ABSTRACT

A substantial amount of research in cultural geography has been dedicated to the mundane or everyday living with diversity, yet little has been done in relation to linguistic diversity and the ways in which individuals experience the city through this particular form of diversity. This paper addresses how geographers can build on and assist in contemporary sociolinguistic scholarship to understand how individuals experience urban social diversity while taking account of the sound of spoken language in public space. Specifically, the paper highlights the significance of what I have named linguistic sound walks as a method to capture both the immediate sensory experience of the city’s linguistic soundscape while opening up ways to discuss and reflect on how linguistic diversity affects the experience of spatial and social diversity. Drawing on fieldwork in the inner-city of Amsterdam, the study illustrates how these linguistic sound walks represent a potential resource to reflect on the relationship between the sound of spoken languages and the experience of spatial and social diversity in the city, bridging the gap between the fields of geography and sociolinguistics.

RÉSUMÉ

Une large quantité de recherche dans la géographie culturelle a été dédiée à la diversité dans la vie courante ou quotidienne, mais peu de travail a été fait sur la diversité linguistique et les façons dont les personnes vivent la ville à travers cette forme particulière de diversité. La présente communication examine les façons dont les géographes peuvent enrichir et aider le courant de recherche sociolinguistique contemporain afin de comprendre comment les personnes vivent la diversité sociale urbaine tout en prenant en compte les sons de la langue parlée dans l’espace public. Plus précisément, cette communication met en valeur l’importance de ce que j’appelle les promenades de sons linguistiques comme méthode de capture d’expérience sensorielle immédiate de l’environnement sonore linguistique de la ville tout en ouvrant des avenues pour une discussion et une réflexion sur la façon dont la diversité linguistique change l’expérience des diversités spatiale et sociale. En faisant appel à l’étude sur le terrain qui a pris place dans le centre-ville d’Amsterdam, cette recherche illustre comment ces promenades de sons linguistiques représentent une ressource possible pour réfléchir sur les liens entre les sons des langues et l’expérience de la diversité spatiale et sociale dans la ville, comblant l’écart entre les domaines de la géographie et de la sociolinguistique.

RESUMEN

Se ha dedicado una gran cantidad de investigación en geografía cultural a la vida cotidiana y mundana con la diversidad, pero se ha hecho poco en relación con la diversidad lingüística y las formas en que los individuos experimentan la ciudad a través de esta forma particular de diversidad. Este artículo aborda cómo los geógrafos pueden desarrollar y ayudar en la investigación sociolingüística contemporánea para comprender cómo las personas experimentan la diversidad social urbana mientras toman en cuenta el sonido del lenguaje hablado en el espacio público. Específicamente, el artículo resalta la importancia de lo que he denominado caminatas de sonido lingüístico como un método para capturar tanto la experiencia sensorial inmediata del paisaje sonoro lingüístico de la ciudad como al abrir formas de discutir y reflexionar sobre cómo la diversidad lingüística afecta la experiencia de la diversidad espacial y social. Basándose en el trabajo de campo en el centro de la ciudad de Amsterdam, el estudio ilustra cómo estas caminatas lingüísticas de sonido representan un recurso potencial para reflexionar sobre la relación entre el sonido de las lenguas habladas y la experiencia de la diversidad espacial y social en la ciudad, cerrando la brecha entre los campos de la geografía y la sociolingüística.

Introduction

Many European cities are undergoing a great diversification of their population as a result of increased international and intra-national mobility in this ‘age of migration’ (Castles & Miller, Citation2003). Scholars have looked for new ways to address the condition of increasing social diversification. Different labels have been used to denote this increase of diversity: majority-minority cities (Crul, Citation2016), super-diversity (Vertovec, Citation2007, Citation2010), hyper-diversity (Tasan-Kok, Van Kempen, Mike, & Bolt, Citation2014) or complex diversity (Kraus, Citation2012), albeit there are some small differences in the meaning attached to these terms. Additionally, many scholars have started to focus on how ‘countless residents successfully live with difference on a daily basis in cities marked by cultural diversity’ (Fincher, Iveson, & Leitner, Citation2014, p. 1) by means of assessing everyday encounters and practices. Since multiculturalism is no longer an uncontested political philosophy or policy and has been abandoned by many policy makers (Hall, Citation2000), urban policies have increasingly been concerned with ‘mixing’ and creating social cohesion (Bolt & Van Kempen, Citation2013). The current effort of many urban researchers investigating the mundane or everyday living with diversity can be seen partly as an effect of changing policy foci: either by adhering to the goal of creating more socially mixed spaces and stimulating social cohesion, or by ‘countering [the] dominant narrative of segregated neighbourhoods, parallel societies, immigrant crime, failed integration and the like’ (Lapina, Citation2016, p. 33) and focusing on positive examples of living with diversity (see for instance: Bolt, Citation2017; Bolt, Visser, & Tersteeg, Citation2017; Eraydin, Tasan-Kok, & Vranken, Citation2010; Oosterlynck, Loopmans, Schuermans, Vandenabeele, & Zemni, Citation2016; Tasan-Kok et al., Citation2014; Tersteeg & Bolt, Citation2018).

Despite the growing interest in the experience of living and being in socially diverse cities and neighbourhoods, there seems to be a lack of attention towards linguistic diversity. Geographers have traditionally been more occupied with language as part of (national) identity and language planning (e.g. Chríost, Citation2001; Chríost & Aitchisont, Citation1998; Knox, Citation2001; Segrott, Citation2001; Wise, Citation2006), with language as discourses and narratives about places (e.g. Avila-Tapies & Dominiguez-Mujica, Citation2014; Kearns & Berg, Citation2002; Kielland, Citation2016; Mcgregor, Citation2005), or with the role language plays in the constitution of geographical epistemologies (e.g. Bajerski, Citation2011; Desforges & Jones, Citation2001; Drozdzewski, Citation2017; Hardwick & Davis, Citation2009; Helms, Lossau, & Oslender, Citation2005; Mattissek & Glasze, Citation2014; Morawski & Budke, Citation2017). I argue that investigating linguistic diversity in public space can give us important clues on how individuals experience the socially diverse city. Language remains ‘a potent marker of difference, with linguistic difference often elided with, or subsumed within, ethnic-racial differences’ (Chríost & Thomas, Citation2008, p. 2). Language serves both as a bridge and a wall, it simultaneously separates as it unites, and as a significant feature of difference should be given a more prominent role in research on social diversity.

This paper considers the potential of linguistic diversity in public space in the study of individual experiences of the socially diverse city. The main thread of the paper is to put forward the often forgotten role of the sound of spoken language in public spaces in the investigation of individual experiences of everyday diversity. I am particularly interested in the immediate sensory experience of linguistic diversity and the reflection on the ways in which linguistic diversity affects how individuals assess everyday encounters with social diversity. The first section discusses how linguistic diversity in public space tends to be neglected in geographical research on socially diverse cities. It draws on contemporary research in sociolinguistics to develop an understanding of how language is a significant feature of social diversity. The second section introduces what I have named linguistic sound walks as a fruitful method to capture the direct sensory experience of linguistic diversity as well as the effect it has on one’s experience of the socially diverse city. The last section presents a study in the inner-city of Amsterdam in which these linguistic sound walks have been deployed.

Fleeting encounters with diversity and the negligence of language in cultural geography

Present-day geographical research has been preoccupied with investigating the city as a site of connected diversities, either by assessing the way in which this has affected individual hybrid (territorial) identifications or by the way in which individuals think about one another when dealing with street-level diversity. Especially, the latter has been taken up by many investigating what this ‘throwntoghetherness’ (Massey, Citation2005) in a context with numerous ‘zones of encounter’ (Landry & Wood, Citation2012) means for prejudice and stereotypes towards social diversity; do they challenge these or are they indeed hardened? Two contradictory strands of thinking can be broadly distinguished. First, there are scholars adhering to Allport’s long-established ‘contact-hypothesis’ (Allport, Citation1954) which implies the weakening of prejudice occurs because encounter with difference lessens feelings of uncertainty and anxiety and broadens the knowledge and familiarity between strangers. This results in feelings of control and a sense of certainty in a complex society. In line with Allport, Ye (Citation2016) contends that ‘fleeting encounters challenge the fear of the Other embedded in relations with strangers, they disrupt stereotypical categories, and open up space for reflection and change afforded by its temporary nature’ (p. 78). These scholars postulate that in fleeting encounters with diversity rests a cosmopolitan optimism that brings about mutual understanding, open-mindedness, broadening of the horizon in terms of individual and collective experiences and hybrid cultures full of creative possibilities.

The second view is less optimistic about the effect of fleeting encounters with social difference. It suggests that these encounters in public space can result in politeness and civility towards a stranger, but do not necessarily have to result in less prejudice and stereotypes about the Other. Only ‘meaningful contact’ – referring to ‘contact that actually changes values and translates beyond the specifics of the individual moment into a more general positive respect for […] others’ (Valentine, Citation2008, p. 325) – may foster structural change. Sometimes encountering social difference can even lead to the hardening of differences. For instance, experiencing a negative encounter with a member of a minority group may foster or justify powerful negative generalizations about the whole minority population that the individual is seen to represent (Allport, Citation1954). Encounters with urban diversity may therefore also be a source of tension, discomfort, friction, and antagonism. This way of thinking is embedded in ‘postcolonial melancholia’ (Gilroy, Citation2006) and highlights how cultural racism and stigmatization of ‘foreigners’ is part of everyday life in the super-diverse city (Koefoed, Christensen, & Simonsen, Citation2016).

This questions the role of public space for the wider civic and political citizenship. As Amin (Citation2008) has set out, social interaction should not be considered a sufficient enough condition for collective culture to emerge, by which he separates himself from thinkers such as Benjamin and Simmel that have posed a strong and undisputed relationship between ‘the free and unfettered mingling of humans in open and well-managed public space […][and] forbearance towards others, pleasure in the urban experience, respect for the shared commons, and an interest in civic and political life’ (Amin, Citation2008, p. 6). Agreeing with this stance, it is not my intention to argue that the encounters with social diversity, in this paper enabled by the linguistic diversity of the city, show the plural sources of civic and political citizenship. As Doughty and Lagerqvist (Citation2016) contend, ‘vibrancy and diversity in a particular public space may not represent inclusive urban democracy overall’ (p. 60). It is however ‘still full of collective promise’ and portrays ‘sparks of civic and political and citizenship’ (Amin, Citation2008, p. 8). Amin places emphasis on the ‘situated multiplicity’ of public spaces, the total dynamic of human and non-human elements, and ‘the thrown-togetherness of bodies, mass and matter, and many uses and needs in a shared physical space’ (Amin, Citation2008, p. 8), which, ‘not confined to an overall plan or totality, is generative of a social ethos with potentially strong civic connotations’ (Amin, Citation2008, p. 10). Thus, it is through these public spaces that urban diversity can be experienced and valued (Doughty & Lagerqvist, Citation2016).

In the study of everyday diversity, there is a more prominent role given to ethnicity, nationality, religion and race, while language is merely treated as a proxy for ethnicity and often not further elaborated upon. This neglect and the call for the study of linguistic diversity by geographers in their assessment of social diversity and urban encounter was made eloquently ten years ago by Valentine, Sporton, and Bang Nielsen (Citation2008) who contend that

Talk and talking are central to the production of everyday spaces yet despite this pivotal position of language it has received little consideration by geographers. The importance of language in socio-spatial relations is, however, likely to become progressively more apparent as contemporary processes of globalization are intensifying cultural contact, such that linguistic diversity increasingly characterises both local and global context. This is both challenging traditional assumptions about the relationships between linguistic uniformity, cultural homogeneity and national identities as well as impacting on self-identities. (p. 385)

This study by Valentine et al. (Citation2008) investigates the ways in which British Somali youngsters make sense of their identities and affiliations in relation to language use and choice in the context of everyday encounters at home and at school. In this paper, I am mostly interested in the ways in which individuals assess the linguistic diversity in public places, i.e. in the streets of the city. As an intensified mobility of people has had (and is still having) its effect on the linguistic makeup of many European cities, individuals have to cope with a great urban multilingualism in public space and experience this in different ways. This increasing linguistic diversity also poses challenges to dominant linguistic ideologies which can influence how individuals think about linguistic diversity in certain places, either by adhering to these dominant ideas of the national language being an important feature of national unity and essential for social cohesion, resulting for instance in the idea that the dominant language should be spoken in public space and taking up an antagonistic stance towards minority languages. Or by defying these ideas and regarding increased mobility to (global) cities and increased urban multilingualism as inherently connected and a symbol for diversity, resulting in more toleration towards minority languages in public space.

Drawing from sociolinguistics: linguistic landscapes

Interestingly, over the past two decades, there has been a growing literature on the effects of super-diversity on language within sociolinguistics which can be helpful for geographers in their quest to understand how perceptions on spatial and social diversity are also shaped by the linguistic diversity in place. The literature on linguistic landscapes can be particularly valuable in understanding how place-specific conditions shape the linguistic make-up in a certain setting and how this may have significant consequences on individual perceptions of places and people. Following the original definition by Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997), the linguistic landscape refers to ‘the language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs and public signs on government buildings [which] combines to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region or urban agglomeration’ (p. 25) and these ‘may serve important informational and symbolic functions as a marker of relative power and status of the linguistic communities inhabiting the territory’ (p. 23). As such, these signs do not only convey a story, but they are also entrenched with social, cultural, material and ideological meanings (Blommaert, Citation2014). Additionally, these linguistic landscapes also help shaping the wider social reality (Shohamy, Ben- Rafael, & Barni, Citation2010) as they for instance portray the linguistic character of neighbourhoods and streets.

Language may give us hints about who mostly uses the place (and who does not), for whom the place is designed for (and for whom not), who is welcome and included (and whom is excluded) and who may find easy access to the place (and for whom this is not so straightforward). Through the linguistic landscape, individuals thus may get a sense of place, giving individuals tools to assess their own positionality within the context. It helps with processing feelings of in and out of place (see Cresswell, Citation1996).

Drawing from urban geography: shortcomings in the linguistic landscape literature

The linguistic landscape literature may help geographers finding new pathways to engage with linguistic diversity in their research. Likewise, geographers can contribute to debates amongst sociolinguists in better conceptualizing the linguistic landscape and broadening its scope. First, there is the important issue of place which is, in linguistic landscape studies, often treated as static and fixed rather than fluid, dynamic and in continuous change (see discussion in Shohamy et al., Citation2010). More traditional studies on the linguistic landscapes are mostly preoccupied with counting and mapping written languages in specific places ‘in order to uncover the hierarchy of linguistic resources in multilingual settings; [and] the global spread of English and the differences in language use in public and private signage’ (Moriarty, Citation2014, p. 458). This results in quantified snapshots of language in places, but this does not say much about the ongoing changes in the linguistic make-up of these places nor does it say much about the ways in which place identities are continuously changing in itself. For instance, it is rather uncommon to find accounts in these studies of unfixed or mobile languages such as texts on trams and buses, pamphlets, stickers and flyers, while these have the same significance in the linguistic order of places as fixed languages (Sebba, Citation2010). Also, over time, not only may the actual linguistic landscape change but also their symbolic meaning – for instance because of changing ideas about the relationship between language, place and identity. A good example of this is English on billboards in many large cities which have become mundane, uncontested and a token for a city’s global character.

Additionally, there are two other shortcomings in the study of linguistic landscapes that geographers may find possible solutions for the bias towards both written language and quantitative methods. Although sociolinguists have been writing about ways to go beyond written texts with other terms replacing the linguistic landscape such as the ‘semiotic landscape’ – referring to ‘the way written discourse interacts with other discursive modalities: visual images, nonverbal communication, architecture and the built environment’ (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010, p. 2) – or ‘geosemiotics’ – referring to ‘the study of the meaning systems by which language is located in the material world’ (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003, p. x) – it is striking that there is almost no attention towards language as sound and spoken words, or, what one may call, the linguistic soundscape. When dealing with language and place, it can be suggested that our subjective experience of place is not only based on the ways in which a place is written about and represented, but we also gain a sensory experience of place based on our own perceptions, be they visually (the linguistic landscape) or orally (the linguistic soundscape) of the place. To only account for the first and not for the latter gives only a part of the linguistic dimensions of place.

Moreover, the experience of the linguistic land- and soundscapes are not easy to capture through the methods deployed by many linguistic landscape scholars, often based on counting languages and giving a picture based on the distribution of these accounts. I agree with Moriarty (Citation2014) that the study of linguistic landscapes (and soundscapes) have ‘to consider the nuances of the given context, where local historical and symbolic processes are at play’ (p. 459). This may be broadened by investigating the consequences linguistic landscapes have on individual experiences of social diversity in place, which has had almost no attention in sociolinguistic literature.

The following sections present an introduction to a possible way for geographers to engage with linguistic diversity in their studies on experiences of spatial and social diversity in the city. I have named this method linguistic sound walks which complements traditional linguistic landscape methods by incorporating solutions to the above-mentioned shortcomings. In this regard, I have given emphasis (i) to place as a fluid and ever-changing concept (ii) to the linguistic soundscape (or heard linguistic landscape) and (iii) to the qualitative assessment of individual experiences of this linguistic soundscape in the socially diverse city. Based on exploring these soundscapes by moving through the city and building on so-called mobile methodologies, this approach may be able to bridge the gap between geography and sociolinguistics in the quest to unravel individual experiences of linguistic diversity in the assessment of spatial and social diversity. Before setting out the nature of the linguistic sound walk, I will first shed light on recent geographical scholarship dealing with mobility and soundscapes which forms the basis of the linguistic sound walk.

Everyday mobility and urban soundscapes

To experience the ‘throwntogetherness’ and everyday social diversity in cities is to share the urban arena with others. Encounters in the world rest on two characteristics: surprise and time–space (Ahmed, Citation2000; Koefoed et al., Citation2016; Merleau-Ponty, Citation1968), which denotes that encounters are both individual instances and informed by general ideas about the Other. They build on, as Koefoed et al. (Citation2016) suggest, ‘other faces, other encounters of facing, other bodies, other spaces and other times’ and as a result ‘they reopen prior histories of encounter and geopolitical imaginations of the Other and incorporate them in the encounters as traces of broader social relationships’ (p. 728). At the same time, they may also result in what Seamon (Citation1979) has named ‘heightened contact’, which refers to the noticing of an object one was unaware of before and grabs one attention because, for instance, of ‘incongruity, surprise, contrast [or] unattractiveness’ which makes ‘the unnoticed world known, without required participation or desire of the notices’ (pp. 108–110). In sum, encounters can pertain to already existing ideas about people and places, but they can also defy them as they trigger surprise or contradict existing ideas of the Other.

It is often when we are on the move in public space that we encounter people and places which partly shape our ideas about social and spatial diversity. Te Brommelstroet, Nikolaeva, Glaser, Nicolaisen, and Chan (Citation2017) argue that: ‘Through daily mobility, we socialize or seek solitude, negotiate our identity and perform a range of social roles; through mobility we may contest power relationships and claim our right to participate in society or may be excluded and ignored’ (p. 3). Accordingly, many studies on the experience of urban diversity are informed by mobile methodologies that offer conceptual tools in understanding the relational qualities of being on the move (see for example, Adey, Citation2017; Cresswell, Citation2006, Citation2010; Sheller & Urry, Citation2006). These methodologies may refer to different perspectives depending on different research questions, but generally they intend to ‘physically or metaphorically follow people/objects/ideas in order to support analysis of the experience/content/doing of, and interconnections between, immobility/mobility/flows and networks’ (Spinney, Citation2015, p. 233). These are arguably better equipped to deal with fleeting, embodied sensory encounters – those encounters that rest on sound, smell and vision, that are here now and gone in a few minutes – that are intrinsically part of city life (Law & Urry, Citation2004) and important for our understanding of the world and our own place in it.

Mobility provides valuable tools to get a sense of place and a sense of (dis-)connectedness with the wider community, and has therefore been used throughout different disciplines (see for review: Pink, Hubbard, O’Niell, & Radley, Citation2010). When wandering through the city, one develops a sense of place through the senses and negotiates their own identity within it. The experience of place is mediated through the human senses which provide the individual with a picture of human and non-human features of the city that can be seen, heard, smelled and tasted (e.g. Matos Wunderlich, Citation2008; Middleton, Citation2010; Van Duppen & Spierings, Citation2013). Through these bodily experiences, one is able to make ‘a kinaesthetic map of one’s city’ (Te Brommelstroet et al., Citation2017, p. 4), which are built on direct sensory experiences but ‘the networks of streets [also] produce and contain memories’, so that ‘at one and the same time, one can travel in time and move through space. Each new angle, each new experience on the streets, could produce another memory- in a flash, the past, the present and the future are combined and recombined’ (Pile, 2002 in Van Duppen & Spierings, Citation2013, p. 235). This is also in line with the argument put forward by Koefoed et al. (Citation2016) that encounters are not only built on surprise but also on time-space.

With regard to sounds in the city (sounds in general, not only the sounds of spoken language), there has been a long history of soundscape studies within geography starting with Murray Shafer’s classical work on the World Soundscape Project focusing on the ways in which humans relate to sound and society and a specific interest in the ways in which industrial growth led to a ‘degradation’ of the auditory environment (Schafer, Citation1993). Despite the growth of soundscape studies in geography and beyond, research has remained focusing on urban noise or sounds as public nuisance, arguably to cater to dominant foci in planning and design practices (see for extended literature review on sound in urban planning and design: Bild, Coler, Pfeffer, & Bertolini, Citation2016). In relation to this paper, it is also necessary to note that, to the best of my knowledge, there has been almost no attention in soundscape studies towards the spoken linguistic diversity in cities and what it means for individual experiences of the city. Language has often been treated as a particular sound in a wider spectrum of urban sounds, categorized as voices, chatter or laughter. Even in a rather novel spectrum of research embedded in the non-representational theories the focus lies in the affective geographies of sounds of the voice (Kanngieser, Citation2012), emphasizing the importance of ‘the acoustic qualities and inflections of voices – the timbres, intonations, accents, rhythms and frequencies’ (p. 339) in the politics of speaking and listening, but not on linguistic diversity as such. Studies that do exist on the relation between languages and soundscapes have mainly investigated how individuals and researchers classify or name the sounds that they refer to in their studies (see for instance: Brown, Kang, & Gjestland, Citation2011; Dubois, Gustavino, & Raimbault, Citation2006; Niessen, Cance, & Dubois, Citation2010), and do not touch upon the issue of individual experiences of linguistic diversity in cities and have barely been informed by geographical scholarship.

Linguistic soundscape of the city: introducing the linguistic sound walks

A rare example of a study focusing on linguistic diversity in the urban soundscape is that from Peake (Citation2012). He has investigated how colonial politics of Gibraltar is manifested ‘through cultural politics of language use, and one means of understanding the negotiation of these cultural politics is through a study of listening’ (p. 171). In his ethnographic study, he deciphers how ‘the sounds of spoken English, Spanish, or Llanito are diagrammatic icons: the sound of spoken language are heard as an acoustic image that acts as a map of a specific ethos and cultural organization of space’ (p. 173). With this, he is particularly interested in the ways in which language is listened to and how this conveys the meanings that are attached to the sounds of language in the organization and characterizations of space. He concludes that

it is the sound of language that shapes the pragmatics that come to shape Gibraltarians’ own speech, action, and experience in and of space, all of which in turn constitute the self that Gibraltarians believe themselves to be. The soundscape through listening, is thus a space where the question ‘’who can we be and still be Gibraltarian?” is politically imagined, re-imagined, and practices through listening and sound. (Peake, Citation2012, p. 187)

Peake’s study (Citation2012) presents an interesting case on the relationship between place, language and identity that may be helpful for researchers interested in the sound of spoken language in cities and the experience of place through this linguistic soundscape. I too am interested in the ways in which language is listened to in public space and how individuals assess spatial and social diversity through the linguistic soundscape. Yet, in contrast to Peake (Citation2012), who used an ethnographic study to investigate how language use, listening and colonial politics in Gibraltar are interrelated, I am particularly interested in the immediate sensory experience of linguistic diversity and the reflection on the ways in which linguistic diversity affects the ways in which individuals assess everyday encounters with social diversity. In order to study this, I have made use of what I have called linguistic sound walks, which are pre-set walks, in this case through the inner-city of Amsterdam. These pre-set walks have been used to capture the immediate sensory experience of linguistic diversity and to discuss and reflect upon the relationship between linguistic diversity and the experience of encounters with spatial and social diversity in Amsterdam. It thus touches on the present and past experiences of linguistic diversity in the city.

These linguistic sound walks involve the participant and researcher being in the midst of multi-sensory stimuli of the surrounding environment (Adams & Guy, Citation2007), instead of being trapped in a ‘blandscape’, such as the University office (Bijsterveld, Citation2010; Edensor, Citation2007). The act of walking may trigger these multi-sensory experiences and as Matos Wunderlich (Citation2008) notes,

As a ‘lifeworld’ practice, walking is an unconscious way of moving through urban space, enabling us to sense our bodies and the features of the environment. With one foot-after-the other, we flow continuously and rhythmically while traversing urban place. […] It is while walking that we sensorially and reflectively interact with the urban environment, firming up our relationship with urban places. Walking practices and ‘senses of (or for) place’ are fundamentally related, the former affecting the latter and vice versa. (p. 125)

Walking in public space results in more intimate ways to engage with the environment that may bring about insightful ideas about both place and self (Solnit, Citation2001). It is suggested that a great advantage of interviewing participants while walking produces important insights into individual experiences, attitudes and knowledge about places (Evans & Jones, Citation2011). A study by Hitchings and Jones (Citation2004) showed that participants often find it easier to speak about their experiences and feelings when they are ‘in place’, resulting in richer data. As opposed to interviews being conducted while seated in a room where participants are more prone to use the ‘correct’ answers, being out in the street can provide the researcher with more informal and interesting interactions with place.

From May 2016 until January 2017, I have conducted thirteen linguistic sound walks with twenty-seven participants through the inner-city of Amsterdam. This city has been chosen because, as many other Western European cities, Amsterdam is a city that may be characterized by a strong and diverse migrant population and a site of super-diversity (see for instance: Crul, Citation2016; Hoekstra, Citation2015; Hoekstra & Pinkster, Citation2019; Kloosterman, Citation2014; Mamadouh & Wageningen, Citation2016). It is therefore a city where many languages can be seen and heard throughout public space, which can be described as a mixture of the majority language Dutch, several migrant languages, foreign languages which are learned at schools and English as ‘the lingua franca in many spheres in life’ (Siemund, Gogolin, Schulz, & Davydova, Citation2013, p. 3), Amsterdam is also an interesting case because it is not typically associated as a site of multilingualism and linguistic tensions as for instance Brussels, Barcelona and Helsinki (see for interesting papers on these cities: Bonfiglioli, Citation2015; Janssens, Citation2007a, Citation2007b, Citation2013; Kraus, Citation2011), yet it is a site where many languages coexist and influence one another. There is no official census of the languages spoken in Amsterdam (and the Netherlands at large) but we know that there are many competing languages found in public space (see Edelman (Citation2010) for a detailed account of the languages used in Amsterdam based on country of birth and origin figures).

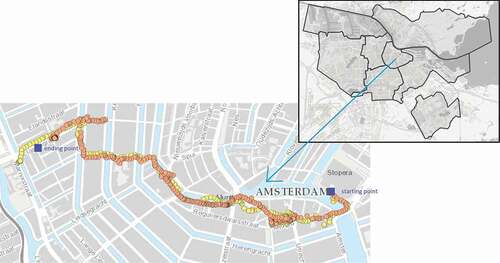

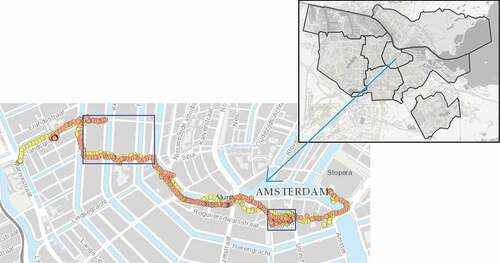

In terms of the linguistic soundscape of Amsterdam, one will likely encounter different languages depending on different districts, neighbourhoods and streets of the city. The linguistic sound walks have therefore been conducted in the inner-city of Amsterdam (see ), from Waterlooplein to Elandsgracht, which is known as a site of rapidly increasing urban tourism (Pinkster & Boterman, Citation2017) and, accordingly has a distinctive character. One will likely encounter languages associated with urban tourism, such as English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Russian. It is important to note that the interest of this paper lies not in whether individuals are able to identify named languages, but how they experience the linguistic soundscape in connection to spatial and social diversity in the city. It therefore touches upon ‘imaginations of languages’, which are informed by perceptions and do not necessarily have to correspond with actual languages heard in public space.

With seventeen participants, the main language of the linguistic sound walk was Dutch (of which ten had a multilingual upbringing), while ten participants opted for English as the main language of the walk (of which only two had English as their heritage languageFootnote1). shows an overview of the participants of the linguistic sound walks.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants linguistic sound walks

The first participants have been drawn to the linguistic sound walk through the use of social media, after which many have introduced new participants to the walks. This snowball method has clearly had an effect on the self-selection of the participants: many have verbalized their interest towards multilingualism beforehand due to for instance their multilingual upbringing or raising a multilingual family themselves, having moved between different countries or due to their professional background in translation. Naturally, the results of this study will therefore be biased, yet it is not my intention to generate generalizable results but to capture individual experiences and elicit subjective responses to linguistic diversity in Amsterdam’s inner-city. Practically, this means that there was a greater chance to find positive narrations on encounters with linguistic diversity than to find examples of discomfort, tension or antagonism. Since this paper consists of an exploration to find possible ways to deal with linguistic soundscapes in the multilingual city, finding a proper method of research is an investigation on its own.

Most of the linguistic sound walks have taken approximately 1.5 hours, the longest with a duration of almost 3 hours, which have been recorded and transcribed. At the starting point of the linguistic sound walk, participants were given a short introduction on the aim of the walk, which was to focus on the linguistic soundscape and to reflect on how it affects the experience of the places visited. They were told that some parts of the walk would take place in silence (in order to listen to the linguistic soundscape) after which a reflection and discussion would follow. In general, I walked with two participants at a time, with myself holding a recording device in the middle. This allowed me to record the discussions properly and to lead the discussion when necessary. Although the first few walks were also tracked with a GPS-device, wanting to assess in situ feelings across the linguistic sound walks at exact locations, this proved to be of little benefit because discussions about the linguistic encounters would not only be about direct instances that change over time but also how they related to past experiences. Participants were able to talk freely on route, corresponding with what Finlay and Bowman (Citation2017) have pointed out ‘the open format put participants at ease and ‘in charge’ (p. 267) and through this ‘adjusting participant-researcher power dynamics’ (p. 263). At the end of the walk I invited participants to have a drink in a local café to reflect to further elaborate on the experience of the linguistic soundscape, place and identity. While the walk enabled the participants to reflect on in situ experiences of linguistic diversity, the reflection afterwards was often mostly related to wider issues around linguistic diversity. During the walk, the participants would for instance point out the languages they heared (at times, also in relation to the linguistic landscapes) and how it made them feel, whilst during the debriefing discussions would evolve around the politics of language (for instance about the increasing role of English in the inner-city of Amsterdam).

The following section will zoom into the results of the linguistic sound walks in Amsterdam. First, it will provide an overview of the discussions about the immediate sensory experience of linguistic diversity in the inner city of Amsterdam, after which it will be connected to more broader thoughts on linguistic, spatial and social diversity.

Immediate sensory experience of linguistic diversity

When walking through the urban environment one is prone to receive multi-sensory stimuli from the surrounding environment, of which sound is an important element. Although historically a shift in balance of the senses has occurred, giving a more prominent role to the visual in research (Jay, Citation1993; Levin, Citation1993; Sennett, Citation1996), many scholars have depicted the inherent relationship between sound of the environment and the ways in which individuals assess their ties with the broader community, with social relationships and with wider concepts of space and place (Bull, Back, & Howes, Citation2015; Feld, Citation2012; Smith, Citation1997). As an important marker for identity, the sound of spoken language gives clues on the nature of the social environment one finds himself or herself in. During the linguistic sound walks through the inner-city of Amsterdam, participants often mentioned the ways in which they relate to sound and the linguistic soundscape in specific, especially after walking in silence. While some participants emphasized being a visual person and often not being aware of the linguistic soundscape of the city in their daily lives, others highlighted that they tend to listen to the languages that they encounter on a daily basis. An example of the latter is a young man with a Bulgarian heritage language who has been living in Amsterdam for two years, while working in Brussels as an interpreter. During the linguistic sound walk he often stressed his deep interest in languages and that while walking in the city he often finds himself listening to languages that he encounters. Especially the languages that he does not recognize trigger his interest, he explained: ‘My partner and I often do this kind of exercise when we walk. Sometimes we both don’t recognize the language that we hear and then we try to guess it. It might sound strange, but we kind of follow the persons that are speaking, just to try to figure out what language they are speaking. It is a fun exercise and I know, a bit silly maybe’.

As scholars have noted, encounters rest on surprise and time–space (Ahmed, Citation2000; Koefoed et al., Citation2016; Merleau-Ponty, Citation1968) which also relates to the experience of this participant. It is the sound of the language that this participant does not recognize that caught his attention, but at the same time, it also builds on time–space in that it builds on prior experiences and the linguistic knowledge of both himself and his partner.

Other participants have claimed that encounters with known languages stick out in public space, especially those tied to heritage languages or languages learnt along the life course. This was often met with different feelings. Sometimes it was met with feelings of comfort and nostalgia, while at other times this could be a source of annoyance and irritation. Many participants noted that hearing a specific language brought them back to another time and another place. For one participant encountering Serbo-Croatian in public space reminded him of the years he spent living in Bosnia. Although this participant has Dutch as his heritage language and as he himself noted ‘looks like a “normal” Dutch young man in his late twenties’ he feels sentimental when he overhears people speaking in Serbo-Croatian and at times even mingles in the conversation to show his bond to the language and the people. This is an embodied experience, which can be seen as ‘a process of reproducing oneself within a constant negotiation between past patterns and present experiences’ (Iscen, Citation2014, p. 125). The body makes sense of the present by using the past experiences (Casey, Citation1987) and the practice of walking enables people to reflect on their personal biography (Lee, Citation2004).

As opposed to this particular participant, there were others that mentioned knowing encountered languages in public space can also be met with feelings of frustration and annoyance, as it implies being forced to listen to the actual conversation, which at times does not interest the hearers per se. When encountering a familiar language, it is harder to ‘switch off’ while this is easier done with languages that are unfamiliar – some respondents even compared the unknown heard language to noise/sound in general. This relates to the process of listening. Botteldooren et al. (Citation2013) note that: ‘listening is a complex process which involves multi-leveled attention and higher cognitive functions, including memory, […], foregrounding (attentive listening) and backgrounding (holistic listening)’ (p. 36). It seems that when a language is known to the listener, it is difficult to switch from foregrounding to backgrounding, while this is easier with unknown languages. The knowledge of the encountered language is therefore important to the immediate sensory experience of the listener and has to be taken into account when assessing the effect of the linguistic diversity on individual experiences of spatial and social diversity.

The linguistic sound walk encourages the participants to listen to linguistic diversity and to be aware of the sound of languages in public space, which might be an unnatural exercise for participants. By listening to the audible environment the listener engages in different ways of listening: ‘from the more holistic listening in readiness waiting for familiar or important sounds to emerge (expected or not), to listening in search expecting particular sounds in a context, or even to narrative or story listening focusing attention on one particular sonic story within the multitude of sounds’(Botteldooren et al., Citation2013, p. 38). Although not representative for the ways in which actual listening to the linguistic diversity in the city may occur in everyday life, the listening process during the walk gives us some insight in the process of listening to languages, as participants comment on the ways in which they make sense of the linguistic soundscape, which tends to be not verbalized in an everyday setting. One participant, a woman in her mid-thirties who has Dutch as her heritage language and an affinity with Mandarin since her partner migrated from China, illustrated how she listens to language in public space as following:

Sometimes you instantly know what language someone is speaking, but often this is hard because of other noises in the city … for instance the tram or loud music. If I don’t know [what someone speaks], I listen to the melody or the tone of the language. Every language is different and sometimes you just hear it through this. Most of the time you just guess.

This participant, and others too, showed that listening to the linguistic soundscape requires skills: first there is the competition with other urban sounds, and then there is the process of recognizing or classifying the encountered language. As for the competition with other sounds, during the linguistic sound walks respondents often noted that it was difficult to detect the language heard because of ‘the background noise’ of other urban sounds, but also because the linguistic encounters were often very fleeting in nature. Although some participants at the start of the linguistic sound walk noted that they felt like ‘spies’, listening to conversations in public space, they later critically noted that this proved to be little because of the fleeting nature encountering language in public space. Most of the respondents noted that listening to people passing by made them only hear snippets of a conversation or merely a few words, making it hard to understand the content of the conversation. For the linguistic sound walks, this meant that the exercise was not seen to be ethically charged, intruding in private conversations amongst passersby’s (as much as there can be privacy in public space of course). While walking in the inner-city, one comes across many individuals but only hears language during the instant of encounter, which may be a matter of seconds. Similar to the participant quoted above, one may guess on the basis of the melody or tone with which language one is dealing with, but often this guessing of the imaginary language is not only done by the sound alone but also on the basis of spatial and social features, such as the location in which the imaginary language is heard and the appearance of the individuals encountered in that location. The individuals encountered on the walk and the environment in which walking takes place inform the perception one has of the linguistic soundscape: this educated guess is based on the languages one expects to encounter in the inner-city of Amsterdam and on the look of the persons and the associated expectations of what language he or she would speak. Individuals do not only create an image of the languages they encounter in public space, but these images can also form a basis on how spatial and social diversity is experienced. The next section of this paper deals with this relationship.

Language and the assessment of spatial and social diversity

Listening to the linguistic soundscape of the city does not happen alone: listening happens in concrete places and individuals use elements from their direct urban surroundings in their assessment of the linguistic diversity. During the linguistic sound walks, it was often stressed how listening to language also builds on seeing clues from the social and spatial environment. Some participants argued that it was hard to distinguish whether listening or seeing comes first and that these sensory perceptions tend to be intrinsically intertwined, without being consciously aware of it. In relation to the social environment, participants noted that it was often on the basis of characteristics of the encountered Other how they experienced the heard language. In this case, the experience of language was also tied to the social diversity in place. The image of the Other gave participants clues on what language they were hearing. One participant, a thirty-two-year-old woman with an Italian heritage language, claimed the following:

I often listen to languages in public space, but it does not stand alone I think. During the silent walk I also used to look at the people that were speaking to guess what they were speaking. I saw some British youth for instance, you can clearly pick them out of the crowd in Amsterdam, they often look like they just smoked a lot and they are loud. But also the way they dress and their hairstyle, it’s obvious. Then I know that I will hear British English when I go pass them, and it happened.

The reverse also happens: sometimes individuals listen to the language and then look at the source of the heard language, which can underline or undermine what they thought to be the encountered language. This shows how encounters with social diversity also have a clear linguistic dimension to them.

Additionally, the spatial context in which the linguistic soundscape is situated is also significant in the experience of linguistic diversity. Before starting off with the linguistic sound walk I asked participants to voice their expectations about the languages that they might encounter during the walk. Almost all participants noted that they thought they would most likely encounter ‘tourist languages’ and English during the walk. This can be the result of dominant discourses about the inner-city, being increasingly the site of urban tourism, but it may also ‘demonstrate(s) that people become familiar with the variety of sounds within the city or neighbourhood based on their individual contexts and make sense of the continually changing acoustic worlds around them’ while ‘the temporal nature of sound provides a connection between the past, present and future, giving self and places a sense of continuity’ (Iscen, Citation2014, pp. 126–127). The perception of this relationship between place and linguistic soundscape was often pointed at when verbalizing the experience of the linguistic soundscape during and after the walk. At times, participants would build on this image of the inner-city to point out that what they heard was in line with what they previously thought about the city being a site of urbantourism. Yet at other times, it seemed that many only voiced their experience when the linguistic soundscape did not meet their expectations. A forty-four-year-old artist claimed the following:

I was surprised to hear so much Dutch during the walk. I always think this is such a touristic place, that Dutch people don’t actually go to the inner-city anymore. Ok, this can of course also be Dutch tourists from other parts of the country you know, but still it does say something about the place doesn’t it?

When asked about what she meant by this, she further elaborated:

Well, sometimes things are not what they seem they are. When we hear about places, we only hear a part of the story. But when we go and explore ourselves, this may be different to what one might expect.

This participant, and others as well, pointed out that sometimes there is a gap between the image of a place and the actual sensory experience of being there. This is part of the nature of urban encounters, which always encompasses the negotiation between surprise and time-space.

Interestingly, the place representations made by the participants did not only encompass an overall image of the inner-city as a whole, they also built on the specific images of micro settings of streets and squares in the inner-city. For instance, during the walk we crossed two well-known sites, Rembrandtplein and a few streets that are part of what is known as ‘De 9 Straatjes’ (‘The 9 Streets’), see , which have a quite distinct character:‘9 picturesque little streets in Amsterdam Canal Belt – Full of quirky shops and wonderful eateries’ (De9Straatjes, Citation2018) and Rembrandtplein being a nightspot, with bars, cafés, eateries and restaurants catering to tourist. Many participants made remarks about the different spatial image of these sights to underline or undermine the actual linguistic soundscape. For Rembrandtplein, it meant that respondents often noted that it was indeed very ‘English’ (referring to the language heard). At times though the multilingual landscape was greater than initially thought, meaning that there was a great variety of languages that they did not expected there (for instance, Arabic and Hindi). De 9 Straatjes was often seen as a place where Dutch dominated the linguistic soundscape, while many imagined it to also be a site of urban tourism and thus they expected it to be more multilingual.

Figure 2. Rembrandtplein (right) and De 9-Straatjes (left) situated on the route of two linguistic sound walks.

Many studies on everyday diversity, common place diversity or everyday multiculturalism stress that living in diversity has become such a normalcy that it tends to go unnoticed. Sennett (Citation2010) for instance pointed out that ‘the encounter with diversity has become so commonplace that is doesn’t much register’ since ‘it lacks disruptive drama’ (p. 269). As opposed to this, the linguistic sound walk has given clues to the opposite idea: the linguistic soundscape can be a potential source of a disruptive effect as it often catches one’s attention and may spark various different experiences in place. It seems that especially when the outcome of urban encounter is surprise, and the linguistic soundscape does not match the actual ideas of place, one is inclined to notice these differences. Hence, the linguistic soundscape can be an important source for ‘disruptive drama’.

Almost all participants were positive about linguistic diversity and celebrated the inner-city as a site of linguistic and social diversity, which might of course be due to the bias of the self-selection of participants. Often it was stressed that one should speak whatever they feel like and linked this to the image of Amsterdam as a tolerant city. This overall attitude of the participants can be seen as an expression of cosmopolitan attitudes, which relates to the openness to difference and diversity (Wang, Citation2018). These attitudes and orientations of cosmopolitanism have informed many of the verbalized experiences of linguistic diversity in the inner-city of Amsterdam, but it was beyond the scope of this paper to assess how these attitudes have been brought about.

Conclusion

In spite of the growing interest of geographical scholars in the experience of everyday encounters with spatial and social diversity in cities, this paper has discussed how linguistic diversity has often been overlooked. Interestingly, many sociolinguists have started to pick up the concept of place in their assessment of linguistic landscapes, while geographers have remained rather silent about linguistic diversity in their study of place. With this paper, I have set out a possible way to incorporate the experience of the linguistic soundscape in the study of social diversity which bridges the gap between geography and sociolinguistics in their quest to understand how language and place come together. Rather than using (structured) interviews, linguistic sound walks allow researchers and participants to be in the context in which linguistic diversity is first-handedly experienced. It opens up ways to reflect on ideas and attitudes about the relationship between language, place and identity while being ‘out in the streets’.

Through fieldwork conducted in the inner-city of Amsterdam, I have shown that in the linguistic soundscape of the city lies an important resource in understanding how individuals assess the super-diverse environment they are situated in. Firstly, the immediate experience of linguistic diversity builds on individual linguistic biographies and is therefore a highly embodied experience. Individuals assess the linguistic soundscape by building on their linguistic skills and prior linguistic experiences. Secondly, the experience of linguistic diversity also rest on ideas about people and places. While walking through the city, individuals assess the sound of language through their perception of the people that they encounter in public space and their perception on the relationship between language and certain places of the city. This may either align or defy their ideas of people and places. Through urban walks, the linguistic soundscape is a source of constantly negotiating the present with past experiences and more broad ideas about places, people and languages.

Although this paper has been preoccupied with finding new ways to incorporate linguistic diversity in the assessment of everyday encounters with spatial and social diversity, it is preliminary and more research has to be done in order to capture the ways in which language, place and identity is experienced. Due to the selection of participants, this study has mainly focused on positive experiences of linguistic diversity, others may for instance investigate examples of discomfort, tension and antagonism when dealing with linguistic diversity in public space or may investigate experiences of linguistic encounters in semi-public and private space – places where ideas about linguistic diversity may be more strict in comparison to public spaces. Additionally, instead of conducting the linguistic sound walks in the inner-city, future research can also be done in the neighbourhood of residency or other parts of the city where urban citizens may feel more ‘at home’ and may therefore be more inclined to retain stricter ideas about languages in place. Also, future research may follow the field of the non-representational and the affective geographies to assess how linguistic diversity is experienced in everyday settings throughout the city. All in all, this paper has proposed and demonstrated a first step to how the study of linguistic soundscapes may complement and broaden our scope in understanding experiences of encounters with spatial and social diversity in public space, on which future research can build upon.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank prof. Avrill Madrell and three anonymous referees for their valuable feedback of this article. Additionally, I want to thank Dr Virginie Mamadouh, Prof. Dr Robert Kloosterman and the members of the GoG research group at the University of Amsterdam for their help, suggestions and criticisms throughout the research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. According to Valdés (Citation2001), the heritage language signifies a language in which an individual is raised in at home, whether or not the individual is able to speak it (at least he/she should be able to understand the language). The individual needs to be to some extent bilingual in that language, even if the proficiency in these languages is not the same.

References

- Adams, M., & Guy, S. (2007). Editorial: Senses and the city. The Senses and Society, 2(2), 133–136.

- Adey, P. (2017). Mobility. Florence: Taylor & Francis.

- Ahmed, S. (2000). Strange encounters: Embodied others in post-coloniality. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis.

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. New York: Doubleday.

- Amin, A. (2008). Collective culture and urban public space. City, 12(1), 5–24.

- Avila-Tapies, R., & Dominiguez-Mujica, J. (2014). Interpreting autobiographies in migration research: Narratives of Japanese returnees from the Canary Islands (Spain): Interpreting autobiographies in migration research. Area, 46(2), 137–145.

- Bajerski, A. (2011). The role of French, German and Spanish journals in scientific communication in international geography. Area, 43(3), 305–313.

- Bijsterveld, K. (2010). Acoustic cocooning: How the car became a place to unwind. The Senses and Society, 5(2), 189–211.

- Bild, E., Coler, M., Pfeffer, K., & Bertolini, L. (2016). Considering sound in planning and designing public spaces: A review of theory and applications and a proposed framework for integrating research and practice. Journal of Planning Literature, 31(4), 419–434.

- Blommaert, J. (2014). Infrastructures of superdiversity: Conviviality and language in an Antwerp neighborhood. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(4), 431–451.

- Bolt, G., & Van Kempen, R. (2013). Introduction special issue: Mixing neighbourhoods: Success or failure? Cities, 35, 391–396.

- Bolt, G. S. (2017). DIVERCITIES, governing urban diversity: Creating social cohesion, social mobility and economic performance in today’s hyper- diversified cities. Impact, 2017, 26–4155.

- Bolt, G. S., Visser, K., & Tersteeg, A. K. (2017). Can diversity in cities create social cohesion? Open Access Government, 15, 240–7612.

- Bonfiglioli, C. (2015). La course de vélo du Gordel autour de Bruxelles-Capitale: Matérialisation d’une frontière communautaire?. National Committee of Geography of Belgium/Société Royale Belge De Géographie, 2, 1–22.

- Botteldooren, D., Andringa, T., Aapuru, I., Brown, L., Dubois, D., Gustavino, C., … Preis, A. (2013). Soundscape for European cities and landscape: Understanding and exchanging. COST TD0804 Final conference: Soundscape of European cities and landscapes 2013(pp. 36–43). Presented at the COST TDO804 Final conference: Soundscape of the European cities and landscapes, Oxford, UK: Soundscape-COST.

- Brown, A., Kang, J., & Gjestland, T. (2011). Towards standardization in soundscape preference assessment. Applied Acoustics, 72(6), 387–392.

- Bull, M., Back, L., & Howes, D. (2015). The auditory culture reader. Oxford: Berg.

- Casey, E. S. (1987). Remembering: A phenomenological study. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Castles, S., & Miller, M. J. (2003). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chríost, D. M. G. (2001). Implementing political agreement in Northern Ireland: Planning issues for Irish language policy. Social & Cultural Geography, 2(3), 297–313.

- Chríost, D. M. G., & Aitchisont, J. (1998). Ethnic identities and language in Northern Ireland. Area, 30(4), 301–309.

- Chríost, D. M. G., & Thomas, H. (2008). Linguistic diversity and the city: Some reflections, and a research agenda. International Planning Studies, 13(1), 1–11.

- Cresswell, T. (1996). In place/out of place: Geography, ideology, and transgression. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Cresswell, T. (2006). On the move: Mobility in the modern western world. London: Routledge.

- Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(1), 17–31.

- Crul, M. (2016). Super- diversity vs. assimilation: How complex diversity in majority– Minority cities challenges the assumptions of assimilation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(1), 54–68.

- De9Straatjes. (2018). Retrieved from https://de9straatjes.nl/nl/home

- Desforges, L., & Jones, R. (2001). Bilingualism and geographical knowledge: A case study of students at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. Social & Cultural Geography, 2(3), 333–346.

- Doughty, K., & Lagerqvist, M. (2016). The ethical potential of sound in public space: Migrant pan flute music and its potential to create moments of conviviality in a ‘ failed’ public square. Emotion, Space and Society, 20, 58–67.

- Drozdzewski, D. (2017). Less- than- fluent’ and culturally connected: Language learning and cultural fluency as research methodology. Area, 50(1), 109–116.

- Dubois, D., Gustavino, C., & Raimbault, M. (2006). A cognitive approach to urban soundscapes: Using verbal data to access everyday life auditory categories. Acta Acustica United with Acustica, 92(6), 865–874.

- Edelman, L. (2010). Linguistic landscapes in the Netherlands: A study of multilingualism in Amsterdam and Friesland. Utrecht: LOT.

- Edensor, T. (2007). Sensing the Ruin. The Senses and Society, 2(2), 217–232.

- Eraydin, A., Tasan-Kok, T., & Vranken, J. (2010). Diversity matters: Immigrant entrepreneurship and contribution of different forms of social integration in economic performance of cities. European Planning Studies, 18(4), 521–543.

- Evans, J., & Jones, P. (2011). The walking interview: Methodology, mobility and place. Applied Geography, 31(2), 849–858.

- Feld, S. (2012). Sound and sentiment: Birds, weeping, poetics, and song in Kaluli expression, with a new introduction by the author. Philadelphia: Duke University Press.

- Fincher, R., Iveson, K., & Leitner, H. (2014). Planning in the multicultural city: Celebrating diversity or reinforcing difference? Progress in Planning, 92, 1–55.

- Finlay, J. M., & Bowman, J. A. (2017). Geographies on the move: A practical and theoretical approach to the mobile interview. The Professional Geographer, 69(2), 263–274.

- Gilroy, P. (2006). Postcolonial melancholia. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hall, S. (2000). The multi-cultural question. In B. Hesse (Ed.), Unsettled multiculturalisms, diasporas, entanglements, disruptions. London, New York: Zed books.

- Hardwick, S. W., & Davis, R. L. (2009). Content-based language instruction: A new window of opportunity in geography education. Journal of Geography, 108, 163–173.

- Helms, G., Lossau, J., & Oslender, U. (2005). Einfach sprachlos but not simply speechless: Language(s), thought and practice in the social sciences. Area, 37(3), 242–250.

- Hitchings, R., & Jones, V. (2004). Living with plants and the exploration of botanical encounter within human geographic research practice. Ethics, Place & Environment, 7(1–2), 3–18.

- Hoekstra, M. S. (2015). Diverse cities and good citizenship: How local governments in the Netherlands recast national integration discourse. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(10), 1–17.

- Hoekstra, M. S., & Pinkster, F. M. (2019). ‘we want to be there for everyone’: imagined spaces of encounter and the politics of place in a super- diverse neighbourhood. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(2), 222–241.

- Iscen, O. E. (2014). In-between soundscapes of Vancouver: The newcomer’s acoustic experience of a city with a sensory repertoire of another place. Organised Sound, 19(2), 125–135.

- Janssens, R. (2007a). De Brusselse taalbarometer. Brussel: VUBPress.

- Janssens, R. (2007b). Van Brussel gesproken: Taalgebruik, taalverschuivingen en taalidentiteit in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest (Taalbarometer II). Brussel: ASP/VUBPRESS/UPA.

- Janssens, R. (2013). Meertaligheid als cement van de stedelijke samenleving. Een analyse van de Brusselse taalsituatie op basis van Taalbarometer, 3.

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (Eds.). (2010). Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space. London/New York: Continuum.

- Jay, M. (1993). Downcast eyes: The denigration of vision in twentieth-century French thought. California: Univ of California Press.

- Kanngieser, A. (2012). A sonic geography of voice: Towards an affective politics. Progress in Human Geography, 36(3), 336–353.

- Kearns, R. A., & Berg, L. D. (2002). Proclaiming place: Towards a geography of place name pronunciation. Social & Cultural Geography, 3(3), 283–302.

- Kielland, I. M. (2016). Strange encounters in place stories. Social & Cultural Geography, 18(1), 1–14.

- Kloosterman, R. C. (2014). Faces of migration: Migrants and the transformation of Amsterdam. London: LSE.

- Knox, D. (2001). Doing the Doric: The institutionalization of regional language and culture in the north- east of Scotland. Social & Cultural Geography, 2(3), 315–331.

- Koefoed, L., Christensen, M. D., & Simonsen, K. (2016). Mobile encounters: Bus 5A as a cross-cultural meeting place. Mobilities, 12(5), 1–14.

- Kraus, P. A. (2011). The multilingual city; the cases of Helsinki and Barcelona. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 1, 25–36.

- Kraus, P. A. (2012). The politics of complex diversity: A European perspective. Ethnicities, 12(1), 3–25.

- Landry, C., & Wood, D. P. (2012). The intercultural city: Planning for diversity advantage. London: Earthscan.

- Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49.

- Lapina, L. (2016). Besides conviviality; paradoxes in being ‘at ease’ with diversity in a Copenhagen district. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 6, 33–41.

- Law, J., & Urry, J. (2004). Enacting the social. Economy and Society, 33(3), 390–410.

- Lee, J. (2004). Culture from the ground: Walking, movement and placemaking, Unpublished paper, Social Anthropologists Conference (March 2004), Durham, UK.

- Levin, D. M. (1993). Modernity and the hegemony of vision. California: Univ of California Press.

- Mamadouh, V., & Wageningen, A. (Eds.). (2016). Urban Europe: Fifty tales of the city Amsterdam, Netherlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Massey, D. B. (2005). For space. California: SAGE.

- Matos Wunderlich, F. (2008). Walking and rhythmicity: Sensing urban space. Journal of Urban Design, 13(1), 125–139.

- Mattissek, A., & Glasze, G. (2014). Discourse analysis in German- language human geography: Integrating theory and method. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(1), 1–13.

- Mcgregor, A. (2005). Negotiating nature: Exploring discourse through small group research. Area, 37(4), 423–432.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible: Followed by working notes. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

- Middleton, J. (2010). Sense and the city: Exploring the embodied geographies of urban walking. Social & Cultural Geography, 11(6), 575–596.

- Morawski, M., & Budke, A. (2017). Language awareness in geography education: An analysis of the potential of bilingual geography education for teaching geography to language learners. European Journal of Geography, 7(5), 61–84.

- Moriarty, M. (2014). Languages in motion: Multilingualism and mobility in the linguistic landscape. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(5), 457–463.

- Niessen, M., Cance, C., & Dubois, D. (2010). Categories for soundscape: Toward a hybrid classification, Inter-Noise and Noise-Con Congress and Conference Proceedings 2010, pp. 5816–5829. Institute of Noise Control Engineering. Lisbon, Portugal.

- Oosterlynck, S., Loopmans, M., Schuermans, N., Vandenabeele, J., & Zemni, S. (2016). Putting flesh to the bone. Looking for solidarity in diversity, here and now. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(5), 764–782.

- Peake, B. (2012). Listening, language, and colonialism on Main Street, Gibraltar. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 9(2), 171–190.

- Pink, S., Hubbard, P., O’Niell, M., & Radley, A. (2010). Walking across disciplines: From ethnography to arts practice. Visual Studies, 25(1), 1–7.

- Pinkster, F. M., & Boterman, W. R. (2017). When the spell is broken: Gentrification, urban tourism and privileged discontent in the Amsterdam canal district. Cultural Geographies, 24(3), 457–472.

- Schafer, R. M. (1993). The soundscape: Our sonic environment and the tuning of the world. Rochester: VT Destiny Books.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge.

- Seamon, D. (1979). A geography of the lifeworld: Movement, rest and encounter. London: Croom Helm.

- Sebba, M. (2010). Discourses in transit. In A. Jaworksi & C. Thurlow (Eds.), Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space (pp.59-76). London/New York: Continuum.

- Segrott, J. (2001). Language, geography and identity: The case of the Welsh in London. Social & Cultural Geography, 2(3), 281–296.

- Sennett, R. (1996). Flesh and stone: The body and the city in Western civilization. New York: Norton.

- Sennett, R. (2010). The public realm. In G. Bridge & S. Watson (Eds.), The Blackwell city reader (pp. 261–272). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A, 38(2), 207–226.

- Shohamy, E. G., Ben- Rafael, E. B., & Barni, M. (2010). Linguistic landscape in the city. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Siemund, P., Gogolin, I., Schulz, M., & Davydova, J. (2013). Multilingualism and language diversity in urban areas: Acquisition, identities, space, education. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Smith, S. J. (1997). Beyond geography’s visible worlds: A cultural politics of music. Progress in Human Geography, 21(4), 502–529.

- Solnit, R. (2001). Wanderlust: A history of walking. London: Verso.

- Spinney, J. (2015). Close encounters? Mobile methods,(post) phenomenology and affect. Cultural Geographies, 22(2), 231–246.

- Tasan-Kok, T., Van Kempen, R., Mike, R., & Bolt, G. (2014). Towards hyper-diversified European cities: A critical literature review. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

- Te Brommelstroet, M., Nikolaeva, A., Glaser, M., Nicolaisen, M. S., & Chan, C. (2017). Travelling together alone and alone together: Mobility and potential exposure to diversity. Applied Mobilities, 2(1), 1–15.

- Tersteeg, A. K., & Bolt, G. S. (2018). Opportunities for social cohesion in diverse and deprived neighbourhoods. Open Access Government, 17, 272–7612.

- Valdés, G. (2001). Heritage language students: Profiles and possibilities. In J. K. Peyton, D. A. Ranard,&, & S. McGinnis (Eds.), Heritage languages in America: Preserving a national resource (pp. 37–77). Washington, DC and McHenry, IL: Center for Applied Linguistics and Delta Systems.

- Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323–337.

- Valentine, G., Sporton, D., & Bang Nielsen, K. (2008). Language use on the move: Sites of encounter, identities and belonging. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 33(3), 376–387.

- Van Duppen, J., & Spierings, B. (2013). Retracing trajectories: The embodied experience of cycling, urban sensescapes and the commute between ‘neighbourhood’ and ‘city’ in Utrecht, NL. Journal of Transport Geography, 30, 234–243.

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super- diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054.

- Vertovec, S. (2010). Towards post‐multiculturalism? Changing communities, conditions and contexts of diversity. International Social Science Journal, 61(199), 83–95.

- Wang, G. B. (2018). Performing everyday cosmopolitanism? Uneven encounters with diversity among first generation new Chinese migrants in New Zealand. Ethnicities, 1–18

- Wise, M. (2006). Defending national linguistic territories in the European single market: Towards more transnational geolinguistic analysis. Area, 38(2), 204–212.

- Ye, J. (2016). The ambivalence of familiarity: Understanding breathable diversity through fleeting encounters in Singapore’s Jurong West. Area, 48(1), 77–83.