ABSTRACT

When stable and reliable practices were disrupted due to the global pandemic, university teachers were forced to promptly adapt. Through Q sorting and deliberative dialogues, this study reports how university teachers shifted their normative values concerning successful future learning environments during the first year of the pandemic. Results provide valuable insight into first-person accounts of lived experiences and suggest recommendations for the next phase of academic development, including a stronger focus on hybridity and student responsibility. In general, participants held more pedagogical discussions in times of crisis and emerged as more reflective practitioners.

Introduction

Because academic development is situated in highly dynamic contexts (Huijser et al., Citation2020) and responsive to societal change, it has historically been engaged in a process of gradual and hesitant changes (Ramsden, Citation2003). However, the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us that change can happen immediately. Overnight, university teachers were advised to work from home via digital media. In March 2020, the term emergency remote teaching (Hodges et al., Citation2020) emerged to describe the common struggles of university teachers, especially those without any particular interest in digital tools and methods. Without any managerial strategies or specific training, university teachers adapted with great diversity to the sudden shift from face-to-face to fully digital teaching (Sim et al., Citation2020). Otherwise stable and reliable practices within higher education institutions were disrupted, and this reportedly increased workloads and stress (Rapanta et al., Citation2020). The uncertain conditions during the global pandemic, in comparison to those in January 2020, provided an excellent opportunity to investigate university teachers’ conceptions (Entwistle et al., Citation2000; Schwieler & Ekecrantz, Citation2011) and their lived experiences as persons, academics, and members of an institution (Sutherland, Citation2018).

Instead of asking university teachers about their descriptive beliefs about how successful learning environments (LEs) are, we focus on their normative values regarding how LEs ought to be. This concept has received relatively little attention in higher education research (Schwieler & Ekecrantz, Citation2011). The future-oriented character of this study led us to the concept of LEs found in Abualrub et al. (Citation2013). Based on a comprehensive literature review, Abualrub and colleagues conclude that, most often, LEs are seen simply as pedagogical settings. Few contributions apply an organizational or networked perspective.

As academic developers, we were inspired by the practice of deliberative academic development (Fremstad et al., Citation2020) to facilitate ‘active and inclusive debates’ (Kandlbinder, Citation2007, p. 56). In the sense of a ‘carefully balanced consideration of different alternatives’ (Solbrekke & Sugrue, Citation2020, p. 10), a preparatory card ranking activity called Q sorting scaffolded deliberations with university teachers.

We contribute new knowledge about how university teachers’ conceptions of successful LEs shifted across time and present a methodological tool for deliberative academic development. Our paper responds to two research questions:

In what way have university teachers’ conceptions about successful learning environments changed during the first year of the global pandemic?

In what ways is Q sorting, a card ranking activity, helpful for deliberative academic development?

Theoretical framework and methodological approach

Holistic academic development

Similar to the predominance of a pedagogical perspective in research on LEs (Abualrub et al., Citation2013), literature on academic development has primarily focused on improving teaching and enhancing student learning (Sugrue et al., Citation2018; Sutherland & Grant, Citation2016). In her seminal publication, Sutherland (Citation2018) calls for Academic Developers (ADs) to broaden their focus and thereby take on a more holistic approach. In doing so, she urges ADs to better understand and support the development of the whole of the academic role, which includes not only teaching duties, but also research, service, administration, and leadership. With regard to values, power, and positioning within an organization, ADs are asked to focus on the whole institution in their role as brokers between various stakeholder groups such as students, academics, and university managers, and also between disciplines and departments (Sugrue et al. Citation2018; Sutherland, Citation2018). To reach faculty, it is necessary to blend and negotiate collegial with managerial authority as part of accepting the wholeness of the institution and the broker role of ADs (Stigmar, Citation2008). Finally, Sutherland calls for more attention to and respect for individual academics’ ontologies and epistemologies. With regard to expected tensions and differences between university teachers’ disciplinary traditions and new research-based suggestions by ADs, a widened focus on the whole person further contributes to a more holistic approach to academic development, which tries to serve all members of university communities.

To sum up, the need for a broader focus, as suggested by Sutherland (Citation2018), is something we recognize as experienced ADs. By engaging with university teachers as persons who juggle different academic roles in the complexities of a whole institution, the present study applies a holistic understanding of academic development (Sutherland, Citation2018). Our findings inform ADs’ work to serve university teachers in the future.

Q sorting for deliberative academic development

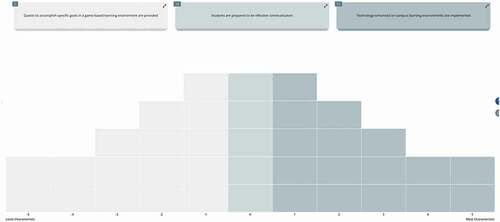

ADs’ position within a holistic approach to academic development is demanding but offers great potential to build bridges (Fremstad et al., Citation2020). We engaged university teachers in dialogues to inform academic development, learn about their lived experiences, and construct knowledge about their personal normative values about successful future LEs. Organizing conversations, which mediate between participants and potentially build consensus, have been termed deliberative academic development by Kandlbinder (Citation2007). More important than reaching agreement is the opportunity for individuals to carefully and critically reflect on a range of alternatives. A technique that has been successfully applied to deliberations on policy issues is Q sorting (Niemeyer et al., Citation2013). In Q methodology (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012), participants are instructed to rank a collection of cards (called a ‘Q sample’) on a distribution grid (see for an example). Q methodology is an established approach to investigating issues of subjectivity in a wide range of contexts and fields and has been gaining in popularity in educational research (Lundberg et al., Citation2020). In the field of higher education, Q methodology has, for example, been used to explore emotions in the workplace (Woods, Citation2012) or students’ approaches to studying (Godor, Citation2016).

Figure 1. Empty distribution grid used in t2. Cards on top are placed on the grid through drag-and-drop.

The present investigation took place at a relatively young Swedish university with a high percentage of first-generation academics. Participants were sampled in a purposive way. We aimed to cover as much ground as possible by including respondents from various disciplines, departments, microcultures, and stages in their professional careers. There was no requirement for ethics approval of the project because no sensitive personal data were collected. Participants were recruited via email request, informed about their voluntary participation, and assured confidentiality at all times. Fifteen university teachers (see ) were engaged in a Q sorting activity in January 2020 (t1) and a follow-up in November 2020 (t2). In both instances, an identical set of 37 items, shown in , was sorted under the same prompt, namely, ‘According to you, what characterizes successful higher education learning environments for students in the future?’. The applied Q sample was constructed in line with the traditional Q methodological procedure (see, e.g. Lundberg et al., Citation2020; Watts & Stenner, Citation2012), which included the development of a concourse by reviewing dominant discourses surrounding LEs (Abualrub et al., Citation2013), the structuring and culling of items, and multiple rounds of pilot studies to validate the statements’ content and form. In January 2020, data were collected face-to-face, with at least one researcher present and with physical cards to be sorted, and in November 2020, this process was moved online due to social distancing regulations. In both cases, participants were first instructed to pre-sort the items into three broad categories and then place them, physically in t1 and via drag-and-drop in t2, on a distribution grid that represented a continuum from most characteristic (+5) to least characteristic (−5) for successful LEs in the future. illustrates the empty grid used in t2.

Table 1. Participants’ correlation and considerable changes between t1 and t2.

Table 2. Q set consisting of 37 items ordered from most to the least considerable changes between t1 and t2.

Respondents’ individual original and repeated Q sorts were analyzed in two ways. First, we used direct ordinal correlation, where possible values range from −100 (complete change) to + 100 (complete stability). Second, we qualitatively investigated considerable upward and downward changes on individual Q statement scores from t1 to t2 (Davis & Hodge, Citation2012). The results of this analysis are understood as descriptive indices of stability and change before and after the immediate shift to digital teaching due to the pandemic (intra-individual stability). They were also used to structure the deliberative dialogues at the third measurement point (t3), which took place in February 2021.Footnote1

The intention behind t3 was twofold. On the one hand, these deliberative dialogues served to validate the interpretation of individual sorting results, and thereby they deepened our understanding of individual academics’ normative values about LEs. Additionally, dialogues in t3 provided participants the opportunity to reflect upon their earlier sorting. Respondents for t3 were sampled according to their intra-individual stability between the first two data collection activities. Respondents 1, 3, 4 and 5 were selected due to their low correlation and respondents 9, 10, 11, 14, 15 were of interest due to their above average correlation between t1 and t2. Participants 2, 12 and 13 were not available for t3.

Deliberative dialogues between ADs and university teachers were split up between the authors of this article and organized over Zoom, which was cost effective and allowed data collection to take place at the most convenient time for participants. A pilot dialogue suggested two modifications to make the dialogue less intimidating. First, it was necessary to remind all respondents how the Q sorting activity worked. This explanation was supported by presenting the distribution grid via screen share and indicating how individual items were ranked differently by using the annotate function in Zoom. Second, we normalized participants’ lack of clear recollection of their thinking processes more than a year (t1) or 4 months (t2) earlier. We reminded participants that the sorting results and the changes pointed out to them were merely used as prompts for their honest and critical reflection about successful LEs and how the global pandemic and its local consequences impacted their perspective. The discussions were recorded and researchers took written notes. Data were first thematically and independently analyzed by both researchers using an interpretative approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In a second step, preliminary findings were discussed by the authors to delimit bias and detect incorrect interpretations (Miles et al., Citation2014).

Results and discussion

Findings with regard to how university teachers’ normative values about successful LEs have changed during the first year of the global pandemic are structured as follows. We begin by presenting quantitative results of respondents’ intra-individual stability and then discuss findings in line with Sutherland’s (Citation2018) holistic approach to AD. Considerations with regard to Q sorting as a preparatory activity for deliberative AD are presented last.

Intra-Individual stability and considerable item shifts between t1 and t2

The mean correlation between individual sorts in t1 and t2 for the whole sample was 55.533 and ranged from 23 (participant #1) to 78 (participant #15). This association indicates some degree of stability for some participants and also some degree of transformation for others. On the basis of recommendations in Akhtar-Danesh and Wingreen (Citation2020), we set four steps as a threshold for what we called ‘considerable changes’. In a first descriptive step, it was irrelevant if the item was moved from, for example, −5 to −1 or from −2 to +2. For the subsequent thematic analysis, items which were ranked at more extreme positions (closer to -/+5) in either of the Q sorting data collection activities were seen as more meaningful. As shown in , all participants ranked at least one item considerably differently in t2 compared to t1 and, on average, they did so with 5.6 items. For example, Participant 1 considerably changed his view of what successful LEs might look like in 11 out of 37 items in the study. No significant differences in relation to discipline and/or higher education teaching experience could be found, which could be explained by the common experience of all participants in dealing with uncertain conditions in the first year of the pandemic.

By considering only value changes of at least four steps, items 25 and 37 moved most frequently. Interestingly, item 37, which stated that videos of lectures to be watched as homework before class should be created (flipped classroom), exclusively moved up in the ranking of participants. In other words, the idea of the flipped classroom was more positively perceived after seven months of digital and distanced teaching. In four out of five cases, item 25, stating that the physical learning environment allows flexible teaching and learning, moved considerably downwards. This movement indicates university teachers’ lowered appreciation of having different options in physical LEs and might be explained by the strict regulation of not being allowed to physically meet in the months prior to t2. This finding also suggests that respondents might hold more lectures when being allowed to meet again on campus in post-pandemic higher education.

Despite the changed conditions, two items in this study did not undergo any considerable change (see bottom of ). Item 30, which addresses the use of lectures to achieve equal opportunities, was most often placed in a neutral position around ±0 in both t1 and t2. Item 28, which proposes that every student’s individual needs are acknowledged and met, provoked different, but equally steadfast, reactions across the participants.

Findings from deliberative dialogues in t3

Based on our interpretive approach, findings are presented in line with their relevance to a) the whole person, b) the whole of the academic role and, c) the whole institution. Because deliberative dialogues were held in Swedish, the participant quotes are to be understood as fluid descriptions of meanings rather than word-by-word translations (Van Nes et al., Citation2010).

The whole person

The uncertain and unprecedented conditions due to the global pandemic certainly influenced all participating university teachers on a personal and emotional level. The following vivid description by participant 10, to metaphorically survive during the first eight months of the pandemic, points towards a challenging situation in her perceived role as a whole person (Sutherland, Citation2018):

When Covid hit, I was very isolated. Because we, teachers and students, never met anybody, we were all focusing on ourselves. I was acting in a mental survival mode, just trying to get by. To be honest, I felt it was difficult to think about the future in November 2020.

Nevertheless, the concept of emergency remote teaching (Hodges et al., Citation2020) did not impact everyone’s normative value of what is characteristic for successful future LEs. Participant 9’s firm fundamental values as a university teacher account for her largely unchanged conception, while for participant 15, his pre-pandemic experience with digital teaching may be responsible for his relatively high intra-individual correlation between t1 and t2. Another reflection in connection to the stability and relatively unchanged Q-sorting results from t1 to t2 might be explained with a more traditional understanding of academic development and LEs. Some participants simply did no or little teaching in between the two data collection activities and consequently had no new experiences that might have impacted their normative values about what successful LEs should look like in the future.

The whole of the academic role

Several participants reported a shift in perspective during the first months of the pandemic, from limited student-student collaborations to more intensive teacher-student interactions. Participant 3, for instance, chose not to supervise students in groups and felt uncomfortable with too many breakout room discussions. As a consequence, his conception of successful LEs in the future shifted towards a closer individual relationship between teacher and student. This theme was also related by participant 4, who described how he more often sought a personal dialogue with individual students, and participant 5, who realized that students needed more individual support during these challenging times. According to participant 14, purely digital meetings led to fewer informal discussions with and among students because participants do not enter or exit virtual rooms much before or after scheduled times. Instead, the focus of attention was the content of the courses and students’ academic success. With regard to generally successful LEs in the future, participant 9 pointed toward a crucial area of potential development. She described how student collaboration during digitalized teaching and learning evolved:

Social contacts and cooperation are important but next to impossible in today’s academy. As for the students, individualization and stress lead to group work with work division, and not real collaboration. You divide and solve the task.

Less student collaboration and an increased focus on the subject matter require students to be more self-critical, confident, and creative in their learning. In turn, ADs are expected to more intensively facilitate university teachers’ competence development when teaching and administering courses as part of the whole of their academic role.

Facilitated by the repeated Q sorting activity, participants shared their more positive perspectives regarding items connected to digitalization. Some explained this shift with the fact that they were forced to try things with which they had previously had negative experiences. As demonstrated by participant 3, the flipped classroom represents a shift in normative values regarding digitalization:

Many years ago, I was part of a course where we used a flipped classroom and this did not go well. But it was not because of the pedagogical idea behind it, but rather due to our inadequate implementation. Only a few students actually came prepared to our face-to-face meetings. During the pandemic this seemed to work much better.

This experience is also supported by participant 14, who exemplified how university teachers have realized that sharing a previously recorded lecture and discussing this with students works well:

I have simply not used the flipped classroom before but now that I was ‘forced’ to use it, I can see the benefits, for example, from a resource perspective.

The whole institution

Although mandatory digital transformation has led to the revival of certain approaches (e.g. flipped classroom), a fully digital LE restricted university teachers’ options concerning the diversification of their teaching. In addition to addressing the changes forced upon teachers, the quote by participant 1 can be seen as representative of other university teachers as well because he reported a considerably intensified reflection about pedagogy and an increased number of pedagogical discussions with colleagues:

The pandemic has shown how teaching at university is not about telling students something from a book that they can read themselves. Instead, we [university teachers] had so many reflective discussions about how we teach, how we make students question what we say and, in general, foster their critical thinking really.

While figuring out how to get their content across in the beginning of the pandemic, university teachers’ focus shifted towards how they could do it in the pedagogically most suitable way. With regard to issues of digitalization, participant 14 reflected that the major transformation in early 2020 should be seen as an opportunity for future LEs because technological solutions have now been finetuned and their efficacy should be at the center of attention in the years to come. Because some changes regarding increased digitalization are expected to stay and LEs might be increasingly hybrid, more discussions within the whole institution will be necessary to determine which aspects, such as teaching mode or materials, need to be physical, and which ones can be digital. The creation of more task-oriented, time-effective, and student-focused teaching and learning will require ADs to broker between disciplines and provide university teachers with research-based grounds and suitable opportunities for development.

A further example relevant for the whole institution concerns participants’ views of nearly paper-free higher education learning and teaching (item 21). Pre-pandemic, this was not necessarily regarded as particularly characteristic of success. Even though we could record a more positive and confident use of digital media, participants were still skeptical about not using paper at all for reasons of stimulating learners with a variety of material sources, illustrated by the following quote from participant 11:

I believe that analog elements constitute a contrast and a variation. For example, I am thinking about the benefits of receiving a paper letter instead of electronic links.

A final noteworthy example with regard to the whole institution is the notion of a safe learning environment. Item 29 was interpreted completely differently in t1 and t2 and created interesting forward-looking dialogues in t3. Generally, health issues (e.g. the spread of an infection), during the pandemic created more discussions about maintaining safety. However, while participants clearly had campus safety in mind in January 2020, they related their ranking in November to private safety at home and reflected on how to minimize the risk of verbal assaults against particularly vulnerable individuals during digital meetings and maximize potential support concerning mental health. Participant 1 opened up during the deliberative dialogue with regard to his self-reflective view as a person and an academic within the whole institution:

I feel how this is not the way I want to work. I feel quite terrible sitting at home and teaching digitally. I miss the interactions and discussions with the students. However, because of the experiences during the pandemic, I now understand my role in academia better.

Q sorting for deliberative academic development

The present research design provides valuable insights into university teachers’ lived experiences during the pandemic and their subjective normative values regarding future LEs. The study also promotes the potential of Q sorting to prepare and scaffold deliberative academic development. Even though the digital version of the sorting was more challenging to administer, activities at t1 and t2 both provided university teachers with a tool to carefully reflect upon alternatives and visualize their normative values regarding successful LEs. A particular advantage of Q sorting as a means for holistic academic development is the ‘holistic nature of the procedure’ (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012, p. 148). By ranking every item in relation to all other items, Q sorting provides a more holistic representation of participants’ perspectives than more common atomistic approaches such as Likert scale type questionnaires. The opportunity to structure our deliberative dialogues with university teachers according to their holistic Q sorting results led to deep and focused discussions.

Our study design included deliberative dialogues after the final Q sorting activity. Those dialogues proved to be successfully scaffolded through our quantitative analysis of respondents’ intra-individual stability between t1 and t2 , which helped participants to remember their reflections and normative values before and during this challenging period. However, the future use of Q sorting in academic development might include deliberative dialogues during the actual administration of the sorting activity. Such a dialogic component during a Q sorting activity might further enhance university teachers’ critical engagement with issues relevant for academic development. Moreover, a structured collaborative activity with several Q sorters could lead to meaningful discussions among university teachers and create crucial collaborative and collegial relationships between ADs and university teachers (Fremstad et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

It is important to note that the findings presented here should not be understood as universal tendencies or statistically representative of the university teacher population. Moreover, as reported by participant 9, changes in sorting might merely be coincidental and unintentional and not a consequence of the forced digitalization. Further, changes between the two Q sorting activities do not automatically mean that respondents changed their minds but could have been a pragmatic consequence of other items being prioritized, thus leaving limited sorting options for the remaining items. Nevertheless, by focusing in particular on considerable changes among the selected sample of respondents, the present study contributes to a better understanding of how the immediate shift to remote and digital teaching has affected university teachers’ perspective about successful LEs. The application of Q sorting to prepare participants for deliberative dialogues was meant to be a small-scale investigation. To further validate the exploratory findings in the present study and potentially reveal disciplinary nuances, a large-scale investigation including respondents from different contexts should be considered. Such a study might also yield the extent to which individuals’ normative values have become part of institutional cultures and traditions (Schwieler & Ekecrantz, Citation2011).

Implications and recommendations for academic developers

Results in the present study inform recommendations that ADs prepare themselves to respond by offering appropriate support. We describe several implications and recommendations for ADs in their work of leading HE (Solbrekke & Sugrue, Citation2020) and supporting university teachers in future LEs. The diverse range of experiences reported here illustrate the importance of knowing how university teachers, individually and collectively within their microcultures, understand their teaching and learning contexts and what will characterize future higher education. The reflective and deliberative dialogues in t3 have also clearly shown the necessity to view AD more holistically and understand university teachers as whole persons contextually situated within a large institution (Sutherland, Citation2018).

In our exploratory study, the pedagogical idea behind the flipped classroom was appreciated more after the digital transformation and might suggest both a greater valuation of digital models and a general desire by university teachers to be as effective as possible in their teaching. The shift towards more positive normative values regarding the flipped classroom goes hand-in-hand with an increased focus on student engagement, be it while preparing face-to-face learning phases or during remote digital activities.

Furthermore, the participants in our study disassociated from the statement that the physical learning environment allows flexible teaching and learning. This finding is suggestive that when university teachers meet students in future face-to-face teaching environments, only one teaching mode will be used. University teachers want to reestablish the social interaction between teachers and students and between students. With regard to potentially increasingly hybrid teaching and learning environments, more deliberative dialogues among university teachers facilitated by ADs will be necessary to establish what content is most suited for which mode.

Conclusion

Q sorting has proven to be a promising tool in ADs’ methodological repertoire and thereby contributes to our own development within a holistic view of AD (Sutherland, Citation2018). By ranking a set of items regarding a central issue, facilitated dialogues with university teachers contributed relevant first-person accounts of lived experiences during the first year of the pandemic. Participating university teachers shifted their normative values regarding successful LEs towards a more individual perspective, where students will have to show more responsibility for their learning process and practice their critical thinking skills. Simultaneously, many university teachers reported being prepared for the next phase in their role as an academic, potentially including more hybridity with regard to teaching and learning environments. Participants in the study increased their awareness of the importance of pedagogical discussions and emerged as more reflective practitioners after a period characterized by acting in survival mode during emergency remote teaching.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adrian Lundberg

Adrian Lundberg is assistant professor of education at Malmö University in Sweden. His research focuses on educational issues at the crossroads of multilingualism, equity, and policy.

Martin Stigmar

Martin Stigmar holds the position of professor of teaching and learning in higher education at Malmö University in Sweden. His research primarily focuses on teaching and learning in higher education and flexible online learning.

Notes

1. Results from paired Q methodological analysis, including inverted factor analysis and descriptions of shared viewpoints, are reported elsewhere (Lundberg & Stigmar, Citationin press).

References

- Abualrub, I., Karseth, B., & Stensaker, B. (2013). The various understandings of learning environment in higher education and its quality implications. Quality in Higher Education, 19(1), 90–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2013.772464

- Akhtar Danesh, N., & Wingreen, S. C. (2020). How to analyze change in perception from paired Q-sorts. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610926.2020.1845734

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Davis, B. B., & Hodge, I. D. (2012). Shifting environmental perspectives in agriculture: Repeated Q analysis and the stability of preference structures. Ecological Economics, 83, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.013

- Entwistle, N., Skinner, D., Entwistle, D., & Orr, S. (2000). Conceptions and beliefs about ‘good teaching’: An integration of contrasting research. Higher Education Research & Development, 19(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360050020444

- Fremstad, E., Bergh, A., Solbrekke, T. D., & Fossland, T. (2020). Deliberative academic development: The potential and challenge of agency. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1631169

- Godor, B. P. (2016). Moving beyond the deep and surface dichotomy: Using Q methodology to explore students’ approaches to studying. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1136275

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Retrieved May 20, 2020, from from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Huijser, H., Sim, K. N., & Felten, P. (2020). Change, agency, and boundary spanning in dynamic context. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(2), 91–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1753919

- Kandlbinder, P. (2007). The challenge of deliberation for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 12(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440701217345

- Lundberg, A., de Leeuw, R. R., & Aliani, R. (2020). Using Q methodology: Sorting out subjectivity in educational research. Educational Research Review, 31, 100361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100361

- Lundberg, A., & Stigmar, M. (in press). University teachers' shifting views of successful learning environments in the future. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (Third ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Niemeyer, S., Ayirtman, S., & HartzKarp, J. (2013). Understanding deliberative citizens: The application of Q methodology to deliberation on policy issues. Operant Subjectivity, 36(2), 114–134. https://doi.org/10.15133/j.os.2012.007

- Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education. Routledge.

- Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

- Schwieler, E., & Ekecrantz, S. (2011). Normative values in teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning in higher education: A belief system approach. International Journal for Academic Development, 16(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.546230

- Sim, K. N., Timmermans, J. A., & Zou, T. X. P. (2020). Diversity matters: Academic development in times of uncertainty and beyond*. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(3), 201–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1797950

- T. D. Solbrekke, & C. Sugrue (Eds.). (2020). Leading higher education as and for public good. Rekindling education as praxis. Routledge.

- Stigmar, M. (2008). Faculty development through an educational action programme. Higher Education Research & Development, 27(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701805242

- Sugrue, C., Englund, T., Solbrekke, T. D., & Fossland, T. (2018). Trends in the practices of academic developers: Trajectories of higher education? Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2336–2353. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1326026

- Sutherland, K. A., & Grant, B. (2016). Researching academic development. In D. Baume & C. Popovic (Eds.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 187–206). Routledge.

- Sutherland, K. A. (2018). Holistic academic development: Is it time to think more broadly about the academic development project? International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571

- Van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., & Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q methodological research: Theory, method and interpretation. SAGE Publications.

- Woods, C. (2012). Exploring emotion in the higher education workplace: Capturing contrasting perspectives using Q methodology. Higher Education, 64(6), 891–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9535-2