ABSTRACT

This article presents a theoretical relational perspective of education, Pedagogical Relational Teachership (PeRT), which supports the development of new knowledge about teachers’ relational proficiencies to create opportunities for students to participate in their education and to emerge as unique individuals and speak with their own voices. Within the field of inclusive education, it is a relational approach where teaching is to be understood relationally. The fundamental bases in this inclusive perspective on education are the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Salamanca Statement. The concept of relational teachership is elaborated on to emphasise the importance of teachers’ relational proficiencies in the classroom. The article also clarifies how PeRT includes a multi-dimensional model to illuminate relational processes and relationships on different levels within the educational system. PeRT is a relational approach for scholars and practitioners, which can be seen as a new beginning and an invitation to a relational pathway that explores participation, accessibility and equity.

Plurality is the condition of human action.

Hannah Arendt (Citation1998)

Introduction

The school is a social meeting place where different types of relationships between teachers and students emerge during daily interactions. Over the past decade, international research (Hattie Citation2009; Mitchell Citation2014) has shown the importance of trustful relationships between teachers and students. Even though teachers, students and parents all emphasise that well-functioning, sustainable teacher-student relationships lay the foundation for student growth (Aspelin Citation2017), there are few empirical studies that deepen the relational part of the teaching profession. Since the turn of the millennium, there has been an increased focus on the breadth of teacher competencies that contribute to student learning.

A systematic review by Nordenbo et al. (Citation2008) presented three main teacher competencies that intertwine in teaching situations: a relational competency that outlines how a teacher enters into social relations with respect to the individual student, a didactic teaching competency and a leader competency in the classroom. All in all, these three competencies are constantly intertwined in teaching. Among these competencies, the relational competency is a fundamental proficiency, which can be described as relational proficiencies. In current school environments, teachers’ relational proficiencies are increasingly seen as reasonable and necessary prerequisites for didactic competency (Sandvik Citation2009). However, the relational field is small and largely unexplored and needs a more precise theoretical starting point (Aspelin Citation2017). In the field of inclusive education, this article presents a theoretical, multi-relational perspective, Pedagogical Relational Teachership (PeRT) Footnote1, which supports new knowledge about teachers’ relational proficiencies and the development of trustful teacher-student relationships and sustainable conditionsFootnote2 for student participation.

The purpose of education in a globalised world

Just as research reveals how teachers’ relational proficiencies are crucial for successful education, it also clarifies that the relational part of teaching can be learned and developed through interaction with students (Sandvik Citation2009; Frelin Citation2010; Ljungblad Citation2016). In the discussion about relational qualities in education, it is also important to reconnect with the question of purpose in education within present and future schools (Biesta Citation2009).

We live in a global, digital world that cultivates diverse communities. Information is readily available through the Internet, and it cannot be taken for granted that today’s youth and young adults will necessarily take part in education to learn what previous generations have created, especially when such a rich source of knowledge is available in digital form. In addition, during the past two decades, a learning discourse has emerged that has been scrutinising the student’s learning process (Biesta Citation2006, Citation2017). Learning is basically an individual concept that focuses on what people as individuals do and ‘stands in stark contrast to the concept of “education” which always implies a relationship’ (Biesta Citation2009, 39). Biesta points out how this educational discourse, which he refers to as ‘learnification’, tends to misguide students by losing some democratic freedom. We are now at a point where new thoughts about democratic processes need to be addressed to handle the challenges of today’s complex world (Rosanvallon Citation2009).

Children’s rights (United Nations Citation1989) in education, with the reproduction of obvious inequalities within and across schools (Biesta Citation2009), are reflected in the discussion about inclusion (Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006; Graham and Slee Citation2008; Allan Citation2009). In discussing children’s rights in modern education, inclusion can be seen as a core value of democracy (Biesta Citation2001, Citation2007). Consequently, we need to ask the question: Where does democracy start? Democracy is about participation, and since students and teachers participate in relationships when they meet on a daily basis, interpersonal relationships constitute the cornerstone of teaching; however, participation in pedagogical relationships is complicated. One of the most prominent challenges for teachers is to enable student participation in relational teaching situations with their rapidly changing natures. Participation also includes taking the standpoint of others seriously (von Wright Citation2006). In accordance with inclusion, democracy and student participation, Biesta (Citation2009) addressed the problem of effective socialisation and how young people enter an existing order where some people decide the terms for inclusion. These people not only set the conditions for inclusive education, but they are also the people who decide what others to include.

In light of the above, Biesta (Citation2007) clarified the need for another kind of inclusion, namely, the incalculable, which is an attempt to go beyond inclusive and exclusive processes.Footnote3 In Biesta’s alternative way of looking at inclusion, democracy and participation, a person is not excluded from an existing order. From a child’s perspective, the young generation can thereby say, ‘Don’t count me in, I am already there’. Additionally, the educational system is responsible for each child. Such a radical perspective on teaching also gives insight that complex and incalculable situations will occur, and it is important to problematise the conditions for participation in how unique children can speak with their own voices. This radical alternative perspective (cf. Armstrong, Armstrong, and Spandagou Citation2011; Hausstätter Citation2014) can be seen as a continuously ongoing process that is open to uncertainty and is capable of supporting the emergence of unique children.

Due to existing problems with inequality and exclusion within the educational system, there is a need to shift from learning to education, as well as to reinvent a new educational language for the challenges of today and tomorrow (Biesta Citation2006). With a new focus on teaching, it is also essential to enlighten schools about how to offer educational environments focusing on intellectual freedom and open dialogue, where participation in mutual discussions and explorations become interesting and important for young people (Ljungblad and Lennerstad Citation2011). Such modern, mutual Bildung processesFootnote4 (von Hentig Citation1996; Biesta Citation2002; Løvlie Citation2002) between people take different expressions, which is in contrast to the contemporary learning discourse where a person seeks knowledge on his or her own. In the formulation of PeRT as an inclusive relational perspective, I advocate for developing similar meaningful teacher-student relationships by offering interesting educational environments that children and young people cannot find elsewhere in society. Such educational environments are value-based rather than evidence-based.

In line with the discussion about education in a globalised world, Biesta (Citation2009) introduced a framework with three purposes of education: qualification, socialisation and subjectification. In reality, there is always a mix of these three dimensions and functions. The first dimension, qualification, is the society’s need to qualify children for future professions. The next dimension, socialisation, is when young people are introduced to an existing order, which to a large extent is a process about making students the same as everyone else. Hence, if the positions are already assigned, Säfström (Citation2005) claims that socialisation is a concept that can limit unique individuality. The next dimension in Biesta’s framework emphasises how education not only contributes to qualification and socialisation but also to subjectification:

Education (…) also impacts on what we might refer to as processes of individuation or, as I prefer to call it, processes of subjectification – of becoming a subject. The subjectification function might perhaps best be understood as the opposite of the socialization function. It is precisely not about the insertion of ‘newcomers’ into existing orders, but about ways of being that hint at independence from such orders; ways of being in which the individual is not simply a ‘specimen’ of a more encompassing order (Biesta Citation2009, 40).

PeRT’s Definition of inclusion

Within the field of inclusive education, different definitions can be identified, such as inclusive education related to ability differences, or gender, race, ethnicity and cultural differences, as well as processes overcoming barriers to participation and learning (Waitoller and Artiles Citation2013). PeRT resembles the last group of studies and contributes to the building of inclusive education by exploring relationships across national and cultural boundaries (Slee Citation2011). It is a relational perspective that does not focus on the physical classroom, and instead highlights another space, the in-between, where students and teachers meet face-to-face (Biesta Citation2010). In line with Biesta’s (Citation2001, Citation2007) the incalculable as an alternative approach in the field of inclusive education, PeRT embraces uniqueness, diversity and difference (Säfström Citation2005). It also includes a relational voice that illuminates existential dimensions, relational aspects and values, with the essential aim of exploring and developing new knowledge about teaching conditions that enable subjectification.

The multi-relational model can support teachers and special needs educators in developing relational teacherships and trustful and respectful teacher-student relationships. In the contemporary culture of measurement in education (Biesta Citation2017), PeRT is a relational alternative that strives to put human values at the forefront of modern education in the realisation of children’s rights.

Relational pedagogy – a third alternative

Historically speaking, educational knowledge traditions and perspectives have centred around either an individual or collectivist focus, but relational pedagogy now offers a third alternative (Bingham and Sidorkin Citation2010). Within the educational system, it is an approach where teaching is to be understood relationally. Consequently, this third pathway of seeing education shifts the spotlight from individuals, groups and their practices onto relationships.

Relational pedagogy is ontologically based on the idea that people share a social living space with other people; thus, a human being is born into relationships and lives her life within relationships and in community with other human beings (Emirbayer Citation1997; Gergen Citation2009; Aspelin Citation2014). Relationships between people compose a fundamental prerequisite for human life and children’s growth in educational environments. Accordingly, relational pedagogy is a theoretical perspective based on the concept of human beings as relational beings and teaching as relational processes. It is a relational perspective on teaching that places relationships between teachers and students at the centre of the process. This new approach in educational theory rests on pluralism and diversity and acknowledges that we all are different from one another. Its philosophical roots are derived from an intersubjectivity philosophical tradition and classical relational philosophers, such as Levinas (Citation1998), Arendt (Citation1998), Mead (Citation1934) and Buber (Citation2011). From these historical sources, the theory of intersubjectivity in today’s schools has been immersed with contemporary interpreters, like Biesta (Citation2006), Säfström (Citation2005), von Wright (Citation2006), Løvlie (Citation2007) and Aspelin (Citation2014).

In an international anthology of relational pedagogy, No Education Without Relation, Bingham and Sidorkin (Citation2010) presented a Manifesto of Relational Pedagogy that emphasised some basic assumptions: (1) relationships are primary and actions are secondary, and (2) relationships exist in and through the practices shared by people. The authors of the manifesto developed the new pedagogy based on a practical need for relational educational theory that strives for democratic relations. In the book Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community, Gergen (Citation2009) also provided a relational alternative to traditional assumptions about the rational individual as being separate from others by illuminating the significance of relationships. Gergen challenged the traditional view of the individual mind and private space of consciousness by probing into how individual reason is an outcome of relationships. This is one view of human beings that implies that all we say and do is manifested in our relational existence. More precisely, whichever ways we think, remember, feel and create, we participate in relationships. The author proposes a shift from bounded being to relational being, or to put it succinctly, a shift from I to we. Gergen’s choice to write relational being and not relational self is based on the idea that ‘In being, we are in motion, carrying with us a past as we move through the present into a becoming’ (xxvi). As a consequence of this shift in educational environments, learning and knowledge are seen as a result of relationships. More specifically, teachers and students are constantly involved in relational processes. Thus, rather than looking at independent factors and variables outside of school, ‘the concern shifts to the conditions of relational life in which the child participates’ (58). Individual rights are then understood as outcomes of relational life and the way relationships can flourish.

To conclude, the tenets of relational pedagogy are summarised as: (1) subjectivity being based on plurality and (2) human subjectivity being intersubjectively constituted. In line with this theoretical foundation, face-to-face interaction between teachers and students is the point of departure for understanding educational relationships. This gap, or the in-between, is the space where education takes place (Biesta Citation2010). However, relational pedagogy is a young scientific field when it comes to empirical classroom research and raises issues of different natures, such as students’ participation (von Wright Citation2006), ethical responsibility (Säfström Citation2005), uniqueness (Biesta Citation2006), ethics of care (Noddings Citation1999), a relational ethic of solidarity (Margonis Citation2007) and existential dimensions (Aspelin Citation2014), as well as how teachers relate to students (Ljungblad Citation2016). Accordingly, relational pedagogy is a field where researchers work together on the basis of an ontologically-shared approach that acknowledges the social and relational character of teaching and problematises the ethical and political aspects. Within this diverse source of research, PeRT is a relational perspective on teaching and education that has emerged as a new branch that can enrich and expand our understanding of relational processes and educational relationships.

Exploring teacher-student relationships

PeRT is founded on empirical classroom research exploring teacher-student relationships in today’s schools. In a micro-ethnographic study, Tact and Stance – A Relational Study About the Incalculable in Mathematics Teaching (Ljungblad Citation2016), the spotlight was directed towards how teachers relate to students when they teach. The point of departure was the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (United Nations Citation1989) and the right of children to participate in democratic educational relationships, in the sense that unique children are given the opportunity to speak with their own voices. The selection of four participating teachers was considered positive based on former students describing how these teachers meet students in a secure way that is conducive to development. Consequently, from a child’s perspective, there was something meaningful to explore in these educational environments. In the study, one hundred children from compulsory schools, upper secondary schools and schools for children with learning disabilities participated. Among the participants there was a wide range of variations of physical and intellectual functionality: different learning difficulties, different diagnoses and visual impairments, as well as students with intellectual challenges, communication difficulties, lack of spoken language, and who use wheelchairs. Inspired by Biesta’s (Citation2001, Citation2007) the incalculable as an alternative approach in the field of inclusion, the study empirically explored teaching, particularly its most complex dilemma situations. To help understand student participation, video recording was used to explore the in-between and what occurs face-to-face between teachers and students in the moment of teaching. In the microanalysis, teachers’ pedagogical adaptability was captured in a movement, a gesture, a glance and a tone of voice, and this acknowledgement was understood in terms of pedagogical tact (Løvlie Citation2007).

At a general level, the main results show how the participating teachers created and maintained trustful and respectful teacher-student relationships. More specifically, the microanalysis presents detailed depictions of how the teachers related to their students in ways that created trust and respect. The findings show a similar pattern in how the four teachers related to their students, which is described as pedagogical tact and stance. Furthermore, the findings gave insight into how the teachers’ pedagogical tactfulness created space for the students’ unique voices to emerge. The results also highlighted a listening and empathetic pedagogical stance, which created possibilities for the students to influence their own participation even in dilemma situations.

In this article, the concept of relational teachership, which originated from the pedagogical tact and stance of teachers, is introduced to emphasise the importance of relational proficiencies in education. In accordance with the empirical results (Ljungblad Citation2016) verifying that successful relational teachership already exists in some educational environments, and based on the model for how the study empirically operationalised a relational perspective on teaching, a new multi-relational theoretical perspective, PeRT, was created to inspire and support the development of teachers’ relational proficiencies in schools now and in the future.

Pedagogical relational teachership

PeRT is a theoretical perspective of teaching within the field of inclusive education. It is pedagogical in the sense that it explores opportunities and obstacles for student participation in democratic educational relationships, alongside the child’s right to reveal his or her uniqueness (Säfström Citation2005; Biesta Citation2006; Ljungblad Citation2016). Through a relational-oriented approach, the spotlight is directed towards interpersonal relationships and teachers’ relational proficiencies. Essentially, PeRT highlights the centrality of relationships at all levels in the education system.

Along with a theoretical framework (Ljungblad Citation2016) based on contemporary interpreters (Säfström Citation2005; Biesta Citation2006; von Wright Citation2006; Løvlie Citation2007; Aspelin Citation2014), the construction, mediation and development of knowledge within PeRT stems from a relational teaching perspective grounded in intersubjective traditions of philosophy. Some fundamental tenets of the interpersonal dimensions of education underline the following aspects:

The human being is a relational being.

Relationships are the foundation for human existence.

We live in a pluralistic world.

The spotlight is aimed at interpersonal interactions and the in-between.

Human subjectivity is intersubjectively constituted.

Teaching and learning are seen as relational processes.

Students’ participation is in focus.

There is an open view of children highlighting how each student can emerge.

Pedagogical meetings are important where one person meets another person face-to-face.

The view of knowledge is a relational view.

The adults have a responsibility to encounter diversity.

In conclusion, such a relational ontology and epistemology rest on pluralism and difference. Différance Footnote5 is one way of approaching education based on the lived experiences that you are different from me and I am different from you (Säfström Citation2005). PeRT views this as a starting point to strive for new possibilities about togetherness in plurality.

Furthermore, PeRT includes keywords that characterise the theory (Ljungblad Citation2016): relational teachership, relationship, the emergence of the child, the in-between (Biesta Citation2010), open communication, tact, shifts of tact, contact, pedagogical tactfulness, stance, curiosity, pathfinder, stand in relation, We, relational meaning-making, Who-What (von Wright Citation2006), pedagogical meeting, space of freedom and change of order. The concept of relational teachership can be seen as an umbrella term for this theoretical approach. Thus, relational teachership is a vital concept for relational proficiencies regardless of whether teaching children, teenagers or adults.

PeRT – a three-dimensional model

PeRT is a multi-relational theoretical perspective anchored by empirical research in today’s schools (Ljungblad Citation2016). It has a three-dimensional model for exploring educational relationships in a wider web of relations from social to societal levels. Such a pragmatic view can be used in empirical classroom studies to shed new light on interpersonal relationships, existential dimensions and relational values within the educational system. The model also visualises how pedagogy and didactics are constantly intertwined in teaching, where both student participation and accessibility to subject content are essential core values. In the field of inclusive education, this relational perspective distinguishes an important transition from a traditional focus on the physical classroom to the in-between, the gap between teacher and student where teaching takes place (Biesta Citation2010). Biesta emphasises that this space cannot be controlled by either partner if meaning-making is to occur. This place is not where I am, or where you are, but right between us. Since meanings are shared and located in-between, we have to embrace this gap, and PeRT is a theoretical inclusive perspective that highlights this essential space.

First dimension of PeRT

PeRT is a theoretical perspective based on the CRC (United Nations Citation1989) and the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO Citation1994). Each child has a fundamental right to be educated and to participate in democratic educational relationships, in the sense that he or she is emerging as a unique person. It is an relational approach to education that emphasises a child’s right to take part in teaching that enables their potential. Accentuating children’s rights in education highlights an essential shift from child policy to child rights policy. Some countries, such as Norway, have already adopted the CRC as law, and the child’s legal status has been strengthened. Other countries, like Sweden, will shortly do the same. Consequently, there is a need for new research, as well as theories and models, that can contribute to the implementation and the realisation of the CRC (UNICEF Citation2007).

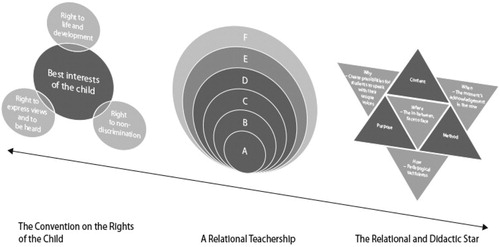

The first dimension of PeRT is constituted on the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO Citation1994) and the CRC (United Nations Citation1989), with a focus on four child’s rights articles: Article 2 (right to non-discrimination), Article 3 (adherence to the best interests of the child), Article 6 (right to life and development) and Article 12 (right to express views and to be heard). In accordance with student participation, these articles can be seen as four guiding principles that represent the underlying requirements for any and all rights to be realised. Moreover, the best interests of the child can be regarded as an overall central principle. .

When advocating for children’s rights, it is paramount to emphasise that rights are guaranteed, and they should not be confused with care and goodness. The Salamanca Statement (UNESCO Citation1994) emphasises that people are born with different variations of physical and intellectual functionality, and the teachers are assigned the task of responding to children’s different ways of being, existing and becoming. Accordingly, PeRT is a relational perspective that values and sustains children’s rights within the educational system. This implies that empirical studies conducted within PeRT explore the educational system’s prerequisites and opportunities for children’s participation. In addition to the Salamanca Statement and the CRC’s view of children, ethical considerations need to be considered at every phase of empirical research with children, keeping in mind the best interests of the child and the right of the child to express her or his view and be heard. The child’s perspective usually relates directly to the section of the CRC dealing with the best interests of the child and is closely linked to ethical issues, adult responsibility, and such values need constantly to be problematised in research, as well as in education.

Second dimension of PeRT

Relational theory has implications for all levels in the educational system since teachers and students are in relation to each other in their greater environment outside of school. One of the primary aims of education is ‘to enhance the potentials for participating in relational processes – from the local to the global’ (Gergen Citation2009, 243). Accordingly, our actions are embedded in relationships, and PeRT’s multi-dimensional model makes these relational conditions visible.

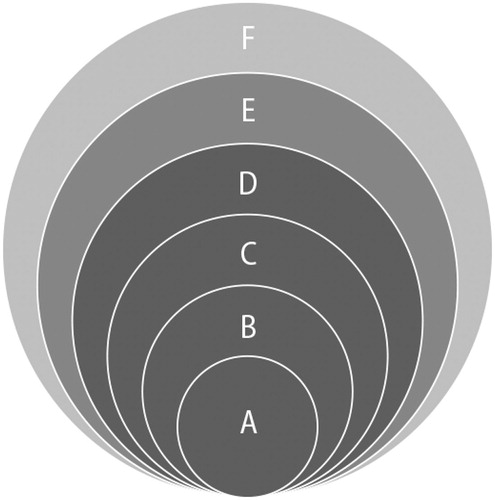

The second dimension of PeRT’s model reveals different aspects of relational teachership and highlights the relationships between teachers and students. The model is inspired by Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ecological model that focuses on quality for children and young people growing in different environments. Bronfenbrenner describes his model as bioecological, which takes the child’s biological and psychological conditions into account. This differs from PeRT’s relational model, which highlights interpersonal relational processes within the educational system. .

Figure 2. The model shows how different aspects of relational teachership are closely intertwined, from a micro-level to a macro-level.

The ontological point of departure (A) emphasises the relationship as primary. The micro-level (B) is able to zoom in on the interpersonal interaction when the teacher and students meet face-to-face. At the third level (C), the teacher-student relationship is in focus, where a relational meaning-making appears when the teacher searches for Who the student is (von Wright Citation2006). The next level (D) reveals relational aspects of what it means to teach and be a teacher. In addition, the school meso-level (E) illustrates how people in the school and the municipality cooperate and manage the organisation of teaching, with different collaborative forms, financial resources, teacher proficiencies and the physical environment. Finally, the model displays an overall societal macro-level (F) with political intentions, governance, laws, power relations, research, knowledge and global influences. On the macro-level, there are also different macro systems that together form the societal level. Children belong to different macro systems depending on social belonging and ethnic and religious backgrounds, as well as families living in various areas and municipalities. Relationships within the family, and the child’s relationships in their spare time, are also part of the child’s experiences while participating in education.

The model has the potential to capture different levels in the dynamic educational system that changes over time. Since relationships are embedded in time and space (Emirbayer Citation1997), the challenge is to develop theories and methods that can explore cultures across different levels and avoid ad hoc interpretations. Hence, teaching does not occur ‘in a neutral, ahistorical context’ and the history of excluding marginalised groups from education complicates teaching relations (Hinsdale Citation2016, 9). Today in research, there is also an increasing interest in theories and models that attempt to bridge the gap between micro and macro levels and connect multiple levels of analysis (Klein and Kozlowski Citation2000).

Although the micro-, meso- and macro-levels are closely intertwined, they sometimes need to be illuminated separately.Footnote6 Within the micro-levels in the model, including A, B, C and D, there is a ‘free space’ for the teacher to decide how to meet the students when they teach (Ljungblad Citation2016). This differs from the meso-level E, and the macro-level F, where global trends and other actors, such as school authorities and politicians, regulate the work. Essentially, when teachers change their way of relating to their students in ways that create trust and respect, a strong driving force emerges in the educational environment. Hence, teachers have a choice to walk along such a relational pathway. At the same time, striving at the national level to support schools in developing relational teachership could also make a huge impact. Accordingly, the movement in the educational system is bi-directional, and the motion on the two overall levels needs to be weighed into the analysis of what opportunities are given to the teachers for meeting their students.

Third dimension of PeRT

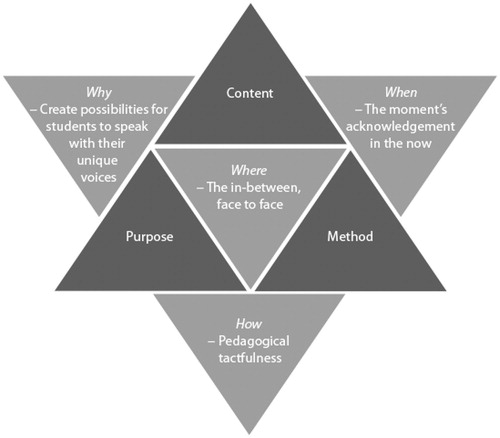

In the third dimension of PeRT’s model, school subjects and didactic aspects are distinguished in teaching. The didactic triangle (Zittoun et al. Citation2007), which originated from Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) mediational tradition, emphasises the purpose, content and methods of teaching, together with the classic didactic questions why, what and how. In the teacher’s planning, why clarifies the purpose of studying a particular subject. The didactic what addresses the content of teaching. Finally, how problematises processes and methods in teaching. But the didactic triangle does not illuminate the people who participate in the teaching community. As an alternative, PeRT’s model places the participants and teacher-student relationships at the heart of teaching (Aspelin Citation2017).

Later research (Hattie Citation2009) shows that a trustful teacher-student relationship has a greater influence on the student’s level of learning than the teacher’s subject knowledge. This gives insight into how important both the relational and didactic parts are in teaching. .

Hence, in order to create an extended relational understanding of situated teaching, the didactic triangle is expanded and includes four relational questions – why, where, when, how – and form a star. These relational questions (Ljungblad Citation2016) highlight different aspects of the student’s subjectification (Biesta Citation2009).

Why - to create possibilities for students to speak with their unique voices.

Where - the in-between; the space between teacher and student; face-to-face.

When - the moment of acknowledgement in the now.

How - pedagogical tactfulness.

In the search for new teaching opportunities that create space for the emergence of the student’s self, a focus on traditional didactic questions is not enough. The Relational and Didactic Star clearly shows how pedagogy and didactics converge when the teacher and students draw attention to a topic as well as to each other. The teaching situation is a complex interaction: the teacher starts from a lesson plan to mediate the subject content, but at the same time is involved in a wide range of interpersonal interactions. When research (Ljungblad Citation2016) explored interpersonal interactions in teaching scenarios, a dual meaning-making became visible. On one hand, it was a relational meaning-making that included a clarification about Who the other person was and how he or she appeared in the event (von Wright Citation2006). On the other hand, there was also a meaning-making about how the participants understood the subject content that was discussed. This brought to light not only participation per se, but also participation where a double meaning-making came into play; in educational interaction, there is constant movement between human beings while a person is simultaneously experiencing the world and searching for new knowledge. These two facets of meaning-making are important when teachers develop relational and didactic adaptions to create accessibility to the content. Today, didactic adaptions are often discussed among teachers and tried out in different teaching situations to support students in special educational needs. However, there is not the same focus on relational adaptions, which implies that the teacher reflects upon how the interpersonal environment around a student can be adapted. Based on relational concerns, the teacher’s relational view is directed towards the participants’ interactions and how to create a respectful and trustful environment. To summarise, the Relational and Didactic Star has the potential to enlighten both relational values and didactic aspects, as well as different contexts, when teachers and students work and cooperate in the classroom.

A multi-relational model that can bridge the gap

PeRT’s multi-relational model can illuminate all levels of the educational system while creating sustainable conditions for student participation. Today, there is increasing interest in research attempting to bridge the gap between micro- and macro-levels to develop new knowledge about relationships and phenomena that cross several levels (Klein and Kozlowski Citation2000). PeRT’s multi-dimensional model is an analytical tool that can be used to bridge this gap when it comes to interpersonal relationships within the educational system. When exploring and problematising different relational aspects, one can zoom in on one of the analytical levels, then zoom out and analyse them together. The three dimensions presented above constitute a whole. How PeRT’s dimensions are linked together to establish a composite model is illustrated in the model below. .

PeRT’s first dimension is constituted on children’s rights (United Nations Citation1989; UNESCO Citation1994). At an international level, rights are usually formulated from a negative rights claim; a negative right does not require action from one person, but rather means that another person refrains from acting. In contrast, PeRT emphasises a positive rights claim for teachers to actively support students and seek out new ways for student participation. This shift in children’s rights to an active positive claim takes children’s rights seriously. The second dimension in the model highlights relational teachership with its existential aspects and relational values and creates an extended relational understanding of situated teaching. Relational teachership also comes with an educational responsibility for teachers to acknowledge diversity and uniqueness. The third dimension gives prominence to adapting sustainable teaching conditions so that the children’s own voices can emerge. Hence, the responsibility to encounter diversity is an educational question to which the pedagogy and didactics must respond. In addition, the Relational and Didactic Star is a tool that can support the exploration of both a relational how and a didactic how, given that there is no clear distinction between the closely-intertwined pedagogical and didactic relationships.

To conclude PeRT’s framework of inclusive education. The incalculable (Biesta Citation2007) embraces a ‘beautiful risk’ since education is an encounter between human beings (Biesta Citation2014, 1). This brings into light, (1) the essence of existential aspects about the quality of relationships and (2) an endeavour about finding new possibilities for each and every student’s active and meaningful participation. In line with such an approach Biesta emphasises the difference between ‘what it means to educate and, more specifically, what it means to educate with an orientation toward and an interest in the event of subjectivity’ (ibid. 23). Furthermore, by highlighting subjectification (Biesta Citation2009) as an essential dimension in inclusive education, it also generates a need for new theoretical perspectives. Consequently, PeRT was created to support how the educational system can contribute to the creation of human subjectivity. PeRT’s multi-dimensional model illustrates various facets of relational teachership at different levels within the educational system. The multi-relational model can be used in teacher education at universities, as well as in pedagogic, didactic and special education research. PeRT can also support teachers who strive for sustainable development and inclusive promotion, with a focus on student participation and the way how interpersonal relationships can flourish.

Discussion

PeRT is a new beginning and an invitation to a relational pathway that enriches our potential. Modern global education addresses issues of diversity. Given human diversity, all children have an equal right to participate in high-quality education where they can speak with their unique voices and listen to the voices of others. In contemporary cultures that put merit in educational measurement, subjectification has a tendency to disappear from the educational scene (Biesta Citation2017). Therefore, modern inclusive education needs to clarify the significance of creating a space for students’ intellectual freedom. Subjectification is a dimension about how young people can emerge and how their beginnings are taken up by teachers (Biesta Citation2014), which is an educational responsibility and pathway that teachers can only choose themselves. An essential part of subjectification can be traced back to how teachers relate to their students in complex dilemma situations (Ljungblad Citation2016). During the last decades, there has been increasing interest in how teachers can develop relational proficiencies. One of the most prominent challenges that teachers face in today’s schools is how to create and maintain trustful and respectful interpersonal relationships with students. Such a sustainable relationship allows a child to become somebody, because without a sense of self, a child is voiceless. In that moment, the child brings something radically new into the world it is essential that the teacher acknowledges the student’s uniqueness. Such an encounter between human beings cannot be planned or foreseen and highlights the importance of relational teachership.

Teaching includes social and relational proficiencies that nurture children’s being and becoming. This article introduces a new concept, relational teachership, which originates from pedagogical tactfulness and stance, as fundamental relational aspects of teaching (Ljungblad Citation2016). The complexities of relational teachership give insight into how teaching is an incalculable process that sometimes have to be improvised in the moment. At the same time, there is hope since we can learn from our experiences in practice and develop our relational teachership. In light of the above, there is a need for researchers in the field of inclusive education to explore relational values in classroom studies, to survey teacher-student relationships all over the world, and to investigate how relationships emerge in different cultures in classrooms in Bogota, Kyoto, Reykjavik, Addis Abeba and Perth. What differences and similarities are captured? What new opportunities can change bring? Along the same lines, it is important to explore how trustful and respectful relationships can create new possibilities for socially vulnerable students and for children in special needs; for these groups, relational values like trust, faith and respect can make a difference to an individual student’s life opportunities (Ljungblad Citation2016; Citation2020 in progress).

PeRT is a theoretical relational perspective created to support a new generation in the field of inclusive education, with a shift to an active positive claim on children’s rights (United Nations Citation1989; UNICEF Citation2007) and the realisation of the values in the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO Citation1994). It is a holistic approach for the present and the future and for the local and the global. Based on the assumption of equality (Biesta Citation2014), PeRT sustains children’s rights within the educational system. Furthermore, it is an ecological approach that focuses on teaching environments to develop sustainable conditions for student participation. PeRT’s multi-dimensional model enables the exploration of the nexus of relations, from the micro-level to the macro-level, and the educational system’s multi-faceted relational dimensions. However, it is essential to place the relationship between the teacher and the student at the core of teaching.

To conclude, this article’s presentation of PeRT as a new inclusive relational perspective is an invitation to scholars and practitioners to use the multi-relational model as creative inspiration to seek new knowledge and understanding about participation, accessibility and equity. Such cooperative relational work is an endeavour to understand togetherness in plurality and how democracy is taking place. Nothing is more important to our mutual future.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express special thanks to Rune Hausstätter for inspiration, and Girma Berhanu, Dennis Beach and Marianne Dovemark for their helpful and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ann-Louise Ljungblad

Ann-Louise Ljungblad is a Senior lecturer at the Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her research interests are in the field of Inclusive Education, Children's Rights, Relational Pedagogy and Mathematical Difficulties. She has a special interest in empirical classroom studies in the field of Special Education and diversity, participation, accessibility and equity.

Notes

1 Translated from Swedish: Pedagogiskt Relationellt Lärarskap (PeRL).

2 PeRT is an approach in line with the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

3 Biesta uses the work of Rancière (Citation1995, 41) and approaches democracy and inclusion with an understanding of democracy being sporadic situations that ‘happen’ from time to time.

4 The Bildung tradition and its theory derives from conceptions of good education and Menschwerdung, which are value-oriented rather than effect-oriented.

5 The notion of différance originates from Derrida (Citation2003, 144): ‘différance is not, does not exist, is not a present-being (on) in any form … it has neither existence nor essence. It derives from no category of being, whether present or absent.’

6 Theories about power, gender and laws can be included and used in research on micro-, meso- and macro-levels to capture different relational aspects of teaching.

References

- Ainscow, M., A. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. London: Routledge.

- Allan, J. 2009. “Teaching Children to Live with Diversity: A Response to Tocqueville on Democracy and Inclusive Education: A More Ardent and Enduring Love of Equality than of Liberty.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 24 (3): 245–247. doi: 10.1080/08856250903020104

- Arendt, H. 1998. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Armstrong, D., A. Armstrong, and I. Spandagou. 2011. “Inclusion: By Choice or by Chance?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (1): 29–39. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2010.496192

- Aspelin, J. 2014. “Beyond Individualised Teaching. A Relational Construction of Pedagogical Attitude.” Educational Inquiry 5 (2): 233–245. doi: 10.3402/edui.v5.23926

- Aspelin, J. 2017. “In the Heart of Teaching. A Two-dimensional Conception of Teachers’ Relational Competence.” Educational Practice and Theory 39 (2): 39–56. doi: 10.7459/ept/39.2.04

- Biesta, G. 2001. ““Preparing for the Incalculable.” Deconstruction, Justice, and the Question of Education.” In Derrida & Education, edited by G. Biesta, and D. Egéa-Kuehne, 32–54. London: Routledge.

- Biesta, G. 2002. “Bildung and Modernity: The Future of Bildung in a World of Difference.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 21 (4-5): 343–351. doi: 10.1023/A:1019874106870

- Biesta, G. 2006. Beyond Learning. Democratic Education for a Human Future. Boulder: Paradigm.

- Biesta, G. 2007. “Don’t Count Me in. Democracy, Education and the Question of Inclusion.” Nordic Studies in Education 27 (1): 18–29.

- Biesta, G. 2009. “Good Education in an Age of Measurement. On the Need to Reconnect with the Question of Purpose in Education.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation & Accountability 21 (1): 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

- Biesta, G. 2010. “Mind the Gap! Communication and the Educational Relation.” In No Education Without Relation, edited by C. Bingham, and A. Sidorkin, 11–22. New York: Peter Lang.

- Biesta, G. 2014. The Beautiful Risk of Education. Boulder: Paradigm.

- Biesta, G. 2017. “Education, Measurement and the Professions: Reclaiming a Space for Democratic Professionality in Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (4): 315–330. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1048665

- Bingham, C., and A. Sidorkin. 2010. No Education Without Relation. New York: Peter Lang.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Buber, M. 2011. Det Mellanmänskliga. Ludvika: Dualis.

- Derrida, J. 2003. “Différance.” In Deconstruction. Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies, edited by J. Culler, 141–166. London: Routledge.

- Emirbayer, M. 1997. “Manifesto for a Relational Sociology.” American Journal of Sociology 103 (2): 281–317. doi: 10.1086/231209

- Frelin, A. 2010. Teachers’ Relational Practices and Professionality. PhD diss., University of Uppsala.

- Gergen, K. 2009. Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Graham, L., and R. Slee. 2008. “Inclusion.” In Disability & the Politics of Education, edited by S. Gabel and S. Danforth, 81–101. New York: Peter Lang.

- Hattie, J. 2009. Visible Learning. A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

- Hausstätter, R. 2014. “In Support of Unfinished Inclusion.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 58 (4): 424–434. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2013.773553

- Hinsdale, M. 2016. “Relational Pedagogy.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.28.

- Klein, K., and S. Kozlowski. 2000. “From Micro to Meso: Critical Steps in Conceptualizing and Conducting Multilevel Research.” Organizational Research Methods 3 (3): 211–236. doi: 10.1177/109442810033001

- Levinas, E. 1998. Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Ljungblad, A.-L. 2016. Takt och hållning – en relationell studie om det oberäkneliga i matematikundervisningen [Tact and Stance – A Relational Study About the Incalculable in Mathematics Teaching]. PhD diss., Gothenburg Studies in Educational Sciences, 381. Gothenburg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Ljungblad, A.-L. 2020 (in progress). “Pedagogical Tactfulness Can Meet Diversity in Mathematics Teaching.” Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education.

- Ljungblad, A.-L., and H. Lennerstad. 2011. Matematik och respekt. Matematikens mångfald och lyssnandets konst. Stockholm: Liber.

- Løvlie, L. 2002. “The Promise of Bildung.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 36 (3): 467–486. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.00288

- Løvlie, L., 2007. “Takt, humanitet och demokrati.” In Erfarenheter av pragmatism, edited by Y. Boman et al., 77–103. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Margonis, F. 2007. “A Relational Ethic of Solidarity?” Philosophy of Education Archive, Featured Essays, 62–70.

- Mead, G. H. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Mitchell, D. 2014. What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education: Using Evidence-Based Teaching Strategies. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Noddings, N. 1999. “Care, Justice and Equity.” In Justice and Caring: The Search for Common Ground in Education, edited by M. Katz et al., 7–20. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Nordenbo, S.-E., M. Søgaard Larsen, N. Tiftikçi, E. Wendt, and S. Østergaard. 2008. Teacher Competences and Pupil Achievement in Pre-school and School. A Systematic Review Carried out for the Ministry of Education and Research, Oslo. Copenhagen: Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research, School of Education, University of Aarhus.

- Rancière, J. 1995. On the Shores of Politics. London/New York: Verso.

- Rosanvallon, P. 2009. Demokrati som problem. Stockholm: Tankekraft.

- Säfström, C.-A. 2005. Skillnadens pedagogik. Nya vägar i den pedagogiska teorin. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Sandvik, M. 2009. Jag har hittat mig själv och barnen. Barnträdgårdslärares professionella självutveckling genom ett pedagogisk-psykologiskt interventionsprogram. PhD diss., University of Åbo.

- Slee, R. 2011. The Irregular School: Schooling and Inclusive Education. London: Routledge.

- UNESCO. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action. On Special Needs Education. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- UNICEF. 2007. A Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All: A Framework for the Realization of Children’s Right to Education and Rights Within Education. New York: UNICEF.

- United Nations General Assembly. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577.

- von Hentig, H. 1996. Bildung. Wien: Carl Hanser.

- von Wright, M. 2006. “The Punctual Fallacy of Participation.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 38 (2): 159–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2006.00185.x

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Waitoller, F., and A. Artiles. 2013. “A Decade of Professional Development Research for Inclusive Education: A Critical Review and Notes for a Research Program.” Review of Educational Research 83 (3): 319–356. doi: 10.3102/0034654313483905

- Zittoun, T., A. Gillespie, F. Cornish, and C. Psaltis. 2007. “The Metaphor of the Triangle in Theories of Human Development.” Human Development 50 (4): 208–229. doi: 10.1159/000103361