ABSTRACT

Fostering equity by offering the best education possible to all students is one of the main goals of inclusive schooling. One instrument to implement individualised education is individualised education planning (IEP). IEP requires cooperation between special and regular teachers. From research on school leadership it is known that leadership styles are connected to the way, school leaders use their scope of action with respect to fostering collaboration. However, little is known about the relationship between the leadership of a school, the provision of structures for collaboration, and the implementation of IEP in an inclusive context. The article focuses on the question to what extent transformational (TL) and instructional leadership (IL) are connected to the provision of structures for collaboration and how TL and IL as well as structures for collaboration relate to the implementation of IEP directly and indirectly. Based on data of N = 135 German schools, a path model was calculated. It revealed medium relations between TL, IL, and structures for collaboration as well as a medium effect from structures to collaboration on implementation of IEP. The effect from TL towards implementation of IEP was fully mediated by structures for collaboration, while the effect from IL persisted.

Conceptual background

Individualised Education Plans (IEPs) are an important instrument to foster individualised education and the provision of adequate learning offers for children with special educational needs in regular classes (Smith Citation1990). In most western educational systems IEPs have long been a key element of inclusive education (Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010). In Germany, though, only with the ratification of the Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, did IEPs become a controversially discussed instrument for implementing inclusive education. In international comparison, this is rather late (Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010). In some German federal states they are obligatory. However, there is no meaningful accountability system to monitor their implementation. If and how IEPs are implemented within schools therefore depends on the specific school, especially the school leader, who can be seen as a gates keeper to implement inclusive education (Ainscow and Sandill Citation2010; Amrhein Citation2014). Despite the ratification of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008 and the requirement to implement inclusive education on the level of the specific school, school leaders in Germany lack specific instructions or guidelines for this task (Badstieber, Körper, and Amrhein Citation2018). School leaders are responsible for mediating between highly complex demands of inclusive education and the structures at the specific school within their scope of action (ebd.). The scope of action refers to, e.g. the allocation of resources and fostering of lesson development, as well as fostering cooperation between teachers and other pedagogical personnel. Moreover, school leaders in inclusive schools must ensure the improvement of learning opportunities for all children and especially for disadvantaged students, such as students with special educational needs (Kugelmass and Ainscow Citation2004). From research on school leadership in general it is known, that school leaders differ in terms of their leadership styles and that those leadership styles are connected to the way, school leaders use their scope of action.

Therefore, it can be assumed that schools differ in the way they implement individualised education planning and that those differences between schools are linked to the school’s leadership. Different actors, such as the regular class teacher and special teachers are involved in individualised education planning and the school leader needs to provide structures in order for them to collaborate. However, little is known about the relationship between leadership of a school, the provision of structures for collaboration, and the implementation of individualised education planning in inclusive primary and secondary schools. This article addresses this desiderate by investigating this relationship in an inclusive system in the state of Brandenburg, Germany, where children with and without special educational needs learn together in regular classes.

Individualised education planning

Different terms are used (e.g. Individualised Education Programme, Individualised Intervention Programmes, Learning Plans; see Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010) for IEPs. IEPs were first introduced legally binding as Individualised Education Programmes with the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) in the USA in 1975. The EAHCA defines five key elements of IEPs: a statement of current academic performance, a statement of annual goals, a statement of specific service provided for the student, and duration of the service, and criteria to evaluate if the goals were reached (EAHCA, Sec 4, 19). IEPs aim to support individualised instruction for children with special educational needs in order to provide them with adequate educational opportunities (Smith Citation1990). Despite early critiques, IEPs became a key element of inclusive education in many countries, e.g. most European countries, Australia, and Canada (Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010). Although adaptations to national educational systems produced variations in the specific design of the IEPs, the key elements defined in EAHCA still seem to play a major role internationally.

The implementation of individualised education planning [IEP] is not primarily bound by school laws but depends, as it is the case in Germany, to information provided by practically oriented publishers and not legally binding recommendations by the federal education ministries. This raises the following questions: Which aspects define the practical implementation of IEP theoretically and what is empirically known about the implementation of IEP, and, which school processes are theoretically associated with the implementation of IEP and what is known empirically about those mechanisms?

With regard to the implementation of IEP, the recommendations provided by the federal education ministry in Brandenburg emphasise that IEPs should be dynamic, not static documents: They should contain concrete learning goals and a fixed time frame, yet they can be altered if required (Federal Institute for School and Media Berlin-Brandenburg, LISUM Citation2010). They should be variable in form and criteria and have to be adapted to the needs of the specific student as well as the school’s culture (ibid.). The involvement of the students themselves in individualised education planning, monitoring, and evaluation, e.g. by documenting their learning process, is also seen as an important aspect of implementing IEP (Jones and Peterson-Ahmad Citation2017; Jung Citation2011; Cavendish and Connor Citation2018) Those assumptions are supported by the review on IEPs by Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby (Citation2010). Based on more than N = 190 studies from the USA, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa they summarise that IEP requires collaboration between different actors such as general and special teachers, the involvement of the students themselves as well as their parents. However, Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby (Citation2010) also found that the actual implementation, especially collaboration was evaluated as not sufficient within several studies.

In a very recent study, Moser Opitz, Pool Maag, and Labhart (Citation2019) who investigated the implementation status of IEPs in Switzerland confirmed this assessment: They found that only three quarters of teachers reported that IEPs existed in their schools, despite all schools were required to implement IEPs. With regard to different aspects of the implementation, research is rare. Moser Opitz, Pool Maag, and Labhart (Citation2019) stated, that around 80% of teachers reported to modify learning goals within the IEPs and 76% reported to adapt the IEPs regularly. Paccaud and Luder (Citation2017) conducted a study in Switzerland on the precision of the documented learning goals. They found that the quality of learning goals was rather low with respect to measurability and defined time frames.

Little is known about factors that influence the different aspects of the implementation of IEP, such as the involvement of different actors, the definition of learning goals, and the dynamic of IEPs. However, collaboration between different actors is emphasised as an important aspect (Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010; LISUM Citation2010; Eller and Grimm Citation2008). The more different actors are involved, the more likely is the perception of the specific student in a holistic approach (Nilsen Citation2017). A holistic view of the student should foster different aspects of the implementation of IEP. Hunt et al. (Citation2003) using standardised observations and interviews found that collaborative implementation of IEP raised the academic performance and participation of low achieving students and students with special educational needs. However, the results of Moser Opitz et al.’s study (Citation2019) pointed to a lack of collaboration between regular and special teachers as regular teachers seemed to be partly unaware of the existence of IEPs in their schools. In line with these results Nilsen (Citation2017) as well as Şenay Ilik and Konuk Er (Citation2018) found that teachers as well as special teachers considered collaborative individualised education planning to happen less often than necessary.

Moreover, studies investigating the involvement of different actors in individualised education planning stress differences between actors, e.g. between special and regular teachers, or between schools and parents, as well as a lack of preparation of special teachers to collaborate with parents (Jung Citation2011; Jones and Peterson-Ahmad Citation2017; Mitchell, Morton, and Hornby Citation2010). While most of the rarely available studies on explanatory factors focus on individuals, a qualitative study conducted by Nilsen (Citation2017) among Norwegian teachers revealed the importance of structural factors. He interviewed the teachers asking for ‘key framework factors’ in order to foster collaborative individualised education planning (213). The teachers mentioned ‘better opportunities for teamwork, with regular meetings between class teachers and the pupil’s special education teachers’ (Nilsen Citation2017, 213).

It can be concluded, that the provision of structures for collaboration within schools seems to be a crucial factor when it comes to implementation of IEP. In order to foster collaboration between teachers and special teachers, school leaders play an important role by providing the necessary infrastructure. This article seeks to understand to what extent school leaders may influence the implementation of IEP directly and indirectly by the provision of structures for collaboration.

School leadership in inclusive schools

Against the backdrop of inclusive education, school leadership is associated with promoting equity (Blackmore Citation2006; Precey Citation2011). The main task of school leaders is the promotion of the best education for all students and especially disadvantaged students (Dyson Citation2010; Kugelmass and Ainscow Citation2004; Precey Citation2011). To achieve this, the school leader needs to develop his or her employee’s motivation, skills and working conditions with respect to a diverse student body (Amrhein Citation2014; Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins Citation2008; Ingram Citation1997). From general research on school leadership it is known, that four sets of leadership qualities seem to be effective: building vision and setting directions, redesigning the organisation, understanding and developing people, as well as managing the teaching and learning programme (Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins Citation2008). With respect to building vision and setting directions and redesigning the organisation, it is assumed that those leadership practices influence motivation and commitment of the staff, while understanding and developing people as well as managing the teaching and learning programme aim primarily towards building knowledge and skills, teachers need in order to fulfil the school’s goals and to develop effective instructional conditions (Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins Citation2008).

Within the framework of inclusive education, two main components of leadership can be extracted from the literature associated with promoting inclusive education: Collaborative processes and lesson development. Dorczak (Citation2011) defines the valuing of collaboration as the key aspect of inclusive leadership styles. In a systematic literature review based on N = 41 reports written in the English language, Dyson (Citation2010) found that collaborative processes between teachers and pedagogical personnel but also in terms of decision making were crucial in order to develop inclusive schools. Comparing international leadership practices in inclusive schools on the basis of case studies, Kugelmass and Ainscow (Citation2004) concluded that leadership in inclusive schools is marked by a collaborative nature and that school leaders play a major role in supporting collaboration. Their conclusion was build upon a comparative analysis in the USA, England and Portugal. The second main component, the focus on lesson development aims to deal with a diverse student body and to promote a school culture which enhances professional teacher development (Blackmore Citation2006). School leaders in inclusive schools have to promote collaborative processes and lesson development with the goal of the best education for all students. As said before, school leaders differ in the way they lead a school. With respect to the relation between school leadership and the promotion of collaborative processes and lesson development, research on different leadership styles, especially from the UK, suggest that transformational and instructional leadership practices are most promising (Day and Sammons Citation2013).

In terms of promoting collaborative processes, the transformational leadership style seems to be most adequate. Transformational leadership aims to understand and develop people to foster productive social relations. It includes leadership practices such as supporting teachers, recognising the personnel’s work, and fostering participation (Day and Sammons Citation2013). Lesson development is particularly associated with the instructional leadership style. Instructional leadership emphasises the importance of learning goals as well as the coordination between teachers’ activities and those goals (ibid.). Concrete practices are for example coordinating the teaching programme, providing advice for teachers with respect to their teaching, and ensuring systematic monitoring of the implementation of school goals (ibid.).

Empirical findings from different countries, e.g. Turkey, the USA, Germany, and Denmark suggest that leadership practices and teacher collaboration are related (Gumus, Bulut, and Bellibas Citation2013; Szczesiul and Huizenga Citation2014). Pietsch et al. (Citation2016) investigated the influence of leadership on working conditions, including collaboration between teachers in a sample of N = 1663 teachers in Germany. They found that instructional as well as transformational leadership had a significant positive effect on collaboration. Another study by Honingh and Hooge (Citation2014) revealed a strong connection between perceived school leader support, that was operationalised using practices referring to transformational leadership, and collaboration among N = 614 teachers in Dutch primary and secondary schools. With respect to instructional leadership, Goddard et al. (Citation2015) found a strong connection to teacher collaboration. However, there is a lack of research concerning the connection between transformational and instructional leadership and the promotion of collaborative structures in inclusive schools. With respect to lesson development, empirical studies conducted in regular schools suggest, that the instructional leadership style is especially effective. A meta-analysis by Robinson, Lloyd, and Rowe (Citation2008) including 22 empirical studies concluded that instructional leadership had an approximately four times higher effect on student outcomes than transformational leadership. Ingram (Citation1997) pointed out, that transformational leadership is also important for school and lesson development in an inclusive setting. It is assumed and empirically verified that the effect of leadership styles on student outcomes is an indirect one that is mediated by the school leader’s influence on processes within schools (Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins Citation2008).

Research questions and hypotheses

Within the context of inclusive education, fostering equity by offering the best education possible to all students is one of the main goals of schooling. One instrument to implement individualised education for all students are IEPs. Based on the review of theoretical and empirical literature we argue the following: Leadership is connected to the provision of collaborative processes. Those processes are in turn connected with the implementation of IEP. Moreover, indirect and direct effects of instructional and transformational leadership styles on the implementation of IEP are expected.

IEPs can be considered a key aspect of the development of inclusive processes in schools with the aim to foster students’ performance. It is likely that the school leaders’ orientation towards teachers’ professional development and the teaching and learning programme is connected to those inclusive processes. It can further be assumed, that the instructional as well as the transformational leadership style is positively connected to the implementation of IEP in inclusive schools. As the relation between instructional leadership and student outcomes seems to be stronger than between transformational leadership and student outcomes, one can assume, that there is a stronger link between instructional leadership and the implementation of IEP. As argued above, the implementation of IEP should be connected to the promotion of collaborative structures. As individualised education planning needs collaborative processes between regular teachers and special teachers, it is likely that transformational leadership and instructional leadership are indirectly positively connected to the implementation of IEP: As argued above, leadership practices, especially transformational leadership, are positively related to teacher collaboration. Within inclusive schools it can therefore be assumed, that transformational and instructional leadership are connected positively to the promotion of collaborative structures. As transformational leadership aims directly towards the promotion of positive social relations within schools and to developing people, transformational leadership should have a stronger effect on the promotion of collaborative structures. Hence, its effect on the implementation of IEP should be primarily indirect via the promotion of collaborative structures while the effect of instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP should be primarily directly.

To test those argumentative relationships, the following research questions were addressed and the following hypotheses were tested in the present study:

Are transformational leadership and instructional leadership linked directly to the provision of structures for collaboration and the implementation of IEP in inclusive schools?

H1: Transformational leadership and instructional leadership are positively directly connected to the implementation of IEP. The direct effect of instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP is stronger than the direct effect of transformational leadership.

H2: Transformational leadership and instructional leadership are positively connected to the provision of structures for collaboration. The effect of transformational leadership on the provision of structures for collaboration is stronger than the effect of instructional leadership.

H3: The provision of structures for collaboration is positively connected to the implementation of IEP.

Is the connection between transformational leadership, instructional leadership, and the implementation of IEP mediated by the provision of structures for collaboration?

H4: There is an indirect effect from instructional leadership to the implementation of IEP indicating mediation.

H5: There is an indirect effect from transformational leadership to the implementation of IEP indicating mediation.

H6: The effect of transformational leadership on implementation of individualised education planning is fully mediated by structures for collaboration while the effect from instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP is not.

To what extent can the implementation of IEP be explained by the provision of structures for collaboration and transformational and instructional leadership?

To what extent can the provision of structures for collaboration be explained by transformational and instructional leadership?

Method

Design and sample

Data was used from the first wave (2019) of a longitudinal research project investigating the contexts and characteristics of successful inclusive primary and secondary schooling in the federal state of Brandenburg, Germany. Within the framework of this investigation, school leaders of all N = 184 participating schools were asked to fill in an online-questionnaire. The response rate was 73.4%. The final sample consisted of N = 135 school leaders. From N = 135 school leaders, 20.7% were male, and 79.3% were female. They had M = 30.87 (SD = 8.99) years of school experience in total, M = 13.87 (SD = 10.17) years of experience as a school leader, and M = 10.99 (SD = 8.87) years of experience as a school leader at the sample school.

Instruments and variables

The online-questionnaire was used to assess the following variables, where all items were answered on a scale ranging from 1 = does not apply at all to 4 = fully applies.

Transformational leadership was assessed using the human resources scale from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA, Ramm et al. Citation2006). The scale consisted of N = 8 items (e.g. ‘I create a trustworthy atmosphere by fostering open and cooperative social relations.´) and had a good reliability (α = .823).

Instructional leadership was assessed following the scale used in PISA 2009 (Hertel et al. Citation2014). The adapted scale consisted of N = 8 items (e.g. ‘I use students’ assessment results to develop the school’s educational goals.’) and was reliable (α = .804).

Structural conditions for collaboration was assessed using N = 4 items (e.g. ‘Time for collaboration, for example for lesson planning and meetings, is a regular part of working time and is integrated in the regular school day.’). The scale was sufficiently reliable (α = .724).

Implementation of IEP was assessed using a scale consisting of N = 11 items. It was developed within the framework of the research project. The items were developed with relation to the recommendations given by the LISUM (Citation2010). shows the items, their means, standard deviations, and precisions.

Table 1. Means, standard deviation, and precision of items to assess the implementation of IEP.

In order to form a one-dimensional scale to assess the implementation of individualised education planning, item 10 was excluded from further analyses due to its low precision. The remaining N = 10 items formed a reliable scale (α = .756).

All scales were created as mean score indices of the constituting scale variables. Their means and standard deviations are documented in .

Table 2. Descriptive of variables.

Statistical analyses

In order to test the hypotheses, a path model was specified using Mplus 7 (Muthén and Muthén Citation2012). The paths between the variables were specified in accordance with the hypotheses: transformational and instructional leadership were independent variables related to structures for collaboration, as well as to the implementation of IEP. Structures for collaboration was specified as mediating variable between the effect from instructional and transformational leadership on the implementation of IEP. Direct and indirect effects were computed. In order to test, if structures for collaboration had a significant mediating effect on the relation between leadership and individualised education planning, the significance of the indirect paths was computed (Geiser Citation2011). In order to test, if the effect from transformational leadership or instructional leadership respectively on the implementation of IEP was fully mediated by structures for collaboration, two path models with no specified direct effect from transformational leadership or instructional leadership respectively on the implementation of IEP were tested against the original model (Geiser Citation2011). To assess the model fit we used the following fit statistics as recommended by Geiser (Citation2011): Chi²-test, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). Missing values were replaced using full information maximum likelihood as implemented in Mplus 7 (Muthén and Muthén Citation2012).

Results

shows the mean values and standard deviations of and the correlations between transformational leadership, instructional leadership, structures for collaboration, and the implementation of IEP.

School leaders reported to use a high amount of transformational as well as a medium amount of instructional leadership practices. The structures for collaboration provided were positively rated. Moreover, the implementation of IEP was rated at a medium level.

The correlations between the variables point to positive medium relations between transformational leadership, instructional leadership, the structures for collaboration, and the implementation of IEP.

Path model

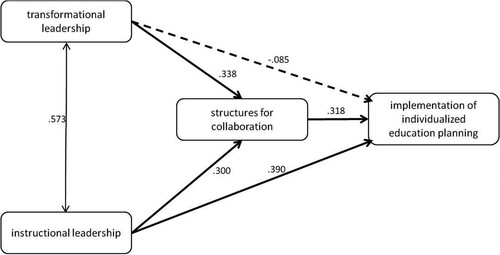

shows the fully standardised solution of the saturated path model.

Figure 1. Path model to estimate the relations between school leadership, structures for collaboration and individualised education planning.

Annotations. All coefficients were standardised; dotted arrow = p > .05; solid arrow = p < .05.

With respect to H1, that transformational leadership (TL) and instructional leadership (IL) both had a direct effect on the implementation of IEP (IIEP), the model shows that this hypothesis has to be partly rejected: Taking into account the structures for collaboration, there was no significant relation between transformational leadership and the implementation of IEP (βTL-IIEP = -.085, SETL-IIEP = .091, pTL-IIEP= .352). On the contrary, there was a direct positive effect from instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP when taking the provision of structures for collaboration into account (βIL-IIEP = .390, SEIL-IIEP = .087, pIL-IIEP < .001). Thus, instructional leadership had a larger direct effect on the implementation of IEP than transformational leadership.

The second hypotheses (H2) stating a positive relation between transformational leadership and instructional leadership and the provision of structures for collaboration can be verified within the path model: Transformational and instructional leadership both had a medium positive effect on structures for collaboration; the effect from transformational leadership on the implementation of IEP was slightly stronger (βTL-ST= .338, SETL-ST = .083, pTL-ST < .001; βIL-ST= .300, SEIL-ST = .084, pIL-ST < .001).

Moreover, there was a positive medium effect from structures for collaboration on the implementation of IEP (βST-IIEP= .318, SEST-IIEP = .084, pST-IIEP < .001). Therefore, H3 can be verified.

The second research question focused on a mediating effect of structures for collaboration between leadership practices and the implementation of IEP. In order to answer this research question, indirect and total effects and their level of significance were computed. provides an overview of the total and the total indirect effects from leadership practices to the implementation of IEP.

Table 3. Total and total indirect effects from leadership practices on the implementation of IEP.

With respect to H4 and H5, that there is an indirect effect from instructional leadership and transformational leadership to the implementation of IEP indicating a mediation, reveals that there were small significant indirect effects from both instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP (verification of H4) as well as from transformational leadership on the implementation of IEP (verification of H5).

Regarding H6, that the effect of transformational leadership on the implementation of IEP is fully mediated by structures for collaboration while the effect from instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP is not, two more path models were specified. Those path models were not saturated and hence allowed to compare the model fit. The specification of the path model without a direct effect from transformational leadership to the implementation of IEP had a good fit (Chi² = 0.859, df = 1, p = .354; CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.007; RMSEA = 0.000, CI = 0.000, 0.221, p = .430; SRMR = 0.014), while the specification of a path model without a direct effect from instructional leadership on the implementation of IEP did not (Chi² = 17.395, df = 1, p = .000; CFI = 0.834; TLI = 0.171; RMSEA = 0.348, CI = 0.217, 0.501, p = .000; SRMR = 0.064). This indicates a full mediation of the effect from transformational leadership on the implementation of IEP by the structures for collaboration. H6 can therefore be verified.

The third research question focused on the explanation of variance in the implementation of IEP by the provision of structures for collaboration and leadership practices. The path model revealed that nearly one third (R² = .318) of variance of the implementation of IEP was explained. Focussing the explanation of variance in structures for collaboration, the model explained 32% of the variance.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the leadership of a school, the provision of structures for collaboration, and the implementation of individualised education planning in primary and secondary schools in an inclusive system in Germany. Two different, yet related, sets of leadership practices were focused: transformational leadership and instructional leadership. In line with prior research, we found medium to strong connections between school leadership and collaboration (Pietsch et al. Citation2016; Honingh and Hooge Citation2014; Goddard et al. Citation2015). However, we did not investigate the actual collaboration but the structures provided by the school leader for collaboration. With respect to individualised education planning, the structures for collaboration were identified as an important prerequisite (Nilsen Citation2017). Our study revealed that structures for collaboration were indeed important for the implementation of individualised education planning: The structures provided for collaboration fully mediated the effect from transformational leadership on implementation of individualised education planning. Moreover, they had a medium positive effect on the implementation of individualised education planning.

Further, the results show that the school leader can be seen as a gates keeper to implement IEP (Ainscow and Sandill Citation2010). Around one third of variance in the implementation of individualised education planning was explained by the school leaders’ practices and the structures for collaboration he or she provided. This points to the school leaders’ influence on processes in schools. As high quality IEPs and their collaborative implementation seem to be associated with greater student learning outcomes (Hunt et al. Citation2003), the school leader is likely to influence student outcomes in inclusive schools indirectly. However, the impact of IEPs on student outcomes needs further investigation.

Before further implications of the study can be made, its limitations have to be taken into account. Despite path models being designed and used to evaluate causal relations (Tarka Citation2018), casual assumptions have to be made with caution. Theoretically, it is more likely that leadership practices precede implementation of individualised education planning rather than the other way around, however we used a cross-sectional design that cannot prove this assumption. It is conceivable that the implementation of individualised education planning might affect structures for collaboration, as it creates a need to collaborate and therewith force the school leader to provide respective structures. Nonetheless, against the backdrop of literature on school leadership and individualised education planning the assumed relationships were reasonable. Yet, they should be tested using longitudinal designs.

As mentioned before we did not investigate actual collaboration but structures for collaboration. Moreover, all information stem from school leaders’ self-reports, which may have led to a positive bias. Future studies should therefore connect structural prerequisites with processes in schools on the level of the teachers and students to get better insights into the school leaders’ influence on school processes to implement inclusive education. Moreover, observational studies could also be effective.

Finally, the sample has to be considered: while the included schools may represent a census of all inclusive schools, they are not a representative sample of all primary and secondary schools in the federal state of Brandenburg, Germany. Moreover, for the complexity of the model, the sample was rather small. Therefore, actual effects might have been underestimated.

Despite those limitations our study provides new and valuable insights into the school leaders’ role in implementing inclusive education. Both, transformational and instructional leadership practises have an overall positive effect on the implementation of individualised education planning. This result is in line with and empirically supports theoretical frameworks stressing collaborative processes and lesson development as main components of inclusive leadership (Blackmore Citation2006; Dorczak Citation2011; Dyson Citation2010; Kugelmass and Ainscow Citation2004). Moreover, it is in line with previous empirical studies investigating the relationship between leadership, collaboration and lesson development (Goddard et al. Citation2015; Gumus, Bulut, and Bellibas Citation2013; Honingh and Hooge Citation2014; Pietsch et al. Citation2016). With respect to transformational leadership the study showed, however, that the positive effect is only due to the positive impact transformational leadership had on the provision of structures for collaboration. When controlling for this effect, transformational leadership was not related to the implementation of individualised education planning. This result is in line with prior research identifying bigger effects form instructional than transformational leadership (Robinson, Lloyd, and Rowe Citation2008). Instructional leadership, on the other hand, had a positive effect on the implementation of individualised education planning that was partly mediated by the structures for collaboration. Therefore, a combination of transformational and instructional leadership is a good way to support the provision of collaborative structures and thereby the implementation of inclusive education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jennifer Lambrecht

Dr. Jennifer Lambrecht is a researcher in the field of educational sciences. She received her PhD in Education from the University of Potsdam, Germany. Her work is broadly concerned with inclusive education and the quality of learning environments.

Jenny Lenkeit

Jenny Lenkeit is a researcher at the University of Potsdam, Department of Primary School Education. She received her PhD in Education from the University of Hamburg. Her work is broadly concerned with educational inequalities in different national and internationally comparative contexts. In her current research she investigates factors related to successful inclusive learning settings.

Anne Hartmann

Anne Hartmann is a researcher at the University of Potsdam, Department of Primary School Education. She received her Master of Science in Psychology from the Humboldt University of Berlin. She is currently investigating the social participation and personality development of adolescents in the context of inclusive learning.

Antje Ehlert

Antje Ehlert is a full professor of inclusive education/special educational needs with focus on learning at the University of Potsdam. Her research focuses on the acquisition of mathematical competences, the diagnostic and interventions. She is also interested in inclusive teaching and school development.

Michel Knigge

Michel Knigge is full professor for rehabilitation psychology at Humboldt University Berlin. Before this, he worked at the University of Potsdam as a full professor for inclusion and organisational development. Important fields of his research are school, organisational, professional, and identity development as well as the promotion of learning and well being for all in school and beyond.

Nadine Spörer

Nadine Spörer is a professor in the field of educational psychology at the University of Potsdam, Germany. Her main research interests deal with self- and co-regulated learning in the context of fostering reading comprehension and with antecedents and consequences of inclusive learning in primary and secondary school. With regard to inclusive learning settings, Spörer conducts longitudinal classroom studies and examines the interplay of instructional methods and social inclusion of students with and without special educational needs.

References

- Ainscow, M., and A. Sandill. 2010. “Developing Inclusive Education Systems: The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (4): 401–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903 .

- Amrhein, B. 2014. “Inklusive Bildungslandschaften: Neue Anforderungen an die Professionalisierung von Schulleitungen [Inclusive Education: New Challenges towards the Professionalization of School Leaders].” In: Jahrbuch Schulleitung. Befunde und Impulse zu den Handlungsfeldern des Schulmanagements, edited by Stephan Gerhard Huber. Köln: Wolters Kluwer.

- Badstieber, B., A. Körper, and B. Amrhein. 2018. “Schulleitungen im Kontext inklusiver Bildungsreformen [School Leaders in the Context of Inclusive Educational Reforms].” In: Handbuch schulische Inklusion, edited by Tanja Sturm and Monika Wagner-Willi, 235–249. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Blackmore, J. 2006. “Deconstructing Diversity Discourses in the Field of Educational Management and Leadership.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 34 (2): 181–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143206062492 .

- Cavendish, W., and D. Connor. 2018. “Toward Authentic IEPs and Transition Plans: Student, Parent, and Teacher Perspectives.” Learning Disability Quarterly 41 (1): 32–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948716684680

- Day, C., and P. Sammons. 2013. Successful Leadership: A Review of the International Literature. CfBT Education Trust, University of Nottingham.

- Dorczak, R. 2011. “School Organisational Culture and Inclusive Educational Leadership.” Contemporary Management Quarterly/Wspólczesne Zarzadzanie 2: 45–55. https://issuu.com/ijcm/docs/2-2011.

- Dyson, A. 2010. “Developing Inclusive Schools: Three Perspectives From England.” DDS – Die Deutsche Schule 102 (2): 115–129. https://www.dds.uni-hannover.de/fileadmin/schulentwicklungsforschung/DDS_PDF-Dateien/DDS-Dyson_Inclusion_English.pdf.

- Eller, U., and W. Grimm. 2008. Individuelle Lernpläne für Kinder. Grundlagen, Ideen und Verfahren für die Grundschule [Individualized Education Plans for Children. Basics, Ideas and Methods for Primary School]. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz.

- Geiser, C. 2011. Datenanalyse mit Mplus: eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung [Analyzing Data with MPlus: An Introduction]. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- Goddard, R., Y. Goddard, E. S. Kim, and R. Miller. 2015. “A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis of the Roles of Instructional Leadership, Teacher Collaboration, and Collective Efficacy Beliefs in Support of Student Learning.” American Journal of Education 121 (4): 501–530. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/681925

- Gumus, S., O. Bulut, and M. S. Bellibas. 2013. “The Relationship Between Principal Leadership and Teacher Collaboration in Turkish Primary Schools: A Multilevel Analysis.” Education Research and Perspectives 40 (1): 1–29.

- Hertel, S., J. Hochweber, D. Mildner, B. Steinert, and N. Jude. 2014. PISA 2009 Skalenhandbuch [PISA 2009 The Scales Handbook]. Münster: Waxmann.

- Honingh, M., and E. Hooge. 2014. “The Effect of School-Leader Support and Participation in Decision Making on Teacher Collaboration in Dutch Primary and Secondary Schools.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 42 (1): 75–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213499256 .

- Hunt, P., G. Soto, J. Maier, and K. Doering. 2003. “Collaborative Teaming to Support Students at Risk and Students With Severe Disabilities in General Education Classrooms.” Exceptional Children 69 (3): 315–332. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290306900304

- Ingram, P. D. 1997. “Leadership Behaviours of Principals in Inclusive Educational Settings.” Journal of Educational Administration 35 (5): 411–427. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/09578239710184565

- Jones, B. A., and M. B. Peterson-Ahmad. 2017. “Preparing New Special Education Teachers to Facilitate Collaboration in the Individualized Education Program Process Through Mini-Conferencing.” International Journal of Special Education 32 (4): 697–707.

- Jung, A. W. 2011. “Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and Barriers for Parents from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds.” Multicultural Education 19 (3): 21–25.

- Kugelmass, J., and M. Ainscow. 2004. “Leadership for Inclusion: A Comparison of International Practices.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 4 (3): 133–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00028.x .

- Leithwood, K., A. Harris, and D. Hopkins. 2008. “Seven Strong Claims about Successful School Leadership.” School Leadership and Management 28 (1): 27–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060

- LISUM (Federal Institute for School and Media Berlin-Brandenburg). 2010. Förderplanung im Team [Education Planning in Teams]. Ludwigsfelde-Struveshof: LISUM.

- Mitchell, D., M. Morton, and G. Hornby. 2010. Review of the Literature on Individual Education Plans: Report to the New Zealand Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/102216/Literature-Review-Use-of-the-IEP.pdf.

- Moser Opitz, E., S. Pool Maag, and D. Labhart. 2019. “Förderpläne: Instrument zur Förderung oder ‘bürokratisches Mittel’? Eine empirische Untersuchung zum Einsatz von Förderplänen [Individual Education Plans: An Important Tool for Instruction or a Bureaucratic Exercise? An Empirical Study on the Implementation of Individual Education Plans].” Empirische Sonderpädagogik 11 (3): 210–224.

- Muthén, L. K., and B. O. Muthén. 2012. Mplus User's Guide Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables (7. Auflage). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nilsen, S. 2017. “Special Education and General Education – Coordinated or Separated? A Study of Curriculum Planning for Pupils with Special Educational Needs.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (2): 205–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1193564 .

- Paccaud, A., and R. Luder. 2017. “Participation Versus Individual Support: Individual Goals and Curricular Access in Inclusive Special Needs Education.” Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology 16 (2): 205–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.16.2.205 .

- Pietsch, M., M. Lücken, F. Thonke, S. Klitsche, and F. Musekamp. 2016. “Der Zusammenhang von Schulleitungshandeln, Unterrichtsgestaltung und Lernerfolg: Eine argumentbasierte Validierung zur Interpretier- und Nutzbarkeit von Schulinspektionsergebnissen im Bereich Führung von Schulen [The Relation of School Leadership, Instructional Quality and Student Achievement. An Argument Based Validation Study on the Interpretations and Uses of School Inspection Results Regarding School Leadership].” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 19 (3): 527–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-016-0692-4 .

- Precey, R. 2011. “Inclusive Leadership for Inclusive Education – the Utopia Worth Working Towards.” Contemporary Management Quarterly/Wspólczesne Zarzadzanie 2: 35–44.

- Ramm, G., M. Prenzel, J. Baumert, W. Blum, R. Lehmann, D. Leutner, M. Neubrand, et al. ed. 2006. PISA 2003: Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente [PISA 2003. Documentation]. Münster: Waxmann.

- Robinson, V. M. J., C. A. Lloyd, and K. J. Rowe. 2008. “The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes: An Analysis of the Differential Effects of Leadership Types.” Educational Administration Quarterly 44 (5): 635–674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509 .

- Şenay Ilik, Ş, and R. Konuk Er. 2018. “Evaluating Parent Participation in Individualized Education Programs by Opinions of Parents and Teachers.” Journal of Education and Training Studies 7 (2): 76–83. doi: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v7i2.3936

- Smith, S. W. 1990. “Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) in Special Education - From Intent to Acquiescence.” Exceptional Children 57 (1): 6–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299005700102

- Szczesiul, S., and J. Huizenga. 2014. “The Burden of Leadership: Exploring the Principal’s Role in Teacher Collaboration.” Improving Schools 17 (2): 176–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480214534545 .

- Tarka, P. 2018. “An Overview of Structural Equation Modeling: its Beginnings, Historical Development, Usefulness and Controversies in the Social Sciences.” Quality & Quantity 52 (1): 313–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0469-8.