ABSTRACT

This article reports on a qualitative study on the issues experienced teachers may encounter in everyday teaching practice. Some issues may possibly originate at the beginning of a career and continue to be a struggle during their career. Data were collected among 20 mid- and late career teachers from eight secondary schools. The results showed that at the current moment in their career, respondents of this study particularly recognised three issues: teacher–parent interaction, teaching versus other tasks and private life versus work. Teachers seldom talk about their issues, but more often than not they try to find a solution themselves or put up with the situation.

1. Introduction

Teachers experience ‘ups and downs’ throughout their career due to changes in their work or in their life’s context (Day & Gu, Citation2010). Being a teacher can be demanding and stressful, both at the beginning, as well as in the later phases of their career (Guarino, Santibañez, & Daley, Citation2006; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2011; Veldman, Van Tartwijk, Brekelmans, & Wubbels, Citation2013). Some teachers stay positive, committed and motivated, whereas others are occupied with troublesome issues or become disenchanted (Hargreaves, Citation2005; Huberman, Citation1993).

Drawing upon previous research, roughly three main phases of a teaching career can be distinguished (cf. Day, Sammons, Stobart, Kington, & Gu, Citation2007; Hargreaves, Citation2005; Huberman, Citation1993). In all three phases, the professional identity of the teachers plays a crucial role. First, an early career phase is characterised by survival, by a growth of expertise and the development of a positive professional identity (Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009; Meijer, Citation2011). Second, the mid-career phase is characterised by stability in both expertise and professional identity (Day et al., Citation2007). Third, during the later career phase, a decrease in commitment and motivation may occur and maintaining a positive professional identity might become a challenge (cf. Beijaard, Citation1995).

Many studies have focused on developing a realistic professional identity during the first career phase, especially for pre-service and beginning teachers and the educational challenges or identity tensions that they can face (cf. Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009). Studies on mid and later career phases have had a tendency to focus on attrition (Day & Gu, Citation2009; Rolls & Plauborg, Citation2009), job satisfaction, work stress and burnout (Veldman et al., Citation2013), together with feelings of disillusionment and frustration (Day & Gu, Citation2009; Huberman, Citation1993).

Although some issues of experienced teachers may be specifically related to their career phase or to specific contexts, more generic issues may have possibly appeared already at the beginning of their career and have continued to be a struggle during their ongoing career (Gaikhorst, Beishuizen, Korstens, & Volman, 2014). Pillen, Beijaard, and Den Brok (Citation2013) found that in their first year of teaching, beginning teachers succeeded in coping with many identity issues. Following on from Admiraal, Korthagen, and Wubbels (Citation2000), coping was defined as making an effort to manage a troubled personal–environmental relationship. Some identity issues have remained to be a struggle and other identity issues may have reappeared (Pillen et al., Citation2013). Yet little is known about the continuity or the discontinuity of the appearance of these identity issues that teachers have experienced during their careers.

In the current ‘age of measurement’(Biesta, Citation2009), with an emphasis on testing the ‘accountability and the administrative aspects of teaching’ (McIntyre, Citation2010, p. 597), maintaining a positive professional identity can become a challenge for many (experienced) teachers, since they are more than ever monitored and held accountable for the learning outcomes of their students (Biesta, Citation2009; Duncan, Citation2013). The continuous urge for teachers’ quality and professionalism leads in some cases to a reduced teacher autonomy and de-professionalism (Beck, Citation2008; Johnston, Citation2015).

Based on the above, the aim of this study was to gain an insight into how experienced teachers have coped with the identity issues that beginning teachers encounter. The research questions in this study were: ‘Which identity issues, previously mentioned by beginning teachers, disappear, remain, or re-appear, during the career of experienced teachers and how do experienced teachers cope with these situations?’

2. Theoretical frameworks

2.1. Professional identities during their career

Although definitions vary, researchers generally agree that a teacher’s professional identity is a dynamic concept that is influenced by personal aspects (such as personal histories, norms and values, personal beliefs) as well as by professional aspects (such as accepted theories of teaching and learning, a school’s expectations and professional standards) (cf. Alsup, Citation2006; Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009; Beijaard, Meijer, & Verloop, Citation2004). In other words, to cite Beijaard and Meijer (Citation2017): ‘who one is as a person is strongly interwoven with how one works as a professional’ (p.177). A positive professional identity is important for teachers, since professional identity is related to their well-being and their commitment and to functioning in the classroom (Beck & Kosnik, Citation2014; Burke & Stets, Citation2009; Canrinus, Helms-Lorenz, Beijaard, Buitink, & Hofman, Citation2011; Day & Gu, Citation2010). Previous studies have described how beginning teachers can develop a positive professional identity by reflecting upon ‘struggling’ questions, such as ‘what kind of a teacher am I?’ and ‘what kind of a teacher do I want to become?’ (Akkerman & Meijer, Citation2011), by overcoming emotions (O’Connor, Citation2008), by experiencing crises (Meijer, Citation2011), or by coping with issues, which are called identity tensions, in the early years of their career (Hong, Citation2010; Pillen et al. (Citation2013). For instance, Citation2013; have identified—based upon a literature study and semi-structured interviews—a list of thirteen identity tensions that novice teachers encounter—regardless of the school’s (ethnic) background and culture—while developing their professional identities. Based upon their results that some identity tensions have remained during the first years of a teaching career and that they have seriously affected teachers’ functioning, Pillen et al. (Citation2013) have argued for research on mid and late career teachers’ identity issues. The intensity of most identity tensions has been likely to decrease during the later career phases of a teacher, but some identity tensions may have remained to be troublesome, even for experienced teachers.

2.2. The storyline research tool

In order to study the issues that teachers have faced during their careers, the ‘storyline research tool’ has been previously used (Beijaard, Van Driel, & Verloop, Citation1999; Bullough, Citation2008; Orland, Citation2000). The storyline research tool, or storyline methodology, is a form of narrative research, used to interpret the experiences of the participants (cf. Orland, Citation2000). By asking the teachers to draw a graph (a so-called storyline), they express themselves concerning a topic over time (e.g. job satisfaction). Subsequently, the participants are invited to explain their graph (e.g. peaks and depths) by elaborating on the topic.

By drawing and explaining a storyline, the participants become actively involved in recalling and reflecting upon the issue in question (Orland, Citation2000). Being a visual, nonverbal research tool, the storyline procedure helps a verbal reflection, in order to gain a deeper understanding into the complex dynamics of teachers’ identity issues (Orland, Citation2000). Previous research on later career teachers’ stories regarding a professional identity has shown promising results by using the storyline method (Beijaard, Citation1995; Bullough, Citation2008). Drawing a storyline is important in order to recall ‘episodic memories of specific incidents’ (Orland, Citation2000; p 207), meaning that in our study, there was a period of identity issues during their career. Previous research recommends storylines to be drawn from present to start, because ‘…knowledge about the aspect of teaching in question is activated from which lines can be drawn towards the past, a reverse procedure appears to be more difficult ‘(Beijaard et al., Citation1999, p. 50). A major benefit of the storyline approach is that ‘the participants evaluate experiences and events themselves, ‘which appear to be difficult tasks for researchers when using [other forms of] narrative research’ (Melville & Pilot, Citation2014, p. 356). Other advantages are that storylines can elicit teachers’ development throughout their career and that the duration of certain events can be visualised (Beijaard et al., Citation1999). Next to the valued use of the storyline method for research, the storyline approach has also been shown to be a useful research tool for reflection upon teachers’ learning (Melville & Pilot, Citation2014) and for student teachers during their teaching education (Meijer, De Graaf, & Meirink, Citation2011; Orland, Citation2000). The disadvantages of the storyline method are that not all teachers are able to exactly locate an event in time and the explanations from teachers can be broad and superficial, together with lacking specific situations or content (Beijaard et al., Citation1999). Next to that, there is a risk of teachers generalising ‘particular years or events by averaging the highs and the lows over a period of time,’ resulting in a ‘flat’ storyline (Melville & Pilot, Citation2014; p. 356; cf. Gergen, Citation1988).

In this study, the storyline research tool was the essence of a reflective questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of thirteen issues that are experienced by teachers in the beginnings of their career (cf. Pillen et al., Citation2013). The participants were asked to read each issue and then express themselves concerning this particular issue by drawing a graph (from the present to the past) and to explain their graph in writing.

2.3. Research questions

The research questions were aimed at studying how experienced teachers cope with everyday (identity related) issues that seem to be related to maintaining their positive professional identities. The main research questions were: ‘Which identity issues, previously mentioned by novice teachers, disappear, remain, or re-appear, during the career of experienced teachers and how do experienced teachers cope with these situations?’

Sub questions

Which identity issues do experienced teachers experience:

(a) At the current moment in their career?

(b) At the beginning of their career (in retrospect)?

(c) During the time in between the beginning of their career and at the current moment (in retrospect)?

How do experienced teachers cope with identity issues which they are experiencing in the present moment?

How do the identity issues influence their teaching according to the teachers themselves?

3. Method

In this section, we will elaborate on the research design (3.1), the development of the research tool (3.2), data collection (3.3) and the participants of this study (3.4).

3.1. Research design

In order to gain an insight into the identity issues of a group of experienced teachers, a qualitative research design was chosen because of: (1) the novel nature of this study, and (2) the interest in teachers’ perceptions and meaning making of the identity issues during their career (Faber, Citation2012). In addition, a qualitative design allowed for more sensitivity and offered the opportunity for the participants to explain and express themselves (cf. Boeije, Citation2010). Following the narrative methodology, personal experiences are interpreted and made personally meaningful (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006). Often used tools or instruments to collect data within a narrative research design are of qualitative nature and can be text in oral, written, or visual form (Riessman, Citation2008) such as chronicles, reports, open-ended questionnaires, story-line methodology and video-recordings.

According to Clandinin and Connelly (Citation2000), interpreting experiences can be characterised as relational (experiences are both personal and social), temporal (experiences stem from other experiences and lead to new ones), and situational (experiences take place in situations). In the present study, the storyline method the experienced teachers gave meaning to the situations that they had encountered during their career by drawing and explaining a storyline themselves, which was one of the major benefits of using the storyline method (see 2.2). In contrast to common storyline methods, in which the teachers draw storylines of relevant experiences and unspecified events (cf. Beijaard et al., Citation1999), we provided situational descriptions for the teachers to draw storylines about (cf. Appendix A). After drawing their storylines, the teachers were asked in the questionnaire to explain and interpret their graphs. The data was analysed on a group level.

3.2. Development of the research tool

In order to answer the research questions, the questionnaire was developed and was based upon the validated and reliable Identity Tension Questionnaire for beginning teachers (Pillen et al., Citation2013). The questionnaire consisted of thirteen identity issues (situational descriptions) with 13 different themes; e.g., wanting to care vs. being tough to students, being idealistic vs. being realistic, private life vs. work (). For the present study, the Identity Tension Questionnaire was adapted for teachers in other career phases. One situational description of an issue about teacher’s education was omitted since it was not applicable for teachers who had completed teacher education some years ago. One issue about the teacher–parent interactions was added based on a group discussion with experienced teachers (see ). Next to that, four situational descriptions of the Identity Tension Questionnaire were copied (no changes made), three situational descriptions were adjusted (changes on a sentence level, e.g. reference to the context of internships, practice schools or teacher education) and five were slightly adapted (small changes, e.g. pre-university vs. pre-vocational students, names were changed to increase gender and cultural diversity among the situations).

Table 1. List* of the identity issues in the questionnaire (based upon Pillen et al., Citation2013)

In addition, in the present study, the storyline method was added to the Identity Tension Questionnaire in order to construct a reflective questionnaire for mid-to-late career teachers. A group discussion with experienced teachers was organised in order to check for the face validity of the newly developed questionnaire. All in all, this resulted in an adapted final questionnaire which consisted of two parts: one part was with a few questions concerning the demographical background of the participants and one part was with the 13 issues (situational descriptions). For each issue, the respondents were asked to draw a graph and to elaborate on the graph. This was followed by some questions about their coping strategies and about the influences of the identity issues on the participants’ teaching. (cf., Appendix A for an overview of the situational descriptions and Appendix B for the questions asked about each situational description).

Next to the questions on demographics, for each identity issue, the participants were asked to draw a graph, in order to indicate to what extent they found the identity issue recognisable during the various phases of their own career. The participants were asked to start their graph by describing the current moment in their career (for example, whether they recognised the issue at the present moment; i.e. in May 2014) and then to draw a line backwards in time. On the x-axis, the teachers’ career was depicted as a time line. The chunks on the x-axis were referred to as the calendar years (e.g. 1975–1980), instead of the number of years of teaching experience (e.g. 35–40 years). By doing so, the participants were stimulated to think more precisely about the issue in question and to draw the graph in more detail. The y-axis expressed a four-point rating scale (not at all—to very recognisable for me at this moment).

By employing this method, the teachers’ experiences in the present moment were activated as a starting point, followed by moments in the past, which therefore, gave the opportunity to easily recall the present and at the same time, the opportunity to reflect on the past (cf. Beijaard et al., Citation1999).

Four kinds of graphs could be distinguished: Decreasing, Increasing, Varying, and Unchanging. ‘Decreasing’ referred to a decline in the level of recognition of a specific identity issue for a participant. In a similar vein, ‘Increasing’ referred to a rise in the level of recognition and for ‘Unchanging,’ the level of recognition was stable. ‘Varying’ was applied when a graph showed multiple directions, for instance, first increasing and afterwards decreasing. After the drawing of the graph, both multiple choice and open-ended questions concerning the coping strategies in the present moment were asked for each identity issue. The answers to the multiple choice question on coping strategies (‘how did you cope with this identity issue?’) were categorised by using possible answer categories of: (a) looked for a solution myself, (b) disappeared without my own initiative, (c) talked to somebody and (d) accepted the issue (cf. Pillen et al. (Citation2013)). In case the participants selected the answer ‘talked to somebody,’ they were asked to indicate with whom they had talked to, using the following possible answer categories: (a) with a coach/mentor at the school; (b) with a novice colleague; (c) with an experienced colleague; (d) with someone from their former teacher training institute; (e) with family or friends; (f) with someone else. After this question, there was an opportunity for the participants to elaborate on their selected answer. In addition, an open-ended question was asked on how the identity issues had influenced the teachers’ work (‘in what way did this situation influence your work as a teacher?’). The average time for teachers to complete the questionnaire was 1–1.5 h.

3.3. Participants

A group of eight experienced secondary school teachers from eight different schools in the southern part of the Netherlands were asked to complete the questionnaire (pencil and paper) and in addition, they were to invite two experienced teachers from their school to complete the questionnaire. The teachers’ participation in this research project was voluntarily and anonymous. Results of this research were not communicated to the schools of the participating teachers and teachers were at all times able to withdraw themselves from this study. The authors of this study had no formal relationship with the participating teachers or schools. The first two authors were at the time of this study working as researchers and teacher educators, the third author was working both as a researcher and a teacher (at a school where no other teachers participated in this study). All of the schools had students with an average socio-economic background and the percentages of students with a non-Dutch background were between 5 and 20 per cent. In all, 20 questionnaires were collected. The 20 participants were experienced secondary school teachers with different ages (M = 52. 9 years; SD 9.21 years), years of experience (M = 25.5 years; SD 10.4 years) and teaching different school subjects (see ). All of the participants taught students between the ages of 12 and 18 years old.

Table 2. Overview of the participants (n = 20 mid- and late career teachers)

4. Analysis

In this section, the process of data analysis is described concerning the start and the current moment of teachers’ careers (4.1), the time in between start and current moment (4.2), teachers’ coping strategies with the identity issues (4.3) and the influence the issues had on teachers’ functioning as a teacher (4.4).

The first sub-question was: ‘Which identity issues do experienced teachers experience?’ In order to answer this first sub-question, we analysed whether the participants themselves recognised the identity issues: (a) at the current phase of their career, and (b) retrospectively, looking at the start of their career. In addition, we analysed whether the participants themselves recognised the identity issues: (c) during the time in between the beginning of their career and the current phase in their career.

4.1. At the start and at the current moment of their careers

For each of the 13 identity issues in the questionnaire, the recognisability of the identity issue for a participant at the starting point (on the right-hand side of the graph) and at the endpoint (the current moment in their career, the left-hand side of the graph) were analysed using frequency analyses. In order to do so, for each identity issue, we identified the frequencies for all of the levels of recognisability (i.e. how many respondents selected a certain level of recognisability for a specific identity issue) at the starting point of their graphs. The level of recognisability with the highest frequency for a specific identity issue was used to characterise a specific identity issue. The same procedure was followed for the endpoint of their graphs. For instance, the identity issue of ‘Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough’ was very recognisable at the beginning of their career for 15 of the 19 participants. Therefore, this identity issue was coded as ‘very recognisable.’

4.2. In-between the start and the current moment of their careers

The recognisability during the time in between the start of their careers and the current moment of their careers was analysed by looking at the direction of the graphs (unchanging, decreasing, increasing, varying) for each identity issue. In order to compare the identity issues for all of the teachers as one group, the individual graphs of the participants for one specific identity issue were summarised into one code and they were then based upon frequency analyses of the directions of the graphs (cf. ).

4.3. Coping with identity issues at the present moment

In order to answer our second sub-research question on how the participants coped with their identity issues, the frequencies of all of the answers were calculated for each identity issue per the answer category. In order to compare their identity issues, the answers for all of the participants that considered the coping of a specific identity issue were summarised upon the basis of the highest frequency of one of the categories. For instance, if most of the participants coped with the identity issue of ‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions’ by talking to somebody about it (when compared to the other answer categories), then the coping of this identity issue was coded as ‘talked to somebody.’

4.4. Identity issues that influenced their teaching

To answer our third sub-research question on whether and how the experienced issues had affected the teaching of the participants, we coded the answers of the participants for each identity issue by using two codes: ‘influence’ and ‘no influence.’ Next, for the participants who did experience the influence of an identity issue on their teaching, we categorised the answers into a positive or a negative influence. In a following step, we analysed the content of their answers for the positive and negative influences in more detail, in order to identify the precise aspect that was influenced by the identity issue.

In order to calculate the inter-rater reliability, 30% of the data was analysed by a second independent researcher. The inter-rater reliability was found to be sufficient on the codes of an influence/no influence (93%) and on the codes of a positive/negative influence. In addition, an inter-rater reliability was found on the content of the influence (88%). After a discussion regarding the fragments on which no initial agreement was found, an agreement on all of the coded fragments was eventually found (100%).

5. Results

In the results section, teachers’ issues at the start of the career (5.1), at the current moment (5.2) and in between the start of the career and the current moment are described (5.3). Afterwards, the data of two respondents is discussed in more detail (5.4) as well as three identity issues (5.5). Last, the results on the coping strategies (5.6) and the influence of the issues on teachers’ functioning (5.7) are reported.

5.1. Identity issues at the start of their career

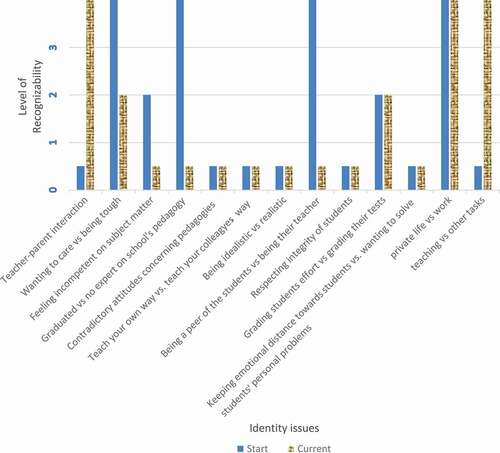

In , the results concerning our first research sub-question are shown. At the start of their career, four identity issues were recognised ‘very much’ by the respondents (when compared to the identity issues that were recognised to a lesser extent). The first issue was: ‘Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough’ (79% of the teachers); Ben explained: ‘At the beginning [of my career], I was still searching for my own classroom management style.’ Heather said: ‘At the start, I really wanted to be liked by the students. Now, that is not that important anymore.’ The second ‘very much’ recognised issue concerned: ‘Being a Peer for the Students vs. Being Their Teacher’ (56% of the teachers); Chris recounted: ‘At the beginning, I only differed by 6 years in age with the students, which made it difficult to be their teacher.’ The third issue that was recognised ‘very much’ was: ‘Private Life vs. Work’ (53% of the teachers); Dionne reported: ‘At the start of my career, I taught 14 lessons, which kept me busy for the entire week and the entire Sunday. That was not possible in the long run. I encountered my limits and I have tried to protect them.’ Peter had a similar story: ‘I realised quickly at the start of my career that in this kind of a job you can work all the time, 7 days a week, 15 h per day. Therefore, I’ve set limits to try to protect myself. I do all of my schoolwork at school. At home, there is time for other things.’ Finally, the fourth issue was: ‘Graduated vs. Not an Expert on the School’s Pedagogy’ (35% of the teachers). The 54-year-old English teacher Eric explained: ‘As a starting teacher, this was an issue for me. When I went through the teacher’s training program, 30 years ago, the curriculum consisted of plenty of theory and hardly any practice in the schools. This was especially with respect to the area of pedagogical content knowledge. I still had a lot to learn.’

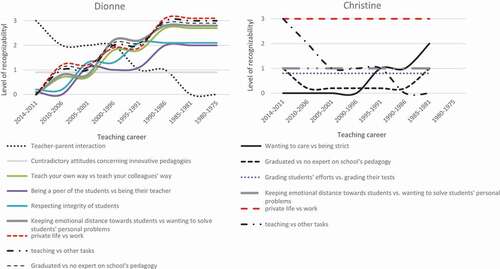

Figure 1. The recognisability of the identity issues at the start and at the current phase of their career (level of recognisability: 0 = not at all recognisable, 3 = very much recognisable).

Among the group of teachers, differences were found to the extent in which they recognised themselves in the identity issues at the beginning of their careers. Some teachers particularly recognised themselves ‘very much’ in many of the identity issues, specifically at the beginning of their career (for instance, Dionne recognised five identity issues ‘very much,’ especially at the beginning of her career, see ), while others did not (for instance, Christine only recognised one identity issue ‘very much,’ particularly at the beginning of her career, see .

5.2. Identity issues at the current moment

At the current moment in their career, the respondents of this study particularly experienced the following three issues ‘very much.’ First, concerning the issue of ‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions’ (47% of the teachers), the 59-year-old Mathematics teacher Marion told us: ‘Parents have become more enforcing in the last few years. Sometimes, they go against my advice, or they object to the school’s decisions concerning their child.’ Ben, the 48-year-old teacher of Care Taking and Ethics mentioned a changed mentality of parents. Second, the issue of ‘Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks’ (41%) was very recognisable. For example, the Dutch language teacher Josephine who explained her graph said: ‘There is a peak in my graph now. I want to teach good lessons. I want to show the students important and beautiful things and I also want to do my other tasks. That is not possible.’ Third, the issue of ‘Private Life vs. Work’ (39%) was also very recognisable for the respondents. For instance, Heather, the 37-year-old History teacher reported: ‘When working in education, family life always gets the short straw, except during the summer holidays.’ The Dutch language teacher Josephine stated: ‘I feel the pressure all of the time.’

All in all, some of the teachers experienced identity issues at the current moment in their careers. For instance, for Christine, five issues were (very much or somewhat) recognisable for her at the current moment of her career (see ), whereas for other teachers (e.g., Dionne), they indicated that the identity issues had faded during their careers and were less recognisable (see ). Christine and Dionne can be seen as representatives of the entire sample of this study: Both recognise issues during their career, for some the recognisability increases or stabilises, for others the recognisability decreases or varies during the career. Christine and Dionne described more details in depth as related in Section 5.4.

5.3. Issues between the start and the current moment of their careers

In between the start of their careers and at the current moment, one issue has remained ‘very much’ recognisable throughout their careers: ‘Private Life vs. Work’ (). During the whole of their career spans, the teachers have been concerned to find a balance between their work and their spare time. Chantal, a 60-year-old Science teacher explained that she had struggled during her entire career in trying to find a balance between her work and her private life: ‘From 1986–1990, I had small children. From 1996–2000, I changed schools, which included new teaching methods and new school subjects. From 2004–2011, I had an almost full-time job, with many responsibilities, such as being a Science Coordinator.’

Two identity issues could be categorised as ‘increasing’ (‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions’ and ‘Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks’). These two issues were not so much recognised by teachers at the start of their career, but at the current moment, these two issues were recognised ‘very much.’ As mentioned before, the mentality of the students’ parents has changed in the last decennium because of Information and Communications Technology (ICT). The parents can more easily contact the teachers through email, and thus, monitor the progression of their children. Concerning ‘Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks,’ Heather explained: ‘The amount of other tasks, apart from the teaching, has increased enormously in the last few years. When I started my career as a teacher, teaching was my core-business. Some other small tasks, I just did as a hobby.’ Four identity issues (‘Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough,’ ‘Feeling Incompetent on Subject Matters vs. Expected to be an Expert,’ ‘Being a Peer for the Students vs. Being Their Teacher,’ and ‘Graduated vs. Not an Expert on the School’s Pedagogy’) were decreasing in their recognisability between the start of their career and at the present moment. Remarkably, the identity issue of ‘Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough’ was identified as being decreasing during their career, but it was still quite recognisable by the experienced teachers (next to ‘Grading Students Efforts vs. Grading Their Tests’). Seven identity issues were unchanging concerning their recognisability.

5.4. A closer look at two respondents: Dionne & Christine

In order to show the variety among individual respondents, two respondents (Dionne and Christine) were selected and described as an example in detail in this section. An overview of the respondents (on a group level) other than Dionne and Christine can be found in .

In , all of the graphs of Dionne and Christine are depicted. For the identity issues that were not recognisable by Dionne and Christine, respectively, their individual figures were left out. As can be seen in , for Dionne, the recognisability for most of the identity issues decreased during her career, whereas for Christine, two identity issues increased and two others stayed unchanged.

Just as in the majority of the sample, Dionne did not recognise the identity issue of ‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions’ at the start of her career in the 1980s. However, during her career, she did experience this identity issue and at the current moment, she recognised it ‘very much.’ Dionne explained: ‘Well, during my career, the students’ parents have become more assertive. They manifest themselves and they ignore the advice of the teachers.’ In a similar vein, Josephine, another respondent, stated: ‘At the beginning of my career, I never got any emails, let alone aggressive or judging ones from the parents.’

For Christine (cf. ), one identity issue has stayed very recognisable during her career, that being ‘Private Life vs. Work.’ Christine wrote: ‘I have experienced this issue during my entire career.’ Christine added: ‘As a teacher, your work is never finished, so the pressure of time is always there. It is a challenge to find a balance between my own time and my work time.’

5.5. A closer look at three identity issues

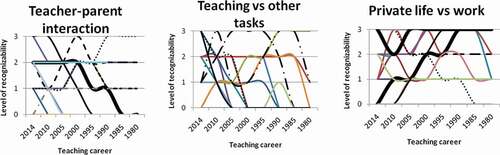

shows that at the current phase of their careers, three identity issues were very recognisable: (1) Teacher vs. Parent Interactions (2) Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks (3) Private Life vs. Work. The first two issues showed an increment during their careers. At the beginning, these issues were hardly recognisable, but at the current moment, they were very recognisable. The issue of a ‘Private Life vs. Work’ has remained ‘very much’ recognisable from the start of their careers up until the current phase. A closer look at these three identity issues showed that the recognisability of an issue was not a strictly linear process (). This was especially true for the identity issues of ‘Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks’ and ‘Private Life vs. Work.’ Quite some variability was found within the career paths of the individual respondents, although some teachers showed a stable line of recognisability during their careers. The lines of the respondents of one particular identity issue sometimes (partly) overlapped, as can be seen in . For reasons of visibility, we chose to depict overlapping graphs as one line/graph.

Figure 3. An illustration of the recognisability of three identity issues during their career1,2.

The two identity issues of ‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions’ and ‘Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks’ have shown an increment in recent years. The identity issue of a ‘Private Life vs. Work’ showed that there were only a few respondents who did not recognise this issue at any point during their career. In addition, most of the respondent’s lines had 1 or 2 as their lowest point, indicating that during their entire careers, the teachers recognised this issue. The graphs further showed that although the teachers recognised themselves in this situation (Private Life vs. Work), the extent to which the individual respondents recognised this varied during their careers. It varied from somewhat (1) to quite some (2) and to very much (3). When compared to a ‘Private Life vs. Work,’ the other two issues were not always recognised by all of the respondents.

5.6. Coping with identity issues at the current moment

The results of our second sub-question concerning teachers’ coping with identity issues showed that most of the participants coped with an issue by finding a solution for themselves (for instance, by trying a different pedagogical strategy). This was the case for five identity issues (‘Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough,’ ‘Feeling Incompetent on Subject Matters vs. Expected to be an Expert,’ ‘Contradictory Attitudes concerning Innovative Pedagogies,’ ‘Grading Students Efforts vs. Grading Their Tests,’ and ‘Keeping an Emotional Distance from the Students vs. Wanting to Solve the Students’ Personal Problems’). Concerning three identity issues (‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions,’ ‘Being Idealistic vs. Being Realistic,’ and ‘Respecting the Integrity of the Students’), most of the participants coped by talking with other people about the relevant identity issue. ‘I discussed it at a team meeting, where I felt much support from my colleagues,’ Chantal stated. For one identity issue (Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks), most of the participants coped with this identity issue by accepting it and putting up with it. Chantal considered this issue to be part of the school’s culture and inextricably linked to the teaching profession. Chris explained how this worked out for him: ‘I used my time and my energy to focus on the students and less on other useless tasks. This was tolerated by my director, since he knows me as a teacher and a pedagogue.’ For four identity issues (‘Graduated vs. Not an Expert on the School’s Pedagogy,’ ‘Teach Your Own Way vs. Teach Your Colleague’s Way,’ ‘Being a Peer for the Students vs. Being Their Teacher.’ ‘Private Life vs. Work’), a combination of ways of coping came to the fore (e.g. talking with other people about the relevant identity issue and accepting it and putting up with it).

5.7. Influencing teachers’ performance at the current moment

Concerning our third sub-research question (‘How do identity issues influence their teaching according to the teachers themselves?’), the following results were found: The three identity issues of ‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions,’ ‘Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough’ and ‘Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks’ negatively affected the participants. When the teachers experienced a negative influence, they often mentioned that this resulted in either them being less committed to the school’s organisation and just focusing on their lessons, or on omitting certain non-teaching parts of their job. Josephine stated: ‘I get disappointed with both the parents and the students and become rather suspicious of them.’ Christine was one of the teachers who considered quitting her coaching tasks in favour of her teaching tasks, because she felt that she could not do both tasks. Because of her work, she sometimes did not sleep well. This made her tired when conducting her work.

The identity issues of ‘Feeling Incompetent on Subject Matters vs. Expected to be an Expert’ and ‘Graduated vs. Not an Expert on the School’s Pedagogy’ decreased in recognisability during their careers. This had a positive influence on their teaching. When the teachers mentioned a positive influence, this was due either to an increment in the knowledge of a subject; more knowledge of students’ learning problems; an increment of teaching skills; and increased self-confidence. Monica stated: ‘This situation of “Graduated vs. Not an Expert on the School’s Pedagogy” affected me in becoming a teacher who keeps learning.’ For Susan, an increase in her teaching skills had a positive influence on her Mathematics classes: ‘I now know better how to use a computer and a smart board.’

6. Discussion

The present study administered experienced teachers a questionnaire that was originally devised for beginning teachers (Pillen et al., Citation2013). One might hope for that identity issues as experienced by beginning teachers disappear during teachers’ careers, yet the results found in the present study showed otherwise. Especially, two issues came to the fore.

6.1. A private life vs. work: always an issue

Of all of the thirteen issues that were under research in this study, the issue of a ‘Private Life vs. Work’ was (very) recognisable during the teachers’ entire career. This is in line with previous research (cf. Beijaard et al., Citation2004; McIntyre, Citation2010; Veldman et al., Citation2013). For instance, McIntyre (Citation2010) studied long service teachers in challenging schools where the teachers spoke about ‘the blurring of physical and emotional boundaries between home and school life’ (McIntyre, Citation2010, p. 601). Although a healthy balance between a private life and work is generally considered to be crucial for someone’s performance (Day, Sammons, Kington, Gu, & Stobart, Citation2006), well-being and job-satisfaction (Canrinus et al., Citation2011), our study has shown that, strikingly, some of the respondents just accepted this issue as a part of their job. In addition, the respondents did not talk about this troubling issue with their colleagues or their superiors. They tried to find a solution by themselves or just accepted it. Some teachers mentioned that this was also related to their ‘no nonsense’ school culture or to just part of the teaching profession. Similar results were reported by Gu and Day (Citation2013) who found that for teachers, the school’s culture was very important, just as was school leadership and the relationships with colleagues.

The experienced teachers in our study were somehow able to deal with this issue of “Private Life vs. Work.’ They usually decreased their time for a private life in order to compensate for the large amount of work that needed to be done. Yet the continuous pressure felt by the respondents had consequences for their private lives. In our sample, the respondents mentioned continuous problems with overworking and stress that resulted in feelings of disillusionment and frustration (Day & Gu, Citation2009; Huberman, Citation1993), burnout (Veldman et al., Citation2013) and attrition (Day & Gu, Citation2009; Rolls & Plauborg, Citation2009), as already mentioned in the introduction. Day and Gu (Citation2007) found in their VITAE study that some teachers succeeded in staying committed and motivated, whereas others were holding on, but losing their motivation (cf. Hargreaves, Citation2005; Huberman, Citation1993). The VITAE study, a large scale longitudinal mixed method study focussed on ‘identifying variations in different aspects of teachers’ lives and work and examining possible connections between these and their effects on pupils as perceived by teachers’ (Day et al., Citation2006, p.102) It is important for schools to realise that teachers still encounter the ‘Private Life vs. Work’ issue (cf. Smith & Rowley, Citation2005). Schools should include work-life balance in their HRM-protocols and offer coaching to those teachers who need it (Runhaar, Citation2017).

6.2. A newly arriving issue: teacher vs. parent interactions

An issue of which the recognisability increased in recent years, according to the respondents, has been the ‘Teacher vs. Parent Interactions.’ In society nowadays, at least in the Netherlands, the parents are more concerned about the grades of their children and the quality of teaching that their children are receiving more than ever before (cf. Duncan, Citation2013; Gaikhorst, Beishuizen, Korstjens, & Volman, Citation2014). The modern technologies which schools are able to offer to parents in order to monitor the learning processes of their children, their outcomes and their behaviour, all contribute to this issue. Moreover, the use of email and social media has enabled both the students and the parents to communicate directly and continuously with the teachers (cf. Veldman et al., Citation2013). In addition, over the last decade, the focus on measurement and the monitoring of student outcomes has increased in schools (cf., Biesta, Citation2009). Both this accountability and accessibility of teachers have given rise to these teacher–parent interactions (cf. Veldman et al., Citation2013; Pillen et al., Citation2013). This is a relatively new issue for teachers. It may also have a negative impact on their experienced work load. Many teachers answer their work emails in their spare time or in their private time, contributing to the endurance of this issue of a ‘Private Life vs. Work.’ Our results show that this particular issue of teacher–parent interactions has arisen over the last several years and it can, in that sense, be exemplary of other new issues that might emerge over time, for beginning and experienced teachers, as well. Societal developments can influence these issues that (experienced) teachers might encounter.

7. Limitations

Due to the qualitative nature of this study, which we have used in order to gain deeper insights into the identity issues of experienced teachers, the number of participants has not allowed for generalising statements. Moreover, this qualitative study has aimed at exploring how experienced teachers cope with generic, every day identity issues. Although the teachers had the opportunity to elaborate on the influences of their (school) circumstances, specific school contexts (i.e. school ethnicity or challenging schools) were not the main focus of this study. In addition, this study has been based on one data source: a questionnaire. Although the questionnaire, which was carefully constructed, has offered opportunities for the respondents to elaborate on their drawn graphs and their answers, there was no possibility for the researchers to ask follow-up questions or to triangulate the results from the questionnaire with other data sources. The teachers experienced the questionnaire as an intense and genuine reflective research tool that took much time and effort.

A retrospective approach was chosen in order to study the teaching careers of the respondents. Therefore, the teachers’ own recollections of the identity issues that they experienced at the beginning of their careers could be influenced by their memory (Melville & Pilot, Citation2014; Orland, Citation2000). A career-long, longitudinal design using different school contexts and with several varied instruments and research tools for the data collection would be ideal, but it would be hard to realise and accomplish, when considering the large time frame (the mean years of experience were 25 years).

8. Conclusions and suggestions for further research

This study found that experienced teachers have encountered several identity issues, as was identified by the novice teachers, which have influenced them in their teaching. Some identity issues have remained difficult throughout their entire teaching careers, while others have disappeared and new ones have arisen. The work-private life balance has, especially, been a continual issue (cf., Pillen et al., Citation2013; Veldman et al., Citation2013; Runhaar, Citation2017). Our results have shown that the teachers hardly talk about this. Following Day et al. (Citation2007), who showed that in-school support is crucial for late-career teachers and their professional identities, this study has underlined the need for in-school support, since some identity issues have remained and the teachers ‘have put up with these issues’ or do not talk about them. These issues may influence teachers’ performances. This study has offered concrete descriptions of these identity issues that need to be discussed in professional development programmes in order to support all of these experienced teachers.

In addition, the results of our study can be used as an eye opener for experienced teachers who have a hard time dealing with specific identity issues. The results have shown that these teachers are not alone in these processes. Teachers experience different issues at different times in their career. The issues that teachers encounter have been central to this study. Future research could focus more on individual teachers, in order to study the diversity of the issues that they encounter and to compare them across various teaching individuals. Next to that, further research should, instead of a focus on situations, include a broader perspective on how experienced teachers maintain their positive professional identity. Also, challenge for further research would be to take a closer look at the personal characteristics of those respondents who recognise many identity issues and to elicit the possible relationships that exist between personal characteristics and the number and the intensity of identity issues that a teacher recognises. In addition, since this study has specifically focused on identity issues that were previously mentioned by novice teachers, future research could also include other issues, as well as the constraints of mid-to-late career teachers, or to focus on the roles of school culture, by examining the issues of teachers from disadvantaged or challenging schools (cf., McIntyre, Citation2010). Furthermore, the nonlinearity of the graphs (in at least three identity issues) might be further examined, while taking personal characteristics and a life’s context more into account in future studies.

In conclusion, experienced teachers also need time for reflection, just as novice teachers do. All teachers may benefit from a form of coaching. Yet most essentially, for all teachers (both beginners and experienced ones), an ongoing and open dialogue about professional identity issues is important.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to Dr. Q. Kools, Dr. R. Schildwacht and Drs. C. Kocken-van Acht, who commented upon the first draft version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna C. van der Want

Anna C. van der Want is a postdoctoral researchers at ICLON, Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching, Leiden, the Netherlands. Her main research interests pertain to teacher professional development and teacher identity during the career.

G.L.M. Schellings

Gonny Schellings is assistant professor at the Eindhoven School of Education of the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands. Her research interests concern professional identity development of (beginning) teachers, learning environments and learning strategies. She received her PhD in 1995 on a study into learning strategies applied in order to learn from instructional texts. At the moment, she is a regional project leader of a national founded government project to support beginning teachers.

J. Mommers

Janine Mommers is researcher at the Eindhoven School of Education of the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands and an experienced teacher and coach in a school for secondary education. Her research interest aims at professional identity development of (beginning) teachers and their professional learning. Janine designed workshops and guidance tools to support beginning teachers in their identity development.

References

- Admiraal, W. F., Korthagen, F. A., & Wubbels, T. (2000). Effects of student teachers’ coping behaviour. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 33–52.

- Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualising teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 308–319.

- Alsup, J. (2006). Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189.

- Beck, C., & Kosnik, C. (2014). Growing as a teacher: Goals and pathways of ongoing teacher learning. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Beck, J. (2008). Governmental professionalism: Re-professionalising or de-professionalising teachers in England?. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(2), 119–143.

- Beijaard, D. (1995). Teachers’ prior experiences and actual perceptions of professional identity. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 1(2), 281–294.

- Beijaard, D., & Meijer, P. C. (2017). Teacher identity development: On the role of the personal and professional in becoming a teacher. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. London, Washington DC: Sage Publishing.

- Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128.

- Beijaard, D., Van Driel, J., & Verloop, N. (1999). Evaluation of story-line methodology in research on teachers’ practical knowledge. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 25(1), 47–62.

- Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment. Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 33–46.

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Bullough, R. V., Jr. (2008). The Writing of Teachers’ Lives–Where Personal Troubles and Social Issue Meet. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35, 7–26.

- Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2011). Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation and commitment: Exploring the relationships between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 115–132.

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. Green, G. Camilli, & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 375–385). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2007). Variations in the conditions for teachers’ professional learning and development: Sustaining commitment and effectiveness over a career. Oxford Review of Education, 33(4), 423–443.

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2009). Veteran teachers: Commitment, resilience and quality retention. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(4), 441–457.

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2010). The new lives of teachers. London: Routledge.

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Kington, A., Gu, Q., & Stobart, G. (2006). Methodological Synergy in a National Project: The VITAE Story. Evaluation & Research in Education, 19(2), 102–125.

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Stobart, G., Kington, A., & Gu, Q. (2007). Teachers matter: Connecting lives, work and effectiveness. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Duncan, H. E. (2013). Exploring gender differences in US school principals’ professional development needs at different career stages. Professional Development in Education, 39(3), 293–311.

- Faber, M. (2012). Identity dynamics at play ( Doctoral dissertation). Utrecht University, Utrecht.

- Gaikhorst, L., Beishuizen, J. J., Korstjens, I. M., & Volman, M. L. L. (2014). Induction of beginning teachers in urban environments: An exploration of the support structure and culture for beginning teachers at primary schools needed to improve retention of primary school teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 42, 23–33.

- Gergen, M. M. (1988). Narrative structures in social explanation. In C. Antaki (Ed.), Analysing social explanation (pp. 94–112). London: Sage.

- Gu, Q, & Day, C. (2013). Challenges to teacher resilience: conditions count. British Educational Research Journal, 39(1), 22–44.

- Guarino, C. M., Santibañez, L., & Daley, G. A. (2006). Teacher recruitment and teacher retention: A review of the recent empirical literature. Review of Educational Re-Search, 76(2), 173–208.

- Hargreaves, A. (2005). Educational change takes ages: Life, career and generational factors in teachers’ emotional responses to educational change. Teachers and Teaching, 21(8), 967–983.

- Hong, J. Y. (2010). Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1530–1543.

- Huberman, M. (1993). Steps toward a developmental model of the teaching career. In L. Kremer-Hayon, H. C. Vonk, & R. Fessler (Eds.), Teacher professional development: A multiple perspective approach (pp. 93–118). Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger.

- Johnston, J. (2015). Issues of professionalism and teachers: Critical observations from research and the literature. Australian Educational Researcher, 42(3), 299–317.

- McIntyre, J. (2010). Why they sat still: The ideas and values of long serving teachers in challenging inner city schools in England. Teachers and Teaching, 16(5), 595–614.

- Meijer, P. C. (2011). The role of crisis in the development of student teachers’ professional identity. In A. Lauriala, R. Rajala, H. Ruokamo, & O. Ylitapio-Mäntylä (Eds.), In Navigating in educational contexts: Identities and cultures in dialogue (pp. 41–54). Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei: Sense Publishers.

- Meijer, P. C., De Graaf, G., & Meirink, J. (2011). Key experiences in student teachers’ development. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(1), 115–129.

- Melville, W., & Pilot, J. (2014). Storylines and the acceptance of uncertainty in science education. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 9(4), 353–368.

- O’Connor, K. E. (2008). ‘You choose to care’: Teachers, emotions and professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 117–126.

- Orland, L. (2000). What’s in a line? Exploration of a research and reflection tool. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 6(2), 197–213.

- Pillen, M. T., Beijaard, D., & Den Brok, P. J. (2013). Tensions in beginning teachers’ professional identity development, accompanying feelings and coping strategies. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 240–260.

- Riessman, K. R. (2008). Narrative Analysis. In L. Given (Ed.), SAGE Enclyclopedia of Qualitative research methods (Vols. 1–2, pp. 539–540). Thousands Oaks, California: SAGE.

- Rolls, S., & Plauborg, H. (2009). Teachers’ career trajectories: An examination of research. In M. Bayer, U. Brinkkjær, H. Plauborg&, & S. Rolls (Eds.), Teachers’ career trajectories and work lives. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Runhaar, P. (2017). How can schools and teachers benefit from human resources management? Conceptualising HRM from content and process perspectives. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 45(4) .

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038.

- Smith, T. M., & Rowley, K. J. (2005). Enhancing commitment or tightening control: The function of teacher professional development in an era of accountability. Educational Policy, 19(1), 126–154.

- Veldman, I., Van Tartwijk, J., Brekelmans, M., & Wubbels, T. (2013). Job satisfaction and teacher-student relationships across the teaching career: Four case studies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 32, 55–65.

Appendix A

Full description of the identity issues used in this study.

Identity Issue A: Teacher–Parent Interaction

Mary teaches chemistry to Josh, a 15-year-old student. Mary notices that Josh has difficulties with chemistry and advises Josh to continue his school career in the humanities domain without the STEM subjects, such as chemistry. Josh’s parents send an email to Mary, stating that Mary should explain the chemistry more clearly and then Josh will understand. They want Josh to continue with the STEM subjects. Mary has difficulties when answering the email. On the one hand, she thinks it is not wise for Josh to study the STEM subjects. On the other hand, she cannot ignore the opinion of Josh’s parents.

Identity Issue B: Wanting to Care vs. Being Tough

To keep order in the class room, Mike needs to be strict with his students. That is difficult, because he wants the students to like him and he wants to foster a good atmosphere in the class room. Mike wants his students to feel that he is there for them, but that does not go along with being strict.

Identity Issue C: Feeling Incompetent on Subject Matters vs. Expected to be an Expert

Nicole’s subject is physics. She thinks that her students expect her to have more knowledge about physics than she actually has. She cannot answer all of the student’s questions concerning the subject matter. She does not know what to do about that.

Identity Issue D: Graduated vs. Not an Expert on the School’s Pedagogy

Geoff has found that he did not learn the things he should have learned during his teacher’s education or that he is not aware of recent educational developments in order to be able to function well in the practice school. Therefore, he finds it difficult to function up to the school’s expectations.

Identity Issue E: Contradictory Attitudes Concerning Innovative Pedagogy

Samir feels that he never makes the right decision during professional development courses and at the teacher education institute. He learned visions about teaching that are different from those of the school.

Identity Issue F: Teach Your Own Way vs. Teach Your Colleague’s Way

Carrie finds that she is very dependent on her team. She feels that she has to teach like her colleagues, a way that does not square with her own way of teaching. She likes to experiment and wants a different way of dealing with her students than that of her colleagues. She does not know what to do. On the one hand, she wants to listen to her colleagues. On the other hand, she wants to try to teach in her own way. According to her, this is the best option for her students.

Identity Issue G: Being Idealistic vs. Being Realistic

Alex feels he is not taken seriously and is considered to be an idealist. Alex hesitates as to what to do. He wants to stand up for himself, in order to be treated seriously. He wants to show that his ideas are not idealistic, but realistic. At the same time, he does not want to be too intrusive. Maybe his colleagues are right.

Identity Issue H: Being a Peer for the Students vs. Being Their Teacher

Eva takes responsibility for her students, but at the same time, she is close to the students, considering her age. She likes to have some fun with them in the class room. She also meets with the students when she goes out. She experiences difficulties when considering the role that she needs to adopt inside and outside of the school with regard to her students. She wants to have some fun with them, but Eva is afraid that if she crosses the line, the students will not take her seriously anymore.

Identity Issue I: Respecting the Integrity of the Students

One of her students took Fatima into her confidence about a personal problem. Fatima is in a conflict with herself. She wants to protect the student’s privacy, but at the same time, she is afraid that the student is a danger to himself or to other people.

Identity Issue J: Grading a Student’s Effort vs. Grading Their Tests

Jana finds it hard to assess the students on the basis of their performances alone. She also wants to take into account the person as a whole,’ because she values the student’s well-being. She experiences this as an issue.

Identity Issue K: Keeping an Emotional Distance towards the Students vs. Wanting to Solve the Student’s Personal Problems

Michael is very concerned about his student’s well-being. He has a hard time accepting that he is not capable of helping his students in the way that he should, in order to live up to their needs.

Identity Issue L: A Private Life vs. Work

Mara wants to perform her teaching job well, but she also wants to be there for her family/roommates. She does not know how to divide her time properly.

Identity Issue M: Time for Teaching vs. Time for Other Tasks

Arnold has just started to work as a teacher and he is wondering whether he can actually be a good teacher. He experiences problems, because he does not have enough time to accomplish all of his teaching tasks together with his other non-teacher tasks. On the one hand, he wants to divide his time equally, in order to keep his school and his colleagues happy. On the other hand, he wants to spend more time preparing his lessons. His students’ right: deserve to receive good lessons.

Appendix B

Excerpt of the Questionnaire

Please read the following situation and answer the following questions.

Situation A:

Mary teaches chemistry to Josh, a 15-year-old student. Mary notices that Josh has difficulties with chemistry and advises Josh to continue his school career in the humanities domain without the STEM subjects, such as chemistry. Josh’s parents send an email to Mary, stating that Mary should explain the chemistry more clearly and then Josh will understand. They want Josh to continue with the STEM subjects. Mary has difficulties when answering the email. On the one hand, she thinks it is not wise for Josh to study the STEM subjects. On the other hand, she cannot ignore the opinion of Josh’s parents.

1a. To what extent do you recognize this situation with others? (Please mark the appropriate answer with an X)

1b. Draw a line indicating the extent to which the situation was recognisable for yourself during your career as a teacher. Please start at the present moment (2014) and draw your graph backwards in time. (From left to right)

2a. When does your graph show peaks? Please indicate the peaks and elaborate on the reasons for these peaks.

2b. When does your graph shows depths? Please indicate the depths and elaborate on the reasons for these depths.

2c. In case there are other remarkable parts of your graphs, you can describe them below.

2d. Is this situation recognisable at the present moment in your teacher career?

Yes → Please answer questions 3–6

No → Please continue with the next situation.

3. What did you feel during this situation? Multiple answers possible. Please indicate with an X.

4. How did you cope with this situation? Please indicate with an X

5a. What was the solution for this situation at that moment?

5b. Who did you talked to? (Please select one answer).

5c. To what extent was this helpful for you?

6. To what extent has this situation influenced your work as a teacher?

Please continue with the next situation.