ABSTRACT

‘Nu alrest lebe ich mir werde’, or ‘Palästinalied’, is a song written in Middle High German by the minnesinger Walther von der Vogelweide probably in the 1220s, extolling the virtues of the Holy Land and of crusading. Although claims that it is a contrafact of Jaufre Rudel’s Lanquan li jorn are disputable, the song shows evidence of the creative reinvention that was a feature of medieval music. While it defines a specific historical moment, the Palästinalied also enjoys a prodigious afterlife. Modern performances and recordings outnumber those of any other German song from the period. From the 1970s to the year 2000, most of these versions could be broadly categorised either as historically informed ‘Early Music’ performances or as falling within the ‘medieval gothic’ or heavy metal genres of rock/pop music. Developments in music technology, recording and social media in the past twenty years have led to an even greater proliferation and diversity of treatments and interpretations. This article explores: how we might account for the song’s popularity; the significance of its modern reinventions and what they can tell us about public perceptions of the crusading era; and how the Palästinalied is being repurposed within the social, cultural and political contexts of our own time.

Introduction

The song ‘Nu alrest lebe ich mir werde’, now commonly known as the Palästinalied, was written in Middle High German by Walther von der Vogelweide (c. 1170–1230 CE) around the time of the Fifth Crusade (1217–21). It is a prominent example of Minnesang, i.e. the German lyric tradition associated with the nobility and similar to the troubadour and trouvère traditions of southern and northern France. It is also a crusade song in the strict sense: that is, a song specifically about, or exhorting people to, crusade, rather than simply mentioning the crusade in passing, for instance as part of a courtly love song.Footnote1 Modern performances and recordings of the Palästinalied ‘outnumber those of any other German song’ of the period and it is one of the most well-known crusade songs.Footnote2 It has countless uploads to social media and streaming platforms, while new versions appear frequently.

The present study will show: firstly how musical features of the song, as well as its text, have interacted with social, cultural and political factors in the last thirty years to turn it into a ‘cultural item’Footnote3 with its own ‘afterlife’; secondly, what recent uses of the song can tell us about public perceptions of the Middle Ages; and thirdly, how ethnomusicologicalFootnote4 methods offer us valuable tools both for historical research and for exploring what meanings the past holds for people in our own time. These methods may include practice-based research such as learning and performing songs from the past using resources that would have been available then; going through this process brings insights that musicologists and historians cannot gain from only studying the song on the page. Methods may also include analysis of performance contexts, communities and wider culture, taking an emic approach in order to discover the performers’ and audiences’ own understandings of their musical activities.Footnote5 Music’s special ability to encode markers of social groups and ideologies makes it a valuable historical and anthropological source.

The song

The Palästinalied’s earliest attestation is in the Kleine Heidelberger Liederhandschrift (c. 1270),Footnote6 where it has seven stanzas of seven lines each. Later sources have variously up to thirteen stanzas, all of uncertain authorship. The ‘core’ seven are shown below, along with an English translation commendable for adhering closely to each line’s meaning while retaining the rhyme scheme:

The first two stanzas have a devotional, contemplative style. However, the seventh line of the third stanza begins to strike a more aggressive tone: ‘Woe to you, heathens!’ (i.e. Muslims, although in some versions the German has ‘Juden’). In the fifth stanza there is a somewhat gloating reference to ‘the Jews’ sorrow/fear and woe’, but it is the seventh stanza which is the most unequivocal in terms of crusading ideology: ‘Christians, Jews and heathens / All say that this is their patrimony … Ours is the [only] just claim / So it is right that [God] should grant it’. This is a strikingly explicit restatement of the principal aim of the crusading movement from its inception: the recapture and safeguarding of the Holy Land, and of Jerusalem in particular, for Christendom in a ‘just war’. The reference to the Muslims as heiden is also significant; its meaning being ‘heathen’ or ‘pagan’ with the additional undertone of ‘barbarian, uncivilised’, as if it were not simply their religious difference but an inherent inferiority that made them unworthy tenants of the holy places. Which stanzas are included in a modern rendition, and especially whether the version includes this problematic seventh stanza, may offer an indication of what purpose and understanding lies behind that particular interpretation.

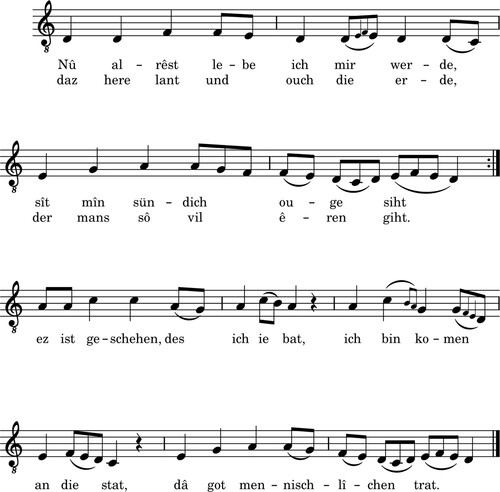

Not unusually for a twelfth- or thirteenth-century song, the form is strophic; each stanza is set to the same melody. The oldest source for the melody is the fourteenth-century ‘Münster fragment’ currently held at the State Archives of North Rhine-Westphalia.Footnote7 The melody can be represented in modern notation as in .

Figure 1. Palästinalied in modern notation (author’s own transcription, with reference to Palisca39)

Several of the Palästinalied’s musical features are important to our study. Firstly, the melody is in Dorian mode (‘first mode’ in medieval theory), whose typical intervals, shape and contours sound to us like a minor key and may be associated with a melancholic or mysterious mood. It was suggested in the 1950s that the tune was a contrafact of Lanquan li jorn, an earlier crusade/courtly love song composed c. 1147 by the Occitanian troubadour Jaufre Rudel.Footnote8 This theory is still widely upheld, despite a convincing study in the 1980s arguing that, rather than contrafacture, Palästinalied in fact employs common melodic figures that were ‘in the common domain’ of both liturgical chant and secular music at the time.Footnote9 In either case we could say that the melody is therefore quintessentially ‘medieval’. Secondly, although medieval musicians did experiment with new kinds of intervallic construction, harmony, chromaticism and modulation to other modes, the Palästinalied melody shows no indication of these. Staying firmly within the mode, it naturally lends itself to a drone accompaniment or open harmonies, but its simplicity also offers modern musicians the potential for diverse kinds of arrangement.

Thirdly, the word setting offers flexibility in performance. It is partly syllabic, in common with many medieval melodies, but also indicates a considerable amount of melisma (i.e. more than one note per syllable). However, there are rarely more than two or three notes per syllable, and in many places the melisma might be considered ornamental, in that not all of the notes are essential to the general shape of the melodic motif (this is especially the case with those notes shown as smaller ‘in-between’ notes in the transcription below). A singer could therefore omit some notes without affecting the identity of the tune. This in turn might have implications for other elements such as tempo, mood and arrangement. Melismatic settings tend to necessitate a slower tempo as it takes longer to sing each line, but a more syllabic rendering could imbue the song with a livelier tempo and feeling, as well as lending itself more readily to group singing. We shall see instances of each type of treatment in the examples to follow.

There are related considerations of pulse and rhythm. As with most medieval songs that have come down to us, there is no indication (as far as we understand) of these in the Palästinalied’s original notation, although the rhythm of the words can help us to an extent. Many medieval songs do not seem to suggest a time signature, although there has been a tendency among some modern editors to transcribe them with some kind of triple metre. Here however, the words and melody together seem to lend themselves to an even duple metre,Footnote10 which in turn may inspire a marching beat and perhaps a rousing, militaristic arrangement. It is also appealing to creators of dance tracks. However, some of the most interesting versions to appear in the last few years have used the absence of a prescribed beat as an opportunity to be creative with rhythm and percussion, as we shall see later.

Use by the Far Right in modern times

The crusades and medievalist tropes in general have a history of being appropriated in the promotion of right-wing, nationalist and racist agendas, from the beginnings of medieval studies and the parallel rise of ‘Romantic nationalism’ in the nineteenth century, through twentieth-century Fascist and Nazi constructions of the medieval past as a kind of ethnically ‘pure’ golden age, to modern-day white supremacists in the USA styling themselves ‘alt-knights’.Footnote11 Considering this, it is not surprising that the Palästinalied is popular with today’s far- and alt-right. This is evident in a YouTube or TikTok search, which returns many home-made videos using pre-existing recordings of the song set to evocative images of knights and the Holy Land. The comments, if enabled, are revealing; for example the following, on the video entitled ‘German Medieval Crusader Song – Palästinalied’, uploaded to YouTube by ‘AgtfCZ’ in 2018:Footnote12

‘One does not simply upload this song and expect not to see “Deus Vult” comments :-)’Footnote13

Geopolitical developments

In Britain and in wider Europe during the 1990s there was much concern with national (and other forms of) identity. This was reflected in British popular culture by the ‘Cool Britannia’ and Britpop movements. There was also a narrative of globalisation and multiculturalism which did not fit with the daily experiences of many people. According to the Runnymede Trust, whose 1997 report brought the term ‘Islamophobia’ into common usage, during this period there was a marked increase in racist and anti-Muslim attacks, along with an increase in institutional racism.Footnote14 The 1990s also saw the rise of the British National Party and similar far-right political movements across Europe.

In the Middle East there was the First Gulf War, and in the USA the establishment of PNAC (‘Project for the New American Century’), a highly influential neo-conservative think-tank which advocated and prioritised the removal of Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq. As the year 2000 approached, there was an upsurge in Holy Land-focused apocalyptic movements among the Christian religious right, reminiscent of crusades-era millenarianism. The Al-Qa’eda attacks in the USA on 11 September 2001, and the ‘axis of evil’ rhetoric which followed in the aftermath,Footnote15 led to a further increase in Islamophobia and ‘created a psychology of threat’.Footnote16 The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and the rise of Islamic State, the Arab Spring of 2011, the overthrow of Qaddafi in Libya, the start of the civil war in Syria and the phenomenon of ‘home-grown terrorists’ in the West have all fed into the ongoing narrative of ‘the ever-turbulent Middle East’ and a ‘clash of civilizations’.Footnote17

Such narratives become more powerful when coupled with music, which can encode identities and become weaponised in situations of conflict, as shown in a recent study of the use of the song ‘The Ballad of Billy McFadzean’ by loyalist paramilitaries in Northern Ireland:

Arts, and music in particular, play a crucial role in facilitating the construction of the self and simultaneously legitimising the exclusion of others and process of othering … songs of the past can be employed as symbolic capital to justify physical violence and hatred in the present … Footnote18

Subcultural aesthetics

(a) The Early Music revival

A putative rediscovery of pre-seventeenth-century music occurred within the classical music (or ‘Western art music’) world, from the 1960s onwards, gathering pace in the 1980s. Laurence Dreyfus implied that much of the impetus for this revival came from an ideology that saw Early Music as more inclusive and accessible, more aligned with ‘folk’ values of interdependence and community, as opposed to Western art music’s perceived elitism and competitiveness.Footnote19 I suggest that this facilitated the crossover of Early Music idioms into rock and pop genres. By the 1990s, it was not unusual to hear sampled Gregorian chant, for example, turning up in dance tracks and chart hits. Since then there has been ongoing discussion in scholarship about ‘reception theory’ in medieval music and how Early Music concerns are shaped by contemporary culture.Footnote20

(b) Medieval metal

We have seen that the Palästinalied is often appropriated by right-wing ideologues and communities. Among such interpretations of the song, a significant number of ‘medieval metal’ bands are represented. A recent study of early 1990s black metal has discussed the ‘promotion of [far-right] values and ideologies through imagined traditions and aesthetics’ within the genre.Footnote21 However, this does not mean that all such bands must be neo-Nazis. As Kirsten Yri has argued,

German ‘folk’ bands invented ‘medieval’ rock to sidestep Nazi connotations with the word ‘folk’ … [Corvus Corax did this] by first positioning the medieval minstrel as a punked-up, marginalised ‘outcast’.Footnote22

Corvus Corax’s left-of-centre credentials are further emphasised in their biography on allmusic.com:

The band focused less on the church music which dominated the era, and more on the music of the man of the, uh, fief, if you will, with authentic instruments, and period costumes.Footnote23

Performing a purely instrumental arrangement of the Palästinalied, as Corvus Corax do, may allow musicians to avoid the problematic connotations of its text to some extent. Initially released in 1990, with a remastered version appearing in 2016, it has been a particular favourite at their live shows, such as ‘Corvus Corax - Palästinalied - Leipziger Umschlag 2016’ uploaded to YouTube by ‘Hrothgar the Saxon’.Footnote24 Despite this, the band stated in a 2006 interview that they wanted ‘nothing to do with Minnesang … ’,Footnote25 showing that musicians’ output can sometimes be at odds with their stated objectives, and that their own rationalisations for their activities may change over time. It is also testament to the overriding appeal of the tune.

Corvus Corax’s foregrounding of ‘period’ bagpipes and large drums is a sure indication of their ‘medieval rock’ credentials, as these instruments are common aural markers of medievalism in music. They also appear in a performance of the Palästinalied by another German band, In Extremo, in 2005.Footnote26 In contrast to the Corvus Corax version, this has vocals, but it includes only the first three stanzas and finishes by returning to the first. This disrupts the flow of ideas in the text – suggesting a deliberate avoidance of the problematic final stanza, as including it would have brought the song to a more logical conclusion. Also in comparison with the Corvus Corax performance, In Extremo’s features more typical heavy metal, non-medieval elements. As stated in a 2013 case study of this version, ‘the singer does not adopt a medieval singing style but sings with a raw vocal tone colour’.Footnote27 However, what a ‘medieval singing style’ might be is not explained. The implication is that the reader must know what it is, and that it is significantly different from ‘a raw vocal tone colour’! This is an example of the kind of assumptions that are often made not only about the sounds of medieval music but also about modern listeners’ ‘knowledge’ of them. We might infer that the author imagines a medieval singing style to be more ‘polished’; a pure and ethereal vocal timbre in a higher register, perhaps similar to the kind of vocal qualities common to Early Music singers of the 1980s and 1990s or in some modern renditions of Gregorian chant. In fact we do not know for certain what vocal timbres, if any, were particularly favoured in medieval singing and it is possible that styles varied widely across genres, regions and performance contexts.

(c) Goths

Performances of the Palästinalied are also common in the goth music scene. The word ‘gothic’ itself implies a fascination for things medieval. Here, however, rather than being co-opted into the service of political agendas, medieval(ist) idioms and aural markers are more likely to represent a self-conscious escapism into an imagined, idealised past.

Qntal’s 2003 performanceFootnote28 combines medieval signifiers with electronic elements, and sets up some striking contrasts, such as the ‘ancient’ vocal section versus the ‘modern’ synth instrumental section. An ethereal damsel on vocals and an array of period instruments at the back of the stage are visual as much as aural markers, and an analysis of gender roles would certainly yield enough material for an extended study – as indeed it would with the versions previously discussed. The first four stanzas of the text are sung; like In Extremo’s version including the ‘Woe to you, heathens!’ line but stopping short of stanza seven.

The goth aesthetic has been described as ‘romantic nostalgia for the irrational, dark, untamed and uncultured Middle Ages’,Footnote29 but the present author’s personal experience suggests goths tend to perceive the Middle Ages as in some ways more cultured than our present time. At the same time many have an interest in history, and are aware that there is probably a gap between their idea of ‘medieval times’ and what the realities may have been:

I really only like the way I imagine medieval times in my fantasy mind. My rational mind does not want to experience life in medieval times under any circumstances.Footnote30

New directions for the Palästinalied

Discussed above are some of the ways in which ideas about the (imagined) past, along with listeners’ personal responses to it, can be encoded in sound. We have explored such processes at work in the Palästinalied. The song has a self-perpetuating currency within the goth and metal communities as it is more likely to be already known by those who listen to this type of music. In this way it becomes a ‘cultural item’, continually reinforcing its status as a medieval song par excellence while simultaneously acquiring new layers of meaning. To return to Millar and Chatzipanagiotidou’s case study of ‘the Ballad of Billy McFadzean’:

Musicians therefore have a role as cultural and memory brokers … [but] the agency of musicians is also partly hampered by ‘the power of songs’ themselves … deemed to carry an ‘essence’ that overpowers aesthetic choices and creates ethical dilemmas for musicians. It is in these moments new possibilities of cultural interpretations may emerge and shift.Footnote32

Denstrow’s ‘Palastinalied (Chill out Psy Dub & Ambient)’ (2021) is an electronic dance/trance recording with mainstream pop sensibilities.Footnote33 The surprising cover art – a photograph of a woman relaxing in a bikini, evoking holidays, leisure and enjoyment – seems strangely inappropriate and out-of-context. It is of course possible that the creators of the track were unaware of the tune’s history and used it primarily because of its catchiness and compatibility with a dance beat.

Afrit Temple’s version (North Carolina, USA, 2013) brings in Middle Eastern instruments – ‘oud (Arab lute) and percussion, combining them with digital sounds, synth bagpipes and rock guitar.Footnote34 The focus, however, is on rhythmic dynamism and energy, which changes constantly from one stanza/section to another. Again, it is unclear how conscious the composer may have been of the melody’s crusading connections. Their website (afrittemple.com) indicates a general concern with Middle Eastern and ‘world’ musics, and with dance.

In the ‘FiddelalterMolk’ version (Germany, 2008) the melody has become a cliché, performed as part of a comedy folk medley along with ‘Scotland the Brave’ and other well-known tunes.Footnote35 Perhaps the most remarkable version, however, is a digital ambient arrangement by Aviophonics (Germany, 2017) in which the melody has been deconstructed, becoming elusive to the point of being almost unrecognisable.Footnote36 The intention here seems to be to create a dreamy, ethereal atmosphere rather than to promote any kind of political agenda.

An 8-bit version of the Palästinalied also exists. Otherwise known as chiptune, 8-bit is a type of electronic music made using the sound generator chips in vintage arcade and computer games. Created in 2021, this version therefore juxtaposes a post-modern ‘retro-futuristic’ feel with medievalism. When considered with its accompanying imagery and the other material produced by the same YouTube user, it seems designed to appeal to alt-right fantasists who spend an amount of time playing video games in which they imagine themselves to be Templar knights about to capture Jerusalem.Footnote37 The 8-bit Palästinalied shows that it is still easy to find political uses of the tune among the various instrumental interpretations. However, the proportion of versions focusing primarily on the musical possibilities of the melody seems to be growing.

Conclusions

The case of the Palästinalied shows how people’s preconceptions about what medieval music ‘should’ sound like can be linked to broader assumptions about the crusades and the Middle Ages, and how these may be instrumentalised for various sociocultural and political ends. To certain communities and individuals, the song has become an identity marker – what it represents is essential to their sense of self. In such instances, the song’s text may be the most obvious reason why people are drawn to it, but there is more going on here. A large part of the song’s appeal lies in the fact that it is easy to make its inherent musical features sound however one believes medieval music should sound – something that is not actually true of all medieval music! Yet the melody alone offers performance possibilities that can take it beyond medievalist interpretations. One possible avenue for future research might be to explore whether there are any instances of the Palästinalied being ‘reclaimed’ or reinterpreted by Muslim and Middle Eastern artists.

It has been argued that an important concept in medieval song was mouvance, or perpetual reinvention.Footnote38 Songs could be thought of as living entities on their own journeys. This seems particularly pertinent for the Palästinalied. While its ‘medieval-ness’ ensures its popularity among those for whom the Middle Ages serve as an arena in which to construct identities and ideologies, its intrinsic melodic traits lend themselves to a diversity of arrangements which enable it to continue living and which may eventually detach it from its original crusading context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 There was no concept of ‘crusade song’ as a specific genre during the crusading era itself. Concern with identifying such a genre seems to have begun in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, with the first attempt at a definition by Kurt Lewent, ‘Das altprovenzalische Kreuzlied’, Romanische Forschungen 21 (1908): 321–448. Lewent distinguished between hortatory songs and those that only made passing mention of crusading. Joseph Bédier and Pierre Aubry, Les chansons de croisade avec leurs mélodies (Paris, 1909), went on to include some courtly love songs. Since then, the idea of what may constitute a crusade song has been much discussed, in tandem with the understanding of crusading as a pervasive feature of life in the European Middle Ages. Most attention has focused on troubadour and trouvère songs in Old Occitan and Old French respectively. In 2018 a University of Warwick project headed by Linda Paterson identified over 200 of these as crusade songs, including crusade-related love songs (https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/modernlanguages/research/french/crusades/). The minnesingers were much influenced by the troubadour and trouvère traditions. See also: Jean Frappier, La poésie lyrique française aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles: les auteurs et les genres (Paris, 1966); Richard L. Crocker, ‘Early Crusade Songs’, in The Holy War, ed. Thomas Patrick Murphy (Columbus, OH, 1976), 78–98; Pierre Bec, La lyrique française au moyen âge (XIIe-XIIIe siècles), 2 vols. (Paris, 1977–8); Peter Hölzle, Die Kreuzzüge in der okzitanischen und deutschen Lyrik des 12. Jahrhunderts: das Gattungsproblem ‘Kreuzlied’ im historischen Kontext (Göppingen, 1980); D.A. Trotter, Medieval French Literature and the Crusades (1100–1300) (Geneva, 1988); Cathrynke Dijkstra, La chanson de croisade: Études thématiques d’un genre hybride (Amsterdam, 1995); Cecilia Gaposchkin, Invisible Weapons: Liturgy and the Making of Crusade Ideology (Ithaca, 2017); Linda Paterson, Singing the Crusades (Cambridge, 2018); Luca Barbieri, ‘Crusade Songs and the Old French Literary Canon’, in Literature of the Crusades, ed. Simon Parsons and Linda Paterson (Cambridge, 2018), 75–95; Rachel May Golden, Mapping Medieval Identities in Occitanian Crusade Song (Oxford, 2020).

2 Henry Hope, ‘Performing Minnesang: Editing “Loybere risen”’, in Performing Medieval Text, ed. Andis Butterfield, Henry Hope and Pauline Souleau (Cambridge, 2017), 153.

3 Paul Willis, Profane Culture (London, 1978), 223–66.

4 Ethnomusicology may be defined as ‘the study of music in a sociocultural context’: Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, 10th Edition, 1993.

5 ‘Emic’ in ethnomusicology and anthropology describes the study of cultural phenomena from the perspective of a participant in that culture.

6 MS A.: Heidelberg University Library, Cod. Pal. germ. 357. See: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg357.

7 Landesarchiv Nordrhein-Westfalen/Staatsarchiv. Msc.VII.51; viewable online at https://collections.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/HisBest_cbu_00008634.

8 Heinrich Husmann, ‘Das Prinzip der Silbenzählung im Lied des zentralen Mittelalters’, Die Musikforschung 6 (1953): 17–18. A contrafact is the text of one song set to the melody of another – not unusual in medieval music. A similar phenomenon occurs in traditional folk music and in church hymns.

9 James V. McMahon, ‘Contrafacture vs. Common Melodic Motives in Walter von der Vogelweide’s “Palästinalied”’, Revue belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap 36/38 (1982–4): 5–17.

10 Based on the author’s own practice-led research. After learning the text then speaking and singing the song through a few times, the combined melodic and textual elements seem to fall into a simple duple metre (strong – weak, strong – weak) much more naturally than into a triple or even compound duple one (strong – weak – weak, strong – weak – weak). Also, the Palisca transcription implies a 4/4 time signature, which could easily be rendered into 2/4.

11 See e.g. Clare A. Simmons, ed., Medievalism and the Quest for the ‘Real’ Middle Ages (London, 2001); Charlie Powell and Alyssa Steiner, ‘Medieval Studies and the Far Right Conference’ (Oxford, May 2019): https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/article/blog-post-for-medieval-studies-conference (accessed May 17, 2022).

13 YouTube user ‘Filius Reticulus’. Note also the reference to Peter Jackson’s 2001 film version of The Fellowship of the Ring from Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (a work already rich in medievalist associations): ‘One does not simply walk into Mordor … ’.

14 Commission on British Muslims and Islamophobia – Runnymede Trust, Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All (London, 1997): https://assets-global.website-files.com/61488f992b58e687f1108c7c/617bfd6cf1456219c2c4bc5c_islamophobia.pdf (accessed May 18, 2022).

15 Former US President George W. Bush in his State of the Union Address, 2002. Text available at https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2002/01/20020129–11.html.

16 Robert Zoellick, former US Deputy Secretary of State 2005–6, on BBC Radio 4, What Really Happened in the Nineties?, Episode 8 (‘Race Relations’, 11 May 2022: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0017459) and Episode 9 (‘The Iraq War’, 12 May 2022: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00174dn) (accessed May 16, 2022).

17 Ibid.

18 Stephen R. Millar and Evropi Chatzipanigiotidou, ‘From Belfast to the Somme (and Back Again): Loyalist Paramilitaries, Political Song, and Reverberations of Violence’, in Ethnomusicology Forum 30, no. 2 (2021): 246–65, at 248–50. See also Martin Stokes, ed., Ethnicity, Identity and Music: The Musical Construction of Place (Oxford, 1994).

19 Laurence Dreyfus, ‘Early Music Defended against Its Devotees: A Theory of Historical Performance in the Twentieth Century’, Musical Quarterly 69, no. 3 (1983): 297–322.

20 See e.g. Kay Kaufman Shelemay, ‘Towards an Ethnomusicology of the Early Music Movement: Thoughts on Bridging Disciplines and Musical Worlds’, Ethnomusicology 45 (2001): 1–29; Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, The Modern Invention of Medieval Music: Scholarship, Ideology, Performance (Cambridge, 2002); John Haines, ‘Living Troubadours and Other Recent Uses for Medieval Music’, Popular Music 23, no. 2 (2004): 133–53; idem, Music in Films on the Middle Ages: Authenticity vs Fantasy (New York, 2013).

21 Dominic Weber, ‘Satanism, Neopaganism, Antisemitism: The Middle Ages as an Inspirational Space in Far-Right Black, Pagan and Viking Metal’ (paper at the ‘Medieval Studies and the Far Right Conference’, Oxford, 11 May 2019): https://ox.cloud.panopto.eu/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=564cf564–7b96–4def-b450-aa4a00dcba14 (accessed May 17, 2022).

22 Kirsten Yri, ‘Corvus Corax: Medieval Rock, the Minstrel, and Cosmopolitanism as Anti-Nationalism’, Popular Music 38, no. 3 (2019): 361–78, at 361.

23 Chris True, ‘Corvus Corax Biography’: https://www.allmusic.com/artist/corvus-corax-mn0000780501/biography (accessed May11, 2022).

25 Interview by Sascha Blach for subkultur.de, 18 July 2006: https://goettertanz.wordpress.com/2006/07/13/corvus-corax-die-gitarre-des-mittelalters-interview/ (accessed May 11, 2022)

27 Anaïs Verhulst, ‘Power Chords and Bagpipes: The Representation of Folk and the Medieval in Heavy Metal’ (MA diss., University College Dublin, 2013), 43.

29 Isabella Van Elferen, Gothic Music: The Sounds of the Uncanny (Cardiff, 2012), 154. Goth was also noted in its earlier days for being ‘wracked with religious imagery’: Mick Mercer, Gothic Rock Black Book (London, 1988), 11.

30 MB (anonymised), informal communication to the author, February 2022.

31 Several of these traits are also identified by Van Elferen, Gothic Music, 134–55.

32 Millar and Chatzipanagiotidou, ‘From Belfast to the Somme’, 250.

38 Paul Zumthor, Essai de poétique médiévale (Paris, 1972), 71–3 and passim.

39 Claude V. Palisca, ed., Norton Anthology of Western Music: From Ancient to Baroque (New York, 1996), 48.