?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

While extensive research has been carried out on thriving at work enablers, scarce attention has been devoted to the factors that may obstruct thriving. This daily diary study builds on the age-based metastereotype activation model to fill this research gap. According to this model, employees may challenge negative age-based metastereotypes (NABM) or feel threatened by them. Thus, this study examines the role of age-based stereotype threat (ABST) in the thriving experience – a combined sense of learning and vitality – and analyzes whether perceived age similarity moderates the threat reaction to NABM. Data were collected over the course of five consecutive workdays from 82 white-collar employees, most of whom were working in the services sector. The findings indicate that NABM have next-day consequences. Specifically, NABM directly obstruct next-day vitality levels and indirectly overall employee thriving and learning through ABST, highlighting thriving dimensions’ distinctiveness. Additionally, moderation analyses showed a “safety‑in‑numbers-effect” of perceived age similarity. As existing accounts fail to specify the time cycle of NABM consequences in the workplace, this study contributes to the ageism literature by advancing next-day effects of NABM on thriving.

Introduction

Thriving at work refers to a positive psychological state of personal growth which stems from the joint sense of vitality and learning in the workplace (Spreitzer et al., Citation2012). Empirical work across several industries has shown that thriving is positively linked with employees’ health, engagement, and with performance at the individual and unit levels (Kleine et al., Citation2019; Walumbwa et al., Citation2018). Considering that thriving promotes personal growth at work (Spreitzer et al., Citation2012) and that both task performance and initiative aspects of performance like innovation are positively related to thriving (Walumbwa et al., Citation2018), a better understanding of the circumstances that foster thriving at work is key for employees’ wellbeing and organizational competitiveness.

Most studies within the socially embedded framework of thriving at work (Spreitzer et al., Citation2005) emphasize the role of individual, relational, and contextual enablers of the thriving experience (Moore et al., Citation2021; Niessen et al., Citation2012). However, far too little attention has been paid to the factors that may obstruct thriving (Prem et al., Citation2017). For example, while the positive effect on thriving of relational enablers like heedful interactions is well established (Niessen et al., Citation2012), we still have not attained an adequate understanding of the role played by job stressors in shaping the quality of relationships with co-workers. Given the current demographic trends, this study contends that ageism is likely to emerge as a relevant job stressor in today’s workplaces. Indeed, as workforces’ age diversity increases in most industrialized countries (Fasbender & Drury, Citation2021), ethnocentric and discriminatory behaviours between age groups as they compete for scarce resources like employment are to be expected (Guillaume et al., Citation2014). Thus, with age becoming one of the most salient social categories at work, a comprehensive understanding of how workplace ageism shapes thriving at work is clearly warranted.

This study draws upon the age-based metastereotype activation model (Finkelstein et al., Citation2015) to analyse the link between negative age-based metastereotypes (NABM), i.e., employees’ negative beliefs concerning stereotypes other age groups hold about one’s ingroup (Finkelstein et al., Citation2013) and employees’ thriving. Building on studies that showed detrimental effects of NABM on employees’ engagement (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019; von Hippel et al., Citation2019), and in line with the directionality logic implied by affective events theory according to which moods and emotions are the linking mechanisms between triggers and their resulting behaviours (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996), we posit that age-based stereotype threat (ABST), a negative emotional reaction to stereotypes about one’s group (Steele & Aronson, Citation1995), is the linking mechanism between NABM and thriving. Importantly, we position these processes as sequential and advance a next-day causal cycle in which NAMB trigger the concern that characterizes ABST in a lagged way. As existing accounts fail to specify the time cycle of NABM consequences in the workplace, advancing the temporal effects of NABM on employees’ thriving is a valuable endeavour.

Considering that ruminative thoughts taking place at the end of the workday may intensify the age identity concerns prompted by NABM early that day (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Citation2008; Wang et al., Citation2013), we anticipate next-day heightened levels of ABST which subsequently impact thriving at work negatively on that same day. Although other time cycles have been examined (e.g., same-day effects, see Finkelstein et al., Citation2019), we draw on empirical work that showed lagged next-day effects of goal failure in employees (Wang et al., Citation2013) to contend that NABM may inhibit employees’ strive for a positive age identity and, as a result, the effects of this self-related goal failure evolve in a next-day time frame.

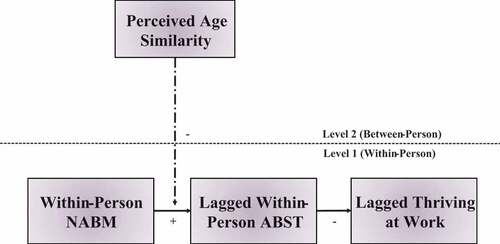

In sum, our model () aims to answer the calls for theory improvement (Mitchell & James, Citation2001; Sonnentag, Citation2012) through the specification of when do within-person NABM and ABST effects on thriving occur. By capturing the within-person dynamics in employees’ thriving triggered by NABM, this study overcomes the limitations of cross-sectional between-person studies about thriving (e.g., Oliveira, Citation2021) and improves the temporal precision of the workplace ageism-thriving relationship (McCormick et al., Citation2020). Besides time-related contributions, our model also answers to the calls of thriving scholars for more theoretical refinement regarding thriving dimensionality through the examination of ageism effects on learning and vitality separately (Kleine et al., Citation2019). This is particularly relevant in the light of recent research that showed that despite being negatively related to overall thriving throughout the working life, NABM are not associated with younger and middle-aged workers’ learning nor with older workers’ vitality levels (Oliveira, Citation2021).

Considering the harmful effects of NABM on thriving proposed in our model, the second aim of the current study is to examine the role played by perceived team age compositionFootnote1 in the relationship between NABM and ABST. Specifically, our rationale follows one of the basic tenets of the similarity-attraction paradigm that suggests that employees are attracted to and seek others who are like themselves (Byrne, Citation1971). Relatedly, findings from the age diversity literature have linked objective employee age underrepresentation with ABST (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2017) and showed counterproductive effects of objective age distance on inter-age interactions (De Meulenaere & Kunze, Citation2021). Since perceived age similarity adds explanatory value to work phenomena beyond objective similarity (Van der Heijden, Citation2018), we suggest that perceived age similarity within the team shields employees from negative reactions to NABM.

By bringing together the workplace ageism and thriving at work literatures, and doing so through the consideration of individual, relational, and contextual antecedents of the thriving experience, this study contributes to the development of a comprehensive understanding of how ageism shapes employees’ personal growth.

Thriving at work

According to the social embeddedness model of thriving at work (Spreitzer et al., Citation2005), employees thrive at work through the joint experience of learning (e.g., continuously developing and applying knowledge) and vitality (e.g., feeling energized and passionate). Herewith, employees thrive whenever the cognitive component of psychological growth (learning) and the affective component (vitality) are both high. In other words, employees who thrive perceive themselves as continuously improving at work while also feeling passionate about one’s job. Thriving at work differs from related constructs such as positive affect, subjective well-being, or work engagement as it highlights the positive experience of personal growth originated from the joint sense of learning and vitality. Additionally, in contrast to subjective well-being, thriving combines hedonic and eudaimonic elements, and exhibits incremental predictive validity above and beyond positive effect and work engagement for task performance (Kleine et al., Citation2019). Three agentic work behaviours support thriving at work: task focus, i.e., a high degree of effort to meet job demands, exploration of new ways of working, and heedful relating which refers to high-quality interactions with others at work (Spreitzer et al., Citation2005). Given that thriving has been associated positively with engagement and performance, and negatively with turnover intentions (Kleine et al., Citation2019; Walumbwa et al., Citation2018), an important starting point for continued research is the study of thriving conditioning factors (Prem et al., Citation2017). In contrast to the extensive research conducted on thriving enablers (e.g., Moore et al., Citation2021; Niessen et al., Citation2012), less attention has been directed to the role played by job stressors on the thriving experience (Prem et al., Citation2017). Indeed, we already know that high-quality relationships with co-workers, co-worker support, colleague strengths recognition, and feeling treated with respect contribute to heightened thriving levels (Moore et al., Citation2021; Niessen et al., Citation2012; Porath et al., Citation2012). In this study, we focus on the deterrent effect ageism may have on thriving. Specifically, we suggest that workplace ageism inhibits simultaneously the desire for a positive age identity (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979), and heedful relating, one of the required agentic behaviours for employees’ thriving (Spreitzer et al., Citation2005).

Ageism influences thriving at work

Considering that relational and contextual workplace characteristics influence learning and vitality (Spreitzer et al., Citation2005), employees’ thriving may be at risk due to workplace ageism. Indeed, a vast array of negative attitudinal and behavioural consequences of workplace ageism has been recently reported (e.g., Finkelstein et al., Citation2019; Oliveira, Citation2021).

Although the seminal conceptualizations of ageism referred to attitudes and discriminatory practices mostly against older people (e.g., Butler, Citation1969), currently, it is acknowledged that all age groups may be targeted by ageism (Lamont et al., Citation2021). Alongside age discrimination, ageism involves two other entangled dimensions: prejudices, corresponding to the affective dimension, and a cognitive dimension embodied by stereotypes. Underlying each dimension is the undervaluation of individuals based on their age group membership. Notwithstanding widespread legal protection against age discrimination in the labour market, workplace ageism seems to endure (European Commission, Citation2019; Lamont et al., Citation2021).

In the context of increasing age diversity in most industrialized workplaces (Fasbender & Drury, Citation2021), understanding workplace cross-age interactions should be at the top of the researchers’ agendas. Particularly important for that endeavour is the notion of age metastereotypes, here understood as stereotypical beliefs other age groups hold about one’s ingroup (Finkelstein et al., Citation2013). Although younger, middle-aged, and older workers positive metastereotypes were reported (Finkelstein et al., Citation2013; Oliveira, Citation2021), “most of the time people expected other groups’ perceptions to be more negative than they were” (Finkelstein et al., Citation2013, p. 654). Indeed, previous studies have shown that NABM may hamper the quality of workplace intergenerational dynamics (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019; von Hippel et al., Citation2019), and lead to negative work attitudes like work disengagement and organizational disidentification (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2018). Taken together, these findings suggest that thriving at work may be blocked as NABM impair intergroup relations. Two main reasons may explain how NABM shape the thriving experience. On the one hand, negative views about one’s ingroup may decrease the enthusiasm and energy levels associated with vitality at work. On the other hand, the quality of cross-age interactions may be compromised since NABM make co-worker cooperation and support less likely. Hence, with lower-quality opportunities for acquiring and applying knowledge through cross-age interactions, learning at work may become more difficult. Since co-workers are one key referent in how employees make sense of their work environment (Chiaburu & Harrison, Citation2008), NABM may become an important job stressor. Indeed, heedful relating with co-workers becomes more challenging in organizations in which NABM prevail due to the increased likelihood of avoidance or conflict behaviours in these contexts (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, in ageist organizational settings, employee’s need for a positive age identity is not met (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979), and as a result, employees experience a self-related goal failure that may inhibit their pursuit for self-development (Searle & Auton, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2013). Herewith, we contend that NABM may be an important job stressor in todays’ age-diverse workplaces in the sense that they contribute to employees’ goal failure in developing a positive age identity (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979), which in turn depletes their vitality. Relatedly, NBAM may deteriorate the quality of interactions with co-workers of other age groups. Considering that heedful relating is among the agentic work behaviours suggested to foster thriving at work, particularly via learning activities (Spreitzer et al. (Citation2005), it seems reasonable to assume that NABM negatively influence the relational resources needed for employees to thrive. Taken together, these arguments suggest a negative link between NABM and thriving at work. The following hypothesis is, hence, formulated:

Hypothesis 1:

Daily within-person NABM is negatively related to next-day (a) lagged overall thriving, (b) learning, and (c) vitality.

According to the age-based metastereotype activation model, the fundamental way age-based metastereotypes shape the quality of cross-age interpersonal interactions and attitudes at work is via emotions like threat (Finkelstein et al., Citation2015), and several studies support this claim (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019; Oliveira, Citation2021; von Hippel et al., Citation2019). Even though employees may interpret NABM simultaneously as challenges and as threats (Searle & Auton, Citation2015), the larger magnitude of ABST indirect effects vis-à-vis challenge effects on thriving at work (Oliveira, Citation2021) has positioned the NABM-ABST link at the core of researchers’ attention (e.g., Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2018). Herewith, NABM have been widely considered a precursor to the worry of being at risk of confirming a negative age stereotype about one’s group that characterizes ABST (Steele & Aronson, Citation1995) and to ABST consequences. While the NABMABST link has been extensively scrutinized, few research has explored time considerations about this relationship. With that in mind, this study draws upon cognitive theories of rumination to posit a NABM next-day effect on ABST. Specifically, we contend that employee rumination, that is, conscious thinking about goal pursuit failure during a prolonged period (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Citation2008) may explain how and why NABM obstruct thriving in a next-day fashion (cf. Hypothesis 1). Failure in obtaining a positive age identity due to NABM may not lead to immediate rumination. Perhaps ruminative thoughts about failure in obtaining a positive view of oneself derived from not being respected and valued by co-workers do not develop instantaneously due to daily tasks and work responsibilities or even due to coping strategies like distraction (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Citation2008). Under these circumstances, employees’ rumination about the self-related goal failure is likely to be more intense after the end of the workday paving the way for a prolonged impact of daily stressors (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019). Therefore, on days in which employees experience higher levels of NABM, they are more likely to ruminate at the end of the workday, and subsequently experience more ABST in the following workday (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2009). This claim is in line with previous research on daily stress and coping that showed that rumination is the bridging cognitive mechanism between daily customer mistreatment and its lagged manifestation on employees’ next-day negative emotion (Wang et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, out-of-work recovery strategies like psychological detachment from work may bring affective benefits after a negative work event (Sonnentag & Niessen, Citation2020). Therefore, rather than a heightened NABM-ABST relationship via rumination, it is also plausible that employees may recover from NABM negative effects through psychological detachment from work at the end of the workday. While acknowledging “psychological detachment from work during non-work time as an important feature of a successful recovery process” (Sonnentag & Niessen, Citation2020, p. 1), we contend that rumination is more likely than detachment particularly because NABM trigger a negative interpersonal event, and this type of events is more strongly associated with negative emotions like anger than task-related events (Ohly & Schmitt, Citation2015). Additionally, in their recent daily diary study on age metastereotype effects, Finkelstein et al. (Citation2019) found cross-day associations between older employees’ NABM and next-day challenge, one of the emotional reactions to NABM proposed by the age-based metastereotype activation model. In sum, we propose that, similarly to customer mistreatment, NABM signal employees’ unsuccessfulness in achieving a positive age identity. This self-related goal failure then induces the evening ruminative thoughts behind NABM's emotional next-day effects. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2:

Daily within-person NABM is positively related to next-day lagged within-person ABST.

Connecting NABM with thriving at work

Consistent with the directionality logic of the age-based metastereotype activation model, affective events theory proposes moods and emotions as linking mechanisms between triggers and the attitudes/behaviours that result from them (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996). With that in mind, we contend that a better understanding of the employees’ thriving at work experience could be obtained through the analysis of the mediation role played by ABST in the relationship between NABM and thriving. Although time considerations are absent from the age-based metastereotype activation model and from the affective events theory, the specification of time lags in models involving mediation is critical (Mitchell & James, Citation2001). However, most existing accounts on the ABST role in the workplace have been cross-sectional (e.g., Oliveira, Citation2021), and it was only recently that researchers began to use diary or weekly designs to address time considerations regarding the ABST experience at work. For example, von Hippel et al. (Citation2019) captured ABST negative repercussions on older workers’ job engagement, satisfaction, commitment, and intentions to quit in a weekly fashion. In another study, Finkelstein et al. (Citation2019) using a daily diary design linked ABST with conflict and avoidance behaviours, and with engagement. Reconciling these findings with our rationale for hypotheses 1 and 2, we propose that the NABM and thriving at work relationship is mediated by ABST in a next-day fashion. Following this reasoning, hypothesis 3 is formulated:

Hypothesis 3.

There are negative indirect effects of daily within-person NABM on next-day (a) lagged overall thriving, (b) lagged learning, and (c) lagged vitality through lagged within-person ABST.

Boundary condition: the role of perceived age similarity

From the onset, the stereotype threat literature has emphasized that “stereotype threat is best thought of as a predicament of a person in a situation” (Steele et al., Citation2002, p. 397). So far, however, our understanding of the contexts and contingencies that shape the ABST experience is still insufficient (Lamont et al., Citation2021). Considering that current societal challenges (e.g., increasing age-diverse workforces) may heighten workplace ageism and that individual beliefs like NABM may obstruct thriving through ABST, we contend that greater attention needs to be directed towards the boundary conditions of the NABM-ABST link. Hence, this study proposes that perceived team age composition may shape the relationship between NABM and ABST. The reason thereto is twofold: on the one hand, employees are attracted to, affiliate, and seek others who are like themselves because likeness makes it easier to understand and predict others’ behaviour (Byrne, Citation1971). When group heterogeneity in the workplace is high, dissimilarity may raise the likelihood of social identity threats and subsequent ethnocentric views between groups, particularly in underrepresented group members (Steele et al., Citation2002). Several empirical findings from the age diversity literature support this assumption. Indeed, objective age underrepresentation was positively associated with ABST (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2017), and counterproductive effects of objective age distance on inter-age interactions were found (De Meulenaere & Kunze, Citation2021). Moreover, underrepresentation makes it more difficult for stigmatized individuals to seek positive social support which might block the negative reactions triggered by NABM (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2009). In this vein, age underrepresentation in the team may signal employees that they are undervalued organizational members, and as a result, members of these stigmatized groups may feel concerned about their age identity (Steele et al., Citation2002). On the other hand, when NABM are common, employees may find it hard to gain feelings of relatedness with co-workers from other age groups which are important to stimulate employee thriving (Moore et al., Citation2021). This is even more important in the team context, as members of one’s team are one of the most proximal sources of employees’ sense making (Chiaburu & Harrison, Citation2008). Since ABST is a threat in the air (Steele et al., Citation2002) and thriving is a socially embedded process (Spreitzer et al., Citation2005), it seems reasonable to assume that vulnerability to ABST may be heightened by underrepresentation within the team context. Taken together, these arguments suggest that age underrepresentation within the team is a situational cue that may exacerbate the NABM-ABST link. Conversely, when age differences in the workplace are not cued by underrepresentation and, hence, age is less salient (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2017), employees will likely experience age identity safety which in turn may lessen the feelings of fear triggered by NABM. Following calls for more research that goes beyond objective age similarity outcomes (Van der Heijden, Citation2018), this study suggests that perceived age similarity shields employees from negative reactions to NABM. Building on the foregoing arguments, we thus hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4.

Perceived Age Similarity moderates the positive within-person relationship between within-person NABM and lagged within-person ABST. Specifically, the relationship is weaker (stronger) when levels of Perceived Age Similarity are higher (lower).

Method

Sample and procedure

This study followed a daily diary design, with participants completing a baseline survey prior to the daily diary stage of the research for collection of demographics and other age-related measurements like perceived age similarity and chronological age. Daily diary data were collected with an interval contingent design (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019) using the SEMA3 app over five consecutive workdays. The daily measurement of all focal variables adds time precision to our research model, thus surpassing limitations associated, for example, with weekly aggregated data on ABST (von Hippel et al., Citation2019). Even if employees experience ABST only sporadically, daily data collection is also in the sweet spot to reduce the concerns associated with retrospective bias, particularly those related to the validity of responses in within-person research (McCormick et al., Citation2020).

Given that daily diary studies can be burdensome to participants, online meetings were held with participants for clarification purposes and to help them get acquainted with the app. Without prejudice to these explanation procedures, we acknowledge that our research design and data collection procedures might have influenced the overall demographics of our sample. For instance, the likelihood of getting the ideal conditions for filling in the surveys is probably higher in the services sector than in the manufacturing industry. Indeed, some of the recruited participants working in the manufacturing sector reported diverse types of impediments to their participation in the daily diary stage of the study. The most mentioned barriers to participation were the prohibition of the use of personal mobile phones during working hours, the lack of proper internet coverage on the shop floor, and the difficulty to articulate the work schedule with the data collection timeline.

The baseline survey was returned by 114 of the 129 individuals initially recruited, and the daily diary stage was fully completed by 82 participants amounting to an overall response rate of 64%. Since our focal variables are idiosyncratic constructs, single-source individual-level data were collected. Our final sample comprised workers aged 18–64 years old (43 males, 39 females). Considering the additional constraints expressed by manufacturing workers to participate in the daily diary stage of the study, most participants in the final sample worked in the services sector, about one-third was telecommuting fully or partially due to the COVID-19 crisis, and 21% held a supervisor role. There was a considerable diversity of job types in our sample with the most common job roles being retail merchandiser, customer service manager, sales manager, financial consultant, IT analyst, account manager, and business analyst. Most respondents were in a relationship (62 out of 82), and 65% have attended higher education. The average age was 37 years old (SD = 10.30), and the average organizational tenure was 10 years (SD = 8.72).

All the scales were translated into Portuguese by translation experts by means of a translation/back-translation procedure. Most participants were recruited through the researcher's professional and personal networks in face-to-face meetings or through the Internet (email, social networks like LinkedIn, and online meetings), were informed of the aim of the study, and guaranteed anonymity from the onset.

Measures

Unless stated otherwise, participants answered on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

NABM. Following Finkelstein et al. (Citation2019) recommendation to study specific metastereotypes, a two-item index was crafted for three age groups. In this way, this study examined age-based metastereotype contents like the younger workers’ unreliability, the middle-aged workers’ unavailability, and the older workers’ slowness. For the sake of clarity, participants were informed about age group boundaries from the onset. Moreover, to capture this index in a daily fashion, items were structured as follows: e.g., “Today, I have the impression my [younger/middle-aged] co-workers feel that I am slower because of my age”. With abbreviated measures becoming increasingly common in intensive data collection efforts like daily diary studies (Matthews et al., Citation2022), concerns about the validity and reliability of those measures have been raised. Since this study is particularly interested in within-person relationships, instead of reporting test–retest reliabilities, evidence of within-person variability should be reported (Gabriel et al., Citation2019). Hence, we computed the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC1) for the NABM measure and obtained an ICC1 value of .78.

ABST. Workers rated their experience of threat with a three-item scale developed by Shapiro (Citation2011). To frame the threat reaction in daily terms, the original scale was adapted. An example item is “Today, I am concerned that my actions might poorly represent workers of my age group”. Because this study’s focal point is within-person relationships, we tested whether within-person fluctuations on the different measures co-vary following the recommendations of Geldhof et al. (Citation2014). Hence, we used the multilevel confirmatory factor analysis approach to estimate the α coefficients for our latent factors at the within-person level (Gabriel et al., Citation2019). The ABST scale demonstrated a substantial within-person reliability α = 0.90. Both NAMB and ABST were measured in the beginning of the afternoon, between 1 pm and 2 pm.

Thriving at work. Following Porath et al. (Citation2012), overall thriving was assessed with 10 items, five for learning (one reversed) and five for vitality (one reversed). Thriving was measured at the end of each workday, and participants were asked to report their average afternoon thriving levels. An example item of the learning component is as follows: “I continue to learn more and more as time goes by”, and one example of the vitality component is as follows: “I feel alive and vital”. Given that reporting results for the learning and vitality sub-dimensions separately may shed important light on thriving antecedents (Kleine et al., Citation2019), we examined the reliability of three thriving scales. These scales showed fair to moderate internal consistency (Nezlek, Citation2017). Specifically, the overall thriving scale showed a reliability of α = 0.61, and the learning and vitality scales showed reliabilities of α = 0.69 and α = 0.53, respectively. Although these values may seem relatively low vis-à-vis traditional reliability criteria, Nezlek (Citation2017, p. 154) has suggested “more relaxed standards than one might apply for trait measures” for the evaluation of day-level within-person scales’ reliability. Considering that thriving is a work-related psychological state (Spreitzer et al., Citation2012) with substantial variation from day-to-day at the within‐person level (Niessen et al., Citation2012), we consider that the lower reliability of the vitality dimension does not compromise the validity of our results. Indeed, in their diary study on thriving, Niessen et al. (Citation2012) had already found a much greater day-level variation in vitality than in learning.

Age. Participants’ chronological age was self-reported and collected in the baseline survey.

Perceived age similarity. Perceptions about team age similarity were measured using a single-item measure “Most of my teammates are from my age group”. Responses were made on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Single-item measures have already been used in previous studies on similarity (e.g., Berger & Heath, Citation2008) and age diversity (e.g., Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2017), and a recent large-scale evidence-based study showed that numerous constructs in the organizational psychology and management scholarships can be validly assessed with a single item (Matthews et al., Citation2022). Moreover, this measure captures a conceptually narrow and unidimensional construct (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Citation2009). Taken together, these arguments suggest the appropriateness of this single-item measure to operationalize the construct of perceived age similarity.

Covariates. Chronological age and organizational tenure were included as control variables since previous research showed that these variables may be related to thriving (Kleine et al., Citation2019).

Statistical analyses

To establish the factor structure of our measures of ABST and thriving, multilevel confirmatory factor analyses (MCFAs) were conducted with the “lavaan” package (Rosseel, Citation2012) for R. Given that NABM, ABST, and thriving at work observations were nested within-person, we used mixed-effects models for our analyses. We used the “lme4” package (Bates et al., Citation2015) for R to model within-person relationships and the cross-level two-way interaction of perceived age similarity and NABM on ABST. In addition, the “mediation” package (Tingley et al., Citation2014) was used to estimate the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) intervals with 10,000 bootstrap resamples of the mediation effects of our 1-1-1 mediation model (Zhang et al., Citation2009). Because we were interested in the mediation effects at the within-person level, NABM and ABST were person-mean centred. This centring decision allowed us to separate observations into orthogonal between-person components and on within-person components (Bolger & Laurenceau, Citation2013), and to focus the mediation analyses on the latter. Conversely, level-two perceived age similarity and chronological age were grand-mean centred to test the hypothesized cross-level moderation.

In addition to these centring decisions, we modelled a lagged effects model () to capture how ageism in the workplace unfolds at the within-person level. With that in mind, we modelled, for any time point (t), the effects of NABM on both next-day ABST (t + 1, afternoon) and thriving (t + 1, end of the workday). Additionally, we also modelled the effects of ABST on thriving on the same day (t + 1) and controlled for the preceding levels of each variable. As our model hypothesized relationships between NABM (measured in Day t afternoon survey), ABST (measured in Day t + 1 afternoon survey), and thriving at the end of the workday (measured in Day t + 1 end of the workday survey), the maximum number of useful daily observations provided by each participant was eight (surveys from Days 1–4 were matched up with next-day surveys from Days 2–5). Thus, the lagging procedure makes the total number of level-one observations N = 328.

Results

Descriptive statistics

presents descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the within-person and between-person variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and within- and between-person correlations.

Considering that standard model fit approaches evaluate the goodness of fit of any given model across all levels simultaneously, these methods are not the most suited to assess model fit with multilevel data (Hox et al., Citation2017; Ryu, Citation2014). Therefore, we used the level-specific approach suggested by Ryu (Citation2014) which allows researchers to appropriately obtain statistics and fit indices for the within- and between-person levels separately. Given our focus on within-person relationships, we modelled several partially saturated models in which the level-2 model was saturated to assess the model fit at level 1 (the within-person part of our model), having also saturated the between-person model in the baseline model. In line with the level-specific approach for model fit evaluation suggested by Ryu (Citation2014), we then calculated all fit indices relative to the baseline model.

Four MCFA models were specified (): Model 1, a one-factor model, combining all items from all measures; Model 2, a two-factor model with ABST and all items from the thriving measure combined; Model 3, a three-factor model with ABST and the two thriving sub-dimensions uncorrelated; and Model 4, a two-factor model with an ABST factor and a second-order factor thriving differentiating both sub-dimensions of thriving (i.e., learning and vitality). We found that Model 4 fits the data better than any of the other models (Δχ2s ≥6.3, dfs ≤2, ΔRMSEAs ≥.01, ΔSRMRs ≥.01). Therefore, the key variables of our study were distinct from one another.

Table 2. Summary of MCFA model fit indices at the within-person level.

Hypotheses testing

To test our hypotheses, we firstly considered an unconditional model (intercept only model) to establish the amount of within-person variability in overall thriving and its sub-dimensions. The intraclass correlations (ICCs) estimate for overall thriving, learning, and vitality were .65, .60 and .64, respectively, suggesting that an appreciable amount of variance in observations of these variables occurred within person (i.e., for overall thriving 1.00–.65 = 35%; for learning, 1.00–.60 = 40%, and for vitality, 1.00–.64 = 36%). All ICCs were associated with significant χ2 test statistics (p < .001) suggesting that multilevel analyses are appropriate (Hox et al., Citation2017). The ICC2 values for overall thriving (.90), learning (.87), and vitality (.90) indicate that participants can be reliably differentiated in terms of thriving (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008). We also computed ICCs for NABM (ICC1= .78/ICC2 = .58) and ABST (ICC1 = .74/ICC2 = .63). ICC1 estimates suggest that an appreciable amount of variance in these variables occurred within-person. Likewise, ICC2 values suggest that participants can be reliably differentiated in terms of NABM and ABST (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008).

shows that while within-person NABM was not negatively related to thriving (B = −.02, p = .42), neither to learning (B = .05, p = .26), a significant negative relationship with vitality was found (B = −.08, p < .05). Thus, hypotheses 1a and 1b were not supported, whereas results supported Hypothesis 1c. Hypothesis 2 proposes that within-person NABM should be positively related to lagged within-person ABST next day, and findings supported this link (B = .59, p < .001).

Table 3. Summary of the within-person mixed-effects regression models predicting ABST and thriving.

Drawing on our theoretical rationale, we combined hypotheses 1a to 2 to posit that there were negative indirect effects of within-person NABM on (a) lagged overall thriving, (b) learning and (c) vitality through lagged within-person ABST. The statistical significance of the within-person NABM parameter in the lagged vitality model after accounting for lagged within-person ABST suggests that partial mediation is occurring (B = −.08, p < .001). However, this parameter was not statistically significant in the lagged thriving and learning models, suggesting evidence for full mediation (B = −.02, p = .42; B = .05, p = .26). A nonparametric bootstrap confidence interval with the BCa Method test (10000 replications) indicated a significant mediating effect of lagged within-person ABST on the relationship between within-person NABM and lagged thriving (CI95%[−.12, −.05], p < .001), lagged learning (CI95%[−.17, −.01], p < .05), and lagged vitality (CI95%[−.12, −.04], p < .001). Therefore, we found support for hypotheses 3a to 3c.

We further tested the moderation effect of perceived age similarity on the relationship between within-person NABM and lagged within-person ABST with a random slopes model (Hypothesis 4). According to expectations (see ), we found a significant two-way cross-level interaction (B = −.15, p < .05). Considering that our data are hierarchically clustered, and our moderate level-2 sample size, it is important to provide information about cumulative probabilities of finding significance for our cross-level interaction effects (Arend & Schäfer, Citation2019; Bliese & Wang, Citation2020). Following the procedures outlined by Bliese and Wang (Citation2020), the estimated observed power of the random intercepts, fixed slopes model was of .94, and the cumulative probability of finding significant effects with the random intercepts, random slopes model was much lower (.65).

Table 4. Summary of the cross-level two-way interaction between perceived age similarity and within-person NABM predicting within-person ABST (t + 1).

To better understand the moderation effect, we plotted the two-way interaction in . When perceived age similarity was low (i.e., −1 SD from the mean), the relationship between NABM and ABST was positive and significant (B = .75, p < .001), and when perceived age similarity was high (i.e., +1 SD from the mean), the relationship was also positive and significant but much weaker (B = .39, p < .01).

Supplementary analyses

To demonstrate the causal direction from within-person NABM to within-person ABST, we conducted various supplementary analyses. Given that we were not focused on the differences at the person-level, we started by using fixed slopes models, and then compared them whenever possible with random slope models using likelihood ratio tests. We regressed Day t + 1 within-person NABM on Day t within-person ABST and within-person NABM in HLM. We found that NABM (Day t + 1) was not significantly related to ABST (Day t) after controlling for NABM (Day t): B = −.02, p = .65. The fixed slopes model was a better fit to the data than the random slopes model (χ2(5) = 1.68, p = .89). These results support the claimed causal direction from NABM to ABST rather than from ABST to NABM. Using the same procedure, we regressed Day t + 2 within-person ABST on Day t within-person NABM and within-person ABST (Day t + 1) to test when the equilibration period comes to an end. In our study, the equilibration period refers to the causal interval period that it takes NABM to affect ABST and for the changes to equilibrate (Mitchell & James, Citation2001). Given that ABST (Day t + 2) was not significantly related to NABM (Day t) after controlling for ABST (Day t + 1): B = −.07, p = .43, it seems that the age-based concern triggered by NABM wears off and that the anger lingers after a one-day period. We also tested for same-day effects through the regression of Day t within-person ABST and Day t thriving scales on Day t within-person NABM. We found that NABM is not related to same-day ABST (B = −.01, p = .88), nor to same day thriving (B = −.01, p = .59), learning (B = .01, p = .66), and vitality (B = −.03, p = .22). Fixed slopes models were a better fit to the data than random slopes models for thriving (χ2(2) = .12, p = .94), learning (χ2(2) = .40, p = .82), and vitality (χ2(2) = 1.05, p = .59).

Discussion

This study was set out with two intertwined goals. Regarding the first aim, our findings provide support for the claim that NABM may be considered a job stressor as negative direct and indirect effects of NABM on thriving were evinced. It is interesting to note that NABM had negative direct effects only on lagged vitality, suggesting energy depletion caused by negative views about one’s age group (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2018), but no effects on lagged thriving and lagged learning were found. The lack of support for the NABM-learning link may have something to do with the relatively low average age of our sample ( = 37.45). Indeed, previous research failed to find significant relationships between NABM held by younger and middle-aged employees and learning (Oliveira, Citation2021), and generally, most learning opportunities are offered to these age groups rather than to their older co-workers. Thus, it is possible that both increased availability and additional motivation to engage in learning activities among relatively younger workers explains why NABM are unrelated to learning and by, extension, thriving in our study. Besides, learning levels are more stable than vitality levels (Niessen et al., Citation2012) and less susceptible to co-workers’ actions or impressions (Moore et al., Citation2021). Taken together, our findings about the direct relationships between NABM and thriving substantiate the theoretical relevance of looking beyond an overall thriving measurement (Kleine et al., Citation2019).

Following the calls for the examination of ABST ramifications above and beyond older age groups (Lamont et al., Citation2021), our sample also included younger and middle-aged participants. Given that NABM had negative indirect effects through lagged ABST on lagged thriving, lagged learning, and lagged vitality, it seems, therefore, that ABST consequences are problematic not only to older employees as previously suggested (von Hippel et al., Citation2019). Moreover, these findings are consistent with the age-based metastereotype activation model and affective events theory, supporting the idea that NABM are the trigger of a sequential process that obstructs thriving at work (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019). Additionally, our study corroborates previous empirical work that highlighted the linking role of ruminative thoughts in the relationship between emotional triggers and the thereby resulting attitudes/behaviours (Wang et al., Citation2013). Indeed, within-person NABM was positively related to lagged within-person ABST next day, suggesting that this strong next-day effect may result from ruminative thoughts taking place at the end of the workday that boost next-day age identity concerns (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Citation2008), which in turn impede thriving. Moreover, supplementary analyses showed no relationship between same-day NABM and ABST and that the concern triggered by NABM seems to linger after a one-day period. Taken together, these findings suggest that the evening and night period, rather than allowing one to disconnect and recover from negative work events (Sonnentag & Niessen, Citation2020), end up strengthening the NABMABST link. In this way, this study contributes to the ageism and thriving literatures through the time specification of how and when workplace ageism shapes thriving at work (McCormick et al., Citation2020; Mitchell & James, Citation2001). Specifically, by capturing in a next-day fashion the within-person dynamics in employees’ thriving triggered by specific NABM (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019), this study carries the potential to meaningfully advance the workplace ageism and thriving scholarships.

Taking into account that NABM's harmful effects on lagged thriving and lagged learning occur via ABST, understanding the contingencies that shape ABST is critical from a theoretical and practical perspective alike. Regarding our second aim, perceived age similarity had a buffering effect that lessened the feelings of concern triggered by NABM. This suggests that stereotyped employees may have benefitted from social support from their age group co-workers in challenging NABM (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2017; Steele et al., Citation2002). In a nutshell, findings suggest that perceived age similarity is a relevant contextual factor of the ABST experience, thus contributing to show the importance of relational demography in employees’ growth.

Practical implications

Our findings recommend several courses of action for practitioners. Considering the detrimental effect of NABM on thriving, and particularly the boosting role played by ABST, organizations need to develop a climate for age inclusion. For example, HR practices available to all workers irrespective of their age may be of great help in the context of age-diverse workforces. As these practices promote employees’ feelings of inclusion and due treatment, the employees’ need for a positive age identity is met raising the likelihood of positive social exchanges in the organization (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2018). By the same token, age identity safety can be fostered through the presentation of in-group role models (Oliveira & Cabral-Cardoso, Citation2017) and, whenever possible, by setting up age-balanced teams. Bearing in mind the buffering role of perceived age similarity found in this study, this latter HR initiative is particularly important as in-group co-workers provide stereotyped employees the social support they need to challenge NABM. Another important practical implication of NABM's harmful effect on thriving is that organizations should emphasize common characteristics and shared goals all employees have in order to foster a sense of inclusion and belongingness particularly among stereotyped employees (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Specifically, organizations could rely on the four-phase model suggested by Haslam et al. (Citation2003). The Actualizing Social and Personal Identity Resources (ASPIRe) model is built around the premise that individuals define themselves in terms of social categories and that one’s self-categorization as a member of a common higher-order ingroup facilitates the development of one’s social capital. Considering the benefits of common higher-order in-group self-categorization in terms of perceived trust and communication between organizational members, the ASPIRe model may be well suited to help organizations to shield workers from age identity threats. In so doing, organizations should start by ascertaining which social identities employees use collectively to define themselves, which goals should be attached to these higher-order social identities, to then establish “a new organic organizational identity” (Haslam et al., Citation2003, p. 83). In this regard, the role of managers is critical as an effective implementation of HR practices seems to be contingent on the managers’ support and involvement in those workplace interventions (Straub et al., Citation2018). Moreover, findings also inform managers of the benefits of a granular vision of thriving. For instance, as negative short-term effects of NABM on thriving occur mainly via vitality, suggesting energy depletion, age management interventions should include metastereotyping reframing activities on a regular basis. Given that employees may interpret NABM as challenges or as threats (Casad & Bryant, Citation2016; Searle & Auton, Citation2015), practices like mentoring and reverse mentoring may set the ground for stereotyped individuals to challenge NABM and to reframe their content. Also, opportunities such as these may elicit social recategorizations and/or reinforce shared higher-order social identities within the organization (Casad & Bryant, Citation2016; Haslam et al., Citation2003).

Limitations and future research

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, all constructs were self-reported. Although most of the focal variables are idiosyncratic, future research could assess thriving levels, for instance, through co-workers’ reports. Herewith, concerns of retrospective bias resulting from participants’ self-assessment of average afternoon thriving levels at the end of the workday could also be addressed. Second, the within-person reliability estimates of the focal outcomes, particularly the vitality dimension, were low. Hence, results must be interpreted with caution and future studies should be undertaken to see whether our findings replicate (Nezlek, Citation2017). Third, it would be important to control for established predictors of thriving such as task focus, exploration, and heedful relating as these agentic work behaviours may be related to NABM and ABST as well. Fourth, along with the moderators included in our model, other boundary conditions of NABM like age-metastereotype consciousness may bring additional clarity to our understanding of the age metastereotyping process. Admittedly, individuals might differ on the vigilance levels of what other groups think of one’s age group (Finkelstein et al., Citation2019), and hence studies on the implications of this individual difference for employees thriving are clearly recommended. Fifth, because rumination was not measured in this study, further work needs to empirically capture rumination levels to establish whether rumination is de facto the driving mechanism behind the NABM delayed effect. Finally, since most participants have attended higher education and education is positively associated with thriving (Kleine et al., Citation2019), future research should concentrate on employees with lower levels of education achievement to examine if our findings hold.

Conclusion

This study highlights the short-term consequences of NABM, one of the factors that may obstruct thriving at work. Framed in a next-day causal model, study’s findings suggest NABM as a job stressor that inhibits thriving directly and indirectly through ABST, and recommend a clearer distinction between thriving dimensions. Perceived age similarity in the team shields employees from the concern triggered by NABM. Overall, the current study improves our understanding of the dynamic interplay between workplace ageism and thriving.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For the sake of clarity, “team age composition” refers to the individual perceptions of employees about age similarity in one’s unit/team. In the current study, all data were collected at the individual-level.

References

- Arend, M., & Schäfer, T. (2019). Statistical power in two-level models: A tutorial based on Monte Carlo simulation. Psychological Methods, 24(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000195

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Berger, J., & Heath, C. (2008). Who drives divergence? Identity signaling, outgroup dissimilarity, and the abandonment of cultural tastes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.593

- Bliese, P., & Wang, M. (2020). Results provide information about cumulative probabilities of finding significance: Let’s report this information. Journal of Management, 46(7), 1275–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319886909

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. The Guilford Press.

- Butler, R. (1969). Age-ism: Another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist, 9(4), 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.4_Part_1.243

- Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. Academic Press.

- Casad, B., & Bryant, W. (2016). Addressing stereotype threat is critical to diversity and inclusion in organizational psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00008

- Chiaburu, D., & Harrison, D. (2008). Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1082–1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1082

- De Meulenaere, K., & Kunze, F. (2021). Distance matters! The role of employees’ age distance on the effects of workforce age heterogeneity on firm performance. Human Resource Management, 60(4), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22031

- European Commission. (2019) . Discrimination in the European Union - Special Eurobarometer 493. European Commission.

- Fasbender, U., & Drury, L. One plus one equals one: Age-diverse friendship and its complex relation to employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions. (2021). European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(4), 510–523. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.2006637

- Finkelstein, L., King, E., & Voyles, E. (2015). Age metastereotyping and cross-age workplace interactions: A meta view of age stereotypes at work. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wau002

- Finkelstein, L., Ryan, K., & King, E. (2013). What do the young (old) people think of me? Content and accuracy of age-based metastereotypes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(6), 633–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.673279

- Finkelstein, L., Voyles, E., Thomas, C., & Zacher, H. (2019). A daily diary study of responses to age meta-stereotypes. Work, Aging and Retirement, 6(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waz005

- Fuchs, C., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2009). Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research: Conceptual issues and application guidelines. Die Betriebswirtschaft, 69(2), 195–210.

- Gabriel, A., Podsakoff, N., Beal, D., Scott, B., Sonnentag, S., Trougakos, J., & Butts, M. (2019). Experience sampling methods: A discussion of critical trends and considerations for scholarly advancement. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 969–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118802626

- Geldhof, G., Preacher, K., & Zyphur, M. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032138

- Guillaume, Y., Dawson, J., Priola, V., Sacramento, C., Woods, S., Higson, H., Budhwar, P., & West, M. (2014). Managing diversity in organizations: An integrative model and agenda for future research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(5), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.805485

- Haslam, S., Eggins, R., & Reynolds, K. (2003). The ASPIRe model: Actualizing social and personal identity resources to enhance organizational outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(1), 83–113. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903321208907

- Hatzenbuehler, M., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Dovidio, J. (2009). How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x

- Hox, J., Moerbeek, M., & van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Kleine, A.-K., Rudolph, C., & Zacher, H. (2019). Thriving at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(9–10), 973–999. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2375

- Lamont, R., Swift, H., & Drury, L. (2021). Understanding perceived age-based judgement as a precursor to age-based stereotype threat in everyday settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 640567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.640567

- LeBreton, J., & Senter, J. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

- Matthews, R., Pineault, L., & Hong, Y.-H. (2022). Normalizing the use of Single-Item Measures: Validation of the Single-Item Compendium for Organizational Psychology. Journal of Business and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09813-3

- McCormick, B., Reeves, C., Downes, P., Li, N., & Ilies, R. (2020). Scientific contributions of within-person research in management: Making the juice worth the squeeze. Journal of Management, 46(2), 321–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318788435

- Mitchell, T., & James, L. (2001). Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 530–547. https://doi.org/10.2307/3560240

- Moore, L., Bakker, A., & van Mierlo, H. (2021). Using strengths and thriving at work: The role of colleague strengths recognition and organizational context. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(2), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1952990

- Nezlek, J. (2017). A practical guide to understanding reliability in studies of within-person variability. Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.06.020

- Niessen, C., Sonnentag, S., & Sach, F. (2012). Thriving at work – a diary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.763

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

- Ohly, S., & Schmitt, A. (2015). What makes us enthusiastic, angry, feeling at rest or worried? Development and validation of an affective work events taxonomy using concept mapping methodology. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9328-3

- Oliveira, E. (2021). Every coin has two sides: The case of thriving at work. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.55

- Oliveira, E., & Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2017). Older workers’ representation and age-based stereotype threats in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 32(3), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2016-0085

- Oliveira, E., & Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2018). Stereotype threat and older workers attitudes: A mediation model. Personnel Review, 47(1), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2016-0306

- Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.756

- Prem, R., Ohly, S., Kubicek, B., & Korunka, C. (2017). Thriving on challenge stressors? Exploring time pressure and learning demands as antecedents of thriving at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(1), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2115

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Ryu, E. (2014). Model fit evaluation in multilevel structural equation models. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 81. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00081

- Searle, B., & Auton, J. (2015). The merits of measuring challenge and hindrance appraisals. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 28(2), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2014.931378

- Shapiro, J. (2011). Different groups, different threats: A multi-threat approach to the experience of stereotype threats. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(4), 464–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211398140

- Sonnentag, S. (2012). Time in organizational research: Catching up on a long neglected topic in order to improve theory. Organizational Psychology Review, 2(4), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386612442079

- Sonnentag, S., & Niessen, C. (2020). To detach or not to detach? Two experimental studies on the affective consequences of detaching from work during non-work time. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 560156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.560156

- Spreitzer, G., Porath, C., & Gibson, C. (2012). Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Organizational Dynamics, 41(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.01.009

- Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S., & Grant, A. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16(5), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0153

- Steele, C., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797

- Steele, C., Spencer, S., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. 34,379–440 . Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80009-0

- Straub, C., Vinkenburg, C., van Kleef, M., & Hofmans, J. (2018). Effective HR implementation: The impact of supervisor support for policy use on employee perceptions and attitudes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(22), 3115–3135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1457555

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, K., & Imai, K. (2014). Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 59(5), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v059.i05

- Van der Heijden, B. (2018). Interpersonal work context as a possible buffer against age-related stereotyping. Ageing & Society, 38(1), 129–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16001148

- von Hippel, C., Kalokerinos, E. K., Haanterä, K., & Zacher, H. (2019). Age-based stereotype threat and work outcomes: Stress appraisals and rumination as mediators. Psychology and Aging, 34(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000308

- Walumbwa, F., Muchiri, M., Misati, E., Wu, C., & Meiliani, M. (2018). Inspired to perform: A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of thriving at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2216

- Wang, M., Liu, S., Liao, H., Gong, Y., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., & Shi, J. (2013). Can’t get it out of my mind: Employee rumination after customer mistreatment and negative mood in the next morning. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033656

- Weiss, H., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (pp. 1–74). JAI Press.

- Zhang, Z., Zyphur, M. J., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 695–719. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108327450

Appendix

NABM

Today, I have the impression my middle-aged/older co-workers feel that I am unreliable because of my age.

Today, I have the impression my younger/older co-workers feel that I am unavailable because of my age.

Today, I have the impression my younger/middle-aged co-workers feel that I am slower because of my age.

ABST

Today, I am concerned that my actions might confirm the negative stereotypes about my age group in the minds of my co-workers.

Today, I am concerned that my actions might poorly represent workers of my age group.

Today, I am concerned that my actions will reinforce the negative stereotypes about my age group in the minds of my co-workers.

Thriving at work

At work …

Learning

I continue to learn more and more as time goes by.

I find myself learning often.

I see myself continually improving.

I am not learning. (R)

I am developing a lot as a person.

Vitality

I feel alive and vital.

I have energy and spirit.

I do not feel very energetic. (R)

I feel alert and awake.

I am looking forward to each new day.

Perceived age similarity

Most of my teammates are from my age group.