ABSTRACT

This article explores Syrian higher education (HE) teachers’ perceptions of their role as change agents in the reconstruction of post-conflict Syria. It utilises the notions of ‘change agent’ and ‘strategic competence’ (previously developed in relation to academics by Idahosa and Vincent) for exploring HE teachers’ capacity to contribute to the post-conflict reconstruction of Syria. This article is based on a small-scale, qualitative study using in-depth interviews to explore the experiences and perspectives of HE teachers who have been working at a conflict-affected university for the duration of the conflict. The study concludes that HE teachers may be considered change agents in post-conflict societies, but that the challenges these teachers face must be taken into account, as must considerations of how the institution and the HE system can facilitate teachers in their change-making remit.

Introduction

Higher education (HE) is considered to make a significant contribution in alleviating conflict and its impacts on societies (UNESCO Citation2017). It functions as a platform where principles and values are imparted to students, teachers and their community, and which builds and extends bridges of reconciliation, peacebuilding and cohesion (Millican Citation2018). However, research shows that HE is ‘often an unrecognized casualty of war’ (Milton and Barakat Citation2016; Arasaratnam-Smith Citation2017; GCPEA Citation2020), and that HE teachers can contribute to tackling the problems of society by acting as agents of change (Milton Citation2017). This article discusses the role of HE teachers in post-conflict societies, an area which has not been researched widely (Pacheco Citation2013; Herath Citation2015). Because of their everyday direct contact with students, HE teachers may make fundamental contributions to ‘promoting peace, building social cohesion and promoting nation-building and national identity’ (Horner et al. Citation2016, 16). This article focuses on the context of Syria; the recent and ongoing nature of the conflict in Syria means that there is as yet relatively little empirical research on the impact of the conflict on HE (Milton and Barakat Citation2016; Dillabough et al. Citation2018b; Milton Citation2014, Citation2017, Citation2018; Parkinson, McDonald, and Quinlan Citation2020; Milton Citation2019; Millican Citation2020), and this paper presents unique data drawing on interviews with HE teachers who have taught in Syrian HE throughout the conflict.

Syria has endured a conflict of almost 10 years (at the time of writing). Due to the severity of the conflict, it is reputedly the case that ‘three decades of developmental progress [were] reversed just within the first three years of conflict’ (Milton Citation2019, 38). Infrastructure, heritage sites and buildings have been looted, damaged or destroyed. Approximately, 400,000 civilians were killed and around half of the population displaced and emigrated (Milton Citation2017; World Bank Citation2017), leading to an unprecedented loss of human capital (Seeberg Citation2017). The World Bank (Citation2017) shows that the economy has been significantly affected due to the loss of human capital, infrastructure destruction and the US and EU sanctions. In 2015, there was an economic recession by 61% resulting in considerable unemployment (52.9%) (The Syria Report November 10, Citation2018). In education, prior to the conflict, about 97% of children had access to primary education and almost 67% accessed secondary education (NRC Citation2018); these figures both dropped to less than 60% during the conflict, much of which reduction can be attributed directly and indirectly to the conflict (ESCWA Citation2016). Men and women had equal access to HE institutions (HEIs), and approximately 100,000 students registered at university by 2000 (Ward Citation2014). However, owing to the conflict, almost two million children have lost access to education (UNICEF Citation2019). Nearly 7,400 schools were destroyed since many have been converted into strongholds or arms depots. Moreover, Syrian universities’ rankings decreased; one university dropped to 9673rd in 2019 from 4654th in 2010 (UniRank Citation2019), and almost 100,000 university students abandoned their studies owing to their displacement (Al-Fanar Media February 6, Citation2015).

This paper is based on a small-scale, qualitative study using in-depth interviews to capture the voices of five Syrian HE teachers who remained in Syria during the conflict for mixed motivations such as their sense of national duty and commitment to help students and their families and to improve the status quo, the lack of suitable opportunities to leave and their hope that the situation would alter and improve. The paper contributes to existing research on the impact of conflict on HE (Milton and Barakat Citation2016; Dillabough et al. Citation2018a; Milton Citation2019; Millican Citation2020; Parkinson, McDonald, and Quinlan Citation2020) and on the role of HE in reconstruction efforts in post-conflict societies (Milton and Barakat Citation2016; Heleta Citation2018; Millican Citation2018). HE teachers play an important role in contributing to post-conflict reconstruction efforts; this article focuses on three key questions which contribute to developing a greater understanding of this role: (i) What has been the impact of conflict on the conditions of HE teaching? (ii) What do HE teachers perceive to be their role in the post-conflict reconstruction phase? (iii) Which factors do HE teachers identify as enabling and constraining their contribution to reconstruction? HE teachers are conceptualised as potential change agents: the article explores what form this takes in post-conflict society. Following a literature review on key debates and discussions about HE in post-conflict settings and the role of HE teachers as change agents, the article then explains the methodology and methods of the study. Findings and discussion are then presented which address the three questions set out above. Overall, the paper argues that HE teachers may be considered change agents in post-conflict societies, but that the challenges these teachers face must be taken into account, as must considerations of how the institution and the HE system can facilitate teachers in their change-making remit.

HE and HE teachers: conflict and reconstruction

Due to the prevailing focus of reconstruction efforts on physical redevelopment (e.g. rebuilding infrastructure), there is relatively limited research on the role of HE in the reconstruction of conflict-affected societies (Milton and Barakat Citation2016). Furthermore, the role of HE teachers in post-war societies has not been widely addressed (Milton Citation2017). This section explores the impact of conflict on HE and the positioning of HE within reconstruction projects, and develops a conceptualisation of HE teachers as change agents.

The impact of conflict on HE and HE teachers

HE experiences devastating effects during conflicts, and teachers are situated at the forefront of these effects (O’Malley Citation2007, Citation2010; UNESCO Citation2010; GCPEA Citation2020). In the conflict in Afghanistan, for example, the HE system collapsed and institutions were damaged or destroyed; an important facet of this crisis was that academics and students migrated and the teaching process ceased (Milton and Barakat Citation2016). In Iraq, HEIs were looted or destroyed due to the war; almost 5000 academics were forcibly displaced (Milton and Barakat Citation2016). Syria has lost roughly 30% of its academics and HE teachers to migration and displacement (Al-Fanar Media July 18, Citation2018), leading universities to recruit postgraduates with little or no teaching experience as substitutes (Al-Fanar Media February 6, Citation2015; Milton Citation2019). Thus, a recognised impact of conflict upon HE teachers is forced mobility, experienced as brain drain by the country in question.

However, there is less recognition of the working conditions of HE teachers who remain in situ. Reading between the lines of other accounts of the impact of conflict upon HE, it is possible to imagine some of the consequences for teachers. For example, the conflict in Iraq decreased students’ enrolment in HE due to different factors including ‘restriction of movement, closures of institutions, and mobilisation of students by armed groups’ (Milton and Barakat Citation2016, 404). Beside the impact of conflict upon the logistics of attending and working in HEIs, HE is also a target for recruitment, at times via radicalisation (Schmid Citation2013; Warnes Citation2015; GCPEA Citation2020). In Afghanistan, for example, education is known to have ‘suffered manipulation and exploitation for ideological purposes’ (Pherali and Sahar Citation2018, 244). From this account, it is imaginable that, in addition to experiencing a loss of colleagues, teachers remaining in situ would be impacted by a general reduction in student numbers, restrictions preventing them from holding classes, loss of students to armed groups. There is a need for more evidence on the impact of conflict not just on HE writ large, but also on the specific impact of conflict on HE teachers – particularly those who remain in country during the conflict.

Reconstruction efforts and the place of HE

In post-conflict societies, reconstruction efforts do not tend to prioritise HE. For instance, almost USD $18 billion was allocated for reconstruction in Iraq, whereas no funding was considered for the reconstruction of HE (Milton and Barakat Citation2016). In fact, in post-war Iraq, beside other post-conflict contexts such as Lebanon, Bosnia and Nicaragua, HE is known to have expanded within a weak state ‘leading to a boom in unaccredited and often low quality institutions outside of state regulatory oversight’ (Milton and Barakat Citation2016, 404). In Syria, the government and international bodies are paying attention to the service sector, infrastructure and manufacturing (Daher Citation2018). While these are of course crucially important for post-war Syria, the HE sector has been neglected. This is arguably because the rebuilding of HE, which brings more indirect and diffuse benefits over a longer period of time – sometimes not until the following generation – does not appear as urgent as rebuilding more practical functions of society. Mirroring the sites of investment for reconstruction, research on reconstruction also focuses on reconstruction projects, particularly the economic, industrial, agricultural and health sectors and trade (Heydemann Citation2017; Milton Citation2019), leaving the HE sector a comparatively neglected terrain.

However, the notion that HE has an important role in nation-building and social cohesion is not new. Makoni (Citation2016) emphasises that HE contributes to nation-building through supporting the economy of countries and preparing graduates for employment. In Palestine, HEIs have contributed to constructing and maintaining a national identity which may have become damaged by conflict (Taraki Citation2015). Similarly, Colombian universities carried out different strategies and activities to contribute to peace and state building in the 1990s (O’Malley Citation2017). This happened through concentrating on ‘including access to training, pedagogical standards of teaching and learning, academic mobility, research and publications, [and] services to community’ in an attempt for ‘developing political autonomy, critical thinking, maintaining links between opposing groups, contributing to peacebuilding and supporting reconstruction via training for state-building and society capacity building’ (O’Malley Citation2017, 28). Arguably, the role that HEIs can play for young people as sites of guidance and citizenship development in times of chaos and change is extremely valuable as a key part of reconstruction efforts. HE is also believed to build peace and reconcile colliding groups and societies (Milton Citation2017). This may be linked in part to the university students’ age (for the majority 18–25), where attending university coincides with an important moment for young people to develop their personalities, hone their skills, and tackle issues and beliefs about violence and intolerance (Milton Citation2018). On campus, students can develop their civic skills and values of social justice and democracy; in the words of Milton and Barakat (Citation2016), ‘campuses offer unique arenas that can act as incubators of civil society’ (412). HEIs also play more technical roles as sources of skill development. Teaching and training programmes in HEIs can equip graduates with important skills for the reconstruction of their countries, as happened in Lebanon in the 1990s following the civil war (Milton 2016). HEIs developed programmes and curricula to suit the reconstruction needs at that time. These proved valuable in the aftermath of 2006 war with the Israeli forces, when highly-skilled and professional graduates contributed substantially in reconstruction (Milton Citation2018).

While the role of HE in the reconstruction of post-conflict states is relatively neglected compared to other areas of reconstruction, previous existing literature shows that HE plays a range of important roles in reconstruction: rebuilding the economy and labour market; contributing to nation-building and peacebuilding; acting as a site of guidance and citizenship development for young people; providing technical skills. All of these aspects of HE rely on the competence, availability and motivation of the HE teaching force.

HE teachers as change agents: conceptual framework

The role of HE teachers in post-conflict societies has not been widely discussed in the literature (Pacheco Citation2013; Heijden et al. Citation2015; Herath Citation2015). Teachers in HEIs have particular tasks and roles (UNESCO Citation2017) to tackle the challenges of a post-conflict society – and for being agents of transformative change (World Bank Citation2005). In a conflict-affected society, HE teachers are assumed to spread the culture of tolerance, respect and understanding among students by promoting critical skills of thinking, communication and collaboration (Milton Citation2017). However, in a post-conflict setting, the teachers have also endured conflict and so may not be in a position to contribute to the fullest extent to reconstruction. It is noteworthy that there are certain factors which can affect teachers in their mission as change agents (Rasheed et al. Citation2016). Rubagiza, Umutoni, and Kaleeba (Citation2016) and Herath (Citation2015) highlight different factors such as the lack of teacher training to cope with conflict-induced changes, government policies for teachers’ support, income, and the provision of resources, and not incorporating in the curricula crucially needed themes of peace, social justice, equality, democracy and human rights (Bennell and Ntagaramba Citation2008). As discussed in the previous section, HE teachers who remain in context during and after conflict are in a unique position in their societies. They are both undoubtedly marked by the conflict and the hardships it causes both on a personal and professional level. They are also poised to act as agents of change within the reconstruction process, where HE is tasked with a variety of roles to play within this process. It is vitally important to explore this nexus of constraint, responsibility and possibility further in order to understand not just how HE teachers should contribute to post-conflict reconstruction, but also to what extent they can contribute.

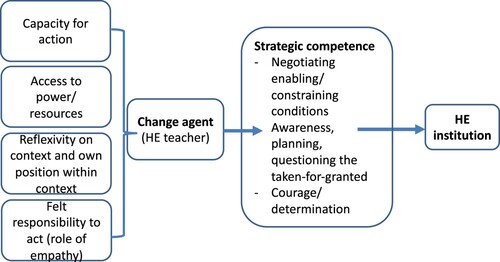

Idahosa and Vincent (Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b) have developed a corpus of work conceptualising academics as change agents in post-conflict societies, which we draw on for the conceptual framework of this article (see ). Importantly for our purposes, Idahosa and Vincent’s conceptualisation is based on the interplay between structure and agency, meaning that constraints are recognised and built into strategies for change. In their view of social transformation, it is important to take into consideration ‘the human agent’s capacity for action and the degree of limitation placed on such capacity for action by social structures’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018, 15). It is therefore necessary to recognise that ‘an individual’s capacity for action … is only possible if the position within which they find themselves gives them access to power and resources that enable them to act in such a way that creates change’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018). The implication of this conceptualisation is that the ‘ability/willingness/capacity to take action’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018, 16) are not conceived as internal characteristics but rather as emerging from ‘develop[ing] a critically altered consciousness of one’s context and one’s role/position in that context in relation to others who inhabit that context’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018, 17). As such the role of change agent is a relational construct which involves reflexivity on one’s own privilege and disadvantage within social structures, in combination with ‘a felt responsibility to act’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018). Idahosa and Vincent (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018) also highlight the importance of empathy within the role of change agent.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework. Source: Authors, collating concepts from Idahosa and Vincent (Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

In addition to defining the role of change agent, Idahosa and Vincent (Citation2019b) also discuss the notion of ‘strategic competence’ which is needed for change agents to bring about change. Against the backdrop of the university as an ‘institutional context that consists of differing enabling and limiting conditions’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b, 148), strategic competence is defined as the ‘ability to negotiate this terrain of ongoing conflicts and to engage context-specific strategies to achieve their goals’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b). It is an ongoing state of awareness, not just involving action but also ‘always looking for ways to achieve a specific goal regardless of obstacles encountered’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b, 152). Moreover, strategic competence also involves the ‘ability to question the taken-for-granted’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b), meaning that change agents query the frame of action as well as planning the actions they will take. Finally, strategic competence is imbued with an affective dimension, involving ‘having courage and being able to overcome fear’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b). The notions of change agent and strategic competence provide a useful framework () for exploring further the capacity of HE teachers who have remained in Syria throughout the conflict to contribute to post-conflict reconstruction of Syria.

The study

This paper is based on a small-scale, qualitative study which sought to contribute depth of knowledge rather than generalisability. Because of the challenges of researching societies which are undergoing or which have recently experienced conflict (Goodhand Citation2000; Barakat et al. Citation2002; Idris Citation2019), the study prioritised safety and accessibility over, for example, principles of representative sampling. The study is based on HE teachers (academics on teaching contracts) working at one department in a university in Syria (the name has been omitted for anonymity purposes) which has been strongly affected by the conflict. These teachers remained in Syria due to different reasons such as the lack of opportunities to leave, the impact of their families on their emigration choices, their feeling of moral and national commitment to stay in Syria and the lack of financial resources. The choice of HE teachers as the target group of this study has been motivated by the aim to explore the specific role that HE teaching (as opposed to e.g. research outputs) might have in the recovery of Syria while living in conflict. The first author, who conducted the empirical research, is himself a former HE teacher in Syria and the participants formed part of his professional networks. Using a purposive and convenience sampling strategy (Collins Citation2017), the first author utilised his personal networks and managed to recruit five HE teachers for the study. Although the teachers were all based in the same department, the nature of their subject specialism meant that they also taught classes in other departments and faculties across a number of disciplines, meaning that these teachers were able to present a helpful overview of the institution in addition to their own department. All of the teachers were on teaching contracts with no research allocation; hence the focus on the role of HE teachers on post-conflict reconstruction. The participants have all been assigned pseudonyms and details of their institution, department and discipline have been concealed to protect their identities – a consideration of utmost importance when researching in a (post-)conflict setting. Ethical approval for the study was granted through the approvals processes of the University of Warwick in the UK where the first author conducted this study, having relocated from Syria ().

Table 1. Details of study participants.

The semi-structured in-depth interview was the method utilised to collect data from the participants. In-depth interviews are important when the aim is to gain deeper knowledge and insights about a certain situation from a relatively small number of individuals (Winwood Citation2019). The semi-structured interview guide was developed in advance with specific questions, but these questions and their order was adapted within the interviews, according to how the participants brought different topics into focus during their responses. The first author conducted the interviews with participants using an online video-conferencing software as he was based in the UK at that time. Although this mode of interviewing can be challenging in situations where there is limited internet connectivity, the interviews proceeded smoothly, with minor connection interruptions at times, and allowed the researchers to access data directly from the Syrian context without engaging in risky travel. Interviews ranged from 90 to 150 min. They were transcribed by the first author.

To analyse the interviews, thematic coding was used to develop codes and themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) in response to the three main questions posed for this article (the impact of the conflict on HE teaching; the perceived role of HE teachers in post-conflict reconstruction; the factors which enable and constrain the contribution of HE teachers to reconstruction). Both authors independently coded the interviews and then compared and combined codes into themes. The interviews included both questions which were directly related to the conflict and teaching within a (post-) conflict setting, and others which were not directly related to conflict. The latter were explored to see how participants brought up the conflict even when not directly asked about it. Although there were some questions in the interview guide which directly related to the three research questions, we coded the whole interviews as participants responded to the questions of their own accord while responding to other questions. We then applied the constructs of change agent and strategic competence as outlined above to the thematically coded data, and our analysis is therefore informed by these constructs. The themes which were developed from the coding are presented below, in relation to each of the three key questions.

HE teachers as change agents in the reconstruction of post-conflict Syria

In conceptualising HE teachers as change agents who have the potential to contribute to the reconstruction of Syria, we are working with the notion that HE teachers who have remained in Syria throughout the conflict are both poised to contribute to reconstruction and bearing the negative impacts of conflict on their personal and professional lives. As such, we argue that it is essential to explore the impact of the conflict on HE teachers and their work, and the institutional conditions they are working in, as well as the specific role of HE teachers. This approach works with the nexus of constraint, responsibility and possibility discussed above, and adds to the question of what teachers should do the question of what they can do, given the circumstances. Through our analysis, we explore the structures which shape HE teachers’ working conditions and their potential to act as change agents exercising strategic competence. It is important to begin the analysis with recognition of the bravery and persistence of the participants in this study, who have endured devastating changes to their lives during the period of conflict, and yet who have continued to teach classes in a university that has likewise experienced devastating change. From their measured accounts of a situation that, due to its longevity, has become normality for these teachers, it is possible for the dire effects of conflict to appear less pervasive than perhaps they are. This formed part of the discussions between the authors, where the first author also spoke from the position of conflict-as-normality, with much of the data seeming unremarkable, while the second author as an outsider queried some of the normalcy constructed between the interviewer and participants. The below analysis has emerged from these discussions, which we wanted to recognise as part of writing from and about conflict.

The impact of conflict on the conditions of HE teaching

In exploring the role of HE teachers as change agents, we needed to explore the conditions for change-making. This formed the basis of the first question we were seeking to answer in this article: ‘What has been the impact of conflict on the conditions of HE teaching?’. The first thematic coding process, therefore, explored the different ways that the participants identified in which conflict had impacted upon the conditions of teaching in HE. It was important to establish this in order to understand the conditions in which teachers have been operating during the conflict; if HE teachers are constructed as potential change agents, we need to understand the conditions which shape their potential contribution. This aligns with the structure/agency discussion in Idahosa and Vincent’s (Citation2018, Citation2019b) work, where inherent to the change agent construct is the recognition of the limitations on a change agent’s capacity to act. As Idahosa and Vincent (Citation2018, Citation2019b) explain, universities are particular institutions which form the terrain for academics to operate as change agents – as hierarchical institutions with reified processes, change occurs in universities through strategic actions which are in keeping with individuals’ access to power and resources. However, the conflict has a further impact on the power and resources that HE teachers can access. In this section, then, we explore the conflict-impacted university as the terrain for HE teachers to act as change agents. The data for this analysis was drawn from specific interview questions pertaining to the impact of conflict, as well as references to conflict in participants’ responses to other questions. We identified six themes, all of which included at least three codes with the exception of one theme with just one code (the positive impact of conflict), which we considered to constitute an important exception rather than an anomaly.

Participants in the study identified ways in which the configuration of institutional arrangements within their university impeded teaching (theme 1). While they recognised that institutional conditions were already challenging before the conflict due to under-funding of the HE sector, they identified ways in which teaching conditions had worsened. These included electricity supply issues and outdated facilities (see also Crossette Citation2016), worsened budget constraints and inexperienced and/or unsupportive administration (due to brain drain and increased pressures on administration). Adam noted: ‘Administration has become more about signing papers and stamp-sealing documents than providing actual support to teachers’. This also included the curriculum being outdated and lacking practical application, due to the deficit of resources for curriculum reform. There were also issues relating to the size of classes being impacted by the conflict, with some classes being too large and others being very small, depending on how the institutional teaching arrangements were configured around lack of teaching staff and/or students. Implications of the changes were timetabling issues and insufficiency of preparation time. Participants also identified that classes were often cancelled because of nearby fighting and missile attacks, meaning they could not teach classes. Linked to institutional arrangements, participants identified a dearth of resources to aid teaching which had been exacerbated by conflict conditions (theme 2). This included a lack of technology, equipment and resources (e.g. for field trips) and a paucity of library books. For instance, Noura stated, ‘It’s really difficult to carry your own laptop, speakers and the other stuff and go to the university’.

Aside from institutional conditions, participants identified negative issues relating to students which shaped their conditions for teaching (theme 3). They found that students had poor attendance and low motivation, that they were nervous, distracted and afraid, that they arrived at the university with insufficient knowledge to begin their courses, as their schooling had also been disrupted by conflict (echoing findings from Leigh Citation2014). Rand, for example, stated ‘They [students] missed the sense of encouragement, the reason and cause to learn and study. I heard it a lot: “Why do I have to study?”’. Finally, participants were also aware of students losing their lives to the conflict. In an opposite sense, one participant identified that some students were positively affected by the conflict (theme 4), as it made them highly motivated to learn in order to make change in society. Noura stated: ‘We have many students whose enthusiasm increased after the war happened’.

Participants identified ways in which the quality of teaching was affected by the conflict (theme 5). Brain drain of experienced, qualified HE teachers was noted as a key factor impacting teaching quality overall (see also Warnes Citation2015; GCPEA Citation2020), with the knock-on effects being that students were therefore unable to access these experienced teachers’ knowledge, that under-qualified teachers were brought in to fill the gaps and that HE teacher training was impacted (as also found by Rose and Greeley Citation2006; Al-Fanar Media February 6, Citation2015). HE teachers were unable to access professional development opportunities such as conferences. Participants also noted that teacher attendance was affected by the conflict conditions, and that some teachers had died due to the conflict. In addition to the impact of the conflict on teaching quality, the study has also identified that HE teachers’ quality of life and security has been impacted by the conflict. Similarly to Milton’s (Citation2019) findings, financial concerns due to low and/or irregular salary payments have meant that many HE teachers are working in more than one job. This leads to low teacher motivation, which is exacerbated by higher pressure placed on teachers, extra teaching load and extra work necessitated by needing to change the approach to planning in the altered conditions. Participants felt unappreciated by the university, and that there was a stagnation of the workforce occurring during the long conflict. The conflict itself meant that teachers’ journey to the university was unsafe, the university premises were unsafe, and that they were experiencing intense psychological stress because of the war. Fadi stated, ‘We had times we had fire around us here at university. We lived scary moments of death’. They had experienced a significant change in their quality of life due to the conflict, moving into basic concerns for survival.

HE teachers’ perceptions of their role in the post-conflict reconstruction phase

Against the backdrop of the structural constraints, we now move on to analyse the ways in which HE teachers in the study positioned themselves as change agents who can make a difference during the post-conflict reconstruction phase. HE teachers who remained in Syria throughout the conflict were clearly negatively affected by the conflict conditions, and yet are perfectly placed to contribute to social change through their work. As described above, academic change agents operate with ‘a felt responsibility to act’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018, 17), empathy (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2018), and a relational understanding of their own position in relation to others’ more and less privileged positions in that context. The second thematic coding process explored the participants’ perceptions of their role as HE teachers in making change during and after conflict. In order to argue that HE teachers are change agents in a post-conflict scenario, it is necessary to explore to what extent, and in which ways, HE teachers position themselves as change agents. Again the data was drawn both from responses to questions targeting this issue and from across the data set where applicable. Here we identified eight themes, each of which included at least three codes.

The participants in the study conveyed high expectations of themselves as change agents in multiple ways. Despite the challenging context they were living and working in, they felt that HE teachers should not passively wait for assistance from the university and country, but should rather exercise strategic competence for change making. It was essential in their view to take responsibility for their own professional development (theme 1), for example, by updating their teaching methodologies and building cooperation between teachers to create communities of practice. Participants also considered that HE teachers could play an important role in post-conflict reconstruction (theme 2), by for example, using their subject specialism for reconstruction efforts (e.g. architecture), making students aware of their role in rebuilding the country and therefore have an indirect impact on reconstruction through the students, shedding light in the wider social context on the impact of war on students’ lives and rehabilitating students after the conflict. For example, Adam stated, ‘Rebuilding is easy compared to rehabilitating, which is HE teachers’ responsibility’. Rand noted, ‘They [students] need to have awareness of what responsibility they have for the future of this country, and they should have tolerance as well’. Beyond the contribution to reconstruction, participants considered that HE teachers could more broadly prepare the future of the country through their work with students, thus forming the new generation and future leaders (theme 3). For instance, they aspired to raise students’ aspirations from degree completion to social contribution, to change outdated views and perspectives, to shape students’ character traits for positive change, to encourage students’ future planning to prepare for the labour market. Fadi considered that ‘Everything [multiple skills] is necessary for their [students’] struggle to build the new Syria after all what happened’.

Participants in the study showed they were deeply aware of being relationally positioned with regard to their students, with strong ideas of their role as HE teachers in forming future citizens within a specific agenda that are echoed in other studies in this field such as Buckland (Citation2005) and Milton (Citation2018). They saw it as their responsibility to develop knowledgeable, qualified students (theme 4) equipped with knowledge and technical skills to the extent that they can compete on an international level. They also saw it as their responsibility to form global citizens (theme 5), by instilling tolerance and respect and responsibility and helpfulness, raising students’ awareness of relevant issues beyond the standard curriculum – and making students aware of the causes of war (such as intolerance, ignorance) (see also Herath Citation2015; Milton Citation2019). Adam for instance opined, ‘We should prepare professionals ready to rebuild the country [by] getting students aware of the real causes of the war: ignorance, intolerance and indifference’. As change-makers themselves, they also aspired to make students change makers. In addition to shaping the attitudes and specific knowledge and skills of students, participants considered that HE teachers should develop students’ transferable skills (theme 6), for example, debating, technological, problem-solving, information gathering, interpersonal, communication, self-management, team-work and cooperation skills. Finally, in relation to the empathy aspect of the academic change agent role, two themes emerged. Participants viewed that HE teachers needed to develop closer relationships with students (theme 7), by acting as role models, sharing experiences with students, paying more attention to students’ needs and listening to and learning from students. Participants also identified an important role for HE teachers to act as a source of encouragement for students (theme 8), by instilling hope and providing comfort and moral support, combating demotivation and pessimism as well as short-term thinking, teaching students to be strong and confident.

Factors enabling and constraining HE teachers’ contribution to reconstruction

From the previous two sections, it is clear that HE teachers in the post-conflict context of Syria are exhausted and surrounded by structural challenges, and that simultaneously they are also placing a high degree of pressure on themselves personally and professionally to contribute to post-conflict reconstruction. These competing pressures require high levels of strategic competence, or the ‘ability to negotiate this terrain of ongoing conflicts and to engage context-specific strategies to achieve their goals’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b, 148). Strategic competence, as explained above, does not just involve action, but also involves an ongoing state of awareness, where change agents seek opportunities and strategies to make change, and demonstrate the ‘ability to question the taken-for-granted’ (Idahosa and Vincent Citation2019b, 152). The final thematic coding process engaged with participants’ own analyses of how the conditions for HE teaching would need to change for them to fulfil their full potential as change agents. This section therefore particularly focuses on change that would need to happen within HEIs and the HE sector in Syria in order to accompany and assist HE teachers in bringing about the change that they see as their role to implement. Again this data is drawn from targeted interview questions and more general discussions occurring across the dataset. There are eight themes emerging from this analysis, all of which included at least three codes, with the exception of one theme including two codes.

In order to fulfil their remit as change agents, participants identified that there would need to be changes at a sector level in order to enable them to deliver on their aspirations as laid out in the previous section. They identified a need for an attitude change at institutional and sector-wide levels (theme 1), with a sense of a shared mission of collaboration for change and greater appreciation of teachers (in part delivered by formalised pay and promotion processes as well as boosting morale). Participants identified a need for more strategic planning at the ministry level (theme 2), with a clear plan for the sector, redeployed budget for the sector and more efficient bureaucratic processes. They also identified the need for clearer HR (Human Resources) processes at sector and institutional levels (theme 3), including the need for more highly trained HR managers and the requirement for clearer regulations pertaining to job descriptions and hiring staff. Angie, for example, noted that ‘Unfortunately, we don’t have ‘job descriptions’. People [teachers] don’t really know what they have to do’. Finally at a sector level, participants identified two themes relating to curriculum. Given the relatively prescriptive nature of the HE curriculum (which HE teachers nonetheless worked around in order to bring their own content and pedagogical strategies), teachers wished for a national-level curriculum review (theme 4) in order to deliver on the knowledge, skills and personal development they saw as necessary for the future generation. They advocated the revision of curriculum content and resources, including the need for more international and more employability-related content as well as the use of international standards to evaluate the curriculum. They also argued for the need for revision of the permitted modes of delivery (theme 5), hoping for more teacher autonomy regarding content and more practical learning to be permitted.

At an institutional level, participants stated that improvements in university-level governance and communications processes would help them to enact their roles as change agents (theme 6). For instance, they felt that university regulations and policies (including in relation to incentivising publishing and research) (see World University News August 25, Citation2017) should be reviewed in the light of the need for the reconstruction of the Syrian HE sector. They also identified that there would be a more cohesive approach if there were more communication between universities as well as within each university. Participants identified that improvements to services and facilities within the university would help them to develop the skilled students they aspired to form (theme 7), including improved technological support, classroom improvements, library improvements. Training was mentioned by most participants (theme 8); participants identified that personal efforts for self-development would not suffice given the task at hand. They noted that HE teachers would benefit from subject training and pedagogy training, but also that HE teachers (and administrators) urgently needed training on bringing about social change and dealing with post-conflict issues in students’ lives. Fadi asserted that

We may need some educational courses. Some specialists might come and give them [teachers and administrators] insights about how the war affected the students. They [students] were affected personally, psychologically, and even their ideas and attitudes towards life have changed, so those specialists might help the teachers to deal with those students affected.

Discussion

It is clear from the study findings that HE teachers who remained in Syria during the conflict have faced significant challenges in their professional and personal lives. As discussed in the literature section, these challenges have been previously documented in the relatively sparse literature in this area, but the everyday working experiences have been less covered – with a focus on the impact on higher education as opposed to teachers – and the connection between challenges and the capacity to act is a novel contribution of this article. Working within an under-funded HE system in Syria that has then been further impacted by conflict means that HE teachers have faced multiple stresses and barriers, which constitute structural constraints on enacting change through their professional roles as HE teachers. These constraints form the backdrop for HE teachers acting as change agents in post-conflict reconstruction – teachers’ capacity to act and their access to resources, key aspects of becoming change agents, are deeply impacted by conflict conditions.

Notwithstanding the structural constraints for change-making, it was abundantly clear that the participants in our study had a clear and well-developed notion of their role as change agents both in and beyond the conflict phase. As noted in the literature section, this aspect of our study goes beyond existing literature, as HE teachers rarely feature in accounts of post-conflict reconstruction. HE teachers in our study set out multiple professional responsibilities ranging across their own and students’ development, and wider social development of the country in the post-conflict phase. The core aspects of the academic change agent construct were evident in the findings, including: a personal sense of responsibility; relational responsibility for the students due to their relative seniority; empathy for students. Our study, therefore, indicates that HE teachers were primed to contribute to post-conflict reconstruction, but that their potential for action was limited by structural constraints.

The findings show that, while HE teachers are aware of what they need to do at a personal level in order to work as academic change agents, they are also very aware of the ways in which they could be more supported in their work, and what is needed to facilitate their work. Far from taking for granted the system in which they are working, they are evidently interrogating the norms and seeking opportunities for the changes they are trying to make to operate at a more systemic level. As change agents, they are operating with reflexivity and engaging in strategic competence in order to work within the constraints they face. It is clear that HE teachers who have remained in post during a conflict are concerningly stretched and yet desperate to use their in-depth contextual knowledge to bring about change in the post-conflict period. Currently, these teachers argue that they have to make personal, individualised efforts to enact change; yet they have depleted resources to seize the opportunities for action that they are identifying. Our analysis overall identifies HE teachers as key actors in the reconstruction process, but as actors who require institutional and governmental support in order to carry out their important work. The initial attributes in the change agent framework, therefore, loop back to the end-point of the HE institution (and HE system), in a cycle of enhanced challenge – or, in the opposite and hoped for scenario for the future, a cycle of enhanced opportunity for change.

Conclusion

This article has shed light on an important yet marginally researched (Milton Citation2019) area, which is the role of HE teachers in the reconstruction of conflict-affected societies, in this case in post-war Syria. In conjunction with previous research in this area, the article argues that HE teachers may play an important role in contributing to reconstruction. However, the article also recognises the devastating effects of conflict on universities and individuals working within them. We argue that the role of the HE teacher in reconstruction, particularly in terms of developing future citizens who have a social conscience and who aspire for a peaceful future, should be further recognised within research on and for post-conflict reconstruction. This argument is accompanied with caution that HE teachers’ capabilities to contribute to a reconstruction agenda are both perfectly honed by in-depth contextual experience and also hampered by the experience of living and working in a conflict-affected country. While HE teachers expressed a deep-set, felt responsibility to act as academic change agents, it was clear that they required further support at institutional and sector-wide levels in order to enact that change that they aspired to make. The study has presented rare data from HE teachers who, unlike many of their colleagues who emigrated, remained in situ during the conflict period. It is important to capture these on-the-ground experiences in order to feed into debates on the place of HE in reconstruction efforts. The article has also contributed to furthering the applicability of Idahosa and Vincent’s (Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b) academic change agent construct by consolidating the ideas into a conceptual framework. This study invites policy makers to support HE teachers in their change making endeavours, and it encourages curriculum designers and university administration to amend the assessments criteria and involve teaching topics and subjects about peace, social justice, and tolerance to promote social cohesion and educate students about the causes of war, such as ignorance and intolerance.

Given the paucity of research in this area and the relative neglect of HE teachers as change agents in post-conflict societies, there is much further work to conduct in this area. For instance, this study took a snapshot approach with a single in-depth interview with a small group of participants. Future research could include more universities, more participants and could take a longitudinal approach to explore change in attitudes and practices over time. Moreover, the sizeable population of displaced Syrian HE teachers could be explored in terms of their potential contribution to reconstruction. This article has made an initial foray into this research area, arguing for the recognition of HE teachers as change agents in post-conflict societies – but change agents whose contribution should be fostered and supported, in order that they can form the next generation of citizens.

Acknowledgements

The authors dedicate this article to Syrian HE teachers who have struggled against multiple challenges to continue with their important work, and in particular to the participants who contributed to the study, whom we thank for their time and considered contributions. This article is based on research conducted for the MA Global Education and International Development dissertation. We would like to thank the Said Foundation who funded the first author’s place on this MA, and Professor Paul Warmington, who supervised the dissertation study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Fanar Media. 2015. “To Be Syrian and a Professor: Recipe for Tragedy”. Al-Fanar Media, February 6. http://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2015/02/syrian-professor-recipe-tragedy/.

- Al-Fanar Media. 2018. “Syrian Higher Education Faces a Long Recovery”. Al-Fanar Media. July 18. https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2018/05/syrian-higher-education-faces-a-long-recovery.

- Arasaratnam-Smith, Lilly. 2017. “Intercultural Competence: An Overview.” In Intercultural Competence in Higher Education: International Approaches, Assessment and Application, edited by A. L. Arasaratnam-Smith and K. D. Deardorff, 1–12. London: Routledge.

- Barakat, S., Margaret Chard, Tim Jacoby, and William Lume. 2002. “The Composite Approach: Research Design in the Context of War and Armed Conflict.” Third World Quarterly 23 (5): 991–1003. doi:10.1080/0143659022000028530.

- Bennell, Paul, and Johnson Ntagaramba. 2008. Teacher Motivation and Incentives in Rwanda: A Situational Analysis and Recommended Priority Actions. Kigali: Rwanda Education NGO Cooperation Platform.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Buckland, Peter. 2005. Reshaping the Future: Education and Post-conflict Reconstruction. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Collins, Kathleen. 2017. “Sampling Decisions in Educational Research.” In The BERA/SAGE Handbook of Educational Research, edited by Dominic Wyse, Neil Selwyn, Emma Smith, and Larry Suter, 280–292. London: SAGE.

- Crossette, Barbara. 2016. “Syria’s Academic, Caught ‘Between a Hammer and a Hard Place.” Pass Blue, February 7. http://passblue.com/2016/02/07/syrias-academics-caught-between-a-hammer-anda-hard-place/.

- Daher, Joseph. 2018. “The Political Economic Context of Syria’s Reconstruction: A Prospective in Light of a Legacy of Unequal Development.” CADMUS, December 5. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/60112/MED_2018_05.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

- Dillabough, Jo-Anne, Olena Fimyar, Colleen McLaughlin, Zeina Al-Azmeh, Shaher Abdullateef, and Musallam Abedtalas. 2018a. “Conflict, Insecurity and the Political Economies of Higher Education: The Case of Syria Post-2011.” International Journal of Comparative Education and Development 20 (3/4): 176–196. doi:10.1108/IJCED-07-2018-0015.

- Dillabough, Jo-Anne, Olena Fimyar, Colleen McLaughlin, Zeina Al-Azmeh, and Mona Jebril. 2018b. Syrian Higher Education Post-2011: Immediate and Future Challenges. London: Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara).

- ESCWA. 2016. “Syria at War: Five Years On.” Report. ESCWA.

- GCPEA. 2020. “Education Under Attack.” Online Report. https://protectingeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/eua_2020_full.pdf.

- Goodhand, Jonathan. 2000. “Research in Conflict Zones Ethics and Accountability.” Forced Migration Review 8: 12–15.

- Heijden, H. R. M. A., J. J. M. Geldens, D. Beijaard, and H. L. Popeijus. 2015. “Characteristics of Teachers as Change Agents.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 681–699.

- Heleta, Savo. 2018. “Higher Education in Post-Conflict Settings.” In The International Encyclopaedia of Higher Education Systems and Institutions, edited by Pedro Teixeira and Jung Shin, 1–4. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Herath, Sreemali. 2015. “Teachers as Transformative Intellectuals in Post-conflict Reconciliation: A Study of Sri Lankan Language Teachers’ Identities, Experiences and Perceptions.” PhD diss., University of Toronto.

- Heydemann, Steven. 2017. “Rules for Reconstruction in Syria”. Brookings, December 20. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/08/24/rules-for-reconstruction-in-syria/.

- Horner, Lindsey, Laila Kadiwal, Yusuf Sayed, Angelina Barrett, Naureen Durrani, and Mario Novelli. 2016. “Literature Review: The Role of Teachers in Peace Building.” The Research Consortium on Education and Peacebuilding, January 10. https://educationanddevelopment.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/the-role-of-teachers-in-peacebuilding-literature-review.pdf.

- Idahosa, Grace, and Louise Vincent. 2018. “The Scales Were Peeled from My Eyes”: South African Academics Coming to Consciousness to Become Agents of Change.” The International Journal of Critical Cultural Studies 15 (4): 13–28. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1581142.

- Idahosa, Grace, and Louise Vincent. 2019a. “Enabling Transformation Through Critical Engagement and Reflexivity: A Case Study of South African Academics.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (4): 780–792. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1581142.

- Idahosa, Grace, and Louise Vincent. 2019b. “Strategic Competence and Agency: Individuals Overcoming Barriers to Change in South African Higher Education.” Third World Quarterly 40 (1): 147–162. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1535273.

- Idris, Iffat. 2019. Doing Research in Fragile Contexts: Literature Review. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

- Leigh, Karen. 2014. “In Turkey, Syrian Students Turned Laborers, or Jobless.” Syria Deeply. March 10. http://www.syriadeeply.org/articles/2014/01/4522/turkey-syrian-studentsturned-laborers-jobless/.

- Makoni, Munyaradzi. 2016. “Higher Education, Quality Assurance and Nation-building.” University World News, May 13.

- Millican, Juliet. 2018. “The Social Role and Responsibility of a University in Different Social and Political Contexts.” Chap. 1 in Universities and Conflict: The Role of Higher Education in Peacebuilding and Resistance, edited by Millican Juliet, 13–28. New York: Routledge.

- Millican, Juliet. 2020. “The Survival of Universities in Contested Territories: Findings from Two Roundtable Discussions on Institutions in the North West of Syria.” Education and Conflict Review 3: 38–44.

- Milton, Sansom. 2014. “The Neglected Pillar of Recovery: A Study of Higher Education in Post-war Iraq and Libya.” Igarss 2014 (1): 1–5.

- Milton, Sansom. 2017. Higher Education and Post-conflict Recovery. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Milton, Sansom. 2018. “Reconstruction and State Building.” Chap. 7 in Higher Education and Post-Conflict Recovery, edited by Milton Sansom, 141–175. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Milton, Sansom. 2019. “Syrian Higher Education During Conflict: Survival, Protection, and Regime Security.” International Journal of Educational Development 64: 38–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.11.003.

- Milton, Sansom, and Sultan Barakat. 2016. “Higher Education as the Catalyst of Recovery in Conflict-Affected Societies.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 14 (3): 403–421. doi:10.1080/14767724.2015.1127749.

- NRC. 2018. “Accessing Education in the Midst of the Syrian Crisis”. NRC, March 20. https://www.nrc.no/news/2018/april/accessing-education-in-the-midst-of-the-syria-crisis/.

- O’Malley, Brendan. 2007. Education Under Attack: A Global Study on Targeted Political and Military Violence Against Education Staff, Students, Teachers, Union and Government Officials, and Institutions. Paris: UNESCO.

- O’Malley, Brendan. 2010. Education Under Attack 2010. Paris: UNESCO.

- O’Malley, Brendan. 2017. “Where Universities Are Active Agents of Peace Building.” University World News, November 11.

- Pacheco, Ivan. 2013. “Conflict, Postconflict, and the Functions of the University: Lessons from Colombia and other Armed Conflicts.” PhD diss., Boston College.

- Parkinson, Tom, Kevin McDonald, and Kathleen Quinlan. 2020. “Reconceptualising Academic Development as Community Development: Lessons from Working with Syrian Academics in Exile.” Higher Education 79: 183–201. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00404-5.

- Pherali, Tejendra, and Arif Sahar. 2018. “Learning in the Chaos: A Political Economy Analysis of Education in Afghanistan.” Research in Comparative and International Education 13 (2): 239–258. doi:10.1177/1745499918781882.

- Rasheed, Muhammad, Asad Humayon, Usama Awan, and Affan Ahmed. 2016. “Factors Affecting Teachers’ Motivation.” International Journal of Educational Management 30 (1): 101–114.

- Rose, Pauline, and Martin Greeley. 2006. “Education in Fragile States: Capturing Lessons and Identifying Good Practice.” Centre for International Education, January 1. https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/Education_and_Fragile_States.pdf.

- Rubagiza, Jolly, Jane Umutoni, and Ali Kaleeba. 2016. “Teachers as Agents of Change: Promoting Peacebuilding and Social Cohesion in Schools in Rwanda.” Education as Change 20 (3): 202–224.

- Schmid, Alex. 2013. “Radicalisation, De-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation.” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, March 1. https://www.icct.nl/download/file/ICCT-Schmid-Radicalisation-De-Radicalisation-Counter-Radicalisation-March-2013.pdf.

- Seeberg, Peter. 2017. “Costs of War. The Syrian Crisis and the Economic Consequences for Syria and Its Neighbours.” Centre for Mellemoeststudier. https://www.sdu.dk//media/files/om_sdu/centre/c_mellemoest/videncenter/artikler/2017/seeberg+article+december+17.pdf?la=da&hash=036B891760640DFAC45CE883DDB5B7D4E5E93A36.

- The Syria Report. 2018. “Syrian Investors Create New Lobby Group”. The Syria Report, November 10. https://www.syria-report.com/news/economy/syrian-investors-create-new-lobby-grou.

- Taraki, Lisa. 2015. “Higher Education, Resistance, and State Building in Palestine.” International Higher Education 1 (18): 18–19.

- UNESCO. 2010. Protecting Education from Attack. A State of the Art Review. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2017. “Higher Education in Crisis Situations: Synergizing Policies and Promising Practices to Enhance Access, Equity and Quality in the Arab Region.” UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/Beirut/HIGHEREDUCATION.pdf.

- UNICEF. 2019. “Fast Facts: Syria Crisis.” UNICEF, February 20. https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/5426/file/SYR-FactSheet-August2019.pdf.pdf.

- UniRank. 2019. “University Rankings”. UniRank, July 20. https://www.4icu.org/reviews/4381.htm.

- Ward, Sally. 2014. “What’s Happening to Syria’s Students During the Conflict?” British Council, July 17. https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/whats-happening-to-syrias-students-during-the-conflict.

- Warnes, Richard. 2015. “Radicalisation and Universities.” European Association for International Education, August 20. https://www.eaie.org/blog/radicalisation-at-universities.html.

- Winwood, Jo. 2019. “Using Interviews.” Chap. 2 in Practical Research Methods in Education: An Early Researcher’s Critical Guide, edited by Lambert Mike, 12–22. London: Routledge.

- World Bank. 2005. Reshaping the Future: Education and Postconflict Reconstruction. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank. 2017. “The Toll of War: The Economic and Social Consequences of the Conflict in Syria.” World Bank, July 10. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/27541/The%20Toll%20of%20War.pdf.

- World University News. 2017. “Culture clash – National vs International Publishing.” World University News, August 25. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20170823092038922.