ABSTRACT

We question the relative absence of babies and toddlers in geographies of children and youth, while also acknowledging what may be signs of a new subfield in the making. We argue that there is an exciting opportunity here because babies and toddlers are at the crux of what it is to be human, raising potent questions about exactly ‘what kinds of human’ are they? We argue that babies are the ultimate non-representational, in certain respects barely-human, subjects who express their agencies in non-verbal ways. Toddlers too are disruptive to the socio-spatial order, and their disruption exposes the normative expectations of behaviour in place. Close attention to these tiny humans and their ‘micro-geographies’ provides insight into ‘lines of flight’ that configure our studies, and maybe even our worlds, otherwise.

Introduction

It is surprising to us that, several years after an initial conversation (circa 2010) about a mutual interest in babies and toddlersFootnote1 as fascinating subjects highlighting both the range of human agency and the limits of what we consider to be human, these tiny humans – these very young childrenFootnote2 – remain peripheral to academic geography and, more problematically, to geographies of children and youth. This speculative paper returns to that conversation and, offering a minor survey of what work has since been undertaken in this respect, reflects from different angles on the matter of ‘what kind of human?’ is at issue here and why very young children sit somewhat awkwardly in the landscape of human geography inquiry.

Lying in the background, albeit unanswerable in the limited scope of what follows, are the interlinked questions ‘when does a foetus become a baby become a toddler become a child, and at what point does the human emerge?’ These questions are freighted with heavy ethical, political and religious significance, immediately resonating with speculations about both the relational spatialities of ‘life’ in the wombFootnote3 and the conflictual geographies of abortion legislation, policies, mobilities and practices.Footnote4 More to the foreground for us here, then, is the problematic of why living babies and toddlers often strike as very strange sorts of humans: undeniably regarded the world over as human and yet, in so many ways, displaying characteristics that, if shown by other cohorts of humanity, might lead them to be dismissed as ‘barely human’, ‘less-than-human’ (Philo Citation2017) or at the ‘limits’ of being human precisely because of their inability to ‘self-represent’ as human (and where the calm-spoken word is replaced by the gurgle, the cry or the scream [Rosen Citation2015]).

The above-mentioned conversation was sparked when a paper published by Louise resonated with Chris who had taught an undergraduate lecture for some years in the early-2000s about babies and toddlers. In her paper, Louise Holt (Citation2013, Citation2017) argued for ‘infant geographies’ to be taken seriously, and – drawing upon Butler’s ideas about performance and identity – she sought to conceptualise how ‘everyday material geographies’ are inextricably implicated in how young children, locked in a web of ‘infant-other relations’ and human interdependencies, tend to settle into established patterns of subject formation replete with implications for the creation and extension of social power. Recognising that infants are largely ‘prediscursive’ and often able, however unwittingly, to introduce ‘friction’ into the system (of their ‘subjection’), she clarifies how they are nonetheless cajoled into becoming (and performing) the ‘fiction’ of the ‘autonomous, thinking, rational human subject’ (Holt Citation2013, 645 [abstract]). Louise’s paper then moves to ‘deconstruct’ this fiction, but in a manner that remains, almost in spite of its ambition, still somewhat remote from the messy, scrumpled, dribbly realities of baby and toddler existence.

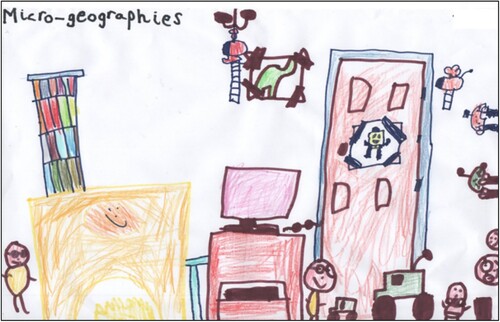

In his lecture, meanwhile, in a playful fashion but with underlying serious intent, Chris reflected on the many curious attributes of babies and toddlers that, if exhibited by other humans, would lead them to be regarded as ‘outsiders’ departing significantly from the usually accepted conventions of what comprises a capable, responsible, autonomous, self-determining ‘rational’ human subject (). His claim was that these tiny humans appear as ‘barely human’, almost inhuman, a depiction that has of course been central to the deeply problematic othering of so many human groupings, tellingly captured in Agamben’s account of ‘bare life’ disqualified from the status of self-possessed political being (bios) and hence to be excluded – delegitimated – from the normal spaces of human thought-and-action (Agamben Citation1998). One central facet of the otherness routinely displayed by these tiny barely-humans, as noted in the slide, is also their relative inability to speak, to communicate verbally, to represent themselves: hence their status as ‘non-representational’ subjects. Once reframed in these ways, and given core conceptual interests of human geography, including in geographies of children and youth, the absence of such tiny humans from recent geographical purview is all the more surprising.

Figure 1. Slide from Chris’s lecture (Philo Citationn.d.).

This absence is hardly total, however, and we have to acknowledge that Children’s Geographies has seen growing indications that babies and toddlers do indeed merit concerted attention from geographers of children and youth. There are contributions that explore the admixtures of mothers, very young children and the ‘vibrant materialities’ of breast-feeding equipment (Newell Citation2013), slings (Whittle Citation2021, Citation2019) and prams – two authors speak of the ‘mother–child-pram assemblage’ (Clement and Waitt Citation2018)Footnote5 – that constitute such distinctive inhabitations of space in which babies and toddlers, including their often-unpredictable embodiments, are so palpable. A related study notes how parents, specifically mothers, address and manage children’s body weight, frequently through lenses coloured by their experiences with ‘pre-school-aged children’ (MacAllister Citation2016). There are works that consider the agency, perceptions and balances between play and risk associated with two-year-olds in domestic home-spaces (Hancock and Gillen Citation2007), a focus given inflections close to what follows below in the compelling study of home-based ‘babies’ everyday space-making’ by Orrmalm (Citation2020). Then there are the pieces that consider toddlers – as social-geographical agents – in nurseries (Gallacher Citation2005; Blaisdell Citation2019) or other pre-school spaces such as playgrounds (Dyment and O’Connell Citation2013),Footnote6 as well as exploring how very young children may envisage (even photograph) public spaces (Templeton Citation2020). These writings differ in the exact concepts, methods and substantive thematics that they engage, and they also pivot on differing models of how the creative participation of tiny humans might be meaningfully and ethically enlisted (Blaisdell Citation2019; Hultgren and Johansson Citation2019). Together, though, they comprise a crucial body of inquiry whose insights complement our own broader-brush strokes in what follows.

Taking Chris’ lecture as a complement to Louise’s paper, and cognisant of the contributions just cited, duly leads us to the speculations that are the spine of this Children’s Geographies ‘viewpoint’ piece.Footnote7 Why, in a subdiscipline concerned with the agency of children, are babies and toddlers largely absent, not included in the pantheon of differences, more or less marked, within the overall universe of ‘the human’ reckoned worthy of special attention and address within the discipline (human geography) or its subdisciplines and subfields (geographies of children and youth included)? Why are the experiences, perceptions, capacities for agency, structural controls and enablers of their lives, and multiple dimensions of space and place central to their worlds, not more fully to the fore? These tiny humans occupy the boundary between the human and the non-human: they become subjective beings, recognisable as humans (as people) in a social world in ways that are embodied and later played out as ‘natural’, but which still hold resistance and friction that risks undoing that neat subjectification as ‘human’ (Butler Citation1997; Bourdieu and Thompson Citation1991). Arguably, therefore, babies and toddlers tell us something more about what it means to be human in a lively and agentic world.

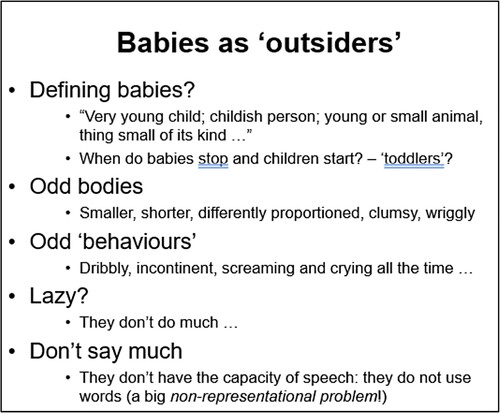

In his lecture, Chris proceeded from his opening claims about the strange othernesses of babies and toddlers to consider what he termed the ‘micro-geographies’ of these tiny humans, using as a cue a drawing done by his just-out-of-toddlerdom son that, when a little older still and under guidance, he was persuaded to entitle with this phrase (). The picture portrays a downstairs room where he spent much of his early years, a space effectively imposed on him by his parents, but one that he also personalised materially – as well as imagined – for himself in various ways. Hence, the adult possessions or objects with adult purpose – the fireplace, television and (ancient) video recorder, CD rack, lights and waste bin – are juxtaposed with both small human figures, toddlers and one baby, and a variety of toys (lorries, remote-controlled helicopters) and children’s drawings (a dinosaur, Spongebob Squarepants). Tellingly, the figures are indeed dwarfed by the adult-sized presences in the room, notably the door. It is perhaps a baby-and-toddler version of the children’s toy-filled worlds so wonderfully evoked by the likes of Horton (Citation2005), or indeed the ‘space-making’ by babies such as Wilma so carefully mapped and interpreted by Orrmalm (Citation2020). In what follows, we will explore, more or less overtly, something of these micro-geographies, while also wondering about the non-representational and barely-human dimensions of the diverse space-inhabitations under consideration.

Babies and toddlers ‘out of place’?

In many societies of the Global North babies and toddlers are reckoned ‘out of place’ in many adult-focused spaces: from mother-baby nexuses being excluded from specific spaces to the all-too-familiar looks and glances towards noisy toddlers in public spaces, particularly when they are angry and testing the boundaries. Breastfeeding in public – conjoining sexist, anti-infant and a wider swirl of moralising discomforts about bodily exposures and fluids – is arguably the signature issue here, as sensitively investigated through geographical lenses by Boyer (e.g. Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; also Newell Citation2013). Clearly, within many contexts within the Global North, such exclusions have changed in light of feminist endeavours to encourage breastfeeding in public, for instance, but still there are many places where babies and toddlers are not expected – the pub, the workplace, the commuter train – or accommodated for. The experiences of both baby and toddler segregation from everyday life and specialist baby and toddler spaces – toddler groups, baby signing, baby massage, the home, the nursery in the home, the playroom for the privileged, the daycare centre/nursery – remains a notable feature of Global North societies. It is sometimes claimed that within most Global South societies babies and infants are more co-present with adults within everyday life and spaces (Gottlieb Citation2000), although middle-class babies’ and toddlers’ experiences within the Global South are probably much akin to a segregated model, as the case of Brazil (discussed below) attests.

Oddly paralleling such real-world exclusions, in the ‘spaces’ of academic geography babies and toddlers are normally absent, kept out of the ‘ivory tower’ workplace itself (Gallacher Citation2018) if not always the field (Drozdzewski and Robinson Citation2015) but also debarred from the content of what gets researched. If babies and toddlers feature, they are often conceptualised as ‘objects’: objects of analysis in population geographie s,Footnote8 for instance, or objects of care in feminist geographies. Early feminist geography work, which made critical interventions in understanding the lives of women, nonetheless, spoke of ‘women attached’ (Tivers Citation1985), centralising the caring ‘attachment’ to very young children (see ), and the notable title of one early collection of feminist geography writing was Who will Mind the Baby? (England Citation1996). That said, recent feminist emotional family geographies have transformed the ways babies are figured in geography away from merely objects of care towards subjects in complexly entangled (placed and spaced) relationships between parents, infants and a host of human and non-human others (e.g. Aitken Citation2000, Citation2016; Gabb Citation2004; Luzia Citation2010; Madge and O'Connor Citation2005, Citation2006).

Figure 3. Front cover of Tivers (Citation1985), graphically capturing the ‘attachment’ (or ‘entrapment’) of women with very young children. Reproduced with permission of the publishers.

For instance, Whittle (Citation2019, Citation2021) highlights the interconnected and intersecting subjectivities of carers (primarily mothers) and babies’ mobilities when the baby is carried in a sling, replete with ‘affects as shared and circulating’ (Ahmed Citation2004). Not only does the physicality of a baby influence mobility, but also its emotional being cannot but shape the behaviour and practices of adults. Similarly, Tomori and Boyer (Citation2019) capture the ‘vividly agentic’ infant, disclosing how the irruptive presence of babies transforms parents’ expectations of night-time sleeping arrangements as tied to normative expectations of good parenting in a mid-Western US city. Lone sleeping of infants is the norm dictated by parenting guides and expert advice (particularly in relation to sudden infant death syndrome), and yet, as Tomori and Boyer (Citation2019, 1181) emphasise, ‘babies did not “like” or “want to” sleep on their own. Instead, they wanted to breastfeed and sleep on or near their parents’ bodies.’ Despite the conflict with normative expectations of individual sleeping, which is particularly tied to Minority World practices of the Global North, the parents usually ended up bringing baby into bed with them. In sum, baby agency – in many lexicons, wholly ‘unreasonable’ (non-human) agency full of cries, protests, demands, emissions, thrashing about, and more – easily wins the day (or, rather, the night).

Geographical and social science perspectives on what parents actually do to get their children to sleep could certainly destabilise normative prescriptions emerging from parental support books, which typically end where the difficulties begin. In contrast to expected practices in the mid-Western USA and much of the Minority World, globally the norm is co-sleeping. The idea of co-sleeping as opposed to lone sleeping for babies and toddlers is underpinned by vastly different ideas about the human, with the former constituting humans as vulnerable, intersubjective, mutually constituted and inter-dependent and the latter underpinned by a desire to (re)produce a liberal, sovereign, independent human being (see also Howson Citation2018). These accounts provide an intriguing insight into the agencies and human-ness of babies and toddlers, along with their disruptive capabilities. In these lively and emotionally engaging accounts, however, the perspective continues to be primarily from the adult carers of babies and toddlers. It seems almost inevitable that we cannot approach babies directly as researchers, but recent research has endeavoured to do just that, and it is to this research that our attention is now drawn.

Children’s geographies messed up by babies and toddlers?

Babies themselves exert their will and desires in the world … babies approach city life with a very different sense of sociability to that of adults … mother-baby assemblages can destablise received understandings … a line of flight from normative ways of being … . (Boyer Citation2018a, 49)

More recently, Blaisdell (Citation2019) provides a lively account of a nursery setting in which traditional adult/child power relations are disrupted through a self-consciously participatory approach. She also emphasises the fragilities of these participatory relationships and points to two vignettes when adults took on more traditional roles: one changing a child’s soiled nappy/diaper despite her reluctance; and another trying to get a child to sleep in a bed following parents’ instructions rather than sleeping outside in a pushchair which he preferred. Both of these examples disclose difficulties in maintaining participatory relations within broader unequal adult/child power frameworks. They also evoke a responsibility that adults usually feel for child welfare, which always limits and constraints child agency (Vanderbeck Citation2008), at the same time positioning babies and toddlers as, so it seems, these particularly incapable, necessarily dependent barely-humans.

As Cortés-Morales (Citation2020, 9) elaborates, these approaches emphasise the:

Interdependent character of young children’s mobile practices. A focus on materialities of different kinds reveals various interdependent relationships that are generated, maintained, updated or blocked through movements performed by, around, towards or in relation to young children. On the one hand, in relation to other people, particularly family members and friends with diverse materialities mediating between children and others, either by enabling their physical or virtual contact, facilitating their joint corporeal movement, or by circulating affects between them. On the other hand, in relation to these technologies and objects, and to the manifold people, places, materials and processes involved in their design, manufacture, distribution and regulation.

Similarly, Hackett (Citation2014; also Hackett, Procter, and Kummerfeld Citation2018) shows how the seemingly chaotic ‘zigging and zooming’ of toddlers, walking, running, and tottering around a museum, can (indeed, should) be interpreted as quite other varieties of agentic human ‘place-making’. Horton and Kraftl (Citation2010) illuminate the importance of things – specific toys, objects, balls – to young children: only through directly engaging with young pre-school children could they have discovered that not all balls and plastic toys are equal; only by so doing could they have rediscovered the sorts of distinctions that clearly matter to the tiny humans here, but about which the latter apparently cannot ‘tell’ us anything much at all. The drift of our discussion here deliberately takes us towards the problem of communication, of (self-)representation, and how toddlers and, even more so, babies lie outwith the supposedly normal parameters of being (and performing) human.

The rapture of babies’ and toddlers’ being-in-the-world?

How do [babies] experience time and space in their tiny gestures? How can we diagram these experiences and expand our epistemological menu?. (Guarnieri de Campos Tebet and Abramowicz Citation2018, 925, translated by Louise Holt)

Explicitly developing the field of ‘baby studies’ and, more specifically, a ‘geography of babies’ (Guarnieri de Campos Tebet and Abramowicz Citation2015), Guarnieri de Campos Tebet and Abramowicz (Citation2018, 928) consider how scholars can approach the ‘ways that babies experience space’, drawing upon the Mosaic ApproachFootnote9 developed by Clark and Moss (Citation2011) along with theoretical perspectives from Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1988). They advance ‘cartographies’ of babies that help to ‘‘adjust’ the adult’s gaze to the actions of infants,’ accessing ‘this singular form of expression of the baby, overcoming the adult-centric barrier of language’ (Impedovo and Tebet Citation2019, 10). Such cartographies are themselves informed by Fernand Deligny’s ‘mapping’ of the movements and practices of autistic childrenFootnote10 (Milton Citation2016; SRGSTEL Citation2016), that so inspired Deleuze and Guattari:

[Deligny’s maps] carefully distinguish ‘lines of drift’ and ‘customary lines’. This does not only apply to walking; he also makes maps of perceptions and maps of gestures (cooking or collecting wood) showing customary gestures and gestures of drift … The lines are constantly crossing, intersecting for a moment, following one another … They transform and can even penetrate each other, as in the form of rhizomes. They certainly have nothing to do with language; on the contrary, it is the language that must follow them, it is writing that must feed on them among its own lines. (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1988, 224; in Guarnieri de Campos Tebet and Abramowicz Citation2018).

Interestingly, Hackett (Citation2014) also develops themes to do with entangling (walking and running) ‘lines’, borrowed in her case from Ingold (Citation2007), in order to appreciate something of what toddlers in a museum are seeking to communicate non-verbally to and about their worldly encounters. The key point here, though, is less the specifics of these different studies, and more that adult scholar-researchers are attempting to access and re-present, always imperfectly, the weirdness – almost, we might say, the differently-human – ways in which babies and toddlers experience the world. For these academics, moreover, babies and toddlers offer an ‘experimental’ moment at the limits of the human, possibly also a resource for imagining the world and humanity otherwise (maybe even better).

In a different register, Orrmalm (Citation2020; also Waight and Boyer Citation2018) seeks to get in-close to how babies engage in ‘space-making’ activities – through their tiny movements around rooms, in what they pick up and discard, in what is chewed and what is moved, in how they orientate to the adult-centric heights and proportions of things in the home – and is happy to be surprised by how ‘babies make everyday space differently’ (Orrmalm Citation2020, 677). Via a careful ethnography of early childhood education settings, meanwhile, Rosen (Citation2015) highlights how young children push the boundaries of regulated forms of communication and expose the limits of norms of vocal regulation. In doing so, and drawing upon Kraftl (Citation2013) and others, she exposes the normative limits on agency, which is so often tied not just to voice but to a regulated and rational use of voice as verbalisation. Young children’s screams entirely disrupt the regulated and rational use of voice and present ways of being otherwise.

Echoing such studies, Louise has experimented with family auto-video-ethnography in research about infant feeding, giving participants a camera to video-record feeding infants. Clearly directed by families, usually mothers, the research facilitates close attention to the ‘tiny gestures’ of infants, as witnessed in the following extract (of a video transcribed into textFootnote11):

Sapphire is sitting in the highchair, which is away from the kitchen table, with a tray. Sapphire is chewing, with her hands raised, looking at mum who is out of view of the camera. There is some bread on the highchair tray. A black cat is sitting on a table next to Sapphire, looking at Sapphire and seeming very much part of the scene. Mum says ‘this is boiled carrot, just boiled for a few minutes, so it’s a bit softer’. Mum’s hand stretches across, and hands Sapphire the carrot. The carrot slips out of Sapphire’s hand onto the floor. Mum says ‘there it goes … Have you lost that one?’ Sapphire reaches for the carrot, then looks at the camera and reaches towards it. She smiles. Mum passes a carrot-stick out of baby’s bib onto the highchair tray and says ‘a carrot-stick, and there is also a cheese and stuffing sandwich.’ The cat preens. Sapphire half smiles and picks up the sandwich and sucks/chews it, with dribble dripping onto her bib. Bits of sandwich fall onto the tray and mum says ‘it’s a bit crumbly.’ Sapphire chews and screws the sandwich into a ball. She pulls a funny face and her hand unclasps and the sandwich falls to the floor.

To amplify, the scream, the different ways of being in a space, and the wondering cartographies of babies and infants: all throw into relief the limitations and strictures of what is commonly accepted to be appropriate human subjectivity and expression. They point to other and more ‘rapturous’ – affective, emotional, beyond representational – ways of being, providing potential ‘rhizomatic lines of flight’ and thereby ‘enabling one to blow apart strata, cut roots, and make new connections … rhizome-root assemblages, with variable coefficients of deterritorialization’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1988, 17). These cartographies or ‘absolute transformations that blow apart semiotics systems or regimes of signs on the plane of consistency of a positive absolute deterritorialisation are called diagrammatic’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1988, 136). Babies’ and toddlers’ sometimes riotous and oblivious challenge to the expected forms of verbalisation, emotional expression, movement, and practices in space intimate just such a ‘rapturous’ comportment in the world, indeed offering ‘lines of flight’ and ‘deterritorialisation’ that invite in other forms of subjectivity than the rational, representation and controlled regulation typical – and typically demanded – of both human bodies in spaces and human voices as speech. Babies and toddlers duly capture the moment of potential emotional chaos before they become contained in the ‘arborescence’ of language, of appropriate practices, performances, movements and connections in space.

We can observe the moments in which this joyful, excessive, and sometimes painful openness, wondering, randomness and abandon is cajoled, controlled, and praised into becoming an appropriate, and limited, rational human. Kraftl (Citation2020, 213) points to the potentialities of such a sensibility for inquiry ‘after childhoods’, pushing beyond the common coordinates of how to theorise and research in social studies of childhood, as a means of simultaneously decentring and refocusing on both children and broader spaces in a manner ‘[w]here children would be conceived not as the singular, bounded subject to be moulded in the likeness of our cruel optimisms, but … [so as to] imagine other ways of being. Here, moreover, we point to the value of thinking before childhood, taking seriously those humans so young that their ‘childhood’ has barely started, and there detecting the potential to be otherwise that is imminent in babies’ and toddlers’ ecstatic ways of being-in-the-world.

The ethics of geographers (not) researching babies and toddlers?

Before concluding, it is worth underlining that babies – and, to a lesser extent, toddlers – are not amenable to the kinds of participatory frameworks of research and ethics that have tended to underpin geographies of children and youth (Holt Citation2013; Smørholm Citation2016; Hultgren and Johansson Citation2019). Ethnographies and cartographies present ways of getting close to and examining babies’ own subjectivities: although almost unavoidably findings from the deployment of such methods get re-represented within hegemonic frameworks of (human) language, they can still be left to stand alone for readers’ interpretation. Ethically, though, seeking to understand babies’ subjectivities challenges the very participatory scaffolding of geographies of children and youth: the babies cannot consent to participate, so is it then not legitimate to research them? For ethical committees, parental consent is required and sufficient; but what about within our shared community of scholars, given our ethical paradigms that prioritise the informed consent of children? If we argue that, since babies and (many) toddlers cannot verbalise their informed consent, they should not be researched, are we limiting our inquiries to those subjects who most approximate the liberal, reflective, rational subject? Is it another way of elevating the human, or rather a relatively narrow version of the human to which very many of ‘us’, not just babies, cannot, do not, and do not want to adhere.

If we decide that babies and toddlers are not legitimate subjects of our research, moreover, we continue to hand the very important terrain of earliest childhood studies to developmental psychologists, attachment theorists and so on. Such a hand-over then presents a missed opportunity to intervene on this terrain to highlight the diversity of developmental paths and patterns of babies and toddlers, the diversity of types of attachment across space and time, and the importance of place, space and socio-cultural, economic and political processes to the very fabric and becomings of babies’ and toddlers’ interconnected bodies and minds. This issue is vital because de-contextualised studies (especially of attachment and development) become powerful regulatory norms against which babies, toddlers and parents or carers are measured and which underpin expectations of parenting, caring, education and child development. In short, not to insist upon careful geographical inquiries into babies and toddlers is potentially to foreclose on at least one promising critical avenue whereby standard(ised) models of the human – of the human that all babies and toddlers should supposedly become – remain largely unquestioned.

Conclusion

We are indeed intrigued, surprised and somewhat dismayed by the continued marginalisation of very young children, our tiny humans, within geographies and social studies of children and youth, and, indeed, geography and social science more generally. That said, there are hints – witnessed in various articles cited above – that this neglect is changing, and that an emerging subfield of work on geographies of babies, toddlers and very young children is gradually coalescing. Close attention to babies and toddlers can lend insight into the interconnected bodily and mental formation of human beings within frameworks of subjection. In trying to understand babies’ and toddler’s own subjective experiences and agential practices of and in space, we discover ‘lines of drift’ which are gradually erased through childhood, youth, and adulthood as the endless possibilities become paths travelled and forestalled. Such an attunement provides insight into how things can be otherwise. We also observe how these subjectivities are forged often (although of course not always) in love and care, but always within broader frameworks of power, with, for instance, broader, normative, classed, racialised, gendered, sexualised, and so on norms and expectations about welfare impinging upon even the most participatory or empowering of spaces.

Geographies and social studies of babies and toddlers are critical to challenging the plethora of expert accounts of infants that introduce regulatory norms of development, attachment, and parenting which pay scant heed to the socio-spatial contexts of babies and infants. Then, when babies and toddlers do not reach particular age-related milestones, they are viewed as having difficulties and the solution is usually viewed as labelling, diagnosis, and/or intervening in parenting. A more fully-formed subfield of baby, toddler, and young children’s geographies, one unafraid to hold a more critical and experimental edge, would therefore: (a) challenge individual-focused normative expectations of development and attachment; and (b) be attuned to the broader contexts of babies’ and toddlers’ emergence, the powers and resources available to families and other care settings and how these forge the specific mind-bodies of babies, toddlers and the children, youth and adults they become. It would be respectful to these tiny humans; it would craft alternative tiny human geographies, building in part on the fugitive contributions that have already been made, including to this journal; and it would add to the possibilities of being human in many different ways, shapes, sizes, hues and more.

Acknowledgements

Chris extends his sincere thanks to Louise for getting him involved in this paper, and also acknowledges the wonderful years of his son’s baby- and toddler-hood, the prime inspiration for many elements in our paper. Louise would like to thank Chris for inspiring her to revisit babies that she thought she had left behind as her children reached their middle childhood and teenage years. Thanks also to my three no-longer-but-always-will be babies, who are also the inspiration for this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We use the term ‘toddler’, which is very common in the UK, as a generic descriptor for small children (circa 2 to 4): it is revealing that the term captures a certain quality of embodied movement, a ‘toddling’ motion that is reckoned distinctive and also a clear marker of bodily difference from those usually regarded as ‘proper’ humans (whether children, youth or adult). Of course, there are many other human cohorts whose movement is akin to ‘toddling’, for whatever precise reasons; and here lies a key point of connection between our concerns in this paper and inquiries into, for instance, (critical) disability geographies (e.g. Hansen and Philo Citation2007). Another common phrase in the UK is ‘tots’ or even ‘tiny tots’, one inspiration for writing here of ‘tiny human geographies’.

2 Another simple but profound point is that the epithet ‘young children’ is often used interchangeably with that of ‘small children’, where size (especially height) enters into discriminations between partially and fully ‘human’ (the latter also, revealingly, sometimes cast as being ‘grown up’); and here lies another point of connection between our concerns in this paper and inquiries into the geographies of ‘short people’ (e.g. Pritchard Citation2020).

3 In a more theoretical-phenomenological-geographical frame, Fannin (Citation2014; also Colls and Fannin Citation2013) asks about ‘placental relations’ the ‘mediating’ passages between mother and baby – the ‘mother-fetal relation’ – while Lewis (Citation2018 and commentaries) asks about the ‘uterine geographies’ that demand attention to abortion, miscarriage, menstruation, pregnancy, surrogacy and ‘cyborgs’. There is also the well-known work of Longhurst (e.g. Citation2008) on pregnancy’s many embodiments and geographies. All this material clusters around what might be conceived as a ‘new’ research field concerning geographies of babies, toddlers and very young children.

4 Calkin (Citation2019) has asked questions about political geographies of abortion, which are tied to feminist questions about (sometimes competing) rights and subjectivities, raised by, amongst others, Ruddick (Citation2007). These contested rights and subjectivities are brought into sharp focus in debates about pre-natal screening and abortion (Shakespeare and Hull Citation2018).

5 Also on prams, see Cortés-Morales and Christensen (Citation2004).

6 Also, on pre-school Sure Start Centres in the UK, see Horton and Kraftl (Citation2010).

7 Neither of us will deny that our own having and living with tiny humans has been a provocation for our thoughts (in Holt’s papers, in Philo’s lecture), and indeed traces of such a particular tiny human can be detected in . We must acknowledge the specific circumstances (and privileges) of the baby- and toddler-hoods that we have been fortunate enough to be able to offer our own respective children.

8 A staple subject-matter of population geography has of course been fertility, normally measured in terms of live births per some index of human population in a given region or larger geopolitical unit. Babies hence matter fundamentally to the subject-matter of population geography, yet are almost never considered as tiny humans in their own right, excepting in the margins of a small corpus of more culturally-inflected work on ‘maternities’ such as represented by Underhill-Sem (Citation2001). It is worth underlining that another small body of geographical work has addressed the histories, geographies and spaces of midwifery and child-birth (e.g. Fannin Citation2003; Boyer, Hunter, and Davis Citation2021).

9 Draws upon a variety of methods suitable for children (often although not always creative and visual methods) in order to develop different ‘tiles’ which can be put together to create a ‘big picture’.

10 For work on autistic geographies, see Davidson (Citation2007), Davidson and Smith (Citation2009), and Judge (Citation2018).

11 The video is transcribed to text (and, yes, we appreciate the irony) to preserve the anonymity of the babies and families. In future research, we would be sure to change the consent forms to ensure that we can use anonymised exerts of the videos.

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139.

- Aitken, Stuart C. 2000. “Fathering and Faltering: ‘Sorry, but You Don’t Have the Necessary Accoutrements’.” Environment and Planning A 32 (4): 581–598.

- Aitken, Stuart C. 2016. The Awkward Spaces of Fathering. London: Routledge.

- Blaisdell, Caralyn. 2019. “Participatory Work with Young Children: The Trouble and Transformation of Age-Based Hierarchies.” Children’s Geographies 17 (3): 278–290. doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1492703.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and John Thomson. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Boyer, Kate. 2009. “Of Care and Commodities: Breast Milk and the New Politics of Mobile Biosubstances.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (1): 5–20.

- Boyer, Kate. 2011. “The Way to Break the Taboo is to do the Taboo Thing: Breastfeeding in Public and Citizen Activism in the UK.” Health and Place 17 (2): 430–437.

- Boyer, Kate. 2012. “Affect, Corporeality and the Limits of Belonging: Breastfeeding in Public in the Contemporary UK.” Health and Place 18 (3): 552–560.

- Boyer, Kate. 2018a. “Breastmilk as Agentic Matter and the Distributed Agencies of Infant Feeding.” Studies in the Maternal 10 (1), doi:10.16995/sim.257.

- Boyer, Kate. 2018b. “The Emotional Resonances of Breastfeeding in Public: The Role of Strangers in Breastfeeding Practice.” Emotion, Space and Society 26 (1): 33–40.

- Boyer, Kate, Billie Hunter, and Angela Davis. 2021. “Birth Stories: Childbirth, Remembrance and ‘Everyday’ Heritage.” Emotion, Space and Society 41: 100841.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Calkin, Sydney. 2019. “Towards a Political Geography of Abortion.” Political Geography 69 (1): 22–29.

- Clark, Alison, and Peter Moss. 2011. Listening to Young Children: The Mosaic Approach. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Clement, Susannah, and Gordon Waitt. 2018. “Pram Mobilities: Affordances and Atmospheres That Assemble Childhood and Motherhood on-the-Move.” Children’s Geographies 16 (3): 252–265.

- Colls, Rachel, and Maria Fannin. 2013. “Placental Surfaces and the Geographies of Bodily Interiors.” Environment and Planning A 45 (5): 1087–1104.

- Cortés-Morales, Susana. 2020. “Bracelets Around Their Wrists, Bracelets Around Their Worlds: Materialities and Mobilities in (Researching) Young Children’s Lives.” Children’s Geographies, doi:10.1080/14733285.2020.1789559.

- Cortés-Morales, Susan, and Pia Christensen. 2004. “Unfolding the Pushchair: Children’s Mobilities and Everyday Technologies.” REM 6 (2): 9–18.

- Davidson, Joyce. 2007. “‘In a World of her Own … ’: Re-presentations of Alienation in the Lives and Writings of Women with Autism’.” Gender, Place and Culture 14 (4): 659–677.

- Davidson, Joyce, and Mick Smith. 2009. “Autistic Autobiographies and More-than-Human Emotional Geographies.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27 (6): 898–916.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1988. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Drozdzewski, Danielle, and Daniel F. Robinson. 2015. “Care-work on Fieldwork: Taking Your own Children into the Field.” Children’s Geographies 13 (3): 372–378.

- Dyment, Janet, and Timothy S. O'Connell. 2013. “The Impact of Playground Design on Play Choices and Behaviors of Pre-School Children.” Children's Geographies 11 (3): 263–280.

- England, Kim. 1996. “Who Will Mind the Baby.” In Who Will Mind the Baby?, 12–27. London: Routledge.

- Ergler, Christina R., Claire Freeman, and Tess Guine. 2020. “Walking with Preschool-aged Children to Explore Their Local Wellbeing Affordances.” Geographical Research, doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12402.

- Fannin, Maria. 2003. “Domesticating Birth in the Hospital: ‘Family-Centered’ Birth and the Emergence of ‘Homelike’ Birthing Rooms.” Antipode 35 (3): 512–535.

- Fannin, Maria. 2014. “Placental Relations.” Feminist Theory 15 (3): 289–306.

- Gabb, Jaqui. 2004. “‘I Could Eat My Baby to Bits’; Passion and Desire in Lesbian Mother–Children Love.” Gender, Place & and Culture 11 (3): 399–415.

- Gallacher, Lesley. 2005. “‘The Terrible Twos’: Gaining Control in the Nursery?” Children’s Geographies 3 (2): 243–264.

- Gallacher, Lesley A. 2018. “From Milestones to Wayfaring: Geographic Metaphors and Iconography of Embodied Growth and Change in Infancy and Early Childhood.” GeoHumanities in press.

- Gottlieb, Alma. 2000. “Where Have All the Babies Gone?: Toward an Anthropology of Infants (and Their Caretakers).” Anthropological Quarterly 73 (3): 121–132.

- Guarnieri de Campos Tebet, Gabriel, and Abramowicz Anete. 2015. “Geography of Babies: Following their Movements and Networks.” In: Paper delivered at 4th International Conference on the Geographies of Children, Youth and Families Young People, Borders and Wellbeing, San Diego.

- Guarnieri de Campos Tebet, Gabriel, and Abramowicz Anete. 2018. “Estudos de Bebês: Linhas E Perspectivas de Um Campo Em Construção (Baby Studies: Lines and Perspectives of a Field Being Constructed).” ETD: Educaçao Temática Digital (Ejemplar Dedicado a: Aberturas e Desmoronamentos Na Educação) 20 (4): 924–946. doi:10.20396/etd.v20i4.8649692.

- Hackett, Abigail. 2014. “Zigging and Zooming all Over the Place: Young Children’s Meaning-Making and Movement in the Museum.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14 (1): 5–27.

- Hackett, Abigail, Lisa Procter, and Rebecca Kummerfeld. 2018. “Exploring Abstract, Physical, Social and Embodied Space: Developing an Approach for Analysing Museum Spaces for Young Children.” Children’s Geographies 16 (5): 489–502.

- Hancock, Rodger, and Julia Gillen. 2007. “Safe Places in Domestic Spaces: Two-Year-Olds at Play in their Homes.” Children’s Geographies 5 (4): 337–351.

- Hansen, Nancy, and Chris Philo. 2007. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 98 (4): 493–506.

- Holt, Louise. 2013. “Exploring the Emergence of the Subject in Power: Infant Geographies.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (6): 645–663.

- Holt, Louise. 2017. “Food, Feeding and the Material Everyday Geographies of Infants: Possibilities and Potentials.” Social and Cultural Geography 18 (4): 487–504.

- Horton, John. 2005. “Children’s Everyday Popular Cultural Consumption: Things, Practices, Spacings, Times.” PhD diss., University of Bristol.

- Horton, John, and Peter Kraftl. 2010. “Tears and Laughter at a Sure Start Centre: Preschool Geographies, Policy Contexts.” In Geographies of Children, Youth and Families: An International Perspective, edited by L. Holt, 236–249. London: Routledge.

- Howson, Sara. 2018. “‘I See No Other Option:’ Maternal Practices of Sleep-Training and Co-Sleeping as the Management of Vulnerability.” Studies in the Maternal 10 (1): 1. doi:10.16995/sim.246.

- Hultgren, Frances, and Barbro Johansson. 2019. Including Babies and Toddlers: A New Model of Participation. Children’s Geographies 17 (4): 375–387. doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1527016.

- Impedovo, Maria Antonietta, and Gabriela Guarnieri de Campos Tebet. 2019. “Baby Wandering Inside day-Care: Retracing Directionality Through Cartography.” Early Child Development and Care, doi:10.1080/03004430.2019.1680548.

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. “Materials Against Materiality.” Archaeological Dialogues 14: 1–16.

- James, William. 1890. “The Perception of Reality.” In Principles of Psychology. Vol. 2, 283–324. New York: Henry Holt.

- Judge, Sarah M. 2018. “Languages of Sensing: Bringing Neurodiversity into More-than-Human Geography.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (6): 1101–1119.

- Kraftl, Peter. 2013. “Beyond ‘Voice’, Beyond ‘Agency’, Beyond ‘Politics’? Hybrid Childhoods and Some Critical Reflections on Children’s Emotional Geographies.” Emotion, Space & Society 9: 13–23.

- Kraftl, Peter. 2020. After Childhood: Re-Thinking Environment, Materiality and Media in Children’s Lives. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- Lewis, Sophie. 2018. “Cyborg Uterine Geography: Complicating ‘Care’ and Social Reproduction.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (3): 300–316.

- Longhurst, Robyn. 2008. Maternities: Gender, Bodies and Space. New York: Routledge.

- Luzia, Karina. 2010. “Travelling in Your Backyard: The Unfamiliar Places of Parenting.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (4): 359–375.

- Macallister, Louise. 2016. “Feeling, Caring, Measuring, Knowing: The Relational Co-Construction of Parenting Knowledges.” Children's Geographies 14 (5): 590–602.

- Madge, Clare, and Henrietta O'Connor. 2005. “Mothers in the Making? Exploring Liminality in Cyber/Space.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 30 (1): 83–97. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00153.x.

- Madge, Clare, and Henrietta O'Connor. 2006. “Parenting Gone Wired: Empowerment of New Mothers on the Internet?” Social & Cultural Geography 7 (2): 199–220.

- Milton, Damian. 2016. “Tracing the Influence of Fernand Deligny on Autism Studies.” Disability & Society 31 (2): 285–289.

- Newell, Lucila. 2013. “Disentangling the Politics of Breastfeeding.” Children's Geographies 11 (2): 256–261.

- Orrmalm, Alex. 2020. “Culture by Babies: Imagining Everyday Material Culture Through Babies’ Engagements with Socks.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 27 (1): 93–105.

- Philo, Chris. 2017. “Less-than-human Geographies.” Political Geography 60 (4): 256–258.

- Philo, Christopher. n.d. “Barely-Human Life?’ Babies, Toddlers and Small Children”, Lecture Delivered on Various Dates in the 2010s in Honours Undergraduate Option Course on “Social Geography of ‘Outsiders’.” Available from Author.

- Pritchard, Erin. 2020. Dwarfism, Spatiality and Disabling Experiences. London: Routledge.

- Rosen, R. 2015. “‘The Scream’: Meanings and Excesses in Early Childhood Settings.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 22 (1): 39–52.

- Ruddick, Susan. 2007. “At the Horizons of the Subject: Neo-Liberalism, Neo-Conservatism and the Rights of the Child Part One: From ‘Knowing’ Fetus to ‘Confused’ Child.” Gender, Place and Culture 14 (5): 513–527.

- Shakespeare, Tom, and Richard J. Hull. 2018. “Termination of Pregnancy After non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT): Ethical Considerations.” Journal of Practical Ethics 6 (2): 32–54.

- Smørholm, Sesilie. 2016. “Pure as the Angels, Wise as the Dead: Perceptions of Infants’ Agency in a Zambian Community.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 23 (3): 348–361.

- Society for Radical Geography, Spatial Theory, and Everyday Life. 2016. “Fernand Deligny: Mapping Autistic Gestures and Trajectories, and the “Wander Line””. Society for Radical Geography, Spatial Theory, and Everyday Life (wordpress.com): https://radicalspacesblog.wordpress.com/2016/08/11/ferndad-deligny-mapping-autistic-gestures-and-trajectories-and-the-wander-line/.

- Templeton, Tran Nguyen. 2020. “That Street is Taking Us to Home’: Young Children’s Photographs of Public Spaces.” Children's Geographies 18 (1): 1–15.

- Tivers, Jacqueline. 1985. Women Attached: The Daily Lives of Women with Young Children. London: Croom-Helm.

- Tomori, Cecilia, and Kate Boyer. 2019. “Domestic Geographies of Parental and Infant (Co-) Becomings: Home-Space, Nighttime Breastfeeding, and Parent–Infant Sleep.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1558628.

- Underhill-Sem, Yvonne. 2001. “Maternities in ‘Out-of-the-Way’ Places: Epistemological Possibilities for Re-theorising Population Geography.” International Journal of Population Geography 7 (6): 447–460.

- Vanderbeck, Robert M. 2008. “Reaching Critical Mass? Theory, Politics, and the Culture of Debate in Children’s Geographies.” Area 40 (3): 393–400.

- Waight, Emma, and Kate Boyer. 2018. “The Role of the Non-Human in Relations of Care: Baby Things.” Cultural Geographies 25 (3): 459–472.

- Whittle, Rebecca. 2019. “Baby on Board: The Impact of Sling Use on Experiences of Family Mobility with Babies and Young Children.” Mobilities 14 (2): 137–157.

- Whittle, Rebecca. 2021. “Towards Interdependence: Using Slings to Inspire a New Understanding of Parental Care.” Children’s Geographies, doi:10.1080/14733285.2021.1955091.