ABSTRACT

Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) have become a vital part of the global regulatory agenda. For some, MSIs are a way to reassert democratic control and accountability over corporations. For others, they merely represent the private capture of regulatory power. Based on an analysis of three MSIs in an issue area where the prospects for politicisation seem particularly promising, the regulation of Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs), this article engages the debate about the political dynamics of MSIs. Using a three-face approach to depoliticisation that embraces its governmental, societal and discursive dimensions, the article shows that these governance arrangements have fostered depoliticisation along all three dimensions: The launch of MSIs has not only enabled states to evade a binding licencing regime; they have also diverted NGO attention into more amicable venues and turned the privatisation of security from a normative into a narrow, technical issue.

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs)Footnote1 have become an increasingly prominent regulatory approach to improve the social and environmental performance of transnational corporations—a kind of “default option” for all kind of policy areas and actors (Baumann-Pauly et al. Citation2016, 1–2). There is considerable enthusiasm about the potential of MSIs as a mechanism for taming, even democratising the power of transnational corporations. For Palazzo and Scherer, MSIs present a new form of “politicization of the corporation” (Citation2006, 72). They provide inclusive, deliberative forums where diverse stakeholders organise collectively to discuss and define the rights and responsibilities of corporations. If carefully designed, MSIs can reduce the democratic deficit in global governance (Baumann-Pauly et al. Citation2016). For their critiques, however, MSIs are extremely limited as spaces for deliberation and contestation given the substantial power differentials between stakeholder groups (Carr Citation2015; Moog, Spicer, and Böhm Citation2015). They also fear that MSIs, under the banner of corporate social responsibility, are an attempt to free companies from the grip of state regulation once and for all.

This article addresses the unresolved question about the political dynamics of MSIs. To this end, it draws on the recent literature on politicisation/depoliticisation in global governance (Fawcett et al. Citation2017a; Stone Citation2017; Wood and Flinders Citation2014). Processes of politicisation/depoliticisation capture the essence of what advocates and opponents deem desirable or troublesome about MSIs, even if they do not explicitly frame their arguments in these conceptual terms. The present analysis focuses on multi-stakeholder regulation of an issue area where the potential for politicisation of the corporation seems particularly strong: the field of private security. Scholars concur that the increasing reliance on Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) has curtailed the prospect of transparency, accountability and a meaningful public debate (Avant and Sigelman Citation2010; Leander Citation2011). Confidentiality clauses contained in their contracts often shield PMSCs from public scrutiny and simple facts about the industry are hard to come by (Avant and Sigelman Citation2010; Michaels Citation2004). This lessens informed consent on the part of both citizens and the legislative and is likely to inhibit an open, public discussion. In short, PMSCs reinforce a tendency toward depoliticisation of an issue area where secrecy and other tools to evade public scrutiny abound (Avant and Sigelman Citation2010; Leander Citation2011). MSIs, as some hope, could reverse this trend by opening up a policy field that is per se not very transparent. As such, they are a showcase for scrutinising the (false) promises of the multi-stakeholder model in general.

By providing a theoretical explanation and empirical illustration of the potential implications of MSIs, the article seeks to contribute to three academic debates. First, the paper offers a contribution to what should be seen as a much broader analysis of what MSIs do to and mean for “the political”, one that moves beyond issues of performance toward their performativity (see Leander Citation2012). Studies that cover MSIs in areas as diverse as environmental politics, social rights, private security, sustainable agriculture, human rights and Internet governance have already made us aware that these tri-sectoral governance arrangements do more than just facilitating cooperation between the different stakeholders to solve complex global governance problems. Among those critical voices are scholars who investigate the disciplining power of MSIs, i.e. their ability to regulate the behaviour of stakeholders (Boström and Hallström Citation2010; Joachim and Schneiker Citation2015). Other authors express concern that MSIs might reproduce dominant neo-liberal ideas of state regulatory retrenchment and a preference for “soft law” approaches over binding multilateral treaties (Carr Citation2015; Moog, Spicer, and Böhm Citation2015). In a range of studies, the ability of multi-stakeholder forums to accommodate forms of input legitimacy has been put into question; they claim that MSIs exhibit asymmetric power relations and deepen the North South divide as they merely serve the interest of corporate actors (Cheyns and Riisgaard Citation2014). In the same vein, scholars have pointed out the exclusionary tendencies of these arrangements which, in their view, a priori limit the range of voices and regulatory options to be considered (Cheyns and Riisgaard Citation2014; Dany Citation2014; Schneiker and Joachim Citation2018). The following analysis adds to these critiques by unpacking the concrete mechanisms through which PMSC-related MSIs enact depoliticisation. So far, the analytical value of the concept of depoliticisation for analysing the significance of MSIs in world politics has remained unexplored and deserves further elaboration. More specifically, the article contends that to fully grasp the political implications of MSIs, we have to attend to three co-existing dimensions of politicisation/depoliticisation: governmental, societal and discursive. They offer a baseline to highlight the unique political effects of MSIs in the field of private security. The point is not that those have not been studied before, but these issues have not been approached in terms of a comprehensive analysis.

Second, the article engages the debate about depoliticisation in the realm of private security governance. According to the critical security studies literature, the commodification and marketisation of security is linked to depoliticisation in many ways—for instance, by turning security from a public into an excludable and divisible good (Krahmann Citation2008) or by furthering a narrow technocratic and militarised interpretation of security, which crowds out alternative understandings of security and how it should be delivered (Abrahamsen and Williams Citation2011, 71; Leander and van Munster Citation2007, 208f.). The present paper contends that this depoliticising logic is also inscribed in and perpetuated by a host of regulatory arrangements, including multi-stakeholder initiatives which, only recently, have begun to permeate the field of private security. The key claim here is that MSIs—which are assumed to revive choice, agency and deliberation—are, in fact, “anti-politics machines” (Ferguson Citation1990), fostering depoliticisation in at least three ways: First, MSIs have blurred the public character of regulation which usually places the responsibility to approve of and oversee the use of PMSCs in the hands of elected representatives. In multi-sectoral governance schemes, the role of the state is reversed. It is no longer the central rule-making authority, but a consumer of private military and security services who may use its buying powers to enforce voluntary regulations. It is important to note that this development does not take place against the state, but has been initiated or promoted by state officials in the UK (and elsewhere). They have deliberately leveraged their participation in MSIs to avoid the political and economic costs of a binding licencing regime. Second, MSIs have become mechanisms of capture of critical civil society voices as they divert limited resources away from public advocacy into more cooperative forms of engagement. Third, MSIs have narrowed the discursive space around PMSCs by a) transforming the question of how we want to organise armed force (and related security functions) from a normative into a narrow, technical issue; b) marginalising alternative policy options for regulating the industry; and c) framing the industry as a “normal” and “necessary” feature of international politics. This “here-to-stay” point of view has made it increasingly difficult to object to their presence in conflict zones and to imagine alternatives to their employ.

The three mechanisms of depoliticisation discussed here are also of relevance for the global governance literature more generally. To begin with, the concept of governmental depoliticisation offers a new perspective to conceptualise the recent shift from hard, public and hierarchical to soft, private, hybrid and partnership-oriented forms of governance. While the mainstream literature suggests that governments typically lack capabilities to deal efficiently or effectively with complex policy problems, leading them to develop or support these new governance arrangements (Schäferhoff, Campe, and Kaan Citation2009, 456), the following analysis reveals an additional rationale: the passing away of responsibility and accountability from government. Seen this way, orchestration via transnational governance initiatives is a depoliticising strategy that allows public actors to been seen as “doing something” while still avoiding the associated costs of binding regulation. Moreover, the paper invites us to critically interrogate on the oft-cited role of civil society as driver of depoliticisation processes. The case of PMSC-related MSIs suggests that, contrary to one of the claims about it, civil society actors can contribute to depoliticisation when being enrolled into MSIs or other transnational governance initiatives that follow the dominant partnership paradigm in global governance. Participation can have a quietening effect, pulling NGOs into less disruptive behaviours. Finally, by attending to the discursive dimension of depoliticisation in MSIs, this article sheds light on the exclusionary effects of such new forms of networked governance. Reliance on MSIs and other transnational governance initiatives can result in a form of discursive hegemony that excludes certain understandings and definitions of an issue and how it should be regulated while naturalising others. These exclusionary tendencies, as has been argued elsewhere (Schneiker and Joachim Citation2018), owe to the “club governance” character of such initiatives: in spite of their insistence on inclusiveness, they limit participation to stakeholders that take consensual and seemingly pragmatic positions, leaving little room for alternative views to be expressed.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section discusses the concept of depoliticisation as a political act performed by MSIs in at least three ways: 1) the crowding out of governmental controls (governmental depoliticisation); 2) the taming of NGO critique (societal depoliticisation); and 3) the narrowing down of the scope of the debate (discursive depoliticisation). The second section draws out the methodological toolkit to account for the assumptions made above. The third section examines to what extent the three “faces” of depoliticisation are present in MSIs that set standards and oversight mechanisms for PMSCs: the Montreux Document, the International Code of Conduct for Security Service Providers (ICoC) and the ANSI PSC.1 standard. The final section concludes with a summary of my findings and avenues for further research.

2. Unpacking depoliticisation in multi-stakeholder governance

In the broadest sense, depoliticisation designates “the set of processes […] that remove or displace the potential for choice, collective agency, and deliberation around a particular political issue” (Fawcett et al. Citation2017b, 5). It involves an attempt, whether deliberate or not, to place an issue beyond dispute, into the realm of “finitude”, “inevitability”, “fatality”, “necessity”, “destiny” and “resignation” (Jenkins Citation2011, 159). Burnham’s seminal article on Blair’s New Labour governing strategy to frame otherwise contentious neo-liberal reforms as inevitable stands for an emerging body of research that critically questions the premise that “there is no alternative” (2001). Depoliticisation in this sense is associated with acquiescence to dominant policy paradigms and institutions, which may spur political apathy and public disengagement. By contrast, (re-)politicisation refers to the reverse process of lifting an issue (back) into the sphere of public deliberation, decision making and contention “where previously it was not” (Wood and Flinders Citation2014, 154). It entails questioning what is taken for granted or perceived to be necessary, politically or morally (Jenkins Citation2011, 159).

Beyond this minimum definition, however, there is disagreement on the specific ways in which depoliticisation takes place, the sites and levels at which it occurs and whether or not depoliticisation presupposes intentionality. In an attempt to bring analytical order into this complex conceptual terrain, Wood and Flinders (Citation2014) have developed a three-face approach to depoliticisation that pulls together the various, often disconnected debates and literatures on depoliticisation. They distinguish three faces of depoliticisation which feature different conceptualisations of “the political”: (1) governmental depoliticisation, or the outsourcing of political decision-making to independent, quasi-public and/or private bodies; (2) societal depoliticisation, or the shifting of issues off the agenda of public deliberation; (3) and discursive depoliticisation where a single discourse with a single or narrow framing of an issue remains. The remainder of this section maps the three faces of depoliticisation and explains how they can be applied in the context of MSIs.

Governmental depoliticisation is closely associated with the “first wave” (Hay Citation2014) of depoliticisation scholarship which focuses on the withdrawal of the state from the direct control of a range of governance functions (Wood and Flinders Citation2014, 156). This retreat involves the transfer of responsibility to international organisations, public-private partnerships, bureaucracies or sub-national bodies, which places “at one remove” (Burnham Citation2001, 128) the public character of decision-making. This strand of literature displays striking analogies to principle-agent theory which conceives of delegation as a rational strategy, a form of statecraft through which cost-sensitive governments attempt to deflect responsibility for unpopular and contested policy decisions (Buller and Flinders Citation2005; Burnham Citation2001; Flinders and Buller Citation2006). This emphasis on the “tactics and tools” of depoliticisation invites us to critically interrogate the ways in which depoliticisation can benefit, or preserve, the interests of some actors rather than others. Much of the criticism directed against MSIs falls along these lines. After all, it is often the state that has deliberately turned away from traditional regulatory approaches in favour of new forms of collaborative governance and soft law. As Pauly (Citation2001, 77) notes,

The fact that actual governments routinely obfuscate their final authority … is no accident. Blurring the boundary lines between public and private, indeed, is part of an intentional effort to render opaque political responsibility for the wrenching adjustments entailed in late capitalist development.

Governmental depoliticisation rests on a narrow conceptualisation of politics as the realm of state control and regulation (Jenkins Citation2011, 158). The second, societal face of depoliticisation, by contrast, shifts our attention to civil society as the locus of depoliticisation processes. Wood and Flinders (Citation2014, 159) define societal depoliticisation as the decline of issues as salient matters in societal debates. Conceived this way, a depoliticised issue would exhibit very little or none public debate to the point that societal actors—social movements, NGOs or the media—stop referencing it (Wood and Flinders Citation2014, 159). Interestingly, these groups are usually identified as the driving forces behind politicisation processes. The literature on transnational activism has made this abundantly clear. NGOs, in particular, are valued for their ability to raise awareness, frame issues, engage in public shaming campaigns and politicise what has previously escaped public attention and/or contestation (Carpenter Citation2007; Jaeger Citation2007; Joachim Citation2007). They lift issues into the public domain by demonstrating “that a given state of affairs is neither natural nor accidental”, but the cause of human actions (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998, 19). This causal attribution, in turn, makes an issue amenable to (regulatory) action and opens up the possibility of change.

Paradoxically, the very same act of awareness-raising and agenda-setting that may lift an issue up into the “realm of contingency and action” has also the potential to (at least temporarily) depoliticise it. Once an issue becomes the focus of regulatory action, it is transformed “from a matter of contingent choice into one of prevailing […] regulation” (Landwehr Citation2017, 61). At this stage, an issue is deemed “settled” and “resolved” in the interests of all citizens which typically curbs the potential for further political mobilisation (Hay Citation2014, 309; Volk Citation2018, 10). The inclusion of NGOs in multi-stakeholder processes is likely to reinforce this trend. It can reduce the space for contention when NGOs channel their scarce organisational resources away from critical campaigning into more amiable venues (Baur and Schmitz Citation2012; Trumpy Citation2008). Therefore, participation in MSIs comes at the risk of silencing critique and a waning of societal politicisation (Joachim and Schneiker Citation2015, 198).

The discursive dimension of depoliticisation is concerned less with the amount of attention that societal actors pay to an issue than with how an issue is defined or framed (Wood and Flinders Citation2014); it focuses on the role of language to depoliticise certain issues. Wood and Flinders define discursive depoliticisation as any speech act which narrows down the debate towards a single interpretation of an issue, conveys the impression of fatalism, and conceals, negates or removes contingency (Citation2014, 161). This can involve a discursive move to frame an issue in technical, managerial, or commonsensical terms, as something that does not concern a much broader global constituency. Going back to Habermas’ (Citation1971) work on technology and the depoliticisation of the public sphere, there is now a substantial literature that deals with the link between depoliticisation and technicization. Stone (Citation2017, 101), for instance, observes a scientification of global governance, understood as “a set of discourses that generate particular forms of knowledge and causal definitions of global problems around which policy solutions … are organized”. This assumption resonates with scholars who have highlighted the depoliticising effect of the various performance assessments, codes of conduct, benchmarks and best practices in the field of private security governance (Krahmann Citation2017; Leander Citation2016). These initiatives are based on an apolitical, technical understanding of security as risk management which is best to be managed by a narrow technocratic set of commercial security professionals and thus “kept aloof of politics” (Leander Citation2011, 2259). They also exclude alternative governance practices and meanings from consideration, for example “questions of justice or social and political reforms” (Abrahamsen and Leander Citation2016, 23; Krahmann Citation2017). This article expands upon these criticisms by exploring if and how MSIs contribute to discursive depoliticisation.

3. Methodology

How can we empirically assess the degree of depoliticisation by MSIs? Since depoliticisation, by definition, presupposes that in issue has been politicised before, this paper conducts a before-after-analysis, comparing the degree of regulatory pressure, the level of societal attention and the discourse around PMSCs prior to and after the launch of MSIs. Regarding the first face, governmental depoliticisation, this paper scrutinises the degree of regulatory pressure that PMSCs have faced in the United Kingdom (UK) prior to and after the establishment of the Montreux Document, the ICoC, and the PSC.1 standard. The UK constitutes what one might call a “crucial case” (Levy Citation2008) to probe my assumptions about the link between MSIs and governmental depolicisation. Being home to some of the largest and most prominent PMSCs worldwide, the UK wields considerable influence in terms of regulating the industry. The British government has also been the first among its European peers to launch a wider debate on the prospects of regulating PMSCs with the publication of the Green Paper in 2002. Back then, “government and parliamentary opinion clearly favoured a stronger regulatory regime as opposed to more laissez-faire approaches”, as summarised by Bohm, Senior and White (Citation2012, 309). This raises the threshold for depoliticisation to occur along the first dimension. Therefore, the UK’s attempt to relax governmental control of PMSCs once the Swiss Initiative and the ICoC process took off should be a strong pointer for the depoliticising effect of MSIs. If the basic assumption of governmental depoliticisation as a set of “tactics and tools” is borne out, we would expect the UK government to promote multi-stakeholder regulation in order to reduce political/economic costs of regulation and/or to increase its autonomy.

That said, the British case is likely to differ from other national and regional contexts. More specifically, the much studied Anglo-Saxon PMSC markets are more deeply penetrated by neoliberal norms than continental European countries, for example (Kruck Citation2014). These norms have provided a rationale for adopting voluntary or hybrid regulatory regimes such as government-backed codes of conduct or certification standards that combine market and sovereignty-based approaches to regulating the PMSC industry and work at national and international levels simultaneously (MacLeod Citation2015). Consequently, the UK (and US) neoliberal markets are likely to exhibit a higher proclivity for governmental depoliticisation than less privatisation-friendly countries.

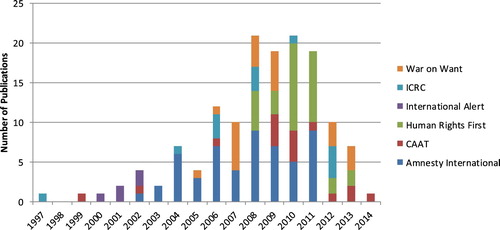

Societal depoliticisation has been defined as the decline of issues as salient matters in societal debates. A relatively straightforward measure for the visibility or salience of an issue in societal debates is to quantitatively assess the agenda-setting activity of NGOs before and after the launch of MSIs, proxied by the annual share of documents referring to PMSCs in their campaign material. The strength of assessing agenda-setting and NGO attention cycles rather than relying on media analysis, as most studies have, is that is allows us to draw direct causal inferences about the depoliticising effect of MSIs on NGOs to the extent that membership in and exclusion from such a network may constrain their behaviour (Avant and Westerwinter Citation2016, 26). Therefore, I have collected all publicly available advocacy material from five NGOs between 1998 and 2014: Amnesty International, Campaign against Arms Trade (CAAT), Human Rights First, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), International Alert and War on Want. Selection of these organisations was driven by two main considerations: In order to qualify for the analysis, an NGO must have championed the issue of PMSCs in the first place (issue adoption). Simply put, if an issue has not been brought to attention by an NGO, there is no baseline to assess the depoliticising effect of MSIs on this agenda-setting activity. Issue adoption occurs when an NGO names a given state of affairs and references it in its campaign materials (Carpenter Citation2007, 103, fn. 6). Out of this “parent population” of NGOs, cases were chosen on the basis that they cover both organisations that have been members of at least some of the MSIs considered here (Amnesty International, Human Rights First, ICRC) and those that have tabled alternative regulatory arrangements and who did not partake in these arrangements (CAAT, International Alert, War on Want). This allows for a differential analysis of the depoliticising effect of MSIs on both “insiders” and “outsiders”. To further corroborate my assumption that NGO participation in MSIs inhibits activism on PMSCs, I have conducted seven expert interviews with NGO representatives who took part in at least one of the three MSIs identified above. Interviews lasted between 30–90 min and were analysed by means of “thematic coding”. Coding for themes is “a way to categorize a set of data into an implicit topic that organizes a group of repeating ideas” (Saldaña Citation2013, 176). The purpose of this coding procedure is to identify key concerns and challenges related to NGO participation in MSIs, fitting into either the category “politicisation” or the category “depoliticisation”.

When it comes to discursive depoliticisation, the article examines changes in the way PMSCs are defined or framed. Empirically, this calls for a comparative analysis of the spectrum of all existing views on PMSCs and the positions expressed in MSIs (Schneiker and Joachim Citation2018, 9). This would include the UN Working GroupFootnote2 which has been a key player in the PMSC debate and a vocal critic of these firms. Until recently it has maintained that PMSCs were merely mercenaries and should be banned altogether (Percy Citation2007a). However, with the emergence of the Swiss-based MSIs, its relevance in the discursive and regulatory landscape has been decidedly diminished, giving way to more pragmatic positions on the issue (Leander Citation2016, 60; Percy Citation2012; Prem Citation2020).Footnote3 To complement preliminary findings from the Working Group, I will confine my analysis to the five NGOs presented above: Amnesty International, CAAT, Human Rights First, the ICRC, International Alert, and War on Want. While not being representative of the entire spectrum of existing positions on the issue, these NGO voices nevertheless give a first rough estimate on possible discursive shifts in the way PMSCs are depicted. Not unlike the Working Group, these organisations have mobilised through reports and advocacy campaigns to denounce malpractices in the PMSC industry. If a similar pattern of discursive depoliticisation was to be observed, this would lend force to my initial suggestion that MSIs are “depoliticising tools”. To look for recurrent patterns and discontinuities in the way PMSCs are depicted in societal discourse and MSIs, I have conducted a qualitative content analysis of the advocacy material that the five NGOs have published on PMSCs on the one hand and the three legal documents that are the result of multi-stakeholder processes on the other: the Montreux Document, the ICoC and the PSC.1 standard. How exactly did they frame the industry, which solutions did they suggest and which of these concerns have entered into MSIs?

4. Depoliticisation in practice

Decision-making

The UK has been the first among European governments to explore options for regulating the PMSC sector following the political fallout of the “Arms to Africa affair” which had brought to light that the British PMSC Sandline International had delivered 35 tons of arms to Sierra Leone—in contravention of a UN weapons embargo and with the alleged approval of the UK government. In response to the debacle, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) drew up a Green Paper in 2002 in which it set out six potential routes for the regulation of UK-based PMSCs: 1) a complete ban of companies; 2) a ban limited to recruiting individuals to take up military service abroad; 3) a licencing regime for contracts that would cover military and security services abroad, 4) a requirement for PMSCs to register with the government and to notify it of contracts for which they were bidding; 5) a general licence for the company itself (rather than individual contracts); and 6) self-regulation through a trade association (FCO Citation2002). While the Green Paper process was set up in an open fashion, there was considerable consensus that self-regulation alone was not sufficient to control the industry (Bohm, Senior, and White Citation2012; White Citation2016). “This would not meet one of the main objectives of regulation, namely to avoid a situation where companies might damage British interests” (FCO Citation2002, 26). Subsequent parliamentary reports joined in this tune, expressing a strong preference for a government-backed licencing regime (Foreign Affairs Committee Citation2002).

In spite of this initial verve, the debate was cut off in the run up to the war in Iraq which had started just a year after the Paper was released and led the government to shift its priorities and resources (Bohm, Senior, and White Citation2012, 317; Percy Citation2012, 950f.). In 2005, the issue seemed to resurface when a special-unit was established within the FCO to prepare new proposals for regulation (Hirst Citation2005), but ultimately none eventuated. Interestingly, the silence that followed the 2005 review coincided with the launch of the Swiss Initiative which took off in 2006 and ended in 2008. Launched by Switzerland and the ICRC, it was mainly directed at states to remind them of their obligations under international humanitarian law if they hire, export or host PMSCs. Although it was an essentially state-driven process, industry actors, academics and NGOs were consulted through four expert meetings between 2006 and 2008. The outcome of this process was the Montreux Document, a restatement of the existing international legal obligations and good practices of states. Although, states are explicitly encouraged to adopt legislative and other measures to fulfil their obligations under international humanitarian law, the Montreux process has become a smokescreen, letting the UK government of the hook of domestically regulating the industry at a time when no government department was particularly keen to handle the issue. The difficulty of implementing and monitoring licences with a transnational application has been one major argument against a licencing regime (Foreign Affairs Committee Citation2008, 62). Another factor weighing in was the government’s increasing reliance on PMSCs in Iraq as of 2003, which meant that, by the time the Government came to reconsider the issue of regulation, it had considerably less incentives to come up with binding controls. Thus, recognising both the economic and political costs of binding its hands domestically, the UK Government readily defaulted to using “soft” tools of influence, including the Montreux Document. According to White (Citation2016), it is bitter irony that the UK government may be guilty of hiding behind the soft-law facade of the Montreux Document when, in fact, the latter is based on states having hard (that is, binding) positive obligations to prevent human rights abuse by private actors.

The UK government did not reconsider the issue until 2009 when it announced a public consultation to seek the view of different stakeholders on how to move forwards with its 2002 proposals (FCO Citation2009a). By that time, the Montreux Process was finalised and the ICoC process already under way, which set the terms of the subsequent debate. The signing of the Montreux Document and the launch of the ICoC process meant that there was already an institutional structure in place around which the government could advance its own policy agenda, namely a government-backed system of self-regulation and international standards (FCO Citation2009b, 14–15). Thus, the FCO prefaced the consultation by stating that it was in favour of a twin-track approach of “working with the UK industry to promote high standards through a code of conduct agreed with and monitored by the Government … and raising of international standards of PMSCs through international cooperation” (FCO Citation2009a, 9). These recommendations were premised on the view that the PMSC industry played a “positive and legitimate role globally” (FCO Citation2009a, 5) and should not be “over burdened” (FCO Citation2009b, 6). Binding regulation such as a licencing regime would unduly constrain the competitiveness of the British PMSC industry and deprive it of contracts for services of considerable value. According to a PMSC representative, “the British government at the moment is very seized by supporting any bit of British industry that seems to be working and making money”.Footnote4 This enthusiastic support for the success of the industry extended to Whitehall’s refusal to impose any sort of binding regulation on it, let alone a ban. Hence, despite substantial discord among the participants of the consultation, the government ultimately settled on its earlier proposal: soft law initiatives rather than statutory controls (Bohm, Senior, and White Citation2012, 311; FCO Citation2010). This “hands-off approach to governance” is not unique to the field of private security, but states’ mounting dependence on business investment, employment and export revenue, combined with a new climate of austerity following the financial crisis in 2008, have led governments to look for less expensive and less interventionist options of regulation in the area of business and human rights, including MSIs (Fuchs Citation2005; Jerbi Citation2012). Whether they participate directly in setting human rights standards for business, promote them politically or financially, or act in their capacity as “mega consumers” of private goods and services who may use their buying power to enforce those standards, governments lacking the political will and funding to carry out their traditional regulatory function can leverage their non-negligible role as “orchestrators” (Abbott et al. Citation2015; Hale and Roger Citation2014) to convey the impression that they remain in charge and control.

In the field of private security, the main pieces of this voluntary system are the ICoC/ICoCA and the PSC.1 standard. The ICoC is an industry code of conduct that is directly applicable to PMSCs. By signing the Code, signatory companies voluntarily agree to abide by the principles and norms of international human rights law. To lend the Code teeth, an oversight institution, the ICoC Association (ICoCA) was established in 2013. The UK had been actively involved in the development of the ICoCA which is now responsible for overseeing if PMSCs are fulfilling their obligations under the Code—through certification, performance assessment and third party complaints. At the same time, the UK government enlisted the ADS Security in Complex Environments Group (SCEG), a British industry association, and the UK Accreditation Service to develop voluntary standards and certifications for British PMSCs (Bellingham Citation2011). In September 2012, the FCO (Simmonds Citation2012) ultimately settled on SCEG’s “unreserved recommendation … that PSC1 be accepted as the basis for our UK national standard” (SCEG Citation2013). PSC.1 is a certification standard that seeks to operationalise the best practices outlined in the Montreux Document and the ICoC by providing auditable criteria for PMSC management. As a result, the government has almost entirely stepped down as the central rule-making-, monitoring and enforcement authority vis-à-vis the industry. Instead, its role is now limited to “us[ing] its leverage as a key buyer of PMSC services to promote compliance with the International Code” (Bellingham Citation2011). This “lever” rests on the assumption that (public) clients of private military and security services can ensure that self-regulation has “teeth” by awarding contracts to those companies that have signed up to the ICoC or have underwent certification to PSC.1. As an industry representative confirms, “it’s the market that really is the key influencer to the majority of companies”.Footnote5 Regulation, then, is depoliticised in the sense that it is no longer the focus of legislative or governmental action, but a concern for the market. The limitations of such an approach have been well documented (O'Brien, Mehra, and Meulen Citation2016). According to Krahmann (Citation2016), the ability of public authorities to influence standards in the industry through their consumer behaviour is circumscribed by a range of factors, including difficulties to monitor contracting behaviour, dependence on specific companies, long-term contracts and personal networks between government representatives and PMSCs, all of which make it difficult for public consumers to leverage their enforcement capacity.

Agenda setting

This section gives an overview of how PMSCs have featured in NGO discourse from the end of the 1990s until 2014. The number of NGO advocacy material on this issue and its distribution over time is used as an indicator for gauging the degree of public attention given to PMSCs and its change or stability over time. Does the proliferation of MSIs correlate with a decline of NGO coverage of private security, as the depoliticisation hypothesis would lead us to expect, or can we observe a constant level of NGO output over time?

Overall, the level of attention that NGOs have payed to the issue remains slightly marginal in total numbers, with a total of 148 NGO publications being devoted to PMSCs, and is marked by a wave-like increase in relative terms (). This up and down over the 16-year period of investigation can be divided into three phases: 1) a politicisation phase starting in the late 1999 when NGOs first took up the issue on their advocacy agenda and “lifted it up” into the public consciousness; 2) a culmination phase from 2008 until 2011 which is marked by a sharp increase in the number of NGO publications; and 3) a normalisation or depoliticisation phase from 2012 onwards.

PMSCs are a relatively unknown commodity during the early period of investigation but gain increasing prominence as of 2004 (frequency=7), in the wake of the war in Iraq which has seen not only a drastic increase in the number of contractors deployed alongside the coalition forces, but also a series of scandals involving PMSC contractors, including the Abu Ghraib prison scandal and contractors randomly shooting at civilian cars in Baghdad. These incidents have warranted closer NGO scrutiny, with PMSCs becoming increasingly visible on the NGO agenda. The 2007 Nisour Square scandal, when Blackwater contractors opened fire in a Baghdad market, killing seventeen civilians, have spurred reinvigorated interest. The level of NGO coverage reaches an all-time high in the year following the incident (f = 22) and remains relatively stable until 2011 (culmination phase). For NGOs, Nisour Square has become a catalytic event, a wake-up call to remind the public and decision-makers of scale of the problem. It has become an “extraordinary example of the ordinary in Iraq—a case where heavily armed private security convoys used lethal force against real or perceived threats on Iraqi streets” (Human Rights First Citation2008, 5). However, the upward trend in NGO coverage has been reversed since 2012 (f = 10) and a cautious extrapolation of the numbers of 2014 indicates that NGO attention is going to decrease even further (depoliticisation phase). Human Rights First substantially scaled down its coverage and Amnesty International ceased active campaigning on PMSCs altogether. How can we explain this decline after the “attention boom” of the years before?

One reason for the decreasing output on the issue might be the industry’s successful attempt to rebrand itself as legitimate and essentially benign player (Joachim and Schneiker Citation2012; Prem Citation2020). This has made it increasingly difficult for NGOs to advocate on the issue and employ anti-mercenary arguments which used to be relatively powerful in the 1990s/2000s. Prioritisation is another possible explanation. With limited organisational and financial resources, the NGO community has to prioritise and trade one attention-getting issue for another. This can explain why, overall, the PMSC issue has remained on the fringe of NGO attention, at least in total numbers. The withdrawal of the coalition troops from Iraq and Afghanistan is likely to have added to this trend, leading NGOs to move to more pressing agendas as PMSCs became a less visible and salient issue. This explanation, however, oversees that less coverage does not necessarily amount to less attention. NGOs like Amnesty and Human Rights First, for example, have refocused their advocacy effort around regulatory initiatives for the PMSC industry. In fact, the decreasing level of NGO attention from 2012 onwards coincides with the development of the ICoC Association which has drawn in a number of NGOs, including organisations such as Human Rights First, Human Rights Watch, Control PMSC, Global Policy Forum and ICAR. There were involved in the initial stages of drafting the Code, which was ultimately agreed upon at a conference in September 2010 and joined efforts to prepare a draft version of the future ICoC. The more NGOs followed the ICoC process, the less effort they put in critical campaigning against PMSCs. “Time spent by civil society organisations following the Code process and advocating within the framework of the Code”, as an NGO representative explained, “is arguably time not spent doing critical work on PMSCs” (Pingeot Citation2014, 16). In an organisational environment defined by limitations in budget and organisational capacity, MSIs have become a source of distraction, forcing many NGOs, even the larger ones, to prioritise: either partake in MSIs or spend time and money on critical advocacy work. As confirmed by my interview partners, partaking in MSIs is a costly endeavour as NGOs have to dedicate scarce resources to attend meetings and to closely follow the Code process.Footnote6 Long-term commitment in the ICoCA where NGOs sit in the governing board is considerably more resource-intensive than one-off consultation within the Swiss Initiative. This also explains why partaking in the Montreux processes did not have the same depoliticising effect as the ICoC initiative. The latter has effectively side-lined the prospects for a meaningful societal debate by diverting NGO attention and energy into multi-stakeholder settings. As we may infer from this example, societal depoliticisation varies with different types of MSIs. It is likely to be stronger for more institutionalised MSIs in which participating stakeholders (here: NGOs) can play an active role in rule-setting and take governance positions inside the standard organisation—i.e. those that in Fransen and Kolk’s (Citation2007) terms feature broad versus narrow inclusiveness in their governance structure. Moreover, the effect is more pronounced for so-called “insiders”, i.e. those NGOs joining multi-stakeholder processes, whereas “outsiders” such as War on Want have maintained a stable (and even increasing) level of coverage (see ). They did not face the same dilemma as many of their NGO peers, being in a position to channel their scarce organisational resources exclusively to campaigning activities against PMSCs.

Socialisation processes within MSIs are another factor accounting for the waning NGO activism as of 2012. Since representatives of the two sectors interacted directly and more frequently with one another, they also found themselves in new roles. Resuming his experience in the ICoC Association, an NGO representative explained that, “when [collaboration with the corporate sector] becomes something so regular and so part of your work that it shapes your identity, it might make a difference”.Footnote7 According to my interview partners, membership in MSIs did require all sides to internalise some unwritten rules of conduct: to engage respectfully with each other, to empathise with others’ views and to search for compromise. This credo has driven many NGOs to restrain their rhetoric and demands: “It’s purely my understanding that [name of an NGO] sort of took that stance that ‘we don’t want to be deeply involved in this because than it means that we can’t say how much we hate it’, you know [laughing]?”Footnote8, as a participant of the Code process resumed the dilemma that many NGOs faced once they got involved in MSIs. While few of my interviewees from the NGO sector were as explicit, several of them, however, stressed the importance of preserving mutual trust between the different stakeholder groups—something that critical campaign against the industry was likely to erode.Footnote9 To be sure, that does not imply that conflict ceases to exist inside these initiatives. However, it is confined to the narrow context of MSIs and therefore less visible. Today, private security is hardly discussed outside these expert circles. This is problematic insofar as these MSIs have brought together fairly like-minded actors who share a common understanding about how the industry should be governed while opposing views and actors, particularly those calling for a ban on PMSCs or mandatory regulation, have been marginalised (Schneiker and Joachim Citation2018). As a consequence, the diversity of regulatory options that would be discussed in MSIs was limited from the outset, leaving little room for alternative views to be expressed. This point will be explored in more detail below.

Framing

Discursive depoliticisation occurs when the debate around an issue becomes technocratic and/or narrowly focused on a single interpretation of (and solution to) an issue where previously competing framings existed. Conceived this way, it is possible to distinguish three ways in which MSIs contribute to discursive depoliticisation. First, MSIs turn the privatisation of security from a normative into a purely technical matter. A closer look at how PMSCs were framed in NGO discourse and which of these issues have moved forward into MSIs is revealing. It shows that the space for normative reasoning has decreased. Throughout the politicisation and culmination phases identified above, the debate around PMSCs has revolved around four major themes: the question of whether or not PMSCs contribute to the security of their clients and local populations (Amnesty International Citation2012); the degree to which PMSCs are under legal and democratic control (Amnesty International Citation2006a: 45; Human Rights First Citation2008); the way they affect the state’s monopoly over the use of force (War on Want and CAAT Citation2006, 2); and whether or not PMSCs can provide a proper justification for their participation in security governance, one that transcends any ulterior, self-interested motivation (War on Want Citation2008; War on Want Citation2007). These concerns, however, have given way to an apolitical reading of PMSCs. The PSC.1 standard, for example, vaguely refers to human rights violations as “undesirable or disruptive event[s]” that can be easily “minimized” and “managed” (ASIS International Citation2012, 3). NGOs, by contrast, used a considerably bolder language. They spoke of “torture” (Amnesty International Citation2004b; ICRC Citation2012, 13; Human Rights First Citation2008; War on Want and CAAT Citation2006), “ill treatment” (Amnesty International Citation2004a; Beerli Citation2012), “abuse” (cf. Amnesty International Citation2006a; ICRC Citation2012, 13; Human Rights First Citation2008; War on Want and CAAT Citation2006), and “wanton violence” on civilians (Human Rights First Citation2010, 2). While the management of risks is a technical, almost mechanical enterprise that can be easily kept aloof of politics, heinous crimes like those mentioned above cannot; they call for robust state regulation. The Montreux Document, the ICoC and PSC.1, in contrast, tend to focus on technical issues such as the proper selection and vetting of PMSC personnel, training of subcontractors, rules specifying when the use of force is permissible, procedures for the management of weapons and ammunitions and the specification of the services that PMSCs may carry out.

At the same time, there has been virtually none reflection on whether PMSCs should be allowed to use force and get involved in a business with life-and-death consequences in the first place. Instead, the three initiatives start out from the premise that PMSCs are per se relatively unproblematic as long as the rules, standards and good practices they specify are complied with. The Swiss Initiative is emblematic in that regard. It takes note of “the reality on the ground” and gives guidance on what rules apply if PMSCs operate in situations of armed conflict without prejudging their use in any way (ICRC and FDFA Citation2008, 5, 41). The highly politicised controversy about whether states should, in principle, hire PMSCs was bracketed out:

Like all other armed actors present on the battlefield, PMSCs are governed by international rules, whether their presence and activities are legitimate or not. The Montreux Document follows this humanitarian approach. It does not take a stance on the question of PMSC legitimacy. It does not encourage the use of PMSCs nor does it constitute a bar for States who want to outlaw PMSCs. (DCAF Citation2015, 40)

Second, MSIs have marginalised alternative options for regulation. While calls for an outright ban of PMSCs were never particularly widespread, NGOs, the UN Working Group and legislative bodies have considered a number of options short of a legal proscription. Ever since the revelations of the “Arms to Africa” affair, NGOs have called for a licencing regime that would proscribe “illegitimate and undesirable activities” and subject all PMSC services to “prior parliamentary and public scrutiny” (CAAT Citation2009; Lilly Citation2000, 26; War on Want and CAAT Citation2006, 17). In the United States (US), Congress explored the possibility of insourcing certain military and security services. The Stop Outsourcing Security Act sought to reverse the decision to outsource training of troops and police, guarding convoys, repairing weapons, administering military prisons and performing military intelligence (Schakowski Citation2007). The thrust of the Swiss Initiative, the ICoC and PSC.1, by contrast, is conservative. They revolve around permissive controls of the industry by mitigating, improving and reforming PMSC conduct. “What’s more important is not the fact that companies are doing this”, as a PMSC representative explains, “but that they are doing it in a proper and professional fashion”.Footnote10 NGO participation in MSIs follows the same logic. According to an interview partner from the NGO sector, most advocacy groups “don’t want to get rid of them [PMSC]”, but they “want to make them better companies”.Footnote11 Framing the discussion about improved accountability in terms of how PMSCs can be permissibly used is a way of diverting energy, attention and imagination away from alternatives to their employ; it shifts the debate away from a concern about the actor, its rightfulness and legitimacy, to one about the management of certain activities.

Third, MSIs reinforce and bolster the status quo of security contracting. Even if they do not officially endorse the presence of PMSCs, these initiatives take the industry as a given, as “something that is here to stay”. The opening statement of the ICoC, for instance, acknowledges that PMSCs “play an important role in protecting state and non-state clients engaged in relief, recovery, and reconstruction efforts, commercial business operations, diplomacy and military activity” (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft Citation2010, Art. 1: emphasis mine). The Montreux Document shares this assessment by framing the industry as “an indispensable ingredient of military undertakings” (FDFA Citation2015, 5; emphasis mine). In this sense, it fuels and sustains the impression that PMSCs are a normal and unavoidable feature of international politics which is unlikely to go away any time soon. Such taken-for-grantedness constitutes a powerful form of depoliticisation. It turns PMSCs into an indisputable given and places them beyond the possibility of dissent. As a result, groups like War on Want or the UN Working Group on Mercenaries, which have traditionally taken a more critical and prohibitive posture than their colleagues in MSIs, are fighting an uphill struggle to get their voices heard. Their positions and claims are discarded as “unrealistic”, “not helpful”, “useless” (Brooks and Chorev Citation2008, 127).Footnote12 The shifting fortunes of the UN Working Group is a case in point: Its initial effort to extend the orthodox anti-mercenary norm to PMSCs has alienated companies and their state customers, pushing them to pursue alternative venues such as the Swiss initiative and the ICoC process both of which display a markedly favourable attitude towards these companies. As a result, the Working Group has been almost completely side-lined on this issue and is struggling to come back to relevance.Footnote13 Discursive depoliticisation, as these examples suggests, is premised upon a general consensus within MSIs which is secured through mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion—limiting participation only to those groups and organisations that have accepted the neoliberal paradigm (e.g. the premise that PMSCs are here to stay and therefore should be permissively controlled and not banned) from the outset, while excluding those with opposing positions. Consequently, MSIs give way to a consensual, one-sided framing of an issue, leaving little room for alternative views to be expressed.

5. Conclusion

This paper has set out to analyse whether MSIs live up to the promise of politicising an issue area that is traditionally fraught with secrecy and a lack of accountability: the field of private security. The analysis suggests that this prospect is meagre. Rather, MSIs are “anti-politics machines” that crowd out of governmental controls, reduce the space for contestation, and turn the quest for accountability into a narrow, technical issue. These findings imply a shift in theorising about the role of MSIs in global governance. They put into question the empathic view of MSIs as new mechanisms for democratising the corporation.

The implications of these trends for the global governance literature are no less considerable; they reinforce and add to a much broader depoliticising move that scholars have diagnosed for other policy areas. Specifically, MSIs are representative of a “hands-off” approach to governance which, only recently, has begun to permeate the field of international security (Leander and van Munster Citation2007, 203). The ICoC and PSC.1 have introduced a market-based logic into the regulation of the industry to the effect that states no longer act as the central enforcing authority but as consumers of PMSC services. This effect is particularly subtle because, unlike most non-security related MSIs, active government involvement in the Swiss Initiative, the ICoC process and PSC.1 may give the appearance that states remain in charge and control. However, depoliticisation is not only a governmental phenomenon; it also permeates civil society which is usually credited with politicising issues that had either been ignored or considered objects of technical regulation by states or international institutions. The concerns raised by NGOs, as some have hoped, could be a “reassertion of democratic controls over the use of force” where states have relaxed their traditional regulatory responsibility vis-à-vis the industry (Percy Citation2007b, 27). This potential remains largely untapped once MSIs turn “critics” into “committed partners”. While scholars have diagnosed a similar development in other issue areas, the increasing dependency of NGOs on private security services for their own protection and funding from governments who maintain contracts with these firms are likely to magnify the quietening effect of societal depoliticisation in PMSC-related MSIs. Finally, my findings add nuance to existing studies that have pointed out the exclusionary character of these initiatives by tracing the discursive shifts that follow processes of stakeholder selection and exclusion. As the empirical analysis has illustratively suggested, confining participation to an inner circle of “experts” that share the idea that PMSCs are here to stay triggers discursive depoliticisation to the extent that alternative perspectives on the desirability of outsourcing security and the need for binding regulation are systematically excluded.

Because of the likely repercussions of these findings, further research is needed to analyse the prospects for re-politicising private security which, according to Landwehr (Citation2017, 61), is the “yardstick for deliberative and democratic qualities” of any governance system. The potential for re-politicisation seems all the more important as the industry is in constant flux. PMSCs have rushed to fill new profitable gaps beyond the large-scale expeditionary wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) specialists in the US’ drone war and as “cyber soldiers”. Yet, the Montreux Document, the ICoC, and PSC.1 are still concerned with regulating the last incarnation of the industry, namely the type of armed security companies common in Iraq and Afghanistan. As long as the industry keeps evolving, it seems imperative that an open debate continue and that regulation be changed by new circumstances.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the 11th Pan–European Conference on International Relations in Barcelona, September 2017 and a research colloquium at the University of Kiel. I would like to thank the editors of Global Society, two anonymous reviewers, and Alexander Gould, Elke Krahmann, Hilde van Meegdenburg, Andrea Schneiker, and Maria Stern for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Berenike Prem

Berenike Prem is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Bremen, Germany. Her research concentrates on non-state actors’ involvement in security governance, with a focus on the activities of Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs), and anticipatory norm-building in global environmental and security policy. Her most recent publications include “Private Military and Security Companies as Legitimate Governors: From Barricades to Boardrooms” (Routledge, 2020) and a book chapter in “Security Privatization. How Non-security-related Private Businesses Shape Security Governance” (Springer, 2018).

Notes

1 MSIs can be defined as voluntary multi-sectoral networks that bring together public actors, business and civil society representatives whose aim is to regulate a specific issue area by voluntary norms and rules, including management standards, labels and codes of conduct (Bäckstrand Citation2006).

2 The full title is Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries as a Means of Violating Human Rights and Impeding the Exercise of the Right of Peoples to Self-Determination.

3 Moreover, some of most recent literature suggests that even the UN Working Group suggestions have become more moderate over time (Bures and Meyer Citation2019; Krahmann Citation2012).

4 Personal interview with industry representative, London, May 2014.

5 Telephone Interview with PMSC Representative. June 2014.

6 Personal interview with NGO representatives, Washington DC, March 2014; telephone interview with NGO representative, May 2014.

7 Telephone interview with NGO representative, February 2018.

8 Personal interview with PMSC representative, Reston, VA, April 2014.

9 Personal interview with NGO representatives, Washington DC, March 2014; telephone interview with NGO representative, February 2018.

10 Telephone interview with PMSC representative, June 2014.

11 Personal interview with NGO representative, Washington DC, March 2014.

12 A similar view has been expressed by one of my interview partners from the PMSC industry, Washington DC, March 2014.

13 The Group’s effort to establish an international binding instrument – the UN Draft Convention – has stalled in part because it lacks the support of major states.

References

- Abbott, Kenneth W., Philipp Genschel, Duncan Snidal, and Bernhard Zangl. 2015. “Orchestration: Global Governance Through Intermediaries.” In International Organizations as Orchestrators, edited by Kenneth W. Abbott, and Philipp Genschel, 3–36. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Abrahamsen, Rita, and Anna Leander. 2016. “Introduction.” Chap. 1 In Routledge Handbook of Private Security Studies, edited by Rita Abrahamsen, and Anna Leander, 1–7. London: Routledge.

- Abrahamsen, Rita, and Michael C. Williams. 2011. Security Beyond the State. Private Security in International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Amnesty International. 2004a. “Call For Corporate Accountability in Iraq.” Accessed November 13 2013. http://web.archive.org/web/20041019214211/http://takeaction.amnestyusa.org/action/display/wacmoreinfo.asp?item=10897.

- Amnesty International. 2004b. “Taking on the Titans.” Accessed November 13 2013. http://web.archive.org/web/20041010060752/http://www.amnestyusa.org/business/taking_on_the_titans.html.

- Amnesty International. 2006a. “Dead on Time – Arms Transportation, Brokering and the Threat to Human Rights.” Accessed November 13 2018. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/68000/act300082006en.pdf.

- Amnesty International. 2006b. “USA: Below the Radar: Secret Flights to Torture and ‘Disappearance’.” Accessed November 14 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20110907041021/http://amnesty.org/en/library/asset/AMR51/051/2006/en/b543c574-fa09-11dd-b1b0-c961f7df9c35/amr510512006en.pdf.

- Amnesty International. 2012. “The Costs of Outsourcing War.” Accessed January 16 2013. http://www.amnestyusa.org/our-work/issues/business-and-human-rights/private-military-and-security-companies.

- ASIS International. 2012. ANSI/ASIS PSC.1-2012 Management System for Quality of Private Security Company Operations - Requirements with Guidance. Alexandria.

- Avant, Deborah, and Lee Sigelman. 2010. “Private Security and Democracy: Lessons From the US in Iraq.” Security Studies 19 (2): 230–265. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2010.480906

- Avant, Deborah, and Oliver Westerwinter. 2016. The New Power Politics: Networks and Transnational Security Governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Baumann-Pauly, Dorothée, Justine Nolan, Auret van Heerden, and Michael Samway. 2016. “Industry-Specific Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives That Govern Corporate Human Rights Standards: Legitimacy Assessments of the Fair Labor Association and the Global Network Initiative.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (4), 1–17.

- Baur, Dorothea, and Hans Peter Schmitz. 2012. “Corporations and NGOs: When Accountability Leads to Co-Optation.” Journal of Business Ethics 106 (1): 9–21. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1057-9

- Bäckstrand, Karin. 2006. “Multi-stakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Rethinking Legitimacy, Accountability and Effectiveness.” European Environment 16 (5): 290–306. doi: 10.1002/eet.425

- Beerli, Christine. 2012. “A Humanitarian Perspective on the Privatization of Warfare. September 14."International Committee of the Red Cross, Accessed October 15 2013. http://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/statement/2012/privatization-war-statement-2012-09-06.htm.

- Bellingham, Henry. 2011. “Written Ministrial Statement. Promoting High Standards in the Private Military and Security Company Industry. June 21."Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Accessed February 5 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/promoting-high-standards-in-the-private-military-and-security-company-industry–2.

- Bohm, Alexandra, Kerry Senior, and Adam White. 2012. “The United Kingdom.” Chap. 15 In Multilevel Regulation of Military and Security Contractors: The Interplay Between International, European and Domestic Norms, edited by Mirko Sossai, and Christine Bakker, 309–328. Oxford: Hart.

- Boström, Magnus, and Kristina Tamm Hallström. 2010. “NGO Power in Global Social and Environmental Standard-Setting.” Global Environmental Politics 10 (4): 36–59. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00030

- Brooks, Doug, and Matan Chorev. 2008. “Ruthless Humanitarianism. Why Marginalizing Private Peacekeeping Kills People.” In Private Military and Security Companies: Ethics, Policies and Civil-Military Relations, edited by Marina Caparini, Deane-Peter Barker, and Andrew Alexandra, 116–131. New York: Routledge.

- Buller, Jim, and Matthew Flinders. 2005. “The Domestic Origins of Depoliticisation in the Area of British Economic Policy.” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 7 (4): 526–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-856x.2005.00205.x

- Bures, Oldrich, and Jeremy Meyer. 2019. “The Anti-Mercenary Norm and United Nations’ Use of Private Military and Security Companies.” Global Governance 25 (1): 77–99. doi: 10.1163/19426720-02501002

- Burnham, Peter. 2001. “New Labour and the Politics of Depoliticisation.” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 3 (2): 127–149. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.00054

- CAAT. 2009. “Response from the Campaign Against Arms Trade to the Consultation on Private Military and Security Companies.” Accessed November 13 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20120806235706/www.caat.org.uk/resources/publications/government/FCO_PMSC_consultation_July09.pdf.

- Carpenter, R. Charli. 2007. “Setting the Advocacy Agenda: Theorizing Issue Emergence and Nonemergence in Transnational Advocacy Networks.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (1): 99–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00441.x

- Carr, Madeline. 2015. “Power Plays in Global Internet Governance.” Millennium 43 (2): 640–659. doi: 10.1177/0305829814562655

- Cheyns, Emanuelle, and Lone Riisgaard. 2014. “The Exercise of Power Through Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives for Sustainable Agriculture and its Inclusion and Exclusion Outcomes.” Agriculture and Human Values 31 (3): 409–423. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9508-4

- Dany, Charlotte. 2014. “Janus-Faced NGO Participation in Global Governance: Structural Constrains for NGO Influence.” Global Governance 20 (3): 419–436. doi: 10.1163/19426720-02003007

- DCAF. 2015. “The Montreux Document. The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces.” Accessed November 13 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20170824113938/www.dcaf.ch/Project/The-Montreux-Document.

- Dingwerth, Klaus. 2005. “The Democratic Legitimacy of Public-Private Rule Making: What Can We Learn From the World Commission on Dams?” Global Governance 11 (1): 65–83. doi: 10.1163/19426720-01101006

- Fawcett, Paul, Matthew Flinders, Colin Hay, and Matthew Wood. 2017a. Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fawcett, Paul, Matthew Flinders, Colin Hay, and Matthew Wood. 2017b. “Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance.” In Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance, edited by Paul Fawcett, Matthew Flinders, Colin Hay, and Matthew Wood, 3–27. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- FCO. 2002. “Private Military Companies: Options for Regulation."Foreign and Commonwealth Office. HC 577, Accessed February 05 2014. http://psm.du.edu/media/documents/national_regulations/countries/europe/united_kingdom/united_kingdom_white_paper_on_regulatory_options_for_private_military_companies_2002-english.pdf.

- FCO. 2009a. Consultation Document. Consultation on Promoting High Standards of Conduct by Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) Internationally. London: Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

- FCO. 2009b. Impact Assessment on Promoting High Standards of Conduct by Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) Internationally. London: Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

- FCO. 2010. “Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs): Summary of Public Consultation Working Group. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. April 2010.” Accessed February 4 2014. http://www.caat.org.uk/issues/corporate-mercenaries/pmsc-working-group-summary-060410.pdf.

- FDFA. 2015. “The Montreux Document." Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Accessed July 10 2015. https://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/fdfa/foreign-policy/international-law/international-humanitarian-law/private-military-security-companies/montreux-document.html.

- Ferguson, James. 1990. The Anti-Politics Machine: “Development,” Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Flinders, Matthew, and Jim Buller. 2006. “Depoliticisation: Principles, Tactics and Tools.” British Politics 1 (3): 293–318. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bp.4200016

- Foreign Affairs Committee. 2002. “Private Military Companies. Ninth Report of Session 2001–2002."House of Commons, HC 922, Accessed September 6 2017. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmfaff/922/922.pdf.

- Foreign Affairs Committee. 2008. “Human Rights Annual Report 2007. Ninth Report of Session 2007–08. HC 533."The Stationery Office Limited, Accessed February 5 2014. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmfaff/533/533.pdf.

- Fransen, Luc W., and Ans Kolk. 2007. “Global Rule-Setting for Business: A Critical Analysis of Multi-Stakeholder Standards.” Organization 14 (5): 667–684. doi: 10.1177/1350508407080305

- Fuchs, Doris. 2005. “Commanding Heights? The Strength and Fragility of Business Power in Global Politics.” Millennium - Journal of International Studies 33 (3): 771–801. doi: 10.1177/03058298050330030501

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1971. Technik und Wissenschaft als “Ideologie”. Edition Suhrkamp. 5. Aufl., 51.-65. Tsd ed. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Hale, Thomas, and Charles Roger. 2014. “Orchestration and Transnational Climate Governance.” The Review of International Organizations 9 (1): 59–82. doi: 10.1007/s11558-013-9174-0

- Hay, Colin. 2014. “Depoliticisation as Process, Governance as Practice: What Did the ‘First Wave’ Get Wrong and Do We Need a ‘Second Wave’ to Put it Right?” Policy & Politics 42 (2): 293–311. doi: 10.1332/030557314X13959960668217

- Hirst, Clayton. 2005. “Dogs of War to Face New Curbs in Foreign Office Crackdown.” The Independent on Sunday, 13 May, 3.

- Human Rights First. 2008. “Private Security Contractors at War. Ending the Culture of Impunity.” Accessed June 9 2013. http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/08115-usls-psc-final.pdf.

- Human Rights First. 2010. “Written Testimony for the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan. Hearing on “Are Private Security Contractors Performing Inherently Governmental Functions”.” Accessed June 9 2013. http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/CWC-Hearing_Written_Testimony.pdf.

- ICRC. 2012. “The Grey Zone.” Red Cross Magazine 2012 (03): 12–15.

- ICRC, and FDFA. 2008. “The Montreux Document on Pertinent International Legal Obligations and Good Practices for States Related to Operations of Private Military and Security Companies During Armed Conflict.” Accessed February 10 2016. https://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/icrc_002_0996.pdf.

- Jaeger, Hans-Martin. 2007. ““Global Civil Society” and the Political Depoliticization of Global Governance.” International Political Sociology 1 (3): 257–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-5687.2007.00017.x

- Jenkins, Laura. 2011. “The Difference Genealogy Makes: Strategies for Politicisation or How to Extend Capacities for Autonomy.” Political Studies 59 (1): 156–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00844.x

- Jerbi, Scott. 2012. “Assessing the Roles of Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives in Advancing the Business and Human Rights Agenda.” International Review of the Red Cross 94 (887): 1027–1046. doi: 10.1017/S1816383113000398

- Joachim, Jutta. 2007. Agenda Setting, the UN, and NGOs: Gender Violence and Reproductive Rights. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- Joachim, Jutta, and Andrea Schneiker. 2012. “New Humanitarians? Frame Appropriation Through Private Military and Security Companies.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 40 (2): 365–388. doi: 10.1177/0305829811425890

- Joachim, Jutta, and Andrea Schneiker. 2015. “NGOS and the Price of Governance: The Trade-Offs Between Regulating and Criticizing Private Military and Security Companies.” Critical Military Studies 1 (3): 185–201. doi: 10.1080/23337486.2015.1050270

- Keck, Margaret E., and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. Activists Beyond Borders. Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Krahmann, Elke. 2008. “Security: Collective Good or Commodity?” European Journal of International Relations 14 (3): 379–404. doi: 10.1177/1354066108092304

- Krahmann, Elke. 2012. “From ‘Mercenaries’ to ‘Private Security Contractors’: The (Re)Construction of Armed Security Providers in International Legal Discourses.” Millennium - Journal of International Studies 40 (2): 343–363. doi: 10.1177/0305829811426673

- Krahmann, Elke. 2016. “Choice, Voice, and Exit: Consumer Power and the Self-Regulation of the Private Security Industry.” European Journal of International Security 1 (01): 27–48. doi: 10.1017/eis.2015.6

- Krahmann, Elke. 2017. “From Performance to Performativity: The Legitimization of US Security Contracting and its Consequences.” Security Dialogue 48 (6): 541–559. doi: 10.1177/0967010617722650

- Kruck, Andreas. 2014. “Theorising the Use of Private Military and Security Companies: A Synthetic Perspective.” Journal of International Relations and Development 17 (1): 112–141. doi: 10.1057/jird.2013.4

- Landwehr, Claudia. 2017. “Depoliticization, Repoliticization, and Deliberative Systems.” In Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance, edited by Paul Fawcett, Matthew Flinders, Colin Hay, and Matt Wood, 40–67. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leander, Anna. 2011. “Risk and the Fabrication of Apolitical, Unaccountable Military Markets: The Case of the CIA ‘Killing Program’.” Review of International Studies 37 (5): 2253–2268. doi: 10.1017/S026021051100043X

- Leander, Anna. 2012. “What do Codes of Conduct Do? Hybrid Constitutionalization and Militarization in Military Markets.” Global Constitutionalism 1 (1): 91–119. doi: 10.1017/S2045381711000074

- Leander, Anna. 2016. “The Politics of Whitelisting: Regulatory Work and Topologies in Commercial Security.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34 (1): 48–66. doi: 10.1177/0263775815616971

- Leander, Anna, and Rens van Munster. 2007. “Private Security Contractors in the Debate About Darfur: Reflecting and Reinforcing Neo-Liberal Governmentality.” International Relations 21 (2): 201–216. doi: 10.1177/0047117807077004

- Levy, Jack S. 2008. “Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25 (1): 1–18. doi: 10.1080/07388940701860318

- Lilly, Damian. 2000. “The Privatization of Security and Peacebuilding: A Framework for Action."International Alert, Policy and Advocacy Department, Accessed October 30 2013. http://psm.du.edu/media/documents/reports_and_stats/ngo_reports/intlalert_lilly_private_security_peacebuilding_2000.pdf.

- MacLeod, Sorcha. 2015. “Private Security Companies and Shared Responsibility: The Turn to Multistakeholder Standard-Setting and Monitoring Through Self-Regulation-‘Plus’.” Netherlands International Law Review 62 (1): 119–140. doi: 10.1007/s40802-015-0017-y

- Michaels, Jon D. 2004. “Beyond Accountability: The Constitutional, Democratic, and Strategic Problems with Privatizing War.” Washington University Law Quarterly 82 (3): 1001–2004.

- Moog, Sandra, André Spicer, and Steffen Böhm. 2015. “The Politics of Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives: The Crisis of the Forest Stewardship Council.” Journal of Business Ethics 128 (3): 469–493. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-2033-3

- O'Brien, Claire Methven, Amol Mehra, and Nicole Vander Meulen. 2016. “Public Procurement and Human Rights: A Survey of Twenty Jurisdictions."International Learning Lab on Public Procurement and Human Rights, Accessed August 12 2019. https://www.hrprocurementlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Public-Procurement-and-Human-Rights-A-Survey-of-Twenty-Jurisdictions-Final.pdf.

- Palazzo, Guido, and Andreas Georg Scherer. 2006. “Corporate Legitimacy as Deliberation: A Communicative Framework.” Journal of Business Ethics 66 (1): 71–88. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9044-2

- Pauly, Louis W. 2001. “Global Finance, Political Authority, and the Problem of Legitimation.” In The Emergence of Private Authority in Global Governance, edited by Rodney Bruce Hall, and Thomas J. Biersteker, 76–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Percy, Sarah. 2007a. Mercenaries. The History of a Norm in International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Percy, Sarah. 2007b. “Morality and Regulation.” In From Mercenaries to Market: The Rise and Regulation of Private Military Companies, edited by Simon Chesterman, and Chia Lehnardt, 11–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Percy, Sarah. 2012. “Regulating the Private Security Industry: A Story of Regulating the Last War.” International Review of the Red Cross 94 (887): 941–960. doi: 10.1017/S1816383113000258

- Pingeot, Lou. 2014. “Contracting Insecurity. Private Military and Security Companies and the Future of the United Nations."Global Policy Forum and Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, Bonn/New York, Accessed 04/23/2014, http://www.globalpolicy.org/images/pdfs/GPFEurope/PMSC_2014_Contracting_Insecurity_web.pdf.

- Prem, Berenike. 2020. Private Military and Security Companies as Global Governors: From Barricades to Boardrooms. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- SCEG. 2013. “About the SCEG.” Accessed February 5 2014. https://www.adsgroup.org.uk/pages/19813174.asp.