ABSTRACT

Despite recognition of the importance of critical reflection for professional development in social and health care – particularly regarding professional competency and self-awareness – the use of reflective practice in professional training has received less examination. This paper evaluates the use of critical reflection as a pedagogical approach in training allied health professionals – in this instance, training Pharmacy Assistants (PAs) and Pharmacy Dispensary Technicians (PDTs) towards increasing critical reflection of their service delivery to Medication Assisted Treatment of Opioid Dependence (MATOD) consumers. Specifically, this paper examines a) the embedding of a critical reflection model within training materials; and b) the experiences of participants who undertook this training, including their experiences of applying their learnings to professional practice. Findings present a mixed picture. Despite the training unearthing and deconstructing problematic values and assumptions in the service delivery of MATOD treatments in pharmacy settings, some participants found the recognition of their own biases and prejudices overwhelming. Hence, although the critical reflection model used in the analysis has enormous potential to tackle stigma and discriminatory attitudes towards opioid dependence and MATOD and improve professional practice, greater attention to scaffolding, designing and implementing the process of critical reflection is needed.

Introduction

A recent study (Patil et al., Citation2019) found that consumers of Medication Assisted Treatment of Opioid Dependence (MATOD) wanted Pharmacists, Pharmacy Assistants (PAs) and Pharmacy Dispensary Technicians (PDTs) to receive greater education to counteract stigma and discrimination. Researchers subsequently developed educational materials on MATOD treatment and MATOD consumers’ perceptions of stigma and discrimination and delivered a pilot training for PAs and PDTs in regional Victoria, Australia (see Patil et al., Citation2021). In line with arguments concerning the importance of reflective practice for professional development in the fields of social and health care (Fook et al., Citation2006; Fragkos, Citation2016; Norrie et al., Citation2012; Tsingos et al., Citation2015), the findings from this study flagged the positive influences of consciousness raising and critical reflection on PAs and PDTs’ professional practice (Patil et al., Citation2021).

This paper assesses the efficacy of the learning resources and tutorial exercises by exploring participant reflections on the impact it had on their professional practice in the service delivery of MATOD treatment. Whilst the critical reflection framework driving the pilot training is based on Fook and Gardner’s (Citation2007) work, the heuristic tools that inform the pedagogical design of the learning resources prior and during the workshops have been adapted to the context and the purpose of the training developed for PAs and PDTs. Divided into three main sections, the paper outlines the context and design of the pilot training, the findings of the thematic analysis of participant reflections, and a final discussion of the use of critical reflection as a pedagogical approach in training allied health professionals.

Context of the study

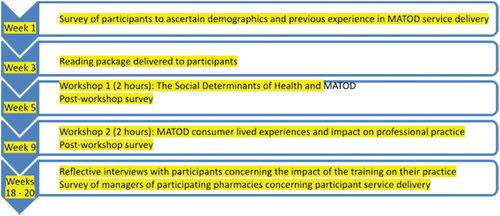

To tackle experiences of stigma and discrimination of MATOD consumers within pharmacy settings in regional Victoria, the research team – in consultation with Orticare (the Grampians Loddon Mallee Pharmacotherapy Network) – designed professional training workshops for PAs and PTDs on opioid dependence and societal stigma. Given that there is a lack of guidelines and incentivisation for these cohorts to undertake professional development, the training was advertised throughout the region and sector by the network. Aimed at increasing participants’ skills in critical reflection and enabling transformations in their perspective and behaviour, the training and its associated assessment was designed to be delivered over the course of five months. It involved the completion of surveys (pre-workshop 1, post-workshop 1, post-workshop 2), along with participation in two training workshops and a final reflective interview (see ).

All of these activities were designed to provide participants with new knowledge (the Social Determinants of Health (SDH), opioid use, the operation of stigma and discrimination, insight into MATOD consumer experience), as well as opportunities and support to reflect on their own experience, the training materials and their learnings, and to consider their application in their respective professional settings. In particular, the timing of the second workshop allowed participants to revisit learnings gained in the first workshop and supported them in the development of alternative understandings and practice. The timing of the interviews supported these developments as well as facilitating reflection on the impact participation had had on understandings, ideas and professional practice concerning MATOD service delivery. The surveys and the final reflective interviews also provided insight into the perceived value of the training design and materials. Although it was hoped that all participants would engage in the full five-month process and complete all training phases, it was realised that this could not be a requirement for participation.

Training materials combined a package of readings with additional handouts (notes, case studies, reflective questions) distributed during the workshops. Included was technical knowledge about pharmacotherapy treatments as well as information about the World Health Organization definition of SDH. Case studies used in the workshops were developed from the real-life narratives of MATOD consumers’ experiences of navigating through MATOD treatments in community pharmacies. These narratives were collected in a previous study (Authors, 2019). The inclusion of these narratives ensured that the training remained grounded in recognisable real-world situations and was clearly responsive to the needs of MATOD consumers. Three case studies were developed for use in the first workshop, and four for use in the second. Case studies were developed for use in both whole of group and small group settings; not all case studies were considered by all participants. The questions used in the workshops were designed to help participants identify the operation and impacts of both the SDH and stigma and discrimination, and uncover unarticulated assumptions being held about health and wellbeing, MATOD consumers and treatments. Participants were also encouraged to share and discuss their insights with each other in the workshops as a means of making clear that the SDH and life experiences are inter-related in highly complex ways and, hence, facilitating reflection. Questions used in the qualitative in-depth interviews were designed to elicit reflection on the trainings and on their impacts for practice.

Workshops were delivered face-to-face in two regional locations in Victoria to two separate groups of PAs and PDTs, 24 in total. Interviews were scheduled for approximately ten weeks after the second workshop. Ten out of the 24 participants participated in interviews. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, and analysed using a process of thematic analysis informed by a critical social lens combining constructionist assumptions with discourse analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Jorgensen & Phillips, Citation2002). Themes were generated from the data through coding in a process that also involved the consideration of latent and underlying ideas, assumptions and conceptualisations (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006 p. 84). Analysis involved the researchers independently coding and reviewing data, with meetings held to share, discuss and compare generated themes. The researchers further remained mindful of perspectives and presuppositions they brought to the analysis.

Before reporting on the findings and implications for professional practice in healthcare settings, we first outline the professional and scholarly interest in reflective practice as a tool for professional development. Further we outline in more detail our embedding of Fook and Gardner’s (Citation2007) critical reflection model within the pedagogical design of the training materials used in this project.

Reflective practice

There is growing interest in using reflective practice as a basis for professional learning, supervision and ongoing development in medicine, nursing, and allied health professions (Fragkos, Citation2016; Norrie et al., Citation2012; Thompson & Pascal, Citation2012; Tsingos et al., Citation2015). This trend has been influenced by changes advocated by regulatory and peak bodies, including The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) and the National Boards, State of Victoria (Citation2019) and the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW).

Fook and Gardner’s model of critical reflection

Drawing on insights from critical theory, postmodernism and discourse analysis, Fook and Gardner’s (Citation2007) model of critical reflection has been particularly influential in shaping professional practices in the human services sector. Fook and Gardner (Citation2007, p. 18) stress the development of a critical stance towards knowledge – that is, analysing the cultural, social, economic, structural, historical and political influences in the ways individuals understand and interpret the world around them. In their view, power, language and emotions derived from social and political contexts inform the relationship between individuals and society. In coming to understand the knowledge process in this way, Fook and Gardner (Citation2007, p. 18) suggest students can develop an understanding of the ‘person as individual social agent, both influenced by, but also with the capacity to influence, their social environment’.

In terms of the process involved in undertaking ‘critical reflection’ in practice, Fook and Gardner (Citation2007) argues that there are two key components. Step one refers to deconstruction – the contextualising of meanings in the broader structural, historical, social and political contexts. Here practitioners unearth, examine and unsettle deeply held assumptions through deconstructing their current knowledge processes. Step two refers to reconstruction (Fook & Gardner, Citation2007), meaning practitioners develop new knowledge that will ‘involve and lead to some fundamental change in perspective’ (Brookfield cited in Fook, Citation2015, p. 441). ‘Reconstructed knowledge’ in this stage further focuses more on opening up different possibilities for practice (Morley, Citation2011) – it stresses action as opposed to analysis. In the second stage, practitioners are thus developing knowledge in action while also creating theory that is applicable in practice. Such work arguably also encompasses advocacy for social change.

Design of learning materials and training resources

Drawing upon Fook’s (Citation2015) and Fook and Gardner’s (Citation2007) insights regarding critical reflection, training resources and learning materials were designed to promote reflection before, during and after the two two-hour training workshops. As noted, these materials included pre-workshop readings, workshop resources and survey and interview questions. Learning design drew from the following principles:

Available knowledge (e.g. on opioid dependence) is socially constructed;

Understanding is built from lived and/or professional experiences and the unsettling of assumptions within the broader social context; and

New knowledge is transformative of practice (e.g. recognition of the knowledge-practice interface).

All training materials received endorsement by industry stakeholders prior to their delivery.

Pre-training workshop resources

Pre-training workshop resources were developed for each of the two workshops in light of the first two principles. For workshop one, pre-training materials included:

Definitions of opioid dependence and types of opioid dependence treatments and symptoms;

Definition and explanation of the SDH (Wilkinson & Marmot, Citation1998); and

Annotated fact sheets with explanations of sociological factors, including individual lifestyle factors, social and community networks, health and social policies that impact on health and wellbeing.

The SDH approach was selected because of previous research proposing that better understanding the social, psychological, and mental impacts of opioid dependence could assist with tackling discrimination against MATOD consumers in the pharmacy setting (AUTHORS, 2019). Pre-training resources for workshop two included:

Definitions and explanations of the stigma and discrimination often associated with opioid dependence; and

An outline of real-world experiences of MATOD consumers in the pharmacy setting (AUTHORS, 2019).

Pre-training materials were designed to provide participants background into how MATOD consumers might perceive their interactions within the pharmacy setting.

Training workshop resources

The first of the two two-hour training workshops built on this knowledge base around SDH and socially constructed notions of health and wellbeing, with exercises focused on identifying the social and other factors that can impact on health and wellbeing in the community. Further exercises and case studies explored health and wellbeing within the context of opioid dependence. These exercises asked participants to draw on the SDH context to reflect on their experiences of assisting in administering MATOD treatment in the pharmacy setting. Exercises in the first workshop were designed to facilitate step one of critical reflection – the exposure and beginning deconstruction of participants’ assumptions regarding opioid dependence.

The second workshop explored understandings and experiences of stigma and discrimination – including those identified by MATOD consumers themselves (see, e.g. AUTHORS, 2019) – and asked participants to reflect further on their own assumptions regarding MATOD consumers. The workshop also included four case studies developed from real-life narratives of MATOD consumers (AUTHORS, 2019). The focus of these case studies was on facilitating participants’ capacities to identify broader social constructions and to critically examine the statements and language they and others used to categorise ‘MATOD consumer behaviour’. Case studies and associated questions continued the deconstruction – begun in the first workshop – of participants’ assumptions regarding opioid dependence. They also drew attention to the importance of reconstructing practice – enabling the identification of new actions and strategies that PAs and PDTs might undertake when interacting with MATOD consumers. Associated questions included: a) what assumptions might you have made about a client’s situation, and b) having reflected on these assumptions would you approach the matter differently than before? Questions facilitated participants to begin to create new practice theory with a focus on opening up different possibilities for practice and redressing any instances of stigma and discrimination.

Interview structure

Interviews were structured to identify and assess impacts – if any – of participation in the training. Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions about their thoughts regarding participation in the training workshops and the impacts this participation might have had on their understandings, ideas and professional practice concerning MATOD service delivery. Such questions were designed to provide insight into participant experiences both during and after the workshop trainings, particularly with regards to whether their reflections on the training materials and on their own professional practice had led to any changes in practice.

Findings

Thematic analysis of the qualitative interviews that followed the workshops made visible two main points: one, the usefulness of understanding SDH and the impacts of stigma and discrimination with regards to opioid dependence, and two, the usefulness of the exercises included in the workshops, particularly the case studies that were based on real life scenarios. Participants also reflected broadly on their participation in the training program and gave several suggestions regarding the training. These points are examined in the final part of this section.

Reflection 1: ‘I’ve always been a big believer in treating the cause and not the symptoms. I guess the social determinants of health is all about that’ or understanding the social context of opioid dependence

Overwhelmingly, participants identified growth in their learning about the diverse factors that inform ‘opioid dependence’. For example, they referenced the ‘social aspects and the environment, the necessities, [… and] their background’ and how such factors impact on everyone’s health and wellbeing, including that of MATOD consumers.

I didn’t know, really a great deal about the social determinants of health so I found that incredibly fascinating […] there’s a great deal about why people make the decisions that they do and why there’s the health issues in the community that there is. It’s probably reinforced something that I didn’t really know that I knew.

From their new awareness of the diverse social factors that can impact on wellbeing, participants noted their new recognition of the ‘judgment’ and ‘stigma’ commonly associated with MATOD treatments. In their reflections on these issues, participants noted the importance of ‘treat[ing] everybody the same’, ‘not judging a book by its cover’, and ‘not passing judgement’ when you do not know ‘the life history of people’.

I mean there are some people that treat them differently because they are on methadone or they are at the window, there is a stigmatism. People who are in the store look and they go, oh, is that the drug users window? […] I just think it’s wrong.

One participant explained how their personal experience of a close family member’s experience of addiction had helped them reflect on the SDH and stigma.

I have a son that is a recovering addict, so I also believe that no one knows what’s led someone down that street or down that road for them to get into that situation where they have to use it. Again, that’s why […] stigmatism is a very big thing and I’m very careful about who I say that to because people are very judgemental. I think, you know, my son came from a very good family, I’m not saying we are the perfect family, but you know we are a hard-working family, and they went to good schools and just got in with the wrong crowd.

Eight out of the 10 participants reported that learning to analyse opioid dependence in terms of the SDH and stigma and discrimination had broadened their understanding of opioid dependence. Two of the participants interviewed highlighted some of the challenges of this approach. One participant noted that one of the case studies had a negative impact on her because ‘she had a similar experience as a parent’. Another participant described her distress when analysing the social practises that underpinned one of the case studies:

[The case study] was about someone who had grown up in a broken home, or something. That kind of hit home for me because that was the same as my life growing up […] In the conversations that we were having afterwards, everyone was like, oh if you grow up in that kind of situation then you’ve got no way out and blah, blah, blah. You are going to do drugs and you are going to do that. That – I kind of cracked the shits and we had a bit of an argument. The case studies were good case studies, but I […] didn’t really want to talk about [them].

These examples highlight the challenging nature of reflection as participants connect the case studies with their own experiences.

In summary, the interviews showed that a majority of the participants seemed to have started the deconstruction stage of a critical reflection process. Participants identified how the training had not only broadened their understanding but had helped them unearth some of their unarticulated assumptions regarding opioid dependence. Some of the challenges of engaging in this process were also revealed.

Reflection 2: ‘I think it sort of showed some of the biases that we have and some of the biases that we have in our self that we don’t even realise we have’ or reconstructing professional practice: theory in action

A majority of the participants suggested that the knowledge of the SDH, stigma and discrimination gained from the training had given them additional insight into their professional practice. In particular, participants noted the importance of ‘not judging a book by its cover’, gaining ‘awareness of one’s own biases’ and making ‘efforts to change’ practice. A few participants felt the training did not directly impact their professional practice but still acknowledged their enhanced understanding of SDH, and how stigma and discrimination may impact MATOD consumers.

Embracing the second step of critical reflection, namely the reconstruction of knowledge, several participants discussed how their reflections had impacted on their professional practice. This was first through helping them reconstrue their previous interpretations of MATOD consumers.

At the start, I always just kind of thought or assumed that it was just drug users – illegal drug users that were on it but now, after doing the training, I now know that it’s also just people that have been – become addicted to prescription medications or people that are suffering really bad migraines and they use the methadone as a replacement for their other medication for the pain and stuff.

Another participant summed up the impact of the deconstruction process of critical reflection, and its capacity to lead to change.

I think it sort of showed some of the biases that we have and some of the biases that we have in our self that we don’t even realise we have. It was quite interesting talking about some of the case studies and people realising that they had a bit of a bias or a – would discriminate without even realising that they had it. Probably make a lot more effort to say hello […] to them.

A majority of participants also reflected on the ways in which they worked towards creating practice theory, describing specific changes they had made to their professional practice since the training. Participants created theory in action by taking deliberate actions to avert such situations in their professional practice.

The only thing I think I [now do …] is knowing them by name. Learning them – their names instead of that guy that comes in on a Thursday. You know the guy that’s got grey hair and always angry or the guy who’s got their earphones. I would say to the pharmacist now, what’s his name? I’d say, our pharmacists are busy at the moment, they’ll be with you as soon as they can and just smiling at them, I think is the main thing as well.

Another participant offered a candid and vivid description of how their knowledge practice had been transformed.

Yeah, it definitely made a difference on how I was to approach them or even approach them at all. Because yeah at first, I was very intimidated by them. Especially, because I have never been in a setting like this before. There’s one particular gentleman who comes in, he’s got two ankle bracelets on. He looks scary but he’s the kindest person you’d ever meet […] Obviously, you know what they’re coming in for […] He’s quite young this guy too and he has been to jail for three years, but every single time he comes in he’s just so nice […] before the training I just assumed, oh they’ve done something bad, they’ve been on drugs, that’s how they got here. But yeah, that’s not always the case, which is what the training taught us. Especially considering I didn’t know anything before and I had these very just straight up opinions which, now that I look back, I’m like, oh my goodness why did I think like that.

The process of developing new knowledge practises was not without its tensions. One of the participants describes vividly a particularly challenging discussion with one of the group members during an exercise.

me and one of the girls in there had a – an argument because she was saying that […] if someone grew up in [unclear] West and they were on Centrelink and their parents were smoking weed all the time, that’s what they’re going to aspire to be because that’s what their parents did. I 110 per cent disagreed with that […] I was like, that is the wrong attitude to have in life […] Yeah, I just didn’t agree with her – that sentiment.

This participant’s narrative illustrates some of the challenges of critical reflection. While the participant(s) found the discussion personally confronting, such experience reinforces the idea that once practitioners engage in deconstruction, and move towards reconstructing their knowledge, they can come to challenge existing stigma and discriminatory practice.

In summary, the majority of responses suggest that learning about SDH and stigma had inspired changes in perspective and professional practice. Participants provided examples of how they applied their new-found knowledge to their professional practice. Participant reflections suggest their engagement in the beginning stages of step two of the critical reflection process, namely the application of theory into practice.

Feelings and suggestions

Through some of the reflective activities, participants were asked to describe their experience of learning new content about ‘substance use’ and ‘social determinants of health’ and what they perceived as the value of case studies as learning tools to address stigma and discrimination. In response a majority of the participants reported being satisfied with their participation in the two workshops, stating that they had ‘learnt something’ and had ‘changed my view’. Another participant reflected on how beneficial they had found the workshops, stating that the training should be rolled out to others:

So definitely more training for more staff members – for more pharmacy members, definitely. I think that would be amazing and there were a few of us from my store and we all said the same thing; if everybody could do that training, it would be fantastic.

Participants referred in particular to learning garnered from case studies and/or the material presented during the workshops.

the case studies are something that you, or as a participant, that you identify or that you see something in, or you think ah, that might be so-and-so in their everyday life. […] I think they are a very good tool.

While the case study and associated small group discussion approach used in the workshops was recognised as being generally effective, participants did note that these discussions could be fraught, particularly when case studies correlated with lived experience concerning the management of opioid dependence.

I think there was a few head clashes with a few of the staff members, like us, where I think one of the girls from my pharmacy clashed with someone from [another agency]. Then another lady left crying.

Only one participant felt the training would have benefited from greater emphasis on the pharmacological and psychosomatic impacts of dependence as opposed to the focus on coming to understand the social aspects of opioid dependence.

So, I was expecting more to learn about opioids […] Just yeah, more about the drug side of things than the consumer. It was more interesting to learn about the different drugs and their effects and that sort of thing than to go over – to concentrate so much on the stereotypes.

Notwithstanding these positive reflections on the training materials, participants did raise some points of criticism.

Some of the exercises […] I felt, were a bit irrelevant and a bit above our heads […] it just felt like it was something that if the course had of been longer, it would have been easier to grasp.

Another participant felt that the initial discussion of SDH needed to be better scaffolded into the overall objective of the training. When the facilitators delivered the second half of the training material – which combined information about MATOD treatment with case studies from pharmacy settings – participants felt better able to make sense of how the SDH can interact with MATOD consumer experience. In addition, one participant noted that the number of case studies meant that not everything could be covered with the same levels of detail, stating that ‘we had so many questions and not all of them could be answered’. Several participants suggested that increasing the face-to-face training time – currently four hours in total – would assist in covering issues sufficiently and allowing for deeper learning. Other suggestions include reducing the number of case studies and reviewing the facilitation of small group discussion and training around sensitive topics.

In summary, despite suggestions for improvement, a majority of the participants found the training and associated reflection had been beneficial. They felt that they had increased their knowledge and been able to reconsider and challenge some of their assumptions, further identifying some different possibilities for practice.

Discussion

These participant reflections offer interesting insights into the application of Fook and Gardner’s (Citation2007) critical reflection model for the refinement of professional practice. On the positive side, they show that the use of this critical reflection model in allied health settings can connect theory and action through enabling the deconstruction and reconstruction of knowledge. Indeed, a majority of the participants successfully engaged in the first deconstructive steps of the critical reflection process. This work was demonstrated in the way participants increased their abilities to analyse the impact of structural/historical, political and economic constructs on the everyday experiences of MATOD consumers. Participants also unearthed and deconstructed some of the values and assumptions that informed their own lived experiences. Such identification of how their own lived experiences are shaped and influenced by broader societal factors is central to the deconstruction step of critical reflection (Fook & Gardner, Citation2007). These learnings are a reminder of the importance of adopting a broad sociological lens (such as the SDH) to conceptualise lived experience and professional practice.

Participants’ responses suggest mixed results with regards to the undertaking of the second reconstructive step of critical reflection, however. In interviews, half of the participants did outline concrete changes they had made to their professional practice. To illustrate, they talked about using inclusive language, making conscious and deliberate efforts to be respectful and empathic in their interactions and not judging MATOD consumers. Participants related these changes to their new awareness of ‘the person’s social context’, ‘the impact of stigmatising language’ and of how ‘discrimination plays out in the pharmacy setting for MATOD consumers’. Such reflections speak to the essence of step two – how changed awareness can lead to the development of different ways of thinking and changes in practice.

A few of the participants found both deconstruction and reconstruction processes challenging. For some, the deconstruction phase was unsettling because it brought to the surface experiences from their own lives and left them feeling uncertain about linking and addressing the material effects of these experiences on their professional practice. This is not unusual and the transition from recognition to knowledge and action can be problematic. That is, change in professional practice does not always occur through the processes of critical reflection, even though the ‘structure, theory and process of critical reflection is clear and focussed’ (Fook & Gardner, p. 68). Some participants might find the process or critical reflection simply reaffirms their existing practice, whereas others may find it so unsettling that they disengage from the change process. These examples illustrate some of the common reasons highlighted in the literature about the challenges with using critical reflection. Fook and Gardner (Citation2007) have argued that anxiety about the learning method and the need to have optimal conditions for self-evaluation is required as this process is not always enjoyable and is also dependent on group dynamics and participants feeling safe, listened too and not judged.

Other participant reflections suggest the need to refine the design and delivery of training materials. For instance, many participants commented on the time constraints regarding the scope of expected learning, with some articulating their frustration in not being able to engage with all materials. A few also commented on their struggle to connect discussions concerning stigma, discrimination, SDH and other concepts to their own experience. Although these points could suggest an increase in the length of training – perhaps by adding a third workshop – this would be unrealistic given the current professional contexts of PAs and PDTs. Although an extension of training time may be possible in the future – this pilot training was, after all, designed with industry input and has subsequently gained support from relevant national industry bodiesFootnote1 – it is clear that more consideration needs to be given to the design and delivery of learning materials. At the very least, this would involve additional scaffolding to assist participants in making connections between conceptual materials and lived experience. It is also evident that better consideration needs to be given to individual and group learning dynamics and experience in the selection – and quantity – and delivery of learning activities and materials.

Participants reported that workshop two, with its focus on case studies, was highly effective for their learning and subsequent application to professional practice. They also found that the second workshop retrospectively ‘explained’ the content of workshop one. This would suggest that workshop one would benefit from some revision of content and activities to build a stronger up-front connection between the SDH and the typical professional practice of PAs and PDTs. This would provide participants with a more structured and scaffolded introduction to the SDH and the issues of stigma important in workshop two. It would also increase the accessibility of the materials by better engaging the prior knowledge and training of the participants.

A further point here concerns the role of facilitators. In their design of the critical reflection process, Fook and Gardner (Citation2007) give preference to a model of small group learning aided by facilitators. The model used in the workshops delivered in this pilot training was a facilitated blend of active learning strategies including small group peer-collaborative learning. A few of the participants felt that having facilitators also guide the small group peer-collaborative learning activities would have better enabled the group to engage productively with new ideas and challenging content. Some of these participants identified that the lack of such facilitation led to them disengaging from small group discussions as they did not always feel comfortable discussing difficult issues without a facilitator mediating the discussion.

The main limitation of the study relates to the small size and the regional setting of both the participants and the pilot training, factors that may limit the generalisability of findings to broader contexts. The fact that the pilot training was informed by and responsive to the findings of a study (AUTHORS, 2019) focused on understanding the experience of regional Victorian MATOD consumers might also mean that the training addresses issues that may not be considered as significant in other Australian states or in urban contexts. Despite such concerns, it is important to note that a key outcome of the pilot training was the uptake by the Australasian College of Pharmacy of the pilot training content. The College and Orticare sponsored a one-hour video webcast presented by the lead researcher in this study that educates PAs on MATOD. This training module uses two case studies to educate PAs concerning the role of social determinants of health, opioid use and the role of MATOD, and the impact of stigma and discrimination. This webcast has received endorsement by the Quality Care Pharmacy Program, and upon completion counts towards the training requirements for PAs.

In summary, Fook and Gardner’s (Citation2007) critical reflection model has the potential to raise consciousness and initiate change among PAs and PDTs as demonstrated through participant reflections. The findings from this pilot study suggest that the work of critical reflection can be effectively introduced and promoted in allied health settings and that this work has the potential to transform professional practice. Furthermore, this study suggests the long-term benefits of introducing broad sociological lenses – such as the SDH – along with case studies as they have a strong potential, if introduced carefully in training, to enhance reflective practice and, hence, professional practice, even among cohorts – such as PAs and PDTs – unaccustomed to professional development. Indeed, consideration of this pilot training shows that such a training process can meet identified industry needs – in this case to challenge the prevalence of instances of stigma and discrimination occurring in professional contexts. It has, in other words, the potential to fill a gap in current social and health care practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Pauline Molloy, Manager, Pharmacotherapy Network for her suggestions and feedback throughout the training process. We would like to thank the reviewers for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tejaswini Patil

Dr. Tejaswini Patil: Dr. Patil’s research and teaching interests span broad fields related to social work, such as critical social work education, internationalization of curriculum and neoliberal impact on critical pedagogies, and critical cross-cultural practice.

Jane Mummery

Dr Jane Mummery’s research and teaching interests are in the borderlands of ethical and political philosophy, social policy, social change, and qualitative research theory. Dr Mummery has published widely on applied ethics, environmental ethics and critical pedagogies.

Dominic Williams

Dominic Williams is a researcher, writer, and sessional academic based at Federation University Australia. His research and teaching interact with problems in social and community spaces, philosophy and ethics, and literary expression. He is influenced by the work of Gilles Deleuze, Tyson Yunkaporta, and Spinoza.

Mohammed Salman

Mohammed Salman is a dual diagnosis (mental health and substance use) clinician and public health practitioner at Grampians Health in regional Victoria, Australia. Alongside clinical practice, Mohammed has engaged in an array of academic work that includes bioethics, communication skills in health care, critical and integrative practice, and public health palliative care.

Notes

1. The effectiveness of the pilot training (see AUTHORS, 2020) has led to it being subsequently developed into an online training module that has received QCPP (Quality Care Pharmacy Program) accreditation. This module is available on the Australasian Pharmacy Guild (Guild Learning and Development).

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Fook, J. (2015). Reflective practice and critical reflection. In J. Lishman (Ed.), Handbook for practice learning in social work and social care (pp. 440–455). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2007). Practising critical reflection: A resource handbook. Open University Press.

- Fook, J., White, S., & Gardner, F. (2006). Critical reflection: A review of contemporary literature and understandings. In S. White, J. Fook, & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in health and social care (pp. 3–20). Open University Press/McGraw-Hill Education.

- Fragkos, K. (2016). Reflective practice in healthcare education: An umbrella review. Education Sciences, 6(4), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030027

- Jorgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. Sage Publications.

- Morley, C. (2011). Critical reflection as an educational process: A practice example. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education Special Issue – Critical Reflection Method and Practice, 13(1), 7–28.

- Norrie, C., Hammond, J., D’Avray, L., Collington, V., & Fook, J. (2012). Doing it differently? A review of literature on teaching reflective practice across health and social care professions. Reflective Practice, 13(4), 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.670628

- Patil, T., Cash, P., Cant, R., Mummery, J., & Penney, W. (2019). The lived experience of Australian opioid replacement therapy recipients in a community-based program in regional Victoria. Drug and Alcohol Review, 38(6), 656-663. doi:10.1111/dar.12979

- Patil, T., Mummery, J., Salman, M., Cooper, S., & Williams, D. (2021). “[B]efore the training I just assumed they’ve done something bad”: Reporting on Professional Training for Pharmacy Assistants and Pharmacy Dispensary Technicians on Medication Assistant Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 17(7), 1250-1258.

- State of Victoria. (2019). Victorian allied health clinical supervision framework. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/health-workforce/allied-health-workforce

- Thompson, N., & Pascal, J. (2012). Developing critically reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 13(2), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.657795

- Tsingos, C., Bosnic-Anticevich, S., Lonie, J., & Smith, L. (2015). A model for assessing reflective practices in pharmacy education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 79(8), 124.

- Wilkinson, R., & Marmot, M. (1998). The solid facts: Social determinants of health. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/108082