ABSTRACT

Meeting multiple, often competing objectives when seeking to sustainably intensify their agricultural operations is a constant challenge for smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Trade-offs between social, economic and environmental goals at different time and spatial scales need to be reconciled, making best use of scarce resources. This study explored how different types of farm households in Northwest Ghana, Eastern Burkina Faso and Central Malawi make choices about resource allocation and farming strategies, and how they manage the trade-offs encountered. It used both quantitative (questionnaire survey) and qualitative (household case studies) methods to identify trade-offs experienced by farmers and to analyse trade-off management strategies used by them. The 10 main trade-offs identified across the 3 countries occurred across sustainability domains, across time, across spatial scales, across types of farmers or a combination of these. Famers were disincentivized from prioritizing long-term sustainability in their farming operation by resource constraints to meet multiple farming and livelihood objectives, mainstream agricultural policies encouraging short-term productivity gains and adoption-focused interventions, which disregard the diversity of farming households.

Introduction

SmallholdersFootnote1 in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are faced with difficult choices as they aim to meet multiple individual, household, community and wider societal objectives. By constantly adapting their farming and livelihood strategies, farmers and their communities are treading a fine line between long- and short-term goals and social, environmental or economic objectives; as well as the interests of different individuals and groups (ASFG, Citation2013). At the same time, farmers are increasingly encouraged by their governments and international development organizations to follow a pathway of ‘sustainable agricultural intensification’ (SAI) to meet food security objectives (SDG2), while reducing the environmental footprint of agricultural production. As early as in Citation1987, the Brundtland Commission concluded that ‘ … to achieve global food security, the resource base for food production must be sustained, enhanced, and, where it has been diminished or destroyed, restored’. Subsequently, in 2009, the United Kingdom's Royal Society drew attention to ‘the pressing need for the ‘sustainable intensification’ of global agriculture in which yields are increased without adverse environmental impact and without the cultivation of more land’ (Royal Society, Citation2009). This sparked two decades of SAI research and development initiatives, many of which are rebrands of conventional agricultural productivity enhancing programmes (Garnett & Godfray, Citation2012; Cook et al., Citation2015).

However, the concept of SAI in itself requires a careful consideration of the potential trade-offs between its three sustainability dimensions or pillars – social/human, environmental, and production/economic (Purvis et al., Citation2019). At a time of increasing pressures on natural resources in SSA, these objectives are often in competition with each other. Farmers find themselves at the forefront of managing the emerging trade-offs between food security, environmental and social objectives. In doing so, multiple needs and interests at different temporal and spatial scales (e.g. field, household and community levels) need to be reconciled (Klapwijk et al., Citation2014).

There is a long history of trade-off analysis in agricultural research and development, ranging from using experimentation and modelling to identify the optimal use of resources at plot level, to complex systems analysis aimed at integration of environmental and socioeconomic objectives at different spatial scales. Much of the literature focuses on specific technological choices and their impact on other components of the farming system (e.g. use of crop residues for mulching or as livestock feed, Rusinamhodzi et al., Citation2015), without explicitly considering the wider socioeconomic context of the household or individual. These studies are useful for informing future research priorities, but do not necessarily support household-level decision making, as they fail to consider a number of key factors. In particular, they neglect opportunity costs of household labour and capital, security of access to land and other production factors, and personal preferences in terms of, for example, risk adversity, attitude to innovation, or values attached to different outcomes. If the outcomes of such studies were to be directly translated into extension messages for farmers and into policy recommendations for governments, without further validation and contextualization, the recommendations could potentially even undermine sustainable farming strategies by impacting negatively on other, connected, household objectives and needs.

SAI development programmes and strategies implemented in SSA have so far not considered trade-offs explicitly. Rather, they tend to promote individual technologies or packages of technologies to increase productivity, without much consideration of the social differentiation and dynamics in rural landscapes (Snyder & Cullen, Citation2014). An alternative approach to trade-off analysis and management considers all objectives, from a farm and household perspective, and identifies where these are competing (or where they cannot simultaneously be maximized) and where potential synergies may exist. Decisions about farming practices are not taken independently of other decisions but are intrinsically linked. The Sustainable Livelihoods (SL) Framework (Carney, Citation1998) connects ‘capitals’ (social, human, environmental, physical and financial assets), livelihood strategies (basically how these assets are used) and (desired or actual) livelihood outcomes with a range of factors (policy, institutions and processes) supporting or hindering the success of these livelihood strategies. When considering the SL framework as an iterative (e.g. seasonal) cycle of decision making, livelihood outcomes have a direct bearing on assets available in the next cycle, and hence on strategic options available to a household. In the short to medium term, a household's assets will be a key determinant of farming practices, enabling some choices, but limiting others.

But whilst the SL framework is useful in conceptualizing decision making, it has been criticized for being too linear and simplistic, and underplaying the important role of local, national and global policies and institutions in shaping decisions of farmers and rural people (Scoones, Citation2009). This is where a deeper analysis of contextual factors and their influence on individual choices is required – both from the perspective of an individual farmer and household, and a community perspective. Actor-oriented approaches focus explicitly on the influence of context on individual choices. Emerging findings can be enriched and validated through the involvement of the wider community, who can also contribute to the development of policy recommendations. The aim is for recommendations to lead to transformational changes beyond the adoption and adaptation of individual technologies. This is in line with recent thinking on the need to move from pilots to scale via ‘sustainable systems change’, including a shift to more diversified agroecological system, which requires overcoming a number of ‘lock-ins’ that prevent farmers from adopting longer-term innovations to address environmental issues (IPES Food, Citation2016). Such systems change requires altering key drivers (incentives, rules, and so on) such that ‘the system that once perpetuated a “problem” now instead perpetuates a “solution”’ (Woltering et al. Citation2019).

Musumba et al. (Citation2017), in their Sustainable Intensification Assessment Framework, used objective-oriented indicators to assess SAI and trade-offs: ‘The inclusion of social aspects helps ensure a balanced approach to the intensification process’. They organize indicators into five domains critical for sustainability: productivity, economic, environment, the human condition, and social domains – these map against the three sustainability pillars of the Brundtland Commission when merging ‘productivity and economic’ into ‘economic’, and ‘human condition and social’ into ‘social’.

This paper explores how smallholders in Northwest Ghana, Eastern Burkina Faso and Central Malawi perceive and manage trade-offs and synergies between production, socioeconomic and environmental factors. It uses the wider definitions of SAI outlined above and applies an actor-oriented and systemic perspective. Using a mixed-methods approach, it identifies the main trade-offs that different types of smallholders encounter and analyses the strategies that these farmers employ to manage them in the face of an increasingly unfavourable climatic, economic and governance environment. The paper concludes with a discussion of ways in which developmental interventions could better support smallholders’ decisions to move towards a prioritization of longer-term sustainability considerations.

Approach and methods

The study was conducted between July 2016 and August 2019 in Eastern Burkina Faso, Northwest Ghana and Central Malawi. These locations were selected because (1) SAI is being promoted proactively by government and NGOs, (2) the research team could build on existing networks and previous partnerships and (3) they represented two contrasting regions in SSA. The research included six stages, with each one building on the findings of the previous:

Farming and livelihoods analysis and site selection

Participatory identification of indicators for the social, environmental and economic dimensions of SAI

Quantitative household survey to measure SAI indicators

Principle component analysis (PCA) to identify patterns and select case study households

Qualitative household case studies

Analysis, reflection, development and validation of recommendations with communities and stakeholders.

Compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was assured throughout, with respondents being informed about the use of the information and their rights, and responses being anonymized.

Farming and livelihoods analysis and site selection

An initial document review was undertaken to provide background information about farming systems and rural livelihoods in the wider study area, and the factors influencing them (policies, institutions, shocks and trends), using the SL framework. This review was complemented by key informant interviews at sub-national and local level (with staff from ministries of agriculture, farmer organizations, local government and development organizations). The review and additional expert advice were used to select two (Malawi) to eight (Burkina Faso) communities per country for the quantitative survey. The willingness of communities to participate in the study and their accessibility were also considered. For the qualitative research phase, two villages were selected from among the initial two to eight, ensuring that they varied in terms of accessibility.

The main characteristics of the study sites are shown in . Farming systems in all locations were mixed crop-livestock systems, mostly rainfed with small pockets of irrigated vegetable production along the streams, near hand pumps or wells. The West African sites (located in Lawra and Nandom Districts of Upper West Region, Ghana, and in Gourma and Gnagna Provinces of Eastern Region, Burkina Faso) were less than 500 km apart and located in a similar agroecological zone. They showed a number of similarities in terms of farming and livelihood strategies (), being far from the capital cities, in relatively remote areas with poor infrastructure and few employment opportunities. They were characterized by a large range of household and farm sizes, depending on the age of the household, with older households and extended families normally having more members and larger agricultural holdings than younger households and nuclear families. In Malawi (Mwansambo EPA – Extension Planning Area – of Nkhotakota District, Central Malawi), households and farms were smaller and less diversified, and more dependent on off-farm agricultural and non-agricultural work than in West Africa.

Table 1. Main characteristics and SAI indicators for the six research sites.

Participatory identification of SAI indicators

Indicators for SAI were codeveloped at each site between the research team and community members, in order to inform the design of a quantitative household survey. Focus group discussions (FGDs) with men, women and youths from the two to eight villages included in the research were held to identify indicators for the social, economic and environmental dimensions of SAI. Group members were initially asked ‘what would “ideal” SAI look like in your villages’? Based on those visions, indicators were developed by the researchers and validated again via FGDs The indicators were prioritized by the researchers based on (a) their importance to the community (the extent to which they measure dimensions of SAI that matter to them) and (b) the feasibility of measuring them using a household questionnaire (rather than field-level measurements, which was beyond the scope of the project).

Quantitative household survey

A sample survey of approximately 10% of all households in the selected two to eight villages was undertaken, resulting in a sample of 130–150 households per country. The aim was to collect quantitative information about the SAI indicators identified in step 2 above, and general information about household and farm characteristics, agronomic practices, food security and assets.

The survey was then initially analysed using descriptive statistics to identify basic patterns. Using the Pareto principle, a reduced number of SAI indicators were then used to rank sampled households based on their SAI performance (i.e. along economic, social and environmental dimensions or categories).

Principle Component Analysis (PCA) and selection of case study households

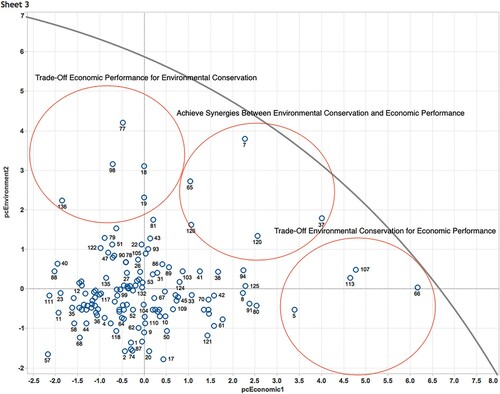

Bivariate relationships between economic, social and environmental factors were shown using scatterplots and to gauge SAI. PCA was used to reduce the number of indicators down to one or two that best showed how households vary within these broad categories of indicators. PCA is particularly useful for the sustainable intensification of agriculture, due to the conceptual framing of dividing sustainable intensification into broad ‘categories’ (i.e. the economic, social and environment dimensions). If the conceptualization is correct, indicators within each category should be related by providing a different perspective on the same broad process (i.e. social, economic or environmental). For example, farming households with high levels of organic fertilizer use were also likely to use soil and water conservation practices. Crucially, conducting PCA enabled the assignment of scores of farming households based on the range of variables included.

The bivariate relationships between different principal components were used to determine the performance of households (high/medium/low) in terms of the sustainable intensification dimensions – i.e. how farming households performed relative to others. Each of the principal components is a variable that is newly constructed based on multiple variables that apply to the category of economic performance and environmental conservation. Those households high up the Y axis (i.e. environmental principal component) but low on the X axis (i.e. the economic principal component) are trading off environmental conservation relative to economic performance; while those high up the X axis but low up the Y axis are trading off economic performance for environmental conservation. Only those in the centre circle close to the production possibility frontier are able to improve economic and environmental outcomes simultaneously, and thus are achieving synergies. However, the majority of households are clustered at the base of the X and Y axes, where the performance on both outcomes is moderate to weak.

Using the PCA-generated scatterplots, such as the one shown in , 12 households from among those surveyed were purposefully selected in each country for in-depth case studies, using a combination of performance categories to include households that (a) score low in all categories, (b) score high in some but low in others (indicating trade-offs) and (c) score high in all categories – possibly indicating the use of farming practices that are synergistic. Household members of selected households were then provided with detailed information about the objectives, methods and schedule of the in-depth household case study phase, and about the intended use of the information they were to provide and were then given the choice to participate or opt out. In Malawi, three households opted out because they left the locality.

Qualitative community assessment and household case studies on SAI trade-offs

The in-depth household case studies were the main research stage, lasting almost 18 months and involving nine community-level exercises and 14 household-level ones () in each of the 6 locations (2 sites per country). The main tools used were (a) community-level exercises, to collect information and to report back and validate emerging findings, and (b) semi-structured individual or household interviews. At both community and household level, visualization was used where appropriate to enable the inclusion of non-literate household or community members, focus the discussion and enable critical engagement with the findings by all participants. A detailed methods manual was developed to collect information about contextual and enabling factors systematically (at community and national level – including agricultural policy intervention) and household decision-making processes. The manual built on experiences of the West African PRA (Participatory Rural Appraisal)/MARP (Méthode Active de Recherche et de Planification Participatives) network, of which some project partners were members. This enabled exploring the wider context, motivations and values underpinning farmers’ decision making (Chambers, Citation1994), whilst it reflected the values and ways of working of the NGO partners involved in this research.

Table 2. Household case study exercises.

Originally, some exercises were meant to be conducted with men, women and youths of each household participating separately. However, this proved to be too time consuming and hence met with some resistance from the case study households. Therefore, exercises were carried out with whomever was available at the time of the enumerators’ visit. Responses were cross-checked with other household members during subsequent visits and any differences in practices or perceptions between men, women and youths were noted.

Analysis, reflection, development and validation of recommendations

The outcomes from each exercise were documented both as a narrative and also in tabular form for quantitative or categorical information. Findings were then analysed by recording competing objectives in a ‘trade-off tracker’, based on the five trade-off categories proposed by Musumba et al. (Citation2017), i.e. (a) within a sustainability domain (productivity, economic, environmental, human and social), (b) across domains, (c) across spatial scales, (d) across time and (e) across types of farmers. A simplified version of this format was also used for feedback and validation sessions in the communities.

Results and discussion

Farming and livelihoods systems

In the West African sites, mature households tended to be large; in Ghana they contained up to 15 members and in Burkina Faso up to 32, with correspondingly large farms (up to 9.2 ha and up to 13 ha respectively). Younger households that had split from the extended family were smaller, but normally maintained links with their parent household to support their farming and livelihood strategies.

Farmers in the four West African research communities aimed to achieve household food security through their own food production and, to a lesser extent, by purchasing food, using income from sale of food or cash crops and from off-farm activities. The range of crops grown was wide and included different types and varieties of cereals, legumes, oil seeds and vegetables. Livestock played an important role by providing cash income, draught power (for land preparation and transport) and manure. The use of external inputs (improved seed, fertilizer and agrochemicals) was increasing, but was still at a low level, with most farmers growing at least some local crop varieties and using organic soil amendments.

In West Africa, women and youths often had their own fields, allocated to them by the household head (who was normally male). While household members would have to work in the main household field (usually a large field used to grow staple food crops) first, they would be able to manage their ‘own’ plots independently, choosing what to grow, how to grow it and what to do with the produce. These plots would be an important source of cash for women and youths, who did not normally have easy access to other off-farm income sources.

Most households in the West African communities sold only a small proportion of their produce – normally limited to off-season vegetables, livestock and livestock products, and some cash crops (sesame, groundnut and some cow pea in Burkina Faso; and groundnuts, cow pea and sorghum in Ghana). In most households, at least one family member had either left the village to migrate to other parts of the country or had some off-farm income from petty trade, artisanal mining or other trades. The role of traditional leaders, customs and norms was relatively strong and community members tended to support each other in times of crisis. The findings from the West African sites confirm trends documented elsewhere in the region (Toulmin, Citation2020).

In contrast, in Mwansambo EPA in Malawi, households and farms tended to be much smaller than in the West African sites, rarely exceeding five to six family members and 1 ha (). Normally all household members would cultivate the land together, without women having plots of their own. Mwansambo has a long history of cash crop production, including tobacco, cotton, and, more recently, soybeans and groundnuts (FEWS NET, Citation2015). However, most smallholders did not produce enough of the staple food crop, maize, and relied on cash crop sales and off-farm income (often from agricultural labouring) to feed their families. Several of the case study households found themselves caught in a vicious cycle of debt from the purchase of fertilizer and herbicides, and low productivity and low investment in their farms, with the common practice of maize-groundnut rotation on its own not sufficient to sustain maize yields.Footnote2 Land preparation was entirely manual, and few farmers owned large ruminants. Farmers relied heavily on external inputs, in particular seed (both maize and groundnuts), fertilizer and herbicides (introduced initially as part of Conservation Agriculture programmes).

In all three sites, smallholders were under pressure as a result of: climate change impacts; population growth; natural resource degradation and competition for resources; and ineffective governance and support systems at local and national level. The latter made it harder for farmers to address these challenges within their specific context and level of resources.

Household resources

Within the broader farming systems and livelihood systems outlined above, the study found large differences between individual case study households in each site in terms of household composition, ownership of and access to resources, and farming practices. Building up assets over time was an important livelihood strategy used by many of the households studied, in order to increase resilience to shocks and provide a wider range of livelihood options in the longer term. The household case studies demonstrated clearly how access to resources and production factors (labour, land and capital) had a direct bearing on farmers’ options ().

Table 3. Main SAI trade-offs faced by case study households in Burkina Faso (BF), Ghana (G) and Malawi (M).

Labour, know-how and social networks

The case study households presented a wide range in terms of overall size, gender, age composition, dependency ratio and occupation. In particular in Ghana and Burkina Faso, household sizes varied significantly – but it was not just size that mattered. Household composition was equally important when it came to the choice of farming practices adopted. ‘Young’ households with a large number of small children had a ‘double burden’: they needed to produce or purchase large quantities of food but did not contain a strong work force. Such households were particularly vulnerable, and the illness of one of the adult members could lead to a downward spiral in the household's fortunes. The link between household size and resilience has been well documented in West Africa/the Sahel (FAO, Citation2011; Perez et al., Citation2015), with larger households that have a low-dependency ratio (that is, the number of dependents relative to the total active work force) being able to pool labour, diversify livelihoods and spread risks.

A less tangible factor is the capacity (in terms of knowledge, skills, experiences and attitudes) of different household members. Formal education was a poor measure for these qualities, with some of the leading farmers in the communities (in terms of adoption of improved farming practices and livelihood outcomes such as food security) having limited formal education, but a wide range of experiences. An open attitude to innovation and change was often associated with a history of migration – in Burkina Faso, this could involve cross-border migration to Côte d’Ivoire; in Ghana, it normally involved moving South to the larger cities or the cocoa belt. Membership of community-based organizations (such as village-level saving groups or gardening groups) also tended to have a positive influence on farmers’ attitudes to innovation and change, which is confirmed in the literature (Meijer et al., Citation2014).

A specific challenge related to household labour was observed in Malawi, where some Christian men had second or third wives without the regulatory institutions in place for polygamy found in Muslim societies. Some men married a second wife to increase the household's labour force, because of illness or the first wife's inability to work.Footnote3 This polygamy might result in a large number of young dependants, making it harder for the head of household to produce enough food for everyone.

Land

There were large variations in farm size and composition between case study households in the three locations. Larger households tended to farm more land, but this was not always the case due to other constraints, such as the overall availability of land in the location and access to other resources necessary for cultivation. In addition to farm size, the type, size and location of individual plots are also important factors in agricultural decision making. They may limit a household's choice with regards to the types of crop grown, crop rotation and adoption of specific agricultural technologies or intensification options.

In all three sites, access to farmland was becoming increasingly difficult, in particular for younger farmers who were starting a household of their own. In Malawi, farm sizes were smallest, with young households often forced to move away from their native villages to find land to cultivate, and some farmers hiring land against cash or in-kind payments. In Ghana, until the late 1980s, farming land was relatively abundant in the Upper West region and households were able to expand the area they cultivated whenever needed (with permission from the local chiefs). A farming systems study undertaken in Wa and Nadowli districts of the Upper West region of Ghana (Adolph et al., Citation1993) noted that good farmland was starting to become scarce in some areas due to population growth, and the reduction of the length of fallow periods. This trend has continued in both the Ghana and Burkina sites, where the length of fallow periods has significantly reduced, with most land now farmed continuously.

However, larger farms can also mean that family labour is spread over a larger area, making it more difficult to adopt labour-intensive SAI practices. Farmers in the West African research sites were aware of this and are increasingly focusing their attention on compound and village farms (located close to their homestead) rather than bush farms (plots of land further away from the village). Only one out of 12 case study households in Ghana had a bush farm, whereas in 1993, most households in that part of Ghana had bush farms (Adolph et al., Citation1993).

Hence population pressure resulting in land pressure has both positive and negative impacts: small farms are more vulnerable and off fewer choices in terms of allocating land for different purposes, but by concentrating resources in a smaller area, adoption of SAI practices may be increased. The current study did not assess the links between agricultural intensification and expansion of land under cultivation systematically. However, there are some indications that increases in productivity as a result of technological change do not automatically stop expansion – in particular where land governance and the protection of natural habitats is weak. For most of the case study households, expansion of farmlands was part of their longer-term strategy (both to keep up with population growth and to make use of market opportunities) even where productivity was not yet very high. This confirms the findings of the global analysis by Byerlee et al. (Citation2014), which concludes that intensification, in particular when driven by markets, often drives the expansion of land under cultivation.

Capital and income

Access to capital was a key constraint for all case study households in all sites. Financial resources were needed to meet non-food expenses (in particular, school fees, medical fees and essential non-food items such as clothing) and to purchase agricultural inputs. Because of their low levels of market integration, households in the West African sites mostly relied on off-farm income from migration, mining and so on, and livestock sales for cash. In the Malawi sites, groundnuts were the main cash crops grown by all farmers, providing income for purchasing maize (the staple food) and inputs to grow it (fertilizer, seeds and herbicides). Because of their high level of dependency on external inputs, Malawian farmers often resorted to taking loans, in cash or kind, from fellow farmers or input dealers at high rates of interest (100–200% p.a.), resulting in a debt trap that it was difficult to escape from.

In all three study locations, formal credit was not generally available to farmers. In the West African sites, village-level saving groups had been established by NGOs to access small loans, but these were normally designed for micro-enterprises or petty trade and not for agricultural investments. However, in Burkina Faso, some women used part of their loans to buy seeds, pay for the preparation of land on their own plots, or to start livestock husbandry activities. Larger, diversified households with different income sources were clearly at an advantage and able to pursue farming strategies that required some initial investments.

Farming household objectives, trade-offs and implications for SAI

In this study, we considered trade-offs in relation to Sustainable Agricultural Intensification (SAI), whereby a choice needs to be made between two or more desirable but competing objectives. Using an actor-oriented approach, the study asked farmers about their overall goals – for themselves and their household members – and the strategies used to achieve those. It then traced SAI-related sub-objectives within those higher-level objectives, not only in the present, but also how these evolved over time. This varied between households, individuals – male and female, younger and older household members – and length of time – short, medium or long term. Using the objectives of case study household members as a starting point made it possible to move beyond an analysis of simple binary choices between, for example, the adoption or non-adoption of SAI-related farming practices.

The main objectives that case study household members aimed to achieve were as follows:

Food security, i.e. the ability to either produce or procure sufficient amounts of desirable food throughout the year. In the West African sites, a stronger emphasis was placed on household food self-sufficiency from people's own production, whereas Malawian farmers aimed to meet food needs through a combination of cash crop sales and food crop production.

Education, in particular primary and secondary school education for all children, and in some cases further education or training for young adults. In some cases, farmers associated education directly with earning capacity, thus addressing objectives (1) and (3), but mostly education was seen as a desirable achievement in its own right, even if tangible benefits were not immediately visible.

Income, to support (1) and (2) above, and to pay for household needs such as medical costs, housing, agricultural inputs and personal needs – clothing, transport, mobile phones.

Social harmony, i.e. meeting social obligations to the community, having a high social standing in the community, and avoid conflicts. This objective was more prominent in the West African sites and seemed to matter more to older people.

Environmental quality, i.e. clean and abundant water resources, trees for shade and firewood, biodiversity in terms of a richness of plants and wildlife. Again, this was more important to farmers in West Africa.

These are not listed in order of priority. Different individuals and households, depending on their current socioeconomic situation, would emphasize different objectives. In order to achieve these objectives, people used a combination of strategies, which in themselves could be expressed as (subordinate) objectives. For example, in order to achieve food security, a farmer may want to plant his or her crops early (as soon as the rains start), or be able to purchase good quality seed, or keep good relations with other community members so that they are willing to provide labour or capital. These specific objectives, relating to the overall selected livelihood strategy, varied between individuals and households and depended to some extent on their (perceived) ability to implement the strategy.

Trade-offs occurred whenever objectives or sub-objectives competed – either because resources were not sufficient to achieve several objectives simultaneously, or because the objectives themselves were mutually exclusive. When deciding what (sub-) objective or strategy to pursue, case study farmers considered a number of factors, including the following:

Available resources. This factor mattered where the main trade-off resulted from competition for limited resources. Ownership of, access to and control over means of production at the individual and household level were at the forefront of decision making, with case study households mentioning them routinely as the main reasons for using a particular strategy. Shortage of labour and capital resulted in farmers not being able to implement a desired strategy (such as adoption of soil and water conservation measures, use of external inputs or expansion of the area under cultivation). Access to resources was closely linked to the enabling or disabling environment – including matters such as land tenure, subsidies, and wider policy choices about agricultural intensification pathways.

Undesirable impacts. Some strategies have negative impacts – either immediately or in the future. Case study farmers were aware of these, both as a result of their own observations and experiences, and because of awareness-raising and participation in training activities by development agencies. To what extent these impacts were considered depended on the scale of the impact, its visibility, the extent to which the individual or groups causing the impact were themselves affected, and the time frame in which it occurred – but also on the individual farmer's attitude and knowledge. For example, differences in perception of the wider environmental impacts of certain farming decisions (such as the use of pesticides and herbicides or the use of land along riverbeds for intensive horticulture) varied significantly between individual farmers, even within the same community. In Burkina Faso, farmers observed that the use of herbicides had a negative impact on soil quality and livestock health, with government regulations for the trade and use of these herbicides not enforced (as also noted by Rodenburg et al., Citation2019).

Public opinion and reputation. Farmers were influenced by fellow farmers, traditional leaders, NGOs and government agencies, even where these had no direct influence on productive assets. In some cases, farmers used certain practices or strategies because they were (or wanted to be seen as) early adopters and innovators, even when they were not convinced of the benefits of the practice.

Larger households with more resources were in a better position to pursue multiple objectives and strategies, albeit not all to the same extent. In comparison, smaller households did not have the capacity to diversify livelihood strategies and farming practices and were often forced to ‘put all their eggs in one basket’. These differences between households impacted directly on their ability to pursue a SAI strategy (see also ‘Labour, know-how and social networks’ section above).

summarizes the 10 main decisions and trade-offs recorded in the study locations, including the competing objectives that make up the trade-off. It also outlines how ‘more sustainable choices’ could be better supported by an enabling environment. Each decision (between two or more options) needed to consider several objectives, which may have been objectives of individual household members, of the household overall, or the community. For example, within a household, the household head may have prioritized increasing food production for household food security, whereas his or her son may have prioritized production for sale and income. Based on the household case studies, meeting a specific objective was contingent on a specific choice. For example, when the objective was to match the crop-maturing period to the shortening rainy seasons, the choice was for an improved short-duration variety, whereas when the objective was to meet food preferences, using local varieties may have been the preferred choice. Each farmer's ability to meet a specific objective by choosing a specific option depended to a large extent on resources, with better-off households generally being able to implement options more readily than middle-income or poorer households. Farmers’ current practices and choices were a result of (a) their prioritized objectives and (b) their ability to implement the preferred choice. This ability was influenced by a number of enabling (or disabling) factors, which shaped the context of decision making and could be modified to incentivize decisions that balance short- and long-term outcomes, individual and community outcomes, and economic, social and environmental outcomes.

Overall, the farmers’ most common trade-off management strategy was to compromise and ‘do a bit of everything’ – for example, to use residues for livestock feed, as a mulch and as a fuel; use some herbicide but also undertake manual weeding; grow some cash crops and some food crops, and so on. In some cases, these management practices may have been a way of coping with insufficient resources rather than a deliberate choice; for example, a farmer may have had insufficient cash to buy more herbicides and hence was forced to weed manually. During discussions with the case study households, it became evident that the extent to which choices are made deliberately depended largely on the individual's awareness of all management options.

Only 2 of the 10 decisions fit into the ‘within a domain’ category; the majority involve decisions between domains (). In the latter case, farmers were basically making choices not just between objectives, but also between sustainability dimensions, timescales or spatial scales. Generally, farmers were willing or forced to accept short-term economic benefit (at a long-term environmental cost) over short-term economic loss (for a long-term environmental benefit), because they were unable to forego the short-term benefit (e.g. producing food for their families by mining soils, or migrating to gain an income), even if it was associated with longer-term costs (e.g. land degradation or insufficient time invested in farming leading to low productivity). Some environmental costs (e.g. pasture degradation from herbicide use or erosion of riverbanks from riverside gardens) were not immediately visible and might be experienced by the community overall rather than the individuals causing them – requiring regulatory institutions at the community level.

Table 4. Summary of key decisions, their trade-offs, dimensions and potential synergies.

Enabling and disabling factors

Farmers’ choices were influenced by contextual factors that enabled or disabled the pursuit of different options. These factors had a direct bearing on farmers’ access to resources needed for sustainable intensification. They included the wider technological, political, policy and cultural context and the incentives or disincentives to pursue choices:

Technologies such as agroecological practices, new crop varieties, implements and inputs and their availability at community level influenced farming practices. For example, the introduction of herbicides has changed land preparation practices, in particular in Malawi, and enabled the adoption of a particular type of conservation agriculture based on zero or minimum tillage.

Prices and markets influenced farmers’ choice of crop and livestock enterprises. This included both the demand for, and price of farmers’ produce at harvest time, and the price and availability of food and other commodities at the time when farmers want to purchase them. In Malawi, farmers’ decisions to grow groundnuts as a cash crop was a direct result of high demand (both domestically and in neighbouring countries); similarly, farmers in Ghana grew improved sorghum varieties for sale. Crop choices and input prices – in particular the price of fertilizer – influenced input use and SAI practices.

Access to credit and subsidies changed the availability and affordability of inputs and implements. In Ghana, subsidized tractor ploughing services and fertilizer have enabled the spread of these practices, even in relatively remote locations. However, farmers relying on loans for the purchase of external inputs whilst facing high levels of production and marketing risks (due to, for example, pest and disease attacks, droughts or low market prices) can be trapped in a vicious cycle of debt and coping strategies, as observed in Malawi (see also Mvula & Mulwafu, Citation2018).

Training and awareness raising by government and NGO programmes have introduced farmers to new technologies and practices, and provided varying degrees of technical support to them – via extension staff, lead farmers, ICTs, etc. At times these programmes introduced conflicting messages, depending on the visions of their funders and implementers. For example, in Ghana, tractor ploughing promoted by the government addresses climate risks to some extent but facilitates the expansion of agricultural lands into grazing areas and wood lots, and disincentivizes the protection and regeneration of trees under Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) initiatives.

Social organization of farmers (targeting, e.g., women, youths and poorer farmers) has been supported by development programmes, enabling them to access financial resources or support knowledge exchange.

In all sites, some attempts had been made by a range of development initiatives to raise awareness about sustainable agricultural development or support the adoption of intensification technologies – not always with a focus on social and environmental sustainability. This was done through awareness raising, training, free or subsidized inputs and other incentives. However, as these initiatives were primarily (donor-funded) project based, they were mostly short-lived and did not address the challenge of supporting farmers’ priority objectives in a way that avoided longer-term environmental or social costs. In all three countries, agricultural policies and donor support focused largely on short-term productivity increases, using, for example, subsidies for inorganic fertilizer as an incentive to increase its use, whilst not providing similar systematic support for measures that increase productivity in the longer term (e.g. soil and water conservation measures, integrated soil fertility management and FMNR). In Ghana, subsidies for inorganic fertilizer use takes up a large part of the agricultural budget, but these have not been economically viable, nor reached the poorest (Jayne et al., Citation2015).

Case study households varied in the extent to which they had direct contact with development organizations and programmes, with some farmers having benefitted from a series of interventions – sometimes with conflicting messages. In Burkina Faso and Ghana, approaches based on high levels of external inputs and on agroecological principles were both promoted by different organizations almost in parallel, whilst farmers in the Malawi sites had been exposed to various forms of conservation agriculture and climate-smart agriculture. These interventions left a mixed legacy: On the one hand, they exposed farmers to a range of options and opinions from which they could choose. On the other hand, they contributed to some confusion amongst farmers, in particular where implementing agencies had left the area and were not available for further advice.

Most case study farmers effectively combined advice received from previous programmes to support their own priority objectives. But this often meant that short-term (largely economic) benefits were prioritized over long-term (environmental and economic) ones, as in particular poorer farmers were unable to recalibrate objectives and invest in the future. This phenomenon of ‘lock-in’ was highlighted by the IPES Food report (2016).

Conclusion

The results of this study confirm that smallholders’ livelihoods and farming objectives are closely interlinked, i.e. individuals and households use, adapt and combine strategies that enable them to meet priority objectives. Within their existing context, farmers are largely making rational choices in managing trade-offs. They compromise on the extent to which objectives are met, by pursuing a mix of approaches that meet objectives to some extent. This is in stark contrast to the prevailing logic of SAI promotion, which relies heavily on the adoption of specific practices and technologies, often packaged in fixed strategies, to increase agricultural productivity, without considering the priorities of different types of farmers.

The farmers’ ability to succeed in managing competing objectives depends on the resources available to them and the wider socioeconomic, environmental and institutional context. Current agricultural policies and interventions are not well geared towards supporting long-term environmental and social objectives whilst also meeting farmers’ immediate needs. To achieve this would require changes in financial and technical support, in order to help poorer farmers in particular to make investments in assets and adopt practices that would provide benefits in the future. These practices could include long-term commitments to soil and water conservation, integrated soil fertility management, agroecological intensification, agroforestry, integrated pest management, appropriate mechanization and the development of institutions that can govern and support transformational processes. This would imply a shift away from an emphasis on the promotion of individual technologies or fixed packages, towards systematic changes in farming systems, in the wider agroecological landscapes and in rural communities.

Even without such support, farmers are already intensifying their agricultural production to adapt to a diminishing natural resource base in the face of population growth and climate change. The challenge is design and implement support to shift this intensification towards a more balanced approach, whereby long-term environmental impacts are identified and addressed rather than focusing on economic outcomes alone.Footnote4 Different types of farmers will require different types of support which will enable them to meet their own short-term objectives, whilst also contributing to longer-term goals relevant to not just their children, but the wider community. This will require support for synergistic practices that can address multiple objectives across sustainability domains and timescales. Identifying and optimizing synergies between land, trees and livestock in the farming system could go a long way in overcoming the dangerous ‘lock-ins’ that farmers find themselves in.

Enabling factors will need to operate at a system level to address the multiple challenges and opportunities. This requires long-term commitments from government, donors and development agencies, to overhaul agricultural subsidies, research and advisory systems that are currently mostly following neoliberal policies. It seems inappropriate to expect smallholders in some of the most deprived parts of sub-Saharan Africa to make enlightened choices that consider and ideally prioritize sustainability, whilst governments and development agencies focus on ‘quick wins’ within election or project cycles.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank farmers in the six research sites for their willingness to participate in this study. We are particularly grateful for the members of the case study households, who spent a substantial amount of time with the research team over nearly 18 months. Without their willingness and patience to explain their views and perceptions to us, this paper would not have written.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barbara Adolph

Dr. Barbara Adolph is a Principal Researcher with the International Institute for Environment and Development in London and has worked on sustainable agriculture in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa for nearly 30 years. Her main current interest is the transition of smallholder farming systems in Sub-Saharan Africa, so that they can deliver economic, social and environmental benefits to farmers and to wider society. Barbara co-leads the Food Systems Work Programme of IIED. She holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics and Social Sciences from the University of Hohenheim, Germany. Before joining IIED she worked with Triple Line Consulting in London and the Natural Resources Institute in Chatham, UK.

Mary Allen

Mary Allen has worked in West Africa for over 30 years to build sustainable livelihoods and strengthen community management of natural resources, notably as Director of SOS Sahel UK in Mali (1994–2005) and then Sahel Eco (2005–2013). Recruited by Practical Action in 2013, she successfully built up a new programme of work in West Africa and established the Regional office in Dakar. Since 2018 Mary works part-time as Senior Advisor Resilience and Livelihoods for Practical Action, leading work in West Africa to reduce the risk of climate hazards, such as floods and droughts, and minimise their impact on vulnerable people’s lives and livelihoods. Mary has skills in participatory action-research and learning, and has experience as Key Expert on assignments relating to agricultural information services, sustainable intensification of agriculture, the agriculture-energy nexus and empowerment of rural women entrepreneurs. She holds degrees in Environmental Science (Southampton) and Soil and Water Engineering (Silsoe College).

Evans Beyuo

Evans Beyuo is a BSc. degree holder in Agriculture Economics from the University for Development Studies in Wa, Ghana. He is currently studying for an MSc in Organizational Management at the College for Community and Organisational Development (CCOD)-Ghana. Evans is a former Teaching Assistant at the University for Development Studies, Nyankpala Campus, in the Agricultural Economics and Extension Department. He is currently an assistant agricultural officer with the Department of Agriculture, Nandom Municipal Assembly, Wa. He has interest in research and development.

Daniel Banuoku

Daniel Banuoku is the Deputy Executive Director of the Center for Indigenous Knowledge and Organisational Development. Daniel has over 20 year expertise in several interdisciplinary projects on Environment, Agroecology and Natural Resources Management. He is passionate about Indigenous Knowledge, Culture and Spirituality. His most recent works have been focused on promoting Endogenous Development and Food Sovereignty in Africa through research, advocacy and practice.

Sam Barrett

Dr. Sam Barrett is a researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development in London. He works on evaluations and value-for-money assessments of climate change adaptation projects and programmes, mainstreaming climate into development planning and decision-making, Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA), trade-offs in smallholder farmer decision-making, and private investment in community-based adaptation. He has a BA in Political Science and Economics from Trinity College, Dublin, an MSc in International Relations Theory from the London School of Economics, and a PhD in Human Geography from Trinity College, Dublin.

Tsuamba Bourgou

Tsuamba Bourgou is Groundswell’s Regional Coordinator for West Africa. Engaged in rural development projects and programs since 1993, his main interests are strengthening organisational capacities of farmers and their organisations, as well as community level participatory planning, monitoring and evaluation. Before joining Groundswell, Tsuamba served as the Executive Director of the NGO Association Nourrir Sans Détruire, where he played a critical role in the emergence of a dynamic agroecology and farmers’ movement in eastern Burkina. Tsuamba’s key areas of experience include adult education, action research, evaluation, impact assessment, strategic planning, program development, training and facilitation and strengthening local organizational capacities. He holds a Master degree in Linguistics. He participated in the management of several programs and projects that aimed at improving community food security, nutrition, and income in a healthy environment through sustainable agriculture and other livelihood strategies.

Ndapile Bwanausi

Ndapile Bwanausi is an independent consultant working in the environment and agriculture sector. With a BSc in Environmental Sciences from Bunda College, University of Malawi, she has worked with various institutions including the Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources. She is a 2019 Fellow of the United Nations University Land Restoration Programme, and her interests include Sustainable Agricultural Practices, Climate Change mitigation, and Climate-Smart Agriculture, Conservation Sciences, and Gender and women empowerment.

Francis Dakyaga

Francis Dakyaga is a PhD candidate at the TU-Dortmund, Germany. He works with the West African Centre for Sustainable Rural Transformation (WAC-SRT), as a Chief Research Assistant in the University for Development Studies, Ghana. He is a specialist in urban and Regional Development Planning, with focus on rural and urban development issues. He holds a Joint MSc. in Urban and Regional Development Planning and Management from TU-Dortmund and Ardhi University in Tanzania, and a B.A Integrated Community Development from the University for Development Studies, Ghana. His research focuses on urban planning, infrastructure, urban informalities, rural development, social services and climate change. He has been involved in several research grants and consultancy projects in both rural and urban areas in Africa.

Emmanuel K. Derbile

Dr. Emmanuel K. Derbile is an Associate Professor in Development Planning at the S.D Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, formerly, University for Development Studies, Wa, Ghana. He holds a Ph.D in Development Studies from the University of Bonn, Germany, an M.Sc. in Development Planning and Management from the University of Dortmund and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana, and a BA in Integrated Development Studies from the University for Development Studies, Ghana. He also holds a Certificate in Management of Development Organizations from the St. Francis Xavier University, Canada. He has over 20 years work experience in academia, spanning teaching, research and development extension. He has researched and published in areas of environmental change, especially vulnerability to climate change and the role of local knowledge systems and livelihoods in climate change adaptation planning.

Peter Gubbels

Peter Gubbels is Groundswell International’s Director of Action Learning and Advocacy for West Africa and is one of Groundswell’s co-founders. He has 38 years of experience in rural development, including over 28 years living and working in West Africa. Currently based in a village in northern Ghana, Peter provides action research and advocacy support to Groundswell’s partners who empower rural communities to build equitable and ecologically sound local economies, spread lasting solutions, and engage in wider coalitions for change. Peter was recently appointed senior fellow with the Global Evergreening Alliance. Peter has written numerous articles, research reports, evaluations, case studies and policy briefs on agroecology resilience to climate change, regreening, equity for food security, women’s empowerment in agriculture, nutrition, local governance, and how the transition to agroecology can be scaled out. A Canadian, Peter holds a college diploma in Agricultural Production and Management, an Honour’s degree in History from the University of Western Ontario and an MA in Rural Development from the University of East Anglia in the UK.

Batchéné Hié

Batchéné Hié has been The Executive Director of the Association Nourrir Sans Détruire since 2018 – an NGO that builds technical and organisational capacities of rural communities with the aim to assist their self-determination through advocacy and action research. He holds a Master’s degree in Environmental protection and improvement of Sahelian agricultural systems. Before joining ANSD, he was in charge of the programme on Water, Climate and Development, implemented by the African Ministers’ Council on Water. As programme coordinator, Batchéné has worked on climate change integration in national development planning with the aim to increase resilience of local communities. He also worked as Monitoring and Evaluation expert for the Ministry of Environment of Burkina Faso.

Chancy Kachamba

Chancy Kachamba works as a Research Assistant with Total Land Care in Malawi. He holds a Diploma in Agriculture and Environmental Management from Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resource (LUANAR). His interest is in agricultural research and development.

Godwin Kumpong Naazie

Godwin Kumpong Naazie was a Research Assistant at the University for Development Studies, Ghana, for the SITAM Project. Currently, he serves as a Research Assistant under the Nation Builders Corpse (NABCO) Programme by the Government of Ghana at the West Africa Centre for Sustainable Rural Transformation (WAC-SRT) of the Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies (SDD- UBIDS) – Ghana, formally Wa Campus of the University for Development Studies. He serves as a Research Associate in Endogenous Development Service (EDS) Ghana. He received a BA in Environment and Resource Management and a Master of Philosophy in Environment and Resource Management. His research focus is on Climate Change and Agriculture, Environmental Resource Management and Rural Development issues.

Ebenezer Betiera Niber

Ebenezer Betiera Niber holds a BA degree in Community Development from the University for Development Studies in Tamale, Ghana. He works as a field officer and facilitator with the Center for Indigenous Knowledge and Organisational Development (CIKOD) and is involved in action research on the value chain for livestock trade in West Africa and on conservation agriculture with smallholder farmers in the Upper West Region of Ghana. He is interested in life changing research and community work.

Isaac Nyirengo

Isaac Nyirengo is currently working as Technical Lead in Monitoring Evaluation Accountability and Learning (MEAL) for Total LandCare. Isaac has a Bachelor’s Degree in Computer Science from the University of Malawi. He has worked for different international development organisations such as Catholic Relief Services, John Snow Inc. as a MEAL technical lead and has extensive experience is conducting project evaluations, impact assessments, and action research. Isaac has contributed to development and promotion of community project monitoring tools and with special interest on Climate smart Agriculture and Natural Resource Management.

Samuel Faamuo Tampulu

Samuel Faamuo Tampulu works as a Programme Officer with the Center for Indigenous Knowledge and Organizational Development. He holds a BSc. Mathematics with Economics from the University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana. He works on livestock value chain/trading in West Africa, action research on smallholder farmers’ decisions (management of trade-offs) and agroecology. He is interested in economic modelling of natural resources for agricultural transformation, impact evaluation, and informed policies development for building resilient and sustainable communities. He has experience in Participatory Rural Appraisal as well as quantitative survey methods.

Alex-Fabrice Zongo

Alex-Fabrice Zongo, is a rural development engineer at the Institute of Environment and Agricultural Research (INERA) in Burkina Faso. He holds Master I in Agricultural and Environmental Economics from Norbert ZONGO University in Koudougou and a Master II in Rural Economy and Agribusiness from the Institute of Rural Development (IDR) of Bobo-Dioulasso. He has experience in facilitating the establishment of multi-actor platforms for innovation in the agricultural sector, promoting agricultural value chains through a co-creation of knowledge approach, research into the economics of agroecology, and training of technical personnel for the agricultural sector.

Notes

1 By ‘smallholder’ or ‘smallholder farmer’, we mean a person operating a family farm for both subsistence and cash purposes, relying mostly on family labour. The actual farm size varies considerable, depending on farming system and household size, and is therefore not a useful indicator (Boussard Citation1992). By ‘household’, we mean the unit of people living, cooking and operating a farm together. This does not exclude individual household members having individual control over a specific plot of land or other assets, such as livestock within the farm, or having off-farm income sources.

2 The environmental and social impacts of an over-reliance on maize as a staple food crop in Southern Africa has been well documented (Bandel and Nerger, Citation2018).

3 Other reasons not explored in the study, including local culture and traditions, are likely also to play a role in the men's decision to marry a second wife.

4 A recent study (Biovision, Citation2020) showed that as many as 85% of projects funded by the BMGF and more than 70% of projects carried out by Kenyan research institutes were limited to supporting industrial agriculture and/or increasing its efficiency via targeted approaches such as improved pesticide practices, livestock vaccines or reductions in post-harvest losses – with only a fraction supporting agroecological intensification.

References

- Adolph, B., Alhassan, Y., Bisanda, S., Kwari, J., Mekonnen, G., Warburton, H., & Williams, C. (1993). Coping with uncertainty: challenges for agricultural development in the Guinea Savannah Zone of the Upper West Region, Ghana. ICRA Working Document Series No. 28. ICRA (International Centre for development-oriented Research in Agriculture), Wageningen and Nyankpala Agricultural Experiment Station, Tamale.

- African smallholder farmers group (ASFG). (2013). Supporting smallholder farmers in Africa: A framework for an enabling environment. ASFG.

- Bandel, T., & Nerger, R. (2018). The true cost of maize production in Zambia’s Central Province. Discussion Paper. HIVOS, The Hague and IIED, London

- Biovision Foundation for Ecological Development and IPES-Food. (2020). Money flows: What is holding back investment in agroecological research for Africa? Biovision Foundation for Ecological Development and International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems.

- Boussard, J.-M. (1992). The impact of structural adjustment on smallholders. FAO Economic and Social Development Paper 103. FAO.

- Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future. The World Commission on environment and development. Oxford University Press.

- Byerlee, D., Stevenson, J., & Villoria, N. (2014). Does intensification slow crop land expansion or encourage deforestation? Global Food Security, 3(2), 92–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.04.001

- Carney, D. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods: What contribution can we make? DFID.

- Chambers, R. (1994). Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): challenges, potentials and paradigm. World Development, 22(10), 1437–1454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)90030-2

- Cook, S., Silici, L., Adolph, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Sustainable intensification revisited. IIED issue paper. IIED.

- FAO. (2011). Resilience analysis in Senegal. FAO resilience analysis no. 8. FAO.

- FEWS NET. (2016). Malawi Vulnerability Assessment Committee, livelihood baselines, national Overview report.

- Garnett, T., & Godfray, C. (2012). Sustainable intensification in agriculture: Navigating a course through competing food system priorities. Food climate research network and the Oxford Martin programme on the future of food. Oxford University.

- IPES-Food. (2016). From uniformity to diversity: A paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems.

- Jayne, T., Kolavalli, S., Debrah, K., Ariga, J., Brunache, P., Kabaghe, C., Nunez-Rodriguez, W., Baah, K.O., Bationo, A.A., Huising, E.J., Lambrecht, I., Diao, X., Yeboah, F., Benin, S., & Andam, K. (2015). Towards a sustainable soil fertility strategy in Ghana. Report submitted to the Ministry of food and agriculture government of Ghana. IFPRI.

- Klapwijk, C. J., van Wijk, M.T., Rosenstock, T.S., van Asten, P.J.A., Thornton, P.K., & Giller, K.E. (2014). Analysis of trade-offs in agricultural systems: Current status and way forward. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 6, 110–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.012

- Meijer, S. S., Catacutan, D., Ajayi, O.C., Sileshi, G.W., & Nieuwenhuis, M. (2014). The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. IJAS, 13(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2014.912493

- Musumba, M., Grabowski, P., Palm, C., & Snapp, S. (2017). Guide for the Sustainable Intensification Assessment framework. USAID/Feed the Future.

- Mvula, P., & Mulwafu, W. (2018). Intensification, crop Diversification, and gender relations in Malawi. In A. Andersson Djurfeldt, F. Mawunyo Dzanku, & A. Cuthbert Isinika (Eds.), Agriculture, Diversification, and gender in rural Africa. Longitudinal Perspectives from Six countries (pp. 158–175). Oxford University press.

- Perez, C., Jones, E.M., Kristjanson, P., Cramer, L., Thornton, P.K., Förch, W., & Barahona, C. (2015). How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Global Environmental Change, 34, 95–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.003

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681–695. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

- Rodenburg, J., Johnson, J.-M., Dieng, I., Senthilkumar, K., Vandamme, E., Akakpo, C., Allarangaye, M.D., Baggie, I., Bakare, S.O., Bam, R.K., Bassoro, I., Abera, B.B., Cisse, M., Dogbe, W., Gbakatchétché, H., Jaiteh, F., Kajiru, G.J., Kalisa, A., Kamissoko, N., … Saito, K. (2019). Status quo of chemical weed control in rice in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Security, 11, 69–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0878-0

- Royal Society. (2009). Reaping the benefits. Science and the sustainable intensification of global agriculture. RS policy document 11/09.

- Rusinamhodzi, L., et al. (2015). Maize crop residue uses and trade-offs on smallholder crop-livestock farms in Zimbabwe: Economic implications of intensification. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 214, 31–45 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.08.012

- Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820503

- Snyder, K. A., & Cullen, B. (2014). Implications of sustainable agricultural intensification for family farming in Africa: Anthropological perspectives. Anthropological Notebooks, 20(3), 9–29.

- Toulmin, C. (2020). Land, investment, and migration: 35 years of village life in Mali. OUP.

- Woltering, L., Fehlenberg, K., Gerard, B., Ubels, J., & Cooley, L. (2019). Scaling – from ‘reaching many’ to sustainable systems change at scale: A critical shift in mindset. Agricultural Systems, 176. 176102652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102652