ABSTRACT

The engagement of both school and university has played a significant role in initial teacher education. The focus of this paper is the growth of an alternative style of school-university partnership from a single school to a Hub of 19 school-university partnership, in the inner-west suburbs of Sydney, Australia. Four school and university mentors who have participated over a seven-year period have completed surveys on their engagement. Using a Community of Practice (CoP) theoretical framework to underpin model development, it is possible to showcase the growth of the partnerships as important in informing discussion relating to the implementation of integrated school-university partnerships and practice.

Contextual background

Schools have long made valuable contributions to university-based programmes for initial teacher education (ITE) specifically through the professional experience component (Babic, Citation2019). ITE has recently come under public scrutiny (e.g., Walker et al., Citation2019) as teacher quality, particularly professional readiness of newly graduating teachers, has been attributed to the decline in Australian school students’ reading, mathematics, and science skills (OECD, Citation2019). In addition, universities have also been criticised for engaging in practices that develop decontextualised ITE programmes that do not match school needs (Nguyen, Citation2020). Consequently, there is no abatement in calls for the school-university partnership agenda to develop strong models of integrative practice that meet pre-service student needs.

The key imperative of state and federal educational policy makers has been the drive for universities to produce profession ready graduates with skills and capabilities that meet the demands of professional practice (Aprile & Knight, Citation2019; Billett, Citation2015; Nguyen, Citation2020). A consequence of this has been the accreditation of many university programmes being benchmarked against their ability to produce graduates who satisfy the demands of prospective employers. There is consensus that integrated and situated learning for pre-service teachers with guidance and collaborative efforts from university and school-based mentors is critical for the development of profession ready teachers (Bahr & Mellor, Citation2016; Darling-Hammond, Citation2006). As a result, the recent past has witnessed a significant focus on the balance between university emphasis on academic rigour and the demands of school systems to produce teachers who can deliver effective instruction upon graduating (Aprile & Knight, Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2016; McNamara et al., Citation2013). The nature of university-school partnerships has historically been tilted towards universities’ accessing research participants to meet their research agendas with little consideration of school systems and the problems they face that would benefit from research to provide a way forward (Jones et al., Citation2016; Nguyen, Citation2020). The Australian government has bridged this divide by commissioning studies across three distinct phases with each calling for greater collaboration between schools and universities in ITE.

The first phase commenced in 2008 when the Council of Australian Government (COAG, Citation2008), the peak intergovernmental body that leads reform in Australian education, released its policy, National Partnership Agreement on Improving Teacher Quality (TQNP). It was based on this policy that Australian universities developed “partnership” models of professional experience where pre-service teachers are to be immersed in school communities and to develop ongoing professional relationships with in-service teachers at the school. This policy marked a significant and fundamental shift away from the discourse of in-service teacher as supervisor, to the in-service teacher as mentor (Manton et al., Citation2021).

The second phase in 2014, influenced by the Melbourne Declaration (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA), Citation2008), resulted in the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers Report (Citation2014). This report promoted the idea of systems-based partnerships, where schools and universities would support the “integrated delivery of initial teacher education” (p. 4). In this way, the intention of Teacher education ministerial advisory group, (Citation2014), was to improve the professional readiness of pre-service teachers by bridging the theory-practice divide in ITE by placing the professional experience, at the centre of ITE programme curricula (Billett, Citation2015). This approach was further affirmed by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) in their Initial Teacher Education Program Standards (Citation2015).

The third and current phase is underpinned by the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration (Department of Education, Skills and Employment [DESE], Citation2019), that identifies broader aims focused on evidence-informed and data-driven partnerships. The Declaration (2019) notes, “All Australian Governments and the education community, including universities, must work together to foster high-quality teaching and leadership. In February 2022 the Australian Government released the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review (QITE) (DESE, Citation2022, paragraph 3) with three key areas:

Attracting high-quality, diverse candidates into initial teacher education

Ensuring their preparation is evidence-based and practical

Supporting early years teachers.

School-university partnerships

Although school-university partnerships in ITE have become a priority in state and federal education policy documents, the research literature on the impact of such partnerships for producing profession ready graduates is sparse (Jones et al., Citation2016). Moreover, there is no blueprint on how to establish, manage and sustain high-quality partnerships nor understanding of the impact on producing profession ready graduates. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to understand high quality partnerships and the impact these partnerships have on producing profession ready graduates. To achieve this purpose, the following research question guided the study:

How can school-university high quality partnerships be established, managed and sustained?

The Australian Catholic University-Strathfield South public school partnership project: introduction

During phase 2 of the Australian Government’s series of studies on greater school involvement in ITE, the NSW Department of Education (NSW DoE) responded to the Great Teaching Inspired Learning – Blueprint for Action (GTIL) (NSW Department of Education and Communities, NSW Institute of Teachers, & Board of Studies NSW, Citation2013), a ministerial call to improve the quality of teaching and learning in NSW schools. The GTIL Blueprint identified 16 proposed outcomes, with one focused on ITE. This ITE outcome included heightened entry-requirements into teacher education, strategies to attract the “best and brightest” (p. 8) and the need for pre-service teachers to receive “high quality professional experience” (p. 9). As noted above the focus of this study is the provision of high-quality professional experience.

In response to this call, the NSW Department of Education (DoE) developed the Professional Experience Hub (PEX Hub) Framework to strengthen and guide university-school partnerships (NSW DoE, Citation2016). As a result, universities in NSW were partnered with a school(s) in close geographic proximity. The Australian Catholic University (ACU) was assigned a single NSW Department of Education primary school in the inner west of Sydney, Strathfield South Public School (SSPS) and three academics from ACU’s School of Education were assigned by the Faculty of Education and Arts Executive Dean, to collaborate with SSPS in the PEX Hub. A memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed at the school system level and agreed upon by ACU executives.

The ACU-SSPS partnership was committed to preparing pre-service teachers for the challenges of teaching and in this way, they formed a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991).

Theoretical foundation

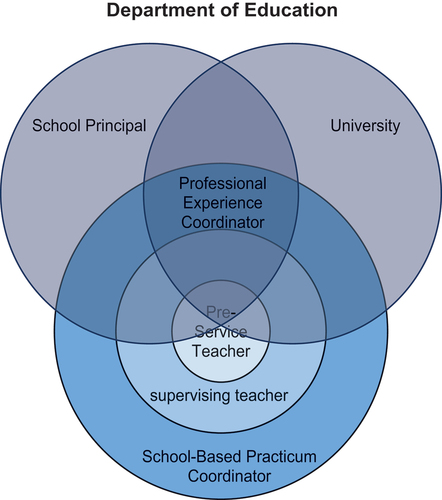

The concept of community of practice has been described as “a set of relations among persons, activity, and world, over time” and as being “an intrinsic condition for the existence of knowledge” (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, p. 98). Consequently, sociocultural theories of learning place community, cooperation and collaboration are at the heart of the development of the community of practice (CoP) process. In the ACU-SSPS CoP there was at the beginning a diverse group of educators, from different backgrounds, with varying degrees of experience and discipline knowledge, who worked intentionally from the peripheries. captures diagrammatically the overview of the starting point of study where the university and school participants are identified. Evident in this figure is the school principal, the University more broadly, and the university based professional experience coordinator who were peripheral to the action of the pre-service teacher, the mentor teacher and school-based practicum coordinator. This intentional delineation of roles was based on a belief that each served a different and specific purpose, and while the coordination among these groups was important, it was not necessary for a closer interactive relationship.

The purpose of presenting this starting model is to make a distinction between the dialectical relationship described in this paper and the cited documents, from the traditional university-school relationship centred around professional experience placements. As distinct from professional experience placements represented in , the position taken by participants in this study and presented below is that the development of their relationship involves deliberate collaboration and action from both the school and university, where academics and teacher educators work seamlessly alongside one another as part of the ITE programme, co-creating and sharing ideas and resources to enhance the teaching and learning process. Such university-school partnerships involve the conscious collaboration that includes an equal and dialectical relationship between university academics and teacher educators in support of developing profession-ready pre-service teachers. TEMAG (Citation2014) in particular, unreservedly singled out integrated delivery of ITE as a precursor to ensuring alignment with the expectations of schools and employers and this perspective was reinforced in the QITE Review (Citation2022).

The three distinct phases of Australian Government intervention in ITE, brought about this change in sentiment regarding the importance of university and school collaboration. For the ACU-SSPS partnership, a CoP seems to best capture the intent of school and university members as it is made up of a “group[s] of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2015, para. 3). The participants in the ACU-SSPS partnership commenced with a commitment to preparing pre-service teachers for the challenges of teaching and in this way, they shared a domain of interest (Wenger, Citation1998). This new community of school teachers and university academic staff were committed to working together as mentors for the pre-service teachers in their care. In this way they deliberately worked to cultivate the group where the emphasis is on legitimate peripheral participation with a view to becoming a central member (Buckley et al., Citation2019). To do this they developed over time a shared repertoire of resources as practitioners in the field. Their practice aligned directly with the evolving and multifaceted work on CoP that had moved from Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) early work, to the more recent CoP theory (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2014), used to guide this study as it encompasses a landscape of practices that are made up of a complex system of communities of practice and the boundaries between them.

Part of this evolving theory on CoP is the capacity to engage fully all members of the community, that necessarily requires them to cross boundaries and includes participation through conversation, engagement, reflection and reification through the development of documents, processes and procedures (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2015). However, the structure of the CoP remains based on earlier work (Wenger et al., Citation2002) that unifies three components: the domain as the area of knowledge that brings the community together, the community as the group of people for whom the domain is relevant, and the practice as a body of knowledge, methods, artefacts and stories that members share and develop together. It is through participation, that members of the community develop a sense of identity and belonging, which are central to forming partnerships built upon trust, respect and reciprocity (Le Cornu, Citation2016). This is the focus of this study, and with the use of the theory of a CoP it is possible to understand how school-university partnerships are established, managed and sustained, and the impact this has on developing profession ready graduates.

Study background

Over the seven years of the ACU-SSPS (2015–2021) school participation has grown from one school to 19 schools in the western suburbs of Sydney. This growth in the ACU-SSPS partnership provided pre-service teachers with access to accredited teacher and academic mentors to guide their professional experience. captures the growth of the programme since its inception, including the number of schools, mentor teachers and pre-service teachers involved.

Table 1. Growth of the programme.

In the beginning of the ACU-SSPS partnership, the intent was to create a functioning CoP that fully integrated school system strategic and operational intent into university structure, theoretical content and professional experience. This required establishing common goals as a starting point. MacLeod et al. (Citation2008) describe an authentic, practice-driven approach based on distributed leadership through the sharing of power. This moves the partnership beyond the formal MoU to the co-creation of a shared vision and aims focused on the purpose of improving the professional experience for pre-service teachers through the close collaboration of school and university staff. For this to be achieved, a Mentoring Accreditation Programme for Mentors of Pre-service Teachers was developed and delivered by ACU academics. The combination of these factors, informed by the TEMAG (Citation2014) and NSW Government (Citation2013) imperative for high-quality professional experience, co-identifying three critical needs, aligned to the three dimensions of a CoP (Wenger, Citation1998):

building a nexus between schools and universities (Domain: mutual engagement)

making visible “university” in schools (Community: Joint enterprise) and

developing quality teacher mentors (Practice: shared repertoire).

Participants

School and university mentors who have continuously participated in this study over the seven-year period from 2015–2021 were invited in 2021 to participate in survey completion reflecting on the partnership. As a result, three school mentors and one ACU academic mentor were identified as being involved for the entire seven-year period; their perceptions are reported in this paper. See below for the list of participants (pseudonyms have been used for each mentor), and their roles at the commencement of the partnership and at time of data collection. Worthy of note is that at the commencement of the ACU-SSPS partnership all participants were learning through their participation in the CoP. They would have been considered as Wenger (Citation1998) terms “peripheral participants” although as the participants became more actively engaged in the practices of the community they could be deemed to have transitioned to “expert participants” (p.4). This growth in professional recognition is also evidenced in their advanced roles within their schools.

Data collection

The study received ethical approval from the Human Research Committee at ACU which permitted the collection of the following data to track the progress of the ACU-SSPS partnership. The CoP was documented through each iteration of the ACU-SSPS partnership. This was achieved through annual surveys completed by school and university mentors. Surveys were designed to take approximately 40 minutes to complete. Survey data were recorded, transferred to Excel and deidentified. Survey data specifically used for this paper were collected between 2019 – 2021 with those participants who had participated in the project from 2015–2021. Their perceptions of the project over this timeframe form the basis of this paper.

Data analysis

The intention of the ACU-SSPS partnership was to develop a CoP that reflects the common passion of both school and university mentors to develop profession ready pre-service teachers and through their ongoing integration enhance the mentoring they offer as they interact more regularly and effectively. With this intention in mind, a CoP framework is utilised in this study. The CoP provides potential for conceptualising, illuminating and analysing the school-university partnership. In particular, the three dimensions of a CoP: Domain: mutual engagement; Community: joint enterprise and Practice: shared repertoire (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991) have been used as themes to guide the analysis of the data collected (see ).

Figure 3. Three indicators of Wenger’s (Citation1998) CoP and as it related to this study.

Study limitation

Covid-19 restrictions impacted on the implementation of the programme in 2020 as it became difficult to place pre-service teachers in schools. In addition, maintaining contact with school based PEX Hub Coordinators was also a challenge along with ensuring they were engaged in consistent practices. Another limitation was the quick growth of the number of participating schools. This growth stretched university personnel and resources as university staff tried their best support all stakeholders. Further, this study has reported on the partnership over the full period from 2015–2021. As a result, the participants reported in this study are limited to those who were engaged from the time of its commencement.

Understanding the community of practice and its impact on ITE

Through the ACU-SSPS partnership, we explore the successes and tensions surrounding the growth and development of the CoP through Domain: mutual engagement, Community: joint enterprise and Practice: shared repertoire.

Domain: mutual Engagement – building a nexus between schools and universities

Mutual engagement, within a CoP, is defined as people “engaged in actions whose meanings they negotiate with one another” (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 73). In the case of the mentors in this study, the rules around mutual engagement were organically grown rather than defined at the commencement of the partnership. It required a move away from the university and schools each working independently to a recognition by all mentors that mutual engagement was required to ensure the partnership’s success. To achieve mutual engagement, the project created an online networking platform, initially for one school, that grew to engage all Hub schools and the university, as they sought to bridge the policy-practice divide in ITE. This initiative was designed to encourage open and timely dialogue and responsive communication that was accurate and transparent, where all views are valued. Survey responses from the school-based mentor teachers identified the importance of mutual engagement and their support for the notion of “complementary contributions” (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 76), where all participants are open to give and receive help, as a foundation for success:

The success [of the ACU-SSPS over the seven years] has been built on a foundation of like-minded dedicated professionals with a common cause of the shared responsibility for preparing profession ready graduate teachers (Jay).

Based on the active and mutual engagement within the CoP, teacher mentors assumed leadership of the ACU pre-service teacher professional experience. The upskilling of mentors provided through the mentor accreditation programme by ACU mentors resulted in professional growth concluding with opportunities for promotion:

My responsibilities have changed over the course of my involvement with the PEX Hub beginning in 2015. Initially I was responsible for mentoring PSTs [pre-service teachers]. My role then changed to PEX Hub facilitator. These new responsibilities included liaising with Hub principals to determine numbers of teacher mentors to take on prospective PSTs for forthcoming practicums. I also facilitated the training of new mentors made possible through my mentor accreditation, communicating with them and providing follow-up support (Logan).

And:

When I first began as a mentor, I understood the partnership to be guided by recent department policy, GTIL, and its purpose to increase the quality of practicum experiences for PSTs thereby creating more classroom-ready teachers. I undertook mentor training to increase my capacity to build supportive mentor relationships with PSTs and link me in with a community of practice that would provide me with information and guidance in day-to-day responsibilities. My understanding of the partnership shifted when I took on the role of PEX Hub facilitator and I delved more into the GTIL policy document to discover the research and case studies forming the foundations of the policy. ACU mentor training also contributed to my understanding of mentor relationships and the impact this has on the PST placement experiences (Harper).

Mentor engagement supportive of evidence-based practice

Both teacher and academic mentors value the practical components of ITE. Mutual engagement involving the development of evidence-informed professional experience initiatives were captured by a mentor teacher as having a significant impact in affirming the importance of these approaches to raising the standard and improving the quality of the professional experience:

This came at a time of reform when perceptions were that we were not producing quality teaching graduates … ACU mentor training was an initiative that improved the practicum experience by providing quality frameworks on mentoring based on research (Jay).

The provision of the mentor resources was not restricted to ACU providing the accredited programme. Rather mentors also worked to collaboratively provide resources for all Hub participants. Their contributions assisted the development of the identity of their CoP were valued with the following commenttypical of mentor perceptions:

PEX Coordinators at SSPS select and collate evidence-based resources into a shared drive for all mentors across our 19 schools. Its purpose is to have a “one stop shop” for time-poor mentors so that they do not have to search for practicum materials from disparate sources (Harper).

Mentors as researchers and reflexive practitioners

As the teacher mentors engage with the ACU Mentor Accreditation Programme, the partnership created opportunities for mentors within the CoP to become teacher researchers and reflexive practitioners.

I now better understand the latest research around mentor teaching, and I can utilise some of the strategies when providing feedback to other teachers on their practices. I have become more aware of my own capabilities, and the important role I will have in developing a supportive relationship (Harper).

They feel strongly that they now use research evidence to improve their mentoring skills and classroom practice.

During placement, I gather data on PST learning needs and design a curriculum of micro-skills several times a week for lunchtime workshops. At the conclusion of the placement, I collect data on practicum experiences and mentor experiences… (Harper).

Logan, who commenced as a mentor teacher and was promoted to the PEX Hub Coordinator role, concurred that the project developed her research practice while also strengthening her interpersonal skills.

I have received mentor training to prepare me for the role as mentor. This has enabled me to engage with contemporary research in the area of mentoring. As a PEX Hub facilitator my skills in communicating with a range of people from PSTs to principals has strengthened. My abilities to collect qualitative and quantitative data from mentors and PSTs have improved (Logan).

The university PEX Coordinator agreed that the research undertaken by mentors in school was beneficial, leading to improved collaborations.

There have been instances where mentors have engaged in action research focusing on their pedagogical practice. Outcomes of their action research has resulted in modifications to the PST mentoring processes e.g. round table discussions with a focus on scaffolding learning (Riley).

Mentors also extended their research roles to present papers at conferences and the collaboration on peer-reviewed journal articles, demonstrating the lasting impact of the CoP and PEX Hub. Key findings from the Hub have been disseminated to model best practice by the NSW Department including growth from one school to a community of schools. The induction processes trialled in the Hub are now a part of all professional experiences in Hub schools. Additionally, findings from the study contributed to professional learning on mentoring practices, strategies for informed professional judgement and round table professional learning for PSTs, for example, classroom management strategies. These regular mentoring interactions assisted relationships forming around a common endeavour. The university PEX Coordinator expressed her perceptions on undertakings.

Regular checks occur together with the academic mentor, the PEX Coordinator and the teacher mentors. For example, school visits occur throughout the year. On-site conversation with all stakeholders takes place about how a combined approach can support the PSTs (Riley).

Community: joint enterprise – making visible ‘university’ in schools

Joint enterprise is the process within the CoP whereby the aims, outcomes, approach and role descriptions, have been negotiated and mutually agreed by all (Wenger, Citation1998). In this study, clear timelines were collaboratively developed and measures, such as the development of communication methods and evaluation points for all stakeholders, were put in place to ensure that all mentors were clear on requirements and to ensure that the intended outcomes were achieved in a timely manner.

Learning as social participation

Describing the evolution of the partnership over the seven-year period, a mentor teacher captures the importance of the multi-directional and timely communication.

There is joint decision making and collaboration at all times. It is exemplified in all communication between partners, in joint collaboration for research and the consistent improvement in all daily routine organisational aspects … Any changes to the practicum requirements are discussed or investigated collectively and not imposed on any member of the partnership. The Council of Deans resources (http://nswcde.org.au/resources/) was developed in deep collaboration between our ACU and the Hub schools (Jay).

Collaborative approach to learning has seen many rewards with the university PEX Coordinator pointing out a number of additional co-constructed documents.

The partnership has allowed for co-construction and review of university teaching documents. For example, the lesson plan template was reviewed by mentors in the Hub, updated by the university and embedded in curriculum units. Personnel from the Hub have also supported the development of mentoring professional learning materials (Riley).

Learning is central to CoP identity

A major criticism of university ITE programmes is that they are decontextualised and thus divorced from the realities of schools (Le Cornu, Citation2016). This project made strides towards closing this gap.

The ACU-supplied face-to-face mentor training is a cornerstone of the success of our Hub. The relationships formed for our community of practice from the initial introduction into the high expectations and ethos of the Hub. We are building the capacity of accredited CRTs (Casual Relief Teachers) and middle leaders in our schools through this training. (Jay)

This professional learning provided the opportunities for the school mentors to increase their professional involvement with comments such as the following reflective of the mentors’ perceptions of what they have achieved.

I designed and created pre-practicum information for both PSTs and Mentors, specific to each school placement. I conducted induction orienting PSTs to the school. I collect data on PST induction experience checking that PSTs had received essential information about their placement including emergency information and school routines. I negotiate a schedule for university supervisors to visit PSTs (Harper).

Embodying the CoP foundations, all mentor’s views were valued, university academics mentors worked collaboratively with school mentors to create context specific programmes for pre-service teachers. The presence of the university mentors in the schools not only benefited the pre-service teachers, but also the mentors:

It has strengthened my individual capacity by improving substantive conversation skills, establishing learning agreements with PSTs, building professional values and ethics, building trust and respectful openness with colleagues and learners in a two-way process. It has developed my professional autonomy and observation and feedback skills (Harper).

Practice: shared repertoire – developing quality teacher mentors

Cognisant of the NSW DoE mandate that practising teachers could not mentor a pre-service teacher without undertaking mentoring professional learning, context specific professional learning was developed to address that pressing demand in the form of an accredited programme. The leaders developing this programme were mindful of developing a training programme that aligns with the needs of schools and that would ultimately invite collaborative participation. Consequently, ACU team members attended a training session in November 2015, focusing on the ACU Mentoring Professional Learning programme for all states. Several meetings were held with the SSPS principal to streamline the partnership agenda and goals. Following this, the team refined the ACU mentoring model to align with evidence-based practices and adult learning principles (Ambrosetti et al. (Citation2014); Carroll et al. (Citation2010). The teacher mentors worked collaboratively with university academics to co-construct and develop theoretical unit content. This content is now delivered by the teacher mentors to bridge the theory-practice divide. Thus, this process provides valuable professional learning and research opportunities for both the teacher educators and university academics.

A key feature of the collaboration is the co-construction of practical solutions in mutual settings where participants’ views are respected as authentic. To engage with mentors while pre-service teachers were on their placement, ACU academics, principals and the two school-based PEX Hub Coordinators collaborated and initiated a school visit schedule to connect with each mentor and obtain feedback on their experiences. This proved beneficial for mentor teachers as it continued the professional learning outcomes within their classrooms and schools. The university PEX Coordinator commented that “changing the mindset of having a ‘good’ pre-service teacher assigned to a school/mentor to now be about working with the mentee to build their capacity to be profession ready” initially proved to be a tension point.

From 2019, the school based PEX Hub Coordinators engaged in training to facilitate the accredited mentoring programme to bring new mentors on board. The plan is to revisit and facilitate Professional Learning (PL) that is at the Lead and Highly Accomplished Teacher levels.

Professional growth of mentor teachers

The partnership addressed the NSW DoE mandate of improving the professional experience of pre-service teachers through staff developing mentor teachers. The university PEX Coordinator identified in her survey data that in “preparing the PSTs for placement in the diverse school settings … We rely heavily on school partners to support the contextual nature of the school setting and that doesn’t always happen.” However, to align PL with the needs of schools, ACU academics attended training sessions to better understand the context within which ITE students undertook placement. Ultimately, the partnership resulted in upskilling of school and university staff as evidenced by responses from both:

Developing my mentoring skills and applying the scaffolds provided in training for feedback and challenging conversations. Using interpersonal communication skills to assist PST’s in developing their pedagogy. I participated in mentoring round tables to develop exemplars for best practice among our Hub schools (Harper).

And

I attended a training session, together with 8 NSW colleagues, in November 2015, focusing on the ACU Mentoring PL. I met regularly with the principal … , and AP [Assistant Principal] at the time … and decided to work towards building the capacity of practising teachers to mentor PSTs. I attended all school based and NSW based meetings/conferences (University Academic, Logan).

In the past teachers did not receive specific training in developing professional mentoring relationships. The partnership addresses the need for pre-service teachers to be mentored by teachers with skills as a pre-service teacher mentor.

In the past teachers at our school did not receive specific training in developing professional mentoring relationships. Through several conversations that I have had, teachers now feel a greater level of confidence in building these relationships and managing challenging conversations. Pre-service teachers at the end of their placement regularly commenton the successfulness of the relationship they developed with their mentor teacher (Logan).

The university PEX Coordinator’s comments on her survey were in agreement with the school based PEX Coordinator.

It is evident that the mentors have increased their capacity to be reflective practitioners during this process. At times, touch point surveys are sent to mentor teachers to reflect on their practices, areas they require further development with, and support required. The PEX Coordinator discusses those responses with the university lead and support strategies are implemented. For example, a shared understanding was required for the final year assessment measure, GTPA [Graduate Teacher Performance Assessment], a support document with probing questions for mentor use was developed and shared with the mentors (Riley).

Through mutual engagement, the professional growth of the mentor teachers was evident. There was a significant and positive impact on the professional growth of the mentor teachers, and as a result, the improved quality of the professional experience for the pre-service teachers. Supporting this finding, two mentor teacher’s commentbest captures the sentiment of those surveyed by arguing that the partnership created an environment for nurturing high quality pre-service teaching experiences through strengthening and building the capacity of the mentor teachers:

Reflecting on my own beliefs and values as a mentor and advocating for preparing for future teachers as a benefit for teachers, mentors and the public-school system… It has strengthened our school’s mentors through improved teacher quality with continual professional learning. Our mentors are equipped with an extensive professional toolkit with a raised awareness of practice though the strategies taught by ACU (Harper).

And

Efficiency of communication, time-saving (cutting down of frequently asked mentor questions), but more importantly quality materials to set mentors up for success to provide quality practicum experiences for their PSTs (Logan).

Growth in professional networking

A partnership between ACU and just one school grew over the years into a vibrant community involving 19 schools where practitioners worked towards the common goal of improving the placement experiences of pre-service teachers with a view to them being “professional ready.” When the teachers were asked, how has the professional networking across the partnership grown? Typical of the comments was:

The partnership also addressed the need for our school to be developed as a PEX Hub school with training and resources to be shared with other schools in our community of practice. The major need was to provide consistent high-quality professional experiences for PSTs and supervising teachers … to equip classroom teachers as skilled mentors with experiences and resources, professional mentoring training and a community of practice to develop their skills. The need for a Hub of expert schools to be developed as a lighthouse in best practice with training and resources to be shared with other schools in our community of practice. The mentor training met the need and could be delivered across our network of schools consistently (Jay).

And:

Regular school visits and online forums have allowed for professional networking amongst the community of schools. Collegial trust is established between school leaders and the university lead, as well as the Director and DoE corporate personnel. Of recent, co-constructed strategies are implemented as a response to the national workforce teacher shortages. (Riley)

The growth of the partnership and the subsequent networking, was attributable to additional factors, including delivering context-specific training, resource sharing, reaching out, maintaining contact, peer support and networking for a common cause.

We could share knowledge and support teacher mentors in our own and other schools in the network with resources to build their expertise in professional experience … scaffolds, reflection forms, feedback models were developed and shared. This met the need for consistent high-quality experiences for PST’s (Harper).

New understandings

This research is grounded in such socio-cultural theories of learning and meaning making that occur collectively and individually within this community (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Within this CoP, members have discussed their growing varying levels of expertise and experience, their roles have spanned from peripheral participant to expert, and they have demonstrated that they are driven by their shared purpose and commitment to nurture and produce profession-ready graduates, through the sharing of ideas, strategies, the development of solutions and innovative initiatives to create a unique and contextual knowledge base and resources.

It is also through the shared experience that we can bridge the gap between the theoretical perspectives presented by academic staff at university, the practice of teaching and the experiences of the mentor teacher as all members come to understand common language, experiences and characteristics of the culture of the environments for all involved. Whilst universities and schools are complex social environments with their own communities of practice, both university and teaching staff are open and willing to join and be accepted by the CoP that is focused on the preparation of profession ready graduates.

In pursuing their interest, they engaged in joint activities and discussions, helped each other, and shared information (Domain). The foundation of the partnership was trust and care about their standing with each other and ability to learn from one another (Community). In order to develop shared practice that included the development of resources, artefacts, tools and solutions to problems (Practice) (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991).

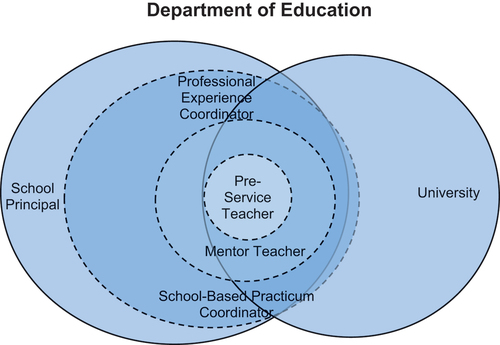

provides a diagrammatic overview of the study where the university, school participants and the dimensions of the CoP are identified. This is the sixth iteration (2021), which is the present-day structure of the ACU-SSPS PEX Hub partnership. Evident in this figure is the closeness with which the university based Professional Experience Coordinator collaborates with the school-based Practicum Coordinator with the School Principal and the University. Evident in this figure are the dotted rings that demonstrate the fluidity of the relationship – the movement in and out of each of the components and roles (Wengner-Trayner & Wenger_trayner, Citation2014). This figure gives greater appreciation to the complex landscape that supports several communities of practice that interact with one another and that ultimately support the pre-service teacher to become profession ready graduates. This has been made possible as the professional experience coordinator and the school-based practicum coordinator worked collaboratively and professionally to support mentor teachers in their work with the pre-service teachers while they each also belong to a broader landscape of communities of practice. This change between at the commencement of the project and at the sixth iteration, indicates that the boundaries between the individual communities of practice have become highly penetrable, permitting legitimate participation by all members. In this way, the practices that have been developed are the result of the CoP itself.

Conclusion

This research study provides evidence that an appreciation of the landscape of the range of communities of practice in school-university partnerships contributes to a CoP designed specifically to promote graduate ready teachers. Further, it provides evidence that the evolving theory of communities of practice (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2014) does indeed extend to a landscape of communities of practices. This makes the use of the theory complex as researchers must be mindful of the full landscape and how these various interacting communities of practice assist or diminish efforts to establish, manage and sustain school-university partnerships. Targeted attention needs to accompany the collaborative efforts of each of the school and university partnerships to ensure a hierarchical interaction is not developed. Instead, the participants who formed the school university partnership, discussed in this paper, came willing to learn from each other and to grow together. This prevented the potentially limiting components of the partnership as each partner recognised that existing communities of practice, either in the their school or university setting, making sure they did not direct the way the school university partnership was to operate.

The CoP framework, specifically Domain: mutual engagement, Community: joint enterprise and Practice: shared repertoire, influenced and shaped the design of the school-university PEX Hub partnerships and the learning processes through emphasis on professional agency, negotiated competences and the changed and continuing development of professional relationships of those within the CoP (Pyrko et al., Citation2019). Consequently, the partnership grew exponentially to become a thriving community with 19 Hub schools. Over 300 teachers from these schools have become mentors through NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) accredited ACU Mentoring Professional Learning and more than 500 pre-service teachers have participated in the ACU-SSPS partnership. The partnership has allowed for the formation of a CoP within and across the landscape of school system and ACU communities of practice. The process has resulted in a shared purpose focusing on priorities including graduate teacher readiness and contributions to the professional learning of all stakeholders. This finding is consistent with earlier Australian research (Salter & Halbert, Citation2019). Further, the partnership also focuses on developing a mentoring programme and support culture of professional experience and teacher leadership development that ensures quality of practice in the use of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Professional Standards) (APSTs). As such, the CoP framework ensured an informed understanding of how the partnership would be designed and how the community would interact, learn from each other, form relationships, participate, engage in their roles and co-construct knowledge. The outcome of this project that commenced with one school and ACU and that quickly grew to 19 schools, is indicative of the robust, respectful and professional collaboration that is occurring within the ACU-SSPS partnership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Miriam Tanti

Miriam Tanti is an experienced educator who works with teachers, schools, and school systems. Her research explores the impact of school and university partnerships on the formation of high-quality teachers.

Chrissy Monteleone

Chrissy Monteleone is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education at the ACU. Her research focuses on critical mathematical thinking capabilities, building communities of practice and mentoring initial teacher education students.

Monica Wong

Monica Wong is a mathematics educator who also facilitates partnerships with Sydney primary schools to implement after school maths clubs.

References

- Ambrosetti, A., Knight, B. A., & Dekkers, J. (2014). Maximising the potential of mentoring: A framework for pre-service teacher education. Mentoring & Tutoring, 22(3), 224. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2014.926662

- Aprile, K., & Knight, B. (2019). The WIL to learn: Students’ perspectives on the impact of work-integrated learning placements on their professional readiness. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(5), 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1695754

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2015). Australian professional standards for teachers. http://www.aitsl.edu.au/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers/standards/list.

- Babic, M. (2019). Schooling, democracy and the quest for wisdom: Partnerships and the moral dimensions of teaching. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(5), 611–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1675390

- Bahr, N., & Mellor, S. (2016). Building quality in teaching and teacher education. Australian education review No. 61. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Billett, S. (2015). Readiness and learning in health care education. The Clinical Teacher, 12(6), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12477

- Buckley, H., Steinert, Y., Regehr, G., & Nimmon, L. (2019). When I say … community of practice. Medical Education, 53(8), 763–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13823

- Carroll, T., Fulton, K., & Doerr, H. (2010). Team up for 21st century teaching and learning: What research and practice reveal about professional learning. National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

- Council of Australian Governments (COAG). (2008). National partnership agreement on improving teacher quality. Canberra, Australia.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487105285962

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2022). Report of the quality initial teacher education review.

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration: A commitment to action. Retrieved June 20, 2023, from https://www.dese.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration

- Jones, M., Hobbs, L., Kenny, J., Campbell, C., Chittleborough, G., Gilbert, A., Herbert, S., andRedman, C. (2016). Successful university-school partnerships: An interpretive framework to inform partnership practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.006

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Le Cornu, R. (2016). Professional experience: Learning from the past to build the future. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2015.1102200

- MacLeod, M., Lindsey, A., Ulrich, C., Fulton, T., & John, N. (2008). The development of a practice-driven, reality-based program for rural acute care registered nurses. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39(7), 298–304. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20080701-03

- Manton, C., Heffernan, T., Kostogriz, A., & Seddon, T. (2021). Australian school–university partnerships: The (dis) integrated work of teacher educators. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(3), 334–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1780563

- McNamara, O., Murray, J., & Jones, M., Eds. (2013). Workplace learning in teacher education: International practice and policy, Vol. 10. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7826-9_1

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians.

- New South Wales Department of Education. (2016), Professional experience framework statement. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/ps-nsw/media/documents/Sample_agreement.pdf. Last updated 2021.

- Nguyen, D. T. (2020). Exploring the learning experience of esl/efl pre-service teachers in a new practicum model: A case study.

- NSW DEC, NSW Institute of Teachers, & BOS NSW. (2013). Great teaching, inspired learning - a blueprint for action. Ebook. Retrieved June 20, 2023, from https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/wcm/connect/b3826a4c-7bcf-4ad1-a6c9-d7f24285b5e3/GTIL+A+Blueprint+for+Action.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2019 technical report

- Pyrko, I., Dorfler, V., & Eden, C. (2019). Communities of practice in landscapes of practice. Management of Learning, 50(4), 482–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507619860854

- Salter, P., & Halbert, K. (2019). Balancing classroom ready with community ready: Enabling agency to engage with community through critical service learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1497771

- Teacher education ministerial advisory group. (2014). Action now: Classroom ready teachers. Department of Education.

- Walker, R., Morrison, C., & Hay, I. (2019). Evaluating quality in professional experience partnerships for graduate teacher employability. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 118–137. 118. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2019vol10no1art791

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2014). Learning in a landscape of practice. In E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, & B. Wenger-Trayner (Eds.), Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315777122

- Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Introduction to communities of practice. https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/