ABSTRACT

Early trilingual development is an excellent testing ground for input reduction effects on acquisition outcomes. This article reports a study investigating input-outcome relations in a child Leo in Hong Kong, who was addressed to in Mandarin, Cantonese and later also in English by caretakers through ‘one caretaker-one language’ and ‘one day-one language’ practices. Caretaker-child interactions were recorded monthly from 1;6 to 2;11 and compared with monolingual baselines in grammatical complexity, lexical diversity and verb morphology. Receptive vocabulary tests were administered at 3;1. Results show that Leo, having accumulated 54%, 26% and 20% of his total input in Mandarin, Cantonese and English respectively from birth to three, demonstrated monolingual-like development in Mandarin and surprisingly, also in Cantonese in most lexical and grammatical measures. Hearing English primarily from non-native speakers, Leo was able to match monolinguals in receptive vocabulary and develop productive morphosyntax in English. The findings suggest that language distance and similarity should be taken into consideration in predicting developmental rates and outcomes of specific languages in trilingual development, and that the role of language input from non-native speakers in the acquisition of a third language warrants further examination.

1. Introduction

Language input from a child’s caretakers has an enormous impact on the language development of the child. However, relations between aspects of language input (e.g. amount, diversity, and complexity) and aspects of language acquisition outcome (e.g. phonology, vocabulary, grammar) are highly complex and dynamic (Ambridge et al. Citation2015; Rowe and Snow Citation2020). Infant or early trilingualism is a child’s acquisition of three languages before onset of speech (Quay Citation2011) or the age of three (Unsworth Citation2013). Trilingual development is an excellent testing ground for input-outcome relations. For children who grow up with three languages simultaneously, the input directed to the child in each language is likely to be reduced in terms of quantity and possibly in quality compared to their monolingual peers. The three-way split and reduced input in each language may bring about great effects of input reduction, which presents a revealing window where input-induced developmental differences from the monolingual norm can be observed in a relatively short period of time, and in a wider range of linguistic phenomena. However, longitudinal speech data from trilingual children and their input providers are still in very short supply (Quay Citation2011; Unsworth Citation2013). To fill this gap, this article reports a case study tracking the caretaker input and the trilingual development in a male child in Hong Kong for 18 months from 1;6 to 2;11.

2. Caretaker input and trilingual development

2.1. Input-outcome relations in early lexical and grammatical development

Huge variation exists in the talk that young children hear from their caretakers (Hart and Risley Citation1995). In early language development, there have been robust and consistent findings demonstrating strong input-outcome associations in lexical development. A number of fine-grained measures have been identified as indices of richness of the input: talkativeness (usually measured by total number of words or utterances in a given speech sample), lexical diversity (number of unique words), and grammatical complexity (mean length of utterance, MLU) positively correlate with the child’s vocabulary growth to varying extents. Infants and toddlers who have richer language experience are found to have a larger receptive and expressive vocabulary size in parental reports, produce more diverse words in caretaker-child conversations, score higher in standardized assessments such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT, Dunn and Dunn Citation1997) and process spoken words faster in looking-while-listening paradigms (Pan et al. Citation2005; Hurtado, Marchman, and Fernald Citation2008; Rowe Citation2012; Weisleder and Fernald Citation2013).

In terms of grammatical development, although input frequency can sometimes explain why certain structures are acquired earlier than others within a language (Theakston et al. 2004) and why structures of similar complexity are acquired at different times cross-linguistically (Ambridge et al. Citation2015), there has been less evidence for effects of input variation in monolingual children, let alone trilingual children.

2.2. Input-outcome relations in early bilingual development

Studies considering input variations in bilingual development have consistently found that the proportion of input in a language in the child’s total input (‘input proportion’) is a strong predictor of developmental rate in that language. In Hoff et al. (Citation2012), input-outcome relations in both vocabulary and grammar were examined in Spanish-English bilingual toddlers and their English monolingual peers in the US. The proportion of English exposure in the child’s total input was positively related with every outcome measure obtained through parental report in their study, whether lexical or grammatical. Note that in this study, the group of bilinguals (n = 14) who had balanced input in both languages (50-60% of the time) still differed from the monolingual group in both vocabulary score and mean length of longest utterances in English.

Nevertheless, Thordardottir (Citation2011, Citation2015) found that French-English bilingual 3-to-6-year-olds in Montreal were able to perform within the normal ranges of monolingual peers (operationalized as one standard deviation (SD) above or below the monolingual mean) in several measures of receptive and expressive vocabulary as well as productive morphosyntax when they had relatively equal exposure (50–60%) to both languages. Crucially, additional input beyond this point did not further facilitate development. This has led to the hypothesis that an input proportion of 50% is the threshold for monolingual-like development in lexicon and syntax in the language, at least for older bilingual children (3-to-6-year-olds) who are learning languages that are not too far apart from each other and enjoy relatively equal status in the community, like French and English in Montreal.

Hoff et al. (Citation2012) and Thordardottir (Citation2011, Citation2015) have important differences in terms of age range, outcome measures, language pairing and societal context, which might have led to the differences in their findings. Nevertheless, their studies have pointed out interesting directions for input-outcome studies. Extending the 50% threshold hypothesis originally proposed for bilinguals to trilinguals, if 50% of total input is a necessary condition for monolingual-like development in lexicon and syntax, it is expected that trilingual toddlers will inevitably lag behind their monolingual peers in at least two of the languages they are learning, since it is mathematically impossible for more than one language to take up 50% of a trilingual’s waking hours. This is a very testable yet untested prediction, which will be taken up by our study.

Another issue that we will address in our study is differences between language input provided by non-native speakers and native speakers (hereafter ‘non-native/native input’). Bilingual and trilingual children are very often raised by multilingual caretakers who address the child in their non-native and less fluent language. Research on the mature state of second language attainment has revealed systematic differences between native and non-native speakers across domains especially in morphosyntax (e.g. Lardiere Citation1998; Hopp Citation2010). There has been an emerging interest in effects of non-native input on early language development. Place and Hoff (Citation2011, Citation2016) measured vocabulary and grammatical growth of Spanish-English bilingual two-year-olds and associated their growth with aspects of their dual input documented through diary records kept by their caretakers. A positive correlation was found between the proportion of English exposure provided by native speakers and the child’s development in English in both comprehension and production.

Recently in Hoff, Core, and Shanks (Citation2020), non-native input was scrutinized through systematic comparisons of English input provided to English-Spanish bilingual toddlers by mothers with three different proficiency levels in English (‘limited’, ‘good’, ‘native’). Results show that those Spanish-L1 mothers who reported ‘good’ proficiency in English performed significantly better than mothers with only ‘limited’ proficiency in a number of input measures such as grammatical complexity and lexical diversity. Interestingly, those mothers with ‘good’ English proficiency, despite being non-native speakers of English, did not differ from native English mothers in any of the measures examined, indicating potentially native-like richness of language input provided by speakers with ‘good’ proficiency. Nevertheless, little do we know about native vs non-native differences in the English input provided by mothers speaking L1s other than Spanish. Given the prevalence of L1 influence on the L2 (Odlin Citation1989), L1-differences in non-native caretaker input should be taken into consideration. This study follows up on this issue.

2.3. Early trilingual development

Infants and toddlers who are regularly exposed to three languages at home can differentiate the languages at phonological, lexical and pragmatic levels by age 2. They are reported to develop active trilingualism to different degrees (Yang and Zhu Citation2010; Montanari Citation2009; Citation2010; Citation2011; but see Chevalier Citation2015 for cases of passive trilingualism).

In Montanari (Citation2010), the trilingual lexicon of Kathryn, a Tagalog-Spanish-English trilingual child in the US, was reconstructed through diary records and adult–child recordings between 1;4 and 2;0. Kathryn’s earliest cross-language doublets were formed by an item from Tagalog, which is the language she had received most input in (48%), and an item from either Spanish or English, the languages she had less input in (29% and 23% respectively). She did not produce triplets until later at 1;7, suggesting a relation between proportion of input and lexical development in that language. Interestingly, it took less time for triplets to emerge after doublets had appeared than it did for her to develop doublets after singlets. Apart from this study, little has been reported on fine-grained properties of the trilingual input and their impact on the child’s lexical or grammatical development.

Among the five major types of trilinguals sketched out in Hoffmann (Citation2001), children who grow up in trilingual communities belong to a distinctive category, since children raised in trilingual societies are more likely to have regular and frequent exposure to all three languages from a wide spectrum of native and non-native speakers both in and outside their home. Existing studies on trilingual development almost exclusively observed children growing up in monolingual communities like the UK and the US (e.g. Montanari Citation2009, Citation2010, Citation2011) or bilingual communities where only one or two of the languages being acquired by the trilingual child is spoken in the wider community (e.g. Yang and Zhu Citation2010). There is no longitudinal linguistic documentation of how toddlers develop trilingualism through interaction with caretakers in multilingual societies like Hong Kong.

3. This study

3.1. Research questions and predictions

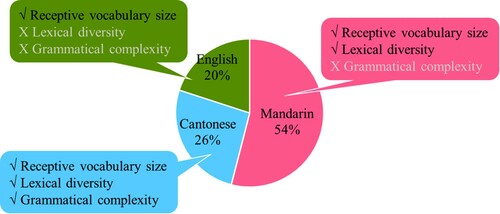

To fill the aforementioned research gaps, we contribute an open-access longitudinal corpus documenting the speech of a Mandarin–Cantonese-English trilingual child Leo and his main input providers from child age 1;6 to 2;1. In this article we present our first analysis of lexical and grammatical properties in the trilingual input and outcomes. Like many of his trilingual peers in the literature, Leo had uneven exposure to the three languages. By age 3, he had spent 54% of his waking hours with his father and paternal grandmother both speaking Mandarin to him, 26% of the time with his mother (first author of this article) speaking Cantonese to him and the remaining 20% of the time in English-speaking environments, predominantly with his mother, who is a native speaker of Cantonese and Mandarin and would rate her English as ‘good’, as opposed to ‘limited’ in the sense of Hoff, Core, and Shanks (Citation2020) (details of Leo’s language exposure to be introduced later). In this study, we focus on the lexical and grammatical domains and ask the following two sets of questions:

Input proportion and outcomes: For the trilingual child, will there be a one-to-one mapping between the proportion of his input in a language and the developmental outcome of that language? Will Leo perform within monolingual ranges in the language associated with more than 50% of his total input and below monolingual ranges in languages that do not meet the 50% input threshold? In languages where trilingual vs monolingual differences are evident, will lexical and grammatical development be equally affected?

Predictions: If the strong input-outcome associations found in bilingual children (e.g. Hoff et al. Citation2012) are extendable to trilingual acquisition, Leo is expected to display significantly stronger ability in Mandarin than in Cantonese or English and similar performance between Cantonese and English, considering the 54% vs 26% vs 20% distribution of his Mandarin, Cantonese and English input. Additionally, if the 50% input threshold proposed for bilinguals applies to young trilinguals, Leo should be indistinguishable from his monolingual peers in Mandarin, at least in receptive vocabulary and grammatical complexity as reported in Thordardottir (Citation2011, Citation2015), and will inevitably lag behind his monolingual peers in Cantonese and English in both lexical and grammatical measures. However, Mandarin and Cantonese are typologically very close with many transparent lexical cognates, overlapping structures and shared cultural heritage (Matthews and Yip Citation2011). If language distance is a moderating factor, Leo's Cantonese may profit from Mandarin and develop faster than English despite similar input proportions.

| 2) | Input quality: For the language in which the trilingual child receives input primarily from non-native speakers, does the non-native input differ from native input in terms of utterance length, lexical diversity and verb morphology? | ||||

Predictions: Spanish-L1 mothers with self-reported ‘good’ English proficiency have been found to provide native-like English input in terms of grammatical complexity and lexical diversity (Hoff, Core, and Shanks Citation2020). If this applies to Leo’s mother, who is a non-native yet ‘good’ speaker of English, her English input is expected to be similar to native English input in these two aspects. On the other hand, we predict non-native vs. native differences in grammatical structures that have not been examined by studies on Spanish-L1 mothers but are potentially vulnerable for Chinese-L1 mothers. Verb morphology has been reported to cause persistent difficulty for both adult and child Chinese-L1 learners of L2 English (Lardiere Citation1998; Paradis, Tulpar, and Arppe Citation2016), partially due to lack of positive transfer from Chinese, which is a typologically isolating language with little inflectional morphology. In this study, we focus on two inflectional morphemes on English verbs, namely, progressive -ing and past tense regular -ed, the acquisition of which demands generalization of rules from meaningful amounts of input.

3.2. Participants and methods

Leo was born and raised in Hong Kong, where a large number of residents are trilingual speakers of Cantonese, Mandarin (Putonghua) and English to different degrees. Cantonese remains the most widely spoken language in Hong Kong, with more than 85% of the Hong Kong population speaking Cantonese as their primary language (Census data: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/). Leo’s parents are originally from mainland China. His mother is an early bilingual proficient in both Cantonese (Guangzhou variety) and Mandarin (Putonghua), and fluent speaker of English. She had completed her postgraduate studies in language-related subjects in England and had been using English as the language of instruction for university-level linguistics courses. Leo’s father speaks Mandarin as his primary language and the Changde dialect (a variety of Southwestern Mandarin) as a secondary language. Leo’s paternal grandmother, who is a native speaker of the Changsha dialect (a variety of Xiang Chinese) and fluent speaker of Mandarin, cared for Leo during daytime on weekdays. The Changde and Changsha dialects were commonly used between the father and the grandmother, but almost never with the child. The parents conversed mainly in Mandarin, with occasional switches to Cantonese and English.

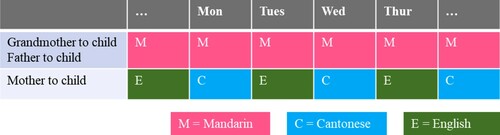

The family initially adopted a strict ‘one parent-one language’ practice in which the father and the grandmother addressed the child in Mandarin and the mother in Cantonese. Leo’s maternal and paternal grandfathers visited the family every few months and provided additional sources of input in Cantonese and Mandarin respectively. Leo’s systematic exposure to English began at 1;1 when his mother began to interact with him in English and Cantonese on alternate days in a ‘one day-one language’ pattern, illustrated in . Leo, although not conscious of the arrangement at this stage, usually responded to the mother in the language he was addressed in and did not have difficulty switching between languages. From 2;1 to 2;11, Leo attended nursery schools where classes were taught by native speakers of English. Another important source of English input came from a Tagalog-L1 Filipino domestic helper joining the family at child age 2;2. Leo remained the only child of the family before age 3, and his exposure to video or audio input through electronic devices was close to minimal.

Figure 1. Leo’s unique trilingual input model from 1;1, integrating ‘one parent-one language’ and ‘one day-one language’ practices.

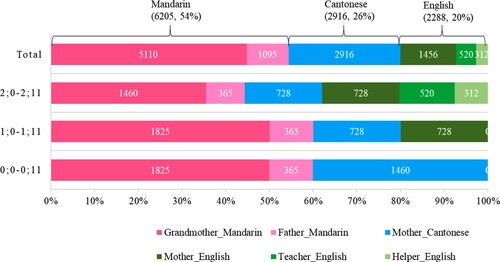

The mother kept a diary record of how much time and in what language Leo interacted with five of his primary input providers (mother, father, grandmother, English teachers, domestic helper). presents the cumulative amounts of time Leo spent with each input provider in each language in three one-year stages from birth to 3;0. Assuming that the amount of input in a language can be indicated, very roughly, by the amount of time a child spends with the caretaker speaking that language, Leo had accumulated 54%, 26% and 20% of his total input in Mandarin, Cantonese and English respectively by age 3.

Figure 2. Amount of time (in hours) Leo spent with his primary input providers from birth to 3;0 and their relative proportions.

Leo was video-recorded by a parent or research assistant at home since 0;6. In this study, we selected 54 recordings made in 18 consecutive months from 1;6 to 2;11. Each recording consists of 30-minute video documentation of Leo and one of his input providers engaged in daily routines and play activities, conversing in one of the three languages (‘the intended language’). The resulting corpus contains a total of 44,846 utterances. The speech data were transcribed and tagged by research assistants, and checked by the child’s mother for speech-to-text accuracy. The Leo Corpus, including transcripts and corresponding audio files, has been deposited in the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES, MacWhinney Citation2000) for open access (doi:10.21415/T5V398).

3.3. Monolingual baselines and the receptive vocabulary tests

Several longitudinal child language corpora from CHILDES were included in this study as monolingual baselines. Priority was given to the corpora and child cases which maximally match Leo and his corpus in terms of gender (male), socioeconomic status (middle), type of study (longitudinal and naturalistic), time and frequency of recording (monthly), adult interlocutor (caretaker) and age span (1;6-2;11). In cases with multiple transcripts in a month, we selected the first transcript to represent the child’s development in that month. summarizes the trilingual and monolingual corpus data selected for this study. For the corpus data, we used multiple measures such as MLU, word type and frequency to assess the input, the outcomes and their relations in the lexical and grammatical domains (details of calculation methods to be described later).

Table 1. Trilingual and monolingual corpus data selected in this study.

To gain insights into the trilingual child’s receptive vocabulary size in comparison with monolinguals, three supplementary vocabulary tests were administered to Leo at 3;1, namely, Mandarin Receptive Vocabulary Test for Hong Kong Children (MRVT) (Chan, Lee, and Yip Citation2014), Cantonese Receptive Vocabulary Test for Hong Kong children (HKCRVT) (Cheung, Lee, and Lee Citation1997) and Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-4) (Dunn and Dunn Citation2007). All tests were picture-identification tasks where the child was asked to listen to a target word in the target language and identify the picture that matched the target word from a set of four pictures.

4. Results

4.1. Trilingual outcomes

4.1.1. Mean length of utterance in words (MLUw)

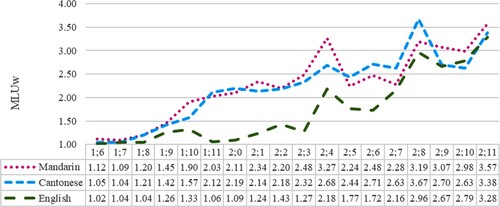

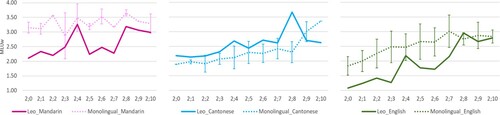

Mean length of utterance in words (MLUw) was used to index grammatical complexity in both the input and the outcomes. We calculated Leo’s MLUw in each language in the recordings intended for these languages in CLAN. Utterances switched into languages other than the intended language were excluded. As shows, from 1;6 to 2;11, Leo’s MLUw in Mandarin and Cantonese were very close to each other, whereas his MLUw in English fell notably below the two Chinese languages between 1;10 and 2;6, indicating relatively balanced and more rapid grammatical development in Mandarin and Cantonese than in English. Nevertheless, his English MLUw caught up rapidly from 2;7 and approximated those of the Mandarin and Cantonese at 2;11.

presents the trilingual versus monolingual comparisons. We follow the gist of Thordardottir (Citation2011) and define range of monolingual performance by 1 SD above or below the monolingual mean. Leo’s monthly MLUw in Mandarin and English fell below the corresponding monolingual ranges in 8 or 9 of the 11 months compared. Quite surprisingly, Leo’s MLUw in Cantonese was consistently higher than that of the monolinguals in 9 of the months.

Figure 4. Mean Length of Utterance in words (MLUw) in trilingual Leo and Mandarin monolingual children (n = 2; Deng and Yip Citation2018; Zhang and Zhou Citation2009), Cantonese monolingual children (n = 4, Lee et al. 1996) and English monolingual children (n = 6; Theakston et al. Citation2004). Error bars represent monolingual normal range defined as +/−1SD.

4.1.2. Lexical diversity

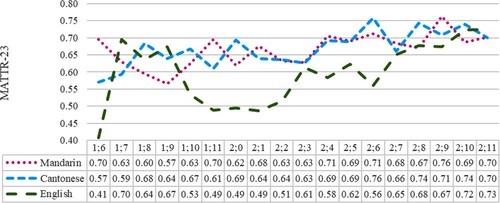

We adopted the moving-average type/token ratio (MATTR) algorithm (Covington and McFall Citation2010) rather than the traditional type/token ratio (TTR) to measure lexical diversity in the input and the outcomes. The MATTR algorithm, which calculates the average TTR of a sample from a series of successive windows of fixed length, is a stronger and fairer indicator of lexical diversity in naturalistic conversations uncontrolled for length and content (Fergadiotis, Wright, and West Citation2013). We follow Muhinyi and Hesketh (Citation2017) and set the window length at the token number of the shortest sample among all monolingual and trilingual samples under analysis in this study (i.e. 23 words). As shown in , the developmental trajectory of Leo’s MATTR closely resembles that of his MLUw in that there was a Mandarin/Cantonese-dominant stage when his Mandarin and Cantonese monthly MATTRs were visibly higher than his English MATTRs (around 1;10-2;6), followed by a stage when the monthly MATTRs of the three languages converged (after 2;7).

In trilingual versus monolingual comparisons, three distinct patterns emerged in the three languages, shown in . Leo's Mandarin MATTRs were indistinguishable from the monolinguals’ (t(10) = −.854, p = .413); his Cantonese MATTRs were visibly higher than the monolinguals’ throughout the period; and his English MATTRs were below the monolingual ranges throughout the period.

Figure 6. Moving Average Type/Token Ratio in 23-word windows (MATTR-23) in trilingual Leo and Mandarin monolingual children (n = 2; Deng and Yip Citation2018; Zhang and Zhou Citation2009), Cantonese monolingual children (n = 4, Lee et al. 1997) and English monolingual children (n = 6; Theakston et al. Citation2004). Error bars represent monolingual normal range defined as +/−1SD.

4.1.3. Receptive vocabulary tests

In Mandarin, Leo performed accurately in 90 out of 98 questions in MRVT, achieving an accuracy rate of 92%, which is comparable with age-matched children (3;0-3;5) who acquire Mandarin as their L1 in Beijing (n = 51, M = 93.5%, SD = 3.4%, Min = 87%, Max = 99%, Chan, Lee, and Yip Citation2014). In Cantonese, Leo provided 58 correct responses out of 65 questions (accuracy rate 89%) in HKCRVT, equivalent to the performance of children aged 5;2-5;3 in the norm. In PPVT, Leo obtained a raw score of 54 and a standard score of 107, which is at the 68th percentile in the age norms and equivalent to the average performance of children aged 3;8 in the US norm.

4.2. Input in English

We calculated the MLUw, MATTR and frequency of two grammatical morphemes in the English input and outcomes, presented in . For the input, we included utterances produced by Leo’s mother and the mothers of the six monolingual children in four months (2;3, 2;4, 2;5, 2;7), for which data from all seven mothers are available for comparison. Results show that Leo’s mother displayed means lower than the mothers of the monolingual children across measures. Her MLUw was within the monolingual normal ranges, whereas the other three measures of her input (MATTR in 100-word windows, percentages of progressive -ing and past tense -ed) were below the normal ranges to different extents. The non-native versus native differences in the input are more pronounced in lexical diversity and verb morphology than in grammatical complexity.

Table 2. MLUw, MATTR and frequency of verb morphology in the English input and outcome of Leo, compared with monolingual baselines.

For the outcomes, we included the English utterances produced by Leo and four of the six monolingual children, who have data from 2;0 to 2;10. Like his mother, Leo performed below the monolingual children across measures. However, unlike his mother, he only showed within-normal-range performance in one measure, namely, progressive -ing, producing 91 tokens on 30 different verbs, which is strong evidence for successful generalization and application of a suffixing rule. He produced only 2 tokens of past tense -ed markings in 2854 utterances, which does not constitute evidence for successful acquisition of the corresponding rules.

5. Discussion

5.1. Input proportion effects and the development of the two Chinese languages

We asked whether the trilingual child Leo, having accumulated 54%, 26% and 20% of his total input in Mandarin, Cantonese and English respectively over the course of three years, would develop Mandarin distinctively in a monolingual-like manner and more rapidly than the other two languages. Our results show that on the one hand, Leo demonstrated unambiguously more advanced performance in Mandarin than in English across lexical and grammatical measures, which is consistent with his input distribution. On the other hand, Leo did not develop Mandarin more rapidly than Cantonese. The developmental trajectories of these two languages went hand in hand in both grammatical complexity and lexical diversity throughout the study period. When compared with monolinguals, Cantonese is the only language in which Leo displayed monolingual-like performance across measures including receptive vocabulary size, lexical diversity and grammatical complexity, as shown in .

Figure 7. Trilingual child Leo’s three-way split input and language-specific attainment in terms of receptive vocabulary size, lexical diversity (MATTR-23) and grammatical complexity (MLUw) by monolingual standards. (√ = comparable to or better than monolinguals, X = below monolingual range)

Within a language, different patterns were found among the three outcome measures. In Mandarin, which is the only language associated with above-threshold input, Leo predictably performed within monolingual ranges in two lexical measures, but he was below monolingual ranges in grammatical complexity, which is not consistent with the input threshold effects documented in the bilingual literature. In this regard, Leo seems to have performed better in Mandarin than the balanced Spanish-English bilingual toddlers in the US did in English, who did not match their English monolingual peers in either lexical or grammatical measures (Hoff et al. Citation2012). This is probably due to Leo receiving his Mandarin input from more than one primary caretaker, who were both (near-)native speakers of Mandarin. Yet Leo did not perform as well as the balanced French-English bilingual 3-year-olds in Canada (Thordardottir Citation2011, Citation2015), who did not differ from the monolingual group in English MLUw. This seems to suggest that compared with vocabulary, productive syntax requires more input to develop at an earlier stage of development before age 3. Leo’s performance in English further reveals the advantage of receptive vocabulary over both lexical diversity and grammatical complexity in production. Taken together, our findings suggest that in trilingual development, both lexical and grammatical development are subject to input reduction in specific languages, with receptive vocabulary showcasing more resilience than other domains.

Our findings show that Leo had developed Cantonese substantially better than predicted based on input proportion alone and Cantonese displays remarkable resilience to input reduction very rarely seen in bilingual cases, which is inconsistent with the hypothetical one-to-one mapping relation between the input and the outcomes, as well as the threshold effects observed in bilingual studies. Cantonese being the societal dominant language may have played a role, but cannot fully explain its better-than-monolingual development in our trilingual child, for Leo had heard Cantonese from only one primary caretaker (mother) and one regular visitor (maternal grandfather), and had very limited experience with other speakers of Cantonese in or outside his home at this stage. Nor was Cantonese the lingua franca in the family. A more plausible account seems to be Cantonese profiting from positive transfer from Mandarin. The idea that positive transfer between languages may contribute to mitigating the reduction of input in each language in the form of cross-linguistic reinforcement is gaining attention. Studies have shown a unique role of form-similar translation equivalents in vocabulary learning by bilingual infants learning closely related languages (Schelletter Citation2002; Bosch and Ramon-Casas Citation2014). Positive transfer effects at the syntactic level were also reported in older Cantonese–English-Mandarin trilingual children (age 5–6; Chan et al. Citation2017), who demonstrated monolingual-like comprehension of Mandarin relative clauses despite very limited exposure to Mandarin, pointing to positive transfer from Cantonese. In our case, it is likely that cross-linguistic reinforcement between Mandarin and Cantonese has played a role in mitigating the severe reduction of Cantonese input in early trilingual development, the extent and magnitude of which is being investigated in an on-going endeavor involving the Leo Corpus and other trilingual children by the authors.

For future investigations, we hypothesize that cross-linguistic reinforcement, if any, should apply to all languages involved, but should be more pronounced in the language that is more reduced in terms of input proportion (e.g. Cantonese in Leo) than the one that is less reduced and has met the 50% input threshold (e.g. Mandarin in Leo).

5.2. Input quality and the development of English

We also asked whether Leo’s English input was reduced in qualitative terms. Analysis of the English input provided by Leo’s mother and by English-native mothers has revealed both non-native-like and native-like aspects in Leo’s mother’s input, cutting across lexical and morphosyntactic domains. Leo’s English input was within native ranges in terms of grammatical complexity, while falling below the native ranges in lexical diversity and verb morphology. The implication of this finding is twofold: having ‘good’ proficiency in English does not guarantee native-like lexical diversity in child-directed speech; and verb morphology, as predicted, is an additional vulnerability in non-native English input, at least for mothers whose L1 shares few lexical cognates with English and lacks rich verb inflection as a source of positive transfer. This adds new evidence to existing research conducted mainly with Spanish-L1 mothers (Hoff, Core, and Shanks Citation2020) and reveals fruitful directions for future investigations.

Our findings also speak to how much input is needed to trigger acquisition in lexical and grammatical domains. We have shown that the English input that Leo was exposed to was reduced to only 20% of what is assumed for monolinguals, and the quality of the input was also affected compared with monolingual standards. In this case, it is well expected that Leo should display protracted development in English. Although the design of our study does not allow us to tease apart effects of reduced quantity from those of reduced quality, Leo’s development in English shows that with only a fragment of what is assumed for normal monolingual native input, the trilingual child was able to meet monolingual standards in terms of receptive vocabulary and was able to develop productive morphosyntax. Admittedly, in monolingual English children, progressive -ing appears earlier than past tense -ed due to language-internal factors such as salience and consistency (De Villiers and De Villiers Citation1973), and is one of the ‘easier’ grammatical markers. Additionally, there is a strong possibility that Leo’s early acquisition of progressive -ing is facilitated by corresponding progressive aspect markers in Mandarin (-zhe) and Cantonese (-gan) (see Luk and Shirai Citation2018 for -gan and -ing in Cantonese–English bilingual children). Regardless, form-meaning mappings (however ‘easy’) and cross-linguistic correspondence (however transparent) have to be established based on a non-trivial amount of English input. Since English is technically a third language added to Leo’s linguistic repertoire at 1;1, Leo’s achievement shows that even a very small amount of input in the third language can trigger acquisition in both lexical and morphosyntactic domains at this very early stage of language development. Learning a third language is less effortful than learning a second language, even when the other two languages are still developing, echoing the findings with the Tagalog-Spanish-English trilingual in Montanari (Citation2010) and pointing towards an early bilingual benefit in acquiring a third language.

That said, meeting monolingual standards when the input is reduced to 20% and primarily from non-native speakers is remarkable. Two factors may have contributed to Leo’s better-than-predicted development in English and probably his language development in general. First, despite prevalent differences between English and the two Chinese languages, the three languages share a canonical word order of [subject-verb-object], which should generate cross-linguistically consistent syntactic cues for the trilingual child to develop at least the basic syntax that is reflected in the earliest MLUw, rendering the acquisition task less challenging than those in previous cases where the trilingual child had to sort out cross-linguistically diverse word order cues to break into the languages. Second, infants and toddlers have limited working memory and other cognitive and motor capacity. These limitations constrain what young learners can intake from the abundant and rich input, to the extent that some of the more sophisticated cues in the input is not effectively internalized by the child at earlier stages of language acquisition, resulting in what we dub as the ‘intake ceiling’ in language acquisition, a point held in Long and Rothman (Citation2014), Paradis and Grüter (Citation2014) and many others. This explains why multilingual children are able to match monolingual standards in some areas at this earliest developmental stage when cognitive capacity is most limited, but have difficulty keeping up with their monolingual counterparts later from (pre-)school age, when cognitive and motor capacity is more developed and the intake ceiling lifted, even when they are blessed with the best quality of input.

6. Conclusion

To our best knowledge, the Leo Corpus is the first and only open-access longitudinal trilingual corpus with child utterances and caretaker input from all three target languages systematically recorded for an extended period of time, when the few existing trilingual child language corpora in CHILDES only recorded the child and his/her caretakers in one or two of the target languages. We have found that unlike bilinguals, for whom the proportion of input in a language almost always correctly predicts the developmental rate of that language in relation to the other, a trilingual may develop one of the languages considerably faster than predicted by input proportion alone, benefiting from positive transfer from a closely related and relatively stronger language in the language triad, if any. The 50% input threshold hypothesis extended from bilingual studies may not be equally applicable to all three languages in a trilingual child. Language distance and similarity must be taken into consideration when predicting relative developmental rates and outcomes of specific languages in trilingual development.

In terms of input quality, we have identified lexical diversity and verb morphology as vulnerable areas in non-native caretaker input. Non-native versus native differences are evident in these areas even when the caretaker has ‘good’ proficiency in the language. We propose that non-nativeness in caretaker input may be modulated by multiple factors very similar to that in second language attainment. The input provider’s first language, for example, should play a prominent role in addition to general proficiency.

Despite well-known limitations in the generalizability of case studies like ours, Leo’s case demonstrates that productive trilingualism and monolingual-like performance in several important developmental domains are achievable in early childhood. The trilingual family’s innovative input model incorporating features of ‘one day-one language’ and ‘one parent-one language’ practices may be one effective way to turn multilingual resources of the child’s caretakers into quality language input that supports language development.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Brian MacWhinney, Director of CHILDES for his expertise, advice and technical support in constructing the Leo Corpus, and our colleagues Stephen Matthews, Xiangjun Deng, Zhuang Wu, Jiangling Zhou for their helpful suggestions and continuous support over the years. Our special thanks go to the research assistants for their dedicated efforts and meticulous work in recording the child and transcribing the data: Sophia Zishu Yu, Riki Yuqi Wu, Hannah Lam, Joy Jieyu Zhou, Christa Schmidt, especially Vaness Tsz Yan Law. Part of this study was presented at Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition Conference (GALA 14) in Milan, Italy; and the conference on ‘Acquisition of Chinese: Bilingualism and Multilingualism’ in Cambridge, UK. We thank participants of the conferences for their useful comments. The first author and Leo would like to dedicate this article to the loving memory of Leo’s maternal grandfather, who provided an additional source of authentic Cantonese input (and cuisine) for Leo until he passed away when Leo was 3;5.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ziyin Mai

Ziyin Mai is Assistant Professor at the Department of Linguistics and Translation at the City University of Hong Kong. Her current research projects investigate the (un)balanced development of Cantonese, English and/or Mandarin in multilingual children and the maintenance of Chinese in younger learners in English-speaking contexts.

Virginia Yip

Virginia Yip is Professor at the Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages and Director of Childhood Bilingualism Research Centre at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research interests include bilingualism, language acquisition and comparative Chinese grammar.

References

- Ambridge, B., E. Kidd, C. F. Rowland, and A. L. Theakston. 2015. “The Ubiquity of Frequency Effects in First Language Acquisition.” Journal of Child Language 42 (2): 239–273.

- Bosch, L., and M. Ramon-Casas. 2014. “First Translation Equivalents in Bilingual Toddlers’ Expressive Vocabulary: Does Form Similarity Matter?” International Journal of Behavioral Development 38 (4): 317–322.

- Chan, A., S. Chen, S. Matthews, and V. Yip. 2017. “Comprehension of Subject and Object Relative Clauses in a Trilingual Acquisition Context.” Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1641.

- Chan, A., K. Lee, and V. Yip. 2014. “A New Tool for Assessing Child Mandarin Receptive vocabulary.” Paper presented at the 13th International Congress for the Study of Child Language. Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Cheung, P. S. P., K. Y. S. Lee, and L. W. T. Lee. 1997. “The Development of the ‘Cantonese Receptive Vocabulary Test’ for Children Aged 2-6 in Hong Kong.” European Journal of Disorders of Communication 32: 127–138.

- Chevalier, S. 2015. Trilingual Language Acquisition: Contextual Factors Influencing Active Trilingualism in Early Childhood (Vol. 16). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Covington, M. A., and J. D. McFall. 2010. “Cutting the Gordian Knot: The Moving-Average Type–Token Ratio (MATTR).” Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 17 (2): 94–100.

- Deng, X., and V. Yip. 2018. “A Multimedia Corpus of Child Mandarin: The Tong Corpus.” Journal of Chinese Linguistics 46 (1): 69–92.

- De Villiers, J. G., and P. A. De Villiers. 1973. “A Cross-Sectional Study of the Acquisition of Grammatical Morphemes in Child Speech.” Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 2 (3): 267–278.

- Dunn, L. M., and L. M. Dunn. 1997. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

- Dunn, M., and L. M. Dunn. 2007. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-4. Circle Pines, MN: AGS.

- Fergadiotis, G., H. H. Wright, and T. M. West. 2013. “Measuring Lexical Diversity in Narrative Discourse of People with Aphasia.” American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 22 (2): S397–S408.

- Hart, B., and T. R. Risley. 1995. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Hoff, E., C. Core, S. Place, R. Rumiche, M. Senor, and M. Parra. 2012. “Dual Language Exposure and Early Bilingual Development.” Journal of Child Language 39 (1): 1–27.

- Hoff, E., C. Core, and K. F. Shanks. 2020. “The Quality of Child-Directed Speech Depends on the Speaker's Language Proficiency.” Journal of Child Language 47 (1): 132–145.

- Hoffmann, C. 2001. “Towards a Description of Trilingual Competence.” The International Journal of Bilingualism 5 (1): 1–17.

- Hopp, H. 2010. “Ultimate Attainment in L2 Inflection: Performance Similarities between Non-Native and Native Speakers.” Lingua 120 (4): 901–931.

- Hurtado, N., V. A. Marchman, and A. Fernald. 2008. “Does Input Influence Uptake? Links Between Maternal Talk, Processing Speed and Vocabulary Size in Spanish-Learning Children.” Developmental Science 11: F31–F39.

- Lardiere, D. 1998. “Dissociating Syntax from Morphology in a Divergent L2 End-State Grammar.” Second Language Research 14 (4): 359–375.

- Lee, T. H. T., C. H. Wong, S. Leung, P. Man, A. Cheung, K. Szeto, and C. S. P. Wong. 1996. “The Development of Grammatical Competence in Cantonese-Speaking Children.” Report of RGC Earmarked Grant, 1991–1994. https://childes.talkbank.org/access/Chinese/Cantonese/LeeWongLeung.html.

- Long, D., and J. Rothman. 2014. “Some Caveats to the Role of Input in the Timing of Child Bilingualism.” Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 4 (3): 351–356.

- Luk, Z. P. S., and Y. Shirai. 2018. “The Development of Aspectual Marking in Cantonese-English Bilingual Children.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 56 (2): 137–179.

- MacWhinney, B. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Matthews, S., and V. Yip. 2011. Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar. London: Routledge.

- Montanari, S. 2009. “Pragmatic Differentiation in Early Trilingual Development.” Journal of Child Language 36: 597–627.

- Montanari, S. 2010. “Translation Equivalents and the Emergence of Multiple Lexicons in Early Trilingual Development.” First Language 30 (1): 102–125.

- Montanari, S. 2011. “Phonological Differentiation Before age two in a Tagalog-Spanish-English Trilingual Child.” International Journal of Multilingualism 8 (1): 5–21.

- Muhinyi, A., and A. Hesketh. 2017. “Low-and High-Text Books Facilitate the Same Amount and Quality of Extratextual Talk.” First Language 37 (4): 410–427.

- Odlin, T. 1989. Language Transfer: Cross-Linguistic Influence in Language Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pan, B. A., M. L. Rowe, J. D. Singer, and C. E. Snow. 2005. “Maternal Correlates of Growth in Toddler Vocabulary Production in low-Income Families.” Child Development 76: 763–782.

- Paradis, J., and T. Grüter. 2014. “Introduction to “Input and Experience in Bilingual Development”.” In Input and Experience in Bilingual Development, edited by J. Paradis, and T. Grüter, 1–14. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Paradis, J., Y. Tulpar, and A. Arppe. 2016. “Chinese L1 Children's English L2 Verb Morphology Over Time: Individual Variation in Long-Term Outcomes.” Journal of Child Language 43 (3): 553–580.

- Place, S., and E. Hoff. 2011. “Properties of Dual Language Exposure that Influence 2-Year-Olds’ Bilingual Proficiency.” Child Development 82 (6): 1834–1849.

- Place, S., and E. Hoff. 2016. “Effects and Noneffects of Input in Bilingual Environments on Dual Language Skills in 2 ½-Year-Olds.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19 (5): 1023–1041.

- Quay, S. 2011. “Introduction: Data-Driven Insights from Trilingual Children in the Making.” International Journal of Multilingualism 8 (1): 1–4.

- Rowe, M. L. 2012. “A Longitudinal Investigation of the Role of Quantity and Quality of Child-Directed Speech in Vocabulary Development.” Child Development 83: 1762–1774.

- Rowe, M. L., and C. E. Snow. 2020. “Analyzing Input Quality Along Three Dimensions: Interactive, Linguistic, and Conceptual.” Journal of Child Language 47 (1): 5–21.

- Schelletter, C. 2002. “The Effect of Form Similarity on Bilingual Children's Lexical Development.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 5 (2): 93–107.

- Theakston, A. L., E. V. M. Lieven, J. M. Pine, and C. F. Rowland. 2004. “Semantic Generality, Input Frequency and the Acquisition of Syntax.” Journal of Child Language 31: 61–99.

- Thordardottir, E. 2011. “The Relationship Between Bilingual Exposure and Vocabulary Development.” International Journal of Bilingualism 15: 426–445.

- Thordardottir, E. 2015. “The Relationship Between Bilingual Exposure and Morphosyntactic Development.” International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 17: 97–114.

- Unsworth, S. 2013. “Current Issues in Multilingual First Language Acquisition.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33: 21–50.

- Weisleder, A., and A. Fernald. 2013. “Talking to Children Matters: Early Language Experience Strengthens Processing and Builds Vocabulary.” Psychological Science 24 (11): 2143–2152.

- Yang, H.-Y., and H. Zhu. 2010. “The Phonological Development of a Trilingual Child: Facts and Factors.” International Journal of Bilingualism 14 (1): 105–126.

- Zhang, L., and J. Zhou. 2009. “The Development of Mean Length of Utterance in Mandarin-Speaking Children.” In The Application and Development of International Corpus-Based Research Methods (in Chinese), edited by J. Zhou, 40–58. Beijing: Education Science Publishing House.