ABSTRACT

This article reports on a survey of Norwegian compulsory school music teachers, in which 293 teachers from 239 schools participated. In addition to providing demographic information, the teachers were asked what kinds of music their students listened to, sang, played, and created during lessons, and what activities this music was part of. We explore this material with respect to which forms of activities were included and how they were distributed, how the activities were related to teacher characteristics, what forms of participation the activities allowed for, and how this participation relates to broader societal patterns. The findings show that a broad palette of activities was implemented, but also that teachers with less formal competence in music chose activities that allowed for broader participation than their more musically specialised colleagues. Drawing on Bourdieu's concept of refraction, we interpret this as the latter being loyal to the logic of the art field.

Introduction

School music education has a long history in many countries, including Norway. In the Norwegian context, the inclusion of the music subject as part of compulsory education can be understood, historically, to originate from the strong Bildung impact on the national educational system, wherein developing the whole person towards becoming an ‘emancipated, self-determined, but socially responsible human being’ (Karlsen and Johansen Citation2019, 449) was a central idea, and one part of this development was seen to come through engagement with the arts, such as music. Later on, such engagement became a self-evident part of the welfare state policy that has permeated Norwegian politics since the post-WWII era (for an excellent discussion of Bildung and the concept's meaning for international music education policy, see Kertz-Welzel Citation2017). The most recent Norwegian national white paper on cultural politics states that participation in cultural life should be a central right: ‘Everyone should be able to exercise and expand their own cultural expressions and participate in and influence cultural life’ (Meld. St. 8. Citation2018–2019, 40, our translation). Such participation is seen as vital for, among other things, social inclusion, maintaining a participatory democracy, and also the future of the welfare state, since it is thought to foster much-needed ‘creativity and innovation’ (61). Furthermore, it is in accordance with the UN convention on the rights of the child (Article 31) which states that children have the right to participate fully in cultural and artistic life (Convention on the rights of the child, 1989). ‘Everybody's right to participation’ is also a central tenet, and one of the main responsibilities, of the national school system and is viewed as intimately connected to the upholding of society. In the recently reformed national core curriculum, it is emphasised that students ‘must … be given equal opportunities so they can make independent choices’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020a, 4) and that ‘[a] democratic society is based on the idea that all citizens have equal rights and opportunities to participate in the decision-making processes’ (8). As such, education should ‘provide a good point of departure for participation in all areas of education, work, and societal life’ (9). A similar ideal of, and turn towards, students’ participation is integral also to international research approaches and discourses which argue for ‘socially just’ and/or ‘democratic’ music education. Influential contributions in this regard are The Oxford Handbook of Social Justice in Music Education (Benedict et al. Citation2015) and the work of scholars such as Gould (see for example Gould Citation2007), Hess (Citation2019) and Kallio (Citation2015).

In the context of the Norwegian National Curriculum, participation is stressed in the music syllabus by pointing out that by engaging with music in and through the music subject, the students will be prepared for a lifelong relationship with music as well as for participation in the parts of ‘societal and working life that require aesthetic skills, creativity, and sociality’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020b, 2, our translation). In the description of the overarching theme of ‘performing music’, such musical engagement is further explicated to involve ‘students’ active engagement with voice, body, and instruments in musical interaction, performance, and play and within different musical expressions and genres’ (2). From other parts of the syllabus, it is evident that this also involves creating and listening to music and acquiring knowledge about music's deep intertwinement with culture. Thus, the music subject also contributes to realising the broader educational and participatory ideal, which is again deeply rooted in welfare state ideology, as shown above.

While our research is conducted in the Norwegian context, and the findings are also framed and interpreted with this in mind, we hold, with Schmidt (Citation2013), that one should also be able to think phenomena that originate from local policy ‘within a global reality’ (103). Thus, we invite the reader to understand the findings of this article with the potential they hold for meaningfully informing situations and initiatives elsewhere, in a time where also the UN Sustainable Development Goal No. 4, emphasising quality education (United Nations, Citationn.d.), seems more pertinent than ever.

Previous research

Typically, there will be more music lessons taught annually throughout Years 1–7 than during lower secondary school (Years 8–10). Research and scholarly contributions relating to school music depict it as, among other things, being synchronised with students’ musical preferences and interests to a very variable degree (Anttila Citation2010; Lamont et al. Citation2003), as enhancing the quality of school life if given in rich measure (Eerola and Eerola Citation2014), as being experienced differently depending on social class background (Bates Citation2012), and as manifesting differently with regard to practices and activities depending on the national educational system within which it occurs (Sepp, Ruokonen, and Ruismäki Citation2015). Based on the final observation, we choose here to give a brief overview of previous research on school music education in Norway.

In addition to regular national reports on teacher competence in all school subjects, including music (see e.g. Perlic Citation2019), there have been a few attempts to map the happenings within school music in Norway in the past ten years by way of surveys, one at the national level (Espeland et al. Citation2013) and two more regionally targeted (Christophersen, Iversen, and Tvedt Citation2017; Sætre, Ophus, and Neby Citation2016; see also Sætre Citation2018), all three having in common a rather low number of music teacher participants, ranging from 46 to 140. What can be learned from these surveys is, among other things, that the activities facilitated in the classroom typically differ between grades. For example, composing and playing music are more frequently implemented activities in Years 5–7 than in Years 1–4 (Espeland et al. Citation2013, 162). It can also be learned that there are connections between the teachers’ formal competence in music and the teaching content and activities they choose to emphasise in their practice (Sætre, Ophus, and Neby Citation2016, 15). According to Sætre (Citation2018), operating within a sample of 135 Norwegian music teachers, ‘teachers with music teaching competence seem to teach music in a systematically different way than teachers with less competence’ (555), and these high-competence teachers ‘include a wider range of musical content and activities in their classes than less-trained teachers’ (555). That music may be a rich but also challenging subject to teach is made evident through a recent anthology involving a number of Norwegian music education scholars (Holdhus, Murphy, and Espeland Citation2021), in which music education is conceptualised as a craft. According to Espeland (Citation2021), writing within the same anthology, a music teacher needs to master the interplay between the traditional and the innovative, the creative and the improvisational, and the material and the embodied (Espeland Citation2021). In Dobrowen’s (Citation2020) study of 16 compulsory school music teachers, the manifold aspects involved in teaching are conceptualised slightly differently, highlighting the ability to ‘facilitate the well-being of the teacher and the student […] handle the teaching of music […] [and] legitimise professional practice’ (139) as central. Altogether, the complexity of teaching music seems to demand much from the teacher.

Theoretical framework

In the research project from which the survey reported in this article originates (see more on this below), access to a wide range of musical content and activities is seen to have a specific social meaning, with particular classed connotations, and in the framework employed, such access as well as the ability to display and implement rich musical tastes are connected to theoretical notions such as fields, games, cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1996), cultural omnivorousness (Peterson Citation1992; Bennett et al. Citation2009; Faber et al. Citation2012) and musical gentrification (Dyndahl, Karlsen, and Wright Citation2021; Crossley Citation2015). Within music education scholarship, similar approaches include the much-cited edited anthologies by Wright (Citation2010) and Burnard, Trulsson, and Söderman (Citation2015), both of which present a range of contributions using Bourdieu's conceptualisation of fields, games, habitus, and capitals in relation to music education. For curriculum-oriented studies, see also Moore (Citation2012) on the relations between students’ musical backgrounds and their experiences of music in higher education and Wright’s (Citation2008) sociological take on students’ possibilities of influencing the music curriculum. In the following, we give a brief account of the above-mentioned theoretical notions’ interconnections and their relevance to the present study.

In Bourdieu’s (Citation1984, Citation1996) investigations of the social dynamics of societies, music holds a position as the cultural expression that, most efficiently of all, lends itself to social distinction due to its status as the most ‘“pure” artfield par excellence’ (Citation1984, 19). ‘Purity’, in this context, refers to a field's apparent autonomy from adjacent fields, such as the seeming independence of a field of art (or science) from political, commercial, and educational necessities. Bourdieu insists on homologous relations between fields of cultural production (as they are historically situated in the present) and the broader, social field of power within which they are located (Citation1996, 161–166). Significantly, however, the field of power is not mirrored but refracted by fields of art and cultural production (Citation1996, 220). The autonomy – ‘purity’ – of the music field is noticeable in the way political, commercial, and educational demands and logics change (while maintaining their relevance) according to field-specific demands and logics:

The degree of autonomy of the field may be measured by the importance of the effect of translation or of refraction, which its specific logic imposes on external influences or commissions, and by the transforming, even transfiguring, effect it has on religious or political representations and the constraints of temporal powers. (Bourdieu Citation1996, 220)

Methods

The present study is part of a larger research project exploring musical upbringing and schooling for children and young people in Norway, in which one of the sub-studies focuses on compulsory school music education.Footnote1

Research design

The present survey was designed as a questionnaire with open-ended questions as well as predefined responses (see more below) and aimed to recruit state-employed teachers in Norwegian compulsory school music education, Years 1–10, during 2018/2019 and 2019/2020.Footnote2,Footnote3 Since no ECTS credits in music are required for teaching music throughout Years 1–7 in Norway, higher music education qualification was not a prerequisite for participating in the study. The only requirement for participation was that the respondents taught music at the time of answering the survey. In the following, we therefore refer to the teachers as ‘music teachers’, regardless of their formal qualifications.

Based on data from the Norwegian Compulsory School Information System (GSI),Footnote4 we conducted purposive sampling (De Vaus Citation2013) of 800 compulsory schools. In our selection, we included schools from every municipality in Norway according to population, also allowing for a representative distribution of primary, lower secondary, and combined (primary plus lower secondary) schools, and of larger and smaller school units. The research group carrying out the survey succeeded in collecting the email addresses of and sending invitations to 1082 music teachers working at 537 schools in 323 municipalities.Footnote5 A total of 293 teachers from 239 schools chose to answer the questionnaire, a response rate of 44.5% at the school level.

The electronic implementation of the survey was produced by Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences using the Checkbox online survey software, and the teachers accessed the questionnaire through an electronic link in the email invitation. Upon logging in, the teachers were informed that they would consent to participate in the study in filling out and submitting the questionnaire. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Since email addresses were collected, we chose not to guarantee full anonymity in the research process. However, in accordance with the ethical recommendations of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (nsd.no), we asserted the teachers that any information given would be anonymised in all presentations and publications from the project.

Participants

The teachers participating in the survey were well qualified, both generally as educators and more specifically as music educators. Of these, 98.6% (282 teachers) had some form of teacher education, and 79.3% (226 teachers) had earned formal qualifications in music (see for more details). Their ages ranged from 23 to 67 years, with a mean of 41.7 years (SD = 10.3 years; N = 284). Of the respondents, 190 (64.8%) identified as female, and 94 (32.1%) as male, one did not wish to give information about gender while eight did not respond. As many as 220 (77.2%) of the teachers reported engaging in leisure-time music activities, either as professional musicians or as amateurs. Most had more than five years’ experience of teaching in the compulsory school system (see for more details).

Table 1. Background information survey participants. The N varies for each variable according to the number of responses given.

The design of the questionnaire

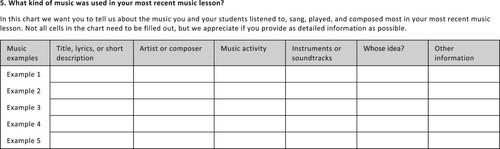

In addition to questions about formal education, age, gender, years of teaching experience, and leisure-time music activities, we also asked the teachers to describe what kinds of music they and their students listened to, sang, played, and created during lessons. Among other things, the questionnaire provided them with two charts to complete, one regarding ‘the music used in your most recent music lesson’ (hereafter CI), and one for describing ‘the music that you regularly use in your music lessons’ (hereafter CII). Each chart allowed for five examples of music (see ), and for each example, the teachers were asked to state the following: (a) the title, a text fragment, or a short description of the music used, (b) the artist/composer of the music, (c) the activity the music was part of, and (d) other comments. In CI, we also asked where the idea to use this music came from, and what sources of sound/technology were employed. In addition, we asked for details concerning the context of the lesson – grade/year, group size, and educational circumstances (regular music lesson, school assembly, etc.).

Analysis

We carried out the analysis on two fronts simultaneously, and in two steps. The two charts mentioned above generated a total of 1865 examples of music/musical activities. In the first step of the analysis, we coded and analysed all examples with the help of qualitative data analysis software (NVivo). This was mainly an inductive process that involved using the teachers’ own terminology for describing musics and activities, learning objectives, and educational foci in general.

In step two, the results of the qualitatively oriented analysis were quantified and transferred to SPSS to facilitate an investigation of relations between forms of activity, lesson contexts, and teachers’ backgrounds. The number of codes and categories developed to examine the range, variety, and characteristics of Norwegian compulsory school music activities in the inductively oriented step one increased quickly. Moreover, the examples reported in CI and CII often combined several forms of activity, for example ‘dancing/moving while listening to the rhythms’, ‘learning the guitar and singing’ and ‘learning about blues and writing their own songs’. However, because the teachers were fairly coherent when naming and describing such activities, we were able to establish a set of fifteen categories applicable to statistical analysis. These were: singing; listening; dancing; ensemble playingFootnote6; rock band playing; rhythm and classroom instruments; wind band; music history and genre theory; instrumental tuition; composing, concerts, and performances; beat, rhythm, and metre; notation; instrument theory; and student presentations. The number of examples that each teacher chose to report varied. Therefore, we applied our analyses at the level of lessons/questionnaire charts instead of the number of examples given by each teacher. Consequently, having transferred and set up the main activity categories in SPSS, we subsequently and for each respondent/teacher noted whether the respective lesson/chart included examples from the different categories.

Limitations

Although we analysed data from music teachers gathered through a purposive sample of originally 800 compulsory schools in Norway based on the public registry GSI, we do not claim any generalisations to the whole population of Norwegian music teachers from our results. In addition, we cannot claim any knowledge of the causal relationships among the variables investigated based on our statistical analyses.

Results

The fifteen activity categories we established through the first stages of analyses (see above) give a broad and overarching overview of the forms of activities that are included in Norwegian compulsory school music education. In the following, we will explore how these activities are distributed and how they are related to teacher characteristics such as competence, teaching experience, and gender through statistical analysis. Following this, we will deepen the readers’ understanding of what a select number of activities may imply and discuss in more depth what forms of participation these activities allow for. This will be done by drawing on the rich information derived from the qualitative phase of our analysis.

Distribution of activities in Norwegian compulsory school music education

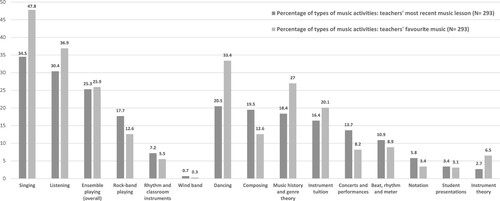

As mentioned above, the teachers were asked to give examples of music used in their most recent music lesson, as well as the music used most regularly as part of their lessons.Footnote7 In both cases, the chart allowed for information about the activities that the music was part of. As shown in , the most common activity facilitated in their last music lesson was singing, which was offered by 34.5% of the teachers (101 teachers). Other frequently offered activities were listening (by 89 teachers, 30.4%) and ensemble playing (overall) (by 74 teachers, 25.3%), within which rock band playing dominated (by 52 teachers, 17.7%). However, other performing activities such as dancing (by 60 teachers, 20.5%), composing (by 57 teachers, 19.5%), and instrumental tuition (by 48 teachers, 16.4%) were implemented to a lesser degree, as was music history and genre theory (by 54 teachers, 18.4%). Activities related to the understanding of musical elements and music theory, such as beat, rhythm, and metre (by 32 teachers, 10.9%) and notation (by 17 teachers, 5.8%), were among the least frequent activities offered in the teachers’ last lesson.

Figure 2. Types of music activities in the teachers’ most recent music lesson and used in tandem with the teachers’ favourite music: percentage of teachers (N = 293).

Looking into the activities that the teachers chose to employ with their favourite music, singing was also the most preferred activity, offered by nearly half of the teachers (140 teachers, 47.8%), along with listening (108 teachers, 36.9%) and dancing (by 98 teachers, 33.4%). Music history and genre theory (79 teachers, 27%) and ensemble playing (76 teachers, 25.9%) were also emphasised by a relatively large number of teachers, while performance-related activities, such as instrumental tuition (59 teachers, 20.1%) and composing (37 teachers, 12.6%), were preferred to a lesser degree. Further, among the teachers’ least preferred activities were beat, rhythm, and metre (by 26 teachers, 8.9%) and concerts and performances (24 teachers, 8.2%), along with instrument theory (19 teachers, 6.5%), notation (by 10 teachers, 3.4%), and facilitating student presentations (nine teachers, 3.1%).

When comparing the most common activities reported by the teachers in both charts (CI and CII), we found that some activities were offered significantly more frequently in tandem with the teachers’ favourite music, compared with the music used in the most recent music lesson. A significantly higher number of teachers reported including singing (X 2 = 23.6, df = 1, p < .001), and this was also the case with listening (X2 = 16.0, df = 1, p < .001) and instrumental tuition (X2 = 8.3 df = 1, p < .05). Likewise, some frequently reported activities used in the teachers’ most recent music lessons were preferred significantly less together with their favourite music. This concerned concerts and performances (X2 = 8.6, df = 1, p < .05).

When reporting music and activities in their most recent music lessons, the teachers also gave information about which grade/year was involved. gives an overview of how the reported activities from the teachers’ most recent music lessons were distributed at the grade level.

Table 2. Teachers’ reported music activities in their most recent music lesson: Total numbers and numbers distributed on grade level (N = 285).

Performance-related activities such as singing (X2 = 31.2, df = 3, p < .001), dancing (X2 = 19.7, df = 3, p < .001), beat, rhythm, and meter (X2 = 10.4, df = 3, p < .05), and rhythm and classroom instruments (X2 = 11.4, df = 3, p < .05) were all significantly more common in primary school Years 1–4, than in the higher grade levels. The teachers also reported doing significantly more listening (X2 = 10.5, df = 3, p < .05) and concerts and performances (X2 = 12.8, df = 3, p < .05) in primary school than in lower secondary school. Further, in lower secondary school, ensemble playing (overall) (X2 = 9.7, df = 3, p < .05) and rock band playing (X2 = 25.1, df = 3, p < .001) were significantly more frequent than in primary school. In addition, some activities, such as instrumental tuition (X2 = 8.9, df = 3, p < .05) and composing (X2 = 10.9, df = 3, p < .05), were significantly more common in primary school Years 5–7 and in lower secondary school than in the lower grades.

Looking into the relationship between the variety of activities facilitated in the teachers’ most recent music lesson and grade level, a one-way ANOVA showed that grade level also significantly affected the range of activities in the teachers’ practice (F(3, 292) = 9.4, p<.001). Independent t-tests with the number of different activities facilitated as the dependent factor show that teachers implemented a significantly higher number of different activities in primary school Years 1–4 (F(181,183) = 0.5, p <.05) and Years 5–7 (F(225,227) = 6.5, p < .05) than in lower secondary school (Years 8–10). These results indicate that students in primary school (Years 1–7) were offered a wider range of activities in their music lessons than students in lower secondary school (Years 8–10).

Summing up, across charts CI and CII, the most frequently reported activities facilitated in the music classroom were performance-related activities such as singing, listening, ensemble playing (including rock band playing), and dancing. In addition, the teachers emphasised activities such as music history and genre theory and instrumental tuition. Still, which activities were implemented differed among grade levels. For example, singing and dancing were more frequently offered during Years 1–4, listening more frequently during Years 5–7, and ensemble playing (including rock band playing) more frequently in Years 8–10 than in the other years. In addition, the range of activities facilitated in one lesson was larger in primary school than in lower secondary school.

Activities related to teacher characteristics

Investigating whether there were any differences in the teachers’ choice of activities with regard to their formal competence, we found that teachers with formal competence in music more frequently reported working with instrumental tuition in their most recent music lesson (X2 = 5.4, df = 1, p < .05) and preferred to facilitate ensemble playing (X2 = 8.3, df = 1, p < .05) – and amongst them, rock band playing (X2 = 8.4, df = 1, p < .05) – significantly more when reporting on activities employed with their favourite music. In addition, the higher their formal education in music was (from 60 to 300 ECTS credits), the more likely it was that they implemented rock band playing (X2 = 10.8, df = 4, p < .05) as part of their lessons. An analysis of variance shows that the teachers’ level of formal education also significantly affected the number of different activities included in their practice (F(4, 221) = 2.6, p < .05). Independent t-tests with the number of different activities facilitatedFootnote8 as the dependent factor, show that teachers with relatively low levels of formal education in music in their teacher training, such as 30 ECTS credits (F(127, 129) = 3.6, p < .05), facilitated a significantly higher number of activities than did teachers with 60 ECTS credits. Likewise, teachers who completed continuing educationFootnote9 in music (shorter music courses that offer a specialisation or extension of their basic education as teachers) included a significantly higher number of different activities in their practice than teachers with 60 ESTC credits (F(94,96) = 4.2, p = .05) and teachers with a bachelor degree in music (F(52,54) = 3.5, p = .05). Thus, the teachers’ level of formal competence influenced various aspects of their teaching in different ways.

The teachers were also asked about their music activities outside their teaching, and 72% (211) of them participated in such activities, either as professional (48.3%, 102 teachers) or amateur musicians (51.7%, 109 teachers). The higher their formal education in music, the more likely they were to participate in such activities as professional musicians (X2 = 66.5, df = 12, p < .001), as could be expected. Teachers who also worked as professional musicians reported more frequent facilitation of performance-related activities such as ensemble playing (X2 = 10.6, df = 3, p < .05) and rock band playing (X2 = 14.5, df = 3, p < .05) together with the music they regularly used as part of their teaching than did teachers who participated in leisure-time activities as amateur musicians.

The teachers’ competences in music seem to have some bearing on whether performance-related activities such as instrumental tuition, ensemble playing (overall), and rock band playing are implemented as part of their practice, while we did not find these connections regarding other types of music activities in our material. Nonetheless, the teachers’ level of formal education in music seems to influence the number and range of activities included. In addition, the facilitation of some activities seemed to vary with regard to the teachers’ teaching experience and gender. Singing (X2 = 11.3, df = 3, p < .05) and dancing (X2 = 12.8, df = 3, p < .05) were preferred by teachers with more than 15 years of experience teaching music. Dancing (X2 = 22.5, df = 2, p < .001) and beat, rhythm, and meter (X2 = 10.8, df = 2, p < .05) were typically facilitated by female teachers, while rock band playing (X2 = 8.6, df = 2, p < .05), instrumental tuition (X2 = 7.1, df = 2, p < .05), and composing (X2 = 8.5, df = 2, p < .05) were implemented by male teachers.

Activities and forms of participation

The format of this article does not permit us to give a full overview of the wide range of forms of participation that the activities facilitated by music teachers allow for. However, the 1865 examples of music and musical activity given by the teachers through the two questionnaire charts (described above) provide evidence of a varied and diverse music subject in Norwegian compulsory education. Moreover, they outline a situation in which, as a rule, students actively engage with musical material in their learning, producing, and constructing the learning content as they go. To some degree, the general impression of diversity and participation in the music subject stands up to analytical scrutiny. However, looking closely into the material, we also find patterns in the combination of musics and forms of participation that lead to diversity along certain recognisable paths. In the following, we trace these paths across three of the most common activities in the material: singing, ensemble playing, and listening.

With a few exceptions, singing is practiced as unison group singing. It is often accompanied by digital backing tracks produced by KorArti, which is a service similar to SingUp in the UK. Indeed, song repertoires may be chosen largely because KorArti makes them easily accessible. Solidarity, friendship, and positive self-esteem are attitudes that are expressed in school group singing activities, with songs/lyrics written for children, and on children's behalf. Group singing also celebrates community and belonging through songs dedicated to the school, the district, or the nation and rehearses the everyday routines and rituals of the curricular year. Most of the digital backing tracks made available by KorArti and similar services, regardless of original sound, are played in popular music styles. When the students sing, accompanied by their teachers or on their own (clapping or using classroom instruments such as the ukulele), children's music from the 1950s onwards, folk songs from around the world, and traditional Norwegian tunes make up the repertoire. Song, dance, and working with beat/rhythm are very likely to be combined as activities, especially in Years 1–7. In Years 8–10, singing finds its place in conjunction with forms of ensemble playing and instrument tuition, and always in popular music genres.

To communicate with an international audience, we chose the term ensemble playing to designate all forms of group music-making with instruments in the statistical analyses. However, the corresponding Norwegian term – samspill – more accurately translates to ‘playing together’ and connotes, in Norwegian music educational discourse, a collective and creative mode of educational engagement in and with music, in which the procedure of socio-musical interaction is as important as the product. The high number of questionnaire entries simply stating that samspill was the main reason for engaging with a piece of music, without going further into the details, indicates the self-evident meaning of the term for the teachers. Considering the material at large, however, we can delineate between practices where students make music together with classroom instruments in larger ensembles, and the situations where they use electric instruments in smaller or larger groups. For one thing, the teachers regularly refer to the latter as (rock) band.Footnote10 Secondly, whereas classroom instrument ensembles are led by the teacher, rock bands are regularly student-led. Third, the rock band practice uses popular music genres exclusively, while classroom-instrument ensembles play folk music, children's music, and even classical music, also with the help of digital backing tracks. It is fair to assume that rock band constitutes an important arena for learning to play the drums, bass, and electric guitar and for practicing singing in a microphone. However, this is not explicitly emphasised by the teachers in their descriptions of rock band samspill. Rather, teachers refer to such instrumental learning practices as ‘courses’ in the instrument in question: guitar (easily the most popular instrument, regardless of what year the teachers teach), ukulele (Years 5–7), or piano (Years 8–10).

In Norwegian curriculum history, listening occupies a place somewhat similar to music appreciation in the Anglo-American tradition. Listening activities entail learning about, enjoying, and conveying one's understanding of the expressive traits, structural elements, dynamic forms, and social implications/contexts of musics in speech, text, or digital presentation formats. Listening to music also seems to be enjoyed for its own sake, with no educational ambitions other than letting students take turns choosing the music they would like to hear. Nevertheless, classroom conversations are integral to musical listening and are likely to be organised around topics such as friendship, nature, society and history, or genre and style or more philosophical questions such as meaning, expression, and feelings in music. Such assignments, however, are also often approached by dancing, drawing, singing, or playing (to) the music in question, especially in primary school practices. As reported by the teachers, music history is usually studied through listening to and discussing musical expressions in classroom conversations or, in some cases, listening to and trying to play, sing, and dance in certain styles (blues, rap, or folk music). The rehearsal of already canonised musics and artists seems to be integral to telling the different histories of music. Here, teachers are likely to choose music and artists for their capacity to represent a golden age of some sort, equating exemplarity with quality and hence with educational relevance. This practice also leads to a certain bias towards white, male, Anglo-American artists in the musical material in general.

Discussion

Before we start discussing some possible answers to the last of our research questions, namely how the forms of music-related participation outlined above can be understood in relation to broader societal patterns, we will take the opportunity to comment briefly on two of the patterns in our findings related to teacher characteristics, one which is consistent with what must be said to be commonly known or expected, and one which departs from what has been found in earlier research.

With regard to activities as related to teacher gender, we note that our findings convey a quite familiar, gendered pattern of female teachers taking care of the more embodied activities, such as dance and beat, rhythm and meter (which will often be taught using the body as the main instrument), and the male teachers facilitating the traditionally masculine domains of rock band playing and composition (see e.g. Green Citation1997). The findings of Sætre, Ophus, and Neby (Citation2016) show that female teachers are more likely to work with younger children and male teachers with the lower secondary school youth, which can perhaps also partly explain this gendered difference of activities. Nevertheless, while this gendering of practices might be unfortunate, it cannot be said to be unexpected.

When it comes to the area of teacher competence, Sætre’s (Citation2018) study of 135 Norwegian music teachers showed that ‘[t]eachers with music teaching competence (which can be acquired both formally and informally) include a wider range of musical content and activities in their classes than less trained teachers’ (555). This stands, at least partly, in contrast to our findings, in which it is evident that teachers with less formal competence facilitated a higher number of activities than teachers with more ECTS credits in music. The two studies, of course, were not conducted in exactly the same way and may therefore measure slightly different phenomena, but we would still like to mention one possible reason for the differing results: Sætre's data was gathered during the school year of 2008/2009 (see Sætre, Ophus, and Neby Citation2016, 5), whereas our data was collected a good ten years later. During those ten years, we have seen an increasingly high rate of shorter courses for in-service music teachers in Norway, also in music, often directed towards teachers who originally did not have formal education in some of their teaching subjects. This approach may have worked to enhance the competence of less-trained teachers and enabled them to facilitate a richer music subject for their students. Why they facilitate a higher number of activities than their formally more competent colleagues remains to be answered. Perhaps it is in some way connected to another one of our findings, namely, the tendency of higher-educated teachers to more often prefer activities that enhance quite specialised music-related competences among their students by including more performance-oriented activities, such as instrumental tuition and ensemble playing. While a highly competent teacher can facilitate activities that require specialist competence, not least from the teacher, and work in depth with them for a long period of time, a less competent teacher may choose to employ several activities but move through them more quickly and perhaps a bit more superficially. Does this latter way of teaching make the music subject one filled with random activities in a fairly unfortunate way, or could it also be understood positively as a subject characterised by low-threshold activities that enable participation for all, much in line with the tenets of the national cultural policy and music curriculum (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020a; Meld. St. 8. Citation2018–2019)? In our opinion, both interpretations are valid, as is the insight that some of the activities might be connected to other and perhaps more elitist ways of perceiving music and music education. We elaborate on this by going back to our Bourdieusian framework.

Positioned between the fields of cultural production and education policy, formal music educational practices and institutions constitute arenas where the historical and contextual ‘specific logic’ of music as a field of cultural production and art (Bourdieu Citation1996, 220) meet political ‘influences or commissions’, such as those conveyed by a national core curriculum. Here, the ideal curriculum (Goodlad Citation1979), in the form of political intention, is refracted by its field of application, according to prevailing field logics, and through the (intentional and unintentional) effort of field actors. So are influences from other adjacent fields, such as those of commerce (which put YouTube and the iPad in the classroom), religion (through specific school rituals and song repertoires) and/or social welfare (which instigates a care for children's emotional well-being and social skills in and through music).

The sheer abundance of current and previous research studies in music education testifies to the complexity and variety of internal field logics, as well as external influences. Nevertheless, research also repeatedly identifies discourses that concur with what Bourdieu, based on his studies of French society in the 1960s, called the ‘purity’ of the music field: a dismissal of concerns not purely aesthetic/musical and a reverence for the musical expressions, practices, and performers/agents that most distinctively follow this logic (Bourdieu Citation1984). Supported by discourses of authenticity, originality, taste, specialisation, and dedication (Ellefsen Citation2014; Dyndahl and Nielsen Citation2014; Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Romer Citation1993), the logic of purity serves to secure the autonomy and legitimacy of music as a field of cultural production, as well as the importance of specialist music education and expert educators for the field. The fact that teachers with high(er) formal musical competence choose to facilitate individually oriented activities and specialist musicianship (such as that of learning an instrument and playing in a band) and are less oriented towards general, broad participatory activities (such as dancing and singing) can, in this light, be taken as an example of the curricular refraction expert educational agents in a field of cultural production exercise in service of their field's logic. These actors have devoted substantial time and energy to becoming expert players in a specific game and refracting the curriculum in accordance with the rules that keep their game pure and autonomous.

Moreover, the purity discourse might also have support with teachers with less(er) and no formal musical competence, even while intentionally facilitating low-threshold activities that do not require dedicated, specialist forms of musicianship. If we are to judge by the contemporary Norwegian debate concerning music teacher competence and the quality of their teaching (Karlsen and Nielsen Citation2021), the potential of generalist teachers to contribute to children's musical learning and experience is habitually devalued by actors in the field of music as cultural production. Interestingly, however, music teachers with less formal competence can be seen as playing the education policy-instigated game of social inclusion and broad participation better and more faithfully than their more well-educated colleagues, refracting the music subject to be ‘for everybody’ in a more convincing way. Ultimately, our findings can be connected to the much broader philosophical debate on the many and various ideologies underpinning music in school and the multiplicities of ways to operationalise the subject accordingly (see e.g. Nielsen Citation1998). Some of these ways may be more inclusive than others, and ‘the winner’ in this regard does not seem to be the specialist musicianship discourse.

Concluding remarks

Aiming to draw some implications from the above, it would be possible to instigate a debate on where and in what kinds of institutions music teacher educators should or ought to be educated, if the aim is to facilitate inclusive and socially just music education. Given our discussion: if the conservatoires or music academies are given this responsibility as sole contributors, it is likely that the music subject refracted from such an education will bear the mark of the logic of the purity of the arts with its inherent specialist and elite discourses. That is, if these institutions are not able to instil a level of reflexivity in their music teacher students which enable them not to reproduce such discourses, at least not unquestioningly. On the other hand, letting the broader teacher education institutions take care of music teacher education might perhaps lead to more inclusive approaches, but possibly also to less competent teachers in terms of actual musicianship. In Norway, music teachers are educated within a wide range of institutions, both specialist and more generalist ones. At the national level, if perhaps not at the level of each school, this might bode for an altogether quite balanced refraction of the music subject, or at least so our findings seem to indicate.

Acknowledgments

This publication is part of the research project The Social Dynamics of Musical Upbringing and Schooling in the Norwegian Welfare State (DYNAMUS).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Live Weider Ellefsen

Live Weider Ellefsen is professor of music education at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences (INN), where she teaches courses in music education, qualitative research methods, cultural studies and performance at the bachelor's, master's, and PhD levels. She is also the head of the INN research group Music Education and Cultural Studies. Ellefsen's research interests include music education, music and subjectivity, discourse theory and analysis, genre theory, and ethnographic research methods.

Sidsel Karlsen

Sidsel Karlsen is vice-principal for research and professor of music education at the Norwegian Academy of Music. Karlsen has published widely in international research journals, anthologies, and handbooks. Her research interests include, among other things, the sociology of music education, various aspects of musical gentrification, and cultural diversity in music education. She is co-editor of the recent books Musical Gentrification: Popular Music, Distinction and Social Mobility (Routledge) as well as The Politics of Diversity in Music Education (Springer).

Siw Graabræk Nielsen

Siw Graabræk Nielsen is professor of music education at the Norwegian Academy of Music, Oslo, where she co-heads the Centre of Educational Research in Music (CERM). Nielsen has been co-editing the journal Nordic Network of Research in Music Education – Yearbook for over 10 years and has led the network for several years. She has published in several Scandinavian and international research journals on the academisation of popular music in higher music education, the self-regulated learning of musicians and the sociology of music education.

Notes

1 The project The Social Dynamics of Musical Upbringing and Schooling in the Norwegian Welfare State (DYNAMUS) is supported by the Research Council of Norway (2018–2022; see DYNAMUS, Citationn.d.). Earlier research within the same sub-study include Nielsen and Karlsen (Citation2021), Ellefsen (Citation2021, Citation2022).

2 The study was conducted by Live Weider Ellefsen (project leader), Sidsel Karlsen, Siw Graabræk Nielsen and Odd Skårberg.

3 In Norwegian compulsory education, music is currently taught throughout Years 1–10, with the total number of 60-minute teaching hours amounting to 368 (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020c).

4 As a point of departure for the sampling, we used the number of counties existing in Norway during 2018/2019, which included a total of 423 municipalities.

5 We were unfortunately not able to collect the official e-mail addresses of the music teachers at all of the 800 selected schools.

6 The category of ensemble playing is an overarching category which contains the subcategories of rock band playing, rhythm and classroom instruments, and wind band. When describing the results below, we have made clear distinctions between the different levels of categories in this area.

7 In the following, the music used most regularly as part of the lessons will be referred to as the teachers’ ‘favourite music’.

8 That is, activities facilitated in their most recent music lesson.

9 By continuing education, we mean exam-oriented studies/subjects that provide formal competence and credit scoring in degrees. A continuing education will often be a specialisation/extension of a basic education at university.

10 In the context of Norwegian primary and secondary music education, ‘band’ usually refers to smaller ensembles of students playing electrical instruments together in a variety of pop and rock music styles. Since Western music education commonly also uses the term ‘band’ for wind bands and/or marching bands, we use ‘rock band’ in the following to avoid confusion.

References

- Anttila, Mikko. 2010. “Problems with School Music in Finland.” British Journal of Music Education 27 (3): 241–253. doi:10.1017/S0265051710000215.

- Bates, Vincent C. 2012. “Social Class and School Music.” Music Educators Journal 98 (4): 33–37. doi:10.1177/0027432112442944.

- Benedict, Cathy, Patrick Schmidt, Gary Spruce, and Paul Woodford, eds. 2015. The Oxford Handbook of Social Justice in Music Education. New York: Oxford Academic.

- Bennett, Tony, Mike Savage, Elizabeth B. Silva, Alan Warde, Modesto Gayo-Cal, and David Wright. 2009. Culture, Class, Distinction. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bouij, Christer. 1999. “Att bli musiklärare – en socialisationsprocess” [To Become Music Teachers – A Process of Socialization]. In Nordisk musikkpedagogisk forskning: Årbok 3, edited by Frede V. Nielsen, Sture Brändstrøm, Harald Jørgensen, and Bengt Olsson, 77–90. Oslo: Norwegian Academy of Music.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Burnard, Pamela, Ylva Hofvander Trulsson, and Johan Söderman, eds. 2015. Bourdieu and the Sociology of Music Education. Surrey: Ashgate.

- Christophersen, Catharina, Kristin Iversen, and Martin Tvedt. 2017. Kunstfaga i grunnskolen i Hordaland – Tilstand og utfordringar i 2016 [Art as Subjects in Primary and Upper Secondary School – Status and Challenges in 2016]. https://docplayer.me/48091522-Kunstfaga-i-grunnskulen-i-hordaland-tilstand-og-utfordringar-i-2016.html

- Crossley, Nick. 2015. “Music Worlds and Body Techniques: On the Embodiment of Musicking.” Cultural Sociology 9 (4): 471–492. doi:10.1177/1749975515576585.

- De Vaus, David. 2013. Surveys in Social Research. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dobrowen, Laura. 2020. “Musikk på barnetrinnet: En studie av læreres forståelser av profesjonalitet i musikkundervisning” [Music in Primary School: A Study of Teachers’ Experiences of Professionalism in Music Education]. Doctoral thesis, Norwegian Academy of Music.

- DYNAMUS. n.d. Project Web Site. https://eng.inn.no/project-sites/dynamus.

- Dyndahl, Petter, Sidsel Karlsen, and Ruth Wright, eds. 2021. Musical Gentrification: Popular Music, Distinction and Social Mobility. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dyndahl, Petter, and Siw G. Nielsen. 2014. “Shifting Authenticities in Scandinavian Music Education.” Music Education Research 16 (1): 105–118. doi:10.1080/14613808.2013.847075.

- Eerola, Päivi-Sisko, and Tuomas Eerola. 2014. “Extended Music Education Enhances the Quality of School Life.” Music Education Research 16 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1080/14613808.2013.829428.

- Ellefsen, L. W. 2014. “Negotiating Musicianship. The Constitution of Student Subjectivities in and through Discursive Practices of Musicianship in “Musikklinja”.” PhD thesis, NMH-publikasjoner, Oslo.

- Ellefsen, L. 2021. “Sjangring som musikkdidaktisk praksis.” Nordic Research in Music Education 2 (2): 126–148. doi:10.23865/nrme.v2.2811.

- Ellefsen, L. W. 2022. “Genre and Genring in Music Education.” Action, Criticism and Theory for Music Education. doi:10.22176/act21.1.56.

- Ericsson, K. Anders, Ralf T. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Romer. 1993. “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance.” Psychological Review 100 (3): 363–406. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363.

- Espeland, Magne I. 2021. “Music Education as Craft: Reframing a Rationale.” In Music Education as Craft: Reframing Theories and Practices, edited by Kari Holdhus, Regina Murphy, and Magne I. Espeland, 219–239. Springer.

- Espeland, Magne, Trond Egil Arnesen, Ingrid A. Grønsdal, Asle Holthe, Kjetil Sømoe, Hege Wergedahl, and Helga Aadland. 2013. Skolefagsundersøkelsen 2011. Praktiske og estetiske fag på barnesteget i norsk grunnskule [The Report of Subjects in Primary and Upper Secondary School 2011]. https://hvlopen.brage.unit.no/hvlopen-xmlui/handle/11250/152148.

- Faber, Stine T., Annick Prieur, Lennart Rosenlund, and Jacob Skjøtt-Larsen. 2012. Det skjulte klassesamfund [The Hidden Class Society]. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Goodlad, John I. 1979. Curriculum Inquiry: The Study of Curriculum Practice. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Gould, Elisabeth. 2007. “Social Justice in Music Education: The Problematic of Democracy.” Music Education Research 9 (2): 229–240. doi:10.1080/14613800701384359.

- Green, Lucy. 1997. Music, Gender, Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hess, Juliet. 2019. Music Education for Social Change. Constructing an Activist Music Education. New York: Routledge.

- Holdhus, Kari, Regina Murphy and Magne I. Espeland, eds. 2021. Music Education as Craft: Reframing Theories and Practices. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-67704-6.

- Kallio, Alexis A. 2015. “Navigating (Un)Popular Music in the Classroom: Censure and Censorship in an Inclusive, Democratic Music Education.” Doctoral thesis. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-329-014-3.

- Karlsen, Sidsel, and Geir Johansen. 2019. “Assessment and the Dilemmas of a Multi-Ideological Curriculum: The Case of Norway.” In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophical and Qualitative Assessment in Music Education, edited by David J. Elliott, Marissa Silverman, and Gary McPherson, 447–463. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Karlsen, Sidsel, and Siw G. Nielsen. 2021. “The Case of Norway: A Microcosm of Global Issues in Music Teacher Professional Development.” Arts Education Policy Review 122 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1080/10632913.2020.174614.

- Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. 2017. “Revisiting Bildung and Its Meaning for International Music Education Policy.” In Policy and the Political Life of Music Education, edited by Patrick Schmidt, and Richard Colwell, 107–122. New York: Oxford Academic. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190246143.003.0007.

- Lamont, Alexandra, David J. Hargreaves, Nigel A. Marshall, and Mark Tarrant. 2003. “Young People’s Music in and out of School.” British Journal of Music Education 20 (3): 229–241. doi:10.1017/S0265051703005412.

- Meld. St. 8. 2018–2019. “Kulturens kraft: Kulturpolitikk for framtida” [The Power of Culture: Cultural Policy for the Future]. Ministry of Culture. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-8-20182019/id2620206/.

- Moore, Gwen. 2012. “Tristan Chords and Random Scores: Exploring Undergraduate Students’ Experiences of Music in Higher Education Through the Lens of Bourdieu.” Music Education Research 14 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1080/14613808.2012.657164.

- Nielsen, Frede V. 1998. Almen musikdidaktik [General Music Didactics]. 2nd ed.. København: Akademisk Forlag.

- Nielsen, Siw G., and Sidsel Karlsen. 2021. “Grunnskolelærere i musikk og deres kompetanse: Hvordan er situasjonen i norsk kontekst?” Nordic Research in Music Education 2 (2): 100–125. doi:10.23865/nrme.v2.2840.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2020a. “Core Curriculum—Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education.” https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2020b. “Læreplan i musikk.” [Music Curriculum]. https://www.udir.no/lk20/mus01-02.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2020c. “Musikk (MUS01-02), Timetall” [Music (MUS01-02), Teaching Hours]. https://www.udir.no/lk20/mus01-02/timetall

- Perlic, Biljana. 2019. Lærerkompetanse i grunnskolen: Hovedresultater 2018/2019 [Teacher Competence in Primary and Lower Secondary School: Main Results 2018/2019]. Rapporter 2019/18. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

- Peterson, Richard A. 1992. “Understanding Audience Segmentation: From Elite and Mass to Omnivore and Univore.” Poetics 21 (4): 243–258. doi:10.1016/0304-422X(92)90008-Q.

- Schmidt, Patrick. 2013. “Cosmopolitanism and Policy: A Pedagogical Framework for Global Issues in Music Education.” Arts Education Policy Review 114 (3): 103–111. doi:10.1080/10632913.2013.803410.

- Sepp, Anu, Inkeri Ruokonen, and Heikki Ruismäki. 2015. “Musical Practices and Methods in Music Lessons: A Comparative Study of Estonian and Finnish General Music Education.” Music Education Research 17 (3): 340–358. doi:10.1080/14613808.2014.902433.

- Sætre, Jon Helge. 2018. “Why School Music Teachers Teach the Way They Do: A Search for Statistical Regularities.” Music Education Research 20 (5): 546–559. doi:10.1080/14613808.2018.1433149.

- Sætre, Jon Helge, Tone Ophus, and Thor Bjørn Neby. 2016. ““Musikkfaget i norsk grunnskole: Læreres kompetanse og valg av undervisningsinnhold i musikk” [The Music Subject in Norwegian Compulsory School: Teachers’ Competence and Choice of Educational Content]. Acta Didactica Norge 10 (3). https://journals.uio.no/adno/article/view/2876/3272.

- United Nations. n.d. “Sustainable Development Goals.” https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

- Wright, Ruth. 2008. “Kicking the Habitus: Power, Culture and Pedagogy in the Secondary School Music Curriculum.” Music Education Research 10 (3): 389–402. doi:10.1080/14613800802280134.

- Wright, Ruth, ed. 2010. Sociology and Music Education. London: Routledge.