ABSTRACT

While existing studies on redistribution politics provide explanations of ‘who’ supports redistribution, we know very little about who supports ‘what’ type of redistribution. This omission is unfortunate because government spending has diverse functions and impacts, which are not differentiated in existing research. By capturing individual preferences for specific types of government policy under conditions of unemployment, we assess how economic insecurity influences calls for government action. Building on the analytic distinction between social consumption and social investment, this study examined the role of unemployment in social policy preferences. First, the experience of unemployment drives individual demand for social consumption but reduces support for social investment. Second, income levels have a heterogeneous effect on social policy preferences. In other words, a high income level is positively associated with support for social investment but negatively associated with support for social consumption. Third, the income effect is conditional on the experience of job loss, with the effect more pronounced in lower income groups than in higher income groups. An analysis of European Social Survey (ESS) Wave 8 (2016) data found empirical evidence supporting arguments about the impact of economic insecurity on individual preferences for a particular type of social expenditure.

Introduction

It is widely known that income levels and employment insecurity are major determinants of social policy and redistribution preferences. Extant research treats redistribution arguments as unidimensional conflicts related to income inequality and risks (Alt & Iversen, Citation2017; Iversen & Soskice, Citation2001; Moene & Wallerstein, Citation2001). Incidentally, a substantial amount of literature on social distance discusses why affinity between groups, for example, altruism, should be considered a major component of attitude formation (Cavaille & Trump, Citation2014; Dimick, Rueda, & Stegmueller, Citation2018; Lupu & Pontusson, Citation2011).

This paper explores the impact of employment insecurity on individual preferences for social policy. Employment insecurity in this paper refers to concerns, risks, and feelings of insecurity stemming from income loss due to unemployment or the prospect of job loss. Existing literature substantiates that exposure to risks stemming from various forms of economic challenges stimulates individual demand for the expansion of social spending and public provision of welfare (Anderson & Pontusson, Citation2007; Dancygier & Walter, Citation2015; Margalit, Citation2011; Rehm, Citation2009; Rehm, Hacker, & Schlesinger, Citation2012). When facing difficult economic situations, especially unemployment, individuals have a tendency to demand that the government take a larger and more active role in providing social protection. Although numerous studies have accounted for the impact of individual economic insecurity on social policy preferences (Anderson & Pontusson, Citation2007; Cusack, Iversen, & Rehm, Citation2006; Iversen & Cusack, Citation2000; Iversen & Soskice, Citation2001; Rehm, Citation2009, Citation2016; Thewissen & Rueda, Citation2017), existing research, to the best of our knowledge, has not addressed the effect of employment insecurity on support for a particular type of social spending. Most studies assume a proportional tax and lump-sum benefit (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2015; Meltzer & Richard, Citation1981), while ignoring the varied facets of social spending. In this paper, we explore how employment insecurity shapes individuals’ attitudes in favor of or against specific forms of social spending from among numerous types of government expenditures.

This paper makes a conceptual distinction in social spending and focuses on two types of social expenditures: social investment and social consumption (Beramendi, Hausermann, Kitschelt, & Kriesi, Citation2015). Social investment refers to public expenditures that aim to boost the economy’s overall productivity. In contrast, social consumption focuses on compensating for current and immediate losses and taking care of urgent needs. Social investment measures expect future gains delivered over the long term, whereas social consumption initiatives target short-term, current benefits. Consequently, for the purpose of our analysis, what matters is not the total sum of social spending but the specific and different functions of social spending.

Building on the analytical distinction between social investment and social consumption, we make the following arguments. First, we argue that employment insecurity will induce individuals to favor immediate, short-term benefits (i.e. social consumption) over gradual, long-term gains (i.e. social investment). The rationale behind this argument is that higher levels of employment insecurity are likely to make an individual focus heavily on immediate compensation in the form of cash transfers such as unemployment benefits. Second, we argue that income levels have a heterogeneous effect on social policy preferences. A high income level is positively associated with support for social investment but negatively associated with support for social consumption. It should be noted at the outset that our argument hinges on the assumption of a choice between social investment and social consumption given a fixed budget constraint. Third, we claim that there is an interaction effect between income levels and discontinuity in labor market participation. More specifically, we argue that while there is a disparity in the average level of support for social investment and social consumption in the face of unemployment, the gap is more pronounced in lower-income groups.

By analyzing data from the European Social Survey (ESS) Wave 8 (2016), we found empirical evidence that supports our theoretical expectation that employment insecurity has heterogeneous effects on individual preferences for a particular type of social spending. Specifically, we analyzed a survey question that asked whether a respondent prefers a certain type of social spending: social investment or consumption. The main findings of the analysis suggest that employment insecurity is positively associated with support for immediate unemployment benefits at the expense of long-term social investment such as education and training programs. In other words, employment insecurity induces people to prefer social consumption over social investment. The effect of employment insecurity on the relative preferences for social consumption is distinct among the poor. That is, the secure poor and insecure poor show a remarkably contrastive pattern in terms of their preferences for social consumption and social investment. These findings are robust and can satisfy a variety of sensitivity analyses and robustness checks.

This study makes several contributions to the literature on comparative political economy and the study of redistribution politics. First, our arguments and evidence reveal the effect of employment insecurity on the preferences for specific types of social spending. While extant research on social policy preferences focuses on the average level of support for social spending, this study shows a more nuanced pattern of social policy preferences through a disaggregated analysis. Rather than assuming a one-dimensional conflict relating to more or less, this paper analyzes data on whether individuals prefer a certain policy over another. We contend that a study of more nuanced policy preferences is important, particularly in the context of recent growing discussions about new growth models in comparative political economy (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016). Second, this paper addresses the subjective risk measure, i.e. personal employment uncertainty and insecurity, which is distinctive from the objective risk measures, often estimated by income and occupation level (Anderson & Pontusson, Citation2007; Cusack et al., Citation2006; Rehm et al., Citation2012). While objective risk measures have made valuable contributions to the study of redistribution politics, we contend that the subjective measure can capture the effect of unemployment experiences on individual preferences for different types of social policy. Third, our findings about the interactive effect of income levels and employment insecurity may shed some light on pro-welfare and pro-redistribution coalition dynamics. In this respect, our study can be complementary to Rehm et al.’s (Citation2012) study on insecure alliances.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In the next section, we briefly review existing research on risks and individual preferences for redistribution policy. We then present a theoretical framework of the relationship between employment insecurity and support for social investment or social consumption. We then introduce our empirical strategy and present the results of the analysis. The last section summarizes the findings and concludes with some implications for the political economy in the knowledge economy era.

Risks, worries, and redistribution preferences

Classical research has heavily focused on income levels as a core determinant of social policy and redistribution preferences. Based on the seminal work of Meltzer and Richard (Citation1981), studies have suggested that the rich and poor have the same in-group preferences, but different out-group attitudes when it comes to deciding on a country’s optimal redistribution policy. Individuals calculate their future gains and current losses when choosing policy options provided by the government. Essentially, according to this line of argument, income has a strong correlation with individual preferences for redistribution, and thus redistribution coalitions are formed and aligned according to income levels (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2006). Simply put, individuals situated in lower income deciles will support increased public social spending, whereas individuals with high incomes will favor decreases in government spending.

However, the empirical incongruence between the Meltzer-Richard hypothesis and the ‘Robin Hood paradox’ (Lindert, Citation2004) has prompted important studies on the political economy of redistribution that suggest a forceful linkage between risks and redistribution preferences (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2001; Moene & Wallerstein, Citation2001; Rehm, Citation2016). Those studies have provided the general framework that shows how risk exposure is related to the formation of individual preferences regarding social spending. Risks stem from various sources, including income, skill, labor market status, and occupation. Scholars have demonstrated that greater exposure to risks induces people to support generous government spending in order to be compensated for future losses.

An important source of risk is skills that individuals possess. Skills are a strong predictor of social policy preferences as they directly affect individual labor market prospects. Studies have suggested a skill-specificity effect on support for social protection (Häusermann, Kurer, & Schwander, Citation2014; Iversen & Soskice, Citation2001; Rehm, Citation2009; Walter, Citation2017). Because of varying degrees of transferability, policy preferences are expected to differ according to the level of skill specificity. Skill levels, often measured by education levels, affect individual attitudes toward social policy preferences. As people with lower levels of skill have lower chances of securing a stable and high-paying job, their need for protection from and spending by government is greater compared to that of high-skilled workers. For instance, globalization has engendered contrasting perceptions between high- and low-skilled workers. A disparity in risks exists because low-skilled workers are situated in a more fragile position than high-skilled workers who are relatively better positioned and thus less affected by global economic competition (Häusermann et al., Citation2014; Walter, Citation2017). However, rather than assuming that dichotomous skill groups (high-skilled and low-skilled) hold heterogeneous preferences, Häusermann et al. (Citation2014) elucidate that risks and challenges could strongly influence even high-skilled individuals in vulnerable situations.

In this regard, much research has consistently acknowledged that exogenous economic shocks or threats are positively associated with demands for social policy (Häusermann et al., Citation2014; Margalit, Citation2011; Thewissen & Rueda, Citation2017). Some argue that global competition has negligible effects on individual redistributive policy preferences (Rehm, Citation2009), while others argue that the global economic situation is partially responsible (Häusermann et al., Citation2014). Globalization and deindustrialization have had massive impacts on individual perceptions of economic and occupational status (Dancygier & Walter, Citation2015; Walter, Citation2017). The ‘losers’ of globalization are specifically challenged by diverse threats, including low transferability of skills (Walter, Citation2017), whereas high-skilled professionals find such situations threatening to a lesser degree.

Similarly, studies using individual-level analysis, which assume that preferences are formed by material interest, show that employment insecurity affects individual perceptions and behavior and thus fuels the demand for social protection. Those in a vulnerable economic state hold the government responsible for their insecurity and thus demand a large welfare state. Existing studies have focused on an objective measurement of employment insecurity. This perspective assumes that workers have identical economic concerns according to their occupation or the industry they work in. Consequently, various studies have predicted a redistribution conflict among class or occupational groups. However, a sizable body of research has focused on micro-level perceptions and the effects of subjective employment insecurity on social policy preferences (e.g. Anderson & Pontusson, Citation2007). These studies define insecurity in a psychological and subjective manner. For instance, Anderson and Pontusson (Citation2007) predict that economic insecurity disproportionally affects individuals depending on their individual attributes and the labor market situation.

There are three problems with existing studies of risks and policy preferences. First, most existing studies examine total social spending without specifying the policies directing those expenditures. This neglects the different functions of social policies. Social policies differ in terms of whether they seek to compensate for current losses or stimulate job creation that could alleviate the economic stress of potential beneficiaries. Second, most studies rely on the question of the role of government in reducing income inequality. However, asking whether or not one supports government spending on measures to reduce inequality does not capture individuals’ expectations about the government’s role in tackling future uncertainty. In particular, it fails to control for other confounders, such as the notion of fairness and altruism, that may have strong effects on redistribution preferences. Finally, extant studies have fallen short of providing convincing explanations about the heterogeneous effects of either income level or unemployment uncertainty on social policy preferences. We take up these issues in the next section in suggesting our theoretical frameworks and expectations.

Employment insecurity and social spending preferences

This section provides a theoretical framework that links employment insecurity with distinctive preferences for social spending. First, we classified the types of social policies based on their functions: social investment and social consumption. Second, building on the analytical framework of Beramendi et al. (Citation2015), we explored how economic status influences individuals’ perceptions about their future uncertainty and preferences for social policy.

Distinguishing social policy: social investment and social consumption

While studies on redistribution politics provide explanations of ‘who’ supports redistribution, we know very little about who supports ‘what.’ This omission is unfortunate because social policy measures have different functions and impacts. Moreover, studies placing little emphasis on specific types of social spending can overlook individuals’ heterogeneous expectations from social policy measures, which can lead to a different pattern than the average level of spending (Moene & Wallerstein, Citation2003). We deconstructed different parts of welfare state policy and focused on labor market policy and unemployment. Since unemployment or labor market status directly and significantly affects individuals as well as the society as a whole, a large portion of the welfare state has concentrated on helping its citizens recover from economic hardships. People seek to minimize their current or possible insecurity and want to be compensated by government action, either in an active or in a passive way (Rueda, Citation2014). By capturing individual preferences with respect to specific types of government policy under unemployment conditions, we assessed how employment insecurity produces differing demands for government action.

Recent studies emphasize the need for conceptual distinctions in social policy (Beramendi et al., Citation2015; Häusermann et al., Citation2014; Malhotra, Margalit, & Mo, Citation2013). Referring to recent studies on social policy preferences, we built on the analytical framework of Beramendi et al. (Citation2015) that discusses the diverse functions of government spending. We adopted the two-dimensional classification of social spending: investment and consumption. Government spending serves different functions. Social investment aims at building capacity for future uncertainty, while social consumption compensates for job and income losses that cause immediate uncertainty. The distinction between investment and consumption sheds more light on the functions and objectives of government policy, as well as on how individuals shape their expectations for specific policies in the face of employment insecurity. Social policy and spending are a combination of redistribution from the rich to the poor and implementation of a protection mechanism for future loss. Thus, the differences in social policy measures are not consistent with a Meltzer-Richard-type purely redistributive model. In this regard, we do not expect a negative linear relationship between income and social policy. Social policies also vary depending on the beneficiary type. Social investment measures such as education and training provide benefits to the general workforce. Social consumption, on the other hand, targets only those who do not have a stable employment status.

The effects of risks on social investment and social consumption

In this section we draw testable hypotheses from the theoretical discussions. First, we address how unemployment influences preferences for different types of social policies. We test our argument by employing a survey specific question asking individuals to choose between government spending on investment and consumption. Second, we explore how unemployment and income are related in shaping policy preferences. We empirically test our theoretical hypothesis by analyzing the income effect in the face of unemployment.

The basic assumption of our argument is that individuals form their preferences based on economic interest. Therefore, an unstable economic condition affects preferences for social policy that can attenuate adverse labor market conditions. Furthermore, rather than assuming redistribution preferences as a whole, we addressed distinctive social policies and their effects on individual labor market capacity. In the conceptualization of economic risks, diverse sources contribute to workers’ concerns. Objective sources are income, occupation, and skill-specificity (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2001; Rehm, Citation2009), while subjective sources are individual perceptions and experiences (Anderson & Pontusson, Citation2007). Any experience of unemployment and long periods of job seeking in the past have a substantial effect on the expectations of future insecurity. We directly consider unemployment to test whether this economic threat has distinctive effects on support for the welfare state.

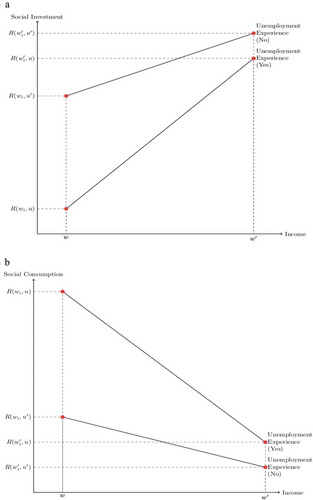

presents the theoretical expectations for the preferences for social investment vis-a-vis social consumption. We posit our three hypotheses. Our first argument, which explains how economic insecurity shapes individual preferences, is that the experience of unemployment will make individuals favor immediate benefits (i.e. social consumption) over long-term gains (i.e. social investment) (H1). The rationale behind this argument is that higher levels of employment insecurity boost the immediate need for cash transfers such as unemployment benefits. In other words, unemployment conditions drive individuals to favor need-based upfront compensation, while reducing support for long-term investment. Studies have found that employment insecurity influences individual preferences and has a strong impact on psychological cognition and attitudes toward redistribution (Anderson & Pontusson, Citation2007). Thus, although people find social investment to have a positive impact on their future economic capacity, those who are unemployed will demand instant, short-term benefits through social consumption measures, rather than long-term gains via social investment.

Second, studies that highlight the income effect on redistribution preferences explain that income levels are negatively associated with the demand for the expansion of government spending on welfare (Meltzer & Richard, Citation1981). The Meltzer-Richard model of redistribution politics explains that since low-income earners have more to gain and less to lose from an increase in social spending, the demand for welfare state increases as income falls. Furthermore, class contention appears to be a function of perceptional differences regarding redistribution: that is, the unemployed bank on egalitarian principles, whereas the employed lean toward meritocratic ideals (Demel, Barr, Miller, & Ubeda, Citation2018). However, an examination of the one-dimensional conflict between who wants more and who wants less government spending does not capture the specific needs of individuals in a given economic context.

This study challenges past literature that argues that the rich and secure want less and the poor and insecure want more redistribution. In our view, both groups pursue specific functions of social policy for insurance against future uncertainty. We expect income levels to have heterogeneous influences on social policy preferences (H2). While income levels are positively associated with support for social investment, the need for social consumption is drastically weakened among the high income group in a tight budget scenario. In addition, higher income individuals are also sensitive to redistribution policy in that government spending serves as insurance that can minimize future loss (Moene & Wallerstein, Citation2001).

Finally, we argue that the effect of income levels on preferences for social investment/consumption is conditional upon employment insecurity (H3). While the average level of support for both types of spending is associated with income, the gap between secure and insecure labor market status is likely to be more pronounced among the poor. This expectation is related to Alt and Iversen’s (Citation2017) argument that the interaction between labor market segmentation and income levels has a negative influence on redistribution preferences. In other words, income levels and unemployment experience are intertwined when it comes to shaping preferences for types of social spending. For social investment, we expect the relationship between income levels and support for social spending to be positive or upward sloping: that is, higher-income groups prefer investment in active labor market policies such as training and education. The experience of unemployment, however, reduces the average demand for investment, with the decline more pronounced in lower-income groups. For social consumption, on the other hand, income levels are negatively associated with support for social spending, and the relationship is downward sloping. It should be noted that our expectations are based on the assumption of a trade-off-type budget constraint. Unemployment boosts the need for greater social consumption measures. This difference is more pronounced in lower-income groups. Thus, it is plausible to think that social policy preferences are a function of employment insecurity, while the interaction between unemployment and income reinforces the disparity in preferences between social investment and social consumption.

Empirical strategy

In this section, we first introduce ESS data, which we analyzed as they directly capture preferences for social investment and social consumption. We then present the results of our analysis and highlight how individual preferences for social investment in comparison with consumption depend on the interaction between unemployment and income levels.

In the theoretical framework, we argued that individuals who have experienced job losses or employment insecurity would prefer immediate unemployment benefits, rather than long-term gains via social investment initiatives such as education and training programs. Furthermore, we expected this pattern to be pronounced in low income groups. We analyzed data from the ESS Wave 8 (2016), which contained a wide range of questions and responses from 23 countries (15 Western European and 8 Eastern European countries; for the list of countries, see Table A2 in the Appendix). In our analysis we only included the respondents in the age of 15–65, since this economically active age group is more directly relevant to the focus of our study. For the 2016 wave, the ESS asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with a variety of welfare policies, programs, and projects. We extracted specific questions that were related to whether individuals had preferences for social investment or consumption. Education and training, for example, have been regarded as social policies intended to stimulate employment (Häusermann et al., Citation2014; Häusermann & Schwander, Citation2012; Rueda, Citation2015). While such active labor market policies do not provide direct cash-transfers and benefits, they strengthen individuals’ position in the job market through government investment. An alternative for social investment is social consumption, which addresses the immediate needs of the affected individuals by compensating for their job or income losses. To measure social insurance against income loss, for example, Moene and Wallerstein (Citation2001) have classified government expenditures into seven categories: disability cash benefits, occupational injury and disease compensation, sickness benefits, services for the disabled and elderly, survivors’ benefits, active labor market policies, and unemployment insurance. Individuals can be compensated for their income losses via need-based redistribution through passive labor market policies (Häusermann et al., Citation2014; Häusermann & Schwander, Citation2012).

Social investment

One of the dependent variables for this analysis was the preferences for social investment. We used the following specific question: ‘Now imagine there is a fixed amount of money that can be spent on tackling unemployment. Would you be against or in favor of the government spending more on education and training programs for the unemployed at the cost of reducing unemployment benefit?’ The answers were rated on four-point scale ranging from 1 (‘strongly against’) to 4 (‘strongly in favor’). In accordance with Rehm (Citation2009, p. 2011), we categorized the answers into a binary variable, coded 1 if ‘in favor’ or ‘strongly in favor’ of spending more on education and training programs, and 0 otherwise.

This question allowed us to directly capture individual preferences for social investment versus social consumption. If a respondent had to choose between increasing social investment (education and training programs) and boosting social consumption (unemployment benefits) in a scenario involving tight budget constraints, their responses clearly indicated their attitudes toward specific types of social policy. One caveat of using this question was that it presumed a trade-off situation in which a respondent is forced to choose either of them. While it is reasonable to think that one could prefer increases in spending on both social investment and social consumption, it should be noted that the question we used nonetheless presumed a trade-off in the face of budget constraints.

Social consumption

In light of the caveat in the specific question mentioned above, we analyzed a widely used question to judge respondents’ attitudes toward social consumption: ‘It is the government’s responsibility to provide a decent standard of living for unemployed.’ The answers were rated on a 0–10 scale, where 0 indicated ‘strong disagreement’ and 10 ‘strong agreement.’ We recoded the variable into a binary measure so that 1 denoted support for unemployment benefits (6–10 on the original scale) and 0 indicated opposition (0–5 on the original scale). To ensure that the results of our analysis are not sensitive to our choice of measurement of the variables, we present the results that use the original 11-point scale (continuous variable) in Table A6 in the Appendix.

Studies use social insurance categories, including cash benefits and services for the unemployed, for measuring preferences on social consumption. When people experience employment insecurity, which policy would they choose to mitigate their current uncertainty and improve their situation? If individuals opt for government action for the betterment of the unemployed, it indicates that they believe that short-term consumption is the way to tackle economic insecurity. Those against the government assuming this type of responsibility would appear to be unsupportive of utilizing immediate transfers and benefits to deal with any current vulnerability. Unlike active labor market policies, the task of providing a decent standard of living for the unemployed requires compensating them for their current income losses and allocating benefits based on economic scarcity.

Employment insecurity

For the explanatory variable, we used questions from the ESS that ask whether individuals are currently unemployed or have been unemployed in the past. As suggested in the theoretical section, the unemployed are likely to favor immediate unemployment benefits, while the employed would prefer government interventions with long-term impact such as education and training programs. Moreover, we addressed the interaction effect of income level and employment insecurity on preferences for social policy.

To get an idea about unemployment experiences and employment insecurity, we used the ESS questions on current employment insecurity (‘Ever unemployed and seeking work for a period more than 3 months’) and any prior experience of insecurity in the recent past (‘Any period of unemployment and work seeking within last 5 years’). The questions are as follows: ‘Ever unemployed and seeking work for a period more than 3 months’ and ‘Any period of unemployment and work seeking within last 5 years.’ As shown in Table A3 in the Appendix, 28.2% of the respondents answered ‘yes’ to the first question, while 46.7% said ‘yes’ to the second question. The total number of responses was 44,169 (Yes 71.8%; No 28.2%) for the first question and 12,406 (Yes 46.7%; No 53.3%) for the second question.

Controls

Our analysis included standard control variables frequently used in studies on redistribution preferences (Ansell Citation2010; Busemeyer, Citation2014; Gingrich & Ansell, Citation2012; Rehm, Citation2009). We included education level (1–7 scale), age, gender (male = 1, female = 0), and union membership (former, current membership = 1, otherwise = 0). Studies have demonstrated that older people and women tend to support redistribution, while union membership is known to be positively associated with demands for generous social spending (Mosimann & Pontusson, Citation2017). We also included country fixed effects in the model. Although it would have been ideal to include a measure of perceived social mobility, the ESS Wave 8 did not contain a question on perceived social mobility. Descriptive statistics are included in Table A1. in the Appendix.

Results

Our theoretical expectations were as follows: (1) Employment insecurity is likely to be associated with individual preferences for social consumption over investment. (2) Income levels have heterogeneous effects on social policy preferences. (3) There is an interaction effect between income level and the experience of unemployment that is likely to be more pronounced in lower income groups than other income groups. Does unemployment have a strong explanatory power in terms of individual support for more spending on education and training programs? We estimate probit models as the dependent variable was measured as a dichotomous variable.

shows the estimates for the determinants of social policy preferences. In the theoretical framework, we expected the uncertainties rooted in any past experience of job loss to result in different social policy preferences. Models (1) and (2) show the effect of the unemployment experience (experience = 1, otherwise = 0) and income levels on support for social investment. Consistent with the hypothesis, the results of the analysis suggested that the experience of unemployment is negatively associated with support for education and training programs vis-à-vis unemployment benefit. Individuals who have experienced employment insecurity tend to support more short-term unemployment benefits (social consumption) and fewer long-term education and training programs (social investment), even though the latter serves as an insurance against labor market vulnerability and provides an opportunity to strengthen the labor market position (Häusermann & Schwander, Citation2012; Iversen & Soskice, Citation2001). The results suggest that any discontinuity in labor market participation reduces the attachment to social insurance that aims at enhancing future capacity.

Table 1. Risk and preferences for social investment vis-à-vis social consumption.

The control variables show that union membership is associated with support for unemployment benefits, rather than education and training programs for the unemployed, while male respondents support investment over consumption. Model (3) presents individual preferences regarding social consumption. The findings suggest that employment insecurity increases support for social consumption, which is consistent with the theoretical expectation that the experience of unemployment influences individual perceptions and accordingly shapes preferences for spending on social consumption.

The results also support the second hypothesis: the expected effect of income levels. While previous studies assume that those who feel economically insecure desire more redistribution and that high-income groups oppose increases in government spending (Lupu & Pontusson, Citation2011; Rehm, Citation2009), the results of our study contradict the conventional argument. Income levels have heterogeneous effects on social policy preferences; they are positively associated with social investment but negatively related to social consumption. This shows that although high-income groups oppose increases in government spending, when it comes to active labor market policies, they support education and training initiatives that enhance employment prospects. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution given that the specific question that we used in our analysis is based on the assumption of a trade-off in the face of a budget constraint. In light of this caveat, it is more reasonable to think that high income groups support social investment only relative to social consumption.

Notably, lower-income groups do not always support social policy. Economic vulnerability intensifies risks among lower-income groups and boosts preferences for need-based redistribution, instead of enhanced labor market position (Häusermann et al., Citation2014). While high income groups prefer government spending on education and training programs over spending on compensation for current income losses, low income people prefer to be compensated in the form of immediate benefits for their discontinuous labor market participation. This pattern is identical in both groups with unemployment experience.

Model (2) and (4) depict the third argument of the study, which identifies the interaction effect of risk and income level. visually presents the results. Based on the analysis, we found that income levels have a positive association with social investment spending relative to social consumption. The results also demonstrate a conditional effect of income levels and unemployment experiences. We estimated the model with two variables and added control variables to examine whether income levels had a heterogeneous effect on preferences depending on the experience of job insecurity. The predicted probability of preferences for investment again supports our theoretical argument. Income levels are positively associated with the preferences for labor market investment such as education and training programs, but the average level of support decreases as employment insecurity rises. General support for social investment is correlated with income. However, any experience of a job loss reduces overall support, with this decrease more pronounced in the lower income group. The difference between those individuals who have experienced job loss and those who have not varies by income level, with the gap larger among the lower-income groups. The result is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

), which shows the conditional effects of employment insecurity and income levels on social consumption, tells us an expected story. This pattern is identical in the way that low income groups are sensitive to the experience of job loss. Those individuals who perceive high employment insecurity tend to demonstrate higher levels of support for government spending to compensate for any losses they might incur, compared to those who have never experienced any employment insecurity. This difference between job insecurity groups is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

Robustness checks

To ensure that the results are not sensitive to particular measures, model specifications, or samples, we conducted several robustness checks. First, we re-estimated the baseline model with a different measure of unemployment experience: joblessness within the last five years. The results reported in Table A4 in the Appendix are qualitatively similar to the ones reported in . That is, with a different measure of employment insecurity, we still found evidence that support our hypotheses. Our main results were robust to the use of different measurement of employment insecurity.

Second, to ensure that our results are not sensitive to the composition of the countries in the sample, we re-estimated our model with Western Europe only. We can take into account the possibility of heterogeneity in the democratic decision-making process. Table A5 in the Appendix shows that the results for the West European countries are qualitatively similar to those for the sample, which includes both West and East European countries.

shows the predicted probabilities of support for social policy. The estimated pattern turned out to be similar to the one in , but the predicted level of support for social policy seems stronger among Western Europeans only. Regarding support for social consumption, the difference between those respondents who have unemployment experiences and those who do not have such experiences disappears when income levels get higher (above 7 out of ten-scale).

Third, we re-estimated the model of support for social investment and social consumption by using the original 4-point and 11-point scale, respectively. The OLS estimates are reported in Table A6 in the Appendix. The results show similar patterns as the ones reported in . Our findings were not sensitive to our choices of estimation models and measurement of the variables.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have shown that employment insecurity tends to prompt individuals to favor immediate benefits (i.e. social consumption) over long-term gains (i.e. social investment). Furthermore, we found evidence of heterogeneous effects by income level in the face of employment insecurity. More specifically, although high income individuals tend to show higher levels of support for social investment than for social consumption, they support short-term benefits when they experience job losses and employment insecurity. Our findings suggest that individuals have heterogeneous preferences and perceptions driven by economic challenges.

This paper makes several contributions to comparative political economy. First, our analysis provides a more nuanced and refined way to tap into citizen preferences for social policy. We go beyond existing studies that analyzed aggregate measures of policy preferences. We contend, in line with Moene and Wallerstein (Citation2003), that our understanding of citizens’ policy preferences with the help of more refined and disaggregate analysis of policy preferences would make it possible to implement proportionate and accountable policies. This is important because current economic and social advancements are reshaping the global occupational structure, presenting new socio-economic risks for individuals and the society. Salient issues regarding globalization and automation are changing citizens’ concerns and interests, thereby generating new gaps in redistribution politics.

Second, our findings can be considered to be on the demand side of a trade-off between passive and active labor market policy. In this respect, Knotz and Lindvall’s study (Citation2015) of coalition governments and trade-offs between active and passive labor market policies may complement our findings. While their study tells a top-down story of a trade-off between unemployment benefits and education and training programs, this study has provided a bottom-up story of that trade-off. However, this study did not include institutional effects on individual preferences. Future research should focus on the impact of the electoral or education system (e.g. vocational training system) on citizens’ behavior and attitudes. Education should be considered a part of electoral politics since educational institutions and policies have been created by ‘politically motivated choices’ (Busemeyer, Citation2014) and have implications for income redistribution. It would be an interesting line of future research to address the relationship between employment insecurity and voting behavior and to examine institutional effects on education spending.

Third, our analysis of social investment and consumption can shed some light on the political economy of contemporary social risks. Social risks have increased, and traditional welfare state transfers and consumption-focused policies cannot adequately address these new challenges. Workers now find themselves in a vulnerable economic position as they face threats from not only foreign competition and migrant workers but also robots. These new technologies and global relocations have reshaped workers’ concerns and desires, while weakening the traditional income/skill coalition (Iversen & Soskice, Citation2015). Demographic changes and economic shifts result in the restructuring of existing coalitions and interests. Therefore, a simple dichotomous grouping of the redistribution conflict between the rich and poor cannot be applied to discern redistributive demands and preferences. In this new era, social investment in the long run and social consumption in the short run should be adequately captured to identify demand-side politics. Challenged by global economic changes, individuals demand to be compensated by governments, requiring the State to take an active role in public policy.

The limitation of this analysis is that it is restricted to specific survey questions that determine individual preferences for social investment and consumption in a presumed trade-off situation. Nevertheless, our findings are robust and can satisfy different measures of social policy preferences and a series of sensitivity analysis. For the next discussion, it would be worthwhile to employ a survey experiment design that assesses individual preferences for specific policies with more questions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. Previous versions of this article were presented at 2018 East Asia Social Policy Network and 2019 European Political Science Association conference. This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A2A2042808). Materials for replication will be posted on Harvard Dataverse upon publication of the article (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/hkwon).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at here.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seobin Han

Seobin Han is a graduate student in the Department of Political Science and a junior research fellow in the Center for the Study of Inequality and Democracy at Korea University. Her research interests are comparative political economy and political methodology. She has published an article in the Journal of Governmental Studies (in Korean).

Hyeok Yong Kwon

Hyeok Yong Kwon is a Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center for the Study of Inequality and Democracy at Korea University. He previously taught at Texas A&M University in the USA. His research on comparative political economy and political behavior has been published in journals such as the British Journal of Political Science, Electoral Studies, Party Politics, Political Research Quarterly, and Socio-Economic Review, among others.

References

- Alt, J., & Iversen, T. (2017). Inequality, labor market segmentation, and preferences for redistribution. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 21–36.

- Anderson, C. J., & Pontusson, J. (2007). Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research, 46(2), 211–235.

- Ansell, B. W. (2010). From the ballot to the blackboard: The redistributive political economy of education. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2016). Rethinking comparative political economy: The growth model perspective. Politics & Society, 44(2), 175–207.

- Beramendi, P., Hausermann, S., Kitschelt, H., & Kriesi, H. (2015). The politics of advanced capitalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Busemeyer, M. R. (2014). Skills and inequality: Partisan politics and the political economy of education reforms in western welfare states. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Cavaille, C., & Trump, K.-S. (2014). The two facets of social policy preferences. The Journal of Politics, 77(1), 146–160.

- Cusack, T., Iversen, T., & Rehm, P. (2006). Risks at work: The demand and supply sides of government redistribution. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 22(3), 365–389.

- Dancygier, R. M., & Walter, S. (2015). Globalization, labor market risks, and class cleavages. In P. Beramedi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt, and H. Kriesi (Ed.), The politics of advanced capitalism (pp.133–156). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Demel, S., Barr, A., Miller, L., & Ubeda, P. (2018). Commitment to political ideology is a luxury only students can afford: A distributive justice experiment. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 6(1), 33–42.

- Dimick, M., Rueda, D., & Stegmueller, D. (2018). Models of other-regarding preferences, inequality, and redistribution. Annual Review of Political Science, 21, 441–460.

- Gingrich, J., & Ansell, B. (2012). Preferences in context: Micro preferences, macro contexts, and the demand for social policy. Comparative Political Studies, 45(12), 1624–1654.

- Häusermann, S., Kurer, T., & Schwander, H. (2014). High-skilled outsiders? labor market vulnerability, education and welfare state preferences. Socio-Economic Review, 13(2), 235–258.

- Häusermann, S., & Schwander, H. (2012). Varieties of dualization? labor market segmentation and insider-outsider divides across regimes. In P. Emmenegger, S.Häusermann, B. Palier, and M. Seeleib-Kaiser (Ed.), The age of dualization: The changing face of inequality in deindustrializing societies (pp. 27–51). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Iversen, T., & Cusack, T. R. (2000). The causes of welfare state expansion: Deindustrialization or globalization? World Politics, 52(3), 313–349.

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2001). An asset theory of social policy preferences. American Political Science Review, 95(4), 875–893.

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2006). Electoral institutions and the politics of coalitions: Why some democracies redistribute more than others. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 165–181.

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2015). Democratic limits to redistribution: Inclusionary versus exclusionary coalitions in the knowledge economy. World Politics, 67(2), 185–225.

- Knotz, C., & Lindvall, J. (2015). Coalitions and compensation: The case of unemployment benefit duration. Comparative Political Studies, 48(5), 586–615.

- Lindert, P. (2004). Growing public: Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lupu, N., & Pontusson, J. (2011). The structure of inequality and the politics of redistribution. American Political Science Review, 105(2), 316–336.

- Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., & Mo, C. H. (2013). Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: Distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 391–410.

- Margalit, Y. (2011). Costly jobs: Trade-related layoffs, government compensation, and voting in us elections. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 166–188.

- Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

- Moene, K. O., & Wallerstein, M. (2001). Inequality, social insurance, and redistribution. American Political Science Review, 95(4), 859–874.

- Moene, K. O., & Wallerstein, M. (2003). Earnings inequality and welfare spending: A disaggregated analysis. World Politics, 55(4), 485–516.

- Mosimann, N., & Pontusson, J. (2017). Solidaristic unionism and support for redistribution in contemporary Europe. World Politics, 69(3), 448–492.

- Rehm, P. (2009). Risks and redistribution: An individual-level analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 42(7), 855–881.

- Rehm, P. (2016). Risk inequality and welfare states: Social policy preferences, development, and dynamics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rehm, P., Hacker, J. S., & Schlesinger, M. (2012). Insecure alliances: Risk, inequality, and support for the welfare state. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 386–406.

- Rueda, D. (2014). Dualization, crisis and the welfare state. Socio-Economic Review, 12(2), 381–407.

- Rueda, D. (2015). The state of the welfare state: Unemployment, labor market policy, and inequality in the age of workfare. Comparative Politics, 47(3), 296–314.

- Thewissen, S., & Rueda, D. (2017). Automation and the welfare state: Technological change as a determinant of redistribution preferences. Comparative Political Studies, 52(2), 171–200.

- Walter, S. (2017). Globalization and the demand-side of politics: How globalization shapes labor market risk perceptions and policy preferences. Political Science Research and Methods, 5(1), 55–80.