ABSTRACT

A tailor shop located in Singapore’s Chinatown is explored as a case of creative linguistic marketing practice, examining how such practice can be understood in relation to the interaction of local and global forces on the linguistic landscape. The shop uses a range of Scandinavian semiotic resources (language and artefacts) which for us, coming upon the shop, seemed unexpected or, using Sweetland’s term, spectacular. Following in the spirit of linguistic landscape analysis, we investigate one particular dimension of the visual semiosis of this shop, namely the signage. Drawing upon photographic and interview data, we trace the history of this semiosis, charting how its purpose and meaning has changed over time. What emerges from our study is that what seems idiosyncratic to researchers can have rich local meaning in context. What appears to be an outlier on the linguistic landscape can offer insight into situated experiences. In this light, our study of a shop and its semiotic landscape contributes to an understanding of the changing sociolinguistic patterns and creativity that occur in spaces like Singapore, and that reflect not just contemporary but also previous eras of globalisation and contact across historical, political and cultural borders.

Introduction

Linguistic landscape studies often look for trends in visual language use that offer tangible evidence of dominance or ethnolinguistic vitality (e.g. Shohamy, Ben-Rafael, & Barni, Citation2010). Central to such work is reporting on the relative distribution of languages on signs. While the focus tends to be on trends, such findings often also include outliers – linguistic curiosities that might only appear once or twice in the data and may even be excluded from further analysis. In this study, we turn our attention to such an atypical case: Abba’s Department Store in Singapore with prominent Scandinavian signage.

The signs drew our immediate attention when we came upon them while exploring the markets of Chinatown in June 2013, prompting a later return in 2015 for further inquiry. Such vivid use of Scandinavian semiotic resources seemed unexpected (Pennycook, Citation2012) in the commercial linguistic landscape of a district where Chinese and English are most commonly seen and heard (Tan, Citation2014). How, we wondered, could we make sense of this apparent anomaly in the linguistic landscape of Singapore? What is the story behind these signs? As we show in this study, the semiotic practices on display in and around the shop bring to light lived experiences with trajectories of globalisation and how they can be leveraged creatively for locally situated marketing. We begin with a review of earlier studies of Singapore’s linguistic landscape, and then discuss Sweetland’s (Citation2002) notion of ‘spectacular language’ and Pennycook’s (Citation2012) concept of ‘language in unexpected places’ as they relate to commercial contexts. Next, we turn to a close examination of the visual semiosis of the tailor shop and the owner’s insights into its development. Finally, we interpret our visual and interview findings in light of the theoretical underpinnings of spectacular and unexpected language use, reflecting on what the findings suggest about affordances for meaning-making.

The linguistic landscape of Singapore

Singapore is a constitutionally multilingual country, with Malay, Mandarin, Tamil, and English as official languages. English has become a prominent language due to its position in education, its function for inter-ethnic communication, and its association with the power and prestige of international commerce, while the other languages are seen as serving heritage and community functions (Ng, Citation2014; Silver, Citation2005). It is a multilingual context in which national ethnolinguistic diversity and the globalisation of trade and tourism intersect, and the study of its linguistic landscape is an emerging area of scholarship.

Early linguistic landscape analysis of Singapore investigated street names, demonstrating that government language management of signs since the 1990s has contributed to the increased visual salience of English and its prominence over Mandarin and Malay in the semiotic construction of place (Tan, Citation2007). In a later study focused on the signage across different types of sites, Tan (Citation2011a) finds diversity in the languages used. For example, state school signs appear in all four of Singapore’s official languages (Malay, Mandarin, Tamil, and English) in the order in which they appear in the constitution, suggesting symbolic alignment with policy by state entities even while education is English-medium. Meanwhile, names rendered using the Latin alphabet tend to be favoured on street and rail station signs, with the exception of ‘heritage’ areas such as Little India and Chinatown, where additional signs using Tamil script and Chinese characters also appear. Tan concludes that language choice on signage variously reflects the indexing of government language ideology, ethnic commodification, and instrumental communication. In a subsequent study, he corroborates this variation, noting in particular the use of languages for ethnic commodification in so-called heritage areas:

Both Chinatown and Little India have since [the nineteenth century] been set up to function more as tourist attractions for local people and visitors, and their linguistic landscape has been manipulated deliberately to enhance the status of these places as attractions. Chinese in Chinatown would serve a symbolic function for visitors who do not read Chinese and thus remind them of the location’s desired meaning. (Tan, Citation2014, p. 460)

There is a growing interest among scholars in the linguistic landscape of Singapore. It has captured the attention of junior researchers as seen in papers by students at Nanyang Technological University, including Wanting and Min’s (Citation2012) investigation showing the prominence of Chinese and English in two hawker food centres and Lim, Rosman, and Goh’s (Citation2012) study demonstrating the prevalence of English and presence of international tourists’ languages at Changi Airport. In addition, Tang (Citation2018) examines signage in and around the Mass Rapid Transport (MRT) Circle Line rail stations, revealing the prominence of English and the limited usage of Chinese, Malay, and Tamil.

Recent attention has turned to shop names and signs. Shang and Zhao (Citation2017) and Shang and Guo (Citation2017) report on a study of 1097 shop signs across ten neighbourhood shopping centres near residential areas in the western region of Singapore. They found English to be widely present, appearing on 96% of signs, whether alone or in combination with other languages. When appearing with another language, it was most often Chinese in either simplified or traditional scripts. Notably, on 45% of such signs, Chinese was made more visually salient with a larger font size. In contrast, Malay and Tamil appeared on only 3.6% of signs. Monolingual Chinese signs were also few, representing only 4.1% of signs. Shang and Zhao (Citation2017) note that the strong presence of Chinese may not be surprising since the largest ethnic group (in Singapore’s demographic classification) is Chinese, and shops display signs appealing to this target market. The presence of English, they note, instrumentally reflects its potential to reach target markets across multiple ethnic groups in addition to its prestige in contemporary Singaporean society. Shang and Guo (Citation2017), in turn, suggest that the dearth of Malay and Tamil may, on the one hand, be due to fewer shop owners from these ethnic groups in the ten neighbourhoods and, on the other hand, be the result of such shop owners avoiding their languages in order to appeal to a wide target market.

In another study of shop signs in Singapore, Ong, Ghesquière, and Serwe (Citation2013) examine the storefronts of food and beauty shops. Over three years of data collection across luxury shopping and residential areas of Singapore, they focused on the use of French, a language not widely spoken in Singapore but indexed with cosmopolitanism. Their findings align with Ben-Rafael’s (Citation2009) principle of presentation of self, which holds that the name of a store is chosen to differentiate it among other stores, as shown by names that blend French with English in creative ways in order to stand out against other shops using English and Chinese. French-English blended names include Nail Clinique for a beauty salon, TecLique for a bar featuring arcade games, and Erabelle for a spa. Ong et al. also suggest that their findings further align with Ben-Rafael’s (Citation2009) principle of good reason, which posits that language use on signs should appeal to locally situated values and expectations, in that the use of French serves the specific purpose of appealing to an internationally-minded Singaporean clientele participating in the global linguistic fetishisation of French around the commodification of food and beauty (cf. Kelly-Holmes, Citation2014).

In sum, current work on Singapore’s linguistic landscape demonstrates that it is a rich arena for investigating the socially situated visual construction of public space. Thus far, research has tended to focus on signage itself rather than on stories behind the signs. As Tan avers, there is a need for ‘a more ethnographic approach to the phenomenon and to provide an account of the genesis of the particular form of the linguistic landscape created by different agents and agencies’ (Citation2014, p. 462). Our aim in the present case study is to take up this charge.

Spectacular and unexpected language use

While linguistic landscape studies of Singapore have tended to focus on linguistic trends in specific spaces, we identify and focus on an instance of language which does not represent a pattern and which, in fact, might be seen as an anomaly in a linguistic landscape study designed to measure ethnolinguistic vitality and language hierarchies in this context. The use of Norwegian on the signs of a tailor shop in Chinatown, we argue, can be seen as an example of ‘“spectacular” uses of language, in which a variety is begged, borrowed, or stolen by speakers who don’t normally claim it’ (Sweetland, Citation2002, p. 515). Such instances of spectacular language can be seen as one-off uses and dismissed as idiosyncratic, inauthentic and insignificant outliers, given the focus on identifying trends in linguistic landscape studies. This, in turn, reflects a more deep-rooted concern in sociolinguistics generally with stable and long-standing oral speech communities and on everyday, patterned language uses, which have been reified as authentic. However, in the context of a new focus within the sociolinguistics of globalisation, there has been a growing interest in such spectacular and ‘inauthentic’ uses and they have become ‘prized [in sociolinguistics literature] for their value in understanding the social meanings that adhere to language varieties and the many ways in which speakers can put such ideologies to work’ (Sweetland, Citation2002, pp. 516–517). In other words, ‘if we operate within the playing field of modern expectation – what we might expect to encounter where – then turning up in unexpected places might be seen as an aspect of postmodernism or globalization’ (Pennycook, Citation2012, p. 19). Such uses have been studied in terms of ‘styling the other’ (Bell, Citation1999), ‘mock’ language (Hill, Citation1999), ‘crossing’ (Rampton, Citation1995), and language display (Eastman & Stein, Citation1993); and, particularly in relation to marketing, ‘linguascaping’ (Jaworski, Thurlow, Ylänne-McEwen, & Lawson, Citation2003) and ‘linguistic fetish’ (Kelly-Holmes, Citation2005, Citation2014). Rather than viewing the unexpected as an outlier, these orientations highlight how spectacular language can, in fact, serve as a valuable focus for investigating how the local and global come together in unique and creative ways. Furthermore, it is important to realise that what to an outsider looks like a mere anomaly may make perfect sense in the community, offering insight into meaning-making situated in local histories of wider sociopolitical flows.

Spectacular language use in commercial contexts, as in the present study, also relies on the ‘intense engagement with visuality’ (de Burgh-Woodman & Brace-Govan, Citation2010, p. 188) in contemporary marketing. Furthermore, the way a piece of language looks is also a mode of meaning, not just the semantic meaning to which it is referring (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2001, Citation2006). We can see this by the focus put on the positioning, size and location of language in linguistic landscape studies, in which the semantics of the language are sometimes secondary to its visuality (e.g. Curtin, Citation2009; Vigers, Citation2013). We ‘see’ language in pre-formed, culturally specific ways (just as we ‘hear’ language, e.g. accents, dialects, different languages, and varieties), and the visual multilingualism or monolingualism we encounter either reinforces or challenges our way of seeing. Hence the concern of language planners with changing visual regimes in order to change ideologies, attitudes and habits (Hult, Citation2014, Citation2018). The primarily visual use of languages for marketing exploits ‘the material and historicized dimensions of representation’ (Iedema, Citation2003, p. 50). This use relies on ‘scopic regimes’ (Jay, Citation1988 as cited in Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010), ways of seeing other languages, not just languages that are known and recognised, but also unknown or unfamiliar languages. We can see such one-off uses in commercial contexts as a type of fetish/display (Kelly-Holmes, Citation2005, Citation2014), in that they ‘represent symbolic rather than structural or semantic expression’ (Eastman & Stein, Citation1993, p. 200). So, in this case, we are ‘seeing’ Scandinavian language in the Singaporean linguistic landscape, and our seeing is determined by a scopic regime, in Jay’s terms, which, in turn, is shaped historically. Finally, these ways of seeing are also individually shaped and individually different, and they provide the intertext for future encounters.

Methodology

The present study goes behind the signs of a linguistic landscape by offering a case study (e.g. Duff, Citation2007; Pennycook & Otsuji, Citation2017) of a single shop in Singapore that makes creative marketing use of an unexpected language. In Singapore’s Chinatown, one might expect to see or hear English for wider communication and varieties of Chinese (especially Mandarin) for communication among members of the community as well as to reinforce the area’s heritage status symbolically for tourists (Tan, Citation2014). One might not readily expect to see Norwegian given that Scandinavians as a group comprise less than 1% of all visitors to Singapore (Singapore Tourism Board, Citation2016).

Abba’s Department Store, thus, appears to be an anomaly. It is a tailor shop that makes custom suits and shirts for a tourist clientele. For example, at the time of study, two suits with three shirts and two extra trousers were on offer for 1500 SGD (approximately 995 EUR). Its owner, Jimmy, has no heritage connection to Scandinavia so there is no obvious or immediate explanation for the choice to foreground Norwegian on its storefront signs. From an ethnographic perspective, the shop presents what Agar (Citation1996) terms a rich point, an occurrence that must make sense locally but researchers need more information to understand. As Hult (Citation2009) points out, ‘there is surely a story behind every object in any linguistic landscape’ (p. 94). Accordingly, following Tan (Citation2014), we sought to provide an account for how this shop in Singapore’s Chinatown came to have these unique signs and to explore the agency behind their creation.

Drawing upon the linguistic landscape analysis principle of comprehensive photography (Hult, Citation2009), all visual and textual artefacts inside and outside the shop were photographically documented with the permission of the shop’s owner. In addition, we conducted an extensive semi-structured interview with the owner (cf. Malinowski, Citation2009) in order to be able to interpret the shop’s semiosis in light of his lived experience and personal history with it. Thus, our study was limited in scope to the shop’s visual aggregate and the process of its formation; other semiotic processes such customer interactions and experiences in the shop were not examined here nor was the community of practice of Chinatown tailors or the wider construction of the neighbourhood linguistic landscape, all of which would be fruitful foci for future research. In the next section, we turn to our documentation of the store’s visual semiosis.

Indexing Scandinavian in Chinatown

Rounding the corner of South Bridge Road and Smith Street in Chinatown, one comes upon Abba’s Department Store (). It is a small shop, as most of the shops lining the pedestrian areas of Chinatown are, and one of many tailors. It stands out from the others by provoking curiosity: Does its name have anything to do with the 1970s Swedish pop group?

It does, the shop’s owner Jimmy explains. He recounts the history of the shop, noting that he originally opened it in 1979 near Clifford Pier, where merchant sailors would come ashore. At that time, he notes, Scandinavians made up a substantial number of crew members and officers. Recognising that they would be a good target market for tailored clothing, he set about profiling his business with them in mind. Jimmy has no heritage connection to Scandinavia. He chose the name because he believed the intertextual connection would resonate with his target audience. In an earlier newspaper interview posted on a wall in the shop, he told a reporter, ‘you don’t need a card to remember the name’ (Chiapoco, Citation2005, p. 18).

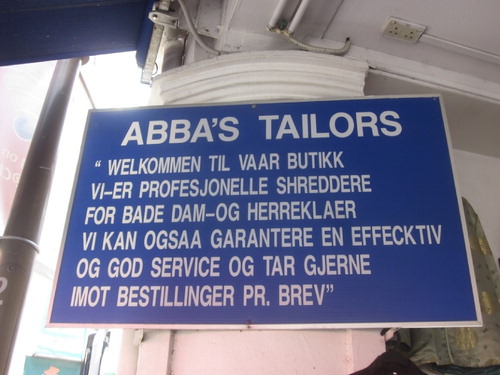

In addition to the shop’s name, a distinguishing feature on the storefront is the presence of two large blue signs with Norwegian text in bold white letters ( and ). He had them made by a local sign shop in the 1980s when his shop was still located near Clifford Pier. At that time, the signs served the purpose of instrumental communication with Scandinavian, and especially Norwegian, sailors. The text in reads:

ABBA’S TAILORS

‘WELCOME TO OUR STORE.

WE-ARE PROFESSIONAL TAILORS

FOR BOTH WOMEN’S AND MEN’S CLOTHINGFootnote1

WE CAN ALSO GUARANTEE EFFICIENT

AND GOOD SERVICE AND GLADLY

ACCEPT ORDERS BY MAIL’

The text in reads:

WELCOME TO SINGAPORE AND TO

ABBA’S DEPT. STORE

LADIES & GENTS CUSTOM TAILORS

WE OBTAIN EVERYTHING THAT CAN BE

OBTAINED IN SINGAPORE

IF WE DO NOT HAVE WHAT

YOU DESIRE IN STOCK

WE WILL GET IT WHILE YOU

LOOK AROUND OR QUENCH YOUR THIRST

TAILOR-MADE SUITS

SHIRTS TROUSERS

CASUAL CLOTHING

In a Singaporean linguistic landscape dominated by English and Chinese (Shang & Guo, Citation2017; Shang & Zhao, Citation2017), these blue signs in Norwegian on Abba’s storefront allow the shop to stand out, much like the luxury shops in Singapore that creatively deploy French (Ong et al., Citation2013). While Scandinavian tourists, expatriates, and the occasional sailor are still among Abba’s clients, they are no longer the primary market. Chinatown draws a much broader spectrum of potential customers. When asked if he would consider making new signs in other languages to appeal to a wider demographic, Jimmy demurs. He contemplates commissioning new signs with the shop’s URL to point potential customers to its website should they pass by after hours. He firmly maintains, however, that he would not change the language on the signs. ‘My signage will always be with me,’ Jimmy proclaimed in the newspaper profile piece (Chiapoco, Citation2005, p. 18). On the one hand, he explains when we ask him to elaborate, the signs are an obvious way to draw in Scandinavian tourists. On the other hand, the Scandinavian image has become part of the brand and reputation that Abba’s has cultivated since the 1970s. Thus, while the signs had their origin in accommodating to a specific niche for instrumental communication in response to global mobility, and still maintain vestiges of that purpose, their enduring semiotic value emerges from flouting the interaction order of Chinatown’s linguistic landscape whereby the use of Norwegian serves to differentiate Abba’s (cf. Ben-Rafael, Citation2009; Ong et al., Citation2013).

Stepping into the shop, it is evident that the Scandinavian orientation is not a mere gimmick. There are semiotic traces of Abba’s long history with the Scandinavian seafaring community. The wall is lined at ceiling height with flags of the world, projecting a general global sensibility, while a Norwegian flag hangs conspicuously on a pole (), indexing a special connection to Norway. Scandinavian artefacts, all gifts from sailor-clients, such as the Norwegian troll and the handcrafted wooden Swedish and Danish flags shown in , are on display. Likewise, visual reminders of Abba’s historical relationship to the maritime industry are seen throughout the shop, including photographs of ships, hats hanging on the walls, and samples of tailored uniforms such as the one in .

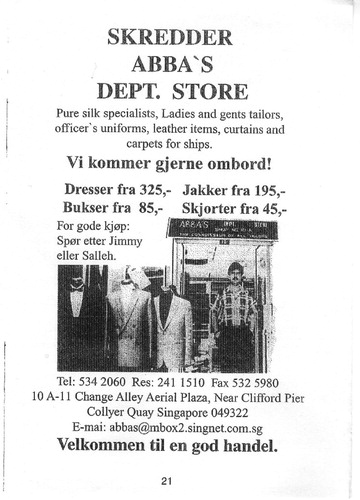

Jimmy also tells of his connection to the Norwegian Seaman’s Mission in Singapore, a congregation that is part of an international network of churches originally serving merchant sailors from Norway. The Singapore mission was established in 1955 and developed around the Norwegian shipping industry. The mission community is now comprised mainly of expatriates who are affiliated with major Scandinavian corporations. Jimmy would regularly place advertisements in the church’s bulletin when it still reached sailors. shows an advertisement from the 2001/2002 edition.

The advertisement is an echo of the original purpose for the large blue signs that still adorn the storefront: instrumental communication with a target market. The association between Scandinavia and the shop’s brand is also apparent here, with ‘SKREDDER [TAILOR] ABBA’S DEPT. STORE’ in bold capital letters at the top. Semiotic traces apparent in the shop today likewise reverberate in the advertisement, such as the allusion to officer’s uniforms, ships, and the statement ‘vi kommer gjerne ombord [we will gladly come aboard]!’ Scandinavians are still among his regular clients, Jimmy comments, though he now relies on word of mouth among expatriate executives rather than on reaching sailors through the church bulletin.

Discussion: spectacular language and creative marketing

Our study of the tailor shop in Singapore highlights a number of insights into creative linguistic practices in marketing. First of all, we can see the role of individual agency in shaping the linguistic landscape and commercial discourses more generally. Sign-making involves picking from the available repertoire of semiotic resources (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2001, Citation2006). Sometimes this picking involves the very obvious, commonly available resources, but sometimes too, as in this case, it can involve the unique repertoire of an individual, or their intuition about their current or future clientele and about the surrounding sociolinguistic environment. Those involved in making marketing signs are, of course, also members of speech communities that have their own linguistic histories and local scopic regimes (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010). Jimmy’s way of seeing when designing the original shop signs – how he ‘saw’ Scandinavian – was shaped by an immediate, direct experience with the merchant shipping industry. His decision to add Scandinavian semiotic features to the linguistic landscape via his shop signs changes the view for other visitors and also for locals. We might speculate that the encounter with these Scandinavian features in the local marketplace can, in turn, shape the scopic regime through which these languages are seen and the associations they have for locals – customers of the market and other shop owners – in other contexts. For foreign visitors, the encounter is also shaped by their individual linguistic biographies and the scopic regimes into which they have been socialised. It is important to recognise that we, as researchers, have also been socialised into particular scopic regimes, and to acknowledge that we are ‘seeing’ through a particular lens. For us, the Scandinavian language practices seemed at first to index something foreign, but as we dug deeper, we realised that it also indexed something equally local. Linguistic fetish is all about understanding foreignness from the point of view of one’s own habitus, as part of the culturally available repertoire for signs, to paraphrase Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2006). The words on display in the text are foreign ‘structured only from the point of view of another language, which is taken as the norm’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 360). The very concepts of spectacular or unexpected language only work if we are looking at the language from the point of view of our own linguistic norm and also our perception of the norms of the linguistic landscape of the place or situation we are encountering, in this case a Singaporean linguistic landscape where English and Chinese tend to dominate on shop signs (Shang & Guo, Citation2017; Shang & Zhao, Citation2017) and French is often indexed with cosmopolitanism (Ong et al., Citation2013).

These ways of seeing are connected to the contemporary valuing of knowledge about ‘things’. As Appadurai (Citation1986) argues, ‘the buying and selling of expertise regarding the technical, social or aesthetic appropriateness’ (p. 23) of certain commodities is now valued more than ever. Thus, for the customer, seeing ‘Scandinavian’ in the context of a Singaporean market can be valuable, potentially imbuing the shop and its ‘things’ with positive connotations of the Scandinavian region or indexing international reach as an indicator of quality. The consumer who sees the Scandinavian semiotic resources constructs value for him/herself on the one hand and for the tailor shop on the other hand by, perhaps, buying its products but also narrating the story of the place and contributing to the distinction of the shop. In this way, they and the shop owner, through his sign-making, contribute to the contemporary increase in ‘a traffic in criteria concerning things’ (Appadurai, Citation1986, p. 34), or in other words knowledge about artefacts, which, in turn, shapes future scopic regimes and encounters with linguistic landscapes (cf. Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010). In this case, ways of seeing Scandinavian languages and their alignment with material goods were reconfigured, placing these languages on a palette of cosmopolitanism and modernity alongside French, Spanish, and Italian in the Singaporean context (Ong et al., Citation2013; Tan, Citation2011b).

This brings us to our next point, which is how the meaning and purpose of semiotic resources change over time. Even when the content of a particular sign on a linguistic landscape remains static, its function can change. If we take the original intention of the shop’s Scandinavian signs, we can see that it was a combination of an instrumental function – wanting to attract and communicate with sailors from Scandinavian countries in ‘their’ language to let them know that they could purchase suits in the shop – as well as a symbolic function. The symbolic function was, of course, central since the shop owner did not actually speak any Scandinavian languages and so could not converse with the sailors using them, yet he still wanted to communicate to his market the idea that they were a welcome and valued clientele. The choice of Scandinavian semiotic resources at this time, then, reflected primarily Ben-Rafael’s (Citation2009) principle of good reason to select a language for a sign based a specific target clientele (cf. Ong et al., Citation2013). However, it can be argued, the fact that European sailors used the tailor shop was also a valuable thing to communicate to other potential clients – local and international. As Adorno notes

foreign words become the bearers of subjective contents: of the nuances. The meanings in one’s own language may well correspond to the meanings of the foreign words in every case; but they cannot be arbitrarily replaced by them because the expression of subjectivity cannot simply be dissolved in meaning. (Citation1991, p. 287)

Over time, as the target market of Scandinavian sailors has waned, the instrumental function has almost totally been superseded by the symbolic function. The Scandinavian semiotic resources are now part of the history of the shop itself and also part of the history of the local area. They are, as Sweetland (Citation2002, p. 514) tells us, ‘unexpected but authentic’. They now serve a distinguishing function, following Ben-Rafael’s (Citation2009) principle of the presentation of self, in the linguistic landscape of Singapore (cf. Ong et al., Citation2013), making the shop stand out from its competitors and drawing in potential clients who are passing. The sign-making actions of one individual thus become part of a linguistic landscape that shows traces of the flows of languages around the world and their contact at a particular site of globalisation (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010). Our case study here demonstrates how such flows and contact are continuous rather than a one-off project; the meanings of signs and the languages chosen for them are negotiated and renegotiated again and again, resulting in ‘creative linguistic practices across borders of culture, history and politics’ (Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010, p. 240).

Conclusion

In sum, the present case shows the benefit of going behind the signs in the investigation of linguistic landscapes. In a study of the overall distribution of languages in Singapore’s Chinatown, a Scandinavian language on a single storefront would simply appear as an anomaly among a majority of Chinese and English signs. It would be easy to dismiss such an outlier as a curiosity given that Scandinavians are not substantially represented in contemporary Singaporean society. By charting the process of the visual semiosis of this tailor shop, we were able to demonstrate that its seemingly spectacular language use points to trajectories of globalisation that include Singapore’s place in the global shipping industry, the historical role of Scandinavians in it, and the shop owner’s personal experiences. What initially appeared unexpected, for us as researchers and also in light of previous studies of Singapore’s linguistic landscape, came to make sense when understood as a form of creative marketing in the context of these trajectories.

With respect to creative marketing, our study shows how it was facilitated here by the shop owner’s awareness of semiotic resources. Recognising the potential opportunity presented by the Scandinavian presence in the shipping industry, the owner sought guidance from a Norwegian acquaintance in order to be able to draw upon the semiotic resources needed to develop a customer base among Scandinavian sailors. The signs created at that time, we show, had a primarily instrumental function but also a secondary symbolic function that indexed the shop and its goods with value in a global market. The owner was able to use this secondary function to pivot his marketing strategy once the shop moved from Clifford Pier and the demographics among sailors shifted away from Scandinavians. By then, the shop’s semiotic connection to Scandinavia had strengthened such that it became integral to the shop’s image, which the owner was able to leverage in order to differentiate the shop in its new location in Chinatown and for a new, wider clientele. As we demonstrate, the owner was keenly aware of the strategic use of semiotic resources, inwardly in terms of his original act of sign-making and of his later decision to keep them as well as outwardly with respect to the impact of the signs on the customers who visit the shop and even those who are passing by. The former has been our focus in the present study, and the latter would certainly be a valuable avenue for future research.

Linguistic landscapes in multilingual cities like Singapore are sites in which to observe processes of globalisation. As our study shows, globalisation is not an abstract phenomenon but rather a concrete process that is manifested through the locally situated choices of individuals afforded by linguistic and economic flows that have the potential to result in innovative forms of expression, in this case the creative marketing of a tailor shop. The stories behind particular shops and their owners, like the one we have documented here, are worth telling because they offer insight into how and why linguistic landscapes take the shape they do.

Disclosure statement

The proprietor's and shop's names as well as all images are used with permission. The authors have no financial interests in Abba's Department Store.

Notes

1. The hyphen after DAM is omitted from the translation because it indicates only the morphological role of dam (women’s) as part of a compound word in Norwegian.

References

- Adorno, T. (1991). Notes to literature ( Vol. 2). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Agar, M. (1996). The professional stranger: An informal introduction to ethnography. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Appadurai, A. (1986). The social life of things. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin. (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Bell, A. (1999). Styling the other to define the self: A study in New Zealand identity making. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 3, 523–541. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00094

- Ben-Rafael, E. (2009). A sociological approach to the study of linguistic landscapes. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp. 40–54). London: Routledge.

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Chiapoco, J. (2005, November 28). The alley, it is a-changing. Today. Retrieved from http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/today20051128-1.2.26.7

- Curtin, M. L. (2009). Languages on display: Indexical signs, identities and the linguistic landscape of Taipei. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp. 221–237). London: Routledge.

- de Burgh-Woodman, H., & Brace-Govan, J. (2010). Vista, vision and visual consumption from the age of enlightenment. Marketing Theory, 10(2), 173–191. doi: 10.1177/1470593110366908

- Duff, P. (2007). Case study research in applied linguistics. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Eastman, C. M., & Stein, R. F. (1993). Language display: Authenticating claims to social identity. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 14(3), 187–202. doi: 10.1080/01434632.1993.9994528

- Hill, J. H. (1999). Styling locally, styling globally: What does it mean? Journal of Sociolinguistics, 3, 542–556. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00095

- Hult, F. M. (2009). Language ecology and linguistic landscape analysis. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp. 88–104). London: Routledge.

- Hult, F. M. (2014). Drive-thru linguistic landscaping: Constructing a linguistically dominant place in a bilingual space. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18, 507–523. doi: 10.1177/1367006913484206

- Hult, F. M. (2018). Language policy and planning and linguistic landscapes. In J. W. Tollefson & M. Pérez-Milans (Eds.), Oxford handbook of language policy and planning (pp. 333–351). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Iedema, R. (2003). Multimodality, resemiotization: Extending the analysis of discourse as multisemiotic practice. Visual Communication, 2, 29–57. doi: 10.1177/1470357203002001751

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2010). Introducing semiotic landscapes. In A. Jaworski & C. Thurlow (Eds.), Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space (pp. 1–40). London: Continuum.

- Jaworski, A., Thurlow, C., Ylänne-McEwen, V., & Lawson, S. (2003). The uses and representations of local languages in tourist destinations: A view from British TV holiday programmes. Language Awareness, 12, 5–29. doi: 10.1080/09658410308667063

- Jay, M. (1988). Scopic regimes of modernity. In H. Foster (Ed.), Vision and visuality: Discussions incontemporary culture No. 2 (pp. 3–27). Seattle: Bay Press.

- Kelly-Holmes, H. (2005). Advertising as multilingual communication. Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Kelly-Holmes, H. (2014). Linguistic fetish: The sociolinguistics of visual multilingualism. In D. Machin (Ed.), Visual communication (pp. 135–151). Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Edward Arnold.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

- Lim, S. H., Rosman, M. Z. M., & Goh, K. R. A. (2012). Linguistic landscape in Changi Airport. Retrieved from http://www.hss.ntu.edu.sg/Programmes/linguistics/studentresources/Documents/Report2012/SP2012_HG420_LimZulGoh.pdf

- Malinowski, D. (2009). Authorship in the linguistic landscape. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp. 107–125). London: Routledge.

- Ng, C. L. P. (2014). Mother tongue education in Singapore: Concerns, issues and controversies. Current Issues in Language Planning, 15(4), 361–375. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2014.927093

- Ong, K. K. W., Ghesquière, J. F., & Serwe, S. K. (2013). Frenglish shop signs in Singapore. English Today, 29(3), 19–25. doi: 10.1017/S0266078413000278

- Otsuji, E., & Pennycook, A. (2010). Metrolingualism: Fixity, fluidity and language in flux. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(3), 240–254. doi: 10.1080/14790710903414331

- Pennycook, A. (2012). Language and mobility: Unexpected places. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Pennycook, A., & Otsuji, E. (2017). Fish, phone cards and semiotic assemblages in two Bangladeshi shops in Sydney and Tokyo. Social Semiotics, 27(4), 434–450. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2017.1334391

- Rampton, B. (1995). Crossing: Language and ethnicity among adolescents. New York, NY: Longman.

- Shang, G., & Guo, L. (2017). Linguistic landscape in Singapore: What shop names reveal about Singapore’s multilingualism. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(2), 183–201. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2016.1218497

- Shang, G., & Zhao, S. (2017). Bottom-up multilingualism in Singapore: Code choice on shop signs. English Today, 33, 8–14. doi: 10.1017/S026607841600047X

- Shohamy, E., Ben-Rafael, E., & Barni, M. (2010). Linguistic landscape in the city. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Silver, R. E. (2005). The discourse of linguistic capital: Language and economic policy planning in Singapore. Language Policy, 4, 47–66. doi: 10.1007/s10993-004-6564-4

- Singapore Tourism Board. (2016). International visitor arrival statistics. Retrieved from https://www.stb.gov.sg/statistics-and-market-insights/marketstatistics/ivastat_dec_2015%20(as@29feb16).pdf

- Sweetland, J. (2002). Unexpected but authentic use of an ethnically-marked dialect. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 6, 514–538. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00199

- Tan, P. K. W. (2007). The struggle for a standard: Evidence from place names. Names: A Journal of Onomastics, 55(4), 387–396. doi: 10.1179/nam.2007.55.4.387

- Tan, P. K. W. (2011a). Mixed signals: Names in the linguistic landscape provided by different agencies in Singapore. Onoma, 46, 227–250.

- Tan, P. K. W. (2011b). Subversive engineering: Building names in Singapore. In S. D. Brunn (Ed.), Engineering earth (pp. 1997–2011). New York, NY: Springer.

- Tan, P. K. W. (2014). Singapore’s balancing act, from the perspective of the linguistic landscape. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 29(2), 438–466. doi: 10.1355/sj29-2g

- Tang, H. K. (2018). Linguistic landscaping in Singapore: Multilingualism or the dominance of English and its dual identity in the local linguistic ecology? International Journal of Multilingualism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2018.1467422

- Vigers, D. (2013). Sign of absence: Language and memory in the linguistic landscape of Brittany. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 223, 171–187.

- Wanting, N., & Min, S. S. S. (2012). Singapore’s linguistic landscape: A comparison between food centres located in Central and Heartland Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.hss.ntu.edu.sg/Programmes/linguistics/studentresources/Documents/Report2012/SP2012_HG420_NeoSoon.pdf