Abstract

Attempting to distinguish between theatre and performance art, Marina Abramović insisted that, ‘to be a performance artist, you have to hate theatre. Theatre is fake… The knife is not real, the blood is not real, and the emotions are not real. Performance is just the opposite: the knife is real, the blood is real, and the emotions are real.’ Reaching for the most extreme of examples, Abramović couched her argument in the language of violence and mortality to make her point. Strikingly though, while she speaks of knives and blood, she does not mention breath. In ‘Playing with Then and Now: The Liveness of Breath,’ I argue that this is because breath challenges such a simple dichotomy, as the inexorable links between air, breath, life and liveness mean that a focus on breath can highlight new ways of thinking about live performance. More specifically, I explore how three recent performances – the docudrama Black Watch (Gregory Burke, 2006) and two pieces of performance art, Felicitaciones (Eduardo Oramas, 2014), and Running out of Air (Didier Morelli, 2011) – foreground breath and breathlessness, manifestly playing with air, in order to call attention to the shifting sands that underpin live performance, fraying the edge between live and archive, performance and memory, now and then, life and death.

In an attempt to distinguish between theatre and performance art in an interview cited in the Observer in 2010, Marina Abramović insisted that ‘to be a performance artist, you have to hate theatre. Theatre is fake … The knife is not real, the blood is not real, and the emotions are not real. Performance is just the opposite: the knife is real, the blood is real, and the emotions are real’ (O’Hagan Citation2010: n.p.). Reaching for the most extreme of examples, Abramović couches her argument in the language of violence and mortality to make her point. Strikingly though, while she speaks of knives and blood, she does not mention breath, a phenomenon that challenges the simple dichotomy she draws between theatre and performance art and, I suggest, asks us to reconsider the boundaries of live art. In this article, I focus on three distinct performances—documentary drama Black Watch (dir. John Tiffany, 2006) and two performance art pieces, Felicitaciones / Congratulations (Eduardo Oramas, 2014), and Running Out of Air (Part I) (Didier Morelli, 2011)—to establish the ways in which the deliberate and distinct use of breath enables us to rethink the central tenets of live performance. In particular, I examine how it might help us to locate the elusive ‘real’ in documentary drama and theatre more broadly, how it can highlight the trace of live performance and trouble the concept of performance remains, and, finally, how it might illuminate the death hidden in the life of the live.

I. THE BREATH IS REAL

Inaugurating the newly-founded National Theatre of Scotland, Black Watch opened in Edinburgh in August of 2006. A critical and commercial success, the play told the story of the Black Watch regiment of the British army—a regiment disbanded in 2004 after a final deployment at Camp Dogwood, Iraq. Written by Gregory Burke and directed by John Tiffany, the play is shaped around a series of interviews conducted by the playwright with the regiment’s soldiers. The piece is permeated with a sense of loss, as the disbanding of the regiment seems to underline the loss of the individual men— not only the death of their comrades and the loss of the regiment but the ensuing loss of an experience in which they shared. Documentary in style, the production caught the tail end of a boom in documentary drama in early 2000s Britain. Playwright David Hare has been an outspoken advocate of the trend, penning two of the more well-known docudramas of the period, The Permanent Way (2003) and Stuff Happens (2004), but others include Robin Soans’s Talking to Terrorists (2005), Katharine Viner’s and Alan Rickman’s My Name Is Rachel Corrie (2005) and Victoria Brittain’s and Gillian Slovo’s Guantanamo: ‘Honor Bound to Defend Freedom’ (2004). When not expressly concerned with the fallout from 9/11 and the Iraq War, these plays are consistently occupied with political justice and the pursuit of ‘honest’ accounting. As Stephen Bottoms has observed, in the wake of George W. Bush’s and Tony Blair’s ‘War on Terror’, ‘mere dramatic fiction [was] apparently … seen as an inadequate response to the current global situation’ (2006: 57). It was, in other words, a genre selected at the turn of the century for its apparent unfettered access to reality and its truth-telling abilities.

As a result, documentary drama has often drawn attention to the documents that bolster its claim to access the ‘real’. Texts, interviews and recordings are often foregrounded in the final production. Nevertheless, as Carol Martin has argued, bodies—both those ‘of the performers as well as the bodies of those being represented’—are in fact ‘decisive’ to the way in which the form functions (2006: 9). Indeed, as Martin neatly conveys by way of her article title, ‘Bodies of Evidence’, documentary theatre has a tendency to foreground the nature of evidence and the role of bodies to blur any remaining boundary between what Diana Taylor has called ‘the archive and the repertoire’ (2003). While documentary drama can risk an unquestioning commitment to its truth-telling abilities— ‘without a self-conscious emphasis on the vicissitudes of textuality and discourse’ (Bottoms Citation2006: 57)—Burke’s and Tiffany’s production of Black Watch seems alert to these aspects of the form. Constantly seeking different ways in which to remember, the production seems at times both archive and repertoire, grounding itself and its memories in bodies as much as text. Despite its unabashed ‘verbatim’ status— with its replayed interviews and supposedly transcribed text—Black Watch is also punctuated with physical theatre, dance and song. In one segment entitled ‘Fashion’, the central figure, Cammy, is ‘manoeuvre[d …] around the stage’, ‘dresse[d …] into and out of significant and distinct uniforms from the regiment’s history’ (Burke Citation2007: 30). In another, a soldier ‘grabs the Writer’s arm’ and threatens to break it, shouting ‘If he wants tay ken about Iraq, he has tay feel some pain?’ (65).

This interest in the bodies of the performers and their investment in conveying the so-called real and true comes to a head in the production’s dramatic finale:

Music. The bagpipes and drums start playing ‘The Black Bear.’ The soldiers

start parading. The music intensifies and quickens as the parade becomes

harder and the soldiers stumble and fall. The parade formation begins to

disintegrate but each time one falls they are helped back onto their feet by the

others. As the music and movement climax, a thunderous drumbeat stops

both, and the

exhausted, breathless soldiers are left in silhouette.

(Burke Citation2007: 73, my emphasis)

As the music ceases and the lights glare briefly before fading to black, the audience is left not with the sound of silence but with the sound of breathing. But are the soldiers breathless, as the stage directions specify, or is it the actors? It is in fact both. Here, documentary theatre is asserting its liveness. The bodies of the performers are implicated in a vital way—quite literally—as the breath of the actors becomes indistinguishable from that of the characters.

In this way, Black Watch deploys the breath of its performers to challenge the kind of distinction drawn by artists like Marina Abramović who elevate performance art to the status of the ‘real’, while denigrating theatre as its poor and inauthentic cousin. The blood may not be real but the breath certainly is. In a play desperate to remember, to find access to a reality which seems to be slipping ever further away, this final moment uses the insistent liveness of its actors as an access point to the past. In other words, the actors may be performing an approximation of a remembered war they did not fight, but their exertion is quite real, and the attendant breathlessness similarly so. By leaving its audience with this moment of lived and live breathlessness, Black Watch attempts to retrieve the reality of the war not only via the easily archived documents so associated with documentary drama, but through the actors’ vital and embodied connection to the work and to those they portray.

Black Watch draws attention to the ‘real-time presence of toiling performers’ that Jonathan Kalb identifies as common to theatre—specifically, in his argument, ‘marathon theater’—as well as the endurance strand of performance art to which Abramović gestures (Kalb Citation2011: 17). As Kalb explains,

the palpable exertions of living performers striving to breathe life into dramatic artworks for our sake, replenishing our energy with theirs as we watch them, is theater’s signature feature and numerous major theater figures … have pointed out the connection between that physical presence and an awareness of death. (17)

Kalb only half-metaphorically invokes the concept of breath as he reflects on the bodily commitment of these performers and the ways in which their vitality might make meaning, might even make history. The actors in Black Watch dedicate their literal breath to the performative process, implicating their own bodies in the act of remembering and documenting through theatre.

II. BREATH AS REMNANT OR, DOES BREATH REMEMBER?

Eduardo Oramas’s Felicitaciones / Congratulations—performed as part of Toronto’s 2014 7a*11d Festival of Performance Art—is one example of the kind of vital and committed performance art of which Kalb and Abramović speak. The piece consisted of a series of difficult and seemingly futile tasks Oramas had set himself: relighting a cigarette while propped up on only one elbow; pinning the tail on a donkey set 8 or more feet high on the wall; blowing out the candles on a cake located at one end of the former schoolroom while pulling against an elasticated harness anchored in the other wall; drinking an entire family-size bottle of 7 UP with his arms restrained; and, finally, leaping repeatedly to pop balloons high above his head. Each task took a toll on Oramas as he struggled increasingly to complete each exhausting action. Every undertaking was a mental and physical strain, reflected in his repeated panting, pausing and waiting to catch his breath.

Felicitaciones / Congratulations, Eduardo Oramas, 7a*11d, Toronto, Canada. Photos © Isabel Stowell-Kaplan

I focus here on the birthday cake episode, for while each activity required a marshalling of breath, none other had quite the self-conscious quality of that one task. Beginning by lighting candles on the cake, Oramas walked to the far end of the room and placed the lighted cake on the ground. Returning to the opposite end of the space, he then harnessed himself to what appeared to be a sort of black bungee cord attached to the wall. He then proceeded to run from one side of the room to the other, tethered always to the wall by the cord, in order to blow out the candles on the cake. The candles, it quickly became clear, were self-relighting and so this went on for some time. Oramas would run, blow out as many candles as he could before typically pausing, sometimes kneeling, sometimes lying flat out on the ground, breathing heavily, as he prepared for another run. Despite the clear strain on Oramas, the mood in the room was joyous as the audience cheered, whistled, stamped and clapped during each attempt; each time Oramas needed enough breath not only to reach the candles but, once there, enough breath left to blow them out. The performance quickly became a self-conscious exercise in breath management, with Oramas’s heavy breathing seemingly both the remnant of his prior attempt and preparation for his next.

Peggy Phelan’s now oft-quoted assertion that ‘performance’s only life is in the present’ would suggest that there is something mournful about Oramas’s performance here (1993: 146). As André Lepecki argues, such an ephemeral trend in performance and dance theory, as articulated especially by Marcia Siegel in At the Vanishing Point, implies a ‘mode of being-in-the-world that would amount to nothing more than a lifetime of rehearsing and performing endless successions of living burials’ (2006: 125). Read in this light, the futility of Oramas’s tasks only serves to underscore the latent melancholia of his performance. Lepecki, however, goes on to challenge the assumptions underlying such a model, citing what he sees as the unsustainable practice of mistaking the ‘now’ for the ‘present’ (130). Rebecca Schneider similarly resists the assumptions about performance’s ephemeral nature that underlie such a reading, and her response offers particular insight into Oramas’s performance—what his breath might mean and how it might remember and remain.

In Performing Remains, Schneider argues that accepting performance as necessarily ephemeral is to capitulate to what she calls ‘the logic of the archive’ (2011: 98). In so doing, she suggests, we risk ignoring ‘other ways of knowing, other modes of remembering, that might be situated precisely in the ways in which performance remains, but remains differently’ (98). As with the breathless performers of Black Watch, Oramas’s breath becomes its own trace, its own performance ‘remains’. Remaining ‘differently’, Oramas’s performance is remembered in the presence of his breath. Moreover, if, like Schneider, we posit the live performance as exceeding and succeeding the (pre-)record-ed text (90)—or in Oramas’s case, the blueprint for his tasks or performative actions—we trouble our understanding of just which part of Oramas’s performance is live and which the record. Oramas’s breath need not be the remnants of the live and lived performance but instead becomes the live itself. In this way, Oramas’s performance upsets the relationships that we might assume to exist between the notions of live, recorded, present and remembered as his breath becomes the live (and living) trace of the recordable action that was his earlier performance.

III. ‘AS I LAY DYING’

The question not only of when a live performance exists but what exactly it is that makes it live is something that has occupied performance studies scholars for decades. In one attempt to grapple with this, Rebecca Schneider usefully notes that if we look up the word ‘live’ in The New Oxford American Dictionary we are confronted with definitions in the negative. We are, she observes, ‘given two antonyms of note: “dead” and “recorded”’ (90). Felicitaciones / Congratulations challenges how we might understand the relationship of live vs. recorded, and I conclude by considering the other fatal pairing. Specifically, I examine how the twin notions of liveness and death are played out in Didier Morelli’s 2011 performance piece, Running Out of Air (Part I).Footnote1

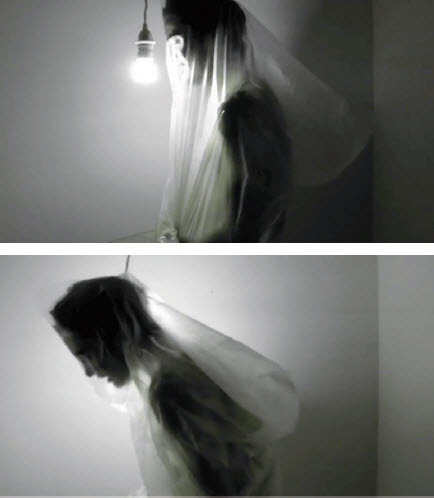

In the performance, Morelli covers his head and chest in a clear plastic bag which he holds close against his body. Repeatedly reciting William Faulkner’s title ‘as I lay dying’ Morelli struggles against the diminishing oxygen supply in the bag. Noticeably gasping for air, he eventually releases his hold on the bag, allowing oxygen back in as he doubles over trying to catch his breath. The visceral quality of the piece always surprises me. It has an affective power that hinges on the interdependence of life and death, live and dead. It highlights the twinning between both promise and threat that Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth argue is foundational to affect and affect theory. These, Gregg and Seigworth suggest, operate with a promissory quality, that ‘capacities to affect and to be affected will yield an actualized next or new that is somehow better than “now”’. As they explain, however, these ‘seeming moments of promise can just as readily come to deliver something worse’, as ‘one of the most pressing questions faced by affect theory becomes “Is that a promise or a threat?”’ ‘No surprise’, they conclude, that ‘any answer quite often encompasses both’ (2010: 9–10). This affective doubling is mirrored in Morelli’s piece in the twinned concepts identified by Schneider—‘live’ and ‘dead’.

The sensuous vulnerability of Morelli is captured in his breathlessness—one quite different from that of Oramas or the actors of Black Watch. Here Morelli seems to offer the promise of total liveness but one offered at the risk, or, to use Gregg’s and Seigworth’s language, ‘threat’ of death. The fragility of this liveness, one at risk always of falling into memory, is what demonstrates its vitality. Jonathan Kalb suggests, as cited above, that theatre’s very meaning is embedded in ‘the palpable exertions of living performers striving to breathe life into dramatic artworks for our sake’, and, what is more, that there is an oft-noted connection between ‘that physical presence and an awareness of the omnipresence of death’ (2011: 17). Running Out of Air (Part I) is so decidedly live because of its overt connection with death. Morelli’s struggle for air shows up the risk of death inherent in the live form—promising life and threatening death at once. And yet it is not simply that life and liveness exist at some precarious edge that is death and disappearance, what Marcia B. Siegel describes as the ‘vanishing point’, in her book of the same name. Instead, as André Lepecki argues, in the conclusion to Exhausting Dance, perhaps ‘to disappear into memory is the first step to remain in the present’ (2006: 127). If this is so, then Morelli’s threatened disappearance into memory may be the very way to remain present and so live.

As Fintan Walsh observed in his recent Theatre Research International editorial, ‘Between Breaths’, despite the exhortations of ‘mindfulness guides’ to ‘breathe in and out slowly’, COVID and the Black Lives Matter movement have shown that ‘breathing itself has become the problem’ (2020: 227). These are, moreover, questions that are not unfamiliar in creative practice and performance history. As Walsh concludes, citing both Samuel Beckett’s Breath (1969) and the work of late theatre practitioner and scholar Phillip Zarilli, ‘creative production, we might say, hangs in the balance of exchanging breath’ (229). More specifically, the inexorable links between air, breath, life and liveness mean that a focus on breath can highlight new ways of thinking about live performance. By calling attention to the use of breath, and specifically the state of breathlessness, the pieces I have examined here challenge our ideas of what constitutes living, liveness, presence and trace. Black Watch locates memory and the elusive ‘real’ of docudrama not so much in the text as in the breathing bodies of its performers. The heavily breathing Oramas of Felicitaciones / Congratulations reorders the sequence of live performance, citing the trace as the performance itself, and Didier Morelli’s Running Out of Air (Part I) figures the threat of death in the fragile live. By manifestly playing with air, each work calls attention to the shifting sands that underpin live performance, as the spectacular and laboured breathing of each performer helps to fray the edge between live and archive, performance and memory, now and then, life and death.

Notes

1 As indicated by the title, this piece actually exists in two parts. For clarity’s sake I will be referring to this first one, recorded in Morelli’s apartment in Toronto in 2011, rather than the somewhat different version performed subsequently at the University of Toronto.

REFERENCES

- Bottoms, Stephen (2006) ‘Putting the document into documentary: An unwelcome corrective?’ TDR: The Drama Review 50(3): 56–68. doi: 10.1162/dram.2006.50.3.56

- Burke, Gregory (2007) Black Watch, London: Faber and Faber Limited.

- Gregg, Melissa and Seigworth, Gregory J. (2010) ‘An inventory of shimmers’, in Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth (eds) The Affect Theory Reader, Durham, NC, London: Duke University Press, pp. 1–25.

- Kalb, Jonathan (2011) Great Lengths: Seven works of marathon theater, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Lepecki, André (2006) Exhausting Dance: Performance and the politics of movement, New York: Routledge.

- Martin, Carol (2006) ‘Bodies of evidence’, TDR: The Drama Review 50(3): 8–15. doi: 10.1162/dram.2006.50.3.8

- O’Hagan, Sean (2010) ‘Interview: Marina Abramović’, Observer, n.p., 3 October.

- Phelan, Peggy (1993) Unmarked: The politics of performance, New York: Routledge.

- Schneider, Rebecca (2011) Performing Remains: Art and war in times of theatrical reenactment, New York: Routledge.

- Siegel, Marcia B. (1972) At the Vanishing Point: A critic looks at dance, New York: Saturday Review Press.

- Taylor, Diana (2003) The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing cultural memory in the Americas, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Walsh, Fintan (2020) ‘Editorial: Between breaths’, Theatre Research International 45(3): 227–9. doi: 10.1017/S0307883320000231