Abstract

This study provides insight into Dutch adults’ awareness and perceptions of cross-media personalized advertising with a focus on synced advertising (SA). A survey among a representative sample of the Dutch population (N = 1,994) shows that the majority of people (>70%) are familiar with the collection, use, and sharing of information about their media behavior. People are less familiar with SA, which involves presenting targeted ads to consumers based on their current media behavior. Less than half of our sample (45%) were familiar with SA, and only 29% had ever experienced SA. The majority (75%) found SA (very) inappropriate. Moreover, our results showed that adults with low conspiracy mentality, those not concerned about their privacy, older adults, less-educated adults, and women are less aware of the collection, use, and sharing of media behavior and are less familiar with SA, and thus could benefit from literacy interventions to improve their understanding and resilience.

Data-driven personalized advertising has become increasingly common in digital advertising. An important trend within data-driven advertising is cross-media personalization, which involves personalizing ads on one medium while using data about behavior learned from another medium. For instance, when Consumer A searches for sneakers on her laptop, it leads to an ad for sneakers in her Instagram timeline on her phone later (i.e., online behavioral advertising [OBA] across media; Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). If this happens in real time and ads are targeted based on current media behavior (e.g., an ad for sneakers in Consumer A’s Instagram timeline while watching a TV program on sneakers), this practice is called synced advertising (SA; Segijn Citation2019).

Data-driven advertising has raised concerns about the collection, use, and sharing of personal data and about consumer privacy among advertisers, academics, regulators, and consumer organizations (e.g., Brinson, Eastin, and Cicchirillo Citation2018; Daems, De Pelsmacker, and Moons Citation2019; Van Ooijen and Vrabec Citation2019). Knowledge of personalization techniques is vital for consumer empowerment, and research has shown that higher privacy literacy likely leads to more privacy protection (e.g., Ham Citation2017, Desimpelaere, Hudders, and Van de Sompel Citation2021). Therefore, it is important to gain insights into people’s understanding of new forms of data-driven advertising, such as cross-media personalization. Moreover, it is imperative to understand which people are the least aware of, familiar with, and critical of these practices to identify who could benefit most from literacy interventions (Park Citation2013).

We contribute to the literature by using a nationally representative sample to gain insights into (1) Dutch adults’ awareness of the collection, use, and sharing of information about their media behavior; (2) Dutch adults’ familiarity with and perceptions of SA; and (3) the individual characteristics (e.g., conspiracy mentality, privacy concerns, and Internet skill levels) that are related to familiarity and perceptions. As most research focuses on U.S. citizens, our study contributes to the literature by providing a European perspective, which is particularly relevant given the strict privacy regulations in the European Union under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Moreover, this study contributes to a better understanding of people’s persuasion knowledge and perceptions of a new data-driven advertising strategy (i.e., SA) and of the role of relevant, novel individual characteristics, such as conspiracy mentality.

Awareness and Perceptions of Personalized Advertising

How people respond to and cope with advertising depends on their knowledge of the persuasion tactics used in advertising (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). Prior research has shown that people lack knowledge and hold misconceptions about data-driven advertising, such as OBA and SA (McDonald and Cranor Citation2010; Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2022; Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014). These insights mainly stem from research among U.S. consumers, with the exception of Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld’s (Citation2014) study, which was conducted among Dutch consumers before the introduction of the GDPR. The GDPR specifically states that consumers must be informed about data collection practices (Van Ooijen and Vrabec Citation2019), which increases their awareness of these practices (Segijn et al. Citation2021). Therefore, we ask the following research question:

RQ1: To what extent are Dutch adults aware of the collection, use, and sharing of information about their media behavior?

Persuasion knowledge is developmentally contingent, and people learn about persuasive tactics from firsthand experience and indirectly through conversations with others, as well as from media coverage (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). Although people may be familiar with personalized advertising in general, they may not know of the capacity for advertisers to use current media behavior to personalize ads on another medium. Indeed, research showed that U.S. adults lack knowledge of SA, and their confidence in that knowledge is low (Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2022). This finding may indicate a lack of familiarity and experience with SA, which can hinder the development of persuasion knowledge about SA. To get more insights into Dutch adults’ familiarity and experience, we ask:

RQ2: To what extent (a) are Dutch adults familiar with SA? (b) And have they ever experienced SA?

People are assumed to cope with advertising by accessing their persuasion knowledge to evaluate whether the tactic and the message align with their own goals (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). In the context of personalized advertising, this process is manifested in the privacy calculus (Dinev and Hart Citation2006), in which people weigh the benefits of a personalized ad (e.g., more useful and relevant messages) and the harms of the tactic (e.g., use of personal data, privacy infringement; Bol et al. Citation2018, Ham and Nelson 2016, Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2022). This calculus is also reflected in the personalization paradox: Personalization increases ad effectiveness (e.g., click-through rates) because an ad is more personally relevant to the consumer but also decreases effectiveness because it makes people feel vulnerable (Aguirre et al. Citation2015; Brinson, Eastin, and Cicchirillo Citation2018).

Prior research has shown that when people are asked about their perceptions, they find personalized advertising (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Bol Citation2021) and the various personalization techniques that enable SA (Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2020) unacceptable. In the context of SA, people may believe that an individual’s media behavior is very personal and that tapping into media behavior is too intrusive. This finding would suggest that the harm caused by SA may outweigh the benefits. We therefore ask:

RQ3: To what extent do Dutch adults find SA appropriate?

Role of Individual Characteristics

We explore which individual traits may be related to people’s knowledge and perceptions of personalized advertising based on media behavior. First, we introduce a person’s generic beliefs in conspiracy theories—or conspiracy mentality (Bruder et al. Citation2013)—as a likely influential characteristic. As personalized advertising, such as SA, requires the collection and processing of personal data by commercial companies, it is linked to feelings of intrusiveness (Van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013), vulnerability (Aguirre et al. Citation2015), and surveillance (Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2020). We propose that individuals with a higher propensity to believe in conspiracy theories are more likely to notice, understand, and critically evaluate data-driven commercial practices.

Second, we examine privacy concerns, defined as the extent to which people worry about their personal information being disclosed to others (Baek and Morimoto Citation2012). Privacy concerns play an important negative role in the acceptance and effectiveness of personalized advertising (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). We argue that people with high levels of privacy concerns may be more familiar with the collection, use, and sharing of their media behavior for personalized advertising and are probably more critical toward the practice.

Third, a person’s Internet skills (e.g., the ability to navigate the Internet and look for information online; Van Deursen, Helsper, and Eynon Citation2016) can be an important indicator for how well a person understands how information is processed online. As a higher level of Internet competency decreases the likelihood of clicking on a personalized ad (Kim and Huh Citation2017), we argue that Internet skills could be an important predictor of a person’s awareness of the collection, use, and sharing of media behavior and familiarity with and perceptions of SA.

Fourth, we include the frequency of using smartphones, social media, and Web browsers. The more people use these media, the more they are confronted with the collection of their (media behavior) data, and the more likely they are to be targeted with personalized ads on these devices. Therefore, we argue that a greater frequency of using these media increases the chance that people are aware that personal data are collected, used, and shared. In addition, because mobile phone dependency is related to the acceptance of personalized techniques (Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2020), we expect that the frequency of use is positively related to SA perceptions.

Finally, previous research has shown that age, gender, and education play a role in people’s understanding and evaluation of personalized advertising. For instance, studies have found generational differences regarding the acceptance of personalization techniques, with older generations being less accepting (Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2020); in addition, men and more highly educated people have reported more knowledge of personalization techniques (Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014, Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2022).

RQ4: How are individuals’ conspiracy mentality; privacy concerns; Internet skills; use of smartphones, social media, and Web browsers; age; gender; and education related to awareness and perceptions of SA?

Method

The data reported in this study are part of a larger cross-sectional survey on digital developments in communication (Araujo et al. Citation2020). Respondents were recruited through a commercial survey company. We used quota sampling on age, region, and gender interlocked with education to achieve a representative sample of the adult population (18 years or older) in the Netherlands. We excluded those who completed the survey too quickly to have engaged with it, as well as respondents who were younger than 18, did not consent to the use of their data, or failed both attention checks. The final sample consisted of 1,994 responses.

presents all measures. All 547 open answers were coded by one of the researchers, and 18% were double coded by the second researcher (intercoder agreement was good; Cohen’s kappa = 0.80, p < .001). We excluded invalid answers (e.g., “Don’t know” [n = 217]; mention of a brand/product only [n = 146]), which left 211 useful answers.

Table 1. Overview of measures and descriptive statistics.

Results

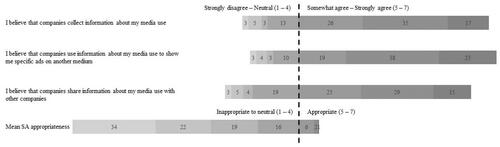

Regarding research question 1, we found that most respondents were aware that companies collect, use, and share information about their media use (M = 5.26, SD = 1.30). Focusing on scores 5 through 7 (), 77% believed that companies collect information about media use, 80% believed that media behavior data are used to show specific ads on another medium, and 70% believed that these data are shared with other companies.

Figure 1. Percentage of scores for awareness items and mean synced advertising (SA) appropriateness.

Concerning research question 2, we find that 45% of respondents in our sample said they were familiar with SA, and 29% had experienced SA. However, when asking these respondents for a concrete example, only 22% of the answers reflected a form of cross-media advertising or SA. Most of these answers concerned personalized advertising across different media (e.g., “Ad on social media for duvet covers after seeing it on TV”). Some of the answers did reflect SA (e.g., “I watched a cooking show with a specific kind of pans and got the same pans on my phone at the same time”). In addition, 37% were examples of OBA on the same medium (“I searched for kitchens on the www, after that on [Facebook] ad for it” and “An online purchase. After that, advertising about such things”), and 38% of the answers reflected the idea of companies listening to conversations (“It was a clothing brand. While I was talking about the brand, I directly got a message from the brand”). Finally, 3% of the answers concerned location-based advertising (“Electric bikes after I went to a specific store”).

Regarding research question 3, results showed that the majority of Dutch adults find SA inappropriate (M = 2.74, SD = 1.43). shows the distribution of SA appropriateness: 75% find SA inappropriate (scores 1 to 3.8), and only 8% find SA appropriate (scores 5 to 7).

To answer research question 4, we ran linear regression analyses for awareness of the collection, use, sharing of media behavior and SA appropriateness, and we ran logistic regression analyses for SA familiarity and SA experience. The results ( and ) showed that several characteristics were significantly related to the four dependent variables. Conspiracy mentality was positively related to awareness of the collection, use, and sharing of media behavior, SA familiarity, and SA experience and negatively related to appropriateness. Privacy concerns were positively related with awareness and SA familiarity and negatively related with SA appropriateness. Internet skills were not significantly related to awareness and perceptions of SA. Greater frequency of the use of Web browsers increased awareness and SA familiarity; the frequency of using smartphones and social media increased the likelihood of having experience with SA; and the use of social media was positively related to SA appropriateness. Age had a negative relationship with all dependent variables. In addition, women were less aware of the collection, use, and sharing of media behavior and less familiar with SA but more critical toward it. Finally, less educated adults were less aware of the collection, use, and sharing of their media behavior and less familiar with SA.

Table 2. Results of linear regression analyses predicting awareness and appropriateness.

Table 3. Results of logistic regression analyses predicting synced advertising (SA) familiarity and experience.

Conclusion and Discussion

This study shows that the majority of Dutch adults (>70%) are familiar with the collection, use, and sharing of information about their media behavior. This is in line with the GDPR, which requires companies to inform consumers that—and how—data collection takes place. In addition, 45% of Dutch adults were familiar with personalized ads based on their current media behavior (SA), and 29% had experienced SA. These findings suggest that Dutch adults seem to have developed some level of persuasion knowledge of SA despite having little experience with the tactic, possibly from media coverage or secondhand experience. These results add to the literature by using a non-U.S. sample, which is important given differences between countries’ privacy regulations.

Many of our respondents connected personalized advertising based on media behavior to companies listening to their conversations, which is labeled as the surveillance effect (Frick et al. Citation2021). As there is no empirical evidence that smart devices listen to conversations and transmit these recordings to companies for the purpose of personalizing online ads (Frick et al. Citation2021), our findings suggest that people’s persuasion knowledge could be based on folk theories or misinformation. Although our results provide important insights into the current level of knowledge of personalization and data collection practices, future research should further investigate how consumers develop such knowledge, the consequences of their (mis)perceptions, and ways to combat misinformation about advertising.

Our study makes an important theoretical contribution by introducing conspiracy mentality as a relevant personal trait that should be taken into consideration in the context of data-driven advertising. We found that a person’s belief in conspiracy theories is related to awareness of data-driven advertising techniques and critical evaluations of such practices. Future research should further examine whether conspiracy mentality plays an important (moderating) role in the effectiveness of personalized advertising.

Moreover, the majority of Dutch adults (75%) find SA (very) inappropriate. In light of the privacy calculus, this finding suggests that tapping into personal media behavior for ad personalization is believed to be too intrusive (Segijn and Van Ooijen Citation2022) and thus potentially outweighs the benefits of personalization. Importantly, these negative perceptions may also spill over to brands (Aguirre et al. Citation2015), suggesting that brands using SA could be harmed by it. More research on the unintended side effects of SA is needed.

Furthermore, our results suggest that adults with low conspiracy mentality, those not concerned about their privacy, older adults, less-educated adults, and women are less aware of the collection, use, and sharing of media behavior and less familiar with SA. This suggests that these individuals could benefit from literacy interventions to improve their understanding and resilience.

As this study concerns cross-sectional data, we should be careful in interpreting the causality of our findings. For instance, it could be that people who have more experience with SA become more concerned about their privacy, and that being aware that their data are being collected, used, and shared causes a growth in conspiracy mentality. Further, longitudinal or experimental research is needed to gain more insights into the causality of these relationships.

Finally, respondents’ open answers highlight an important methodological implication when using self-reported awareness measures. Judging from the open answers, SA familiarity may be lower than people report. As only 22% of the valid answers reflected some kind of cross-media personalized advertising (including SA), people may overestimate their own knowledge and conflate SA with other personalization techniques. Researchers should be careful when using and drawing conclusions based on self-reported awareness of personalization techniques.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguirre, Elizabeth, Dominik Mahr, Dhruv Grewal, Ko de Ruyter, and Martin Wetzels. 2015. “Unraveling the Personalization Paradox: The Effect of Information Collection and Trust-Building Strategies on Online Advertisement Effectiveness.” Journal of Retailing 91 (1): 34–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.09.005.

- Araujo, Theo, Mark Boukes, Damian Trilling, Marieke Van Hoof, Rebecca Wald, and Dong Zhang. 2020. “Communication in the Digital Society Survey in The Netherlands.” doi:https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YU64R.

- Baek, Tae H., and Mariko Morimoto. 2012. “Stay Away from Me.” Journal of Advertising 41 (1): 59–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367410105.

- Boerman, Sophie C., Sanne Kruikemeier, and Nadine Bol. 2021. “When is Personalized Advertising Crossing Personal Boundaries? How Type of Information, Data Sharing, and Personalized Pricing Influence Consumer Perceptions of Personalized Advertising.” Computers in Human Behavior Reports 4: 100144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100144.

- Boerman, Sophie C., Sanne Kruikemeier, and Frederik J. Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2017. “Online Behavioral Advertising: A Literature Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Advertising 46 (3): 363–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1339368.]

- Boerman, Sophie C., Sanne Kruikemeier, and Frederik J. Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2021. “Exploring Motivations for Online Privacy Protection Behavior: Insights from Panel Data.” Communication Research 48 (7): 953–977. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218800915.

- Boerman, Sophie C., Eva Van Reijmersdal, Esther Rozendaal, and Alexandra L. Dima. 2018. “Development of the Persuasion Knowledge Scales of Sponsored Content (PKS-SC).” International Journal of Advertising 37 (5): 671–697. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1470485.

- Bol, Nadine, Tobias Dienlin, Sanne Kruikemeier, Marijn Sax, Sophie C. Boerman, Joanna Strycharz, Natali Helberger, and Claes H. De Vreese. 2018. “Understanding the Effects of Personalization as a Privacy Calculus: analyzing Self-Disclosure across Health, News, and Commerce Contexts.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 23 (6): 370–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy020.

- Brinson, Nancy H., Matthew S. Eastin, and Vincent J. Cicchirillo. 2018. “Reactance to Personalization: Understanding the Drivers behind the Growth of Ad Blocking.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 18 (2): 136–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1491350.

- Bruder, Martin, Peter Haffke, Nick Neave, Nina Nouripanah, and Roland Imhoff. 2013. “Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire.” Frontiers in Psychology 4: 225. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225.

- Daems, Kristien, Patrick De Pelsmacker, and Ingrid Moons. 2019. “Advertisers’ Perceptions regarding the Ethical Appropriateness of New Advertising Formats Aimed at Minors.” Journal of Marketing Communications 25 (4): 438–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1409250.

- Desimpelaere, Laurien, Liselot Hudders, and Dieneke Van de Sompel. 2021. “Children’s Perceptions of Fairness in a Data Disclosure Context: The Effect of a Reward on the Relationship between Privacy Literacy and Disclosure Behaviour.” Telematics and Informatics 61: 101602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101602.

- Dinev, Tamara, and Paul Hart. 2006. “An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions.” Information Systems Research 17 (1): 61–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1060.0080.

- Frick, Nicholas R., Konstantin L. Wilms, Florian Brachten, Teresa Hetjens, Stefan Stieglitz, and Björn Ross. 2021. “The Perceived Surveillance of Conversations through Smart Devices.” Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 47: 101046. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2021.101046.

- Friestad, Marian, and Peter Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1): 1–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209380.

- Ham, Chang-Dae. 2017. “Exploring How Consumers Cope with Online Behavioural Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (4): 632–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1239878.

- Ham, Chang-Dae, and Michelle R. Nelson. 2016. “The Role of Persuasion Knowledge, Assessment of Benefit and Harm, and Third-person Perception in Coping with Online Behavioral Advertising.” Computers in Human Behavior 62 (2016): 689–702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.076.

- Kim, Hyejin, and Jisu Huh. 2017. “Perceived Relevance and Privacy Concern regarding Online Behavioural Advertising (OBA) and Their Role in Consumer Responses.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 38 (1): 92–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2016.1233157.

- Kruikemeier, Sanne, Sophie C. Boerman, and Nadine Bol. 2020. “Breaching the Contract? Using Social Contract Theory to Explain Individuals’ Online Behaviour to Safeguard Privacy.” Media Psychology 23 (2): 269–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1598434.

- McDonald, Aleecia M. and Lorrie F. Cranor. 2010. “Beliefs and Behaviours: Internet Users’ Understanding of Behavioural Advertising,” TPRC 2010. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1989092

- Park, Yong J. 2013. “Digital Literacy and Privacy Behavior Online.” Communication Research 40 (2): 215–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211418338.

- Segijn, Claire M. 2019. “A New Mobile Data Driven Message Strategy Called Synced Advertising: Conceptualization, Implications, and Future Directions.” Annals of the International Communication Association 43 (1): 58–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2019.1576020.

- Segijn, Claire M., Joanna Strycharz, Amy Riegelman, and Cody Hennesy. 2021. “A Literature Review of Personalization Transparency and Control: Introducing the Transparancy-Awareness-Control Framework.” Media and Communication 9 (4): 120–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i4.4054.

- Segijn, Claire M., and Iris Van Ooijen. 2020. “Perceptions of Techniques Used to Personalize Messages across Media in Real Time.” Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking 23 (5): 329–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0682.

- Segijn, Claire M., and Iris Van Ooijen. 2022. “Differences in Consumer Knowledge and Perceptions of Personalized Advertising: Comparing Online Behavioural Advertising and Synced Advertising.” Journal of Marketing Communications 28 (2): 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2020.1857297.

- Smit, Edith G., Guda Van Noort, and Hilde A. M. Voorveld. 2014. “Understanding Online Behavioural Advertising: User Knowledge, Privacy Concerns and Online Coping Behaviour in Europe.” Computers in Human Behavior 32: 15–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.008.

- Van Deursen, Alexander J. A. M., Ellen J. Helsper, and Rebecca Eynon. 2016. “Development and Validation of the Internet Skills Scale (ISS).” Information, Communication & Society 19 (6): 804–823. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1078834.

- Van Doorn, Jenny, and Janny C. Hoekstra. 2013. “Customization of Online Advertising: The Role of Intrusiveness.” Marketing Letters 24 (4): 339–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-012-9222-1.

- Van Ooijen, Iris, and Helena U. Vrabec. 2019. “Does the GDPR Enhance Consumers’ Control over Personal Data? An Analysis from a Behavioural Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Policy 42 (1): 91–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-018-9399-7.