ABSTRACT

Transit-oriented development (TOD) is a prominent planning model that connects sustainable mobilities with land use. While this interface is crucial for sustainable development, it also requires, we argue, that all typesof mobilities are considered. Therefore, this paper scrutinises how recreation and its mobilities have been studied within academic TOD literature. The review reveals a small number of studies of recreation, and by paying attention to their diverse geographical settings the scattered knowledge becomes even more apparent. Thereafter, to illustrate the consequences and situate our reading, we offer a place-based critique of the TOD planning in a Swedish city. The case captures how policies silence local resourcesfor recreation, not least by misinterpreting the modernist planning legacy. Finally, we argue that integrating recreation in the TOD model is as important as it is challenging: it requires a reconsideration of the urban ideal that TOD relies upon.

1. Introduction

There is currently a drive towardscompact cities, proposed as a way to enhance social life and improve conditions for sustainable development (Adelfio et al. Citation2021). Transit-oriented development (TOD) is one of the planning models brought forward for inspiring planners worldwide in developing the compact city (Bertolini Citation2017). With its specific focus on mobility and land use connections, TOD targets sustainable development by supporting public transport and active transportation, planning for walkable cities with mixed land use close to public transport nodes (Bertolini Citation2017; Calthorpe Citation1993). Taking the mobility – land use interplay into consideration is indeed crucial for sustainability. However, such a strategy or model need to cover all kinds of mobilities that interacts with land use. Previous studies indicate that this is not necessarily true for TOD. Planning, in TOD terms, has been portrayed as a means of creating travel routes for necessary and functional journeys (see e.g. Papa and Bertolini Citation2015). Furthermore, what is addressedis primarily active transport in terms of the ‘last mile’ to and from the station (Knowles, Ferbrache, and Nikitas Citation2020), in line with an emphasis on the logics of the transport node rather than the place (Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019). This calls for a review of how non-utilitarian travel is treated in TOD research and planning. This paper argues that recreation, as a matter of land use and mobilities, provides a crucial and critical lens through which the contemporary TOD discourse needs to be examined and then modified to reach its ambitions for a sustainable city.

The importance of recreational mobilities is further elaborated on in the following section. Thereafter, we stress the need for a context-sensitive critique of TOD literature, drawing on policy mobilities research. This is followed by a literature review of TOD research and its engagement with recreation as a matter of mobility and land use. To contextualise our review and its implementations, a complementary minor case study of Swedish municipal planning for TOD is introduced. The paper ends with a discussion and concludes that there is a need for diversifying the urban model upon which TOD is based.

2. Recreation and the compact city

Mobilities for and as recreation are not a marginal aspect of everyday life, nor are their environmental impacts insignificant. Given the increasing volume of leisure travel, and the severe health challenges of a sedentary society, these aspects need to be addressed in contemporary urban planning (Ettema and Schwanen Citation2012; Freeman and Quigg Citation2009; Lowe Citation2018; Sallis et al. Citation2006). In addition, there are the challenges of a sustainability shift in our leisure travels, including recreational mobilities. Today, leisure travel accounts for 30% of all travel in Sweden (compared to 50% for work- and school-related travel), and it accounts for nearly 52% of total distances travelled. Moreover, almost 60% of leisuretravelled kilometres are taken by car (Transport Analysis Citation2017).

If a strong focus on sustainable mobilities is evident within TOD research, a specific urban norm is equally prominent and the model fits well into contemporary theories of the compact city as a sustainable urban form (Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019). The urban norm, heavily influenced by new urbanist ideals, draws on the aesthetic features of an (often European) "traditional city". These ideals aim to contribute to a sense of community and social change (McCann and Ward Citation2010; Sharifi Citation2016) with density and compactness used as key features of a good plan (Adelfio et al. Citation2021; McFarlane Citation2015). This ‘ideal type’ of a traditional city reduces urban complexity to a function of physical attributes and systems, separating the city from nature or the non-urban environment (Wachsmuth Citation2014).

Crucially, the specific model of the city which TOD relies upon comes out of a critique of the international style, or modernist planning, especially the car-based and low-density development, which reached its peak in the 1960s and 1970s (MacLeod Citation2013; see e.g. Newman and Kenworthy Citation1996). However, this was also the golden era for recreational planning (Pries and Qviström Citation2021). Leisure, recreation and play were deeply embedded in modernist planning. This "space age" (Gold Citation1973), with vast open areas for recreation and play prepared for (and materialised) the future "leisure society", but indoing so also realised modernist planning ideas and aesthetics. With the new urbanism critique, recreation was reinterpreted as not being part of the city, but rather pushed out of it to an imagined greenbelt, thus reconstructing a divide between city and country (Qviström Citation2015). Urban outdoor recreation, both as land use and as an activity in itself, thus became silenced. Given this history, outdoor recreation is not just any "residual category" (Star and Bowker Citation2007) in the TOD model. It considers a more general critique of how the embedded compact city ideal (and its critique of modernist planning) frames thekinds of mobilities and land uses in TOD. Our question, then, is if there is an ambition today to bring recreation as mobility and land use into the conceptualisation of TOD, or doesthe compact city ideal (and critiques of modernist planning) still set the agenda for what kinds of mobilities and land uses could be given a place in TOD.

2.1. Situating the TOD literature

This study is based on an understanding of knowledge as context-dependent, and therefore at least partly transformed when assembled and implemented elsewhere (Latour Citation1999). As Robinson (Citation2016) reminds us, we need to unearth this "locatedness" of knowledge production when engaging with international planning models. The implications of a situated epistemology has been explored in contemporary planning research, in studies of how local knowledge of specific places can be incorporated into planning (e.g. Beauregard Citation2015; Nielsen et al. Citation2019) and in research on policy mobilities revealing how knowledge is being transformed when moved from one place to the other (e.g. Alfredo et al. 2022; Carr Citation2014; McCann and Ward Citation2011; McFarlane Citation2010; Vicenzotti and Qviström Citation2017; Wood Citation2016). Yet, despite the apparent similarities to policy mobilities, the format of the literature review has not been questioned within this discourse. Therefore, with our review we aim to spark methodological discussions on how to examine international research concerning context-sensitive practices. Following Østmo and Law, a literature review translates context-sensitive cases into a universal scheme (Østmo and Law Citation2018). In this process of translation, the reviewer is likely to disregard the specific importance of geography (and history) by adhering to conventions on how to sort out general (or abstract) knowledge and structure a review. Differences in place and planning history are thus easily set aside due to a modern idea of scientific progress. If we aim to gain an overview of previous research, such abstractions and translations are hardly possible to avoid. What we can do, however, is to be aware of and consider the implications of such (mis)translations, but also reestablish some of the references to specific places, projects and histories. Furthermore, we also need to be explicit about our own base for interpreting the results, in this case primarily the specific planning context within which we study and evaluate TOD projects. While such an approach is a challenge given the limited space of an article, we contextualise our review by offering a discussion on the geographic context of the reviewed papers, but also by bringing in a minor case study to situate our reading as well as the effects of the TOD planning discussed.

3. Recreation in TOD research

Our review aims to investigate the role of recreation as a matter of mobilities and land use within transit-oriented development. We gathered literature for the review through structured searches in Scopus and Web of Science and selection was based on the appearance of the defined search terms in the abstract, title, or author’s keywords. Only peer-reviewed papers in English were selected that were published during all recorded years until January 2022. Searches were made using the terms recreation, leisure, sport, physical activity, active transportation and transit-oriented development or TOD (see ). By drawing on these five search terms we aimed to collect a wide range of articles directly or indirectly engaging with recreation in TODs, with special attention to active recreational practices. Active transportation allows us to find papers exploring the interactions between active recreation and transportation, leisure and recreation, to grasp a broad scope of papers setting recreational mobilities into a context of leisure and well-being.

Table 1. Summary of results from search for transit oriented-development and keywords.

Initial compilation shows that only 3% of the papers on TOD use any of the search terms. Although this is a small number, we have observed a slight increase in papers combining TOD and recreation. In 2019, the same search terms accounted for only 2% of the total amount of TOD articles.

To delve deeper into the literature, we read all the papers, structuring our inquiry with three questions: What types of mobilities are represented? What geographies of land use for recreation are disclosed? And how are recreation, sports, leisure, physical activities and active recreation conceptualised? By asking these questions, we hope to unveil if and how recreation as mobility and land use are considered an element in TODs.

Seven papersFootnote1 were excluded from further analysis as they only concerned indoor activities, shopping and (passive) entertainment, using the wide concept of leisure without further definition or explicitly focusing on non-leisure mobilities /activities. One of the excluded papers only mentions the search terms in the abstract. The remainder of the papers are presented and discussed under the following headings.

3.1. Mobilities for and as recreation

Active transportation is either researched as a mode of utilitarian transport or daily commute that benefits environmental sustainability (Duquet and Brunelle Citation2020; Iamtrakul and Zhang Citation2014) or as a factor for health (Hu et al. Citation2014; Morency et al. Citation2020). Without differentiating between mobilities, these papers provide no way of analysing mobilities for recreational purposes.

In other papers, physical activity is rendered as a function of utilitarian transport, not as recreational activity. Again, focus is on patterns of work commutes and daily errands. Any physical activity or recreational experience is merely a positive side effect (Langlois et al. Citation2016; Park et al. Citation2019; Sreedhara et al. Citation2019; Thornton et al. Citation2013; Thrun, Leider, and Chriqui Citation2016; Yang et al. Citation2019). Similarly, regarding recreation as an issue for land use planning, we see how recreational land uses are rendered as transit corridors, rather than space for recreational activities. Again, recreation is a possible side effect but not a prime focus. As an example, Park et al. concludes that ‘there is a value in constructing parks or public open spaces near rail stations for the purpose of promoting walking trips and, potentially, other physical activity’ (Park et al. Citation2019, 6).

A number of papers do indicate that mobilities for or as recreation differ from utilitarian travels. Recreational mobilities happen at other times, such as evenings and weekends (Tan et al. Citation2020) and change over time (Brown and Werner Citation2009), depart from and target other types of destinations (Glass et al. Citation2020), or are conducted via other travel modes (Mamdoohi and Janjani Citation2016). None of these studies delve deeper into these differences, leaving recreation as an unexplored anomaly in the otherwise functional and repetitive work-commute patterns.

3.2. Land use, networks and places for recreation

In several papers, the search terms appear as a general quality in descriptions of TOD. Both Meng et al. (Citation2021) and Knowles (Citation2012) show that access to recreational facilities are a core value of TOD as living environments, acting as a pull factor to attract new residents. Land use, or places and networks, for recreational activities are rarely discussed, but rather lost in a general description of mixed land use. However, a few exceptions can be found. Lu et al. (Citation2018) provide a detailed description of how geography, in the form of street networks for recreational walking differs from old and new TOD neighbourhoods in Hong Kong. Meng et al. (Citation2021) and Park et al. (Citation2019) disclose the need for parks as places for recreational activities, an amenity that today is lacking, according to Meng et al. (Citation2021). Deponte, Fossa, and Gorrini (Citation2020) use the effects of recent Covid-19 restrictions to show how density poses a risk of crowding and congestion and argues for a rediscovery of the low-medium density city.

Two papers go deeper into recreational land uses in TOD. Garcia and Crookston (Citation2019) look into the use of a recreational corridor in Salt Lake City, US, which shows that access to recreational amenities are currently unequally distributed both geographically and socioeconomically. While the recreational corridor in the study extends beyond the TOD area, it intersects with a core transit corridor. Here, at the intersection between recreational and transit corridors, Garcia and Crookston point to possibilities for stronger integration, improving the accessibility of both corridors. The existence of a recreational landscape amenity within, or at least in direct relation to a TOD, thus strengthens equal access to recreational mobilities in ongoing development.

With the aim of displaying the limits of a one-sided focus on proximity to urban amenities, Qviström, Bengtsson, and Vicenzotti (Citation2016) show how landscape amenities, such as natural areas for recreation, are important aspects of the everyday life of TOD residents. By showing how senior residents in a new TOD in Sweden rely on the existence of external private spaces for recreation, in the form of second homes, Qviström et al. reveal a paradox between the wish for sustainable travel within the TOD and increasingly unsustainable car transit related to recreational mobilities. Their analysis shows how recreational amenities within TOD encourage passive engagements (such as walking through a park to another destination), while private amenities provide space for a more active engagement, indicating the need for further research on the types of recreational activities enabled in TOD areas.

3.3. The geography of the TOD research

Geographically, North America and Asia are dominant empirical locations for the reviewed papers (see ). While providing informative environments for studying TOD, these regions are internally complex. Policy frameworks, mobility patterns and recreational preferences are likely to vary both within and between locations.

Table 2. the geographic location for reviewed studies, per contry/region and continent.

We also note that a substantial part of the reviewed papers rest on an understanding of the urban model as a transferable and non-contextual mode of planning, where changes in physical structure lead to similar effects in all geographic contexts. Such a view on comparing non-contextual implementation could lead to the continuous neglect of everyday life practices and experiences of urban users (Thomas et al. Citation2018), as well as the neglect of the intricate spatial relations connecting TODs with surrounding landscapes (Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019).

On the other hand, some studies challenge the generic approach and calls for an increased sensitivity towards local contexts, both in terms of locating findings in relation to continent and country and also locating them internally within the same city. Deponte et al. argue for a move towards a ‘site-specific planning paradigm’, looking to existing medium-density settlements for development, rather than the dominant ‘site-saving’ paradigm of TOD, characterized by a high concentration of residents and services in a limited space (Deponte, Fossa, and Gorrini Citation2020, 137). Lu et al. (Citation2018) call for a nuanced understanding and their analysis of TOD neighbourhoods in Hong Kong shows that spatial design and planning histories create fundamentally different opportunities for walking, though align with similar TOD principles.

Lu et al. (Citation2018) go further, discussing how the extensive TOD research from the US is difficult to compare to Chinese TODs, as scale, size and policy frameworks diverge greatly between these locations. An illustrative example can be found in Knowles (Citation2012) analysis of Ørestad, a newly developed TOD in Copenhagen, Denmark. Knowles’ analysis does not disclose that the Ørestad project was fraught with local protests, as the development took place on public green land, used for leisure and recreation (Rehling Citation2017). One could thus argue that this specific TOD worked to reduce the total land area for recreational purposes, even if access to recreational facilities is used as a marketing factor for Ørestad (Knowles Citation2012). This case is but one example, and it shows the importance of a context-sensitive approach when reviewing both TOD practice and research. Specific knowledge of other cases in the reviewed literature could arguably disclose similar complexities. Hence, research on planning models needs to be situated both geographically but also within policy framework and historical context.

4. When TOD meets Swedish modernist planning

In order to situate our reading, but also to better understand the effects of the absence of recreation in TOD research, we present a case study of a Swedish TOD. With the case study, we want to bridge the empirical question of recreation as an aspect of TOD, with a methodological question of how context-independent review approaches obscures local geographies.

By selecting a Swedish municipality as case study, we are able to conduct a critical examination of recreational aspects in TOD set in comparison to a rich history of recreational and leisure planning in earlier planning paradigms (Giulianotti et al. Citation2019; Pries and Qviström Citation2021). The selection of the Upplands Väsby municipality in particular rests on two main criteria. First, there is an explicit use of the TOD model in key planning documents. Second, the case provides an opportunity for studying how spatial contexts that are often criticised for being unsustainable, here modernist urban layouts, are being translated (or as we will discuss, mistranslated) in the current planning paradigm. We do not attempt to ‘control for difference’ compared to the reviewed papers (see Robinson Citation2016), but to illustrate how TOD models filter through local preconditions, creating local-specific outcomes.

As it is the municipal government that holds responsibility for most land use planning in Sweden (Schmitt and Smas Citation2019), we examine local planning from a strategic comprehensive planning standpoint, encompassing both natural, rural and urban areas, as well as legally binding detailed development plans. The empirical material consists of a selection of municipal policies, plans and documents from several municipal departments and sub-departments. By comparing statements and ambitions set on a strategic level with what becomes materialised in detailed development plans, we focus on the geography of land use emanating from the planning process. Teasing out the chronology (see Meyer Citation2001) of a planning case study is not always easy, as planning is far from being a linear process moving from idea to implementation (Carr Citation2014). Nonetheless, to understand the consequences of planning influenced by a TOD discourse, we need to begin to decipher how ambitions, geographies and strategies are drawn together to assemble Upplands Väsby as a TOD.

4.1. Upplands Väsby: from green suburb to mixed use city

Upplands Väsby Municipality with its 44 000 inhabitants is located in the north part of the Stockholm region in Sweden. The municipality has a long history of integrated transit and residential development. From being a small village along a new rail line in the late 1800s, Upplands Väsby went through a rapid process of urbanisation starting in the 1950s and culminating in the 1970s with a new residential and commercial centre and commuter train station. These historical transit-oriented developments (see Knowles, Ferbrache, and Nikitas Citation2020) are now being converted into a contemporary TOD, pairing a dramatic rebuilding of the station area with extensive urban regeneration. Below, we trace the development from green modernist suburb to compact TOD.

4.1.1. The making of a green suburb

Upplands Väsby Municipality was encompassed in the national interest in health, outdoor life and recreational planning, captured in the slogan of "Sports for All", that permeated Swedish public governance in the 1960s and 1970s (see also Giulianotti et al. Citation2019; Moen Citation1991; Statens Planverk Citation1977). Active forms of recreation and outdoor activities were focal points, deriving from dominant nationalistic discourses on sports, health and nature, coupled with concerns about sedentariness in modern society (Pries and Qviström Citation2021). During the 1960s leisure planning became a prominent topic in planning the urban geography of Upplands Väsby. From primarily focusing on rural areas or urban fringe zones as areas for recreation, recreation now became embedded at the neighbourhood scale within the urban area. Ambitions for leisure planning culminated with the 1976 leisure plan in the which political goals of equality were combined with a careful inventory of the well-developed recreational geography (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation1976).

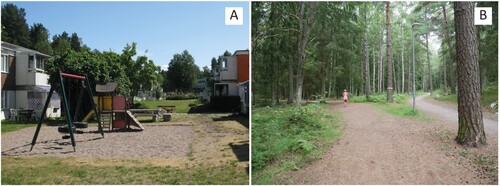

The materialization of this planning ambition can still be seen across Upplands Väsby. An intricate structure of urban green spaces meander though and between residential areas. Small-scale football pitches, tennis courts and playgrounds are distributed at regular intervals throughout the neighbourhoods. Places for diverse recreational activities are merged with recreational corridors for mobilities such as walking, running and skiing. Together with larger sports facilities, both within the urban area and beyond, the recreational geography in Upplands Väsby comes to the forefront as a detailed network, deeply entangled in the everyday geography of the district and transgressing the rural/urban divide (see also Pries and Qviström Citation2021). Even if not all elements of the legacy of modernist recreational planning have been maintained over the years, this recreational infrastructure still forms a fundamental part of the provision of outdoor recreation facilities in Upplands Väsby.

4.1.2. From suburb to city

The building boom of the 1960s and 1970s faded during the following decade to and almost stand-still during the 1990s. In order to revive the municipality and its economy a new strategy of moving ‘from suburb to small town’ was launched in 2005 (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2005). This claim for the future becomes bolder in a 2013 policy, updated and refined in 2018, aiming to move from suburb to city (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2013a, Citation2018b). The very concept of a city, and the aim to "build a city", is set in sharp opposition to what is described as the existing suburb typology. In these policies a city is compact, but the compactness is not a goal in and of itself, rather it ‘helps to fill streets and squares with human life as basis for a rich cultural and commercial supply, it offers housing for many and an effective infrastructure’. (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018b, 5. Italics in original).

Via a definition of the elusive Swedish concept of Stadsmässighet, often used in contemporary Swedish planning debates to denote a "city character", in line with the recent trend for compact cities in Sweden (see Tunström Citation2007), the municipality sets out a list of qualities for the future city. Mirroring the urban ideal also found in the TOD model, Upplands Väsby should be filled with lively public spaces, have clear delineations between private and public land, have varied architecture and good connections for walking, biking and public transit (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018b). Recreation is also a quality of the future city, in the form of ‘parks that are the lungs and rooms for recreation of the city’ and the city should ‘create opportunities for […] leisure time, play and places for informal sports’ (Ibid., 3). Even if important for the future city, such ‘space-consuming’ qualities like recreational facilities are also described as being in conflict with the overarching goal of density (Ibid., 5). As a solution, the policy asks for careful considerations when prioritising land uses. Actual strategies presented for reaching these urban qualities do little to offer support for such considerations. Morphology, architecture, physical structures and street grid patterns are dominant tools for making the future city, according to the municipal policies (Ibid). Hence, recreation is acknowledged as a valuable quality for an urban environment, but no measures are presented to create strategies for strengthening or preserving this quality in actual implementation.

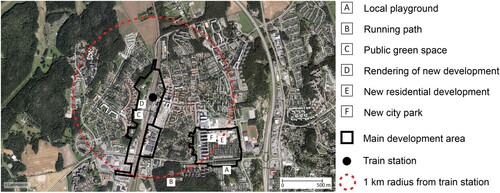

Map 1. Aerial view of Upplands Väsby. Letters indicate the location of photographs in and . Aerial photo from Lantmäteriet.

In June 2018, the municipal council adopted a new comprehensive plan (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018c), which emphasizes the importance of the train station area as a driver of attractiveness and as a place for services and other activities. Here the TOD ambition comes forefront as a central method for urban regeneration. The comprehensive plan mentions and recognizes the importance of a diversified supply of recreation amenities and the need to safeguard recreational areas ‘close to where people live’ (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018c, 21). Careful mapping of existing recreational infrastructures, of which the majority stem from planning in the 1960s and 1970s, is described as a precondition for planning. However, few actual strategies for the future planning of recreational amenities are offered, nor is there any strategy for how to preserve and develop existing amenities.

In municipal strategy documents on transport and mobility (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2013b, Citation2017b), networks of contemporary and planned paths for recreational biking and walking are described and illustrated. However, these networks exclude the urban core, and local scales are not examined. Neither are the locations of recreational facilities in relation to residential areas or transit nodes. A recent municipal sport policy (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2019) shows an ambition for planning for recreation and leisure. As the first comprehensive document on the subject since 1980, the policy indicates a revived interest in strategic thinking regarding sports and leisure. The policy, which was developed by the municipal Department for Culture and Leisure, does not engage with the spatiality of sports and recreation. The absence of spatial concerns in the sport policy and the abstract language of recreational qualities in comprehensive planning indicates a disciplinary divide between land use planning and the governance of the leisure sector - division in stark contrast to the interplay between leisure and urban planning in the modernist era.

4.1.3. TOD materialised

With the ambitions for catering to a population increase from today’s 44 000 inhabitants to 63 000 inhabitants by the year 2040 (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018c), development of new dwellings is of pressing concern. The most recent comprehensive plan adopts the TOD-circle and suggests densification projects within a 1000-metre radius of the train station. A number of projects are ongoing within this radius, with emphasis on two major locations.

In direct connection to the train station, Upplands Väsby is planning for an extensive development under the project name Väsby Entré. From the current land use as green open space and road infrastructure, the area surrounding the train station will be transformed into a dense urban neighbourhood with up to 1 500 new dwellings and 30 000 square metres for offices and commercial use (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018a). The plan’s ambition is to create a mixed, integrated urban area, with a strong identity and strengthened transit node depicted by renderings of landmark buildings designed by internationally esteemed Zaha Hadid Architects as potential features of the future skyline of Upplands Väsby. Recreation is foremost secured by a number of recreational paths whose width or form are not defined, only their routes stretching through green areas and in places merging with the streetscape. Three major parks, and additional smaller spaces for nature and playgrounds, will be located in the area and most new dwellings will have a maximum of 300 meters to the closest park. Throughout the detailed development plan for the project, recreation is consistently described as a passive activity (parks for resting) or as a way to have experiences (of culture, nature and local history). In the assessment of the plans social effects, the municipality takes note of the relatively few neighbourhood parks. ‘Access to larger areas for roaming is relatively good, but for local parks there is a risk that the parks’ area will be relatively limited in relation to the number of users. The wear is likely to be great’ (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2018a, 59). The assessment continues with its appraisal of the positive effects of the project with regards to housing, workplaces and services.

Image 2. New and planned developments in Upplands Väsby; (c) current view of the location for Väsby Entré, (d) rendering of future Väsby Entré (image by Urban Minds, Betty Laurincova in Upplands Väsby kommun Citation2018a), (e) new residential buildings in Fyrklövern adjacent to the new city park (f). Photos by the authors.

West from the station area, one finds an infill project, Fyrklövern. New residential buildings with up to 2 000 dwellings are aligned to a new grid street pattern, inserted within a previously pedestrianised public area (Upplands Väsby Kommun Citation2015, Citation2017a). A public park, a football field and parking lots have been demolished to make space for new developments. However, a new park is already in place, containing a variety of activities from spaces for play to benches for resting and a pond that doubles as storm water basin. The park, described as a "city park" (Upplands Väsby kommun Citation2015) is hoped to attract residents from the whole municipality.

Both of these projects are establishing a denser typology than the existing one, building on both public green space and parking lots. The very form of the new establishments also brings about a new aesthetic, in the form of closed building blocks, fine grid street patterns and fewer open green spaces integrated with residential areas.

5. Discussion

Through this paper we have used recreation, as a matter of land use and mobilities and as a critical lens to examine the contemporary TOD discourse. We have done this via a literature review and a minor case study. The literature review shows how TOD research contains few, or only brief, engagements with recreation as a matter of mobilities or land use. Attention is paid to work commute and proximity between place of residence and place of transit, even if mobilities for and as recreation are acknowledged as being something different from the everyday work commute, and access to recreational facilities is argued as a central aspect of TOD as living environment. Hence, recreation is advocated as a positive quality of TOD areas. However, where recreation should take place is obscured via abstract language about mixed land uses. There appears to exist a dissonance between the conceptual TOD model, where recreation is thought of as an integral part of the livability of TOD, and its spatial implementation where travel routes and residential and commercial land uses are premiered. As Knowles, Ferbrache, and Nikitas (Citation2020) point out, aspirations and reality seem not to go hand in hand. Similar dissonance is also visible in the tension between the aspirations of comprehensive strategic planning in Upplands Väsby and the reality of detailed planning. On a strategic level, recreation is recognised as an important quality in urban environments. However, recreation is largely disregarded in the detailed development plans (compare Petersson-Forsberg Citation2014). The search for urban qualities that drive the development of Upplands Väsby can be interpreted as a policy practice influenced by an ideological idea of the city, reducing urban complexities into elements of physical form (see Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019; Wachsmuth Citation2014). Thus, the exclusion of recreation is built into the very foundation of the development process. We recognise that the importance of recreation is known by the Upplands Väsby Municipality, and recent work with the new sports strategy shows growing ambitions for public health and equal opportunities for recreation. Nonetheless, the general and abstract language of strategic policies leaves local planners the task of negotiating the geography of recreation in each individual development project, and against other powerful interests. TOD thus seems to omit recreation both in theory and in practice, creating a persistent feedback loop. If the model in practice does not sufficiently cater to recreational needs, these needs will be less represented in research on the model – and vice versa.

Finally, the case study shows how a translocal critique of modernist planning facilitates a mistranslation of the Swedish heritage of modernist recreational planning. Public spaces for recreation, as established in the 1960s and 1970s, are not safeguarded and their potentials are rendered invisible in the critique of urban spaciousness. This mistranslation loses sight of both the previous ambitions of recreational planning and its multiscale geography. Instead, an increasingly scattered recreational geography is planned to provide for a rapidly increasing urban population. Not only is recreation silenced in general but the silence also obscures potential local variations and local planning histories relating to recreation (see Robinson Citation2016). Only by making local preconditions known can we reach a deeper understanding of the workings of the TOD model.

6. Conclusions

This paper reveals a blind spot in research on TOD: recreation as a matter of mobilities and land use. As our literature review has shown, the bulk of research on TOD does not take recreation into account.

Furthermore, our study argues for the importance of context-sensitivity when performing a literature review within planning, or any other field in which the local conditions are of key importance. We argue that geographic, societal and spatial particularities need to be acknowledged in order to scrutinise the implementation and effects of TOD and other internationally used planning models.

We situate our understanding and interpretation of the research with a minor case study of Swedish local Swedish. The case illustrates how strategic municipal planning acknowledges recreation as an important feature of a future, sustainable, urban life. Nonetheless, this acknowledgement becomes obscured as the focus is shifted towards building compact neighbourhoods and street connectivity in the detailed development plans. The models and methods for developing a compact city, including the TOD model, do not provide local planners with incentives, nor sufficient tools, for planning for recreation. This strengthens a separation between urbanity and recreation.

The case revealed, for instance, how modernist planning from the 1960s and 1970s in Sweden does not show the same deficiencies as mentioned in the international literature. On the contrary, planning for leisure and recreation was an important part of the agenda, although partly embedded in a car-based mobility. The disregard for modernist planning within the TOD discourse risks neglecting the potentially positive qualities of post-war recreational planning, which could benefit future sustainable urban living.

Finally, the paper shows the need to bring recreation into the TOD model, in both research and practice. However, we have also argued that this absence is not incidental, but is tied to the particular urban ideal within the TOD discourse. Therefore, as a focus on recreation as mobility and land use seems to run counter to the urban ideal that informs TOD, it is not simply a matter of inserting a new theme. Rather, it could inspire, or even require, a revitalisation of the very understanding of the urban that informs the model. Thus, we argue that the question of recreational mobilities provides a critical lens for the current planning discourse. If we add this complex set of mobilities and activities to contemporary urban models, we might see the need for another urban future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Ahmad, Ahmad, and Aliyu (Citation2021), Burke and Woolcock (Citation2009), Zacharias, Zhang, and Nakajima (Citation2011), Langlois et al. (Citation2015), Tayarani et al. (Citation2016), Lang et al. (Citation2020), Lyu, Bertolini, and Pfeffer (Citation2020).

References

- Adelfio, M., U. Navarro Aguiar, C. Fertner, and E. D. C. Brandão. 2021. “Translating ‘New Compactism’, Circulation of Knowledge and Local Mutations: Copenhagen’s Sydhavn as a Case Study.” International Planning Studies 27 (2): 1–23.

- Ahmad, A. M., A. M. Ahmad, and A. A. Aliyu. 2021. “Strategy for Shading Walkable Spaces in the GCC Region.” Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal 14: 312–328.

- Beauregard, R. 2015. Planning Matter: Acting with Things. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bertolini, L. 2017. Planning the Mobile Metropolis: Transport for People, Places and the Planet. London: Palgrave.

- Brown, B. B., and C. M. Werner. 2009. “Before and After a New Light Rail Stop: Resident Attitudes, Travel Behavior, and Obesity.” Journal of the American Planning Association 75: 5–12.

- Burke, M., and G. Woolcock. 2009. “Getting to the Game: Travel to Sports Stadia in the Era of Transit-Oriented Development.” Sport in Society 12 (7): 890–909.

- Calthorpe, P. 1993. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Communities, and the American Dream. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Carr, C. 2014. “Discourse Yes, Implementation Maybe: An Immobility and Paralysis of Sustainable Development Policy.” European Planning Studies 22 (9): 1824–1840.

- Deponte, D., G. Fossa, and A. Gorrini. 2020. “Shaping Space for Ever-Changing Mobility. Covid-19 Lesson Learned from Milan and Its Region.” Tema-Journal of Land Use Mobility and Environment Special issue (Covid-19 vs City-20): 133–149.

- Duquet, B., and C. Brunelle. 2020. “Subcentres as Destinations: Job Decentralization, Polycentricity, and the Sustainability of Commuting Patterns in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1996–2016.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 12: 1–23.

- Ettema, D., and T. Schwanen. 2012. “A Relational Approach to Analysing Leisure Travel.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 173–181.

- Freeman, C., and R. Quigg. 2009. “Commuting Lives: Children’s Mobility and Energy Use.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 52 (3): 393–412.

- Garcia, I., and J. Crookston. 2019. “Connectivity and Usership of Two Types of Multi-Modal Transportation Network: A Regional Trail and a Transit-Oriented Commercial Corridor.” Urban Science 3: 1–12.

- Giulianotti, R., H. Itkonen, A. Nevala, and A. K. Salmikangas. 2019. “Sport and Civil Society in the Nordic Region.” Sport in Society 22 (4): 540–554.

- Glass, C., S. Appiah-Opoku, J. Weber, S. L. Jones, Jr., A. Chan, and J. Oppong. 2020. “Role of Bikeshare Programs in Transit-Oriented Development: Case of Birmingham, Alabama.” Journal of Urban Planning and Development 146 (2): 05020002 .

- Gold, S. M. 1973. Urban Recreation Planning. Philadelphia, PA: LEA & Febiger.

- Hu, H. H., J. Cho, G. Huang, F. Wen, S. Choi, M. Shih, and A. S. Lightstone. 2014. “Neighborhood Environment and Health Behavior in Los Angeles Area.” Transport Policy 33: 40–47.

- Iamtrakul, P., and J. Zhang. 2014. “Measuring Pedestrians’ Satisfaction of Urban Environment Under Transit Oriented Development (TOD): A Case Study of Bangkok Metropolitan, Thailand.” Lowland Technology International 16: 125–134.

- Knowles, R. D. 2012. “Transit Oriented Development in Copenhagen, Denmark: From the Finger Plan to Ørestad.” Journal of Transport Geography 22: 251–261.

- Knowles, R. D., F. Ferbrache, and A. Nikitas. 2020. “Transport’s Historical, Contemporary and Future Role in Shaping Urban Development: Re-Evaluating Transit Oriented Development.” Cities 99: 102607.

- Lang, W., E. C. M. Hui, T. Chen, and X. Li. 2020. “Understanding Livable Dense Urban Form for Social Activities in Transit-Oriented Development Through Human-Scale Measurements.” Habitat International 104: 102238.

- Langlois, M., D. van Lierop, R. A. Wasfi, and A. M. Ei-Geneidy. 2015. “Chasing Sustainability Do New Transit-Oriented Development Residents Adopt More Sustainable Modes of Transportation?” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2531 (1): 83–92.

- Langlois, M., R. A. Wasfi, N. A. Ross, and A. M. El-Geneidy. 2016. “Can Transit-Oriented Developments Help Achieve the Recommended Weekly Level of Physical Activity?” Journal of Transport and Health 3 (2): 181–190.

- Latour, B. 1999. Pandoras Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Lowe, M. 2018. “Embedding Health Considerations in Urban Planning.” Planning Theory and Practice 19 (4): 623–627.

- Lu, Y., Z. Gou, Y. Xiao, C. Sarkar, and J. Zacharias. 2018. “Do Transit-Oriented Developments (TODs) and Established Urban Neighborhoods Have Similar Walking Levels in Hong Kong?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (3): 555.

- Lyu, G., L. Bertolini, and K. Pfeffer. 2020. “Is Labour Productivity Higher in Transit Oriented Development Areas? A Study of Beijing.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 111 (4): 652–670.

- MacLeod, G. 2013. “New Urbanism/Smart Growth in the Scottish Highlands: Mobile Policies and Post-Politics in Local Development Planning.” Urban Studies 50: 2196–2221.

- Mamdoohi, A. R., and A. Janjani. 2016. “Modeling Metro Users’ Travel Behavior in Tehran: Frequency of Use.” Tema-Journal of Land Use Mobility and Environment Special issue (1): 47–58.

- McCann, E., and K. Ward. 2010. “Relationality/Territoriality: Toward a Conceptualization of Cities in the World.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 41: 175–184.

- McCann, E., and K. Ward. (Eds.). 2011. Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McFarlane, C. 2010. “The Comparative City: Knowledge, Learning, Urbanism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34 (4): 725–742.

- McFarlane, C. 2015. “The Geographies of Urban Density: Topology, Politics and the City.” Progress in Human Geography 40: 629–648.

- Meng, L., R. Y. M. Li, M. A. P. Taylor, and D. Scrafton. 2021. “Residents’ Choices and Preferences Regarding Transit-Oriented Housing.” Australian Planner 57: 85–99.

- Meyer, C. B. 2001. “A Case in Case Study Methodology.” Field Methods 13 (4): 329–352.

- Moen, O. 1991. Idrottsanläggningar och idrottens rumsliga utveckling i svenskt stadsbyggande under 1900-talet: med exempel från Borås och Uppsala. Göteborg: Handelshögskolan, Kulturgeografiska institutionen.

- Morency, P., C. Plante, A. S. Dubé, S. Goudreau, C. Morency, P. L. Bourbonnais, N. Eluru, et al. 2020. “The Potential Impacts of Urban and Transit Planning Scenarios for 2031 on Car Use and Active Transportation in a Metropolitan Area.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (14): 1–15.

- Newman, W. G., and J. R. Kenworthy. 1996. “The Land Use – Transport Connection: An Overview.” Land Use Policy 13: 1–22.

- Nielsen, H. N., S. B. Aaen, I. Lyhne, and M. Cashmore. 2019. “Confronting Institutional Boundaries to Public Participation: A Case of the Danish Energy Sector.” European Planning Studies 27 (4): 722–738.

- Østmo, L., and J. Law. 2018. “Mis/Translation, Colonialism, and Environmental Conflict.” Environmental Humanities 10 (2): 349–369.

- Papa, E., and L. Bertolini. 2015. “Accessibility and Transit-Oriented Development in European Metropolitan Areas.” Journal of Transport Geography 47: 70–83.

- Park, K., D. A. Choi, G. Tian, and R. Ewing. 2019. “Not Parking Lots but Parks: A Joint Association of Parks and Transit Stations with Travel Behavior.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (4): 547.

- Petersson-Forsberg, L. 2014. “Swedish Spatial Planning: A Blunt Instrument for the Protection of Outdoor Recreation.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 5-6: 37–47.

- Pries, J., and M. Qviström. 2021. “The Patchwork Planning of a Welfare Landscape: Reappraising the Role of Leisure Planning in the Swedish Welfare State.” Planning Perspectives 36 (5): 1–26.

- Qviström, M. 2015. “Putting Accessibility in Place: A Relational Reading of Accessibility in Policies for Transit-Oriented Development.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 58: 166–173.

- Qviström, M., J. Bengtsson, and V. Vicenzotti. 2016. “Part- Time Amenity Migrants: Revealing the Importance of Second Homes for Senior Residents in a Transit-Oriented Development.” Land Use Policy 56: 169–178.

- Qviström, M., N. Luka, and G. De Block. 2019. “Beyond Circular Thinking: Geographies of Transit-Oriented Development.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43: 786–793.

- Rehling, D. 2017. “Amager Fælled: Et naturområde truet af løftebrud [Amager Common: A nature area threatened with a breach of promise].” In Danmarks Naturfredningsforening, edited by D. Naturfredningsforening. Danmarks Naturfredningsforening. https://www.dn.dk/nyheder/amager-faelled-et-naturomrade-truet-af-loftebrud/.

- Robinson, J. 2016. “Comparative Urbanism: New Geographies and Cultures of Theorizing the Urban.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40: 187–199.

- Sallis, J. F., R. B. Cervero, W. Ascher, K. A. Henderson, M. K. Kraft, and J. Kerr. 2006. “An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities.” Annual Review of Public Health 27: 297–322.

- Schmitt, P., and L. Smas. 2019. “Shifting Political Conditions for Spatial Planning in the Nordic Countries.” In Politics and Conflict in Governance and Planning: Theory and Practice, edited by A. Eraydin and K. Frey, 133–150. New York: Routledge.

- Sharifi, A. 2016. “From Garden City to Eco-Urbanism: The Quest for Sustainable Neighborhood Development.” Sustainable Cities and Society 20: 1–16.

- Sreedhara, M., K. V. Goins, C. Frisard, M. C. Rosal, and S. C. Lemon. 2019. “Stepping Up Active Transportation in Community Health Improvement Plans: Findings from a National Probability Survey of Local Health Departments.” Journal of Physical Activity and Health 16 (9): 772–779.

- Star, S. L., and G. C. Bowker. 2007. “Enacting Silence: Residual Categories as a Challenge for Ethics, Information Systems, and Communication.” Ethics and Information Technology 9: 273–280.

- Statens Planverk. 1977. Bostadsbestämmelser: Information om nybyggnadsbestämmelser för bostaden och grannskapet.

- Tan, X., X. Zhu, Q. Li, L. Li, and J. Chen. 2020. “Tidal Phenomenon of the Dockless Bike-Sharing System and Its Causes: The Case of Beijing.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 16 (4): 1–18.

- Tayarani, M., A. Poorfakhraei, R. Nadafianshahamabadi, and G. M. Rowangould. 2016. “Evaluating Unintended Outcomes of Regional Smart-Growth Strategies: Environmental Justice and Public Health Concerns.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 49: 280–290.

- Thomas, R., D. Pojani, S. Lenferink, L. Bertolini, D. Stead, and E. van der Krabben. 2018. “Is Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) an Internationally Transferable Policy Concept?” Regional Studies 52 (9): 1201–1213.

- Thornton, R. L. J., A. Greiner, C. M. Fichtenberg, B. J. Feingold, J. M. Ellen, and J. M. Jennings. 2013. “Achieving a Healthy Zoning Policy in Baltimore: Results of a Health Impact Assessment of the TransForm Baltimore Zoning Code Rewrite.” Public Health Reports 128 (6_suppl3): 87–103.

- Thrun, E., J. Leider, and J. F. Chriqui. 2016. “Exploring the Cross-Sectional Association Between Transit-Oriented Development Zoning and Active Travel and Transit Usage in the United States, 2010–2014.” Frontiers in Public Health 4: 1–8.

- Transport Analysis. 2017. RVU Sverige 2015–2016 – Den nationella resvaneundersökningen. https://www.trafa.se/kommunikationsvanor/RVU-Sverige/.

- Tunström, M. 2007. “The Vital City: Constructions and Meanings in the Contemporary Swedish Planning Discourse.” Town Planning Review 78: 681–698.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 1976. Fritidsplan 1976–1980.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2005. Framtidens Upplands Väsby – “Den moderna småstaden”. Strategisk kommunplan 2005–2020.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2013a. Stadsmässighet – definition för Upplands Väsby kommun.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2013b. Trafikplan.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2015. Detaljplan för Fyrklövern 1-allmän platsmark i Upplands Väsby kommun. Planbeskrivning.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2017a. Detaljplan för Norra Ekebo inom Fyrklövern, Upplands Väsby kommun.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2017b. Upplands Väsby Trafikstrategi. Samrådsversion.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2018a. Detaljplan för Östra Runby med Väsby stationsområde.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2018b. Stadsmässighetsdefinition för Upplands Väsby kommun.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2018c. Väsby Stad 2040. Ny översiktsplan för Upplands Väsby kommun.

- Upplands Väsby kommun. 2019. Aktiv hela livet – Idrottsstrategisk plan för Upplands Väsby kommun.

- Vicenzotti, V., and M. Qviström. 2017. “Zwischenstadt as a Travelling Concept: Towards a Critical Discussion on Mobile Ideas in Transnational Planning Discourses on Urban Sprawl.” European Planning Studies 26: 115–132.

- Wachsmuth, D. 2014. “City as Ideology: Reconciling the Explosion of the City Form With the Tenacity of the City Concept.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32: 75–90.

- Wood, A. 2016. “Tracing Policy Movements: Methods for Studying Learning and Policy Circulation.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (2): 391–406.

- Yang, Y., B. A. Langellier, I. Stankov, J. Purtle, K. L. Nelson, and A. V. D. Roux. 2019. “Examining the Possible Impact of Daily Transport on Depression Among Older Adults Using an Agent-Based Model.” Aging & Mental Health 23 (6): 743–751.

- Zacharias, J., T. Zhang, and N. Nakajima. 2011. “Tokyo Station City: The Railway Station as Urban Place.” Urban Design International 16: 242–251.