Abstract

This article investigates the versatile embodiment of touch in the sensory-aesthetic construction of piano performance. The sensorial interactions enmeshed in piano playing distribute a peculiar interaction between touch and sound, which can be comprehended as two kinds of pianistic touch – the physical touch and the affective touch. In the synthesis, or symbiosis, of these two kinds of touch, piano performance epitomizes a sensory-aesthetic continuum to transmit its force beyond perceptible spatial-temporal boundaries. This article argues that the tactile-sonic relationship in piano playing manifests the performative power of music to formulate new modes of feeling and understanding. This argument is explored in three stages. The first stage utilises two treatises, Steven Connor's ‘Edison's teeth’ (2001) and Simon Waters’ ‘Touching at a distance’ (2013), to explicate how touch enables the production of musical sound and how music can be received as tactually oriented sensations. The second stage introduces the piano as an exemplary instrument of touch in the contexts of scientific studies and relevant cultural history. The third stage uses two novelistic texts as heuristics to explore how pianistic touch is enacted performatively to engage with the aural, visual, somatic and visceral sensations. Both Thomas Mann's ‘Tristan’ (2009 [1903]) and Forster's A Room with a View (2012 [1908]) testify to how fictional presentations of piano playing can provide fertile loam to reappraising pianistic touch beyond the ordinary musical context. Overall, as performed in a range of pianistic settings, the multivariant senses of touch provide productive perspectives for re-constructing what prior categories of senses and sensations could not consider. This article will thus be conducive to a quest for new forms of creativity underlying the performance and performativity of pianistic touch.

PRELUDE

This article investigates the versatile embodiment of touch in the sensory-aesthetic construction of piano performance. The sensorial interactions enmeshed in piano playing distribute a peculiar interaction between touch and sound. The idiosyncrasy of this sonic–tactile relationship can be fleshed out by interpreting two kinds of pianistic touch—the physical touch and the affective touch. Piano performance hinges primarily on communicating the pianistic sound, which is contingently constructed by tangible physical touch. The tactile interactions between the pianist and the piano, including the dynamic surface contact between the two, the kinaesthetic perceptions of movements and mechano-proprioceptive responses, produce the perceptible qualities of pianistic sound.

However, there is more in the haptic communication underlying what we perceive as piano playing than the tactile exchange between the performing pianist and the sounding instrument. The corporeal expression and movements in piano playing, fused with the embodied musical sound, produce an ephemeral affective tone,Footnote1 which stimulates mood and feelings in the aesthetic reception of music. Specifically, the affective tone of music touches back and acts on the human body, creating the affective touch ‘through the ebb and flow of its pulse and rhythm … gestures and sighs … tensions and resolutions’ in an organic process (Davies Citation2003: 114). The affective touch can therefore be conceived of as tactile-aesthetic sensations that at once transcend direct bodily contact while showing the body in touch with itself. In the production of piano performance, the membrane between these two kinds of pianistic touch becomes questionably thin. It is in this synthesis, or symbiosis, of the two that piano playing can transmit its physical and affective forces beyond perceptual spatial-temporal boundaries.

Existing scholarships in historical musicology, instrumental studies and musical performance science shed light on the two kinds of pianistic touch. Through the lens of multiple disciplinary fields, piano playing can be construed as enlivening a range of tactually produced effects that blend palpable bodily sensations with intangible aesthetic modes of perception. I argue that piano performance, at once invoking physical and affective touch, epitomizes a sensory-aesthetic continuum that manifests the performative power of music. By performative, I refer to Nicholas Cook’s idea of ‘musical performativity’, which denotes music’s capability to formulate new perceptual modes of feeling and understanding rather than simply representing what is acoustically out there in the world (2021:22–3). Within the scope of this article, I aim to build on the expanding knowledge discourse to re-evaluate the performativity of pianistic touch in the scientific, artistic and literary contexts; my intellectual enquiry will be conducive to the quest for new forms of creativity underlying piano performance and thus contributes to the burgeoning field of music performance studies.

The article comprises three parts to enquire the propositions dialectically. The first section utilizes two treatises to propound how touch enables the production and reception of musical sound. Steven Connor’s ‘Edison’s teeth: Touching hearing’ (2001) illuminates the contingent construction of sound through a tactility that is at once corporeal and immaterial. Building on Connor’s idea, Simon Waters elaborates how music avails itself not only of ‘hearing at a distance’ but also of ‘touching at a distance’ and ‘feeling at a distance’ (2013: 130). The synergy of touching, hearing and feeling justifies how music can be received as tactually oriented sensations. The second section introduces the piano as an exemplary instrument of touch in a wider disciplinary sense. Scientific studies disclose that piano playing entails tactility beyond the pianist's dexterous hands and tactile mechanisms applied to string and percussive instruments. The relevant cultural history indicates the transgressive manifestation of pianistic touch at the socio-sexual periphery, problematizing the scientific perimeters of touch. The third section uses two novelistic texts as heuristics to explore how pianistic touch is enacted performatively to engage with the aural, visual, somatic and visceral sensations. Both Thomas Mann's 'Tristan' (2009 [1903]) and Forster's A Room with a View (2012 [1908]) signal new modes of perceiving the tactile qualities underlying the aesthetic playing and listening of piano music. As the two works attest, fictional presentations of piano playing can provide fertile loam to reappraising pianistic touch beyond the ordinary musical context.

TOUCHING SOUND: THE PHYSICAL AND AFFECTIVE TOUCH IN MUSIC PERFORMANCE

How are tactile senses involved in the production and reception of musical sound? Before sending directives for the tactile manoeuvre of musical instruments, the brain takes neurological inputs via the somatosensory system that sustains the physical sense of touch across the human body (Hayward Citation2018: 29-30). However, the physiological mechanism of touch is insufficient to explain how musical sound can be produced and received as touch. Further inspection of the idiosyncratic interrelations between sound and tactility, or hearing and touch, can illuminate the synergistic sensory exchange in music-the music sound is constructed by and transmitted as tangible physical touch, while the affective touch transduces intangible emotive sensations beyond bodily limits.

In 'Edison's teeth: Touching hearing' (2001), Steven Connor broaches the tactual production of sound. He puts forward the proposition that the properties of sound that we perceive via hearing are constructed on a contingent tactile basis:

One apparent paradox of hearing is that it strikes us as at once intensely corporeal-sound literally moves, shakes and touches us-and mysteriously immaterial … Perhaps the tactility of sound depends in part on the fact of this immaterial corporeality, because of the fact that all sound is disembodied a residue or production rather than a property of objects. When we see something, we do not think of what we see as a separate aspect of it, a ghostly skin shed for our vision. We feel that we see the thing itself, rather than any occasion or extrusion of the thing. But when we hear something, we do not have the same sensation of hearing the thing itself. This is because objects do not have a single, invariant sound, or voice. How something sounds is literally contingent, depending upon what touches or comes into contact with it to generate the sound. We hear, as it were, the event of the thing, not the thing itself.

According to Connor's quote, what we hear as the musical sound hinges on a tactility that is at once in physical proximity to the sounding object while being disengaged from a stable relationship with the material object that emits the sound. It can be inferred that the performatives of touch can reconceptualize what we perceive as the consistent intrinsic sound of an object-the 'single, invariant sound' does not exist· it is a fabricated ideal contingently construc;ed by the performance of touch. While touch shapes sound as performed tactile effects, the sonic attribute of an object can only be perceived as a contingent event, that is, 'what touches or comes into contact with it to generate the sound', rather than an inherent property of 'the thing itself'.

Following its tactual production, the musical sound can be transmitted and received as tactile sensations deployed at a distance. Building on Connor's proposition of the 'immaterial corporeality' of sound, electroacoustic composer Simon Waters postulates that sound, or our perception of sound, is 'in some sense tactile-that music and sound-based forms of "communicating" involve "touching at a distance"-indeed at a variety of distances' (2013: 121). This 'touching at a distance' can be construed as the process to 'transduce' the 'essentially tactile qualities' from the performer's end, such as the musician's physio-psychological state, into the 'similar bodies of listeners' without direct physical contact (122). As Waters further explicates, music takes advantage of the dual abilities of sound to be transmitted into a distance and of touch to orient other senses:

Music has always availed itself not only of 'hearing at a distance' … but also equally of 'touching at a distance' and therefore of 'feeling at a distance'. Touch is the sense which orients. We need strategies forre-accessing tactility in a conscious manner in our attempt to counter the disorientation caused by sensory overload … Music, through its appeal to mechanisms which begin with the tactile, might offer a site for the exploration of just such a possibility.(Waters Citation2013: 130)

This citation propounds that our reception of music is not simply an aurally based phenomenon. Hearing itself is enacted as a form of touch-our hearing receptors receive the physical touch generated by tangible sound waves and air pressure. Meanwhile, tactually based mechanisms are placed at centre stage to orientate sensorial interchange and resist sensual overabundance, thus enabling our aesthetic listening of music. When the musical sound is transmitted to our receptor organs, our double reliance on hearing and tactility renders musical effects as convertible into both palpable bodily sensations and ineffable emotive affect beyond the immediacy of the musician's physical touch. The synergistic interaction between touching and hearing affords our exploration of the world through music.

TOUCHING AT THE PERIPHERY: THE PIANO AS AN INSTRUMENT OF TOUCH

The modern pianoFootnote2 is quintessentially a tactually based instrument. Piano playing invigorates extensive tactility beyond manual dexterity. Indisputably, the most elaborate tactility in piano playing culminates in the neurological receptors of the fingertips. For example, the pianist's deployment of touch can be rendered as 'a tool … to mediate between the expressive intentions and the required actions at the point of finger-key contact' (MacRitchie Citation2015: 172). Likewise, the specificity of touch in piano playing can be referred to as 'the intrinsic way the fingers arrive at the piano key surface', or 'the way pianists manipulate the key surfaces of the piano keys with their fingers' (GoeblCitation2017: 1, 9). Although the direct 'finger-key contact' figures prominently in co ntemporary piano scholars' interpretation of tactility, it cannot fully represent the tactile qualities implicated in piano playing.

Physio-anatomical perspectives provide a glimpse into pianistic touch at a pan-physical level. Hinging on the meta tarsal bones, the ball of the foot is actively used to press and release the piano's pedals. The lateral movement of the torso induces gravitational pull of the pianist's performing body, coordinating organic motions and perceptible gestures through intangible forces of touch in the production of quasi choreographic effects. Performance scientists ascribe both manual virtuosity and injuries of professional musicians to hypermobility in their fingers, which are interconnected with the muscular pull in the back, knees and joints to afford greater speed and flexibility (Clark et al. Citation2013: 605). The 'kinematic chain' of 'the upper limbs, from the shoulder, elbow, wrist to the finger joints' enables the pianist to generate a wide range of force variations to 'the surfaces of the piano keys' (GoeblCitation2017: 8). In general, the pianist's versatile employment of touch renders piano playing as performing 'a multi-modal phenomenon including auditory, visual, tactile, and proprioceptive components' concerning all aspects of techniques in piano playing (10). The pianist choreographs various forms of tactility into physio-musical patterns, such as direct key press, the subsequent hammer strike, the depressing of the key and its escapement in the generation of pianistic sound; the distribution of arm weight to manoeuvre the speed of keyboard attack and the dynamic level; the fluctuation of pedals in introducing more shades of sonic texture. These physio-musical patterns cannot be better comprehended by analysing the mechanistic mechanism of the piano and its tactile involvement.

Among all music instruments, the modern piano entails the most elaborate and diverse range of tactility in producing musical sound. The current pianistic mechanism reflects an evolutionary process of tactual contrivance involving increasingly intricate modalities of touch. Notably, the modern piano design wields the tactile mechanisms of both percussion instruments and string instruments. Eac h note on the piano is activated by pressing the key that transmits the kinetic motion from the key lever to the hammer, which is propelled towards colliding, striking and beating the string(s) (Giordano Citation2016: 13). Devised by the instrument maker Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731), this mechanism transduces the pianist's manual touch into mechanical percussive force and is designated as the 'piano action' that brings the instrument to its modernity.Footnote3

Nineteenth-century anecdotes present the tactile accomplishments of professional pianists as capable of reconstituting the audience's perceptive modes of feeling. For instance, the virtuosic recitals by Franz Liszt (1811-86) exemplify how his pianistic touch could sublimate the audience's normative concert experience into psychic and paranormal illusions. The Romantic virtuoso anima ted the soundboard of the piano while enkindling visceral and soma tic reactions from his female admirers. Notably, Liszt's pianistic touch triggered a hyper-sensation that dissolved the frontier of ordinary sensual perceptions. Upon witnessing Liszt's virtuosic touch, it is suggested that his female fans fainted at his public concert as if struck by the immanent feel of God (Gooley Citation2004: 212-14). The blurring of Liszt's playing and the transcendental experience of the 'feel of God' indicates the deceptive nature of piano playing: it draws on the pianist's acutely proprioceptive sense of the body, a quasi-automaton technical collaboration with the pianoFootnote4 and the intangible tactility of musical sound to produce a holistic sensual or hyper-sensual experience. This divine 'feel' can be demystified as the performa tives of touch at play in their most stripped-down tactual expressions: Liszt touches the piano, the instrument responds mechanically and arouses waves of pressure to touch the audience in sound, while the corporeal gestures and musical motions are encoded in the affective touch to elicit emotional reactions.

Admittedly, piano playing entails aspects of ineffable tactility that cannot be measured scientifically. Some sensual-aesthetic qualities of music elude the parameters of modern biotechnology and cannot be analysed in quantifiable velocity, force, tempo, volume, dimension and weight. Nonetheless, the non-scientific possibilities of pianistic touch stimulate infinite creativity in the reception of piano performance in the artistic context. Since piano playing flourished in European society in the late eighteenth century (Trillini Citation2008: 63), the aesthetic attributes of pianistic touch have attracted intimate attention from performing pianists, piano composers and educators. For instance, the great female virtuoso, Clara Schumann (1819-96), received pianistic training under the tuition of her own pianist father, Frederic Wieck, who foregrounded the importance of touch in his pedagogy. In his 1830 letter, Wieck writes, 'I always combine lessons in the practical study of simple chords by means of which I impart a beautiful and correct touch' (Litzmann Citation2013: 20). Perhaps partially due to her father's tutelage, Clara enjoyed accolades from the early stage of her virtuosic career for her refined, tactile artistry. After a private concert given at the age of 12, Clara's pianism was eulogized for the painterly quality of her pianistic touch: 'this has never been combined, as in her, with such broad execution, the right accentuation, and perfect clearness united with the finest lights and shades of touch' (32-3).

Tactile command was equally important for the virtuosic Liszt and Schumann as it was for the Romantic pianist-poet, Frédéric Chopin (1810-49), for whom the art of performing the pianistic touch equated to caressing the keyboard. As interpreted by his students, Chopin urged his disciples to caress the touch in his aphorism: 'caresses the keys, but never pushes, hits or knocks them' ('Streichelt die Tasten, aber stogt, schlagt, klopft sieniemals'); this Chopinesque artistry of touch deviated from the prevailing German school that was accustomed to 'hitting the piano' ('ein Klavier eindrischt') (Herrgott Citation2008: 145, my translation). The non-existence of recording technology in the nineteenth century makes it impossible to reproduce the sensual-aesthetic practice of Chopin's playing in contemporary performance settings. Nonetheless, Chopin's discourse on touch as 'caressing the keyboard' has stimulated subsequent physiologists, scientists and musical writers to further explore the kinaesthetics inspired by his oeuvre. As will be analysed in the next section, the pianistic touch, motivated by the manifold tactile possibilities in Chopin's Nocturnes, can inflect musical timbre and rhythm to transform ordinary bodily sensations into the sensually fantastic.

HEURISTIC S IN LITER A TURE : T WO NOVELISTIC TEXTS ON TH E PIANISTIC TOUCH

The previous two sections investigate both direct physical touch and indirect musical tactility involved in the production and reception of piano performance in the musical context. Beyond real-life settings, two works of literature provide useful heuristics to illuminate what it means by touching and being touched pianistically in extended performance practices. Thomas Mann's musical novella, 'Tristan' (2009 [1903]), is themed around the performative resources of piano playing deployed by the tubercular pianistprotagonist Gabriele Klöterjahn. Her scintillating rendition of Chopin's Nocturnes and pianistic adaptation of Wagner's Tristan und Isold e transform her insipid everyday experience within a clinical, bourgeois society into a sensually prosperous rea lm. E. M. Forster's piano novel, A Room with a View (2012 [1908]), presents the quasi-virtuosic piano playing of the amateur Lucy Honey church in parallel with her coming of-age struggles. Lucy's piano performance evokes the eroticism of pianistic touch and its subversive position in the late nineteenth century bourgeois culture. The selected piano playing scenes from the two novelis tic tex ts serve as a captivating means of accessing the sensory aesthe tic continuum at play in the tactile production of pia no performance. Moreover, the fic tional presentations of piano playing begin to provide us with a language to perform what prior categories of senses cannot unveil in the pianistic touch beyond the increasingly standardized and mass-produced middle-class concert culture.

Tristan explores the artistry of pianistic touch through which physical-aesthetic sensations emerge, develop and transmute performative ly in words. In one scene, Gabriele Klöterjahn resusc itates he r tactile memories of Frédéric Chopin's Nocturnes in her alluringly displayed sense of touch. Her ve rsatile rendering of pianistic touch is presented as a distinct tactually produced phenomenon that culminates in physic-aesthe tic effects:

She played the Nocturne in £-flat Major, op.9, no. 2. If it was true that she had forgotten some of what she once knew, her performing skills back then must have been truly first-class. It was only a mediocre piano, but after the first few chords she knew how to handle it with control and taste.She displayed a tensely attuned sensitivity to timbre and a joyful command of rhythm that bordered on the fantastic. Her touch was both sure and delicate. Under her hands, the melody yielded every last bit of sweetness, and her embellishments nestled around its main lines with restrained grace.(Mann Citation2009 (1903]: 36)

As the quote demonstrates, touch functions as the performative operative that brings the immateria l sensuality of pianistic sound into existence. Gabriele's touch, both 'sure' and 'delicate', is doubly c harac terized by her alternating modes of touching the keyboard; tangible, tactile qualities such as firmness, solidity, tenderness and softness figure prominently in her piano playing. Gabriele's kinaesthetic exploration after several chords, albeit on a run-of-the-mill instrument, endows her performance with composure and aesthetic discernment that transcend the ordinariness of physically induced sensations, thus 'bordering on the fantastic' (Mann Citation2009 [1903): 36). Her 'tensely attuned sensitivity to timbre' is deeply lodged in her tactual censorship of pianistic tone colour, while her 'joyful command of rhythm' indicates her tac tile manoeuvre of corporeal signs a nd ac tions in orga nic me trica l motions. Following the directives of touch, the ornamenta l passages supplementing the mellifluous main melodies generate aural perceptiveness of 'sweetness' and 'grace', which metaphorically touch the performing pianist and her audience, the silently sitting Mr Spinell, in its shared affective tone.

In Mann's text, Gabriele's exemplary pianism is not de termined by her retention of all the written notes in memory, but by her development of pianistic touch as a progressive and persistent form of remembering music. During her performance, the printed music nota tions aid her conceptual grasp of the piece ('She took a seat on the stool, adjusted the ca ndelabras a nd flipped through the sheet music') (ibid.). However, the sight of the music alone cannot inform the virtuosic manner in which Gabriele plays the piano. Instead, Gabriele stands out as a musical artist with her embodied tactile command. After Gabriele abandoned piano playing for a prolonged duration after her marriage, her consolidated skills to perform Chopin's Nocturnes attest to her ability to draw on the aesthetic sensory practices in the past and her astute use of pianistic touch to reinstate its performative force in the present: 'she had forgotten some of what she once knew … but after the first few chords, she knew how to handle it with control and taste' (ibid.). Established through time, the processual tactile interactions between the pianist and the piano empower Gabriele's musical expressivity in its physical and affective embodiments.

An analysis of the tactual memory of piano playing illuminates the processual development of tactile relationships shared by the pianist, the pianistic sound and the instrument. When physical touch departs from the pianist's body, the mechanical instrument releases biological energy by emitting sound. Meanwhile, the instrument resists the surface tension produced by physical contact and requires the pianist's repetitive touch, enabling the storage of automated motor functions in the pianist's muscle memories. As deposited memory, the pianistic touch concomitantly dwells in the pianist's biotic organism, while retaining its flexibility to be disrupted from corporeal presence. When unused, the acquired tactual skills morph into the physically indeterminable realm as the pianist's physio-aesthetic memories. When applied to the instrument, its readiness to be revived in and as music performance indicates the tenacious, sensual and affective forces ingrained in the pianistic touch. Although the pianistic touch is not always explicitly manifested in a physical form, it can be conceived as the nexus between physiology and affect that co-considers how bodily gestures and mechanical applications resolve into tone, which tinctures atmosphere and creates aesthetic impressions in our somatosensory fabric.

A Room with a View probes the profound interlinking between pianistic touch and its subversive positioning in middle-class amateur music culture. In the nineteenth century, bourgeois young ladies deployed amateur piano playing to provoke the male suitor's gaze, a ubiquitous sexual-cultural phenomenon examined at length by scholars in Victorian female pianism (Fillion Citation2010; Trillini Citation2008; Stankiewicz Citation2002; Vorachek Citation2000). Although touch does not feature prominently in the scholastic discussions, existing narrative discourses point to its suggestive presence. For example, it is indicated that 'figuring middle class female sexual de sire in the piano-outside the body but contained within the domestic realm' enabled unmarried virgins to 'arouse and manipulate their own sexuality, to seduce without contact' (Voracheck 2000: 37). Forster's piano novel builds on the erotic implications of piano playing externalized by tactually oriented actions. Foregrounding pianistic touch, Forster's depiction of female pianism can be deemed as the means to 'arouse' and 'manipulate' sexuality both within and beyond the bourgeois household. During her touristic sojourn at Pensione Bertolini in Florence, Lucy Honeychurch, the amateur pianist in her maidenhood, discovers her libidinous selfhood through the self-exploratory pianistic touch. 'Like every true performer, she was intoxicated by the mere feel of the notes: they were fingers caressing her own; and by touch, not by sound alone, did she come to her desire' (Forster Citation2012 [1908]: 31). She does not just touch the piano but allows the piano to touch back; the 'mere feel of the notes' is incorporated into audible musical sound to produce aphrodisiac effects.

Lucy's pianistic exploration oftouch at the Italian hotel induces a throwback to a live performance scene at her hometown. Through the perspective of the clergyman Mr Beebe, the triumphant solidity of Lucy's pianistic touch is seen to interrogate, rather than gratify, the male spectator's expectations:

Among the promised items was 'Miss Honeychurch. Piano. Beethoven', and Mr Beebe was wondering whether it would be Adelaide or the march of The Ruins of Athens,when his composure was disturbed by the opening bars of Opus 111. He was in suspense all through the introduction, for not until the pace quickens does one know what the performer intends. With the roar of the opening theme he knew that things were going extraordinarily; in the chords that herald the conclusion he heard the hammer-strokes of victory. He was glad that she only played the first movement, for he could have paid no attention to the winding intricacies of the measure of ninesixteen. The audience clapped, no less respectful. It was Mr Beebe who started the stamping; it was all that one could do. (Forster Citation2012 [1908]: 31).

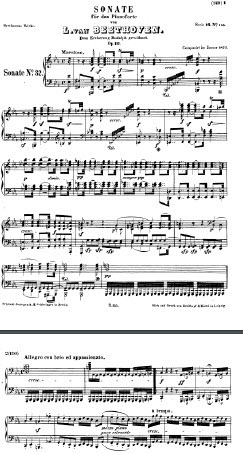

In Lucy's rendition of Beethoven's last Piano Sonata, her pianistic touch reverberates with the 'hanuner strokes of victory' to manipulate the patronizing gaze of the typically sanctimonious male audience. The preludial bars, comprising the dynamically unsettling chords and rhythmically intense ascending arpeggios (Ex. 1), defies Mr Beebe's wish for pleasant and unsophisticated tunes. During the short course of the introductory passage (Ex.1, nun.1-19), Lucy orchestrates the speed of her motion to usher in the fortissimo roaring theme (Ex.1, nun. 19-20), transforming the clergyman's fretful mood into extraordinary impressions as a result. Manifested in the tactually produced effects of volume, rhythm and tempo, Lucy's kinaesthetic hyper-sensitivity resuscitates the distinct touch oflate Beethovenian hammer-strokes. While the term 'hanuner-strokes' suggests the 'action' of hanuners hitting strings in the modern piano as broached in the previous section, it can well be construed as Lucy's prosthetic tactility pulsating at a distance. Her haptic-musical message is triumphantly delivered to her audiences from mixed socio-economic backgrounds. They unanimously reciprocate Lucy's performance by animating their corporeal gestures, including the clasps of hands and stamps of the foot, complementing the tactile exchange.

Through Mr Beebe's voyeuristic perspective, Lucy's two piano-playing scenes at the Italian hotel and the parish concert can be juxtaposed to suggest the promise of unprecedented excitement. The blurring of her erotic touch and victorious strokes is conducive to a tactually oriented pianism that subverts the sexual musical culture of her time. The bourgeois 'piano girls' of the nineteenth century administer to their sexual desire on the pianistic platform, but they do so in a clandestine manner within a domestic circumference. The act of touching the keyboard diverts their latent sexuality into a socially respectable form of performance. Once contemporaries, Lucy's pianistic touch externalizes and displays her carnal desire in a semi-public realm and even coordinates a sense of sensual victory and supremacy over the subjugating male gaze. While printed music notations can only offer the 'scaffolding for a dream',Footnote5 it is the tactile execution in a real-time performance process that instates the pianist into 'a more solid world when she opened the piano' (Fillion Citation2010: 122; Forster Citation2012: 30). Lucy's transgressive touch mobilizes her infiltration into the 'kingdom of music' and 'shoots into the empyrean without effort' as soon as she begins to play (Forster Citation2012 [1908]: 30). The physical and affective implications of her pianistic touch ascertain her existence beyond the physio-ethicallimits of upper middle-class life in Edwardian English society. heard by potential male suitors, their piano playing mutates into a social tool to assuage masculine desire, entice their future husbands into lascivious listening, intimate their readiness for marriage and ritualize a 'rite of passage into decently socialised womanhood' (Fillion Citation2010: 57). Unlike her piano-playing predecessors and

CONCLUSION

In the production and reception of piano performance, the multivariant senses oftouch illuminate haptic communications beyond the relationship of 'contact' between the pianist and the instrument. The contingent interactions between sound and tactility testify to the blurring of physical and affective touch as a distinct mode of performance. The pianist's touch mobilizes tactual-affective exchange, feedback and adjustment with the piano, venue, audience and atmosphere. As a pre-eminent instrument of touch, the modern piano empowers pianistic sound to be produced, enriched and qualified by the materiality of mechano-physiological touch. Our aesthetic 'listening' to piano music relies on the co-opera tionality of hearing, touching and feeling at a range of distance. The two literary works discussed above provide us with a fruitful tool to access the sensory-aesthetic continuum at play in piano performance and to reappraise the considerable extent to which our sensory experience of music is multi-modal and culturally inflected. Overall, motivated by the evocations of pianistic touch in various contexts, the subject of tactile performance and performativity provides productive perspectives for re-constructing what prior perceptions of sensory difference could not consider in the sensual-aesthetic practice of piano playing.

Notes

1 According to the American Psychological Association’s (APA’s) online Dictionary of Psychology (2020), affective tone refers to the ‘mood or feeling associated with a particular experience or stimulus’.

2 Modern piano design follows a general pattern: it consists of eighty-eight keys covering a 7'h octave range, with the lowest bass notes produced by a single string, mid-range notes by two strings and higher notes by three strings. The piano has evolved substantially from its oldest prototype, invented by the Italian instrument maker Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731) three centuries ago, to its proto-modern form in the late nineteenth century. The development of the piano has reached its current state and has remained predominantly unchanged since about 150 years ago.

3 Prior to this invention, the piano's instrumental predecessor, the harpsichord, relies on a different mechanism that plucks rather than hits the strings-the harpsichordist's keypress automates but cannot variegate the way the string is plucked. In contrast, the percussive mechanism in the modern piano allows a dynamic tactile-sonic intra-action and embraces contingency in the sound-making process, such as changing velocity in the piano keypress to determine the volume of pianistic sound from pianissimo to fortissimo; the tensile exchange between the hammer and the stricken strings for variable harmonicity and mellowness (Giordano Citation2016: 16).

4 Cvejic (Citation2016: 131) states that 'automata were self-powered machines, which , when appropriately wound-up by a human operator, mimicked living beings, animal or human; and they were very much en vogue in late-18"'-and early-19"'-century Europe, from Vaucanson's "duck" and "flautist" to Maelzel's "chess-player", which achieved glohal fame'. Considering how industrialization changed the landscape of nineteenth-century Europe, it is not surprising that the automaton foregrounds the critical reception of piano performance of that time (Cvejic Citation2016: 130).

5 The 'scaffolding for a dream' are the terms Forster uses to describe his impression of Beethoven's Sonata Op. 109 in his fragmented wartime manuscript, which, albeit incomplete annotates many of the composer's Piano Sonatas. This manuscript is first published in Fillion's Citation2010 monograph on Forster and music.

REFERENCES

- American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology online (2020) https://dictiona ry.apa.org/affective-tone, accessed 17 December 2021.

- Beethoven, Ludwig van (1862) 'Piano Sonata inc minor, Op.111', wdwigvanBeethovens Werke, Serie 16: Sonatenfii.r das Piano forte (Ludwig van Beethoven's Works, Series 16: Sonatas for the Pianoforte), Nr.155, Leipzig: Breitkopfund Hartel.

- Clark, Terry, Holmes, Patricia, Feeley, Gemma and Redding, Emma (2013) 'Pointing to perfOrmance ability:Examining hypermobility and propri oception in musicians', Proceedint;; of the International Sym posium on Performance Science 2013, Brussels: the European Association of Conservatoires (AEC), pp. 605-10.

- Connor, Steven (2001) 'Edison 's teeth:Touching hea ring', www.stevenconnor.cornfedsteeth.html, accessed 28 July 2021.

- Cook, Nicholas (2021) Music: A very short introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cvejic, Zarko (2016) The Virtuoso as Subject: The reception of instrumental virtuosity, c.1815-c.1850, Newcastle-uponTyne: Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

- Davies, Stephen (2003) Themes in the Philosophy of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fillion, Michelle (2010) Difficult Rhythm: Music and the word in E.M Forster, Urbana, IL, Chicago, IL and Springfield , IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Forster, Edward Morgan (2012 [1908)) A Room with a View, London: Penguin English Library.

- Giordano, Nicholas (2016) 'The invention and evolution of the piano', Acoustics Today 12(1): 12-19.

- Goebl, Werner (2017) 'Movement and touch in piano performance', in Bertram Müller, Sebastian I. Wolf, Gert-Peter Brüggemann, Zhigang Deng, Andrew S. Mcintosh, Freeman Miller and W. Scott Selbie (eds) Handbook of Human Motion, Berlin: Springer, pp. 1-18.

- Gooley, Dana (2004) The Virtuoso liszt, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hayward, Vincent (2018) A. brief overview ofthe human somatosensory system', in Stefano Papetti and Charalampos Saitis (eds) Musical Haptics, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 29-48.

- Herrgott, Gerhard (2008) 'The art of touch:Elisabeth Cal and and the physio-aesthetics of piano playing', Berich te zur Wissenschafts-geschichte (History of Science and Humani ties) 31(2): 144-59. doi: 10.1002/bewi.200801310

- Litzmann, Berthold (2013) Clara Schumann: An artist's life, based on material found in diaries and letters, vol.1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- MacRitchie, Jennifer (2015) 'The art and science behind piano touch:A review connecting multi-disciplina ry literature',Musicae Scientiae 19(2):171-90. doi: 10.1177/1029864915572813

- Mann, Thomas (2009 [1903]) 'Tristan', in Death in Venice and Other Stories, trans. Jefferson S. Chase, New York, NY: Signet Classics, pp. 11-54.

- Stankiewicz, Mary Ann (2002) 'Middle class desire: Orna ment, industry, and emulation in 19th-century art education', Studies in Art Education 43(4):324-38. doi: 10.2307/1320981

- Trillini, Regula Hohl (2008) The Gaze of the Listener: English representations of domestic music-making, Amsterdam: Brill.

- Vorachek, Laura (2000) '"The instrument ofthe century": The piano as an icon of female sexuality in the nineteenth century', George Eliot-George Henry Lewes Studies 38/39: 26-43.

- Waters, Simon (2013) 'Touching at a distance: Resistance, tactility, proxemics and the development of a hybrid virtual/ physical performance system', Contemporar y Music Review 32(2):119-34. doi: 10.1080/07494467.2013.775818