Abstract

This article argues that revisions of curricula in teacher education, undertaken in response to the UN’s Agenda 2030, goal 4.7, and the OECD’s The Future of Education and Skills, need to consider new ways of teaching topics related to current environmental issues. Grounded in ecocriticism and dialogic teaching practices, this article promotes ecocritical dialogues, as developed by the research group Nature in Children’s Literature and Culture, as one viable teaching approach. Ecocritical dialogues engage with a conceptual figure developed by the group, the NatCul Matrix, which functions as a grid for the discussion of different materials, texts, and practices, in dynamic dialogue with main figures of thought in the environmental discourse. The article further proposes a set of questions as a framework for setting up ecocritical dialogues. Ecocritical dialogues aim to enable student teachers to experience and reflect upon environmentally oriented teaching practices.

In his opening speech at COP27, Secretary-General of the United Nations António Guterres painted a dismal picture of our current global environmental crisis: ‘Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing. Global temperatures keep rising. And our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible. We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator’ (Guterres Citation2022). While acknowledging the urgency of the situation as depicted by Guterres, this article emphasises that ‘the ecological crisis is not only a crisis of the physical environment but also a crisis of the cultural and social environment’ (Bergthaller et al. Citation2014). Therefore, although the situation calls for urgent action, working to reconfigure the cultural and social environment remains important, since the cultural and social environment holds our potential collective respond-ability. The chances for viable and democratic long-term solutions are improved by the development of dialogic skills, which therefore play a significant part as we seek to reconfigure our teaching practices.

Drawing on theoretical and empirical research from the context of Norwegian teacher education and on the work of the research group Nature in Children’s Literature and Culture (NaChiLitCul) at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL), this article lays out the theoretical foundations of ecocritical dialogues and discusses how such dialogues can provide student teachers with opportunities to experience and reflect upon their physical surroundings but also on the figures of thought frequently called upon in interpretations and discussions of the environment. Grounded in ecocriticism and dialogic teaching practices, ecocritical dialogues are suggested as one viable approach, among the plurality of approaches required to help implement the competencies related to sustainability called for by the United Nations (Citationn.d.), Agenda 2030, goal 4.7, and the OECD’s The Future of Education and Skills. Education 2030 (OECD Citation2018a). The aim of introducing ecocritical dialogues in teacher education is to reconfigure and revise teaching practices, based on the view that such practices demand critical thinking and collaboration, also directed specifically towards examining the ways in which we think and talk about human relationship(s) to the natural world.

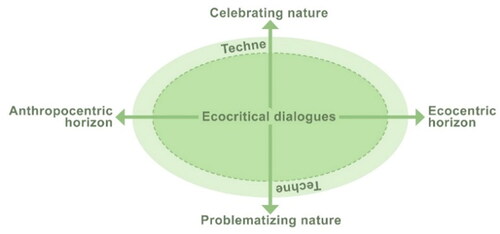

The discussion of the theoretical foundations of ecocritical dialogues starts from an overview of the educational setting of our research, which we position in relation to the, increasingly expansive, field of ecocriticism. Based on this theoretical engagement with ecocriticism, the research group NaChiLitCul has developed an analytical tool: The Nature in Culture Matrix which works as a schematic overview of main positions within ecocritical discourses (Goga et al. Citation2018; see ). The matrix facilitates analysis and discussion of ecocritical aspects of a variety of texts and practices and is linked to the wider field of dialogic teaching and formation (Bildung) discourses. The article concludes by outlining how ecocritical dialogues may work as an educational approach to enable student teachers within different subjects and educational settings to experience and reflect upon environmentally oriented teaching practices.

Figure 1. NatCul matrix (Goga et al. Citation2018, 12).

The educational setting of ecocritical dialogues

According to the OECD (Citation2018b), young people require education to enable them to ‘[t]ake action for collective well-being and sustainable development’ (11). To meet this requirement, educational practices supporting critical thinking competency and collaboration competency are needed. Following UNESCO’s (2017) description of these competencies, the former can be understood as the ability to ‘question norms, practices and opinions; to reflect on one’s own values, perceptions and actions; and to take a position in the sustainability discourse’, and the latter as being able to ‘learn from others; to understand and respect the needs, perspectives and actions of others (empathy); to understand, relate to and be sensitive to others (empathic leadership); to deal with conflicts in a group; and to facilitate collaborative and participatory problem solving’ (UNESCO Citation2017, 10). To enhance students’ critical thinking and collaboration competencies, it would be helpful for student teachers to experience and engage with tools suitable to develop such competencies, such as the ecocritical dialogues proposed here.

Our work and research on what we have termed ecocritical dialogues respond to scholarly works and teaching practices related to the broad field of ecocritical and environmental education, as well as to challenges within an educational field consisting of cross-national policy documents, national reports, and curricula.Footnote1 Since 2013, the NaChiLitCul research group has been building a national research field on ecocriticism within teacher education that includes the subjects of Norwegian, English, Physical Education, Natural Science, Arts and Crafts, and Food and Health. Additionally, the group has developed and tested suitable and collaborative teaching practices to encourage students to participate in the environmental discourse. NaChiLitCul was founded in response to an identified lack of ecocritical reflection in teaching practices within a Nordic and Norwegian educational context. The NaChiLitCul-edited volume Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues (Goga et al. Citation2018) sought to demonstrate the applicability of the NatCul Matrix to ecocritical analyses of Nordic cultural texts and practices in particular. Reworking the various syllabi in teacher education to include both ecocritical theory and appropriate reading material for facilitating group discussions on environmental issues, within and across a variety of school subjects, has also been a priority. On the basis of such processual work, the research group has formulated the concept of ecocritical dialogues, which is shared and discussed in this article. Ecocritical dialogues respond to the call in educational-oriented policy documents and combine theoretical concepts from ecocriticism and dialogic teaching to develop ecocritical dialogues within teacher education.

Ecocriticism – a brief outline

The NatCul Matrix is formulated with a basis in the research field of ecocriticism, which has emerged in dialogue between multiple fields of research and practice to ponder the relationship between humanity and the natural environment. Greg Garrard (Citation2012a, 1) cites the publication of American zoologist and biologist Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring (1962) as an important forerunner of the ecocritical movement in America. Carson’s book sparked the environmental concern of literary scholars, their engagement leading eventually to the establishment of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) in 1992. Developing momentum within literature studies, the first publication to use the term ‘ecocriticism’ was William Rueckert’s ‘Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism’, originally published in 1978. Rueckert was concerned with finding a basis upon which ‘the human [and] the natural can coexist, cooperate, and flourish in the biosphere’ (1996, 107).

In 1996, Cheryll Glotfelty influentially defined ecocriticism as ‘the study of the relationship between literature and the physical world’ (xviii). Given the complex nature of this relationship, ecocriticism has since the beginning developed in a dynamic exchange between scholarship from the natural sciences and the humanist tradition. While ‘first wave’ ecocriticism (Buell Citation2005) had an emphasis on non-fictional nature writing and Romantic poetry, seeking to ‘give a voice to nature’ and to revalue nature-oriented literature, the early period was also influenced by critiques of ‘male-authored American literature, exposing the pervasive metaphor of land-as-woman’ (Glotfelty Citation1996, xxix), thus contributing to the rise of ecofeminism.

Ecocriticism has further been informed by the field of philosophy. In Europe, Arne Naess’ formulation of deep ecology in the 1970s, resulting in the deep ecology platform, argued that all life on earth has intrinsic value, regardless of human interest. Holding that ‘[r]ichness and diversity of life forms (…) are values in themselves’ and that ‘humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs’ (Naess Citation1989, 29), deep ecology stressed humans’ ethical responsibility towards other species. Both American environmentalism and the deep ecology movement were responses to industrial and technological developments that with increasing apparency were taking their toll on the natural environment. Debates on the posthuman, with feminist scholar Donna Haraway (Citation1991) and research chemist and literary scholar N. Katherine Hayles (Citation1999) as early and significant theorists, further crystalised discussions of the relationship of the human to new technologies, including an interrogation of the concept of the ‘human’. Deep ecology has since come under critique, not least by Timothy Morton (Citation2017), for positing nature as ‘other’.

A ‘second wave’ of ecocriticism included multiple genres and art forms, as well as urban landscapes and local literatures, while around the turn of the millennium, a ‘third wave’ (Slovic Citation2010) incorporated criticism of the scholarly field itself, while broadening to encompass exploration of ‘all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint’ (Adamson and Slovic Citation2009, 6–7). The debates sparked by ecocriticism and critical posthumanism have additionally been influenced by the field of animal studies (Singer Citation1975; Derrida & Wills Citation2002), which argues for the ethical rights of animals, and have contributed to the field of cultural plant studies (Hall Citation2011; Marder Citation2013; Laist Citation2013), which examines the rights and representations of plants.

As a result of the inclusion in the ‘second wave’ of ecocriticism of a wider set of local literatures, Western environmental thinking has increasingly incorporated environmental stances found in indigenous and pagan cultures, not least through the publication of Haraway’s influential Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (2016). These stances include conceptions of other species as humanity’s kinfolk or ‘kin’, a notion found for instance in Old Norse mythology, and in the Maori and Australian aboriginal traditions (Hall Citation2011). The tendency to ‘seek wisdom in Native American texts’ (Glotfelty Citation1996, xxx) has thus extended to a revaluing of other cultural configurations of the natureculture relationship than the one dominating hegemonic Western cultures since the Enlightenment.

Building on her earlier work to dismantle segmented dichotomies such as man-woman, nature-culture, and machine-human, Haraway (Citation2016) argues that humanity forms part of an intricate web of life-forms that exist and co-develop by way of ecological interdependence and through multiple forms of entanglement. In alignment with deep ecology, this position entails a realisation that human environmental conduct requires inter-thinking with, and a regard for, interspecies communities. Thus, human conduct must develop not just as a dialogue between multiple research fields but also with an awareness of the human interrelationship with other species. Or, as Rosi Braidotti (Citation2019) reminds us: ‘we-are-in-this-together-but-we-are-not-one-and-the-same’ (161).

Consequently, the formulation of ecocritical dialogues developed in this article is one that aims to open the concept of dialogue to include not only human to human verbal interaction but also the utterances of other species and matter with which we interact. This position has similarities to perspectives developed within material ecocriticism, the conceptual argument of which, according to Serenella Iovino & Serpil Oppermann, is that ‘the world’s material phenomena are knots in a vast network of agencies, which can be ‘read’ and interpreted as forming narratives, stories’ (2014, 1). Ecocritical dialogues seek to encourage practices that open their participants to networks of entangled agents and agencies.

The Nature in Culture Matrix

Based on theoretical studies and debates on ecocriticism, deep ecology, posthumanism, and material ecocriticism, the NaChiLitCul research group has engaged with some key questions that need to be addressed when developing critical thinking in education concerning human-nature relationships. The first key question regards the notion of nature. Nature might be considered a pure and harmonious place, as in the pastoral tradition (Garrard Citation2012a, 37–66). On the other hand, nature may be considered as problematic, a place where ecological imbalance, climate change, and the loss of species and plants reveal crises (Gifford Citation2014). Thus, the concept oscillates between the idyllic and the problematic. While Morton prefers to talk about ecology without reference to nature, since ‘ideas of nature (…) set people’s hearts beating and stop the thinking process’ (2007, 7), our position is rather to acknowledge the complexities inherent in the concept of nature and to tease them out in analyses.

The second main question is the positioning of the human in the ecological system. A growing ecocentric horizon with concern for all earthlings and environments makes us realise how world views and practices may be deeply anthropocentric. How do humans position themselves, and how is it possible not to be at the centre of our own projects? Thirdly, the theoretical debates point to how humans use and misuse nature through technology. The question of technology is derived from the classical rhetorical concept of techne. Here, techne is understood as the art of shaping and manufacturing: an ‘intentional crafting of self, world, and society’ (Boellstorff Citation2015, 55).

The complexity of these three entangled problem fields is not easy to grasp. One reason is its multidisciplinarity: One needs specialist competence in many scientific fields to unfold, describe, and understand this complexity. Additionally, one’s understanding of the problem field is dependent on, and challenged by, language as techne, especially as figures of thought. A figure of thought is something different from a concept. The rhetorical term ‘figure’, from Latin figura, is a collective term referring to different types of pictorial or sculptural representations (descriptive expressions) (Murfin and Ray Citation2003, 165–167). Figures are clusters of condensed thoughts. Over time, figures become part of the everyday language, influencing our actions and teaching practices. According to rhetorical theory, a figure of thought that is often used becomes a topos (pl. topoi), from Greek, meaning ‘(geometrical) place’, the term in Latin being ‘locus’ (pl. ‘loci’). Topology means places in the language, places in our reasoning. Consequently, figures of thought, or topoi, could be considered entangled agents in teaching practices aiming to facilitate students’ environmental awareness.

In a discourse, there is a difference between an opinion and a figure of thought: One may change one’s opinion, it is, however, more difficult to change one’s figures of reasoning. Although the research field of ecocriticism raises new questions, the expressions used might carry old ways of thinking. To change figures of thought, and thus deeply engage in critical thinking, one must challenge the awareness of how one uses, understands, and interacts with and through language.

Among the ruling figures of thought, as demonstrated by critical posthumanism, is describing the world in dichotomies, linked together in this kind of system: nature-culture, human-animal, organic-technical. The dichotomy is part of a structuralist way of viewing the world. In the nature-culture dichotomy, nature is seen as opposed to culture, that is, as something different from culture. For instance, one may come across ideas that humans are in culture, animals in nature. Taken further, nature is biology; culture is humanism. The concept of ‘environment’ challenges this nature-culture dichotomy. An environment is always the environment of something, it is a place, and according to James J. Gibson, this something can be any living organism (Gibson Citation2015, 4).

In order to address the entangled complexity of the problem field, taking into account main insights from ecocriticism, and at the same time working on linguistic figures in a conscious, critical, and dynamic way, the NaChiLitCul research group has developed an analytical tool, the NatCul Matrix ().

The matrix is conceived as an organic figure of thought and presents an understanding of natureculture entanglement, it is a nature in culture matrix. It takes the form of a system of coordinates in which a variety of materials can be analysed in relation to a vertical continuum ranging from a celebration to a problematisation of nature and a horizontal continuum ranging from an anthropocentric to an ecocentric horizon. The lines in the coordinate system are a way of depicting how views of nature are dependent on how humans position themselves in nature on both ontological and quotidian levels. In addition to these two axes, the matrix is circumscribed by a third dimension, that of techne.

Thus, the NatCul Matrix is a grid for the discussion of different materials, texts, and practices. Finally, the matrix is in dynamic dialogue with, and challenges, main figures of thought in the environmental discourse, making such figures of thought part of education.

Dialogue and dialogic space in teacher education

The concept ‘dialogue’ has come to us via Latin from the Greek dialogos. ‘Dia’ means ‘through’, and ‘logos’ means ‘word’, ‘speech’ or ‘reason’ (Murfin and Ray Citation2003, 238). The extensive use of the term has created many semantic nuances and ambiguities. The term therefore requires contextual definitions for particular purposes (Alexander Citation2020, 35). One of these contexts is education. Elisa Calcagni and Leonardo Lago (Citation2018, 2) suggest that in educational settings we should distinguish between ‘talk’, which refers to any verbal exchange, and ‘dialogue’, meaning talk that has particular features and educational value.

One of the most influential theorists of dialogue has been Mikhail Bakhtin. In the essay ‘The problem of speech genres’ (1929), he launches his theory of dialogism, stating that all speech is communicational. The unit of speech is the utterance. According to Bakhtin (Citation1986), all utterances are units in a complex organised chain of utterances, and these units are chained together in certain characteristic ways. Every utterance is always given as an answer to preceding utterances. Everyone who speaks is thus at the same time answering. The utterance is also connected to the following utterance in the communication, because every utterance is made in anticipation of a response. This feature is called the utterance’s addressivity. Bakhtin (Citation1986) states that ‘addressivity, the quality of turning to someone, is a constitutive feature of the utterance; without it the utterance does not and cannot exist’ (99). The addressee will on the other hand always take an active, responsive attitude. In this way, the qualities of the utterances, the way they are chained together, and the polyphonic character of the dialogues form the essence of Bakhtin’s dialogism.

Rupert Wegerif’s (Citation2007) notion of dialogic space develops this perspective further. Dialogic space is, according to Wegerif, an experiential space involving different perspectives and voices (2007 26). In this article the concept of dialogic space serves as a useful frame for the ecocritical dialogues in the entangled field described in the NatCul Matrix. Wegerif (Citation2013) states that:

When we think of dialogues, we probably think of empirical dialogues that occur at a certain place and time between particular people (…). In doing this we are looking at dialogues as if from the outside. But dialogues also have an inside. (12)

When the dialogic space is understood as an ecocritical dialogic space, ecocritical dialogues involve more than verbal utterances. The space includes a heteroglossia of different perspectives and utterances, including nonverbal utterances, perceived through bodies, actions and experiences with different materials and matter, and in nature. Dialogues in this broader, ecocritical sense thus involve interaction with the great range of nonverbal utterances in the environment.

Ecocritical dialogues is the approach we suggest can help implement critical thinking and collaboration competencies in education. The ‘critical’ part of ecocritical dialogues in the ecocritical dialogic space is to take a position in the environmental discourse. This discourse is expressed in past and contemporary texts, in modern media, and as the opinions of participants in ecocritical dialogues. The ‘collaboration’ part is stressed in Wegerif’s concept of dialogic space as the orientation towards others, or as described by UNESCO (Citation2017), to facilitate collaborative and participatory problem solving. The NatCul Matrix suggests a focus on dialogues on the common mindsets, that is, on the culturally determined ways of thinking that are embodied in generally accepted figures of thought. By collectively challenging common mindsets about what nature is, what our position in the ecological system is or could be, and what constitutes use or misuse of nature, the participants in ecocritical dialogues will explore and position themselves in the environmental discourse.

The ecocritical dialogic space in teacher education

Through practices that are dynamic, the ecocritical dialogic may develop new knowledge and can create meaning for those who participate. Teaching and institutional practices not only shape, but are themselves shaped by, cooperating cultural forces and interspecies relations, languages, spaces, and conventions.

Formation is always formation in a space – physically, geographically, culturally, socially, and cognitively (Nyrnes Citation2002). The classic premise that there is a connection between space and life underlies dialogic teaching as a formation project. Formation presupposes activity and a living interaction not only between humans and the environment, but also between all living creatures. Hopmann (Citation2007) claims that

Bildung reminds us that the meeting itself and its outcome are not embedded in the content or given by the teaching, but only emerge on site, then and there where the meeting between a particular student and a particular content happens. Then, Bildung is what remains beyond this situated engagement. (115)

Through disparate practices, education is responsible for enhancing reflectivity, both for students and teachers. Students need to be active participants and take responsibility for their own learning processes, which could be both cognitive and practical (Fassbinder Citation2012, 2). Additionally, students must develop critical awareness of learning goals and practices (Hopmann Citation2007).

Garrard (Citation2012b, 3) stresses the importance of highlighting ‘progressive pedagogy’ emphasising responsibility rather than entitlement in student-centred learning. Environmentally oriented teaching practices may be regarded as ways to understand how ecologies interact locally, regionally, and globally in cultural contexts (Gaard Citation2009, 326). It is crucial to create environmental awareness in the local sphere but also to develop global responsibility (Massey and Bradford Citation2011, 109).

Building on research projects with student teachers and with children and young adults (Høisæter Citation2019; Guanio-Uluru Citation2019; Goga and Pujol-Valls Citation2020; Sæle, Hallås, and Aadland Citation2019; Campagnaro and Goga Citation2022), the final part of this article discusses practicalities of the application of ecocritical dialogues. As noted, ecocritical dialogues incorporate the basic thinking and practices from ecocriticism and dialogic teaching. Dialogic teaching (Alexander Citation2020; Wegerif and Yang Citation2011) is linked to ideas about interthinking (Littleton and Mercer Citation2013). Concomitantly, dialogic teaching and interthinking acknowledge the heteroglossia of classroom talks and the willingness to organise the heteroglossia in non-hierarchical ways, aimed at thinking collectively and providing ‘a template for thinking alone’ (Littleton and Mercer Citation2013, 112).

To enable a non-hierarchical structure of the classroom heteroglossia, the teacher educator must think carefully about how to frame ecocritical dialogues in line with its pedagogical purpose. When the topic of the dialogue is directed by ecocritical and environmental perspectives, the teacher educator should keep in mind the connecting lines between, or the interrelational network of, the ecocritical ideas of material and interspecies entanglement, and the collective and collaborative character of dialogic teaching. Hence, ecocritical dialogues aim at combining a collaborative and collective sharing of ideas with a sensitive and responsive awareness of both the other participants of the dialogue and the larger environmental community of materials and organisms. The idea of chaining the participants’ different approaches or suggestions to a problem or dilemma (be it environmental in its character or not) could be perceived as equivalent to the ecological, ecocentric, or biosemiotic (Favareau Citation2010) idea of the interconnectedness of the world, meaning the world as it is experienced by its many organisms or components.

Ecocritical dialogic teaching is not about the degree to which the student teachers master the learning outcome as delineated in the curriculum, but rather about how they develop awareness as intended; more exactly, if and how they become environmentally aware in the given teaching process, or in the ecocritical dialogic space. Teacher educators preparing or facilitating an ecocritical dialogue designed to enhance critical thinking competency and collaborative competency, and to enable environmental awareness, need not limit the concept of dialogue to verbal utterances and could therefore include multiple non-hierarchical forms of sensory explorative exchanges between humans and the natural environment. Furthermore, ecocritical dialogues identify, evolve around, and challenge established figures of thought of nature and the environment as well as current natureculture dilemmas in the student’s own society, local as well as global.

Ecocritical dialogues as a proposed educational approach

Motivated by Alexander’s (Citation2020) idea that ‘talk that is well-structured and cognitively demanding has a direct and positive impact on student engagement and learning’ (19, our italics), we suggest in the following a set of questions to consider when preparing a well-structured, cognitively demanding, and entangled ecocritical dialogic space where ecocritical dialogues may take place. The set of questions should be perceived as a framework for setting up ecocritical dialogues, enabling educators to systematically consider the key principles of ecocritical dialogues and to develop their repertoire of techniques. Our proposed set of questions to consider when initiating ecocritical dialogues are: Where may ecocritical dialogues take place? (Location); Who may participate in ecocritical dialogues? (Participants); How may one take part in ecocritical dialogues? (Approach); What may the ecocritical dialogues be about? (Subject matter). The idea is that this repertoire of questions will be constantly shared with and developed by both peers and students. In the following sections all four features (location, participants, approach, and subject matter) will be elaborated.

Different locations contribute to the formation process, as places outside the regular classroom setting may invite new environmental meanings. Setting up ecocritical dialogic spaces may therefore require educators to expand their ideas of location. Ecocritical dialogues can take place in different physical locations, indoors and outdoors, on the educational premises and in the local environment. The external milieu may be an environment of human design, or a more or less cultivated natural setting as discussed for instance in Sæle, Hallås, and Aadland (Citation2019), where student teachers experience nature in a marine location, kayaking with peers. Such environments influence and direct ecocritical dialogues – imperceptibly for the most part, unless we choose to direct our awareness towards them. The physical locations outdoors or indoors contribute to various opportunities to concretise the ecocritical dialogues.

In an educational setting, the participants of ecocritical dialogues traditionally conceived will be teachers and their students. Often, they will be talking about a text or situation. Ecocritical dialogues challenge us to consider who else might be part of such exchanges. As humans we have the cognitive ability to focus on, or disregard, much of the information from our surrounding milieu. Our perception is guided by our mindsets, figures of thought, and psychological schema that help us determine what sources of information are relevant to particular contexts. For instance, natural spaces contain multiple critters and matter going about their own business, like birds, ant, flies, trees, grasses, and slugs. Are these too, participants in the ecocritical dialogic exchange? They may be – if we choose to include them (see SciTalk, Citationn.d.). The same goes for various material aids or technology, such as books, scissors, and computers. It is all about creating an awareness of how all critters and matter are intertwined and consequently preparing for encounters where these ways of being interconnected may be experienced. In Campagnaro and Goga (Citation2022) examples of such encounters occurred in videos created by student teachers focusing on aesthetic and material entanglements with picturebooks, peers, and the environment. The dialogic form presupposes that participants’ utterances are linked together in chains of answers and new utterances. Thus, participants from different times, spaces, and realms can participate in an ecocritical dialogue.

What specific approach might one take when constructing the ecocritical dialogic space in any educational situation? In addition to clarifying and deciding upon location and participants, one might consider how to become aware of established figures of thought and cultural figures that shape ecocritical dialogic encounters. For instance, such work was undertaken by student teachers in studies drawing on the NatCul Matrix (Guanio-Uluru Citation2019; Goga and Pujol-Valls Citation2020). Since ecocritical dialogues in a broader sense can involve not only participants’ verbal utterances but also the great range of nonverbal utterances in the environment, the utterances in an ecocritical dialogue will include chains of sensory reactions, potentially broadening the ecocritical dialogic approach. Possible tensions in an ecocritical dialogue may thus arise from different sources. It can be based on critical thinking around figures of thought, for example concerning human dominion over nature as in Høisæter (Citation2019). However, creative tension may also arise from nonverbal utterances, through sensing, handling, or exploring shapes, textures, materials, or movements in nature, experiences uncovering frictions between the participants in the dialogic situation.

A main subject matter of ecocritical dialogues is the exploration of the various interfaces between humans and the environment. In the The NatCul Matrix, this interface is represented by the dimension of techne. Techne leads us to question the technology through which we interact with our surroundings – whether through verbal language, pictorial representations, or technical tools and equipment of all kinds. For example, Gurholt (Citation2018) analyses technical mediations of nature in the Norwegian TV-series Villmarksbarna (Children of the Wilderness), and Lund (Citation2022) examines students’ verbal and visual elicitations in which they contextualise their relationship with nature.

The NatCul Matrix figuratively expresses what ecocritical dialogues are about. A main thematic field is nature: How is the concept of ‘nature’ understood? Another thematic field relates to the ways one positions oneself in the environment. These two thematic fields correspond to the two coordinates in the NatCul Matrix. The question of nature may be discussed with student teachers through reading texts, observing concrete material, and through outdoor practices. To address the question about the ways in which humans position themselves in the environment, teacher educators and student teachers might discuss whether and how they are at the centre of their own projects, and, also, whether, and in what ways, they are conscious of, and reflect on, their own positions.

Concluding remarks

The aim of this article has been to lay out the theoretical foundations of ecocritical dialogues and suggest this as an approach within teacher education. By dynamically connecting the call for new educational practices, ecocritical and posthuman perspectives, and the principles of dialogic teaching, this article has argued that ecocritical dialogues is a viable approach to create critical, relational, and collaborative encounters and entanglements with multiple environments, materials, and matter. Furthermore, it has argued that engaging in ecocritical dialogues is essential in order to be able to respond adequately to the ongoing ecological crisis, which also requires us to reconfigure our teaching practices.

While all the questions framing an ecocritical dialogue may not seem immediately relevant or suitable in all educational contexts, each question may be drawn on for inspiration independently of each other. For instance, educators may choose to focus on either subject matter, approach, participants or location, and develop their teaching practices gradually. In other words, it is not all or nothing, but a suggested set of questions that one may use to develop one’s environmental thinking and teaching in stages and by degrees. Practical applications of ecocritical dialogues within different educational contexts may for example be found in the anthology Økokritiske dialoger: innganger til arbeid med bærekraft i lærerutdanningene [Ecocritical dialogues: Working with sustainability in teacher education, Goga et al. in press]. Here, its value for the development of critical thinking and collaboration competency and the achievement of the proposed learning objectives is demonstrated.

Hopefully, in carefully laying out the theoretical foundations of ecocritical dialogues this article may contribute to reconfigurative work within current teaching practices. Alternative positions and supplementary practices are more than welcome. Alternatives and supplements will be considered creative and reflective responses to this article’s polyphonic utterance in the larger field of environmental education.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nina Goga

Nina Goga ([email protected]) is Professor of children’s literature at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Recent publications are “Material Green Entanglements: Research on Student Teachers’ Aesthetic and Ecocritical Engagement with Picturebooks of Their Own Choice” (2022, co-written with Marnie Campagnaro, in International Research in Children’s Literature), “‘I felt like a tree lost in a storm’—The Process of Entangled Knowing, Becoming, and Doing in Beatrice Alemagna’s Picturebook Un grande giorno di niente (2016) (2021, in Plants in Children’s and Young Adult Literature). ORCID 0000-0001-5658-5237.

Lykke Guanio-Uluru

Lykke Guanio-Uluru ([email protected]) is Professor of Literature at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research focus is on literature and ethics, with an emphasis on ecocriticism, fantasy fiction and game studies. She has authored Ethics and Form in Fantasy Literature: Guanio-Uluru (Citation2015) and co-edited Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues (2018) and Plants in Children’s and YA Literature (2021). Recent publications: “Analysing Plant Representation in Children’s Literature: The Phyto-Analysis Map” in Children’s Literature in Education, “Embodying Environmental Relationship: A Comparative Ecocritical Analysis of Journey and Unravel” in Ecozon@, Vol. 12, No. 2. https://ecozona.eu/article/view/3868. ORCID: 0000-0002-1056-4681.

Bjørg Oddrun Hallås

Bjørg Oddrun Hallås ([email protected]) is Professor of Physical Education, Faculty of Education, Arts and Sports, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research focus is mainly in the areas of Physical Education, Outdoor Education and on didactics and teachers’ practice. She has co-edited Nature and formation - professional practice, kindergarten and school (2015) and Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues (2018). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8870-8200.

Sissel M. Høisæter

Sissel Høisæter ([email protected]) is Professor of Rhetoric and Oral Communication at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research on oral communication has a special focus on dialogic teaching in teacher education. Her latest publication on dialogues is Høisæter, Sissel 2019. Staden som topos i ungdomskuleelevars argumentasjon. In Toril Eskeland Rangnes & Kjersti Maria Rongen Breivega (ed). 2019. Demokratisk danning i skolen. Empiriske studier. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. She has been the project manager of the Erasmus + project Natural Science Talk in Teacher Educations that in 2022 has published a learning resource on dialogic teaching https://www.hvl.no/en/collaboration/project/sci-talk/ .

Aslaug Nyrnes

Aslaug Nyrnes ([email protected]) is Professor Emerita of Didactics of Literature and Fine Art at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research focus is on the didactics of literature and art, text work in artistic research and ecocriticism. She has co-edited Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues (2018). Recent publications: “Girl and Horse as Companion Species: Horse fiction in an ecocritical perspective. Nordic Journal of ChildLit Aesthetics. No.1. (2019),” “The Nordic Winter Pastoral: A Heritage of Romanticism” in Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6611-2898

Hege Emma Rimmereide

Hege Emma Rimmereide ([email protected]) is Professor of English at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research focus ranges widely, such as ecocriticism, intercultural competence, reading and writing and visual literacy. Latest publications are: “Who will save us from the Rabbits?” – Problematizing Nature in the Anthropocene. (2018). In: Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues. Palgrave Macmillan, and “Graphic novels in the EAL classroom: a pedagogical approach based on multimodal and intercultural understandings” (2022) in Multimodality in English language learning, Routledge. Orcid-number: 0000-0002-1921-5162.

Notes

1 In an American context, Stapp et al. influentially defined environmental education in 1969 as aimed at producing a citizenry that is ‘knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems’ (34) and motivated to work towards solving such problems. ‘Man’ is by Stapp et al. defined as part of an interrelated system comprising ‘man, culture, and the biophysical environment” where “man has the ability to alter the interrelationship of this system’ (Stapp et al. Citation1969, 34). Ecocriticism, as well as the teaching approach proposed in this article, intervenes predominantly at the cultural level of the model, to help reconfigure man’s biophysical interactions.

References

- Adamson, J., and S. Slovic. 2009. “The Shoulders We Stand on: An Introduction to Ethnicity and Ecocriticism.” Melus 34 (2): 5–24.

- Alexander, R. 2020. A Dialogic Teaching Companion. London: Routledge.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1986. “The Problem of Speech Genres.” In Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, edited by C. Emerson and M. Holquist, 60–103. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bergthaller, H., R. Emmett, A. Johns-Putra, A. Kneitz, S. Lidström, S. McCorristine, I. Pérez Ramos, D. Phillips, K. Rigby, and L. Robin. 2014. “Mapping Common Ground: Ecocriticism, Environmental History, and the Environmental Humanities.” Environmental Humanities 5 (1): 261–276. doi:10.1215/22011919-3615505.

- Boellstorff, T. 2015. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Braidotti, R. 2019. Posthuman Knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Buell, L. 2005. The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Calcagni, E., and L. Lago. 2018. “The Three Domains for Dialogue: A Framework for Analysing Approaches to Teaching and Learning.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 18: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.03.001.

- Campagnaro, M., and N. Goga. 2022. “Material Green Entanglements: Research on Student Teachers’ Aesthetic and Ecocritical Engagement with Picturebooks of Their Own Choice.” International Research in Children’s Literature 15 (3): 309–323. doi:10.3366/ircl.2022.0469.

- Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Derrida, J., and D. Wills. 2002. “The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow).” Critical Inquiry 28 (2): 369–418. doi:10.1086/449046.

- Fassbinder, S. D. 2012. “Greening Education.” In Greening the Academy: Ecopedagogy through the Liberal Arts, edited by S. D. Fassbinder, R. Kahn and A. J., Nocella, 1–22. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Favareau, D. 2010. Essential Readings in Biosemiotics. Dordrecht: Springer Science.

- Gaard, G. 2009. “Children’s Environmental Literature: From Ecocriticism to Ecopedagogy.” Neohelicon 36 (2): 321–334. doi:10.1007/s11059-009-0003-7.

- Garrard, G. 2012a. Ecocriticism. London: Routledge.

- Garrard, G. 2012b. “Introduction.” In Teaching Ecocriticism and Green Cultural Studies, edited by G. Garrard, 1–10. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Gibson, J. 2015. The Ecological Approach to the Visual Perception. Classic edition. New York: Psychology Press.

- Gifford, T. 2014. “Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral, and Post-Pastoral.” In The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment, edited by L. Westling, 17–30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Glotfelty, C. 1996. “Introduction.” In The Ecocriticism Reader. Landmarks in Literary Ecology, edited by C. Glotfelty and H. Fromm, xv–xxxvii. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press.

- Goga, N., L. Guanio-Uluru, O. Hallås, and A. Nyrnes, eds. 2018. Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goga, N., L. Guanio-Uluru, K. Kleveland, and H. E. Rimmereide, eds. (in press). Økokritiske Dialoger: Innganger til Arbeid med Bærekraft i Lærerutdanningene [Ecocritical Dialogues: Working with Sustainability in Teacher Education]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Goga, N., and M. Pujol-Valls. 2020. “Ecocritical Engagement with Picturebook through Literature Conversations about Beatrice Alemagna’s On a Magical Do-Nothing Day.” Sustainability 12 (18): 7653. doi:10.3390/su12187653.

- Guanio-Uluru, L. 2015. Ethics and Form in Fantasy Literature: Tolkien, Rowling, and Meyer. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guanio-Uluru, L. 2019. “Education for Sustainability: Developing Ecocritical Literature Circles in the Student Teacher Classroom.” Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education 10 (1): 5–19. doi:10.2478/dcse-2019-0002.

- Gurholt, K. P. 2018. “The Wilderness Children: Arctic Adventures, Gender and Ecocultural Criticism.” In Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues, edited by N. Goga, L. Guanio-Uluru, O. Hallås and A. Nyrnes, 241–257. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guterres, A. 2022, 7 November. Secretary-General’s Remarks to High-Level Opening of COP27. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2022-11-07/secretary-generals-remarks-high-level-opening-of-cop27

- Hall, M. 2011. Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Haraway, D. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hayles, N. K. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Høisæter, S. 2019. “Staden Som Topos i Ungdomsskuleelevars Argumentasjon.” In Demokratisk Danning i Skolen Tverrfaglige Empiriske Studier, edited by K. M. R. Breivega and T. E. Rangnes, 94–111. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. doi:10.18261/9788215031637-2019-05.

- Hopmann, S. 2007. “Restrained Teaching: The Common Core of Didaktik.” European Educational Research Journal 6 (2): 109–124. doi:10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.109.

- Iovino, S., and S. Oppermann. 2014. “Introduction. Stories Come to Matter.” In Material Ecocriticism, edited by S. Iovino and S. Oppermann, 1–17. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Kim, M.-Y, and I. A. G. Wilkinson. 2019. “What is Dialogic Teaching? Constructing, Deconstructing and Reconstructing a Pedagogy of Classroom Talk.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 21: 70–86. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.02.003.

- Laist, R. 2013. Plants and Literature: Essays in Critical Plant Studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Littleton, K., and N. Mercer. 2013. Interthinking. Putting Talk to Work. New York: Routledge.

- Lund, T. 2022. “An Ecocritical Perspective on Friluftsliv Students’ Relationships with Nature.” Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education 6 (2): 21–36. doi:10.23865/jased.v6.3033.

- Marder, M. 2013. Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Massey, G., and C. Bradford. 2011. “Children as Ecocitizens: Ecocriticism and Environmental Texts.” In Contemporary Children’s Literature and Film, edited by K. Mallan and C. Bradford, 109–126. London: Palgrave.

- Morton, T. 2007. Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Morton, T. 2017. Humankind: Solidarity with Non-Human People. London: Verso.

- Murfin, R., and S. M. Ray. 2003. The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin.

- Naess, A. 1989. Ecology, Community and Life-Style. Translated by David Rothenberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nyrnes, A. 2002. “Det Didaktiske Rommet. Didaktisk Topologi I Ludvig Holbergs Moralske Tanker.” Doctoral thesis, University of Bergen.

- OECD. 2018a. The Future of Education and Skills. Education 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

- OECD. 2018b. Preparing our youth for an inclusive and sustainable world. The OECD PISA global competence framework. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/Handbook-PISA-2018-Global-Competence.pdf

- Rueckert, W. 1996. “Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism.” In The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology, edited by C. Glotfelty and H. Fromm, 105–123. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- SciTalk. n.d. Interactive videos. https://www.hvl.no/en/collaboration/project/sci-talk/toolbox-digital-resources/interactive-videos/

- Singer, P. 1975. Animal Liberation. Avon Books. New York: Harper Collins.

- Slovic, S. 2010. “The Third Wave of Ecocriticism: North American Reflections on the Current Phase of the Discipline.” Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture and Environment 1 (1): 4–10. doi:10.37536/ECOZONA.2010.1.1.312.

- Stapp, W. B. 1969. “The Concept of Environmental Education.” Environmental Education 1 (1): 30–31. doi:10.1080/00139254.1969.10801479.

- Sæle, O. O., B. O. Hallås, and E. K. Aadland. 2019. “Et Retroperspektiv På Lærerstudenters Friluftsliv Og Naturopphold i Skole Og Fritid – Et Antroposentrisk Fremfor Et Økosentrisk Natursyn.” Tidsskriftet Utmark 1.

- UNESCO. 2017. Education for Sustainable Development Goals Learning Objectives. UNESCO. Accessed October 26, 2020. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf

- United Nations. n.d. Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

- Wegerif, R. 2007. Dialogic Education and Technology: Expanding the Space of Learning. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Wegerif, R. 2013. Dialogic: Education for the Internet Age. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wegerif, R., and Y. Yang. 2011. “Technology and Dialogic Space: Lessons from History and from the ‘Argunaut’ and ‘Metafora’ Projects.” In Connecting Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning to Policy and Practice: CSCL2011 Conference Proceedings. Volume I—Long Papers, edited by H. Spada, G. Stahl, N. Miyake and N. Law, 312–318. Hong Kong, China: International Society of the Learning Sciences.