Abstract

Air pollution is one of the most significant factors to address when making connections between climate crisis and globalisation. The often-invisible gas emissions (carbon, nitrogen and sulphur dioxides) from cities around the world demonstrate that a large part of anthropogenic fallout takes place not just in the landscape and oceans, but also in the air around us, in what we breathe in every day but frequently overlook. Accordingly, this article investigates three artistic/sociological/architectural projects that establish relations within the ‘Capitalocene’ to identify and combat the causes and harmful effects of air pollution in Los Angeles, Douala, London and Madrid. Analysis of Public Smog, Citizen Sense and In the Air considers the earth's atmosphere above these urban and sub-urban communities as a site where philosophical New Materialism can be revealed and explored. A key aim for the article is to recognise a transversal relationality among actants that operates – or performs – on ecological, economic, and political levels, simultaneously.

Air pollution is one of the most significant factors to confront when making connections between ecological crisis and globalization. Space-time compressions resulting from advances in travel, e-commerce and extraction have aggravated the production and transformation of many variants of harmful waste. The often-invisible gases (carbon, nitrogen and sulphur dioxides) that are concentrated in urban centres around the world demonstrate that a large part of anthropogenic fallout takes place not just in the landscape and oceans, but also in the air around us—which we breathe every day but frequently overlook or ignore. Smog is caused by the burning of fossil fuels and the accumulation of pollutants in the troposphere or lower atmosphere. Dangerous gas emissions contribute to global warming, which in turn creates conditions to produce lung-damaging ‘ground-level ozone’ (Mackenzie Citation2016). Thus, there is a direct and cyclical correlation between grounded corporeality or embodiment and the aerial.

A recent article for the New York-based Natural Resources Defence Council (NRDC) has exposed growing threats to the resilience of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s 1970 Clean Air Act due to the irresponsible policies of former EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler. By refusing to confront the increasing and unhealthy levels of ozone and particulate matter (PM) and legislate for their immediate reduction, the EPA, under President Trump, failed to rectify their detrimental impact on respiratory health (Davis et al. Citation2021). In a promising turn of events, President Biden has since reintroduced the US to the 2016 Paris Agreement dedicated to the international reduction of atmospheric toxicity. The EPA’s failure to resuscitate and evolve the Clean Air Act was also alarming due to the rapid expansion of coronavirus (COVID-19), a zoonotic disease that, according to research conducted in the US, frequently results in respirational disorders undoubtedly compounded by poor air quality (Wu et al. Citation2020).

Achille Mbembe has carefully reflected on human subjectivity and an ecologically damaged planet united by this pandemic. In ‘The Universal Right to Breathe’, he considers how ‘we have never learned to live with all living species, have never really worried about the damage we as humans wreak on the lungs of the Earth and on its body’ (2021: 59). Consequently, ‘[t]he hour of autophagy is upon us’ as we enter ‘a new period of tension and brutality’ (59). For Mbembe, ‘brutalism’ is a highly significant concept that connects colonial hegemony to contemporary environmental extractivism; it encompasses a variety of actions or forces that pertain to the expulsion of natural resources or, in a word, to their ‘depletion’ (60). These depletive or brutal conditions are self-inflicted, confining and reveal socio-political and economic inequalities; they have infringed upon humanity’s capacity to healthily inhabit local environments, that is, to breathe, in an ethical way. Mbembe’s urgent call for the ‘voluntary cessation’ of such brutalism is one of action and resistance (62). It is in that spirit of agency that this article analyses three cultural experiments that investigate and interrogate atmospheric relations within the Capitalocene, an epoch in which humans and non-humans cannot be dissociated from the scalar ramifications of industrial consumerism.

A theoretical framework for thinking about the performativity of polluted air can potentially be found within new materialism, a contemporary discourse in search of a practical philosophy for turbulent times. Following in the footsteps of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, many new materialist critics champion a concept of ‘transversality’, whereby cultural criticism and political activism do not put meaning before matter; that is, by attending to moments of interconnection, encounter and unexpected lines of flight, performative relations can be understood on new platforms of experience exchange. There is now a shifting sense of reciprocity between subjects and objects, knowledges and things or epistemology and ontology that supports a model of fluctuation, or what Karen Barad would call ‘intra-action’ (2007: 141). If, as she contends in an interview on new materialism, ‘[m]atter itself is not a substrate or a medium for the flow of desire … [but instead] makes itself felt’, then air quality becomes something tangible and performative in terms of human and more-than-human embodiment (Dolphijn and van der Tuin Citation2012: 59). The earth’s atmosphere above urban and suburban communities establishes a site where such relations can be revealed and explored.

I argue that the three artistic, sociological and architectural case studies that follow extend these practical and theoretical observations to the elusive but nevertheless real or specific materiality of the air itself in local populated zones, investigating the economic, geopolitical and anthropogenic effects on the earth’s atmosphere and, therefore, on everyday life in those communities.

PUBLIC SMOG

In 1968, two years before the Clean Air Act was passed, ecologist and biologist Garrett Hardin published an important, and now famous, article in Science magazine. Fundamentally, ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ interrogates the encroaching problem of population growth as a principal contributor to climate crisis. Hardin argues that an ideology of limitlessness, when it comes to goods and resources or a commons for all, can no longer serve as the systemic foundation for what is increasingly understood as a limited material planet. In other words, by miscalculating an abundance of common ground, human beings have not been able to discover ‘an acceptable theory of weighting’ (1968: 1244). The emphasis on calculation and measurement problematizes human rights over the rights of nature and demands a reappraisal of futurity and progress. Hardin continues:

the air and waters surrounding us cannot readily be fenced, and so the tragedy of the commons as a cesspool must be prevented by different means, by coercive laws or taxing devices that make it cheaper for the polluter to treat his pollutants than to discharge them untreated. (1245)

In 2004, visual artist Amy Balkin commenced an ongoing project whose focus resonates with Hardin’s provocation, taking up his challenge to implement alternative methods for reconstituting the commons following a necessary refusal of the nature/culture divide. Public Smog was conceived as a national park or nature reserve: remarkably, one that would be located, monitored and cared for in the air space above designated cities or wider areas. The work has had several iterations, first opening over the South Coast Air Quality Management District in California and, in 2007, over the European Union. In 2012, the project was exhibited at dOCUMENTA 13 as a collection of cumulative archival materials, video installation and pieces of live evidence (Balkin Citation2021). Significantly, over time, the growing artwork has raised the possibility that air spaces above urban and suburban settlements might acquire the status of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, thereby expanding and questioning the territory normally reserved for conservationism or land-based national parks. In this way, Balkin has been able ‘to re-imagine and reappropriate atmospheres as political spacetimes’ (McCormack Citation2018: 214).

T. J. Demos’s analysis of Balkin’s practice explores the contemporary problem of the ‘“financialization of nature”, according to which natural forms, such as atmospheric carbon, are regulated by market dynamics within neoliberal capitalism’ (2016: 26). Eco-political art often operates from a critical stance that opposes cornucopian futurism. Accordingly, Balkin’s project becomes a complex and subversive mechanism that challenges greenwashed models of repair. One of the aspects of eco-activism within which Public Smog participates in both playful and serious ways is an interrogation of carbon credit ideology. Companies can use carbon offsetting to justify exceeding caps on harmful emissions in populated areas. While this approach is often presented as a stable model that maintains an equilibrium between producing and controlling air pollution, imbalances and incongruities can and do quickly appear. It is for this reason that the Durban Declaration on Carbon Trading was founded by climate activists visiting South Africa in 2004, in order to debunk carbon trading as the ‘neoliberal false solution to climate change’ and demonstrate how ‘[g]overnments, export credit agencies, corporations and international financial institutions continue to support and finance fossil fuel exploration … while dedicating only token sums to renewable energy’ (Lang Citation2021).

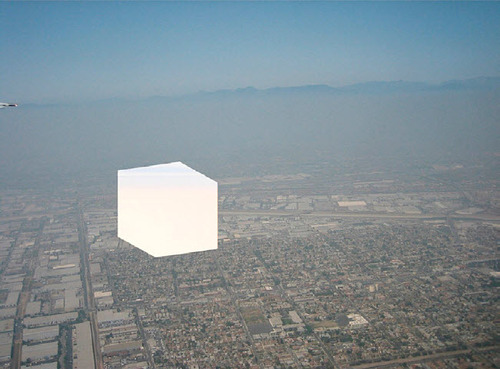

Fig 1. Amy Balkin, Public Smog (2004–ongoing), Public Smog over Los Angeles.

Public Smog first opened during the 2004 summer smog season over California’s South Coast Air Quality Management District, which includes Los Angeles and Orange County. Image courtesy of the artist

The Public Smog project positions the individual participant as an agent who can infiltrate and tamper with this market-driven culture of pollution. Balkin has managed to participate in the carbon credit systemFootnote1 in a manner that reveals not only what it performs, with regards to the promise of carbon offsetting, but also how it economically privileges the fossil fuel industry while simultaneously punishing the environments it claims to serve. By purchasing the credits and shelving them, as it were, ‘she prevents these offsets from being used by other entities that would actually emit the pollutants they would have been entitled to produce’ (Linden Citation2011: 65). The acquired credits are then visualized through black-and-white and colour video in the form of volumetric clean air parks carved out of the polluted air space above a city, creating a visual placeholder for what might otherwise be misconceived as intangible units of space. In this way, ‘[t]he virtuality of the project—a “park” in the air can neither be seen nor exist in any stable state—mirrors the invisibility and abstract quality of atmospheric carbon dioxide and, indeed, of climate change itself’ (Demos Citation2012: 193). In an interview with curator Ana Teixeira Pinto on the topic of trade and ownership, Balkin explains how her participatory gesture inaugurates ‘a defence of the atmosphere as commons, set against emissions trading as a new zone of privatization of a global public good’ (Teixera Pinto 2012: 156). Through the project’s engagement with a very active and corporate credit system, the artist invites members of the public into a space where they too can confront and critique ‘the creation of new forms of indebtedness, such as the “structural adjustment” of the sky’ (156).

Fig 2. PUBLIC SMOG OFFSETS TOMORROW TODAY, Billboard, Douala, Cameroon, 2009. Part of Amy Balkin, Public Smog (2004– ongoing). Photo Guillaume Astaix, image Benoît Mangin, courtesy of Amy Balkin

In addition to producing the video component as part of her wider project, Balkin has written letters to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, enquiring whether a private individual might replace a state party if wanting to nominate the earth’s atmosphere for ‘protected environmental status … as a whole system’: that is, a commons (Teixeira Pinto Citation2012: 154). Could the regulations be suspended, she asks, if the territory in question is not bound by geographic borders but is, nevertheless, treated as a commodity to be bought and sold? As a further step, some 90,000 postcards signed by members of the public were sent to Germany’s Minister of the Environment in 2012, with a similar petition to lead a coalition to nominate the earth’s atmosphere as a World Heritage Site in need of protection. The same was done in Australia in 2015. Neither action has produced the desired results in real terms, but they have arguably opened up fields of ecological interrogation formerly out of reach to many of those impacted by smog. Encouragingly, radio silence or unfavourable replies have not swayed Balkin, as these also prove a point: ‘Smog has multiple readings, including as a signifier for a literal obscuring of vision, which can stand in for the legal system, or for market boosterism and hubris’ (Teixeira Pinto Citation2012: 155).

In 2009, Public Smog travelled to Douala, Cameroon, where thirty billboards were erected throughout the city to promote the potential manifestation of clean air parks over the country. The billboards for Public Smog/Douala comprised pristine but honest images of the landscape, horizon and skyscape as the backgrounds for fifteen different declarative texts (e.g. ‘Public Smog Offsets Climate Justice’ and ‘Public Smog Offsets Tomorrow Today’), performing the visual language of advertising within the site-specific context of air pollution mainly caused by road traffic. Here, it is worth reconnecting with Achille Mbembe, who asks, ‘how far away are we really from the time when there will be more carbon dioxide than oxygen to breathe’ (2021: 61)? To my mind, the Douala version of Balkin’s project raises the new materialist theme of transversality, with members of a commons that is determined by industry and consumerism asked, through the capitalist format of the billboard, to consider how the economic promises for tomorrow are frequently juxtaposed and confused with the ecological disparities of today via the real-time effects and rhythms of polluted air over urban space. The signalling of a future clean air park as an alternative to the realities of everyday life at street level presents a problem: if ‘toxicity is located in specific territories and premised upon and reproduced by systems of colonialism, racism, capitalism, patriarchy, and other structures that require land and bodies as sacrifice zones’, then national and socio-economic factors contribute to a wider concept of anthropogenic toxicity (Calvillo et al. Citation2018: 332). By concentrating on the origins and effects of air pollution in cities around the world, Balkin’s eco-critical projects successfully introduce publics or communities to the regimes that govern them.

CITIZEN SENSE

In his seminal book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Rob Nixon charts the twenty-first-century expansion beyond the age of infinite oil towards a state of emergency concerning the exhaustion of fossil fuels and the geopolitical uncertainty surrounding future energy options. Importantly, he investigates how and why individuals have become disconnected from this contemporary crisis when unavoidably caught up in chains of extraction, production and oppression:

[W]hat forces turn belongings—those goods, in a material and ethical sense—into evil powers that alienate people from the very elements that have sustained them, environmentally and culturally, as all that seems solid melts into liquid tailings, oil spills, and plumes of toxic air? (2011: 69)

Here, Nixon is pursuing the notion of the ‘resource curse’, whereby materials that can improve human lives have a detrimental impact on the environment when wasted or transformed as pollutants. The value of ownership, as opposed to the value of agency, points towards ecological breakdown, poverty and violence at both local and national levels. Nixon’s argument is similar to the observation Garrett Hardin makes in ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ when arguing against any ‘technical solution to the problem’ of possible nuclear war, stating that ‘[a] technical solution may be defined as one that requires a change only in the techniques of the natural sciences, demanding little or nothing in the way of change in human values or ideas of morality’ (1968: 1243). Anthropogenic environmental degradation likewise presents ‘a class of human problems which can be called “no technical solution problems”’ (1243). Yet, if top-down technical solutions are misleading and detrimental in effect, might a reconsideration of the philosophical value of agency (techne) at an intentionally quotidian register begin to reverse the resource curse?

Launched in 2013 by Jennifer Gabrys, Citizen Sense is a sociological project that supports collectives or citizens within a local community or public to experiment with technology that allows them to monitor or sense environmental change in their own domestic sphere. Rather than amass the collected data into a scientifically comprehensive case for a ‘technical solution’, the team of researchers and participants are more invested in the subjective pragmatism of everyday ecological attentiveness; their data collection targets specific issues to do with the cohabitation of a space, questioning why some areas of the cityscape are more polluted than others. For Gabrys, governmental monitoring or ‘care can as likely turn to neglect and harm, since instantiations of care may be incomplete and even lead to forms of oversight and inertia’ (2017: 174). The many pieces of information gathered since the project’s inception act less as evidence to present to the authorities than as ‘Data Stories’, with themes ranging from fracking to ‘animal-hacking’; ‘Pollution Sensing’ has been another key area of study, with its focus on air quality in London and elsewhere.

Most of the information collected for urban air pollution involves fieldwork or ‘walkingseminar events’, combining the use of labcreated sensing equipment with a Do-It-Yourself ethos. For example, in 2018, Citizen Sense held a London-based ‘Phyto-sensing’ workshop in which participants visited public gardens designed so that the plants would help to absorb pollutants harmful to humans. A toolkit was then designed that would enable others to replicate such a model as well as monitor air quality using affordable sensors. Similarly, in 2019, the group sought out ten London Air Quality Network (LAQN) monitoring devices in the borough of Lewisham. The goal was to place their own ‘Dustbox 2.0’ device at each site and then compare the consistency of measurements for particulate matter (PM2.5) based on unpredictable environmental fluctuations such as road traffic levels (Citizen Sense Citation2020). Variations in data were minimal, which suggests great potential for a ‘low-tech monitoring kit [to be] used by citizens who seek to understand and act upon environmental problems’ (Gabrys Citation2017: 174). Citizen Sense has continued to combat air pollution through their new ‘AirKit’ project, which again demonstrates the embodied empowerment or proactivity of collectives. ‘AirKit’ disseminates the ‘Dustbox’ toolkit further afield while also tackling the specific conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first London lockdown in spring 2020, ‘Covid Data Stories’ from the Forest Hill area revealed lower levels of nitrogen dioxide in the air, as well as slightly lower levels of PM2.5. From a New Materialist perspective, it is useful to clarify what exactly is meant by ‘agency’ in such a context. Karen Barad explains:

[A]gency is not something possessed by humans, or non-humans for that matter. It is an enactment … [that] does not go against the crucial point of power imbalances. On the contrary. The specificity of intra-actions speaks to the particularities of the power imbalances of the complexity of a field of forces. (Dolphijn and van der Tuin Citation2012: 55)

Thanks to data storytelling, an unexpected interrelation of necessarily conflicting parts is presented. A pandemic and the quality of the air become operatives or agents in a power struggle that directly affects the lived experience of a local environment.

Despite attempts at carbon offsetting, air pollution remains widely unchecked across the globe. Actions like those instigated by Public Smog and those at the heart of Citizen Sense inspire laypersons to encounter and understand this disproportionate aspect of the fossil fuel industry at an accessible scale.

In this context, ‘Pollution Sensing’ becomes a performative acknowledgement of ‘pollution as an environmental event and matter of concern’ (Citizen Sense Citation2020, my emphasis). To put it another way, ‘[p]ractices of documenting and evidencing harm through the ongoing collection of air pollution data are speculative attempts to make relevant these unrecognised and overlooked considerations of the need for care’ (Gabrys Citation2017: 175). Such practices help to maintain alertness when faced with rapidly changing conditions.

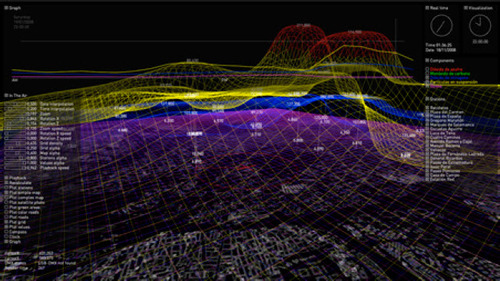

Fig 4. In the Air, Digital Tool: Visualisation, 8MB applet, www.intheair.es, 2021

IN THE AIR

Building on the work of Citizen Sense, affiliate Nerea Calvillo and her collaborators established the In the Air architectural project in 2008. Following a 2009 scandal in which Madrid’s City Council failed to announce the relocation of official air quality monitors, resulting in misinformation about heavy pollution levels, the team designed a web-based public visualization tool that displays changes in emissions based on the available present data. The tool enables the ‘[m]apping and modelling of particulate matter (PM), sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and ozone, looking for spikes and dips in density’ (Calvillo and Thompson Citation2019: 85). If levels of the first four are too high, the air is polluted, while low ozone indicates signs of global warming. The digital visualization tool can reveal connections between these effects by separating the components and charting their presence or absence in targeted areas of the city. Specific contaminant information is also provided. Daily symptoms from high levels of carbon monoxide, for example, might include headaches or dizziness; actions to take might include traffic reduction or a review of domestic heating systems (In the Air 2021).

Using colour-coded aerial topographies, the digital tool illustrates how particulate matter, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone perform within an atmosphere. In the process, it reminds users that:

Like earth, the atmosphere is neither homogenous nor self-same. It is instead layered and multilevelled. It has, in short, its own kind of ‘geography’ or more exactly aeolian zones such that we can even speak of airsheds—regional ‘basins’ without determinate physical boundaries where pollutants move or collect[.] (Macauley Citation2010: 27)

Below the exosphere, the ionosphere and the stratosphere, the stratification of the air above in the troposphere becomes legible and can be thought of in parallel to the movements and habits in the city below. The visualization of this relationship increases understanding of how and why pollution rises in some areas and not in others, and affects the ways in which future urban planning might be conceived and adapted. In Calvillo’s words, ‘[a]t the beginning we just wanted to see how the air performed, but suddenly we began to see how a city breathed’ (Calvillo and Thompson Citation2019: 90). The mapping of pollution flows based on the interpretation of daily data highlights the misuse of open public space as a depository for anthropogenic waste, making it a socio-economic as well as ecological issue. Calvillo continues: ‘[m]aking the levels of air pollution visible allows us to measure the inequalities of a city and to understand the complexities of the urban fabric and the shifting demographic’ (92). Since its implementation in Madrid, the project has also monitored the air quality of Budapest and Santiago and could potentially be adopted in other major cities for site-specific readings of climate change.

Shifting demographics within the cityscape have informed the philosophical approach of In the Air, not least through a crucial feminist perspective that resonates with new materialism. In particular, Calvillo expands upon the notion of ‘toxicity’, which ‘is not only an interaction between bodies, but is also distributed among things, as a contested technopolitical category’ (2018: 374). While the digital tool and resulting model can single out pollutants or imbalanced gases, they also importantly demonstrate how these relate to one another, and reveal how these relations affect human and non-human cohabitants of public space. Calvillo calls this type of observation ‘attuned sensing’: that is, a process that ‘looks at and takes into consideration material, spatial and temporal configurations, and … creates its own regime of perceptibility, which opens up and expands the monitoring form of understanding the toxic and its politics’ (376). Perceptibility begins to reveal experiential contingencies and differing registers of agency and affectivity concerning toxicity. For Astrida Neimanis and Jennifer Hamilton, fluctuations such as this can be understood as ‘weathering’, or that which ‘describes socially, culturally, politically and materially differentiated bodies in relation to the materiality of place, across a thickness of historical, geological and climatological time’ (2018: 80–1). To separate air quality from popular experience through a reliance on cold data delivers an incomplete or non-representative object of study, since bodies and materials share natural as well as forced modes of oscillation.

Tim Ingold’s conclusions for subjectivity and atmosphere show that the interconnection between beings and the materiality of air is indeed complex:

Every living being … stitches itself into the texture of the world along tightly interwoven lines of becoming. This stitching is haptic. But every living being, too, is necessarily immersed in an atmosphere. Is the flesh, then, texture or atmosphere? The answer is that it is, alternately, both. It is atmosphere on the inhalation, and texture on the exhalation. (2012: 85)

Here, an emphasis on embodiment cannot be dissociated from the temporality of being in the world. Studying the responsiveness of all ecological actants or participants within the commons thus supports the comprehension of actual climate change. In his book After the Future, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi makes a similar argument against the abstraction of the virtual and in favour of immediate lived experience, time and actuality, stating that ‘[t]here is no such thing as a time of virtuality, because time is only in life, decomposition, and the becomingdeath of the living. Virtuality is the collapse of the living; it is panic taking power in temporal perception’ (2011: 40). He goes on to criticize the international agreement to reduce 50 per cent of toxic emissions by 2050, noting that such a future-oriented—and therefore virtual—target obfuscates the need for urgent action in the present, actual moment.

The work of In the Air hints at ‘how we might weather differently—better—and act in ways that can move towards such change’ (Neimanis and Hamilton Citation2018: 81). Calvillo succinctly summarizes what I would contend is the achievement of each of the three aerial acts explored above: ‘regardless of the efforts of some agents to make toxicity invisible, through apparently small and disconnected interventions that pay attention to other conditions of air pollution we can act politically in the toxic air’ (2018: 384). By ‘weathering’, or visualizing air quality and mapping its behaviour through the time and space of everyday life, Public Smog, Citizen Sense and In the Air recognize and communicate an eco-critical transversality for the agential commons.

Notes

1 A guide to the carbon credit system can be found here: https://bit.ly/3vIu0W0

REFERENCES

- Balkin, Amy (2021) ‘Projects’, http://tomorrowmorning.net, accessed 9 January 2021.

- Barad, Karen (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Berardi, Franco (2011) After the Future, eds Gary Genosko and Nicholas Thoburn, trans. Arianna Bove, Melinda Cooper, Erik Empson, Enrico, Giuseppina Mecchia and Tiziana Terranova, Edinburgh: AK Press.

- Calvillo, Nerea (2018) ‘Political airs: From monitoring to attuned sensing air pollution’, Social Studies of Science 48(3): 372–88. doi: 10.1177/0306312718784656

- Calvillo, Nerea, Libroiron, Max and Tironi, Manuel (2018) ‘Toxic politics: Acting in a permanently polluted world’, Social Studies of Science 48(3): 331–49. doi: 10.1177/0306312718784656

- Calvillo, Nerea and Thompson, Rose (2019) ‘On air pollution’, in Eco-visionaries: Conversations on a planet in a state of emergency, London: Royal Academy of Arts, pp. 84–93.

- Citizen Sense (2020) Citizen Sense: Investigating environmental sensing technologies and citizen engagement, http://citizensense.net, accessed 9 January 2021.

- Davis, Emily, Limaye, Vijay and Walke, John (2021) ‘EPA halts efforts to clean up levels of unsafe ozone smog’, NRDC, https://nrdc.org, accessed 9 January 2021.

- Demos, T. J. (2012) ‘Art after nature’, Artforum International 50(8): 191–8.

- Demos, T. J. (2016) Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary art and the politics of ecology, Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Dolphijn, Rick and van der Tuin, Iris (2012) New Materialism: Interviews and cartographies, Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press.

- Gabrys, Jennifer (2017) ‘Citizen sensing, air pollution and fracking: From “caring about your air” to speculative practices of evidencing harm’, in Vicky Singleton, Nat Gill and Claire Waterton (eds) ‘Care and Policy Practices’, The Sociological Review 65(2): 172–92. doi: 10.1177/0081176917710421

- Hardin, Garrett (1968) ‘The tragedy of the commons’, Science, 13 December, pp. 1243–8.

- In the Air (2021) In the Air, http://intheair.es, accessed 9 January 2021.

- Ingold, Tim (2012) ‘The atmosphere’, Chiasmi International 14: 75–87. doi: 10.5840/chiasmi20121410

- Lang, Chris (2021) ‘The Durban Declaration on Carbon Trading’, REDD-Monitor, https://bit.ly/3ENK24W, accessed 8 February 2021.

- Linden, Christina (2011) ‘Forward looking’, Fillip 15: 62–9.

- Macauley, David (2010) Elemental Philosophy: Earth, air, fire, and water as elemental ideas, Buffalo: State University of New York Press.

- Mackenzie, Jillian (2016) ‘Air pollution: Everything you need to know’, NRDC, https://www.nrdc.org, accessed 9 January 2021.

- Mbembe, Achille (2021) ‘The universal right to breathe’, trans. Carolyn Shread, Critical Inquiry 47(2): 58–62. doi: 10.1086/711437

- McCormack, Derek (2018) Atmospheric Things: On the allure of elemental envelopment, Durham, NC, London: Duke University Press.

- Neimanis, Astrida and Hamilton, Jennifer Mae (2018) ‘Open space weathering’, Feminist Review 118(1): 80–4. doi: 10.1057/s41305-018-0097-8

- Nixon, Rob (2011) Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Teixeira Pinto, Ana (2012) ‘Atmospheric monument’, Mousse 34: 152–7.

- Wu, X., Nethery, R. C., Sabath, M. B., Braun, D. and Domincini, F. (2020) ‘Air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: Strengths and limitations of an ecological regression analysis’, Science Advances 6(45), 4 November, http://www.advances.sciencemag.org, accessed 7 June 2021.