ABSTRACT

In response to disruption to education during the COVID-19 pandemic, mobile phone-based messaging has emerged in some instances as an accessible, low-connectivity way of promoting interactivity. However, no recent reviews have been undertaken in relation to how social media and messaging apps can be used to effectively support education in low- and middle-income countries. In this scoping review, 43 documents were identified for inclusion, and three main thematic areas emerged: supporting student learning (including interacting with peers and other students, peer tutoring and collaborative learning; and interacting with teachers, through content delivery, teaching and assessment); teacher professional development (including structured support and prompts, and informal communities of practice); and supporting refugee education. The discussion and findings are both of practical use, to inform responses to the current pandemic and designing initiatives in the future, and will also be useful for advancing research in this expanding field.

Introduction

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, school closures have affected learners across the globe on an unprecedented scale. At the peak of school closures in early 2020, approximately 90% of school-aged learners were affected (Jordan et al., Citation2021). Adopting a combined approach of making educational content available through radio, television and online platforms has frequently been used, in order to maximise the number of learners which can be reached during school closures, across a range of levels of technology access and online connectivity, with greater use of broadcast media in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) (Vegas, Citation2020).

However, examples have emerged of using messaging apps (such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger or simply SMS) as a low-connectivity mechanism for educational content delivery, as part of countries’ crisis responses alongside broadcast instruction (World Bank, Citation2020). Levels of low-cost smartphone ownership have increased in recent years (McCrocklin, Citation2019), and in communities where smartphone ownership is low, there is a potential role of local facilitators and volunteers to act as a hub for the community (Sabates, Citation2020). The low data requirements are also key, being able to distribute digital resources by mobile network coverage. Resources can be downloaded when the phone owner has connectivity, and used offline later, in areas with low mobile coverage (Douse, Citation2020). Furthermore, messaging is likely being used in many more initiatives at localised levels – from teachers, to schools and districts – as individuals adapt to the current situation.

Crucially, in addition to providing a network for delivering teaching materials or communicating official information, messaging also has the advantage of interactivity. Provision of educational content by broadcast media can be supplemented with reminders and basic guidance for parents about activities to do with their children; messaging can also play a role in communication, support and motivation between teachers and other educational practitioners. Two examples of programmes where WhatsApp is currently being used to facilitate delivery of resources to teachers and support communication between teachers are the IGATE-T project in Zimbabwe (Power, Citation2020). In Sierra Leone and Liberia, the Rising Academy Network responded quickly to the crisis, repurposing existing content for use through radio, television and SMS in the ‘Rising on Air’ programme (Lamba & Reimers, Citation2020).

The adoption of messaging platforms such as WhatsApp for educational purposes during the COVID-19 crisis raises a question of what is currently known about how this medium can be used to effectively support education. However, no recent reviews have been undertaken into the research literature around messaging in education in LMICs. This review serves to address this gap; there is a risk that its use during the crisis will be led by the technology and not informed by previous research or effective practice. As it is prompted by school closures, the focus here is specifically upon how messaging may be used directly in relation to school-aged learners, and indirectly through teachers’ development. The study was guided by the following research questions:

What are the characteristics of the research literature published since 2010 about how messaging apps and related technology (including SMS and social media-based messaging) can be used to effectively support primary and secondary education in LMICs?

What are the main themes within the existing research literature?

Method

The study used a systematic scoping review approach. Scoping reviews are related to systematic reviews; both share a systematic, rigorous approach to searching and synthesis across the research literature (Pham et al., Citation2014). However, scoping reviews differ in that the goal is typically to profile the research landscape around a topic, and identify gaps, rather than evaluate the evidence in relation to a specific question (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Scoping reviews follow a protocol and are explicit in documenting the process of literature searching, screening, and the reasons why studies have been selected for inclusion.

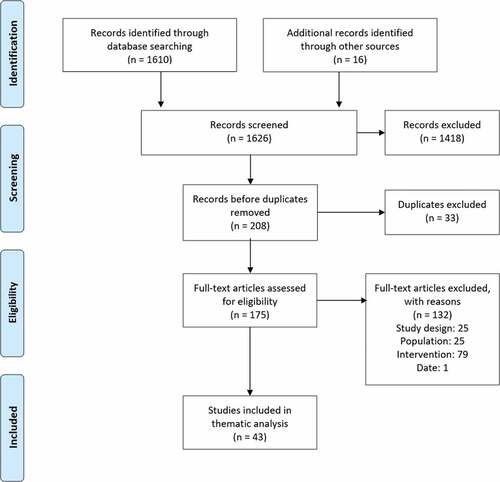

Literature searches were carried out in August 2020, using four of the main scholarly databases (ERIC, Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Knowledge) and the following search string: (”skype” OR ”telegram” OR ”whatsapp” OR ”social media” or ”sms” or ”text messag*” or ”facebook”) AND (”education” OR ”school”) AND (”africa” OR ”LMIC” OR ”developing world” OR ”developing countr*” OR ”ICT4D” OR ”global south” OR ”refugees”). The number of bibliographic records identified and the screening process are depicted in , based on the PRISMA framework for reporting literature reviews (Moher et al., Citation2009). The criteria for inclusion and exclusion are shown in .

Figure 1. Modified PRISMA flow chart depicting the processes for selection and inclusion of publications for the study (after Moher et al., Citation2009).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

During initial screening, the criteria were applied at the level of title and abstract. At the screen round, full texts were considered. The most frequent reasons for exclusion were a focus on health rather than education, or on higher education rather than school-aged learners or teachers. Further studies (particularly reports, and recently published works) were identified through snowball sampling, and recommendations from others. In total, 43 studies were included.

To address the first research question, the studies were categorised according to a range of characteristics. The second research question was addressed by analysing the studies thematically, to explore emergent trends in the literature. Given the exploratory nature of the inquiry, an a priori coding scheme was not used. Instead, an inductive approach to categorisation and thematic analysis was used, by examining prominent themes and clusters in the literature sample while bearing in mind the overall research question. Through this process, three major themes, two comprising two sub-themes, were identified (number of studies shown in brackets):

Supporting student learning

Content delivery, teaching and assessment (9)

Peer tutoring and collaborative learning (9)

Teacher professional development

Structured prompts and coaching (9)

Communities of practice (10)

Supporting education in refugee contexts (6)

Results and discussion

The most frequent article type within the sample are journal articles (23), followed by conference papers (13), working papers and reports (6) and book chapters (1). The distribution of articles within the sample according to publication year is shown in . More than half of the articles had been published within the past two years (28). The countries which were the focus of the articles are shown in .

Figure 2. Frequency of articles within the sample, according to publication year. Note that 2020 is incomplete as searches were undertaken in August.

Figure 3. Countries which are the focus of articles within the sample. The two most frequent countries are South Africa and Kenya, with 10 articles each.

The papers included in the sample include a range of research approaches (). Where specified, a range of sample sizes in terms of the number of participants were included. Note that for some of the papers reporting on online data mining, numbers of posts or interactions were given rather than number of participants, but these would suggest a large sample size.

Table 2. Frequency of research designs and sample sizes within the sampled papers.

Of the papers which addressed a specific grade or age group (23 did not), ten focused upon primary education (approximately up to age 12), nine on secondary education and one upon both. In terms of subject area, the most frequent focal areas were literacy (15 papers) and numeracy (nine papers). One paper focused on information technology and one on health, while 17 were not specific (mainly focused upon teachers).

The topics and content of the literature were examined in further detail by thematic analysis. In the following sections, the themes and studies which contributed to each theme are discussed.

Supporting student learning

The ‘supporting student learning’ theme includes studies in which technology was used to support interactions with – or between – learners. It comprises two sub-themes: peer tutoring and collaborative learning; and content delivery, teaching and assessment.

Peer tutoring and collaborative learning

In ‘peer tutoring’ models, messaging has been used as a communication medium between high school students and university undergraduates in relevant subjects in the role of tutor. One of the earliest studies included in the sample follows this model. From 2007, ‘Dr Math’ connected South African pupils to undergraduate student tutors via the mobile phone-based Mxit messaging platform (Butgereit et al., Citation2010), and expanded from mathematics to include other STEM subjects (Beyers & Blignaut, Citation2015). Although no evaluations of its effect on learning outcomes were found, Dr Math peaked at 37,000 users in 2013, but ceased operations after this as use of the host Mxit platform declined (Budree & Hendriks, Citation2019).

Findings from a recent survey of learners in South Africa suggest that there is still a potential role for similar peer-tutoring platforms, with a preference for WhatsApp. Referring to the experiences of Dr Math, the authors recommend materials should be designed in ways which supported repurposing to be run through different platforms (Budree & Hendriks, Citation2019). Taking a lead from Dr Math, Campbell (Citation2019) reported on a WhatsApp-based project which connected groups of five South African high school students to undergraduate tutors. Tutees could submit mathematics questions when encountering difficulties with homework problems, and they were also sent messages to improve motivation and aspirations for higher education. Although the effects on learning outcomes and longer-term impacts were not assessed, the project drew upon a range of data types using an iterative development process and determined several key design principles for facilitating peer tutoring. These included considering communication and organisation; scaffolding, error management and cognitive conflict; and emotional factors that influence learning (Campbell, Citation2019).

‘Collaborative learning’ includes studies where the connection is focused upon group activities and discussions between learners of a similar age. However, along with peer tutoring, small-scale studies form the research base and there is little evidence linking to learning outcomes, so this area would benefit from further research. Similar to peer tutoring, there is a focus upon maths, but studies also address other subject areas, including English and Health. Jere et al. (Citation2019) reported on the experiences of a single WhatsApp-based study group, comprising 10 South African Grade 12 learners and one mathematics teacher. Communication within the group was unstructured, and findings suggested positive experiences of collaborative learning, sharing resources and extending educational time beyond the classroom. In a small-scale experimental design reported by Çetinkaya (Citation2019), WhatsApp was used to support a problem-based learning activity for Grade 9 Maths students in Turkey. The group which received the intervention – a WhatsApp group and a virtual stock exchange app – outperformed the learners in the control group in the post-test. Furthermore, feedback from students showed that perceived benefits included flexibility in terms of when and where to learn, sharing resources and organising activities (Çetinkaya, Citation2019).

Focusing upon on English as a subject area, Rwodzi et al. (Citation2020) presented a case study of the experiences of 6 teachers and 12 learners using WhatsApp (and other social media) in a South African school; similar to other studies, perceived benefits include building group communication and being able to use multiple modalities to communicate and share information. Suhaimi et al. (Citation2019) examined the use of WhatsApp to support a structured activity (the ‘Curriculum Cycle’) with eight Grade 6 primary learners in Malaysia. Although students showed an increase in test scores post-intervention, the sample was too small to be conclusive.

While not focused on academic subjects, Della Líbera and Jurberg (Citation2020) presented a study which is notable in that it was an initiative for supporting visually impaired students. Using mobile devices equipped with assistive technology, WhatsApp was used to facilitate discussions on a range of health-related topics within a group of 13 students and three teachers in Brazil. Although the impacts were not evaluated, the initiative provides proof-of-concept; over the course of 11 weeks, the group successfully held discussions on a range of topics, with varying levels of individual engagement.

Content delivery, teaching and assessment

This sub-theme includes examples where learners interact with teachers, directly or indirectly. Messaging may be used as a medium to distribute educational materials, and also in activities which allow students to interact with teachers.

The MobiLiteracy Uganda Program is a significant example of delivering educational content at scale via messaging (Pouezevara & King, Citation2014). A total of 168 parents, with children in Grades 1 and 2, took part in the programme and were assigned to one of three groups (content delivered daily by mobile phone; content delivered as paper copies; or control group, receiving a single, verbal message). Parents played a key role as educator in this model, which is particularly important to note for reaching younger learners and highly relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic. Both groups which received the intervention showed increased learning gains in comparison with the control group, and no significant differences were found between paper and mobile-based delivery. Additionally, the material did empower parents to actively support their children’s education (Pouezevara & King, Citation2014). A smaller-scale example compared delivery of content through WhatsApp and textbooks with English students in Iran and found no significant difference in test scores between the two groups (Dehghan et al., Citation2017). The comparable impacts of different media in both studies suggest that paper-based resources may be cheaper but just as effective; however, messaging may bring other affordances over printed materials alone, such as ease of delivery.

The role of parents and caregivers is a key part of any intervention supporting education in the context of home rather than school. Simple text-message-based reminders have demonstrated improvements in promoting reading with young children in HICs (York et al., Citation2018). Madaio et al. (Citation2019) considered how such interventions could be adapted for low-literacy caregivers, through interviews with parents in Côte d’Ivoire. Parents are keen to be involved and already support their children’s literacy development, although levels of literacy vary, and they expressed a preference for French. The authors make practical suggestions for designing potential interventions, including drawing on culturally relevant examples for activities, and designing for interaction and support with a wider group than parents alone, such as siblings and other peers (Madaio et al., Citation2019).

Student–teacher interactions through messaging have been the subject of several large-scale analyses. Although the studies included in their review fall outside of the time period for inclusion in the analysis here, Valk et al. (Citation2010) reviewed several early mobile learning-based pilot studies in LMICs in Asia, several of which used SMS for assessment. The earliest study in this sub-theme presents findings from an EdTech intervention undertaken with 24 schools in Pakistan. While the main form of technology used was satellite-linked tablet computers, SMS were used to communicate the results of learners’ assessments to parents, community workers and educational administrators (Zualkernan et al., Citation2014).

Assessment, such as multiple-choice practice questions, can potentially be automated. Poon et al. (Citation2019) evaluated a system of practice exam questions posed to Cameroonian high school students, via WhatsApp and SMS. Correct answers, feedback and further questions were provided in response. Although learning outcomes were not measured, benefits to students included being prompted to study, including discussing the quizzes with their peers as a result. Limitations included the extent to which content matched the curriculum, unfamiliarity interacting with automated messaging, and the need to design systems which users (and phone gatekeepers) will trust (Poon et al., Citation2019).

An example of large-scale research undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic, Angrist, Bergman, Brewster, et al. (Citation2020) presented a randomised control trial of an intervention using phone calls and SMS messages to support education during school closures in Botswana. A total of 4500 families with children in Grades 3 to 5 were assigned to one of three groups: sent SMS-based numeracy ‘problems of the week’; sent SMS and also support phone calls to discuss the problems; or a control group. Both interventions resulted in significant learning gains and increased parental engagement, with those receiving SMS and a phone call showing greater improvement than SMS alone (Angrist, Bergman, Brewster, et al., Citation2020). However, the endline results (published after the literature search was undertaken) show that the effects of the SMS-alone intervention fade over time (Angrist, Bergman, & Matsheng, Citation2020).

Although the discussion so far within this sub-theme has considered content delivery and teacher support separately, both can be combined through SMS, which is the model used by Eneza Education and its ‘Shupavu291’ product. Shupavu291 is a mobile phone-based educational platform which provides learners with curriculum-linked educational materials and quizzes, and allows users to submit questions to teachers, via SMS. Large-scale data collected from Kenyan Shupavu291 users through the platform have provided the basis for three papers which used data mining to examine patterns within student engagement, and possible predictors of success. Chen and Kizilcec (Citation2020) examined patterns of disengagement and re-engagement with the platform; similar to engagement with Massive Open Online Courses, a large proportion of learners initially log in but then disengage with the platform. However, Shupavu291 users are more likely to resume use at a later date (Chen & Kizilcec, Citation2020). Kizilcec and Chen (Citation2020) examined usage patterns in further detail through a thorough statistical analysis of interactions with the platform. As Shupavu291 content is aligned to the curriculum, use varies according to the school year; higher levels of activity are associated with self-directed study in school holidays and in preparation for examinations. While the study provides insights into how the platform is used to complement formal schooling, the authors did not find evidence to suggest that use of the platform is associated with enhanced learning outcomes (Kizilcec & Chen, Citation2020). Kizilcec and Goldfarb (Citation2019) combined interaction log data with survey responses from 942 users to examine whether personal characteristics can be used to predict student success. Factors associated with higher quiz scores included: possessing a stronger growth mindset; gender (higher quiz scores associated with female students); higher school grades; and greater satisfaction with the learning environment (Kizilcec & Goldfarb, Citation2019).

Teacher professional development

The second major theme is the use of messaging to support teacher professional development (TPD), and it comprises two sub-themes: structured prompts and coaching, which represents a more formal use of messaging for TPD; and communities of practice, which are often less formal, peer networks of teachers.

Structured prompts and coaching

Studies within this sub-theme show how messaging can be used as part of simple, effective strategies to enhance teachers’ practices and motivation. The earliest study within this sub-theme focuses upon ‘English in Action’, a professional development programme for English teachers in Bangladesh (Power et al., Citation2012). The main purpose of the intervention was to distribute materials to teachers via mobile devices and pre-loaded SD cards; additionally, the use of SMS messaging as a way of prompting reflection was piloted. However, the lack of support from mobile phone providers for Bangla-language SMS, and the character limits at the time, limited the efficacy of messaging.

Similarly, the SMS Story initiative used SMS to deliver daily content, including stories and lesson plans, to English teachers, initially in Papua New Guinea with 42 Grade 1 and 2 teachers across 20 schools in remote areas. Data collected mid-intervention showed an increase in a range of classroom practices. The evaluation highlighted practical design considerations including reducing the costs of mass SMS; timing of sending messages earlier, so teachers have more time to prepare; and ways to incorporate a wider range of media (Kaleebu et al., Citation2013). Learning outcomes were not assessed; however, the model was subsequently replicated in India (Pratham & VSO, Citation2015). Over 2400 students, from Grades 4 to 8, across 50 schools, participated in the study, including an intervention and a control group for comparison. Pupils in the intervention group were found to have increased gains on a range of reading measures, compared to the control group. Recommendations for future development included: developing stories and lesson plans tailored to different local settings; incorporating more textbook materials into the stories; and considering a wider range of technology (such as WhatsApp) (Pratham & VSO, Citation2015).

Two studies focus on professional development for educational leaders. The ‘Leadership for Learning’ programme was undertaken in Ghana and used SMS messages via Skype as a way to communicate with the cohort of 175 participants (Swaffield et al., Citation2013). Messages sent via Skype included announcements, prompts, feedback requests and sharing participant responses. Although the study did not evaluate the impact of the activity on participants’ learning or practice, the levels of engagement and discussion were promising. Also focused on educational leadership training in Ghana, Brion (Citation2019) reported on an initiative using a WhatsApp group with 23 participants following short face-to-face training sessions. Conversation triggers were sent to the participants as a group in order to sustain discussion about the training after the sessions, and evaluated by interviews with participants who reported benefits including being reminded about the training contents, networking, enhanced motivation and peer learning (Brion, Citation2019).

Two further studies provide robust evidence that using messaging as part of a blended approach provides contact and continuity between face-to-face sessions. The Health and Literacy Intervention project had an overall goal of improving literacy in Grades 1 and 2 at government schools in Kenya, part of which included activities undertaken with teachers (Jukes et al., Citation2017). Teachers were supported through three activity types: provision of sequential semi-scripted lesson plans; a three-day training workshop for teachers; and continued support for two years, by text messaging. The efficacy of the intervention was measured using a cluster randomised controlled trial research design, across a substantial sample (101 schools, half assigned to control and half to the intervention, equating to approximately 2500 children in total). Literacy-related outcomes were measured using a range of educational assessments, and classroom observations and interviews with teachers were also conducted. The analysis showed that the intervention led to a change in classroom practices and sustained positive impacts in terms of most of the measures of children’s literacy after two years, with greater benefits for girls (Jukes et al., Citation2017).

SMS was also used to support continued development after training sessions as part of the Malawi Early Grade Reading Activity project (Kipp, Citation2017; Slade et al., Citation2018), as a cost-effective, scalable way to maintain coaching of teachers between sessions. Over a period of six weeks following training, at least three messages were sent to teachers per week, on topics including teaching practices, student behaviour and motivation (Slade et al., Citation2018). The study also presents a discussion about the relative cost-effectiveness of SMS. Although early results suggested that the SMS campaign had a positive impact (Kipp, Citation2017), the efficacy of the SMS intervention was, however, inconclusive, owing in part to the fact that a number of the teachers receiving the messages then shared them with others (Slade et al., Citation2018).

The use of messaging alongside TPD needs to be designed for meaningful interactivity, however. In contrast to the other examples, Mtebe et al. (Citation2015) presented a study in which SMS-based quizzes were used to assess teachers’ subject knowledge, following a training programme. Based in Tanzania, 486 teachers took part over a period of eight weeks. Few teachers scored highly, and most of the participants disagreed that the initiative had improved their knowledge and skills, and was convenient or enjoyable. This is attributed in part to technical issues around reliability of receiving SMS on time, and limitations of the format (Mtebe et al., Citation2015). Assessment alone, without feedback and support, may not be an effective use of the technology.

Communities of practice

This sub-theme is distinct from the previous section in that the examples here focus on communication within groups of teachers, often to share experiences and reflect upon their practice. Initiatives in this category may still be part of TPD training, but in contrast to the previous sub-theme, use is free-form and not structured. In contrast to the previous sub-theme, studies here tend to offer smaller scale and more localised examples; while generally beneficial, there is less evidence for potential to scale effectively.

Ndlovu and Hanekom (Citation2014) evaluated an intervention which used WhatsApp in order to compensate for the lack of interactivity in primarily telematic TPD sessions at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Seventy-three STEM trainee teachers participated; qualitative analysis of conversations and feedback suggests that the intervention was an effective way of building teachers’ subject and pedagogical knowledge, and networking between teachers (Ndlovu & Hanekom, Citation2014).

Also focused on trainee teachers in South Africa, Mabaso and Meda (Citation2019) presented a small-scale qualitative analysis of a WhatsApp group comprising two lecturers and 16 students. In addition to being a channel for logistical course-related information, it was also perceived to be useful in collaborative learning, and providing students with a further way to discuss their course with the lecturers (Mabaso & Meda, Citation2019). The perceived value of contact and interaction with lecturers is highlighted by Habibi et al. (Citation2018), in their study of 42 student teachers’ use of social networking tools (including WhatsApp and Telegram, as messaging services) in Indonesia, while undertaking teaching practice.

Moodley (Citation2019) offered a further example of how WhatsApp can be used to build communities alongside formal TPD, with a group of 18 teachers in a rural part of South Africa. The group actively discussed curriculum and assessment issues and demonstrated the potential of WhatsApp for continued monitoring of in-service teachers, particularly in rural areas. Issues of TPD may be particularly important in rural areas, where teacher shortages may be more acute than in urban areas, and there may be fewer opportunities for TPD. The use of WhatsApp was part of a wider professional development and monitoring programme (the ‘AmritaRITE’ programme) in rural India (Nedungadi et al., Citation2018). The programme combined the use of remote teacher monitoring through specialised apps with use of WhatsApp ’to send photos and text regarding daily attendance, assessment records, activities like yoga, community services etc’. (Nedungadi et al., Citation2018, p. 120). A total of 8968 WhatsApp messages from 26 participants were used for the analysis, which showed that discussion topics aligned with the project’s goals of enhancing attendance, teacher empowerment and community engagement (Nedungadi et al., Citation2018). Further examples of the potential for messaging apps and social media to foster informal professional networks can be found in Pakistan, Bhutan (Impedovo et al., Citation2019) and India (Wolfenden et al., Citation2017). Both also highlight the link between networks and sharing of Open Educational Resources.

Much larger informal communities can be better supported by other forms of social media, as messaging groups are not open to organic internet traffic in the way that Facebook groups are, for example. Bett and Makewa (Citation2020) illustrated how Facebook groups can be used for similar purposes – to build support and enhance subject and pedagogical knowledge – at a much larger scale. It is also worth noting that online community groups can also benefit caregivers of children with special educational needs; for example, Cole et al. (Citation2017) examined the use of a WhatsApp group to support caregivers of children with autism in South Africa. It is worth noting, however, that different messaging tools can have different affordances in this context. Sun et al. (Citation2018) provided a comparison of different tools (discussion posts via Moodle, or messaging via WeChat) used in a learning activity intended to promote communication and interaction between 78 pre-service teachers in China. While Moodle use was found to be associated with a greater degree of collaborative learning and knowledge exchange, greater social interaction occurred via WeChat (Sun et al., Citation2018).

Supporting education in refugee contexts

A small but distinct group of papers focuses on education in refugee contexts. Papers within this group are diverse – including refugee students and teachers, within refugee camps and destinations. The use of messaging in this group of papers highlights how it can play a role in supporting education in usually hard-to-reach settings. This is also an emergent area for research, with all the papers being published within the past three years.

WhatsApp played a key role in delivering course materials to student teachers in the Dabaab Refugee Camp in Kenya. The Borderless Higher Education for Refugees project changed its delivery model from using a standard LMS, to a combination of WhatsApp and WordPress blogs, as students primarily used WhatsApp for communication (Sork & Boskic, Citation2017). Mendenhall (Citation2017) reported on a collaborative TPD programme led by a team at the Teachers College at Columbia University (USA) to support teachers in the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. A hundred and thirty teachers took part in the programme, which included teacher training workshops, peer coaching (of groups of other teachers) and mobile mentoring (connecting individual teachers with mentors in the USA). The combination of elements reflects findings in relation to the TPD section, discussed earlier. The programme was regarded as successful; see Mendenhall (Citation2017) for a full discussion of the outcomes, and challenges, of the programme. Use of WhatsApp was a key part of the mobile mentoring part of the programme; analysis of the messages reveals a wide range of topics for discussion and support, with main themes being pedagogy; child protection, wellbeing and inclusion; teacher’s role and wellbeing; and curriculum and planning (Mendenhall, Citation2017).

Two further studies address of the use of WhatsApp by student teachers in refugee camps and the types of interaction and discussion supported by the technology in this context. Dahya et al. (Citation2019) focused on the use of WhatsApp and SMS to support discussions with peers (other teachers) and international instructors (based in Canada). The analysis also suggests that women are more likely than men to make use of this form of support, and as such it may promote gender equity (Dahya et al., Citation2019). Motteram et al. (Citation2020) focused upon a WhatsApp group used by 27 Syrian English teachers within the Zataari refugee camp in Jordan, as part of a course run by the British Council. The analysis reveals similarity with chats with international mentors, but with greater emphasis on peer learning and shared experiences:

the WhatsApp group contributed to the teachers’ English language knowledge, provided a platform for them to share and discuss issues related to the challenges of their particular context, enabled them to contribute to the development of some teaching materials and begin to address some of the issues they had in a meaningful way. (Motteram et al., Citation2020, p. 5731)

Fewer papers in this category have focused on the perspectives of refugee learners. Working with youths in the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, Bellino and the Kakuma Youth Research Group (Citation2018) described a novel research process, using ethnography and participatory action research, to co-develop a social media platform to support the educational and social support needs of young people within the camp. Linked to the earlier theme of peer tutoring, Shekaliu et al. (Citation2018) presented an analysis of a large Facebook group run by a volunteer organisation in Malaysia, ‘Let’s tutor a refugee child’. Note that while this study reports on the use of social media to support refugees who have arrived in an upper-middle income country, there is a larger body of work focusing on similar support for refugees within HICs (not within the scope of this review).

Conclusions

This review has provided an overview of the academic literature focused upon the use of mobile phone-based messaging – including basic SMS, and messaging through social media and apps – to support education of school-aged learners in LMICs. As a literature review approach, a scoping review has advantages in terms of being transparent and reproducible; however, it also has limitations. The search strategy sets the bounds for the review, and necessarily excludes some potential searches outside of the inclusion criteria. While a focus on searching academic databases ensures that articles have been peer-reviewed, this also excludes grey literature. This was mitigated to some extent by snowball sampling and recommendations. Nonetheless, the trends in the literature suggest that this is a topic around which there is growing interest, and this review will help move the field forward.

The articles reviewed suggest that the use of messaging can have positive effects for education in LMICs, and the findings have practical implications for educators during the current crisis and beyond. The review also reveals gaps for future research. Longer-term impacts and effects upon learning outcomes are rarely considered. Detailed consideration of the issue of safeguarding was notably lacking across the sample. By focusing on published academic research, the review does not draw upon projects which are currently in progress and have not had findings published yet. Given the shift to remote and distance education necessitated by the pandemic, there is likely to be further research on this topic published in the future. While the studies here all suggest that the use of messaging has good potential for promoting a range of positive outcomes for education in LMICs and times of crisis, both for learners and teachers, further robust evidence is required to take the principles demonstrated in small-scale studies to larger programmes at scale.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken through EdTech Hub (http://www.edtechhub.org), and is funded by the UK government (Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, previously Department for International Development). The author would like to thank Joel Mitchell for assistance with literature screening and advice in relation to refugee education, and Dr Kalifa Damani and Dr Alison Buckler for their feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. An earlier version of the paper had been made openly available through the EdTech Hub website as a rapid evidence review for policymakers as part of its COVID-19 emergency response (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4058181).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katy Jordan

Katy Jordan is a senior research associate at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. She is part of FCDO-funded EdTech Hub, the world’s largest educational technology research programme, and principal investigator for one of the Hub’s current research projects. Her research interests focus on the use of technology to support education in a range of contexts. She has published research on projects including digital scholarship, social media in higher education, massive open online courses, and technology and equity.

References

- Angrist, N., Bergman, P., Brewster, C., & Matsheng, M. (2020). Stemming learning loss during the pandemic: A rapid randomized trial of a low-tech intervention in Botswana. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3663098

- Angrist, N., Bergman, P., & Matsheng, M. (2020). School’s out: Experimental evidence on limiting learning loss using “low-tech” in a pandemic. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3735967

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bellino, M. J., & the Kakuma Youth Research Group. (2018). Closing information gaps in Kakuma refugee camp: A youth participatory action research study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3–4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12277

- Bett, H., & Makewa, L. (2020). Can Facebook groups enhance continuing professional development of teachers? Lessons from Kenya. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 48(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1542662

- Beyers, R., & Blignaut, S. (2015). Going mobile: Using SNSs to promote STEMI on the backseat of a taxi across Africa. In T. H. Brown & H. J. van der Merwe (Eds.), The mobile learning voyage – From small ripples to massive open waters (pp. 99–110). Springer International Publishing.

- Brion, C. (2019). Keeping the learning going: Using mobile technology to enhance learning transfer. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 18(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-018-09243-0

- Budree, A., & Hendriks, T. (2019). Instant messaging tutoring: A case of South Africa. Proceedings of the ninth International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science and Engineering (Confluence 2019), IEEE (pp. 615–619). https://doi.org/10.1109/CONFLUENCE.2019.8776928

- Butgereit, L., Leonard, B., Le Roux, C., Rama, H., De Sousa, M., & Naidoo, T. (2010). Dr Math gets MUDDY: The ‘dirt’ on how to attract teenagers to mathematics and science by using multi-user dungeon games over Mxit on cell phones. Proceedings of IST-Africa 2010, IEEE (pp. 1–9). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5753031

- Campbell, A. (2019). Design-based research principles for successful peer tutoring on social media. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 50(7), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2019.1650306

- Çetinkaya, L. (2019). The effects of problem based mathematics teaching through mobile applications on success. Egitim ve Bilim, 44(197), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.15390/EB.2019.8119

- Chen, M., & Kizilcec, R. F. (2020). Return of the student: Predicting re-engagement in mobile learning. Proceedings of the13th International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM 2020) (pp. 586–590). https://educationaldatamining.org/files/conferences/EDM2020/papers/paper_95.pdf

- Cole, L., Kharwa, Y., Khumalo, N., Reinke, J. S., & Karrim, S. B. S. (2017). Caregivers of school-aged children with autism: Social media as a source of support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(12), 3464–3475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0855-9

- Dahya, N., Dryden Peterson, S., Douhaibi, D., & Arvisais, O. (2019). Social support networks, instant messaging, and gender equity in refugee education. Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 774–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1575447

- Dehghan, F., Rezvani, R., & Fazeli, S. A. (2017). Social networks and their effectiveness in learning foreign language vocabulary: A comparative study using WhatsApp. CALL-EJ, 18(2), 1–13. http://callej.org/journal/18-2/Dehghan-Rezvani-Fazeli2017.pdf

- Della Líbera, B., & Jurberg, C. (2020). Communities of practice on WhatsApp: A tool for promoting citizenship among students with visual impairments. The British Journal of Visual Impairment, 38(1), 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264619619874836

- Douse, R. (2020). Will Covid-19 widen the digital divide? UKFIET. https://www.ukfiet.org/2020/will-covid-19-widen-the-digital-divide/

- Habibi, A., Mukinin, A., Riyanto, Y., Prasohjo, L. D., Sulistiyo, U., Sofwan, M., & Saudagar, F. (2018). Building an online community: Student teachers’ perceptions on the advantages of using social networking services in a teacher education program. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 19(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.382663

- Impedovo, M. A., Malik, S. K., & Kinley, K. (2019). Global South teacher educators in digital landscape: Implications on professional learning. Research on Education and Media, 11(2), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.2478/rem-2019-0018

- Jere, N. R., Jona, W., & Lukose, J. M. (2019). Effectiveness of using WhatsApp for Grade 12 learners in teaching mathematics in South Africa. Proceedings of 2019 IST-Africa Week Conference, IEEE (pp. 1–12). https://doi.org/10.23919/ISTAFRICA.2019.8764822

- Jordan, K., David, R., Phillips, T., & Pellini, A. (2021). Educación durante la crisis de COVID-19: Oportunidades y limitaciones del uso de Tecnología Educativa en países de bajos ingresos. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 21(65). https://doi.org/10.6018/red.453621

- Jukes, M. C. H., Turner, E. L., Dubeck, M. M., Halliday, K. E., Inyega, H. N., Wolf, S., Zuilkowski, S. S., & Brooker, S. J. (2017). Improving literacy instruction in Kenya through teacher professional development and text messages support: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(3), 449–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2016.1221487

- Kaleebu, N., Gee, A., Maybanks, N., Jones, R., Jauk, M., & Watson, A. H. A. (2013). SMS story: Early results of an innovative education trial. DWU Research Journal, 19, 50–62. https://epsp-web.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/doc_KaleebuGeeMaybanksJonesJaukWatsonSMSStory.pdf

- Kipp, S. (2017, March). Low-cost, familiar tech for teacher support: Evidence from a SMS campaign for early grade teachers in Malawi. Presentation at CIES2017, Atlanta, GA. https://shared.rti.org/content/low-cost-familiar-tech-teacher-support-evidence-sms-campaign-early-grade-teachers-malawi

- Kizilcec, R. F., & Chen, M. (2020). Student engagement in mobile learning via text message. Proceedings of the seventh ACM Conference on Learning@Scale, ACM (pp. 157–166). https://doi.org/10.1145/3386527.3405921

- Kizilcec, R. F., & Goldfarb, D. (2019). Growth mindset predicts student achievement and behavior in mobile learning. Proceedings of the sixth ACM Conference on Learning@Scale, ACM (pp. 1–10). https://doi.org/10.1145/3330430.3333632

- Lamba, K., & Reimers, F. (2020). Sierra Leone and Liberia: Rising academy network on air. World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/182171599124695876/pdf/Sierra-Leone-and-Liberia-Rising-Academy-Network-on-Air.pdf

- Mabaso, N., & Meda, L. (2019). WhatsApp utilisation at an initial teacher preparation programme at a university of technology in South Africa. Proceedings of Teaching and Education Conferences. https://ideas.repec.org/p/sek/itepro/8410560.html

- Madaio, M. A., Tanoh, F., Seri, A. B., Jasinska, K., & Ogan, A. (2019). ‘Everyone brings their grain of salt’: Designing for low-literate parental engagement with a mobile literacy technology in Côte d’Ivoire. 2019 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’19) proceedings, ACM (pp. 1–15). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300695

- McCrocklin, S. (2019). Smartphone and mobile internet penetration in Africa and globally. GeoPoll. https://www.geopoll.com/blog/smartphone-mobile-internet-penetration-africa/

- Mendenhall, M. (2017). Strengthening teacher professional development: Local and global communities of practice in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya. Education in Crisis and Conflict Network. https://www.eccnetwork.net/resources/strengthening-teacher-professional-development

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moodley, M. (2019). WhatsApp: Creating a virtual teacher community for supporting and monitoring after a professional development programme. South African Journal of Education, 39(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n2a1323

- Motteram, G., Dawson, S., & Al-Masri, N. (2020). WhatsApp supported language teacher development: A case study in the Zataari refugee camp. Education and Information Technologies, 25, 5731–5751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10233-0

- Mtebe, J. S., Kondoro, A., Kissaka, M. M., & Kibga, E. (2015). Using SMS mobile technology to assess the mastery of subject content knowledge of science and mathematics teachers of secondary schools in Tanzania. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 9(11), 3893–3901. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1110101

- Ndlovu, M., & Hanekom. (2014). Overcoming the limited interactivity in telematic sessions for in-service secondary mathematics and science teachers. 6th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (EDULEARN14) proceedings (pp. 3725–3735).

- Nedungadi, P., Mulki, K., & Raman, R. (2018). Improving educational outcomes & reducing absenteeism at remote villages with mobile technology and WhatsApp: Findings from rural India. Education and Information Technologies, 23(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9588-z

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwena, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Poon, A., Giroux, S., Eloundou-Enyegue, P., Guimbretiere, F., & Dell, N. (2019). Engaging high school students in Cameroon with exam practice quizzes via SMS and WhatsApp. 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’19) proceedings, ACM (pp. 1–13). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300712

- Pouezevara, S., & King, S. (2014). MobiLiteracy-Uganda program phase 1: Endline report. RTI International.

- Power, T. (2020). Activating local study-groups for children’s learning – An equitable EdTech response? EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org/2020/05/29/activating-local-study-groups-for-childrens-learning-an-equitable-edtech-response/

- Power, T., Shaheen, R., Solly, M., Woodward, C., & Burton, S. (2012). English in action: School based teacher development in Bangladesh. The Curriculum Journal, 23(4), 503–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2012.737539

- Pratham & VSO. (2015). SMS story project: Impact assessment report. Pratham Education Foundation & Voluntary Service Overseas. https://www.vsointernational.org/sites/default/files/sms_report_final_v1_4.pdf

- Rwodzi, C., De Jager, L. J., & Mpofu, N. (2020). The innovative use of social media for teaching English as a second language. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 16(2), a702. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.702

- Sabates, R. (2020). Think local: Support for learning during COVID-19 could be found from within communities. UKFIET. https://www.ukfiet.org/2020/think-local-support-for-learning-during-covid-19-could-be-found-from-within-communities/

- Shekaliu, S., Binti Mustafa, S. E., Adnan, H. B. M., & Guajardo, J. (2018). The use and effectiveness of Facebook in small-scale volunteer organisation for refugee children’s education in Malaysia. SEARCH (Malaysia), 10(1), 53–78. https://fslmjournals.taylors.edu.my/the-use-and-effectiveness-of-facebook-in-small-scale-volunteer-organisation-for-refugee-childrens-education-in-malaysia/

- Slade, T. S., Kipp, S., Cummings, S., & Nyirongo, K. (2018). Short message service (SMS)–based remote support and teacher retention of training gains in Malawi. In S. Pouezevara (Ed.), Cultivating dynamic educators: Case studies in teacher behavior change in Africa and Asia (pp. 131–167). RTI International. https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2018.bk.0022.1809

- Sork, T., & Boskic, N. (2017). Technology, terrorism and teacher education: Lessons from the delivery of higher education to Somali refugee teachers in Dadaab, Kenya. International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED) proceedings (pp.64–68). https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2017.0121

- Suhaimi, N. D., Mohamad, M., & Yamat, H. (2019). The effects of WhatsApp in teaching narrative writing: A case study. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 7(4), 590–602. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2019.7479

- Sun, Z., Lin, C.-H., Wu, M., Zhou, J., & Luo, L. (2018). A tale of two communication tools: Discussion-forum and mobile instant-messaging apps in collaborative learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(2), 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12571

- Swaffield, S., Jull, S., & Ampah-Mensah, A. (2013). Using mobile phone texting to support the capacity of school leaders in Ghana to practise Leadership for Learning. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103, 1295–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.459

- Valk, J.-H., Rashid, A. T., & Elder, L. (2010). Using mobile phones to improve educational outcomes: An analysis of evidence from Asia. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(1), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.794

- Vegas, E. (2020). School closures, government responses, and learning inequality around the world during COVID-19. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/school-closures-government-responses-and-learning-inequality-around-the-world-during-covid-19/

- Wolfenden, F., Adinolfi, L., Cross, S., Lee, C., Paranjpe, S., & Safford, K. (2017). Moving towards more participatory practice with Open Educational Resources: TESS-India academic review. The Open University. http://oro.open.ac.uk/49631/

- World Bank. (2020). How countries are using edtech (including online learning, radio, television, texting) to support access to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- York, B. N., Loeb, S., & Doss, C. (2018). One step at a time: The effects of an early literacy text messaging program for parents of preschoolers. The Journal of Human Resources, 54, 0517–8756R. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.3.0517-8756R

- Zualkernan, I. A., Lutfeali, S., & Karim, A. (2014). Using tablets and satellite-based internet to deliver numeracy education to marginalized children in a developing country. 4th IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC 2014) proceedings (pp.294–301). https://doi.org/10.1109/GHTC.2014.6970295