ABSTRACT

This paper describes an innovative bilingual education program developed and implemented in 208 primary classes in Senegal from 2009 to 2018 by a Senegalese NGO working with the national Ministry of Education to address issues of quality in primary education. L’approche simultanée or simultaneous approach, also known as bilinguisme en temps réel or real-time bilingualism, developed organically through a consultative process between NGO development actors, university linguists and educators. Unlike the early-exit transitional bilingual programs previously piloted in Senegal that are common throughout West Africa, this program taught literacy, mathematics and the sciences in both a national language (Wolof or Pulaar) and French from the first year of primary school. Using data collected for an external evaluation conducted in 2018, along with follow-up research conducted in 2019 with designers and implementers of the simultaneous approach, this paper analyzes the effectiveness of the program and its implications for Senegal, where the Ministry of Education appears close to adopting a national language-in-education policy. There are also implications for the field of L1-based multilingual education, as ARED’s simultaneous approach provides a refreshing new perspective on teaching and learning non-dominant and dominant languages.

Introduction

Senegal is a multilingual country on a multilingual continent. Like many countries in the region, Senegal’s French colonial heritage has strongly influenced its language policies in government, education and society (Diallo Citation2010, Citation2011). Since Independence in 1960, formal education has been officially conducted in French, despite the fact that virtually all Senegalese people speak one or more home languages (L1s) from the Atlantic-Congo or Mande language families (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2019). Six languages – Wolof, Pulaar, Seereer, Soninke, Mandinka and Diola – were granted the status of langues nationales (national languages) in the Constitution of 2001 based on criteria related to corpus development and official authorization of their orthographies. They have since been joined by eight more, according to Fary Ka, President of the Senegalese Academy of Languages (personal communication, January 2019), bringing the number of decreed national languages to 14; an additional 11 languages have been codified and are in various stages of seeking authorization (see also Diagne Citation2017). All of these languages and some others have been used in a range of educational programs including adult literacy and bilingual primary and pre-primary school experimentation (DPLN Citation2002).

Wolof has an unofficial but widely acknowledged status as a Senegalese lingua franca, with over 5 million L1 and L2Footnote1 speakers in Senegal alone (as of 2015, per Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2019). This has widely acknowledged practical advantages for countrywide communication, but some have expressed concern that ‘wolofization’ may cause language displacement or shift (Faty Citation2015; Sarr Citation2020). Pulaar is the next most widely spoken language, by an estimated 3.5 million in Senegal and millions more across West Africa in a range of varieties (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2019). Despite the strength of the community in Senegal, Pulaar speakers are among the most vocal critics of wolofization, and have engaged in concrete activities to counteract language shift (Faty Citation2015), but they are not alone. Sarr (Citation2020) wisely advises stakeholders to acknowledge and address these tensions in light of increased usage of national languages in formal education and recent policy-related discussions. There is a risk that the still-limited space and resources allocated to national languages may cause stakeholders to raise defenses rather than to pool resources and collaborate to open up educational policy spaces – and wedge them open (per Hornberger Citation2002) – at this potentially critical juncture in educational decision-making.

Historically, as the seat of French colonial rule in West Africa, Senegal had the most developed education system in the region (Blakemore Citation1970, in Sarr Citation2020). While its current level of educational development is relatively high compared with its neighbors, with a primary net enrollment of over 74% in 2017 (UIS Citation2019), its continued dependence on French as language of instruction has severely constrained educational quality. French is spoken as L1 by less than 1% of the population (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2019). Despite strong government investment in education, which amounted to over 21% of GDP in 2017, educational wastage is high in terms of dropout, failure and repetition during the six years of primary schooling. There is currently a 60% survival rate of students enrolled, and enrollees represent less than half of the school-aged population (UIS Citation2019). It is not difficult to see how the mismatch between the European French-based linguistic and cultural orientation of the school and the multilingual, multicultural orientation of the home contributes to this wastage. Dependence on exogenous languages of instruction throughout the continent has caused the systematic devaluing of Indigenous knowledges and identities, alienation from social institutions and overall lack of access to formal education or even functional basic literacy, as pointed out by Alidou (Citation2009, Citation2010) and many others (as reviewed in Sarr Citation2013).

The mismatch between school and home languages has not gone unnoticed, and Senegal has a long history of experimentation to bring people’s home languages, or at least the designated national languages, into basic and continuing education alongside French. The latest and most influential program to date was implemented from 2009 to 2018 by the Senegalese NGO known as ARED, or Association in Research and Education for Development, in collaboration with the National Ministry of Education (MEN). The purpose of this paper is to describe and analyze the results of ARED’s innovative, home-grown ‘simultaneous’ bilingual approach and the context-integrated strategies used to implement it, in light of current efforts to change the educational language policy in Senegal from a monolingual French system to a multilingual system based on Senegalese national languages. The paper draws on data collected by our field team for Miske Witt and Associates International (MWAI) in late 2018 and early 2019Footnote2 as part of an external evaluation of ARED's program conducted for the donor, Dubai Cares. This is supplemented by independent research conducted with key actors in mid-2019.Footnote3 The results and discussion have policy implications for the national education system in Senegal, where the Ministry of Education seems to be considering a change in favor of national languages. There are also implications for the field of L1-based multilingual education, as ARED’s simultaneous approach provides a refreshing new perspective on teaching and learning non-dominant and dominant languages.

Senegal’s long experience with bilingual education

Senegalese linguists, educators and other stakeholders have worked for years to address the linguistic and cultural deficits of French-medium schooling, while remaining conscious of the fact that the public will not accept a form of education that jeopardizes the learning of French. The argument has been made strongly that the learning of French can be facilitated by a bilingual approach starting with children’s home languages, and both small – and medium-scale programs have been conducted to demonstrate this. These include national efforts such as the televised and radio broadcasted classes to support instruction in national languages in primary schools (1977–1984), during which many current actors became convinced of their importance for education and empowerment, but which failed to end in policy change, despite the fact that the then-newly-formed National Commission for the Reform of Education and Training recommended the introduction of national languages as a medium of instruction in lower primary (Maurer Citation2011). According to MEN (Citation2019), there were two symposia (in Kolda in 1993 and Saint-Louis in 1995) that called for the national languages to be introduced in basic education, leading to two experiments by the State. In the first, from 2002 to 2008, simply known as Mise à l’essai (MAE) or ‘Put to the Test,’ the six national languages were taught alongside French using a transitional bilingual model in a total of 465 experimental classes. This experiment faced implementational challenges but resulted in relatively better scores for bilingually educated learners on the primary school leaving examination known as the CFEE or Certificat de fin d’étude élémentaire (MEN Citation2019; ARED Citation2018). The second wave of experimentation began in 2013 as part of an eight – (now twelve-) country project supported by OIF (L'Organisation internationale de la francophonie) known as École et langues nationales (ELAN), or School and National Languages. ELAN Senegal worked in all six national languages in 60 CI-CE1 classes (grades 1–3), consciously working on literacy transfer from L1 to French and producing textbooks in language(s), mathematics and the sciences (OIF Citationn/d; MEN Citation2019). An external evaluation based on a Wolof-speaking sample of learners found that good literacy progress was made in the first year but stagnated in the second (Nocus, Guimard, and Florin Citation2016, 16), which would suggest (per Cummins Citation2009) that assessment in French was premature and a stronger foundation should be built in the L1 (see also Thomas and Collier Citation1997, Citation2002). The program reportedly suffered from poor integration with MEN, leading to delays of six months or more to get teaching and learning materials to the schools, and low levels of support to teachers, communities and education staff (Juillard Citation2017). However, in schools with adequate implementation, student performance has been significantly improved, and ELAN has since 2018 expanded its work to classroom assessment and teacher training (MEN Citation2019).

There have also been NGO-backed efforts to use national languages in school programs, including ECE, ADLAS and EMiLe, all with donor assistance. The rural Community Elementary Schools (ECE), created by the Fondation Education et Santé or Education and Health Foundation, functioned from 2002 to 2012 and used the six national languages in MAE’s transitional bilingual model, adding curricular elements like gardening; its reported successes were in training and supporting teachers as well as the performance of graduates on national examinations (MEN Citation2019). In 2011 ADLAS (Society for the Development of the Saafi Language) began running a Saafi-Saaafi/French bilingual program in ten test classes, also using MAE’s transitional model in a seventh national language. Building on its preschool experiences since 2008 and developing a participatory and inclusive approach, ADLAS has enjoyed strong community support, and district inspectorates have reported relatively better school results for bilingually educated learners as assessed in French, but the experiment has been challenged by lack of external support since 2014 (MEN Citation2019). Finally, the Projet d’Education Multilingue or Multilingual Education Project (EMiLe) of World Vision, the National Office of Catholic Education (ONECS) and SIL International introduced a late-exit transitional bilingual program in Sereer/French in 12 pilot classes in 2013, where the final two years of primary (CM1-CM2, grades 5–6) are characterized by 40% use of the L1 and 60% use of French. Parents are reportedly unanimous in their support, seeing effective transfer of literacy from Sereer to French and superior school performance of their children in relation to those learning only in French (MEN Citation2019).

The focus of this paper is on the most recent and innovative of the NGO-supported bilingual experiences, ARED’s ‘Support Program for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal,’ which was implemented from 2009 to 2018. ARED, a Senegalese NGO working in adult literacy and education for pastoral communities (Dia Citation2016), had approached National Ministry of Education (MEN) officials in 2008 to explore how their long experience in national language literacy could be applied to formal education. The original project, funded by the Hewlett Foundation, began as an after-school intervention during the 2009–2010 school year, but was successfully integrated into public classrooms the year after, where bilingual classes soon outperformed traditional ones (Dalberg Citation2014). The next round of financing came from Dubai Cares, allowing ARED to scale up the model to 98 schools and 101 classes in three regions of Senegal from 2014 to 2018. Most of the data discussed in this paper come from the external evaluation our team conducted at the end of the funding cycle (MWAI Citation2019).

Part of ARED’s expressed mission is to work within formal MEN structures to influence evidence-based policymaking, and implementation of this program is meant to provide conclusive evidence of how bilingual education addresses the needs of Senegalese learners. MEN has issued statements of intent in 2001, 2015 and 2018 to bring national languages into the formal education system (MEN Citation2019), and the same intent is identified as one of eight priorities in the Education Sector Quality, Equity and Transparency Enhancement Program (PAQUET) 2013–2025 (MEN Citation2013). At the time of this writing, however, there has been no official decision to implement bilingual education system-wide. Meanwhile, calls for généralisation of a bilingual approach from diverse levels of society have grown louder. These calls are increasingly linked to complaints that bilingual education should not be relegated to experiments and pilot programs, making it subject to inconsistencies in funding and technical support. The presentation of the results of our external evaluation (MWAI Citation2019) received widespread attention in April 2019, and was part of a series of recent steps taken to move the agenda forward.

ARED’s ‘simultaneous’ bilingual model and its implementation

ARED (Citation2014) refers to its model as ‘bilingualism in real time’ due to the simultaneous teaching of literacy and other curricular content in both a national language (ideally but not always the learner’s L1) and French (known as the L2 here because it is a new language for virtually all learners). I would call the approach ‘simultaneous biliteracy’ because one of its most salient features is the teaching of initial literacy in both L1 and L2 from the first day of school.

Practically speaking, what simultaneous biliteracy means for instruction is that in the early years, a literacy lesson will focus on a phoneme that is common to both L1 and L2. The first 30 min of the lesson will teach that phoneme in Wolof or Pulaar, say the sound and letter A, using keywords and sentences in context. The next 30 min will teach the same phoneme in French using French keywords in the same context. As teachers, trainers and model designers all explained to us, for phonemes shared between the languages, only part of that second 30-minute period is needed to consolidate the phoneme in French, representing a ‘gain de temps’ or time saved that can be spent working on new vocabulary or reinforcement activities.

The teaching of the other two major areas of the curriculum, mathematics and ESVS (Éducation à la science et à la vie sociale), representing natural and social sciences, is also done in a split-lesson format, and the same time gain was reported by stakeholders. For example, a lesson on photosynthesis taught in the L1 does not need to be repeated in French; instead, content already taught can be reviewed and consolidated using French vocabulary. Model designers and trainers developed the concept of niveau d’ancrage to help teachers plan lessons based on the level at which the concepts can be ‘anchored’ based on transfer of knowledge learned in the L1 to expression to expression of that knowledge in French.

The ARED model was designed to follow the national curriculum and timetable, where each of the subject areas was split between L1 and French, and there would be no disruption of learning from preschool or if learners transferred midway through their primary education to a non-bilingual school (ARED Citation2014). Wherever possible, two cohorts were chosen in each school, one that would follow the bilingual model and one that would receive traditional (all-French) instruction, both following the national curriculum.

As an NGO with solid community development experience and a strong long-term vision of influencing policy as well as practice, ARED was committed to working with communities as well as through the existing formal education structures to implement the simultaneous biliteracy model. This meant creating and supporting a Comité de Gestion de l’Ecole (CGE) or School Management Committee from each community, with at least three trained to participate in bilingual education implementation in their school. The training and supervision of bilingual teachers and school directors was done by ARED-trained district and regional school inspectors who had been identified as bilingual ‘focal points.’ Teaching and learning materials were developed along with teachers’ guides in Pulaar, Wolof and French. Finally, a monitoring and evaluation system was put into place, making use of existing MEN structures and national examinations.

ARED (Citation2014, 10) identifies the desired overall outcome of the program to be that learners following ARED’s bilingual model will ‘demonstrate superior mastery in reading and mathematics by the end of the program.’ A range of assessments were used that included ESVS as well as French and mathematics but neglected the national languages, a point to which I will return later. The intermediate outcomes identified (ARED Citation2018, 3) were:

(1). Teachers, school directors, and inspectors will demonstrate mastery of ARED’s bilingual teaching and learning strategies and approaches;

(2). Teaching and practicing ARED’s bilingual model will be facilitated by classroom use of the pedagogical materials produced; and

(3). MEN policymakers, school inspectors, school directors, teachers, and community members will use and support ARED’s bilingual model.

Two external evaluations were conducted with these goals in mind, including one at the end of the first funding cycle (Dalberg Citation2014) and the other in which I was involved covering the latest funding cycle 2014–2018 for the donor Dubai Cares (MWAI Citation2019), as discussed in detail in this paper.

Methods of data collection

To discuss and analyze the results of ARED’s bilingual program, this paper relies on two sources of data. The first is a large-scale mixed-methods study based on fieldwork conducted from November 2018 to January 2019 by myself and a team for an external evaluation at the end of the 2014–2018 funding cycle for donor Dubai Cares (MWAI Citation2019). The second is a follow-up qualitative study I conducted with two graduate students in July/August 2019 based on interviews with 17 key stakeholders to gather deeper understandings of the models in question, bilingual education advocacy and the state of Senegalese language-in-education policy.

The external evaluation was designed to determine to what degree and in what ways the program has been successful, attending to unintended consequences whether positive or negative, and to examine the potential of ARED’s bilingual model and implementational processes to influence change in Senegal’s language-in-education policy. Our study included an examination of program documents and bilingual teaching materials developed, as well as a re-analysis of assessment data used for ARED’s monitoring and evaluation. The main data on the model and on program implementation was generated during two and one-half weeks of intensive fieldwork.

While time and resources did not allow us to select a representative sample of the 98 schools/101 classrooms in which ARED’s bilingual model was implemented, with ARED’s help we identified a range of contexts from the four Inspectorates de l’academie (IAs) (regional education inspectorates) in Dakar/Rufisque, Kaolack and Saint-Louis, taking into consideration rurality, school size and level of implementation. Our team spoke with bilingual focal points and other school inspectors from nine of the 10 Inspections de l’Education et de la Formation (IEFs) (inspectorates of education and training of the districts) and visited schools in eight of them. We visited a total of 15 schools, interviewing or conducting focus group discussions in the appropriate languagesFootnote4 with community members and CGE representatives, school directors, bilingual teachers and bilingually educated learners. At 10 schools (6 Wolof and 4 Pulaar) we conducted our own L1 writing assessment with bilingually and non-bilingually educated learners (a total of 386) who were completing CM1, or grade 5 of primary schooling.

Most interviews and focus group discussions were led by Senegalese team leader Diagne unless we split up to speak with more people. Discussions with education personnel were conducted mainly in French with some code-switching into Wolof or Pulaar, while parents and students were engaged mostly in Wolof or Pulaar. Our fieldnotes were written directly into French; they were coded by a team of graduate students using Dedoose software, which assured us that our preliminary findings were supported, and helped us to select representative quotations as evidence. Because any original quotations in national languages are in audio files but not in written ones, they are provided here in French with our English translations.

There were some limitations to our data. First, we visited more schools using Wolof (11) than we did schools using Pulaar (4), an imbalance we discovered too late to change, affecting the results of the student writing assessments in L1 as well as documentation of community support. We dealt with this by assessing students in all four Pulaar schools, and were somewhat reassured that community reactions were similarly positive in the schools we did visit, no matter which national language was used. Another limitation was that school inspectors were on strike at the time of our visit, requiring us to call them personally to request meetings; fortunately, most came to their offices for interviews and some joined us on the school visits, which incidentally provided us with a clear demonstration of their commitment to the bilingual program.

Our main limitation was that the second and final cohort of bilingually educated learners was already in CM1 (grade 5) and therefore no longer being taught bilingually, so we were not able to observe bilingual lessons, and stakeholder responses were based on past experience. We found it difficult to elicit details about the challenges of implementation, since many had been overcome years before. Fortunately, most personnel were still in place; in most cases, we found the cohort still being taught by their bilingually trained teacher, who had followed them through the grades, and even if there were traditionally educated learners mixed into some classes, school personnel had no difficulty indicating the bilingually educated ones. We took advantage of the mixed classes to comparatively assess their writing in L1 and French.

As a follow-up to the external evaluation, I returned in mid-2019 with a small research team to focus on questions that remained concerning bilingual education policy and practice in Senegal with implications for other multilingual contexts. We conducted focused interviews with 12 key stakeholders, including NGO actors, university linguist-educators, technical advisors, MEN officials and donors to explore two main questions related to ARED’s approach and to language-in-education policy change:

(1). How does ARED’s simultaneous biliteracy model function in practice, and what is the pedagogical thinking underlying it?

(2). What is the current state of MEN policy regarding language of instruction, and how has it been informed by ARED’s work?

We also explored a third question that will be touched upon in this paper but that merits further exploration in the future, and that is the role of Senegalese bilingual education advocates who call themselves ‘militants’ for the use of national languages in education.

Overall results of the evaluation

The findings of the external evaluation were consistently positive with regard to the bilingual model and the outcomes of its implementation in terms of stakeholder satisfaction, learner achievement, and even unintended outcomes. As someone who has participated in and evaluated MLE programs in low-income contexts for many years, I found the support for ARED’s model at all stakeholder levels unprecedented. Our team heard the same positive comments from regional and district school inspectors including the bilingual focal points/trainers, school directors, community members, parents and CGE members, bilingual and traditional teachers, bilingual and traditional learners, and even two high-ranking officials at the Ministry of Education in Dakar. No stakeholder with whom we spoke was dissatisfied, even when we asked about the challenges of implementation, which are discussed later in this section. The main findings of the evaluation, with evidence in the next section, were the following:

Widespread success of the students in the bilingual program, and superior performance to their peers attending traditional (all-French) classes, as evidenced by yearly district-wide assessments, the expressive writing assessment our team administered, the national primary school leaving examination (CFEE), and promotion to secondary schools;

Active engagement of stakeholders at all levels;

Stakeholder conviction that ARED’s bilingual model compares favorably to other models due to its progressive, systematic and coherent approach;

‘Exhaustive’ engagement by ARED in the implementation process, as evidenced by support to trainings and follow-up and provision of textbooks on time and in appropriate quantities;

Nearly universal call for généralisation, or system-wide implementation of ARED’s bilingual model, including expansion into additional languages (MWAI Citation2019).

Our evidence of each of these findings is described in the following sections. We also uncovered a number of unexpected or at least unplanned outcomes of ARED’s bilingual program. The first was that the bilingual and traditional cohorts did not receive completely different ‘treatments’ in an experimental sense, because bilingual students had taught their peers some literacy in the L1, and bilingual teachers had shared their L1 knowledge and bilingual teaching strategies with their colleagues working in traditional classrooms. Some traditional teachers sought permission and were allowed to convert to bilingual teaching, basically eliminating the ‘control’ (non-bilingual) cohorts at their schools. We came up with the term ‘positive contamination’ to describe how the experimental design had been compromised, but for good reason – the bilingual approach had won stakeholders over.

A second unexpected outcome was the reported synergy that developed between schools and communities, as bilingual students taught family members how to read and write in their own languages, and family members started helping children with their homework. These reports, from students, parents and CGE members, were strikingly similar to those I heard in Mozambique in communities with experimental bilingual schools (Benson Citation2000) with regard to spontaneous intergenerational literacy activities. Some of the comments below support this theme.

A final unexpected outcome of the program was the degree of consciousness raised about the importance of the national languages in education in Senegal. Stakeholders at all levels mentioned the importance of national languages, and not only to those who were L1 Wolof or Pulaar speakers. Community members with other mother tongues reported that bringing Wolof and Pulaar into formal education made their own languages more visible and valuable, which suggests that bilingual education encourages inclusiveness rather than excluding certain groups, as argued by detractors of bilingual education (see e.g. Alidou Citation2010).

The overwhelmingly positive outcomes of the external evaluation should be tempered with the understanding that because our fieldwork took place after the program had ended, stakeholders may have had stronger memories of what worked and weaker memories of issues that were no longer part of their daily experiences. Indeed, when an MLE program is implemented, issues like parent support, teaching strategies and linguistic questions are most acute in the early years (Malone Citation2016). We heard reports that such issues had been addressed early on in this program, and the remaining challenges discussed by stakeholders seemed relatively minor. It was evident that no one saw the issues as detracting from their widespread calls to implement bilingual education more widely in Senegal. We did identify both technical and programmatic issues that could be addressed in an expansion of the program. The following were technical issues related to the bilingual approach:

Some educators seemed to misunderstand interlinguistic transfer in the ARED model, as indicated by their use of terms like ‘interference’ or ‘equivalence,’ suggesting that some still see the non-dominant L1 as interfering with the dominant L2, even though they see that the L1 facilitates understanding.

Formal assessment was done only or mainly in French, missing opportunities to assess L1 literacy and curricular content knowledge that might be best expressed in the L1.

Students exhibited stronger receptive language skills (listening and reading) than productive ones (speaking and writing), as indicated by our writing assessments, suggesting that not all educators see the greater potential for student self-expression offered by L1 use.

For mathematics and the sciences, teachers expressed concern about finding ‘equivalent terminology’ in the L1 and L2, suggesting that they were looking for exact translations of French terms in the national languages, rather than focusing on how to explain concepts appropriately and authentically in the L1.

We also identified two major implementational issues that would need to be addressed if the program were expanded:

(1). Teacher mobility is high across the country but particularly in the rural areas (ARED Citation2018). Bilingual inspectors/focal points, trainers and teachers were more likely than traditional teachers to stay where they were posted, but were still subject to unrelated factors like marriage. Because implementation of a bilingual program necessitates training, it will be important to find sustainable ways to train educators and incentivize them to stay in appropriate schools and regions.

(2). Linguistic heterogeneity is a naturally occurring characteristic of some communities, particularly but not limited to those in semi-urban and urban areas. Not infrequently, more than one home language is spoken in any given community, even if certain non-dominant languages are more widely spoken than others. ARED reportedly dealt with this well, supporting inspectors, school directors and SMCs to make consensual decisions about which of the national languages would be used in their bilingual schools.

Finally, our research identified a serious threat to the future of ARED’s work on the simultaneous biliteracy approach and to MEN’s possible adoption of a language-in-education policy favoring bilingual education based on national languages. As noted above, ARED’s funding cycle had come to a close, and the last bilingual classes in grade 4 (CE1) had been held the year before. Our fieldwork in late 2018 coincided with the large-scale rollout of a different project that appeared to many stakeholders to threaten the wider adoption of ARED’s bilingual model that they were calling for. A USAID early grade reading intervention project known as Lecture Pour Tous (Reading for All), or LPT, began moving into regions where ARED had been working. Using national languages, but only for phonemic awareness in the early primary grades, LPT was being inserted into traditional all-French schools on a large scale, using educational personnel who had been trained in bilingual education by ARED. This was at the very least confusing for those who had been involved in ARED’s bilingual program, who were vocal in their critiques of LPT and their clarity that it was not bilingual education. I will return to this point in discussing the results from stakeholder perspectives.

Selected evidence of the results

This section reports representative comments and other data to support the overall findings reported above. As mentioned above, quotations are reported in French and English. They are identified by interview date, stakeholder occupation, school district (IEF) and national language used in the school (W for Wolof or P for Pulaar).

Evidence of student success

The principal goal of the ARED program was for learners who had been educated bilingually from grades 1–4 (corresponding to levels CI to CE2 in the Senegalese system) to demonstrate better learning achievement than those in the traditional (all-French) system. The first indication of the widespread success of bilingual learners came from anecdotal reports of educators at all levels, who described bilingual learners as joyous and motivated to learn. An inspector summarized the accomplishments of bilingual learners in this way:

A la première étape, au CI-CP … la meilleure école qui a été primée dans le cadre du PAQEEB était une école ARED … Parce qu’en tous cas à [notre IA], nous avons constaté un gain cognitif à tous les niveaux. L’enfant qui commence par sa langue a un gain. Et ça s’est reflété dans les résultats scolaires.

At the first stage, in CI-CP [grades 1–2] … the best school that won the PAQEEB [Project to improve the quality and equity of education] award was an ARED school … our IA [region] has seen a cognitive gain at all levels. The child who starts with his or her language has an advantage, and that was reflected in the school results. (2018.11.30 Inspector, Dakar, W)

ARED est venu à un point nommé pour adresser le problème crucial de la lecture. Si on regarde la première génération, on a des résultats très satisfaisants des CM2- presque 90% de réussite. Ces enfants sont plus forts. Ces élèves savent décoder et décortiquer les textes.

ARED came at a perfect moment to address the crucial issue of reading. If we look at the first generation, we have the very satisfactory results of [last year’s] CM2 [CFEE] – almost 90% success rate. These children are stronger. These students know how to decode and dissect texts. (2018.11.28 School director, Nioro, W)

Tu as des enfants extraordinaires; tous les élèves sont passés. Il y a eu un taux de réussite de 100%. Tous les élèves qui ont fait ARED dans mon école sont partis! Mais ils ont réussi en masse.

You have extraordinary children; all of the students have passed. There was a 100% success rate. All the students who did ARED in my school have gone on [to secondary]! But they succeeded en masse. (2018.11.26 School director, Kaolack commune, W)

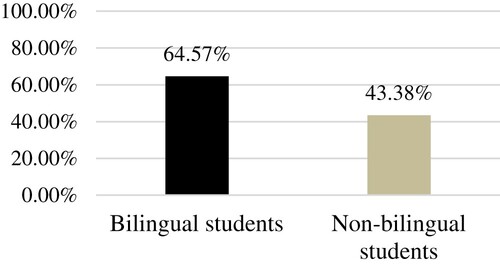

A second source of assessment data were the Early Grade Reading and the Early Grade Math Assessments (see FHI360 Citationn/d for a brief explanation of these cross-national assessments known as EGRA and EGMA). These had been conducted in French by MEN beginning in 2014 on 500 students each from bilingual and traditional classes, and again in 2016 and 2017 to monitor learning. Although significant attrition in the sample may have skewed results, ARED (Citation2017) reported significantly higher results for bilingual learners in both reading and mathematics. summarizes the EGRA averages for bilingually vs. traditionally taught students over time.

Table 1. EGRA results from 2014–2017 for the comparative sample.

While practice and age effects could explain some growth over time, the significant differences in favor of bilingually taught students demonstrate a positive effect of ARED’s simultaneous biliteracy approach as assessed in the L2. What might their results have been if assessed in the L1?

As already noted, formal assessment in the L1 was rare, though we did hear from some school inspectors that learning assessments in the early grades was done in the L1 on local or regional levels, at least for the Language and Communication part of the curriculum. Bilingual students themselves expressed pride in their national language skills; for example, one told us that their L1 literacy was better than their teachers’:

On était les plus forts parce que des fois on rectifiait les erreurs de notre maîtresse.

We were the strongest, because sometimes we corrected our teacher’s mistakes. (2018.11.27 Bilingual student, Kaolack commune, W)

L1 assessments were translated into French and assessed for errors by Wolof- and Pulaar-speaking graduate students of linguistics. L1 and L2 assessments were then coded on a scale of 0–14 based on language complexity and number of errors, with 14 representing ‘multiple sentences (medium to long) with 0–2 errors’ and 0 being illegible. On the L1 writing assessment, bilingual students (M = 8.50, sd = 4.52) scored higher than traditional students (M = 6.39, sd = 4.47), the difference being statistically significant and moderately meaningful (t = −4.000, p < .001, d = 0.47). This demonstrates that students educated bilingually in these sample schools had significantly better L1 writing results than those in traditional programs. Among the students from bilingual programs, there was no difference between Pulaar and Wolof results, suggesting that ARED’s approach is equally effective in the two languages (MWAI Citation2019, 99–100).

On the L2 writing assessment, bilingually taught students scored significantly higher (M = 8.23, sd = 3.68) than traditionally taught students (M = 6.44, sd = 4.07), with a moderately meaningful difference (t = −4.12, p < .001, d = 0.45). This means that ARED’s bilingual model did not disadvantage students in their learning of French for this school sample; on the contrary, bilingually taught students seemed to have an advantage in French as well as their national languages. This finding is consistent with international research (e.g. Thomas and Collier Citation1997, Citation2002; Walter and Benson Citation2012) and shows that investment in L1 literacy has positive effects on L2 literacy due to interlinguistic transfer (Bialystock Citation2001; Cummins Citation2009).

Support for the simultaneous bililteracy model and materials

As mentioned above, stakeholders at all levels expressed support for ARED’s bilingual model. The main reasons given were the following:

Its simultaneous approach to beginning literacy in both the national language and French;

Its systematic, progressive approach to teaching curricular content in an understandable manner; and

Its coherence with the national curriculum (MWAI Citation2019).

Inspectors and teachers often mentioned the gain de temps or time-saving aspect of the simultaneous approach due to transfer from L1 to L2. The 30-minute L1 lesson in each subject was followed by a 30-minute period for French, but since the content had already been taught and understood, only or mainly French vocabulary was needed, and this did not require the full 30 min, allowing more time for other activities or lessons. As one bilingual teacher noted:

Effectivement, aussi sur le niveau des acquis et de l’apprentissage, lorsque nous décrochons de la langue locale vers la langue française, on avait plus d’activités en langue française parce que les enfants avaient déjà des acquis en langue locale. Dans ma classe, on pouvait faire 5 à 6 activités et ça ne peut que renforcer la qualité de l’apprentissage.

Indeed, [the benefit was] also at the level of learning outcomes and teaching. When we moved from the local language to French, we could have more activities in French because the children had already learned in the local language. In my class, we could do five to six activities and this can only reinforce the quality of learning. (2018.11.28 Bilingual teacher, Nioro, W)

Ce sont des textes adaptés au milieu. C’était très fort ici. Les élèves s’intéressaient. Ces textes parlent du vécu de l’enfant.

These are texts adapted to the environment. They were very meaningful here. The students were interested, as these texts speak of the child’s reality. (2018.11.23 School director, Podor, P)

Sur le plan des manuels, mais je n’ai jamais vu ça! Je suis de la deuxième génération et même les parents étaient contents. Les enfants avaient 6 manuels … nous étions très gâtés en manuels. On ne peut pas manquer de le dire.

In terms of textbooks, I've never seen anything like it! I am from the second generation [of bilingual teachers] and even the parents were happy. The children had six manuals … we were very spoiled in textbooks. We cannot fail to say so. (2018.11.28 Bilingual teacher, Nioro, W)

Ce sont des manuels riches. Même cette année, même s’il n’y a pas d’expérimentation, on continue à utiliser ces manuels. Même hier, il y a un enseignant de CE2 qui est venu me demander ces manuels et je donne à chaque élève ces manuels. Parce que vraiment ces manuels sont bien faits, des textes très riches et en phase avec le curriculum. Donc même les enseignants les utilisent pour l’enseignement apprentissage.

These are rich textbooks. Even this year, even if there is no experimentation, these manuals are still being used. Even yesterday, a third grade teacher came to ask me for these textbooks and I give each student these textbooks. Because these textbooks are really well done, very rich texts and in line with the curriculum. So even [non-bilingual] teachers use them for teaching and learning. (2018.11.30 School director, Dakar, W)

[L'enseignement bilingue] m'a vraiment facilité la tâche … . d'abord, on le faisait en wolof, puis nous sommes passés au français. J’ai appris en même temps que les élèves. Si vous voyez un élève bilingue et un élève traditionnel, vous voyez une grande différence en comparant leur éducation. Nous enseignons à l'enfant, l'enfant est éduqué … il transférera ses connaissances dans la vie de tous les jours … en tant qu'enseignant, [l'éducation bilingue] nous rend la tâche plus facile.

[Bilingual teaching] really made it easier for me … first, we did it in Wolof, and then we transferred to French. It taught me as it taught the students. If you see a bilingual student and a traditional student, you see a big difference, comparing their education. We teach the child, the child is educated … he will transfer his knowledge into everyday life. In any case, as I told you earlier, I don't want this to stop. We have to keep going. Because [bilingual education] makes it easier for us. (2018.11.26 Bilingual teacher, Kaolack commune, W)

Parent and community perceptions

The impact of the bilingual program was apparent in the comments of parents and CGE members. These are some examples of the diverse reasons people gave for their consistent support:

Nous sommes conscients de l’utilité de la langue maternelle, nous souhaitons que cela soit introduit dans toutes les étapes même au secondaire. On ne doit pas l’arrêter; les enfants viennent à la maison nous montrer comment on lit le wolof et comment on nomme les choses et nous rectifient. On entend du wolof riche et de niveau élevé avec les enfants.

We are aware of the usefulness of the mother tongue. We want it to be introduced in all stages, even in secondary school. We must not stop it; the children come to the house to show us how to read the Wolof and how to name things and correct us. We hear rich and high level Wolof with the children. (2018.11.27 Parent leader, Kaolack commune, W)

Ce programme est utile parce qu’il permet de sauvegarder notre patrimoine linguistique, qui n’est pas, d’ailleurs, à l’écrit.

This program is useful because it helps to preserve our linguistic heritage, which is not, moreover, in writing. (2019.01.08 Parent, Nioro, P)

ARED experienced initial challenges of implementation, including parents’ initial concerns about their children learning bilingually and the choice of Wolof or Pulaar in linguistically mixed communities (2019.08.02 ARED director, Dakar). The NGO held consciousness-raising workshops with community members and supported MEN inspectors chosen as bilingual focal points in working with parents and CGEs to resolve such issues. In two cases we heard about, parents who had been opposed to bilingual classes and complained loudly came back later to express their gratitude, having seen how well their children did in the bilingual class. One case was described in the following way by a bilingual teacher:

Il y avait un parent d’enfant qui venait ici là, et elle ne voulait pas le pulaar parce qu’ils parlaient le pulaar à la maison. Elle pensait que ce n’était pas la peine. Mais après, elle a compris que c’était par le pulaar que l’enfant pouvait acquérir […]. Maintenant l’élève était excellent et avait des résultats les plus hauts et la maman est venue s’excuser. Ce qu’elle nous a dit c’est qu’elle n’avait pas bien compris le programme. On l’a même emmenée chez l’inspecteur pour s’excuser.

There was a parent of a child who attended here, and she didn’t want Pulaar because they spoke Pulaar at home. She thought it wasn't necessary. But then she realized that it was through Pulaar that the child could acquire [French]. [Later] the student was excellent and had the highest results, and the mother came to apologize. What she told us was that she had not understood the program well. We even took her to the inspector's house to apologize. (2018.11.23 Bilingual teacher, Podor, P)

[A]vec ARED, ils ont un groupe de travail avec l’APE et les femmes, elles discutent sur comment aider leurs enfants à réussir à l’école. Il y a des parents qui ont appris à lire aussi grâce aux enfants. Les parents continuent à encadrer les enfants grâce à ces causeries.

[Working] with ARED, the CGE has a working group with APE [parent association] and the women, and they discussed how to help their children succeed in school. Some parents have also learned to read, thanks to the children. Parents continue to support the children through these discussions. (2018.11.27 School director, Kaolack commune, W)

C’est que j’ai constaté que si les enfants viennent à la maison et si je l’aide à mieux comprendre ses leçons j’emploie ma langue maternelle, le baynouk, et ils comprennent plus vite. C’est à travers cela que j’ai compris que s’ils apprennent par le wolof qui est une langue qu’ils parlent bien mieux que leurs parents, et le français, il pourront mieux comprendre. Les parents aussi y gagnent parce qu’on apprend le wolof mieux aussi.

It is because I have found that if the children come home and I help them to better understand their lessons, I use my mother tongue, Bainouk, and they understand faster. Through this I have understood that if they learn through Wolof, which is a language that they speak much better than their parents, and French, they will be able to understand better. Parents also benefit because we learn Wolof better too. (2018.11.27 Parent, Kaolack commune, W)

Oui c’est d’ailleurs venu très tardivement [l’éducation bilingue]. On y gagne doublement en acceptant le wolof qui n’est pas notre propre langue maternelle.

Donc c’est pourquoi la maîtresse nous a dit que ceux qui ne sont pas de langue maternelle wolof sont beaucoup plus performants … ?

Oui c’est ça; ils ont deux à trois langues qu’ils peuvent parler et deviennent plus intelligents.

Yes, [bilingual education] came very late. We have gained twice as much by accepting Wolof, which is not our own mother tongue.

So that's why the teacher told us that those who are not Wolof native speakers are much more successful … ?

Yes that's right; they have two to three languages they can speak and become more intelligent. (2018.11.27 CGE member, Kaolack commune, W)

Virtually universal call for system-wide implementation

One of the clearest indications of the positive impact of the bilingual program was our coding of 42 stakeholder calls for généralisation of ARED’s bilingual approach, meaning nationwide implementation and expansion to additional national languages, and even expansion to CM1-CM2 (grades 5–6) in the Senegalese school system. The following are some representative comments from a range of stakeholders:

Nous apprécions le modèle et nous avons aidé à le développer depuis 2006. L’expansion du modèle de la troisième phase (CM1-CM2) provient probablement de la recherche internationale, mais nous aussi, nous avons vu que les enfants devaient continuer à apprendre en L1. Ils avaient besoin de s’engager plus avec la L1 à travers le cursus scolaire … Le modèle ARED doit faire partie du PAQUET. Cela représenterait une grande opportunité parce que les gens sont ouverts à l’éducation bilingue maintenant. Nous pourrions avoir la Banque Mondiale contribuer.

We appreciate the model and helped develop it since 2006. The extension of the model to the third phase [grades 5–6] probably comes from international research, but we also saw that children needed to continue learning in the L1. They needed much more engagement with the L1 across the curriculum … ARED’s model should be part of the PAQUET [education sector plan]. This represents a great opportunity because people are open to bilingual education now. We might get the World Bank to contribute (2018.11.21 MEN official, Dakar).

Il faut consolider ce qu’on est en train de faire là où ça existe. Continuer jusqu’à la classe de CM2. Et dans les académies où on le fait, essayer de le mettre à l’échelle. Et maintenant … il faudra capitaliser … et avec ces leçons apprises, on peut aller plus vite dans les autres régions. Parce que le modèle sera déjà acquis, compris et expérimenté dans tous les domaines … Je pense que ce serait une excellente chose pour le système.

We need to consolidate what we're doing where it exists. Continue through the sixth year. And in the IAs [regions] where it has been done, try to scale it up. And now, we have to capitalize [on what we have done], and with these lessons learned, we can move faster in the other regions. That way the model will be acquired, understood and experienced in all domains … I think that will be a great thing for the system. (2018.11.27 IA Inspector, Kaolack, W/P)

Moi j’aimerai bien voir le modèle, le poursuivre jusqu’au CM2. Pourquoi pas proposer une évaluation qui intègre les langues nationales ou aussi comparer ces élèves avec les autres élèves du Sénégal. Voir les résultats. On avait l’occasion de le faire ici mais on n’a pas compris pourquoi ça s’est arrêté au CE2.

I would like to see the model followed through the sixth year. Why not propose an assessment that integrates national languages or also compares these students with other students in Senegal. Look at the results. We had the opportunity to do it here but we did not understand why it stopped in the fourth year. (2018.11.30 Inspector, Grand Dakar, W)

En général, les enfants bilingues sont meilleurs que les autres. C’est pour vous dire que l’expérimentation a bien réussi. C’est à pérenniser et à ancrer dans le cursus scolaire du Sénégal.

In general, bilingual children are better than others. This is to tell you that the experiment has been a success. It must be sustained and anchored in Senegal's school curriculum. (2018.11.26 School director, Kaolack commune, W)

Là, on était content, d’où l’importance de continuer ARED dans les écoles et même jusqu’au CM2. Maintenant arrivé, au CM2, après on pourra discuter et prendre la décision de faire au collège et au lycée.

There, we were happy, hence the importance of continuing ARED in schools and even up to the sixth year. Now, in the sixth year, after that we can discuss and make the decision to go to lower secondary and upper secondary. (2018.11.26 Bilingual teacher, Kaolack commune, W)

Notre souhait, c’est qu’il ait dans chaque école un enseignant de pulaar ou de wolof selon le milieu et que le programme de ARED continue pour toujours.

Our wish is that in each school there will be a Pulaar or Wolof teacher based on the [linguistic] surroundings and that ARED’s program will continue forever. (2019.01.08, Parent, Nioro, P)

It is noteworthy that stakeholders were not only concerned with continuing and expanding ARED’s bilingual approach to other regions, but also called for expansion through the end of primary education and beyond. In fact, ARED has already recognized the pedagogical value of extending the bilingual model to CM1 and CM2 (grades 5 and 6), developing materials and piloting them in six bilingual schools (2018.11.29 and 2019.08.02 ARED director, Dakar). This is in line with current thinking about maintaining and developing the L1 for as long as possible in the school system so that learners gain higher-level literacy as well as cognitive skills in both the L1 and the additional language(s) (e.g. Cummins Citation2009) and has implications for Senegalese society in that national languages are now being seen as educational resources (per Ruíz Citation1984, Citation2010) and more on par with French.

Implications for the adoption of bilingual education as national policy

As the evidence demonstrates, support for ARED’s approach to bilingual education is high among all stakeholders. Because the program has come to the end of its funding cycle, as is the case with NGO-supported interventions, no new bilingual cohorts have been initiated. Stakeholders at every level expressed concern with this situation, as represented by one school director’s comment:

Seulement nous déplorons le fait que les enfants ne peuvent pas continuer cette méthode. Vu qu’on a vu le taux de réussite de l’année dernière, nous souhaiterions que nos élèves continuent à apprendre le bilinguisme. Notre souhait, c’est vraiment la reprise.

We just deplore the fact that children cannot continue learning with this method. Given last year's success rate, we would like our students to continue to learn bilingually. Our wish is really for bilingual education to be repeated (2018.11.30 School director, Grand Dakar, W).

Le nouveau programme avec LPT suscite une confusion au niveau de l’instituteur, car la manière dont il déroule leur programme est à contrepied à ce qu’ARED a inculqué aux maîtres et aux élèves.

The new program with LPT creates confusion at the level of the teacher, because the way their program runs is at odds with what ARED has taught teachers and students. (2019.01.08 School director, Nioro, P).

Ils [LPT] disent que la langue nationale est une béquille … seulement pour passer à la langue française. Bon j’ai dit à un formateur … Quand tu enseignes à l’enfant comment écrire, lire et parler dans sa langue, ce n’est plus une béquille. C’est un outil pédagogique.

They [LPT] say that the national language is a crutch … just to switch to French. So I told a trainer … When you teach the child how to speak, read and write in his or her language, it is no longer a crutch. It is a pedagogical tool. (2018.11.28 Bilingual teacher, Nioro, P)

Je ne comprends pas en tous cas, ce que les gens [de LPT] font là. Voilà un modèle qui a fait ses preuves et qui a survécu et donné des résultats. Si on veut généraliser au Sénégal, pourquoi avoir donné tout cela et revenir à un autre modèle. C’est comme si on s’amusait à faire un éternel recommencement.

Anyway, I don't understand what those people [at LPT] are doing there anyway. Here we have a proven model that has survived and delivered results. If we want to generalize to Senegal, why did we put in all this effort and go back to another model? It is as if we are enjoying ourselves by forever restarting. (2018.11.30 Inspector, Grand Dakar, W)

Conclusion

Whatever happens in the evolution of language-in-education policy in Senegal, ARED’s simultaneous biliteracy approach can be seen as offering a refreshing new perspective on how to adapt a national curriculum once based on a single dominant language to accommodate both a home language or widely spoken lingua franca and a dominant language with the aim of providing quality education for young learners. The features of the approach – giving each language approximately the same attention each day, initiating literacy by using letters and sounds that the L1 and L2 have in common, and teaching the differences between languages – draw on established international theories of bilingual education including interdependence and common underlying proficiency (Cummins Citation2009) and interlinguistic transfer (Bialystock Citation2001). Side-by-side treatment of both languages nurtures metalinguistic awareness, which is already a feature of bi- and multilingual societies like Senegal’s, and the approach supports learner-based pedagogy and the development of critical thinking skills. These are precisely the skills needed to question the historical dominance of foreign languages of instruction and open people’s eyes to the potential of their own languages in educational policy and practice in multilingual countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carol Benson

Carol Benson, Associate Professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, has engaged in educational language issues internationally as a technical assistant and evaluator. She now researches policy development and innovation in the practice of L1-based multilingual education for speakers of non-dominant languages, with ongoing projects in Cambodia and Senegal. In her work and life Benson speaks English, Spanish, Portuguese, French and Swedish.

Notes

1 According to Mbacké Diagne of the Centre de Linguistique Apliquée de Dakar (CLAD), an estimated 90% of Senegal’s population use Wolof in their everyday lives (personal communication, Jan 2019).

2 I am grateful to Mamadou Amadou Ly at ARED, Sinda Ouertani at Dubai Cares and Shirley Miske at Miske Witt & Associates International, along with field team colleagues Mbacké Diagne and Erina Iwasaki, for allowing me to share results from the external evaluation and providing feedback on this article. My thanks to MWAI for the quantitative analyses of CFEE, EGRA and writing assessment results. Jërëjëf/jaaraama/merci/thank you to translators Mamadou Diallo, Mamadou Sakho, Mamé Sémou Ndiaye and Sokhna Diagne and to graduate students from l’Université Cheikh Anta Diop and Teachers College, Columbia University for translations and qualitative data coding. I bear sole responsibility for any errors or omissions in this article.

3 For their research assistance and insights during the second phase of research, my thanks go to Mbacké Diagne of UCAD and to Erina Iwasaki and Jemima Douyon of TC. Mamadou Ly and the ARED team generously shared their networks and their lunchtime meals, and continue their kind collaboration with our research up to present.

4 Interviews with education personnel were conducted in French with occasional switching into Wolof or Pulaar; interviews and focus groups with community members and students were conducted in Wolof or Pulaar. All were transcribed, then coded and analyzed using Dedoose.

5 I developed this simple tool with colleagues in Cambodia to assess learners in an L1-based multilingual education program in Tampuen or Bunong and Khmer, the dominant language (publication of results forthcoming in 2020). Various forms of analysis are possible for diagnostic purposes.

References

- Alidou, H. 2009. “Promoting Multilingual and Multicultural Education in Francophone Africa: Challenges and Perspectives.” In Languages and Education in Africa: A Comparative and Transdisciplinary Analysis, edited by B. Brock-Utne, and I. Skattum, 105–132. Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Alidou, H. 2010. “Use of African Languages for Literacy: Conditions, Factors and Processes in Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali, Tanzania and Zambia.” In Optimising Learning, Education and Publishing in Africa: The Language Factor. A Review and Analysis of Theory and Practice in Mother-Tongue and Bilingual Education in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by A. Ouane, and C. Glanz, 216–252. Hamburg, Germany: UNESCO (UIL)/ADEA. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000212602.

- ARED. 2014. Dubai Cares Pro-Forma Proposal Outline: Support Project for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal (Phase III: 2013–2018). Dakar: ARED.

- ARED. 2017. Support Project for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal: Annual Report Jan 1, 2017 - Nov 30, 2017. Dakar, Senegal: Associates in Research and Education for Development.

- ARED. 2018. Support Project for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal: Final Report Dec 1, 2014 - Nov 30, 2018. Dakar, Senegal: Associates in Research and Education for Development.

- Benson, C. 2000. “The Primary Bilingual Education Experiment in Mozambique, 1993 to 1997.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 3 (3): 149–166. doi: 10.1080/13670050008667704

- Benson, C. forthcoming. “Trilingual Rajbanshi-Nepali-English Education in Southeastern Nepal: Improving Educational Quality for Rajbanshi Speakers and Others.” In Language Issues in Comparative Education: Policy and Practice in Multilingual Education Based on non-Dominant Languages, edited by C. Benson, and K. Kosonen. Boston: Brill/Sense.

- Bialystock, E. 2001. Bilingualism in Development: Language, Literacy and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blakemore, P. 1970. “Assimilation and Association in French Educational Policy and Practice: Senegal, 1903–1939.” In Essays in the History of African Education, edited by V. Battle, and C. Lyons, 85–103. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Cummins, J. 2009. “Fundamental Psycholinguistic and Sociological Principles Underlying Educational Success for Linguistic Minority Students.” In Multilingual Education for Social Justice: Globalising the Local, edited by A. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson, and T. Skutnabb-Kangas, 21–35. New Delhi, India: Orient BlackSwan.

- Dalberg. 2014. Résumé du rapport d’évaluation d’impact du modèle ARED. Dalberg: Dakar.

- Dia, A. 2016. “ARED: Une expertise au service d’une education de qualité au Sénégal.” Education et sociétés plurilingues 41. https://journals.openedition.org/esp/930.

- Diagne, M. (2017). “Gouvernance linguistique et émergence socio-économique au Sénégal. Sciences & Techniques du Langage.” Revue du Centre de Linguistique Apliquée de Dakar 12, 93–109.

- Diallo, I. 2010. Politics of National Languages in Postcolonial Senegal. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press.

- Diallo, I. 2011. “‘To Understand Lessons, Think Through Your own Languages.’ An Analysis of Narratives in Support of the Introduction of Indigenous Languages in the Education System in Senegal.” Language Matters 42 (2): 207–230. doi: 10.1080/10228195.2011.585655

- DPLN. 2002. Etat des lieux de la recherché en/sur les langues nationales (synthèse). Dakar: Direction de la Promotion des Langues Nationales/Ministère de l’Enseignement Technique, de la Formation Professionelle, de l’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales. http://www.soninkara.org/ressources/soninkara-pdf/DPLN-etatdeslieux.pdf.

- Eberhard, D., G. Simons, and C. Fennig, eds. 2019. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 22nd ed. Dallas, TX: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com.

- Faty, El Hadji Abdou Aziz. 2015. “La « haalpularisation » ou la mise en discours de la culture et de la langue pulaar au Sénégal. Processus et enjeux.” [The “Haalpulaarization” or the “Enwordment” of Pulaar Language and Culture in Senegal. Processes and Stakes.] Cahiers d’Études africaines 217: 67–84. https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/18011. doi: 10.4000/etudesafricaines.18011

- FHI360. n/d. EGRA and EGMA. Washington, DC: Education Policy and Data Center, FHI360. https://www.epdc.org/data-about-epdc-data-epdc-learning-outcomes-data/egra-and-egma.

- Hornberger, N. 2002. “Multilingual Language Policies and the Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Approach.” Language Policy 1 (1): 27–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1014548611951

- Hovens, M. 2002. “Bilingual Education in West Africa: Does it Work?” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 5 (5): 249–266. doi: 10.1080/13670050208667760

- Juillard, C. 2017. “L’enseignement bilingue à l’école primaire au Sénégal.” Éducation et sociétés plurilingues 42: 73–77. http://journals.openedition.org/esp/1126.

- Malone, S. 2016. MTB MLE Resource kit, Including the Excluded: Promoting Multilingual Education. 5 Booklets. Bangkok: UNESCO. https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/mle-advocacy-kit-promoting-multilingual-education-including-excluded.

- Maurer, B. 2011. “LASCOLAF et ELAN-Afrique : d’une enquête sur les langues de scolarisation en Afrique francophone à des plans d’action nationaux.” Le français à l'université 16: 1. http://www.bulletin.auf.org/index.php?id=276.

- MEN. 2013. Programme d’Amélioration de la Qualité, de l’Equité et de la Transparence (PAQUET). Secteur Education Formation 2013-2025. Dakar: Ministère de l’Education Nationale. http://www.onfp.sn/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/cellule-genre-paquet-proogramme-d-amelioration-de-la-qualite-de-l-equite-et-de-la-transparence-2013-2025.pdf.

- MEN. 2019. Modèle harmonisé d’enseignement bilingue au Sénégal. Dakar: Ministère de l’Education Nationale.

- MWAI. 2019. Report of the External Evaluation of the Support Program for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal. Prepared for Dubai Cares by C. Benson, S. Miske, E. Iwasaki, M. Diagne and M. Meagher. Shoreview MN: Miske Witt and Associates, International.

- Nocus, I., P. Guimard, and A. Florin. 2016. Synthèse de l'évaluation des acquis des élèves ELAN – Afrique Phase 1 2013-2015. Paris: OIF. https://www.francophonie.org/IMG/pdf/synthese_cren_elan_web.pdf.

- OIF. n/d. ELAN École et langues nationales. Une offre francophone vers un enseignement bilingue pour mieux réussir à l’école. Paris: Organisation internationale de la francophonie. https://www.francophonie.org/IMG/pdf/OIF-ELAN-DEF.pdf.

- Ruíz, R. 1984. “Orientations in Language Planning.” Journal of the National Association of Bilingual Education 8: 15–34.

- Ruíz, R. 2010. “Reorienting Language-as-Resource.” In International Perspectives on Bilingual Education: Policy, Practice, and Controversy, edited by J. Petrovic, 155–172. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Sarr, K. 2013. ““We Lost Our Culture with Civilization”: Community Perceptions of Indigenous Knowledge and Education in Senegal.” In Language Issues in Comparative Education, edited by C. Benson, and K. Kosonen, 115–131. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Sarr, K. 2020. “Conduit and Gatekeeper: Practices and Contestations of Language Within Informal and Formal Education in Senegal.” In The Palgrave Handbook of African Education and Indigenous Knowledge, edited by T. Falola and J. Abidogun. New York: Springer.

- Thomas, W., and V. Collier. 1997. School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. http://www.partinfo.se/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Thomas-Collier97.pdf.

- Thomas, W., and V. Collier. 2002. A National Study of School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students’ Long-Term Academic Achievement. Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence. http://cmmr.usc.edu//CollierThomasComplete.pdf.

- UIS. 2019. Education and Literacy – Senegal. Montréal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. http://uis.unesco.org/country/SN.

- Walter, S., and C. Benson. 2012. “Language Policy and Medium of Instruction in Formal Education.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Language Policy, edited by B. Spolsky, 278–300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.