ABSTRACT

The parenting evidence base is well established, and the question is how best to transfer the evidence to an app. App-based interventions could expand access to evidence-based parenting support; however, current provision lacks rigorous evidence, shows low user engagement, and is primarily for commercial gain. This study aimed at testing the feasibility and acceptability of ParentApp for Teens, an open-source, mobile parenting intervention application based on the Parenting for Lifelong Health Teens programme targeting parents of teens. The objective was to gather feedback from users on the relevance, acceptability, satisfaction, and usability of ParentApp for Teens across contexts in Africa, and subsequently, use the feedback to improve the app experience for target users. Caregivers and their adolescents aged 10–17 years, from nine different countries, were purposefully selected for user testing. The study involved 18 caregivers participating in the programme by using the app for 13 weeks and providing feedback on it through remote, semi-structured interviews that explored the app’s acceptability and usability. Adolescents of six caregivers were also interviewed. Data were analysed thematically. Participants expressed a high level of satisfaction with the app’s content and described it as easy to use and useful. However, views on the app’s animated characters varied. Although effectiveness was not a primary aim of the user testing, several caregivers commented that they perceived their participation in the study had helped to enforce positive parenting skills in themselves. Adolescents’ data supported the caregivers’ reports of less harsh parenting and improved relationships between caregivers and their children due to the caregivers’ participation in the study. Findings indicate the app could be relevant and acceptable in participants’ communities, but possible barriers to its uptake may be lack of android smartphones, lack of data for app download, and inability of non-literate caregivers to read the content.

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that parenting programmes are a feasible and effective approach for improving families’ outcomes particularly violence against children (VAC), and can be delivered across countries, cultures, and contexts (Gardner et al., Citation2016; McCoy et al., Citation2020). However, the high costs of training, implementation and accreditation suggest financial infeasibility in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Mikton, Citation2012). Structural barriers including geographical location, childcare, work demands, and transportation also inhibit accessibility and take-up of services (Weisenmuller & Hilton, Citation2021). In LMICs where the rates of VAC are highest (Hillis et al., Citation2016), preventive services often have minimal reach (Knerr et al., Citation2013).

As internet and smartphone use is growing in LMICs (GSMA, Citation2022a), digital parenting programmes may become a more accessible, cost-effective solution to reaching vulnerable families at scale. With the introduction of new entry-level smartphones, it is expected that in the next three years, the number of smartphone ownership in Sub-Saharan Africa will almost double, reaching an adoption rate of 65% of the region’s population (GSMA, Citation2022b). Several digital parenting programmes have been developed and tested in high- and middle-income countries, with meta-analytic and systematic reviews indicating that they have a similar effect to in-person parenting programmes (Florean et al., Citation2020; Spencer et al., Citation2020; Thongseiratch et al., Citation2020). However, results from other digital social and health interventions in LMICs tend to be more mixed, often due to a lack of formative research (Badawy & Kuhns, Citation2017).

Parenting for Lifelong Health (PLH) is a research initiative focused on improving parenting through evidence-based, freely available, and culturally relevant parenting programmes for LMICs (WHO, Citation2022). Over the past decade, PLH has developed and rigorously tested a suite of parenting programmes across randomised controlled trials (RCT) in LMICs (Cluver et al., Citation2018). One of these is PLH for Teens which targets caregivers with teens aged 10–17 and focuses on increasing positive parenting, reducing harsh parenting, decreasing adolescent behaviour problems, and building positive relationships. PLH for Teens has been tested in rural South Africa through pre and post-test studies and qualitative research (Cluver et al., Citation2016), as well as a cluster RCT in 40 rural and urban communities (Cluver et al., Citation2018). Results from the cluster RCT demonstrated significant positive impact on the family, improving positive parenting practices and reducing child abuse and child behavioural problems.

To address delivery and access barriers, and to overcome COVID-19 restrictions, PLH for Teens has been adapted to be delivered digitally, as a self-guided application (app) called ParentApp for Teens (ParentApp). The app is open source and is developed for offline use. Its core components () are 12 interactive Weekly Workshops (); a habit-tracking tool, ParentPoints; a library that provides instant access to resources, ParentLibrary; and the In-week content such as home practices and fun family activities.

Table 1. Contents of the weekly workshops.

Given the lack of digital family interventions in LMICs, an initial step was to see if, and how, this kind of parenting intervention would be accepted by caregivers. This paper describes the user testing of an early version of ParentApp with a Pan African group of caregivers and their adolescents to assess the relevance, acceptability, usability, and user satisfaction across contexts in Africa. The study’s aims were to assess the target group’s views about the format and content of the intervention, and identify barriers of access and usability to improve the app experience for target users.

Materials and methods

Participants

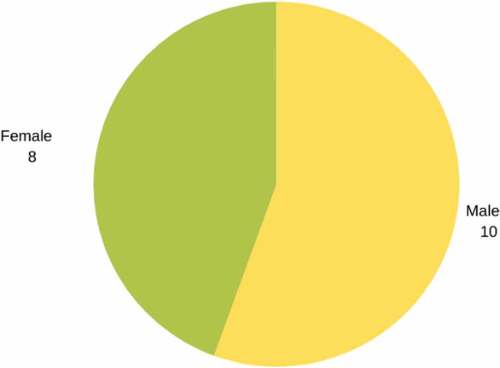

Potential study participants were recruited via convenience and purposive sampling from a range of potential user countries. They were identified from a network of research participants and partner organisations with whom the research team had an existing relationship. Some caregivers participated in an earlier stage of the study which involved testing the app components. Caregivers were approached via phone and/or email to participate if they were caring for an adolescent between ages 10 and 17 years, and had access to an Android smartphone. Recruitment began in April 2021 and lasted for several weeks. From 30 caregivers recruited, 18 () participated in the study; 12 dropped off at the start of the study and did not use the app. Of the 18 caregivers that participated, half were retained at the end of the programme. Responses in a post-programme questionnaire investigating why participants dropped off indicated key reasons for dropping off were illnesses, personal challenges, and time constraints.

Table 2. List of participants (Caregivers).

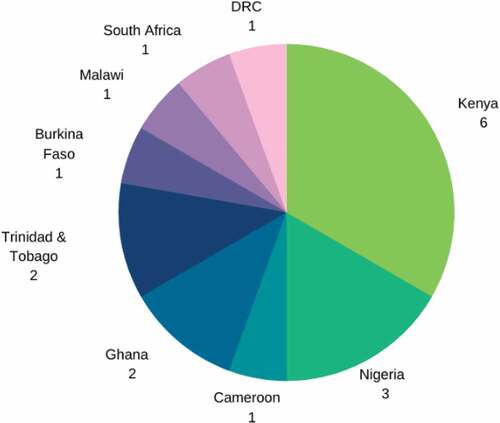

The caregivers (10 male, 8 female; ), were from nine countries: Kenya, Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Malawi, South Africa and Trinidad and Tobago (T&T; ) to ensure a diverse sample. Adolescents were recruited through their caregiver when the caregiver completed the programme. Out of nine caregivers retained at the end of the study, six of their adolescents were interviewed.

Procedures

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Oxford (R69744/RE001), the University of Cape Town (PSY2020-001), and Amref Health Africa (P776-2020). Written or verbal informed assent and consent were obtained from all adolescent participants and their primary caregivers, respectively.

A research team member supported each participant to download the app. Caregivers participated in the parenting programme by engaging with the app and progressing sequentially through the 12 weekly workshops, carrying out home practice activities for the workshops, and using other app features (). They were supported with any technical challenges experienced. Adolescents were not required to use the app but experienced the programme through their caregiver’s home practice activities. For example, the home practice activities of Workshop 2, ‘One-on-One Time’, required the caregiver to spend one-on-one time with their adolescent.

Table 3. Details of how caregivers participated in the user testing of parentApp.

Caregivers participated in individual semi-structured interviews at three timepoints (): early programme, mid programme, and post programme. The interviews explored the app’s acceptability, usability, and the user’s satisfaction. Adolescents participated in one individual semi-structured interview that aligned with their caregiver’s post programme interview. The adolescent’s interview explored adolescents’ perception of the app based on the caregiver’s home practice activities and any changes observed in their caregivers’ parenting. Interviews were remote, using direct phone calls, Microsoft Teams, or Skype-to-phone, in the participant’s chosen language, with most interviews conducted in English. The interviews were conducted by members of the research team and a research assistant. 43 interviews were conducted in total and each lasted 40 minutes on average (range: 16–62 minutes). Adolescents’ interviews were relatively short and only a little of the data were used. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by the interviewer or a research assistant. Through questionnaires, feedback on the app was obtained from three caregivers who were unavailable for interviews. Caregivers were offered mobile airtime to the local equivalent of USD$3.50 as an appreciation for completing each interview. Caregivers were further provided a 2GB data bundle as compensation for data usage. Data consumption was calculated pro rata based on app download, app updates and participation in remote interviews.

The study utilised a semi-structured interview guide comprised of 11–15 questions designed by the research and development team. Interviews followed a funnel approach (Tracy, Citation2013) starting with broad questions, followed by more detailed ones. For example, ‘What do you think about the content of the Weekly Workshop?’. The topic guides were flexible enough to allow further elaboration. The post-programme interview explored preliminary indications of change and potential for sustainment of use.

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted by the first and second authors. A coding theme was developed by reading through a few transcripts. A line-by-line thematic coding was employed (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998), combined with an open coding approach to enable the interview data guide the creation of the categories (Creswell, Citation1998). This was followed by comparison across the interviews to identify commonly occurring themes. Afterwards, the themes were reorganised to create meaningful thematic categories (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998).

Results

Our findings were categorised into six themes: relevance, usability, acceptability, satisfaction, effectiveness, and barriers and facilitators to uptake and sustained use. These are presented () and discussed below with illustrative quotes. Participants were given pseudonyms to maintain anonymity.

Table 4. Qualitative codes and exemplar quotes.

Relevance of the app

The theme of relevance captured participants’ perspectives on how helpful they found the app to be. Overall, participants described the app as relevant and helpful for parenting. They expressed appreciation for the weekly workshops and described them as ‘very useful’, ‘very much educative’, and ‘a bit basic but effective’. However, one participant commented that she did not find the workshop on budgeting interesting. While most participants considered the ParentLibrary helpful and useful, a few said they did not use it due to the content similarities with the weekly workshops. Participants were divided on the relevance of ParentPoints; some thought it was useful and engaging, while others found it unnecessary.

I don’t do the ParentPoints because I don’t find it useful. – Paul, T&T father

Most participants reported that they had successfully engaged with their adolescents in the home practices. However, two participants said it was challenging to discuss budgeting with their adolescents.

It has really helped me to know how to treat my kids. – Abigail, Kenyan mother

The app is a school on its own; it teaches us a lot. – Ben, Kenyan father

Usability of the app

The theme of usability described the ease of downloading and using the app. A few participants reported initial challenges with downloading and using the app. Issues with phone compatibility and space on the phone necessitated a few participants requiring further support to install the app. There were also reports of technical challenges, most commonly, the app freezing. Other technical challenges included slowness in loading and the app returning to the start of a workshop instead of going a step backwards:

I think yesterday we had to go back, and it took us like all the way back and we had to start all over again until we got to where we wanted to go which was just a step back. – Kojo, Ghanaian father

The user experience of a few participants was also adversely affected by the poor internet connectivity in their locality during download. However, most participants stated that they did not encounter any challenges, and notwithstanding the aforementioned challenges, all participants commented that the app was easy to use:

It was easy to navigate. – John, Malawian father

It was very user-friendly … It was very easy even in terms of going into the app. It was so simple. – Emma, T&T mother

Acceptability of the app

The theme of acceptability explored participants’ attitudes towards using ParentApp and their opinions of the app’s features. Generally, participants had a positive attitude about using the app. All participants reported that the language in the app was simple, clear, and easy to understand, and most participants thought the amount of text and font size were suitable. One participant believed the amount of text in some workshops should be reduced. The in-app surveys including rates of physical violence to children were acceptable to all, but one participant reported some discomfort.

There were few questions where I was really not comfortable … (like) how many times I had to spank my own child. – Wakunmi, Cameroonian father

Although a few participants thought there were too many buttons in the app, most participants described the menus and buttons as appropriate and adequate. Among the few participants who commented on the emojis (pictographs), opinions were divided; some liked them, while others thought they might be confusing for people who are not familiar with emojis. While most participants commented that the colours in the app were fine, a few expressed their dissatisfaction. Participants’ views on the animated characters in the app varied; some liked the images, others did not, and a few were indifferent:

The first time I opened it, when I saw the images, I said, ‘Wow!’ – Lydia, Ghanaian mother

They would have made sense to me if they (images) looked more like real people rather than inflated balloons. – Wakunmi, Cameroonian father

Satisfaction with the app

Most participants expressed a high level of satisfaction with the app’s content and described the app as ‘easy to use’, ‘easy to understand’, and ‘friendly’. Most participants expressed satisfaction with the length and order of the weekly workshops, but a few participants thought the order should be modified:

I like everything about the app – all the parent points, the library and everything! – Olivia, Nigerian mother

Comments on the music at the end of the workshops were generally positive, but one participant said they found the music childlike and could do without it. Similarly, a few participants thought the audio messages should be improved, but most participants found them useful:

It’s making me feel I’m connecting with real people, with somebody who understands what I want … and is ready to guide me. – Pearl, Nigerian mother

Possible barriers and facilitators to uptake and sustained use

Participants believed the app would be relevant and acceptable in their communities but pointed out possible barriers such as data costs for downloading the app, the inability of non-literate caregivers to read the app content, and the app imagery. They also mentioned the lack of android smartphones, time constraints, and caregivers not being technologically inclined as other possible barriers.

You know technology is not easy for everyone. For instance, to use this app, one must have a smartphone. – Ben, Kenyan father

Participants were divided on the option of using the app alone or in a group; some preferred to use it alone, others preferred to use in a group, and a few were neutral. Some participants identified that notifications could a be useful reminder for sustained use, but most did not comment on the lack of notifications.

I would like to be having notifications … if I’m like forgetting to open to the app … it will … take me back – Wankunmi, Cameroonian father

Perceived programme impact

All participants who completed the duration of the study perceived that their participation in the user testing had helped enforce their own positive parenting skills. Caregivers reported being less harsh in disciplining their children, spending more time with them, and involving them in decision-making. Other areas of change included being able to better manage anger and stress, and being more relaxed and calm:

One of the biggest changes is Emma don’t get on like a mad woman when she is upset again … I involve him in the decisions I make and … I am very guilty if I don’t spend that one-on-one time with him. – Emma, T&T mother

Data from the adolescents supported caregivers’ report of less harsh parenting and improved relationships between caregivers and children since the caregivers’ participation in the user testing of the app:

He spends more time with me now. - Luty, Cameroonian adolescent

Now I am free to talk to her about my problems … but before, I was afraid to talk to her … – Rachel, Kenyan adolescent

Discussion

Online interventions could revolutionise delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions. Our initial findings indicate that ParentApp was perceived as relevant, acceptable, and satisfactory by the participants who engaged in the app. Most participants found the content useful and helpful. This is a promising sign, as until recently, the majority of digital interventions have been developed, tested, and implemented in high-income and western contexts (Canário et al., Citation2022). Our study demonstrates that even in low-resource settings, and with various levels of technological knowledge and different cultural contexts, people may find digital interventions acceptable and effective. Furthermore, although the user testing did not aim to test the effectiveness of the app, caregivers who completed most of the sessions reported that they perceived the intervention’s content improved their own positive parenting practices. Caregivers indicated that they had befriended their children, involved them in decision-making, and become less harsh when disciplining them. This was echoed by the adolescents who reported similar sentiments. This is in line with other online parenting interventions, which showed how long-lasting engagement is crucial for gaining the desired outcomes (Chen et al., Citation2015).

Despite the high level of acceptability, there were a few usability issues which prevented users from fully engaging with the app. Like other digital interventions (Andrade-Romo et al., Citation2020; Saekow et al., Citation2015), issues included the inability to download or open the app due to technical issues or lack of knowledge regarding app usage. It is likely that these issues contributed to the high rate of drop out which resulted in only 18 of the 30 recruited caregivers participating in the user testing, and only half of those completing the programme.

Users provided valuable feedback for improvement, including requesting push notification reminders. These types of reminders could boost engagement (Blomkvist, Citation2020). Therefore, we aim to implement weekly push notifications including reminders to read content and suggestions of activities. These challenges, which were discovered during the early stages of development, highlight the importance of involving users for input right from the conceptualisation phase of the intervention development (Waterlander et al., Citation2020).

While this study contributes to the current knowledge of digital interventions in LMICs, it is not without limitations. Firstly, most of the participants were involved in earlier phases of the study and were somewhat familiar with the project. Results may have differed if the user testing was carried out among participants who had no prior knowledge of ParentApp. Indeed, these issues go hand-in-hand with any participatory action intervention studies (Jacobs, Citation2010), thus, cannot replace proper pilot testing with participants who have no prior knowledge of, or interaction with, the intervention. Secondly, considering the limited number of participants, in the context of the geographical distribution, it is difficult to draw conclusions due to convenience sampling bias and high drop out.

Despite these limitations, the results suggest that ParentApp has potential and acceptability as a digitally-delivered evidence-based parenting programme in varied settings in the Global South. Findings provide direction for refinements to enhance the app’s potential. These include content adaptions and improvements, and the options to access modules earlier and use human figures instead of cartoons. Future studies should explore intervention and delivery optimisation to identify factors that might affect and boost engagement, such as facilitated human support and reminders. These seem effective in in-person programmes, and their importance might be greater in self-led programmes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the adolescents and their caregivers who took part in this study, the superb technical support and app development provided by David Stern, Santiago Borio and their team at IDEMS International. Thank you to Beryl Waswa, Zach Mbasu and Maxwell Fundi from Innovations in Development, Education and the Mathematical Sciences (INNODEMS) in Kenya who conducted integral interviews and transcriptions with participants in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrade-Romo, Z., Chavira-Razo, L., Buzdugan, R., Bertozzi, E., & Bautista-Arredondo, S. (2020). Hot, horny and healthy-online intervention to incentivize HIV and sexually infections (STI) testing among young Mexican MSM: A feasibility study. Mhealth, 6, 28. PMID: 32632366; PMCID:PMC7327285. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2020.03.01

- Badawy, S., & Kuhns, L. (2017). Texting and mobile app interventions for improving adherence to preventative behaviour in adolescents: A Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 5(4), e50. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6837

- Blomkvist, S. (2020). Competition or Cooperation? : Using push notifications to increase user engagement in a gamified smartphone application for reducing personal CO2- emissions (Dissertation). http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-279464

- Canário, A. C., Byrne, S., Creasey, N., Kodyšová, E., Kömürcü Akik, B., Lewandowska-Walter, A., Leijten, P. (2022). The use of information and communication technologies in family support across Europe: a narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031488

- Chen, Z., Koh, P. W., Ritter, P. L., Lorig, K., Bantum, E. O., & Saria, S. (2015). Dissecting an online intervention for cancer survivors: four exploratory analyses of internet engagement and its effects on health status and health behaviors. Health Education & Behavior, 42(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114550822

- Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Ward, C. L., Gardner, F., Peterson, T., Hutchings, J. M., Mikton, C., Meinck, F., Tsoanyane, S., Doubt, J., Boyes, M., & Redfern, A. A. (2016). Development of a parenting support program to prevent abuse of adolescents in South Africa: Findings from a pilot pre-post study. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(7), 758–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516628647

- Cluver, L., Meinck, F., Steinert, J. I., Shenderovich, Y., Doubt, J., Herrero Romero, R., Lombard, C. J., Redfern, A., Ward, C. L., Tsoanyane, S., Nzima, D., Sibanda, N., Wittesaele, C., De Stone, S., Boyes, M. E., Catanho, R., Lachman, J. M., Salah, N., Nocuza, M., & Gardner, F. (2018). Parenting for Lifelong Health: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a non-commercialised parenting programme for adolescents and their families in South Africa. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000539. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000539

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publication.

- Florean, I. S., Dobrean, A., Păsărelu, C. R., Georgescu, R. D., & Milea, I. (2020). The efficacy of internet-based parenting programs for children and adolescents with behavior problems: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(4), 510–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00326-0

- Gardner, F., Montgomery, P., & Knerr, W. (2016). Transporting evidence-based parenting programs for child problem behavior (age 3–10) between countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis [Article]. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(6), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1015134

- GSMA. (2022a). The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa. https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/sub-saharan-africa/

- GSMA, (2022b). GSMA The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa report 2021 https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/GSMA_ME_SSA_2021_English_Web_Singles.pdf

- Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079

- Jacobs, G. (2010). Conflicting demands and the power of defensive routines in participatory action research. Action Research, 8(4), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750310366041

- Knerr, W., Gardner, F., & Cluver, L. (2013). Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 14(4), 352–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0314-1

- McCoy, A., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Gardner, F. (2020). Parenting interventions to prevent violence against children in low- and middle-income countries in East and Southeast Asia: A systematic review and multi-level meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 103, 104444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104444

- Mikton, C. (2012). Two challenges to importing evidence-based child maltreatment prevention programs developed in high-income countries to low-and middle-income countries: Generalizability and affordability. In H. Dubowitz (Ed.), World Perspectives on Child Abuse and Neglect (Vol.10, pp. 97). Aurora, Colorado: International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect.

- Saekow, J., Jones, M., Gibbs, E., Jocobi, C., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Wilfey, D., & Taylor, C. B. (2015). StudentBodies-eating disorders: A randomized controlled trial of a coached online interventoin for subclinical eating disorders. Internet Interventions, Vlue, 2 (4), 419–428. 2214-7829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2015.10.004

- Spencer, C., Topham, G., & King, E. (2020). Do online parenting programs create change? Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000605

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Thongseiratch, T., Leijten, P., & Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2020). Online parent programs for children’s behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(11), 1555–1568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01472-0

- Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Waterlander, W. E., Luna Pinzon, A., Verhoeff, A., den Hertog, K., Altenburg, T., Dijkstra, C., Halberstadt, J., Hermans, R., Renders, C., Seidell, J., Singh, A., Anselma, M., Busch, V., Emke, H., van den Eynde, E., van Houtum, L., Nusselder, W. J., Overman, M., van de Vlasakker, S.,andStronks, K. (2020). A system dynamics and participatory action research approach to promote healthy living and a healthy weight among 10-14-year-old adolescents in Amsterdam: The LIKE Programme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144928

- Weisenmuller, C., & Hilton, D. (2021). Barriers to access, implementation, and utilization of parenting interventions: Considerations for research and clinical applications. American Psychologist, 76(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000613

- WHO (2022). Parenting for lifelong health: a suite of parenting programmes to prevent violence. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/parenting-for-lifelong-health