ABSTRACT

This article presents the evaluation of a two-year action research project in biology and mathematics teaching involving a primary school and a university in Sweden. The aim of the study was to contribute knowledge about a school–university intersection as a professional learning arena. The teachers’ conceptions about the project implementation, the impact on their learning, teaching practices and pupil learning were made explicit by focus group interview. The evaluation revealed that several motivating factors in this specific learning community – the relevance of the project and connection to the continuing education course, mentors from university, planning tools and time for collaboration – were critical for project implementation and for professional learning to occur. Furthermore, it indicated how teacher learning and teaching practices were related to pupil learning in the professional learning community. The results are also discussed in the light of new research on teachers’ work identity and self-reported health.

Introduction

The importance of student presence in teacher professional development research is highlighted by various researchers (Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008; Hairon et al. Citation2015; Margolis, Durbin, and Doring Citation2017). Teacher professional development is about teachers learning and transforming their knowledge into classroom practice for the benefit of their students’ understanding. This is a process which requires both cognitive and emotional contribution and includes a willingness and capacity to examine where one stands in terms of ideas and convictions (Avalos Citation2011). Earlier research points out the importance for teachers to participate actively in Professional Learning Communities (PLC). PLCs seem to be critical in high-quality professional development (Little Citation2006; Stoll et al. Citation2006; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008; Borko, Jacobs, and Koellner Citation2010). The communities must offer possibilities for knowledge sharing anchored in practical problems experienced by teachers (Darling-Hammond and McLaughlin Citation2011). Researchers claim (Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008; Hairon et al. Citation2015) that PLCs should also be able to describe outcomes in terms of data indicating changes in teaching practices and improved student learning.

School–university action research can be a powerful form of teacher learning as well as researcher learning (Sagor Citation2010). Action research commonly originates from problematic areas identified by teachers themselves and thereby helps teachers to gain insight into their practices and their professional development (Sagor Citation2010). This type of collaboration may create a new kind of knowledge bridging theory and practice by producing more contextualized theory and more theoretically grounded practice for the benefit of student achievement (Darling-Hammond and McLaughlin Citation2011).

This article is the third one to describe a two-year school–university action research project in biology and mathematics teaching in a primary school in Sweden. It presents the evaluation of the whole project. The aim is to contribute knowledge about the school–university intersection as a professional learning arena.

Project background

A short presentation of the project background is now given. The first article (Kellner and Attorps Citation2015) provides insights into the teachers’ general concerns and instructional needs in biology and mathematics teaching. From concerns articulated by the teachers, three instructional needs emerged: (1) to make subject progression, especially in biology, and pupil learning more visible, (2) to develop mathematics teaching in order to change pupils’ views of the subject, and (3) to develop teachers’ Subject Matter Knowledge and teaching in an ongoing collaborative process (Kellner and Attorps Citation2015). In the second article (Attorps and Kellner Citation2017) the impacts of the project on teaching practices and pupil learning are described. Some concrete examples are given on how the PLC influenced the teaching practices as well as pupil learning.

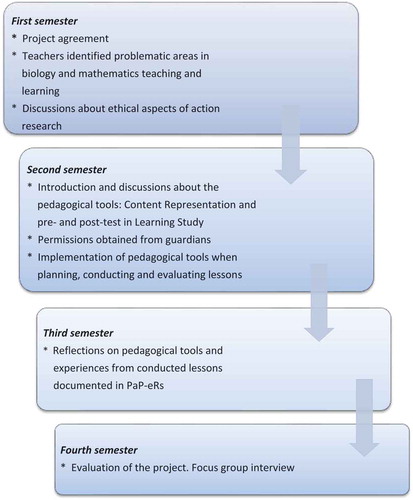

To be able to understand the timetable and the content of the project (), the pedagogical tools used by the teachers during the project are described below, and can be studied in more detail in Kellner and Attorps (Citation2015) and Attorps and Kellner (Citation2017).

The participants used Content Representation (CoRe), developed by Loughran et al. (Loughran, Mulhall, and Berry Citation2004; Loughran, Berry, and Mulhall Citation2012) as a tool when planning and reflecting on their teaching. According to Kind (Citation2009) this tool can be used to gain a unique insight into teacher Pedagogical Content Knowledge and practices relating to specific topics and was therefore chosen for this project. Although there is no universal definition of the Pedagogical Content Knowledge construct (e.g. Shulman Citation1986, Citation1987; Marks Citation1990; Magnusson, Krajcik, and Borko Citation1999; Ball, Thames, and Phelps Citation2008), researchers argue that the concept can be useful in analysing the professional practices of teachers (Abell Citation2008; Kind Citation2009). In the tool Content Representation, important concepts (ideas) are tabulated against different aspects of Pedagogical Content Knowledge, for example: ‘what you intend that students should learn about this concept (idea)’, ‘why it is important for students to know this concept’ and ‘the difficulties/limitations connected with teaching this concept’ (Loughran, Mulhall, and Berry Citation2004). Content Representation was presented to teachers as a blank table for completion. The advantage of this tool is that it makes the unstated nature of Pedagogical Content Knowledge explicit in a specific subject area. It was used as a pedagogical and collaborative tool helping teachers to identify important aspects of the content and conceptions about teaching the specific area. This tool provides ways of connecting the ‘why’ and ‘what’ of the content to be taught with the pupils who are to learn that content. After lessons were conducted, teachers’ experiences were documented in a narrative document called Pedagogical and Professional-experience Repertoire (PaP-eR), written in teachers’ voices and then annotated by researchers. This document is linked to Content Representation and highlights the connection between Subject Matter Knowledge and Pedagogical Content Knowledge, and describes the decisions underpinning the teacher’s actions intended to help the learners better understand the content (Loughran, Mulhall, and Berry Citation2004; Bertram and Loughran Citation2012).

Another tool in the project consisted of pre- and post-tests in the learning study-inspired cycle (Marton and Pang Citation2006; Pang and Ling Citation2012). Learning study correlates with many of the aspects promoted by Content Representation and the tools were used together to create a synergistic effect. Pre- and post-tests made pupil pre-knowledge and learning explicit. Participants in a learning study generally apply a learning theory called variation theory in the process of planning, conducting and reviewing lessons (Marton and Pang Citation2006; Pang and Ling Citation2012). A significant feature of variation theory is its strong focus on the object of learning (e.g. mathematical patterns or photosynthesis). Learning study is a cyclic process and starts with choosing and defining the object of learning in a specific subject area. In this project teachers’ experiences were taken as a starting point when completing Content Representation and for designing pre-tests used for diagnostic purposes. The results were then used when planning lessons, and after the conducted lessons the experiences and results from post-tests were analysed by teachers and researchers. In the project Content Representation and the results from the tests were used to plan and revise activities in biology and mathematics teaching throughout the school year.

Aim

In this article the evaluation of an action research project in biology and mathematics teaching is presented. The aim of our study is to contribute knowledge about a school–university intersection as a professional learning arena. The following questions guided our study:

What factors did the teachers consider as critical for project implementation?

How did the teachers conceive the impact of the project on their learning and teaching practices as well as pupil learning?

Theoretical framework for the evaluation of the project

The research field of professional development is moving towards the notion of professional learning, which emphasizes the active learning role that teachers play in changing their knowledge bases and practices, with the intention of promoting student achievement (Little Citation2006; Stoll et al. Citation2006; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008; Borko, Jacobs, and Koellner Citation2010; Timperley Citation2011; Bleicher Citation2014). Timperley (Citation2011, 5) states that: ‘One of the critical differences between the two terms is that professional learning requires teachers to be seriously engaged in their learning whereas professional development is often seen as merely participation.’ The primary goal of teacher professional learning is to promote changes in practices aiming to increase student achievement (Yoon et al. Citation2007; Bleicher Citation2014). Recent research by Margolis, Durbin, and Doring (Citation2017) addresses a growing need to attend to the way the teacher professional development is enacted in schools today. Research in teacher professional development rarely mentions students, yet the ‘student voice’ component is the most critical piece in making a learning situation authentic for an educator. They argue that student physical presence is the missing link in teacher professional development research (Margolis, Durbin, and Doring Citation2017). Research reviews conclude that teacher communities are most encouraging and effective when they focus on student learning or evidence of such learning (Bolam et al. Citation2005; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008).

There is no universal definition of a Professional Learning Community (PLC) (Stoll et al. Citation2006; Lomos, Hofman, and Bosker Citation2011a; Hairon et al. Citation2015). However, as a case in point described in literature, PLCs consist of teachers who, through a shared curriculum-focused vision, regularly collaborate towards continued improvement in meeting student needs. Teachers in these communities work for continuous development of their everyday work. ‘At its core, the concept of a PLC rests on the premise of improving student learning by improving teaching practice’ (Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008, 82). Well-developed PLCs have been shown to have positive impacts on both teaching practices and student achievements (Fishman et al. Citation2003; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008; Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2009; Darling-Hammond and McLaughlin Citation2011; Lomos, Hofman, and Bosker Citation2011b; Timperley Citation2011). However, Bausmith and Barry (Citation2011) state that much of the existing research related to PLCs focuses on improving, for example, school climate, and teacher and principal attitudes and perceptions of PLCs. Van Driel and Berry (Citation2012) share the concern of Bausmith and Barry (Citation2011) that teacher communities tend to ignore issues related to teaching subject matter. In addition, Vescio, Ross, and Adams (Citation2008) argue that PLCs must be able to describe their outcomes in terms of data indicating changes in teaching practices as well as improved student learning.

According to Hairon et al. (Citation2015), PLC is a multi-dimensional construct consisting of three interdependent aspects that form the theoretical framework for PLC research: the construct of PLCs, conditions and contexts of PLCs, and causalities of PLCs. Firstly, the complexity of the construct includes that there are no universal definitions of its three dimensions: Professional, Learning and Community. Moreover, the construct can be conceptualized within a school-level (organizational-level) or a group-level domain, which further adds to the complexity of the construct. Secondly, they point out that there are conditions (factors within school, e.g., school culture, resources) and contexts (factors outside school, e.g., national culture, societal factors) influencing a PLC. The third aspect of the construct concerns causalities, meaning PLCs’ effects on teacher knowledge, teaching practices and pupil learning outcomes. Hairon et al. (Citation2015) argue that research studies on PLCs need to invest more in testing whether they have a positive impact on student learning outcomes through improvement in teaching practices. Finally, they conclude that there is a need to establish methodological rigour in understanding the PLC construct, along with its attendant relationships with the conditions and contexts.

Methodological considerations

Participants

Two researchers and nine primary school teachers participated in this project. The teachers had more than five years of experience in teaching primary school pupils and all taught mathematics and science in grades 1 to 6 (7- to 12-year-olds) in the same school. However, most of the teachers lacked formal competence in science at the beginning of the project. When attending a continuing education course in science and technology (20 weeks in total during three semesters), three teachers expressed interest in starting a collaboration between the university and their primary school. The action research project was running partly in parallel with the continuing education course in science. The teachers presented the idea of the project to their colleagues. Further discussions with the teacher team and the school principal resulted in a project agreement (). The school principal supported this project by allowing the teachers to use the time intended for regular meetings, one afternoon every second week, also for the project realization. The principal did not participate in the project meetings.

In the project group we discussed that participants in action research are involved as active partners in an ongoing research process where a dialogue between researchers and teachers is needed to guarantee the free flow of information between them. The teachers can consult the researchers’ data and interpretations and the researchers have access to the teachers’ documentation (e.g. lesson plans and tests). Furthermore, we discussed that faithfulness to a mutually agreed-upon framework, governing the collection, use, interpretation and publication of data, is required and that participants are free to withdraw from the project at any time (cf. Zeichner and Noffke Citation2001; Kemmis Citation2009). During the project it was important to create an open and tolerant atmosphere between the researchers and teachers in order to increase the validity of the research outcomes.

Data collection

Data were collected during the last semester of the project using focus group interview (). The focus group is a collectivistic rather than an individualistic research method (Madriz Citation2000) and therefore used in the evaluation of this project. This method includes a small group of between six and ten people with similar backgrounds who are interviewed by a researcher/moderator for one to two hours (Patton Citation2002). Selected themes are discussed in a non-threatening environment and participants’ perceptions and ideas are explored. Group interactions are encouraged and utilized, and this is an important criterion as it distinguishes focus groups from the larger category of group interviews, which do not explicitly include participant interaction as an integral part of the research process. In a focus group interview the participants influence each other by responding to ideas and comments in the discussions (Patton Citation2002). Since the research field of professional development is moving towards the notion of professional learning (Timperley Citation2011; Bleicher Citation2014), data collection focused on the teachers’ experiences about the impact of the project on their learning and development of teaching practices in order to promote student achievement. In addition, it focused on factors influencing the project implementation. The aim of the interview was therefore to identify the teachers’ conceptions about four selected themes: factors influencing project implementation, project impact on teachers, its impact on teaching practices, and on pupil learning. An interview guide, in the form of these four themes, was sent in advance to the teachers. During the interview the teachers discussed the themes without substantial interference from the researchers in their discussion. The researchers interrupted the discussions only when, for example, an issue was highlighted by someone but unnoticed by others, to find out whether there was consensus or not within the group. The researchers audiotaped and transcribed the group discussion verbatim. During the next meeting the teachers were asked to verify the researchers’ interpretations and outcomes of the interview.

Data analysis

The data from the interview were first analysed by pattern coding (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). The first step of coding was a device for summarizing segments to the four selected themes: factors influencing project implementation, project impact on teachers, its impact on teaching practices, and on pupils’ learning. In the next step of coding similar segments of data concerning the four selected themes were grouped into qualitatively different sub-groups.

The researchers independently coded the transcriptions to establish the reliability of data analysis. The coding, with respect to the different sub-groups, was compared and discussed until consensus was reached. The researchers presented and discussed their interpretations and the outcomes of the data with the teacher team in order to establish their validity (McNiff Citation2002).

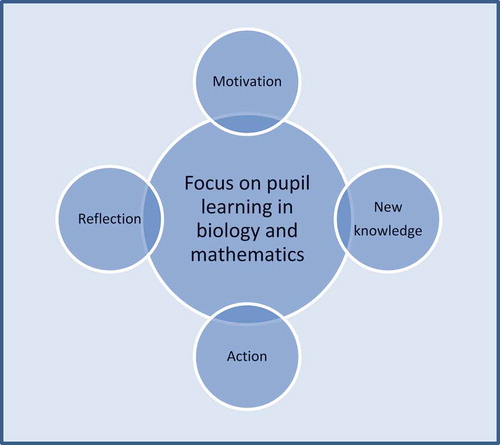

During the initial analysis process, we found that the factors the teachers highlighted as important for project implementation were those that stimulated their motivation. In the Collaboration Action Research model by Bleicher (Citation2014), motivation is the foundation of the professional learning change cycle. Therefore, we applied this model when we analysed and discussed the results in a meta-perspective. The model employs four central components (Bleicher Citation2014): (a) Motivation, which includes both teacher orientation in terms of disposition (the amalgam of ideas about teaching and learning, prior experience and personality traits) and self-efficacy to change teaching practice; (b) Knowledge, that refers to new Subject Matter Knowledge and Pedagogical Content Knowledge and resources in order to improve teaching practice; (c) Action, which relates to the teacher’s enactment of resources and new teaching strategies; and finally (d) Reflection. Reflection is a fundamental factor for sustainable change in practice. It is a mental activity that allows careful consideration of personal ideas and new knowledge.

Results

Motivating factors for project implementation

The teachers’ views of the factors influencing the project implementation are described as follows.

The relevance of the project and connection to the continuing education course

The teachers felt a strong engagement to participate in the project, and in their own learning, due to its high relevance to their practices. They considered that continuing education courses were often fragmentary and difficult to relate to practice. In this project, they experienced that the new knowledge could be applied directly to their teaching. The teachers who attended the continuing education course, as well as those who did not, experienced that the close connection between the course and the project was an important factor for the project implementation. The teachers’ new knowledge was applied directly in teaching practices, and their acquired experiences stimulated discussions that enriched the whole teacher team.

Louise: Yes, concerning teaching algebra and ecosystem sequences in grades one to six. … In this project we focused on our own practice, how to work with specific grades and lessons. … This is more than just ordinary education.

Anne: To me the course and the project have been an entirety.

Jenny: This project has been beyond expectations. … Continuing education courses are usually fragmentary. It feels like this was more an entirety. … We have worked systematically with these subject areas.

Jenny: We participated in a continuing education course and could directly connect it to this project.

Louise: Yes, it must have been very good for you. [Louise did not participate in the course]. I have seen your enthusiasm during the course. A lot of new knowledge has come out of it. We have had good discussions and picked up a huge amount of teaching material together. So it has been incredibly positive to learn together.

Researchers/mentors

According to the teachers, the mentors from the university played an important role in the project by supporting and helping teachers to discern various aspects of Subject Matter Knowledge and Pedagogical Content Knowledge, and by leading the project forward.

Anne: It has been incredibly useful to discuss lessons and learn more about the subjects.

Inger: It was important that we could put questions and discuss, for example, Content Representation with mentors.

Louise: Yes, we had sessions [with mentors] in science and mathematics about the subject-specific concepts and the connections between them. We have also discussed critical aspects of these objects of learning.

Jenny: You must have someone who leads the project and has good subject matter knowledge. … We would not have reached as far without the help of mentors.

Planning tools

The teachers experienced that the planning tool Content Representation was difficult to use at the beginning, but during the project they found it useful as a scaffolding framework, helping them to structure their collaborative work.

Jenny: Content Representation was hard to use in the beginning. It took some time to get used to it. We got lost in the beginning.

Inger: It felt very strange. What is this? What are we going to do with this?

Anne: Yes, in the beginning it was difficult to complete the document. It felt not so easy.

Louise: But when we repeated the process, it became so much easier.

Jenny: The aim of the tool [Content Representation] was to stimulate collaborative learning. When we used this tool together our work became structured, and we needed that!

When using Content Representation as a planning tool, important subject aspects were highlighted and this helped the teachers to construct relevant tests. The conscious use of pre- and post-tests was important for revealing pupils’ knowledge and learning.

Louise: With this tool [Content Representation] it becomes clearer which concepts I want to highlight in my teaching. I reflect on what the most important aspects are before conducting lessons and before doing the pre-tests.

Jenny: We really liked the use of the pre- and post-tests. We have started to consciously use them in other subjects as well. The pupils get a clear picture of what they know and what they have learned. And it’s very interesting also for teachers to see how they think, for example in grade one – What is a plant? – and to hear their reasoning. Based on this you can design your lessons.

Time for collaborative process

The teachers found that the change in way of working was a collaborative process over time:

Jenny: It [the way of working] was difficult at the beginning but it was a process.

Rita: Yes, it was hard before we got started but then …

Inger: It was important that we worked together so that we could support each other. If I had worked myself or if we had been just two, then it would have been easy to give up. I would have thought – this is nothing for me.

The school principal supported this collaborative process by allowing the teachers to use the time intended for regular meetings, one afternoon every second week, for the project realization as well.

Relation between teacher learning and teaching practice

Increased Subject Matter Knowledge and self-efficacy in teaching

The teachers stated that the change in their teaching practice was partly a result of their improved Subject Matter Knowledge, which increased their self-efficacy.

Anne: Many of us who did not have sufficient subject matter knowledge have learnt a lot. Now we feel much more confident with the pupils.

Inger: Yes, we now have increased self-efficacy, more ideas and we see more possibilities in our work. I can explain photosynthesis in different ways. It gives self-efficacy and the atmosphere during the lessons becomes more open.

Anne: This means that it is now easier to engage pupils.

Inger: Yes, and also the quality of the discussions with the pupils is enhanced when teachers themselves have more subject matter knowledge.

Jenny: Yes, this stimulates teachers to deepen their discussions with pupils.

Systematic work with and increased knowledge of key concepts in both biology and mathematics

By using Content Representation and by working systematically, the teachers increased their knowledge and awareness of key concepts.

Louise: By using this planning tool [Content Representation] my ideas about the important concepts become clearer. What aspects are important for me? You will reflect on which concepts pupils are supposed to learn both in mathematics and natural sciences? When you have decided which core concepts are in focus you can make diagnostic pre-tests concerning, for example, the equality sign, or plants or photosynthesis.

Jenny: We have worked thoroughly with these content areas.

Louise: Yes, both in algebra and ecosystems. We have worked systematically with these content areas from grade 1 to 6. … We have previously not worked in this way.

Jenny: We have extended our knowledge, for example about pre-algebra.

Increased knowledge of and focus on pupil pre-knowledge and learning

By using the tests, pupils’ knowledge and learning outcomes became more visible. The teachers became aware of and engaged in all pupils’ learning, and more careful in teaching of key concepts.

Louise: By using pre-tests it is possible to see changes in pupils’ learning and now we have done more pre-tests than before.

Jenny: Yes, and this means that we now are more engaged in all pupils’ learning. We want that pupils are more involved in discussions.

Inger: Yes, and by using pre-and post-tests pupil learning outcomes become visible.

Jenny: The tests also reveal which learning goals are still not achieved.

Louise: It means that we now concentrate more carefully on some concepts that we previously taught superficially.

Increased knowledge of collaboration – model for professional learning

The increased collaboration changed the teachers’ practices. This way of working provided them with a model for future professional learning.

Rita: We now have more collaboration.

Louise: We thought we already had an open and trustful atmosphere, but now it has improved. We are now much more open to each other.

Anne: Now it is much easier to put questions when we are working together.

Jenny: And now we have got a model for how to work in the future. Now we can more easily continue with our collaborative way of working.

Pupil learning

Increased awareness and learning

The project increased pupil motivation and learning in both subjects.

Jenny: My opinion is that the pupils now find the lessons more fun. For example, the pupils have become more interested in number patterns. The same goes for biology. The pupils have learnt much.

Louise: And I think that they have become much more aware about what is needed in order to build up understanding.

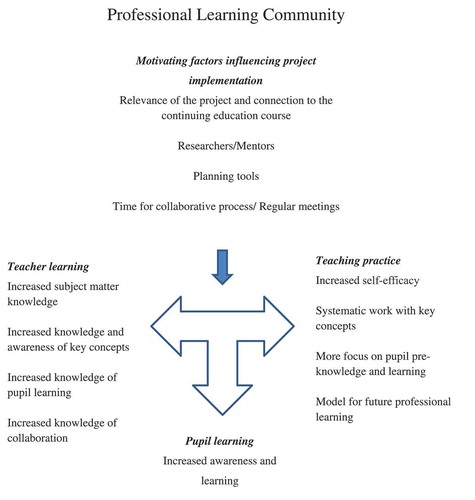

The project evaluation is summarized in . It shows that several factors motivated the teachers to engage in the project. In addition, it indicates the causality between teacher learning, their practices and pupil learning in the Professional Learning Community.

Discussion

The research results are based on the interpretation of the empirical data we received through the teachers’ voices. To avoid that we, as researchers, over-interpreted data we presented and discussed our interpretations of the outcomes with the teachers. This was done in order to minimize the possible impacts of a power imbalance between the researchers and teachers.

The evaluation of the project shows that the conscious use of Content Representation and pre- and post-tests in the project gave teachers opportunities to reflect together on their practices, professional learning and student learning. The teachers perceived that through this project they increased their focus on pupil learning and their own knowledge and learning, and worked for continuous development of their teaching practices. The teachers’ conceptions about the factors influencing the implementation of the action research project were also made visible. These factors motivated the teachers in their learning process and they can be seen as a cornerstone to the positive changes in their practices. Our results are in line with Bleicher (Citation2014), who states that motivation is fundamental to the success of an entire professional learning change cycle. The teachers experienced that during the project and the continuing education course they gained Subject Matter Knowledge and new teaching ideas that were shared and discussed during their regular meetings and implemented directly in their classrooms. As shown in this study, and by earlier research, teachers need support in the form of time for regular meetings to bolster self-efficacy (Bleicher Citation2014). Many professional learning efforts are developed by outside authorities (Henderson, Finkelstein, and Beach Citation2010) and do not directly address the daily realities of teaching in specific settings (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2009; Bausmith and Barry Citation2011; Van Driel and Berry Citation2012). In this project the teachers chose the subject areas that were difficult to teach and difficult for pupils to learn. These areas were linked to the teachers’ general concerns and needs in their teaching practices (Kellner and Attorps Citation2015). The teachers expressed in the interview that by using Content Representation their perceptions about teaching and learning the specific topics were made visible; for example, their ideas about the important concepts became clearer. The importance of recognizing teacher epistemological and pedagogical conceptions and dispositions is highlighted by Bleicher (Citation2014). Although the teachers found Content Representation hard to complete and they needed support at the beginning, they expressed that this obstacle was overcome during the project. Furthermore, they stated that Content Representation and pre- and post-tests were relevant tools because they helped and motivated them to follow and reflect on how the changes in their instruction influenced pupil learning. Our results correspond with Bleicher’s (Citation2014), who argues that to effect changes in practices, teachers must be able to perceive positive gains in student outcomes within a reasonably short time after the lessons are conducted.

The teachers’ view was that the presence of mentors from the university and the use of planning tools encouraged them to develop their Subject Matter Knowledge and discern various aspects of Pedagogical Content Knowledge and thereby increased their self-efficacy. Bleicher (Citation2014) states that the single most important professional learning outcome is to feel empowered to be able to change teaching practice, building on a new knowledge base. Kind (Citation2009) also points out that when teachers’ Subject Matter Knowledge is undeveloped, they have a tendency to choose more passive instructional strategies and show less understanding of their students’ learning difficulties. Since Content Representation is based on the theoretical framework of teacher knowledge with the main focus on Subject Matter Knowledge and Pedagogical Content Knowledge (Loughran, Mulhall, and Berry Citation2004), and learning study is grounded on the learning theory called variation theory (Marton and Pang Citation2006; Pang and Ling Citation2012), the tools helped the teachers to see their Subject Matter Knowledge, their practices and pupils’ learning anew. The teachers expressed that these tools helped them to problematize the object of learning in their teaching contexts; they increased their knowledge about key concepts and how to work collaboratively and systematically on improving teaching and learning. Thereby, the tools helped them to reflect on the links between teaching and pupil learning. Through them the teachers felt enabled to change their teaching practices; they gained self-efficacy and a reflection model for future professional learning. Altogether, these results indicate a causality between teacher knowledge, teaching practices and pupil learning.

Our interpretation of the PLC notion rests on the premise presented by Vescio, Ross, and Adams (Citation2008), i.e. improving student learning by improving teaching. In this sense our research project created a PLC (cf. Fishman et al. Citation2003; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008; Bausmith and Barry Citation2011; Darling-Hammond and McLaughlin Citation2011; Timperley Citation2011; Van Driel and Berry Citation2012). Recent research indicates that the role of facilitators is central for developing effective PLCs (Becuwe et al. Citation2016; Margalef and Pareja Roblin Citation2016; Voogt, Pieters, and Handelzalts Citation2016). In this project the mentors from the university were facilitators that coordinated group work, supported community building and enabled teacher learning and reflective professional inquiry.

As there is no universal definition of the PLC (Hairon et al. Citation2015), there is a need to describe the construct of the PLC used in this specific action research project. The first of the three interdependent aspects of PLCs is the construct of the Professional Learning Community. We conceptualized Professional Learning (PL) in the PLC construct in accordance with Bleicher (Citation2014) through collaborative action research in terms of motivation, (new) knowledge, action and reflection (). A fundamental shift in thinking, when moving from professional development to professional learning, is that the latter requires teachers to be seriously engaged and motivated in their own learning and that students are at the centre of the process (Yoon et al. Citation2007; Timperley Citation2011; Bleicher Citation2014; cf. ). Through the systematic inquiry of their practices, the teachers reflected on their own new knowledge and learning, and how effective the new teaching strategies were in terms of improved pupil learning ( and ). Such action was critical to the teachers’ professional learning. In earlier research, it is pointed out that student physical presence is the missing link in teacher professional development (Margolis, Durbin, and Doring Citation2017). In this project, improvements in pupil learning were not regarded as a by-product but rather its central aim (; Kellner and Attorps Citation2015; Attorps and Kellner Citation2017).

Figure 3. Teacher professional learning in the professional learning community, through action research.

Moreover, the Community construct in PLC was conceptualized within a group-level domain in which nine teachers and two researchers were collaborating. The second aspect of PLCs concerns conditions and contexts. We found that there were conditions and contexts influencing the PLC; the motivating factors for implementation of the project () could be differentiated at two levels (cf. Hairon et al. Citation2015), within-school conditions (relevance of the project and regular meetings) and outside-school context (researchers/mentors, planning tools and connection to the continuing education course). The third aspect of the PLC construct has to do with causalities (Hairon et al. Citation2015). Our overall project results suggest positive causalities of the PLC on teacher professional learning, instructional practices and pupil learning outcomes (; Kellner and Attorps Citation2015; Attorps and Kellner Citation2017).

Our results can also be discussed in relation to recent research on teachers’ work identity and self-reported mental health (Nordhall, Knez, and Saboonchi Citation2018). Work identity is connected to the question ‘Who am I?’ at work; how we, in a working context, define ourselves in terms of individual and social attributes (Turner et al. Citation1987; Causer and Jones Citation1996; Cappelli Citation2000). Work identity occurs at different levels of abstraction including the individual level (involves I descriptions) that refers to personal work-related associations (My profession as a teacher), and the social level (involves We descriptions) that relates to collective work-related associations (We – working in the teacher team) (see Knez Citation2014, Citation2016; Nordhall, Knez, and Saboonchi Citation2018). Personal work identity associates with personal self-related behaviours while collective work identity associates with collective behaviours. Both of them associate with motivations, attitudes, interests and cognitions (Ybarra and Trafimow Citation1998; Johnson, Selenta, and Lord Citation2006). Both personal and collective work identity include emotion and cognition components. Recent research shows the significant role of the emotion and cognition components of both personal and collective work identity for self-reported general mental health and exhaustion among 768 Swedish teachers (Nordhall, Knez, and Saboonchi Citation2018). Personal work identity was measured by a questionnaire including emotion statements (e.g. ‘I know my work very well’; ‘I am proud of my work’) and cognitive statements (e.g. ‘I can reflect on the memories of my work’; ‘I can travel back and forth in time mentally to my work when I think about it’).The collective work identity was measured by including emotion statements (e.g. ‘When someone criticizes my organization, it feels like a personal insult’; ‘When someone praises the organization it feels like a personal compliment’) and cognitive components (‘I am very interested in what others think about the organization’; ‘When I talk about this organization, I usually say “we” rather than “they”’; ‘This organization’s successes are my successes’). It was found that when teachers felt more (emotion statements) and thought less (cognitive statements) with reference to their personal work identity, they felt mentally better and were less exhausted. In contrast, when teachers thought more and felt less with reference to their collective work identity, they felt mentally better and less exhausted. Their conclusion was to design intervention studies to, for example, promote the advantage of stronger feeling in teachers’ personal work identity and to promote the advantage of stronger thinking in their collective work identity. In our study we found that factors which increased teacher motivation were essential for project implementation and in the light of Nordhall, Knez, and Saboonchi (Citation2018), the results indicate that these factors had impacts both on teachers’ individual and collective work identity. Through the continuing education course and the collaboration with two mentors from the university, teachers gained subject knowledge that increased their self-efficacy in teaching; i.e. it seemed to strengthen the individual/emotional level of their work identity. Furthermore, our results indicate that through the cooperation between the school and university (the mentors, the pedagogical planning tools, and the principal’s support with time for project meetings) the teachers’ collective work identity on a cognitive level was reinforced when they gained a model combining practice and theory for collaboration in the teacher team.

Conclusion

There were several motivating factors crucial for project implementation and for professional learning to occur in this specific PLC; the relevance of the project and connection to the continuing education course, mentors from university, planning tools and time for collaboration. The teachers’ new knowledge, gained through the continuing education course in combination with the action research project, could at once be implemented in their practices and the effects on pupil learning achievements were directly observed. Based on our findings, the intersection between universities and schools as a professional learning arena may have underutilized potential for creating PLCs. We also suggest more research concerning the processes in PLCs related to components of teacher work identities and health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eva Kellner

Eva Kellner has a PhD in plant physiology and is a university lecturer in biology at the University of Gävle, Sweden. She has long experience in teaching biology in teacher education and her current research focus is teacher professional learning in biology.

Iiris Attorps

Iiris Attorps is a university lecturer and professor in mathematics education at the University of Gävle, Sweden. She has long experience in teaching of mathematics for prospective teachers and engineers. Her research interest is teaching and learning of mathematics in compulsory school as well as on university level.

References

- Abell, S. K. 2008. “Twenty Years Later: Does Pedagogical Content Knowledge Remain a Useful Idea?” International Journal of Science Education 30 (10): 1405–1416. doi:10.1080/09500690802187041.

- Attorps, I., and E. Kellner. 2017. “School–University Action Research: Impacts on Teaching Practices and Pupil Learning.” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 15 (2): 313–330. doi:10.1007/s10763-015-9686-6.

- Avalos, B. 2011. “Teacher Professional Development in Teaching and Teacher Education over Ten Years.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007.

- Ball, D. L., M. H. Thames, and G. Phelps. 2008. “Content Knowledge for Teaching: What Makes It Special?” Journal of Teacher Education 59 (5): 389–407. doi:10.1177/0022487108324554.

- Bausmith, J. M., and C. Barry. 2011. “Revisiting Professional Learning Communities to Increase College Readiness: The Importance of Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Educational Researcher 40 (4): 175–178. doi:10.3102/0013189X11409927.

- Becuwe, H., J. Tondeur, N. Pareja Roblin, J. Thys, and E. Castelein. 2016. “Teacher Design Teams as a Strategy for Professional Development: The Role of the Facilitator.” Educational Research and Evaluation 22 (3–4): 141–154. doi:10.1080/13803611.2016.1247724.

- Bertram, A., and J. Loughran. 2012. “Science Teachers’ Views on CoRes and PaP-eRs as a Framework for Articulating and Developing Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Research in Science Education 42 (6): 1027–1047. doi:10.1007/s11165-011-9227-4.

- Bleicher, R. E. 2014. “A Collaborative Action Research Approach to Professional Learning.” Professional Development in Education 40 (5): 802–821. doi:10.1080/19415257.2013.842183.

- Bolam, R., A. McMahon, L. Stoll, S. Thomas, M. Wallace, A. Greenwood, K. Hawkey, M. Ingram, A. Atkinson, and M. Smith. 2005. Creating and Sustaining Effective Learning Communities. Research Brief No. RB637. London: Department for Education and Skills.

- Borko, H., J. Jacobs, and K. Koellner. 2010. “Contemporary Approaches to Teacher Professional Development.” In Third International Encyclopedia of Education, edited by P. L. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw, 548–556. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Cappelli, P. 2000. “Managing without Commitment.” Organizational Dynamics 28 (4): 11–24. doi:10.1016/S0090-2616(00)00008-5.

- Causer, G., and C. Jones. 1996. “Management and the Control of Technical Labour.” Work, Employment and Society 10 (1): 105–123. doi:10.1177/0950017096101005.

- Darling-Hammond, L., R. Chung Wei, A. Andree, N. Richardson, and S. Orphanos. 2009. Professional Learning in the Learning Profession: A Status Report on Teacher Development in the U.S. and Abroad. Stanford, CA: National Staff Development Council.

- Darling-Hammond, L., and M. W. McLaughlin. 2011. “Policies that Support Professional Development in an Era of Reform; Policies Must Keep Pace with New Ideas about What, When, and How Teachers Learn and Must Focus on Developing Schools’ and Teachers’ Capacities to Be Responsible for Student Learning.” Phi Delta Kappan 92 (6): 81–90. doi:10.1177/003172171109200622.

- Fishman, B. J., R. W. Marx, S. Best, and R. T. Tal. 2003. “Linking Teacher and Student Learning to Improve Professional Development in Systemic Reform.” Teaching and Teacher Education 19 (16): 643–658. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(03)00059-3.

- Hairon, S., J. W. P. Goh, C. S. K. Chua, and L. Y. Wang. 2015. “A Research Agenda for Professional Learning Communities: Moving Forward.” Professional Development in Education 43 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/19415257.2015.1055861.

- Henderson, C., N. Finkelstein, and A. Beach. 2010. “Beyond Dissemination in College Science Teaching: An Introduction to Four Core Change Strategies.” Journal of College Science Teaching 39 (5): 18–25.

- Johnson, R. E., C. Selenta, and R. G. Lord. 2006. “When Organizational Justice and the Self-Concept Meet: Consequences for the Organization and Its Members.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 99 (2): 175–201. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.07.005.

- Kellner, E., and I. Attorps. 2015. “Primary School Teachers’ Concerns and Needs in Biology and Mathematics Teaching.” Nordic Studies in Science Education 13 (3): 282–292. doi:10.5617/nordina.964.

- Kemmis, S. 2009. “Action Research as a Practice-Based Practice.” Educational Action Research 17 (4): 463–474. doi:10.1080/09650790903093284.

- Kind, V. 2009. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education: Perspectives and Potential for Progress.” Studies in Science Education 45 (2): 169–204. doi:10.1080/03057260903142285.

- Knez, I. 2014. “Place and the Self: An Autobiographical Memory Synthesis.” Philosophical Psychology 27 (2): 164–192. doi:10.1080/09515089.2012.728124.

- Knez, I. 2016. “Toward A Model of Work-Related Self: A Narrative Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 7, article 331: 1–14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00331.

- Little, J. W. 2006. Professional Community and Professional Development in the Learning-Centered School. Arlington, VA: National Education Association. Accessed 1 April 2019. http://beta.nea.org/assets/docs/HE/mf_pdreport.pdf.

- Lomos, C., R. H. Hofman, and R. J. Bosker. 2011a. “Professional Communities and Student Achievement – A Meta-Analysis.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 22 (2): 121–148. doi:10.1080/09243453.2010.550467.

- Lomos, C., R. H. Hofman, and R. J. Bosker. 2011b. “The Relationship between Departments as Professional Communities and Student Achievement in Secondary Schools.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (4): 722–731. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.003.

- Loughran, J. J., A. Berry, and P. Mulhall. 2012. Understanding and Developing Science Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Loughran, J. J., P. Mulhall, and A. Berry. 2004. “In Search of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science: Developing Ways of Articulating and Documenting Professional Practice.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 41 (4): 370–391. doi:10.1002/tea.20007.

- Madriz, P. 2000. “Focus Groups in Feminist Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 835–850. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Magnusson, S., J. Krajcik, and H. Borko. 1999. “Nature, Sources, and Development of Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Science Teaching.” In Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge: The Construct and Its Implications for Science Education, edited by J. Gess-Newsome and N. G. Lederman, 95–132. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Margalef, L., and N. Pareja Roblin. 2016. “Unpacking the Roles of the Facilitator in Higher Education Professional Learning Communities.” Educational Research and Evaluation 22 (3–4): 155–172. doi:10.1080/13803611.2016.1247722.

- Margolis, J., R. Durbin, and A. Doring. 2017. “The Missing Link in Teacher Professional Development: Student Presence.” Professional Development in Education 43 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1080/19415257.2016.1146995.

- Marks, R. 1990. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge: From a Mathematical Case to a Modified Conception.” Journal of Teacher Education 41 (3): 3–11. doi:10.1177/002248719004100302.

- Marton, F., and M. P. Pang. 2006. “On Some Necessary Conditions of Learning.” The Journal of the Learning Science 15 (2): 193–220. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls1502_2.

- McNiff, J. 2002. Action Research: Principles & Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Miles, B., and A. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nordhall, O., I. Knez, and F. Saboonchi. 2018. “Predicting General Mental Health and Exhaustion: The Role of Emotion and Cognition Components of Personal and Collective Work-Identity.” Heliyon 4 (8): e00735. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00735.

- Pang, M. F., and L. M. Ling. 2012. “Learning Study: Helping Teachers to Use Theory, Develop Professionally, and Produce New Knowledge to Be Shared.” Instructional Science 40 (3): 589–606. doi:10.1007/s11251-011-9191-4.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sagor, R. D. 2010. The Action Research Guidebook: A Four-Stage Process for Educators and School Teams. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Shulman, L. S. 1986. “Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching.” Educational Researcher 15 (2): 4–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004.

- Shulman, L. S. 1987. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundation of the New Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 57 (1): 1–22. doi:10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411.

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7 (4): 221–258. doi:10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Timperley, H. 2011. Realizing the Power of Professional Learning. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Turner, J. C., M. A. Hogg, P. J. Oakes, S. D. Reicher, and M. S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Van Driel, J. H., and A. Berry. 2012. “Teacher Professional Development Focusing on Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Educational Researcher 41 (1): 26–28. doi:10.3102/0013189X11431010.

- Vescio, V., D. Ross, and A. Adams. 2008. “A Review of Research on the Impact of Professional Learning Communities on Teaching Practice And Student Learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (1): 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004.

- Voogt, J. M., J. M. Pieters, and A. Handelzalts. 2016. “Teacher Collaboration in Curriculum Design Teams: Effects, Mechanisms, and Conditions.” Educational Research and Evaluation 22 (3–4): 121–140. doi:10.1080/13803611.2016.1247725.

- Ybarra, O., and D. Trafimow. 1998. “How Priming the Private Self or Collective Self Affects the Relative Weights of Attitudes and Subjective Norms.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 24 (4): 362–370. doi:10.1177/0146167298244003.

- Yoon, K. S., T. Duncan, S. W.-Y. Lee, B. Scarloos, and K. Shapley. 2007. Reviewing the Evidence on How Teacher Professional Development Affects Student Achievement. Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007-No.033. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education.

- Zeichner, K. M., and S. E. Noffke. 2001. “Practitioner Research.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching, edited by V. Richardson, 298–330. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.