Abstract

For many working in old European theatres, like the few remaining Victorian theatres in the UK, the understage space is nicknamed ‘Hell’. It is a term that is becoming less common as understage spaces fall into disuse and is absent in theatres without an understage at all. The space beneath the stage has always been important technologically and scenographically, but its less well-documented associations with an infernal underworld have a cultural resonance that reaches far beyond the history of the Victorian wood stage. This article explores the idea of the understage as a space that, even when it is not present, has an important aesthetic role in the theatre with cultural and historical precedents to be found in ancient Greek, medieval and Elizabethan theatres as well as Japanese Kabuki. In theatre, ‘Hell’ is the space that sits between the materiality of a technical theatre history and the experience of scenography. It is a persistent theatrical reminder that whatever is shown to an audience is also masking something. This article explores the history of the origin of this space and how the acceptance and rejection of its presence have shaped and influenced theatre theory and performance for centuries.

There is something quietly thrilling about waiting beneath a stage during a performance. It’s unlike waiting in the wings or behind the black serge of a studio waiting to enter from the space that is inevitable but ignored: from the imagined immensity of backstage. This is waiting under the stage, beneath the playing area in an old theatre space. The muffled voices of the actors and the quiet drone of the audience. The sharp wooden thuds of footfall overhead like the drumming of fingers on a guitar belly. It feels magical as you wait for your cue. It did not feel like ‘Hell’, but that was how it was introduced to me by my stage manager when starting as a stage technician in the early 2000s in a ‘new’ theatre from the 1970s. He had started as a boy in a much older theatre. It had been demolished but that theatre had traps and old stage machinery in its ‘Hell’: the place you go down to or come up from, because it is beneath the stage.

The theatre I worked in was ‘empty’ in that it had no machinery for performance but was crammed instead, with chairs, tables, rostra and music stands; a double screw-jack lift for the orchestra pit, lighting equipment (years out of date) and larger props too precious or difficult to rebuild. There were no traps and no stage devices.

In that guitar belly sounding board of the theatre there was no suggestion that you could enter or leave through the ceiling to the performance space above. Nevertheless this was ‘Hell’, or under-the-stage. Years later the term dessous, French for ‘underneath’, seemed to me a romantic way of linking the stages of the past with that one because it was what old books used. It was only some time later in another theatre during pantomime season that the trap used to put King Rat upon the stage was called a ‘demon trap’ by another stage manager and that made sense of why the understage might be named ‘Hell’. The term did not match the aesthetic of a modern theatre, the carpet and carefully spaced seating, the signage and branding, nor did it match the space itself and, aside from that one device, what was there that was infernal about it? The understage could be spooky when the theatre was dark, but it was not hellish, and yet the name suggests something much larger at play than just a nickname.

This article explores the idea of understage as a space that, even when it is not present, has an important aesthetic role in the theatre. ‘Hell’ is a space that sits between the materiality of a technical history and the experience of scenography. The article examines the shifting point in stage presentation during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to help map out how this space and the technologies associated with it shifted their meanings and lost their connotations.

‘The stage’, as Ray Johnson claims, ‘has always been hollow; the space below is referred to as the “hell”—in other words, that is where you went down to if you met your judgement in a play’ (2007: 159). Quite where Johnson obtained this association from is unclear—the understage is not referred to as ‘Hell’ by Percy Fitzgerald, in The World Behind the Scenes(1881), the most complete account of the technical theatre in English from the nineteenth century. In French theatre, Georges Moynet’s 1893 work Trucs et Décors and the earlier work L’Envers du Théatre from J. Moynet (1874)Footnote1 also do not refer to it as such, neither does E. H. Laumann’s 1897 La Machinerie au Théatre. Richard Southern’s twentieth-century and very thorough English-language work from 1951 Changeable Scenery also does not refer to the understage as ‘Hell’, while for Phillip Butterworth in his excellent exploration of stage pyrotechnics, The Theatre of Fire (1998), ‘Hell’ is a pyrotechnical concern and not a scenographic or spatial one.

Nothing, in fact, confirms that the understage was known as ‘Hell’ during the nineteenth century. And yet, it scenographically was ‘Hell’: demons, sprites and all manner of ghosts enter to the stage from that direction (Urban Citation2019), from the huge void below into which you go down .

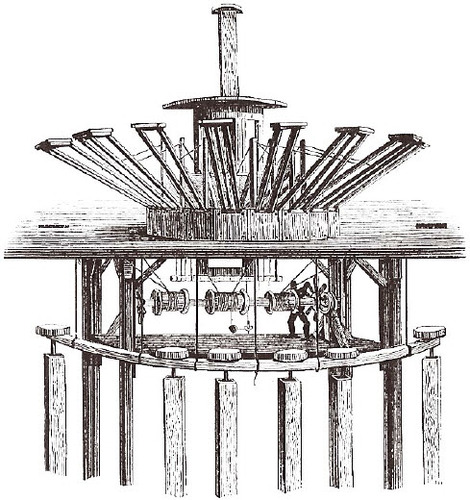

Now named after its architect, Charles Garnier (1825–1898), the Palais Garnier in Paris was constructed as the National Opera House in 1875 and is currently home to Opéra National de Paris. Its proximity to the River Seine and its tributaries meant that Garnier needed to construct it on very deep, raised foundations. Unlike other theatres that require an understage the cellar floor is not a gravel or sand pit (also known as les sablières; Moynet Citation1893 : 29) but a flooded catacomb (Sachs Citation1968 [1896]: 4). Inspired by this dark labyrinth and by rumours of a ghost, Gaston Leroux set his 1910 novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra in this very opera house, the eponymous phantom haunting those same catacombs. Palais Garnier was considered to be one of the finest European theatres and was very influential upon the theatres of London in the late nineteenth century (Fitzgerald Citation1881: 18, 93, 107). This was both in terms of architectural style and in terms of a commitment to stage spectacle achieved through mechanical means thanks, in part, to its vast understage space: 22 metres deep according to Edwin O. Sachs (1968: 4). Such understage depth allowed for the use of spectacular machines and stage devices such as the Parallèle (), for which J. Moynet provides a fleeting description in L’Envers du Théatre (1972 [1874]: 100–2). It was a device for the climax of a faery presentation, an arrangement of entertainment that established a spectacular tableau of scenery and figures set to music. This would form part of an inter-act between plays, or as part of a Grand Opera presentation, or in the programme of an entertainment. In most cases they were spectrally, or supernaturally themed, hence ‘faery’ presentation.

In the case of the Parallèle, nine platforms, each holding a performer, rise up from underneath the stage, so it looks like the figures are in a close group on a tower. The group then splits as the platforms they are standing on fan outwards from the centre. As they do so, five more performers are revealed in the centre on a different platform, then a final platform rises up with a single performer on the crowning level. All figures are fabulously costumed. The nine platforms are counterweighted, and, when released, their outward arc acts as a lever for the top platform to rise. Inside the first tower is a stagehand who rises up with the tower and controls the descent of the nine platforms that fan out. Moynet gives some pointers (1874: 102) in his description on how to complete the look of this action, suggesting an extra six performers coming up through other stage traps to fill the gaps between the platforms while the audience is dazzled with some very bright electric lights and Bengal flames—these are the big flamethrower-style fireworks seen in large sporting events today.

‘Hell’ is gone, but not forgotten, in Western theatre performance. The addition of belching fire, to the emergence of pagan entities from underneath a stage known to be an especially deep and dark catacomb, is particularly infernal despite theatrical commentators from the period not mentioning it. There may not be reference to the understage space specifically being called ‘Hell’ in the nineteenth century, but there are other scenographic precedents to consider. So where did it come from and where did it go?

EARLY THEATRICAL ‘HELLS’

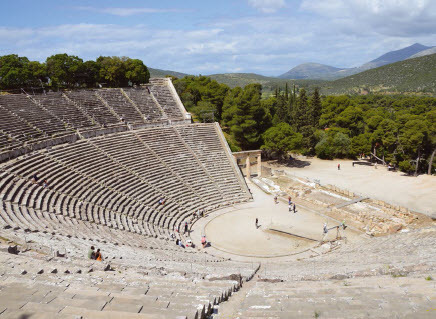

The classical Greek theatre is remarkably inconsistent in how it is depicted in stage drawings, mainly due to there being a large range of extant ruins of different sizes, locations and ages.Footnote2 The introductory drawing of a Greek theatre is usually a representation based on the design recognized from Epidaurus in Athens, Greece: a large circular orchestra of earthen floor or stone, the playing space, with a fan of tiered arena seating on one side opposite the proskenion, a building usually in ruins but once presumed to contain a raised platform to the rear of the orchestra away from the audience that acted as a playing space ().

Figure 2. The great theatre of Epidaurus, designed by Polykleitos the Younger in the fourth century BCE, Sanctuary of Asklepeios at Epidaurus, Greece, by Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany. CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons. wikimedia.org/w/index. php?curid=37881743.

There are many variations of the theatre plans based on Greek theatre, and many theatres are authoritatively drawn in exacting detail. There are openings in the orchestras of quite a few ancient Greek theatres, known as Charon’s Steps, rarely though are any included in those drawings. Even a passing knowledge of Greek mythology would highlight the importance of this reference: Charon is the boatman who ferries the dead across the River Styx to the underworld. Charon’s Steps or ladder are an opening in the middle of the playing space, where you go to meet him in the underworld, although their precise use and validity are questioned by a range of scholars (Ovadiah and Mucznik Citation2009: 309). Throughout the nineteenth century, when these openings were looked at in particular archaeological detail, they were dismissed as coincidental to the theatre and unrelated, not because they were not present in many theatres, but simply because they were present in a few later theatre sites but not at Athens, which dated from the fifth century (Taplin Citation1977: 447). This distinction, despite clear reference in the Onomasticon of Pollux,Footnote3 rendered Charon’s Steps obsolete and apparently not part of Attic (ancient Athenian) theatre.

A gateway to ‘Hell’, in the middle of a Greek orchestra, is difficult to ignore, and yet there were significant efforts made to elide its presence. A. E. Haigh, writing in 1889, was content to dismiss its presence as ‘doubtful’ earlier than the fifth century based on ‘meagre and obscure’ evidence from Pollux. However, his assumptions about how it worked swiftly move from considering that it could ‘hardly have been anything else than a flight of steps leading upon the stage from underneath’ to making a connection to the anapiesma, a sliding lid or cover for lidded traps in the proskenion or constructed scaffolds. He then reduces the significance of the anapiesma to ‘merely the ordinary trap-door of the modern theatre through which the spectral being was raised onto the stage’ (1907 [1889]: 217) as if this in itself was not an extraordinary thing. Haigh lists several plays where this device could have been used,Footnote4 but immediately dismisses such fancies saying ‘there is nothing in the text of the plays to show that this was the case, and an entrance in the ordinary manner would have satisfied all requirements’ (218). It is possible that Haigh is being fashionable here, adopting a position of realist rationalism, although for a nineteenth-century scholar of theatre history, classical literary drama having any sense of performativity is a rarity. Nevertheless, he speaks of Charon’s Steps in exclusively hellish terms: ‘a contrivance for bringing ghosts and spectres up from the other world’ (217).

Oliver Taplin, writing a century later, is equally illusive about the function of Charon’s Steps and the stage space under the orchestra. Taplin is more objective about the evidence and more reflexive as a historian than Haigh had been and he argues that, in the nineteenth century, texts written in Greek and Latin were considered above reproach regardless of evidence or how many centuries after the period they were written. Each piece of received wisdom supported by the antiquated scholarship of the previous centuries was being systematically undone by the late nineteenth–century interest in practical archaeology. As scholars like Haigh returned to nuance in the extant texts, edited and translated to reflect their own interests, the rationality of archaeology found many contradictions. Taplin regards Haigh’s work as ‘the last-ditch reaction on behalf of the scholarship of late antiquity against the textual and archaeological tide’ (1977: 437). There is a similar reticence in Taplin’s work to discuss or validate the evidence for Charon’s Steps, arguing that he is ‘not competent to assess the technical archaeological arguments’ and suggests that if there was an entrance, it may have been useful (448).

Fortunately Asher Ovadiah and Sonia Mucznik were more technically able to investigate this at the start of the twenty-first century, adding another five theatres to Taplin’s list of post fifth—century theatres that possessed an understage room or space in the middle of the performance space in which someone could stand (2009: 310).Footnote5 Importantly, their scholarship is not directly about Greek theatre, but it does resolve the issue of whether Charon’s Steps were used later than the fourth- to second-century theatres they have been found in, because a similar space has been excavated dated to Herod’s reign in the first century in Caesarea Maritima, Israel. Here a large passage (3 m high) connects a mid-stage square room ‘above the tunnel and below the painted pavement of the orchestra’ (311) with the proskenion stage building. This space, they suggest, may have been used for several purposes, ‘the most reasonable of which would have been for a Charonian Stairway … probably adopted by King Herod’ (311–12). Whether Charon’s Steps were used earlier than the fifth century may always be questionable but important for the discussion here is that by the transition from Greek to Roman theatre, the necessity for such a space had been formalized. A passageway of significant size was deliberately built beneath a theatre for hellish aesthetic purposes and it cannot be ignored.

The idea that a sub-stage space can remain connected to the same aesthetic meaning for over four centuries is significant. It suggests that Charon’s Steps as an entrance to and from the underworld formed a significant part of the dramaturgy for premodern theatre. It suggests that even though the physical evidence may not corroborate its fifth-century Attic theatre usage, Pollux considered it to be significant enough as a stage device five hundred years later to mention it and was required frequently enough that it is performatively useful for at least four centuries with the same aesthetic purpose:

the Charon’s Steps or Charonian Stairway are laid for the descents of the ghosts, from which the ghosts are sent forth … the ascents by which the Erinyes [Furies] come up. (Pollux Onomasticon, in Ovadiah and Mucznik Citation2009: 309)

ELIZABETHAN AND ENGLISH RENAISSANCE

Scenographically, an understage ‘Hell’ was accessible by Charon’s Steps or similar means throughout antiquity its presence emphasizing the Greek ‘vertical axis to articulate relations of human and divine’ (Wiles Citation2003: 40). This persisted in the Roman Imperial theatre in ways that reflected the hierarchies of their society and later of Christianity. This shift allowed the vertical axis to focus its ‘attention on Christ’s movement down to Hell, back up to Earth and finally to heaven’ (40–1). At points ‘Hell’ was manifested more literally, in the medieval period becoming a literal Hellmouth with the face of a toothed beast, belching fire, set upon a wagon in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century passion plays (Brockett et al. Citation2010: 40; Butterworth Citation1998: 12).

In the sixteenth century, the scholarly performance of Senecan plays at the Inns of Court required, once more, an understage ‘Hell’. This became a practice that would continue into the Elizabethan Playhouse and English Renaissance theatre (Power Citation2011: 276) where:

the locations of heaven and hell within the theatre … have a practical effect on the way, for instance, members of the audience ‘read’ an actor’s place of entrance and exit. To enter from or exit into heaven has supernatural connotations … . To enter from, or exit into, hell … clearly indicates evil, death—or both. (Stern Citation2004: 25)

This location is emphasized in some instances, as Tiffany Stern points out in her book Making Shakespeare, by specific directions such as those found in in Act 4, Scene 3 of Anthony and Cleopatra. Here eerie sounds and ‘musicke of the Hoboyes [oboes]’ comes from beneath the stage signalling the beginning of Anthony’s downfall (2004: 25). Similar associations are made in Titus Andronicus, Hamlet and Macbeth (26). Thus, although it is clear that the understage was still considered hellish in this period, as Power points out:

The boundaries between the worlds do not need to be breached by a trap or a machina for them to be fully evident to an audience. Just because there is no trap … does not mean that there is no hell. (2011: 280)

Such an association can be hard to shake: ‘Hell’ existed under the stage floor no matter how it was dressed or presented to an audience. Just as early Senecan revivals in the Inns of Court theatre were using trapdoors to manifest hellish effects, the Elizabethan Playhouse utilized the same device some decades later, creating a ‘theatrical vocabulary … wholly conversant’ with Senecan theatrical effect (283) and, as is argued here, unchanged since the fifth century BCE. The association of the understage with ‘Hell’ would also carry through to later presentations of the same material, even when the method of staging changed. Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre for instance, was considered in the nineteenth century to have only required the front of a tiring house (a discrete building directly behind the stage platform), and some stage properties as setting (Southern Citation1951: 105–6): this minimalizing left the understage forgotten. This explains the resistance of those presenting classical drama in the nineteenth century to produce such material in front of anything other than a green baize or ‘green curtain, and nevertheless be listened to with pleasure’ (Mayhew Citation1840: 57; see also Darbyshire Citation1897: 308–17) as a literary poetical form divorced from theatrical staging. Nineteenth-century theatrical practice, however used trapdoors in other parts of its theatrical practice even though it had disassociated classical theatre with their use. Indeed, the spectacular theatre practices of the nineteenth-century theatre did not spring from nowhere. Its antecedents were the European theatres and opera houses that relied upon the understage spaces to perform and perfect scenic changes and create spectacle throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Of particular note were the stage presentations of paradise known as ‘glories’ such as those created by Nicola Sabbatini (1574–1654) in the 1630s. These were elaborate Renaissance representations of heaven produced with the effect of perspective within the frame of the stage, usually in the form of concentric frames or arcs of clouds carrying cherubs. These would descend from above and were lit brightly to present a heavenly vision (Brockett et al. Citation2010: 100–4). This again proffered a vertical axis and a persistent affiliation with the understage being aligned with ‘Hell’ (104). A fixation with the use of stage machinery to produce more and more elaborate changing scenes based along the lines of linear perspective became progressively more elaborate and pictorial in Europe until the influence of nineteenth-century English Melodrama and machinist spectacle (158–65).

NINETEENTH - CENTURY CRISES OF REPRESENTATION

In 1880, in a refurbishment that saw the removal of the forestage at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket in London, the then owners, Lady Marie and Sir Squire Bancroft, made a decision to align the work of the theatre they owned with a form of visual representation and an associated dramaturgy that took one side of an artistic debate that had been bubbling throughout the nineteenth century. Around the proscenium opening they constructed a guilt picture frame on all four edges, ‘[a] rich and elaborate gold border, about two feet broad, after the pattern of a picture frame’ (Fitzgerald Citation1881: 20). Percy Fitzgerald notes this construction as ‘novel’ in his book The World Behind the Scenes and that ‘[s]ome singularly pleasing effects flow from this’. He goes on to argue that, ‘[t]here can be no doubt the sense of illusion is increased … the actors seem cut off from the domain of prose; … the whole has the air of a picture projected onto a surface’ (20–1). This was the culmination of decades of pictorial thinking in the English Theatre, which had permeated every aspect of theatrical representation and created the distinctive form of melodrama where the ‘dramaturgy was pictorial, not just the mise en scène’ (Meisel Citation1984: 39).

This drama was centred upon units of dramatic stasis or pictures presented in a series with each one appearing then dissolving to lead ‘not into consequent activity, but to a new infusion and distribution of elements from which a new picture will be assembled or resolved’ (38). This was a ‘theatre of effects’ where ‘effect’ has the contemporary meaning of devices used to create spectacle, but also a meaning referring to a strong situation presented pictorially (41). Of course, the means by which ‘effect’ was achieved were both physically and dramatically well honed by 1880 and, as Meisel points out, it is surprising that it took that long for a theatre to put a frame around it (39). The picture frame at the Haymarket was the culmination of the ideals of pictorialism that had been supported in the grand European theatres. It was an effort to push the action of the performance space into the space of presentation. In the eighteenth century there were often doors in a proscenium to allow the actors to enter and exit in front of the scenery and get to the part of the stage where they could be heard effectively by the audience (Mackintosh Citation2005: 30). Attempts had been made several times at Drury Lane before 1822 to remove these proscenium doors and combine scenery with action, but the change was firmly resisted by the actors (31). What had followed was decades of theatrical reform and argument in the direction of large proscenium theatres that favoured pictorial, illusionistic presentation. The reformists were ‘totally unaware how very different it was in character from the actor-oriented theatre of the centuries that had preceded [it]’ (2005: 39), their work culminating in the Bancrofts’ firm decision to make the proscenium frame total and solid and without doorways.

Inevitably, it was not to last, and the year after the Bancrofts asked C. J. Phipps for a picture frame around their proscenium, Émile Zola pointed out, quite provocatively, that the ‘impulse of the century [was] toward naturalism’ (2001 [1881]: 4). Where the literary drama was not necessarily forthcoming by this point, and certainly not enough to topple the dominance of melodrama as the principal dramatic style, the mise en scène had been. The complexity of the pictures presented in each scene had undergone a seismic technical shift with the introduction of better lights and lighting technology earlier in the century. This was anathema to the Haymarket’s dissolving scenes, and indeed to any theatre that was trying to use old-style painted scenery and effects in conjunction with new technological developments in lighting. Fitzgerald lamented, in the same year that Zola extolled the virtues of naturalism, that:

the strong elements of scenic effect now in use are actually destructive of each other. A dazzling, blinding light only reveals the barren nakedness of such profile outlines, while vivid streaks of colouring are inconsistent with the smooth surfaces. This excess destroys all illusion, because it reveals even the texture of the boards, canvas, and paint itself, destroying the perspective, and reducing the whole thing to what it was originally—a stage. (1881: 7)

This shift in representational technologies and scenography had many consequences, which were compounded by the development of cinema in the subsequent decades. One of the most profound things that happened is that it made an audience think about theatre space differently. What was exposed by bright light was not only the scenery, but also the means by which the scenery was changed. Effect, as dramatic situation, was diminished due to its exposure as pictorial artifice, and effect as the technical means by which the situation was achieved had been revealed.

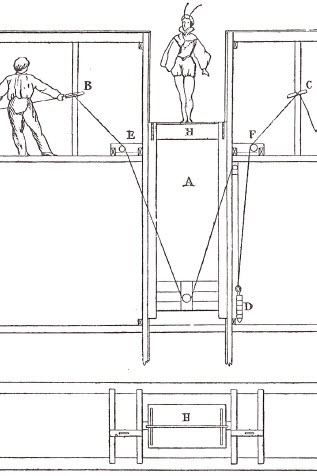

Fitzgerald, for example, praises the technical capability of several devices. Notably first, the Corsican trap, or ghost glide. This trap is situated mid-stage and runs from stage right to stage left. A performer stands on a platform on an inclined plane along that axis. As the device is used, the platform is pulled along the plane so that they move in an upward diagonal motion through and across the stage. The trap is self-concealing with a strip of articulated stage floor called a scruto, which travels at the same speed as the trap’s movement. The effect is of a figure rising and cutting through a solid floor, hence the name ‘ghost glide’. Its primary use was for The Corsican Brothers, a play by Dion Boucicault of 1852 in which a ghost appears to his brother to demand vengeance (D’Arcy Citation2011). The invention was thirty years old when Henry Irving revived it for a realist staging of The Corsican Brothers in 1880. Another device Fitzgerald comments upon is the trappe anglaise or the English trap, a device ‘always associated with the stage, though’ he argues ‘it is the least delusive’ (1881: 55):

A Square hole opens, and literally the ‘round man’ ascends or descends. There is always such a flood of light thrown upon the boards, that the sharp outlines and the whole nature of the operation is so revealed as to become prosaic. (55)

The English trap is an opening in the stage floor usually half a metre each side. They can be placed anywhere on the stage as long as there are 2 metres below the stage to fit the platform and the wood cassette or frame that it runs along. The standard trapdoor consists of a wooden platform and a counterweight. The performer gets onto the platform, the trap cover above their head (which is part of the stage floor above) is slid to one side so that the stage floor opens, then the counterweight is released and the line attached to the platform is pulled so that the actor is propelled smoothly and swiftly onto the stage surface (). It is this trap that is also known as the demon trap and its construction had been largely unchanged since Sabbatini used it (Brockett et al. Citation2010: 104).

Fitzgerald argues that the less light there is the more effective it is. In general he is much more pleased with devices that conceal the fact that they are devices, like the Corsican trap (1881: 47–50), which hides itself with a scruto, or the star trap, which was a special hinged covering for an over-weighted English trap that falls back into place when the actor has passed very rapidly through it (58).Footnote6 In general, Fitzgerald is happy enough if a device does not break the tenuous illusion of the stage, if it does not break the illusion of the drama. He is frequently happy to ‘“make believe” a good deal’ (37) especially when ‘[i]t can never be sufficiently borne in mind that realism or real objects on the stage limit scenic effect in proportion to this realism. Everything should be “seeming”’ (67). Consequently those elements that seemed like they were part of the picture created were deemed acceptable, but those elements that jarred or went against the general presentation of that created reality were problematic. If the traps were hidden, then there was no problem. The Corsican trap afforded the entrance of a ghost onto stage; the English trap, a demon or a genie; the star trap, a sprite or fairy. The covers hid not just the mechanism: they also hid the underworld of the imagination and hidden things get forgotten. Trapdoors hide the understage.

INFERNAL MACHINES

Percy Fitzgerald describes the true space behind the proscenium of a grand theatre, rather breathlessly, as a ‘huge void stretching upwards to the roof, and below as into a mine, where the floor seems to be, and is, really a series of gratings or gridirons supported on pillars … simply filled with planks’ (25). He applies this revelation to all ‘modern theatres’ and concludes that the stage in which the pictorial action takes place, ‘often amounts to no more than a seventh or eighth part of the whole’ (25).

The picture frame in place, this one ‘eighth part of the whole’ was supplied by machinery designed to shift scenes from each direction: from above using counterweight flying systems, or hemp lines pulled by drums and capstans powered by crew in the wings or on a fly floor, or even stagehands inside treadmills; from the sides sliding flats and scenery appeared from the wings moving apparently unassisted across the stage. These flats were attached to substage chariots, rail- mounted flat-carriers operating through slits in the stage floor. Rows of painted scenery emerge from the ground through other slots in the stage floor called sloats and, of course, beneath the floor there are stage bridges: large moving platforms that afford the access of larger groups of performers running across the stage. Bridges too were counterweighted, like giant English traps operated by stagehands pulling lines and allowing the constructions to rise and fall, with the assistance of windlasses or winches.

It is probably not too odd that Fitzgerald does not describe the understage as ‘Hell’, but as the ‘tween decks of a vessel’ (46). It is clear that he knows that the theatre in London at that time was on the brink of a shift in style and aesthetics. He was trapped between the nineteenth-century mode of writing about the theatre as a reportage similar to society journalism, and theatrical memoir. Fitzgerald assumes a position of insider knowledge, revealing how the behind the scenes functioned from a suitable distance. Edward Mayhew strikes a similar note in Stage Effect when dealing with the subject of understage machinery:

Concerning traps, etc., no directions can be of any value, the carpenter of the theatre being the only person who need study these mysteries. Let the author give his imagination free scope, and he can hardly write directions which cannot be fulfilled. (1840: 66–8)

The nineteenth century was a time of increasing professionalization in the theatre. Mayhew’s dismissal of the technical in a book about ‘good effect’ on stage is resolutely concerned with only the textual elements of mise en scène: the actual moments of making theatre on stage. How that effect was manifested was beyond the scope of his work. Fitzgerald was absolutely interested but reticent to describe it with any level of precision, preferring instead to speculate upon the reception of the effect and how it affected our satisfaction as an audience. His discussion about early realist effects taking over illusionistic effects is illuminating, quite literally as it lays the audience’s dissatisfaction directly at the feet of new lighting technologies, but he finds himself at a paradigm shift: marvelling over the ‘illusions’ of reality created on the stage, which were neither truly illusionist nor realist. Such a point invites a schism: go real or go symbolist and herein lies the problem. The gravity created by realism rejected illusion but had become the dominant form in the old theatres. Symbolism was in response to realism and shunned the devices associated with the illusion of realism. The wood stage devices languish in the middle, forgotten by one and rejected by the other.

SECULAR PLAYS, SECULAR ARCHITECTURE

This was a dichotomy of change that plagued all of London Theatre and whose repercussions were felt across the UK, Europe and the US. Some years before the Bancrofts drew their line in the sand and put a frame around the Haymarket stage, other theatres were being built with no understage or flies at all. The Criterion in London, for example, taking its influence from the Athenée in Paris was built underground in 1874 with neither flies nor understage, expressly for the production of parlour comedies and the inheritors of cup-and-saucer realism such as James Albery (Meisel Citation1984: 49–51). The focus of the Criterion’s architect, Thomas Verity (1837–1891), was to not consider the staging of the plays beyond the fact that it needed only that part of the theatre that would be seen. Verity was interested in the comfort of the patrons and their social life, not the theatrical production. Other theatres constructed after the Criterion were to follow suit, built with only enough room beneath the stage to anticipate the use of understage machinery only if necessary, not as a necessity.

The professionalization in theatre production had also extended into theatre architecture, with a growing schism between those involved in the planning of the theatre operation as a construction, and the exterior as an attractive public building. Caught in the middle were the growing breed of theatre architects whose expertise increasingly called for ‘special experience’ (Anonymous 1898: 260. These specialists had ‘estranged the architect … . He has to be expert in … matters which it would take a lifetime to almost master’ (260).

Edwin O. Sachs returning from a trip around Europe collecting information about theatres and opera houses recognized that a movement of stage reform originating in Austria in the 1870s had ‘the primary object of encouraging the greatest possible imitation of nature in the mise-en-scène [sic] of opera and drama’ (Sachs Citation1898: 556). This movement had been spurred on by several fires at large European theatre and by the spread of disease in public gatherings. This created the opportunity to rebuild theatres differently: considering the comfort and safety of the audience, and using ‘modern sciences … and … modern methods of lighting’ to bring the ‘rudiments of art, … to the stage’ (568). This reform started initially in Austria and Germany but spread quickly throughout the European theatre industry to solve the same problems of social hygiene, safety and pictorial realism where ‘a true scenic art was to take the place of the non-descript, irrational, and frequently coarse mounting previously given to plays’ (568).

Sachs argued that the effect on the continent was more successful than in the theatres of the UK, because they were publicly funded. In London, where actor-managers financed such endeavours personally, it had resulted in a coarse realism. The reform lacked the machinery and lighting dedicated to the grand pictorial changes of the German and French theatres (569). Sachs argued that the English stage of 1897 was no different from the stage of 1700 save for the instance of the electric light and limelight and he called the wood-stage system of traps and bridges ‘antediluvian’ in comparison to the European stages. European theatres were technologically diverse containing wood stages, wood-and-iron stages and iron stages, the latter two requiring electrical and hydraulic machines to operate and all requiring a good deal of manual labour. The English stage, by comparison, seemed to have been passed by, any elements of reform remaining within the old templates of stage presentation. While the rest of Europe specialized in the separation of the technicalities of the stage and the architecture of the building and constructed each in step according to the requirements of the art form, the English stage languished in unpreparedness:

With few exceptions, … the construction of our stages [is] in the hands of a stage carpenter, who has had no exceptional advantages in the way of technical training … . Abroad, … the commissions are given to fully qualified engineers. (Building News, 22 April 1898: 559)

The understage’s neglect, then, was not one of professionalization perhaps, but was a financial neglect. The craft involved atrophied because the actor-managers wanted to produce plays that satisfied the popular realist demand. Rather than do what the continent did, they chose instead to write for a realist stage that did not move or open, producing drawing room dramas with cup-and- saucer realism. Plays that drew an audience— now more comfortable and less crammed—into the auditorium of a theatre that was increasingly bourgeois, socially engaged and consequently secularly realist. Presented within the frame, the stage realism became mundane. No scenery to change meant the parts of the theatre that could change did not: the fashion became for drawing room comedies and an evening of entertainment. The larger theatres could still do opera, but the prevalence of an understage was less pronounced and, in short, forgotten.

SYMBOLISM AND THE INFLUENCE OF JAPANESE THEATRE

It is not surprising therefore that the reaction against this ‘theatre reform’ was in large part against the realism presented within the proscenium arch, but it would be a mistake to think that the contention was between a spectacular pictorial realism and more modest realist productions that required detailed settings in drawing rooms. Simultaneous to Sachs’ vision of stage reforms involving pictorial realism supported by professionalized engineering solutions beneath the stage, the symbolists in the French theatre were thinking of dispensing with realism entirely. Symbolism shunned theatre machinery and illusionistic scenery and spectacle for its complexity (Ernst Citation1969: 128) and for its association with the dominant form of commercialism and naturalism (Tian Citation2018: 16). The development of that form of avant-garde thinking coincided with precisely what Sachs was arguing: that the English stage could not afford to sustain spectacle. Those constructing new theatres found themselves caught between the commercial naturalistic movement of European theatre and the symbolists, who urged for simplicity in mise en scène and an abstraction of the pictorial illusion. Neither movement required an understage. English theatre, dominated by the Western desire to remain focused on the poet- playwright, developed drama and comedy, which only required a type of stage that fitted just in the one eighth that was seen of the theatre building. Meanwhile, the reformists of the mise en scène, in particular those of the symbolist and avant-garde persuasion such as Vsevolod Meyerhold, Adolphe Appia, Edward Gordon Craig and Alexander Tairov, spent much of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries working against the tides of naturalism that had taken hold of European theatre. Tairov, working across Europe touring in 1907 and 1908 with Mobile Theatre, notes that most audiences ‘had still not outgrown naturalistic illusions’ and had swapped the pictorial for the three-dimensional and static— his production was forced to carry an entire log cabin with them ‘all so that the walls, God help us, might not shake when the actors touched them and reveal to the audience the terrible secret that there was scenery on the stage’ (Tairov Citation1969 [1921]: 45).

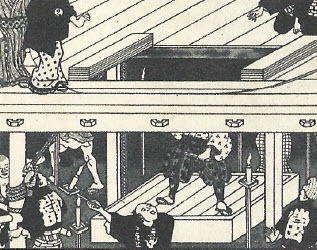

One of the places this branch of reform looked to was the theatre of Japan (Earle 1969: 128; Tian Citation2016). Independent from Western theatre (Leiter Citation2002: 95), the Kabuki stage also had complex stage machinery: stage devices such as a revolve, developed one hundred years before the European examples (Tourist Library Citation1936: 45; Miyake Citation1959: 37), trapdoors such as the seri and kiriana (Leiter Citation2002: 95) and an understage called Naraku, literally translated as ‘Hell’ (Tourist Library Citation1936: 60).

Edward Gordon Craig, already well informed about Kabuki Theatre, had seen the influential European tour of Sada Yacco and Kawakimi in the first decade of the twentieth century as had Vsevolod Meyerhold and Adolphe Appia (Tian Citation2018: 55–6). This tour was an adapted form of Kabuki, reblocked for the European proscenium stage, but had created a great deal of public and professional interest for the theatre and its stagecraft (Tian Citation2016: 321). Craig was less enamoured with the form than Meyerhold and Appia, terrified of the danger it presented to the primacy of the Western form (Tian Citation2018: 63) even though it seemed to his collaborators that the related Japanese forms of Nō and Bunraku were similar to what Craig was preaching in his own stage reform. They considered Kabuki to be a method of performance and staging matching ‘Craig’s abhorrence of psychological realism’ (Tian Citation2018: 57).

Craig may have dissuaded himself from adopting any of the staging conventions of Kabuki, but Meyerhold took a different approach. Meyerhold adopted the hanamichi, ‘the flower path’, a strip of stage that led from the performance area across the audience space (Leiter Citation2002: 205–30) from the Japanese Kabuki stage. This was a direct reaction against the framing of the stage as separate from the lived experience of the audience. The hanamachi, as he saw it, reinforced the connection between the audience and the stage, and connected both to the drama. He did not, however, transfer every aspect of this strip of stage. He ignored, or more likely was ignorant of, the seri (), the trapdoor in the middle of the hanamachi, and several other stage devices developed by that theatre form. The seri is relevant here: it was the entrance to an underworld that accessed the space beneath the stage known as ‘Hell’.

Figure 4. A Kabuki stage trap: the seri. The sup-pon on the hanamichi is similarly operated (Tourist Library Citation1936: 60).

This infernal coincidence is very difficult to explore in any depth especially as it involves the merging of two artistic practices: the European avant-garde and the Japanese Kabuki, both notorious for innovation and cultural cross-pollination. Meyerhold was reacting to pictorial realism in the stages of Europe—those that were successfully carrying out the reforms identified by Sachs. A rejection of that form is a rejection of the whole of the old form of theatre in the new avant-garde modernist stage, traps and understage included. Meyerhold wished to solidify his theatre theories, by utilizing the novel practical elements of Japanese theatre within his work.

His study of Japanese theatre was for the most part theoretical. Having seen the tours of Kabuki in European theatres without the traditional staging or stagecraft, he had studied drawings and prints of the full form. This study was detailed but it lacked a full comprehension of the stagecraft involved, though it did provide solid inspiration for partial adaptation and recreation (Tian Citation2016: 326). The hanamichi was a clearly visible signifier (Figure 5) that the stage space was different and sympathized with democratic modernist sensibilities (Tian Citation2016: 333), but the seri was too similar to the Western demon trap. Not only that, but it fulfilled the same dramatic and aesthetic function. The suppon was similar to the seri trapdoor, but was situated specifically in the middle of the hanamichi. The suppon allowed the access of mystical characters, such as ghosts and demons directly onto the audience space (Leiter Citation2002: 71–2).

For modernists this may have raised contempt in its familiarity. Just as the European theatre was influenced by the Japanese theatre, the similarities in mise en scène, accentuated by reblocking the tours for a European stage, were also clear: the Kabuki favoured a pictorial setting. The Kubuki troupes touring in Europe and returning to Japan were equally influenced by the perspective pictorial style of European naturalism (Tian Citation2016: 321). The stage devices may have been a step too far and a distraction from the modernist aims of the symbolists: to reject the old forms of the past. Meyerhold was interested primarily in the anti-psychologism and performativity of the performance and the aesthetic difference in presentation to the European theatre traditions as a method of acting and theatricality (Tian Citation2016: 332).Footnote7 Craig was interested but denied the form for the same reason. Kabuki was different enough to challenge the psychological realism of the stage that had formed over the previous century, but Meyerhold was careful about which elements of the stage he used to challenge it. With a hanamichi, you could not possibly have an effective picture frame around the stage; it even resisted the centuries-old emphasis given by Gothic churches ‘to the principle of end-on staging’ (Wiles Citation2003: 44, 101–3). This raises the older question of efficiency and box office: how to get as many people as close to the action as possible ‘without jeopardising the actor’s primary task of communicating with every spectator’ as the pragmatic Elizabethan theatre architecture had been (Mackintosh Citation2005: 9). This was part of a shift in theatrical form that was shouting ‘very loud’ for a return ‘to an actor-oriented theatre’ (2005: 39), one that would see an eventual decline in scenic illusion of the kind hoped for by the Bancrofts and their stage picture frame.

STAGE REFORM AND THE DISSOLVING ‘HELL’

This was not an instant shift, of course; theatre is in constant, elastic, tension between tradition and reform. The removal of the proscenium doors at Drury Lane took the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The apogee of illusionism was reached in 1875 with the Palais Garnier in Paris, and the start of modernism in theatre was in 1876 with the completion of Wagner’s Festspielhaus. The Palais Garnier, praised so highly by Fitzgerald and so influential to the Bancrofts, was the height of magnificence, whereas the Festspielhaus was a ‘cut-price building’ (Mackintosh Citation2005: 40) devoid of decor and comfort, focused upon the performance and good sightlines. The result was that the emphasis was to focus upon what was seen and heard, and the experience of the audience in the theatres. In the negotiation of those priorities, the aesthetic place of the understage slips. It is still present but the meaning changes.

The nineteenth-century culmination of theatre forms and types and technologies had tried to place the scenic and the performative within the single frame. Separate technologies had been used to create the presentation of scenery and the entrances of people onto the stage. While that remained the case both scenery and trap were specific technologies, each with their own readable aesthetic meaning: the ghost glide, the demon trap, the star trap, the bridge, the Parallèle were all used for separate purposes and acknowledged as having different scenic functions associated with different aspects of the theme of ‘Hell’. You would not, for example, use the star trap for a ghost, or the ghost glide for a genie, or the Parallèle to produce anything other than the entrance of multiple faeries. The chariots and grooves were used for scenery as were sloats. Meanwhile above the stage the fly tower with its lines and riggings brought in cloths and scenery, whose function was to present pictorial elements to enhance the setting, but they were being replaced by heavy three-dimensional realist scenery so were losing detail and becoming more representational. What the various representation reformations at the end of the nineteenth century achieved though was to make all of these things indistinct from each other. They were no longer specific devices but elements of the proscenium stage machine as a single technology—the seven-eighths that the audience could not see working in concert to support the whim of a visually more versatile, psycho-plastic stage. A stage where the audience supplied the imaginative content suggested by the framing scenography, just as the Invisibilists, another avant-garde group of modernists, had presented empty frames hung in a gallery in New York in the 1920s. These frames, would present placards with titles but contain only blank canvases, the idea being that the vision of the title was to be completed by the spectator. The stage reforms of the late nineteenth century rendered the specificity of the wood-stage effects, psycho-plastic: support for the imaginations of the audience in line with the dominant Western aesthetic of the twentieth century—the black-box space, developed from the collective work of the stage reformists Appia, Craig, Tairov and Meyerhold. A drama performed in a black-box space with no adornment requires the audience to imagine setting and environment provoked by the performance. Later in the twentieth century, scenographer Josef Svoboda extended the Invisiblist concept of psycho-plasticity in his work using design to create psycho-plastic space ‘which means it is elastic in its scope and alterable in its quality. It is space only when it needs to be a space’ (qtd in Burian Citation1970: 126). This alterable elastic quality is supported by a range of stage technologies that are similarly psycho-plastic in aesthetic function (D’Arcy Citation2017).

DIVERSIFIED AND DISSOLVED

The aesthetic purpose of the proscenium theatre as stage device became diversified supporting whatever the stage box required. As the form of drama changed within that box to become more realist and secular, the idea of ‘Hell’ being beneath the stage was no longer required, and the literalism of the stage declined in enough instances to make it infrequently evoked as a term. Any use of a trapdoor to produce something became just another entrance, a device for instant reveal, but not necessarily a demonic one—just as likely to produce a hero as a villain, or simply decoration to the stage. The theatre was no longer surrounded by machines, but was a single machine supporting the psycho-plastic scenic function. The audience imagines the result, the device helps produce it or solidifies, or realizes, the thought.

For those nineteenth-century theatres that had understage space and exist still today, it is a space of opportunity and continues to provide spectacle as it gives room for automation such as that found in Billy Elliot (2008) at the Victoria Palace Theatre, London. Here the understage space of a Frank Matcham (1854-1920) theatre built in 1911 allows room to fully automate the stage. In Billy Elliot, the stage split into sections, opened and raised a revolving tower of scenery onto the stage, which would drop down and turn and create different settings for various parts of the show.Footnote8 This is of course precisely why the understage of the theatre building existed in the first place: it provided the room for machinery, eventually automated, to allow the repeatability and precision of stage spectacle. In its contemporary use, this supports the action, rather than adding specific meaning. The towers of scenery that emerge from the stage in Billy Elliot, or similar automated spectacle from other West End musicals, perform a psycho-plastic function supporting the realism of the story worlds with un-hellish theatrical spectacle.

Even in examples where the supernatural or the hellish is involved, it is not necessarily invoked by the use of devices whose aesthetic is specific to that aesthetic meaning. Phantom of the Opera, for instance, was based on the Gaston Leroux novel and set in the dark, watery catacombs and accident-plagued auditorium of the Palais Garnier where this article began. Phantom of the Opera remained resident in Her Majesty’s Theatre in London from 1986 to 2020. The extant theatre building, designed by C. J. Phipps in 1897, has two understage stories descending to 6 metres below the stage and operates an impressive range of carefully preserved and restored nineteenth-century stage devices such as stage bridges and trapdoors (Hume Citation2021). Even so, a play set in the understage of the Palais Garnier with its many infernal implications is only supported by the stage machine of the theatre. It is the flooded labyrinthine cellar of the Palais Garnier that creates this atmosphere and not the implications of ‘Hell’ that the understage provides.

The water flowing around the foundations of the Palais Garnier is said to give the theatre building some interesting acoustic qualities, adding to those resonances already present in every wooden stage floor: the guitar-like sounding board echoing with footsteps. This is an acoustic quality that implies a present but unseen space beneath the stage, a quality that Josef Svoboda proposed to use for his own infernal purposes in his scenography for Alfred Radok’s unrealized production of Goethe’s Faust. Svoboda proposed a special floor for this two-person production, one that would echo the hollow footsteps of Faust’s servant Wagner as they walked around the large stage space with their footsteps resounding over the boards in the space. Svoboda proposed the use of giant felt dampers beneath the stage to deaden the sound on cue (Baugh Citation2005: 87–8), so that Wagner’s footsteps could become muted, effecting the change of character into Mephistopheles:

The servant walks to the door, and we hear the hollow sound of his steps in the vast room. He turns just as he reaches the door, and starts back—and suddenly— silence!—and we know, instantly that it’s the devil. (Burian Citation1971: 19)

For Svoboda, this proposed acoustic device was the essence of his ideas of the drama interacting seamlessly with the scenography in a psycho-plastic space. The removal of resonance would remove the understage for the audience enough to imply the presence of a devil on the stage. It is also a reminder of how the unseen invisible space below the theatre stage is also ‘space only when it needs to be a space’ (Burian Citation1970: 126), a reminder of the hidden ‘Hell’.Footnote9

The understage has been freed from the connotations of the hellish. A demon trap is now just a trap, its hellish connection losing its demonic connotation as it is used to transfer other things to the stage surface. It is a mode of access and egress into the scene, much as it ever was, but its scenographic function has become more psycho-plastic, less connected to a hellish aesthetic and to that raft of meanings. It is instead associated with generic spectacle, a wow- factor reminiscent of the faery presentation but with less pagan magic. In those theatres without an understage or room to work machines, the dimension is entirely forgotten, dispossessed, ignored. That axis is the privilege of the theatres with money for high-end entertainment. In the black-box space, there is no understage, as there are no wings and no heavens, only imagination. We have trained our theatre imaginations away from ‘Hell’. What remains is a hangover, a label for a space that is used as insider-speak for a stage locale, just as stage left is known as ‘prompt’, or the ladder up to the grid is ‘the jacob’s’. It is no longer a specific aesthetic space with demonic supernatural implications, but part of the thing that makes the stage work as a performance space. A reminder though: it took twenty years to remove the proscenium doors and over one hundred to undo that movement and dispense with pictorial scenery as the dominant form. ‘Hell’ has been under the stage since the fifth century BCE.

Notes

1 Moynet’s title is L’Envers du Théatre, literally ‘the reverse side of the theatre’ or more prosaically ‘theatre backstage’. The pun of the title here is derived from it: ‘L’Enfer du Théatre’, The Hell of Theatre.

2 David Wiles’ thorough A Short History of Western Performance Space (2003) is an excellent resource for explaining the variance in these spaces.

3 The Onomasticon of Julius Pollux was a dictionary and thesaurus of Attic terms written around 177 CE that included detailed explanations of Greek theatres and stagecraft. Translations of the theatre-specific terms were included as an appendix in the first English-language edition of Aristotle’s Poetics, or, Discourses Concerning Tragic and Epic Imitation (1775). The complete text is kept in several museum archives but a version of the appendix ‘concerning parts of the theatre’ can be found online (see Pollux (Citation1775 [177 CE]). In this early and severely abridged translation, there is a single fleeting reference to ‘Charon’s Ladders and Pullies’ (8), the reference here to ‘Pullies’ is particularly tantalizing.

4 Aeschylus’ The Persians and Eumenides; Sophocles’ lost play Polyxena; and Euripides’ Hecuba (Haigh 1907: 217–18).

5 Eretria, Magnesia Tralles Philippi, Maroneia, Dion, Argos, Corinth. Examples at Segesta and Sicyon actually turned out to be storm drains (Ovadiah and Mucznik Citation2009: 311).

6 A demonstration of this alarming stage device can be found online (Murphy Citation2011).

7 Meyerhold used a basic hanamichi in several productions: The Unknown Woman (1914), The Forest (1924) and The Second Army Commander (1929) (Tian Citation2016: 333).

8 Stage automation from Billy Elliot 2008 at the Victoria Palace Theatre, London, can be found online (AVWControls Citation2008).

9 The eventual realization of Svoboda’s scenography for this version of Faust never materialized. In 1988 Svoboda began an experimental collaboration with Giorgio Strehler on a production of Faust Fragments for Piccolo Teatro at the Teatro Di Milano, Milan. The scenography was lighting and projection based.

REFERENCES

- Anonymous (1898) ‘The Design of Theatres’ 25 February. The Building News and Engineering Journal; January to June 1898 volume 74. [online] available at: https://bit.ly/3E85TmS accessed 18 June 2021. pp 260-261

- AVWControls (2008) ‘Billy Elliot Stage Machinery’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=21UqRW7NkV4, accessed 27 April 2021.

- Baugh, Christopher (2005) Theatre, Performance and Technology: The Development of Scenography in the Twentieth Century. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brockett, Oscar G., Mitchell, Margaret and Hardberger, Linda (2010) Making the Scene: A history of stage design and technology in Europe and the United States, San Antonio, TX: Tobin Theatre Arts Fund.

- Burian, Jarka M. (1970) ‘Josef Svoboda: Theatre artist in an age of science’, Educational Theatre Journal 2: 123–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3205717

- Burian, Jarka M. (1971) The Scenography of Josef Svoboda, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Butterworth, Phillip (1998) The Theatre of Fire: Special effects in early English and Scottish theatre, London: Society for Theatre Research.

- Darbyshire, Alfred (1897) An Architect’s Experiences: Professional, artistic, and theatrical, Manchester: Cornish.

- D’Arcy, G. (2011) ‘The Corsican trap: Its mechanism and reception’, Theatre Notebook 65(1): 12–22.

- D’Arcy, Geraint (2017) ‘“Visibility brings with it responsibility”: Using a pragmatic performance approach to explore a political philosophy of technology’, Performance Philosophy 3(1), https://bit.ly/3z53PZ7 accessed 7 April 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.3139

- Ernst, Earle (1969) ‘The influence of Japanese theatrical style of Western theatre’, Educational Theatre Journal 21(2): 127–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3205628

- Fitzgerald, Percy (1881) The World Behind the Scenes, London: Arno Press.

- Haigh, A. E. (1907 [1889]) The Attic Theatre: A description of the Stage and Theatre of the Athenians, and of the Dramatic Performances at Athens, 3rd edn, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hume, Mike (2021) ‘Her Majesty’s Theatre’, Historictheatrephotos.com, https://bit.ly/2YLtSZ6, accessed 27 April 2021.

- Johnson, Ray (2007) ‘Tricks, traps and transformations: Illusion in Victorian spectacular theatre’, Early Popular Visual Culture 5(2): 151–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17460650701433673

- Laumann, E. H. (1897) La Machinerie au Théatre: depuis les grecs jusqu’a nos jours, Paris: Maison Didot.

- Leiter, Samuel J. (2002) Frozen Moments: Writings on Kabuki 1966–2001, New York: Cornell University East Asia Program.

- Mackintosh, Iain (2005) Architecture, Actor, Audience, London: Routledge.

- Mayhew, Edward (1840) Stage Effect: Or, the principles which command dramatic success in the theatre, London: C. Mitchell and Red Lion Court.

- Meisel, Martin (1984) Realizations: Narrative, pictorial, and theatrical arts in nineteenth century England, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Miyake, Shūtarō (1959) Kabuki Drama, Tokyo: Japanese Travel Bureau.

- Moynet, Georges (1893) Trucs et Décors: explication raisonnée de tous les moyens employés pour produire les illusion théatrales, Paris: Libraire Illustrée.

- Moynet, J. (1972 [1874]) L’Envers du Théatre, New York: Benjamin Blom.

- Murphy, Neil (2011) ‘Q Division Star Trap’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17bR-8HVMMA&t=58s.

- Ovadiah, Asher and Mucznik, Sonia (2009) ‘XAPΩNIOI KΛIMAKEΣ in the Roman Theatre of Caesarea Maritima’, Liber Annuus 59.

- Pollux, Julius (1775 [177 CE]) ‘Extracts concerning the Greek theatre and masks’, in Aristotle’s Poetics, or, Discourses Concerning Tragic and Epic Imitation, London: J. Dodsley and Messrs Ricardson and Urquhart, https://bit.ly/38TEZAP, accessed 22 April 2021.

- Power, Andrew J. (2011) ‘What the Hell is under the Stage? Trapdoor use in the English Senecan Tradition’, English 60(231): 276–96.

- Sachs, Edwin O. (1968 [1896]) Modern Opera Houses and Theatres. Volume II, New York. Benjamin Blom.

- Sachs, Edwin O. (1898) ‘Stage Mechanism’ 22 April. The Building News and Engineering Journal; January to June 1898 volume 74. [online] available at: https://bit.ly/38TEZAPaccessed 18 June 2021. pp 556-558

- Southern, Richard (1951) Changeable Scenery: Its origin and development in the British theatre, London: Faber and Faber Limited.

- Stern, Tiffany (2004) Making Shakespeare: From stage to page, London: Routledge.

- Tairov, Alexander (1969 [1921]) Notes of a Director, trans. William Kuhlke, Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press.

- Taplin, Oliver (1977) The Stagecraft of Aeschylus: The dramatic use of exits and entrances in Greek tragedy, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Tian, Min (2016) ‘Authenticity and usability, or “welding the unweldable”: Meyerhold’s refraction of Japanese theatre’, Asian Theatre Journal 33(3): 310–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/atj.2016.0033

- Tian, Min (2018) The Use of Asian Theatre for Modern Western Theatre: The displaced mirror, London: Palgrave.

- Tourist Library (1936) Japanese Drama, 2nd edn, Tokyo: Maruzen Company.

- Urban, Eliza Dickinson (2019) ‘Spectral spectacle: Traps, disappearances, and disembodiment in nineteenth-century British melodrama’, Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 46(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1748372718799081

- Wiles, David (2003) A Short History of Western Performance Space, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zola, Émile (2001 [1881]) ‘Naturalism on the stage’, in Toby Cole (ed.) Playwrights on Playwriting: From Ibsen to Ionesco, New York: Cooper Square Press, pp. 5–14.