ABSTRACT

This article carries out a cross-European comparison of stakeholder perspectives on catering to diversity within CLIL programs. It reports on a cross-sectional concurrent triangulation mixed methods study with 2,526 teachers, students, and parents in 59 Secondary schools in six European countries: Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. It employs data, methodological, and location triangulation and carries out across-cohort comparisons in order to determine the differences/similarities which can be discerned between the measures implemented in northern, central, and southern Europe to make bilingual education a more inclusive reality for all. It also provides comparative insights into the main difficulties and chief training needs which still need to be addressed. The broader take-away is that CLIL provision, as it stands, does not fit the bill in the new mainstreaming scenario and needs to be reengineered to respond to the needs posed by educational differentiation. This pan-European outlook will allow us to determine where we currently stand on this issue and to showcase the main lessons which can be gleaned from different contexts in order to step up to one of the most important challenges facing bilingual education in Europe (and beyond) if we seek to ensure its sustainability.

Introduction

The charge of elitism, segregation, and discrimination has plagued Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) for well over a decade (Bruton Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2019; Paran Citation2013) and is a topic of increasing currency in today’s bilingual education agenda (Gortázar and Taberner Citation2020). While it is true that CLIL programs wrestled with problems of exclusive gatekeeping at the outset of their implementation through self-selection (Lorenzo, Casal, and Moore Citation2009) and the establishment of admission criteria based on students’ subject knowledge, target language level, or both (Dallinger, Jonkmann, and Hollm Citation2018), at present they are increasingly being mainstreamed school-wide (Junta de Andalucía Citation2017) and offering a greater range of students opportunities for linguistic development which they were previously denied. As Barrios Espinosa (Citation2019, 5) has put it, ‘bilingual education has officially been advocated as an instrument of social cohesion since it is aimed to facilitate the whole population access to quality education in foreign languages that was formerly the prerogative of the elite’.

In this new scenario, the topic of diversity and inclusion has, not surprisingly, garnered heightened attention. Indeed, some of the latest research (Anghel, Cabrales, and Carro Citation2016; Fernández-Sanjurjo, Fernández-Costales, and Arias Blanco Citation2019) has pointed to the fact that this novel model of mainstreaming is not only a huge challenge which entails an increased difficulty, but it could seriously jeopardize everything achieved so far in bilingual programs. Concomitantly, however, an increasing body of empirically robust research (Ainsworth and Shepherd Citation2017; Madrid and Barrios Citation2018; Pavón Vázquez Citation2018; Rascón Moreno and Bretones Callejas Citation2018; Pérez Cañado Citation2020a) is evincing that the tables are turning and tendencies are shifting. In this sense, the self-selection in CLIL groups which was operative in the initial implementation phase of these programs now appears to be obsolete. The most intelligent, motivated, and linguistically proficient students are no longer in the CLIL groups and CLIL and non-CLIL classes are increasingly homogenous on all these fronts (Pérez Cañado Citation2020b). In addition, CLIL programs seem to be canceling out differences in setting, socioeconomic status (SES), and type of school, as they are far less substantial than in non-bilingual classes. CLIL is thus leveling the playing field (Ainsworth and Shepherd Citation2017; Madrid and Barrios Citation2018; Pavón Vázquez Citation2018; Rascón Moreno and Bretones Callejas Citation2018). Finally, CLIL has been found to have the potential to work even in the most disenfranchised settings, in rural contexts, public schools, with minority groups and parents with low SES, provided it is implemented adequately (Pérez Cañado Citation2020a).

Irrespective of the camp with which these studies side, there is a consensus that one of the greatest problems plaguing CLIL implementation at present is catering for diversity, as there is conspicuous lack of materials, resources, methodological and evaluative guidelines, and teacher education endeavors to step up to it successfully (Pérez Cañado Citation2018). Indeed, as stated by Bauer-Marschallinger et al. (Citation2021), little scholarly attention has been paid to pedagogical practices to attend to linguistically and academically diverse learners in the CLIL classroom. Thus, prior investigation documents the urgent need for a study on attention to diversity within CLIL in order to shed light on the issue of whether and how CLIL works across different levels of attainment and what types of curricular and organizational practices can be implemented to cater for it.

This is precisely the niche which the present article seeks to fill. It reports on a cross-sectional concurrent triangulation mixed methods study (Creswell Citation2013) which is distinctive on many levels. To begin with, it factors in stakeholders’ self-reported perceptions, a particularly relevant remit in our field:

“However, some areas of CLIL remain in need of further exploration. One such area is that of stakeholders’ perceptions of CLIL, the interest of which lies in the fact that their interpretations and beliefs are crucial to understand how the CLIL programme is socially viewed, understood and constructed, and the expectations it raises”. (Barrios Espinosa Citation2019, 1)

The theoretical backdrop: prior research into attention to diversity in CLIL

The exploration of the pedagogical practices and teacher development options focusing on catering for different levels of ability in CLIL contexts has hitherto received little scholarly attention and uncertainty still surrounds the suitability of this approach for all types of achievers. Indeed, two main types of publications can be discerned on the topic: theoretical approximations or reviews of existing research/guidelines and qualitative investigations on stakeholder perspectives which have centered on the topic only indirectly or in passing.

Within the former category, an initial batch of publications provides essentially theoretical accounts which canvass the different lines of action which can be set in place within CLIL programs to cater to diversity. Madrid and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018) offer an overview of the main strategies mentioned in the specialized literature for this purpose. They include splitting the class into small flexible groupings with mixed abilities, providing linguistic and academic scaffolding to help students construct subject-specific knowledge, or offering curricular adaptations (through changes in objectives, content, assessment, or activities). Three further guidelines include deploying student-centered methodologies (such as Multiple Intelligence Theory, Cooperative Learning, Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), or Project-Based Learning (PBL)), favoring a variety of classroom organizations which allow for same and mixed-ability groupings, and making use of multimodal materials and ICTs with different types of input. Finally, the teacher is also instrumental: maximizing teacher-student rapport and providing extra support by including a second teacher in the classroom also come to the fore as successful ways to promote educational differentiation. In this sense, Scanlan (Citation2011) and Cioè-Peña (Citation2017) incide on the role of the teacher and on the importance of his/her training, which needs to be bolstered in order to ensure the success of linguistically and academically diverse students. It is essential for teachers to be equipped with the relevant knowledge and skills in order to provide culturally and linguistically informed learning opportunities for diverse learners. Finally, Scanlan (Citation2011) and Grieve and Haining (Citation2011) also document the effort which needs to be made to increase the home-school liaison with parents in order to create a robust multi-tiered support system in schools.

Other publications have reviewed existing guidelines or research. Martín-Pastor and Durán Martínez (Citation2018), for instance, have canvased the measures to attend to diversity included in the official policy documents of 60 Primary schools in the Spanish monolingual context. The onus here has been essentially on two main techniques: making the curriculum more flexible and establishing individual reinforcement activities. However, worryingly, three of the most oft-cited options to cope with diverse ability learners include encouraging children with difficulties to transfer out of the program, separating learners out into CLIL (with the most successful ones) and non-CLIL (with the most disadvantaged students) streams, or resorting to the L1 to explain contents, all of which contravene the principle of inclusion (cf. the DIDI framework in the introductory article of this issue). The authors also document a rift between the policy reflected in the afore-mentioned documents and actual grassroots practice: it is not truly clear whether theory is actually trickling down to on-the-ground practice, something which, they claim, should be the remit of further investigations.

A prettier picture is painted by Somers' (Citation2017, Citation2018) review of research on immigrant minority language students in Content and Language Integrated Learning programs. CLIL comes across as a pluralistic, language-rich approach to education which offers immigrant minority language students effective pedagogical support through scaffolding and language-sensitive instructional strategies such as frequent use of visual aids, gestures, or reformulation. This causes the CLIL classroom to become ‘an empowering environment for all students’ (Somers Citation2018, 220), as it offers these learners opportunities and support not present in majority language classrooms.

In turn, a second set of studies are qualitative endeavors which have monitored stakeholder perceptions of the way in which CLIL programs are working and of the main teacher training needs they are generating. They have culled the opinions of key players in CLIL settings (e.g. students, teachers, parents, coordinators, principals, or vice-principals), employing a qualitative methodology and instruments including interviews, questionnaires, or observation. These studies have only peripherally and indirectly focused on the topic under scrutiny: none have explored it in a full-fledged manner as the chief remit of the investigation.

Only six studies can be detected where the topic of attention to diversity comes to the fore. In Northern Europe, Mehisto and Asser (Citation2007) work with 180 parents, 41 teachers, four principals, and four vice-principals participating in Russian CLIL programs in Estonia to determine their outlook on issues related to the program management. Although the chief focus of their study is not on catering to diversity in CLIL, their investigation does allow them to ascertain that attention to diversity transpires as one of the key challenges for the practitioners involved. These authors (2007, 693) conclude that

“addressing the needs of students who lack motivation, pose discipline problems or are academically weak is a challenge for the program at large and requires an organisational response both to help ensure that students’ needs are met and that teachers build their repertoire of related skills”.

Also in northern Europe, concretely in Finland, Roiha (Citation2014) delves into the differentiation methods which Primary teachers use in CLIL education and the most outstanding challenges of differentiation which they identify. A qualitative case study with three teachers is reported on. The most common methods used for differentiation (involving attending to both underachieving and gifted pupils) include providing extensive visual and oral support during teacher explanations, allowing pupils to use the L1 (Finnish), making use of peer support, discussing issues together with the whole class, and flexible groupings. Offering more extensive and personalized written feedback to pupils with special needs, assigning different homework for different students, and informing learners about the topic of the CLIL lesson in advance are also frequently employed techniques. In turn, the chief challenges identified by the three teachers are the lack of time and resources, scarcity of materials, and large class sizes, together with lack of school assistants or of opportunities to practice co-teaching.

In Spain, the research group led by Ana Halbach at the University of Alcalá de Henares has also carried out interesting qualitative studies where the topic has equally surfaced. Pena Díaz and Porto Requejo (Citation2008) probe teacher opinions in the community of Madrid through two questionnaires. Practitioners document difficulties rooted in materials and resources to face up to the challenge of coping with special needs students within bilingual programs, whose desirability is thus questioned. More recently, Fernández and Halbach (Citation2011) poll 56 teachers in 15 schools using questionnaires. The outcomes of this latest study dovetail with those of previous ones in the insufficient resources and problems with mixed ability groups, special needs students, and latecomers to the program.

Finally, at the University of Jaén, the NALTT Project (EA2010-0087) led by Pérez Cañado worked with 706 pre- and in-service teachers, teacher trainers, and coordinators across the whole of Europe and determined that, among the main CLIL teacher training needs, adequate materials design and methodological guidelines for catering to diversity figured prominently as lacunae to be addressed (Pérez Cañado Citation2016b, Citation2016c). More recently, the MON-CLIL Project (FFI2012-32221 and P12-HUM-2348), also spearheaded by this researcher, has polled 2,633 teachers, students, and parents in three monolingual communities in Spain (Pérez Cañado Citation2018) and conspicuous lacunae still surface regarding the scarcity of materials to attend to diversity. In line with the foregoing, this author concludes that

‘The greatest problems plaguing CLIL implementation … affect catering to diversity, increased parental support and empowerment, and enhanced training for non-linguistic area teachers. These niches should figure prominently on the future CLIL agenda, as they could otherwise jeopardize the effectiveness of dual-focused programs … ’ (Pérez Cañado Citation2018, 388).

Thus, this overview of prior research allows us to derive two overarching conclusions. First and foremost, it has enabled us to ascertain that the extremely meager –verging on non-existent- amount of research which has thus far tackled head-on the issue of attention to diversity in CLIL programs. And secondly, it has revealed that there is no evidence of whether or how the strategies and techniques canvassed in the specialized literature hitherto are being practically implemented at the grassroots level, according to the chief stakeholders involved. These are precisely the two aspects which the study presented below seeks to address. It examines, for the first time and in a full-blown way, the resources, materials, classroom organization, methodologies, or types of evaluation which are being deployed to cater to diversity within CLIL schemes and the main teacher training needs in this area. It polls 2,526 teachers, students, and parents and employs data, methodological, and location triangulation in order to determine the differences and similarities which can be discerned between the measures implemented in northern, central, and southern Europe to make bilingual education a more inclusive reality for all. It also provides comparative insights into the main difficulties that teachers are facing in this arena and the main training needs which still need to be addressed, showcasing the main lessons which can be gleaned from different contexts in order to step up to one of the most important challenges facing bilingual education in Europe (and beyond) if we seek to ensure its sustainability.

The study

Objectives

The broad objective of this investigation is to conduct a large-scale CLIL program evaluation of stakeholder perspectives on the current mise-en-scène of attention to diversity in CLIL programs. It canvasses teacher, student, and parent perceptions of the way in which CLIL methodology, types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher collaboration and development are being deployed to cater for different abilities among CLIL students in six European countries. The study is driven by two key metaconcerns, which are broken down into the following component corollaries:

Metaconcern 1 (Program evaluation)

To determine teacher perceptions of the way in which catering to diversity is being approached within CLIL programs (in terms of linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher collaboration) and of the main teacher training needs in this area.

To determine student perceptions of the way in which catering to diversity is being approached within CLIL programs (in terms of linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher collaboration and development) at Secondary Education level.

To determine parent perceptions of the way in which catering to diversity is being approached within CLIL programs (in terms of linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher collaboration and development) at Secondary Education level.

Metaconcern 2 (Across-cohort comparison)

To determine if there are statistically significant differences vis-à-vis linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher collaboration and development among the perceptions of the three cohorts: teachers, students, and parents.

Research design

The present investigation is an instance of primary, survey research, since it employs interviews and questionnaires (Brown Citation2001). According to this author, it is mid-way between qualitative and statistical research, as it can make use of both these techniques. In addition, it incorporates multiple triangulation (Denzin Citation1970), concretely, of the following four types:

Data triangulation, as diverse groups of stakeholders with different roles in the language teaching context have been polled: students, parents, and teachers (and within the latter, non-linguistic area teachers, English language teachers, and teaching assistants).

Methodological triangulation, since a variety of instruments has been employed to gather the data: questionnaires, interviews, and observation (although only the results pertaining to the questionnaires will be reported on herein).

Investigator triangulation, due to the fact that different researchers have analyzed the open data in the questionnaire and interviews, identified salient themes, and collated their findings.

Location triangulation, given that stakeholder opinions have been culled from multiple data-gathering sites: 59 Secondary schools in six European countries.

Sample

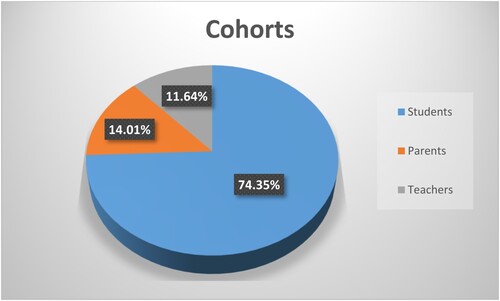

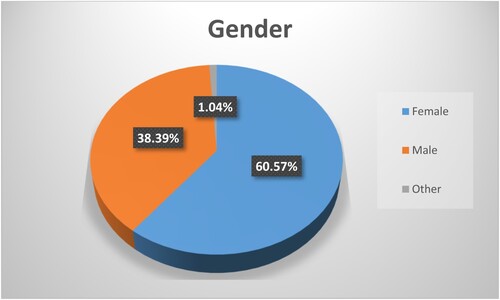

The project has worked with a substantial cohort of students, teachers, and parents in Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. The return rate has been significant, as the surveys have been administered to a total of 2,526 informants. The most numerous cohort has been that of students (with 1,878 participants), followed by parents (354 in all) and teachers (294) (cf. Graph 1). In terms of gender, women (60.57%) outnumber their male counterparts (38.39%) (cf. Graph 2).

The bulk of the students are from Spain (39.5%) and Germany (31.8%), followed by the UK (8.9%), Italy (6.9%), Austria (7%), and Finland (5.8%). The majority are from 12 to 16 years old, with 13–15 being the dominant age bracket. The female students (57.9%) outnumber their male (41.2%) counterparts and most have studied for less than five years in a bilingual program (3-4 years mainly).

As had been the case with the students, most of the respondents within the teacher cohort are from Spain (61.6%), followed, in this case, by Austria (17%), Germany (10.5%), Finland (5.1%), the UK (3.1%), and Italy (2.7%). There are, again, more female (60.8%) than male (37.2%) practitioners, and most are in the 36–45 age bracket. Roughly equal percentages of content (45.3%) and language (47.8%) teachers can be ascertained, with language assistants amounting only to a 1.2%. They are mostly civil servants with a stable job at their high schools and have mainly a B2 (35.3%), C2 (28.8%), or C1 (24%) level of the target language. The majority of the practitioners polled have 11–20 years of overall teaching experience (38.8%), but only 1–5 years (42.9%) or 6–10 years (28.9%) in a bilingual school.

Finally, the breakdown of the parent cohort evinces that they are, once more, primarily from Spain (65.8%), followed by Germany (12.4%), Austria (11.8%), and Finland (10%). The tendency observed in terms of gender for the other two cohorts is further reinforced in this one, with 74.6% of respondents being mothers and only 24.5%, fathers. A final noteworthy trait of this sample is that most parents have a high socioeconomic status (54.6%), with the predominant level of studies thus being a University Degree or Doctorate.

Variables

The study has worked with a series of identification (subject) variables, connected to the individual traits of the three different stakeholders who have been polled through the questionnaire and interview.

The identification variables for each cohort are specified below:

Teachers

Grade

Age

Gender

Country

Type of teacher

Employment situation

Level in the FL taught

Overall teaching experience

Teaching experience in a bilingual school

Students

Grade

Class

Age

Gender

Country

Language(s) spoken at home

Years in a bilingual program

Amount of exposure to English within the bilingual program

Parents

Country

Grade of child

Age

Gender

Language(s) spoken at home

Level of education

Instruments

The study has employed self-administered and group-administered questionnaires, categorized by Brown (Citation2001) as survey tools, to carry out the targeted program evaluation. Three sets of questionnaires (one for each of the cohorts) have been designed and validated in English, Spanish, German, Italian, and Finnish. A double-fold pilot procedure has been followed in editing and validating the questionnaires, which has entailed, firstly, the expert ratings approach (with 30 external evaluators from Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Education) and, subsequently, a pilot phase with a representative sample of respondents (234 informants with the same features as the target respondents). Extremely high Cronbach alpha coefficients have been obtained for the three questionnaires: 0.871 for the student one, 0.858 for the teacher equivalent, and 0.940 for the parent survey (cf. Pérez Cañado, Rascón Moreno, and Cueva López Citation2021 for a detailed rendering of the design and validation of the questionnaires and for access to the final versions for each of the three cohorts).

Data analysis: statistical methodology

The data obtained on the questionnaires has been analyzed statistically, using the SPSS program in its 25.0 version. Descriptive statistics have been used to report on the results obtained for metaconcern 1 (objectives 1–3). Both central tendency (mean, median and mode) and dispersion measures (range, low-high, standard deviation) have been calculated. In turn, for metaconcern 2 (objective 4), assessment of normality and homoscedasticity has been carried out via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene’s test, respectively. In those cases where non-parametric tests have been necessary (across-cohort comparisons) the Kruskal–Wallis test has been run, the Mann–Whitney U test has been employed for post-hoc analysis, and effect sizes have been calculated as Rosenthal’s r.

Results and discussion

Perspectives on attention to diversity in CLIL by cohort

Teachers: global analysis

In line with the first metaconcern (objectives 1-3), our study has allowed us to paint a comprehensive picture of teacher, student, and parent perspectives à propos the way in which catering to diversity is being approached within CLIL programs. For the teacher cohort, it transpires that, in general, they find it challenging to teach CLIL classes with different levels of ability both in the foreign language (m = 4.40) and academic content (m = 4.31). To undertake this complex task, the most oft-used technique is scaffolding (both linguistic –m = 4.42- and content-related –m = 4.44). This chimes with Somers' (Citation2017, Citation2018) findings, according to which offering pedagogical support through scaffolding is present in CLIL classrooms to accommodate minority students’ needs. It also accords with the best practices which the teachers were asked to relay in the final section of the questionnaire: scaffolding and student-centered methodologies come across as the most conspicuous ones they would highlight. Teachers resort, however, to repetition in the L1 to a much lesser extent (m = 4.10). Their level of confidence with their specialized academic language (m = 5.12) and communication skills in the target language (m = 4.97) is very self-complacent. They clearly feel equipped to grapple with different levels of ability in the CLIL classroom on these fronts.

As regards methodology, the outcomes reveal that student-centeredness is firmly embedded in CLIL classrooms across the continent in order to cater for students with differing abilities (again, in line with the best practices outlined at the end of the survey). Indeed, the teachers feel they have an adequate repertoire of methods at their disposal to step up to this important challenge and consider their teaching is primarily focused on the student (m = 4.48), as opposed to teacher-led (m = 3.18). They feel they readily incorporate student-centered options such as Cooperative Learning principles (m = 4.27) or Task- and Project-Based Learning (m = 4.32). They also consider they provide personalized attention individually and in smaller groups (m = 4.52) and use peer mentoring and assistance strategies (m = 4.51) to quite a large extent. Mixed ability groups (m = 4.13) are comparatively less exploited, as are multiple intelligences (m = 3.90), different classroom layouts (m = 3.82), and newcomer classes to support the integration of learners (m = 2.68), which are the lowest-ranking item, as they barely seem to exist. Teachers also appear to experience issues with CLIL lesson design to cater for students with different abilities (m = 3.55), so greater guidance on this score would be necessary. The ADiBE Project has in fact designed a teacher training course with a three-pronged structure precisely to guide teachers from more controlled to freer practice, until they can design their own units for this purpose (cf. introductory article).

The picture which transpires for the section on materials and resources is much more negative: teachers do not have access to adequate ones that already factor in different levels of ability among students (m =3.57) and they have to resort to adapting and creating their own materials (m = 4.47 and 4.59, respectively), a task they find quite daunting (m =3.58). This is consistent with the outcomes of the majority of prior studies into the topic (Pena Díaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008; Fernández and Halbach Citation2011; Roiha Citation2014; Pérez Cañado Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2018), which have signposted the scarcity of materials as one of the major roadblocks to successful differentiation in CLIL. It is also in line with the top challenge underscored by the teachers polled at the end of the questionnaire: lack of access of materials is the highest ranked hurdle. A combination of different types of input is employed to cater for different abilities (m = 4.56) and ICTs are found particularly useful to face up to this challenge successfully (m = 4.70).

A more positive outlook can be gleaned for assessment: teachers have a greater penchant for optimism here vis-à-vis their use of formative (m = 4.53) and summative (m = 4.38) evaluation techniques to cater for different ability levels. However, when we delve deeper into the actual techniques they employ, more lukewarm responses ensue. In this sense, providing different versions of an exam, allowing more time to take it (m = 3.71), highlighting key words, adapting vocabulary for different levels in the test (m = 3.98), or providing different types of homework according to ability (m = 3.93) are not normally incorporated as assessment procedures. Grading criteria are also not adapted to cater for diverse types of students (m = 3.85). Formative assessment techniques are deployed to a slightly greater extent, albeit not a substantial one, including providing personalized and regular feedback attuned to diverse ability levels (m = 4.31), using self-assessment (m = 4.31), adapting activities to different levels (m = 4.23), or providing detailed guidelines as extra support in formative evaluation (m = 4.21). This accords with the findings of Roiha (Citation2014), where precisely formative assessment strategies came across as particularly useful. It also points to the fact that catering for diversity in summative evaluation needs to be substantially stepped up in the CLIL classroom, as the teachers themselves signpost when ranking the greatest challenges at the end of the questionnaire.

What is this cohort’s view as regards the support systems which are in place to cater for diversity? To begin with, the support of multi-professional teams (m = 4.62) and of the guidance counselor (m = 4.82) are regarded as essential. They appear to be present in the participating schools and to have a very important role to play within them. Coordination and collaboration with other colleagues (m = 4.39) and with parents (m = 4.28) are only moderately operative and the greatest deficiencies are detected with the overall school support system (m = 3.86) and with the preparation of language assistants (m = 3.87), which does not generate much satisfaction with the teacher cohort. Vis-à-vis teacher training, the reading is clear: the needs of this group are high, variegated, and multifaceted. This echoes the tendency documented by Scanlan (Citation2011) and Cioè-Peña (Citation2017). Indeed, all the items in this category present means well over 4 and close to 5 on many occasions. This is most prominently the case on access to (m = 4.88) and design and adaptation of materials (m =4.69), language scaffolding techniques (m = 4.71), and student-centered methodologies (m = 4.68). These are precisely the three top picks of the teachers polled when they are asked to rank their main teacher development needs, thereby confirming the consistency of our outcomes. It is curious to note, in this respect, that the latter two aspects are also the ones they claimed to use more to support diverse learners, so that it seems they are avid for further training to sharpen and refine their implementation and effectiveness. Lower, albeit still considerable needs, are detected on how to engage parents (m = 4.11) and how to collaborate with colleagues to cater for diversity (m = 4.24). Finally, training in the use of different classroom organizations (m = 4.43), assessment techniques (m = 4.33), and critical analysis of their teaching practice (m = 4.30) do not figure prominently on the teacher development agenda for this cohort.

Students: global analysis

This next cohort, together with that of parents, has been under-investigated in comparison with that of teachers. In terms of linguistic aspects, students harbor an overwhelmingly positive outlook, in line with their practitioners. They consider the latter provide them with the adequate language support to understand difficult aspects (m = 4.92) and have their teachers’ specialized knowledge (m = 4.62) and language proficiency (m = 4.49) in high regard. More lukewarm appreciations of the content scaffolding received (m = 4.34) and of the use of translation as a support strategy (m = 4.34) transpire.

A less positive vision can be ascertained for methodology and types of groupings. The learners do not perceive much variety in the methodology used (m = 3.85) or in the classroom arrangements employed (m = 2.87). They also believe newcomer classes (m = 3.20) and Multiple Intelligence Theory (m = 3.72) are scarcely made use of, something which runs parallel to their teachers’ perspectives. They equally do not consider they receive personalized attention from their teachers (m = 3.89) or that peer assistance strategies are set in place frequently (m = 3.78). While they do consider that student-centered methodologies are capitalized on (m = 4.35), including cooperative learning (m = 4.28) and especially TBLT and PBL (m=4.44), they also uphold that teacher-frontedness still finds traction in their lessons (m = 4.10). Thus, although student and teacher views are very much aligned in this second heading, the learner cohort considers that less variety is incorporated and that the teacher is still a central figure in the learning process.

Once more, as had been the case with the practitioners, students are not fully satisfied with the materials available, as relatively low means are found across the board in this section. While students acknowledge that a combination of visual, textual, and numeric input is employed to cater for different abilities (m = 4.11) and that ICTs are also made use of (m = 3.80), they do not consider their textbook caters for diverse ability levels (m = 3.01) and their teachers thus have to resort to originally created (m = 3.72) or adapted (m = 3.46) materials. Thus, considerable headway needs to be made on this front, also according to this second cohort.

Evaluation is even more negatively gauged by the students. While the teachers considered certain formative assessment aspects more attuned to differing levels of ability, the students do not seem to sustain such a positive outlook on either ongoing or final assessment, although they do believe that formative evaluation techniques take different levels into account to a greater extent than summative ones (m = 3.85 vs. 3.55). Just like their teachers, they do not believe grading criteria are varied according to ability level (m = 3.27) or that homework (m = 2.78) or activities (m = 3.28) are aligned with diverse capacities. Different versions of the exam or extra time to complete it are not furnished (m = 3.03) and self-assessment is not fully capitalized on (m = 3.49). The provision of detailed guidelines (m = 3.78) and personalized feedback (m = 3.64) are the two most highly rated items. All in all, students do not consider that their performance has improved as a result of CLIL teachers taking into account different abilities (m = 3.43). Thus, evaluation in its manifold dimensions, needs to be tweaked and fine-tuned.

Finally, as regards this cohort’s faith in their teachers’ preparation to cater for diversity, the students consider it is the language teachers who are better equipped to do so (m = 4.70), followed by the language assistants (m = 4.44) and content teachers (m = 4.39). The guidance counselor comes next (m = 4.29). However, they are not as satisfied with the support of multi-professional teams (m = 3.12). It is thus not surprising that their overall outlook on the school’s support system is unenthusiastic (m = 4.19).

Parents: global analysis

Mirroring their offspring’s views, parents sustain an overwhelmingly positive outlook on teachers’ language (m = 4.52) and content (m = 4.5) knowledge, as well as their content (m = 4.46) and, especially, linguistic scaffolding (m = 4.59). This optimistic perspective is maintained, albeit mitigated, for the methodology and materials section, which continues to come across as generating the least satisfaction, together with evaluation. While parents do believe in the student-centeredness fostered in their children’s CLIL classroom (m = 4.58), where the use of Cooperative Learning (m = 4.73) and TBLT/PBL (m = 4.59) is promoted, not a lot acceptance is generated by the textbook’s potential to take into account different levels of ability (m = 3.1). As had occurred with the student cohort, different layouts (m = 3.82) or newcomer classes (m = 3.93) are not truly considered to be present, together with personalized attention in smaller groups (m = 3.98). MIT (m = 4.26) and different types of groupings (m = 4.26) are considered to be used to a greater extent than the students, and there is, all in all, a general satisfaction with the teachers’ sensitivity to different abilities (m = 4.22) and repertoire of methods to cater for them (m = 4.24).

Dissatisfaction clearly increases with assessment, where parents’ views are very much aligned with student perspectives. This third cohort does not consider that different levels of ability are catered for through either formative (m = 3.98) or summative (m = 3.94) evaluation. Like their children, the lowest-scoring items are the provision of different versions of the exam and of more time to complete them within summative evaluation (m = 3.20) and of different types of homework within formative assessment (m = 3.33). Personalized feedback (m = 3.91) and extra guidelines (m = 3.91) are the aspects which, according to the parents, just like their offspring, seem to be employed to a greater extent. Thus, it appears that parents are, in general, well-versed in the evaluation techniques employed in the CLIL classroom to cater for diversity, as their view is very much in harmony with that of their children. Room for improvement continues to transpire on this front.

The faith which the student cohort had in the teachers’ preparation is magnified for the parent cohort. Indeed, they highly appreciate the capacity of language teachers (m = 4.89), followed by guidance counselors (m = 4.83), language assistants (m = 4.81), and content teachers (m = 4.68), all of whom they consider are equipped to cater for differentiation in the CLIL classroom. The support of multi-professional teams is valued to a lesser extent (m = 4.08) and they do not consider they themselves are sufficiently engaged (m = 4.10). Thus, overall satisfaction with the support system (m = 4.29) is only lukewarm.

Across-cohort comparison

These differences across cohorts are empirically substantiated by Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests, in line with the second metaconcern (objective 4). Two main tendencies emerge as salient in the analysis (cf. ): the consistency between student and parent perspectives, where fewer statistically significant differences can be ascertained, and the penchant for greater teacher optimism. Indeed, the teacher cohort tends to harbor a more self-complacent view of their own communicative skills and specialized academic language to cope with diversity than the other two cohorts, something which echoes the trends discerned in previous studies (Pérez Cañado Citation2016b, Citation2018; Bauer-Marschallinger et al. Citation2021). Methodologically, they also consider they deploy a greater variety of methods to attend to diversity, provide personalized attention, and use peer-assistance strategies to a greater extent. They equally seem to be more aware of the effort they have to put into accessing, creating, or adapting materials than the remaining two cohorts, something not surprising since this task falls directly on the shoulders of the teachers, who are frontline stakeholders in this area. On practically all the aspects considered for evaluation, the teachers again believe they incorporate both formative and summative assessment techniques to a significantly greater extent than the other two cohorts, who are not as satisfied with how assessment caters for diversity levels in the CLIL classroom. Finally, as regards support systems, teachers are again more satisfied with multi-professional teams, the figure of the guidance counselor, and the way in which parents are engaged.

Table 1. Across-cohort analysis (Kruskal-Wallis test).

Students, in turn, have a significantly more negative outlook than the other two cohorts in the teacher-led component of the CLIL class, the use of different layouts and groupings, and the employment of self-assessment. Finally, parents more positively value the effort teachers make to be sensitive to different ability levels in CLIL classes, the student-centeredness of the latter (involving cooperative learning, MIT, TBLT, and PBL), and the different types of groupings. In this sense, parents come across as the most satisfied cohort with methodological aspects. They also most greatly appreciate the role of the language assistant and the schools’ support system. Thus, the broader take-away here is that this third cohort is highly appreciative of the way in which teachers and schools are rising to the challenge of diversity in CLIL contexts. This confirms the tendency ascertained in prior investigations (Ráez Padilla Citation2018; Barrios Espinosa Citation2019) and further refines them, as general levels of satisfaction with CLIL programs had been found for parents with a lower SES, but our study also confirms this hold true for those with substantially higher ones, such as those which predominate in our investigation. The parent cohort, it transpires, is thus generally invested in the bilingual education of their offspring and gives a vote of confidence to the way CLIL is rising to the new challenges it encounters in its evolution, such as its adaptation to the key issues of inclusion and differentiation.

Conclusion

The present study has allowed us to paint a comprehensive picture of where we currently stand vis-à-vis the way in which the challenge of diversity is being accommodated in bilingual education across Europe. The perspectives of the key players in CLIL programs (teachers, students, and parents) have been canvassed using methodological triangulation (questionnaires, interviews, and observation protocols) and location triangulation (Secondary school settings in six European countries). The outcomes depart from those of previous studies in revealing a largely consistent view on differentiation in CLIL programs among the three cohorts, which thus appears to be a realistic snapshot of grassroots practice in this arena at present. Vis-à-vis the first metaconcern (objectives 1-3), our results have evinced that all three groups consider an increased demand is posed by having to teach CLIL classes with different levels of achievers. Nonetheless, there is great trust placed in teachers’ communicative abilities and specialized academic language to do so. Scaffolding techniques and student-centered methodologies are particularly capitalized on to rise to the challenge (especially CL, TBLT, and PBL), as are formative assessment procedures. However, on the downside, materials are still undoubtedly a major hurdle to tackle, summative evaluation needs to be stepped up, the overall school support system requires reinforcement, and teacher training needs are high across the board (especially on materials design and adaptation, language scaffolding techniques, and student-centered methodologies).

As regards metaconcern 2 (objective 4), across-cohort comparisons have revealed disparities between teacher and student/parent perspectives, with much greater harmony between the latter two. Practitioners harbor a significantly more self-complacent view of their language level, methodological strategies, and assessment techniques. Although the remaining two cohorts also value these aspects, they do not perceive as much variety or student-centeredness as the instructors. Parents come across as the most satisfied group with methodological issues and they greatly appreciate the preparation of the diverse types of teachers and of the effort they are making to incorporate differentiation in CLIL.

These findings should inform future research on bilingual special education and they necessitate new pedagogical considerations regarding the ways in which educational systems across Europe should accommodate learner diversity. In this sense, four main lessons can be gleaned from these outcomes to fine-tune the future CLIL agenda. First and very importantly, current CLIL provision as it stands does not fit the bill in the new mainstreaming scenario: it needs to be reinforced, reengineered, and reshaped to respond to the new methodological, evaluative, collaborative, and training needs posed by educational differentiation in school-wide implementations. Secondly, the one-size-fits-all model definitely does not cut it in the new CLIL scenario and we need to maintain a ‘context-sensitive stance’ (Hüttner and Smit Citation2014, 164). The previous controversy which characterized CLIL implementation (cf. Pérez Cañado Citation2016c) and which criticized the flexibility inherent in these programs has now been superseded. Different countries deal with selectivity and inclusion in very different ways, and diverse policies and practices need to be implemented to respond adequately to these variegated realities. A third valuable lesson which can extracted is that the way forward lies in learning from the best practices of others. This study has identified key areas of expertise to favor integration in CLIL programs from a broader transnational perspective and working these into future teacher development courses is a crucial step in creating sustainable change.

A final salient take-away is that bilingual education continues to be viewed as prestigious and worthwhile. The cohort which decides whether to continue enrolling future generations in CLIL programs and, thus, to keep them alive -that of parents- very homogeneously trusts the teachers, methodologies, and support systems currently in place to ensure the educational success of diverse students. Despite the new and inevitable roadblocks which bilingual education encounters in its evolution towards mainstreaming, the faith of society in these programs is still running strong. And it is incumbent upon gatekeepers, practitioners, and frontline stakeholders to ensure the necessary measures are set in place to ensure CLIL programs continue to live up to the expectations they have created in the new scenario of diversity. In doing so, further research must guide the way. The cross-fertilization of the recurrent issues and pedagogical implications identified in this study should be addressed to provide a multimodal and comprehensive approach to meeting the intersectional needs of linguistically and academically diverse learners and to contribute to the creation of inclusive learning spaces. Therein lies the future sustainability of CLIL.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

María Luisa Pérez Cañado

Dr. María Luisa Pérez Cañado is Full Professor at the Department of English Philology of the University of Jaén, Spain, where she is also Rector's Delegate for European Universities and Language Policy. Her research interests are in Applied Linguistics, bilingual education, and new technologies in language teaching.

References

- Ainsworth, E., and V. Shepherd. 2017. An Evaluation of English Language Capability. Madrid: British Council.

- Anghel, B., A. Cabrales, and J. M. Carro. 2016. “Evaluating a Bilingual Education Program in Spain: The Impact Beyond Foreign Language Learning.” Economic Inquiry 54 (2): 1202–1223.

- Barrios Espinosa, E. 2019. “The Effect of Parental Education Level on Perceptions About CLIL: A Study in Andalusia.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. doi:10.1080/13670050.2019.1646702.

- Bauer-Marschallinger, S., C. Dalton-Puffer, H. Heaney, L. Katzinger, and U. Smit. 2021. CLIL for all? An Exploratory Study of Reported Pedagogical Practices in Austrian Secondary Schools.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1996533.

- Brown, J. D. 2001. Using Surveys in Language Programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bruton, A. 2011a. “Are the Differences Between CLIL and non-CLIL Groups in Andalusia Due to CLIL? A Reply to Lorenzo, Casal and Moore (2010).” Applied Linguistics 2011: 1–7.

- Bruton, A. 2011b. “Is CLIL so Beneficial, or Just Selective? Re-Evaluating Some of the Research.” System 39: 523–532.

- Bruton, A. 2013. “CLIL: Some of the Reasons Why … and Why Not.” System 41: 587–597.

- Bruton, A. 2015. “CLIL: Detail Matters in the Whole Picture. More Than a Reply to J. Hüttner and U. Smit (2014).” System 53: 119–128.

- Bruton, A. 2019. “Questions About CLIL Which are Unfortunately Still not Outdated: A Reply to Pérez-Cañado.” Applied Linguistics Review 10 (4): 591–602.

- Cioè-Peña, M. 2017. “The Intersectional Gap: How Bilingual Students in the United States are Excluded from Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (9): 906–919.

- Creswell, J. W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Dallinger, S., K. Jonkmann, and J. Hollm. 2018. “Selectivity of Content and Language Integrated Learning Programmes in German Secondary Schools.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (1): 93–104.

- Denzin, N. K. 1970. Sociological Methods: A Sourcebook. Chicago: Aldine.

- Fernández-Sanjurjo, J., A. Fernández-Costales, and J. M. Arias Blanco. 2019. “Analysing Students’ Content-Learning in Science in CLIL vs. non-CLIL Programmes: Empirical Evidence from Spain.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (6): 661–674.

- Fernández, R., and A. Halbach. 2011. “Analysing the Situation of Teachers in the Madridautonomous Community Bilingual Project.” In Content and Foreign Language Integrated Learning: Contributions to Multilingualism in European Contexts, edited by Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, J. M. Sierra, and F. Gallardo del Puerto, 241–270. Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang.

- Gortázar, L., and P. A. Taberner. 2020. “La incidencia del programa bilingüe en la segregación escolar por origen socioeconómico en la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid: Evidencia a partir de PISA.” REICE. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 18 (4): 219–239.

- Grieve, A. M., and I. Haining. 2011. “Inclusive Practice? Supporting Isolated Bilingual Learners in a Mainstream School.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (7): 763–774.

- Hüttner, J., and U. Smit. 2014. “CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning): The Bigger Picture. A Response to A. Bruton. 2013. CLIL: Some of the Reasons Why … and Why Not.” System 44 (2): 160–167.

- Junta de Andalucía. 2017. Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo de las Lenguas en Andalucía. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía. <http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/educacion/webportal/abaco-portlet/content/462f16e3-c047-479f-a753-1030bf16f822>.

- Lorenzo, F., S. Casal, and P. Moore. 2009. “The Effects of Content and Language Integrated Learning in European Education: Key Findings from the Andalusian Bilingual Sections Evaluation Project.” Applied Linguistics 31 (3): 418–442.

- Macaro, E., S. Curle, J. Pun, A. Jiangshan, and J. Dearden. 2018. “A Systematic Review of English Medium Instruction in Higher Education.” Language Teaching 51 (1): 36–76.

- Madrid, D., and M. E. Barrios. 2018. “A Comparison of Students’ Educational Achievement Across Programmes and School Types with and Without CLIL Provision.” Porta Linguarum 29: 29–50.

- Madrid, D., and M. L. Pérez Cañado. 2018. “Innovations and Challenges in Attending to Diversity Through CLIL.” Theory Into Practice 57 (3): 241–249.

- Martín-Pastor, E., and R. Durán Martínez. 2018. “La inclusión educativa en los programas bilingües de educación primaria: un análisis documental.” Revista Complutense de Educación 30 (2): 589–604.

- Mehisto, P., and H. Asser. 2007. “Stakeholder Perspectives: CLIL Programme Management in Estonia.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10 (5): 683–701.

- Paran, A. 2013. “Content and Language Integrated Learning: Panacea or Policy Borrowing Myth?” Applied Linguistics Review 4 (2): 317–342.

- Pavón Vázquez, V. 2018. “Learning Outcomes in CLIL Programmes: a Comparison of Results Between Urban and Rural Environments.” Porta Linguarum 29: 9–28.

- Pena Díaz, C., and M. D. Porto Requejo. 2008. “Teacher Beliefs in a CLIL Education Project.” Porta Linguarum 10: 151–161.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2016a. “Teacher Training Needs for Bilingual Education: In-Service Teacher Perceptions.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 19 (3): 266–295.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2016b. “Are Teachers Ready for CLIL? Evidence from a European Study.” European Journal of Teacher Education 39 (2): 202–221.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2016c. “From the CLIL Craze to the CLIL Conundrum: Addressing the Current CLIL Controversy.” Bellaterra Journal of Teaching and Learning Language and Literature 9 (1): 9–31.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2018. “CLIL and Pedagogical Innovation: Fact or Fiction?” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 28: 369–390.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2020a. “CLIL and Elitism: Myth or Reality?” Language Learning Journal 48 (1): 1–14.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2020b. “Common CLIL (mis) Conceptions: Setting the Record Straight.” In The Manifold Nature of Bilingual Education, edited by M. T. Calderón Quindós, N. Barranco Izquierdo, and T. Eisenrich, 1–30. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L., D. Rascón Moreno, and V. Cueva López. 2021. “Identifying Difficulties and Best Practices in Catering to Diversity in CLIL: Instrument Design and Validation.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1988050.

- Ráez Padilla, J. 2018. “Parent Perspectives on CLIL Implementation: Which Variables Make a Difference?” Porta Linguarum 29: 181–196.

- Rascón Moreno, D., and C. Bretones Callejas. 2018. “Socioeconomic Status and its Impact on Language and Content Attainment in CLIL Contexts.” Porta Linguarum 29: 115–136.

- Roiha, A. S. 2014. “Teachers’ Views on Differentiation in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Perceptions, Practices and Challenges.” Language and Education 28 (1): 1–18.

- Scanlan, M. 2011. “How School Leaders Can Accent Inclusion for Bilingual Students, Families, and Communities.” Multicultural Education, Winter 2011: 4–9.

- Somers, T. 2017. “Content and Language Integrated Learning and the Inclusion of Immigrant Minority Language Students: A Research Review.” International Review of Education 63: 495–520.

- Somers, T. 2018. “Multilingualism for Europeans, Monolingualism for Immigrants? Towards Policy-Based Inclusion of Immigrant Minority Language Students in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL).” European Journal of Language Policy 10 (2): 203–228.