ABSTRACT

In this paper, the ‘guidelines for strategic environmental assessment (SEA) of nuclear power programmes’ by the International Atomic Energy Agency are introduced. This includes a reflection on their preparation process and contents as well as consultation feedback. The preparation process started with two meetings of international nuclear and SEA experts and the creation of a writing team which prepared an initial set of draft guidelines. This was followed by various consultation exercises. The guidelines are organised along an allocation of tasks within a tiered system of energy related policies, plans, programmes and projects. Whilst consultation showed that there was agreement on the approach to most issues, no consensus was present on the extent to which economic and social issues should be fully integrated with environmental considerations. Strong support was given to the way quality review is designed, going beyond focusing on the main SEA reports to cover procedural and participatory aspects next to elements of a comprehensively tiered decision making framework, the ability to influence decisions as well as the quality (expertise and experience) of those involved in conducting the SEA.

Abbreviation: SEA: Strategic Environmental Assessment; EIA: Environmental Impact Assessment; IAEA: International Atomic Energy Agency

Introduction

Numerous guidelines for the preparation of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) have been released over the past two decades in various jurisdictions internationally and nationally, covering a range of sectors and applications (see e.g. EC Citation2001; Government of Ireland Citation2004; Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Citation2004; Environmental Protection Department Citation2005; OECD DAC Citation2006; UNECE Citation2007; Naturvardsverket Citation2010). These are likely to have informed thousands of SEAs (Fischer Citation2007a), thus playing a key role in the development of SEA. However, despite their importance, to date, only few authors have reflected on guidelines and their preparation processes and there are only few associated publications (Fischer and Onyango Citation2012). In this context, there is one descriptive account of what SEA guidelines cover and what they look like (Therivel et al. Citation2004). Furthermore, there are a few analytical studies of published guidelines with regard to the issues and aspects raised in them (Kørnøv Citation2009; Noble et al. Citation2012; De Montis et al. Citation2016). However, to date there have not been any published accounts of preparation processes and on the associated feedback obtained.

With this paper, we aim at addressing this gap by reflecting on the guidelines for SEA of nuclear power programmes of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA Citation2018), their preparation process and contents as well as the results of the associated expert consultation. The IAEA is an autonomous international organization which was established in 1957 and which reports to the United Nations General Assembly and Security Council. Its main goal is the promotion of the safe, secure and peaceful use of nuclear technologies. Through safeguards the IAEA verifies that states obey their international legal obligations to use nuclear material and technology only for peaceful purposes. The IAEA further promotes nuclear safety and security, e.g. through the establishment of nuclear safety standards and nuclear security guidelines. The IAEA also functions as an intergovernmental forum for international scientific and technical co-operation.

It is within this wider context that the initiative for preparing guidelines on SEA was taken by IAEA’s Planning and Economic Studies Section in 2015. Up to that point, the IAEA had released many documents to support countries in exploring nuclear power as an option, such as on ‘Milestones in the Development of a National Infrastructure for Nuclear Power’ (IAEA Citation2015), on how to launch a nuclear power programme (IAEA Citation2007) or on the management of project EIA aimed at construction and operation phases (IAEA Citation2014). However, SEA guidelines had not been prepared. Whilst SEA is widely applied in general, only few SEAs have been performed for nuclear power programmes. Related existing cases mostly focus on the components of a nuclear power programme, such as spent fuel management strategies. Thus, the IAEA felt it was time to take a lead on establishing what a nuclear power programme SEA should look like. The main aim of the guidelines is to provide support to those countries that wish to apply SEA at the programme level.

The guidelines for SEA of nuclear power programmes were prepared over a period of 20 months in 2016 and 2017 and were formally published in 2018. Two expert group meetings were at the heart of the initial decisions on content and structure of the guidelines as well as on the review of an initial draft, which was prepared by a writing team from within the expert group. The expert group included nine environmental assessment and nuclear energy experts. Two of those were from the IAEA, three represented academic institutions, two government bodies and two practitioners from consultant companies. Contributors were from institutions based in Kenya, Pakistan, Colombia, Poland, Croatia, the UK and Austria.

In addition to the two expert group meetings and the activities of the writing team, a review process of a full draft of the guidelines was organised by the IAEA, involving IAEA internal as well as other international experts. In the first round of consultation, 28 international SEA experts were contacted. Sixteen responses were received, of which 11 provided for some detailed feedback and comments on the guidelines. Furthermore, comments were also obtained from five IAEA internal experts. Each individual comment was reflected upon; responses were recorded and discussed among the expert team. Second, a dedicated session on a revised set of draft guidelines was held at the IAIA2017 annual meeting in Montreal. In this context, the draft was sent out to 20 session participants. Comments subsequently received were also included in a further revision of the guidelines. In addition, the IAIA2017 session enabled a wider discussion amongst the attending SEA experts on SEA guidelines in general. A third round of feedback took place during a training session on the final draft guidelines in November 2017, which was attended by 20 nuclear and other energy experts and planners from 20 countries. shows the timeline and stages of the guidelines preparation process.

The main reason for focusing on the programme level was that up until the decision to prepare SEA guidelines, national endeavours for developing nuclear energy that involved SEA revolved around the preparation of nuclear programmes (Paul C Rizzo Associates Citation2010; Ekovert Citation2014; Öko-Institut Citation2015). It was therefore at this level where the need to prepare guidelines was perceived as the most urgent.

With regard to the preparation process of the guidelines, the original concept was developed by the IAEA in-house. At the first expert meeting in March 2016, the preparation process and contents of the guidelines were discussed. Tasks for the preparation of draft chapters were allocated to various members of the expert group, which formed a writing team. Draft chapters were reviewed in the run-up to the second expert meeting. Comments on the draft guidelines were discussed at that meeting in September 2016 and a work plan was prepared for a second draft and for an associated consultation process. This was conducted as outlined above.

Subsequently, first the SEA guidelines are introduced, focusing on the overall approach taken as well as the substantive content produced. This is followed by a summary of comments and feedback received by those responding to the invitation to comment, comprising experts in environmental assessment/management as well as nuclear energy experts and engineers. Subsequently, an explanation is given on how comments informed the guidelines. In this context, incompatibilities of some comments received are also highlighted. Finally, results are reflected on and conclusions are drawn.

Content of the guidelines

In a foreword to the guidelines, the overall aim of SEA is explained and the benefits of applying SEA are introduced (based on Dusik et al. Citation2003). Furthermore, the reasons for preparing the guidelines are provided. Their main aim is said to ‘provide support to responsible authorities and stakeholders worldwide who are engaged in SEA for Nuclear Power Programmes’. This is followed by an outline of the approach taken, explaining that the guidelines go beyond the minimum requirements found in most existing legislation, reflecting international good practices. This is seen to be of particular importance in a sector which is perceived to be of high sensitivity (nuclear energy is often subject to some strong – and diverging – public opinions; see e.g. Pampel Citation2011; Novikau Citation2016), potentially giving rise to various controversies.

At the beginning of the guidelines a summary is provided of six key issues for SEA for nuclear power programmes. These are dealt with in more depth in the main body, with each having a dedicated chapter: (1) the context within which SEA is applied, (2) substantive issues to be considered in a nuclear power programme SEA, (3) the assessment process to be applied, (4) stakeholder engagement, (5) assessment methods and associated data requirements, as well as (6) the content and format of the SEA report. The main body of the guidelines is presented in eight chapters on around 75 A4 pages. Limiting the length of the guidelines was seen to be of key importance in the interest of clarity and conciseness.

The guidelines are connected with a range of other documents released by the IAEA. Most importantly, these include the ‘Milestones in the Development of a National Infrastructure for Nuclear Power’ (IAEA Citation2015). Within this document, three phases are introduced for developing nuclear power. SEA for nuclear power programmes is positioned within these phases. Furthermore, 19 infrastructure issues in the development of nuclear power are introduced. These are taken as reference points when defining impact areas to be considered in nuclear power programme SEA.

Context within which SEA for nuclear power programmes is prepared

Subject to national legislative frameworks, SEA would normally be conducted when a Nuclear Power Programme is being developed. This should build on prior national energy strategies, policies and associated plans and SEA should also be applied to those. A nuclear power programme SEA will provide the framework for subsequent projects and their associated EIAs, when e.g. nuclear facilities are to be constructed, such as power plants or spent fuel storage.

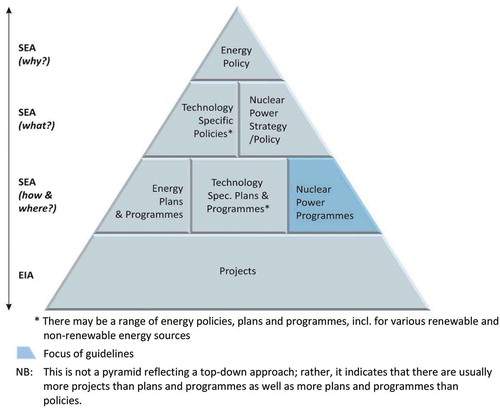

The content of an SEA for a Nuclear Power Programme will ultimately depend on what is covered in earlier policy and plan SEAs. This is similar to what has been described for other sectors (see e.g. Fischer Citation2006 for transport; Therivel Citation2004 for spatial planning). Furthermore, it will likely be informed by related EIAs. A systematic approach to the development of nuclear energy means higher-level SEAs for energy strategies, policies and plans would focus on issues such as overall energy needs, the energy mix and within this, the role of nuclear energy. presents the conceptual model behind this systematic approach, depicting possible energy decision tiers (following Jansson Citation2000; Fischer Citation2000). Different questions would be asked and specific tasks would be fulfilled at each tier. The position of the guidelines within the overall framework is also depicted.

Figure 2. Energy decision tiers and position of the guidelines in the decision hierarchy.

* There may be a range of energy policies, plans and programmes, incl. for various renewable and non-renewable energy sources.NB: This is not a pyramid reflecting a top-down approach; rather, it indicates that there are usually more projects than plans and programmes as well as more plans and programmes than policies. Source:IAEA Citation2018.

As stated above, this is the first set of guidelines released by the IAEA on SEA. Whilst there are guidelines for specific energy plans released in national contexts (e.g. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Citation2013; see also Stockholm Institute Citation2001), there are none available for nuclear related policies and plans. Subsequently, in the guidelines, questions are asked at various points on what issues had been addressed upfront in policies and plans and their associated SEAs. This approach allows to identify any gaps with regard to issues that should have been but are not addressed prior to the programme SEA. Addressing all of these gaps may go well beyond the scope of a programme SEA. In any case, content and shape of the nuclear power programme SEA will differ in different situations, depending on national requirements and existing related assessments.

An important starting point for the IAEA was that it did not aim at providing guidance on whether or not to develop nuclear energy, i.e. addressing the question as to why nuclear energy could be an option. Furthermore, no particular formal approach was to be followed. Instead, the guidelines are set-up to reflect good practice.

Once a decision has been made that nuclear power could play a role in meeting energy needs (the top triangle in ),Footnote1 a nuclear power strategy or policy should be prepared, next to associated strategies and policies of other energy areas. This would be followed by the preparation of a nuclear power programme and its associated SEA. Subsequent EIAs would then focus on the implementation details at the project level. In this context, it is important that each SEA and related EIA are tiered and closely connect with each other and focus on the specific issues and tasks relevant for their respective levels.

Environmental and related sustainability issues

For SEA to work effectively in this sector, it needs to address environmental and related sustainability issues relevant to a nuclear power programme. In this context, the guidelines consider three categories of potential impacts to be of main importance: (a) safety considerations, (b) nuclear power impact areas and (c) environmental impact themes. These categories are closely connected with the approach applied by the IAEA in other situations. The way these are approached in the guidelines was agreed upon during the first expert meeting. No comments were made on these three categories by any of those consulted during the review process.

Any nuclear power programme will need to be accompanied by a nuclear safety assessment. This is standard practice when developing nuclear energy. It is not SEA’s aim to replace these, but rather to investigate any associated impacts on any of the environmental impact themes. This is why safety issues are covered on one page only in the guidelines, referring to a number of relevant IAEA safety standards. These include standards on seismic hazards (IAEA Citation2010), meteorological and hydrological hazards (IAEA Citation2011), external human induced events (IAEA Citation2002a) and dispersion of radioactive material in air and water, and considering population distribution in site evaluations (IAEA Citation2002b), safe transport of radioactive material (IAEA Citation2012a), control of radioactive discharges (IAEA Citation2000) and options for management of spent fuel and radioactive waste (IAEA Citation2013). Overall, the IAEA has published about 130 safety standards and there is a need for consistency.

Next, seven nuclear power impact areas are introduced that should be considered for their relevance to a specific SEA for a nuclear power programme:

Main siting and technological considerations;

Power plant construction, operation and decommissioning;

Nuclear fuel cycle;

Spent fuel management strategy/radioactive waste storage and disposal;

Physical protection and security;

Emergency preparedness and response;

Increased physical infrastructure requirements.

These areas were agreed on during the first and second expert meeting. As explained above, the starting points were existing IAEA documents such as IAEA (Citation2015). Whilst all impact areas were discussed during the expert meeting with regard to what issues are and what are not relevant, one of them, namely area (3) ‘nuclear fuel cycle’, was subject to some more extensive debate, in particular as in many countries associated steps would be happening outside national boundaries (see ). Whilst all stages of the nuclear fuel cycle should receive some attention in any SEA for a nuclear power programme, the depth and detail with which this is happening may vary for different stages, depending on e.g. what may already be covered in a separate assessment and/or in a different country. Only those steps of the fuel cycle that will be dealt with nationally are considered as fully applicable for a nationally conducted SEA.

Figure 3. Nuclear fuel cycle (IAEA, Citation2012b).

In the guidelines, the seven nuclear power impact areas are associated with eight environmental impact themes. These are supposed to be used to guide the assessment across impact areas and include:

Ground, air, water, soil;

Radiological and non-radiological emissions, noise and vibration;

Land use, landscape, cultural heritage;

Ecosystems;

Climate change;

Public health, well-being and safety;

Economy (in connection with environmental implications) and society;

Natural hazards.

A conscious attempt was made to pick impact themes that are able to reflect as closely as possible existing legislation (e.g. the European SEA Directive) and practices. However, as the guidelines are written for an international audience, thus working within different legislative frameworks, impact themes will need to be adjusted to best fit the local context SEA is applied in. It is also important that it is not only impacts on, but also impacts from impact themes that need to be considered in SEA, e.g. natural hazards or climate change (both mitigation and adaptation, see e.g. Jiricka et al. Citation2016, Citation2018). In the guidelines, assessment questions are formulated for each impact theme to guide practitioners. provides an overview of selected questions asked.

Table 1. Selected questions for SEAs for nuclear power programmes.

SEA process

The assessment process is conducted in parallel to the preparation of the nuclear power programme. This process is likely to take at least 6 months and may require one or more years to complete for something as complex and also, at least potentially, controversial as a nuclear power programme. The process needs to start as early as possible, ideally immediately after a decision has been made to prepare a nuclear power programme. The SEA process introduced in the guidelines follows a ‘standard’ process, which is reflected in many jurisdictions globally.

The first component would normally be screening, looking at the likelihood of any significant environmental and related sustainability impacts. As mentioned earlier, as a principle, SEA would always be expected to be conducted for a nuclear power programme. A possible exception may be minor changes being proposed to existing infrastructure. In case SEA is legally mandated for a nuclear power programme, no further screening would be necessary.

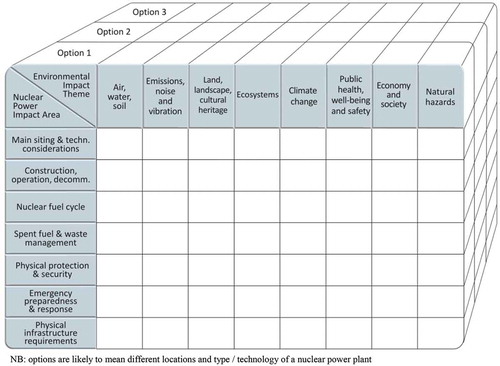

Next, during scoping, the environmental and related social and economic issues are identified, along with options for avoiding, reducing or mitigating significant negative environmental impacts and for enhancing positive outcomes. A scoping matrix should be prepared, as proposed by .

Figure 4. Scoping matrix.

NB: options are likely to mean different locations and type/technology of a nuclear power plantSource:IAEA Citation2018.

Stakeholder engagement and public participation is more than a stage, but rather a component that should be conducted at least at scoping and SEA report preparation stages. They may include transboundary consultations in other affected countries. Stakeholder engagement and public participation are introduced in more depth in a dedicated section in the guidelines. Furthermore, there may be specific requirements, depending on the national context. The following box outlines the elements of adequate stakeholder engagement and public participation ().

BOX 1. Elements of adequate stakeholder engagement and public participation.

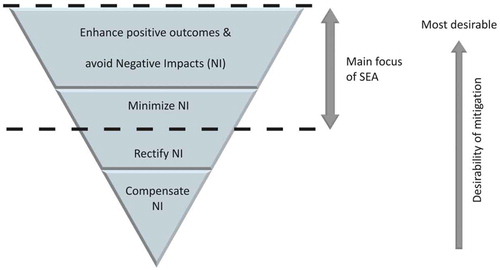

The actual assessment involves the application of suitable methods and techniques for evaluating options within the nuclear power programme, with regard to their environmental and related sustainability impacts, both, negative and positive. The associated evaluation should establish the potential impact significance and should identify associated mitigation measures. In this context, the main focus of mitigation should be on enhancing positive outcomes and avoiding negative impacts, or to minimize them (see ).

Figure 5. Desirability of different types of mitigation measures in SEA.

Source:IAEA Citation2018.

A SEA report is the main written output of the SEA process. It should describe the assessment and elaborate on the identified impacts as well as on any associated mitigation measures. The SEA report should serve as one of the key inputs for consultation and participation as well as decision making. What a nuclear power programme SEA report should look like and cover is introduced in further detail in a dedicated section in the guidelines.

Approving the SEA report and explaining how the SEA process overall has influenced the nuclear power programme is essential in order to understand what difference SEA has made in decision making. Furthermore, subsequent developments need to be monitored in the light of what the SEA is proposing, once a decision to proceed with a nuclear power programme is taken. There should be scope for wider follow-up, including for adaptive action in case of any unexpected impacts occurring.

Quality review takes an important position in the guidelines, focusing on the quality of different SEA components (i.e. not just the SEA report). In the guidelines, six main components are introduced, revolving around the decision framework, the SEA process, human resources, an ability to enable open and fair debates and to influence decisions, as well as the quality of the main SEA report. summarises these six components of nuclear power programme SEA quality review.

BOX 2. Components of nuclear power programme SEA quality review.

Stakeholder engagement and public participation

Stakeholder engagement, including public participation is elaborated on in a dedicated section in the guidelines. Given the time frame from the initial concept to the implementation of a nuclear power programme, it is important to consider whether and how the public and decision makers will change over time. In the interest of intergenerational equity, there is a particular need to reach out to the younger generation as it is them that will live with the proposed development long term. The IAEA considers five main principles for adequate stakeholder engagement and public participation in SEA (see also e.g. Gauthier et al. Citation2011; Aschemann et al. Citation2016):

Clear rules;

Early engagement and continuity of engagement process;

Comprehensiveness and inclusiveness;

Respect for the general good and interest;

Integrity, openness and responsiveness.

In addition to these five principles, the guidelines use five main elements that describe what adequate stakeholder engagement and public participation should result in:

Developing a common understanding;

Developing mutual trust;

Developing an enhanced acceptance;

Strengthening civil society;

Reconciling diverging views.

A variety of methods should be used in order to enable adequate stakeholder engagement and public participation in different situations of application at international, national, regional and local levels. An overall stakeholder engagement and public participation plan and communication strategy should be developed from the onset. It is important that engagement needs to be adjusted to individual groups, from communities (including indigenous communities and minority groups) to institutions and the press/media.

Assessment methods and data requirements

SEA for nuclear power programmes can involve the application of numerous methods during the various stages of the SEA process. In this context, it is important that SEA should always use a combination of methods. In the guidelines, it is stressed that the outcome of one method cannot replace the outcome of the SEA process overall. The guidelines suggest that a selection of the following 11 methods may be particularly useful (following Belcakova Citation2008; Canter Citation1998; Fischer Citation2007b):

Literature and document reviews and analogues;

Checklists;

Indicators;

Matrices;

Networks;

Multi-criteria analysis;

Environmental cost-benefit analysis;

Risk assessment;

Overlay mapping;

Expert opinions;

Modelling and scenario analysis.

While these methods are also commonly used in EIA, in SEA for nuclear power programmes they will need to be applied more strategically, which is likely to mean they will be less detailed and uncertainty will be higher.

Content and format of the SEA report

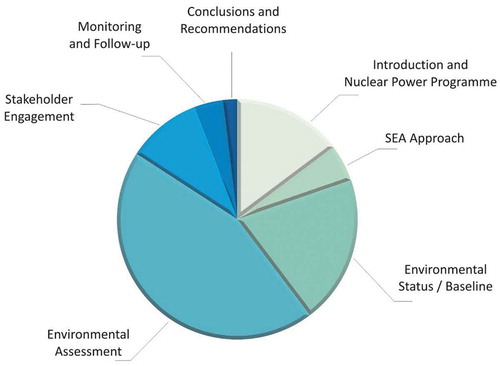

The SEA report is the main document produced during an SEA process, which can be reviewed by all stakeholders, including the general public. It describes the environmental impacts of a nuclear power programme, referring to the different options identified in SEA. In the guidelines, it is suggested that the SEA report should cover nine main parts:

Non-technical summary;

Introduction and background;

A description of the Nuclear Power Programme;

A description of the SEA approach;

Environmental status/baseline;

Environmental assessment (radiological and non-radiological aspects);

Stakeholder engagement and public participation;

Monitoring, evaluation and follow-up recommendations;

Conclusions and recommendations, including next steps.

The SEA report needs to focus on those issues relevant for the expected significant environmental impacts of the different nuclear power programme options. It needs to be written in a way that decision makers, stakeholders and the general public are enabled to understand it. Furthermore, it needs to be accompanied by a distribution strategy, where transboundary stakeholders are also taken into account. To help ensure a balanced report, the guidelines include an indicative overview of the share of each of the main parts of the SEA report (). This is important as in practice there is a tendency to put a lot of emphasis on the description of the environmental status and baseline (see e.g. Fischer Citation2010), often without focusing on those aspects that are likely to be significantly affected. Thus, often a lot less space given to other parts, in particular the analysis and evaluation (see e.g. Scottish Environment Protection Agency Citation2011; Therivel and Fischer Citation2012). Overall, it is recommended that the report should aim at having not more than 500 pages, with an additional non-technical summary of not more than 10 pages.

Figure 6. Parts and emphasis of a nuclear power programme SEA report (excl. annexes).

Source:IAEA Citation2018.

Consultation feedback on draft guidelines

In the initial round of consultation, written feedback on the draft SEA guidelines was obtained from 16 individuals, including 11 external SEA experts and 5 IAEA internal experts. Experts were approached, based on their work in the field of SEA as identified in the literature review or through recommendations from experts. The 11 external SEA experts included four representatives of international institutions (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and European Commission), two academics from the UK and Brazil, three representatives from international consultancies, one representative of an NGO and one representative each, of a national environment authority and energy authority. As explained above, further comments were received from participants of a dedicated session on the guidelines at IAIA17 in Montreal as well as from participants of an IAEA training workshop in November 2017.

Comments received fall into four main categories and range from general suggestions and endorsements over conflicting suggestions to comments that indicate a different understanding to the basic approach to SEA. Comments are subsequently summarised and discussed with regard to these categories.

General suggestions which were subsequently included in the guidelines

With regard to the purpose of the guidelines, several of those commenting suggested that SEA needed to be portrayed as a tool which aims at achieving a high level of environmental protection. In this context, some mentioned that SEA should aim to act as a ‘critical friendFootnote2’. Also, with SEA having been developed more recently than EIA, it was suggested that it is important to state that there was a lack of experiences, particularly in the nuclear energy field.

With regard to supporting the development of effective SEA, it was suggested that there was a particular need to develop institutional capacity. In this context, a number of comments were provided on how to support stakeholder engagement and public participation. One reviewer suggested that the role of stakeholder committees should be considered, in particular with regard to nuclear waste management. The aim of those would be to collect input and feedback from stakeholder groups and the general public, and to make suggestions on how these may be addressed in SEA and in the nuclear power programme. Stakeholder involvement should happen as early as possible, and in this context should include transboundary consultations. It was also suggested that when preparing nuclear power programmes, wider political buy-in was crucial, for both, the programme and the SEA preparation processes.

Whilst overall, the assessment process presented in the guidelines was supported by the reviewers, they stressed that specific national requirements (e.g. on screening and scoping) would needed to be followed. Also, public participation should not be presented as a procedural stage, but rather as a component to be addressed throughout the SEA process. Subsequently, the term ‘components’ rather than ‘steps’ was used in the guidelines, to avoid the impression of a strictly linear, task-by-task process.

A number of comments focused on methodological issues. It was suggested that clear linkages with sustainable development objectives should be established. There was a particular concern with regard to the consideration of existing infrastructure in SEA in that its inclusion should not be used for justifying certain ‘predetermined’ options. It was also suggested that next to including a process management checklist in the guidelines, the use of risk assessment should be considered. Furthermore, the need to consider the necessity to conduct EIA at the decommissioning stage was stressed.

Finally, it was suggested that other existing guidelines and relevant documents should receive a more prominent mentioning, in particular those associated with international agreements. In this context, the SEA ‘Kiev’ protocol to the Espoo Convention and documents of the OECD SEA task force were explicitly referred to.

Endorsements of specific aspects in the guidelines

Certain elements in the guidelines obtained explicit endorsement. These include the tiered approach to decision making. Furthermore, reviewers noted that frequently existing guidelines were either too specific or too unspecific and that the guidelines were striking a good balance with regard to this challenge. In this context, how the guidelines approached the question as to what issues to address when and where in the decision making hierarchy and the need to summarise important outcomes from earlier policies, plans and assessments was found to be particularly useful.

The transparency that can be achieved in the decision making process when following the guidelines was another aspect that was commented on positively. In this context, the recommendation that methods should always be applied in a transparent way was welcomed. With regard to SEA procedural aspects, the quality review sections were seen as being of key importance, and here the breadth of the topics covered was seen as being of particular importance, including the quality of the process and its role within the wider decision making framework.

Whilst a requirement in many SEA systems, it was still seen as important that the guidelines underlined the need for considering cumulative impacts, as there was a perception that in practice this was lacking. The importance to consider local and traditional knowledge was also deemed important. With regard to the consideration of health, one reviewer stressed the importance of including mental health aspects and the need to comprehensively consult health authorities.

Conflicting suggestions

A few of the suggestions made by those consulted were conflicting. These included in particular comments on whether:

there should be an exclusive focus on environmental considerations,

the nuclear fuel cycle approach adopted was suitable and

the overall level of detail pursued in the guidelines was appropriate.

While some suggested that SEA should focus on environmental issues only, others thought it is vital that economic and social issues were also considered. However, it appears that those opting for a wider coverage argued from a point of view where economic and social impacts were potentially the cause for indirect and induced (negative) environmental impacts. On the other hand, those suggesting SEA should look at environmental impacts only appeared to assume that other instruments would be used for economic and social assessments. They feared that considering economic aspects might limit the choice of environmental alternatives that are assessed in an SEA and dilute the objective of prioritising environmental aspects. With regard to this aspect, the authors of the guidelines were not entirely convinced, though, on whether there really was a contradiction between the two lines of arguments. In response to these comments, it was noted that while economic aspects may be considered when assessing the environmental implications of options, SEA needs to be guided by environmental considerations.

Similarly diverging comments were received with regard to the extent to which accidents should be considered and assessed. Whilst some said it was vital that accidents were covered (in particular in the context of transboundary considerations), others thought that there was a need for dedicated separate accident and emergency plans. They suggested that this should thus not be repeated in SEA. These comments resulted in the guidelines stressing that the preparation of accident and emergency plans (common practice in the nuclear industry) were essential.

There was also no agreement on the extent to which positive climate change impacts should be considered in nuclear power programme SEAs. Whilst some suggested that there was a strong case for their consideration, others thought this was more appropriately addressed at the policy level at which a decision is taken on whether or not to go ahead with developing nuclear energy. While the guidelines recommend to also consider positive impacts, they highlight the importance of scoping to adjust the impacts taken into account to best fit the specific context within which SEA is applied in (see also Therivel Citation2004).

There were also different opinions on whether a full life cycle approach should be used in SEA at the programme level (see ). Whilst some suggested that a nuclear power programme SEA needed to comprehensively consider all stages of the nuclear fuel cycle, others thought that only those stages managed in the country for which the programme was prepared should be included. In the guidelines, it is finally stated that all stages of the fuel cycle are potentially of importance and that a conscious decision will need to be taken on the extent to which stages occurring in another country should be considered. There was no clear idea, though, amongst those commenting on the guidelines on what this may look like.

With regard to the overall approach and the level of detail adopted in the guidelines, there was a feeling that a good balance was struck. However, a few comments were also received, suggesting that they were either too detailed and too specific or not detailed and specific enough. A few reviewers with an engineering background asked for a more detailed coverage of nuclear technology. Also, some suggested that the style of the guidelines and the contextual introduction provides may be ‘too academic’, as they are going beyond the format of a simple manual for users. Others, especially practitioners, underlined the importance of providing context in the beginning and commended the approach taken. The team preparing the guidelines subsequently made the conscious decision to keep the section on context (with some more minor changes being introduced). No attempt was made to turn the guidelines into a simple manual, keeping the option open to provide a ‘hands-on summary’ in the future. However, for the sake of clarity, sections 4 (Process), 5 (Stakeholder engagement and public participation) and 6 (Assessment methods and data requirements) were clearly marked as covering the SEA ‘methodology’, thus fulfilling the function of a manual, together with section 7 outlining the SEA report. This was highlighted also when describing the structure of the document.

Two of those commenting expressed some concern that the guidelines were extending beyond existing legal requirements in most countries, in particular by focusing on the overall context and position of SEA in the decision making hierarchy. However, the guidelines are not written having any specific legislation in mind, as they need to be applicable to all IAEA Member States intending to develop a nuclear power programme. Rather, they are meant to reflect international good practices. With applying a framework approachFootnote3 they are bound to go beyond (existing) legislative requirements, which tend to focus more on procedural aspects of one particular SEA.

Suggestions which could not be included in the guidelines

A few suggestions on the guidelines were not in line with the overall approach taken and therefore could not be included. These revolved around the subject of the assessment itself, the SEA process as well as the wider methodology. With regard to the subject of assessment, one reviewer suggested that the scope and structure of a nuclear power programme was insufficiently explained. However, chapters 2 (Context) and 3 (Environmental and related sustainability issues) focus on substantive issues in their entirety. Furthermore, this topic is also the explicit focus of numerous IAEA publications, such as the ‘Milestones in the Development of a National Infrastructure for Nuclear Power’ (IAEA Citation2015). Finally, as explained above, the content of a nuclear power programme SEA will depend on what aspects are covered in previous assessments at the levels of policies and plans. If there is a gap, SEA will need to acknowledge this, but may not be able to fill the ensuing gap. If, on the other hand, policy and plan issues are dealt with elsewhere, the SEA will be more focused.

With regard to the SEA process, there were a couple of comments on the need for full integration of SEA and programme processes. However, based on the evidence provided by a range of authors (summarised by Tajima and Fischer Citation2013), the team preparing the guidelines deliberately opted for the promotion of parallel SEA and programme making processes that connect and engage with each other regularly. A reason for this is the risk that SEA may be subordinated and diluted within the programme making process in countries with little SEA practice and institutional support for SEA (see also Retief Citation2007).

There was also a comment on when SEA should be triggered, suggesting that this should be based on significant environmental effects, both, negative and positive. However, whilst SEA should always consider negative and positive effects, it is usually triggered based on anticipated significant negative, rather than positive environmental effects. It is important, though, that the guidelines are based on the recommendation that SEA would always be required for developing a new nuclear power programme or for considerable changes of existing programmes.

Finally, there was also a comment on the overall approach taken with regard to differentiating the approach based on geographical focus and type of country in which SEA is applied, in particular developed and developing countries. However, the guidelines’ preparation team did not find such a distinction helpful, in particular as neither developed nor developing countries are coherent and many of the issues and challenges are similar throughout the world (see e.g. Fischer and Onyango Citation2012).

Reflections and conclusions

Overall, the participative approach applied to the drafting of the first set of guidelines for SEA of nuclear power programmes internationally led to a range of different views being reflected in the final product. There was some widespread support for the framework approach used in the guidelines, meaning that issues covered – and those not covered – at higher tier policies and plans need to be considered when making decisions on what to include and what not to include in a specific nuclear power programme SEA.

Whilst nearly all of those consulted were positive about the overall approach taken, there was disagreement on whether social and economic aspects should be considered next to environmental aspects and whether associated assessments should be fully integrated with SEA. With regard to this aspect, no definite answer is provided in the guidelines. However, questions are offered that might help a user to choose the best possible approach in a specific situation.

There was one request by a few of the reviewers that the expert group felt was impossible to meet. This refers to the preparation of a ‘one-fits-all’ manual or checklist methodology and is irreconcilable with the approach taken, which is based on supporting a user in asking questions that are appropriate to a particular situation of application. This is in line with the conceptual underpinnings of SEA that are associated with it being a decision support tool which aims at creating an informed debate, thus making decision processes more structured, systematic and transparent for both, experts and non-experts (Illsley et al. Citation2014).

Aspects of the guidelines that received very positive comments included the various components of SEA quality review, going beyond the review of an SEA report to cover the entire process and its role within decision making. This includes the engagement with stakeholders and public participation as part of quality review. In existing practice, quality review is frequently associated with establishing the quality of documentation only (Fischer Citation2010).

When preparing the guidelines, the group did not start with a blank sheet of paper. Rather, a large number of existing documents, already published by the IAEA on the development of nuclear power had to be taken into account in order to avoid inconsistencies. This means that certain aspects were to some extent predetermined, for example, nuclear power impact areas and nuclear infrastructure issues.

Whether all aspects of the guidelines will ultimately be consistently considered by those applying them remains to be seen. In particular, we expect that some will find the framework approach towards SEA (a tiered framework, considering all relevant policies, plans, programmes and projects) difficult to comprehend. It means that in a nuclear power programme SEA initially a gap analysis should be conducted, establishing whether all important policy and plan issues have actually been addressed prior to the preparation of the programme. Different disciplines have different working cultures, and from the consultation carried out in the context of drafting the guidelines, it is clear that some would prefer to be provided with a one-fits-all manual, which focuses on the one programme procedure only.

It is within this context that the guidelines will need to be critically reviewed after they have been used for some time as practical experiences with their implementation will help developing a better understanding of what aspects may need to be improved. It is clear that any guidelines that stay the same for too long run the risk of being in the way of improving practice and may have a negative rather than positive effect, as new insight and new knowledge are overlooked (Jha-Thakur and Fischer Citation2016).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. NB: This decision does not mean nuclear power will definitely be developed, as this initial decision may be reconsidered at any of the subsequent stages .

2. A critical friend can be defined as a trusted person who asks provocative questions, provides data to be examined through another lens […]. The friend is an advocate for the success of that work (Costa and Kallick Citation1993).

3. Framework approach in this context refers to the consideration of the interdependence of policies, plan, programmes and projects relevant to SEA along with the consideration of the overall context.

References

- Aschemann R, Baldizzone G, Rega C. 2016. Chapter 11: public and stakeholder engagement in strategic environmental assessment. In: Sadler B, Dusik J, editors. European and international experiences with strategic environmental assessment – recent progress and future prospects. London: Earthscan; p. 244–269.

- Belcakova I. 2008. Report preparation and impact assessment methods and techniques. In: Fischer TB, Gazzola P, Jha-Thakur U, Belcakova I, Aschemann R, editors. Environmental assessment lecturers’ handbook. Bratislava, Slovakia; ROAD Bratislava; p. 157–165.

- Canter LW. 1998. Methods for effective environmental impact assessment. In: Porter A, Fittipaldi J, editors. Environmental methods review: retooling impact assessment for the new century. Fargo (ND): IAIA; p. 58–68.

- Costa A, Kallick B. 1993. Through the lens of a critical friend. Educ Leadersh. 51(2):49–51.

- De Montis A, Ledda A, Caschili S. 2016. Overcoming implementation barriers: a method for designing strategic environmental assessment guidelines. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:78–87.

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. 2013. Offshore energy strategic environmental assessment (SEA): an overview of the SEA process. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/offshore-energy-strategic-environmental-assessment-sea-an-overview-of-the-sea-process#offshore-energy-sea-research-programme.

- Dusik J, Fischer TB, Sadler B. 2003. Benefits of a Strategic Environmental Assessment, REC, UNDP, 5. www.ecissurf.org

- Ekovert Łukasz Szkudlarek. 2014. Strategic environmental assessment report for the Polish nuclear programme. Warsaw: Ministry of Economy.

- Environmental Protection Department. 2005. Hong Kong strategic environmental assessment manual. http://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/SEA/eng/sea_manual.html.

- European Commission. 2001. Implementation of Directive 2001/42 on the assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/eia/pdf/030923_sea_guidance.pdf.

- Fischer TB. 2000. Lifting the Fog on SEA. Towards a categorisation and identification of some major SEA tasks. In: Bjarnadóttir H, editor. EA in the Nordic Countries. Stockholm: Nordregio; p. 39–46.

- Fischer TB. 2006. SEA and transport planning: towards a generic framework for evaluating practice and developing guidance. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 24(3):183–197.

- Fischer TB. 2007a. Zur internationalen Bedeutung der Umweltprüfung (on the international importance of environmental assessment. UVP Rep. 21(4):248–255.

- Fischer TB. 2007b. Theory and practice of strategic environmental assessment – towards a more systematic approach. London: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB. 2010. Reviewing the quality of strategic environmental assessment reports for English spatial plan core strategies. EIA Rev. 30(1):62–69.

- Fischer TB, Onyango V. 2012. SEA related research projects and journal articles: an overview of the past 20 years. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(4):253–263.

- Gauthier M, Simard L, Waaub J-P. 2011. Public participation in strategic environmental assessment (SEA): critical review and the Quebec (Canada) approach. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31:48–60.

- Government of Ireland. 2004. Assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment – guidelines for regional authorities and planning authorities. http://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/migrated-files/en/Publications/DevelopmentandHousing/Planning/FileDownLoad%2C1616%2Cen.pdf.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2000. Regulatory control of radioactive discharges to the environment, IAEA safety standard series no. WS-G-2.3.. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2002a. External human induced events in site evaluation for nuclear power plants, IAEA safety standards series no. NS-G-3.1.. Vienna.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2002b. Dispersion of radioactive material in air and water and consideration of population distribution in site evaluation for nuclear power plants, IAEA safety standards series no. NS-G-3.2.. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2007. Considerations to launch a nuclear power programme. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2010. Seismic hazards in site evaluation for nuclear installations, IAEA safety standards series no. SSG-9. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2011. Meteorological and hydrological hazards in site evaluation for nuclear installations, IAEA safety standards series no. SSG-18. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2012a. Regulations for the safe transport of radioactive material, IAEA safety standards series no. SSR-6. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2012b. Getting to the core of the nuclear fuel cycle – from the mining of uranium to the disposal of nuclear waste. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2013. Options for management of spent fuel and radioactive waste for countries developing new nuclear power programmes, IAEA nuclear energy series no. NW-T-1.24. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2014. Managing environmental impact assessment for construction and operation in new nuclear power programmes, IAEA nuclear energy series no. NG-T-3.11. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2015. Milestones in the development of a national infrastructure for nuclear power, IAEA nuclear energy series no. NG-G-3.1. Vienna: IAEA.

- IAEA – International Atomic Energy Agency. 2018. Strategic environmental assessment for nuclear power programmes: guidelines. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency.

- Illsley B, Jackson T, Deasley N. 2014. Spheres of public conversation: experiences in strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 44:1–10.

- Jansson AHH. 2000. Strategic environmental assessment for transport in four Nordic countries. In: Bjarnadottir H, editor. Environmental assessment in the Nordic countries. Stockholm: Nordregio; p. 39–46.

- Jha-Thakur U, Fischer TB. 2016. 25 years of the UK EIA system: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:19–26.

- Jiricka A, Formayer H, Schmidt A, Voller S, Leitner M, Fischer TB, Wachter TF. 2016. Consideration of climate change impacts and adaptation in EIA practice – perspectives of actors in Austria and Germany. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 57:78–88.

- Jiricka A, Wachter TF, Leitner M, Margelik E, Czachs C, Formayer H, Fischer TB. 2018. Entry points for climate change adaptation in EIA in Austria and Germany. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 71:26–40.

- Kørnøv L. 2009. Strategic environmental assessment as catalyst of healthier spatial planning: the Danish guidance and practice. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29(1):60–65.

- Naturvardsverket. 2010. Practical guidelines on strategic environmental assessment of plans and programmes. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publikationer/978-91-620-6383-2.pdf.

- Noble BF, Gunn JH, Martin J. 2012. Survey of current methods and guidance for strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(3):139–147.

- Novikau A. 2016. Nuclear power debate and public opinion in Belarus: from Chernobyl to Ostrovets. Public Underst Sci. 26(3):275–288.

- OECD DAC. 2006. Applying strategic environmental assessment – good practice guidance for development co-operation. http://content-ext.undp.org/aplaws_publications/2083957/OECD%20DAC%20SEA%20Guidance%20eng.pdf.

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. 2004. A practical guide to the strategic environmental assessment directive. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7657/practicalguidesea.pdf.

- Öko-Institut. 2015. Strategic environmental assessment of the national programme for the safe management of spent fuel and radioactive waste. Cologne: Öko-Institut.

- Pampel FC. 2011. Support for nuclear energy in the context of climate change evidence from the European Union. Organ Environ. 24(3):249–268.

- Paul C Rizzo Associates. 2010. Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) – Proposed Nuclear Power Plant Complex, Western Region, Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE, Project No. 08-4075, Paul C. Rizzo Associates, Vol. 1, Abu Dhabi.

- Retief F. 2007. A performance evaluation of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) processes within the South African context. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27(1):84–100.

- Scottish Environment Protection Agency. 2011. The Scottish strategic environmental assessment review – a summary. https://www.sepa.org.uk/media/27556/sea-review_summary.pdf.

- Stockholm Environmental Institute. 2001. Strategic environmental assessment: methodology and application in the energy sector. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish National Energy Administration.

- Tajima R, Fischer TB. 2013. Should different impact assessment instruments be integrated? Evidence from English spatial planning. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 41:29–37.

- Therivel R. 2004. Strategic environmental assessment in action. London: Earthscan.

- Therivel R, Caratti P, Partidário MR, Theodórsdóttir AH, Tyldesley D. 2004. Writing strategic environmental assessment guidance. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 22(4):259–270.

- Therivel R, Fischer TB. 2012. Sustainability appraisal in England. UVP Rep. 26(1):16–21.

- UNECE. 2007. Kyiv protocol on strategic environmental assessment. [accessed 2018 Dec 27]. http://www.unece.org/env/eia/sea_protocol.html.