ABSTRACT

This research argues a need for a shared understanding of reflective practice across all the stakeholders involved in initial teacher education and develops a typology for assessing reflective writing. During the course of the research, the experiences of eighteen Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) secondary students were explored. This was achieved through the use of questionnaires, semi- structured interviews and the analysis of reflective journals. This data collection was supported by post-course interviews of 4 students. A grounded theory informed approach was adopted.

The results show that over the course of the year, all of the students improved in their ability to reflect, both in discussion with their mentors and in their written work. The typology that was developed as an outcome of the research is a useful tool to use with Initial Teacher Education (ITE) students when exploring what reflective practice is and how to write reflectively and as such has been used extensively within my own institution to support the development of reflective practice.

Introduction and literature review

Reflection in teacher education is a difficult concept to define due to multiple interpretations of the terminology. Within this research reflection is defined as:

‘The process by which individuals make sense of their experiences by a consideration of, and possible change in, their own personal skills, knowledge and dispositions in light of the personal, professional and wider social contexts within which they, as practitioners, operate’ (Gadsby & Cronin, Citation2012, p. 2)..

Reflection has increasingly become a key focus of professional development across many disciplines, particularly those with a professional dimension such as teacher education, (Loughran, Citation2002; Ottesen, Citation2007). The development of the reflective practitioner is a generally agreed aim of educators but there is a lack of clarity and agreement about what this actually means in practice and how best it is achieved (Gadsby & Cronin, Citation2012).

This research set out to explore how ITE students developed their ability to reflect over the course of a PGCE year and to develop a typology for assessing and teaching reflective writing. To this end the following key questions were explored:

Does the use of reflective journals help to encourage the student to be more critically reflective?

How do students conceptualise reflection and is there a shared understanding of what reflective practice is?

What would a reflective practice writing typology look like?

Reflection and reflective practice is widely acknowledged to be a problematic area to define, (Hatton & Smith, Citation1995; Ottesen, Citation2007) open to many different interpretations and nuances (Calderhead, Citation1987; Day, Citation1993; Dewey, Citation1933; Schon, Citation1983). Tabachnick and Zeichner (Citation1991) identify three types of reflective practice, academic, social efficiency or developmentalist. In each of these types, reflection takes on a different form: from the academic tradition where the subject matter is the focus for reflection, to the social efficiency where the reflection is linked to what the research promotes, to the developmentalist where the focus is on the students’ interests and needs. Liston and Zeichner (Citation1991) emphasise the importance of both inward and outward looking reflection in order to improve practice. There is no one accepted definition of reflection but common themes can be extracted from all the definitions. They all refer to an initial problem or sense of doubt that prompts the desire to find out more. They all advocate the development of knowledge but do not really define what is meant by knowledge or whether this is prior or new knowledge. They all infer that time is crucial for effective reflection to take place.

Reflection has been a significant topic within education since Dewey (Citation1933) first suggested the idea of multiple influences. Schon (Citation1983) developed the idea of reflection in action and reflection on action, he argues that in order to facilitate good reflection there needs to be an integration of theory and practice. The theory is informed by practice and the practice by theory. Schon (Citation1983) also recognises the need for a knowledge base on which to scaffold these reflections. This knowledge base serves as a resource to inform reflections and hence practice. What constitutes ‘reflective thinking’ is problematic with similarly divergent perspectives about what role it plays within reflective practice.

Lesnick (Citation2005) argues that there is still a need to understand reflection in teacher education better and that until we have a more comprehensive definition any real progress will be limited. Fook (Citation2010) identifies the need to integrate personal experience and be aware of the emotions that these experiences generate. The argument is that this will then develop greater depth and breadth in the reflections and elevate them to a higher critical level. Farrell (Citation2013) argues that a simple analysis of practice rarely leads to improvement in the teaching because it lacks any structure.

Another key area of criticism is the theory-practice gap. Many students will understand the concept in terms of the theoretical idea but cannot put this into practice when on placement (Collin et al., Citation2013). The students acknowledge the need to be reflective in their practice but the day to day pressures of being in the classroom, preparing lessons and teaching tend to get in the way of effective reflection on their practice.

It is about establishing a supportive community that helps to develop individual teacher identity (Gelfuso & Dennis, Citation2014). Reflection does not just happen. Even when the time is set aside it needs to be fostered and developed using a variety of different supporting techniques. Reflection is the core to all development in teacher education and it should be seen as a means of developing an overarching competence for teaching, one that links all the others.

In order for practitioners to be able to reflect effectively, there is a need for a contextual typology. Some academics, like Dewey (Citation1933), see these typology’s as a series of steps that the practitioner will move through as their experience develops. Others like Sparks- Langer and Colton (Citation1991) suggest that the practitioner can be working in more than one typology context at any time. Many academics (J. Moon, Citation2006; Thompson & Thompson, Citation2008) see reflective practice as a potentially transformative process. At its heart is the process of becoming aware of the knowledge that is needed to inform and thereby transform the practitioner’s practice. Reflective practice will only be effective if both the theoretical standpoint and the practical have equal billing, an absence or overemphasis of either will reduce the practitioner’s ability to be critical and hence become a barrier to effective reflection.

A number of researchers (Luttenberg & Bergen, Citation2008; Russell, Citation2013) have extended the debate around developing a typology for reflection and look at a variety of different ways of defining how student teacher’s reflective stance develops. Luttenberg and Bergen (Citation2008) have identified two different dimensions in the existing typology’s, which they refer to the ‘breadth’ and ‘depth’ of reflection. They identified certain characteristics that were indicative of each dimension. The breadth dimension has a sociological stance while the depth dimension is rooted in a psychological approach. The breadth dimensions is characterised by the reflector concentrating on the object of the reflection and how the teacher develops their teaching, while the depth dimension is more concerned with the process of thinking. In this model, the reflection can be cyclical and it is argued leads to the use of higher level thinking skills. Students will only start to develop breadth after a sustained time in school. Russell (Citation2005) identified this to be after the students had completed their first placement.

While most typology’s lend themselves to one of these two stances, some mix both dimensions. For example, Hatton and Smith (Citation1995), whose two lower levels fit the breadth dimension and their upper two levels the depth dimension. The typology developed for this research is a mixture of the breadth and depth dimensions.

There is much debate over the use of reflective journals in teacher education as a means of encouraging the growth of the reflective practitioner. How reflection is measured and the types of journal used varies significantly across different programmes in different universities.

Sparks- Langer and Colton (Citation1991), Valli (Citation1997), and Lane et al. (Citation2014) produce typology’s that are specific to teacher education. Many authors (J.A. Moon, Citation1999; Jay, Citation2003; Regan et al., Citation2000) suggest levels and progression in reflective development, moving from practical issues to more abstract and profound issues of beliefs and values. This idea of linear progression is simplistic and does not fully reflect the complexity of reflection undertaken by ITE students. The process of becoming a reflective practitioner is complex and multi-dimensional. However, for the purposes of analysis of reflective writing there is a benefit in identifying different levels of engagement and reflection. A recognition of these differences is also important to support the student’s ability to discriminate between different forms of reflection.

Much of the literature does suggest that journal writing helps teachers make clearer connections between knowledge and practice (Calderhead, Citation1991). McDonough (Citation1994) and Richards and Farrell (Citation2005) suggest that writing in a journal can help teachers raise questions about their practice. Writing in a journal enables teachers to become more aware of what is happening in the classroom. The day-to-day behaviours they exhibit and how these impact upon the learning and progress made by the pupils in their class. Writing about their experiences involves analysing not only their attitudes but also the outcomes of their various stances in respect to certain stimuli in their classroom.

Developing into a reflective practitioner requires the student to go beyond a mastery model of learning (Lui, Citation2017) and work towards a transformational approach to learning. Mastery as a concept (Guskey, Citation2015) has been adopted by schools as a pedagogy for effective teaching and learning where the pupils become experts in certain aspects of the curriculum. This approach is then adopted by the student teachers who identify what they need to achieve to pass the course and don’t develop their ideas beyond the mastery stage. This leads to them reaching the plateau stage but never moving beyond it to truly critical reflective teaching ‘if reflection stops with reflection it cannot be transformative’ (Lui, Citation2015, p. 147). In order to transform learning students, need to think and then re-think and challenge their previous assumptions.

Methodology

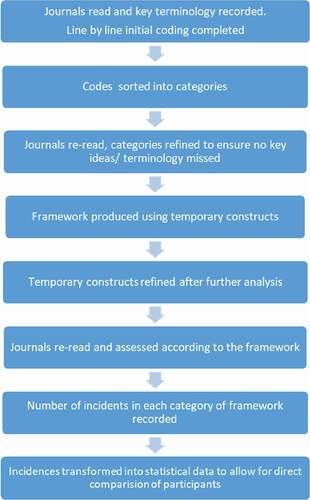

The epistemological premise of this study was to examine the experiences of the participants involved and to subsequently interpret the knowledge of their individual and collective experiences. This study took such an interpretivist epistemological stance in an attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of the participant group and from there to offer an interpretation of their perspectives. The constructivist grounded theory approach seemed to be the most suitable as the data collection and context development was based around construct development (). While not all the research followed a traditional grounded theory approach the main outcomes of the reflective writing typology and reflection model were developed using the grounded theory approach of construct, development and coding.

Within the research framework a number of different data collection techniques were used to help with the development of a reflection writing typology;

Individual interviews with a small number of selected participants at the end of their first year of teaching.(4 interviews).

Elicited text analysis from semi-structured questionnaires/ interviews with all the participants at two review points during the course (36 interviews).

Analysis of extant text in the form of the participant’s reflective journal assignment to determine level of reflection at various stages of the course (36 assignments each of 5,000 words length).

All of the twenty students completing reflective journals agreed to participate although two trainees withdrew from the course and therefore were no longer a part of the sample group. All the students who were completing reflective journals as part of their course were included in the research because it was felt it was important to have a range of reflective ability in the sample and this could not be determined prior to the start. The selection of the four participants interviewed at the end of their NQT year was purposive sampling (Cohen et al., Citation2011). Four were selected to get a range of reflective ability. This was determined from the initial data collected where their reflective writing ability was identified by the analysis of their journals. Two of the students chosen fell into the self-questioning category, this group was the largest of the four groups. The other two were chosen because one had moved from a level 3 to a level 1 when the typology was applied to their writing and the other one was writing at the top level of the developed typology right from the start.

The analysis of the students’ written journals which were produced as an element of the taught PGCE course were key to the research. By analysing the journals, the confidence of the student to write reflectively was determined. The grounded theory technique of coding (Charmaz, Citation2006) was used to analyse all the extant text, both the reflective journals and the mentor lesson feedback forms.

The typology for assessing the reflective writing in the students’ journals was developed using coding and constructs that evolved from the written texts. In order to try to assess the reflective level at which the students were writing, their written journals were assessed at two significant points during the course. In order to help the students structure their writing the journals used in this research are a combination of a double entry descriptive then reflective journal and a journal that has structure built into it.

Primarily the texts were being used to determine the level of reflective writing the student teachers had reached at two key points in their training. The first step was to complete open coding of the journals. These initial codes that emerged from the data were used to sort, synthesise, integrate and organise the data. The codes were based around the style and content of the writing so included comments like describes what happens, asks a question, developing beliefs, guidance, makes connections, used theory to support ideas, and considers other ‘viewpoints’. Once all thirty eight journals had been read and coded line by line these codes were condensed down and recoded to give subcategories, these became the descriptors used in the typology. The subcategories allowed the data to be categorised incisively and completely. From these subcategories theoretical coding was used to generate four big categories (). Each participant’s data was then recoded individually to determine a best fit level of reflective writing and thinking for each of the two collection points. The number of incidences of each type of subcategory was recorded to give an overall number for each major category of the typology. This allowed a subjective level of reflective writing to be applied to each student participant.

Table 1. Reflective writing typology

Informational interviewing linked to the prior use of elicited texts in the form of an open-ended questionnaire was used to establish the students views of reflection and how they viewed it at different stages of the course. The aim of the informational interviews was to elicit definitions of terms, assumption and implicit meanings. These were not coded and so were not transcribed.

The use of the elicited text allowed a detailed response from each participant written in their own words which were then used to exemplify the findings, reflected his or her ideas and views. To make sure that as far as possible the students were not influenced by my ideas and they were given a chance to express their views and ideas unaided.

Results

Students’ conceptions of the nature of reflection developed over the academic year. The data from the questionnaires and semi structured interviews shows three distinct stages in their understanding of reflection as a form of knowledge. This included how they perceived reflection and how they reflected at the end of each lesson.

Initially the student’s perception of reflection was dominated by a very simplistic idea of what reflection was. They saw it as a simple evaluation of the lesson which could be completed in five minutes by returning to their lesson plan and writing about ‘what went well and even better if’. They initially identified any strengths ‘what went well’. For the weaknesses they had to think about how the problem could be improved upon ‘even better if’.

At Christmas half of the students saw reflection as a prescriptive task to be completed. Student 3ʹs response when asked to define what reflection was is representative of this group.

Having the ability to look back and review your lesson, to see what went well and what did not go so well, but more importantly why this happened (student 3, first questionnaire).

The other half saw it as an evaluation process which also involved a thought process but still did not make the link between thought and improved action. Student 17ʹs response is a good example of how reflection was viewed.

Someone who reviews their work on a regular basis and uses this information to help them improve. To help you improve and become aware of your strengths and weaknesses (student 17, first questionnaire).

As the students started to develop more confidence in their teaching as their time in school increased and they went on a full week block placement they showed signs of understanding how the theory impacted upon their teaching. Most showed signs of a deeper understanding of the theories they had explored in university. They became more confident in their own ability to evaluate their lessons in detail and reflect using both these theoretical ideas and their practice. Their understanding of what reflection was developed significantly in most cases.

Student 17ʹs definition of reflection is indicative of the comments the students made after the second block placement.

Always bettering yourself, your teaching to best suit your environment and your pupils. I am a reflective practitioner. Whether I have a good or bad lesson I always question why- what worked and what didn’t work and why (student 17, final questionnaire).

The way in which they reflected and evaluated their lessons had also moved on. Many now acknowledged that it was harder than they had first thought and had a better understanding of how their developing pedagogical knowledge impacted on how they thought about their classroom practice.

The analysis of the reflective journals using the typology showed that all the students improved their reflective writing ability over the course. By the end of the year none of the students work displayed the characteristics of just descriptive heavy narrative writing. Most of the students who developed a self-questioning or meta-cognitive approach did so at the end of their second block placement. The students started questioning what they do and understanding where their experiences sit within a wider educational setting. Students writing at this level had started to ask questions but often did not explore the literature to find the answers to the questions that they asked.

I question the effectiveness of rephrasing questions in written tasks and am considering the value of increased scaffolding of the answers instead. This is because I wish to encourage students to interpret higher level language themselves. (extract from second reflective journal, student 13).

This student consistently wrote at the self questioning level, as can be seen from the extract there is little attempt to actually critically consider the observations being made.

Students writing at the meta-cognitive level showed a greater understanding of how exploring the questions they were asking would improve their practice.

There is arguably the thought that differentiation can at times be a form of exclusion rather than its intended inclusivity by pupils being seen to need additional support before they have attempted the set work, but generally a whole class can gain from a teacher having to think of other formats to fulfil the curriculum expected outcomes and develop personal progress (extract from reflective journal, student 17).

Students who reached the top level of writing had a much wider awareness of how the school environment had an impact upon their teaching as the quote below shows

I never considered the concept of belonging when planning this lesson on place. In hindsight I feel I hold some responsibility for the racist remarks as my teaching strategies were very closed and one sided … … I am left wondering what is meant by the word ethical. I am left questioning if a student teacher can eliminate their personal hurt for professional gain. (extract from reflective journal, student 1).

There are many more examples of how the students have developed their reflective writing stance but these quotes give a flavour of how the writing differed within each level of the typology.

Discussion and Conclusion

How do students conceptualise reflection and is there a shared understanding of what reflective practice is?

The variety of definitions, even within a relatively small group who had all received the same theoretical input, demonstrates the point that was made in the literature review, that there is a need for a much clearer definition of exactly what ITE tutors and mentors understand reflective practice to be. This needs to be communicated to the students much more clearly so everyone has a shared understanding of what is being aimed for. There is also a need for the university management and tutors to have a clear shared understanding as the students get very different messages from different tutors. There is a need for a much greater emphasis on the development of reflection in the earlier stages of the taught course.

Does the use of reflective journals help to encourage the student to be more critically reflective?

The research findings clearly show that the use of the journals did over time help the students to develop into more confident reflective practitioners. All the students progressed in their reflective writing ability over the course of the PGCE year. The analysis of the development of reflective writing through the use of the journals has raised a number of questions around how students evaluate and reflect. That all of the students made some progress in their reflective writing is encouraging. It suggests that with better structures and support systems, a better understanding of how to reflect and a course that is structured to encourage reflection as individuals and in groups throughout the full year, further progress could be made. The students could then develop a stronger reflective stance to help them once teaching in school full time. However, the conflict around prescription and desire still exists. The data suggests students would not complete reflections if they were not part of the assessed course. The research also suggests that the students’ lack of understanding of the purpose and value of reflection during the course means they do not value its importance in transforming their practice. The data suggests if they understood from early on the role reflection plays in their development, they would be more predisposed to engaging with it during their training year.

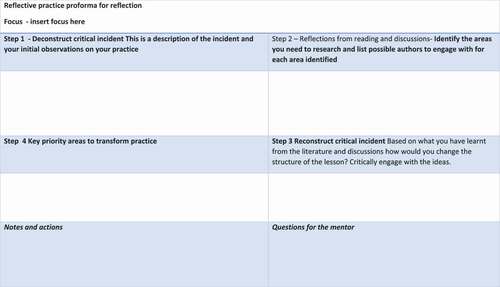

The research results identified a need to help students to structure their reflective writing as well as to understand how reflective writing is structured. It was found that the journal used as part of the research were too time consuming to encourage full engagement on a regular basis. To this end a pro-forma for reflecting on individual incidents/ lessons () has been developed in light of the research findings. This pro-forma encourages the students to think beyond basic description of what happened in the lesson and encourages them to engage with the literature around the topic being explored, this is an adaption of a journal format to make it more specific to individual lessons. I use this pro-forma extensively in my teaching and students are expected to reflect using it at least twice a week after formal observations during their teaching practice. It has helped to improve the student’s reflective stance because it makes them consider more than their own and their mentors views of the lesson they taught.

What would a reflective practice writing typology look like?

Four levels of reflective writing were determined ranging from simple descriptive work through to writing which takes into account the wider elements of teaching. The four levels were descriptive heavy narrative, self-questioning, meta-cognition and wider awareness (). While the typology has been developed to assess students reflective writing it can also be used to discuss with students how to reflect and guide them in both their writing and oral reflection while on the course and once qualified. The typology becomes a basis for articulating the procedure to develop as a reflective practitioner. I am currently using the typology and the reflection pro-forma with my students to help frame their reflections so they understand the difference between description and reflection.

The research has identified a need to give students targeted support and structures to help them to develop into reflective practitioners. The typology for reflection helps them to understand the difference between description and reflection, while the reflection pro-forma encourages them to reflect in a deeper and more focused way about specific aspects of their practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helen Gadsby

Dr Helen Gadsby is a senior lecturer in the School of Education at Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool. Her research interests are Reflective practice in teacher education, mentor development, geography and sustainability. She teachers on the PGCE, PGDE and Masters in Education provision. She also contributes to the extensive mentor development programme that the university offers for partnership schools.

References

- Calderhead, J. (1987). The quality of reflection in student teacher’s professional learning. European Journal of Teacher Education, 10(3), 269–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0261976870100305

- Calderhead, J. (1991). The nature and growth of knoweldge in student teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 7(1), 531–535. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(91)90047-S

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research Methods in Education. Routledge.

- Collin, S., Karsenti, T., & Komis, V. (2013). Reflective practice in initial teacher education: Critiques and perspectives. Reflective Practice: International and Mutlidisciplinary Perspectives, 14(1), 104–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.732935

- Day, C. (1993). Reflection a necessary but not sufficient condition for professional development. British Educational Research Journal, 19(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192930190107

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Farrell, T. (2013). Teacher self awareness through journal writing. Reflective Practice: International and Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 14(4), 465–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.806300

- Fook, J. (2010). Beyond reflective practice: Reworking the ‘critical’ in citical reflection. In H. Bradbury, N. Frost, S. Kilminster, & M. Zukas (Eds.), Beyond reflective practice: New approaches to professional lifelong learning (pp. 37–52). Routledge.

- Gadsby, H., & Cronin, S. (2012). ‘To what extent can reflective journaling help beginning teachers develop masters level writing skills? Reflective Practice, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.616885

- Gelfuso, A., & Dennis, D. (2014). Getting reflection off the page: Thechallenges of developing support structures for pre-service teacher reflection. Teaching and Teacher Education, 38(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.10.012

- Guskey, T. (2015). Masterly learning. International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2(14), 752–759.

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in Teacher Education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

- Jay, J. K. (2003). Quality teaching: Reflection as the heart of practice. Scarecrow Press.

- Lane, R., McMaster, H., Adnum, J., & Cavanagh, M. (2014). Quality reflective practice in teacher education: A journey towards shared understanding. Reflective Practice: Internatonal and Multidisplinary Perspectives, 15(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.900022

- Lesnick, A. (2005). The mirror in motion: Redefining reflective practice in an undergraduate field seminar. Reflective Practice, 6(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1462394042000326798

- Liston, D., & Zeichner, K.M. (1991). Teacher education and the social conditions of schooling. Routledge.

- Loughran, J. J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053001004

- Lui, K. (2015). Critical reflection as a framework for transformative learning in teacher education. Education Review, 67(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.839546

- Lui, K. (2017). Creating a dialogic space for perspective teacher critical reflection and transformative learning. Reflective Practice, 18(6), 805–820. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1361919

- Luttenberg, J., & Bergen, T. (2008). Teacher reflection: The development of a typology. Teachers and Teaching, 14(5–6,), 543–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802583713

- McDonough, J. (1994). A teacher looks at teachers diaries. English Language Teaching Journal, 48(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/48.1.57

- Moon, J. A. (1999). Reflection in learning and professional development: Theory and practice. Routledge Falmer.

- Moon, J. (2006). Learning journals - A handbook for reflective practice and professional development. Routledge Falmer.

- Ottesen, E. (2007). Reflection in teacher education. Reflective Practice, 8(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940601138899

- Regan, T. G., Case, C. W., & Brabacher, J. W. (2000). Becoming a reflective educator: How to build a culture of enquiry in the schools. CA: Corwin Press.

- Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. D. C. (2005). Professional development for langauge teachers. Cambridge University Press.

- Russell, T. (2005). Can reflective practice be taught? Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 6(2), 199–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940500105833

- Russell, T. (2013). Has reflective practice done more harm than good in teacher education? Phronesis, 2(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1015641ar

- Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Sparks- Langer, G. M., & Colton, A. (1991, March). Synthesis of research on teacher’s reflective thinking. Educational Leadership, 48, 37–44.

- Tabachnick, B. R., & Zeichner, K. (1991). Issues and practice in enquiry - Orientated teacher education. Falmer.

- Thompson, S., & Thompson, N. (2008). The critically reflective practitioner’. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Valli, L. (1997). Listening to other voices: A description of teacher reflection in the United States. Peabody Journal of Education, 72(1), 67–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje7201_4