Abstract

Advertisers increasingly use personal information in social media advertisements as a strategy to promote positive brand attitudes. Personalized ads can be perceived as both positive and negative. This two-sided effect of personalization refers to the personalization paradox. An online experiment (N = 209), in which the level of personalization was manipulated in a Facebook setting, aimed to provide a potential explanation for this paradox. The findings showed that a highly personalized ad resulted in stronger perceived personalization than a less personalized ad. Furthermore, the stronger the perceived personalization, the stronger the relevance. The relevance of the ad positively influenced brand attitude and fully mediated the relationship between personalization and attitude. However, in line with the assumptions of the information boundary theory, the more the ad was perceived as intrusive, the weaker the relevance–attitude relationship, thereby showing a boundary condition for the effectiveness of personalized information when targeting consumers on Facebook.

In recent years, advertisers have begun to regard the use of personal information as one of the most important ways to reach a targeted audience (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). In the online industry, in particular, personalization of ads has become more common because personalization increases an ad’s effectiveness (Aguirre et al. Citation2015) and less money is spent on advertising (Gironda and Korgaonkar Citation2018). In addition, advertisers are able to experiment with relatively low costs for advertising (Jung Citation2017). The development of social media platforms has further accelerated the use of personalized information in targeting efforts (Jung Citation2017). Moreover, because social media users often provide (in)direct information about demographic, geographic, psychological, and sociographic attributes, and all users’ online actions are tracked, many wide-ranging opportunities for targeting efforts arise. Companies that take advantage of such readily available information and sophisticated social media technologies and software can create personalized and relevant advertising content that presumably targets the best-fit audiences at the right time (Tam and Ho Citation2006).

The advantages of ad personalization have been acknowledged by online retailers and consumers (Lee and Rha Citation2016; Tran Citation2017). Consumers respond favorably to displayed personalized ads and to the advertising brands because such ads address them personally and provide relevant information. Indeed, perceived personalization and relevance have been identified as the most important benefits of ad personalization; the stronger the perceived personalization and relevance, the more effectiveness the ad will be in positively changing attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward the advertised brand (e.g., Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019; Jung Citation2017; Lee and Rha Citation2016; Lustria et al. Citation2016; Smink et al. Citation2020; Tran Citation2017). However, personalization has also been associated with costs (Aguirre et al. Citation2015; Dehling, Zhang, and Sunyaev Citation2019; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019), including potential privacy or space violations and concerns (Gironda and Korgaonkar Citation2018; Lee and Rha Citation2016), feelings of being intimidated (Dehling, Zhang, and Sunyaev Citation2019), and vulnerability (Aguirre et al. Citation2015). The present study proposes that these costs trigger a general feeling of intrusion. The stronger the personalized ad triggers feelings of intrusiveness, the less effectiveness the ad will be in positively changing attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward the advertised brand (e.g., Lancelot, Cases, and Russell Citation2019; Morimoto and Chang Citation2006; Morimoto and Macias Citation2009; Smink et al. Citation2020).

This conflicted response toward ad personalization—where consumers sometimes positively but sometimes negatively respond to ad personalization—is referred to as the personalization paradox (Aguirre et al. Citation2015). That is, highly personalized ads typically increase the perceived benefits of the ad, potentially resulting in a more positive evaluation of the advertised product or brand. Paradoxically, highly personalized ads also have certain costs, including intrusion, which result in a more negative evaluation of the advertised product or brand.

The privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) provides an explanation for how consumers evaluate costs and benefits of ad personalization (Bol et al. Citation2018). More specifically, this theory depicts the process of how consumers evaluate the potential benefits and costs of personal information disclosure. The privacy calculus theory assumes that consumers are rational decision makers who are willing to disclose personal information online when the perceived benefits of disclosing such information outweigh the perceived costs. The outcome of such calculus is considered to be the cumulative effect of costs and benefits. The overall value of information disclosure is directly related to behavioral responses, such as the extent to which consumers accept that their personal information will be used or the likelihood that consumers will avoid an ad (Tran Citation2017; Xu Xin, Carroll, and Rosson Citation2011). Hence, while ad personalization includes both positive and negative sides referred to as the personalization paradox, the privacy calculus focuses on how consumers evaluate these costs and benefits resulting in specific disclosure actions (i.e., “calculus”).

Although the privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) specifically focuses on the negative effects of information disclosure rather than ad personalization, it is also relevant for the latter (Bol et al. Citation2018). Research shows that one’s willingness to disclose information and ad personalization are intertwined and both strongly influence attitudes toward the advertised brand and product as well (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Tran Citation2017; Xu Xin, Carroll, and Rosson Citation2011). Hence, in line with the privacy calculus principle, consumers who weigh specific costs and benefits of information disclosure will weigh costs and benefits of ad personalization in a similar way. When the perceived benefits of ad personalization outweigh the perceived costs, consumers will be more likely to develop positive attitudes toward the ad and brand; conversely, when the trade-off between the perceived costs and benefits is negative, ad personalization will result in weaker or negative attitudes toward the ad and brand.

The privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) provides an important framework for understanding consumers’ evaluations of costs and benefits of ad personalization on attitudes toward the advertised brand in general. However, the theory provides less insight into the process of the relative values consumers place on these costs and benefits. For example, although the relevance of an ad can be increased when using personalization, privacy calculus theory offers no explanation to what extent this benefit will be important in relation to the potential costs the consumer experiences simultaneously. The present study uses assumptions from the information boundary theory (IFT; Sutanto et al. Citation2013) to further understand this interdependent process between the evaluation of the relative costs and benefits of ad personalization. In particular, the present study assumes that feelings of intrusiveness—triggered by the costs of ad personalization—may signal to consumers that their personal boundaries have been crossed. IFT argues that crossing personal boundaries results in a loss of control that needs to be regained by decreasing the importance of the benefits relative to the costs of ad personalization. Hence, while perceived intrusiveness might be triggered by the exposure to certain costs of ad personalization, according to IFT it might also activate a consumer’s motivational process to reevaluate the benefits in relation to these costs.

The present study aims to examine the condition under which the benefits of ad personalization (i.e., perceived personalization and relevance) are important to explain the effectiveness of ad personalization (as measured by the consumer’s attitude toward the brand) and how perceived intrusiveness can weaken the positive effects of these benefits. More specifically, this study investigates the mediating role of relevance in the personalization–brand attitude relationship and examines how intrusiveness moderates the relationship between relevance and brand attitude in a social media context (i.e., Facebook). By doing so, the present research makes a substantive contribution to the existing literature on marketing and advertising in four ways.

First, in line with rational choice models, such as the privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977), most research in ad personalization and social media has focused on independent relationships between perceived costs and benefits of ad personalization on attitudes related to the advertising medium (Chen et al. Citation2019; Jung Citation2017; Shanahan, Tran, and Taylor Citation2019; Tran Citation2017; Tran et al. Citation2020; see also the literature review of Bol et al. Citation2018). Indeed, these studies show that when consumers perceive more costs (resulting in stronger feelings of intrusiveness) than benefits (increased relevance) of ad personalization, they are more likely to develop less favorable attitudes toward the ad and the brand; conversely, when consumers perceive more benefits than costs of ad personalization. they develop more favorable attitudes. In the present study, we argue that when consumers are exposed to a personalized ad, feelings of intrusiveness will simultaneously result in a reevaluation of the benefits, because intrusiveness signals that a personal boundary has been crossed and control needs to be regained, as suggested by IFT (Sutanto et al. Citation2013). Understanding this interdependent rather than independent relationship between intrusiveness and benefits such as relevance seems therefore essential for understanding the conditions under which ad personalization can backfire. Hence, rather than focusing on the main and mediating roles of intrusiveness and relevance on attitudes toward the advertising medium (Chen et al. Citation2019; Jung Citation2017; Shanahan, Tran, and Taylor Citation2019; Tran Citation2017; Tran et al. Citation2020), the present study investigates the conditions under which the positive effect of relevance on brand attitudes can be mitigated by consumers’ perceptions of intrusiveness, hereby providing a potential explanation for the personalization paradox.

Second, most studies that have concentrated on explaining the personalization paradox have often focused not on the broad motivational process of intrusiveness but on specific costs of ad personalization that can potentially lead to feelings of intrusiveness, such as privacy violations or concerns (Lee and Rha Citation2016) and ad skepticism (Tran Citation2017). By combining relevance—a key benefit of ad personalization (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015; Lustria et al. Citation2016)—with intrusiveness as a process rather than a specific cost, the present study contributes to a better understanding of how consumers make the mental trade-off proposed by privacy calculus theory.

Third, most research has focused on actual personalization, perceived personalization, or perceived relevance in operationalizations of research, while it has been theorized that these three concepts are distinct but related to one another (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015). It is important to further validate whether and how these concepts can be distinguished from one another to understand to what extent it will be useful to include them as separate entities in research. By manipulating actual personalization and measuring perceived personalization and relevance, the present study sheds some light on the unique contribution of and relationships among these three concepts.

Finally, the positive and negative effects of ad personalization have been studied in various online contexts, such as mobile advertising (Feng, Fu, and Qin Citation2016), direct e-mailing (White et al. Citation2008), and advertising personalization on websites (Van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013). However, less is known about how the benefits of perceived personalization and relevance of ad personalization and how feelings of intrusiveness affect the influence of these benefits on attitudes toward the brand in a social media context (Tran et al. Citation2020). The social media context is worth investigating because, compared to other (online) contexts, social media users tend to develop a much stronger sense of psychological ownership (Kirk, Peck, and Swain Citation2018). Feelings of intrusiveness are expected to be more in the foreground in such contexts. The motivational process triggered by feelings of intrusiveness might be even stronger in a Facebook social media context, because research shows that Facebook users feel more strongly engaged with this platform than with any other social media platform (Voorveld et al. Citation2018). For example, Facebook users are strongly engaged with this platform because it provides them with more opportunities to express their identity, to stay informed, and to engage in social interactions than any alternative social media platform (e.g., Twitter, Instagram, YouTube; Voorveld et al. Citation2018). That Facebook is currently the biggest social media platform (Ortiz-Ospina Citation2019) and its users have been increasingly exposed to ad personalizations (Tran et al. Citation2020) make Facebook a more relevant research context in which to investigate the boundary condition of intrusiveness on the benefits of ad personalization on attitudes toward the advertised medium compared to other online and social media contexts.

Literature Review

In recent years, interest in personalization in online advertising has grown considerably (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). Personal data—such as websites visited, articles read, videos watched, and purchases made—are used to create a personalized ad (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Dehling, Zhang, and Sunyaev Citation2019). In the online industry, personalization of ads has become common because it may increase ad effectiveness (Aguirre et al. Citation2015). The effectiveness of personalization has been measured in different ways, including click-through rates, attitudes toward the ad or brand, purchase intentions, and actual purchase behaviors (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). The present study focuses on attitude toward the brand as a key outcome measure for ad effectiveness.

Attitude toward the brand has been regarded as an important variable in marketing, consumer behavior, and advertising research, as it is deemed to be a strong predictor for purchase intentions and behaviors (e.g., Daems, De Pelsmacker, and Moons Citation2019; Mukherjee and Banerjee Citation2019; Rhee and Jung Citation2019; Zhu et al. Citation2019). It therefore comes as no surprise that companies are interested in understanding how to develop a positive brand attitude in consumers and utilize online ad strategies to let consumers get in contact with brands and form positive attitudes toward them (Lee et al. Citation2017). In line with Spears and Singh (Citation2004), and in the context of the present study, attitude toward the brand is defined as a relatively enduring, unidimensional summary evaluation of the brand that most likely is able to energize behavior.

The Benefits of Ad Personalization: Perceived Personalization and Relevance

Brands use ad personalization strategies to more effectively advertise the brand to a consumer, thereby aiming to strengthen the consumer’s attitude, purchase intentions, and behaviors (Maslowska, Smit, and Van den Putte Citation2016). Social media sites such as Facebook seem to be well equipped for ad personalization (Montgomery and Smith Citation2009). Ad personalization can be defined as delivering ads that contain individualized information based on the unique preferences of the receiver (Li Citation2016). Ad personalization has become increasingly popular to use due to organizations accumulating increasing amounts of information (i.e., data) on their potential consumers in social media settings (Li Citation2016). However, few studies have examined the underlying process responsible for the effectiveness of ad personalization (Maslowska, Smit, and Van den Putte Citation2016), and the studies that have examined this process often lack a clear theoretical focus (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017).

Personalization can be distinguished in two types: actual versus perceived personalization. Actual personalization refers to the extent to which the advertiser has used personal information from the consumer. Perceived personalization refers to the extent to which the consumer feels that an ad is personalized. As a consequence, an ad can be personalized by the advertiser without the recipient perceiving it as personalized, and vice versa (Li Citation2016). For example, addressing a consumer on a first-name basis is a form of ad personalization, but the consumer might not perceive it as such when the content of the ad relates to a product in which the consumer has never shown an interest. In contrast to other studies that focus only on actual or ad personalization, when this study mentions ad personalization, it refers to the actual personalization; while when it refers to perceived personalization, we refer to subjective perceptions specifically.

Ad personalization has similarities with customization. Ad personalization is when the firm decides, usually based on a consumer’s previous behaviors, what marketing content, services, or products are suitable to advertise to the individual. Customization, however, involves the consumer proactively specifying one or more elements of the marketing content (Arora et al. Citation2008). Thus, although both represent a one-to-one marketing approach involving the manipulation of a marketing mix, customization is mostly driven by the consumer, while ad personalization is largely initiated by the firm (Arora et al. Citation2008).

Ad personalization is often an effective strategy to positively influence attitudes toward the ad and brand (Gutierrez et al. Citation2019). The effectiveness of ad personalization is based on perceived benefits and costs (or risks) associated with it (Aguirre et al. Citation2015; Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Bleier and Eissenbeis 2015; Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Tran et al. Citation2020). Ad personalization is assumed to be an effective persuasion strategy when it increases the receiver’s perceived personalization (Li Citation2016). That is, when ad personalization generates a match between what is being displayed in the ad and the characteristics of the recipient of the ad (Petty, Wheeler, and Bizer Citation2000), the personalized ad will be recognized as such by the recipient and will result in a strong perceived personalization. When the recipient of the ad perceives an ad as personalized—that is, when the receiver perceives a match between the receiver’s self and what is being displayed in the ad (Anand and Shachar Citation2009)—the ad is able to increase perceived relevance (Kramer Citation2007). Relevance refers to the extent to which what is being displayed in the ad is related to the recipient’s personal needs and values (Jung Citation2017). Therefore, in this study, relevance always implies the consumer’s perspective or perceptions.

An increase in relevance can be regarded as one of the key benefits of ad personalization (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019). Indeed, research shows that relevance increases the persuasive power of ads (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015; Smink et al. Citation2020). For example, research shows that as ads are perceived as more relevant, it becomes easier for consumers to process the ad, and the more appealing the message will be to them (Banerjee and Dholakia Citation2008). Also, relevance has also been strongly related to message involvement: the more relevant a message is perceived, the stronger the consumer’s involvement in the ad and the product, resulting in stronger attitudes (Albert, Goes, and Gupta Citation2004; Lee, Kim, and Sundar Citation2015; Lee and Rha Citation2016). Finally, relevant messages are generally perceived as more likable and pleasant (Kim and Han Citation2014), also resulting in more positive ad and brand evaluations. These results are in line with identity theories (e.g., for an overview of identity theories in consumer research, see Udall et al. Citation2020). These theories suggest that messages that are in line with consumers’ needs, values, and behaviors (i.e., consumers’ identities) will be experienced as more positive by those consumers. Hence, an increase in perceived personalization and relevance results in more positive attitudes toward the brand.

Theories in rational decision making, such as privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977), assume that consumers’ attitudes are the sum of the potential costs and benefits of personalized ads. When the benefits of ad personalization outweigh the costs, consumers will likely develop a positive attitude toward the ad and brand. However, when the personalized ad has more perceived costs than benefits, consumers will likely develop a negative attitude toward the ad and brand. Hence, consumers normally evaluate ad personalization as positive because the benefit of increasing the perceived personalization and personal relevance outweighs the potential costs associated with ad personalization, such as feelings of space and attention invasion, thereby generating positive attitudes toward the ad and the brand. Indeed, the positive relationship between perceived personalization (e.g., Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019; Smink et al. Citation2020) and relevance (e.g., Campbell and Wright Citation2008; Hayes et al. Citation2020) on brand attitude has received empirical support, although few studies have focused on both perceived personalization and relevance together in a social media context. Indeed, the positive relationship between relevance and brand attitude has received empirical support (e.g., Campbell and Wright Citation2008; Hayes et al. Citation2020), although few studies have focused on this relationship in a social media advertising context (Tran et al. Citation2020).

Relevance is expected to mediate the relationship between perceived personalization and attitude toward the brand. That is, when a receiver is confronted with personalized information, this information activates a causal chain from activating perceptions of personalization, which increases the relevance of the ad, which will make it more likely that the receiver will form a positive attitude toward the advertised brand. De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker (Citation2015) provide support for the positive mediating role of relevance of the ad between personalization and brand attitude. In two experiments, they showed that ad relevance positively mediated the relationship between personalization and attitude toward the brand when personalizing ads on Facebook. In the present study, this mediating role has been coined as the personalization-relevance-attitude model. In line with this model and these theories, the present study tests the following hypotheses:

H1: The stronger participants perceive the personalization of an ad, the more likely they are to perceive the ad as relevant.

H2: The greater the relevance of an ad as perceive by the participants, the stronger their attitudes will be toward the advertised brand.

H3: Ad relevance mediates the relationship between ad personalization and attitude toward the advertised brand.

Feelings of Intrusiveness and the Reevaluation of Benefits and Costs of Personalization

Personalized information in advertising can lead to recipients perceiving threats to their freedom due to increased ad intrusiveness. Indeed, the costs of ad personalization, including privacy violations, intimidation, and worries about misuse of personal data, have been implied to trigger feelings of intrusiveness throughout the literature (Aguirre et al. Citation2015; Dehling, Zhang, and Sunyaev Citation2019; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019; Lancelot, Cases, and Russell Citation2019; Morimoto and Macias Citation2009; Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014; Truong and Simmons Citation2010). Thus, just as relevance can be perceived as an important benefit of ad personalization, intrusiveness can be regarded as the result of important costs associated with ad personalization. Understanding the negative effect of intrusiveness is key to a more fundamental understanding of the effectiveness of ad personalization, because scholars argue that perceived intrusiveness has potentially detrimental long-term effects on digital marketing strategies (Chatterjee Citation2008; Truong and Simmons Citation2010).

Intrusiveness is defined as a negative response in consumers when advertisements interfere with consumers’ ongoing task performance and cognitive processing (Cho and Cheon 2002; Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002; Truong and Simmons Citation2010). Two important inferences can be made based on this definition. First, in line with the definition, the present study implies that intrusiveness is subjective; hence, it always refers to consumer perceptions. Second, the definition of intrusiveness refers not to a cost related to ad personalization in an absolute sense but to a motivational process that can trigger how consumers reevaluate specific costs and benefits of ad personalization. That is, the level of intrusiveness perceived by consumers can be triggered by specific costs of ad personalization as identified throughout the literature, such as feelings of privacy violations (Lee and Rha Citation2016), intimidation (Dehling, Zhang, and Sunyaev Citation2019), and worries about misuse of personal data (Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014).

Ad personalization may result in feelings of intrusiveness in several ways. For example, receiving personalized ads can be perceived as intrusive because they may interrupt a specific goal of consumers, such as posting an update on their Facebook timelines (Smink et al. Citation2020). Ad personalization can also evoke feelings of intrusiveness because the personalized ad is perceived as too personal or invasive in relation to consumers’ privacy (e.g., by using very private personal data; Lee and Rha Citation2016; Van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013) or when consumers feel more concerned about how the advertising medium deals with their personal information (privacy concerns; Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014). Moreover, scholars argue that ad personalization may result in feelings of intrusiveness because consumers have no autonomous control over the advertising: The advertiser chooses when and how consumers will be exposed to personalized ads and which personal information is being exploited in the ads shown to consumers (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019). As intrusiveness can be triggered in many different ways, the present study focuses on the concept of intrusiveness in the broadest sense of its meaning, including but not limited to aspects of privacy invasion and privacy concerns.

Intrusiveness results in negative feelings, such as annoyance and irritation (Li et al. Citation2002). These negative feelings result in a reevaluation of attitudes toward the advertised medium (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Lancelot, Cases, and Russell Citation2019; Morimoto and Chang Citation2006; Morimoto and Macias Citation2009; Smink et al. Citation2020). For example, research shows that intrusiveness triggers negative emotional (disturbance, irritation) and behavioral (ad avoidance) responses (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019), which are all negatively associated with attitudes toward the ad and brand (Morimoto and Macias Citation2009).

Most of the research has focused on the relative contribution of specific costs of ad personalization, such as space and privacy invasion (resulting in feelings of intrusiveness), and/or benefits, such as relevance toward the effectiveness of ad personalization (e.g., Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015; Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019; Lancelot, Cases, and Russell Citation2019; Lee and Rha Citation2016; Maslowska Smit and van der Putte 2016; Smink et al. Citation2020). These studies therefore assess the effect of intrusiveness (or costs that result in feelings of intrusiveness) and benefits, such as relevance, of ad personalization on attitudes independent of each other, thereby ignoring the interrelated processes behind the evaluation of these benefits and costs (Karwatzki et al. Citation2017). In reality, though, perceptions of relevance and intrusiveness will be evoked simultaneously rather than independently when a consumer is exposed to ad personalization. In particular, intrusiveness can be regarded as a critical factor that causes consumers to reevaluate the potential benefits of ad personalization on attitudes related to the advertised medium (Gutierrez et al. Citation2019). Although privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) provides a useful framework to understand the relative contribution of perceived costs and benefits of ad personalization on attitudes toward the advertised medium (Bol et al. Citation2018), IFT (Stanto and Stam Citation2002; Sutanto et al. Citation2013) seems to be better equipped to investigate these interdependent processes (Karwatzki et al. Citation2017). The present study therefore uses IFT to understand the interdependent relationships of relevance and intrusiveness on consumer attitude toward the brand.

The literature on online advertising has focused on how costs of ad personalization, such as space and privacy invasion (resulting in feelings of intrusiveness), and/or benefits, such as relevance, influence the effectiveness of this marketing strategy (e.g., De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015; Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002; Lee and Rha Citation2016; Maslowska Smit and Van der Putte 2016). Most of this research has studied direct and mediating effects of such costs and benefits on ad and brand attitudes (e.g., Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019; Lancelot, Cases, and Russell Citation2019; Smink et al. Citation2020). By focusing on these processes, these studies (implicitly) focus on the privacy calculus principle (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) to understand such relationships. That is, these studies assess the effect of intrusiveness, which is regarded as the result of certain costs and benefits, such as relevance, of ad personalization on attitudes independent of each other, thereby ignoring the interrelated processes between these constructs (Karwatzki et al. Citation2017). The present study acknowledges that feelings of intrusiveness are the result of being exposed to various negative consequences or costs of ad personalization (e.g., privacy and space invasion). However, it additionally argues that these feelings activate another process—an interdependent one—where these costs are evaluated again in relation to the benefits of personalization, as proposed by IFT (Stanto and Stam Citation2002; Sutanto et al. Citation2013).

IFT acknowledges more complex processes are at play when understanding how feelings of intrusiveness can moderate the influence of relevance on brand attitude. This theory assumes that feelings of intrusiveness, although triggered by the perceived costs of ad personalization, can reshape consumers’ evaluations of costs and benefits of ad personalization. That is, IFT acknowledges that perceptions of relevance and feelings of intrusiveness will be evoked simultaneously. The privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) is useful to understand the relative contribution of certain costs and benefits of ad personalization on attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward the advertised medium (Bol et al. Citation2018). However, IFT (Stanto and Stam Citation2002; Sutanto et al. Citation2013) seems to be better equipped to investigate the interdependent processes that might occur between the importance of relevance as a benefit of ad personalization and the process that perceived intrusiveness may invoke (Karwatzki et al. Citation2017). Understanding the interdependent rather than independent process of perceived intrusiveness on the relationship between perceived relevance as a benefit and brand attitude seems to be essential to understand the conditions under which ad personalization can backfire as well.

IFT (Stanto and Stam Citation2002; Sutanto et al. Citation2013) claims that the relative weight of costs and benefits of a marketing strategy depends on the extent to which consumers feel their personal boundaries have been crossed. When being exposed to personalized ads, consumers are confronted with the fact that their personal information has been accessed and/or used by the advertised company outside of their control (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012; Jung Citation2017). Forced exposure to personalized ads can cross the personal space boundaries of consumers, resulting in feelings of intrusiveness (Kirk, Peck, and Swain Citation2018; Niu, Wang, and Liu Citation2021). The more consumers feel intruded by the exposure of personal information, the more likely they will be motivated to regain their loss of control in relation to this exposure by acting in the opposite way as intended by the source (Brehm Citation1966; see also Aguirre et al. Citation2015). Hence, consumers will put less weight on the perceived benefit of a personalized ad as presented by the ad’s relevance. The decreased emphasis on this benefit is assumed to restore consumers’ loss of control (cf. Baek and Morimoto Citation2012). Therefore, feelings of intrusiveness are triggered by potential costs of ad personalization; however, at the same time, they also seem to trigger a process of how these costs are evaluated in relation to the benefit of ad relevance.

Some empirical evidence suggests intrusiveness might function as a moderator between relevance and brand attitude. In line with IFT, Morimoto and Macias (Citation2009) found that the more consumers perceive an ad as intrusive, the stronger their psychological reactance, resulting in a more negative attitude toward the ad and advertised medium. Also, Van Doorn and Hoekstra (Citation2013) showed that the positive effect of personalized information in an ad on purchase intentions was weakened when the receiver perceived higher levels of intrusiveness, thereby contributing to how personalized information can backfire. However, these scholars focused on whether intrusiveness mitigates the different levels of personalization on purchase intentions. The present study further investigates when personalized information can be counterproductive by integrating intrusiveness in the personalization-relevance-attitude model as proposed and tested by De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker (Citation2015). That is, like this model, the present study specifically distinguishes the three concepts of actual personalization, perceived personalization, and perceived relevance. The current study further examines the conditions under which the positive effect of relevance works.

Feelings of loss of control are likely stronger in a Facebook context than in other social media contexts due to the psychological ownership that consumers experience on this social media platform (Kirk, Peck, and Swain Citation2018; Niu, Wang, and Liu Citation2021). Psychological ownership refers to feelings of a connection with both intangible and tangible objects and experiencing the object to be “your own” (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001). Social media platforms such as Facebook are examples of such intangible objects, as they are largely controlled by consumers themselves (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015). Facebook is perceived to provide stronger opportunities to express personal identity, to stay informed, and to engage in social interactions than other social media platforms (Voorveld et al. Citation2018), ultimately resulting in a stronger sense of psychological ownership. The stronger sense of ownership of this social media platform may lead to stronger feelings of boundary crossing when consumers are exposed to personal ads in this space, resulting in even stronger feelings of intrusiveness. The motivational response in relation to how important the benefit of perceived relevance will be evaluated in relation to the overall evaluation of the brand might consequently be stronger as well (Smink et al. Citation2020).

Few studies investigate the interdependent relationships between benefits, including both perceived personalization and relevance and brand attitude, and how feelings of intrusiveness affect these relationships. Validating these findings in a Facebook context is therefore pivotal for two reasons. First, due to the replication crisis in social and behavioral sciences (Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn Citation2011) in general, the validation purpose across different samples, experimental manipulations, and research contexts seems to be an important contribution in its own right. Second, the focus on the interdependent rather than dependent effects as proposed seems to be theoretically more relevant in a Facebook context than in any other social media context or offline context. Hence, more research and replications should be done in this context specifically.

Based on information boundary theory and the empirical evidence, the present study tests the following hypothesis:

H4: There is a weaker positive relationship between ad relevance and attitude toward a brand if the receiver of the ad perceives a higher degree of intrusiveness caused by the ad.

Method

Research Design

The relationships between personalization, relevance, intrusiveness, and attitude toward the brand were tested with a one-way, between-participant experimental design. The independent manipulation variable, personalization, included two levels: a high and a low personalized ad. After being exposed to the experimental manipulation, participants answered questions in relation to the (perceived) personalization, the mediator variable relevance, and the moderator variable intrusiveness. The dependent variable was the attitude toward the brand.

Sampling Strategy and Sample

The research was conducted in the Netherlands. Hence, a Dutch-speaking population was targeted, and only people who were fluent in Dutch were allowed to participate in the study. Furthermore, people who did not own a Facebook account were excluded from the study. To easily reach individuals with both preconditions, a Dutch survey invitation was sent out on Facebook using a convenient sampling strategy.

The final sample included 209 participants. An a priori sample size analysis (Soper Citation2020) revealed that for a small anticipated effect (f2 = 0.10), with a minimal desired statistical power of 0.80, using a probability level of 0.05, and including four predictors (personalization, relevance, intrusiveness, and the interaction term relevance × intrusiveness), a minimum sample of 124 participants was needed (see Cohen et al. Citation2003). Therefore, the sample size of 209 participants was sufficient for the aim of the present study.

The sample consisted of 60% women (38% men) with a mean age of 28 years (SD = 11.30). The majority of the participants were highly educated, with either a secondary vocational education (37%) or a university degree (39%). Most participants had a yearly income lower than €10,000 (U.S. $11,156) (48%). Hence, the sample overrepresented females, people who were relatively young and well educated, and people who belonged in lower income groups. This makes it a convenience sample only.

Experimental Manipulation

A scenario-based experiment was used in which participants were asked to take the perspective of one specific person. The scenario portrayed someone who liked to travel and make trips, especially to Asia, in the following way:

Imagine yourself as being someone who loves to travel, especially to Asia. You have already been to Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Bali, an island part of Indonesia, is the next destination you want to visit. Recently you were on Facebook and came across the Facebook page “BaliTrips.” BaliTrips posts pictures and travel tips regarding Bali, named: Bali.nl. Since you are interested in travelling to Bali you decide to like and follow the page Bali.nl. The following day you receive the following advertisement on your Facebook timeline from the company Travels-for-U. During the week you regularly see the same advertisement on your Facebook timeline.

You did not have any previous encounters with the company Travels-for-U and therefore did not know about the existence of this company. Furthermore, the Facebook page “BaliTrips” and the company Travels-for-U are in no shape or form connected to each other.

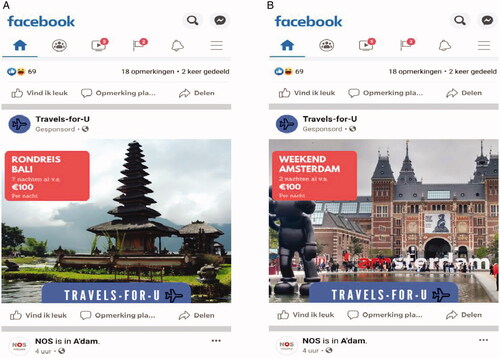

Two different ads were integrated into the specific scenario to manipulate the personalization of an ad: a trip to Bali (high personalization) or a trip to Amsterdam (low personalization). A low-personalized ad was chosen instead of a nonpersonalized ad because the present research aimed to investigate the difference between the extent of personalization instead of the difference between personalized and generic ads.

The destination Bali was chosen to represent the high-personalized group, as the person in the scenario was planning to go to Bali for a trip and showed interest in this by liking and following the Facebook page “BaliTrips.” The Amsterdam ad was shown to the low-personalized group, as a trip to Amsterdam was still likely to be regarded as traveling for Dutch people (i.e., which the person in the scenario liked to do), but it did not align with the specific wishes the person in the scenario expressed, thereby reducing the likelihood that it was perceived as highly personalized.

A fictitious brand was used to avoid any confounds of previous attitudes toward an actual brand. Furthermore, both of the ads used in the experiment looked similar to ensure treatment equivalence (e.g., same layout of the ad, same price per night). The differences were the background picture and the text adjusted to reflect either a weekend holiday to Amsterdam or a seven-day trip to Bali (see ).

Procedure and Measures

The survey started with asking whether participants had a Facebook account and how frequently they used it. If participants indicated that they did not own a Facebook account, they were thanked and excluded from further participation (n = 18). The participants who did have a Facebook account were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions: They either received the high-personalized ad for a fictitious brand regarding a trip to Bali (n = 103) or they received the low-personalized ad regarding a weekend holiday to Amsterdam (n = 106). Next, they received questions regarding personalization, relevance, and intrusiveness. The order in which the participants received the questions about relevance and intrusiveness was randomized. Finally, attitude toward the brand was measured. The items regarding personalization, relevance, and intrusiveness were measured prior the attitude items, because this gave participants the opportunity to form an attitude toward a brand with which they were not familiar. Because the data for this research were gathered in the Netherlands, all of the items were translated through the use of back translation.

Attitude toward the Advertised Brand

In line with Spears and Singh (Citation2004), participants were asked to describe their feelings toward the advertised brand. The scale included five semantic bipolar items, such as Unappealing/Appealing. These items were measured on a 7-point semantic bipolar scale. Mean scores revealed that participants had a slightly favorable attitude toward the advertised brand (M = 4.16, SD = 1.02, Cronbach’s α = .89).

Personalization

Personalization measured the participants’ perceptions of the personalization. In line with Li (Citation2016), personalization was measured with two items: (1) “The ad seemed to be designed specifically for me” and (2) “The advertisement targeted me as an unique individual.” The items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). The mean scores across these two items showed that, in general, participants neither agreed nor disagreed that the ad was personalized (M = 3.63, SD = 1.53, Cronbach’s α = .74).

Relevance

Ten items were included to measure perceived relevance, adopted from Laczniak and Muehling (Citation1993). Items such as “When I saw the advertisement of Travels-for-U on Facebook, I felt that it might be meaningful to me” were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Mean scores showed that, on average, participants felt relatively neutral to slightly positive toward the relevance of the ad (M = 4.01, SD = 1.32, Cronbach’s α = .95).

Intrusiveness

The items used for intrusiveness were based on the instrument used in Edwards, Li, and Lee (Citation2002). The scale included 10 items, such as “I think this offer is disturbing,” on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Mean scores showed that, on average, participants did not agree nor disagree that the ad was intrusive (M = 3.74, SD = 1.26, Cronbach’s α = .92).

Validity and Reliability of Measures

A factor analysis was used to test convergent and discriminant validity and reliability. First, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was executed and showed that it was appropriate to combine the personalization (i.e., continuous variable) items, the relevance items, the intrusiveness items, and the attitude items into a factor analysis, as values all exceeded > 0.50 (Field Citation2009). Also, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant for all variables, showing that they were uncorrelated. No correlation coefficients below the threshold of 0.30 or above the threshold of 0.90 were found, indicating there were no multicollinearity issues (Field Citation2009). Next, a factor analysis was used to test the reliability and validity of the constructs (see Appendix 1). Based on the results of the factor analysis, the items of the separate constructs were computed together to form their overarching construct and were averaged.

Manipulation Check

A manipulation check with an independent t test was conducted to examine whether participants in the high-personalization condition perceived the ad as more personalized than the participants in the low-personalization condition. Before carrying out the independent samples t test, the assumptions were checked. Because Levene’s test was significant, the interpretation of the results of the t test looked at the equal variances not assumed. Participants in the high-personalized condition perceived the ad to be significantly more personalized (M = 4.19, SD = 1.52) than the participants in the low-personalized condition (M = 3.10, SD = 1.33), t (204.88) = −5.50, p = .000, Cohen’s d = 0.76. The mean of the low-personalization experimental condition showed that participants still perceived the ad as somewhat personalized, probably because both experimental conditions were in a travel context. Therefore, the present experiment successfully manipulated a high- versus low-personalization condition rather than a high- versus no-personalization condition.

Analysis

IBM SPSS Version 25 was used to perform the statistical tests that were needed to answer the hypotheses. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis via the PROCESS macro of Hayes’s (Citation2018) Model 4 (bias-corrected, 5,000 bootstrap samples) was used to test hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, and the macro of Hayes’s Model 1 was used to test hypothesis 4.

A separate mediation and moderation procedure was applied, because the present article theorized that there are only conditional direct effects between the moderator (intrusiveness) on the mediator (relevance) and brand attitude relationship, rather than conditional indirect effects (i.e., effects of personalization on brand attitude via relevance will depend on levels of intrusiveness). To correct for using two separate tests, a Bonferroni correction was applied, resulting in using a significance level of p < .025 (.05/2). B values, R2 and R2-change values, F values, the indirect unstandardized B values, and their confidence intervals (CIs) were reported to provide a full picture of effect sizes in relation to the moderating/mediating analyses (Preacher and Kelley Citation2011).

Of Hayes’s Model 4 analysis, the main effect of personalization on the mediator relevance was reported (hypothesis 1). The results of hypothesis 1 were further validated by conducting a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the experimental condition (high and low personalization) as the independent variable and relevance as the dependent variable. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation of the experimental groups), F values, and the Cohen’s d were reported to provide an indication of the direction and the effect size of the causal relationship.

Next, the direct effect of the mediator on the dependent variable brand attitude was reported (hypothesis 2). Support for hypotheses 1 and 2 were preconditions to further investigate the mediating effect (Baron and Kenny Citation1986). To test the mediating effect (hypothesis 3), the effect of the independent variable (perceived personalization) on the dependent variable (brand attitude) was tested, first without controlling for the mediating variable (relevance) and then including the mediator. The indirect effect of the mediating variable on the dependent variable was reported, including the unstandardized regression coefficient, the standard error, and the 95% CI. If the CI did not include zero the indirect effect was regarded as significant (i.e., mediation occurred; Field Citation2009).

Finally, Hayes’s Model 1 moderation analysis (95% CI from 5,000 bootstrapped samples) was used to test whether the relationship between relevance and attitude toward the brand was moderated by the level of intrusiveness (hypothesis 4). The details of the moderator effect were further examined by looking at the conditional effects of the focal predictor at different values of the moderator (see Results section).

In all analyses, results were controlled for the influence of sociodemographics to see whether they would have an effect on the tested relationships, as the convenience sample was not representative of the Facebook population. In particular, the confounding effects of age, income, and frequency of using Facebook were included based on past literature (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). Age could be assumed to influence the hypothesized relationships, because in general a relatively younger population is on Facebook (Statista Citation2019), and younger people are less likely to oppose personalization (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). Income was taken into account for practical reasons, as our scenario specifically focused on traveling, which is a relatively costly hobby. As people with lower incomes may regard traveling as expensive, this could cause these people to generally be more negative toward such ads. The frequency of Facebook use was included as an indicator for online experience, which has shown to impact perceptions in relation to personalization. That is, the more that consumers use their Facebook accounts, the more likely they are to become tolerant or numb to personalized advertising and the less likely that personalization will be perceived at all. Including these confounds did not change the conclusions of our results, so the present article reports only the main results without correcting for these variables.

Results

Relationships between Personalization, Relevance, and Brand Attitude

The total model, including personalization, relevance, and intrusiveness, explained 17% of the variance in attitude toward the advertised brand (F (2, 206) = 21.26, p = .000; see ). Personalization significantly explained brand attitude when the mediator was not included (B = 0.55, p = .001; R2 = .40, F (1, 207) = 139.60, p = .000), thereby supporting hypothesis 1. These results were further validated with the one-way ANOVA between actual personalization (i.e., categorical variable: high versus low personalization) and relevance. Results showed that the low-personalization group perceived the ad as less relevant (M = 3.55, SD = 1.32) than the high- personalization group (M = 4.48, SD = 1.15), F (1, 208) = 29.37, p = .000, Cohen’s d = 0.76. Therefore, both the regression and the ANOVA supported hypothesis 1.

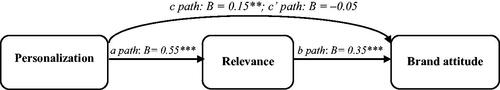

Figure 2. Mediator effect of ad relevance on the personalization-brand attitude relationship. F (2, 206) = 21.26; R2 =.17; ab path: B = .19; 95% CI =.12,.27; ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Results also indicated that relevance was a significant explanatory factor for brand attitude even when personalization was included in the regression model. The regression coefficient indicated that the more participants perceived the ad as relevant, the more positive their attitudes toward the advertised brand (B = 0.35, p = .000), thereby providing support for hypothesis 2.

Relevance mediated the relationship between personalization and attitude toward the advertised brand (). In addition to the significant direct effects of personalization on the mediator (hypothesis 1), and relevance on the dependent variable (hypothesis 2), personalization significantly explained brand attitude when the mediator was not included (B = 0.15, p = .002). When relevance (i.e., mediator) was included in the model, personalization did not significantly explain attitudes anymore (B = −0.05, p = .390), suggesting a full mediation. Indeed, Hayes’s (Citation2018) mediation procedure showed that the indirect effect of personalization through relevance was significant, as the 95% CIs did not include zero (B = 0.19, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.12, 0.27]), thereby providing support for hypothesis 3.

Intrusiveness as a Moderator on the Relationship between Relevance and Attitude toward the Brand

The overall model explained 32% of variance in attitudes toward the brand (F (3, 205) = 32.23, p = .000; see ). In line with hypothesis 2, a main effect for ad relevance on brand attitude was found: the stronger the perceived relevance, the more positive one’s attitude toward the advertised brand (B = 0.54, p = .000). A negative nonsignificant effect for ad intrusiveness was observed (B = −0.01, p = .926). The moderator relevance × intrusiveness contributed significantly to the explanation of the model as well (B = −0.07, p = .022).

Table 1. Moderation effect of ad intrusiveness on the relationship between ad relevance–brand attitude.

The conditional effects of the focal predictor at low, medium, and high values of the moderator showed the direction of the moderating effect. For those with low ad intrusiveness (1 SD below the mean), ad relevance had a stronger influence on the attitude toward the brand (B = 0.36, p = .000) than for those with high ad intrusiveness (1 SD above the mean) (B = 0.17, p = .008). Additional analyses provided further support for this direction: At a score of approximately 5 on a 7-point Likert scale on intrusiveness, the relevance was positively but weakly related to brand attitude (B = 0.18, p = .000); whereas at the lowest ad intrusiveness (a score of 1), the relevance was related strongly and positively to brand attitude (B = 0.46, p = .000). Therefore, the findings also supported hypothesis 4: the more participants perceived an ad as intrusive, the less influence the perceived relevance had on the attitude toward the brand.

Discussion

Advertisers increasingly use personal information in social media ads as a strategy to promote positive brand attitudes (Maslowska, Smit, and Van den Putte Citation2016; Montgomery and Smith Citation2009). However, ad personalization can also backfire. The aim of the present study was to examine when ad personalization would be effective in promoting positive brand attitudes but also to consider the conditions under which this effectiveness is likely to be attenuated. In particular, this study examined how ad personalization can be counterproductive by integrating intrusiveness into the personalization-relevance-attitude model (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015).

Results of this study showed that perceived personalization resulted in a stronger perceived relevance of the ad and that relevance was strongly positively related to brand attitudes. Indeed, ad personalization often has been assumed to be an effective strategy to positively influence attitudes toward the ad and brand when it is perceived as personalized and relevant as well (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015; Gutierrez et al. Citation2019; Li Citation2016). Consequently, perceived personalization and relevance were argued to be two important benefits of ad personalization. In line with the urge of replicating rather than extending previous research only in social and behavioral sciences (Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn Citation2011), our results further validated both findings: perceived personalization is strongly related to relevance, and relevance is strongly related to brand attitudes. Thus, our results support the assumption that both are key benefits to increase the persuasive power of personalized ads (Campbell and Wright Citation2008; Hayes et al. Citation2020; De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015; Smink et al. Citation2020).

Furthermore, the results showed that ad personalization elicits positive attitudes toward the brand via perceived personalization and relevance, thereby supporting the causal chain of how ad personalization explains brand attitudes (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015). Apparently, ad personalization affects consumers’ perceived personalization. The perceived personalization affects how consumers perceive the benefits of ads, as translated in relevance, and the stronger consumers perceive these benefits, the more positive their attitudes toward the brand. Few studies have examined the underlying process responsible for the effectiveness of personalization in advertising (Maslowska, Smit, and Van den Putte Citation2016), and even fewer included actual and perceived personalization next to relevance. Validating and extending the personalization-relevance-attitude model of De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker (Citation2015) in a Facebook context further increases the understanding of the process how the benefits of ad personalization actually cause positive changes in attitudes toward the brand.

The mediating role of relevance in the perceived personalization-attitude relationship suggests that ad personalization creates a match between how consumers see themselves, including a match between their needs, values, and behaviors (Anand and Shachar Citation2009; Jung Citation2017), and what is being displayed in the ad. This match is largely interpreted as something positive by consumers, as long as consumers perceive it to be congruent with their self-schemas (Ahn, Phua, and Shan Citation2017). Indeed, identity theories (see review of Udall et al. Citation2020) suggest that consumers are more likely to show positive attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward an attitude object (i.e., brand) when their identities are congruent with how others see them. Our results suggest that ad personalization might exactly fulfill this purpose by implying that the brand indeed knows who its consumers are.

Most of the studies that have focused on ad personalization in their theoretical framework often did not include relevance, while those that have focused on relevance did not include personalization (Jung Citation2017; Maslowska, Smit, and Van den Putte Citation2016; Sutanto et al. Citation2013; Van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013; Walrave et al. Citation2016). Moreover, most studies either measured actual personalization (Sutanto et al. Citation2013; Van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013; Walrave et al. Citation2016) or measured only perceived personalization (i.e., not including actual personalization; Chen et al. Citation2019; Shanahan, Tran, and Taylor Citation2019). There can be a mismatch between actual and perceived personalization, as the receiver might not always perceive the way in which the advertiser personalizes ads as personal (Li Citation2016). As our findings indicate that these three concepts are distinct entities, future research should regard these three concepts as such by making more explicit distinctions among the three concepts in conceptualizations and operationalizations.

Finally, the results showed that intrusiveness mitigated the effect of relevance on brand attitude. That is, when consumers perceived personalized information as intrusive, they were less likely to say that relevance positively influenced their brand attitude. While privacy calculus theory (Laufer and Wolfe Citation1977) suggests that consumers rationally weigh certain costs and benefits of ad personalization, these results provide an explanation for how consumers weigh them. That is, intrusiveness seems to work as a boundary condition for consumers in which they reevaluate the costs and benefits of the personalized ad, as suggested by IFT (Stanto and Stam Citation2002; Sutanto et al. Citation2013): the stronger a consumer feels intruded on by the personalized ad, the stronger the perception of personal boundary crossing. In line with the assumptions of IFT, under these conditions consumers seem to reduce the importance of the benefit of an increased personal relevance in their cost-benefit trade-off, resulting in weaker brand attitudes. Although past studies have often focused on the independent relationships of which costs and benefits are important in relation to the effectiveness of ad personalization (e.g., Chen et al. Citation2019; Jung Citation2017; Shanahan, Tran, and Taylor Citation2019; Tran Citation2017; Tran et al. Citation2020; literature review of Bol et al. Citation2018), our results indicate that feelings of intrusiveness not only are the result of perceived costs of ad personalization but also trigger consumers’ evaluation process of these perceived costs in relation to the perceived benefits. Therefore, theories dealing more explicitly with interdependent relationships within cost-benefit trade-offs, such as IFT, might be a useful addition to the popular privacy calculus theory to understand the personalization paradox.

The present results showed that intrusiveness attenuated the positive influence of relevance on attitudes toward the brand in the research context of Facebook. There has been extensive research on how personalized ads result in positive or negative responses by consumers in an online context and to some extent in a social media context (see Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017; Hayes et al. Citation2021). Few studies, however, have investigated the benefits of perceived personalization and relevance on attitudes toward the brand in a Facebook context (De Keyzer, Dens, and De Pelsmacker Citation2015), and none of these studies have combined the personalization-relevance-attitude model with the boundary condition of intrusiveness in a Facebook context. The focus on a Facebook context was important because users are assumed to be more personally and psychologically engaged with this platform than with any other social media platform (Voorveld et al. Citation2018). Consequently, feelings of intrusiveness and crossing personal boundaries seem to be especially relevant in this context. Our results indeed confirmed that intrusiveness was pivotal in reevaluating the perceived benefit of relevance of ad personalization in this specific context. However, it might be that consumers need to experience a certain threshold of intrusiveness to activate their reevaluation process of costs versus benefits. Future research could therefore further examine this threshold by comparing the interdependent effects of intrusiveness and relevance on brand attitudes in different online social media contexts in which consumers perceive different levels of psychological ownership.

Finally, the findings show that intrusiveness is an important boundary condition for the personalization-relevance-attitude model. However, this result brings up a question: What exactly causes the perception of intrusiveness? Although this question is outside the scope of the present study, it could be practically useful for advertisers to know what exactly causes ads to be perceived as highly intrusive (e.g., privacy violations, ad skepticism, general worries about misusing personal data), the relative contribution of these perceived costs of ad personalization, and the extent to which these perceived costs are interrelated to one another to downplay the effectiveness of ad personalization. Therefore, the next step to further develop the field would be to examine the drivers underlying intrusiveness in a social media context.

Limitations and Practical Implications

A potential limitation of the current study relates to its research design. Our research was only partly designed as an experimental study, as we manipulated only the personalization of the ad and not the perceived relevance or intrusiveness of the ad. The partly correlational design of the study does not permit drawing definite causal inferences on relationships between relevance and intrusiveness and brand attitude. More specifically, based on the literature, we assume that relevance affects brand attitude and that intrusiveness positively moderates this relationship. However, it is possible that attitude toward a brand might inversely shape perceptions in relevance and intrusiveness through a variety of other social psychological processes. For example, self-perception theory (Bem Citation1972) implies that when perceptions of ad relevance and intrusiveness are ambiguous or not really formed yet, one may deduce such beliefs by observing past behavior in relation to the brand or the attitude one has always had toward the brand. Experimental studies in which both perceived relevance and intrusiveness are manipulated next to personalization are needed to further examine causal relationships.

A convenience sampling method was used in the present study, which resulted in a sample that overrepresented females, people who were relatively young and well educated, and those who belonged in lower income groups. As a result of this self-selected sample, we should be careful in generalizing our findings to the population at large. Past research has shown that perceived personalization depends on sociodemographics such as age and education (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). These characteristics may change the relative contribution of the trade-off of benefits versus costs when evaluating the brand (i.e., privacy calculus). For example, younger people are relatively less likely to oppose ad personalization than older people (Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014), thereby potentially strengthening the mediating role of ad relevance but weakening the moderator role of intrusiveness. Although the findings of our study remained consistent when correcting for important confounding variables, the conclusion in relation to the strength of our hypothesized relationships remains tentative until the model is further validated in different representative (sub)samples of the Facebook population.

The main contribution of this study was to understand the causality and strength (internal validity) rather than the generalizability (external validity) between the relationships of actual and perceived personalization, relevance, and intrusiveness on the attitudes toward the brand. Even though this aim prevents us from making generalizations about how the investigated relationships might differ among various subgroups of customers or different social media platforms, the findings provide some useful general marketing implications.

One of these practical implication relates to the effectiveness of using personalized information on Facebook in general. That is, our results show that using personalized information in Facebook ads can be an effective way to promote a brand, as customers will perceive such ads as more relevant to them. However, it is advisable to evaluate the extent to which customers perceive such ads as intrusive, because they are likely to dismiss intrusive ads despite any relevance to them, this causing the ad to lose its effectiveness to promote a stronger brand attitude.

Another practical implication of our results relates to the distinction between actual and perceived personalization. In particular, our findings imply that to use ad personalization effectively a company should take special care to understand which types of personalization will be perceived as personal (and, consequently, relevant) to their customers. If there is a lack of knowledge about which characteristics and interests are appropriate for customers when exposing them to personalized ads, it will be less likely that consumers will perceive such ads as personal and relevant (Li Citation2016), while it simultaneously increases the likelihood of the ads being perceived as intrusive. These changes in perceptions will ultimately result in a weaker or even a negative impact of ad personalization. It is therefore of utmost importance that companies understand what elements of its messages may be best utilized for ad personalization—not only to increase the potential benefits of personalization (i.e., increasing the perceived personalization and the perceived relevance) but also to decrease the likelihood of feelings of intrusiveness.

References

- Aguirre, Elizabeth, Dominik Mahr, Dhruv Grewal, Ko de Ruyter, and Martin Wetzels. 2015. “Unraveling the Personalization Paradox: The Effect of Information Collection and Trust-Building Strategies on Online Advertisement Effectiveness.” Journal of Retailing 91 (1): 34–49.

- Ahn, Sun Joo., Joe Phua, and Yan Shan. 2017. “Self-Endorsing in Digital Advertisements: Using Virtual Selves to Persuade Physical Selves.” Computers in Human Behavior 71:110–121.

- Albert, Terry C., Paulo B. Goes, and Alok Gupta. 2004. “GIST: A Model for Design and Management of Content and Interactivity of Customer-Centric Web Sites.” MIS Quarterly 28 (2): 161–182.

- Anand, Bharat, and Ron Shachar. 2009. “Targeted Advertising as a Signal.” Quantitative Marketing and Economics 7 (3): 237–266.

- Arora, Neeraj, Xavier Drèze, Anindya Ghose, James D. Hess, Raghuram Iyengar, Bing Jing, Yogesh Joshi, Lurie V. Kumar, H. Nicholas, Scott Neslin, S. Sajeesh, Meng Su, Niladri B. Syam, Jacquelyn Thomas, and John Z. Zhang. 2008. “Putting One-to-one Marketing to Work: Personalization, Customization, and Choice.” Marketing Letters 19 (3): 305–321.

- Baek, Tae H., and Mariko Morimoto. 2012. “Stay Away from Me.” Journal of Advertising 41 (1): 59–76.

- Banerjee, Syagnik, and Ruby R. Dholakia. 2008. “Does Location-Based Advertising Work?” International Journal of Mobile Marketing 3 (2): 68–74.

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. “The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (6): 1173–1182.

- Bleier, Alexander, and Mark Eisenbeiss. 2015. “Personalized Online Advertising Effectiveness: The Interplay of What, When, and Where.” Marketing Science 34: 669–688.

- Bem, Daryl J. 1972. “Self-Perception Theory.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 6, ed. L. Berkowitz, 1–62. New York: Academic Press.

- Boerman, Sophie C., Sanne Kruikemeier, and Frederik J. Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2017. “Online Behavioral Advertising: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda.” Journal of Advertising 46 (3): 363–76.

- Bol, Nadine, Tobias Dienlin, Sanne Kruikemeier, Marijn Sax, Sophie C. Boerman, Joanna Strycharz, Natali Helberger, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2018. “Understanding the Effects of Personalization as a Privacy Calculus: Analyzing Self-Disclosure across Health, News, and Commerce Contexts.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 23 (6): 370–388.

- Brehm, Jack W. 1966. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Campbell, Damon E., and Ryan T. Wright. 2008. “Shut-Up I Don’t Care: Understanding the Role of Relevance and Interactivity on Customer Attitudes Toward Repetitive Online Advertising.” Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 9 (1): 62–76.

- Chatterjee, Patrali. 2008. “Are Unclicked Ads Wasted? Enduring Effects of Banner and Pop-Up Ad Exposures on Brand Memory and Attitudes.” Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 9 (1): 51–61.

- Chen, Qi, Yuqiang Feng, Luning Liu, and Xianyun Tian. 2019. “Understanding Consumers’ Reactance of Online Personalized Advertising: A New Scheme of Rational Choice from a Perspective of Negative Effects.” International Journal of Information Management 44:53–64.

- Cho, Chang-Hoan, and Hongsik John Cheon. 2004. “Why Do People Avoid Advertising on the Internet?” Journal of Advertising 33 (4): 89–97.

- Cohen, Jacob, Patricia Cohen, Stephen G. West, and Leona S. Aiken. 2003. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum.

- Daems, Kristien, Patrick De Pelsmacker, and Ingrid Moons. 2019. “Advertisers’ Perceptions regarding the Ethical Appropriateness of New Advertising Formats Aimed at Minors.” Journal of Marketing Communications 25 (4): 438–456.

- De Keyzer, Freya, Nathalie Dens, and Patrick De Pelsmacker. 2015. “Is This for Me? How Consumers Respond to Personalized Advertising on Social Network Sites.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 15 (2): 124–134.

- Dehling, Tobias, Yughen Zhang, and Ali Sunyaev. 2019. “Consumer Perceptions of Online Behavioral Advertising.” IEEE 21st Conference on Business Informatics 1:345–54.

- Edwards, Steven M., Hairong Li, and Joo-Hyun Lee. 2002. “Forced Exposure and Psychological Reactance: Antecedents and Consequences of the Perceived Intrusiveness of Pop-Up Ads.” Journal of Advertising 31 (3): 83–95.

- Feng, Xifei, Shenglan Fu, and Jin Qin. 2016. “Determinants of Consumers’ Attitudes toward Mobile Advertising: The Mediating Roles of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations.” Computers in Human Behavior 63:334–341.

- Field, Andy P. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS: (and Sex and Drugs and Rock 'n' Roll). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Gironda, John T., and Pradeep K. Korgaonkar. 2018. “iSpy? Tailored Versus Invasive Ads and Consumers’ Perceptions of Personalized Advertising.” Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 29 : 64–77.

- Gutierrez, Anabel, Simon O'Leary, Nripendra P. Rana, Yogesh K. Dwivedi, and Tatiana Calle. 2019. “Using Privacy Calculus Theory to Explore Entrepreneuraial Directions in Mobile Location-Based Advertising: Identifying Intrusiveness as a Critical Risk Factor.” Computers in Human Behavior 95:295–306.

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hayes, Jameson L., Guy Golan, Brian Britt, and Janelle Applequist. 2020. “How Advertising Relevance and Consumer–Brand Relationship Strength Limit Disclosure Effects of Native Ads on Twitter.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (1): 131–165.

- Hayes, Jameson L., Nancy H. Brinson, Gregory J. Bott, and Claire M. Moeller. 2021. “The Influence of Consumer–Brand Relationship on the Personalized Advertising Privacy Calculus in Social Media.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 55: 16–30.

- Jung, A-Reum. 2017. “The Influence of Perceived Ad Relevance on Social Media Advertising: An Empirical Examination of a Mediating Role of Privacy Concern.” Computers in Human Behavior 70: 303–309.

- Karwatzki, Sabrina, Olga Dytynko, Manuel Trenz, and Daniel Veit. 2017. “Beyond the Personalization–Privacy Paradox: Privacy Valuation, Transparency Features, and Service Personalization.” Journal of Management Information Systems 34: 369–400.

- Kim, Yoo Jung, and Jinyoung Han. 2014. “Why Smartphone Advertising Attracts Customers: A Model of Web Advertising, Flow, and Personalization.” Computers in Human Behavior 33:256–269.

- Kirk, Colleen P., Joann Peck, and Scott D. Swain. 2018. “Property Lines in the Mind: Consumers’ Psychological Ownership and Their Territorial Responses.” Journal of Consumer Research 45 (1): 148–168.

- Kramer, Thomas. 2007. “The Effect of Measurement Task Transparency on Preference Construction and Evaluations of Personalized Recommendations.” Journal of Marketing Research 44 (2): 224–233.

- Laczniak, Russell N., and Darrel D. Muehling. 1993. “Toward a Better Understanding of the Role of Advertising Message Involvement in Ad Processing.” Psychology and Marketing 10 (4): 301–319.

- Lancelot, Caroline, Sophie Cases, and Cristel A. Russell. 2019. “Consumers’ Responses to Facebook Advertising across PCs and Mobile Phones. A Model for Assessing the Drivers of Approach and Avoidance of Facebook Ads.” Journal of Advertising Research 59 (4): 414–432.

- Laufer, Robert S., and Maxine Wolfe. 1977. “Privacy as a Concept and a Social Issue: A Multidimensional Development Theory.” Journal of Social Issues 33 (3): 22–42.

- Lee, Eui-Bang, Sang-Gun Lee, and Chang-Gyu Yang. 2017. “The Influences of Advertisement Attitude and Brand Attitude on Purchase Intention of Smartphone Advertising.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 117 (6): 1011–1036.