Abstract

When intended parents choose to have donor sperm treatment (DST), this may entail wide-ranging and long-lasting psychosocial implications related to the social parent not having a genetic tie with the child, how to disclose donor-conception and future donor contact. Counselling by qualified professionals is recommended to help intended parents cope with these implications. The objective of this study is to present findings and insights about how counsellors execute their counselling practices. We performed a qualitative study that included 13 counsellors working in the 11 clinics offering DST in the Netherlands. We held a focus group discussion and individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews, which were fully transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis. The counsellors combined screening for eligibility and guidance within one session. They acted according to their individual knowledge and clinical experience and had different opinions on the issues they discussed with intended parents, which resulted in large practice variations. The counsellors were dependent on the admission policies of the clinics, which were mainly limited to regulating access to psychosocial counselling, which also lead to a variety of counselling practices. This means that evidence-based guidelines on counselling in DST need to be developed to provide consistent counselling with less practice variation.

Introduction

When men and women wish to embark on donor sperm treatment (DST) for procreation and do not organize this with a donor known to them, they look for medical assistance in a fertility clinic (ESHRE task force on Ethics and Law, Citation2002). The decision of intended parents to apply for donor-conception may entail wide-ranging and long-lasting psychosocial implications for themselves and their future children; the social parent and the child do not have a genetic tie, there is a third party in the family and parents and children need to cope with reactions from their wider family and social environment (Blyth, Citation2012; Culley, Hudson, & Rapport, Citation2013; Grace, Daniels, & Gillett, Citation2008; Jadva, Freeman, Kramer, & Golombok, Citation2010). Families with children after DST have to deal with anxiety about the lack of genetic ties and with non-disclosure or disclosing the genetic origins of their child (Golombok, Ilioi, Blake, Roman, & Jadva, Citation2017; Haimes, Citation1998; Indekeu, D’Hooghe, Daniels, Dierckx, & Rober, Citation2014; Kirkman, Citation2003; McWhinnie, Citation2000). In several Western countries, donor-anonymity is forbidden and practices on disclosure have shifted from secrecy to openness (Freeman, Zadeh, Smith, & Golombok, Citation2016; Isaksson, Sydsjö, Skoog Svanberg, & Lampic, Citation2012; Readings, Blake, & Casey, Citation2011; Söderström-Anttila, Sälevaara, & Suikkari, Citation2010). As parents are often uncertain about when and how to share donor-conception with their child, family and friends, how to consider the position of the donor and what to expect from possible future contact between their child and the donor, counselling on disclosure and possible future contact with the donor are of great value. Counselling is now advised as an integral part of DST (Cousineau & Domar, Citation2007; Daniels, Gillett, & Grace, Citation2009; ESHRE task force on Ethics and Law et al., Citation2007; Freeman et al., Citation2016; Greenfeld, Citation2008; Hammarberg, Carmichael, Tinney, & Mulder, Citation2008; Indekeu et al., Citation2013; Indekeu et al., Citation2014; Isaksson et al., Citation2012; McWhinnie, Citation2001). The Ethics Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has recommended that men and women applying for DST are not to be treated before being given the opportunity to receive specialist psychosocial counselling (ASRM, Citation2013). In the UK it is a statutory requirement that anyone contemplating DST is offered proper psychosocial counselling, which is outlined in the Code of Practice of the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA) (HFEA, Citation2017).

The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) recently developed evidence-based guidelines on ‘Routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction’. These guidelines help fertility staff to recognize when patients with fertility problems need specialized psychosocial care, but they do not offer any specific recommendations on psychosocial care for men and women opting for donor-conception (ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guide Development Group; Gameiro et al., Citation2015). The paradoxical situation has, therefore, arisen whereby psychosocial counselling is recommended for men and women applying for DST, but evidence-based guidelines for counselling in DST are lacking. It is, therefore, not clear how counsellors should execute their practice. The aim of this study was, therefore, to gain insight into the actual counselling practices of psychosocial counsellors as a first step towards development of evidence-based guidelines in DST counselling for intended parents.

Materials and methods

Context

In The Netherlands, DST is offered in 11 clinics: five university hospitals, three non-university hospitals and three independent clinics. Nine of those clinics offer DST using sperm from their donor sperm bank. Intended parents cannot access sperm donors directly (i.e. staff choose for them), but they can bring their own sperm donor; two of the university hospitals exclusively offer treatment when intended parents have a self-known sperm donor. All clinics treat heterosexual and lesbian couples and single women, but two clinics only do so when couples come with a self-known donor and one clinic does not offer DST to single women. All donors are identifiable since 2004, according to Dutch law, giving children the right of access to identifying information about their donor on reaching the age of 16 (Dutch Law: Wet donorgegevens kunstmatige bevruchting, Citation2002). Psychosocial counselling for intended parents by professional counsellors has been gradually introduced in Dutch clinics from 1989 onwards, but the Dutch law does not prescribe mandatory psychosocial counselling. In all clinics, the national protocol on moral contra-indications for infertility counselling has to be followed, which states that screening intended parents is necessary in view of the welfare of the future child, but this protocol does not provide guidelines for counselling (NVOG Modelprotocol, Citation2010).

We performed a qualitative study, involving a focus group discussion and individual semi-structured interviews conducted from January to September 2014, with all Dutch professional counsellors who counsel intended parents requesting DST in these clinics. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 2013 and were allowed without approval of the consulted medical ethical committee, as none of the participants had to undergo any adverse intervention.

Recruitment

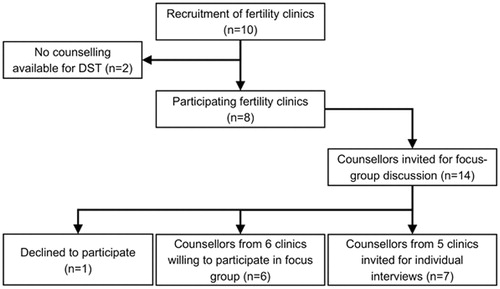

This study was performed by one of the 11 fertility clinics in the Netherlands and we recruited counsellors from the 10 other fertility clinics offering DST. We sent all counsellors from the 10 clinics an information letter by email or surface mail with the request to participate in the study.

Two clinics did not employ counsellors for DST as they did not offer professional psychosocial counselling in DST. All counsellors of the other eight clinics were willing to participate. First, we intended to organize a focus group discussion to explore how the counsellors execute their counselling. Second, based on the findings of the focus group discussion we intended to explore more in depth their individual views and experiences by holding face-to-face interviews. We invited all 14 counsellors of these clinics for a focus group discussion at a given date by post or email. Depending on the counsellors’ choice to participate in the focus group discussion, we invited the non-participants for individual interviews. Six of the counsellors were willing and able to participate in the focus group discussion. Seven of the eight counsellors who did not participate were willing to be interviewed individually at a date of their convenience. One counsellor did not want to participate as she had only been employed for a short period and felt that her experience was too limited.

Data collection

Three of the four authors were based in the Academic Medical Centre (AMC) of the University of Amsterdam and one at the Anthropology Department in the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences of the University of Amsterdam. Prior to the start of the focus group discussion, confidentiality was assured and the first author (MV) explained the aim of the meeting. MV, a counsellor at the Centre for Reproductive Medicine at the AMC, did not take part in the discussion but participated as an observer. Before the start of the focus group discussion, the counsellors completed a questionnaire on their age, education and specific education in DST counselling, years of practice in DST and years of employment in DST counselling.

A moderator (a human resources director who had recently been involved in a study on DST as an interviewer) led the focus group discussion guided by a topic list based on the clinical experiences of the first author and the results of a previous study on psychosocial counselling of parents who conceived through DST (Visser, Gerrits, Kop, van der Veen, & Mochtar, Citation2016). The focus group discussion lasted about 2.5 h. The discussion was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The seven individual face-to-face interviews were conducted by MV between March and September 2014. MV informed the counsellors about the confidentiality of the interviews and asked them to fill out the same questionnaire on background data as the counsellors in the focus group discussion. The interviews were guided by the same topic list used for the focus group discussion, supplemented with topics that arose after analysing the focus group discussion. The interviews took 50–75 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

MV had never met three of the counsellors who participated in the focus group discussion and three of the counsellors who were individually interviewed. She had met the other seven counsellors once or several times before. Before and after the focus group discussion and also before and after the individual interviews, the fact that MV was a colleague, though not known to everyone, had been discussed. The participants of the focus group had valued the possibility to discuss the topics with colleagues in a safe atmosphere, as it gave them the chance to reflect on their own experiences.

Throughout the study, MV was aware of her own views and practices with regard to counselling intended parents and had discussed these with two senior researchers from the research team (TG and MM) to minimize the extent to which her personal opinions affected the content of the data collection and the outcome of the analysis. In addition, MV shared the coding process and the meaningful text units in the transcripts on a regular basis with a senior researcher (TG) to increase the trustworthiness of the analysis (Giorgi, Citation2000).

Data analysis

MV analysed the transcriptions of the focus group discussion and the individual interviews using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis is an established technique in qualitative research, which uses an iterative process of coding with the aim to identify themes within the data. First, the lead author (MV) analysed the transcript of the focus group discussion by means of line by line coding to generate themes related to the counselling practices of the counsellors. Based on this initial coding we constituted a coding list and a thematic scheme. Subsequently, MV once more read the transcript to search for repeating ideas expressed by different participants and additional themes. Next, MV used a coding tree and thematic scheme to analyse the individual interviews and we compared codes and themes to refine the thematic scheme. MV read the transcripts again to ensure the scheme was comprehensive and appropriate (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Lucassen & Olde Hartman, Citation2007; Then, Rankin, & Ali, Citation2014). To prevent bias caused by any preconceived ideas she might have, MV discussed the coding and development of the thematic scheme with TG, who also read parts of the interviews during this coding process. To ensure consistency, any discrepancies were also discussed with MM and FV until consensus was met (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

To generate meanings related to numbers from the qualitative data, when describing the results, we expressed numbers as follows (Sandelowski, Citation2001): all counsellors (n = 13), most counsellors (n = 10–12), several counsellors (n= 7–9), some counsellors (n= 4–6), a few counsellors (n= 1–3) and none of the counsellors (n= 0). We performed all analyses with the MaxQDA software program (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for qualitative data analysis (MaxQDA, Citation2011). MaxQDA is software to organize, analyse and visualize data of qualitative and mixed-method research. All forms of data can be collected electronically and it has functionalities ranging from transcription to statistically analysis. In reporting the data, we used the COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative research (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, Citation2007). COREQ is a 32-item checklist to help researchers to report important aspects of the research team, study methods, context of the study, findings, analysis and interpretations.

Results

The data on the counselling practices of 13 counsellors working in eight clinics are summarized in . The counselling policies of the clinics included procedural aspects like setting the criteria for access to psychosocial counselling in DST and establishing the process of decision-making after the actual counselling sessions. Three clinics had a policy of mandatory counselling for men and women of all family types. In all clinics, counselling was mandatory for DST requests with a self-known sperm donor, regardless of family type and in six clinics counselling was mandatory for all single women. Several counsellors were content with the policy of the clinic, but about half of the counsellors wished to have a better say in the counselling policy and felt that access to psychosocial counselling should be obvious for all intended parents, though they were also loyal to the policy of their clinics.

The decision-making regarding eligibility for DST after counselling varied. In three clinics, this was undertaken by medical ethical committees in cases of all single women and when a medical doctor and/or counsellor had any concerns about the eligibility of the intended parents in cases of heterosexual and lesbian couples. These committees usually consisted of medical staff, including gynaecologists, geneticists, urologists, obstetricians, counsellors(s), nurses and representatives of the ethics department of the clinic. In three other clinics, the findings of the counsellor were discussed by a team of medical doctors, nurses and the counsellor only in cases where the counsellor and/or medical doctor had any concerns about the intended parents, regardless of family type. In two clinics, the counsellors discussed the counselling findings with a colleague counsellor and with the whole team in case of disquieting findings. In all clinics, patients had been informed about these procedures in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the Dutch Institute for Psychologists, which is based on the Law for Protection of Personal Information (Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen, Citation2015).

The characteristics of the counsellors are summarized in . The average age of the 13 counsellors (all women) was 49.1 years, ranging from 31 to 64 years. Nine of them had a university degree in psychology and four a higher professional education as a social worker. None of the counsellors had received specific education on DST counselling. All counsellors had shaped their own counselling practice individually by participating in conferences, reading literature and consulting with colleagues. The counsellors did not mention specific literature they relied on. Five counsellors from three clinics followed the local guidelines of their clinic for counselling in DST, based on clinical practice and literature on implications of DST, since they were aware of the lack of evidence-based guidelines. One counsellor mentioned the Handbook for Fertility Counseling on which she relied (Covington & Burns, Citation2006). None of the counsellors used psychological measuring scales. Five counsellors held consultations with colleagues on a regular basis to exchange knowledge and experiences, and to reflect on their own feelings and values.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the counsellors.

The counsellors had an average of 8.3 years of DST counselling experience, ranging from 1.5 to 33 years; six of them in a university hospital, one in a general hospital, five in an independent clinic and one as an independent counsellor in connection to a general hospital. After analysing the focus group discussion and individual interviews, seven themes emerged: eligibility screening; guidance; secrecy and disclosure; the position of the social parent; the absence of the father; the position of the donor and guidance after DST.

Eligibility screening

Most counsellors combined screening and guidance for intended parents in a 1 h counselling session, which was in line with the policy of their clinic. Nevertheless, they felt uncomfortable about combining these two tasks, as they felt that it prevented intended parents from speaking freely about their concerns and uncertainties out of fear for judgement and possibly being denied access to DST. Overall, the counsellors discussed the choice for DST and they assessed mental stability, stability of the relationship, stability of the network of friends and family, disclosure to the child and their views on the future donor. With single women, they assessed these issues more extensively and in case of a known donor they discussed more specifically the expectations of all parties involved regarding the position of the donor, his partner and future disclosure to the child and to children of the donor.

In case of disquieting findings, such as mental-health problems, socio-economic deprivation, poor social networks, poor relationships with parents or a combination of these issues, a multi-disciplinary deliberation about how to proceed was the next step in all clinics, regardless of family type or whether the donor was known to the intended parents or not.

Guidance

In general, the main focus of guidance was to support intended parents who felt uncertain about choosing DST, to assist them in their choice between a known donor or a sperm bank donor, to help them reflect on the possible implications of disclosure, to reflect on future donor contact and to advise them on how to deal with DST in relation to their child and to significant people around them. Some counsellors routinely offered such guidance for all family types, regardless of the origin of the donor, due to the recognition that DST has psychosocial impacts on all intended parents and offering easy access to guidance can help them to share their questions and feelings. The other counsellors did not routinely offer guidance, stemming from the view that couples themselves could ask for guidance when needed. Most counsellors felt that routinely offering guidance for single women and for intended parents with a known donor was always important, as they are in a more vulnerable position.

Secrecy and disclosure

Based on their individual knowledge and clinical experience, all counsellors felt that secrecy about the genetic origins of the future child could cause difficulties in families, both for the parents who would then have to live with this secret and for the children because they might sense that something is wrong or discover donor conception by accident. Most counsellors explored whether and how intended heterosexual parents thought they would disclose and whether the man and the woman agreed or disagreed with one another. When intended parents asked for advice, all counsellors told them that disclosure should be seen as a process during the child’s entire upbringing from a young age.

Almost all counsellors had the opinion that discussing disclosure with lesbian and single women was not necessary as they felt it was obvious that children would ask their mothers about their father. A few counsellors always discussed disclosure with lesbian and single women, because in their experience those women had also had questions about when and how to talk with their child about their genetic origins and they feared rejection by their future child.

Most counsellors explored whether the intended parents had told or had the intention to tell their family and/or friends about DST. Several counsellors suggested that intended parents should do so as this could be supportive.

If intended parents said that they wanted to keep donor conception a secret out of fear of rejection by their family and/or strong feelings of shame, most counsellors paid attention to their feelings of loss and grief and discussed disclosure of donor conception in relation to their anxieties more extensively. Still, most counsellors felt that in the end the decision of the intended parents should be respected.

The position of the social parent

Several counsellors discussed the position of the social parent (i.e. the parent who is not genetically related to the future child), when the intended social parent showed worry about being rejected by their future child or when he or she felt uncomfortable talking about the donor.

For heterosexual couples, social parenthood was placed in the context of male infertility and these counsellors explored how the couples had so far coped with male infertility, as they had experienced that infertile men often fear rejection by their wife or their future donor-conceived child. For lesbian couples, only a few counsellors discussed the position of the social parent because they had experienced that social mothers might have feelings of jealousy, though these feelings were often not openly expressed by all lesbian women themselves. Most counsellors, however, felt that lesbian women who choose DST are autonomous, well-educated and able to handle these feelings.

The absence of a father

With lesbian couples several counsellors and with single women most counsellors, discussed the possible implications of their future child not having a father in his/her life, as they felt that not having a father could be difficult for the child. These counsellors thought that it was of value for the identity of children to be able to build a close relationship with both a male and a female adult person and that these children needed a male role model in their lives. They did not address this issue if a known donor would play a role in the life of a child. The other counsellors did not share this point of view with regard to lesbian couples, as they felt that having two parents would compensate for not having a father.

The position of the donor

With intended parents of all family types, most counsellors discussed the position of the donor to provide them with an understanding of what this could mean for them and to support them in talking freely with their child about the donor.

Most counsellors advised intended parents that they could best refer to the donor as ‘donor’. A few counsellors felt that any term could be used to refer to the donor, depending on what parents themselves felt was the best for their child and/or for themselves. The counsellors had conflicting opinions on what to recommend to lesbian couples and single women if their child asked about their father. Some counsellors advised them to answer ‘you don’t have a father’ in order not to confuse the child, while other counsellors felt that telling the child that he/she has no father might confuse the child and advised to answer ‘you have a donor-father’.

When intended parents had chosen for a known donor, all counsellors discussed the position of the donor in the family and how to talk about him, regardless of family type. In these cases, the counsellors discussed the expectations of all parties involved regarding the position of the donor.

Guidance after DST

All counsellors except one offered intended parents of all family types counselling once they had become pregnant after DST or after a child had been born, but parents seldom returned to the clinic for counselling. When parents did come, some counsellors had experienced that they were mainly heterosexual couples and that they generally had questions about when and how to disclose donor conception to their child and sometimes about the position of the social father. According to these counsellors, most parents appreciated talking about these subjects at that stage.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the practices of Dutch counsellors in DST. Our findings show that counselling practices were shaped by the individual counsellors, based on their individual knowledge and clinical experience, their participation in conferences, their reading of existing literature and their consultation with colleagues. Some counsellors used local counselling protocols, based on clinical practice and knowledge on implications of DST. In a larger context, they were dependent on the counselling policies of the clinics, which were mainly limited to regulating access to psychosocial counselling. All counsellors offered intended parents counselling after DST and childbirth but recognized that when intended parents actually became parents, they seldom returned for counselling.

The strength of this study is that it examines the counselling practices, or lack thereof, of all psychosocial counsellors in all Dutch clinics that offer DST and that it uses a sequence of two valid techniques in qualitative research which enhances internal validity: first, a focus group discussion to explore the breadth of counselling practices followed by individual interviews to deepen understanding of the experiences and opinions which arose in the focus group discussion.

A limitation is that the study was conducted with a group of colleagues who were partly known to one another, so they could have been less likely to share information that might reflect on them negatively. A consequence may have been that actual inconsistencies in counselling practices were underrepresented. Although the topic of the study did contribute to their interest in the topic and made them motivated to exchange their ideas about their counselling practices and this motivation also stemmed from their wishes to contribute to more uniform counselling guidelines.

It remains unknown whether the practices of counsellors in other countries differ from those in the Netherlands and also whether they better fulfil the wishes of parents. This manuscript could provide tools and a sense of direction for how to look into this further.

The value that counsellors attached to reflecting on male infertility, discussing secrecy and disclosure, and reflecting on the donor and his position in the family are in line with the practice-based guidelines on psychosocial counselling on DST as developed by the British Infertility Counselling Association (BICA), the Infertility Counselling Network Germany (CNG) and the Australian and New Zealand Infertility Counsellors Association (ANZICA) (ANZICA, Citation2012; Crawshaw, Hunt, Monach, Pike, & Wilde, Citation2013; Thorn & Wischmann, Citation2009).

Many intended parents with identifiable donors appreciate counselling before DST, but feel it is crucial that they are able to speak freely about topics that are important to them without having the feeling that they are being judged with possible consequences for entering the DST programme (Visser et al., Citation2016). In this respect, the actual counselling practice is not in line with the wishes of intended parents. The same applies to the discussion of disclosure: most counsellors did not discuss disclosure with lesbian and single women, while parents of all family types feel this is important (Visser et al., Citation2016). Also, discussing the position of the social parent (which only a few counsellors in this study said they did and then restricted this only to heterosexual couples) was valued by lesbian as well as heterosexual parents (Visser et al., Citation2016).

Disclosure, the lack of a genetic tie, the position of the donor and possible future interaction between the donor and child were issues that the counsellors found most important to discuss, which mirrors a previous study on counselling in gamete donation in general (Dutch Law: Wet donorgegevens kunstmatige bevruchting, Citation2002). For the practice of counselling it also seems valuable to discuss the experiences of parents that feelings about the position and role of the donor in the family can change over time (Daniels et al., Citation2009; Dutch law: Wet donorgegevens kunstmatige bevruchting, 2002; Gartrell, Bos, Goldberg, Deck, & van Rijn-van Gelderen, Citation2015; Hammarberg et al., Citation2008; Indekeu et al., Citation2013; Indekeu et al., Citation2014; Laruelle, Place, & Demeesterre, Citation2011; Salter-Ling, Hunter, & Glover, Citation2001; Scheib, Riordan, & Rubin, Citation2003; Visser et al., Citation2016; Zadeh, Freeman, & Golombok, Citation2016).

Of note is that all counsellors offered extended counselling once parents became pregnant or gave birth to a child, in order to give further guidance on coping with possible implications of having a donor-conceived child, the disclosure process and/or feelings about the position of the donor. In practice, hardly any parents returned to the clinic to take up this offer. One reason might be that the guidance before treatment is not offered separately from screening and that they do not feel safe. In cases where parents would appreciate being offered extended counselling on those issues, this is regrettable. Another reason might be that the clinics remind them of their treatment which belongs to a different phase of their lives.

In a few studies, parents expressed their wish for professional support when raising their children (for example to cope with the disclosure process) but did not know where to go for such guidance (Lalos, Gottlieb, & Lalos, Citation2007; Söderström-Anttila et al., Citation2010; Visser et al., Citation2016). Over the last two decades, studies have been conducted on parents’ (non)-disclosure to their donor-offspring, which reveal that keeping DST a secret creates pressure and strain in their families; that parents do not regret telling their children about their genetic origins. Compared to non-disclosing families, mothers who have disclosed donor conception have less frequent and less severe arguments with their children; disclosure at a young age gives more positive family relationships and that there is more positive family functioning when parents share donor-conception with their child (Daniels et al., Citation2009; Daniels, Grace, & Gillett, Citation2011; Daniels, Lewis, & Gillett, Citation1995; Ilioi, Blake, Jadva, Roman, & Golombok, Citation2017; Isaksson, Skoog-Svanberg, Sydsjö, Linell, & Lampic, Citation2016; Landau, Citation1998; Leiblum & Aviv, Citation1997; Lycett, Daniels, Curson, & Golombok, Citation2004; Paul & Berger, Citation2007; Rumball & Adair, Citation1999; Scheib et al., Citation2003).

Sharing donor-conception is not easy, since we know that parents are uncertain how to deal with disclosure, that disagreement and uncertainty prevents them from telling and that the way parents share donor-conception with their child depends on their mindset before DST (Blake, Jadva, & Golombok, Citation2014; Blyth & Hunt, Citation1998; Crawshaw, Citation2008; Daniels et al., Citation2011; Indekeu et al., Citation2013; Leiblum & Hamkins, Citation1992; Nordqvist, Citation2012; Sälevaara, Suikkari, & Söderström-Anttila, Citation2013). Most of these studies call for professional assistance for parents to share donor-conception with their child. Parents choosing an identifiable donor show neutral to positive feelings regarding their decision (Gartrell et al., Citation2015; Scheib et al., Citation2003). Most children with an identifiable donor wish to receive information from him to learn about the donor and themselves. They wish to receive information about his motivation, his ancestry and his family relationships to have a better understanding of themselves and their identity (Beeson, Jennings, & Kramer, Citation2011; Hertz, Nelson, & Kramer, Citation2013; Jadva, Freeman, Kramer, & Golombok, Citation2009; Mahlstedt, LaBounty, & Kennedy, Citation2010; Rodino, Burton, & Sanders, Citation2011; Scheib, Riordan, & Rubin, Citation2005; Turner & Coyle, Citation2000).

A recent opinion paper stated that disclosure and directive counselling on disclosure cannot be justified because of a lack of empirical evidence on the well-being of children when parents share donor-conception (Pennings, Citation2017). This point of view has been challenged by others providing evidence that donor-offspring and their families benefit from openness, although, for obvious reasons, donor-children of non-disclosing families cannot be studied (Crawshaw et al., Citation2017; Golombok, Citation2017).

When eligibility screening is separated from guidance, intended parents can be encouraged to come for counselling on coping with the challenges of subsequent parenthood, but the clinics and counsellors need to be clear about their conflicting roles as gatekeepers and providers of guidance (Benward, Citation2015; Braverman, Citation2015; Crawshaw & Montuschi, Citation2014; Freeman et al., Citation2014; Indekeu et al., Citation2013; Norré & Wischmann, Citation2011). Since we know that parents may appreciate the availability of counselling after childbirth on issues like how to talk openly with their children about genetic and social relatedness, and about the donor and possible future contact, not-clinic based counselling by independent specialist counsellors might be helpful because the parents do not return to the clinics. Organizing outreach platforms for peer support, networks for parents and their families and specialist guidance, as in the UK and Australia, may be an important step forward in this respect.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Counsellors base their counselling on their individual knowledge and clinical experience and are dependent on the counselling policy of clinics, which is worrisome. More awareness and reflection are needed on how to prevent large practice variation regarding the content of counselling, to separate screening from guidance and to develop specialist counselling after DST for parents of all family types. In this respect, empirical knowledge about the wishes of (intended) parents and of donor-conceived offspring is a key to improving counselling practices in DST, to meet the varying needs of the (intended) parents.

This might ultimately lead to evidence-based guidelines specifically designed for DST, which is the way forward, as counselling in DST requires specific knowledge, such as knowledge about the implications of one parent being a social but not a genetic parent, the disclosure process and the process on the evolving position of the donor for the child and the family. Despite current literature and acknowledgement of the importance of psychosocial counselling in DST by institutions, such as ASRM and HFEA, evidence-based guidelines have not been developed so far, resulting in large variations in counselling practices as demonstrated by our results. Although the recent ESHRE guidelines on ‘Routine psychosocial care in infertility and medical assisted reproduction’ do offer clear information for clinicians treating infertile patients and help them to recognize when patients need specialized psychosocial care, they do not offer any recommendation for psychosocial care for men and women opting for DST (Gameiro et al., Citation2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the colleagues for their valuable contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Australian and New Zealand Infertility Counseling Association (ANZICA). (2012). Guidelines for Professional Standards of Practice Infertility Counseling. Retrieved from https://www.fertilitysociety.com.au/anzica/policy-documents/.

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine and Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology; The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (ASRM). (2013). Recommendations for gamete and embryo donation: A committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility, 99, 47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.037.

- Beeson, D.R., Jennings, P.K., & Kramer, W. (2011). Offspring searching for their sperm donors: How family type shapes the process. Human Reproduction, 26, 2415–2424. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der202.

- Benward, J. (2015). Mandatory counseling for gamete donation recipients: Ethical dilemmas. Fertility and Sterility, 104, 507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1154.

- Blake, L., Jadva, V., & Golombok, S. (2014). Parent psychological adjustment, donor conception and disclosure: A follow-up over 10 years. Human Reproduction, 29, 2487–2496. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu231.

- Blyth, E., & Hunt, J. (1998). Sharing genetic origins information in donor assisted conception: Views from licensed centres on HFEA donor information form (91) 4. Human Reproduction, 13, 3274–3277. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.11.3274.

- Blyth, E. (2012). Guidelines for infertility counseling in different countries: Is there an emerging trend? Human Reproduction, 19, 2046–2057. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des112.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braverman, A.M. (2015). Mental health counseling in third-party reproduction in the United States: Evaluation, psychoeducation, or ethical gatekeeping? Fertility and Sterility, 104, 501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.023.

- Cousineau, T.M., & Domar, A.D. (2007). Psychological impact of infertility. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 21, 293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.003.

- Covington, S.N., & Burns, L.H. (Eds.). (2006). Infertility counseling. A comprehensive handbook for clinicians (pp. 212–235). Cambridge: University Press.

- Crawshaw, M. (2008). Prospective parents’ intentions regarding disclosure following the removal of donor anonymity. Human Fertility, 11, 95–100. doi: 10.1080/14647270701694282.

- Crawshaw, M., Hunt, J., Monach, J., Pike, S., & Wilde, R. (2013). British infertility counselling association guidelines for good practice in infertility counselling. Third edition 2012. Human Fertility, 16, 73–88. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2013.774217.

- Crawshaw, M., & Montuschi, O. (2014). It ‘did what it said on the tin’ – participant’s views of the content and process of donor conception parenthood preparation workshops. Human Fertility, 17, 11–20. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.881562.

- Crawshaw, M., Adams, D., Allan, S., Blyth, E., Bourne, K., Brügge, C., … Zweifel, J.E. (2017). Disclosure and donor-conceived children. Human Reproduction, 32, 1535–1536. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex107.

- Culley, L., Hudson, N., & Rapport, F. (2013). Assisted conception and South Asian communities in the UK: Public perceptions of the use of donor gametes in infertility treatment. Human Fertility, 16, 48–53. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2013.773091.

- Daniels, K.R., Lewis, G.M., & Gillett, W. (1995). Telling donor insemination offspring about their conception: The nature of couples’ decision-making. Social Science & Medicine, 40, 1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00251-N.

- Daniels, K., Gillett, W., & Grace, V. (2009). Parental information sharing with donor insemination conceived offspring: A follow-up study. Human Reproduction, 24, 1099–1105. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den495.

- Daniels, K.R., Grace, V.M., & Gillett, W.R. (2011). Factors associated with parents’ decision to tell their adult offspring about the offspring’s donor conception. Human Reproduction, 26, 2783–2790. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der247.

- Dutch Law: Wet donorgegevens kunstmatige bevruchting. (2002). [Law Donordata Artificial Insemination]. Retrieved from http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0013642/2016-08-01.

- ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law. (2002). III. Gamete and embryo donation. Human Reproduction, 17, 1407–1408. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.5.1407.

- ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law, Pennings, G., de Wert, G., Shenfield, F., Cohen, J., Tarlatzis, B., & Devroey, P. (2007). ESHRE task force on ethics and law 13: The welfare of the child in medically assisted reproduction. Human Reproduction, 22, 2585–2588. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem237.

- Freeman, T., Jolley, G., Baum, F., Lawless, A., Javanparast, S., & Labonté, R. (2014). Community assessment workshops: A group method for gathering client experiences of health services. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22, 47–56. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12060.

- Freeman, T., Zadeh, S., Smith, V., & Golombok, S. (2016). Disclosure of sperm donation: A comparison between solo mother and two-parent families with identifiable donors. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 33, 592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.08.004.

- Gameiro, S., Boivin, J., Dancet, E., de Klerk, C., Emery, M., Lewis-Jones, C., … Vermeulen, N. (2015). ESHRE guideline: Routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction—a guide for fertility staff. Human Reproduction, 11, 2476–2485. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev177.

- Gartrell, N.K., Bos, H., Goldberg, N.G., Deck, A., & van Rijn-van Gelderen, L. (2015). Satisfaction with known, open-identity, or unknown sperm donors: Reports from lesbian mothers of 17-year-old adolescents. Fertility and Sterility, 103, 242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.019.

- Giorgi, A. (2000). Concerning the application of phenomenology to caring research. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 14, 11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2000.tb00555.x.

- Golombok, S., Ilioi, E., Blake, L., Roman, G., & Jadva, V. (2017). A longitudinal study of families formed through reproductive donation: Parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent adjustment at age 14. Developmental Psychology, 53, 1966–1977. doi: 10.1037/dev0000372.

- Golombok, S. (2017). Disclosure and donor-conceived children. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 32, 1532–1536. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex104.

- Grace, V.M., Daniels, K.R., & Gillett, W. (2008). The donor, the father, and the imaginary constitution of the family: Parents’ constructions in the case of donor insemination. Social Science & Medicine, 66, 301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.029.

- Greenfeld, D.A. (2008). The impact of disclosure on donor gamete participants: Donors, intended parents and offspring. Review. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 20, 265–268. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32830136ca.

- Haimes, E. (1998). Gamete and embryo donation: Ethical implications for families. Human Fertility, 1, 30–34. doi: 10.1080/1464727982000198081.

- Hammarberg, K., Carmichael, M., Tinney, L., & Mulder, A. (2008). Gamete donors’ and recipients’ evaluation of donor counselling: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 48, 601–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00925.x.

- Hertz, R., Nelson, M.K., & Kramer, W. (2013). Donor conceived offspring conceive of the donor: The relevance of age, awareness, and family form. Social Science & Medicine, 86, 52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.001.

- Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA). (2017). Code of practice (8th ed.). London: HFEA.

- Ilioi, E., Blake, L., Jadva, V., Roman, G., & Golombok, S. (2017). The role of age of disclosure of biological origins in the psychological wellbeing of adolescents conceived by reproductive donation: A longitudinal study from age 1 to age 14. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 315–324. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12667.

- Indekeu, A., Rober, P., Schotsmans, P., Daniels, K.R., Dierickx, K., & D'Hooghe, T. (2013). How couples’ experiences prior to the start of infertility treatment with donor gametes influences the disclosure decision. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, 76, 125–132. doi: 10.1159/000353901.

- Indekeu, A., D’hooghe, T., Daniels, K.R., Dierckx, K., & Rober, P. (2014). When ‘sperm’ becomes ‘donor’: Transitions in parents’ views of the sperm donor. Human Fertility, 17, 269–277. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.910872.

- Isaksson, S., Sydsjö, G., Skoog Svanberg, A., & Lampic, C. (2012). Disclosure behavior and intentions among 111 couples following treatment with oocytes or sperm from identity-release donors: Follow-up at offspring age 1–4 years. Human Reproduction, 27, 2998–3007. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des285.

- Isaksson, S., Skoog-Svanberg, A., Sydsjö, G., Linell, L., & Lampic, C. (2016). It takes two to tango: Information-sharing with offspring among heterosexual parents following identity-release sperm donation. Human Reproduction, 31, 125–132. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev293.

- Jadva, V., Freeman, T., Kramer, W., & Golombok, S. (2009). The experiences of adolescents and adults conceived by sperm donation: Comparisons by age of disclosure and family type. Human Reproduction, 24, 1909–1919. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep110.

- Jadva, V., Freeman, T., Kramer, W., & Golombok, S. (2010). Experiences of offspring searching for and contacting their donor siblings and donor. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 20, 523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.01.001.

- Kirkman, M. (2003). Parents’ contributions to the narrative identity of offspring of donor-assisted conception. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 57, 2229–2242. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00099-6.

- Lalos, A., Gottlieb, C., & Lalos, O. (2007). Legislated right for donor- insemination children to know their genetic origin: A study of parental thinking. Human Reproduction, 22, 1759–1768. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem063.

- Landau, R. (1998). Secrecy, anonymity, and deception in donor insemination: A genetic, psycho. Social and Ethical Critique. Social Work in Health Care, 28, 75–89. doi: 10.1300/J010v28n01_05.

- Laruelle, C., Place, I., & Demeesterre, I. (2011). Anonymity and secrecy options of recipient couples and donors, and ethnic origin influence in three types of oocyte and ethnic donation. Human Reproduction, 26, 382–390. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq346.

- Leiblum, S.R., & Hamkins, S.E. (1992). To tell or not to tell: Attitudes of reproductive Endocrinologists Concerning disclosure to offspring of conception via assisted insemination by donor. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 13, 267–275. doi: 10.3109/01674829209009199.

- Leiblum, S.R., & Aviv, A.L. (1997). Disclosure issues and decisions of couples who conceived via donor insemination. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 18, 292–300. doi: 10.3109/01674829709080702.

- Lucassen, P.L.B.J., & Olde Hartman, T.C. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek [qualitative research]. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Lycett, E., Daniels, K., Curson, R., & Golombok, S. (2004). Offspring created as a result of donor insemination: A study of family relationships, child adjustment and disclosure. Fertility and Sterility, 82, 172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.039.

- Mahlstedt, P.P., LaBounty, K., & Kennedy, W.T. (2010). The views of adult offspring of sperm donation: Essential feedback for the development of ethical guidelines within the practice of assisted reproductive technology in the United States. Fertility and Sterility, 93, 2236–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.119.

- MAXQDA. (2011). Software for qualitative data analysis. Berlin: VERBI Software - Consult – Sozialforschung GmbH.

- McWhinnie, A. (2000). Families from assisted conception: Ethical and psychological issues. Human Fertility (Cambridge, England), 3, 13–19. doi: 10.1080/1464727002000198641.

- McWhinnie, A. (2001). Gamete donation and anonymity: Should offspring from donated gametes continue to be denied knowledge of their origins and antecedents? Human Reproduction, 16, 807–817. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.807.

- Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen. (2015). [Dutch society of Psychologists]. Beroepscode [Code of Ethics]. Retrieved from http://www.psynip.nl/uw-beroep/beroepsethiek/beroepscode.

- Nordqvist, P. (2012). ‘Origins and originators: Lesbian couples negotiating parental identities and sperm donor conception. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14, 297–311. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.639392.

- Norré, J., & Wischmann, T. (2011). The position of the fertility counsellor in a fertility team: A critical appraisal. Human Fertility, 14, 154–159. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2011.580824.

- NVOG Modelprotocol. (2010). Mogelijke morele contra-indicaties bij vruchtbaarheidsbehandelingen. [Possible moral contra-indications in fertility treatment]. Retrieved from https://www.nvog.nl/kwaliteitsdocumenten/protocollen/.

- Paul, M.S., & Berger, R. (2007). Topic avoidance and family functioning in families conceived with donor insemination. Human Reproduction, 22, 2566–2571. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem174.

- Pennings, G. (2017). Disclosure of donor conception, age of disclosure and the well-being of donor offspring. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 32, 969–973. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex056.

- Readings, J., Blake, L., & Casey, P. (2011). Secrecy, disclosure and everything in-between: Decisions of parents of children conceived by donor insemination, egg donation and surrogacy. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 22, 485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.01.014.

- Rodino, I.S., Burton, P.J., & Sanders, K.A. (2011). Donor information considered important to donors, recipients and offspring: An Australian perspective. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 22, 303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.11.007.

- Rumball, A., & Adair, V. (1999). Telling the story: Parents’ scripts for donor offspring. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 14, 1392–1399. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.5.1392.

- Sälevaara, M., Suikkari, A.M., & Söderström-Anttila, V. (2013). Attitudes and disclosure decisions of Finnish parents with children conceived using donor sperm. Human Reproduction, 28, 2746–2754. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det313.

- Salter-Ling, N., Hunter, M., & Glover, L. (2001). Donor insemination: Exploring the experience of treatment and intention to tell. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 19, 175–186. doi: 10.1080/02646830124445.

- Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 24, 230–240. doi: 10.1002/nur.1025.

- Scheib, J.E., Riordan, M., & Rubin, S. (2003). Choosing identity-release sperm donors: The parents’ perspective 13–18 years later. Human Reproduction, 18, 1115–1127. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg227.

- Scheib, J., Riordan, M., & Rubin, S. (2005). Adolescents with open-identity sperm donors: Reports from 12–17 year olds. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 20, 239–252. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh581.

- Söderström-Anttila, V., Sälevaara, M., & Suikkari, A.M. (2010). Increasing openness in oocyte donation families regarding disclosure over 15 years. Human Reproduction, 25, 2535–2542. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq194.

- Then, K.L., Rankin, J.A., & Ali, E. (2014). Focus group research: What is it and how can it be used. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 24, 16–22. Retrieved from http://www.cccn.ca/content.php?doc=234.

- Thorn, P., & Wischmann, T. (2009). German Guidelines for psychosocial counseling in the area of gamete donation. Human Fertility, 12, 73–80. doi: 10.1080/14647270802712728.

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32- item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Turner, A.J., & Coyle, A. (2000). What does it mean to be a donor offspring? The identity experience of adults conceived by donor insemination and the implications for counselling and therapy. Human Reproduction, 15, 2041–2051. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.9.2041.

- Visser, M., Gerrits, T., Kop, F., van der Veen, F., & Mochtar, M. (2016). Exploring parents’ feelings about counseling in donor sperm treatment. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 37, 156–163. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2016.1195806.

- Zadeh, S., Freeman, T., & Golombok, S. (2016). Absence of presence? Complexities in the donor narratives of single mothers using sperm donation. Human Reproduction, 31, 117–124. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev275.