoming competent teacher is a continuous process that comprises the ability to gain professional knowledge, practice and to develop and show professional values (Urban et al. Citation2012). It is also important to understand that competences cannot simply be understood as individual responsibility of ECE teachers (Peeters and Sharmahd Citation2014). Environment support is crucial in terms of relationships on the level of individuals, teams, institutions, and policy (Urban et al. Citation2012). Interpersonal skills (e. g. positive teacher values, emotional competences, and positive teacher attitudes toward teaching immigrant children) are the common description of specific competences which are independent variables in this study. These variables are understood in both terms here, as individual competences or skills.

The current literature on teacher competences in working with immigrant children is largely focused on qualitative research as project reports, good practices, or specific case studies (e.g. Lazzari et al. Citation2020; Van Katrien and Vandenbroeck Citation2017; Iddings and Reyes Citation2017; Jahng Citation2014). Research including ecological conditions and interpersonal skills facilitating a better understanding of the development of teacher competences is scarce; some authors even refer to it as a great silence in literature (McDevitt Citation2020; Chan and Ritchie Citation2019; Keys Adair Citation2011). Atiles, Douglas, and Allexsaht-Snider (Citation2017) report that teachers’ multicultural approach – comprehending teachers’ values regarding others, their ability to emotionally regulate themselves and others, and their positive attitude towards immigrant pupils – appear to be significantly linked to their sense of efficacy when working with immigrant students. Keys Adair (Citation2011) argues that listening to the perspective of teachers within their own context and professional background adds a new dimension and logic to the education of immigrant children.

Our aim is to fill this gap in the research and to combine ecological conditions, contextual factors, and interpersonal skills to better understand how to support teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children. The purpose of the study is to analyse the specific predictors of ECE teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children. More specifically, how do various ecological conditions (demographic variables – DV and support from environment – SE) and interpersonal skills (teachers’ positive values – TV, emotional competences – EC, teachers’ positive attitudes toward teaching immigrant children – TA) predict the competences of ECE teachers in working with immigrant children (TC).

Methods

Participants and data collection

The participants (n = 348) in the study are ECE teachers (n = 185) and ECE teacher assistants (n = 163) in Slovenia. We address both groups as ECE teachers as both are professionals in ECE. The majority (95.7%) of them are female. Most of the ECE teachers have bachelor’s (50%) and master’s degrees (35.9%). Similarly, the majority of ECE teacher assistants have an upper secondary education (71.8%), whilst all other assistants have a higher education level. In Slovenia, the minimum requirement for teacher assistants is an ECE bachelor’s degree. In all participants, the four largest groups by years of work experience are 25.9% with 6 to 10 years of work experience, 18.7% with 31 or more years of work experience, 16.7% with up to 5 years of work experience, and 14.4% with 16 to 20 years of work experience. Their age ranges from between 18 to more than 56 years. The four largest age groups are 32.8% between 36 and 40 years, 15.5% between 24 and 29 years, 13.2% of 56 years or more, and 12.1% between 30 and 35 years. ECE teachers in Slovenian kindergartens work in groups of children age 1 to 6 years.

The participants were from different regions in Slovenia, varying from village (n = 33, 9.5%), town (n = 34, 9.8%), or city (n = 281, 80.7%). They were recruited via e-mails or by personal contact from the researchers. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of their anonymous and confidential participation. They had the opportunity to contact the researchers in case of questions and comments. No personal data were collected. Informed consent for participation in the study and for publication of the results was obtained from participants. The data were collected during the middle of the school year 2019. The study was approved by the appropriate institutional ethics committee.

The instrument

Our intention was primarily focused on the research of competences. We designed and validated the instrument for the purpose of this study. It is a self-reported questionnaire for ECE teachers examining five measures: one addressing ecological conditions (SE – support from environment), three addressing interpersonal skills (TA – positive teacher attitudes, TV – teacher positive values, and EC – teacher emotional competences) and one addressing teacher competences in working with immigrant children (TC). For all measures, a five-point Likert scale was used. Principal component analysis (PCA) established the discriminant validity of the constructs and dismissed possible common method bias concerns with SPSS. PCA was also conducted to reduce the larger set of variables that retain the most relevant information about their common variance. In general, the instrument exhibited appropriate internal consistency and Cronbach’s alpha values for most of the dimensions are high (≥.70), with a few dimensions presenting acceptable results below this criteria (Cortina Citation1993; Griethuijsen et al. Citation2014; Taber Citation2017).

Description of the measures:

Support from the educational environment (SE) measures resources and support options in the educational environment. The scale generated three components. Component 1 (α = .80) comprised four items that explained 41% of the variance with loadings from .71 to .85; Component 2 (α = .76) comprised two items that explained 18% of the variance with loadings from .85 to .90; and Component 3 (α = .57) comprised two items that explained 13% of the variance with loadings from .63 to .91.

Teacher competences in working with immigrant children (TC) measures ECE teachers’ knowledge of different methods for teaching immigrant children. The scale generated three components. Component 1 (α = .78) comprised four items that explained 36% of the variance with loadings from .67 to .88; Component 2 (α = .69) comprised four items that explained 12% of the variance with loadings from .38 to .78; and Component 3 (α = .73) comprised five items that explained 10% of the variance with loadings from .44 to .90.

Teacher values (TV) measures how teachers are involved in supporting others and relating to them equally. The scale generated one component (α = .61) comprised of five items that explained 39% of the variance with loadings from .54 to .74.

Emotional competences (EC) measures teachers’ ability to perceive, regulate, integrate, and understand their own emotions and the emotions of others. The scale generated six components. Component 1 (α = .90) comprised four items that explained 30% of the variance with loadings from .68 to .93; Component 2 (α = .81) comprised three items that explained 13% of the variance with loadings from .53 to .90; Component 3 (α = .81) comprised five items that explained 11% of the variance with loadings from .48 to .75; Component 4 (α = .79) comprised two items that explained 8% of the variance with loadings from .86 to .91; Component 5 (α = .71) comprised three items that explained 6% of the variance with loadings from .55 to .81; and Component 6 (α = .68) comprised three items that explained 5% of the variance with loadings from .67 to .78.

Teacher attitudes (TA) measures positive attitudes toward immigrant children, for example, how teachers believe that immigrant children can be successfully integrated in lessons. The scale generated one component (α = .70) comprised of four items that explained 54% of the variance with loadings from .71 to .73.

Demographic variables (DV) include gender, age groups, years of work experience (labelled by year groups), job position (ECE teacher, ECE teacher assistant), level of education (i.e. upper secondary, Bachelor and Master degrees), and location of kindergarten (i.e. village, town or city).

In the supplemental online material on Figshare, we provide a codebook for network analysis and databasing (Licardo Citation2020a).

Analyses

The proposed research was first analysed using a correlation matrix (Pearson correlation coefficient) and a hierarchical regression analysis (HRA) in SPSS. When entering predictor variables for teacher competences (TC) into the regression model, control variables (demographic variables and professional background as part of ecological conditions) were entered in the first step (i.e. gender, age, years of work experience, job position, level of education). Support from the environment (SE) was entered in the second step and interpersonal variables (TV, EC, TA) in the third.

Further, the R package qgraph was used to create a network analysis (NA) for better visualisation of the correlation matrix of all variables (Epskamp et al. Citation2012). The network model used an iterative process based on the positive and negative correlations of each item from all the scales. Therefore, the item correlation patterns (green strings for positive and red strings for negative) set the placement of the network nodes, computing a layout in which the length of the edges depends on their absolute weight (i.e. shorter edges for stronger weights), showing how variables cluster.

This study opted to explore both HRA and NA procedures to better understand the interactive processes of the factors being investigated. Using complementary statistical analysis with different calculations and even assumptions, the study provides a more comprehensive understanding that would not be possible with only one of these procedures. While the HRA makes it possible to specify how predictor and outcome variables are connected via linear regressions in our model (Abbott Citation2016), the NA amplifies the possibilities of interdependencies among all variables and conceptualises constructs as dynamical systems (Schmittmann et al. Citation2013).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities are presented in .

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations of sum variables.

Descriptive statistics indicate that ECE teachers perceive medium support from environment (SE) in working with immigrant children. From the mean values of individual items for SE, we can conclude that they need more immigrant children’s literature (M = 2.58; SD = 1.00), more support from the interpreters and translators (M = 2.72; SD = 1.16), more support from governmental institutions (M = 2.74; SD = .75), and more support from NGOs that work with immigrants (M = 2.99; SD = 1.13). The highest mean value in SE is for counselling services in kindergarten (M = 3.19; SD = 1.18).

Teacher competences in working with immigrant children (TC) presented medium average (M = 3.01; SD = .62) and indicated lower competences in several variables. For example, they rarely use other language inscriptions in the classroom and dressing room (M = 2.14; SD = 1.12), bilingual books and immigrant children literature (M = 2.18; SD = 1.14), or individualised education plans for immigrant children (M = 2.20; SD = 1.25). They also express a lack of knowledge of: different methods for working with immigrant children (M = 2.57; SD = .93), using specific methods to work with immigrant children (M = 2.56; SD = .93), legislation and guidelines that define educational work with immigrant children (M = 2.78; SD = 1.01), and rarely or sometimes prepare alternative activities for immigrant children when they are unable to keep up with the group (M = 2.80; SD = .98). The highest mean value for TC was the self-assessed development of tolerance and understanding of host country customs and the customs of other cultures (M = 4.30; SD = .91).

The constructs correlated positively with each other and all reported significant correlations were low to moderate. SE in working with immigrant children positively correlated with teachers’ competences, teachers’ values, and attitudes to work with immigrant children. Teacher competences positively correlated with teachers’ values, emotional competences, and teacher attitudes. These correlations are among the strongest and indicate that interpersonal skills are more important in working with immigrant children than ecological conditions.

Ecological and interpersonal skills as predictors of ECE teacher competences in working with immigrant children

presents the results of HRA in three steps: entering demographic data and professional background (as ecological conditions) in step 1, support from the environment (as part of ecological conditions) in step 2, and the interpersonal skills of ECE teachers in step 3.

Table 2. Hierarchical multiple regression for sum variables predicting teacher competences in working with immigrant children.

First, a regression analysis was conducted with the ECE teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children. As illustrated in , control variables entered in the first step accounted for 9% of variance, with years of work experience and job position being the positive and strongest predictor of ECE teachers’ competences in work with immigrant children. HRA indicates that teachers with more experience have more competences in their working with immigrant children. Further, professionals employed as teachers have more competences than those who are teacher assistants, which is not surprising if we consider the specifics of job positions and education levels for each role (Urban et al. Citation2012). Other demographic variables as ecological conditions did not show significant results in step 1 of the model. Support from environment entered in step 2 accounted for 4% of variance, with SE being a positive predictor of ECE teachers’ competences in work with immigrant children. The explained variance with specific ecological conditions in step 2 accounts for a total of 13%, with years of work experience, level of education, and environment support being positive predictors of teachers’ competences. We also notice that in step 2 (and 3), kindergarten location is a negative predictor of competences, which means that ECE teachers in smaller rural areas (e.g. villages) report fewer competences than ECE teachers in cities.

In the third step, interpersonal skills and competences in working with immigrant children were entered. They accounted for 19% of the explained variance; these results may be considered of practical significance. The strongest positive predictor among interpersonal skills is positive teacher attitudes toward teaching immigrant children, following teachers’ values and emotional competences. The results indicate that ecological conditions are less important as predictors in comparison to interpersonal skills. Results in step 3 also indicate that beside the interpersonal skills, a significant ecological predictor is the level of education, meaning that teachers with higher levels of education report higher competences in their working with immigrant children, while years of work experience tends to be less important as a predictor in step 3.

Next, we analysed the same data using the NA approach, which allowed us to understand the phenomenon under investigation as a dynamic system compounded by independent variables. From this perspective, variable clusters (strong correlation) compound factors which are central and more difficult to change, while there are peripheral factors with less relevance for the whole system (Schmittmann et al. Citation2013).

Dynamic relationships between ecological and interpersonal skills related to ECE teacher competences in working with immigrant children

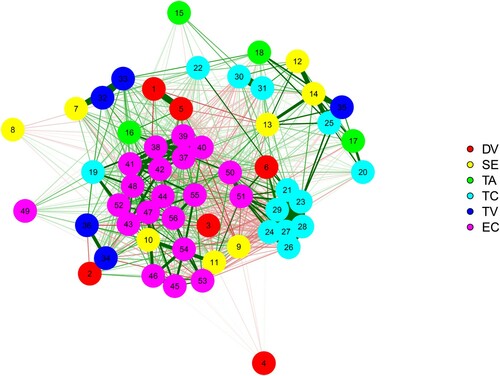

presents the network generated from the correlations between all the items in the six measures (DV, SE, TA, TV, EC, TC). This facilitates the visualisation of how the ecological and interpersonal variables spread around each other depending on the strength of their positive or negative relationships.

Figure 1. Network of ecological and interpersonal factors influencing ECE teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children. Notes: Nodes represent items; edges the empirical correlation between items. Numbers in nodes refer to the order of appearance in the questionnaire. A stronger correlation (positive green: negative red) results in a thicker and darker edge.

Two central clusters and peripheral items can be visualised in the network. Such dynamics are crucial in understanding which ecological (DV and SE) and interpersonal (TA, TV, EC) factors are closer and more central to influencing teacher competences in working with immigrant children (TC), while others have a low impact in occupying more distant positions. Green lines represent positive correlations, red lines negative correlations, and stronger lines represent higher correlations. The criteria used for correlation analysis is r ≥ .05, and not all reported correlations in the graph are statistically significant.

It is crucial to note that half of the TC items (21–29) are strongly correlated to each other, comprising a dense cluster. This reflects how each item is intensely related to others and results in concrete teacher competences in working with immigrant children. In addition, they are in a lateral central position in the global network. The other half of the TC items are mostly dispersed in a peripheral (upper right) position in the network and positively correlate to each other.

Regarding relations between TC and ecological conditions, we can visualise a strong positive correlation between TC items and the DV6 (kindergarten location) indicating that teachers in the city report higher TC. In addition, there is weak positive correlation between the TC cluster and other dispersed TC items mediated by SE13 (‘Ministry of Education provides sufficient support for kindergartens to work with immigrant children’), indicating the relevance of government support among other SE elements. These results are partially consistent with HRA.

Concerning relations between TC and interpersonal skills, the results indicate a strong positive correlation between the TC cluster and two EC items; EC51 (‘When I’m satisfied, I usually do more than I planned’) and EC50 (‘When I’m satisfied, I’m more creative’). Statistically significant positive correlations between the EC and TC clusters are weak to strong (r values are between .10 and .52). On the other side of the network, TC19 (‘In kindergarten, I develop a tolerance and understanding of host country customs and the customs of other cultures’) is strongly correlated to the EC cluster. Other TC items are relatively far from (but still strongly connected to) the TC cluster, and in strong correlation with other TA, TV, and SE items, which indicates that teachers who are more knowledgeable about working with immigrant children (TC25) are also more prone to believing that teaching the child’s primary language should be encouraged (TA17), highly value collaborating with the local community (TV35), and perceive that receiving help from external resources, such as governmental institutions, supports their work with immigrant children (SE35).

The other dense cluster that occupies the central position in the network is EC. This indicates that when all the ecological and interpersonal skills are systematically interrelated, the competences of teachers for perceiving and regulating their own emotions are crucial in supporting teachers’ competences as a whole. Within the EC cluster, SE10 stands out (‘In kindergarten, we work with NGOs to support us in working with immigrants’), together with SE9 and 11, which mediate the EC and TC clusters. Such a close relationship of ecological factors supporting EC and TC indicates that teachers’ potential to work with immigrant children cannot rely exclusively on teachers’ personal resources, such as their emotional, value, and teaching skills, but also depends on contextual elements that support or hinder the teachers’ work.

Finally, closely surrounding the central clusters are most of the TV and TA items, such as TV34 (‘In working with children it is very important to deal equally with everyone. I believe in life everyone should have equal opportunities’) or TA16 (‘Guided activities can always be successfully integrated with immigrant children’). The rest of the items are spread out in isolated clusters across the network.

Discussion

In this study, complementary statistical analyses were used to provide a more comprehensive in-depth understanding of ecological conditions and interpersonal skills leading to ECE teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children. There are several interesting findings for discussion, from which we will focus mainly on two, ecological conditions and interpersonal skills, and their relation to teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children regarding the proposed hypotheses.

Ecological conditions leading to ECE teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children

From the HRA results, years of work experience and job position (as ecological conditions) predict teachers’ competences (TC) in working with immigrant children in the first and second steps, while in the third step (entering interpersonal skills in the analysis), significant predictors are job position, level of education, and location of kindergarten. These results confirm recommendations for quality education in ECE which highlights the importance of staff education level and job position, e.g. at least one qualified staff member in the classroom (Eurydice Citation2009; Urban Citation2009), but it also adds to the literature the relevance of more intensive capacity building for professionals outside city areas.

In addition, the network analysis’ (NA) results show the interdependency of kindergarten location and TC cluster, which indicates that teachers from city kindergartens tend to report higher competences in working with immigrant children than teachers in towns and villages. These results are also compliant with HRA, which revealed that location of kindergarten is significant predictor of teachers’ competences. Teachers from cities report higher competences that teachers in towns and villages (population in cities in Slovenia is between 15.000 and 280.000). Reasons for this might be that teachers in cities are more experienced because they meet more immigrant children, they might have more opportunities for multicultural education, more didactical tools and bilingual children literature, they might have more positive attitudes toward immigrant children and families or might report their competences higher than teachers from villages, but their competences are not necessary so high. However, further research is needed to reveal the reasons for these results. So far, we conclude that teachers’ professional background (job position, level of education, and location of kindergarten) as ecological conditions are significant predictors of teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children.

Further, support from the environment (SE) was positively correlated with reported teachers’ competences (); although the final HRA results in step 3 revealed that this is not to be a significant predictor (), while the results of NA indicated some SE items to be weakly positively correlated with the TC cluster and some SE items moderately correlate with specific TC items. Teachers who perceive more support from governmental institutions (SE14) and supportive behaviour from colleagues toward immigrant children (SE12) report higher competences (e.g. knowledge of different methods to work with immigrant children, TC25; knowledge of legislation and guidelines to work with immigrant children, TC31; and can easily make needed adjustments, TC item 30).

SE as part of ecological conditions is not a statistically significant predictor of reported ECE teachers’ competences in work with immigrant children, although there is a dynamic relationship between SE and TC, shown in the NA. In short, teachers’ potential to work with immigrant children depends on certain ecological conditions as contextual elements that support or hurt teachers’ work; however, the relations are more complex than first thought. We can conclude that SE is a significant predictor of teachers’ competences. Nevertheless, studies show the importance of educational environment support for the development of ECE teacher competences working with immigrant children on the level of institutions, as well as inter-institutional and inter-agency collaboration and support (Urban et al. Citation2012; UNHCR et al. Citation2019; Tobin, Keys Adair, and Arzubiaga Citation2013).

ECE teachers’ perceived interpersonal skills leading to competences in working with immigrant children

HRA results revealed that all three interpersonal skills (TV, EC, TA) perceived by teachers are significant predictors of ECE teachers’ competences in working with immigrant children. Concerning these results, we can confirm that perceived interpersonal skills are significant predictors of reported teacher competences. Results of the network analysis (NA) indicated a more in-depth understanding of the dynamics between interpersonal skills and TC.

Emotional competences, especially the integration of emotions in everyday work (EC50 and 51) are closely positively related to TC in the cluster, largely comprising competences with lower mean values. Other EC items do not seem to be as important (most of the EC cluster has weak negative correlations to the TC cluster), except for TC19 (‘In kindergarten, I develop tolerance and understanding of host country customs and customs of other cultures’). It seems that teachers who perceived themselves as more emotionally competent will be more likely to develop a democratic and tolerant understanding between cultures (TC19) and those who perceive themselves as more able to integrate their emotions into everyday practice will be more likely to successfully overcome the difficulties of working with immigrant families (TC29), prepare alternative activities for immigrant children when they are unable to keep up with the group (TC24), involve the parents of immigrant children in activities (TC27), and use specific methods to work with immigrant children (TC28). These results confirm that emotional competences are part of competences for effective teaching in ECE as they are used in skilful combinations of explicit instructions and the use of specific instructional design and methods, sensitive and warm feedback to children and parents, and verbal and non-verbal interactions (Pianta et al. Citation2009; Ashdown and Bernard Citation2012).

In the NA, reported teacher values (TV) are more in the background regarding positive correlations to TC. Reasons for these results might be in the measurement of the TV construct and/or indirect relations with TC. However, there is one interesting result which indicates that those teachers who value the importance of teaching children honesty and responsibilities (TV33) and who value the importance of caring for the people around them and their well-being (TV34) will more likely use teaching methods to loosen prejudices and stereotypes towards immigrants (TC22). These relations indicate that perceived teacher values are in a dynamic relationship with specific teacher competences and therefore should be considered a vital part of teachers’ interpersonal skills. Being a competent ECE teacher is a continuous process that includes the capability to build on a body of professional knowledge, practice, and to develop and exhibit professional values. Teachers need reflective competences and positive values as they work in highly complex, unpredictable, and diverse contexts (Urban et al. Citation2012).

Perceived positive teacher attitudes (TA) are also positively related to specific TC, but mainly in specific relations between individual items. For example, teachers who report that they believe the use of a child’s primary language should be encouraged (TA17) will more likely have two or more language inscriptions in the classroom and dressing room (TC20) and will more often have sufficient knowledge of different methods for working with immigrant children (TC25). Teachers who believe that teaching the primary (native) and host country languages must be equivalent (TA18) will more likely have a sufficient knowledge of different methods for working with immigrant children (TC25) and more often use methods to loosen prejudices and stereotypes towards immigrants (TC22). Teacher attitudes are in positive relation to teacher competences in work with immigrant children.

Conclusion

When interpreting the results of the present study, some limitations should be considered. We were not able to provide a random sampling procedure, thus resulting in a non-random sample and limiting the generalisability of the results. Further, we can assume a sample bias in a positive direction. It is likely that teachers with more positive attitudes and more competences would decide to participate in the study. All variables were assessed using teachers’ self-report, so we must consider that teacher’s opinions and perceived competences are not their behaviour. Future longitudinal studies could be particularly useful in investigating causal relationships and observing the respective cumulative effects of interpersonal skills on teacher competences. Furthermore, further studies performed in different national environments are needed to confirm the results at an international level. At the core of teachers’ competences is the ability to connect all interpersonal skills, knowledge, teaching methods and resources from the environment. In this research, we focused on several of them, but it needs to be emphasised that in real life they are inseparable. Knowing, doing, and being all come together in professional ECE (Urban et al. Citation2012).

Regarding practical implications of the results, we would suggest that kindergarten management and governmental institutions support ECE teachers in developing competences for working with immigrant children, with special relevance for teachers located in non-city areas, by offering various opportunities for professional development such as educational courses, project work, and collaboration with the local environment (Urban et al. Citation2012). Kindergartens should provide more immigrant children’s literature and didactical tools, more support from interpreters and translators, more support from governmental institutions, and more support from NGOs to support ECE teachers in our sample.

Continuing professional development (CPD) is important argument in how ECE policy should be improved to sustain ECE teacher competences. This can be done with in-service training organised in a comprehensive way, with cultural mediators or pedagogical coaches, with strong mentoring and supervision (Peeters and Sharmahd Citation2014; Pianta et al. Citation2012; EU Council Recommendation Citation2019). This could happen with additional education courses for ECE teachers that should be promoted and implemented by governmental institutions, ECEC networks (e. g. project Wanda), ECE organisations, universities, and NGOs, which can develop a »competent system« support (Urban et al. Citation2012). CPD can be also promoted with the exchange of experiences and good practices of peer learning between ECE teachers (Peeters and Vandenbroeck Citation2011). Pre- and in-service training should include development of ECE teachers’ interpersonal skills to improve their capacity in daily work; for example, empathy, understanding of others, flexibility in emotional response, showing positive emotions toward immigrant children and families, having open mind, being non-judgmental, being flexible, being able to accept diversity and respecting other ways of being (ISSA Citation2011; Peeters and Vandenbroeck Citation2011). At the core of teachers’ competences is the ability to connect all interpersonal skills, knowledge, teaching methods and resources from the environment in the ever-challenging and unpredictable multicultural education (Portera Citation2014).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbott, M. L. 2016. Using Statistics in the Social and Health Sciences with SPSS and Excel. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Ashdown, Daniela Maree, and Michael E. Bernard. 2012. “Can Explicit Instruction in Social and Emotional Learning Skills Benefit the Social-Emotional Development, Well-being, and Academic Achievement of Young Children.” Early Childhood Education Journal 39: 397–405.

- Atiles, Julia Teresa, Jonathan Robert Douglas, and Martha Allexsaht-Snider. 2017. “Early Childhood Teachers’ Efficacy in the U. S. Rural Midwest: Teaching Culturally Diverse Learners.” Journal for Multicultural Education 11 (2): 119–130.

- Block, Karen, Suzanne Cross, Elisha Riggs, and Lisa Gibbs. 2014. “Supporting Schools to Create an Inclusive Environment for Refugee Students.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (12): 1337–1355.

- Chan, Angel. 2011. “Critical Multiculturalism: Supporting Early Childhood Teachers to Work with Diverse Immigrant Families.” International Research in Early Childhood Education 2 (1): 63–75.

- Chan, Angel, and Jenny Ritchie. 2019. “Critical Pedagogies of Place: Some Considerations for Early Childhood Care and Education in a Superdiverse »Bicultural« Aotearoa (New Zealand).” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 10 (1): 51–73.

- Cortina, Jose M. 1993. “What is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications.” Journal of Applied Psychology 78 (1): 98–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98.

- Epskamp, Sacha, Angelique O. J. Cramer, Lourens J. Waldorp, Verena D. Schmittmann, and Denny Borsboom. 2012. “Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data.” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (4): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04.

- EU Council Recommendation. 2019. “Council Recommendations of 22 May 2019 on High-Quality Early Childhood Education and Care Systems.” Official Journal of the European Union, 2019/C vol. 189/2. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.C_.2019.189.01.0004.01.ENG.

- Eurydice. 2009. Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe: Tackling Social and Cultural Inequalities. Brussels: Eurydice.

- Firstater, Esther, Laura I. Sigad, and Tanya Frankel. 2015. “The Experiences of Israeli Early Childhood Educators Working With Children of Ethiopian Background. Sage Open.” July-September 5 (3): 1–9.

- Gandara, Patricia, and Frances Contreras. 2009. The Latino Educational Crisis: The Consequences of Failed Social Policies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Genishi, Celia, and Anne Haas Dyson. 2009. Children, Language and Literacy: Diverse Learners in Diverse Times. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Griethuijsen, Ralf A. L. F., Michiel W. van Eijck, Helen Haste, Perry J. den Brok, Nigel C. Skinner, Nasser Mansour, Ayse Savran Gencer, and Saouma BouJaoude. 2014. “Global Patterns in Students’ Views of Science and Interest in Science.” Research in Science Education 45 (4): 581–603.

- Iddings, da Silva Ana Christina, and Iliana Reyes. 2017. “Learning with Immigrant Children, Families and Communities: The Imperative of Early Childhood Teacher Education.” Early Years 37 (1): 34–46.

- ISSA. 2011. Diversity and Social Inclusion. Exploring Competences for Professional Practice in ECEC. Brussels: DECET and ISSA. Retrieved in March from https://www.issa.nl/sites/default/files/pdf/Publications/equity/Diversity-and-Social-Inclusion_0.pdf.

- Jahng, Kyung Eun. 2014. “A Self-critical Journey to Working for Immigrant Children: an Autoethnography.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (4): 573–582.

- Janta, Barbara, and Emma Harte. 2016. Education of Migrant Children. Education Policy Responses for the Inclusion of Migrant Children in Europe. Cambridge: RAND Corporation.

- Jerlean, Daniel, and Susan Friedman. 2005. “Taking the Next Step: Preparing Teachers to Work with Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Children.” Embracing Diversity 11 (1): 1–7. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238743013_Preparing_Teachers_to_Work_with_Culturally_and_Linguistically_Diverse_Children.

- Katrien, Van Laere, and Michel Vandenbroeck. 2017. “Early Learning in Preschool: Meaningful and Inclusive for All? Exploring Perspectives of Migrant Parents and Staff.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (1): 243–257.

- Keys Adair, Jennifer. 2011. “Confirming Chanclas: What Early Childhood Teacher Educators Can Learn from Immigrant Teachers.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 32 (1): 55–71.

- Keys Adair, Jennifer. 2012. “Discrimination as a Contextualized Obstacle to the Preschool Teaching of Young Latino Children of Immigrants.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 13 (3): 163–174.

- Lazzari, Arriana, Lucia Balduzzi, Katrien Van Laere, Caroline Boudry, Mateja Rezek, and Angela Prodger. 2020. “Sustaining Warm and Inclusive Transitions Across the Early Years: Insights from the START Project.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (1): 43–57.

- Licardo, Marta. 2020a. “Dataset for Article Ecological Conditions and Interpersonal Skills Leading to ECE Teachers Competences in Working with Immigrant Children.” Accessed December 12 2020. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Article_Ecological_conditions_and_interpersonal_skills_leading_to_ECE_teachers_competences_in_working_with_immigrant_children_xlsx_codebook_database_/13498653?file=25911333.

- Licardo, Marta. 2020. “Implementing Good Practices with Migrant Children in Preschool Education in Slovenia.” In Clicked: Culture, Language, Inclusion, Competencies, Knowledge, Education: Diverse Approaches and National Perspectives in the Field of Primary and pre-Primary Education, edited by Kissne Zsamboki Reka, 57–68. Sopron: University Press, University of Sopron.

- Matthews, Hannah, Rebeca Ulrich, and Weny Cervantes. 2018. Immigration Policy’s Harmful Impacts on Early Care and Education. Washington, DC: The Center for Law and Social Policy.

- McDevitt, Seung Eun. 2020. “Teaching Immigrant Children: Learning from Experiences of Immigrant Early Childhood Teachers.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 42 (2): 123–142.. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2020.1818650.

- Moin, Victor, Mila Schwartz, and Anna Breitkopf. 2011. “Balancing Between Heritage and Host Languages in Bilingual Kindergarten: Viewpoints of Russian-Speaking Immigrant Parents in Germany and in Israel.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 19 (4): 515–533.

- Onchwari, Grace, Jacqueline Onchwari Ariri, and Jared Keengwe. 2008. “Teaching the Immigrant Child: Application of Child Development Theories.” Early Childhood Education Journal 36: 267–273.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, Veronica, and Ana-Elisa Armstrong de Almeida. 2006. “Language Discourses and Ideologies at the Heart of Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 9 (3): 310–341.

- Peeters, Jan, and Nima Sharmahd. 2014. “Professional Development for ECEC Practitioners with Responsibilities for Children at Risk: Which Competences and In-Service Training are Needed?” Early Childhood Education Journal 22: 412–424.

- Peeters, J., and M. Vandenbroeck. 2011. “Child Care Practitioners and the Process of Professionalization.” In Professionalization and Management in the Early Years, edited by L. Miller and C. Cable, 62–74. London: Sage.

- Pianta, Rober C., Michael S. Steinberg, and Kristin Rollins. 1995. “The First Two Years of School: Teacher-Child Relationships and Deflections in Children’s Classroom Adjustment.” Development in Psychopathology 7: 295–312.

- Pianta, Robert C., W. Steven Barnett, Margaret Burchinal, and Kathy R. Thornburg. 2009. “The Effects of Preschool Education: What We Know, How Public Policy Is or Is Not Aligned With the Evidence Base, and What We Need to Know.” Psychological Science and the Public Interest 10 (2): 49–88.

- Pianta, Robert C., W. Steven Barnett, L. M. Justice, and S. M. Sheridan. 2012. Handbook of Early Childhood Education. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Portera, Agostino. 2014. “Intercultural Competence in Education, Counselling and Psychotherapy.” Intercultural Education 25 (2): 157–174.

- Ray, Aisha, and Barbara Bowman. 2003. Learning Multicultural Competence: Developing Early Childhood Practitioners’ Effectiveness in Working with Children from Culturally Diverse Communities. Final Report to the A. L. Mailman Family Foundation. Initiative on Race, Class and Culture in Early Childhood. Chicago: Erikson Institute.

- Schmittmann, Verena D., Angelique O. J. Cramer, Lourens J. Waldorp, Sacha Epskamp, Rogier A. Kievit, and Danny Borsboom. 2013. “Deconstructing the Construct: A Network Perspective on Psychological Phenomena.” New Ideas in Psychology 31 (1): 43–53.

- Souto-Manning, Mariana. 2007. “Immigrant Families and Children (Re)Develop Identities in a New Context.” Early Childhood Education Journal 34 (6): 399–405.

- Taber, Keith S. 2017. “The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education.” Research in Science Education 48: 1273–1296.

- Tobin, Joseph. 2020. “Addressing the Needs of Children of Immigrants and Refugee Families in Contemporary ECEC Settings: Findings and Implications from the Children Crossing Borders Study.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (1): 10–20.

- Tobin, Joseph Jay, Jennifer Keys Adair, and Angela Arzubiaga. 2013. Children Crossing Borders: Immigrant Parent and Teacher Perspectives on Preschool. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

- UNESCO. 2018. Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM. 2019. “Access to Education for Refugee and Migrant Children in Europe.” Accessed November 20. https://www.unhcr.org/neu/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/09/Access-to-education-europe-19.pdf.

- Urban, Mathias. 2009. Early Childhood Education in Europe. Achievements, Challenges and Possibilities. Brussels: Education International.

- Urban, Mathias, Michel Vandenbroeck, Arriana Lazzari, Katrien Van Laere, and Jan Peeters. 2012. Competence Requirements in Early Childhood Education and Care. Final report. European Commission: University of East London and University of Ghent.