ABSTRACT

The urgent and interlocking social, economic and ecological crises faced by societies around the world require dialogue, empathy and above all, hope that transcends social divides. At a time of uncertainty and crisis, many societies are divided, with distrust and divides exacerbated by media representations pitting different groups against one another. Acknowledging intersectional interrelationships, this collaborative paper considers one type of social distinction – generation – and focuses on how trust can be rebuilt across generations. To do this, we collate key insights from eight projects that shared space within a conference session foregrounding creative, intergenerational responses to the climate and related crises. Prompted by a set of reflective questions, presenters commented on the methodological resources that were co-developed in intergenerational research and action spaces. Most of the work outlined was carried out in the UK, situated in challenges that are at once particular to local contexts, and systematic of a wider malaise that requires intergenerational collaboration. Reflecting across the projects, we suggest fostering ongoing, empathetic dialogues across generations is key to addressing these challenges of the future, securing communities that are grounded as collaborative and culturally responsive, and resilient societies able to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of change.

Introduction

We are writing this paper at a time of climate crisis, named a ‘code red’ moment for humanity by United Nations General Secretary António Guterres, following the publication of Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis by Working Group 1 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)Footnote1 (United Nations Citation2021). Guterres’ language of urgency encapsulates the description by Head (Citation2016, 1) that ‘It feels as though we are hurtling down a hill without any brakes, through an unfamiliar landscape, to an uncertain destination’. Events since this description was written, exacerbated by the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, appear to have further increased the incline of the hill. However, there is still hope, with an increasingly loud call for action – much of it led by younger generations. Around the world, both in and out of the media gaze, young people – often with older generations – are engaged in a range of responses to the climate crisis (see Arya and Henn Citation2021a; Bowman Citation2020; Brown and Lock Citation2018; Halstead et al. Citation2021; Lock Citation2019; Citation2020; Trajber et al. Citation2019; Thew, Middlemiss, and Paavola Citation2020; Citation2022; Trott Citation2021; Verlie and Flynn Citation2022; Walker Citation2020). This is not the time to give up.

Young climate activists, part of a generation that ‘has been and is being socialised during a time of successive and overlapping crises’ (Pickard, Bowman, and Arja Citation2020, 255), have reinvigorated environmental debates, reframing the climate crisis as an issue of intergenerational (in)justice, wherein adults are seen to have broken an intergenerational contract by failing to adequately respond to the threat of climate change (Pickard, Bowman, and Arja Citation2022; Thew, Middlemiss, and Paavola Citation2020). Whilst there is much to be applauded and learned from young people’s activism, without an intergenerational response there is a risk that generational and mistrust divisions that were already considerable in many western democracies will widen further (see discussions by Pickard Citation2019; Verlie and Flynn Citation2022). As Greta Thunberg has said, ‘Climate activism is not a single generation’s job. It is humanity’s job’ (quoted by Verlie and Flynn Citation2022, 7).

Indeed, the ‘Grandparent and Elders’ group of Extinction Rebellion uses slogans such as ‘I rebel so I can look my grandchildren in the eye’ (Gillett Citation2019). Verlie and Flynn comment ‘this is no time for single heroes but instead collaborative, culturally responsive, locally situated practices of justice’ (Citation2022, 9), reminding us there are powerful imperatives for intergenerational collaboration. This is summed up in the term ‘mutual response-ability’, developed by Lock (Citation2019, Citation2020) drawing on the work of Haraway and Barad, to describe the need for ongoing negotiation and mutual enactment of responsibilities between all actors to address the climate crisis within ‘the on-going dynamism of the world’ (Lock Citation2020). Key to ideas of response-ability is that we act together, but do so with shifting and differential abilities or opportunities to enact change.

The crafting of this paper

Building on both academic and activist calls for collaborative responses, this multi-vocal paper, emerging from continuous dialogue with colleagues and collaborative knowledge (after Rose-Redwood et al. Citation2018), showcases some of the intergenerational efforts to resist what some cultural commentators have termed ‘the slow cancelling of the future’.Footnote2 In addition to the named authors, it is informed by many rich and varied conversations, some of which have spilled out into other publications (Bowman Citation2020; Bowman and Germaine Citation2022; Cutting and Peacock Citation2021; Hayes and Leather Citation2020, Citation2021; Jones et al. Citation2021; Lock Citation2020; Rudd Citation2021; Thew, Middlemiss, and Paavola Citation2022; Walker and Bowman Citation2022). The paper draws together informal dialogues that began in 2018 at the Royal Geographical Society (with Institute of British Geographers) (RGS-IBG) annual conference, feeding into a hot topic session at British Educational Research Association (BERA) 2019 annual conference (Hayes et al. Citation2019); the Hot topic session inspired an edited Blog series (Smith Citation2020) and then the dialogues continued into a conference session entitled ‘In it Together’ at the RGS-IBG 2021 hybrid conference (the session was originally planned for the 2020 Annual Conference and postponed because of the pandemic). ‘In it Together’ was organised by Authors 1–3 and included presentations by Authors 2–10 on the research projects outlined in , along with interactive response sessions where attendees were invited to post comments on a series of Padlet boards.Footnote3

Table 1. Summary of eight projects.

Following the rich dialogue generated through the RGS-IBG ‘In it Together’ 2021 session, Authors 1–3 asked the other presenters (Authors 4-10) to write a short reflection on the work they had presented, focusing on the spaces and methods that had been enabled, created or repurposed to allow dialogue, empathy and hope in intergenerational environmental action (for reflection prompts, see Appendix). In this way, we took up the ‘looping process’ developed and outlined by Trajber et al. (Citation2019, 91–92) to generate meta-analytical insights across research projects and action interventions with different methodologies and theoretical bases, with the aim to use the resulting dialogues and learning to promote intergenerational climate change transformations. Authors 1–3 read the eight reflections and, through discussion, agreed upon six common themes running across the reflections: space, empathy, dialogue, emotion, action and hope. This led to an interactive, looping process of dialogue: first, between Authors 1-3; secondly, between them and the other authors; thirdly, looping back to Authors 1–3 as they responded to authors 4-10, adding an additional ‘loop’ to the dialogic process (Trajber et al. Citation2019). This collaborative practical thematic work involved a back and forth process to develop findings – a dynamic and dialogic process that drew on the varied sources of data, with continual checking to ensure focus was maintained on practical action and on being ‘in it together’.

The looping process sits within our approach to writing this paper, which involved viewing materials and artefacts from the conference session using a praxis-based or ‘phronetic’ approach (Tracy Citation2013; Flyvbjerg, Landman, and Schram Citation2012). This meant that information (the call for papers for RGS sessions in 2020 and 2021; abstracts; presentations; delegate notes; post-session reflective commentaries; email conversations; meeting agenda and notes) was systematically gathered, analysed and communicated in a qualitative, practical way, which was focused on reflexivity, contextual knowledge, situated meanings and practical wisdom from each of the individual projects, without generalisations. The second loop – between Authors 1–3 and Authors 4–10 – was vital to ensure that we could draw overarching themes without losing the situated and practical knowledge infused into the individual reflections.

Most importantly for us, the emphasis of the ongoing dialogues that feed into this paper is on action to bring about change. As a collective of researchers and practitioners, we are convinced that building intergenerational solidarity in the face of multiple unfolding crises – among which the climate crisis is front and centre – is among the most urgent tasks facing humanity. Only by enabling transformation and enacting ‘mutual response-ability’ can we together resist the apparent inevitability of environmental decline (Common World Research Collective Citation2020; Lock Citation2020).

In the discussion that follows, we first introduce the research that authors presented in the conference session, which informed and inspired this paper. We then present the six dialogues that loop and weave between these projects to offer collaborative insights into the themes of space, empathy, hope, emotion, dialogue and action. This leads us to conclude, like Cripps (Citation2022, 16) there ‘is room for hope, even in this terror. But there is no room for passivity’. This paper is a call to action for us all.

Introducing the projects

We provide here a concise summary of the eight projects that form the core of this paper (). As is evident in the table, although each project was embedded in specific and very different local contexts and enacted across different geographical scales, the eight projects share key aims and characteristics. Each project is marked by a commitment to understand the ways people of different generations are experiencing, imagining, and responding to environmental loss, decline and vulnerability, and are acting together to respond to this. Moreover, the projects are action-oriented in nature, seeking not only to understand but to support and enable responses, with researchers positioned not as detached bystanders but as embedded in the lived experiences of, and emotional responses to, environmental loss, decline and vulnerability. As such, collectively they are committed to enacting mutual response-ability through supporting acts of resistance.

Fieldwork for half of the projects was impacted by responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a change in the intended methods from in-person to digital (what Arya and Henn Citation2021b, term ‘COVID-ised methodologies’). For projects taking place at the outset of the pandemic in 2020, online space was the only place where people could be together for a time. Dena commented that ‘in this challenging time although restricted to online interactions, I was able to build more compassionate and authentic relationships with my participants through a shared experience of this global social phenomenon’ (see also Arya and Henn, Citation2021b).

The necessary adaptation of methodologies presented challenges, for example, Catherine’s project was originally designed to take place in schools with groups of young people who already knew each other. Instead, to reduce the pressure on individual schools and meet the practical challenge of gathering small groups of young people at a time when learning was taking place in ‘bubbles’, the research went ahead online with a cohort drawn from various schools, most of whom were meeting for what might be the only time. Catherine commented in her reflection on this adaptation that ‘such ephemeral spaces are not ideal, but they are what we have to work with’. Amidst such challenges, however, moving research online often resulted in innovative and creative approaches (e.g. virtual walking stories, ‘activist smartphone doings’ (activist participatory research using smartphones) and using online resources rather than in-person visits), and broadened the scope for participation, beyond physical boundaries. As Ben/Chloe acknowledged in their reflection ‘ … we felt the project was a slower, gentler process because it was delivered online’.

When the authors presented on their work at the RGS-IBG 2021 session, we invited those present to comment on their own adaptations to research methodologies using Padlet boards, and various people commented that moving research online made it more inclusive, for example, allowing people in rural or marginal areas to take part when previously research activities would have been held in central urban locations. In some cases, taking research online allowed for novel intergenerational interactions – for example, Harriet wrote about how her digital avatar got stuck in Gathertown and young people had to ‘coach her out’. However, Zoom fatigue and digital poverty were also mentioned on the Padlet boards, reminding us we cannot ignore that participation in digital methods may be beyond reach for those with limited access to the necessary resources (e.g. smartphones, Wi-Fi). This needs to be considered in the planning stages of a project to address potential inequities.

Common themes and collaborative dialogues

Space

We begin with reflections on the spaces in which actions took place, as this was central to the questions that we asked co-authors to comment on (see Appendix). Nunn, writing about participatory arts-based research, comments that how comfortable co-researchers feel in the project space is among the key factors that can make or break possibilities for ‘supporting active, sustained engagement; facilitating genuine, equitable collaboration; generating meaningful, innovative art works and research data; and benefitting community co-researchers’ (Citation2022, 255).

It is notable that all of the projects that began pre-pandemic went to where protagonists were already, for example, Raichael’s work in a primary school, Sean’s work in a council youth centre, Harriet’s ethnographic study of participants at UN climate summits, and Stephen and Dena’s observations of climate activist meetings and actions. Sean comments that ‘A strong partnership between the researcher, youth council members and youth workers […] grew over many months through regular physical presence at meetings […] in the familiar setting where they would normally meet on a weekly basis’. Other co-authors, working with pandemic restrictions (Catherine, Ben/Chloe, Katie, and Dena), created online spaces where individuals from different generations could come together and engage in dialogue, exploration, and action.

Dena, whose research began in person but was moved online during the COVID-19 pandemic, describes a powerful moment of togetherness as she returned to in-person research at the Glasgow COP-26 summit: ‘I felt emboldened as part of a heterogeneous mix of people. What emerged from this experience, was a sense of intergenerational hope and solidarity which has been cultivated by young people’s environmental activism in recent years’ (see Pickard, Bowman and Arya Citation2020). The power of togetherness in public space also underpins Sean’s work with young people as they designed and enacted a litter picking project in a park, and Stephen’s reflections on Extinction Rebellion (XR)’s creation of ‘territories’ as places that were cared for and defended by activists of ‘noticeably different generations’ in a symbolic act of care for the planet.

The conceptualisation of and temporary naming of space as territory by activist groups such as XR is resonant of – and we argue can be reclaimed from – policing practice. As Stephen reflected, ‘The nature of policing, what and how territory was taken, kept, used and lost, how police defined territory and how boundaries were made and unmade had a critical role in how intergenerational solidarity developed during and after the action.’ Beyond high profile activism, the everyday reclaiming territory for the common, collective good can be a positive, hopeful action that recognises intergenerational community ownership of public spaces. Space, occupied and cultivated as territory, can become a key actor in the symbolic performance of togetherness, as Stephen comments, ‘the range and temporality of territory used allowed activists to model, in different places and temporalities, practices and processes that could be used to change the system with climate justice imaginaries and emotions of living in a changed world’.

Going to ‘where people are at’ allowed Harriet, Sean and Dena in particular to get ‘behind-the-scenes’ of ‘spectacular’ moments of public activism to better understand the everyday, non-spectacular moments and interactions that fuel such activism (Wood Citation2014). Harriet writes that ‘As little was known about young people’s lived experiences of participation in UN climate change conferences, I chose an ethnographic approach to inductively explore the topic and develop a deeper understanding of their experiences and perspectives’.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, co-authors developed creative methods to create ephemeral togetherness and temporarily overcome socio-spatial restrictions. For Stephen, developing a method around using smart phones within activist participatory research, which they called ‘activist smartphone doings’, afforded real time access to social media platforms used by XR activists (see also Rousell et al. Citation2021, on the interactions between on and offline spaces of activism). Katie and colleagues used online videos, the ArcGIS survey 123 appFootnote4 and artefacts to prompt place-based responses to coastal erosion, whilst Ben/Chloe set up a reading group, using climate fiction to transport readers to different times and places and allowing them in turn to reconsider the time and place of the present. This proved powerful, as meeting together over climate fiction created ‘a space for us as readers and researchers to explore emotions and ideas we might not usually explore’ (Balchin, quoted in Bowman et al. Citationforthcoming).

Empathy

Co-authors’ reflections offer insights into different contexts where concern for environments at risk was shared across protagonists of different generations. Researchers were not removed from these shared concerns as they facilitated, observed or performed emotionally responsive practices. These insights allow us to see empathy as an emotional response to the threat of losing a valued environment (or an object or species therein), and a commitment to acting together to protect what is valued, even if it is in individuals’ care for only a short amount of time, or the threat is imaginatively conceived rather than directly experienced.

Stephen experienced first-hand the emotions invested in the territory that quickly became valued by XR activists, commenting ‘the emotional intensity of actions quickly developed a sense of rootedness which made the loss of territory particularly powerful’. Likewise, Harriet was able to experience the emotional ups and downs of being an honorary youth delegate at UNFCCC summits through being there physically, joining in ‘sleeping on the floor in student houses, communal cooking and team-building games’. Dena and Sean’s commentaries offer further examples of empathy as embodied, breaking down the researcher/participant divide as researchers walked alongside young people at a COP26 protest march (Dena) and picked litter together with young people in their local park (Sean).

Katie and colleagues’ action research with a community living on a rapidly eroding coastline prompted creative responses from young people, including a powerful video.Footnote5 Against a backdrop of social division, Katie reflects the research allowed young people ‘to bring those voices, their emotions and their stories together so that at all stages of life within a community could feel empowered to take action on a situation that was happening to them’. The work also employed empathy mapping techniques as a cue to engender an appreciation of transgenerational perspectives.

Other projects offered insights into the work of the imagination to reach into distant locations or times not yet lived. Catherine’s project involved training migrant-background young people to interview older family members about how country of origin had been or could be affected by climate change. She commented on how young people’s interviews showed ‘the empathy that binds family relationships, both near and far’. Ben/Chloe’s intergenerational reading groups encouraged empathy between current and future generations through considering a range of alternative futures.

The commentaries show how empathy can have a multiplying effect. Raichael described school pupils’ strong reactions to learning of the effects of pesticides used in their school grounds on humans and other species. Their emotional responses grew as they held insects and observed their importance, becoming ‘worm and spider handlers’ and sometimes overcoming fears in the process. With the support of adult researchers, pupils expressed their concerns to the headteacher, who listened and committed to speak to the grounds management team. Raichael commented that the head teacher seemed to ‘appreciate […] the pupils’ need to protect those without a voice’, showing a chain of empathetic responses connecting the voiceless to the relatively more powerful.

Emotion

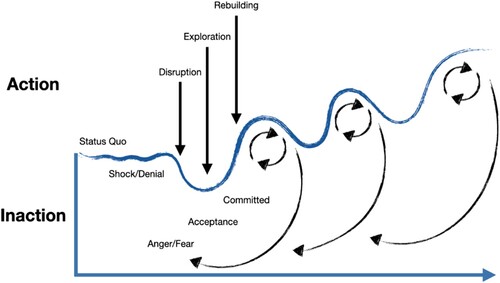

Emotions play a key role in the engagement and journey towards climate action. Jones et al. (Citation2021) highlight how becoming climate literate can be viewed as an emotional journey, drawing parallels with theories of loss and the grief model (Kübler-Ross 1969, cited in Jones et al. Citation2021; ), where those experiencing grief loop through a cycle of emotions – from denial to anger, to bargaining through to depression and, finally, acceptance.

Figure 1. Wave of change in a sea of emotion (Jones et al. Citation2021).

Interestingly, Bowman (Citation2020, 298) discussed a tendency for climate activism to be reported with regard to negative emotions only, whereas the emotions of joy associated with collective action is often overlooked. He writes that ‘protests were places of joy, dancing, excitement and positivity’. This relates to Stephen’s point on XR protests that are frequently joyful as they enact new worlds, and also aligns with Dena’s experiences of the march at COP26 in Glasgow, where participants reported positive emotions related to taking collective action, highlighting emotions centred on ‘an immense sense of intergenerational solidarity.’ Raichael discussed how pupils wanted to ‘speak truth to power’ but how the emotions they explored and felt, such as nervousness, passion, empathy and humour played a part in how they did this. Katie demonstrated how engagement with action can be driven by emotions through engaging young people in exploring intergenerational and community need, which enabled a sense of belonging and solidarity.

Emotional journeys can be individual or collective ones, with collective responses being a key primer in shaping emotions. For example, Halstead et al. (Citation2021) present an emotional journey from one youth’s perspective, highlighting how emotions centred in an individual through ecoanxiety can be positively impacted by taking collective action. They also discuss that ‘the turbidity of a youth activist’s emotional journey needs to be considered and handled delicately by those working with, and those closest to, youth activists’ (Halstead et al. Citation2021, p. 716) through ensuring that dialogues and knowledge exchange are sensitive to emotional needs and are considered fully in determining actions.

Raichael additionally made use of emotion to engage pupils in acquiring knowledge by ‘showing a film of insects smothering a car windscreen’ to highlight how insect numbers were plummeting. The emotional response to this went from engagement to action. Zhu and Thagard (Citation2002) argue ‘emotions are irrational and disruptive’ (p.19), they are ‘ … things that happen to us, out of our control, and involuntary. The passivity of emotion is usually in contrast to activity … ’ (p.21, author’s italics); whereas actions are things we do or initiate. However, the emotional need to take action can sometimes be overwhelming, as Katie experienced with pupils asking, ‘what can we do to help?’. Many of the projects additionally adopt the importance of agency through transferring or sharing knowledges. Theories of agency were developed by Bandura as part of his social cognitive theory, meaning ‘knowing how to act’ (Bandura Citation1982). Indeed, Catherine discussed how young people expressed frustrations about the limitations of their climate change education, which catalysed their action and related to a reimagining of how this education could be different. Their emotions, when shared with others, including peers, parents and researchers, gave them agency to move forward.

However, it was not just the emotions of the participants but also the researchers that the research process helped to elucidate. Harriet discussed emotion in regard to her feelings as the project progressed, transitioning from being ‘optimistic about the role of youth’ within the UN climate change negotiations at the start of the project, to becoming ‘increasingly critical as interactions I perceived as positive in the early stages failed to catalyse any notable changes over time’. Related to this, Stephen directly addressed the emotions of living in a changing world and argued how generational relations draw upon actual or potential conflicts and tensions between generations as a result of the real and perceived differences in power and resources, which brings the need for dialogue.

Dialogue

In dictionaries, dialogue may be defined as a written or spoken conversational exchange or a discussion between two or more people (e.g. Merriam-Webster 2022), deriving from the Greek roots dia- (‘through’ or ‘across’) and -logue (‘discourse’ or ‘talk’). To be effective, dialogue ‘ … presupposes the capacity to listen to, and engage with, one’s interlocutors’ (Rose-Redwood et al. Citation2018, 110). It is ‘ … an embodied practice, replete with its own power asymmetries and social hierarchies of class, race, gender, sexuality, age, (dis)ability, language, and geographical location’ (Underhill-Sem 2017, cited in Rose-Redwood et al., 112). Participatory methods used in the eight studies recognise and attempt to address these asymmetries and hierarchies, and researchers/authors have been ‘ … reflective of, and attentive to, their own situatedness’ (Ibid.).

In this paper, dialogues have ‘looped’ and circulated (after Trajber et al. Citation2019) within/across generations, as well as within/across a range of spaces, crossing continents, geo-spatial, temporal, ephemeral spaces. Dialogues have also looped and circulated within/across the process of writing this paper, the eight research projects and beyond in public and media forums. In online, ephemeral spaces, dialogue was shaped and constrained by factors such as time differences, quality of internet connection, whether participants felt confident in turning on cameras and who turned up. Catherine’s experiences led her to question how training young people to interview parents for research may differ from other forms of more organic, everyday dialogue, and what was gained by making the process more structured. She highlights that parents and children saw each other in a different way, questioning, exploring experiences and perspectives through dialogue. As one YP reflected on being part of this dialogic process, ‘ … it really does challenge your thinking and makes you a lot more aware’. This is a specific example of how research can support and complement already existing ways that different generations are learning from/with each other, leading to new understandings of being ‘in it together’.

Stephen also made use of ephemeral online spaces for intergenerational dialogue, using smart phones with real time access to social media platforms within activist participatory research. He found that using activist smartphone doings captured and shaped interactions, demonstrating how intergenerational solidarity developed with each generation’s contribution to telling the truth about climate change and engendering activism demanding urgent action. In another creative use of digital methods for dialogue, Ben/Chloe facilitated online reading groups, which felt slow and gentle in pace, allowing space and time for discussions to wander off the topic of the book to real world racism, sexism and climate injustice. In a similar vein, Dena reflected that through open dialogue about the impact of the pandemic and its related restrictions on well-being and mental health, they were able to develop more authentic bonds, which translated into a more compassionate research relationship. This resonates with Sean’s reflections that dialogue about, and empathy for local places can open a space for intergenerational action, enabling young citizens to design and deliver creative responses to environmental issues in their city (Peacock, Puussaar, and Crivellaro Citation2020). Similarly, Katie’s conversations in schools revealed the young people she was talking with did not understand climate change, seeing it as something happening to others, not them. Through walking stories, intergenerational community interviews and fieldwork, a range of powerful short stories, poems, films and photographs were created (Parsons, Halstead, and Jones Citation2021).

Harriet identified how her role as participant observer facilitated reciprocity as she could share knowledge on how complex processes operate at UNFCCC conferences, though she was conscious of the inherent power differential in this, careful not to influence the youth participants’ decisions. Raichael took this further, with ‘speaking truth to power’, a pedagogical method whereby pupils take a specific matter of concern and rehearse intergenerational conversations. Through this dialogic process, they discovered what key messages they wanted to articulate and decided whether to speak with passion, empathy, humour, or through sharing scientific knowledge. Teachers engaged, encouraging dialogue and appearing to appreciate pupils’ need to protect those without a voice whilst supporting them in challenging accepted practices (see also ‘empathy’). Of course, there is the risk that less receptive adults might not be so understanding, but being able to discuss complex issues with adults is a valuable skill that enables intergenerational education and dialogue to take place on a more equal footing benefiting everyone.

What the projects have in common is that they all offered opportunities for dialogue, with a focus on developing/sharing understanding of own and others’ perspectives and experiences, in a way that encourages action.

Action

Climate action builds from climate literacy, where space, empathy, hope, and emotion embedded within/engendered through dialogue, create an environment of agency so an individual or group can take action. Indeed, Raichael highlights how intergenerational connections underpin collective action, and how different generations take different actions and are on different journeys. Being together was a key theme of taking action, with connectiveness and dialogue being vital in change making and re-imagining climate futures. Elsewhere, Lock (Citation2020, 224, drawing on Barad 2012 and Haraway 2016) highlights ‘the importance of our creative imaginings becoming methodologies that can also enact the building of the new world as it is being imagined … through processes of mutual response-ability’ (author’s italics).

Stephen’s research centres on that mutual response-ability and he mentions the generational spectres of contemporary activism and action, and how it shapes not only who is involved but how they are involved, what their activism looks like and the impact their activism has. This leads him to reflect that ‘intergenerational solidarity’ can be built through ‘taking action together, looking out for each other and living the resulting experiences together.’ Bringing people together was also an outcome of Katie’s work where an engaged class of pupils were able to mobilise a community in taking action through capturing their stories – taking ownership of the change and acting together to address it as a community. Catherine additionally highlighted how young people taking part in research discussions on climate change education and actions recognised generations must act together, act urgently, and also learn from one another.

Taking action can become overwhelming when the blame is often laid at the individual’s door rather than it needing to be a systemic shift from those in power, industry and wider society. This pressure often leads to individuals becoming disengaged and inactive. During our RGS 2021 conference session, discussions began to arise on how young activists are now fearful of using the word ‘activist’ in fear of negative impacts on future employment (Ojala et al. Citation2021). However, Mwaura (Citation2018) highlights the opposite effect in Kenya, with engagement and environmental activism increasing opportunities to build career profiles. Engaging in activism can have place and space based implications, which may lead adult gatekeepers to be wary of young people getting involved in activism. However, not allowing young people to take part in activism can prevent individuals from becoming part of the solution and contribute to feeling powerless. Sean demonstrates how action can ease feelings of powerlessness by reporting on how the group he supported were able to narrow down what action they felt was realistic and focus on instrumental, meaningful and local change. A quote from one youth council member sums this up beautifully: ‘I can’t fix all of the plastic in the ocean, but I sure as can fix all the plastic in the park.’ They commented on how the action they took demonstrated change is possible and provided ‘optimism for a better future’.

Hope

Hope is different to optimism and does not rely on optimistic emotions. It is a state where the future is seen as open and enabling, rather than predetermined. Like Head (Citation2016, 11), in this paper we find hope in practices, embodied within dialogue and action: ‘Hope savours the life and world we have, not the world as we wish it to be (…) Hope can also be found in unexpected places’, as in the eight projects discussed herein. A geography of hope enables us to ‘develop a sense of agency in relation to both mitigation and adaptation’ to climate change (Hicks Citation2018, 78). This can help with preparing for futures that are very different to today, yesterday, what came before. We need imagination and determination not to lose heart, or give in to despair, and instead take action. A litter pick such as the one supported by Sean, may not appear transformative, but this local action inspired other environmental activism, and helped displace pessimism among some group members in favour of optimism for a better future. This was accompanied by a pragmatic, realistic approach, demonstrated in their actions (discussed under ‘action’).

Sean’s approach was based on acknowledging the importance of recognising young people’s unique lived experiences and local knowledge in climate change decision-making – and in the here and now. This is often overlooked as young people are framed as representatives of (and only in) the future rather than as critical actors in the present, highlighting the importance of hope in/for the present as well as future-oriented (see also Peacock, Anderson, and Crivellaro Citation2018). As Katie found, there needs to be a balance between learning to develop understanding that climate change is ‘not something that is happening far away but right on our doorstep’, with empowering and integrating young people into the wider community, to work together to identify solutions and actions.

In her reflective commentary, Harriet described becoming less optimistic about the ability of youth to influence the UN climate negotiations during her longitudinal study. Her findings reinforced a need for increased interaction and collaboration between generations and for diversity to be championed within climate activism (see Thew Citation2018; Thew, Middlemiss, and Paavola Citation2021). Similarly, Stephen explained that contemporary environmental activism has young people and older people taking action together, using imagination to take creative actions that draw upon and across generations, highlighting our past and our potential futures as a result. This was experienced directly by Dena who, as referenced above in ‘space’, felt emboldened by the intergenerational hope and solidarity they experienced when taking part in a climate march. As well as emerging spontaneously, hope was also intrinsic to research designs. For example, Catherine’s research was about using intergenerational interviews led by young people to imagine how climate change education could be different, whilst Dena emphasised in her research that shared lived experiences were key to building trusting relationships.

Ben/Chloe used climate fiction as an imaginative resource for young people to explore their own climate imaginaries within a reading group. Sometimes participants contrasted the futures in the books to futures that the real world might face or might hope for. Bowman and Germaine have written elsewhere that young people’s visions for the future differ from those ‘that tend to be offered through traditional modes of civic education’ (Citation2022, 71) and that creative methods, like reading groups, can help nurture these visions. Hope for changing practice in school was a driving force in Raichael’s research. Supporting the young researchers to share their knowledge with teaching staff – including the head teacher – resulted in their confidence blossoming, enabling them to make the most of other opportunities to inform staff and pupils about environmental issues.

Hope may be ‘messy, fraught and uncertain’ (Head Citation2016, 11) but it is integral to all eight of the projects that inform this paper, and is a powerful catalyst for action, as we move onto discuss in closing this paper.

Discussion and conclusions

Reflecting on the School Strikes for Climate Movement, Verlie and Flynn reflect that ‘this is no time for single heroes but instead collaborative, culturally responsive, locally situated practices of justice’ (Citation2022, 9). In this paper, we have shown how, against a backdrop of widening societal divisions, responding to the climate crisis calls for and creates opportunities for generations to work together.

This paper showcases some of the many ways in which individuals across generations are resisting the inevitability of climate change, the unfolding of everything we value. It is striking that across eight very different projects, hope and resistance were generated through a shared sense of being in the world together, and a commitment to collectively resist the loss and decline of valued aspects of the environment as lived and imagined into the future. The process has resulted in shared learning, shared experiences and a collective journey between the authors and, through the looping between projects (following Trajber et al. Citation2019), has created a new intersectional lens that has allowed new learnings to unfold.

It is striking that from eight different projects, six common themes emerged through our reading and discussing of the reflections. We argue that these common themes – space, empathy, dialogue, emotion, action and hope – are necessary components to build intergenerational responses to the climate crisis, although we caution that each ‘component’ will have different meanings and applications according to context. Together, the themes offer insights into how reclaiming territory in a positive, empathetic way through building relationships in/on/with emotional attachments to place enables collaborative, intergenerational dialogues and actions. We hope that this paper will add weight to an emerging literature responding to the climate crisis that is collaboratively authored and bridges academic and non-academic and generational boundaries (for example, Halstead et al. Citation2021; K. Parsons Citation2021; L. Parsons Citation2021; Walker et al. Citation2022).

Hope is key to sustaining collective resistance. Hicks (Citation2018) discusses how a sense of agency can be nurtured through learning, sharing and acting together. As highlighted above, hope does not rely on optimistic emotions, but allows reimaginations of a future that is seen as open and enabling, rather than predetermined. A community has, and is, more powerful when working together for the benefit of all. This paper brings together eight projects that exemplify this approach; but there are and will be many more collaborative acts of resistance such as these as humankind wakes up to the realities of living within a climate of uncertainty.

As Bowman (Citation2020, 296) reflects, ‘A new world is imminent: that is to say, a new world sculpted by anthropogenic changes to the environment, and perhaps restructured by social, political, economic and cultural reform’. We contend that this ‘new world’, already characterised by interdependence, must be characterised by togetherness, as individual action to address the climate crisis as both lived and imagined is not enough. Whilst in the spirit of mutual response-ability we all have a role to play, we also recognise a role for researchers and practitioners committed to climate justice (see Cripps Citation2022) to support further research and collaborative undertakings with key groups, amongst these, teachers, parents and grandparents.

As researchers and individuals deeply concerned with the legacies of ecological decline, we are keen to highlight the (albeit modest) role that researchers and other supportive adults can play in supporting intergenerational action to resist and to bring hope to where it has been lost and in encouraging the wider public that we can all do something. Lock (Citation2020), in dialogue with Bowman (Citation2020), envisages this role as ‘generating intergenerational opportunities to help all our collective imaginings come into being’ (Lock Citation2020, 226).Footnote6 Also important is the documentation of collaborative dialogues and resulting actions that researchers can facilitate – although not always exclusively. In uncertain times, we recognise the importance of being adaptive, of shifting to new ways of being, new ways of conducting research, with perhaps one effect of the pandemic being the generation of new research methods and methodological resilience. Research and action must focus on the here and now, as well as the future and the importance of ‘reciprocally responsive’ intergenerational action (Brown and Lock Citation2020).

Action research projects presented in this paper bear witness to the (sometimes micro-scale) transformations taking place as people gather to discuss (Hayes et al. Citation2019; Walker Citation2020), imagine differently (Ben/Chloe, Stephen, Raichael), plan and deliver action for change (Stephen), engage in emotional labour together (Harriet), collectively experience the changing landscape (Katie), temporarily remake spaces to perform the need for change together (Stephen), or simply move through/inhabit space together (Dena). As Sean reflects, ‘the precise benefits of bringing environmental transformation in reach to young people are difficult to measure, but the value is plain to see.’

Key to all of these actions, we contend, is the doing of these things together. Being together allows for shared learning and shared ‘world building’ as researchers and other adult stakeholders often have access to resources that can facilitate, and put into action, collective ideas and creative methodologies (Bowman Citation2020). We have experienced the value of being together through the crafting of this paper, wherein the dialogue engendered by the looping process and the phronetic approach has enabled us to produce action-oriented reflections that we may not have seen without these collective dialogues. Beyond ‘projects’, this is about shared being and shared emotion as we engage in making our present worlds more resemblant of the futures we want. As we collectively mourn, act and hope (Head Citation2016), we build our shared humanity and remind ourselves that whatever our place within the multiple crises, joys and possibilities that make the world what it is at this particular point in time, this is a shared world and we are indeed all in it together.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 http://epiloguemag.com/2020/08/the-future-is-cancelled/ This phrase has been seen at climate strikes and strikes led by university lecturers.

3 Padlet is a free online tool described as an online notice board that allows people to post comments, questions, and resources in one place that is easily accessed, see https://en-gb.padlet.com/.

4 ArcGIS 123 is an app for creating, sharing, and analysing surveys, that collects data via web or mobile devices, see https://www.esriuk.com/en-gb/arcgis/products/survey123/overview.

5 Available to view at https://youtu.be/dV6z0LKobfE.

6 Original quote by Bowman (Citation2020, 296): Climate action is more than protest: it is also a world-building project, and creative methodologies can aid researchers and young climate activists as we imagine, together, worlds of the future.

References

- Arya, D., and M. Henn. 2021a. “The Impact of Economic Inequality and Educational Background in Shaping How Non-Activist “Standby” Youth in London Experience Environmental Politics.” Educational Review (online first), doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.2007051.

- Arya, D., and M. Henn. 2021b. “COVID-ized Ethnography: Challenges and Opportunities for Young Environmental Activists and Researchers.” Societies 11: 58. doi:10.3390/soc11020058.

- Bandura, A. 1982. “Self-efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency.” American Psychologist 37: 122–147.

- Bowman, B. 2020. “Imagining Future Worlds Alongside Young Climate Activists: A New Framework for Research.” Fennia - International Journal of Geography 197 (2): 295–305. doi:10.11143/fennia.85151.

- Bowman, B., and C. Germaine. 2022. “Sustaining the Old World or Imagining a New One? The Transformative Literacies of the Climate Strikes.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38 (1): 70–84.

- Bowman, B., C. Germaine, C. Balchin, P. Kishinani, I. Lowther, N. Madden, A. Peilober-Richardson, and M. Smith. Forthcoming. “The Climate Imaginary: Using Climate Fiction Make Sense of the Climate Crisis.” In The Existential Toolkit for Climate Educators, edited by J. Atkinson, and S. J. Ray. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, S. A., and R. Lock. 2020. “Enhancing Intergenerational Communication Around Climate Change.” In Handbook of Climate Change Communication: Vol. 3: Climate Change Management, edited by W. Leal Filho, et al., 384–398. Cham: Springer.

- Common Worlds Research Collective. 2020. “Learning to Become with the World: Education for Future Survival.” Paper Commissioned for the UNESCO Futures of Education report. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374032?posInSet=1&queryId=N-EXPLORE-08167fcf-84e7-428b-af6e-633f41d3b606.

- Cripps, E. 2022. What Climate Justice Means and why we Should Care. London: Bloomsbury.

- Cutting, K., and S. Peacock. 2021. “Making Sense of ‘Slippages’: Re-Evaluating Ethics for Digital Research with Children and Young People.” Children’s Geographies 0: 1–13. doi:10.1080/14733285.2021.1906404.

- Flyvbjerg, B., T. Landman, and S. Schram, eds. 2012. Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gillett, F. 2019. “I Rebel So I Can Look My Grandchildren in the Eye.” The Guardian, September 15. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-50063449.

- Halstead, F., L. R. Parsons, A. Dunhill, and K. Parsons. 2021. “A Journey of Emotions from a Young Environmental Activist.” Area 53: 708–717. doi:10.1111/area.12745.

- Hayes, T. A., and M. Leather. 2020. “Shifting Perspectives on Nature through Pedagogical Practices [webinar].” BERA, October 28. https://www.bera.ac.uk/media/shifting-perspectives-onnature-through-pedagogical-practices.

- Hayes, T. A., and M. Leather, eds. 2021. “The Serious Side of Nature, Outdoor Learning and Play: International Perspectives.” In Research Intelligence Special Issue, 10–27. London: British Educational Research Association.

- Hayes, T. A., M. Leather, T. Gray, and J. Quay. 2019. “Hot Topic Session: #fridaysforfuture: The Serious Side of Nature, Outdoor Learning and Play.” BERA Annual Conference, Manchester, September 10–12.

- Head, L. 2016. Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene: Re-Conceptualising Human–Nature Relations. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hicks, D. 2018. “Why we Still Need a Geography of Hope.” Geography 103 (2): 78–85.

- Jones, L., F. Halstead, K. J. Parsons, H. Le, L. T. H. Bui, C. R. Hackney, and D. R. Parsons. 2021. “2020-Vision: Understanding Climate (in)Action Through the Emotional Lens of Loss.” Journal of the British Academy 9 (s5): 29–68.

- Lock, R. 2019. “From Academia to Response-Ability.” In Climate Change and the Role of Education: Climate Change Management, edited by W. Leal Filho, and S. L. Hemstock, 349–362. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-32898-6_19.

- Lock, R. 2020. “Beyond Imagining: Enacting Intergenerational Response-Ability as World-Building – Commentary to Bowman.” Fennia – International Journal of Geography 198 (1–2): 223–226. doi:10.11143/fennia.98008.

- Mwaura, G. M. 2018. “‘Professional Students Do Not Play Politics’: How Kenyan Students Professionalize Environmental Activism and Produce Neoliberal Subjectivities.” In Young People Re-Generating Politics in Times of Crises, edited by Sarah Pickard, and Judith Bessant, 59–76. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nunn, C. 2022. “The Participatory Arts-Based Research Project as an Exceptional Sphere of Belonging.” Qualitative Research 22 (2): 251–268.

- Ojala, M., A. Cunsolo, C. Ogunbode, and J. Middleton. 2021. “Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46: 35–58.

- Parsons, K. 2021a. “The Growth of Youth Activism: Why We Should Listen to Young People.” In ‘The Serious Side of Nature, Outdoor Learning & Play’: International Perspectives. BERA Research Intelligence, T. A. Hayes and M. Leather, issue 147, 23–24.

- Parsons, L. 2021b. “Young People’s Challenge: Will You Help Us?” In ‘The Serious Side of Nature, Outdoor Learning & Play’: International Perspectives. BERA Research Intelligence, T.A. Hayes and M. Leather, issue 147, p. 24.

- Parsons, K., F. Halstead, and L. Jones. 2021. Intergenerational Stories of Erosion and Coastal community Understanding of REsilience ‘INSECURE’, EGU General Assembly 2021, online, 19–30 Apr 2021, EGU21-9478. doi:10.5194/egusphere-egu21-9478.

- Peacock, S., R. Anderson, and C. Crivellaro. 2018. “Streets for People: Engaging Children in Placemaking Through a Socio-Technical Process.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ‘18, 327:1–327:14. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173901.

- Peacock, S., A. Puussaar, and C. Crivellaro. 2020. “Sensing our Streets: Involving Children in Making People-Centred Smart Cities.” In The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking, edited by Cara Courage, Tom Borrup, Maria Rosario Jackson, Kylie Legge, Anita Mckeown, Louise Platt, and Jason Schupbach, 130–147. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pickard, S. 2019. Politics, Protest and Young People: Political Participation and Dissent in 21st Century Britain. London: Palgrave.

- Pickard, S., B. Bowman, and D. Arja. 2020. “We are Radical in our Kindness”: The Political Socialisation, Motivations, Demands and Protest Actions of Young Environmental Activists in Britain.” Youth and Globalisation 2: 251–280.

- Rose-Redwood, R., R. Kitchin, L. Rickards, U. Rossi, A. Datta, and J. Crampton. 2018. “The Possibilities and Limits to Dialogue.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (2): 109–123.

- Rousell, D., T. Wijesinghe, A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, and M. Osborn. 2021. “Digital Media, Political Affect, and a Youth to Come: Rethinking Climate Change Education Through Deleuzian Dramatisation.” Educational Review, online first. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00131911.2021.1965959.

- Rudd, J. 2021. “‘We’re All in this Together’ – Solving Climate Change Across the Disciplines by Taking a STEAM Approach to Climate Education.” SSR, December 2021, 103(383) 42–47. https://www.ase.org.uk/resources/school-science-review/issue-383/were-all-in-together-%E2%80%93-solving-climate-change-across.

- Smith, K., ed. 2020. “Education for Our Planet and Our Future.” BERA Blog series, 23 January. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog-series/education-for-our-planet-and-our-future.

- Thew, H. 2018. “Youth Participation and Agency in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 18 (3): 369–389.

- Thew, H., L. Middlemiss, and J. Paavola. 2020. “Youth is not a Political Position”: Exploring Justice Claims-Making in the UN Climate Change Negotiations.” Global Environmental Change 61: 102036.

- Thew, H., L. Middlemiss, and J. Paavola. 2021. “Does Youth Participation Increase the Democratic Legitimacy of UNFCCC-Orchestrated Global Climate Change Governance?” Environmental Politics 30 (6): 873–894.

- Thew, H., L. Middlemiss, and J. Paavola. 2022. “You Need a Month’s Holiday Just to Get Over It!” Exploring Young People’s Lived Experiences of the UN Climate Change Negotiations.” Sustainability 14 (7): 4259.

- Tracy, S. J. 2013. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- Trajber, R., C. Walker, P. Kraftl, V. Marchezini, D. Olivato, S. Hadfield-Hill, C. Zara, and S. Monteiro. 2019. “Promoting Transformation with Young People: Looping Action Research, Citizen Science and Nexus Approaches to Climate Change in the Paraíba Watershed, Brazil.” Action Research 17 (1): 87–107.

- Trott, C. D. 2021. “What Difference Does it Make? Exploring the Transformative Potential of Everyday Climate Crisis Activism by Children and Youth.” Children's Geographies, 19(3), 300–308.

- UN (United Nations). 2021. Secretary-General Calls Latest IPCC Climate Report ‘Code Red for Humanity’, Stressing ‘Irrefutable’ Evidence of Human Influence. UN Press Release, 09/08/21. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20847.doc.htm.

- Verlie, B., and A. Flynn. 2022. “School Strike for Climate: A Reckoning for Education.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1017/aee.2022.5.

- Walker, C. 2020. “Uneven Solidarity: The School Strikes for Climate in Global and Intergenerational Perspective.” Sustainable Earth. https://sustainableearth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42055-020-00024-3.

- Walker, C., and B. Bowman. 2022. Young People and Climate Activism. Oxford Bibliographies.

- Walker, C., Rackley, K. M., Summer, M., Thompson, N., and Young Researchers. 2022. “Young People at a Crossroads: Stories of Climate Education, Action and Adaptation from Around the World.” Published online at https://www.sci.manchester.ac.uk/research/projects/young-people-at-a-crossroads/.

- Wood, B. E. 2014. “Researching the Everyday: Young People's Experiences and Expressions of Citizenship.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 27 (2): 214–232.

- Zhu, J., and P. Thagard. 2002. “Emotion and Action.” Philosophical Psychology 15 (1): 19–36.

Appendix

Appendix. Guidance given to contributors for their reflective pieces

Please give details of the following for a summary table showing key characteristics of the projects discussed in the paper:

name of project

timeframe of project

age of individuals involved

overall aims of project

methods intended and methods used (if different).

Following these details, we invite you to write around 400 words reflecting on the following questions:

Briefly outline the work/research/encounters you were involved in, fleshing out the information presented in the table.

Was the work designed as an intervention, an experiment or an observation (or something else)? How was it designed and how did it evolve?

What key relationships framed the work, how were they established and how did they evolve through the work/research/encounters?

How did the spaces (e.g. physical qualities, institutional regulations) in which the work/research/encounters took place shape what emerged?

What are the main learning points from the work you presented in terms of building dialogue, empathy and hope across generations in the face of deep-rooted societal and ecological crises?