ABSTRACT

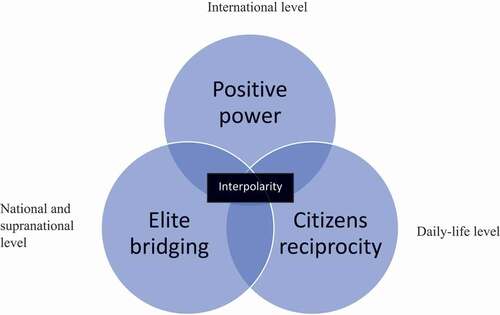

This Introduction to Special Issue (SI) seeks to provide a corrective dimension to unipolar and multipolar understandings of global order by proposing to integrate several levels of analysis. It seeks to introduce a different understanding of the contemporary world order. To this end, it first develops a new theoretical model of world order, putting forward the concept of interpolarity. Interpolarity is understood as the interaction between multiple interdependent poles of different sizes. The main utility of this concept is that it can provide a theoretical foundation for integrating means, ways, and ends in a more stable manner. Second, this Introduction to SI estimates three main conceptual building blocks of an interpolar world order: positive power, citizen reciprocity, and elite bridging. The contributions in this Special Issue examine different aspects of the European security and foreign policy as part of the liberal international order – including the relations with NATO and the US –, EU actorness in cybersecurity governance, French-German cooperation, role conceptions and differentiated integration, as well as the BRICS perspective on world order.

Introduction

Is the notion of polarity still relevant in the contemporary international security order? The bipolar international order during the Cold War was followed by a unipolar moment, which has been evolving into a multipolar system with the rise of BRICS and European powers (Blagden Citation2015). It is well known that a multipolar international system is predicted to be the least stable model in international relations and global politics. Recent global developments have been surrounded by an obvious sense of tension, uncertainty, and instability. Seeking to provide a conceptual understanding of the contemporary world order that can address some of the drivers of these tensions, this Special Issue theorizes the notion of interpolarity.Footnote1

In the last decades, research has conceptualized the international system as anarchy (Waltz Citation[2008] 1979; Mearsheimer Citation2001), multi-order (Flockhart Citation2016), multipolarity (Laatikainen Citation2012), international regimes (Krasner Citation1983; Hasenclever et al. 1997), multiplex world (Acharya Citation2017), global constitutionalism (Lang and Wiener Citation2017), world society (Wendt Citation2003), society of states (Bull Citation1977), complex interdependence (Keohane and Nye Citation1977; Henry and Newman Citation2019) or world system (Wallerstein Citation2004). While this literature provides useful, although competing, explanations for foreign policy choices in general, research to date has not yet determined how to conceptually integrate ends, ways, and meansFootnote2 to overcome competition and contestation. This is partly because the literature on grand strategy (Silove Citation2018; Layton Citation2018; Mykleby et al. 2016; Biscop Citation2021; Simon Citation2013) has been largely disconnected from theories of the Liberal International Order (LIO) (Mearsheimer Citation2001, Citation2019; Ikenberry Citation2001, Citation2012, Citation2020; Jahn Citation2000, Citation2017, 2018; Porter Citation2020; Cooley and Nexon Citation2020), with the latter having developed largely in separation from each other themselves. This Special Issue addresses this shortcoming by suggesting that the integration of means, ways, and means needs to be reflected at three levels: the international level, the national level, and the citizen level. Each of them constitutes distinct levels of governance, interactions, power relations, enactment, and knowledge production.Footnote3 The concept of interpolarity sheds light on the dynamics at these three levels and on how to bridge them.

The contributions in this SI robustly elaborate on different aspects of European security and foreign policy as part of the LIO, such as relations with NATO and the US, role conceptions, regulatory objectives in emerging policy areas such as cyber security governance, foreign policy objectives post-Brexit, and the case of BRICS. They combine conceptual and empirical analyses to study the political, societal, economic, and military factors in the context of an evolving international security order. These cases provide insights on key aspects of the dynamics at the three levels of governance, informing thus the proposed multifactorial model of interpolar order. Based on empirical insights from the cases studied in the Special Issue, we estimate three major dimensions of interpolarity: positive power, elite bridging, and citizen reciprocity. These elements shall be seen as fluid and in a permanent state of interdependence rather than in a position of fixed relationality.

The contribution of this research is twofold. First, it seeks to make a series of corrective claims. On the one hand, it challenges the conceptual understanding of multipolarity and unipolarity, providing a new notion: interpolarity. We define interpolarity as the interaction between interdependent poles (see also Grevi Citation2009). We argue that interpolarity is more adequate to understand the contemporary world order because it allows the integration of smaller poles and non-state poles of power, which have increased agency in international affairs. The problem with unipolar or multipolar orders is that both pave the way for contestation as well as competition.

The notion of interpolarity matters because it can capture the conceptual interpolation between three levels of governance, interaction, and enactment, i.e. the local, the national, and the international level, which can be seen as sites of agency, knowledge production, and power struggles (Richmond Citation2017). This introductory article generates key insights into each of the three levels, helping to better understand how to link the different layers. The mismatch between these different layers seems to be linked to some inherent contradictions of the LIO. The failure of the LIO to bridge the demands of liberal markets with “national autonomy,” along with economic dysfunctions that have impacted at citizen level, has led to weakening support for regional integrated orders over national sovereignty but also to the success of nationalist, populist, or illiberal parties (Colgan and Keohane Citation2017). Our notion of interpolarity takes stock of the different levels of governance, interaction, and enactment. To this end, the contributions in this Special Issue consider not only system- and unit-level variables but also pressures coming from the daily-life level of power relations and interaction, such as interactions between actors holding different ideological beliefs or between actors with different foreign policy ambitions.

Second, the SI sheds new light on corollary notions helping to conceptualize and operationalize a foreign policy model able to cope with competition and contestation. We do this through the generation of a multifactorial conceptual model of interpolar order that is based on the cumulative findings of the contributions in this Special Issue.

This Introduction proceeds as follows: first, it elaborates on the inherited contradictions of the LIO. Second, it discusses the proposed model of interpolar order. The third section presents the contributions of the SI. Finally, the last section discusses the limitations of the proposed conceptual model and suggests avenues for future research.

The inherited contradictions of the LIO

The research gap examined in this Special Issue consists in the lack of conceptual understanding about how to overcome the inherited contradictions of the LIO. The inherited contradictions of the LIO unleash competition and contestation, which puts the LIO in crisis. Overcoming competition and contestation is important in order to find ways of providing a sense of stability in the contemporary and future world order. This section discusses the inherited contradictions of the LIO more in-depth. We argue that there are two major shortcomings of the LIO that unleash the dynamics of competition and contestation. These are related, first, to the number and relation between poles. Second, they relate to the failure of the LIO to deliver for all and to become an objective reality. This might help us better understand why means, ways, and goals based on liberal order assumptions have, paradoxically, sowed illiberalism and allowed the proliferation of autocratic tendencies. In the following, we unpack this one by one.

Realists, liberalists, and constructivists hold somewhat competing views on the global order and the deep roots of the LIO’s crisis. Liberalists claim that liberal internationalism has not commenced in 1945 or 1989, but already earlier and it has since undergone considerable transformations and shifts (Ikenberry Citation2020). The strategic realignment on liberal-democratic values and the establishment of international and regional institutions on a normative basis after the end of the Second World War have epitomized a new kind of order and world system (Ikenberry in LSE Citation2021). The stability of this order started to shake after the end of the Cold War. Since 1989, there has been a gradual loss of conditionality, with phenomena like forum-shopping (Ikenberry Citation2020; see also Hofmann Citation2019) being observed in the global order. This means that sovereign states pick and choose from the collective outcomes while failing to attain the adequate level of responsibility to maximize the goals or comply with the rules. Although the end of the Cold War was conceptualized as the end of the history (Fukuyama Citation1992; see also Ikenberry Citation2001), the ensuing order did not exhibit the stability that one would associate with an end, rather the opposite was the case. Realist scholars offer a much more parsimonious image of the LIO, defining the international order as an order that includes all great powers and the LIO as a global order led by one liberal great power (Mearsheimer in LSE Citation2021). In this view, the LIO rather takes the shape of a unipolar order, led by a hegemon. Stability is ensured through “hegemonic stability” that involves the unipole’s coercion and simultaneously freedom to pursue its power, in other words, absence of great power competition (Kindleberger Citation1981; Mearsheimer Citation2001; Webb and Krasner Citation1989; see also Wohlforth Citation1999; Waltz Citation[2008] 1979). Thus, realists claim that the beginning of the unipolar moment (see Brands Citation2016) marks the beginning of the LIO, while holding that during the Cold War there were two bounded orders. Mearsheimer (Citation2019) predicts that the future world order will be consisting of three different orders: one concerned with arms control and efficiency of the global economy, and two bounded orders, one led by China and another pole under US leadership. Russia is predicted to become the weakest of the three great powers, while Europe is anticipated to become part of the US-led order.

Interestingly, both Ikenberry and Mearsheimer outline that the rules-based international order is a liberal hegemonic order, with the US leading the international equilibrium, and being the “owner and operator” of the world order (Ikenberry Citation2009; see also Ikenberry Citation2012). There seems to be a common understanding that American interventionism abroad, commencing with Bush’s War on Terror, invasion of Iraq, the war in Afghanistan, etc., have had a backlash effect both at home and abroad. Abroad, interventions have been often perceived as infringements of the sovereign authority of states, dropping off the acquiescence to US hegemony. At domestic level, in the US and elsewhere, the sources of contestation of the LIO are linked to its failure to fulfil promises such as bringing peace, equality, economic prosperity, and social justice.

Constructivists challenge the idea of a mainstream LIO as an objective reality. The constructivist critique consists in disputing the “universal validity of a certain form of political organization derived from a universal state of nature,” because such a state leads to an understanding of the global order based “on a hierarchy of cultures” (Jahn Citation2000, xiv). Not only has the LIO failed to produce the promised benefits, but instead it has generated increased inequality, divisions, and multiple crises (refugees, migration, security, financial, and environmental) and promoted the privatization of basic services such as health care and the exportation of jobs (Jahn in LSE Citation2021). Paradoxically, the liberal order has allowed for the emergence of illiberalism, contestation, and populism. The LIO seems thus to be challenged on all its pillars, i.e. economic, political, and ideological (see Jahn in LSE Citation2021). As a capitalism-based world economy has yet failed to produce benefits for all, liberal democracy as an overarching or “hegemonic” regime seems to have failed to appeal to all states, leading to eroding international law and human rights regimes and norms. The LIO is argued to have failed to become an objective reality and to be seen as foundational by all (see Jahn Citation2000). Punishment, for example, via the means of international sanctions or coercive or interventionary actions, has not yet provided a corrective dimension of the world order, but it has rather exposed some inherent sources of discontinuity, such as contestation and competition.

Through the globalization of liberal principles, the post-Cold War liberal institutional order is perceived to have undermined the separation between the domestic and international spheres (Jahn in LSE Citation2021), unleashing insurmountable problems. To overcome competition and contestation, from a constructivist perspective, two conditions are necessary: a more distributive social order (Jahn in LSE Citation2021) and the provision of collective public goods. A more distributive global order could neutralize the emergence of competing normative orders. Competition is defined as the rivalry between actors over a political good in the sense that possession by one (or several) excludes possession by other actors, thus being zero-sum. In the field of economics, competition emerges when the introduction of a product that brings benefits to an actor triggers responses by other actors in the playing field who seek to either imitate or block (undermine) the first actor’s actions (Smith et al. Citation2005, 309). While in the economic realm competition can be beneficial for enhancing innovation, in the field of security, competition has counter-productive effects on the stability and security of the international system, as the notion of security dilemma demonstrates (Herz Citation2003). By stemming from a reciprocal process of action (strategy) and reaction (Schumpeter Citation2010), especially in the field of security, defense and foreign policy, competition can evolve into a more subversive process. Competition is not linear, in the sense that actors can be adversaries in one domain and strategic partners in another. The absence of competition is a premise for a world order equilibrium in which actions are predictable and non-hurting.Footnote4 Contestation can be seen as antithetical to compliance and can take the shape of social practice or mode of critique (Wiener Citation2014). Depending on the moral reach and type of norm – principles or values, organizing principles or standard and regulations – norms can vary in their bargaining potential and potential for contestation (Wiener Citation2017). Principles or values are easier to contest, as they are less fixed, while standards or regulations are more difficult to contest. Contestation is anticipated to be determined by logics of appropriateness that influence role perceptions at micro or macro levels. This is because people and states will tend to contest meanings, values, policies, and institutional settings that are perceived to not be compatible with or “appropriate” to their set of expectations and beliefs. Ewers-Peters and Baciu (forthcoming, this Special Issue) shed more light into the micro-grains and relevance of logics of appropriateness (and consequentialism) to foreign policy and order in general. While contestation, disagreement, or even dissent are intrinsic to liberal-democratic principles, a situation of continuous contestation reaching changes in the third type of norms above, i.e. standards or regulations, would lead to the termination of the LIO.

The literature on grand strategy (Silove Citation2018; Lissner Citation2018) has provided some useful insights into the significance of means, ways, and goals and their utility for tacking stock of the LIO. Meanings are defined as the instruments through which foreign policy is conducted and the global order can be shaped. The ends constitute the goals and objectives that are aimed to be achieved. Means constitute the modality through which specific ends can be accomplished. Some studies have, for example, suggested the integration of ways, means, and goals to restore a collective American view of the future (Mykleby et al. 2016) or proposed a comparative research programme on grand strategy (Balzacq et al. Citation2019). In his 2018 book, Peter Layton seeks to provide some theoretical foundations for integrating means, ways, and ends, by distinguishing between two objectives, applying power and building power, and three conceptual grand strategy schemes: denial, engagement, and reform. While this research draws on impressive historical material to explain the three types of strategy schemes, it engages little with contemporary issues of competition or contestation. Pioneering research on European grand strategy (Biscop and Coelmont Citation2012; Biscop Citation2018, Citation2021; Winn Citation2013; Smith Citation2011) provides an insightful perspective on grand strategy, by critically engaging with Europe’s strategy, its foreign relations with NATO, neighbors, great powers, or third countries such as the UK. The greatest merit of this work is that it provides a real-world assessment of Europe’s potential and limits in international politics and how values and geopolitics factor in. The research by Luis Simon (Citation2013) adds to this debate by providing an empirical exploration of grand strategy from the perspective of EU-NATO relations and the role of the “big three” (France, Germany, the UK). Most recently, the book by Bart Szewczyk (Citation2021) proposes a framework for European grand strategy underpinned by four elements: policy planning, liberal foundations, managing Russia’s decline, and countering China’s assertiveness. While these studies provide useful empirical insights into complex political, ideological, economic, institutional, and geopolitical processes, the conceptual underpinnings of the LIO's inherent contradictions outlined earlier in this section are less understood.

This SI holds that a world order rooted in the notion of interpolarity can provide more clarity on the underpinnings of LIO's inherent contradictions, and thus provide some new ramps for better understanding the problem matter. To illustrate the argument, this SI builds upon the insights generated by seven articles. These articles draw on the case of European security order as part of the LIO, integrating both the national and supranational levels of agency, and we complement this by other cases, such as BRICS. We cover an extensive pool of European states, including France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Romania, and the UK, as well as the transatlantic component of European security by tackling NATO and the US. The inclusion of BRICS in this SI allows us to integrate perspectives from the Global South and ensure variation in our sample and thus enhanced validity of our conclusions.

Three levels of enactment in an interpolar world

This section unpacks the concept of interpolarity. A state of interpolarity is underpinned by three interconnected levels of enactment: citizen level, elite level, and the level of power relations. Enactment refers to the active expression of agency, and the phenomena of social construction of a reality. While our interpolar model of world order does not claim exhaustivity, it argues that citizen reciprocity, elite bridging, and positive (non-zero sum) power relations are central to a horizontal system of order, as illustrated in . Interpolarity starts from the assumption that a condition of fixed understanding of the global order raises unrealistic demands for overcoming diversity and culture (see also Jahn Citation2000, 169). It focuses on unpacking an epistemological model that can allow for the integration of diversity, presenting three dimensions. The three dimensions shall be seen as fluid and interlinked and not in a position of fixed relationality.

Interpolarity is defined as an international order featuring interdependent poles of different sizes that interact. Poles can be epitomized by states, inter-governmental organizations, non-state actors, and other agents. Previous engagements with the notion of interpolarity have been rare. In the only existing study on this notion, Grevi (Citation2009) rightly points out that interpolarity can be interest-driven, problem-driven, and process-oriented; however, the concept has since been little theorized. The employment of the notion of interpolarity or unipolarity allows us to capture not only middle and smaller powers in the international security order, such as Italy or Romania, but also fluid processes of multi-track power diffusion. Some scholars argue that ordering can be intrinsically non-liberal, as international orders can be seen as hierarchies created by strong powers to impose their vision of peace (Porter Citation2020) and, not ultimately, interests. To transcend this hierarchical structure, an interpolar setting is underpinned by internetworked and more horizontal dynamics (see Baciu and Kotzé 2022, this Special Issue) that are interdependent. The interplay between poles of different magnitudes, driven by various role perceptions, combinations of absolute and relative gains as well as normative expectations articulate logics of consequentialism and appropriateness. These logics are important as they can shed more light on how the views on conditionality are achieved. Conditionality diminishes directly proportional to eroding multilateralism. While a pole might not comply with certain provisions due to the risk of sanction or exclusion, it might do so subsequent to normative or economic leverages. Yet norms diffusion, development aid, or conditionality does not always actuate liberal values. As Baciu and Kotzé (forthcoming, this Special Issue) demonstrate, BRICS almost never mention the word “liberal” in their summit declaration, yet the words “democratic,” “just” and “human rights” are mentioned in nearly every declaration. As a form of contestation of what is perceived to be a Western-led LIO, BRICS focus much of their discourses on the UN system and forge a state-centric perspective in which nation-states are sovereign. Therefore, a major contribution of the notion of interpolarity is its corrective dimension to multipolarity, respectively, to unipolarity. Particularly, it provides a deeper understanding of how to bridge the IR discipline and the “social glue,” which is argued by existing debates to be a major shortcoming of multipolarity (Jahn in LSE Citation2021). In the following, we explain how this social glue dimension is enacted at citizens, elite, and power-relations level.

The citizen reciprocity dimension of our interpolar world model holds that citizens are at the heart of politics and are the main source of its legitimacy. Citizen reciprocity is defined as relational empathic projection of solidarity at micro-micro (interpersonal, society), micro-macro (citizen-national government/international organization) and macro-macro (national government-international organization) level. It is relational because it involves references to the “other,” and thus bridging dynamics. It is empathic because it involves recognition, assimilation, integration, and thus validation of the “other.” For example, the centrality of citizens in our model starts from the assumption of the social contract and presumes that the transfer of power from citizens to the Leviathan was justified by the guarantee of stability, citizens’ security, freedom and justice for all. Global governance, institutions and international law regimes can be seen as a corollary to enforce the social contract and protect citizens when nation states fail to do so. While the enforcement of the LIO might generate paradoxes of liberalism, the principle of citizens’ rights and safety is indivisible and inalienable. Global governance and existing international law regimes, although perhaps seen by some as intrinsically non-liberal given their ordering structure and principles, serve as guiding framework to formulate and debate redlines and actions. The absence of order might lead to a permanent state of nature, anarchy and possible war of all against all, although a universal state of nature is also disputed (Jahn Citation2000). Global governance actors such as international organizations and powerful states have corrected their strategy, blending top-down with bottom-up approaches. The overarching goal of the bottom-up turn to hybridity and peace formation (Richmond Citation2016; see also Visoka Citation2016) from below is to empower fragile societies and local communities, while simultaneously permeating norms diffusion to enable change. While global governance might not always be entirely successful in democratizing institutions, through supporting local actors’ activities, such as security sector reforms, it can facilitate changing discourses and increased awareness (Baciu Citation2021). In case of a conflict of interest between the international actor and local organizations, the view of the local organizations is anticipated to prevail. Especially in hybrid orders, developmental approaches of institutional change through building peace infrastructures and empowering local communities might be more acceptable to both citizens and governments, but also more successful in changing norms as a by-product in contrast to more radical approaches of norms conversion (Ibid. 2021). The provision of basic needs on one side, and providing logics of appropriateness on the other side can facilitate the formation of social capital and bridging citizens. A substantial strand of research finds a positive correlation between economic development and social cohesion (Sommer Citation2019; Vergolini Citation2011). This is because higher income and a stable economic situation can be associated with higher levels of trust, interaction, participation and thus reciprocity, allowing long-term building of relationships and social links. The link between democracy and participation has been theorized already by Alexis de Tocqueville, who argued that there is a correlation between American democracy and participation in voluntary associations (de Tocqueville and Reeve Citation1889). More recent research has theorized the link between peace and social capital (Kilroy Citation2021). The societal organization along the principle of reciprocity within the framework of “certain premodern cultural habits” has long been claimed to be a conditio sine qua non for democratic or capitalistic systems (Fukuyama Citation1996, 11). This is mainly because the logic of consequentiality is not sufficient to provide social glue in post-industrial societies. Citizen reciprocity can thus complement the rational choice dynamics with logics of appropriateness and persuasion.

Elite bridging is a further important dimension in an interpolar world. Elites refer to influential individuals across sectors such as government, bureaucracy, political parties, private sector, civil society, media, or research (Scholte et al. Citation2021). Elite discourses and political parties can play extremely influential roles, especially in the case of use of force (Wagner et al. Citation2018; see also Ostermann Citation2017; Stengel Citation2020). Elite bridging is defined as the inter-elite relationship of trust and reciprocity. It refers to connecting elites from the same country as well as from various countries. Elite bridging is important due to two reasons: first, it is a premise for achieving collective action or consensus, and second, it constitutes a crucial determinant for robust political institutions. While societal bonds and participation are important, too, the absence of strong political institutions can raise new security threats and challenge democratic culture (Berman Citation1997). Institutional political orders are especially needed to overcome crises, whether financial, health, or environmental. The lack thereof would reassemble a state of orderlessness or could even take the shape of state failure or terminal decline. Elite bridging thus becomes a condition for actuating agency and actorness, both at domestic and supranational level, whether as a regulation setter, norm promoter, or security provider. These latter dynamics are more profoundly illustrated by Chen and Gao (forthcoming, this Special Issue) based on the study of EU actorness in cyber policy governance. Moreover, fragmentation or lack of adequate levels of ambition might be associated with reduced capacity and absence of an overarching vision (see also Cladi, forthcoming, this Special Issue).Footnote5 Elite attitudes also matter for global governance processes (Scholte et al. Citation2021) and for the adoption of reforms. Elite bridging might be premised by a common denominator for a sub-LIO as an objective reality, in the sense that human rights, citizen freedoms, and the rule of law shall be non-negotiable. In an interpolar environment, players, whether states, inter-governmental organizations, or private actors, can hold different perceptions of reality, depending on their different role perceptions or resources (see Ewers-Peters and Baciu, this Special issue). The different roles can be seen as building blocks of regional or international orders. Through their annual summits, BRICS, G7, or G20 constitute important fora for advancing international debates and coordinating policy. While they constitute important enablers of interaction and elite bridging, their work, however, has been hitherto largely focused on financial stability and growth. In the field of security, the UN General Assembly, the EU, the NATO, or more informal sessions, such as the Munich Security Conference, constitute some platforms of interaction; however, the potential of the latter for norms diffusion is relatively low, as elites usually present and infromally exchange their foreign policy visions.

Power relations constitute a further important conceptual level for our understanding of an interpolar world order. Dovetailing with the previous two dimensions (citizens and elites), our model holds that there are three levels of power relations that revertebrate in normative expectations, and knowledge construction: the international level of global governance, the national level of domestic government and bureaucracy, and the micro-level of daily power relations (see Richmond Citation2017, 637). These three levels can also be seen as sites of exertion of authority, contestation, and legitimacy construction. Positive power is defined as co-relational power (see Baciu and Kunertova, forthcoming), in which the power of one actor is not detrimental to the power of another actor, but it is instead a sum of trans-cooperative interactions between two or more actors. The normative advantage of a positive understanding of power is that it embodies agency and actorness without activating the spiral of great power competition. The notion of positive power is co-relational because it is understood as “power with” and not “power over.” The major difference between these two types of power is that the former underpins collective action, whereby the second implies a relationship of coercion, subordination, or ordering. Conceptions of hybrid or post-liberal peace (Richmond and Mitchell Citation2012; Richmond Citation2015; Boege Citation2021; Richmond Citation2017) seek to transcend these two extremes. On one side, “power with” can deter contestation due to its horizontal emergence and through providing a sense of ownership. On the other side, “power with” can deter rivalry, as a competitive dynamic would be undermining and self-damaging. While notions of power are likely to remain central to future world orders, a positive power prototype in the sense of “power with” seems to be more suitable for an international order with numerous poles of different sizes in an interdependent and globalized setting. Due to its horizontal design, co-relational power enables dynamics of power diffusions between various levels and poles, whether states, international organizations, or non-state actors, being able to facilitate convergence on common denominators. The multi-track dynamics facilitate internetworking and integration, enhancing support and legitimacy. This would constitute a key element to provide a corrective dimension to the LIO, which, as we discussed elsewhere in this article, has failed to produce benefits for all. Not only has it allowed for the rise of populism, nationalism, and norms contestation, but it has also ensued competition in the economic, normative, and military domains. A flat, non-hierarchical but internetworked power structure can ensure additional conditionality and compliance dynamics. These can be anticipated to emerge as a by-product of repeated interaction, which is sustained by the reasoning according to which repeated interactions can solve prisoners’ dilemmas (Axelrod Citation2006), prompting the evolution of stable Nash equilibria of cooperation.

To sum-up, it is the non-hegemonic and intertwined structure of the interpolar model of world order that can help achieving an equilibrium by transcending competition and contestation, being based on more cooperative and reciprocity (empathetic) potential than unipolar or multipolar structures. On one side, it enhances the system’s ability to counter exogenous threats by enhancing actorness through its elite co-optation and loop mechanisms. Citizen reciprocity can help overcoming internal (ideological) divisions and enhancing internal cohesion and popular support. On the other side, the model can contribute to rule compliance and ability to achieve envisaged objectives. As demonstrated by Deschaux-Dutard (forthcoming, this Special Issue), citizens and elites are more likely to comply with rules that they perceive as legitimate, which they support or tolerate out of solidarity and reciprocity reasons (see for instance Scharpf Citation1999). Involvement in “power with” based mechanisms does not only increase the sense of ownership and compliance, but it also diminishes the risk of defection. Due to co-participation in the system (co-relational power ecosystem), defection would be associated with greater costs than compliance. Finally, greater unity and consistency can augment actorness and the system’s ability to fulfil envisioned strategic objectives.

An equilibrium, aka stability, would involve that actors remain persistent on their strategies – they do not defect – to ensure predictability and resilience and that actors’ strategies evolve only in interdependence of each other. This would involve consensus among the ends and means between nation states. The UN system sought to assemble to some extent the idea of providing collective goods, along the principles of non-rivalry and non-excludability, however, the system continues to face several structural challenges. For example, from an international law perspective, General Assembly resolutions continue to have a non-binding character in contrast to UN Security Council resolutions. The UN Security Council, could have, in theory, emerged as a multilateral structure that guarantees the LIO; however, the frequent lack of consensus among P5 and unilateral actions have rather impeded such a scenario for the international system, which sometimes ends up equating an oligarchy (see Badie Citation2011). As competition and contestation become more and more acute, the question concerning the building blocks of a progressive agenda for world politics becomes imminent. We hope that our model of interpolarity can constitute an incipient step for enabling a better understanding of a world order that can integrate diversity and interdependence at different levels.

Outline of the contributions

This SI puts forward seven articles (this introductory article included), and a conclusion, in which the different aspects of the presented notion of interpolarity are critically assessed.

The main strengths of the research network involved in this SI are multidisciplinarity and diversity. It brings together established scholars and promising young scholars so as to help circulate the expertise and create a scientific possibility of exchanging between different generations and disciplines. The geographic outreach of this SI is immense, spanning across various cases and universities in Europe, the US and Africa. Offering a compelling robustness and value-added, the conceptual, methodological, and geographical diversity of the contributions are of utmost importance to fill an imminent research gap in an emerging debate.

The article by Xuechen Chen and Xinchuchu Gao assesses the case of the EU as an emerging pole in regulatory governance. It explores EU actorness in global cybersecurity governance, examining how the EU positions itself and what is has been able to achieve in this domain. To this end, the article investigates the evolution of the EU vision on the Internet and cybersecurity governance based on a critical assessment of key strategic papers. Moreover, the article contrasts the EU vision and governance with that of the US, but also to that of emerging or resurgent powers, such as China or Russia. In the light of an increasing level of ambition in the military domain and debates about strategic autonomy, the EU seeks to play a three-fold role in cybersecurity: regulation setter, norm promoter, and security provider. The analysis shows that the EU has advanced a series of important policy developments and regulatory means. This is demonstrated by its influence of regulatory norms. For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) stimulated debates and initiatives on the regulation of data protection in Asia, but also in the US and Canada, where GDPR was argued to have had an impact on the California Consumer Privacy Act. But, while the EU has sought to establish itself as a significant pole in the cybersecurity domain, it faces challenges in all three envisaged roles and is only partially able to fulfil them. The article is illustrative for the utility of a conceptual framework of interpolarity, as it allows to capture the agency of other important poles beyond great powers, such as big tech and private companies.

The article by John R. Deni illustrates the inner dynamics and challenges of an understanding of positive power, defined as “power with.” The article argues that, in a context of post pandemic peer competition, European like-minded allies could constitute a strategic comparative advantage for the US, which could strengthen bases of legitimacy both at domestic and foreign policy level. It analyses the evolution of the strategic outlooks of four European countries, France, Germany, Italy, and the UK, gauging the effects on the future US grand strategy. Empirically, it relies on national strategic documents in the period post Cold War, expert interviews, and secondary data sources. The article finds that, first, there is a significant mismatch between the strategic ambition and capacity of the examined cases. Specifically, in the case of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, the capabilities are not found to match their high levels of ambition. In contrast, in the case of Italy, the level of ambition was found to have been recalibrated in response to diminishing capacity and ability to act. The insights provided in this article can increase our conceptual understanding of how aspiring poles seek to enact and actuate their objectives, and also how challenges might arise when the ends are not matched by adequate means. Citizen-level factors, but also lack of elite consensus, might prevent an alignment of means, ways, and ends. With the exception of France, the analyzed countries are evaluated to lack the capacity to conduct self-responsible large scale military operations. Against this drawback, European countries are likely to continue to remain important bases of support for the US in providing global security and stability.

The article by Lorenzo Cladi provides important insights on the implications of polarity as factor of foreign policy choices. It also shows the challenges that the process of pole evolution might encounter, such as the search of new identity. The article examines European security cooperation from a neorealist perspective, by evaluating three case studies: US commitments to European security, EU collaborative security initiatives, and France’s European Intervention Initiative. The article argues that the decline in US commitment to the global order and fears of abandonment have stimulated EU activism in security and defense, seeking to keep the US engaged. The Brexit referendum and the UK withdrawal from the EU have also acted as intervening variables in European countries’ decision to step up cooperation, seen by advancements such as PESCO, EDF, or CARD. The analysis shows, first, that fragmentation among EU states and lack of adequate levels of ambition nonetheless diminished EU states’ hedging capacity. A second remarkable finding of the article is the steady evolution of European security cooperation after the Cold War despite the predominantly unipolar system, with the US as the sole superpower (as evidenced by the defense spending and other indicators) and the relative persistence of the European distribution of power and capabilities. One consequence of this, however, is that the EU defense initiatives, complemented by France’s European Intervention Initiative mechanism, have been able to strengthen the European pillar within NATO. At theoretical level, the article challenges some of the existing neorealist explanations with regard to Euro-Atlantic security cooperation. Most importantly, the article demonstrates that, while hedging has emerged as a popular explanation for EU activism in security and defense, this can be better understood as “continuous soul searching” as a characteristic of pole evolution.

Nele Marianne Ewers-Peters and Cornelia Baciu provide a new explanation for role conceptions in multilateral security orders such as the EU and NATO. Their findings advance our understanding of the dynamics shaping the behavior of smaller poles. The article integrates elite and citizen level through the consideration of logics of appropriateness and logics of consequentialism. The article shows how, in multilateral orders, states are driven by role player conceptions underpinned by both logics of consequentialism and logics of appropriateness. These take the form of several factors: absolute gains, relative gains, and normative factors. To test their model, the authors employ comparative research encompassing four cases: France, Germany, Ireland, and Romania. The notion of interpolarity is particularly useful as it allows for the consideration of smaller powers, such as Romania or Ireland, in interdependent processes of global relevance. The article demonstrates that the four countries exhibit genuine role player conceptions that are shaped by both elite perceptions and citizen-level attitudes: France takes the role of an agile power-projector, Germany embraces the role of a global responsibility taker, Ireland plays the role of a peacekeeping neutral, and Romania adopts the role of a small regional power. In their role conceptions, it is not only collective identity perceptions and strategic culture influencing states’ preferences but also elites’ concern for avoiding relative and absolute losses.

In her article, Delphine Deschaux-Dutard sheds light on the importance of the elite and citizen-related factors in decision-making in the security domain and in shaping state preferences in global and regional orders. Deschaux-Dutard examines how France and Germany try to address the challenges raised by the new world order by promoting a specific European way in the world through the concept of European strategic autonomy. Both European countries have promoted the idea of European actorness to preserve a liberal world order based on multilateralism and incarnated in the notion of European strategic autonomy. Yet, as this notion remains quite blurred, both countries have been active to give it concrete substance and made several proposals since 2016 to feed autonomy with military tools and capabilities designed at the EU level. The article employs the concept of input and output legitimacy, revisited by discursive institutionalism to make sense of European governance. The concept of legitimacy is helpful to understand tensions and how elite and citizen-level factors interact in generating coordination in a world more and more characterized by uncertainty and power competition. It also explains why the output of bilateral strategic initiatives tends to remain limited at the empirical level, as the two countries rely on diverging analyses of strategic priorities rooted in their strategic cultures and collective perceptions.

The article by Gorm Rye Olsen illustrates the importance of trust at both elite and citizen levels. It examines the reactions of European countries – and among them more specifically of France, the UK, and Germany – to the changes in the global world order in recent years. Relying on the concept of trust in foreign policy, the article first looks at the reaction of European states to recent changes in global power relations (e.g. the Trump era and the rise of China), and then focuses on the changes in their foreign policy behavior as a response to changes in American foreign and security policy during the last decade. The article advances an innovative three-level argument. First, it claims that European leaders, under the pressure of these changes, had to launch initiatives to counter the threats resulting from the new world order. Second, their decisions can be largely explained by the notion of trust, and, subsequently, the lack of trust in the American commitments to European security. Third, the author argues that European leaders have been unable to find a real consensus to address the new security challenges. To illustrate the argument, the author employs three empirical case studies: the consequences of the US transatlantic policy for the European NATO members, the European reactions to the Chinese behavior in the South China Sea and in the Indian Ocean, and the European reactions to the security situation in the Middle East.

The article by Cornelia Baciu and Klaus Kotzé provides an in-depth understanding of how BRICS, as emerging pole(s) of power, relate to the global order and the LIO in particular. The article provides key insights into an important aspect of interpolarity, namely how poles with different visions of order interact in the global environment. It employs summit declarations to assess BRICS rhetoric and performative practices. While BRICS uses rhetoric to contest some of the normative assumptions of the LIO, it simultaneously participates in practice in parts of the LIO, such as the UN system and operations. The blend of contestation on one side and mimetical re-production of the LIO through participation on the other side sheds new light on the dynamics between poles in an interpolar understanding of world order. Namely, the article helps us gain new knowledge about the power relation dimensions, and how “power over” is challenged and sought to be replaced with “power with.”

The concluding article by Özlem Terzi situates the notion of interpolarity in the broader IR discipline. The utmost significance of interpolarity lies both in its utility to provide a better conceptual understanding of interdependence in a globalized world, as well as in its potential as a normative approach to conceptualize IR that can help to transcend competition and contestation between poles. To this end, Terzi canvasses to what extent overcoming the tension between different poles prefigures a dilemma between interpolarity as a desirable goal on one side and a normative compromise on the values which these poles want to uphold in the international system, on the other side. Search for stability and conceptual models to prevent wars has been a central objective of the IR discipline since its emergence after the end of the First World War. Bipolar, unipolar or multipolar models of world order have been largely associated with balance of power, hegemony or rivalry between poles. Contestation as a phenomenon and practice in the global IR embodies a sense of rivalry between norms and of ‘whose interpretation of them should dominate an issue area’ (Terzi, forthcoming, this Special Issue).

Future research

This Introduction has proposed the notion of interpolarity to shed light into a condition of world order that can overcome competition and contestation, two undermining dynamics of the current international order. To assess the proposed theory, the SI contributions apply European security and foreign policy, including its transatlantic component, along with the case of BRICS, in order to draw on empirical examples to illustrate the key dimensions of interpolarity. Employing a trans-disciplinary perspective, this article has unveiled the notion of interpolarity as corrective to established conceptual understandings of world order, such as bipolarity, multipolarity or unipolarity. Interpolarity, understood as interdependence between poles of different sizes, is more suitable to understand current global dynamics because it is able to capture the agency of smaller poles that are not sufficiently reflected in unipolar, bipolar or multipolar definitions. The major shortcoming of these models is that they ignore smaller or post-colonial states, and non-state actors such as big tech concerns (e.g. Google or Amazon) that exert tremendous agency in international affairs. Moreover, all three are rather static models, and do not sufficiently address dynamics of power diffusion and globalized interaction. Interpolarity seeks to correct these drawbacks. It identifies three building blocks relevant to an interpolar world order: citizen reciprocity, elite bridging, and positive power. These three elements seek to bridge three levels of interaction and power relations, which shall be considered in any future model of world order, namely the citizen level (daily life), elite level (national), and international level (international organization).

Notwithstanding, four boundaries pertain to our proposed model, which could be addressed by future research.

The first one relates to the characteristics of the LIO, disregarding whether a realist interpretation of a hegemon-guaranteed LIO, or a liberal institutionalist interpretation of the LIO is applied, in which the rules-based order is upheld via international organizations and bargaining. If existing contradictions of the LIO have permitted the emergence of competition, growing illiberalism, and contestation, how can it be ensured that states will not re-produce these and other shortcomings related to global inequalities, in the future?

Second, while our model provides new knowledge on the conceptual understanding of security and reconciliation in the global order, for the parsimony of this article, it provided little elaborations on concrete mechanisms through which democratic or liberal values of human rights, freedom, and rule of law can be upheld. The article avoided to take a normative stance, and it instead sought to unpack how to bridge different orders. Future studies could elaborate on the dynamics and mechanisms through which the system can maintain values and explore more in-depth the dynamics and implications of re-distribution and how to attain benefits for all. The recent decision of the G7 summit to introduce a tax pertaining to big companies could be a decision contributing to this end. Interests, both in absolute and relative terms, are anticipated to be major determinants of future foreign policy and geopolitical decisions. The challenge will be, on one side, to find the legitimate and effective ways to reach the ends, and on the other side, to find a global consensus about the ends. Upcoming studies should dedicate more attention to the meaning of norms and rules, and under what conditions reaching mutual agreements on the use of force, arms control, or nuclear disarmament could be achieved.

Third, our model would benefit from more in-depth specifications of the interplay between internationalism and nation-state sovereignty and how to bridge the domestic and international spheres. The logic of conditionality embedded in the LIO does not always operate to the envisioned ends. While much progress has been achieved, as demonstrated by the UN sustainability goals, democratic values have been in continuous decline in the last decade. Future research could address the role and position of sovereign states in the international system. As Baciu and Kotzé (this Special Issue) demonstrate, state-sovereignism is central to the world vision propagated by BRICS. Future research could examine G7, G20, NATO, UN, or EU summits and seek to shed more light on the perceived role of state sovereignty in international organizations.

Lastly, security will continue to remain quintessential to any future global order, as the lack thereof would seriously restrict exchanges and cooperation in other domains, such as trade, academic collaborations, or travel. Collective security and defense can guarantee stability through deterring aggressions, yet controversies still remain. While this SI provides empirical knowledge related to security and strategy from a comparative perspective generating new cognition about the role of legitimacy, power diffusion, relative or absolute gains, and normative factors in international security and foreign policy, future research could explore more in-depth the normative and conceptual link between military means and aligned ends and how to reach an interpolar world order equilibrium. While our cases contribute to the elucidation of the overall concept of interpolarity, the generated conclusions take a middle-range level of generalizability. Thus, future research could assess our theoretical conclusions by expanding the case sample.

In sum, given the undermining and damaging potential of competition and contestation, a foreign policy underpinned by a vision of interpolarity and equilibrium can be anticipated to be central to upcoming debates on global IR. The conceptual utility of the notion of interpolarity lies in its potential to incorporate constitutive perspectives, knowledge and interests of ‘others’. Helping to conceptualize IR beyond Western perspective, an interpolar understanding can therefore contribute to advancing non-Western concepts and to a de-centralizing agenda by including ‘theories, concepts and predictions’ (Terzi, forthcoming, this Special Issue; see also Acharya and Buzan 2007 and Pinar 2010) from other poles and postcolonial countries. This Introduction, along with the articles in this Special Issue, seeks to contribute to this emerging debate.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Lene Hansen, Daniel Hamilton, Lene Holm Pederson, Mathilde Kaalund, Silije Synnøve Lyder Hermansen, Christoffer Hentzer Dausgaard as well as to the two anonymus reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions provided on previous versions of this article. The author would like to thank Ursula Schroeder and Ulrich Kühn for valuable support with the advancement of the Special Issue. A working session with all contributors has been hosted by the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg in April 2021. Especially during these exceptional times, tremendous thanks go to the editors and all reviewers involved in the double peer-review process of the contributions in this Special Issue, for steadily constructive, substantive, and timely feedback.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare none.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cornelia Baciu

Dr Cornelia Baciu is Researcher at the Centre for Military Studies, Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen. She specialized in security organizations, normative orders and conflict research. Previously, she was postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Peace Research at the University of Hamburg and at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC. Cornelia Baciu was teaching fellow at Maynooth University. She obtained degrees from Dublin City University, University of Konstanz, and Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi. She was visiting fellow at the University of Southern Denmark, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and the United Nations Office in Vienna. Her work was published in the Journal of Transatlantic Studies, Comparative Strategy, and other peer-reviewed journals. Dr Baciu published two books: Civil-Military Relations and Global Security Governance. Strategy, Hybrid Orders and the Case of Pakistan (2021) and Peace, Security and Defence Cooperation in Post-Brexit Europe (co-edited with John Doyle, 2019).

Notes

1. This notion adds to the concepts of polarity and power structures (Wæver Citation2017), and to the term of interpolar world order pioneered by Grevi (2009).

2. Means, ways, and ends generically refer to instruments, modalities of actions and objectives in foreign and security policy. The literature on grand strategy provides more profound definitions on these three elements.

3. The work by Oliver Richmond provides illuminating insights into the three levels of governance, power relations, and knowledge production.

4. Predictability of states’ actions is generally ensured via a rules-based system, in the framework of which members commit to a certain set of rules and expectations. The principle of non-hurting refers to not being detrimental to some groups of agents while creating advantages for others.

5. See “Persevering with Bandwagoning, Not Hedging: Why European Security Cooperation Still Conforms to Realism“ by Lorenzo Cladi in this Special Issue.

References

- Acharya, Amitav. 2017. “After Liberal Hegemony: The Advent of a Multiplex World Order.” Ethics & International Affairs 31 (3): 271–285. doi:10.1017/S089267941700020X.

- Axelrod, Robert M. 2006. The Evolution of Cooperation. Revised Edition. Rev. ed. New York: Basic Books.

- Baciu, Cornelia. 2021. Civil-Military Relations and Global Security Governance Strategy, Hybrid Orders and the Case of Pakistan. London and New York: Routledge.

- Badie, Bertrand. 2011. La diplomatie de connivence: Les dérives oligarchiques du système international. Paris: La découverte.

- Balzacq, Thierry, Peter Dombrowski, and Simon Reich. 2019. “Is Grand Strategy a Research Program? A Review Essay.” Security Studies 28 (1): 58–86. doi:10.1080/09636412.2018.1508631.

- Balzacq, Thierry, Peter J. Dombrowski, and Simon Reich. 2019. Comparative Grand Strategy: A Framework and Cases. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berman, Sheri. 1997. “Civil Society and the Collapse of the Weimar Republic.” World Politics 49 (3): 401–429. doi:10.1353/wp.1997.0008.

- Biscop, Sven. 2018. European Strategy in the 21st Century: New Future for Old Power. London: Routledge.

- Biscop, Sven. 2021. Grand Strategy in 10 Words: A Guide to Great Power Politics in the 21st Century. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Biscop, Sven, and Jo Coelmont. 2012. Europe, Strategy and Armed Forces: The Making of a Distinctive Power. London: Routledge.

- Blagden, David. 2015. “Global Multipolarity, European Security and Implications for UK Grand Strategy: Back to the Future, once Again.” International Affairs 91 (2): 333–350. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12238.

- Boege, Volker. 2021. “Hybrid Political Orders and Customary Peace.” In The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding, and Peace Formation, edited by Richmond, Oliver P. and Gëzim Visoka, 612–626. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brands, Hal. 2016. Making the Unipolar Moment: US Foreign Policy and the Rise of the Post-Cold War Order. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bull, Hedley. 1977. The Anarchical Society a Study of Order in World Politics. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- Colgan, Jeff D., and Robert O. Keohane. ”The Liberal Order is Rigged: Fix It Now or Watch It Wither.” Foreign Affairs 96 (3): 36–40, 42–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44823729.

- Cooley, Alexander, and Daniel H. Nexon. 2020. Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order. New York: Oxford University Press.

- de Tocqueville, A., and H. Reeve. 1889. Democracy in America. London, New York: Longmans Green.

- Flockhart, Trine. 2016. “The Coming Multi-Order World.” Contemporary Security Policy 37 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1080/13523260.2016.1150053.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. London: Penguin Books.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1996. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Free Press.

- Grevi, Giovani. 2009. ”The Interpolar World: A New Scenario.” Occasional Paper N° 79 . Paris: EUISS.

- Henry, Farrell, andAbraham L. Newman. 2019. “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion.” International Security 44 (1): 42–79. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00351.

- Herz, John H. 2003. “The Security Dilemma in International Relations: Background and Present Problems.” International Relations 17 (4): 411–416. doi:10.1177/0047117803174001.

- Hofmann, Stephanie C. 2019. “The Politics of Overlapping Organizations: Hostage-Taking, Forum-Shopping and Brokering.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (6): 883–905. doi:10.1080/13501763.2018.1512644.

- Ikenberry, G. J. 2001. After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. John. 2009. “Liberal Internationalism 3.0: America and the Dilemmas of Liberal World Order.” Perspectives on Politics 7 (1): 71–87.

- Ikenberry, G. J. 2012. Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order. Princeton, Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. J. 2020. A World Safe for Democracy: Liberal Internationalism and the Crises of Global Order. Politics and Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Jahn, Beate. 2000. The Cultural Construction of International Relations: The Invention of the State of Nature. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Jahn, Beate. 2017. “The Imperial Origins of Social and Political Thought”. In International Origins of Social and Political Theory, edited by Barkawi, Tarak and George Lawson, 9–35. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

- Jahn, Beate. 2018. “Liberal Internationalism: Historical Trajectory and Current Prospects.” International Affairs 94 (1): 43–61. doi:10.1093/ia/iix231.

- Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye. 1977. Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Kilroy, Walt. 2021. “Social Capital and Peace.” In the Palgrave Handbook of Positive Peace, edited by Standish, Katerina, Heather Devere, Adan Suazo, and Rachel Rafferty, 1–19. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. 1981. “Dominance and Leadership in the International Economy: Exploitation, Public Goods, and Free Rides.” International Studies Quarterly 25 (2): 242. doi:10.2307/2600355.

- Krasner, Stephen D. 1983. International Regimes. Cornell Studies in Political Economy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Laatikainen, Katie V. 2012. EU Multilateralism in a Multipolar World. London: Routledge.

- Lissner, Rebecca F. 2018. “What Is Grand Strategy? Sweeping a Conceptual Minefield (November 2018).”

- London School of Economics (LSE). 2021. “‘World on the Edge’: The Crisis of the Western Liberal Order.” Accessed 13 June 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2S9cOeYV-n8

- Mearsheimer, John J. 2001. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton.

- Mearsheimer, John J. 2019. “Bound to Fail: The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order.” International Security 43 (4): 7–50. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00342.

- Ostermann, Falk. 2017. “France’s Reluctant Parliamentarisation of Military Deployments: The 2008 Constitutional Reform in Practice.” West European Politics 40 (1): 101–118. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1244751.

- Porter, Patrick. 2020. The False Promise of Liberal Order: Nostalgia, Delusion and the Rise of Trump. Cambridge, Medford MA: Polity.

- Richmond, Oliver P. 2015. “The Dilemmas of a Hybrid Peace: Negative or Positive?” Cooperation and Conflict 50 (1): 50–68. doi:10.1177/0010836714537053.

- Richmond, Oliver P. 2016. Peace Formation and Political Order in Conflict Affected Societies. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Richmond, Oliver P. 2017. “The Paradox of Peace and Power: Contamination or Enablement?” International Politics 54 (5): 637–658. doi:10.1057/s41311-017-0053-9.

- Richmond, Oliver P., and Audra Mitchell. 2012. Hybrid Forms of Peace: From Everyday Agency to Post-Liberalism. Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Richmond, Oliver P., and Gëzim Visoka, eds. 2021. The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding, and Peace Formation. New York: Oxford: University Press.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scholte, Jan A., Soetkin Verhaegen, and Jonas Tallberg. 2021. “Elite Attitudes and the Future of Global Governance.” International Affairs 97 (3): 861–886. doi:10.1093/ia/iiab034.

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 2010. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London: Routledge.

- Silove, Nina. 2018. “Beyond the Buzzword: The Three Meanings of 'Grand Strategy'”.” Security Studies 27 (1): 27–57. doi:10.1080/09636412.2017.1360073.

- Simon, Luis. 2013. Geopolitical Change, Grand Strategy and European Security. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smith, Michael E. 2011. “A Liberal Grand Strategy in a Realist World? Power, Purpose and the EU’s Changing Global Role.” Journal of European Public Policy 18 (2): 144–163. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.544487.

- Smith, Ken G., Walter J. Ferrier, and Hermann Ndofor. 2005. “Competitive Dynamics Research”. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management, edited by Hitt, Michael A. 309–354. Oxford: Blackwell Publ.

- Sommer, Christoph 2019. “Social Cohesion and Economic Development: Unpacking the Relationship.” Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik.

- Stengel, Frank A. 2020. The Politics of Military Force: Antimilitarism, Ideational Change, and Post-Cold War German Security Discourse. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Szewczyk, Bart M. J. 2021. Europe’s Grand Strategy: Navigating a New World Order. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vergolini, Loris. 2011. “Social Cohesion in Europe: How Do the Different Dimensions of Inequality Affect Social Cohesion?” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52 (3): 197–214. doi:10.1177/0020715211405421.

- Visoka, Gëzim. 2016. Peace Figuration after International Intervention: Intentions, Events and Consequences of Liberal Peacebuilding. London, New York: Routledge.

- Wæver, Ole. 2017. “International Leadership after the Demise of the Last Superpower: System Structure and Stewardship.” Chinese Political Science Review 2 (4): 452–476. doi:10.1007/s41111-017-0086-7.

- Wagner, Wolfgang, Anna Herranz-Surrallés, Juliet Kaarbo, and Falk Ostermann. 2018. “Party Politics at the Water’s Edge: Contestation of Military Operations in Europe.” European Political Science Review 10 (4): 537–563. doi:10.1017/S1755773918000097.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2004. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Waltz, Kenneth N. [2008] 1979. Theory of International Politics. Boston, London: McGraw-Hill.

- Webb, Michael C., and Stephen D. Krasner. 1989. “Hegemonic Stability Theory: An Empirical Assessment.” Review of International Studies 15 (2): 183–198. doi:10.1017/S0260210500112999.

- Wendt, Alexander. 2003. “Why a World State is Inevitable.” European Journal of International Relations 9 (4): 491–542. doi:10.1177/135406610394001.

- Wiener, Antje. 2014. A Theory of Contestation. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Wiener, Antje. 2017. “A Theory of Contestation—A Concise Summary of Its Argument and Concepts.” Polity 49 (1): 109–125. doi:10.1086/690100.

- Winn, Neil. 2013. “European Union Grand Strategy and Defense: Strategy, Sovereignty, and Political Union.” International Affairs Forum 4 (2): 174–179. doi:10.1080/23258020.2013.864887.

- Wohlforth, William C. 1999. “The Stability of a Unipolar World.” International Security 24 (1): 5–41. doi:10.1162/016228899560031.