ABSTRACT

Multilingual identity is an area ripe for further exploration within the existing extensive body of identity research. In this paper we make a case for a conceptual framework that defines multilingual identity formation in terms of learners’ active involvement, and proposes the classroom as the hitherto underused site for participative identity (re)negotiation. After reviewing three key theoretical perspectives on identity (the psychosocial, sociocultural and poststructural) for points of intersection and difference, we propose a new framework for a multi-theoretical approach to the conceptualisation and investigation of multilingual identity. This places it at the nexus of (a) individual psychological development, (b), the relational and social, and (c) the historical and contextual. Arguing that a participative perspective can take the field forward, we present a theorised model for classroom practice that provides a structure within which individual learners of a foreign language might explore, with reference to a range of sociolinguistic knowledge, the extent of their current linguistic repertoire. In addition, they are asked to explicitly consider their identity and identifications and offered the agency to (re)negotiate these in terms of multilingual identity, the development of which may be important for investment in language learning.

1. Introduction

Identity remains one of the major constructs for debate and research in the early twenty-first century. Ethnic, religious, gender, class and personality aspects of identity, to name but a few, have become an individual, social and political field of contest. In this discursive space, definitions, boundaries and perceptions are examined and tested. The issue of identity has not only generated a great deal of debate and newspaper column inches, but has also been the focus of research that has flourished over the last twenty years in the areas of cultural studies, psychology and education. One area that needs more attention in the face of the increasing global movement of people, and which is the focus of our work, is that of linguistic identity and, in particular, multilingual identity. For the purposes of this paper we construe these two as associated but different; linguistic identity refers to the way one identifies (or is identified by others) in each of the languages in one’s linguistic repertoire, whereas a multilingual identity is an ‘umbrella’ identity, where one explicitly identifies as multilingual precisely because of an awareness of the linguistic repertoire one has.

Our conceptual framework defines multilingual identity formation in terms of learners’ active involvement in the language learning process, using the classroom as the site for participative identity (re)negotiation. Here we take an encompassing view of multilingualism, viewing all learners engaged in the act of additional language learning in classroom contexts as multilinguals, regardless of the number of additional languages or dialects in their repertoires, though they may not identify as such. In addition, we argue that research in the area would benefit from adopting a multi-theoretical approach in the conceptualisation and investigation of multilingual identity.

In this paper a case is made for using the language classroom as a site where learners are offered the agency to develop a multilingual identity. In order for this to happen we argue that learners need sociolinguistic knowledge in order to understand and explicitly reflect on the languages and dialects in their own and others’ linguistic repertoires, whether learned in school, at home or in the community. We see the development of a multilingual identity as potentially important for two main reasons: a) if learners adopt an identity as a multilingual they may be more likely to invest effort in the learning and maintenance of their languages b) with increasing mobility and greater diversity in communities and classrooms a multilingual mindset might lead to enhanced social cohesion in the school and beyond.

We begin with a discussion of the chief characteristics of three key theoretical perspectives on identity and the self (the psychosocial, sociocultural and poststructural) and consider points of intersection and difference between them, with a view to making a case for a multi-theoretical approach to identity research. Section two examines the relationship between language and identity within the above framework, and sets out our conceptualisation of multilingual identity. Section three considers empirical research carried out in multilingual identity, including studies in the FL classroom. Finally, within the context of the existing literature on identity formation, we consider how a participative perspective can take the field forward, arguing that identity might be theorised as participative processes within a multi-theoretical framework. We engage with the concept of explicit ‘identity education’, which has been defined by Schachter and Rich (Citation2011) as ‘the purposeful involvement of educators with students’ identity-related processes or contents’ (p. 222), where the teacher has a key role as facilitator. Hitherto underused as a space for participation in identity formation, we present a model for classroom practice that provides a structure within which individual learners might exercise their agency in developing a multilingual identity.

2. Conceptualising identity: three theoretical perspectives

A key argument made in this paper is that identity is a highly complex construct and, as such, does not conform to ‘a single, coherent theoretical approach. Rather it contains a set of features that may be common to various theoretical frameworks’ (Varghese, Morgan, Johnston, & Johnson, Citation2005, p. 23). Any discussion of identity is also inextricably bound with the notion of the ‘self’, conceptualisations of which have similarly grown out of different theoretical and disciplinary traditions. This has led to wide variation in the way in which researchers define these terms both individually and in relation to each other (Leary & Tangney, Citation2003; Vignoles, Schwartz, & Luyckx, Citation2011). To this end, we begin by providing a brief overview of three of the key frameworks for understanding and researching identity, the psychosocial, sociocultural and poststructural, with a view to identifying both points of intersection and points of divergence.

The work of Erikson (Citation1968) has been pivotal in establishing theories of identity from a developmental psychological perspective. Erikson viewed identity formation as a multidimensional, psychosocial, developmental process, which included both individual and social-contextual dimensions. As such, he was credited as being among the first to ‘straddle the conceptual fence between the intrapsychic focus adopted by psychology and the environmental focus adopted by sociology’ (Schwartz, Citation2001, p. 8).

In relation to the individual element of identity, Erikson made a distinction between the psychological dimension, or ego identity, and the more behavioural dimension, which he referred to as personal identity. He was also careful to distinguish between ‘identity’ and the ‘self’. Within such a framework, the ‘self’ can be considered not only as the inner psychological entity that is at the centre of a person’s experiences, but also as the apparatus that allows an individual to think consciously and reflectively about themselves and to regulate their own behaviour (Leary & Tangney, Citation2003). Identity, on the other hand, is often considered to be a construct of the self (Leary & Tangney, Citation2003), the formation of which is viewed as a long-term, developmental process that progresses through a number of stages. However, ‘the major struggles of identity fall primarily on adolescents, for whom the establishment of secure identities is critical for passage into the adult world’ (Ryan & Deci, Citation2003, p. 254). The social dimension, or social identity, which relates to the way in which individuals define themselves ‘in a particular historical, cultural, and sociological time period’ (Oyserman & James, Citation2011, p. 119), is also seen as important in shaping an individual’s identity development. Erikson considered the role of external factors such as parents and society on an individual’s development from childhood to adulthood, and took into account the way in which sociocultural processes shape individual choices.

The existence of a core identity also constitutes a fundamental part of psychosocial identity theory, largely because of the way in which the ‘self’ is theorised within such a framework. Although Erikson acknowledges that an individual will have a variety of identities, he maintains that they are integrated into a coherent, core identity which develops over time, (Erikson, Citation1968). He suggests that this core identity connects us with our past and future, and from a theoretical perspective allows for a discussion of possible identities which ‘provide a goal post for current action and interpretive lens for making sense of experience’ (Oyserman & James, Citation2011, p. 117). Erikson’s work on identity theory led to a substantial body of research on identity from a psychological perspective, such as Marcia’s (Citation2007) identity status typology and Berzonsky’s (Citation2011) identity style inventory. However, these neo-Eriksonian models have had a tendency to operationalise Erikson’s research in largely psychological terms and have consequently been accused of neglecting the sociological perspectives incorporated by Erikson (Côté & Levine, Citation1987). Côté and Levine (Citation1987) further highlight the need to take a more interdisciplinary approach to identity formation.

Like the psychosocial theories of identity outlined above, sociocultural perspectives similarly consider both the individual and the social. They also draw on poststructural or postmodern theories which accentuate the agency of the language learner (Lankiewicz, Szczepaniak-Kozak, & Wasikiewicz-Firlej, Citation2014). Despite these overlaps, sociocultural perspectives give analytic primacy to the role of social, historical and cultural contexts, such as a classroom, and the way in which these shape the individual. From a sociocultural perspective, identity is therefore viewed as being socially-constructed rather than developed and as such is believed to be mediated, relational and situated.

Such sociocultural perspectives are often associated with the work of Vygotsky. Although he was not directly concerned with identity and did not use the term in his writing, Vygotsky considered that ‘individual mental functioning can be understood only by going outside the individual and examining the social and cultural processes from which one is constructed’ (Zembylas, Citation2003, p. 220). As such, identity formation is necessarily mediated by social contexts and interactions (Adams, Citation2009; Norton & Toohey, Citation2011). As a result, identity from a sociocultural perspective must be viewed as situated and by extension, may be framed in terms of individual participation in communities of practice. For Lave and Wenger (Citation1991), for whom learning and identity are inseparable, identities can be considered as ‘long-term, living relations between persons and their place and participation in communities of practice. Thus identity, knowing, and social membership entail one another’ (p. 53); full participation in practice involves becoming part of the community. As Block (Citation2007) has argued, within such a framework identity is both ‘constitutive of and constituted by the social environment’ (p. 25).

A number of researchers, such as Vågan (Citation2011) and Park (Citation2015), advocate strongly for taking a sociocultural approach to exploring identity formation within educational contexts, due to a focus on social interactions. Norton and Toohey (Citation2011) also highlight the importance of paying ‘careful attention to the activities provided for learners in their diverse environments and to the qualities of the physical and symbolic tools, including written language, that learners use’ (p. 419). Sociocultural identities also tend to be considered as multiple and provisional, which contradicts the notion of a core identity, a fundamental construct in psychosocial identity theory.

Poststructuralists similarly reject the existence of a singular core identity by emphasising the impossibility of a fixed self. Within this framework, identities are conceptualised as incomplete, ‘constantly becoming’ (Zembylas, Citation2003, p. 221) and ‘contradictory’ (Fawcett, Citation2012). This opens up the possibility for exploring self-transformation and change which may be non-linear, in contrast to the more logical developmental process of change which is characteristic of the psychosocial perspective. Poststructuralists frame identity as socially constructed and historically situated. In addition to self-transformation, change may also be influenced by social and relational factors, which resonates with the sociocultural perspectives outlined above. In line with this, Block (Citation2007) emphasises that identities are negotiated ‘at the crossroads of the past, present and future’, while Norton and Toohey (Citation2011) posit that identity is both ‘context-dependent and context-producing, in particular historical and cultural circumstances’ (p. 420). Identity from a poststructural perspective is therefore believed to be dynamic, multiple, shifting and socially constructed (Fawcett, Citation2012). However, while there are undoubtedly a number of points of convergence with the sociocultural perspectives outlined above (see below), analytic primacy here is often given to issues of power and/or (self) transformation.

Poststructuralism, and in particular the sense of agency it attributes to individuals, has been considered therefore as particularly helpful ‘in theorizing how education can lead to individual and social change’ (Norton & Toohey, Citation2011, p. 417). For these authors, identity is ‘the way a person understands his or her relationship to the world, how that relationship is constructed across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future’ (Norton & Toohey, Citation2011, p. 417). On the one hand, there is an awareness of the importance of taking into account an individual’s ‘complex social history’ (Norton Peirce, Citation1995, p. 9), for example in understanding their attitudes towards learning, and, on the other, is the promise of benefits that one may be afforded through learning in the future. These impact identity given that such practices involve ‘organising and reorganising a sense of who [one is] and how [one relates] to the social world’ (Norton Peirce, Citation1995, p. 9).

As with both of the previous perspectives outlined above, therefore, a poststructuralist stance on identity involves both the individual and the social, rejecting the idea that it can be considered as purely a psychological or a sociological issue. However, while poststructuralism as a framework for exploring identity has been considered by some as an integration of the psychological and the sociological (e.g. Zembylas, Citation2003), it has been criticised by others for marginalising ‘the traditional interests of psychologists in the self’ (Block, Citation2006, p. 35) and neglecting the possibility that there may be aspects of identity that are core and remain stable and that, as Erikson would argue, connect us to our past and allow for a planning of possible future identities.

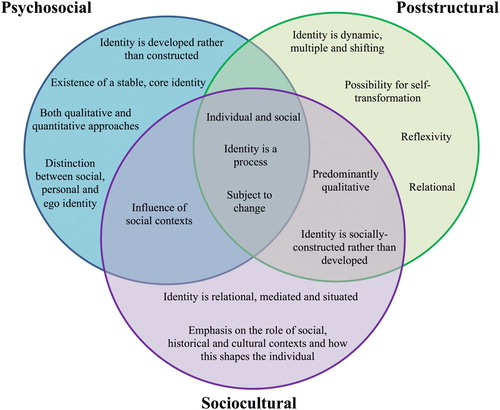

Looking at the key features of each of the three perspectives described above, it is evident that there are differences, but also key areas of overlap in their various conceptualisations of identity, as shown in .

Each of the perspectives acknowledges that:

Identity is both an individual and a social phenomenon;

Each contains a focus on identification as a process rather than a fixed condition;

As such, there is the possibility that at least some aspects of identity are subject to change and we are able, at least to some extent, to actively create our identities.

3. Language and identity: epistemological perspectives

Any study on linguistic identity needs to consider the role that language plays in identity construction. The complexity of the relationship between language and identity arises from the fact that identity is both the source and the product of language practice; not only do languages shape identities, but identities also shape language (Joseph, Citation2004). As such, Joseph (Citation2004) refers to the ‘language-identity nexus’ (p. 12), where these are seen as ‘inseparable’ constructs. The language and identity relationship, he says, rests on the following tenets:

Language identities are multiple, and shift depending on who you are interacting with (both how you present yourself, and how others perceive you), and connected to this, the context in which the interaction takes place (p. 8)

Both ‘language’ and ‘identity’ have been often considered in terms of verbs (processes), rather than nouns (static constructs), as a way of encapsulating the inevitable shifts and adaptations that take place across time and space within both (p. 10).

Each of the perspectives outlined above also entails a particular theoretical and methodological positioning as regards language, linguistic repertoire and identity. For those operating in a social psychological framework, language is the means by which developmental stages can be expressed, though this usually runs the risk of ‘essentialising’, given the epistemological stance that such stages can be captured using methods such as surveys and other trait approaches. Measures are adopted depending on whether researchers want to know if identity is causing a person to do a particular thing (an independent variable), or if something causes a person to adopt a particular identity (a dependent variable) (Abdelal, Herrera, Johnston, & McDermott, Citation2009).

For poststructuralists language is both ‘constitutive of’ and ‘constituted by’ a language learner’s social identity (Norton Peirce, Citation1995, p. 13). Duff’s (Citation2015) perspective on language and identity within poststructuralism is that it incorporates ‘subjectivities [being] inculcated, invoked, performed, taken up, or contested in particular discursive spaces and situations in a moment-by-moment way’ (p. 62), where ‘subjectivities’ refers to negotiated, relational, and ‘non-essentialised’ identities. From a poststructural perspective it is therefore important to conceptualise language identity as ever-shifting, dynamic and inextricably bound up with language performance. This placing of emphasis on the situatedness and dynamism of identity entails empirical work which relies mainly on first person accounts to understand the depth and complexity of identity in relation to language/s use. As suggested by Norton (Citation2013), researchers who position themselves as poststructuralist consider that ‘a quantitative research paradigm relying on static and measurable variables will generally not be appropriate’ (p. 13) and tend to draw instead on approaches related to narrative inquiry, case studies or ethnography.

Sociocultural perspectives on the role of language in identity are largely in tune with those of poststructuralists, where language is conceived also as a tool of thought and with a primary mediating function (Toohey & Norton, Citation2010). Again, largely qualitative methods are used to examine how language mediates human activity in particular social contexts.

Turning to a person’s different linguistic identities, these differ in their expression, not only through language, but across a range of semiotic resources in different contexts and at different times. Each language in one’s multilingual repertoire is subject to adaptation and movement, where levels of proficiency, for example, might fluctuate across the lifespan depending on a range of factors including migration or social networks. Arguably therefore, while identities associated with different languages in our multilingual repertoire might change spatio-temporally, an identity as a multilingual might remain ‘core’. This can be seen not as essentialising multilingual identity, but as allowing through language for something that can perform a function in building an awareness both of one’s multilingual repertoire and of how one is identified by others.

Incorporating elements of a poststructuralist tradition means understanding the importance of not falling into the trap of ‘essentialising’ identities, whether identities associated with our various languages or that of the multilingual self, but leaving space nonetheless for a possible ‘core’ element. This is consistent with Joseph, who warns of the potential danger of failing to engage with essentialised notions in identity explorations:

The methodological ideal is […] to strive for the intellectual rigour of essentialist analysis without falling into the trap of believing in the absoluteness of its categories, and to maintain the dynamic and individualistic focus of constructionism while avoiding the trap of empty relativism. […] To reject essentialism in methodology is to say quite rightly that our analysis must not buy into the myth, but must stand aloof from it to try to see how it functions and why it might have come into being in the belief system or ideology of those who subscribe to it. Yet there must remain space for essentialism in our epistemology, or we can never comprehend the whole point for which identities are constructed. (Joseph, Citation2004, p. 90)

4. A multi-theoretical approach to investigating identity

Our position is therefore that, when researching a concept as complex as identity, it is limiting to restrict oneself to working within the confines of a single theoretical or methodological perspective. Indeed, lthough the most influential perspective on identity within the field of second language learning has undoubtedly been a poststructuralist one (Norton & Toohey, Citation2011; Schreiber, Citation2015), having become the ‘default epistemological stance’ (Block, Citation2006, p. 34), Block notes that this should not necessarily preclude other approaches and suggests that researchers still have a tendency to uncritically situate their research within an established, yet at times ‘theoretically impoverished epistemological playing field’ (p. 46). There are exceptions insofar as some researchers are not explicit about their theoretical stance at all and other scholars, including the most influential (for example, Norton), have drawn on both the sociocultural and poststructural at different times and for different purposes. In line with Block would argue that just as defining and researching identity crosses traditional boundaries between disciplines (Bilá, Kačmárová, & Vaňková, Citation2015; Holliday, Hyde, & Kullman, Citation2004), it similarly transcends the boundaries of a single theoretical perspective. This approach follows in the tradition of identity research described by Omoniyi (Citation2006) as both ‘multi-theoretical and multidisciplinary’ (p. 14) and by Kostoulas and Mercer (Citation2016) who argue that ‘integrating differing perspectives is more likely to create a richer understanding of the self in the long run’ (p. 130).

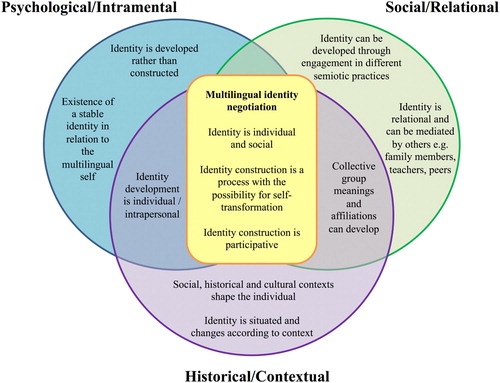

The key characteristics of our understanding of multilingual identity are modelled in . Mapping loosely to the theoretical perspectives in , in our framework multilingual identity is constructed at the interface of three domains of experience:

the individual (psychological development and cognition);

the relational and social (interpersonal interaction in social situations where collective or group meanings and affiliations can develop);

the historical and contextual (where identity is situated and can fluctuate over time).

The key features of our conceptualisation are as follows:

This process of identity construction is both naturalistic, in the sense of individual ‘development’ over time and so has a psychological/intramental dimension which is in response to lived experience, and also is fashioned in the sense of being shaped by external influences, including schooling.

An individual’s identity is constructed through engagement in different semiotic practices and interactions, including those involving languages. Hence it has a social and relational dimension.

Such semiotic practices arise historically and in specific contexts. Individuals can be helped to make meaning in terms of their identity and identifications, by understanding how and why such practices may have evolved in their particular contexts.

Identity is defined primarily as an action, a variable process of identification, rather than as a fixed, singular or ‘immanent’ feature of the self, although there remains the possibility of stability in relation to a self that connects future, present and past.

In order to identify, individuals need to be reflexive about the (multilingual) self.

Multilingual identity formation is, therefore, a participative process, both individual and social.

Our multi-theoretical approach to multilingual identity is, therefore, situated at the nexus of these perspectives.

Before proposing our own framework for the participative construction of multilingual identity in the languages classroom, the ways in which other researchers in the area of second language education have approached the epistemological and methodological issues in identity research are considered in the next section.

5. Multilingual/linguistic identity research in educational contexts

The theoretical and conceptual perspectives on language and identity we have outlined in earlier sections have largely dominated the recent growth in empirical research conducted in the educational context. In particular, the social context of identity construction and representation has shaped researchers’ investigations with varying degrees of emphasis given to the sociocultural, psychosocial, or poststructuralist paradigms. As discussed above, linguistic identity is often seen in poststructuralist terms as situated, fluid and mediated by multimodal semiotic resources. This fluidity is framed either in terms of the learners’ negotiation of their multilingual identity backgrounds or in terms of how this profile adjusts to the experience of additional language learning. In general, and a little in conflict with the social perspective explicitly adopted by the researchers, the construct of linguistic identity is operationalised through evidence produced by a combination of individual participants’ creative, often visual, representations of their linguistic identity and their more explicit verbal reflections. The source of evidence, therefore, is usually grounded in individual perceptions rather than in social or educational interaction. The brief review we now present serves the purpose of locating our own proposed participative framework against the background of recent empirical studies.

Broadly, three salient groups of studies have emerged in the field. One strand of studies has centred on the use of multimodal identity-focused elicitation tasks aimed at generating learners’ thinking and perceptions about aspects of their linguistic identity, often relating this to future language learning projections. The majority of these studies draw on evidence from multilingual, migrant-background learners at elementary school. The conceptual focus is therefore on multilingual pupils’ views of their own linguistic identities as speakers of different languages rather than, strictly speaking, on a more generic conceptualisation of multilingual identity. Some have used the technique of exploring ‘visual narratives’ accompanied by oral accounts of, mostly, elementary school learners’ representations of their linguistic identity (Besser & Chik, Citation2014; Cummins, Hu, Markus, and Kristiina Montero (Citation2015).; Dressler, Citation2015; Ibrahim, Citation2016; Levine, Citation2013; Martin, Citation2012; Melo-Pfeifer, Citation2015; Welply, Citation2015). Melo-Pfeifer (Citation2015, p. 198), for instance, adopts a ‘socio-constructive’ view of the concept of ‘multilingual awareness’ in her study, and her analysis of the multimodal data from Portuguese heritage pupil participants in primary schools in Germany provides vivid insights into the children’s representations and allows her to discern ‘patterns of experiences and feelings about those experiences’ (p. 198) defined by linguistic identity. Similarly, Levine (Citation2013) in her case studies of the multilingual identity representations of 10–11-year-old pupils at a primary school in England, generated evidence including drawings and visual mapping to find a complex picture in which some of the children perceived themselves as monolinguals and others as multilinguals, while for some children there was tension and contradiction in their presentation of their linguistic identities. Arguably, the narratives, texts and other procedures used in many of these studies are insightful more as examples of dynamic processes of identification rather than for the particular identity traits depicted.

A second strand of research enquiry in this area has taken the form of introspective studies that focus on evidence of more directly articulated self-representations of multilingual identity by second, heritage or foreign language learners (Scott, Dessein, Ledford, & Joseph-Gabriel, Citation2013; Taylor, Citation2013). These studies, often using questionnaires or semi-structured interviews, define learners’ explicit dispositions and identity positioning as language learners. This perspective has been comparatively more attractive to researchers of foreign language learning as it has overlapped with the more traditional research focus of language learner motivation, within a psychosocial tradition, and in particular as theorised in accounts of the L2 motivational self system (Dörnyei, Citation2009) or through reference to the notion of linguistic multi-competence (Cook & Wei, Citation2016).

Finally, a third perspective in this research area has focused on the influence of contexts in which the linguistic identities of learners play out. Context in this sense has been interpreted in different ways including, and of particular interest to educational considerations, the following: institutional context, learning context, and modality context. Ceginskas (Citation2010), for instance, interviewed 12 adults (aged 20–50) of different L1 backgrounds living in Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands or Belgium, most of whom had received part of their schooling in the host country. Ceginskas found that the extent to which the participants displayed a sense of ‘multilinguality’ depended on the sociocultural influence of the schools they had attended (state school or international school), and the period of their schooling. In the foreign language learning context, Schweiter (Citation2013) has considered the link between development of identity and foreign language investment through a project involving the creation of a magazine by English L1 university students of Spanish as a foreign language in Canada. The online environment represents a further fertile context in which multilingual identity and language learning can interact and develop. In fact, the context is increasingly construed as more than a space in which multilingual identity can develop but as a mediating factor in that development (Chen, Citation2013; Kim, Citation2016; Lam, Citation2000), though the extent to which this identification transfers to the individual’s everyday life in the non-virtual world remains underexplored.

The field of research in multilingual identity and language learning is, as we stated earlier, still in a relatively early phase of development. The themes which have dominated researchers’ attention so far include the following: multilingual awareness; multilingual habitus; identity narratives and representations; multilingual identity and motivation to learn additional languages; the role of imagery and the imagination. The evidence presented in the published studies to date, however, has mostly come from small scale research or case studies. Moreover, from a pedagogical point of view there is as yet very little attempt to relate the kinds of identity-focused aims and activities discussed above to existing mainstream foreign language classroom pedagogy. Nor, more importantly, has there been research measuring the effects of a systematic pedagogical intervention aimed at fostering multilingual identity within the context of classroom-based additional language learning, something advocated by Henry and Thorsen (Citation2017) in relation to development of the multilingual ideal self. The following section of this paper outlines what such an approach might look like.

6. A framework for participative construction of multilingual identity in the language classroom

The process of education has a fundamental role to play in identity formation (Lamb, Citation2011; Lestinen, Petrucijová, & Spinthourakis, Citation2004; Nasir & Cooks, Citation2009; Schachter & Rich, Citation2011) and Wenger (Citation1998), for example, argues strongly that ‘learning transforms our identities: it transforms our ability to participate in the world by changing all at once who we are, our practices, and our communities’ (p. 226). The process and practice of languages learning in the classroom is therefore already likely to impact on a learner’s identity, as noted by Kramsch:

For young people who are seeking to define their linguistic identity and their position in the world, the language class is often the first time they are consciously and explicitly confronted with the relationship between their language, their thoughts, and their bodies. Engaging with a different language sensitizes them to the significance of their own first language and of language in general. (Kramsch, Citation2006, p. 5)

As seen in earlier sections, identity can be influenced by individual, social and contextual factors. However, there is an underlying assumption that this will occur tacitly, without the teacher drawing explicit attention to what is happening to pupils through the process of language learning. We argue that this process needs to be explicit and participative; learners need to engage in the active and conscious process of considering their linguistic and multilingual identities and to become aware of the possibility of change in relation to these identifications.

This is important for two reasons. First, developing learners’ awareness as to how they identify, and are identified, confers agency, and as The Douglas Fir Group argue ‘agency and transformative power are means and goals for language learning’ (Citation2016, p. 33). Second, classrooms are increasingly diverse, reflecting the increased mobility of people. If such identity work, where learners are able to make visible, potentially celebrate, become aware of the potential for drawing on the cross-linguistic resources available to them in their language (and other) learning is not being done in the languages classrooms, then where?

Here we differentiate between a) the various linguistic identities one might have relating to each of one’s various languages or dialects and b) an overarching multilingual identity that encompasses these individual identities. Clearly, as discussed earlier, discrete linguistic identifications may fluctuate tempo-spatially, influenced, for example, by one’s engagement with or current proficiency in particular languages. We are concerned with how an explicit, and potentially more stable, multilingual identity may be developed and, in particular, in the role of classroom practices in fostering such an identity. To return to the multi-theoretical framework () that situates language learner multilingual identity at the nexus of the three approaches to identity research, we view psychological/intramental aspects as important…, first because identity formation during adolescence undergoes a developmental phase where self-concept is evolving (Ryan & Deci, Citation2003; Collett, Citation2014; Taylor, Busse, Gagova, Marsden, & Roosken, Citation2013) and second because there may well be aspects of a multilingual identification that, once established, remain more stable. This is not to ‘essentialise’; multilingual identity may still undergo change over time and space. However, as it is not directly related to notions of competence and proficiency as the individual languages in one’s repertoire often are (and so is potentially less open to fluctuations), it is possible that an all-embracing multilingual identity seeded in adolescence could provide a basis on which a self as a learner and user of languages can build. This may provide positive impetus for current and future language learning, as Henry also argues with relation to the multilingual self (Citation2017). The model draws on the social and relational affordances of the foreign language classroom environment as a hitherto underused space where linguistic and multilingual identities can be explicitly engaged with.

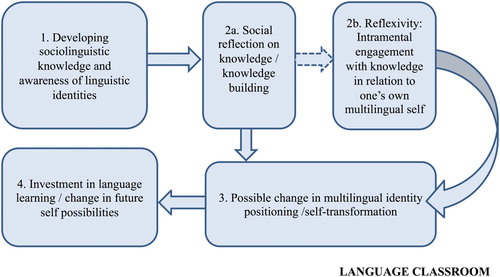

Building on this we present in a framework for generating a participative approach to multilingual identity formation. This has four key stages and is currently being empirically tested in a longitudinal, classroom-based study involving teachers and language learners in the early years of secondary education. The research draws on a wide range of data gathering instruments to explore what happens when learners are exposed to sociolinguistic knowledge aimed to generate understanding of their own linguistic repertoires, followed by the space to discuss and reflect on it. Aware that languages teachers have heavy curricula to deliver, the process outlined below is intended to be achievable within 6–10 hours of classroom time over the course of an academic year. The stages of the model are explicated below.

Figure 3. A framework for participative construction of multilingual identity in the language classroom.

6.1. Stage 1: sociolinguistic knowledge: awareness of linguistic identities

The first premise is that, before any work on multilingual identity can be done in the classroom, learners need to understand their own linguistic repertoires and those of people around them. For this they need ‘powerful knowledge’ (Young & Muller, Citation2013), for example here, sociolinguistic knowledge. We argue that learners’ lack of understanding about the semiotic practices that have emerged in their contexts, fundamentally, for example, what it means to learn and to ‘know’ a language, might mean they are less likely to appreciate the full extent of their own linguistic repertoire. For example, if I believe that I need to be fluent in a language in order to identify as a speaker of that language, I am likely to downplay the extent of my own linguistic repertoire, so making it less likely that I would identify as multilingual. Key here are ethical concerns. Learners are within their rights to identify as they wish and, as we know, multilingualism is not an uncontested value (Blackledge & Creese, Citation2010). In order to make informed choices, however, learners need exposure to information that includes answers to a number of questions, including: What is a language? How does it differ from a dialect? Which languages are spoken in the world and around me (i.e. the linguistic landscapes in their community, both within and beyond the school)? Which varieties exist of the language/s I am studying and where are they spoken? What does it mean to be ‘bilingual’ or ‘multilingual’ and who determines this? Some of the (necessarily simplified) knowledge needed to address these questions will have a contextual and historical dimension, such as the body of knowledge that exists in the second language acquisition research field (about language variety, language and cognition, communicative competence, for example) and can be transmitted through teacher presentation of materials such as factsheets, talking head videos, websites. Other knowledge will already reside with members of the teaching group (for example, the languages spoken in our community and our school and the nature of such languages) and teachers can encourage students to share this e.g. by presentation or in discussion. How this input can be explored further is discussed in Stage 2.

6.2. Stage 2: classroom as a site for participation and engagement

6.2.1 Reflection and knowledge building in relation to multilingual identity

As is clear from most educational research on how we learn, input is not enough (Sousa, Citation2017); we learn by taking new knowledge and building it into our conceptual frameworks, which requires cognitive engagement. Given that the form of potential learning under investigation here, multilingual identity formation, is necessarily mediated by social contexts and interactions (Adams, Citation2009; Norton & Toohey, Citation2011), in Stage 2 learners are required to engage with the sociolinguistic knowledge from Stage 1, not just intramentally, that is by building it into their own knowledge schema (for example through making links with the previously known), but in interaction with peers and the teacher in a variety of participative activities. Learners reflect together on what they have heard in Stage 1 and what it might mean in the learning context in which they find themselves, and so engage in different semiotic practices in the classroom. For example, having heard more about (un)balanced bilingualism, learners reflect on what that means for foreign language learning and when a person might be able to say they ‘know’ or ‘can speak’ a language. In this stage, discussion of the role of the ‘other’ in ascribing, legitimising or rejecting elements of linguistic identity might be important in understanding the extent of one’s linguistic repertoire and therefore forming or possibly legitimising a learner’s multilingual identity. Learners will encounter also the way that others value (or not) language learning and multilingualism generally. Through relational and contextual interaction, guided by the teacher, collective group meanings can potentially develop. One key question here is whether this sort of dialogic engagement at a class, group or dyad level is enough for identity (re)negotiation. It may be enough for knowledge building, but do learners implicitly relate the new knowledge to themselves and their lives and so potentially transform their identifications? Or does there also need to be explicit prompts to help them relate what they experience/learn to the self, where learners practise reflexivity in order that their multilingual identity is shaped in some way?

6.2.2 Reflexivity: intramental engagement for developing multilingual identity

A further stage therefore requires learners to consider how what they have experienced relates to them individually. Reflexivity is defined by Archer (Citation2012) as ‘the regular exercise of the mental ability, shared by all normal people, to consider themselves in relation to their (social) context and vice versa’ (p. 1). The teacher, therefore, introduces prompts and activities which ask learners to explicitly apply aspects of the knowledge introduced in Stage 1 and Stage 2 to their own situation. This stage is guided by key questions such as: What does this mean for me? Has my thinking changed? What surprised me about this information? How does this new information make me feel? Do I want to do anything differently? The idea is that in doing so they incorporate this new knowledge not only into their cognitive frames (as might the learners engaged only in Stage 2a), but that in finding personal meaning in the material, which might entail an emotional dimension as work on the self often does, multilingual identity might be shored up or shaped in some way differently. It might well be that oppositional multilingual identities, that is to say, defining oneself by identifying what one is not (Skerrett, Citation2013, p. 327), is also an important aspect of this stage.

6.3. Stage 3: possible change in current multilingual identity positioning

As a result of their participation in Stages 1 and 2, learners may use the agency made more explicitly available to them to reconceptualise their identities, for example, by choosing to identify specific languages or indeed dialects as part of their linguistic repertoire, as they understand better that the choice to do so is theirs. In turn, they may or may not decide to identify as multilingual. It may, of course, also be that our empirical research shows that receiving new knowledge, whether from the teacher or from classmates’ input, hearing others’ views and then reflecting, will have no effect on their identifications.

6.4. Stage 4: change in future self possibilities/investment in language learning

The final stage in the framework we present is in future self possibilities as potentially manifested in investment in language maintenance and learning. ‘Investment’ (a sociological counterpart to ‘motivation’ in the field of second language acquisition developed by Norton, Citation2013) is a way of understanding the necessarily complex relationship between an individual’s identity as a learner of a language, and the extent to which they value, and devote time and effort to, the process of actually learning the language. If, as Archer argues, ‘the prime social task of our reflexivity is to outline, in broad brush strokes, the kind of modus vivendi we would find satisfying and sustainable within society’ (Archer, Citation2012, p. 15), then it is possible that participating in reflexivity, developing better understanding of languages in their repertoire and so (re)negotiating a multilingual identity, could have an action outcome in the future, where choices about what, how and with what degree of effort learners’ energies should be directed.

7. Conclusion

In this paper we offer a new conceptualisation of multilingual identity negotiation, theorised as participation and situated within a multi-theoretical framework. Our review of the literature, relating more generally to wider epistemological assumptions in defining identity, as well as that which focuses on the relationship between identity and multilingualism, has led us to situate our representation of multilingual identity within a multi-theoretical framework that draws on key aspects of psychosocial, sociocultural and poststructural approaches to identity (see ). Our model, which conceptualises identity as situated at the nexus of a. individual psychological development, b. the relational and social and c. the historical and contextual, offers a solution to the ongoing ontological and epistemological failure to address the psychological and the social in identity research (Block, Citation2006).

This, together with our review of the research literature on multilingual identity, has led us to construct a framework for participative multilingual identity negotiation, which we are testing empirically, answering the call for more research exploring the significance of encouraging identity development in the foreign language classroom (Collett, Citation2014; Taylor et al., Citation2013). Its development has been influenced by our interest in adolescent identities within predominantly Anglophone educational settings (such as the United Kingdom), though the framework is intended for application in myriad (educational/ social/ linguistic) contexts worldwide. Within the structure of the foreign languages classroom as a participative space, we explore how learners, whatever their linguistic repertoire, may be provided with the agency to examine their identity as users of their individual languages and how this might serve to develop an umbrella multilingual identity.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, for its support in funding this project under the auspices of Open World Research Initiative and Dr Dieuwerke Rutgers and Harper Staples for helpful input into discussions of conceptual frameworks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y. M., Johnston, A. I., & McDermott, R. (2009). Introduction. In R. Abdelal, Y. M. Herrera, A. I. Johnston, & R. McDermott (Eds.), Measuring identity: A guide for social scientists (pp. 1–13). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Adams, L. L. (2009). Techniques for measuring identity in ethnographic research. In Y. M. Abdelal, Y. M. Herrera, A. I. Johnston, & R. McDermott (Eds.), Measuring identity: A guide for social scientists (pp. 316–341). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berzonsky, M. D. (2011). A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In S. J. Schwartz, V. L. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 55–76). New York: Springer.

- Besser, S., & Chik, A. (2014). Narratives of second language identity amongst young English learners in Hong Kong. ELT Journal, 68(3), 299–309. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccu026

- Bilá, M., Kačmárová, A., & Vaňková, I. (2015). Adopting cross-disciplinary perspectives in constructing a multilingual’s identity. Human Affairs, 25(4), 3. doi: 10.1515/humaff-2015-0035

- Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2010). Multilingualism: A critical perspective. London: Continuum.

- Block, D. (2006). Identity in applied linguistics. In T. Omoniyi & G. White (Eds.), Sociolinguistics of identity (pp. 34–49). London: Continuum.

- Block, D. (2007). Second language identities. London: Continuum.

- Ceginskas, V. (2010). Being “the strange one” or “like everybody else”: School education and the negotiation of multilingual identity. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7( June 2014), 211–224. doi: 10.1080/14790711003660476

- Chen, H.-I. (2013). Identity practices of multilingual writers in social networking spaces. Language Learning and Technology, 17(2), 143–170.

- Collett, J. M. (2014). Negotiating an identity to achieve in English: Investigating the linguistic identities of young language learners (Doctoral dissertation). University of Berkeley.

- Cook, V., & Wei, L. (Eds.). (2016). The Cambridge handbook of linguistic multicompetence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. (1987). A formulation of Erikson’s theory of ego identity formation. Developmental Review, 7, 273–325.

- Cummins, J., Hu, S., Markus, P., & Kristiina Montero, M. (2015). Identity texts and academic achievement: Connecting the dots in multilingual school contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 49(3), 555–581. doi: 10.1002/tesq.241

- Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- The Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100, 19–47. doi: 10.1111/modl.12301

- Dressler, R. (2015). In the classroom exploring linguistic identity in young multilingual learners. TESL Canada Journal, 32(1), 42–52.

- Duff, P. A. (2015). Transnationalism, multilingualism, and identity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 57–80. doi: 10.1017/S026719051400018X

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Fawcett, B. (2012). Poststructuralism. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 667–670). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412963909

- Henry, A. (2017). L2 motivation and multilingual identities. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 548–565. doi: 10.1111/modl.12412

- Henry, A., & Thorsen, C. (2017) The ideal multilingual self: Validity, influences on motivation, and role in a multilingual education. International Journal of Multilingualism. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1411916

- Holliday, A., Hyde, M., & Kullman, J. (2004). Intercultural communication: An advanced resource book. London: Routledge.

- Ibrahim, N. (2016). Enacting identities: children’s narratives on person, place and experience in fixed and hybrid spaces. Education Inquiry, 7(1), 27595. doi: 10.3402/edui.v7.27595

- Joseph, J. (2004). Language and identity: National, ethnic, religious. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.2104/aral0728

- Kim, G. M. (2016). Practicing multilingual identities: Online interactions in a Korean dramas forum. International Multilingual Research Journal. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2016.1192849

- Kostoulas, A., & Mercer, S. (2016). Fifteen years of research on self & identity in system. System, 60, 128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2016.04.002

- Kramsch, C. (2006). Preview article: The multilingual subject. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 16(1), 97–110.

- Lam, W. S. E. (2000). L2 literacy and the design of the self: A case study of a teenager writing on the internet. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 457–482.

- Lamb, T. E. (2011). Fragile identities: Exploring learner identity, learner autonomy and motivation through young learners’ voices. The Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 68–85. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1016751471?accountid=150994

- Lankiewicz, H., Szczepaniak-Kozak, A., & Wasikiewicz-Firlej, E. (2014). Language learning and identity: Positioning oneself as a language learner and user in the multilingual milieu. Oceanide, 6, 11–27.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leary, M. R., & Tangney, J. P. (2003). The self as an organizing construct in the behavioural and social sciences. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 3–14). London: Guilford Press.

- Lestinen, L., Petrucijová, J., & Spinthourakis, J. (2004). Identity in multicultural and multilingual contexts. London: CiCe Thematic Network Project.

- Levine, R. K. (2013). Children’s identities as users of languages: A case study of nine Key Stage 2 pupils with a range of home language profiles (Doctoral dissertation). University of Cambridge.

- Marcia, J. E. (2007). Theory and measure: The identity status interview. In M. Watzlawik & A. Born (Eds.), Capturing identity: Quantitative and qualitative methods (pp. 1–15). Lanham: University Press of America.

- Martin, B. (2012). Coloured language: Identity perception of children in bilingual programmes. Language Awareness, 21(1–2), 33–56. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2011.639888

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2015). Multilingual awareness and heritage language education: Children’s multimodal representations of their multilingualism. Language Awareness, 24(3), 197–215. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2015.1072208

- Nasir, N. S., & Cooks, J. (2009). Becoming a hurdler: How learning settings afford identities. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 40(1), 41–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1492.2009.01027.x.41

- Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412–446. doi: 10.1017/S0261444811000309

- Norton Peirce, B. (1995). Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29(1), 9–31.

- Omoniyi, T. (2006). Hierarchy of identities. In T. Onomiyi & G. White (Eds.), Sociolinguistics of identity (pp. 11–33). London: Continuum.

- Oyserman, D., & James, L. (2011). Possible identities. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 117–145). New York: Springer.

- Park, H. (2015). Learning identity: A sociocultural perspective. Adult Education Research Conference. Retrieved from http://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2015/papers/41

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2003). On assimilating identities to the self: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization and integrity within cultures. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 253–272). London: Guilford Press.

- Schachter, E. P., & Rich, Y. (2011). Identity education: A conceptual framework for educational researchers and practitioners. Educational Psychologist, 46(4), 222–238. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2011.614509

- Schreiber, B. R. (2015). “I am what I am”: Multilingual identity and digital translanguaging. Language Learning and Technology, 19(3), 69–87. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84947259110&partnerID=tZOtx3y1

- Schwartz, S. J. (2001). The evolution of Eriksonian and neo-Eriksonian identity theory and research: A review and integration. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 1(1), 7–58. doi: 10.1207/s1532706xschwartz

- Schweiter, J. (2013). The FL imagined learning community: Developing identity and increasing FL investment. In D. J. Rivers & S. A. Houghton (Eds.), Social identities and multiple selves in foreign language education (pp. 139–156). London: Bloomsbury.

- Scott, V. M., Dessein, E., Ledford, J., & Joseph-Gabriel, A. (2013). Language awareness in the French classroom. The French Review, 86(6), 1160–1171.

- Skerrett, A. (2013). Building multiliterate and multilingual writing practices and identities. English Education, 45(4), 322–360.

- Sousa, D. A. (2017). How the brain learns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Taylor, F. (2013). Self and identity in adolescent foreign language learning. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Taylor, F., Busse, V., Gagova, L., Marsden, E., & Roosken, B. (2013). Identity in foreign language learning and teaching: Why listening to our students’ and teachers’ voices really matters. ISBN 978-0-86355-709-5.

- Toohey, K., & Norton, B. (2010). Language learner identities and sociocultural worlds. In R. B. Kaplan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of applied linguistics (2nd ed.). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195384253.013.0012

- Vågan, A. (2011). Towards a sociocultural perspective on identity formation in education. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 18(1), 43–57. doi: 10.1080/10749031003605839

- Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., & Johnson, K. A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 4(1), 21–44. doi: 10.1207/s15327701jlie0401

- Vignoles, V. L., Schwartz, S. J., & Luyckx, K. (2011). Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 1–27). New York: Springer.

- Welply, O. (2015). Re-imagining otherness: An exploration of the global imaginaries of children from immigrant backgrounds in primary schools in France and England. European Educational Research Journal, 14(5), 430–453.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Young, M., & Muller, J. (2013). On the powers of powerful knowledge. Review of Education, 1(3), 229–250. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3017

- Zembylas, M. (2003). Emotions and teacher identity: A poststructural perspective. Teachers and Teaching, 9(3), 213–238. doi: 10.1080/13540600309378