ABSTRACT

Costa Rica is well known for its policies to enhance conservation and sustainable use of forests. The country was also instrumental in promoting the mitigation strategy ‘Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+)’ under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The effective and legitimate implementation of REDD+ requires the participation of local stakeholders, including indigenous groups from forest regions, and corresponding provisions were established through social safeguards at the international level. In this article, we review this normative and institutional set-up and link it with experiences from the national and local levels by analysing the development of indigenous groups’ engagement in Costa Rican REDD+ politics. Drawing on a multilevel Political Ecology approach, we analyse data, which were gathered through interviews and participant observation on central government developments and on the Cabagra and Salitre indigenous territories. Our study illustrates the sociopolitical processes related to political agency, land conflicts and lessons learned, e.g. regarding epistemological biases and the local organisation of political participation, which indigenous communities have experienced during the design and consultation of the national REDD+ strategy.

Introduction

Natural resource management related to forests, environmental change and local livelihoods are linked in at least three ways. First, the forests of the world are under severe pressure through land use changes.Footnote1 Major drivers for this are agricultural expansion, commercial and illegal logging, and the conversion of primary forests to plantations, e.g. to grow biofuels and establish mining, infrastructure or pasture for livestock. The resulting deforestation and forest degradation account for approximately 17 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, thereby outnumbering the emissions of the transport sector worldwide.Footnote2 Second, people have to adapt locally to changing livelihood conditions due to global climate change. This is particularly the case for those social groups who depend on direct access to land and natural resources, e.g. forest-dwelling communities, who often overlap with indigenous groups, presumably around 370 million people around the world.Footnote3 The changing climate poses a remarkable challenge for them to secure shelter, food, access to water and cultural spaces. Third, the implementation of mitigation and adaptation policies, e.g. those that aim to stop deforestation and land use change, potentially affects the rights and livelihoods of local people and forest-dwelling communities.

This article will assess the linkages between these different dimensions and associated conflicts by examining experiences from Costa Rica in the design of a forest-based climate change mitigation strategy. We focus on the conditions and effects of indigenous peoples’ participation in the design and early phase of implementing the national strategy on ‘Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation’ (REDD+). Thereby, we strive to enhance our understanding of the sociopolitical processes and conflicts that REDD+ has triggered in Costa Rica, and aim to exemplify the challenges and opportunities, which indigenous communities have experienced in this context.

REDD+ was agreed in 2010 as part of the Cancún Agreements of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and negotiations to improve the mechanism were concluded in 2013 (‘Warsaw Framework on REDD+’). The mechanism reflects the main characteristics of a policy approach that is called ‘Payments for Environmental Services’ (PES), implying that forest-rich developing countries receive financial compensation for slowing, halting or reversing deforestation and forest degradation. Further, REDD+ should encourage countries to invest in low-carbon pathways towards sustainable development. Thus, the overall script for REDD+ has been established at the global level. But, to date, there are still considerable challenges emerging from the vertical interfacesFootnote4 between guidelines and frameworks at different levels.Footnote5 For example, drivers of deforestation are often insufficiently tackled nationally and locally, and domestic bureaucracies regularly face difficulties to co-ordinate effective governance interventions.Footnote6 Successful implementation furthermore depends on the mobilisation of funding, the configuration of favourable horizontal interfacesFootnote7 between different issue areas, such as the alignment with goals in other sectors, e.g. agriculture and energy, and establishing participatory procedures. Indeed, REDD+ negotiations have been strongly shaped by concerns about the potential effects of REDD+/PES on local livelihoods in forest-rich countries. Hence, one crucial part of the UNFCCC deliberations developed around social safeguards to prevent negative impacts on local communities and indigenous peoples, and to ensure the full and effective participation of those stakeholders. In this article, we will assess the prospects of realising corresponding provisions for the case of Costa Rica.

Costa Rica was a driver of the multilateral REDD+ process as the country had placed the topic on the UNFCCC agenda through a joint submission with Papua New Guinea and with the support of other countries, notably from the coalition of Rainforest Nations, in 2005.Footnote8 Since then, Costa Rica has taken numerous steps at the national level to prepare for the implementation of the mechanism, including through initiating information and pre-consultation processes in the forest-rich and indigenous community areas in the Southern part of the country (Talamanca region). Indigenous communities from that region (Salitre and Cabagra territories) have historically experienced land insecurity and inert development due to discrimination, illegal occupation of territories, and the loss of cultural identity and local livelihoods.Footnote9 Analysing the national preparations as well as the engagement of indigenous groups from the Talamanca region in Costa Rica’s REDD+ process, we will shed light on the natural resource governance–conflict nexus that is the focus of this special issue, as it evolves around the national ‘forestland regime’Footnote10 in this Central American country. We ask how the preparation and institutionalisation of REDD+ has taken place and how it has affected political agency, livelihood security and conflict resolution over land tenure of indigenous communities. To answer this question and reveal lessons learned from both the national level and from the Cabagra and Salitre indigenous territories, we embed our analysis within a theoretical framework that brings together Political Ecology and a multilevel perspective on natural resource governance and conflict mitigation. Empirically, we build on interviews with different actors (local and national government representatives, academia, non-governmental organisations, development co-operation and observers) and participatory observation at the central government level and in the indigenous territories in 2017. It is a specific feature of our empirical case that it has not been concluded yet – the national and local REDD+ preparations are still ongoing. Therefore, we will start our analysis by reviewing the REDD+ provisions that have been established internationally and, subsequently, triggered processes of institutionalisation and policy design at national and local levels. This allows us to identify early lessons learned around this topical issue. We proceed as follows: in the next section, we present our theoretical framework. Thereafter, we review the development of REDD+ at the United Nations and examine Costa Rica’s REDD+ history. In the analysis of indigenous peoples’ engagement in national REDD+ politics, we then focus on the challenges, impacts and opportunities that have occurred during the policy information and the pre-consultation process, and give some exemplary insights to related experiences of local indigenous communities of the Cabagra and Salitre territories. In the concluding section, we summarise the practical and theoretical implications of our findings and formulate policy recommendations.

Political Ecology and a multilevel perspective on natural resource governance and conflict

Our analysis benefits from two theoretical approaches to the study of natural resource governance and conflict. First, it is situated in the tradition of Political Ecology that pays specific attention to the relationships between political, social, legal and economic factors, and how they link up with ecological issues.Footnote11 Second, we align this basic premise with a multilevel perspective on natural resource governance and conflict.Footnote12

To start with, scholars from Political Ecology emphasise that costs and benefits of environmental change, including those instances that are related to land use and forest management, are unequally distributed. It is assumed that this distribution affects the social and economic status of agents, and that this, in turn, has implications for political power configurations of a social setting.Footnote13 Ultimately, it is a basic tenet of Political Ecology that environmental conflicts, e.g. around forests, are part of larger social struggles that are structured by class, race and gender. It is through these political processes that the environment is actually produced.Footnote14 Also, the state is not regarded as a coherent or homogenous structure; rather, it is recognised to be made up of diverging interests and entangled political and economic actor constellations that are stabilised in state institutions, and that affect the production of environmental management and transformations.Footnote15 Hence, socio-ecological change is related back to diverging interests and influences of different epistemic perspectives, to the spatial and to the temporal impacts of capitalism and culture(s), modes of production and reconfigurations of sociopolitical assets such as, e.g. the relation between identity-based claims for recognition (as oftentimes raised by indigenous peoples), legal rights (that formally categorise political actors), valorisation of natural resources and land tenure.

Thus, Political Ecology appreciates the political quality of environmental concerns, as they emerge, for example, through the governing of forest areas, in the sense that actor constellations and institutions evolve and continue to exist around conflict lines and struggles over resources. The benefit of this perspective is that it sheds light on the (re-)production of the environment against the background condition of societal dependencies on ecosystem services, as they are brought to the fore through forests as carbon sinks, territories of scenic beauty and reservoirs of different products such as water, wood or food. By investigating the articulations through which eligibilities, e.g. formal rights to participate in natural resource governance, contest decisions and participate in conflict resolution, are determined across scale and between different groups, such a perspective allows us to shed light on the everyday practices that determine access to forestland.Footnote16 Hence, Political Ecology provides for a useful perspective to study the simultaneous constitution of sociopolitical spaces (including those that stretch over geographical boundaries) and the organisation of land use governance in the form of territoriality.Footnote17 Herein, the scarcity of natural resources, be it of atmospheric space related to global carbon emissions or bounded availability of carbon sinks, may be conceptualised as limited resource access or as shrinking space.Footnote18

Those aspects can be aligned with major elements of a multilevel framework on natural resource governance and conflict. As developed in the introduction to this special issue, such a perspective emphasises the connections between national actors (e.g. central government), international actors (e.g. international donors) and global processes (e.g. climate change, global markets, international regulatory mechanisms) and their relation with and impact on local dynamics of governance and conflict.Footnote19 For the local level, three major factors have been considered relevant to explain the character of natural resource management and conflict mitigation as they evolve across scale: actors (type, motivation and capabilities), resource (characteristics and extraction) and conflict (new and existing).Footnote20 However, this article provides for the three following modifications to this set of factors: first, actor constellations are assessed as they relate with institutional structures and normative provisions, thereby constituting the broader architecture of natural resource governance within which agents’ properties and interests are moulded and unfold. Second, we assume that natural resource appropriation does not only take the form of extractivism (at local levels) but may also emerge in the form of conservation policies (green grabbingFootnote21) such as those related to REDD+. Third, our understanding of conflict is not limited to violent incidents but is broader in the sense that it captures the wide range of political and societal confrontations, including contestation, critique and politicisation that inevitably accompany the negotiation, design and implementation of political ecological decisions. Resource governance – where it deviates from the business-as-usual scenario – is thus ultimately a matter of reconfiguring or shifting spaces. Thus, we understand multilevel natural resource governance, including through REDD+, from a Political Ecology perspective to be a case of the vertical and horizontal production of political territoriality in material, institutional and symbolic/ideational terms.

The global REDD+ architecture and the operationalisation of social safeguards

REDD+ negotiations under the UNFCCC

The REDD+ architecture stretches across political levels with the major reference point at global scale being the provisions established under the UNFCCC. The development of the international regulatory mechanism of REDD+ started in 2005, when Costa Rica and Papua New Guinea introduced the item on reducing emissions from deforestation (RED) in developing countries to the UNFCCC negotiations through a joint submission. Over the next few years, the boundaries of the prospective instrument broadened perpetually,Footnote22 and in 2010, parties to the Convention formally recognised activities related to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries (REDD+). The mechanism promises multiple benefits in terms of conservation, mitigation and economic viability as forest-rich countries are financially compensated for not cutting down their forests. Ultimately, these benefits would constitute a public good in the sense that the global climate would be salvaged. However, REDD+ has also been developed based on the premise that the private sector could be involved and that, possibly, emission offset credits could be purchased on global carbon markets. Thus, funding is expected to flow through multilateral public financing or a combination of government and market trading carbon credits. In this sense, the perception and economic construction of resource characteristics (forests) might give way to privatisation and carbon offsetting, a factor that has been considered to affect conflict levels between central governments and local forest governance entities.Footnote23 Overall, the institutionalisation of REDD+ at the international level has raised enormous (short-term) expectations for external funding with predicted financial flows from North to South reaching up to US$ 30 billion a year.Footnote24 Internationally and as of early 2015, more than US$ 9 billion have been pledged for REDD+ activities, although a smaller amount has actually been disbursed.Footnote25 Still, the general outlook also triggers transnational engagement of various interest groups. Thus, it has been reported that the trend has been for business organisations and research centres to negotiate and grant carbon certificates with indigenous groups. In Colombia, these actors have been described as carbon cowboys, freelancers who broker deals with indigenous groups, make investments and sell carbon credits to international markets.Footnote26 Such observations on land grabbing (see also the introduction to this special issue) highlight the necessity to strengthen local capacities of forest governance, secure local tenure rights on land and resources (including customary rights),Footnote27 resettle competing claims to forested land,Footnote28 and shed light on the design and implementation of substantial and procedural safeguards to enable affected groups to make informed decisions on accepting or rejecting REDD+. Thus, the quest for including social safeguards in a global REDD+ framework was motivated by at least three aspects: the historical experiences of indigenous peoples’ marginalisation and the disempowering of local and traditional governance systems; the specific vulnerability of indigenous peoples to the effects of deforestation and forest degradation; and the vulnerability that arises in the context of implementing forest-based policy measures.Footnote29

The REDD+ agreement of 2010, part of the so-called Cancún Agreements,Footnote30 decided on both social and environmental safeguards and on a phase-based approach to national REDD+ implementation.Footnote31 In this, developing country parties should, according to their national capabilities, develop a) a national strategy or action plan; b) a national forest reference emission level (FREL) and/or forest reference level (FRL); c) a robust and transparent national forest-monitoring system for REDD+ activities; and d) a system for providing information on how REDD+ safeguards can prevent negative social and environmental outcomes and how these can be addressed and adhered to.Footnote32 Specifically, indigenous peoples and their rights are considered in the UN REDD+ decision through various normative reiterations. Thus, parties noted, first, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) from 2007 – and thereby implicitly also the validity of Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) through which procedural rights were established regarding mandatory participation of indigenous peoples in those processes or measures that could affect their lives – as well as resolution 10/4 of the United Nations Human Rights Council on human rights and climate change from 2009,

which recognizes that the adverse effects of climate change have a range of direct and indirect implications for the effective enjoyment of human rights and that the effects of climate change will be felt most acutely by those segments of the population that are already vulnerable owing to geography, gender, age, indigenous or minority status and disability.Footnote33

In detail, the social safeguards for REDD+, spelled out in the second paragraph to the Appendix of the Cancún decision, require, amongst others, the

(c) Respect for the knowledge and rights of indigenous peoples and members of local communities, by taking into account relevant international obligations, national circumstances and laws, and noting that the United Nations General Assembly has adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples;

(d) The full and effective participation of relevant stakeholders, in particular, indigenous peoples and local communities.

These two provisions are crucial in determining the development of preparatory and consultation processes with local actors, including indigenous peoples. Furthermore, safeguard (e) includes a footnote that sets out the mandate for

Taking into account the need for sustainable livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local communities and their interdependence on forests in most countries, reflected in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as the International Mother Earth Day.Footnote34

However, various caveats to these provisions apply: first, the safeguards are not part of the operational text of the Cancún Agreements but are relegated to the Annex. Second, UNDRIP is merely noted, which is rather weak language in international law, and is qualified with reference to its conditionality upon national circumstances and laws. At this point, they were neither legally binding for partiesFootnote35 nor operational, but parties were requested to promote and support the safeguards, and develop an information system (including monitoring, reporting, and verification; MRV) to track their implementation. Hence, the main responsibility for implementing and follow-up measures was relegated to nation states.

The following Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting in Durban in 2011 ended with a decision that explicitly linked social and environmental safeguards with the issue of finance. It clearly reiterated the Cancún outcome and the necessity to respect and address the safeguards, regardless of the type or source of financing (Draft Decision UNFCCC -/CP.17, COP17). Still, observers noted that clear rules on reporting and measuring REDD+ impacts were lacking and that, therefore, the safeguards for this type of land use governance were ultimately watered down.Footnote36 But guidance on reference levels and/or reference emission levels provided the basis for a MRV scheme to be established in conjunction with methodological advances. A milestone in developing the script of REDD+ was then COP19 in Warsaw in 2013, when parties adopted a comprehensive framework (rule book) including guidance for full implementation of REDD+. It clarified, inter alia, requirements for technical analysis and that MRV for REDD+ should be consistent with any guidance for the MRV of nationally appropriate mitigation actions (NAMAs) (Decision 14/CP.19). It also established a Safeguards Information System (SIS) (Decision 12/CP.19), thereby linking REDD+ activities to results-based finance. Thus, information on compliance with safeguards should be included in national communications to the UNFCCC; however, there was no specification regarding compliance requirements and possible legal consequences from failure to comply with the safeguards.Footnote37

The complexity of meaning, institutions and standards around REDD+ safeguards

Despite this increased formal recognition of safeguards over time, analysts have repeatedly noted that the actual content of the term has, in fact, not been discussed profoundly in the negotiations.Footnote38 Indeed, the international community agrees that safeguards encompass a broad set of principles that should be promoted and supported. Yet, different ideas, objectives and understandings embedded in the term – including the implications of the word rights – might be carried along through the different phases of REDD+ preparation and implementation on the ground. Hence, whereas on the one hand, a certain standardisation of normative expectations associated with the mechanism can be observed, on the other hand, there is still ambiguity and ample room for national/local level interpretation and linkage with existing domestic provisions. Furthermore, the Warsaw Framework has been considered to promote centralisation of land use management at the national level by linking MRV processes to reporting obligations under the Convention, and by providing the opportunity to create a voluntary national entity or focal point for REDD+.Footnote39 Indeed, critical assessments have noted that REDD+ may not only serve to secure the dominance of market-based solutions of international climate governance, but also as a governmental strategy to (re-)establish organisational arrangements of national control over indigenous territories.Footnote40 Thus, the dominant discourses may support the negative stigmatisation of local forest-dwellers (and not problematise large international corporations that engage in land use changes)Footnote41 or also draw up new frontiers between those who have been equipped with rights at the international level (indigenous peoples through UNDRIP) versus those who have not (local communities). Hence, it seems justified to pay due attention to domestic developments of forestland governance, including articulations of the meaning that is attributed to the safeguards, to dynamics in actor constellations, effects of contestation, politicisation of land use and political subjectivity at local and central levels, that follow from the policy design at the global level. But, in fact, the UNFCCC is not the only relevant institution in this regard.

Alongside the UNFCCC negotiations, a broader transnational institutional complex on REDD+ has evolved. Since 2008 – even two years before the adoption of the Cancún Agreements – inter- and transnational actors had started to develop support structures for national REDD+ strategies, e.g. the UN-REDD Programme, a joint programme of the UN Environment Programme and the UN Development Programme. Other spaces include the REDD+ Partnership, which was established in 2010 to scale up actions and finance for REDD+ initiatives, and the World Bank Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). These institutions all trigger the development of nation states’ capabilities in material (financial support) and immaterial (knowledge and networks) ways. For example, an integral part of the FCPF is the Carbon Fund and its Emission Reduction Programme, through which pilot incentive payments are disbursed for REDD+ policies and measures in those developing countries that have progressed on readiness activities.Footnote42

The different international institutions also foster standardised safeguard frameworks, including the Strategic Environment and Social Assessment (SESA) and the subsequent Environmental and Social Management Framework of the World Bank and its FCPF, the Country Safeguards Approach Tool, Social and Environmental Principles and Criteria of UN-REDD, the REDD+ Social and Environmental Standards, or the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Standards. These standards differ with view to their tailoring towards the SIS, diverging specifications regarding fundamental issues, such as FPIC, and regarding the targeted unit of action. Thus, the FCPF has not elaborated specific standards for REDD+ readiness activities but instead calls on the promotion and support of UNFCCC REDD+ safeguards through World Bank’s general Operational Policies and Procedures.Footnote43 However, these policies and procedures are partly inconsistent with the UNFCCC provisions,Footnote44 as they, for example, render compliance with FPIC dependent on a partner country’s ratification of Convention No. 169 of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) of 1989, or existing national legislation, requiring countries to ‘consult’ with indigenous peoples instead of seeking their ‘consent’.Footnote45 Instead, UN-REDD treats FPIC as a means for indigenous peoples to be not only involved in processes that affect them, but also to determine the outcome of decision-making of those matters.Footnote46 Despite those diverging requirements and ‘in the absence of more detailed guidance by the UNFCCC COP’, the standards of UN-REDD and the FCPF ‘have become the principal source to interpret REDD+ safeguards’.Footnote47 Still, this fragmentation of normative provisionsFootnote48 leaves considerable room for countries implementing REDD+ to interpret the safeguards and design readiness activities. On this note, we now turn to analysing the global-to-local travel of REDD+ social safeguard provisions in Costa Rica.

The national level: REDD+ and indigenous peoples in Costa Rica

A short history of national forest policies and payments for environmental services

Forest cover in Costa Rica has undergone dramatic changes over the past decades. Although the national constitution states that each person has the right to a ‘healthy and ecologically balanced environment’,Footnote49 Costa Rica experienced high forest cover loss and one of the fastest deforestation rates in Latin America in the 1980s,Footnote50 mainly due to conversion of land into agricultural areas and pasture. Today, almost half of the national territory is again covered with forest. In contrast, regulation in other issue areas, such as water or waste management, or the reduction of pesticides and other chemicals in agricultural production lag behind.Footnote51 Hence, we can observe a selective production of sustainability and of environmental goods through specific natural resource governance measures.

Those measures started to be implemented between 1985 and 1998, when Sustainable Forest Management standards for tropical forest and plantation forestry were promoted in Costa Rica. To date, these can, however, not be included in the country’s FREL/FRL reporting due to lack of (electronically available) data on management plans.Footnote52 In the mid-1990s, another policy instrument was introduced as a complementary approach to the existing Protected Area System that dates back to the 1950s and which mostly comprised of state-owned forests. The PES Programme (Pagos por servicios ambientales; PSA) was introduced as a compensation measure for private forests through provisions in the Forest Law of 1996 (entered into force in 1997).Footnote53 It is managed by the National Fund for Forestry Financing (Fondo Nacional de Financiamento Forestal; FONAFIFO) of the Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE) and is financed mostly through taxes on fossil fuels. The Forest Law furthermore banned forest conversion so that deforestation became de facto illegal. The national PES system facilitated the linkage of conservation and management of forest resources to socio-economic development. It allowed forest owners to receive payments for protecting their forests, for growing new forests and to manage standing forests for timber and non-timber products.Footnote54 To date, approximately 20 per cent of Costa Rica’s territory, one million hectares, have received funding through PES.Footnote55 Out of this, approximately 4.5 per cent have been allocated to indigenous territories for which PES is the major source of income.Footnote56 The national system of protected areas and the national PES programme jointly cover 35 per cent of the country and 70 per cent of the forests.Footnote57 In sum, the shift in Costa Rica’s forestland governance has been supported by forest conservation policies,Footnote58 the willingness of private land owners to contribute to a public goodFootnote59 and the introduction of financial incentives, also including income tax breaks, cash bonds for conservation and subsidised credits. But, the national demand for PES funding exceeds the available sources.Footnote60

The set-up of REDD+ in Costa Rica

Thus, the national interest in promoting the RED(D+) idea at the international level has also been triggered by the fact that it is set out to be the main financing option for the domestic PES programme.Footnote61 In a way, REDD+ provides the outlook for further financial gains in an already strongly institutionalised domestic setting of forestland governance. In 2008, Costa Rica was selected to receive funding from the FCPF and, one year later, received a US$ 200,000 readiness grant to prepare its Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP). In 2014, Costa Rica became a partner country of UN-REDD.Footnote62 Hence, the country is basically subjected to following safeguard standards of both international institutions.

The R-PP initially outlined 10 strategic actions and was approved in July 2010, which discharged a further grant of US$ 3.4 million, later increased to US$ 3.6 million with the addition of US$ 200,000 to develop a grievance redress mechanism.Footnote63 Between 2010 and 2014, the strategic options were revised to readjust the National REDD+ Strategy and its implementation plan. Costa Rica currently engages in further preparatory and implementation activities such as the submission of its proposed national FREL/FRL,Footnote64 and the submission of the national Emission Reductions Programme Document as part of the implementation of the REDD+ strategy. The programme emphasises the prohibition of land use change and the strengthening of both the Protected Area System and PES as policy instruments for forest conservation and carbon stock enhancement through reforestation, tree plantations and the establishment of agroforestry systems.Footnote65 Those activities have been considered voluntary and exclusively to obtain results-based payments for REDD+ actions.Footnote66

Owing to its expertise in PES and in managing World Bank projects, FONAFIFO was selected as the responsible government agency for executing the REDD+ readiness phase.Footnote67 This clearly reflects the path dependency that had been created through the PES legacy of Costa Rica. FONAFIFO has an independent legal status and a mixed composition that encompasses representatives from the public sector, MINAE, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG), the National Banking System, and two representatives from the private sector appointed by the National Forestry Office. In REDD+, the agency is both responsible for the development of the national strategy and hosts the REDD+ Secretariat, an internal arrangement through which the technical work for REDD+ preparation is directed. However, FONAFIFO’s institutional capacity in terms of work force that is reserved for REDD+ is limited and must be regularly supported by consultants to generate information and prepare the required documents to be submitted to the FCPF.

As the elaboration of the REDD+ Strategy requires the participation and engagement of all relevant stakeholders including indigenous peoples, in May 2011, a SESA workshop was implemented to assess the potential impacts from national REDD+ activities and policies. This workshop was in itself not a part of the official consultation process but one of basic initial activities that was used to identify possible social and environmental risks. It also helped to prioritise potential REDD+ activities and facilitated the identification of institutional and capacity gaps. This event constituted the first time that stakeholders were brought together to consult and discuss social and environmental concerns. At that occasion, it was clarified that participation and consultation on REDD+ had to be developed jointly with the indigenous territories, and that Indigenous Associations of Integrated Development (Asociaciones de Desarrollo Integral Indígena; ADIIs) must be engaged. The ADIIs are the local government structures in indigenous territories, comprising different communities, and were established by the Community Development Law in 1967. The Indigenous Law of Costa Rica of 1977 recognised these associations as decision-making entities regarding development and natural resource governance within their territories. But many ADIIs face challenges, such as regarding their representativity, as compared to other traditional structures, e.g. community boards of the elderly. Furthermore, the steering board of each ADII changes every two years, which poses a challenge in terms of institutional memory, individual capacities (e.g. knowledge of the process and technical details related to REDD+) and continuous working relations with state agencies and external actors, such as development organisations.Footnote68 As a result, a large amount of time is usually spent to re-train and inform new people who join the process. This takes away resources that could otherwise be used to transfer information between local and national levels in a faster and more efficient way. Still, for governmental agencies, the ADIIs remain the official counterpart, e.g. when issuing invitations for stakeholder consultation and workshops, because ‘there is the law, and you cannot ignore the law’.Footnote69

Throughout the process, further institutions have been introduced, such as the National System of Conservation Areas (Sistema Nacional de Areas de Conservación; SINAC), an agency of MINAE. In 2012, an additional institutional interface was created by MINAE that established an Executive Committee for REDD+ to serve as an interinstitutional platform to which one representative from each of the stakeholder groups that may be affected by REDD+ is appointed: indigenous territories, industrial timber, small forest producers, MAG, MINAE, the National Banking System and civil society or owners of degraded lands. The Executive Committee meets monthly, and also has regular meetings with FONAFIFO. Its coordinative functions include: (1) to issue policy recommendations for REDD+; (2) to facilitate conflict resolution during the preparation of the National REDD + Strategy; (3) to ensure the participation of key stakeholders; (4) to promote the exchange of information coherent and transparent amongst the relevant stakeholders; (5) to approve technical studies; (6) to systematise the consultation processes; and (7) to guarantee the application of FPIC in the consultation processes in indigenous territories. These provisions should ensure that the interests of each relevant stakeholder were represented and they were able to voice their concerns during the design of the National REDD+ Strategy.

Overall, we can thus observe a complex architecture of different types of actors, including state, non-state and international stakeholders. But, there are also challenges that evolve from this institutional complexity. For example, the mandates of the domestic institutions do not always correspond to the problem at hand and the different actors continue to follow their partial vision of the issue. In this sense, the capabilities (e.g. formal decision-making authority) of involved actors at the national level do not necessarily match with the requirements of effective natural resource management. This becomes evident when looking at the issue of ‘drivers of deforestation’, for which there exists a discrepancy in terms of origin of the problem versus the institutional mandate and competencies to handle it. For example, wildfires are a major cause of forest degradation in Costa Rica and arise mostly in the context of agriculture. Yet, the responsibility to deal with wildfires does not rest with MAG but with SINAC. Also, the resolution of land tenure issues is not dealt with by national REDD+ institutions, such as the Executive Committee.Footnote70

Despite those blind spots, there is a strong legacy of the national REDD+ process in Costa Rica. This shows, for example, in the fact that it has ‘survived’ three governments as of early 2018, ‘because it has been really hard work and it has the sectors involved so they have the pressure […] and we have raised all this awareness and we have a huge, huge participatory work’.Footnote71 This also relates to the engagement of indigenous peoples in the process.

Indigenous peoples in Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, there are 24 legally recognised indigenous territories belonging to eight ethnic groups, the Cabécar, Bribri, Brunca or Boruca, Guaymí or Ngäbe, Huetar (Guatuso or Maleku), Térraba or Teribe and Chorotega. Indigenous peoples comprise approximately 2.4 per cent of the national population,Footnote72 and often live in poor economic conditions with limited access to education, health services, water and sanitation.Footnote73 Also, not all communities use Spanish as their daily language so that different levels of accessibility and equal participation in relation with the government exist.Footnote74 The Indigenous Law of 1977 states that indigenous territories are ‘inalienable and imprescriptible, non-transferable and exclusive for the indigenous communities’.Footnote75 The territories can be regarded as part of the spatial organisation of political agency as there are three different types of official land titles that exist in Costa Rica: private, public and collective (indigenous). The (customary) land rights of indigenous communities are executed by the ADIIs, and funds from the PES programme are channelled through the ADIIs. Then, the ADIIs decide internally about how these benefits are distributed.Footnote76 Although there have been successful cases where use of resources has been well planned and/or evenly distributed, interviewees have indicated that in many territories these funds have created tension because some groups have appropriated and managed them very subjectively, showing favour to families closest to them.

The illegal occupation of indigenous territories is also a major issue in Costa Rica even though it is prohibited by law for non-indigenous people to buy land in indigenous territories. The political and legal contestation of this situation through indigenous peoples has repeatedly led to violent and fatal attacks, including in the Salitre indigenous territory.Footnote77 In the attempt to re-organise land distribution, non-indigenous land owners, who bought their property before 1977 (Indigenous Law), should be financially compensated by the government for returning their titles. Yet, estimates suggestFootnote78 that up to 98 per cent of indigenous peoples’ territories are still illegally occupied by non-indigenous people. It is only in two of the 24 indigenous territories that indigenous peoples possess 100 per cent of their titled lands. In five territories (20.75 per cent), they possess between 75 and 90 per cent. In four (16.66 per cent), they possess between 58 and 60 per cent; and in six territories (25 per cent), they de facto possess between 32 and 50 per cent. In the remaining seven territories (29.16 per cent), indigenous peoples possess less than one-quarter of their titled lands, out of which three with less than 10 per cent. Hence, it can be concluded that indigenous peoples in Costa Rica, generally speaking, face tremendous resource scarcity in the sense of restricted access to (their) lands. Relatedly, the relation between the central government and indigenous peoples has historically been critical or at least ambiguous. Insistently, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has thus criticised persistent human rights violations against indigenous peoples, particularly ‘the State’s wilful disregard for this situation and its consequences’.Footnote79 Furthermore, the resolution of land-related conflicts, the restitution of illegally occupied territories and associated compensation are aggravated by the various factors that, in fact, precede the come into being of REDD+. These factors include the incomprehensive consultation of affected people(s) through governmental agencies, interest frictions within the indigenous community itself, including due to mixed family composition of different communities and/or with non-indigenous peoples, path dependencies related to territorial planning (limited availability of alternative land for resettlement of illegal settler families), the lack of transparency and capacity in the ADIIs, and supposed criminalisation of rights activists.Footnote80

Hence, a situation of social injustice, power asymmetry and unequal access to land has been a major condition under which national REDD+ developed. The given fact of insecure and unclear land tenure challenges the effective and legitimate implementation of the mechanism.Footnote81 Given its potential financial volume that makes investments in forest areas highly attractive for external investors, it could be expected that the prospect to start putting REDD+ into practice on the ground might increase the pressure on indigenous territories even more.Footnote82 Hence, the thorough consideration of substantial voice and implementation of procedural rights – as supported by the global SIS approach – are crucial elements of a sustainable and fair REDD+. Then again, the international norms that have been linked to REDD+ might also function as an entry point to challenge and contest ignorance towards human rights violations associated with forestland governance.

Indigenous engagement in domestic REDD+ action

Generally speaking, and as elaborated above, deforestation and forest degradation pressure traditional norms and practices of forest-dwelling communities. For this reason, it has been a main interest for indigenous peoples and non-indigenous rights advocates in Costa Rica to propose a vision to REDD+ that would emphasise their cosmogonic and cultural perspectives.Footnote83 As our semi-structured interviews with experts from the REDD+ Secretariat, the Executive Committee, indigenous community leaders and indigenous local organisations revealed, the international REDD+ process has equipped indigenous peoples in Costa Rica with more recognition and information about the national forestland situation. Their participation was not least driven by the influence of the World Bank, including its SESA policies, and the requirements of ILO No. 169.Footnote84 The strong role of the World Bank, which had been institutionalised at the global level, e.g. through the FCPF, thus, and despite the ambiguity of the aforementioned global framework, made a difference as compared to, for example, the design of the national PES system in the mid-1990s, when indigenous peoples had not been consulted.Footnote85

Costa Rica started an early dialogue on RED(D+) with representatives of each of the ADIIs of the 24 indigenous territories in 2008. The SESA workshop of May 2011 then included indigenous representatives from all 24 indigenous territories.Footnote86 On that occasion, indigenous groups criticised that their perspectives were not (adequately) reflected in draft documents related to the prospective National REDD+ Strategy. As a consequence, a preliminary consultation plan was drafted with all indigenous territories in 2012. The plan was approved by 19 indigenous territories. Subsequently, five priority issues were identified to address possible risks associated with the National REDD+ Strategy from the indigenous peoples’ perspective, namely: (1) land tenure; (2) PES adapted for indigenous territories; (3) the concept of forest based on the cosmogonic/cultural view; (4) implications of protected areas and indigenous territories; and (5) participatory evaluation and monitoring. A unique aspect of the REDD+ readiness process in Costa Rica has thus been that the consultation plan was proposed by the country’s indigenous peoples themselves and that they coordinated joint positions for the 19 territories that supported the consultation plan as well as for the five territories that did not support it.

The five indigenous territories, which would not support this outcome, are in the Southern Pacific region of the country and had previously resigned from the collective process to start a high-level dialogue directly with the government.Footnote87 They wanted to address all existing concerns between the region and the central state in one negotiation process. This also related to an additional type of land use conflict, the government plan to build the Diquís hydroelectric project.Footnote88 Hence, these communities from the Southern territorial blocks strategically utilised the new vertical institutional set-up that had been created through the REDD+ process to effectively expand on their (discursive) power base and broaden the scope of articulations on socio-ecological matters. Thus, the political agenda has been expanded horizontally to include not only further livelihood matters, e.g. water and education, but also renewable energy politics. REDD+ had provided them with a window of opportunity to politicise additional items outside the REDD+ box and challenge expected negative externalities from resource infrastructure projects. In symbolic terms as well as in terms of reconfiguring power assets in the domestic context, the REDD+ process had thus become charged with much more than forest-based mitigation.

The REDD+ consultation plan that was agreed by the 19 territories served as a guideline to implement further participation of indigenous peoples in three main phases: (1) information; (2) pre-consultation; and (3) consultation. Thereby, the process would adhere to the formal requirements of ILO No. 169 – even though, in practice, the first two phases would de facto take place at the same time.Footnote89

Phase 1. Information stage

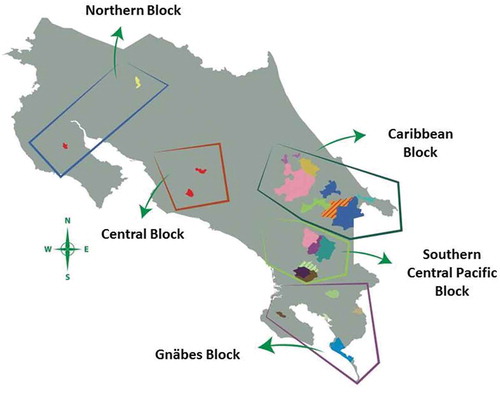

Indigenous peoples recognised the importance of understanding the concept of REDD+ from their own perspective to promote participation and political incidence at local, regional and national levels. To realise the indigenous consultation plan, indigenous peoples formalised an organisational structure to initiate the consultation process in their territories. According to the plan, the indigenous territories were defined into four territorial blocks. Each territorial block included indigenous territories that shared geographical location, cultural characteristics and cosmogonic view ( shows the location and grouping of indigenous peoples for the REDD+ process by territorial blocks). Each indigenous territory within each territorial block elaborated its own consultation plan taking into consideration institutional and traditional government structures, local organisations, culture and cosmogonic views, and national and international legislation. The consultation plan facilitated an inclusive and participatory process of the National REDD+ Strategy considering government and traditional/local organisations and promoted the participation of women and the elderly.

Figure 1. Indigenous peoples for the REDD+ process by territorial blocks.

Source: MINAE, Emission Reductions Programme to the FCPF Carbon Fund, 51.

In 2014, a National Programme of Cultural Mediation was established with the support of multilateral and bilateral agencies (the REDD/CCAD-GIZ Programme) in order to socialise, conceptualise and systematise for the pre-consultation and consultation phases of the National REDD+ Strategy. A pool of cultural indigenous mediators from each of the 19 territories were trained to make the developments associated with climate change more accessible for members of the indigenous communities, including by resorting to their own languages instead of Spanish. Initially, 121 people from the 19 indigenous territories, representative of different social groups, e.g. young men, women and the elderly, were trained to start this information stage. Subsequently, in 2016 and 2017, the other five territories of the Southern Pacific block (Boruca, Rey Curré, Cabagra, Salitre and Térraba) were integrated into this process. The mediators promoted the translation of opportunities and risks and facilitated a dialogue on REDD+ across the different levels.Footnote90 For example, they were able to establish from the local context the traditional integrated perspective regarding the environment and human relation with nature. Environmental changes and the degradation of forestlands were thus perceived the following way: ‘[w]e are taking more from the forests than we need and for that reason Mother nature is bleeding. Mother nature gives human life so when we don’t take good care of her, we die with her’Footnote91 (see also section on local-level developments below). These understandings and values were then transmitted to the national level, and influenced the development of different chapters of the National REDD+ Strategy.

Phase 2. Pre-consultation stage

Once the training process was completed, the pre-consultation phase in the territories began. It was based on the implementation of workshops, facilitated through FONAFIFO, in each territory to initiate an analytical discussion on the strategic activities and the five special topics that had previously been identified (see above). These special topics were discussed with the communities, and they themselves reviewed and compiled reports as they were hired as consultants by the government. At the end, these reports were compiled into one final document at the central level as part of a systematisation of responses. This form of participatory pre-consultation has been regarded to be both an instance of capacity development as well as of recognition, as the communities experienced that their ‘work actually matters. […] So it created some sense of responsibility and commitment’.Footnote92 Our interviewees suggested that two main lessons were taken from this stage, indicative of the entanglement of political structuration and ontological plurality regarding human-nature relations that need to be handled in natural resources governance: first, the communities were challenged with the initial form of how the workshops were organised. Different events on the different issues would be conducted with different governmental agencies. But, it was ‘kind of hard for them to have conversations on the same topics. For them it is all government. […] We did not think that they would prefer to have one [counterpart]’. Second, the reports revealed the complexity and variance of indigenous cosmologies. For example, different variants exist of Sibö (God) and the central authorities were faced with the question of how to reflect this diversity in the national strategy – which, ultimately, would have to prioritise action and specify objectives and measures.

The information compiled during the pre-consultation phase was then put together in a specific chapter of the National REDD+ Strategy (‘Participation of Indigenous Peoples’). Overall, the strategy is made up of policies, actions and measures that focus on:

Promotion of productive systems with low carbon emissions. Promote the increase of tree cover in productive systems (livestock and agricultural crops) and ensure that these activities do not contribute to deforestation.

Strengthen programmes for the prevention and control of land use change and fires. Implement activities that can contribute to avoid deforestation and forest degradation through the implementation of fire control and prevention programmes.

Incentives for the conservation and sustainable management of forests. Influence the conservation of existing forests through the promotion and sustainable management of forests, and avoid deforestation through incentives (such as PES schemes) and adequate regulation of forests that are present on private lands.

Restoration of forests and landscapes. Increase the number of trees in a deforested area through commercial reforestation and restoration of degraded watersheds.

Participation of indigenous peoples. Achieve active participation of indigenous peoples to consider the five special topics that were identified by indigenous peoples as relevant to prevent deforestation and forest degradation in their territories.

Enabling conditions. Implement REDD+ and improving financial monitoring, participatory and organisation conditions for the relevant stakeholders.

Phase 3. Final consultation stage

After this systematisation, in July 2017, a national workshop was implemented to define the methodological approach of the consultation process in each of the indigenous territories. The final stage of the consultation process will be carried out by each ADII based on its own consultation plan and critical avenues for implementing the indigenous chapter (rutas críticas).

In sum, the complex REDD+ architecture involves international norms, multilateral donors, national bureaucracies and local governance structures and has evolved against the background of national path dependencies regarding policy design and politics. The nation-level experiences reveal the complex process to engage indigenous groups in a formal consultation process to apply FPIC and take into consideration the social safeguards established at the international level. Yet, the preparation and institutionalisation of REDD+ at the national level has triggered broader political developments on indigenous participation beyond the boundaries of the issue itself. One derivative domestic development stands out in this regard: in 2016, the central government through the Casa Presidencial, initiated a process to develop a Protocol to guide indigenous consultation processes (Mecanismo General de Consulta a Pueblos Indígenas). The design of this document would be based on an assemblage of experiences from different institutions, e.g. FONAFIFO and SINAC. It should serve as a guideline for future consultation processes in indigenous territories regarding other government projects or initiatives (e.g. infrastructure development, education, health, energy). At the same time, however, an interviewee from academia pointed out that the domestic human rights discourse related to indigenous communities was generally perceived rather narrowly by state agencies. Thus, it was mostly limited to the issue of prior consultation, thereby ‘simplifying’ the political struggle and relegating it to the conflict resolution mechanisms of the judiciary, e.g. the Constitutional Tribunal of Costa Rica. Whilst this was a useful mechanism to hold state agencies accountable and put a hold on human rights infringements that would arise for example through large-scale and state-led infrastructure projects such as Diquís, it also came along with a considerable blind spot. For what was oftentimes left aside in such handling were questions of development and addressing broader socio-economic, cultural and political demands of indigenous peoples.Footnote93 Thus, we conclude that there remain substantial limits as regards the effects of REDD+ (as of now) to overcome social stratifications or the classed and raced struggles that might surface as environmental conflicts in Costa Rica.

The local level: experiences with REDD+ from the Cabagra and Salitre territories

The Cabagra and Salitre indigenous territories

Cabagra and Salitre are Bribri territories that joined the REDD+ preparatory process in 2017. Both territories are located on the Pacific side of the Talamanca mountain range. Cabagra is the third largest Bribri territory in the country with an extension of 27,860 hectares. It has a population of 3,188 people that are distributed in 22 communities. Around 25.9 per cent of the territory is under non-indigenous hands.Footnote94 Salitre is located next to the Cabagra territory and stretches over 11,700 hectares with a population of 1,285. Here, 15 per cent of the territory is under non-indigenous hands.Footnote95

According to oral histories, it is estimated that some 200 years ago the cultural territory had an area of more than one million hectares that stretched all the way to Panama.Footnote96 The Bribri cosmogonic view purports that the Bribri people germinated from corn seeds that Sibö threw on the Namasol Mountain in the Talamanca region. Thus, the traditions reflect a strong bond, identification and feeling of belonging to the land and nature. The Bribri believe that each living being has a spiritual owner called Dualok and that Sibö gave the Bribri a specific task on the Earth to protect natural world and ensure that their own cultural norms are fulfiled and respected. Thus, it is the Bribris’ duty to take care of the Dualok and hunt or use only what is essentially needed. Today, the following traditional land uses are present:Footnote97 territory as living space; agricultural production; collective use, e.g. extraction of food, construction materials, and medicines, amongst others; sacred or spiritual practices in forests, streams, rivers and thermal waters. The ritual sites are usually located in the high parts of the mountains and are the places that remain largely untouched and may only be entered by spiritual guides. By the Indigenous Law, the ADIIs are the legal and political representative, including during conflict resolution, of the communities. Thus, they have been engaged in the development of the National REDD+ Strategy. However, ongoing land conflicts (see above) had prevented the Cabagra and Salitre territories from participating in the original training (information and pre-consultation) that had been organised by FONAFIFO with financial support from the World Bank.Footnote98 Consequently, the cultural mediator trainings that were finally held in 2017 were financed (as a step in) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Local-level challenges related to REDD+

Through participatory observation at those trainings and background conversations with members of the ADIIS and the communities, we have been able to identify various challenges related to the local-level experiences of REDD+ preparation in the Bribri territories. They complement and further specify the issues that have been raised above and reveal the obstacles that indigenous peoples might face when it comes to engaging with central government and international actors in determining the course of natural resource governance in their territories.

To start with, the Bribri communities have experienced a twofold epistemic concern with view to the REDD+ preparation. First, and against the background of their complex and circular cosmology indicated above, the Bribri people do not relate to the concept of the environment. Instead, they believe that the divine is manifested throughout the physical realm, often involving a higher spirit (Sibö). Thus, it is highly important to maintain a good relationship with the Creator God, with the numerous spirits governing natural phenomena and with the forces that are present in nature. The perception of Bribri people of forest ecosystems is that the forests provide everything that is needed, including intangible assets, and each element that is given by nature (forests, soil, water and air) has a special function that needs to be taken care of without attributing any monetary value to it. Traditionally, the respect for nature has been considered an essential element of human nature. Thus, the PES approach – with the notion of services as a foreign term – has not been easily comprehensible for those groups, which has led to challenges in terms of developing a co-ordinated policy position to be introduced in a meaningful way at the national level or in exchange with foreign actors. Relatedly, and second, there has been little understanding about the REDD+ approach in general. At this point, it becomes evident how the assessment of the material, ideational and symbolic aspects of natural resource governance depends on the ontological premises that are presumed. In the training programme, this challenge has been resolved by talking about benefits instead of services.

With view to the local organisation of political representation, one of the limitations for the meaningful participation of all those (potentially) affected by REDD+ has been that not all members of the community feel represented by the ADII. Therefore, any decision-making process related to a consultation process should also consider other local organisations like, for example, the customary court, the Council of elders, community leaders, Health Committees, fire brigades, member of traditional security and school committees. In turn, broadening the scope of participating actors to ensure reprensentativity and transparency in the process comes with higher transaction costs in terms of co-ordination and decision-making.

When it comes to the scope of REDD+, our interviews suggest that the Bribri communities have not experienced any broader socio-economic development or co-benefits in their communities to be derived from this type of forestland governance. Instead, the community members commented that they continued to face limited employment opportunities, resulting in migration of young people to urban areas.

Conclusions

In this article, we have approached the topic of natural resource governance and conflict against the background of a Political Ecology reading of multilevel natural resource governance. To enhance our understanding of resource complexities at different levels and be able to develop policy recommendations for concrete action on the ground, we have applied this perspective to the issue of indigenous engagement in forest-based carbon mitigation (REDD+). REDD+ (and its accompanying preparedness processes) is in principle open for land grabbing, exclusion and conflict-escalation (at local levels) as the interests of foreign investors, local populations, government actors, multinational organisations and local investors might clash. Social safeguards as developed at the international level promise to hamper such negative impacts and possibly come up with additional benefits in terms of local-level development. Yet, this global norm set needs to be translated to and implemented domestically. Thus, we have started by revising the development of REDD+ social safeguards at the United Nations and, subsequently, investigated the domestic practices to put those provisions into practice. To this end, we have analysed the engagement of local communities and indigenous peoples in the design of a National REDD+ Strategy in Costa Rica. We have traced developments at the national level and in the Cabagra and Salitre indigenous territories in Southern Costa Rica, and have shown how the production of landscapes and societies converges in a certain political territoriality that actors need to navigate (e.g. from the periphery to the centre in order to influence decision-making processes). We find that vertical and horizontal effects of natural resource governance related to REDD+ developed in material (e.g. financial support through multilateral donors), institutional (e.g. new policies and institutions) and symbolic/ideational (e.g. voice in national politics and recognition of indigenous cosmology) terms.

Key messages of our article include the following: first, we have found that multilevel linkages and dynamics do not come as a binary top-down or bottom-up dichotomy. Rather, feedback loops between the global, national and local levels exist. Thus, indigenous peoples in Costa Rica have been able to employ the political (shifting) spaces that opened up for them through the import of the global REDD+ script. This has led to new political configurations of consultation and stakeholder participation (including outlooks on future policy design) at the central level.

Relatedly, and second, by highlighting the relationships between political, economic and social factors on the one hand and environmental issues and changes on the other hand, we were able to depict the forest governance scheme REDD+ as an exemplary mechanism that would trigger the reconfiguration of relations between the state and non-state groups, e.g. indigenous communities. The prospect of including indigenous territories in REDD+ revitalised the domestic debate about the quality and organisation of indigenous autonomy, and led not only to learning processes within the indigenous communities themselves, but also on side of state bureaucracies. In analysing the country’s REDD+ preparation processes and the engagement of indigenous peoples therein, we have found that one very important aspect (aside of the REDD+ issue itself) was for indigenous peoples to create a platform to establish a permanent dialogue with the government. Hence, some empowering effects can be identified that spilled over from the formal provisions that had been established at the global level.

Third, local-level actors may find it challenging to relate to the vocabulary and concepts that are dominant at the national and global levels. Thus, cultural mediators have served an important function as transmitters between the different political levels, world views and language systems.

With view to policy recommendations, we want to highlight three issues: (1) it is crucial to transmit information from the national level to local level in a concise and simple language and build local capacities, e.g. facilitating discussion platforms, in order to also channel the information bottom-up to the national level; (2) land recover plans and conflict resolution mechanisms are important elements to prioritise and establish the resolution of land disputes to facilitate conflict mitigation beyond a specific policy issue such as REDD+; and (3) finally, enhanced inter-institutional co-ordination between national bureaucracies (e.g. MINAE and the Rural Development Institute) seems necessary to put indigenous peoples’ rights across diverging issue areas into practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the interviewees, especially from the central governmental agencies and from the Indigenous Associations of Integrated Development of Salitre and Cabagra, as well as the community leaders, for sharing their views, perspectives and information. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers and the co-editors for their valuable comments. This research has been partly facilitated and supported through the collaborative research project ‘Green Transformations in the Global South (GreeTS): opening the black-box of a pro-active state and the management of sustainability trade-offs in Costa Rica and Vietnam’ (www.greets-project.org), that is funded by the Volkswagen Foundation, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond and Wellcome Trust (‘Europe and Global Challenges’).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Linda Wallbott

Linda Wallbott is a postdoctoral researcher at the Chair of International Relations at the Institute of Political Science, Technische Universität Darmstadt, in Germany. In her research, she focuses on normative and empirical aspects of global environmental governance and the United Nations.

Elena M. Florian-Rivero

Elena M. Florian-Rivero works at the Climate Change Programme at the Agronomical Research and Higher Education Centre in Costa Rica. Her research and professional background focuses on strengthening social inclusion processes in national mitigation strategies linked to REDD+.

Notes

1. Geist and Lambin, ‘Proximate Causes and Underlying’.

2. UN-REDD, ‘About Redd+’; see also Levin et al., ‘The Climate Regime’.

3. ILO, Indigenous Peoples and Climate.

4. Voigt, ‘Introduction: The Kaleidoscopic World’, 2.

5. Schilling et al., ‘Introduction 14–15; Springate-Baginski and Wollenberg, REDD+, Forest Governance and Rural Livelihoods.

6. Lee and Pistorius, The Impacts of International.

7. Voigt, ‘Introduction: The Kaleidoscopic World’, 2.

8. Coalition for Rainforest Nations, ‘Vision’.

9. Borge Carvajal, PSA Indigena.

10. The term forestland regimes denotes ‘configurations of actors, authorities and institutions that regulate forest and land use’ and structures and working of political power in forested areas (Kashwan, Democracy in the Woods, 4).

11. Peluso and Watts, Violent Environments.

12. Schilling et al., ‘Introduction’.

13. Bryant and Bailey, Third World Political Ecology.

14. Robbins, Political Ecology.

15. Brand et al., Regulation and the Internationalisation.

16. Asiyanbi, ‘A Political Ecology’.

17. Sassen, ‘When Territory Deborders Territoriality’; Gregory and Vaccaro, ‘Islands of Governmentality’; see also Wissen, Gesellschaftliche Naturverhältnisse.

18. Le Billon, ‘Key Note’; Prause, ‘Land Grabs as ‘“Shrinking Spaces”’.

19. Schilling et al., ‘Introduction’, 4.

20. Ibid.

21. Fairhead et al., ‘Green Grabbing’; Corson and MacDonald, ‘Enclosing the Global Commons’; Phelps, ‘REDD+ Forest Carbon Investments’; Carmody and Taylor, ‘Globalization, Land Grabbing’.

22. Wallbott, ‘Indigenous Peoples in UN’.

23. Sandbrook et al., ‘Carbon, Forests and the REDD’.

24. UN-REDD, ‘Frequently Asked Questions’.

25. Lee and Pistorius, The Impacts of International, 5.

26. Aguilar-Støen, ‘Better Safe than Sorry?’.

27. Fisher and Lyster, ‘Land and Resource Tenure’.

28. Gover, ‘REDD+, Tenure and Indigenous Property’.

29. McDermott, ‘REDD+ and Multi-level Governance’, 88–89; Wallbott, ‘The Practices of Lobbying’.

30. UNFCCC, ‘Report of the Conference’.

31. Preparation (capacity-building; development of a national strategy or action plan; phase 1); implementation (demonstration of activities and piloting of strategy; phase 2); full implementation including results-based payments and MRV (phase 3). Phases 1 and 2 are also referred to as ‘REDD+ Readiness’.

32. UNFCCC, ‘Report of the Conference’, para 71. For a review of biodiversity safeguards and REDD+, see Wallbott and Rosendal, ‘Safeguards, Standards and the Science-Policy Interfaces’.

33. UNFCCC, ‘Report of the Conference’.

34. Ibid.

35. Werksman, ‘Q&A: The Legal Character’; Savaresi, ‘The Legal Status’, 130.

36. Forests News, ‘Durban Talks’.

37. Savaresi, ‘The Legal Status’, 131.

38. Arhin, ‘Safeguards and Dangerguards’; Wallbott, ‘Indigenous Peoples in UN’.

39. Voigt and Ferreira, ‘The Warsaw Framework’.

40. Sandbrook et al., ‘Carbon, Forests and the REDD’.

41. Howson, ‘Slippery Violence in the REDD+ Forests’.

42. FCPF, ‘The Carbon Fund’.

43. FCPF, ‘World Bank Safeguard Policies’.

44. ClientEarth, ‘Submission to the FCPF’.

45. Savaresi, ‘The Legal Status’, 149.

46. Ibid., 148.

47. Ibid., 135.

48. See also Jodoin, ‘The Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples’.

49. Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica, ‘Constitución Política’.

50. Sánchez-Azofeifa et al., ‘Costa Rica’s Payment’.

51. Alvarado, ‘Costa Rica Needs to Address’; Barquero, ‘Estudio de UCR’.

52. MINAE, Forest Reference Emission Level, 48.

53. Porras et al., Learning from 20 Years. For an overview of the conceptual approach see Gómez-Baggethun et al., ‘The History of Ecosystem’.

54. MINAE, Forest Reference Emission Level, 7.

55. Ibid., 11.

56. 45,799 hectares between 2010 and 2013; see FONAFIFO, ‘Indigenous Women’. Notably, when the PES was designed, there was no prior consultation of indigenous communities, even though their territories would be largely affected by this mechanism (Expert interview, Costa Rica, 4 April 2017).

57. MINAE, Plan de Implementación.

58. ánchez-Azofeifa et al., ‘Costa Rica’s Payment’.

59. Arriagada et al., ‘Do Payments Pay Off?‘.

60. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 26 June 2017.

61. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 24 March 2017.

62. UN-REDD, ‘Targeted Support 2nd Request’.

63. REDD Desk, ‘REDD in Costa Rica’.

64. MINAE, Forest Reference Emission Level.

65. MINAE, Emission Reductions Program.

66. Ibid., 6.

67. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 21 June 2017.

68. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 26 June 2017.

69. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 26 June 2017.

70. This finding also corresponds with results from a broader study on FCPF-related policy and legal reforms that would uphold or improve forest peoples’ rights and (local) forest governance (Dooley et al., Smoke and Mirrors).

71. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 21 June 2017.

72. Forests Peoples Programme, ‘Costa Rica: Indigenous Peoples’.

73. INEC, X Censo Nacional de Población.

74. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 23 March 2017.

75. Costa Rica, ‘Ley Indígena’.

76. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 24 March 2017.

77. Cultural Survival, ‘Costa Rica Struggles’.

78. Forest Peoples Programme, ‘Costa Rica: Indigenous Peoples’.

79. UN OHCHR, ‘Report on the Grave’, 2.

80. Cultural Survival, Costa Rica Struggles.

81. Sunderlin et al., ‘Creating an Appropriate Tenure’.

82. See also Sandbrook et al., ‘Carbon, Forests and the REDD’.

83. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 26 June 2017.

84. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 4 April 2017.

85. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 4 April 2017 (for an assessment of the World Bank’s strong influence in Costa Rica see also see Rosendal and Schei, ‘How May REDD Affect’).

86. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 21 June 2017.

87. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 23 March 2017.

88. Diquís is the name of a state-driven mega hydropower project in the Puntarenas de Buenos Aires province in Southern Costa Rica. Thus, Diquís is an example of how land use and energy politics interact and may lead to spill-over effects and social and ecological trade-offs in a broader perspective of green transformations (see also Lederer et al., ‘Tracing Sustainability Transformations’; Expert interview, Costa Rica, 27 April 2017).

89. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 21 June 2017.

90. For a thorough conceptualisation and application of ‘translation’ see Engwicht, ‘The Local Translation’.

91. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 10 June 2017.

92. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 21 June 2017.

93. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 27 April 2017.

94. Florian-Rivero, Fortaleciendo Capacidades de Negociación (I).

95. Florian-Rivero, Fortaleciendo Capacidades de Negociación (II).

96. Ibid.

97. Ibid.

98. Expert interview, Costa Rica, 21 June 2017.

References

- Aguilar-Støen, M., 2017. ‘Better Safe than Sorry? Indigenous Peoples, Carbon Cowboys and the Governance of REDD in the Amazon’. Forum for Development Studies 44(1), 91–108.

- Alvarado, L., 2018. ‘Costa Rica Needs to Address the Contamination of Its Rivers’. Available at: https://news.co.cr/costa-rica-important-issue-contamination-of-rivers/70150/ [Accessed 8 August 2018].

- Arhin, A.A., 2014. ‘Safeguards and Dangerguards: A Framework for Unpacking the Black Box of Safeguards for REDD+’. Forest Policy and Economics 45, 24–31.

- Arriagada, R.A., E.O. Sills, P.J. Ferraro and S.K. Pattanayak, 2015. ‘Do Payments Pay Off? Evidence from Participation in Costa Rica’s PES Program’. PloS one 10(7), e0131544.

- Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica, 1949. ‘Constitución Política de la República de Costa Rica’. Available at: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnacf600.pdf [Accessed 8 August 2018].

- Asiyanbi, A.P., 2016. ‘A Political Ecology of REDD+: Property Rights, Militarised Protectionism, and Carbonised Exclusion in Cross River’. Geoforum 77, 146–156.

- Barquero, M., 2018. ‘Estudio de UCR detecta residuos de plaguicidas, en bajas concentraciones, en fuentes de agua de zona norte’. Available at: https://www.nacion.com/economia/agro/estudio-de-ucr-detecta-residuos-de-plaguicidas-en/FFISZZCTM5FVHFS734VLCTMYL4/story/ [Accessed 8 August 2018].

- Borge Carvajal, C., 2003. PSA Indigena. MINAE-ACLAC-FONAFIFO, San José, Costa Rica.

- Brand, U., C. Görg, J. Hirsch and M. Wissen, 2008. Regulation and the Internationalisation of the State. Routledge, London.

- Bryant, R.L. and S. Bailey, 1997. Third World Political Ecology. Routledge, London.