Abstract

Through an analysis of the video work, Cloud Studies (2020), by the multidisciplinary research agency Forensic Architecture, this article reflects on how the inherent relation of life to air has been endangered by toxicity. In particular, Drawing on Cloud Studies eight investigations on the pernicious effects of toxic clouds on people and ecosystems, this articles examines the connectedness of global atmospheres that air violation exposes. Central to the discussion is a consideration of the emotional as well as physical consequences of such violations, whereby breathing itself is turned into a means of oppression. To counteract what can be regarded as today's ‘politics of breathing’, we argue for a performative and relational response to such politics enacted through the breathe itself.

There is no doubt that the skies are closing in.

But we hold in-common

the universal right to breathe.

Achille Mbembe (Citation2020)

This epigram from Achille Mbembe’s essay ‘The Universal Right to Breathe’, published in April 2020, concludes the video work Cloud Studies (2020) by Forensic ArchitectureFootnote2. A multidisciplinary research agency, including architects, artists, filmmakers, lawyers, software developers and journalists based at Goldsmiths, University of London, Forensic Architecture supports human rights groups and other agencies by applying architectural methodologies to investigate ecological and human rights violations (Weizman Citation2017: 9). Developed for the exhibition ‘Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics’, at ZKM, Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany (23.5.2020–8.8.2021), Cloud Studies comprises eight investigations that, as the title suggests, focus on clouds or, more precisely, on toxic clouds—whether those produced by arson, the spread of herbicides, the deployment of chemical weapons, the use of tear gas or by the invisible emission of methane caused by fracking. Organized according to the chemical composition that characterizes each of these cloud formations, Cloud Studies offers us a ‘new kind of cloud atlas’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over), one in which the form and composition of clouds are studied to navigate the collusion of political and economic powers, of ecology and human rights worldwide, from the Gaza Strip and Syria to an oil facility in Argentina and a forest fire in Indonesia, from the demonstrations in Tahrir Square in Cairo in 2011 and those in Hong Kong in 2020 to the virtual media cloud of digital information. Forensic Architecture’s investigations of these diverse clouds are woven together in this video work by the account of clouds’ elemental formation, shape and drift and the kind of knowledge that can be harnessed from them. The video moves across scale and time to unravel the solidarity and action of people who worldwide claim their ‘universal right to breathe’.

By tracing Forensic Architecture’s investigations of the physical becoming and transformation of toxic clouds and of their consequences for people and ecosystems, I shall reflect on the intersubjective relations that breathing establishes through air and how such relations are disrupted by contamination—to be understood as both chemical and affective. Extending Tim Ingold’s observation on the inherent ‘aerial dimension of bodily movement and experience’ as ‘ways of being and knowing’ (2010: 5131), I shall argue for an embodied and performative response to what I refer to as the politics of breathing.

TOXIC CLOUDS AND AFFECTIVE FORMATIONS

In his home, coughing as he speaks, the witness of an air bomb in Gaza describes its effects to the Forensic Architecture’s team in London.

The voice-over in Cloud Studies comments, it is as if ‘he was breathing his own house’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). On screen, we see the smoke cloud of an explosion ().

Figure 1. Still from The Bombing of Rafah, 2015 (Cloud Studies, 2020). Photo © Forensic ArchitectureFootnote1

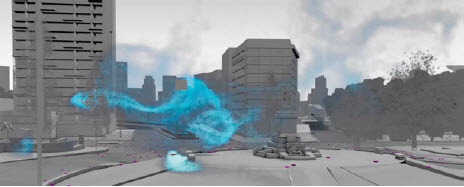

Related to an investigation conducted during Israel’s bombing campaign in the Gaza Strip in 2008, Forensic Architecture’s contemporary cloud atlas opens with cement as a contaminating matter. It shows images of grey smoke saturated with the micro particles of dust of all the materials that the conflagration disintegrates. As the voice-over explains, ‘bomb clouds contain everything that the building once was: cement, plaster, plastic, glass, timber, fabric, paperwork, medicines, sometimes parts of human bodies’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). All these materials are breathed by those surrounded by the smoke cloud. We ‘inhabit’ air as the matter and medium that enables life and in which life happens (Ingold Citation2010: 5122–4). We are, in other words, ‘immersed in the flows, forces, and pressure gradients’ of its currents and such immersion is also the condition for interaction (5132). Toxic clouds occur within air’s immersive flows and alter the physical and figurative conditions of interaction as they poison the environments that people, animals and plants inhabit, and by extension life itself and the freedom that air can symbolize. Like weather clouds, toxic clouds form, move, change and dissipate. Their toxic traces are the only sign that can substantiate their lingering presence in the atmosphere. By studying such traces and relating them to their shape and drift as well as to other information related to meteorological conditions, wind directions or temperature changes, and how these factors affect the manifestation and persistence of a cloud, Forensic Architecture generates digital models and maps of toxic clouds’ formation and dissipation in the atmosphere. These are matched by the detailed analysis of the chemical composition of each toxic cloud and of environmental and health damage caused to provide evidence of contaminating effects. Throughout Cloud Studies, photographs and extracts of videos taken on location are intersected with cloud images and shown alongside the digital simulations and reconstructions developed by Forensic Architecture and used for analysis and projection. Hence, Cloud Studies includes different forms of visualization and articulation of information, different ways of experiencing and knowing.

Transient and ever-changing, clouds exceed both classification and representation. Modern science attempted to catalogue them according to their vaporous shapes, while painters tried to capture their fleeting movement and evanescent relations to light. As Cloud Studies suggests, clouds are ‘limit conditions … always double. Seen from the outside they are measurable objects; seen from within they are experiential conditions of optical blur and atmospheric obscurity. Our cloud studies likewise meander between shape and fog, between analysis and experience’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). The historical painterly attempt to capture the transience of meteorological clouds thus translates into that of capturing the material formation and transformation of toxic clouds as the latter is ‘governed by non-linear and multi-casual logic’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). Such logic is articulated collaboratively, drawing on video footage posted by people experiencing the toxic clouds with information collated from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other sources, data analysis and digital simulation, suggesting the multi-layered approach of Forensic Architecture. Clouds are, however, more than an object of study, as they happen in dynamic relations with existing environmental conditions, with places and people. Their experiential effect is complex and pervasive. In Gaza, Israel airsprayed herbicides containing glyphosate that destroyed crops, putting at risk the livelihood of the local inhabitants who depend on farming, and targeted the region with white sulphur (sulphur dioxide) rockets that produced mysterious, white luminous clouds that burnt on contact (). Indeed, ‘[i]n Gaza’—as remarked in Cloud Studies—‘the intoxication of the air supports the occupation of the ground’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). Fear lingers in the atmosphere, no less toxic than chemical contamination.

Figure 2. Still from Herbicidal Warfare in Gaza, 2019 (Cloud Studies, 2020). Photo © Forensic Architecture

Peter Sloterdijk has introduced the notion of violence, in other words, contaminates one’s own ability to imagine: ‘People who are anticipating a fearful event or trauma of some kind, or violence of any kind, or any kind of threat, are not just idly picturing it; they are to some extent living that experience’ (Loveday in Grief Citation2020). An investigation related to a chemical attack in Aleppo, Syria, on 8 December 2018, shows footage shot on the ground as we hear the voice of a man saying ‘My family is inside. Go on the roof! Close the doors, close the doors! He is dumping chlorine … no one should breathe’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). Chlorine affects sense perceptions, causing blurred vision, difficulty of breathing, vomiting and excess salivation (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). To these physical symptoms we could add fear and hypervigilance as consequences of the trauma caused by the bombing, which mostly attacked civilians. The visible clouds that Forensic Architecture studies are thus shadowed by other clouds, those caused by the internal formations of traumatic ‘atmoterrorism’ to suggest the military control of air space and atmospheric violence (Sloterdijk Citation2009: 25–6, see also Schwab Citation2010; Adey Citation2015). Threats ‘experienced from and through airspace’ have proved to have serious psychological impact on civilians ‘as they cause hypervigilance affecting not only how one lives in the present but also how one imagines the future’ (Grief Citation2020). The trauma caused by atmospheric memories and the vivid sensorial imagining of the mind drawn by fear.

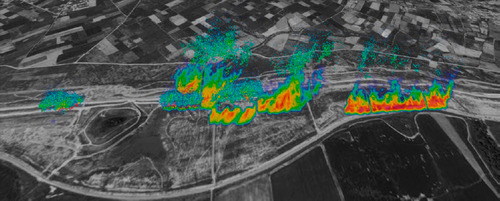

Atmospheric control and violence today extend beyond warfare to include ecological harm and the deployment of tear gas, indicating how air has been transformed into a threat and ‘an instrument to govern the very condition of life’ (Nieuwenhuis Citation2018: 84) by upsetting and putting at risk our interaction with the atmospheric environments in which we live. Toxic clouds are the liminal, transient and diffuse manifestation of such a threat because they form and dissipate at the intersection of ecological and political violence. For over a year, Forensic Architecture studied, monitored and virtually reproduced the large cloud of carbon monoxide caused by the burning to clear a forest in Kalimantan, Indonesia, in 2015. The cloud drifted north and westward, affecting other areas in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, then reaching the northern parts of Thailand and Vietnam, causing an estimated 100,000 premature deaths (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). Another investigation focused on the poisonous emission of methane from a fracking facility in the area of Vaca Muerta in Argentina, known for its oil fields. Only detectable with infrared cameras, methane, together with other toxic emissions, contaminated the living environment of the indigenous Mapuche community by endangering their livelihood but also upsetting their very relationship with the land and the atmosphere (Moafi Citation2020).

Indeed, as Forensic Architecture comments, ‘[m]obilized by state and corporate powers, toxic clouds colonize the air we breathe across different scales and durations, from urban squares to continents and from incidences to epochal latencies’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). By showing both the material and affective interference of poisonous gases, Cloud Studies draws connections among different forms of contamination, involving the viewer in the analysis and experiential conditions of each cloud, and across the development of the work through their different affective formations and drifts. However, as noted in the video,

today’s toxic fog breeds lethal doubt, and clouds shift once more from the physical to the epistemological. When naysayers operate across the spectrum to deny the facts of climate change just as they do of chemical strikes, those inhabiting the clouds must find new ways of resistance (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over).

In these toxic atmospheres, protest is also met with toxic clouds. Cloud Studies brings to bear the large clouds generated by conflict and ecological contamination with those of tear gas that disperse on ground level in cities as diverse as Cairo, Istanbul, Hong Kong and Santiago. Worldwide, demonstrators are subjected to ‘atmospheric governance’ that ‘has in a relatively short time become the preferred technology of state power to discipline, punish or immobilise breathing bodies’ (Nieuwenhuis Citation2018: 89) ( and ).

Figure 3. Still from Tear Gas in Plaza de la Dignidad, 2020 (Cloud Studies, 2020). Photo © Forensic Architecture

Figure 4. Still from Tear Gas in Plaza de la Dignidad, 2020 (Cloud Studies, 2020). Photo © Forensic Architecture

Banned in warfare, tear gas is commonly used by police forces and, though supposedly non-lethal, it can affect the respiratory system, causing breathing difficulties, pulmonary oedema, convulsions and danger of impaired breathing. In Cloud Studies, we hear the voiceover’s listing of the symptoms caused by a tear gas called Triple Chaser, which has been the focus of one of Forensic Architecture’s investigations, as we see digitally rendered images of colourful canisters of the gas appearing on screen accompanied by the background soundtrack of Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs. The accumulation of canisters suggests the growing formation of an imaginary cloud pervading the urban atmospheres of streets and squares, roundabouts and frontierborders across the world. Such clouds, as the chlorine attacks in Syria whereby ‘each bomb is also an information bomb’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over), give rise to a ‘media storm’ of images and contrasting analyses, thus further obfuscating ‘evidence of crimes and dissipating denial through discord and dislocated online debates’ (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over). In this gaseous and mediatic condensation that displays the ‘porousness of global borders and the corruptibility of air’ (Zeichner Citation2020: 1), toxic clouds are like ‘a cross-border condition of suffocation’ in which ‘the inhabitants of tear gas around the world’ move, claiming their right to breathe (Forensic Architecture Citation2020, voice-over).

INHABITING TOXIC CLOUDS

Through the analysis of the sensory traces of toxic clouds, Forensic Architecture draws what can be envisaged as a dynamic atlas of cloud formations that shows the connectedness of global atmospheres. As Marijn Nieuwenhuis argues of air’s chemical composition, toxic clouds reveal ‘a history and a politics in itself’ (2015: 91), since they pollute the atmosphere with chemicals and affects capable of throwing people and entire ecosystems ‘into different, new and old airs’ that ‘transcend complicated and diverse geographies of power’ (91). For people in Gaza and Syria during airstrikes, but also afterwards as the effects of bombings continue in the foreboding and fear that imbue the atmosphere of these places, for the Mapuche people in Argentina as oil fracking in the region continues, and those who live in the areas where the fire clouds in Indonesia disperse, these clouds inexorably contaminate the air they inhabit and breathe and the soil in which crops grow and animals graze. In this sense, toxic clouds are experiential formations that upset one’s ordinary and intimate immersion in air, subverting its figurative associations with openness and freedom by imbuing it with oppression. Nieuwenhuis situates the politics of breathing in the everyday as well as in situations of protest and conflict. Such politics is concerned with ‘the concealed thing we unknowingly inhale, exhale and share with others and the world on an everyday basis’ (Nieuwenhuis Citation2015: 92), thus exposing the vulnerability of breathing itself, as breathlessness and suffocation.

This raises the question of what kind of resistance can be envisaged in their mist. In her discussion of violence and forms of self-defence, Elsa Dorlin maintains that oppression persists in the bodies who suffer it as negative cognitive behaviours and fearfulness. Fear manifests as hypervigilance and anxiety, while cognitive and behavioural self-defensive attitudes include bodily postures and movements meant to lessen, deflect, avoid or dissipate oppression by making oneself almost invisible (Dorlin Citation2017: 175). Breathlessness—whether considered physically, psychologically or figuratively—can be understood as an embodied acquired response to oppression and as an attempt to lessen its stronghold by figuratively withdrawing from air. It can also be regarded as a sign of anxiety, suggesting the hypervigilance caused by trauma (Albano Citation2022). Breathlessness further stands for the undermining of notions of freedom and expression that are commonly associated with breath, and for the disruption of ways of inhabiting air. In this sense, breathlessness relates to Judith Butler’s recognition of the political dimension of vulnerability and how politics exposes the precarity of bodies, their dependence on the protection and the recognition of their basic needs (Butler Citation2012: 148), of which the need for air is fundamental. However, for Butler, vulnerable bodies—bodies who are breathless—also enact resistance, thus presupposing a form of vulnerability that opposes precarity (Butler Citation2016: 24).

Butler suggests a relational and performative understanding of vulnerability that takes into account the experiences and emotions that affect the individual: ‘vulnerability is a kind of relationship that belongs to that ambiguous region in which receptivity and responsiveness are not clearly separable from one another, and not distinguished as separate moments in a sequence’ (25). We are reminded of how toxic clouds also exist at the uncertain boundaries of event and experience, of substantiality and haziness, of matter and affect. Vulnerability of breathing thus ensues within the field of interaction of bodies, environments and toxicity as well as of politics and affect. For Butler, resistance emerges from vulnerability as ‘those practices of deliberate [bodily] exposure to police or military violence’ (26). Protesters who are not deterred by the risk of being exposed to tear gas can be regarded as an instance of resistance that stems from the body’s own vulnerability to breathlessness, but also from the suffocation of liberties that the use of tear gas symbolizes under the supposed claim of being a means to secure or re-establish civic order. When Palestinians raise clouds of smoke that profit from the wind that pushes them in the direction of the Israeli border, we recognize another form of resistance emerging from the breathlessness that Palestinians experience at the hands of the Israeli’s authorities, whereby breathlessness is both an attack on the body and on another people’s right to exist in the same territory. The same could be said of the Mapuche people, marching for the safety of their land in a cloud of tear gas. Paraphrasing Cloud Studies’ voice-over, all those bodies and the many others affected by toxic clouds across the globe ‘hold in-common’ their ‘universal right to breathe’ as a resistance to dominance perpetrated through toxic clouds.

Cloud Studies shares such performative resistance in the formal and thematic associations that weave Forensic Architecture’s investigations together. In such a way, across chemical toxicity and its affective resonances, gaseous clouds and experiential breathlessness, Cloud Studies draws us within the interlinked forms and shapes of today’s politics of breathing and the ‘negative commons’—to use Forensic Architecture’s phrase—they generate to create another common, that of the work itself. Cloud Studies thus acts as a performative space of articulation where toxic clouds and their affective dynamics can be understood and mobilized to reclaim the air we breathe.

Notes

1 I would like to thank you, Forensic Architecture, for assisting me with illustrations

2 An extended discussion of Forensic Architecture’s Cloud Studies appeared in Caterina Albano, Out of Breath: Vulnerability of air in contemporary art, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

REFERENCES

- Adey, Peter (2015) ‘Air’s affinities: Geopolitics, chemical affect and the force of the elemental’, Dialogues in Human Geography 5(1): 54–75. doi: 10.1177/2043820614565871

- Albano, Caterina (2022) Out of Breath: The vulnerability of air in contemporary art, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Butler, Judith (2012) ‘Precarious life, vulnerability, and the ethics of cohabitation’, in Journal of Speculative Philosophy 26(2): 134–51. doi: 10.5325/jspecphil.26.2.0134

- Butler, Judith (2016) ‘Rethinking vulnerability and resistance’, in Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti and Leticia Sabsay (eds) Vulnerability in Resistance, Durham, NC, London: Duke University Press, pp. 12–27.

- Dorlin, Elsa (2017) Se défendre: Une philopsophie de la violence, Paris: Zones éditions le découverte.

- Forensic Architecture (2020) Cloud Studies, https://bit.ly/3OHVKmv, cloudstudies, accessed 29 October 2021.

- Grief, Nick (2020) ‘The airspace tribunal and the case for a new human right to protect the freedom to live without physical and psychological threat from above’, Digital War 1: 58–64, DOI: 10.1057/s42984-020-00023-w.

- Ingold, Tim (2010) ‘Footprints through weather-world: Walking, breathing, knowing’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16(1): S121–S139. I. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01613.x

- Mbembe, Achille (2020) ‘The universal right to breathe’, trans. Carolyn Shread, Critical Enquiry, April, https://bit.ly/3vFfkac, accessed 19 October 2020.

- Moafi, Samaneh (2020) 'Terrestrial University: Cloud Studies', ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, https://bit.ly/3xR2SXE, accessed 23 October 2020.

- Nieuwenhuis, Marijn (2015) ‘Atemwende, or how to breathe differently’, Dialogues in Human Geography 5(1): 90–4. doi: 10.1177/2043820614565876

- Nieuwenhuis, Marijn (2018) ‘Atmospheric governance: Gassing as law for the protection and killing of life’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36(1): 78–95. doi: 10.1177/0263775817729378

- Schwab, Gabriele (2010) Haunting Legacies: Violent histories and transgenerational trauma, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sloterdijk, Peter (2009) Terror from the Air, trans. Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran, Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Weizman, Eyal (2017) Forensic Architecture: Violence at the threshold of detectability, New York: Zone Books.

- Zeichner, Eleanor (2020) ‘The examined sky’, in Forensic Architecture, Cloud Studies: Responses to the cloud, pp. 1–3, https://bit.ly/3khwnd3, accessed 23 October 2020.