Abstract

This essay revisits the concept of the theatre laboratory as a site for investigating the nexus of identity and technique in practice. Informed by new materialism, critical race and gender studies, and social epistemology, it examines the materialization of racial, religious, and other identities in song-based experimental practice and shows how the act of singing can not only illustrate the complexity of contemporary identity but also effectively generate new ‘molecular’ identifications. Taking jewishness as a paradigmatic category of identity in which race, religion, nation, language, and even gender are historically intertwined, the essay responds to Santiago Slabodsky's call for ‘decolonial’ judaism as an epistemological challenge by framing an attempt to develop new jewish decolonial identity through songwork.

What is a song? Is it the pattern of notes on a page, which a singer interprets by remaining within an implicit field of limitations? Is it a reproducible audio track that captures the sonic details of a moment at a given density of samples? Is a song something that lives inside me, a piece of fractional habitus that structures my embodied self? Or is it an intersubjective passage between bodies, a pathway defined by its repeatability, a cut of transmissible knowledge?

Who owns a song? Can a song be owned? Can a song be summoned, broken, appropriated, violated, protected or honored? What happens when an academically embedded theatre laboratory works experimentally with songs as potentially volatile cultural materials? How do the identities and backgrounds of the practitioner-researchers in such a milieu interact with the meanings and connotations of those materials and with their cultural and institutional contexts?

What ethical and political guidelines can be called upon when culturally unmarked experimentalism is confronted by a cultural politics of identity, which asserts that no such process can be innocent of the power dynamics that configure the relationship between laboratory and world?

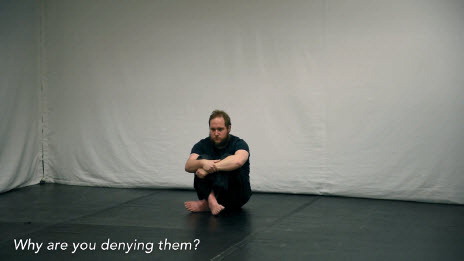

4 May 2017. I am in an empty theatre studio with white walls. It is the second day of work on a new project and I am singing a traditional Passover song. The director invites me to sing along with an imaginary community. I realize that she expects the song to evoke a sense of belonging in me. Instead, her indication brings up feelings of isolation and fear. I stop singing and sit motionless. ‘Why are you denying them?’ she asks, referring to these nameless others. ‘I don’t trust them’, I reply.Footnote1

3 August 2017. My mother is visiting the project’s studio laboratory. We bring drawing papers, pencils and charcoal into the space so that her craft as a visual artist can manifest alongside our embodied songwork. After several hours of improvised singing and drawing, a colleague and I are locked in a wordless, rhythmic melody, its intensity building through repetition. My mother’s pencil dances across the page, following our spiral vocal rhythms, no longer composing images but embodying pure play.Footnote2

8 September 2017. I stand with my two colleagues in an abandoned, ruined synagogue in rural Poland. The roofless walls are stark against a bright blue sky. A line of grey pigeons perch above, the ground covered in their faeces, bones and broken eggs. I am singing another wordless melody and holding a recent academic book about contemporary Islamophobia. Slowly I begin to sing the words of the book according to the melody of the tune, as if casting a spell to link the memory of the Holocaust with the violences of the present day.Footnote3

This article reports on the research project Judaica: Embodied Laboratory for Songwork, which revisited the concept of the theatre laboratory as a site for investigating the nexus of identity and technique in practice.Footnote4 Informed by new materialism, critical race and gender theory, and social epistemology, the Judaica project examined the materialization of identity in song-based experimental practice and attempted to demonstrate how the act of singing can not only illustrate the complexity of contemporary identity but also effectively generate new identities and identifications. Taking jewishness as a paradigmatic category of identity in which race, religion, nation, language and gender are historically intertwined, the project responded to contemporary debates over the meaning and politics of judaism today by attempting to develop new technique – ‘ways’ or ‘arts’ of being jewish (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Karp Citation2008) – through audiovisually documented experimental practice.Footnote5

The premise of the project was that cultural, religious and racial identities can be understood in part as sedimentations of embodied technique, a concept that extends prior notions like habitus and performativity to emphasize the epistemic dimension of practice (Spatz Citation2015). Outcomes of the project include written articles, live presentations and workshops, a digital archive of experimental audiovisual documents, and a series of co-authored video essays such as those glossed above. One of the key discoveries of the project was the extent to which the new availability of audio and audiovisual recording technologies has the potential to reconfigure basic onto-epistemological assumptions about knowledge and performance.Footnote6

With the exception of those brief passages above, this article stops at the laboratory door. It does not attempt to analyse specific moments of lab practice in detail, but instead focuses on a series of methodological choices that I made during the first, preparatory phase of the project. During this period, I undertook research in jewish studies, critical race studies, ethnomusicology and intellectual property studies, in order to develop a concrete research design that would allow me to pose questions about knowledge, identity, song and politics through experimental practice. The project included six months of ‘embodied laboratory research’ with a core team of three skilled practitioners working together full-time. To prepare for the lab work I had to develop a way of framing and structuring its methods and objects, which would then inform and limit the types of discoveries and outputs it could generate. In what follows, I analyse these methodological decisions as practical strategies for decolonizing both the racialized space of the academic laboratory and the racialization of jewish identity through an experimental approach to the circulation of songs across print media, digital media and embodied practice. My approach intersects with current indigenous and decolonial critiques of intellectual property law and with the rapid growth of new online media channels as a forum for the production of cultural identity in an emergent global public sphere. Taking the laboratory as a leverage point for the transformation of the world (Latour Citation1983), I first consider how racial and other identities manifest and how critical and political debates over the meaning of jewish identity can be concretized within spaces of experimental practice. I then outline the factors that contributed to my choices regarding the selection of songs and the composition of the core research team, as well as how I understood their interaction in the lab. While my discussion here refers to the period before lab research began, it is retrospectively informed by everything that took place during the laboratory phase.

WHITENESS AND NON - LEXICALITY

The fundamental methodological choice informing the Judaica project was the decision to organize laboratory-based embodied research around jewish identity and specifically jewish songs. A decade prior I had developed a series of non-lexical song cycles, each of which in various ways ‘smuggled’ musical qualities from a variety of traditions into new songs with repeatable but unrecognizable melodies and vocables: First Song Cycle and Second Song Cycle (2005–9) were generated without recording, through embodied accumulation only; the PLAYWAR songs (2009–12) were created by mapping existing songs from diverse genres onto new ‘smuggled’ versions, with different melodies and syllables; the songs in Rite of the Butcher (2010–13) were memorized from an audio recording of a single vocal improvisation session.Footnote7 I turned to non- lexicality after a period of intensive encounters with post-Grotowskian songwork practices, in particular those of the Gardzienice Centre for Theatre Practices and the Workcenter of Jerzy Grotowski and Thomas Richards (Spatz Citation2008), which inspired me to search for the intersections of personal and cultural meaning through song.Footnote8 Inventing non-lexical songs seemed to allow me to sidestep the issue of cultural appropriation and to avoid what Harry J. Elam, Jr. identifies as the ‘ethical problematics of cultural engagement’ in some post-Grotowskian songwork (Elam, Jr. 2008; see also Campbell, this volume). I discovered that, by changing the words and melody of a song, I could retain other features – such as rhythms, harmonic modes and vocal textures – without foregrounding the cultural sources of the songs. At the time, I understood this as a strategy to postpone direct engagement with cultural politics in order to explore the materiality of singing at the level of emergent embodiment. While the idea of prioritizing embodied materiality over the politics of representation is not without validity, I now also recognize it as part of what Marie Thompson has usefully identified as ‘white aurality’ (Thompson Citation2017).

Still from ‘Ancestors’, a short edited video by Ben Spatz with Nazlıhan Eda Erçin and Agnieszka Mendel; see http://bit.ly/2HQKjtB

Non-lexicality, in the narrow sense of vocal music that eschews recognizable words, is not to be associated with whiteness, as countless diverse examples attest. From yodelling to jazz scat to Hasidic nigunim, many culturally identified song traditions have developed specific and identifiable ways of working with non-lexical vocables.Footnote9 Instead, as Thompson makes clear, white aurality refers to the very concept of non-lexicality insofar as this is understood as a kind of transparent access to sonic materiality that avoids cultural reference and makes audible a pure ontology of sound. White aurality in this sense is the ‘bifurcation of materiality and meaning, sonic nature and culture’, which ‘obscures the co-constitution of “sonic ontology” and “the social”’ (Thompson Citation2017: 273). In fact, the qualities of rhythm, harmony and texture to which I referred above are no less culturally grounded than melody and lyrics, even if they are not as strictly defined or lexically specific. As the idea of ‘smuggling’ suggests, cultural reference was hidden rather than absent in these song cycles. True non-lexicality, as the absence of cultural reference, is a fantasy: a white fantasy, as Thompson shows. My engagement with non-lexicality helped me to access a space of freedom for embodied exploration at the cost of reinscribing rather than deconstructing my own whiteness. Yet this engagement, and the embodied technique it allowed me to develop, led me eventually to return to what I had initially rejected as too obvious a path: working with jewish songs.

In 2012, when I began to develop a singing practice around jewish songs, I did not realize that this would require me to interrogate the implicit whiteness of my earlier practice. I knew, however, that such a move could not be based upon an essentialized claim to jewish identity or an unproblematic definition of jewish song. Up to that point, a postponement of explicit cultural politics had seemed necessary in order to give myself the mental and emotional space to undertake an extended exploration of song as emergent embodied practice. In asking myself what it would mean to work with jewish songs, I understood myself to be inviting cultural politics back into the space of embodied research. In terms of contemporary debates, my intention was to explore the politics of identity without reducing this to what is sometimes dismissed as mere identity politics: the identification of individuals ‘in terms of positioning on a grid’ (Massumi Citation2002: 2); or identity as an ‘individualist method’ that ‘suppresses the fact that all identities are socially constructed’ and thus ‘undermines the possibility of collective self-organization’ (Haider Citation2018: 23–4). From the perspective of embodied technique and practice research, the politics of identity has less to do with categorizing individuals than with a commitment to keep issues of power and justice on the table when considering flows of culture and knowledge. A crucial question for embodied research is therefore how to understand the dynamics of intersectionality (Carastathis Citation2016; Hancock Citation2016) in moments of experimental practice, when technique and identity are inextricably bound together, simultaneously overdetermined by external forces and underdetermined within emergent action.Footnote10

The term ‘molecular’ in this context does not refer only to chemical molecules that produce identity on a biophysical level, such as DNA or testosterone. As influential as such biomedical molecules are in the contemporary construction of identity and the desire for ‘molecular revolution’, the process of ‘contaminating the molecular bases’ of identity construction cannot be limited to biomedical interventions alone (Preciado Citation2013: 234, 142). As Kim TallBear warns, with regard to DNA testing, ‘by getting caught up in molecular origin stories, we cede intellectual and moral authority to scientists’ and therefore fail to recognize the complex relationship between ‘biogenetic delineations’ of identity and ‘cultural and political delineations’ (2007: 422, 416; and see 2013). The very different ways in which testosterone and DNA circulate – mirroring differences in how we understand the construction of gender and racial identity – indicate the need to go beyond biomedical models when examining the molecularity of identity. Indeed, the fetishization of technoscientifically produced molecules can be another kind of (white/male) fantasy in which the capacity to redesign bodies at a chemically molecular level allows for the jettisoning of cultural politics with a kind of ‘vicious, amnesiac joy’ (Rosenberg Citation2014: §4). What I mean by the molecular in this context is a much broader class of embodied qualities, intensities or fragments, in which technique and identity operate together in a process of mutual construction. This idea of the molecular owes much to Deleuze’s and Guattari’s post- structuralist theories of becoming (see Saldanha and Adams Citation2013) and Foucault’s ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault Citation1988), but is inflected by more recent critical theories of race and gender that refuse to leave aside the critique of power and the call for justice when analysing the enactment of identity.

Grounded in Frantz Fanon’s phenomenology of race, the concept of molecular identity enables comparisons between different kinds of identity without ignoring their asymmetries. It is not just that race works differently from gender but that terms like ‘whiteness’, ‘blackness’, ‘jewishness’ and ‘indigeneity’ refer to overlapping and incommensurable fields of practice rather than to comparable positions on a totalizing grid. Recognizing such terms as ‘traces of history’ (Wolfe Citation2016) allows us to analyse micro interactions of technique and identity in the context of a broader historical and critical awareness. It then becomes possible to develop a ‘phenomenology of racial embodiment’ (Alcoff Citation1999) that starts from a ‘refutation of nominalism and the idea that race does not exist, or is not real’ and moves to grasp race as a ‘style of embodiment, a way of inhabiting space’ (Ahmed Citation2007: 159). However, such a phenomenology risks remaining within the domain of the descriptive. In fact, the traces of history are also the building blocks of the future. To move from phenomenology towards phenomenotechnics (Spatz Citation2017) requires a further step: theorizing ‘race as technology’ (Coleman Citation2009) or technique. This move is particularly important for embodied and artistic research because it allows us to link the descriptive phenomenology of racial embodiment to active experimentation in the technics of racialization or race tech.Footnote11 In order to get beyond an impasse whereby all descriptions of practice reify its repeated structure, we need to think as practitioners about how race is constructed and shaped at the micro level:

Could ‘race’ not be simply an object of representation and portrayal, of knowledge or truth, but also a technique that one uses, even as one is used by it – a carefully crafted, historically inflected system of tools, of mediation, or of ‘enframing’ that builds history and identity. (Chun Citation2012: 38, my emphasis)

The ‘reontologization’ (Saldanha Citation2006) of race allows us to imagine how critical and activist commitments like anti-racism could, in a moment of experimental practice, ‘become something else, experimenting with duration, sensation, resonance, and affect’ (Rai Citation2012: 64–5). The implications are significant for artistic research, where all manner of new materialisms need to be translated from theoretical frameworks into practical methods and experimental designs (Barrett and Bolt Citation2013).

The realness of identity can be felt in the impact of technique upon it, even as the apparent stability of identity emerges from the sedimentation of technique. Embodiment can be understood as a gamut between identity and technique, comprising innumerable layers moving at different speeds, from the ‘inertia’ of identity (Sedgwick Citation1995: 18) to the dynamic performativity of technique. At the level of a fragment or molecule of song, questions of intersectionality proliferate. As performing artists and specialist practitioners know, an identity is not something that one simply is but rather something that one does, resists, performs, encounters, wields, tests, transforms, adapts, adopts, rejects and innovates. Identities, in other words, are epistemic objects, not just in their statistical construction as populations, but also at the level of embodied technique. In spaces of experimental practice, it is possible to analyse, at a micro or molecular level, how identities appear, emerge, intersect, collide, shatter, coagulate, transform and vanish from one moment to another. Under the right conditions, such spaces of research can function as sources of new identities rather than merely the study of existing ones. In this sense, embodied and artistic research may have something important to contribute to broader social and materialist understandings of identity.

DECOLONIAL JUDAISM AS EPISTEMIC CHALLENGE

How then does one approach an identity as a research problem? In the case of jewishness, the debate over what and who is jewish has existed for centuries or millennia (e.g. Walzer et al. Citation2000), yet its contemporary configuration is unique. As I write this, jewish identity, Holocaust memory and the idea of anti-semitism are being weaponized by right-wing movements in both the United Kingdom and the United States – to say nothing of Israel.Footnote12 Yet the scholarly discipline of Jewish studies has been slow to situate jewishness within a broader framework of critical identity theory and politics, preferring to sustain its long-standing emphasis on ‘textual analysis and history’ in contrast to feminist, queer, black, indigenous and American studies (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Citation2005: 450). In this article, I mark a corporeal, materialist or phenomenotechnical approach to jewish identity by lower-casing the terms ‘jewish’ and ‘judaism’ throughout. If capitalization suggests the stabilization of social and institutional structures, then I take lower-casing to indicate the opposite move: ‘deactivating’ (Agamben Citation2016: 91) jewishness from a stable or coherent thing to a field of knowledge or embodied technics that can be worked experimentally. Lower-casing does not deny the social force and reality of jewishness, but indicates a shift in register from a ‘molar’ identitarian category to a phenomenotechnical or molecular level of analysis (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987: 217).Footnote13 This allows the artistic or embodied researcher to take up a consciously constructivist and actively experimental approach to what Sarah Hammerschlag calls the ‘figural’ jew or the ‘trope’ of jewishness, rejecting both universalism and particularism. If jewishness cannot be reified as an unproblematic ethnic, national or racial category founded on exclusion, neither can it be reduced to a political sign that is ‘open to anyone and everyone to take up’ (Hammerschlag Citation2010: 8–9). Instead, we can see jewishness as an ongoing field of technique, historically sedimented but still open to adaptation and redirection through embodied research. Of course, the idea that embodied acts can make substantive interventions in the construction of identity is nothing new to performance studies. Yet it still sounds bold to suggest that what we aim to accomplish in experimental practice research might involve not merely better understanding our own identifications but also inventing new ones – not (auto)ethnography but (auto)ethnotechnics.Footnote14

While the dilemma of universalism and particularism applies to every identity, it has particular urgency here because of the profound reconfiguration that the figure or trope of jewishness underwent during the twentieth century. How this historical shift is interpreted hinges on the relationship between jewishness and whiteness, where these are understood not as exclusive categories but as phenomenotechnical practices in the sense developed above. From a Eurocentric perspective, the change can be described as ‘the end of jewish modernity’, which Enzo Traverso (Citation2016) associates with an overall decrease in anti-semitism and a parallel rise in jewish neo-conservatism and Islamophobia. Within the logic of US racial politics, the same change has been analysed as a process through which European jews were gradually absorbed into the category of whiteness (Brodkin Citation1998; Levine-Rasky Citation2013: 133–41). As a result of this change, European-descended jews like myself experience white privilege while at the same time carrying a generational memory of historically recent non-whiteness. This has led to calls for such jews to reposition themselves through a ‘radical diasporism’ (Kaye/Kantrowitz Citation2007) that uses the ‘powers of diaspora’ to reject the logic of ‘territorialist nation-statism’ (Boyarin and Boyarin Citation2002), ‘parting ways’ with Zionism (Butler Citation2012) or even fully disidentifying with jewishness (Sand Citation2014). An essential contribution to the discourse of jewish repositioning is made by Santiago Slabodsky, whose call for ‘decolonial’ judaism is grounded in a hemispheric perspective that resists the implicit centring of European and US jews and draws on Latin American theories of coloniality to reclaim its historical racialization and even ‘barbarism’. Slabodsky asks: ‘If it is true that Jews have undergone a racial re-classification, can they still represent a challenge to the same structure that now welcomes them? In other words, can Jews still be a compelling source of decolonial proposals?’ For my purposes, it is significant that Slabodsky frames these questions in terms of ‘the interrelation between existential conditions and epistemological creativity’ (Slabodsky Citation2014: 30). In doing so, he implies that new answers might be found not only in the traces of historical projects such as those he examines, but also through contemporary modes of creative and generative research.

The Judaica Project, University of Huddersfield (3 August 2017); see ‘Diaspora’ (Spatz et al. Citation2018). Photo Garry Cook#

Slabodsky’s Decolonial Judaism is hardly a manifesto and even less a manual for decolonial jewish practice. It is more of a warning, in which Slabodsky surveys a range of projects – from the Frankfurt School through the writings of Emmanuel Levinas and Albert Memmi – that more or less fail to instantiate a decolonial jewish standpoint, in order to alert the reader to just how difficult such a practice might be to conceive. A related warning is given by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012), who caution that the increasingly common use of decolonization as a metaphor can weaken its political effectiveness.Footnote15 Yet according to the reontologization of race discussed above, an attempt to decolonize jewish identity through experimental practice need not be metaphorical even if it is molecular. The premise of embodied research is that technique and identity can be substantively – not metaphorically – altered through embodied research, even if this initially takes place on a micro-political scale. Given the history of the university and the laboratory as institutions of colonial research (Smith Citation2013), both must be approached with scepticism in any critically orientated project. Yet it is precisely the position of the laboratory at a scission point ‘between existential conditions and epistemological creativity’ that gives it potential leverage for innovating practice and politics. Which ingredients need to come together, and how should their encounter be structured, in order to produce what could later be analysed as fragments or molecules of decolonial judaism? What form might these particles take and how could their presence or validity be assessed? By combining the reontologization of race and identity with a decolonial approach to the figure of jewishness, we can begin to approach these as methodological issues to be answered through experimental practice.

Here then is a working definition of decolonial judaism as seen from a practical rather than historical or philosophical perspective: A decolonial jewish practice is one that takes up an identification with historically jewish materials in order to oppose a colonial project. This definition is close to Butler’s invocation of specifically ‘Jewish resources for the criticism of state violence, the colonial subjugation of populations, expulsion and dispossession’ (2012: 1), but it aims to include songs, rituals and other embodied technique within the scope of those resources/materials. By defining decolonial judaism in this way, several possibilities are opened. First, jewishness is grounded in a relationship of identification to materials historically marked as jewish, which might as easily include the works of Spinoza, Freud or Arendt as the Torah or Talmud. Second, identification is understood as complex rather than binary, allowing one to be more or less decolonially jewish, perhaps in a variety of ways, with no line in the sand marking a full transition (as in religious conversion). Third, the colonial project to which a decolonial judaism is opposed can be of any kind, from a scholarly critique of Israel to a rabbi’s solidarity at Standing Rock.Footnote16 Finally, the use of jewish technique and textuality to oppose colonial projects can take place at any level, from large-scale institutional interventions to laboratory experiments in molecular identity.

PROBLEMS IN SONGWORK : SONGS, BODIES, DOCUMENTS

A laboratory is a place where diverse elements are brought together under controlled conditions, so that their interactions can be traced and studied. In the Judaica project, songs were intended to serve as starting points for an investigation of what was initially called ‘song-action’ and later ‘songwork’. While the former term derives from the Stanislavsky/Grotowski lineage and its focus on action as the basic element of acting technique, the latter is proposed by Gary Tomlinson to describe how a set of indigenous songs in the Americas ‘opened out to touch the world’ in performance, answering to ‘a constellation of expectations concerning their expressive powers and their entailments with the non-songish things around them’. This ‘supraperformative’ level of song involves not only ‘the specific manner in which a song was presented’ but also ‘what work its performance was expected to achieve’ (Tomlinson Citation2007: 51). Songwork in this sense embraces the ‘musicking’ (Small Citation2011) of the body, a material and cultural ‘vibrational practice’ (Eidsheim Citation2015) of which literal sounding is merely an aspect. Although actual ‘work songs’ are an important reference for songwork, perhaps most clearly demonstrating the material force and utility of song (Gioia Citation2006), the ‘work’ of songwork refers to more than physical labour. Songwork here means what songs can do and in this way intersects with phenomenotechnical identity as defined above. The question of what kind of work a song can accomplish is then limited only by the constraints of experimental design: the research has to be set up so as to adequately trace the multifarious kinds of work accomplished with and by songs.

In designing the Judaica project laboratory as an institutional framework within which songs would collide with each other and with the identities of practitioner-researchers under conditions of ‘epistemological creativity’ that allowed for new molecular identities to emerge, four primary methodological questions arose:

In what form would specified songs enter the space of the laboratory?

Given the constraints of that form, which particular songs would be selected for the project?

What position would the laboratory take with regard to intellectual property rights?

Who – which bodies, which identities – would be invited into the space of the lab?

Building on the interdisciplinary, intersectional approach to jewish identity developed above, each of these questions translates a basic ontological question – What is a song? – into a matter of concrete research design.

Both for post-Grotowskian theatre laboratories and for practitioners in the ‘Natural Voice’ movement, special value has been accorded to processes in which a song is learned directly from a living teacher who is understood as having a privileged relationship of ownership or authenticity to it. In examining issues of ‘authenticity, appropriation, and ownership’ related to the global circulation of songs in such contexts, Caroline Bithell notes that ‘emphasis on oral transmission is of central significance’, not only because the interpersonal pedagogical process is valued but also because of the authenticity that a ‘native teacher’ possesses and offers (2014: 200, 18).Footnote17 Whether students make extended journeys to find such a teacher or bring one to their home country, an ethics of singing grounded in interpersonal exchange can be compared to the ethics of reciprocity that has been developed for anthropological fieldwork (Gupta and Kelly Citation2014). Within this ethical framework, attempts are made – however partial or limited – to ‘give back’ appropriately to communities and individuals who participate in research, offering various kinds of support or aid in return for knowledge. Recognizing the important ethical and sometimes political work that has been done by anthropologists and song-learners in such contexts, the idea of reciprocity continues to assume a clear division between subject and object, researcher and researched. To get a different kind of handle on the relation of song and singer, I made the choice in the Judaica project to focus on songs learned from audio recordings rather than through interpersonal exchange.Footnote18 This was done not to avoid the ethical and political dimensions of song, but to clarify these by distinguishing between moments in the research process.

Given the urgently contested nature of jewish identity, it was important to hold space for the possibility that I might disagree – perhaps radically – with an individual who ‘gave’ me a song. On the one hand, I was concerned that such gifting might create a sense of personal obligation that would interfere with the experimental process. On the other hand, I worried that interpersonal gifting could lead me to feel too much freedom, too much permission, as if one person’s gift could include unrestrained authority over a song’s tradition and potential uses. Working from recordings implements a technological and epistemological break between the moment in which a song was recorded, the moment in which I learn it, and the moment in which I bring it into a laboratory of embodied research. This approach offered a more distanced relationship to the cultural source, which I hoped could support different kinds of ‘epistemological creativity’ than a method based on ‘oral’ (interpersonal) transmission. The absence of personal responsibility to an individual teacher or transmitter helped to isolate cultural responsibility in the wider context within which digital recordings now circulate. In other words: Taking recorded songs as a starting point ensured that political issues of cultural appropriation and representation could not be reductively referred back to an ethics of interpersonal relationships, as if the potential meaning of a given song were fully owned and transferable by each authentic teacher. Instead, the question of what it meant to sing a given song would have to be resolved on its own terms, with the technological break as a premise.

For the same reason, I chose to focus upon a single digital archive with major institutional backing rather than, as I had initially expected, an eclectic mix of songs from multiple sources. After examining several different online digital archives, I selected the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings label archive as the Judaica project’s main source of songs.Footnote19 This choice offered a number of advantages. As a major institutional repository, the Folkways archive provides a reliable ‘back end’ to the project’s experimental research, ensuring that whatever materials we produced can always be compared to the source recording. This relieves the project of the obligation to adequately represent a prior version, marking a significant difference from ethnographic approaches, which often grapple with a unique responsibility that comes from being the only public record of what is shared by research participants. Additionally, the Folkways archive offers a concrete answer to the question of how to define jewish song, which can be just as indeterminate and politically charged as jewishness itself (Seroussi Citation2009). The online Folkways archive has a metadata tag in the form of the genre classification ‘Judaica’, which is attached to eighty albums (as of this writing) representing wide temporal, geographical, linguistic, cultural and functional diversity.Footnote20 Many of these albums have their own fascinating ethnographic and artistic stories, which can be found in the liner notes or through further research, and together they formed a relatively coherent and productively problematic input to the lab process. Taking the Folkways archive as a starting point for embodied research allows me to distinguish between ethnomusicological research (the recording of songs that generated the archive) and song-based embodied research (new experimental performances leading to a different kind of archive) and to put the latter, emerging field into dialogue with the former, more established discipline.

In addition to its audio content, the Folkways archive provides a clear starting point for grappling with questions of intellectual property (IP). While IP is in some ways a very limited and crudely commercial way of thinking about the ownership of songs, it is by no means static – and the ongoing debates arising from the prevalence of new media technologies are crucial for the future of embodied and artistic research. Recordings in the Folkways archive are available for use through a standard licensing agreement.Footnote21 The income from this kind of licensing goes to support Smithsonian Folkways as a non-profit organization and in some cases is also returned directly to the artists and practitioners recorded. However, these agreements apply only to the recordings, for example when used as soundtracks in a film. As the licensing page makes clear, the ‘song’ itself is understood as a separate entity, which may require separate permission from a different publisher. While much commercial music negotiates these two distinct ontologies of song with relative ease, the emphasis of Folkways on ‘folk’ music means that many of their recordings document performances of songs for which no separate rights holder exists (see Jones and Cameron Citation2005). IP law aims to establish clear rules governing who can and cannot perform a given song, but in practice there are many grey areas. In addition to gaps and contradictions within IP law, there are explicit exceptions – such as the research exception for copyright – which in some cases remain untested and therefore legally indeterminate. In a context of rapidly evolving law, artists and researchers cannot merely respond to existing law but must develop their own positions and strategies in order to influence its development.Footnote22

Today’s battles over intellectual property, including songs and other forms of ‘intangible cultural heritage’ (Taylor Citation2008), can be roughly mapped according to three main positions: first, a dominant logic of private ownership represented by the commercial music industry (Kirton in David and Halbert Citation2015: 591–2); second, an ethics of the commons, supported primarily by tech-orientated groups (e.g. Lessig Citation2004) and increasingly taken up by public institutions including universities; and third, a politics of custodianship put forward by indigenous communities (Lea Citation2008; Lai Citation2014). The commons and custodianship positions are sometimes understood as being in conflict with each other (Jones Citation2006; Calamai et al. Citation2016), but they can also be allied in creative ways against the dominant commercial position, as in Free Culture Foundation’s ‘Decolonial Media License’.Footnote23 The more glibly libertarian supporters of ‘permissionless innovation’ (Thierer Citation2014) celebrate the commons ideal without recognizing how vast differences in power and access corrupt its supposed openness.Footnote24 On the other hand, in the face of encroaching commercial ownership, Michael Peter Edson rightly argues that public institutions have a duty to ‘push the limits’ of fair use as part of their mission (2016). Rosemary Coombe suggests that a synthesis of these approaches, which attempts to build a more just media commons while at the same time holding space for marginalized voices and concerns over cultural appropriation, could be the aim of ‘dynamic fair dealing’: a practical and experimental approach to the intersections of ethics and politics, law and creativity (Coombe et al. Citation2014). By taking a clear stance on each of these facets of what a song ‘is’ – the form it takes, the particular selection and the status or indeterminacy of ownership – and then seeing what happens in an unfolding experimental process, university-based embodied and artistic research can make important contributions to the future of these debates.

Informed by these legal and ethnomusicological considerations, the choice to work with selected ‘Judaica’ albums from the Folkways archive gave me a practical and technological handle on the role of songs as research objects in the embodied laboratory. The remaining methodological question was equally essential: How to establish a core lab team whose embodied knowledge and identities would intersect with these songs in generative ways? As I grappled with Slabodsky’s decolonial challenge and came to realize that the contemporary politics of jewish identity could not be grasped outside an explicit interrogation of whiteness, I was compelled to set aside earlier Eurocentric assumptions about jewish song – grounded in the Yiddish and Hebrew heritage of my own background (cf. Kaye/Kantrowitz Citation2007: 87–104) – in favour of an approach that wrestled explicitly with the coloniality of ethnography and the problematic field of ‘world music’ (Brennan Citation2001). When the time came to recruit two researchers who would work alongside me in the Judaica project lab, I similarly realized that the separation between the professional expertise of the researchers and their embodied identities – a division upon which conventional academic research is founded – could not be maintained. In a laboratory designed to explore how songs and bodies, or technique and identity, mutually construct each other, the identities of the researchers would be no less important than those of the songs. This led me to conclude that it would be most productive to explore the potentialities of diverse recorded jewish song fragments across a set of identities that were as different from each other as possible. That is, the potential of songwork to construct identity would be best explored by a research team with diverse religious, ethnic, national and linguistic backgrounds – even if this meant that a majority would not be jewish – than by a team of researchers who shared a common link to European (Ashkenazi) judaism.

In the end – notwithstanding the predominant whiteness of European academia and the base location of the project in northern England – participants in the Judaica lab (which included, in addition to the core team, a multidisciplinary series of guests) brought with them a wide variety of national, religious, ethnic, linguistic, age, gender and other backgrounds. As a result, if unknown formations of jewish identity emerged from our practice, so too did fragments of christian, muslim and buddhist identity; molecules of queer and trans and cis gendering; and sometimes pointed shards of whiteness that sparked up from across our different relationships to the history and idea of Europe. Within this laboratory, the apparently simple act of learning and singing a song was revealed as involving innumerable layers of intersecting technique and identity. We found that even the simplest video recordings of studio practice offered abundant possibilities for critical analysis and reflection, inviting us to pore over the audiovisual ‘data’ for hours as we tried to articulate the complex entanglements between what we knew about the song being sung and what we understood to be happening in a given documented moment.

POLITICS ON THE LABORATORY FLOOR

There is an idea in science and technology studies called ‘ethics on the laboratory floor’, which calls for greater awareness among scientists of the fact that their research is inseparable from the production of technologies that may go on to radically transform the human world on a massive scale. In this regard, there is much less difference than usually assumed between a technoscience lab and the kind of lab described here. Both understand the production of knowledge as the generation of concrete possibilities for action:

On the laboratory floor, nanotechnology [cf. songwork, or race tech] is, above all, a cognitive activity mediated by technological systems and by the design of objects. Knowing through making is the ultimate goal. However, knowledge no longer comes in the form of a theoretical model representing natural phenomena. Rather, it comes as a ‘proof of concept’: the demonstration of capabilities to produce a molecular machine instantiating a process or a phenomenon. … Designing a molecule, a protein, is supposed to be the best way to understand how nature works. … [This] does not mean that nanotechnologists are investigating the intimate nature of atoms and molecules. They are interested in their performances, in what they can do, rather than in what they are made of. (Bensaude-Vincent Citation2013: 28–9, my emphasis)

This model was the basis for the Judaica lab, including its approach to ethics and politics: not to aim experimentation towards ‘pure’ theoretical or cognitive knowledge – whatever that could be – but to embed a rigorous embodied exploration of song within a critical decolonial jewish framework from the beginning. Every step of the research, from the framing of what a song ‘is’ to the choice of particular songs and bodies to bring into the laboratory space, was informed by a desire to treat singing as an embodiment of identity at the molecular level. In this way, I think we can understand the artistic research, embodied research or practice research laboratory as a site of micro-political invention, wherein the identities of the future might be crafted and the identities of the past dismantled, reshaped and reclaimed. The limits of such experimentation are defined, as with other kinds of laboratory research, by the epistemological and economic structures of academia, which at present tend to prevent experimentation in some of the most fundamental areas of technique, such as duration and kinship (Spatz Citation2018). Yet the Judaica lab, as ‘proof of concept’, showed that even something as elementary as a song can reveal striking volatility under the right conditions.

Still from ‘Działoszyce’, a video essay in progress by Nazlıhan Eda Erçin with Agnieszka Mendel and Ben Spatz.#

What is a song? Not one but many things: an audio recording, but also a video recording; memory, but also present action; individual, but also interpersonal; ethical responsibility, but also political intervention; a chunk of habitus, but also a strategy for change; technique, but also identity; identity, but also technique. This approach to songwork assumes that songs are useful and functional, but also dangerous and volatile, and that as researchers we can access these possibilities not only by watching and listening and writing about what is happening on public platforms, but also by undertaking the act of ‘singing research’ (Spatz Citation2016) as another kind of publicly orientated activity. In such research, one cannot be as circumspect or as protected as in critical theory. One has to move cautiously on from critique to affirmative and affective commitment, allowing oneself to become vulnerable through embodied action. The power of songs comes from the fact that ‘we’ and ‘they’ are ultimately made of the same stuff, which I have called technique but which sediments all the way down to the level of identity. Many social structures require us to bundle our identities together, pack them up and fold them into singular wholes. In research, our task may be to unfold, disentangle and ultimately rebuild our identities. Of course, reontologizing identities at the molecular level does not mean ignoring crucial differences between them. Some identities are heavier than others, sharper, thicker, more or less diffuse, more or less ‘sticky’ (Ahmed Citation2004: 89–92). The state of an identity may change, hardening or softening, condensing or dispersing in response to circumstances. Thinking through a molecular chemistry of identity allows us to appreciate its mobility and fragmentation without underestimating its impact. Whiteness sticks to certain bodies like a coating. Micro-aggressions fly off privileged identities like sparks, injuring those nearby. Vulnerability accrues in pools – but solidarity also amasses, crystallizes and sets off chain reactions when a critical point is reached.

As embodied researchers, we must take seriously the idea that songs and other cultural materials bring political meanings with them into the studio laboratory. There can be no escape from or exclusion of politics from that space. At the same time, we must acknowledge that the formalization and fragmentation of those materials likewise formalizes and fragments their social, cultural and political meanings. Even a small amount of material, such as a few words or notes, may be highly volatile. By the same token, a small enough quantity of even the most toxic material may be safe to handle. Working with a tiny fragment of melody, a tonal quality, a vocal colour, a rhythmic pattern or a handful of lyrics may not carry the same risk – or the same potential energy – as an entire song. The meanings of each aspect of a song must be tested separately, with unlimited complexities to be discovered within even the tiniest bits of technique. If we were to say that we can know in advance what can and cannot be done with certain materials, or by certain people, we would void the possibility of embodied research. If there is such a thing as embodied research, and if sustained practice can generate new knowledge and new possibilities, that can only be because the emergent properties and meanings of practice are fundamentally unpredictable. Avoiding cultural appropriation cannot be a matter of reinforcing disciplinary hierarchies, such as those that grant history and theory authority over song and movement. Instead, intersectionality at the micro level is about figuring out, through careful and rigorous experimentation, what responsibilities, relations and commitments are produced by which configurations of songs and bodies, actions and affects, technique and identity.

The question for embodied and artistic research is then twofold: First, how to produce uncommon deconstructions, fragmentations, collisions and recombinations of identity in practice? How to reveal and unfold, unbundle and open up the molecular flows of identity, in order to recombine them in new ways? And second, how to create a trace or document of these collisions and recombinations, so that they can be analysed and shared?Footnote25 Performing and embodied arts have always been a site for the former. As Katherine Profeta observes, ‘because the physical body and its techniques are never abstract, but rather ineluctably located within a historical moment and a cultural/political system, any confrontation between two or more physical techniques has unavoidable historical and political resonances’ (Profeta Citation2015:204). The specific task of artistic and embodied research today is then related to the second task: the transcription of this process into more adequate forms of document. In that sense, this article is only a prelude to the audiovisual works that explicate what took place inside the Judaica lab in ways that are permanently inaccessible to the medium of writing. But we underestimate embodied research if we fail to treat choices about what and who enters the lab with full critical and epistemological rigour. Here I have concentrated on the methodological framework that supported the Judaica project laboratory in 2017. I hope I have offered the beginnings of a methodology that recognizes the inextricability of technique and identity in songwork and, more generally, in practice. With this it should be possible to undertake a new kind of research.

Notes

1 This moment is traced in ‘Ancestors’ (3:30), a short edited video by Ben Spatz with Nazlıhan Eda Erçin and Agnieszka Mendel, http://bit.ly/2HQKjtB

(fig. 1).

2 This moment is traced in the final section of ‘Diaspora’ (Spatz et al. Citation2018); also available at http://bit.ly/2V2FOyK (fig. 2).

3 This moment is traced in ‘Działoszyce’, a video essay by Nazlıhan Eda Erçin with Agnieszka Mendel and Ben Spatz. ‘Działoszyce’ is a work in progress, which has been shown at several public events but is not yet available online. The book is Hage (Citation2017) (fig. 3).

4 The Judaica project was supported by a Leadership Fellow award from the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (2016–18). This article is indebted to Nazlıhan Eda Erçin and Agnieszka Mendel, who were full-time researchers on the project from May to October 2017; as well as to anthropologist and performer Caroline Gatt and other collaborators. The question ‘Who owns a song?’ was proposed by Erçin; she has also written about the project (Erçin Citation2018). Open access for this article is provided by University of Huddersfield. Thanks to Santiago Slabodsky for comments on an earlier draft.

5 My decision to lower-case ‘jewish’ throughout this article is explained below.

6 For examples of the emerging form of the scholarly video essay in media studies as well as embodied research, see the online journals [in]Transition (http:// mediacommons.org/ intransition/), Screenworks (http://screenworks.org. uk/) and The Journal of Embodied Research (https:// jer.openlibhums.org/), which I edit.

7 For more on these song cycles, see the Urban Research Theater website: www. urbanresearchtheater.com.

8 I use ‘post-Grotowskian’ in the sense that

Hans-Thies Lehmann defines the post-Brechtian: ‘not a theatre that has nothing to do with [Grotowski] but a theatre which knows that it is affected by the demands and questions for theatre that are sedimented in [Grotowski]’s work but can no longer accept [Grotowski]’s answers’ (2006: 27).

9 The Wikipedia entry for ‘Non-lexical vocables in music’ contains a useful survey of these: http://bit.ly/2TLqQMo (accessed 8 February 2019).

10 Many of the issues of figurality, trope and ‘race tech’ discussed here in relation to jewishness are being explored with the greatest vision, urgency and courage in contemporary black feminist studies and theories of blackness. The concept of intersectionality was proposed by Kimberle Crenshaw (Citation1989), while identity politics was first formulated by the Combahee River Collective (Citation1982). Current black studies tends towards radically politicized deconstruction (e.g. Ferreira da Silva Citation2007; Weheliye Citation2014; Wright Citation2015). For a range of accessible takes on race in the United States, see Rankine (Citation2015). For attempts to grasp black and jewish figurality together, see Mirzoeff (Citation2000) and Rothberg (Citation2009). For molecular blackness in dance as embodied research, see Profeta (Citation2015).

11 Distinctive geographical and epistemological connotations attend the terms ‘artistic research’, ‘practice research’, ‘performance (as) research’, ‘research-creation’, etc. My use of ‘embodied research’ is intended to foreground embodiment and embodied practice as a distinctive ethical and epistemological standpoint that is sometimes lost in broader notions of practice and performance. Regarding race as technology: Theresa de Lauretis wrote much earlier of ‘technologies of gender’ (1987), but this seems to refer to technology in the standard sense (e.g. cinema) rather than to gender itself as technique/ technology. For more recent work on gender ‘tech’ in the latter sense, see Spatz (Citation2015: 170–214); Gill-Peterson (Citation2014: 409– 12); and the journal Somatechnics.

12 I hardly need to cite recent news articles to invoke current debates over anti-semitism, Zionism and jewish identity in these countries. On the meaning and uses of anti-semitism in contemporary politics, see Jewish Voice for Peace (Citation2017).

13 I do not maintain a substantive difference between judaism and jewishness. Historically these terms have been used to distinguish religious from ethno-racial technique, but that distinction falls apart at the level of phenomenotechique and experimental practice. While race ‘is not a comfortable topic for Jews and Jewish studies’ working on either side of the twentieth century, the contemporary politics of jewish identity cannot seriously be explored without dealing with race (Tessman and Bar On 2001: 7; Kaye/Kantrowitz Citation2007; Sicher Citation2013). For a historical precedent lower-casing jewishness, see Lyotard (Citation1990). Compare also with arguments for and against upper-casing/capitalizing ‘Black’ (Mahoney Citation1992: 218, n. 7; Tharps Citation2014) and ‘Indigenous’ (Wilson Citation2008: 15).

14 Drawing on Derrida’s engagement with his own jewishness, Hammerschlag identifies such postpositivist modes of (dis) identification as a function of ‘literature’ – that is, of creative practice: ‘Derrida makes the performance of his relation to Judaism meaningful and productive by making it a literary performance that dramatizes its paradoxes. In the process, the performance itself develops a political valence. What differentiates his position from Levinas’s is his use of the as if’ (2010: 258–9). The unintended resonance here with Stanislavsky’s ‘magic “if”’ (Stanislavsky Citation2010: 60) signals the extent to which figural identity is open to intervention through performative and embodied means.

15 Tuck and Yang argue against the use of decolonization as a metaphor removed from direct political action for the transfer of land sovereignty. However, in the broader context of the Americas and beyond, ‘decoloniality’ remains a key term. Complementing Tuck’s and Yang’s position, Walter Mignolo warns of the ‘coloniality without colonialism’ that can emerge when decolonization focuses only on land and sovereignty without a parallel epistemic transformation (Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018: 234). I agree that decolonial judaism must be centrally concerned with land-based sovereignty – especially the rights of Palestinians and the complementary politics of diasporic (rather than nationalist) judaism. This does not mean, however, that more narrowly focused academic and artistic projects cannot be decolonial.

16 For the latter, see Rabbi Susan Goldberg (Citation2016). For a range of creative, justice-orientated interpretations of Torah, see Jewschool’s ‘Top Ten Social Justice Haggadahs and Supplements’. The Haggadah is a book that guides the retelling of the Exodus story on Passover: ‘This year’s newcomers include [a] #BlackLivesMatter haggadah, one for a socially responsible cocoa, Bend the Arc’s 50th anniversary of Selma, and another about the Palestinian Nakba’ (2015).

17 An anecdote related by Thomas Richards illustrates both the moral, almost religious force of Grotowski’s assumed preference for ‘direct’ transmission and the latter’s willingness to transgress his own boundaries. Richards, referring to a newly learned song: ‘But … it’s not orthodox, I just learned it from a record.’ Grotowski: ‘Please Thomas … don’t be ashamed’ (Richards Citation2008:44, and see 61–3).

18 I began the Judaica project in 2012 by learning songs in person from practitioners like Rebecca Joy Fletcher (www.rebeccajoyfletcher.com) and Joey Weisenberg (joeyweisenberg.com; see Weisenberg Citation2011), who actively bridge religious training and performing arts. Gradually I moved away from this approach.

19 The Folkways archive (folkways.si.edu/) contains the most diverse collection of songs marked ‘jewish’ of any online database I have found, with the exception of the Israeli website Invitation to Piyut (old. piyut.org.il/english). The latter offers a dizzying array of recordings, but without reading Hebrew I did not feel able to navigate either its musicological or its political complexities. I also explored the Recorded Sound Archives at Florida Atlantic University (rsa.fau. edu) and the website of the international organization Chabad (www.chabad.org). Songs from each of these sources were explored during earlier phases of the Judaica project.

20 ‘Judaica’ usually refers to physical artefacts, such as books and ritual objects. In this project, and in the Folkways archive, it suggests a materialist approach to songs as cultural objects. My initial idea had been to focus on Hebrew piyutim and Hasidic nigunim as two key forms of jewish song, but this fell apart as I discovered that both categories were too musically vague and culturally narrow to serve my aims. A list of songs selected for the Judaica project since 2012 can be found here: http://bit.ly/2Wwx1po

21 The licensing agreement can be found here: https://s.si.edu/2Otr8GF, last accessed 8 February 2019.

22 For related investigations of intellectual property in dance, see Kraut (Citation2016) and the work of the Centre for Dance Research (C-DaRE) at Coventry University. I discussed the legally untested aspects of recent UK copyright law changes with Charlotte Waelde, Professor of Intellectual Property Law at Coventry University, in early 2017.

23 See http://bit.ly/2XlEQyD last accessed 8 February 2019.

24 Nate Harrison, a photographer who works extensively with copyright law, has commented that ‘one of the conventional narratives in the debates over IP – that of the “corporate Goliath” against the “little David” isn’t quite so simple. There are plenty of little Davids out there … who are vociferous in protecting their copyrights/private property. If they don’t, they literally starve (unlike the sDisneys of the world who make millions despite piracy because, in light of the ease of copying, they have found new revenue streams to exploit)’ (personal communication, 26 July 2018).

25 During the Judaica project, a more precise and rigorously elaborated solution to this pair of questions appeared in the form of a new experimental embodied audiovisual research method, which I call Dynamic Configurations with Transversal Video (DCTV). The details of this new method are explained in Spatz (Citationforthcoming).

REFERENCES

- Agamben, Giorgio (2016) The Use of Bodies, trans. Adam Kotsko, Meridian Crossing Aesthetics, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara (2004) The Cultural Politics of Emotion, New York: Routledge.

- Ahmed, Sara (2007) ‘A phenomenology of whiteness’, Feminist Theory 8(2): 149–68. doi: 10.1177/1464700107078139

- Alcoff, Linda Martin (1999) ‘Towards a phenomenology of racial embodiment’, Radical Philosophy 95: 15–26.

- Barrett, Estelle, and Barbara Bolt, eds. (2013) Carnal Knowledge: Towards a ‘New Materialism’ through the arts, London and New York: I. B. Tauris.

- Bensaude-Vincent, Bernadette (2013) ‘Which focus for an ethics in nanotechnology laboratories?’, in Simone van der Burg and Tsjalling Swierstra (eds) Ethics on the Laboratory Floor, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 21–37.

- Bithell, Caroline (2014) A Different Voice, A Different Song: Reclaiming community through the natural voice and world song, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boyarin, Jonathan, and Daniel Boyarin (2002) Powers of Diaspora: Two essays on the relevance of Jewish culture, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Brennan, Timothy (2001) ‘World music does not exist’, Discourse 21(1): 44–62.

- Brodkin, Karen (1998) How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says About Race in America, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Butler, Judith (2012) Parting Ways: Jewishness and the Critique of Zionism, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Calamai, Silvia, Veronique Ginouvès and Pier Marco Bertinetto (2016) ‘Sound archives accessibility’, in Karol Jan Borowiecki, Neil Forbes, and Antonella Fresa (eds) Cultural Heritage in a Changing World, Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, pp. 37–54.

- Carastathis, Anna (2016) Intersectionality: Origins, contestations, horizons, (Expanding Frontiers: Interdisciplinary approaches to studies of women, gender, and sexuality), Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong (2012) ‘Race and/as technology, or how to do things to race’, in Lisa Nakamura and Peter A. Chow-White (eds) Race After the Internet, New York and London: Routledge, pp. 38–60.

- Coleman, Beth (2009) ‘Race as technology’, Camera Obscura 24(1(70)): 177–207. doi: 10.1215/02705346-2008-018

- Combahee River Collective (1982) ‘A Black feminist statement’, in Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott and Barbara Smith (eds) All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black women’s studies, New York: Feminist Press, pp. 210–18.

- Coombe, Rosemary J., Darren Wershler and Martin Zeilinger, eds. (2014) Dynamic Fair Dealing: Creating Canadian culture online, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle (1989) ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’, University of Chicago Legal Forum 1: 139–67.

- David, Matthew, and Debora J Halbert, eds. (2015) The SAGE Handbook of Intellectual Property, London, UK: SAGE Publications

- De Lauretis, Teresa (1987) Technologies of Gender: Essays on theory, film, and fiction, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Edson, Michael Peter (2016) ‘Dark matter: The role of the internet in society and the future of memory institution’, paper presented at ‘Jewish Cultural Heritage. Projects, Methods, Inspirations’ conference, at POLIN, The Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw, 8–10 June.

- Eidsheim, Nina Sun (2015) Sensing Sound: Singing and listening as vibrational practice, Sign, Storage, Transmission, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Elam, Jr., Harry J. (2008) ‘Fathers and sons’, TDR: The Drama Review 52(2): 2–3. doi: 10.1162/dram.2008.52.2.2

- Erçin, Nazlıhan Eda (2018) ‘From-ness: The identity of the practitioner in the laboratory’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies 3(2): 195–202. doi: 10.1386/jivs.3.2.195_1

- Ferreira da Silva, Denise (2007) Toward a Global Idea of Race, Borderlines 27, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Foucault, Michel (1988) Technologies of the Self: A seminar with Michel Foucault, eds Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Gill-Peterson, Julian (2014) ‘The technical capacities of the body: Assembling race, technology, and transgender’, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1(3): 402–18. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2685660

- Gioia, Ted (2006) Work Songs, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Goldberg, Susan (2016) ‘A rabbi at Standing Rock’, Jewish Journal, 29 November, http://jewishjournalopinion/212926/, last accessed 8 February 2019.

- Gupta, Clare, and Alice Bridget Kelly, eds. (2014) Giving Back in Field Research, special issue of the Journal of Research Practice 10(2).

- Hage, Ghassan (2017) Is Racism an Environmental Threat?, Debating Race, Malden, MA: Polity.

- Haider, Asad (2018) Mistaken Identity: Race and class in the age of Trump, London and Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

- Hammerschlag, Sarah (2010) The Figural Jew: Politics and identity in postwar French thought, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hancock, Ange-Marie (2016) Intersectionality: An intellectual history, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jewish Voice for Peace, ed. (2017) On Antisemitism: Solidarity and the struggle for justice, Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

- Jewschool (2015) ‘2015’s top ten social justice haggadahs & supplements’, Keshet Press. http://bit.ly/2TIl0Ln

- Jones, Richard (2006) ‘(Don’t) stop the cavalry: Traditional music, intellectual property, globalisation and the internet’, paper presented at 21st BILETA Conference, Globalisation and Harmonisation in Technology Law, Malta, April, www.bileta.ac.uk/content/files/conference%20papers/2006

- Jones, Richard, and Euan Cameron (2005) ‘Full fat, semi- skimmed or no milk today – Creative Commons licences and English folk music’, Review of Law, Computers & Technology 19(3): 259–75. doi: 10.1080/13600860500348143

- Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie (2007) The Colors of Jews: Racial politics and radical diasporism, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara (2005) ‘The corporeal turn’, Jewish Studies Quarterly 95(3): 447–61.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara, and Jonathan Karp, eds. (2008) The Art of Being Jewish in Modern Times, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Kraut, Anthea (2016) Choreographing Copyright: Race, gender, and intellectual property rights in American dance, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lai, Jessica C. (2014) Indigenous Cultural Heritage and Intellectual Property Rights: Learning from the New Zealand experience? Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Latour, Bruno (1983) ‘Give me a laboratory and I will raise the world’, in Karin Knorr-Cetina and Michael Mulkay (eds) Science Observed: Perspectives on the Social Study of Science, London: Sage Publications, pp. 141–70.

- Lea, David (2008) Property Rights, Indigenous People and the Developing World: Issues from aboriginal entitlement to intellectual ownership rights, Leiden: BRILL.

- Lehmann, Hans-Thies (2006) Postdramatic Theatre, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lessig, Lawrence (2004) Free Culture: The nature and future of creativity, New York: Penguin Press.

- Levine-Rasky, Cynthia (2013) Whiteness Fractured, Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

- Lyotard, Jean François (1990) Heidegger and “the Jews”. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mahoney, Martha R. 1992. ‘Whiteness and Women, In Practice and Theory: A Reply To Catharine MacKinnon’. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 5 (2): 217–51.

- Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Post-Contemporary Interventions. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas, ed. 2000. Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews. London and New York: Routledge.

- Preciado, Beatriz. 2013. Testo Junkie: Sex, drugs, and biopolitics in the pharmacopornographic era. The Feminist Press at CUNY.

- Profeta, Katherine. 2015. Dramaturgy in Motion At Work on Dance and Movement Performance. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Rai, Amit S. 2012. “Race Racing: Four Theses on Race and Intensity.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 40 (1–2): 64–75. doi: 10.1353/wsq.2012.0018

- Rankine, Claudia, ed. 2015) The Racial Imaginary: Writers on race in the life of the mind, 1st edn, Albany, NY: Fence Books.

- Richards, Thomas (2008) Heart of Practice: Within the Workcenter of Jerzy Grotowski and Thomas Richards, London and New York: Routledge.

- Rosenberg, Jordana (2014) ‘The molecularization of sexuality: On some primitivisms of the present’, Theory & Event 17(2).

- Rothberg, Michael (2009) Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the age of decolonization, Cultural Memory in the Present, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Saldanha, Arun (2006) ‘Reontologising race: The machinic geography of phenotype’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24: 9–24. doi: 10.1068/d61j

- Saldanha, Arun, and Jason Michael Adams, eds. (2013) Deleuze and Race, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Sand, Shlomo (2014) How I Stopped Being a Jew, London and New York: Verso.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1995) ‘”Gosh, Boy George, you must be awfully secure in your masculinity!”‘ in Maurice Berger, Brian Wallis and Simon Watson (eds) Constructing Masculinity, New York: Routledge, pp. 11–20.

- Seroussi, Edwin (2009) ‘Music: The “Jew” of Jewish Studies’, Jewish Studies: Journal of the World Congress of Jewish Studies 46: 3–84.

- Sicher, Efraim, ed. (2013) Race, Color, Identity: Rethinking discourses about ‘Jews’ in the twenty-first century, New York: Berghahn Books.

- Slabodsky, Santiago (2014) Decolonial Judaism: Triumphal failures of barbaric thinking. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Small, Christopher G. (2011) Musicking, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2013) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples, London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Spatz, Ben (2008) ‘To open a person: Song and encounter at Gardzienice and the Workcenter’, Theatre Topics 18(2): 205–22. doi: 10.1353/tt.0.0044

- Spatz, Ben (2015) What a Body Can Do: Technique as knowledge, practice as research. London and New York: Routledge.

- Spatz, Ben (2016) ‘Singing research: Judaica 1 at the British Library’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies 1(2): 161–72. doi: 10.1386/jivs.1.2.161_1

- Spatz, Ben (2017) ‘Colors like knives: Embodied research and phenomenotechnique in Rite of the Butcher’, Contemporary Theatre Review 27(2): 195–215.

- Spatz, Ben (2018) ‘Mad lab – or why we can’t do practice as research’, in Annette Arlander, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude, and Ben Spatz (eds) Performance as Research: Knowledge, methods, impact, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 209–23.

- Spatz, Ben (forthcoming) Making a Laboratory: Dynamic configurations with transversal video, New York: Punctum Books.

- Spatz, Ben, Nazlıhan Eda Erçin, Agnieszka Mendel and Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz (2018) ‘Diaspora (an illuminated video essay)’, Global Performance Studies 2(1), http://bit.ly/2Gi1m5C, last accessed 8 February 2019.

- Stanislavsky, Konstantin (2010) An Actor’s Work: A student’s diary, trans. Jean Benedetti, London: Routledge.

- TallBear, Kim (2007) ‘Narratives of race and indigeneity in the genographic project’, Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 35(3): 412–24.

- TallBear, Kimberly (2013) Native American DNA: Tribal belonging and the false promise of genetic science, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Taylor, Diana (2008) ‘Performance and intangible cultural heritage’, in Tracy C. Davis (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Performance Studies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 91–104.

- Tessman, Lisa, and Bat-Ami Bar On (2001) Jewish Locations: Traversing racialized landscapes, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Tharps, Lori L. (2014) ‘The case for Black with a capital B’, The New York Times, 18 November.

- Thierer, Adam D. (2014) Permissionless Innovation: The continuing case for comprehensive technological freedom, Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center, George Mason University.

- Thompson, Marie (2017) ‘Whiteness and the ontological turn in sound studies’, Parallax 23(3): 266–82. doi: 10.1080/13534645.2017.1339967

- Tomlinson, Gary (2007) The Singing of the New World: Indigenous voice in the era of European contact, New Perspectives in Music History and Criticism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Traverso, Enzo (2016) The End of Jewish Modernity, London: Pluto Press.

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang (2012) ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1): 1–40.

- Walzer, Michael, Menachem Lorberbaum, No’am Zohar, Yair Lorberbaum and Ari Ackerman, eds. (2000) The Jewish Political Tradition, Vol. 2: Membership, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Weheliye, Alexander G. (2014) Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Weisenberg, Joey (2011) Building Singing Communities: A practical guide to unlocking the power of music in Jewish prayer, New York: Mechon Hadar.

- Wilson, Shawn (2008) Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous research methods, Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

- Wolfe, Patrick (2016) Traces of History: Elementary structures of race, London and New York: Verso.

- Wright, Michelle M. (2015) Physics of Blackness: Beyond the middle passage epistemology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.