ABSTRACT

The study focuses on the assessment of young refugee students, and the role of language and parents therein. Low achievement at tests can stem from lack of knowledge of the content being tested. However, it can also be due to low proficiency in the language of testing. Additionally, poor communication between refugee parents and schools caused by language or cultural differences may lead to underestimation of children’s potential. We investigated, first, to what extent the language factor affects the performance of young Syrian refugee students in the Netherlands in mathematics and, second, the validity of parents’ judgements of their children’s mathematics ability. A linear mixed-effects model with random intercepts per participant was used to analyze the data. Results showed that the students performed significantly better in their mother tongue than in the school language. Additionally, parents’ ratings of their children’s mathematics ability correlated significantly with the mathematics scores on both versions of the tests. The study confirms the value of linguistically appropriate assessments and parental assessment when accommodating refugee students.

In 2011, civil war broke out in Syria. Since the beginning of the war, and according to UNHCR, more than 5 million people have fled Syria (Operational Portal, Citationn.d.). According to UNICEF, 30% of the total refugee population in Europe were children and 27% came from Syria (Unicef.org. Citation2019). In 2017, the UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs published a document that showed that the Netherlands, where the present study is situated, hosted almost 200,000 of these refugee minors. One of the biggest challenges faced by these children and their host schools is that children, and their parents, do not speak the school language when they arrive. Amongst others, this creates a language barrier that complicates the communication with parents and the assessments of their children (Europe-Perae Citation2018; Tudjman et al. Citation2016). Given that each assessment relies to a certain degree on language, children’s performance may reflect a difficulty in understanding the question rather than inability to solve the actual problem that the assessment addresses. What makes the issue even more pressing is that the Dutch education system, like the German system, is organized around a system of early tracking. Children start Kindergarten at the age of four and they complete primary school at age 12. The outcomes of a nation-wide student tracking system (CITO) as well as advice from the teacher in the final grade determine if children will follow pre-vocational or pre-university education. Because of the early separation into different educational tracks, many refugee children may be unable to catch up in the language of assessment. Therefore, the current study focuses on the assessment of refugee children in the final grades of primary education, the role of language therein, and explores the validity of parents’ assessment of their children's educational attainment in mathematics as an extra tool that may support schools in assessment.

It is well-known that students with migrant backgrounds, including refugees, are underrepresented in scientific tracks of education and their abilities are at risk of being underestimated (Feinberg Citation2000; Fraine and McDade Citation2009; Freeman and Crawford Citation2008; Klingner and Artiles Citation2006; Ruhose and Schwerdt Citation2016; Shapira Citation2012). This underestimation usually results in lowering the chances of refugee children after graduation to reach decision making positions where they can contribute to an improvement of the situation for their successors. This is also resulting in the hosting country losing the potential of this population. On average, third-country nationals across the EU fare worse than EU citizens in terms of employment, education, and social inclusion. They are also at a much larger risk for early school leaving, poverty and social exclusion (EU Citation2017).

An important factor that may contribute to this underestimation is the students’ language status. They are second language learners or emergent bilinguals (see for instance García and Kleifgen Citation2010) who are suddenly and emergently exposed to an unfamiliar language at a later age. This new language is typically used in the assessment of academic achievements, also in what are considered to be less verbal school subjects such as science and math, and lack of proficiency in this language may prevent students from showing their true potential in these subjects (Shaw Citation1997). The current study investigates the assessment of mathematics abilities in relation to refugee students, an under-researched but highly relevant population (see for instance Lee Citation2005). The increasing influx of refugees over the last years presents teachers with an ongoing challenge to assess the students (Shapira, Citation2012, Citation2018). Moreover, as refugee students’ education is often interrupted or limited and characterized by multiple transitions (Browder Citation2018; Dryden-Peterson Citation2015; Herzog-Punzenberger, Le Pichon, and Siarova Citation2017), they are particularly vulnerable (Lustig Citation2010). Therefore, adequate assessment and research into the factors that can contribute to the improvement of assessments are urgently needed. The current study approached mathematics assessment of refugee students from two angles: the impact of testing language and the validity of parental assessment.

The impact of testing language on second language learners’ performance

Previous research has investigated how the language of testing affects bilinguals’ performance on standardized norm-referenced tests in clinical and educational settings. The present study is primarily concerned with educational settings, but research in clinical settings can also illustrate the consequences of ignoring emergent bilingual children’s limited proficiency in the language of assessment. Clinical and educational fields deal with similar issues, and educational research can benefit from insights based on clinically-oriented research.

For instance, according to Kohnert (Citation2010), low performance in language tests administered in the second language may lead to misplacement of second language learners even though their low performance may mainly stem from limited language exposure. In particular in cases where the second language is still at a very early stage of development, and the first language is the dominant language, assessments in the first language may present a more accurate reflection of a child’s ability (Fredman and Centeno Citation2006). Because in bilingual development, language skills are typically distributed and uneven (Kohnert Citation2010), the International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommend to test these children in both the first and the second language in order to guarantee more equitable assessments (IALP Citation2011). These examples from clinical settings illustrate the risk for underestimation of children’s potential. They resemble the risk that emergent bilinguals face in educational settings when they are tested using the school language and have their scores compared to normative data based on students who are dominant in the school language. Indeed, whilst the recommendations of testing using both languages of bilinguals may have been taken seriously by speech pathologists, the question may be raised whether they have reached the school context to the same degree. Bilingual children are still often assessed at schools in the school language only and the parents’ opinion about the level of their children may be too often overlooked.

In educational settings, the importance of language for learning mathematics has been emphasized in previous research (Cummins and Takeuchi Citation2019; Kempert, Saalbach, and Hardy Citation2011; Kersaint, Thompson, and Petkova Citation2009; Lee Citation2005; Solano-Flores and Trumbull Citation2003). For example, Abedi and Lord (Citation2001) assessed eighth grade students in Los Angeles on twenty unmodified items of mathematics assessment from the National Assessment of Educational Progress together with modified items with reduced linguistic complexity (problems with numeric format). The unmodified items selected for inclusion were judged to be linguistically challenging (arithmetic word problems). The participants were assigned to two groups: English language learners and English-dominant students. Abedi and Lord (Citation2001) found an advantage for English-dominant students over English language learners, particularly in modified test versions and of the simplified modified versions over the arithmetic unmodified word problems format. This draws attention to the essential role that language plays in testing and assessing non-language content-based subjects, such as mathematics performance (Abedi and Lord Citation2001; Kempert, Saalbach, and Hardy Citation2011).

Indeed, in 2016, Le Pichon and Kambel (Citation2016) investigated the effect of school language on the performance of elementary school children in the interior of Surinam by excluding the barrier of the testing language. They assessed one hundred Grade two students in both their native language (Saamaka) and the school language (Dutch) using Early Grade Mathematics Assessment. Analyzing the results, the researchers made a distinction between the questions that were dependent on simple arithmetic problems and hence less language-dependent, and the questions that needed more verbal reasoning and were more language-dependent. Consistent with the results of Solano-Flores and Trumbull (Citation2003), the results of their study indicated that the effect of the testing language was more pronounced in the latter category, which showed an advantage of testing in the home language over testing in the school language.

Other research demonstrated the advantages of holistic multilingual testing and of testing in the first language. For example, Shohamy (Citation2011) compared the mathematics performance of two groups of migrant students from Russia living in Israel: one group was tested in their second language (Hebrew) while another group was tested using a bilingual test in both the first and second language (Russian and Hebrew). The second group outperformed the first group, demonstrating the positive effect of multilingual assessment and the advantage of including the first language. This conclusion is corroborated by a study situated in the Basque Country with bilingual Spanish-Basque students, which showed that students scored better in mathematics when they took the test using their first language (Spanish) than when they used the language of instruction (Basque) (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2017).

The studies described above show the important role of the testing language for bilinguals in order to get a fair overview of their mathematics level. Abedi and Lord (Citation2001) examined the role of the language proficiency level in solving mathematics, but did not assess the children using their dominant, and possibly stronger language, unlike Le Pichon and Kambel (Citation2016). Shohamy (Citation2011) investigated the effect of using a bilingual test on the performance of students in mathematics tests and Gorter and Cenoz (Citation2017) examined the effect of testing using L1. However, none of these studies considered the subgroup of children with a refugee background. The present study examines therefore whether tests using the L1 are also relevant to the population of Syrian refugee students in the Netherlands and whether parents’ opinions may provide a valid indication of their children's actual level in mathematics. In the next section, previous research on parental assessment is discussed.

Using parental assessment to measure refugee students’ abilities

Not only the forced displacements that precede arrival in the host country impose interrupted and/ or limited schooling (Browder Citation2018), but once arrived in their host country, refugee families are likely to be frequently relocated from one camp to the other (e.g. Le Pichon Citation2020), leading to additional interruptions in the education continuity of students (Gogolin Citation2011). These circumstances often hamper the teachers’ ability to obtain a comprehensive view of refugee student’s levels (Dryden-Peterson Citation2015). In addition, assessment instruments in the dominant language of these students may not always be available (Browder Citation2018). This situation raises the need for finding alternative methods to assess their abilities in a reliable way, for example, by consulting with parents and caretakers. Families and communities are in fact a crucial part of the learning continuity of the children and an indispensable support for schools (Herzog-Punzenberger, Le Pichon, and Siarova Citation2017). Involving parents in assessing the development of their children may offer additional advantages. Not only can it help bridge the gap between the students’ parents or caretakers and the teachers in the educational settings by creating a mutual trust between them, but it can also provide teachers with a valid source of information about the student’s skills (Bedore et al. Citation2011). It may also help teachers to better understand the challenges faced by some students who may have suffered from limited or interrupted formal education (Browder Citation2018).

Previous research considered the validity of parental involvement in the language assessment of bilingual children and found that parents’ assessment of their children’s language history predicted whether children had a language disorder (Boerma and Blom Citation2017). Bedore and colleagues (Citation2011) found a positive correlation between the answers from the parents of bilingual children to the questionnaires in which they assessed their children’s language proficiency and the performance of their children in the tests in both languages, suggesting that parental assessment is reliable. Teachers, in contrast, underestimated the proficiency level of the students in their native language. These results may support the validity of including parents in the assessment process to obtain a more accurate representation of the student’s language abilities. However, migrant parents often have little opportunities to engage with schools due to perceived or actual language barriers as well as a priori low expectations of parental knowledge (Le Pichon Citation2020; Schneider and Arnot Citation2018).

Little is known about the parental assessment of mathematical skills, and the few studies that are available focus on gender differences (Räty et al. Citation2002; Yee and Eccles Citation1988), or on the challenges of parental involvement in mathematics (Sheldon and Epstein Citation2005). However, the studies reviewed above show that parental assessment of their children’s language development is considered to be valuable, and the same could be true for parental assessment of their children’s abilities in other subjects, for instance, in mathematics. Therefore, it is important to know whether parental assessment of children’s mathematical level is valid. If the parental assessment of the mathematical level of their children is valid, it would provide schools with an option to better assess refugee children’s mathematics abilities in the first years after arrival. Correlations with actual math scores (using multilingual testing) provides an estimate of the validity of parental assessment. For these reasons, the current study investigates the validity of refugee parents’ rating of the mathematical skills of their children by comparing parental assessment with test results.

Research questions and predictions for the present study

The current study examined if the testing language affects the performance of refugee students through an assessment of their mathematical skills. More specifically, we investigated the effect of the language on the performance of thirty-two Syrian refugee students in the Netherlands. Mathematics was chosen because it is given a high priority at schools (Cummins and Takeuchi Citation2019; Sheldon and Epstein Citation2005) and considered a good indicator of children’s cognitive abilities (Kempert, Saalbach, and Hardy Citation2011). In addition, previous research asserted the cruciality of language in content-based areas like mathematics (Abedi and Lord Citation2001; Lee Citation2005; Solano-Flores and Trumbull Citation2003). Since testing using the dominant language of the emergent bilingual population may not always be feasible (Solano-Flores and Trumbull Citation2003), another way of collecting information for the purpose of determining students’ level was investigated as part of this study as well, namely, whether parents could provide a valid indication of their children’s level in mathematics.

The research questions are formulated in (1) and (2).

To what extent does the testing language influence the performance of Syrian refugee students in a mathematics test?

To what extent is parental assessment of Syrian refugee students’ skills in mathematics a valid measure of mathematics ability?

With respect to the first research question, considering findings in the literature that demonstrated discrepant performance depending on the types of questions used (i.e. verbal word problems versus numeric format) and the levels of language proficiency (Abedi and Lord Citation2001), it can be argued that it is not only the mathematical skills that play a role in the mathematical test results. Rather, other factors such as the language of the test contribute to solving word problems by either hindering or facilitating students’ performance which subsequently affects the test outcomes (Abedi and Lord Citation2001; Solano-Flores and Nelson-Barber Citation2001; Solano-Flores and Trumbull Citation2003). Therefore, students were expected to perform better on the Arabic version of the test (the dominant testing language) than on the Dutch version of the test (the school testing language).

With respect to the second research question, it was hypothesized that parents would give an assessment of their children’s level in mathematics that would correlate with the outcomes of the mathematics test, and particularly with the Arabic version of the test because children’s actual levels may be hindered by a lack of experience with Dutch.

Method

Participants

A total of thirty-two Syrian refugee students with an age range between nine and fifteen years old (M = 11.86, SD = 1.63) took part in the present study. Half of the participants were girls (n = 16). Seven participants were Kurdish-Syrian bilingual children. They declared to speak mainly Kurdish at home and to understand Syrian Arabic very well. provides an overview of the participants’ age in months recorded in the first session. The distribution of age is somewhat positively skewed as can be seen from the median and the mean. The wide age range was unavoidable in the context of the present study as the participants were recruited from a minority group distributed across the Netherlands. Therefore, we decided on a larger age range that allowed us to include more children.

Table 1. Demographic information about the participants.

In the present study, Syrian students aged nine to fifteen residing for less than five years in the country were included. The sample is fairly representative of the heterogeneity observed among refugee students (Browder Citation2018). provides an overview of the length of residence in refugee camps in the Netherlands, residence outside Syria before coming to the Netherlands, and the length of schooling in and outside Syria in months. The level of education of the participants’ parents was measured on a six-point ordinal scale. Zero represents ‘not completed primary education’, 1 stands for primary education; 2 for middle school; 3 for secondary school; 4 for higher educational institute; and 5 for university. University level is considered a higher level than educational institute, taking 4 years instead of 2–3 years of study. In addition, to be admitted to university, a student needs higher grades at the secondary school (). Traumatic experiences were measured on a five-point Likert scale using two items, namely the trauma the participating children have undergone during the war in Syria and the trauma they experienced on the way to the Netherlands (see ).

As can be seen in , the length of exposure to Dutch represented in the residence in the Netherlands and the length of schooling in the Netherlands vary among participants. In addition, comparing the duration of residence outside Syria before coming to the Netherlands to the duration of schooling shows that the participants have encountered periods of interrupted schooling.

Participants were recruited by contacting the directors of schools of international transition classes in the Netherlands and using the researchers’ network.

Material

Mathematics test

Assessments were adapted from the kids4cito website (Kids4cito, Citationn.d.). This platform contains verbal mathematical problems that are representative of the verbal mathematical problems used in Dutch education and in standard assessments part of the early academic tracking system (CITO). Dutch versions of these mathematical problems were translated into Arabic. In addition, we chose to replace Dutch proper names with Syrian Arabic names. Illustrative pictures were used to ease the students’ understanding of the assignments. To avoid the learning effect in terms of visual memory, illustrative pictures that were used in the Dutch versions were replaced by adapted equivalent pictures that could serve the same functions in the Arabic versions (Solano-Flores and Nelson-Barber Citation2001). The numbers in the questions as well as in the multiple choices were modified and the latter were pseudo-randomized in order to minimize any learning effect. Three levels of the assessment were used in accordance with the corresponding academic levels of the students, namely grade six, seven, and eight according to the Dutch standards. According to the Dutch school system, children in Grade six are between the ages of nine and 10; children in Grade seven are between the ages of 10 and 11; and children in Grade eight are between the ages 11 and 12. This strategy implies that some children were tested with assessments typically used for children at a younger age in the Dutch school system. Refugee students often have experienced travels that have prevented them from being schooled for varying and non-negligible periods of time. As a result, there is often a discrepancy between their calendar ages and their academic levels.

Another potential consequence of mobility and interrupted schooling is the likelihood that some participants lacked basic literacy skills. Therefore, we presented all participants with an auditory version to accompany the written assessment. The questions of the Dutch versions were recorded by a Dutch native speaker and the questions of the Arabic versions by a Syrian Arabic native speaker. Each version of the three levels contained 20 items. Thus, each student received 40 items in total equally divided between the two versions (Arabic-Dutch).

The assessments were newly developed and consequently psychometric information was not available. Therefore, the information about the reliability analysis that was performed to check internal consistency will be given in the Results’ section.

Parental questionnaire

The parental questionnaire was intended to collect demographic background information, the information that pertained to specific refugee experiences, and to obtain information about parental assessment of their children’s mathematics skills. 17 items were classified into two categories; personal information and assessment questions (See Appendix). The assessment section included five items that requested the parents to assess, (1) their children’s skills and proficiency in mathematics in general, (2) their children’s skills in solving mathematical word problems, (3) their children’s liking of mathematics, (4) their children’s enjoyment of mathematics, and (5) their happiness when having mathematics lessons. All five items were measured using a five-point Likert scale. Traumatic experiences were assessed using two items, asking parents to rate on a Likert-scale, the severity of traumatic experiences their children had experienced. The personal section collected information about demographics and refugee experiences and contained questions about the parents’ level of education, duration of residence outside Syria before arriving to the Netherlands in months, the length of the child’s residency in the Netherlands, and the length of schooling of the child in their home country, Syria, or in any other country before coming to the Netherlands, if applicable, to account for history of mobility. The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and distributed to the parents. The questionnaire was newly developed and hence no psychometric information was available. Reliability information will be provided in the Results’ section.

Procedure

This research was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Utrecht Institute of Linguistics. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. The Arabic versions of the information letter that contained a general outline of the project, of the informed consent, and of the questionnaire were sent to the parents by postal mails. They were notified to contact the researcher via WhatsApp or telephone when they had received this letter. Following this, the parents answered the questions, stated in the questionnaire, through telephone interviews with the first author of this study, a Syrian Arabic native speaker. An oral interview was chosen to ensure that the questions were well understood by the parents. Dates for testing sessions were set.

Two sessions were administered for each student. Half of the participants received the Dutch version in the first session and the Arabic version in the second session, while the other half received the Arabic version in the first session and the Dutch version in the second session. There is an interval of minimally one month between the two testing sessions. Each session ranged between 40 and 60 minutes. Tests were pen and paper self-paced tests. Students were tested individually in a quiet place. During the Dutch sessions, the researcher addressed the participant in Dutch while during the Arabic sessions, Arabic was used. Prior to the test, participants received instructions about the session parts. Assessments were distributed in accordance with the participants’ age category. For the written presentation, the students were assessed on papers to avoid difficulties of reading from a computer screen. For the auditory presentation of the tests, participants used headphones to listen to the questions of the mathematics tests. No feedback was provided during or after the session. However, some of the parents asked for feedback after the two sessions and were provided with information about their children’s performance. During the assessments, time was monitored manually. On completion of the test, the participants received a small gift as a present for taking part in the research.

Data analysis

Before answering the research questions, reliability of the mathematics tests and reliability of the parental assessment scale were checked because these were both newly developed and therefore, psychometric information was not available. The reliability analyses were performed in R (R Core Team Citation2018) using the alpha() function from the psych package (Revelle Citation2018). It was applied to the twenty items of the mathematics tests per testing language and per grade. It was also applied to the five items that were assessed: (1) general mathematics skills; (2) skills in solving mathematical problems; (3) child’s liking of mathematics; (4) child’s enjoying of mathematics; and (5) child’s happiness when having mathematics lessons.

In addition, and preliminary to the analyses that pertained to the research questions, the data was modeled using a general linear mixed-effect model (R Core Team Citation2018) to check whether test order and grade had an effect on the total score on the mathematics test. In linear mixed effect models, some of the error is attributed to random effects, and the error that needs to be accounted for by the regression model is reduced. The models are robust against missing data and can handle small and unbalanced datasets (see Cunnings Citation2012). To account for the repeated observations within participants, random intercepts per participant were modeled (Winter Citation2013). Firstly, since half of the participants were tested on the Dutch version first and half of them on the Arabic version first, it was checked whether test order had an effect on the total scores of the mathematics test. Therefore, order as a between-subject factor was added to the intercept-only model as a fixed-effect factor. Secondly, it was checked whether the difficulty of mathematics test-items was age-appropriate since a different set of mathematics items was presented to each grade. In order to test this, grade was entered as a fixed-effect factor in the intercept-only model. Using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, and Christensen Citation2017), the variance between participants was checked because a random intercept model assumes that intercepts between participants differ and that can be confirmed when the difference is significant.

In order to answer the two research questions, Lme4() (Bates et al. Citation2015) was used to perform a linear mixed effect model. In the statistical analysis, the model was incrementally constructed in four steps starting with the intercept-only model with random intercepts for participants. The dependent variable of the study was the sum score of the correct responses to the items of the mathematics test per language version and per participant. It was measured on a scale with a range of 0–20 for each version. To answer the first research question about the effect of language version on the total mathematics score, testing language as a within-subject dichotomous predictor variable with 0 indicating the Arabic version of the test and 1 for the Dutch version was added to the model as a fixed-effect factor. With respect to the question that examined whether there was a correlation between the total mathematics score and the parental assessment, a variable of parental assessment was created composed of the mean of the five items. For the first part of the question, parental assessment as a between-subject continuous variable was added as a fixed-effect factor to the model that contained the testing language as a fixed-effect factor. Then, to check the second part of the second hypothesis that assumed a higher correlation of parental assessment with the total mathematics score of the Arabic version, the interaction between parental assessment and testing language was added to the model that contained testing language and parental assessment as fixed effect factors. The likelihood ratio test was used to assess the model fit using the anova() function.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the children’s performance at the three levels/grades on the two versions of the mathematics test are shown in .

Table 2. Children’s mean and standard deviation of the performance on the mathematics tests.

Cronbach’s alpha showed that the internal consistency of the items of the mathematics test was sufficient as shown in .

Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha of the construct of the mathematics test.

Cronbach’s alpha for the internal consistency of the items of parental assessment indicated that the scale of the five items was highly reliable, α = .94. Therefore, a mean score of the five items per participant has been calculated.

When checking whether test order had an effect on the total score of the test, it was found that adding order did not significantly improve the model fit (χ2(1) = 0.20, p = .66). Therefore, there is no evidence that order had an effect on the total score. Also, when checking whether grade had an effect on the total score of the mathematics test, it was found that entering grade to the model did not show a significant improvement in model fit (χ 2(2) = 4.50, p=.11). As there is no evidence of an effect of grade on the total score of the participants, it can be concluded that the prerequisite of age-appropriate difficulty of the three levels of the tests has been met.

Checking for the participants’ variance, it has been found that there is a significant variance between participants intercepts (σ2 = 12.07, p < .001).

Regarding the models that were run to address the two research questions, it turned out that the model that had the best fit to the data was the one including testing language and parental assessment (). Note that based on the visual inspection of the Q-Q plot and a histogram of the residuals, the assumption of normally distributed model residuals (Winter Citation2013) was met.

Table 4. Model assessment using the likelihood ratio test.

First research question: to what extent does the testing language influence the performance of Syrian refugee students in a mathematics test?

Adding the testing language as a fixed-effect factor to the model resulted in a significant difference in the total scores between the two language versions (β =−3.063, p < .001). The students performed worse on the Dutch language version of the test than on the Arabic one.

Second research question: to what extent is parental assessment of Syrian refugee students’ skills in mathematics a valid measure of mathematics ability?

Descriptive statistics of parental assessment of the mathematics skills are (M=3.22; SD=1.12).

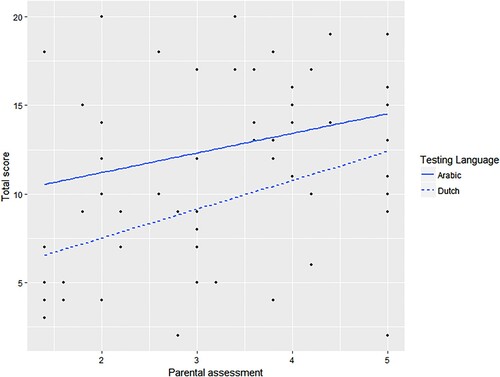

The second research question of this study was whether parents could provide a valid measurement of assessment of their children in mathematics and, if so, whether their assessment would correlate more strongly with the scores obtained from the Arabic version or with those from the Dutch version of the test. Adding parental assessment as a fixed-effect factor resulted in a significant positive effect in the total score of mathematics (β = 1.37, p = .04) revealing that with every unit increase in parental assessment, the total score of the children in the mathematics test increased by approximately 1.4 points. The interaction between parental assessment and the testing language was then checked to see whether the correlation was higher with the Arabic version of the test. Using the likelihood ratio test showed that there was no significant interaction effect between parental assessment and the testing language. suggests, however, a somewhat stronger relation for the Dutch version. shows the relationship between the parental assessment and the total score for both language versions where one line represents the Dutch version and another represents the Arabic version.

Discussion

The first purpose of this study was to examine the role of the testing language in determining the performance of refugee students. We investigated whether assessing the students in their dominant language, as it has been found to be beneficial in previous studies (Le Pichon and Kambel Citation2016), could also improve the outcomes of refugee students in the tests of a content-based subject, namely mathematics. The results revealed that there was a significant effect of testing language. Participants performed significantly better in their native language than in the school language. Thus, the first hypothesis was confirmed in line with previous studies that emphasized the importance of the role of the language of the test in the performance of bilinguals (Abedi and Lord Citation2001; Le Pichon and Kambel Citation2016). Although the present study did not test monolingual children, these results highlight the inequity of the practice of comparing students with a refugee background with monolingual peers (Kohnert Citation2010). Results show that the students perform better when they are tested using their native language.

An important implication of this result for the educational policy of refugee students is that assessments using only the school language may hide their cognitive abilities and in this case mathematics abilities. Schools should be, therefore, encouraged to use alternative methods to monolingual tests with this population, namely to assess students in their dominant language (Browder Citation2018; Cummins, Citation2001; Freeman and Crawford Citation2008; Turner and Celedón-Pattichis Citation2011). It is relevant to mention that Syrian refugee children who arrive in the Netherlands at a later age mainly receive Dutch language lessons upon arrival. This creates a gap between their levels in content-based subjects and those of their monolingual Dutch peers who receive regular schooling. Such a growing gap may adversely affect the academic levels of those emergent bilingual young students and subsequently influence their educational career. Therefore, simultaneously while receiving the Dutch language lessons, a usage of students’ dominant languages in classrooms of refugee students for teaching as well as assessing should be considered when dealing with content based-subjects (Cummins and Takeuchi Citation2019; Lee Citation2005; Kersaint, Thompson, and Petkova Citation2009; Shaw Citation1997). Among others, Reljić, Ferring, and Martin (Citation2015) showed, in their results of a meta-analytic study, that there is a positive effect for bilingual education supporting the home language use of children in school instructions. This confers a two-fold advantage. On the one hand, it can help avoid the difficulty that arises from learning content-based subjects though a yet-unmastered language of instruction (Kempert, Saalbach, and Hardy Citation2011) and, on the other hand, it can contribute to a better achievement and an equitable assessment in exams.

The second purpose of the present study was to examine the utility of consulting parents of refugee students and considering involving them in the assessment process. Specifically, it was examined whether parents can give a credible assessment of their children’s mathematical skills and whether their assessment would concur more with the Arabic version of the test than with the Dutch version. To test that, parents filled in a questionnaire in which they rated their children’s mathematical skills on a five-point Likert scale using the five-question items. In line with previous studies that showed that parents can give an authentic assessment of the language development of their children (Bedore et al. Citation2011; Boerma and Blom Citation2017), results in this study indicated that parents were able to give an accurate assessment of their children’s skills in mathematics. Their assessment significantly correlated with the scores of their children in mathematics in both versions. Better abilities according to parental assessment correlated with higher scores on the mathematics test.

However, a higher rating by the parents was also correlated with a relatively higher performance on the Dutch version of the test. This somewhat unexpected finding may indicate that although the Dutch version underestimated the children's mathematics abilities, it did reflect relative differences between children. Correspondingly, a child who scored relatively high on the Arabic version also scored relatively high on the Dutch version. Consequently, participants who were assessed more highly by their parents also performed better on the Dutch version of the test than those who received a lower parental assessment. This result shows that parents’ answers correlated with the level of their children in mathematics indicating that parents were aware of the actual cognitive competence of their children in mathematics irrespective of the testing language.

This study has implications for teachers who work with refugee students. The results of the study show that parental questionnaires may be highly effective with regard to the evaluation of the students’ levels in mathematics, and suggest that building bridges between parents and teachers is essential in supporting the education of refugee students. It is pivotal to use the dominant language of the refugee children’s parents (Derluyn and Broekaert Citation2007). We are aware that this creates a language barrier for many teachers who do not speak or understand this language. Involving interpreters from the community who are proficient in both the language of the school and the parents’ dominant languages may help to support this strategy.

Limitations and future research

For the purpose of the current study, we used a within-subjects design in order to compare the results of assessment in different languages within one and the same bilingual individual. The sample in our study was relatively small and did not allow us to delve deeper into relationships between mathematics abilities and factors related to the more specific experiences of refugees. There was, for example, substantial variation in children’s schooling before arriving in the Netherlands (SI, SO). Future research with a larger sample of children can take educational history into consideration and group participants according to their educational history. Other sources of individual differences in the heterogeneous population of refugee students that could be of interest are length of residence, age, and traumatic experiences. In addition, due to the time limitations, we were unable to assess the children’s language proficiency in Arabic and Dutch, hence, we could not perform analyses to directly investigate relationships between children’s performance on the mathematics assessments in Arabic and Dutch and their proficiency in these languages. We recommend this as a venue for future research. Finally, future research can also investigate the effect of the language on the performance of students who reside longer than five years in the hosting country and examines whether the language effect decreases.

Conclusions

This study shows that the school language is an influencing factor on the mathematics assessment of refugee student and that the cognitive abilities of these students may be hidden when assessed in the school language only. This conclusion invites teachers and educational policy makers to realize that assessing emergent bilingual students in the school language adhering to a monolingual norm is an inequitable practice. Using the dominant language of emergent bilinguals could in such cases be a solution to disentangle a temporary problem linked to language proficiency in the language of schooling from low achievement caused by the lack of knowledge in the content of the assessment. Moreover, our study shows that the parents of refugee students are aware of the mathematics level of their children indicating that the parents’ involvement in the assessment process may be a valuable source of information for teachers and a step towards more equitable practices in the assessment of refugee students and emergent bilingual students in general.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zahraa Attar

Zahraa Attar obtained her master’s degree from Utrecht University (research master Linguistics) in 2018. Currently, she is affiliated with the university as a guest researcher and works as a trainee at the Young Professionals Program for status holders at the municipality of Amsterdam. She works as a trainee policy advisor at the department of Education and aims through her research and work to contribute to equal chances in education for children with refugee and bilingual backgrounds.

Elma Blom

Elma Blom is Professor in Language Development and Multilingualism in family and educational contexts at the Department of Education and Pedagogy at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and is affiliated to The Arctic University of Norway UiT. Her research and publications are about language impairment, multilingual development and the relationship between language development and children’s domain-general cognitive abilities. Besides theoretical issues, she works on the improvement of diagnostic instruments for multilingual children.

Emmanuelle Le Pichon

Emmanuelle Le Pichon is Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and head of the Centre de Recherches en Éducation Franco-Ontarienne (CRÉFO). Her research focusses on issues related to multilingual education, particularly on the education of students with a minority background.

References

- Abedi, J., and C. Lord. 2001. “The Language Factor in Mathematics Tests.” Applied Measurement in Education 14 (3): 219–234. doi: 10.1207/S15324818AME1403_2

- Bates, D., M. Maechler, B. Bolker, and B. Walker. 2015. “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4.” Journal of Statistical Software 67 (1): 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Bedore, L. M., E. D. Peña, D. Joyner, and C. Macken. 2011. “Parent and Teacher Rating of Bilingual Language Proficiency and Language Development Concerns.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 14 (5): 489–511. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2010.529102

- Boerma, T., and E. Blom. 2017. “Assessment of Bilingual Children: What if Testing Both Languages is not Possible?” Journal of Communication Disorders 66: 65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2017.04.001

- Browder, C. T. 2018. “Recently Resettled Refugee Students Learning English in US High Schools: The Impact of Students’ Educational Backgrounds.” Educating Refugee-Background Students, 17–32. doi: 10.21832/9781783099986-006

- Cummins , J. 2001. “Bilingual Children's Mother Tongue: Why Is It Important for Education? .” Sprogforum 7(19): 15–20.

- Cummins, J., and M. Takeuchi. 2019. “Teaching Mathematics to English Language Learners Across the Curriculum.” In My Best Idea, Math (Vol. 1), edited by M. Sack, 92–103. Oakville, ON: Rubicon Press.

- Cunnings, I. 2012. “An Overview of Mixed-Effects Statistical Models for Second Language Researchers.” Second Language Research 28 (3): 369–382. doi: 10.1177/0267658312443651

- Derluyn, I., and E. Broekaert. 2007. “Different Perspectives on Emotional and Behavioural Problems in Unaccompanied Refugee Children and Adolescents.” Ethnicity and Health 12 (2): 141–162. doi: 10.1080/13557850601002296

- Dryden-Peterson, S. 2015. The Educational Experiences of Refugee Children in Countries of First Asylum. British Columbia Teachers’ Federation.

- Europe-Perae, I. N. (2018). SIRIUS-Policy Network on Migrant Education.” Accessed May 21 2020. http://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PERAE_Comparative-Report-1.pdf

- European Commission (2017). Country Report Netherlands: Commission Staff Working Document COM(2017). Publications Office of the European Union (Issue brief No. No 1176/2011). Luxembourg.

- Feinberg, R. C. 2000. “Newcomer Schools: Salvation or Segregated Oblivion for Immigrant Students?” Theory Into Practice 39 (4): 220–227. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3904_5

- Fraine, N., and R. McDade. 2009. “Reducing Bias in Psychometric Assessment of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students From Refugee Backgrounds in Australian Schools: A Process Approach.” Australian Psychologist 44 (1): 16–26. doi: 10.1080/00050060802582026

- Fredman, M., and J. Centeno. 2006. “Recommendations for Working with Bilingual Children—Prepared by the Multilingual Affairs Committee of IALP.” Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica 58 (6): 458–464.

- Freeman, B., and L. Crawford. 2008. “Creating a Middle School Mathematics Curriculum for English-Language Learners.” Remedial and Special Education 29 (1): 9–19. doi: 10.1177/0741932507309717

- García, O., and J. A. Kleifgen. 2010. Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Language Learners. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gogolin, I. 2011. “The Challenge of Super Diversity for Education in Europe.” Education Inquiry 2 (2): 239–249. doi: 10.3402/edui.v2i2.21976

- Gorter, D., and J. Cenoz. 2017. “Language Education Policy and Multilingual Assessment.” Language and Education, 31 (3): 231–248. doi: 10.1080/09500782.2016.1261892

- Herzog-Punzenberger, B., E. M. M. Le Pichon, and H. Siarova. 2017. Multilingual Education in the Light of Diversity: Lessons Learned. Publications Office of the European Union.

- International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics (IALP). 2011. “ Recommendations for Working with Bilingual Children.” http://www.linguistics.ualberta.ca/en/CHESL_Centre/?/media/linguistics/Media/CHESL/Documents/WorkingWithBilingualChildren-May2011.pdf.

- Kempert, S., H. Saalbach, and I. Hardy. 2011. “Cognitive Benefits and Costs of Bilingualism in Elementary School Students: The Case of Mathematical Word Problems.” Journal of Educational Psychology 103 (3): 547. doi: 10.1037/a0023619

- Kersaint, G., D. R. Thompson, and M. Petkova. 2009. Teaching Mathematics to English Language Learners. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kids4cito. n.d. Accessed March 21 2018. http://www.kids4cito.nl/.

- Klingner, J., and A. J. Artiles. 2006. “English Language Learners Struggling to Learn to Read: Emergent Scholarship on Linguistic Differences and Learning Disabilities.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 39 (5): 386–389. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390050101

- Kohnert, K. 2010. “Bilingual Children with Primary Language Impairment: Issues, Evidence and Implications for Clinical Actions.” Journal of Communication Disorders 43 (6): 456–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.02.002

- Kuznetsova, A., P. B. Brockhoff, and R. H. B. Christensen. 2017. “lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 82 (13): 1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13

- Lee, O. 2005. “Science Education with English Language Learners: Synthesis and Research Agenda.” Review of Educational Research 75 (4): 491–530. doi: 10.3102/00346543075004491

- Le Pichon, E. 2020. “Intercultural Communication in the Context of Hypermobility of School Population in and out Europe.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Intercultural Communication, edited by G. Rings and S. M. Rasinger, 367–382. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Le Pichon, E., and E. R. Kambel. 2016. “Challenges of Mathematics Education in a Multilingual Post-Colonial Context: The Case of Suriname.” In human Rights in Language and STEM Education, 221–240. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

- Lustig, S. L. 2010. “An Ecological Framework for the Refugee Experience: What is the Impact on Child Development?” In Chaos and its Influence on Children’s Development: An Ecological Perspective, edited by G. W. Evans and T. D. Wachs, 239–251. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Operational Portal. n.d. Accessed March 29, 2019. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria.

- Räty, H., J. Vänskä, K. Kasanen, and R. Kärkkäinen. 2002. “Parents’ Explanations of Their Child's Performance in Mathematics and Reading: A Replication and Extension of Yee and Eccles.” Sex Roles 46 (3-4): 121–128. doi: 10.1023/A:1016573627828

- R Core Team. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Reljić, G., D. Ferring, and R. Martin. 2015. “A Meta-Analysis on the Effectiveness of Bilingual Programs in Europe.” Review of Educational Research 85 (1): 92–128. doi: 10.3102/0034654314548514

- Revelle, W. (2018). psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. Evanston, ILL: Northwestern University. https://CRAN.R project.org/package = psych Version = 1.8.4.

- Ruhose, J., and G. Schwerdt. 2016. “Does Early Educational Tracking Increase Migrant-Native Achievement Gaps? Differences-in-Differences Evidence Across Countries.” Economics of Education Review 52: 134–154. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.02.004

- Schneider, C., and M. Arnot. 2018. “Transactional School-Home-School Communication: Addressing the Mismatches Between Migrant Parents' and Teachers' Views of Parental Knowledge, Engagement and the Barriers to Engagement.” Teaching and Teacher Education 75: 10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.05.005

- Shapira, M. 2012. “An Exploration of Differences in Mathematics Attainment among Immigrant Pupils in 18 OECD Countries.” European Educational Research Journal 11 (1): 68–95. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2012.11.1.68

- Shapiro, S., R. Farrelly, and M. J. Curry. 2018. Educating Refugee-Background Students: Critical Issues and Dynamic Contexts. Multilingual Matters.

- Shaw, J. M. 1997. “Threats to the Validity of Science Performance Assessments for English Language Learners.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 34 (7): 721–743. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199709)34:7<721::AID-TEA4>3.0.CO;2-O

- Sheldon, S. B., and J. L. Epstein. 2005. “Involvement Counts: Family and Community Partnerships and Mathematics Achievement.” The Journal of Educational Research 98 (4): 196–207. doi: 10.3200/JOER.98.4.196-207

- Shohamy, E. 2011. “Assessing Multilingual Competencies: Adopting Construct Valid Assessment Policies.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 418–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01210.x

- Solano-Flores, G., and S. Nelson-Barber. 2001. “On the Cultural Validity of Science Assessments.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 38 (5): 553–573. doi: 10.1002/tea.1018

- Solano-Flores, G., and E. Trumbull. 2003. “Examining Language in Context: The Need for new Research and Practice Paradigms in the Testing of English-Language Learners.” Educational Researcher 32 (2): 3–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032002003

- Tudjman, T., A. van den Heerik, E. Le Pichon, and S. Baauw. 2016. Multi-country Partnership to Enhance the Education of Refugee and Asylum-Seeking Youth in Europe: Refugee Education in the Netherlands. Risbo: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- Turner, E., and E. Celedón-Pattichis. 2011. “Mathematical Problem Solving Among Latina/o Kindergartners: An Analysis of Opportunities to Learn.” Journal of Latinos and Education 10 (2): 146–169. doi: 10.1080/15348431.2011.556524

- Unicef.org. 2019. " Latest Statistics and Graphics on Refugee and Migrant Children." Accessed May 21, 2020 from, https://www.unicef.org/eca/emergencies/latest-statistics-and-graphics-refugee-and-migrant-children.

- Winter, B. 2013. Linear models and linear mixed effects models in R: Tutorial 1. http://www.bodowinter.com/tutorial/bw_LME_tutorial1.pdf.

- Yee, D. K., and J. S. Eccles. 1988. “Parent Perceptions and Attributions for Children's Math Achievement.” Sex Roles 19 (5–6): 317–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00289840

Appendix

Questionnaire

Thank you for participating in this research:

At Utrecht University, we are doing research on the effect of language on the performance of Syrian children in mathematics. Your answers will help to get the data needed for the research. I am assistant- researcher on this research.

Personal information:

Please answer the following questions

1. What is the date of your child’s arrival to the Netherlands?

(day/month/year) ( / / )

2. What is the name of your child?

_____________________________________________________

3. What is the date of birth of your child?

(day/month/year) ( / / )

4. Did your child live in Syria? Please encircle the appropriate answer

Yes

No

5. What is the highest level of education of the father? Please encircle the appropriate answer

Primary school

Middle school

Secondary school

University level

Master degree

Other:_____________

6. What is the highest level of education of the mother? Please encircle the appropriate answer

Primary school

Middle school

Secondary school

University level

Other:_____________

7. Did your child live in one of more refugee camps on the borders of Syria?

1. Yes for _________ years from (day/ month/ year to day/ month/ year)

2. No

Language biography:

8. Did your child go to school in Syria? If yes, how long?

3. Yes for _________ years from (day/ month/ year to day/ month/ year)

1. No

Additional details:

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

9. Did your child live outside Syria before coming to the Netherlands? Please encircle.

Yes

No

10. Did your child go to school in countries other than Syria? (If applicable)

Yes

No

Assessment questions:

Please answer the questions by choosing the appropriate number.

1 = strongly agree

2 = agree

3 = neither agree nor disagree

4 = disagree

5 = strongly disagree