Abstract

Medical professionals need to be equipped with competencies to provide sustainable healthcare and promote planetary health. The aims of this study were to map the presence of planetary health themes in one Australian medical program, develop and pilot a planetary health blended-learning module drawing on constructivism learning theory, and evaluate the effectiveness of the activities. A mixed methods approach was used comprising quantitative mapping of learning outcomes, measurement of pre- and post-intervention planetary health knowledge, and a feedback survey. Mapping revealed little integration of environmental issues across the medical program. Student’s knowledge score increased by 2.37 points on average (95% confidence interval 1.66–3.09) (response rate 46%); 84.2% of respondents rated the activities as excellent/good. Since planetary health education is not currently required in Australian medical curricula, there is still little information for local medical educators on how to develop it, therefore studies such as this can provide some preliminary guidance.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.2025343 .

Introduction

The unprecedented levels of harm to the environment from escalating human pressure is hazardous for human health, necessitating a ‘planetary health’ approach to promoting human health and the health of the planet (Corvalan, Hales, and McMichael Citation2005; Whitmee et al. Citation2015). The World Health Organization has declared climate change the biggest health threat in the 21st Century (WHO Citation2015). The healthcare sector is vulnerable to the effects of, and contributes to, climate change, accounting for between 1 to 5% of total global carbon emissions and more than 5% for some national impacts (Lenzen et al. Citation2020). Australia has one of the highest levels of healthcare emissions in the world contributing to 7% of Australia’s total carbon footprint (Malik et al. Citation2018). Health systems need to work towards environmental sustainability, through lower carbon treatments, removing unnecessary procedures, preventing illness and promoting health (Barna et al. Citation2020; MacNeill, McGain, and Sherman Citation2021).

While health professionals are essential for advancing environmentally sustainable healthcare and strengthening health systems for adaptation, they may also work to promote patient and community understanding, build community resilience, support education and research, and advocate for sustainable government policies (Green et al. Citation2009; Capon, Talley Ac, and Horton Citation2018; Sainsbury et al. Citation2019; Xie et al. Citation2018). The Australian Medical Association (AMA) and their international counterparts – including the British Medical Association and the American Medical Association – have declared climate change a health emergency (Australian Medical Association (AMA) Citation2019). The Position Statements of prominent organisations including the AMA and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians indicate the need to mitigate climate change, in order to prevent the health impacts of climate change, and adaptation in order to protect the health of vulnerable population groups (Australian Medical Association (AMA) Citation2015; The Royal Australasian College of Physicians Citation2016).

The future health workforce needs to be equipped with the knowledge, skills and motivation not only to deliver sustainable healthcare, but to promote planetary health and drive action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (Shaw et al. Citation2021; Maxwell and Blashki Citation2016; Madden, McLean, and Horton Citation2018; Guzmán et al. Citation2021). The emergence of the SARS-Cov-2 virus (COVID-19) in 2019 has produced calls for medical education to provide an understanding of the climate crisis (coined the ‘climate pandemic’) (Nikendei, Cranz, and Bugaj Citation2021), and the One Health framework for interconnections between the health of people, animals and the environment underlying the emergence of novel zoonotic infections (Dykstra and Baitchman Citation2021). The planetary health lens views the dependence of human health on flourishing ecological and biophysical systems, providing a broader framework to understand these interconnections and identify solutions through multi-disciplinary, systems-level thinking (Guzmán et al. Citation2021; Stone, Myers and Golden Citation2018).

There is currently a considerable gap in formal learning opportunities on climate and environmental issues in medical programs, and medical students around the world are advocating for change through highlighting the gaps, monitoring action, and creating their own resources (Rabin, Laney, and Philipsborn Citation2020; IFMSA Citation2016; IFMSA Citation2020; Goshua et al. Citation2021; Canadian Federation of Medical Students; Omrani et al. Citation2020; PHRC). In the USA, 56% of medical schools surveyed included some One Health subject matter (Docherty and Foley Citation2021). A recent student-led survey reported only 15% of medical schools across 100 countries included climate change and health in the curriculum, with student-led activities in a further 12% (Omrani et al. Citation2020). The Planetary Health Report Card provides a detailed inspection of curricula, research, advocacy, support for student-led initiatives, and campus sustainability offered by medicals schools of the USA, Canada, UK, and Ireland (PHRC). In the most recent report, no schools received an ‘A’ for curriculum; 21% received a ‘B’, 48% a ‘C’, and 31% ‘D’ or ‘F’ (PHRC Citation2021).

To date, there has been no formal assessment of planetary health content within Australian medical school curricula. Although an indicator to track the incorporation of health and climate change education within Australia’s medical schools was scheduled for introduction to the MJA-Lancet Countdown in 2020, it is yet to be incorporated (Beggs et al. Citation2019; Madden, Horton, et al. Citation2020; Beggs et al. Citation2021). Surveys of educators confirm that concepts of climate change education and sustainable healthcare are not consistently embedded into medical professional curricula (Lal et al. Citation2021; Brand et al. Citation2021). While official organisations such as the Medical Deans of Australia and New Zealand (MDANZ) have developed and disseminated updated graduate outcome statements and learning outcomes for medical schools in Australia, these are yet to be formally incorporated into accreditation standards (Madden, Horton, et al. Citation2020). Therefore the extent to which planetary health is included in medical school curricula is reliant on the motivation of individual educators who have to overcome barriers such as lack of curriculum space, resourcing, and institutional priorities (Lal et al. Citation2021; Brand et al. Citation2021; Shea, Knowlton, and Shaman Citation2020).

The purpose of this study was to co-develop, implement, and evaluate a new blended-learning teaching module with and for medical students enrolled in the graduate medical program (MChD) at the Australian National University (ANU). The module comprised e-learning for knowledge transfer and inquiry-based group work. E-learning has been shown to be comparable to face-to-face teaching in terms of knowledge, skills gained, and student satisfaction levels (George et al. Citation2014). The e-learning module aimed to provide comprehensive information on interconnections between human health, and the health of the planet, whereas traditional medical curriculum largely focuses on human health in relation disease pathology and management, without taking environmental factors into account. Previous research has also indicated that medical curricula lack explicit learning outcomes and ‘hands-on’ learning opportunities in health advocacy (Douglas et al. Citation2018). Healthcare professionals will need to promote and advocate for planetary health. Therefore, to enhance students advocacy skills we applied a constructivist learning approach, where students are active makers of knowledge, rather than passive receivers from the teacher, through an inquiry-based workshop (O’Connor Citation2020).

The specific aims of this study were to map the presence of existing planetary health themes in the ANU Medical School curriculum, to develop and pilot two planetary health learning activities in the ANU medical curriculum, and to evaluate the effectiveness of the pilot planetary health learning activities in the ANU medical curriculum.

Methods

The ANU medical program is a graduate entry four-year program comprising two pre-clinical years (termed Phase 1) and two clinical years (Phase 2), graduating approximately 100 students each year. New e-learning and inquiry-based learning activities on planetary health were developed and evaluated using a mixed methods approach comprising quantitative mapping of learning outcomes, measurement of pre- and post-intervention planetary health knowledge through a 12-item multiple choice quiz, and a student feedback survey utilising Likert scale statements and open-ended questions. The project was aligned with basic principles of constructivism theory of learning. Briefly, the project research design was premised on building upon students’ existing knowledge constructs in relation to other related disciplinary areas of medical education such as biological, physical, and mental, where the learner assimilates, consolidates and adapts new and existing knowledge as well as critical reflection skills to develop a higher level of understanding and knowledge (Torre et al. Citation2006).

Curriculum mapping

The ANU Medical School curriculum map database was searched using the terms ‘climate’, ‘environment’, ‘planet*’, ‘sustain*’, ‘carbon’, ‘ecolog*’, ‘ecosystem’, ‘ecosocial’, ‘one health’ and ‘advoc*’.

The database predominantly includes level 1–3 learning outcomes for the MChD program provided in approved documentation. Level one includes the overarching program outcomes, level two the course level outcomes, level three the block level outcomes. Level four outcomes that describe the objectives of individual teaching sessions were identified through educational materials placed on the learning management system (LMS). Data were collected using Microsoft Excel, recording the number of learning outcomes within which search terms appeared in the curriculum and where they were located in the curriculum.

Development and implementation of learning resources

A blended-learning approach was used to develop two new learning activities that combined online learning resources (e-learning) as a flipped classroom element followed by in-class activities delivered to second year medical students over a three-week period in 2020 (e-learning: weeks 1–2; in-class: week 3). Second year students were chosen as the target audience for this initiative as curriculum mapping indicated a clustering of activity in year one of the program. The e-learning module was used for transfer of core knowledge on planetary health. This was followed by an inquiry-based workshop whereby students worked in small groups to research and develop practical advocacy solutions for a set of planetary health case studies which they then presented to the rest of the cohort. The group work component originally intended students to develop a ‘pitch’ for a strategy to advocate for planetary health issues to policy makers. Due to COVID-19 impacts on clinical teaching during 2020, this component could not go ahead in full and was substituted with the workshop.

The development of the blended module on planetary health was led by two 3rd year medical students who were employed as research assistants. The research assistants conducted an initial literature review to design the scope and structure of the e-learning module with guidance from the academic staff involved in the project. Research assistants then developed the e-learning module in Rise 360 (Articulate Global Inc.) which was reviewed and refined following discussion by all project members. External review of the module was conducted by a practising medical professional with specific interest and expertise in climate change and health who provided additional feedback. Research assistants also developed the scenarios used in the workshop which are outlined later in this section.

The e-learning module was published on the LMS and will subsequently be made publicly available. The learning outcomes were selected from proposed learning objectives developed by the MDANZ Climate Change and Health Working Group (Madden, Horton, et al. Citation2020):

Discuss the contribution of human activity to global and local environmental changes such as climate change, biodiversity loss and resource depletion.

Describe the mechanisms by which human health is affected by environmental change.

Explain how the health impacts of environmental change are distributed unequally within and between populations and the disparity between those most responsible and those most affected by change.

Compare the carbon footprint of healthcare systems for different countries and describe the major contributors to each.

Identify the role of healthcare professionals in advocating for policies and infrastructure that promote the availability, accessibility and uptake of healthy and environmentally sustainable behaviours.

The module comprised four parts. Part 1 – Introduction, provided an overview of planetary health. Part 2 – The Problem: the Anthropocene and the Great Acceleration, covered the contribution of human activity to environmental changes. Part 3 – The Effect: how changes in the natural system are affecting human health, described mechanisms by which human health is affected by climate change. Part 4 – The Solution: Our role as future medical professionals, discussed the role of healthcare professionals in advocating for policies and infrastructure that promote healthy and environmentally sustainable behaviours. A feature of the e-learning was the inclusion of clinical cases studies, such as a patient with heat stroke as an example of direct environmental health effects and a patient with pollution-induced exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an example of an indirect effect mediated through changes to natural systems.

The inquiry-based component consisted of a 2-hour facilitated small group workshop designed to develop advocacy skills and identify practical ways to contribute to improving planetary health. The workshop was delivered using Zoom due to COVID-19 restrictions. An initial icebreaker activity asked students to discuss their experiences with advocacy in any setting. Students were then divided into small groups of four students (using the breakout room function) and selected a trigger scenario for the next activity. Scenario topics consisted of:

designing an advocacy campaign to reduce the carbon footprint in the local hospital;

assisting patients with continuity of care in the aftermath of bushfires;

an advocacy campaign for an ecological intervention in the community;

a campaign to lobby local government to implement policies to cut emissions produced by motorised transport;

advocacy for healthy food options in medical practice and community settings to prevent illness and promote health.

Each scenario handout contained a brief outline, a task, suggested resources, and prompts. Students worked on the task in their group for 30 min and presented their findings back to the larger group. Facilitators were instructed to keep the students focused on the tasks and guide them through the process similar to the problem-based learning format (Azer Citation2005; Wood Citation2003).

Evaluation

All 2nd year medical students were invited to participate in the evaluation which consisted of pre- and post-learning knowledge quizzes and a feedback survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Ethics approval was obtained from the ANU Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/448). An information session was held during the first week of the final teaching block of the year. Full details, instructions, and links to the quizzes and survey were provided on the LMS.

Students were instructed to complete the pre-lesson quiz before commencing the e-learning module. The total possible score for the quiz was 12. The post-lesson quiz consisted of the same questions used for the pre-lesson quiz and was made available to students, along with the feedback survey, at the end of the workshop. Questions covered simple recall on students’ understanding of planetary health, climate change and health impacts of environmental changes covered in the e-learning module (). The Purdue Instructor Course Evaluation Service (Purdue University Citation2020) was used to guide question development for the feedback survey, covering domains of goals and objectives, relevance of content, teaching/learning of relationships and concepts, general student perceptions, student outcomes, diversity issues/respect/rapport, organisation and clarity. Three sets of questions were generated related to (i) the overall rating of ‘the course’, (ii) the e-learning, and (iii) the workshop using a combination of statements with quantitative Likert-scale or qualitative free text response options. Survey questions are provided in the supplementary file ().

Table 1. Curriculum mapping of learning outcomes related to environment, climate, sustainability, or advocacy.

Table 2. Themes identified from full text responses and example comments.

Data were analysed using Stata release 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and figures generated in Microsoft Excel. Descriptive analyses were undertaken using frequencies for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and p25-p75 for num erical variables. Two sample t-test was used to compare the mean scores between different sub-groups, and a paired t-test to report the mean change in scores and 95% confidence intervals (CI) within groups. A thematic analysis of the free-text survey responses was undertaken with themes coded using an inductive approach. The response categories initially generated were reviewed and combined where categories were found to be representing a similar theme.

Results

Curriculum mapping

A total of 30 outcomes were identified of which five were level three outcomes and the rest were level four (). However, one level three outcome in year four on advocacy was not related to environmental or climate change. Of the 25 level four outcomes, 19 were located in phase one (with most in year one), of which 12 were provided by the population health theme, three by medical sciences, and two by professionalism and leadership. There was a lack of relevant learning outcomes in problem-based or case-based learning. Environment was the most common term included in learning outcomes, with fewer terms related to climate change and one that mentioned One Health.

Evaluation

Out of 99 students enrolled in the course, 88 attempted the e-learning and 81 attended the workshop; 49 students participated in the evaluation study (response rate 49.5%). All 49 consented to the pre- and post-lesson knowledge tests, and 44 consented to the feedback survey.

Knowledge tests

Most students in the study (n = 46) completed the pre-lesson quiz, of which 44 students accessed the e-learning module. Eight students (18.2%) accessed the e-learning before attempting the quiz and 21 students (47.7%) accessed the e-learning during the pre-lesson quiz. The median time between pre-accessing the e-learning and completing the quiz was 1.16 min (p25-p75 = 0.32–27.2 min).

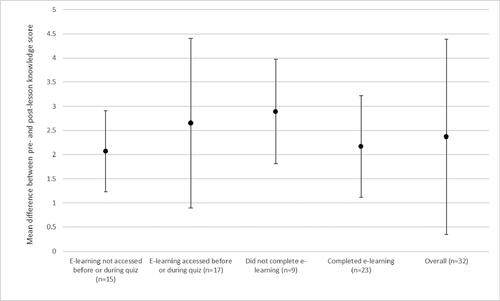

The post-lesson quiz was completed by 34 students; 32 completed both pre- and post-lesson quizzes. The total number of correct answers ranged from 3 to 10 for the pre-lesson quiz and 6 to 12 for the post-lesson quiz. The mean pre- and post-lesson scores were 7.09 (SD = 1.84) and 9.53 (SD = 1.69), respectively, increasing by 2.37 points on average (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.66–3.09; p < 0.0001) (). The mean difference between pre- and post-lesson quiz scores was greater for those who accessed e-learning prior to or during the pre-lesson quiz (2.65, 95% CI 1.60–3.69) compared to those who did not (2.07, 95%CI 0.99–3.14), however the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.42) (). Similarly, there was little difference in the change in quiz scores between those who fully completed the e-learning based on LMS metrics and those who did not.

User feedback

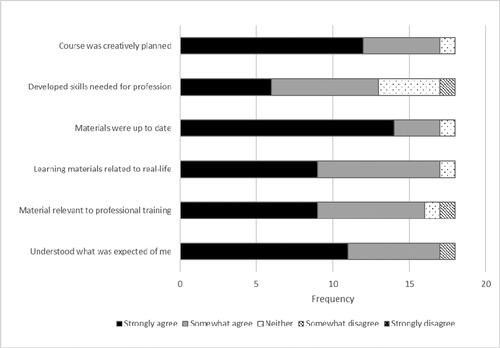

The feedback survey was completed by 19 students (9 males, 8 females, 2 unspecified; age range 22–38 years). The overall course presentation was rated as excellent or good by 16 students (84.2%). Students generally agreed with all statements related to the new resources collectively, particularly the use of up-to-date materials and creative planning of the course ().

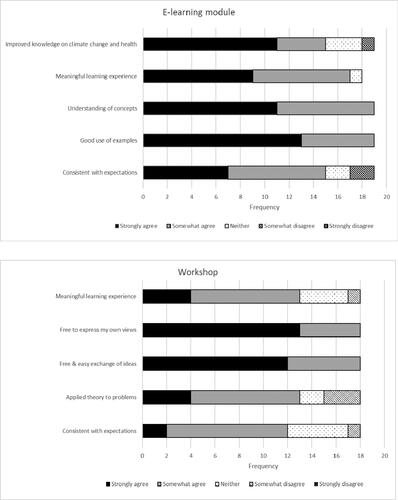

The e-learning module itself was well rated, with all students who responded agreeing that the module made good use of examples and built an understanding of concepts ( top panel). Most felt it provided a meaningful learning experience (n = 17, 89%). The majority also felt that it improved their knowledge on climate change and health or that the module was consistent with their prior expectations (n = 15, 78.9%). Of those that agreed their knowledge improved, their knowledge score increased on average by 3.46 points (95% CI 2.34, 4.58) compared to 0.67 points (95% CI −3.13, 4.46; p = 0.03) for those who did not agree or neither agreed nor disagreed. However, the mean baseline pre-test score was lower (7.20, 95%CI 6.44, 7.96) for those reporting improvement compared to those with perceived little to no improvement (9.33, 95% CI 7.90, 10.77; p = 0.02).

All students felt that they could express their views and there was free and easy exchange of ideas during the workshop ( bottom panel). Fewer students (n = 13, 68.4%) felt that the workshop was a meaningful learning experience or was consistent with their expectations (n = 12, 63.2%) compared to the e-learning module. However, there were no instances of strong disagreement with any of the statements presented.

summarises the results of the qualitative analysis of the open-ended questions from the evaluation survey. Fourteen students provided free text comments regarding the e-learning module from which 23 responses were identified and coded to four response categories (). The length of the e-learning module was most frequently commented on, accounting for 8 responses indicating that it was too long and repetitive. Other responses regarding structure (n = 8), and content (n = 4) provided insights for module improvement, such as splitting the lesson into two or providing increased timetable space, and improved streamlining. However, students were generally enthusiastic about the interactive nature of the lesson including links to external videos, interactive quizzes, and clinical case studies.

Eight students commented on the workshop, from which 14 responses were coded to five categories: workshop format (4 responses), content (5 responses), interaction with peers (3 responses), duration (1 response), and linkage between e-learning and workshop (1 comment). Responses indicated the workshop was too focussed on advocacy without adequate exposure to relevant background knowledge such as advocacy steps, or time to understand the scenarios. Responses were generally positive regarding the active style of learning with groups being presented problem solving tasks.

Seven students provided text responses to the course generally, of which four were very positive (demonstrating their enjoyment of the course, the relevancy of the topic and the mode of delivery. The less positive responses related to the length of the e-learning module with a suggestion to provide the course over a few interactive sessions.

Discussion

This study reports the development, implementation and evaluation of new planetary health educational activities for a graduate medicine program in an Australian university. Due to geographical variations in environmental impacts on health, it is important for doctors to learn how planetary health issues apply to their own local contexts. Therefore, a blended-learning module was co-designed with medical students as a first step to improving planetary health content that was found to be lacking following a curriculum mapping exercise. Activities comprised an e-learning component to provide foundation planetary health knowledge and inquiry-based learning group work to apply knowledge and develop skills in planetary health advocacy. Measurement of the short-term change in student planetary health knowledge indicated a modest improvement following engagement with the activities, which were also rated positively in student feedback.

Medical professionals will be at the forefront of the health and social impacts of environmental change, requiring them to develop and deliver sustainable healthcare, manage climate-related illness, provide local health promotion and prevention, and work in health systems disrupted by extreme events (Shaw et al. Citation2021; Maxwell and Blashki Citation2016; Madden, McLean, and Horton Citation2018; McLean, Gibbs, and McKimm Citation2020). Core competencies include identification of vulnerable patients, risk factor management, diagnosis and management of climate-related physical and mental illness (Maxwell and Blashki Citation2016). In addition, the shifting distribution of health needs with environmental change, plus the geographic variation of the impact of environmental change on communities, requires medical professionals to be literate in planetary and public health (Maxwell and Blashki Citation2016).

There is currently little formal education on environmental change and sustainable healthcare in medical schools globally, with only 15% of medical schools surveyed across 100 countries including climate change and health in the curriculum (Omrani et al. Citation2020). Engagement with climate change by student bodies is driving curriculum reform. The student-led Planetary Health Report Card grades 62 medical schools in the USA, Canada, UK, and Ireland on their inclusion of planetary health curricula (PHRC). The Canadian Federation of Medical Students established the Health and Environment Adaptive Response Task Force with a core aim of developing a set of planetary health competencies to be addressed in medical school curricula in Canada (Canadian Federation of Medical Students). The Australian Medical Students Association position statement on climate change and health calls for integration of teaching on climate change and human health into medical curricula (Medical Students Association of Australia., 2020). The AMEE Consensus Statement on Planetary Health and Education for Sustainable Healthcare provides examples of a wide array of learning approaches covering both clinically focused activities and those with wider public health relevance (Shaw et al. Citation2021). Such approaches can be horizontally (i.e. co-ordination of content within course levels) and vertically (i.e. co-ordination of content across course levels) integrated into the curriculum through problem- or case-based learning, clinical skills training, and placement projects, and through assessment including OSCEs (Shaw et al. Citation2021; Maxwell and Blashki Citation2016).

However, specific examples of educational initiatives described by medical programs are lacking in the literature. Our study explicitly describes the development and evaluation of new planetary health educational resources and outlines their alignment within the broader context of the medical curriculum in our program. As environmental impacts on health vary geographically, planetary health education content may vary across the world and smaller-scale local level studies, such as this one, are valuable for understanding context specific curricula. The addition of the new resources to the second year of our program enhances the vertical integration of planetary health into the program, through complementing existing lectures on environmental determinants and climate change in first year and linking to placement projects in later years where students have the opportunity to engage with planetary health topics. Recent examples include a literature review on the health impacts of waste incineration conducted with the Public Health Association of Australia (Tait et al. Citation2020), and a scoping review of optimal approaches for communicating risk of bushfire smoke exposure to affected populations (Heaney et al. Citation2021). While the new activities are welcome, they are confined to the population health theme and horizontal integration is lacking. Mapping of learning outcomes identified minimal inclusion of environmental and climate issues across other themes of the medical program, such as clinical skills, or through different learning activities such as PBL sessions. A full curriculum review is required to constructively align learning outcomes, learning activities, assessment, and feedback for students to be equipped with core competencies to promote planetary health (Shaw et al. Citation2021). However, educators need to overcome the barriers of lack of curriculum space, resourcing, and institutional priorities in order to effectively develop and implement the curriculum modifications that are needed (Lal et al. Citation2021; Brand et al. Citation2021; Shea, Knowlton, and Shaman Citation2020).

Our study is characterised by two key features, namely student engagement and a constructivist approach to learning. Through the employment of two current students to work with staff on the project, we were able to identify and test activities that would actively engage students. This resulted in the inclusion of relevant scenarios related to planetary health issues in each activity, such as the trigger topics used in the workshop and inclusion of clinical cases studies in the e-learning module (e.g. heat stroke and pollution-induced respiratory issues). Engaging students actively in their learning where they are ‘producers’ or ‘partners’ of knowledge, rather than consumers, enhances their learning experience (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; Bruff Citation2013). The current student-led international initiatives to improve climate change education in medical programs highlights the importance of engaging with students for curriculum development (IFMSA Citation2020; PHRC). Through the advocacy group work, students demonstrated their understanding as they developed, discussed and explained their ideas for advocacy solutions related to a set of planetary health case studies. Creation of knowledge by the learning as opposed to transmission of knowledge from an instructor is central to constructivist learning theory (O’Connor Citation2020; Torre et al. Citation2006).

Overall student feedback was positive suggesting they enjoyed the learning, and students embraced the opportunity to engage in interactive learning through the problem-solving group work activity. One suggestion was to design a campaign from scratch rather than using existing ideas in the workshop, which was the original intention and could not proceed due to the impact of Covid-19 on delivery of the core medical curriculum. Under the original plan, students would be required to develop a ‘pitch’ for a strategy to advocate for planetary health issues of their choosing to policy makers which would be peer-assessed formatively through student presentations. Peer assessment has several advantages, such as encouraging students to critically reflect on each other’s work, be involved in the assessment process, providing more feedback than that obtained from just 1–2 educators, development of generic skills such as constructive feedback, critical appraisal, and working co-operatively (Chan Citation2010; UNSW).

Feedback also indicated the e-learning was too long and repetitive. Future improvements could focus on identifying areas to reduce the e-learning content and splitting it into two lessons to reduce learner fatigue. In addition, future iterations will be piloted with a set of stakeholders including medical students, medical professionals and educators, and climate change experts. This would also allow the incorporation of scenarios with relevance to a wider range of clinical specialties such as sustainable surgery.

There was modest improvement in content knowledge after completing the learning, and although there was some contamination of scores because some students accessed the e-learning either before or during the pre-lesson knowledge quiz, there was negligible difference between the two groups. Students were also comparable in knowledge gained whether they fully completed the e-learning or not; however, measurement was based on LMS metrics that recorded interaction with in-built activities and students may have received adequate knowledge without full engagement with the interactions.

This study has several limitations. Curriculum mapping was limited to searching available sources of learning outcomes and may have missed some sources of level four outcomes. A low response rate to the feedback survey limits the representativeness of the findings and the conclusions that can be drawn as the more engaged students are likely to provide feedback. However, the consistency between responses on some domains, such as the time taken to complete the e-learning, balanced with the positive responses to the initiative generally, suggest the responses are valid and will be taken into consideration when revising the learning activities for future use. Future evaluations could also examine students perceived usefulness of the learning, and whether students applied their learning to the advocacy presentations. The high baseline pre-lesson knowledge quiz results indicated that many students may have already had good planetary health knowledge, although the quiz may have been too easy or insufficiently long to be an accurate measure of their knowledge. In addition, a pre- and post-lesson test only measures short term knowledge acquisition and long-term retention would need to be specifically assessed. The disruption to teaching due to COVID-19 resulting in the implementation of a ‘plan b’ for the inquiry-based component was sub-optimal and highlighted the barriers to introducing new curricula into medical programs with already full curricula. There was some irony in the institutional de-prioritisation of new planetary health learning activities during a global pandemic.

Education is considered one of a set of social tipping dynamics – where disruptive change can reduce global greenhouse emissions - to achieve stabilisation of the earth’s climate by 2050 (Otto et al. Citation2020). Rapid mobilisation of delivery of sustainable healthcare education is required for education to trigger tipping, however delay to the implementation of the MJA-Lancet Countdown target setting in 2020 due to Covid-19 is undermining progress (Beggs et al. Citation2021; McLean, Gibbs, and McKimm Citation2020). The UK General Medical Council requires doctors qualifying and registering to understand and apply principles of sustainable healthcare (General Medical Council), yet there is no such requirement by the Australian Medical Council (AMC) for accreditation of primary medical programs which have not been updated since 2012 (Australian Medical Council Limited Citation2012).

Conclusions

The new learning materials filled an identified curriculum gap and were well received by students. However, ad hoc filling of gaps by motivated educators in medical programs without widespread institutional support is sub-optimal. Medical schools need to prioritise and commit to curriculum reform that integrates planetary health and sustainable healthcare competencies horizontally and vertically into medical programs. The anticipated revisions to AMC criteria if adopted and implementation of the Lancet Countdown indicator are urgently needed to drive action in medical education. In addition, inclusion of medical schools across Australia and New Zealand in the Planetary Health Report Card is recommended. Since planetary health education is not currently required in Australian medical curricula, there is still little information for local medical educators on how to develop it, therefore studies such as this can provide some preliminary guidance.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Arnagretta Hunter for expert feedback on the e-learning activity.

Disclosure statement

CS is a member of the Medical Deans of Australia and New Zealand Climate Change and Health Working Group.

Data availability statement

Data will be archived with the ANU Data Commons and available on application.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claudia Slimings

Claudia Slimings BSc, PGDipHlthSci, PGCertHBE, PhD, FHEA is Senior Lecturer in Population Health at the Medical School, Australian National University, Australia. ORCID http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7988-1186

Emily Sisson

Emily Sisson BMedSc, MHPol is a medical student at the Medical School, Australian National University, Australia.

Connor Larson

Connor Larson BSc(Hons) is a medical student at the Medical School, Australian National University, Australia.

Devin Bowles

Devin Bowles BA, MA, BSc(Hons) PhD was Lecturer in Population Health at the Medical School, Australian National University, Australia and Executive Director at the Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australia for the duration of this project. Currently Chief Executive Officer at Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Association ACT (ATODA).ORCID http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6797-1878.

Rafat Hussain

Rafat Hussain MBBS, MPH, PhD is Associate Professor in Population Health at ANU Medical School. ORCID http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2900-4457

References

- Australian Medical Association. 2019. “Climate Change is a Health Emergency.” Accessed June 23, 2021. https://ama.com.au/media/climate-change-health-emergency

- Australian Medical Association. 2015. “Climate Change and Human Health – 2004. Revised 2008. Revised 2015". [web page]. Accessed June 19, 2021. https://ama.com.au/position-statement/ama-position-statement-climate-change-and-human-health-2004-revised-2015

- Australian Medical Council Limited. 2012. “Standards for Assessment and Accreditation of Primary Medical Programs by the Australian Medical Council 2012.” ACT: AMC https://www.amc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Standards-for-Assessment-and-Accreditation-of-Primary-Medical-Programs-by-the-Australian-Medical-Council-2012.pdf

- Azer, S. A. 2005. “Challenges Facing PBL Tutors: 12 Tips for Successful Group Facilitation.” Medical Teacher 27 (8): 676–681. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500313001.

- Barna, S., F. Maric, J. Simons, S. Kumar, and P. J. Blankestijn. 2020. “Education for the Anthropocene: Planetary Health, Sustainable Health Care, and the Health Workforce.” Medical Teacher 42 (10): 1091–1096. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1798914.

- Beggs, P. J., Y. Zhang, H. Bambrick, H. L. Berry, M. K. Linnenluecke, S. Trueck, P. Bi, et al. 2019. “The 2019 Report of the MJA-Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: A Turbulent Year with Mixed Progress.” The Medical Journal of Australia 211 (11): 490-1.e21–491.e21. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50869.

- Beggs, P. J., Y. Zhang, A. McGushin, S. Trueck, M. K. Linnenluecke, H. Bambrick, et al. 2021. “The 2021 Report of the MJA-Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Australia Increasingly out on a Limb.” Medical Journal of Australia. 215 (9): 390–392.e22. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51302.

- Brand, G., J. Collins, G. Bedi, J. Bonnamy, L. Barbour, C. Ilangakoon, R. Wotherspoon, et al. 2021. “"I Teach It Because It Is the Biggest Threat to Health": Integrating Sustainable Healthcare into Health Professions Education.” Medical Teacher 43 (3): 325–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1844876.

- Bruff, D.. 2013. “Students as Producers: An Introduction.” Accessed June 8. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/2013/09/students-as-producers-an-introduction/

- Canadian Federation of Medical Students. “Planetary Health Competencies.” Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.cfms.org/what-we-do/global-health/heart-competencies

- Capon, A. G., N. J. Talley Ac, and R. C. Horton. 2018. “Planetary Health: What Is It and What Should Doctors Do?” The Medical Journal of Australia 208 (7): 296–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja18.00219.

- Chan, C. 2010. “Self and Peer Assessment.” Accessed June 8, 2021. https://ar.cetl.hku.hk/self_peer.htm

- Corvalan, C., S. Hales, and A. McMichael. 2005. “Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Health Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.” Geneva: WHO http://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.357.aspx.pdf

- Docherty, L., and P. L. Foley. 2021. “Survey of One Health Programs in U.S. medical Schools and Development of a Novel One Health Elective for Medical Students.” One Health (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 12: 100231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100231.

- Douglas, A., D. Mak, C. Bulsara, D. Macey, and I. Samarawickrema. 2018. “The Teaching and Learning of Health Advocacy in an Australian Medical School.” International Journal of Medical Education 9: 26–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5a4b.6a15.

- Dykstra, M. P., and E. J. Baitchman. 2021. “A Call for One Health in Medical Education: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Underscores the Need to Integrate Human, Animal, and Environmental Health.” Academic Medicine 96 (7): 951–953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004072.

- General Medical Council. “Outcomes for Graduates.” London: GMC 2018. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/standards-and-outcomes/outcomes-for-graduates/outcomes-for-graduates

- George, P. P., N. Papachristou, J. M. Belisario, W. Wang, P. A. Wark, Z. Cotic, K. Rasmussen, et al. 2014. “Online eLearning for Undergraduates in Health Professions: A Systematic Review of the Impact on Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes and Satisfaction.” Journal of Global Health 4 (1): 010406. doi:https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.04.010406.

- Goshua, A., J. Gomez, B. Erny, M. Burke, S. Luby, S. Sokolow, A. D. LaBeaud, et al. 2021. “Addressing Climate Change and Its Effects on Human Health: A Call to Action for Medical Schools.” Academic Medicine 96 (3): 324–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003861.

- Green, E. I., G. Blashki, H. L. Berry, D. Harley, G. Horton, and G. Hall. 2009. “Preparing Australian Medical Students for Climate Change.” Australian Family Physician 38 (9): 726–729.

- Guzmán, C. A. F., A. A. Aguirre, B. Astle, E. Barros, B. Bayles, M. Chimbari, N. El-Abbadi, et al. 2021. “A Framework to Guide Planetary Health Education.” The Lancet. Planetary Health 5 (5): e253–e255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00110-8.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. “Engagement through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education.” York, UK: Higher Education Academy. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/engagement_through_partnership.pdf

- Heaney, E., L. Hunter, A. Chulow, D. Bowles, and S. Vardoulakis. 2021. “Efficacy of Communication Techniques and Health Outcome of Bushfire Smoke Exposure: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (20): 10089. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010889.

- IFMSA. 2016. “International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations [IFMSA] Training Manual: Climate and Health.” https://ifmsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Final-IFMSA-Climate-and-health-training-Manual-2016.pdf

- IFMSA. 2020. “International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations [IFMSA] Policy Document. Health, Environment and Climate Change.” https://ifmsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GS_MM2020_Policy_Climate-Change-amended.pdf

- Lal, A., E. Walsh, A. Weatherell, and C. Slimings. 2021. “Climate Change Education in Public Health and Medical Curricula in Australian and New Zealand Universities: A Mixed Methods Study of Barriers and Areas for Further Action.” medRxiv [Internet]. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.11.21258793.

- Lenzen, M., A. Malik, M. Li, J. Fry, H. Weisz, P.-P. Pichler, L. S. M. Chaves, et al. 2020. “The Environmental Footprint of Health Care: A Global Assessment.” The Lancet. Planetary Health 4 (7): e271–e279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30121-2.

- MacNeill, A. J., F. McGain, and J. D. Sherman. 2021. “Planetary Health Care: A Framework for Sustainable Health Systems.” The Lancet. Planetary Health 5 (2): e66–e68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00005-X.

- Madden, D. L., G. L. Horton, and M. McLean. 2020. “Preparing Australasian Medical Students to Practise Environmentally Sustainable Health Care.” Medical Journal of Australia. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50585. (online ahead of print).

- Madden, D. L., M. McLean, M. Brennan, and A. Moore. 2020. “Why Use Indicators to Measure and Monitor the Inclusion of Climate Change and Environmental Sustainability in Health Professions’ Education?” Medical Teacher 42 (10): 1119–1122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1795106.

- Madden, D. L., M. McLean, and G. L. Horton. 2018. “Preparing Medical Graduates for the Health Effects of Climate Change: An Australasian Collaboration.” The Medical Journal of Australia 208 (7): 291–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.01172.

- Malik, A., M. Lenzen, S. McAlister, and F. McGain. 2018. “The Carbon Footprint of Australian Health Care.” The Lancet. Planetary Health 2 (1): e27–e35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30180-8.

- Maxwell, J., and G. Blashki. 2016. “Teaching about Climate Change in Medical Education: An Opportunity.” Journal of Public Health Research 5 (1): 673. doi:https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2016.673.

- McLean, M., T. Gibbs, and J. McKimm. 2020. “Educating for Planetary Health and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care: Responding with Urgency.” Medical Teacher 42 (10): 1082–1084. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1795107.

- Medical Students Association of Australia. 2020. “Climate Change and Health. Position Statement.” https://amsa.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/AMSA/Policy/G/Climate%20Change%20and%20Health%20(2020)_1.pdf

- Nikendei, C., A. Cranz, and T. J. Bugaj. 2021. “Medical Education and the COVID-19 Pandemic – A Dress Rehearsal for the "Climate Pandemic”.” GMS Journal for Medical Education 38 (1): Doc29.

- O’Connor, K. 2020. “Constructivism, Curriculum and the Knowledge Question: Tensions and Challenges for Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1750585.

- Omrani, O. E., A. Dafallah, B. Paniello Castillo, B. Q. R. C. Amaro, S. Taneja, M. Amzil, M. R. U. Sajib, et al. 2020. “Envisioning Planetary Health in Every Medical Curriculum: An International Medical Student Organization’s Perspective.” Medical Teacher 42 (10): 1107–1111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1796949.

- Otto, I. M., J. F. Donges, R. Cremades, A. Bhowmik, R. J. Hewitt, W. Lucht, J. Rockström, et al. 2020. “Social Tipping Dynamics for Stabilizing Earth’s Climate by 2050.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (5): 2354–2365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900577117.

- PHRC. 2021. “Planetary Health Report Card. 2020-2021 Summary Report.” https://phjrc.files.wordpress.com/2021/04/2021-phrc-summary-report-final-1.pdf

- PHRC. “Planetary Health Report Card.” Accessed June 8, 2021. https://phreportcard.org/

- Purdue University. 2020. “Purdue Instructor Course Evaluation Service.” https://www.purdue.edu/idp/Documents/PICES_catalog.pdf

- Rabin, B. M., E. B. Laney, and R. P. Philipsborn. 2020. “The Unique Role of Medical Students in Catalyzing Climate Change Education.” Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development 7: 2382120520957653. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520957653.

- Sainsbury, P., K. Charlesworth, L. Madden, A. Capon, G. Stewart, and D. Pencheon. 2019. “Climate Change Is a Health Issue: What Can Doctors Do?” Internal Medicine Journal 49 (8): 1044–1048. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14380.

- Shaw, E., S. Walpole, M. McLean, C. Alvarez-Nieto, S. Barna, K. Bazin, et al. 2021. “AMEE Consensus Statement: Planetary Health and Education for Sustainable Healthcare.” Medical Teacher 43(3): 1–15.

- Shea, B., K. Knowlton, and J. Shaman. 2020. “Assessment of Climate-Health Curricula at International Health Professions Schools.” JAMA Network Open 3 (5): e206609. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6609.

- Stone, S. B., S. S. Myers, and C. D. Golden. 2018. “Cross-Cutting Principles for Planetary Health Education.” The Lancet. Planetary Health 2 (5): e192–e193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30022-6.

- Tait, P. W., J. Brew, A. Che, A. Costanzo, A. Danyluk, M. Davis, A. Khalaf, et al. 2020. “The Health Impacts of Waste Incineration: A Systematic Review.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44 (1): 40–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12939.

- The Royal Australasian College of Physicians. 2016. “Climate Change and Health Position Statement.” https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/climate-change-and-health-position-statement.pdf

- Torre, D. M., B. J. Daley, J. L. Sebastian, and D. M. Elnicki. 2006. “Overview of Current Learning Theories for Medical Educators.” The American Journal of Medicine 119 (10): 903–907. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.037.

- UNSW. “University of New South Wales. Student Peer Assessment.” Accessed June 8, 2021. https://teaching.unsw.edu.au/peer-assessment

- Whitmee, S., A. Haines, C. Beyrer, F. Boltz, A. G. Capon, B. F. de Souza Dias, A. Ezeh, et al. 2015. “Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on Planetary Health.” The Lancet 386 (10007): 1973–2028. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1.

- WHO. 2015. “World Health Organization [WHO] Calls for Urgent Action to Protect Health from Climate Change – Sign the Call.” Accessed Jun 8. https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2015-who-calls-for-urgent-action-to-protect-health-from-climate-change-sign-the-call

- Wood, D. F. 2003. “Problem Based Learning.” BMJ 326 (7384): 328–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7384.328.

- Xie, E., E. F. de Barros, A. Abelsohn, A. T. Stein, and A. Haines. 2018. “Challenges and Opportunities in Planetary Health for Primary Care Providers.” The Lancet. Planetary Health 2 (5): e185–e187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30055-X.