Abstract

This article explores the significance of students’ encounters with materiality in general and with crafting materials in particular when learning for sustainability. The aim of the explorative study is to illustrate a research approach that can show what students and the material do in correspondence and what stories emerge from this activity. An explorative analysis is conducted via video recordings of a remake project in a Grade 8 handicrafts class in Sweden. The stories that the students recognise are the material’s texture, shape and construction, which emerge from the materiality intrinsic to the crafting process and the intentions of the students, as these are visible in action. These stories provide possibilities, as well as set limits for, what is possible to remake. The stories are elaborated on by threading back to materiality concerns found in historical remake practice to recognise the educational possibilities for remaking pedagogy.

Introduction

As a reaction against the neglecting of materials and how matter matters (Barad Citation2003), the turn to materiality in research (Coole and Frost Citation2010) is concerned with decentralising the human subject among materials (Fenwick Citation2015; Sørensen Citation2009). In environmental and sustainability education research (ESER), questions about how materials have come to matter have intensified in the last decade due not only to the materiality turn but also to the call for lifestyle re-orientations in the ‘expansion of mankind’ age – the Anthropocene (Crutzen and Stoermer Citation2000; Steffen et al. Citation2015). At the core of these ESER discussions about how materials matter is a concern to find other ways of knowing and understanding the entanglements of how materials and humans live and learn together to engage with environmental and sustainability issues (see for example Clarke and Mcphie Citation2016; Lloro-Bidart Citation2017; Mannion Citation2007; Payne Citation2016; McKenzie and Bieler Citation2016; Pyyry Citation2017; Russell Citation2005; Rautio Citation2013; Rautio et al. Citation2017; Somerville Citation2016, Taylor Citation2017; Van Poeck and Lysgaard Citation2016). In this article, I seek to contribute to this scholarly discussion with an explorative study about the significance of students encountering materiality in general and crafting material in particular in conjunction with the students’ learning for sustainability. The case in focus for this study is a school project in Sweden in which students were given the task to remake old clothes into new products.

The reason for exploring a remake project with textiles is that such projects are common recycling activities in environmental and sustainability education (ESE) and seen by policy makers as setting an example for how one can save resources (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011, 203). In fact, in Sweden today, eight kilograms of textiles per person contribute to household waste each year (SMED Citation2011, 6); thus, remaking projects are often seen as relevant for ESE. Despite that remaking activity is common in education, usually as part of the Swedish handicrafts subject, ‘educational sloyd’, research into remaking activities is limited. However, related research focusing on remaking activities in ESE does exist. For example, Danish scholars studied waste activities in ESE and found that teachers are using ‘artistic activities as an entry point for dealing with waste’ (Jørgensen, Madsen, and Læssøe Citation2018, 810). Some of the interviewed Danish teachers expressed that working with ‘reusable materials support children’s fantasy, ingenuity and creativity’ (811). Another example is Odegard (Citation2012), who studied how preschool children encounter ‘junk’ materials in remaking activities by analysing focus group conversations with preschool teachers. In the group conversation, the teachers brought with them pedagogical documentation of the activities, such as photos and texts. Odegard focused on how materials are recognised and emerge in what is referred to as ‘intra-activity’ (Barad Citation2007). Based on her findings, Odegard argues that when the children encounter the materials, the materials are ‘undefined’, which she further argues provides ‘an articulation that emphasises their [the material’s] properties rather than their uses’ (387). However, she continues to explain that how the children worked with the materials was, to a large extent, ‘dependant on the teachers’ expectations of an upcoming product’ (398), thus showing the importance of remaking pedagogy. One final example of a remaking project is from South Africa, where McGarry (Citation2013) co-created artwork together with five young men who were engaged with informal waste collection from local landfills. In the project, the waste was used to make puppets and the puppets were used to explore the participants ‘perceptions of personal and social progress, essentially how they could improve their situations with their existing means, and look at what way these means/abilities could be further enriched or developed’ (112). For the participants, working with waste in new ways resulted in changes, even though, as McGarry concludes, it was hard to see what specific practices, instruments or processes led to the changes or ‘where learning was taking place’ (p. 113). These examples from Denmark, Norway and South Africa show the potential of remake projects in ESE. However, observations of students’ encounters with the material in remake projects has not been explored, and this area is in need of empirical research. Of relevance to this article is that there is limited knowledge about students’ encounters with materiality, and further, about how these human–material encounters can contribute to a remake pedagogy, which could further motivate empirical research of student–material encounters in remake activities.

To contribute to the scholarly discussion of the significance of students encountering materiality in general and crafting material in particular, this explorative study aims to illustrate a research approach inspired by Ingold’s theory of making. This aim is addressed by asking the following empirical questions:

What functions does the material have for students when learning to remake?

What stories about human–material relations are created when students encounter the material in the remake activity?

In the students’ remaking activity, does a conjunction of the present and the past emerge between the stories created and the historical practice of remaking? And if so, how could this be used to further develop students’ remaking skills in relation to sustainability?

The outline of the paper is as follows: First, Ingold’s (Citation2011, Citation2013) concepts of ‘practice of correspondence’ and ‘storying’ are presented. These concepts helped me identify student–material encounters in crafting activities and the embodied stories that emerged from these correspondences. Thereafter, the case of the remake project is presented along with the selection of the empirical data. Then four illustrative examples of the correspondence between students and the material and what stories that emerge from these correspondences are presented. This third section gives an account of how the first and the second research questions are answered. Fourthly, the illustrative examples are discussed as materiality concerns found in historical remake practice, thus answering the third research question. Lastly, how the research approach can create new knowledge fruitful for remake activities and remake pedagogy are discussed.

A theory of crafting: human–material correspondence

Crafting is all about making things – transforming material into new forms and functions – and one can easily get the idea that the craft activity starts with an idea about what one wants to achieve, followed by imposing a form on the material ‘out there’ (Ingold Citation2013, 20). In this article, I follow Ingold’s (Citation2011, Citation2013) understanding of making, which suggests something different, namely, that humans do not act upon the world but rather act from within in what Ingold describes as ‘a process of growth’ (2013, 21). He continues,

This is to place the maker from the outset as a participant in amongst a world of active materials. These materials are what he has to work with, and in the process of making he ‘joins forces’ with them, bringing them together or splitting them apart, synthesising and distilling, in anticipation of what might emerge. (ibid.)

Hence, Ingold argues that, in crafting activities, a craftperson joins forces with the material, and this process is what Ingold (Citation2013) refers to as a ‘practice of correspondence’ (108). This contrasts with a process of interaction, which Ingold describes as two closed parties that connect ‘through some kind of bridging operation’ (107). In a practice of correspondence, people are already set in relation to the materiality of the world. To correspond with the world, Ingold argues, ‘is not to describe it, or to represent it, but to answer to it’ (108). From a crafting perspective, this means that learning occurs when we answer to the world and join forces with the material in a new way, and in doing so, engage in new correspondences with the material. In the article, I explore these student–material encounters in the crafting activity. In the exploration, I do not consider that students act upon passive materials, but rather, in the crafting process, students join forces with the materials as they answer to them in a practice of correspondence.

As students learn to answer to the material in correspondence, the material or the tools are not separated from the crafting activity. Instead, as Ingold (Citation2011) argues, ‘The entire system of forces and relations set up by the intimate engagement of the saw, the trestle, the workpiece and my own body’ (56), where the system and the forces are perceived as the activity. This means that a material or tool has no intrinsic attributes. But, as Ingold continues, ‘To describe a thing as a tool is to place it in relation to other things within a field of activity in which it can exert a certain effect’ (ibid.). Hence, a tool or a material is always known in relation to other things within an activity. To understand the meaning-making process that emerges from a specific practice (i.e. a system of forces), Ingold uses the concept of ‘stories’. He explains that a tool ‘must be endowed with a story, which the practitioner should know and understand in order to recognise it as such and use it appropriately’ (ibid.). Ingold goes even further when he states that ‘considered as tools, things are their stories’ (ibid). These stories should be understood as creating a continuation between the past practice (history), the current practice (the present) and the purpose or task in terms of the excepted outcome (future). Ingold (Citation2011) further explains,

Just as stories do not carry their meanings ready-made into the world so, likewise, the ways in which the tools are to be used do not come pre-packaged with the tools themselves. But neither are the uses of tools simply invented on the spot, without regard to any history of the past practice. Rather, they are revealed to practitioners when, faced with a recurrent task in which the same devices were known previously to have been employed, they are perceived to afford the wherewithal for its accomplishment. Thus, the functions of tools, like the meaning of stories, are recognised through the alignment of present circumstances with the conjunctions of the past. Once recognised, these functions provide the practitioner with the means to keep on going. (57)

In other words, Ingold argues that a specific meaning is neither fixed in, nor imposed on, a tool but rather emerges as a co-creating process recognised through the circumstances of the present (which has a specific purpose) in conjunction with the past within this specific practice. However, the story that emerges in conjunction with the past should not be understood as embedded in a static and closed tradition because what is being recontextualised and recognised is not pre-determined, but rather it emerges in the practice of correspondence. Arguably, the contextualisation process of continuity and change (in terms of time in the past, time in the future, and the present/place) is key to pedagogy, as it affects what stories will emerge.

In the article, I explore a remake project that is carried out in the Swedish craft subject, educational sloyd. The crafting materials that the students answer to and join forces with in the remaking activity are set in a ‘system of forces’ with the aim to be remade. However, remaking clothes are by no means a new activity; throughout history, clothes were seldom thrown away. More commonly, clothes are inherited, reused, mended and resewn (Palmsköld Citation2013, 76); for example, larger garments were unstitched, washed and remade into new products and smaller garments were made into clothes for children (Resare Citation2002, 273). Even the smallest bit of fabric was often saved and reused as decoration such as the fringe on pillow corners (Palmsköld Citation2013, 82). Further, if the garments were not remade into other clothes, they were cut and used for rag rugs or as patchwork (Franow Citation2002, 274). These examples illustrate that clothes were remade into other objects, and this activity has both functional and aesthetic values in the remaking practice, and accordingly, the stories about the material were recognised as such. In addition, to be able to recognise worn-out clothes as something that can be remade, crafting skills (for example, how to darn socks or patch clothes) are needed. It could be argued that a remaking activity carried out in Sweden today could potentially have historical ‘threads’ to a remaking practice. The connection occurs if the story that is told has an alignment or an affinity to the stories that were produced in older practices, in other words, when the material is recognised through the alignment of present circumstances in conjunction with the past (Ingold Citation2011, 57). But, importantly, as mentioned, these stories are never pre-determined but rather emerge as a practice of correspondence.

In the analysis of the remake project, I first use Ingold’s concept of the practice of correspondence to explore the student–material encounters and how they evolve in the remaking activity. When I identify the correspondences in the analysis, I explore what functions the material have as the students answer to the material in correspondence (question 1). Second, I explore what stories emerge from this activity. Analytically, how the student tells these stories is considered not only as a verbal story but also an embodied activity. Here, I follow Ingold as he argues that ‘to tell’ refers to, on the one hand, being able to recount stories of the world, and on the other hand, being able to recognise subtle cues in one’s environment and respond to them with judgement and precision (Ingold Citation2013, 109–110). By using stories as an analytical concept in the remake activity, I contend that we need to have a story for learning to emerge – in this case, a story about and with the remake material. Hence, the question that becomes relevant to explore asks what stories emerge (question 2). As the remake activities have historical threads to a remake practice (i.e. a conjunction with the past), in the third step of the analysis, I also explore if any conjunctions exist between the stories that have been created in students’ remaking activities and historical remaking activities. And if so, I explore how these conjunctions could be used to further develop students’ remaking skills in relation to sustainability (question 3). To highlight this connection between the past and the future in the remake activity, I will define this connection with history as ‘threading back’ and its connection with the future as ‘threading forward’. I do this to discuss pedagogical opportunities as students learn for sustainability.

The remake project, data selection and data analysis

The project was carried out in the Swedish handicrafts subject called educational Sloyd, which, in Sweden, is a mandatory school subject in Grades 3–9. In the curriculum, it is stated that students should be given ‘opportunities to develop knowledge of how to choose and handle materials in order to promote sustainable development’ (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011, 203), and as a respond to this statement, remaking projects are common. This particular remake project was observed by using video recordings of a Grade 8 class. The task for the students was to make a new product from used garments by using a sewing machine. The class was composed of 15 students, and the raw data amounted to about 20 h of film distributed over a period of 10 weeks (i.e. 80 minutes per week). Two cameras were used: one was attached to the teacher’s body and the other was held and operated by the researcher. In an earlier study of the same empirical material in the remake project, I identified how the students had to ‘transact’ with ideas for future products, with the crafting materials’ capabilities, and with the crafting techniques (reference to author). In the present article, I focus on the human–material relations and what sustainability stories emerge from the correspondence.

I found two activities particularly relevant for my analysis, as they made the human–material correspondence visible. The first activity was when the students were deciding on the design of the remaking project (i.e. what to do, which material to use, or the character of the imagined end-product), and the second activity was when the students were trying to realise the design through crafting. Taken together, it was possible to see from the empirical video data how six of the students (three boys and three girls) were in a decision-making process of what to remake. Given this visibility, these six students’ decision-making processes were targeted for further analysis in the first activity. In the second activity, in which the students realise their imagined product, there were many human–material correspondences. To scope the human–material correspondences, I decided to follow four students who were all remaking jeans. This means that I did not consider any lecturing by the teacher (for example, about how to make a paper pattern) or when the students write descriptions of their imagined process if the remake material was not part of the process.

The analysis was conducted in three steps. In the first step, I watched the selected passages and identified the correspondence between the student and the remake material. For example, if a student remade a pair of jeans into a pillow, I noted how the correspondence developed as the design of a pillow emerged. In the second step, the stories that the student recognised in the design process are identified, which emerge from the materiality intrinsic to the crafting process and the intentions of the students, as these are visible in action. For example, if the form of the jeans is recognised by the students, and the form is what students use when making a pillow, the form is identified as a story. In the third step, the constructed data from the correspondences and stories are discussed in relation to historical remake practice (i.e. in conjunction with the past). By taking a materiality focus on the remake practice, I ‘thread back’ and ‘thread forward’ to discuss pedagogical opportunities as students learn for sustainability.

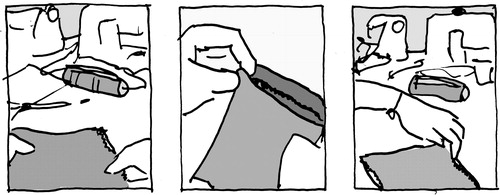

To present the findings, I first give four examples from the correspondences by presenting excerpts and descriptions from the video data. I have also added sketches from screenshots to provide a better understanding for the situation. The reason for choosing both excerpts and descriptions is due to the character of the activity. Often, if the activity did not contain much verbal dialogue, then descriptions are used. In one example with Jonas, the verbal dialogue between the teacher and the student was quite long, and therefore, the excerpts made the dialogue more transparent. The excerpts and descriptions were translated from the video recordings into written text, focusing on approximating a literal translation (Linell Citation1994, 11), which means that what happens in the activity needs to be visible to the reader, and the transcript must be legible. In these presentations, I pay special attention to both the student and the recycled material. On one hand, translating an embodied activity into a text has limitations, as it will likely lose some complexity. On the other hand, the simplification of an activity also provides an opportunity to highlight something more clearly, in this case, the encounter between the student and the remake material.

Two illustrations of creating a design in correspondence with the material

In the first example, we meet two students, Clair and Oliver, as they choose what to remake; and in the process of choosing, they create a design in correspondence with the material. In the following text, I first describe the two activities and then discuss the correspondences and the stories that emerge from the correspondences.

Clair starts by saying, ‘I think I will make a pillow’ (151110, 001MTS, 4:28). She holds up a pair of jeans, looks at them and then puts them aside. She then starts to touch and pat a piece of fake fur and a dress made of lace. After a while, she makes a heart shape with her fingers on the fake fur (6:36). She then starts to sketch a pillow on her working instruction paper to illustrate her design. After a while, she speaks up loudly, ‘I do not know how to draw a pillow’ (7:28), but no one answers and she continues to draw on the paper with her pencil. Then she picks up the lace dress, makes it lie flat on the table, and with her arms, measures a square to see what it looks like (8:14). Then she takes the fake fur and puts it on the dress and makes a square again with her underarms (8:23) as she continues to draw and write down her ideas ().

The student next to Clair, Oliver, sits with his pair of jeans in front of him and decides to make a pillow using the jeans. Clair asks how he is going to design them (9.26). Oliver responds, ‘Yeah, I could make it a big pillow where I will have the upper part here’, pointing to the back of his shoulder, and the two legs could come down on each side, which he shows by pointing with his hands (9:31). Clair laughs. Everyone at the table starts to give suggestions on how he could do it. However, Oliver concludes that he will make a pair of shorts instead because that seems much easier to do (10:10) ().

If we look at the correspondences in the described passage from the beginning of the lesson, Clair says that she wants to make a pillow. Why Clair wants to make a pillow is not possible to know from the excerpt, but she clearly has not yet decided how this pillow will look. Here, the correspondence emerges from the point where Clair feels the garments with her hands as she pats them and her fingers make a shape of a heart at the fabric. She is also corresponding with the lace dress by using her arms to imagine how big the pillow should be. These correspondences help her design her remaking product. The story about the material that emerges from these correspondences is the texture of the fabric because she continuously uses her hand to feel the fur and the lace as she is designing the pillow.

From the second example, we see Oliver starting to imagine how he can make a pillow. He describes to his fellow students how the jeans could be put around his shoulders with the jeans’ legs coming down on each side. The correspondence here starts with the shape of the jeans, which Oliver corresponds with and, arguably, it is the shape and how the jeans are constructed that prompt Oliver to imagine a possible design. In other words, it is the shape and the construction of the jeans that Oliver recognises and thus emerge as part of the story when Oliver imagines what to remake, although, in the end, he gives up this design and chooses another idea instead.

Two illustrations of how to realise the design in correspondence with the material

When students have decided what to do and try to come up with a solution for how to make the design, resistance often arises. What is interesting here is that the resistance does not necessarily emerge from interpersonal student–student or student–teacher relations but rather from the entanglements intrinsic to the material in the crafting process, where the intentions of individuals are sometimes blocked or resisted by the chosen material. In the following, I give two examples of when students handle the material differently when corresponding with it. I first describe the two activities and then discuss the correspondences and the stories that emerge from these correspondences.

First, we meet Jonas. When the teacher arrives at his desk, Jonas explains that he wants to keep the original shape of the jeans and make a pillow that is 35 × 40 cm, but he does not know how to realise his design (151110: GPO10344:0.29). The teacher and the students begin discussing, and the conversation ends with the teacher asking Jonas to solve how to realise his design and make a pattern according to his design (1:50). For a long time, Jonas sits at his desk with the jeans in front of him, measuring the jeans over and over again by using a measuring tape in his effort to make the design. When the teacher arrives the next time, Jonas has decided to simplify the product, and the design has now changed into a rectangular pillowcase. He has decided to cut off one of the legs and make a pillowcase out of it. However, referring to the assessment, the teacher thinks that this idea is too simple and asks Jonas to come up with another solution (15:53). So Jonas continues to measure the jeans. The teacher approaches him a third time, and they have the following exchange ():

Jonas: There is something wrong with the jeans. They are wider here than there [points to the jeans].

They are wider here than there [points to the paper pattern] (15:41–15: 50).

The teacher explains that this is exactly what Jonas needs to deal with; that is, he needs to come up with a solution for how to reuse the jeans. When the teacher approaches him a fourth time, Jonas has decided to return to the initial idea of making a square pillow, and the conversation proceeds as follows:

Teacher: Are you still using these [points to the jeans]?

Jonas: Yes, I am, and I’ll use both legs.

Teacher: There’ll be a seam somewhere, won’t there?

Jonas: Yes, but it is diagonal, like that [points to the paper pattern].

Teacher: Is that your intention?

Jonas: Yes, like that [points to the paper pattern again].

Teacher: Yes, okay. Is it the same at the back?

Jonas: Hmm. Should I measure it? … when I make that one, should I measure it like a square?

like that… so that it’s forty, forty, forty, forty [points to each side of the paper] …

so that it is [Jonas draws a square in the air with his finger] … and then cut it.

Teacher: Yes, and if you do that, you’ll be able to get a higher grade, which will be good (151110: GP020344: 5.30–6.14).

In a second example of how a student handles the material, we meet Anna, who is about to make a small toilet bag out of pair of jeans. When making the design, she measures the jeans, makes a pattern, and then cuts the jeans accordingly. When we meet her, Anna has the jeans in front of her and asks the teacher if she should zigzag the edges first, as she normally would do. (GP020351.MP4 151201 3:58). Now, resistance emerges. According to Anna’s plan, she wants to use a zipper, but to use a zipper, a seam allowance is needed, otherwise it is not possible to attach the zipper. Anna has the pieces of jeans in front of her, where the sides are sewn together. Here she realises that it will not be possible to attach the zipper, as there is not enough fabric for the seam allowance. The teacher, who stands next to her, responds that she had not realised that Anna wants to use a zipper. Anna is silent for quite some time. The jeans are lying there in front of her. They are already cut, and she does not know what to do. After a while, Anna says that she will not use a zipper because the zipper, if sewn with the required seam allowance, will make the toilet bag too small. She decides to simplify the construction and use a button and a loop of yarn to make it possible to close the bag (6:27) ().

I have described two passages where the students have decided what to do and then continued to work. In both examples, the students are joining forces or trying to join forces with the material in a practice of correspondence. These correspondences will now be in focus ().

In the first example, Jonas had decided to make a pillow, but realising that idea proves to be quite hard. If we look at the correspondences here, the jeans are in front of him and Jonas measures the jeans several times. In this correspondence, the jeans are clearly troubling Jonas, as he cannot come up with a solution. Instead, he suggests simplifying the imagined product by making a rectangular pillow, but the teacher asks him to come up with another solution. As Jonas is corresponding with the material, he utters that there is something wrong with the jeans (line 1). The shape of the jeans is wider on the upper side compared to the lower side, which is something that Jonas recognises as he measures the jeans, and this correspondence creates specific limitations, as Jonas is about to come up with a solution. From the excerpt, it is also possible to see that the correspondence is not solely a cognitive process. When the teacher asks Jonas for his new solution, Jonas replies by first pointing to the paper where he has drawn the sketch of the pillowcase (line 8) and then continues to explain his idea by drawing a square in the air with his finger (lines 10–12). Thus, he uses his body to show (and perhaps also to develop) his ideas. The story about the material that emerges in this activity is the shape of the jeans. The shape provides limitations and makes Jonas doubt his first idea to make a square pillow. However, by continuing to correspond with the shape and the construction of the jeans (using both legs), these entanglements make it possible for Jonas to realise the final design, thus allowing him to continue with the remake activity.

We now turn to the correspondences in the second example, with Anna working on her toilet bag. Anna has measured the jeans and cut them, but unfortunately, they are cut too small to include a zipper. Here, Anna is forced to adjust her design to the available fabric. Instead of a zipper, Anna imagines using a button to realise the product. Here, the story that emerges from this example is a story of construction and the miscalculation of the jeans’ form, which causes Anna to simplify her imagined product.

Stories of sustainability in remaking practices as a pedagogical opportunity

In the previous section, I illustrate the student–material encounters and how the correspondences evolve in the remaking activity, and by doing that, I explore what functions the material has as the students join forces with the material and answer to the material in correspondence (question 1). Furthermore, I identify three stories that the students recognise about the material (question 2), namely, the texture, the shape or form, and the construction. By providing a research approach that acknowledges the correspondence between the human and the material, I have sought to show the reciprocal correspondence between the human and the material, and this is highly important for what stories are possible to learn in remaking activities. These stories – the material’s texture, shape and construction – are what the students recognised as they learnt to join forces with the material and answer to the material in the remake project. The curriculum states that students should be given the opportunity ‘to develop knowledge of how to choose and handle materials in order to promote sustainable development’ (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011, 203), and arguably, this occurs in the examples, given the embodied experience of the material’s texture, shape and construction, which the students learn to recognise as they promote sustainable development.

The question that remains is whether there are any conjunctions between these three stories and historical remaking activities (question 3). If one is to ‘thread back’ in conjunction with the past (Ingold Citation2011), I would argue that these examples of how the material is recognised have a bearing on the Swedish historical remaking practice. For example, historically, when remaking clothes, the craftsperson would have had to answer to the material and encounter the texture, as well as determine the product’s shape and construction, as these are inevitable when remaking. However, how these stories were told, for example, with economic, social or ecological means, are likely to differ, as the activities are set in another time and context. Nevertheless, there is a link here, which I argue can be used in a remake pedagogy. My point is that by acknowledging historical threads in a remake activity, the activity can be regarded as having pedagogical opportunities that take departure from the students’ own correspondences with the material. In addition to these three stories that the students recognise, I want to mention three complementary materiality concerns that threading back provides.

The first materiality concern is knowing the source. In the past, recycling fabrics and making a virtue of necessity was something you had to do when you could not buy everything you needed (Hallén Citation2002, 274). When making a virtue of necessity, knowing about the source was helpful in this remaking practice. By source, I mean what the garments are made of, for example, cotton, linen, wool or leather (and today it also concerns types of plastic material such as polyester or acrylic). What the material is made out of is particularly important if the garments are meant to be remade into new products, as that will affect what is possible to remake. Not only that, but by knowing the source, one will also, in correspondence with the material, know what to expect from the material and how to take care of the material. That is not to say that the correspondence is predetermined but rather, based on previous knowledge of human–material relations, one can know what is likely to happen. For example, knowing how wool fibres or viscose fibres perform when they are wet (wool fibres are cleansing, and viscous fibres break easily) could help students expand their possible actions in remaking activities. Knowing about the source is also about recognising and developing an understanding of how fibres feel when squeezing them (for example, what natural fibres feel like compared to plastic fibres). The second materiality concern is knowing about the fabric. When mending garments, knowing about the fabric – that is, whether it is woven, knitted or felted – is helpful, as the techniques of these human–material correspondences are not the same. That is, a pair of jeans woven in twill are mended with specific techniques and a specific needle so that the needle or the thread does not break. When mending a knitted fabric (for example, a t-shirt or a sweater), the correspondence of the human–material differs in that the fabric is made from loops and needs to be repaired accordingly. The third materiality concern is to use every piece of the garment, which historically would have been common practice (Palmsköld Citation2013, 74). What this materiality concern gives us is a story of zero waste, which provides attention to all parts of the garments, as the smallest pieces of fabric were saved and used for decoration (Palmsköld Citation2013, 82). These three materiality concerns – the source, the fabric and zero waste – create potentially relevant additions to the stories that the students make as they learn for sustainability in a remake activity that is understood as part of a larger remaking practice. In other words, the conjunctions with the past provide pedagogical opportunities that the teacher can consider as the students are remaking for sustainability.

Discussion

We know from previous research that arts and crafts activities involving recycling are promising, as they can create new ways of supporting children’s imagination, ingenuity and creativity (Jørgensen, Madsen, and Læssøe Citation2018, 811) as well as be a way to recognise a material’s properties (Odegard Citation2012, 387) and act as a springboard for working with personal and social change (McGarry Citation2013, 110–112). My study adds to this research, as it explores and illustrates students’ encounters with crafting material. Therefore, I expand on what it might mean to be creative in a remake activity (Jørgensen, Madsen, and Læssøe Citation2018) or what it means to recognise and experience a material’s properties (Odegard Citation2012). For example, in the remake activity, the students needed to decide what to remake and come up with solutions for how to remake the products, which resulted in a creative process where the students created a design in correspondence with the material. Thus, by applying a specific research approach, I have been able to create knowledge of (1) what a creative process with material can look like and (2) how the correspondences with the material provided both possibilities for, and a hindrance to, the students’ remaking activity. What then becomes visible in the analyses is that what students learn as they encounter the material is dependent on how the human–material relation (correspondence) develops in the crafting process and on the purposes that emerge in the activity. According to McGarry (Citation2013), remaking activities could be a springboard for working with personal and social change; however, my research does not address issues of personal and social change. Nevertheless, what I have sought to show in this paper is that the materiality acts back upon those who engage with it. From the illustration of the research approach, it is possible to conclude that – as it is impossible to know how materiality or materials act on people in advance or on itself – the research approach also highlights the importance of human agency in the correspondence. One could argue that this leaves us with the knowledge that personal change can be made by working with remake projects, but knowing precisely how this happens is another matter.

The research approach also adds to the specific practice of educational sloyd, in that it can be used to create knowledge about how, in a remake project, students join forces with and answer to the material. Such knowledge opens up for pedagogical actions that can be used by teachers to facilitate possibilities in a sustainability context and to recontextualise old practices of remaking. If teachers want to educate for, in and about sustainability, I would argue that a key question is how humans learn to correspond to materials in socio-material activities. What I have illustrated with this research approach is that the specific materiality in these human –material relations both provide possibilities and present challenges, which are important to acknowledge when engaging with environmental and sustainability issues.

Learning to join forces and correspond with materials can also open up for experiences that humans want to have in relation to environmental and sustainability issues. For example, we as humans are entangled in human–material relations in our consumption patterns, with the waste we produce, and by our efforts to recycle, reduce, or reuse materials. By taking the correspondence approach to learning for sustainability, an opportunity arises for ESE pedagogy to contextualise human–material relations within our environments and with and through the socio-material contexts in which we live our lives. By doing so, educators can open up for embodied correspondences and experiences, and through this, the students can hopefully become prepared to correspond in new unforeseen ways and to be flexible enough to correspond wisely to unexpected changes in the environment. From this perspective, it becomes important to continue to create more empirically grounded knowledge concerning students’ encounters with materiality, that is, what materiality the students recognise and how they – with their hands, skin, eyes, ears, bodies and minds – learn to correspond accordingly.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hanna Hofverberg

Hanna Hofverberg has an interest in environmental and sustainability education (ESE) research, with particular attention to arts and crafts education, and research studies in the area of socio-material learning and transactional meaning making.

References

- Barad, K. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Towards and Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(3): 801–831. doi:10.1086/345321.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Clarke, D. A. G., and J. Mcphie. 2016. “From Places to Paths: Learning for Sustainability, Teacher Education and a Philosophy of Becoming.” Environmental Education Research 22(7): 1002–1024. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1057554.

- Coole, D., and S. Frost, eds. 2010. New Materialisms. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

- Crutzen, P. J., and E. F. Stoermer. 2000. “The Anthropocene.” IGBP Newsletter 41(17): 17–18.

- Fenwick, T. 2015. “Sociomateriality and Learning: A Critical Approach.” In The SAGE Handbook of Learning, edited by D. Scott and E. Hargreaves, 83–93. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781473915213.n8.

- Franow, I. 2002. “Rag-Rugs [Trasmattor].” In Fabrics Everywhere [tyg överallt], nordiska musset, 232–247. Stockholm: Nordiska Mussets Förlag.

- Hallén, M. 2002. “Rags Too Small to Use but Very Handy to Have [För Små Att Använda Men Bra Att ha.].” In Fabrics Everywhere [tyg överallt], nordiska musset, 220–231. Stockholm: Nordiska Museets Förlag.

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive – Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

- Ingold, T. 2013. Making – Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

- Jørgensen, N., K. D. Madsen, and J. Læssøe. 2018. “Waste in Education: The Potential of Materiality and Practice.” Environmental Education Research 24(6): 807–817. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1357801.

- Linell, P. 1994. Transcript of Speech and Conservation: Theory and Practice. [Transkription av tal och samtal: Teori och praktik]. Linköping: Linköpings universitet Tema Kommunikation.

- Lloro-Bidart, T. 2017. “A Feminist Posthumanist Political Ecology of Education for Theorizing Human-Animal Relations/Relationships.” Environmental Education Research 23(1): 111–130. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1135419.

- Mannion, G. 2007. “Going Spatial, Going Relational: Why ‘Listening to Children’ and Children's Participation Needs Reframing.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 28(3): 405–420. doi:10.1080/01596300701458970.

- McGarry, D. 2013. “Empathy in the Time of Ecological Apartheid a Social Sculpture Practice-Led Inquiry into Developing Pedagogies for Ecological Citizenship.” PhD diss., Rhodes University.

- McKenzie, M., and A. Bieler. 2016. Critical Education and Sociomaterial Practice: Narration, Place, and the Social. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Odegard, N. 2012. “When Matter Comes to Matter – Working Pedagogically with Junk Materials.” Education Inquiry 3(3): 387–400. doi:10.3402/edui.v3i3.22042.

- Palmsköld, A. 2013. Textile Remake – Material and Cultural Usage. [textilt återbruk – om materiellt och kulturellt slitage]. Halmstad: Gidlunds Förlag.

- Payne, P. G. 2016. “What Next? Post – Critical Materialisms in Environmental Education.” The Journal of Environmental Education 47(2): 169–178. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1127201.

- Pyyry, N. 2017. “Thinking with Broken Glass: Making Pedagogical Spaces of Enchantment in the City.” Environmental Education Research 23(10): 1391–1401. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1325448.

- Rautio, P. 2013. “Being Nature: Interspecies Articulation as a Species - Specific Practice of Relating to Environment.” Environmental Education Research 19(4): 445–457. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.700698.

- Rautio, P., R. Hohti, R.-M. Leinonen, and T. Tammi. 2017. “Reconfiguring Urban Environmental Education with ‘Shitgull’ and a ‘Shop.” Environmental Education Research 23(10): 1379–1390. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1325446.

- Resare, A. 2002. “Worth Preserving [Värt Att Vårda].” In Fabrics Everywhere [tyg överallt], nordiska musset, 207–219. Stockholm: Nordiska Museets Förlag.

- Russell, C. L. 2005. “Whoever Does Not Write Is Written: The Role of ‘Nature’ in Post‐Post Approaches to Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 11(4): 433–443. doi:10.1080/13504620500169569.

- Somerville, M. 2016. “Environmental and Sustainability Education: A Fragile History of the Present.” In The Sage Handbook of Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment, edited by D. W. L. Hayward and J. Pandya, 506–522. London: Sage.

- Sørensen, E. 2009. The Materiality of Learning – Technology and Knowledge in Educational Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Steffen, W., W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney, and C. Ludwig. 2015. “The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration.” The Anthropocene Review 2(1): 81–98. doi:10.1177/2053019614564785.

- Svenska MiljöEmissionsData (SMED). 2011. Mapping the amount and flows of textile waste [Kartläggning av mängder och flöden av textilavfall]. Accessed 28 October 2018. http://www.smed.se/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/SMED_Rapport_2011_46.pdf

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2011. Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Recreation Centre 2011. Stockholm: Ordförrådet AB.

- Taylor, A. 2017. “Beyond Stewardship: Common World Pedagogies for the Anthropocene.” Environmental Education Research 23(10): 1448–1461. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1325452.

- Van Poeck, K., and J. A. Lysgaard. 2016. “The Roots and Routes of Environmental and Sustainability Education Policy Research.” Environmental Education Research 22(3): 305–318. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1108393.