Abstract

We examined the association of intrusive and sexually appealing advertisements in a mobile news environment with audiences’ perceptions of the content and reactive behaviors. Based on the psychological reactance theory, we conducted a 2 × 2 (sexual ad versus nonsexual ad × highly intrusive ad versus low intrusive ad) full factorial experimental design measuring associations with behavioral ad avoidance and ad memory (recall and recognition). The results indicate that users were more concerned to avoid pop-up ads than banner ads. Also, we observed significant main effects of intrusiveness and sexual appeals in advertisements on audiences’ recall of ads. Our findings call into question the effectiveness of advertising that relies on intrusive exposure and sexual images.

With the expansion in the use of smartphones around the world, news is increasingly consumed in mobile contexts (Newman et al. Citation2018) and often in public spaces, such as while waiting in lines at stores or on the subway. Responding to this trend, advertisers have focused on smartphones as a medium, seeking to maximize the reach and appeal of advertisements in mobile settings by making them more intrusive or sexually alluring. Generally, pop-up advertisements, a floating format—that is, a format that is not part of a web page but appears unexpectedly on the viewer’s screen—are more intrusive than banner-type advertisements. Also, sexually appealing advertisements may attract the attention of audiences by appealing to their instincts. Consumers may encounter such advertisements frequently while consuming information through their smartphones.

Studies of the effectiveness of intrusive and sexually appealing advertisements have been conducted in various national contexts. The results suggest that in South Korea (hereafter Korea) pop-up advertisements tend to be more expensive than banner-type ads (Interworks Citation2019) but also, according to Bae and Park (Citation2018), who gathered empirical evidence about the effectiveness of advertisements centered on the click-through ratio (CTR), more effective. Reichert (Citation2002, Citation2003) reported that sexual appeals were common in various kinds of U.S. advertisements and captured the interest of audiences in cluttered media circumstances. The widespread use of sexual images indicates the widespread belief that such imagery is effective.

However, there remains a fundamental question regarding whether evidence of the CTR is sufficient to conclude that pop-up advertisements can be more effective than banner ads on mobile news sites. More specifically, it is unclear whether marketers have been achieving the desired effect with forced-exposure advertisements or whether sexual imagery can, indeed, enhance the effectiveness of at least some advertisements. Answers to such questions can inform efforts to create a better media environment and advance the understanding of what makes an advertisement effective. Some mobile users may intentionally avoid advertisements because of the unpleasant feelings that online advertisements elicit (Cho and Cheon Citation2004).

Reactance theory offers a theoretical basis for understanding audiences’ perceptions of intrusive and sexually appealing advertisements from the perspective of individuals’ responses to situations in which they perceive that their freedom to engage in a specific behavior is being limited (Brehm Citation1966). Reactance tends to occur when the background information is meaningless or irrelevant to the primary target (Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002; Tourangeau and Rasinski Citation1988). In designing this study, we reasoned that both intrusive and sexually appealing advertisements could trigger reactance behavior because the format (intrusiveness) and content (sexual imagery) may interrupt information processing on smartphones. That is, in a mobile environment in which relatively small screens and font sizes hinder information processing (Dunaway and Soroka Citation2021), visually noticeable stimuli may induce individual reactance.

The purpose of this study, then, was to assess the influence of ad format (pop-up or banner) and content (with or without sexual imagery) on cognitive perceptions that manifest in the behaviors of ad avoidance and ad memory. We conducted an online experiment that mimicked a real-world mobile setting with a sample of 480 adults from across Korea. We then performed a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to interpret their responses. From a theoretical perspective, we approached intrusive and sexually appealing advertisements as causes of individual reactance. The results can be of use in formulating practical guidelines for the design of mobile advertisements.

Theoretical Background

Intrusive and Sexually Appealing Advertisements

For Internet users whose main goal is consuming information, advertisements on websites often appear unexpectedly and hinder their efforts to gather and process information. Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders (Citation2010) introduced the concept of “expectancy violation” to describe such experiences, arguing that audiences judge websites based on their expectations regarding appearance and functionality. Thus, expectancy violations resulting from intrusive pop-ups and sexually provocative content may distract and irritate visitors to websites who are seeking information. Li, Edwards, and Lee (Citation2002) defined ad intrusiveness as a “psychological consequence that occurs when an audience’s cognitive processes are interrupted” (p. 39), including when confronted with advertisements that they deem excessive and intrusive on websites. Readers of online news articles may perceive intrusive advertisements as a threat to or loss of control over their information-processing efforts. Such “interruption to the cognitive process relating to the active task caused by the advertisement” has been described as “flow disruption” (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018, p. 760).

The amount of flow disruption that consumers of online news experience depends in part on the type of intrusive advertisement, banner or pop-up. Banner ads usually combine various multimedia features and are located at the top of the websites without obscuring content. Pop-up ads, on the other hand, also combine multimedia features but appear as relatively small windows superimposed over the website that block some of the content. While pop-up ads tend to be successful in attracting attention, users consider this the most annoying form of online advertising (Coursey Citation2001). Of importance for marketers is that intrusiveness in online advertisements often correlates negatively with purchase intention—the stimulation of which is, of course, the purpose of advertising (Goldfarb and Tucker Citation2011; van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013).

Turning now to sexually appealing advertisements, Reichert, Heckler, and Jackson (Citation2001) defined sexual appeals as messages and images that elicit sexual thoughts and feelings. Sexual appeals or cues have long been common in many forms of advertising (Reid and Soley Citation1983; Reichert Citation2003), their purpose being to attract and retain viewers’ attention (Liu, Cheng, and Li Citation2009). Scholars have reached various conclusions regarding the impact of such appeals. In addition to attracting attention in cluttered media environments as just described, studies have suggested that sexually appealing advertising can enhance the recall of a message (Steadman Citation1969), brand and memory recall (Shimp Citation2007), and emotional reactions (Lombardot Citation2007). Such responses precede cognitive processing.

On the other hand, some studies have reported negative effects of sexual appeals in advertising. To begin with, some audiences may perceive sexual appeals as unethical and offensive (LaTour and Henthorne Citation1994; Tai Citation1999). Further, such appeals may disrupt the cognitive processing of brand-related information (Samson Citation2018) because audiences find them more vivid than the message that the advertiser seeks to convey (Reichert Citation2002). Also problematic from a marketing perspective are sexual appeals in advertisements that lack a meaningful connection with the product being advertised, for there is evidence that any enhancement of brand recall depends on a clear relationship between the product and advertisements for it (Richmond and Hartman Citation1982). In the case of news websites, sexually appealing advertisements rarely if ever have such a connection to the product, so we expected that they would interfere with processing of the messages of articles on news websites.

Reactance Theory

Psychological reactance theory emphasizes individuals’ motivational reactions when they perceive that their freedom to engage in specific behaviors is threatened or restricted (Brehm Citation1966; Hannah, Hannah, and Wattie Citation1975) and, as such, is an aversive motivational state. Freedom and autonomy are usually understood as pertaining to the satisfaction of the basic human need for self-governance (Gardner and Leshner Citation2016). This notion of volitional autonomy originated in individual interests (Jung Citation2011). The basic premise of reactance theory is, then, that individuals desire freedom and react negatively when external forces impinge upon it—such as unexpected interruptions of their activities online. Therefore, consumers of information on websites may experience negative reactions to online advertisements, such as hostility and aggression (Kim, Levine, and Allen Citation2017).

Individuals who perceive freedom of choice to be important for their media consumption activities display reactive behavior when this expectation is violated (Clee and Wicklund Citation1980). While viewing online news sites that display advertisements, users may perceive certain advertisements or attempts at persuasion as coercive or featuring inappropriate content (McCoy et al. Citation2017), because such stimuli impede their rational thought processes and, thereby, restrict their freedom of choice. They are then prone to retaliate against the stimulus to restore their perceived loss of control.

As articles can influence the cognitive understanding of advertisements, advertisements can influence consumption of articles on online news sites. As noted, the main themes of news articles and content in advertisements are often unrelated, and the goals of online news readers tend to be incompatible with those of online advertisers (Danaher and Mullarkey Citation2003). Online readers are goal oriented (You et al. Citation2013), but online advertisements are designed to distract those readers’ attention away from their goals and toward advertisers’ products. Edwards, Li, and Lee (Citation2002) argued that when media audiences feel their freedom of choice is threatened they actively seek to avoid responding in the ways that advertisers would like. In other words, consumers tend to ignore marketers’ attempts at persuasion when they find their advertisements disruptive. Similarly, Morimoto and Chang (Citation2006) found that the recipients of unsolicited e-mails considered them to be more intrusive and irritating than other forms of commercial e-mail, suggesting that the recipients engaged in reactive behavior. As alluded to earlier, the smaller screens and font sizes characteristic of mobile environments can hinder information consumption (Amazeen Citation2021; Dunaway and Soroka Citation2021) and, therefore, exacerbate such behavior.

In this study, then, we considered pop-up advertisements and sexually appealing advertisements on news sites to be potential triggers for reactive behavior. That is, we expected that the participants’ negative reactions to such advertisements would interfere with their news consumption more than banner ads or ads lacking sexual content. The unpleasant feeling of interruption would, then, result in hostility toward not only the advertisements but also the websites on which they appear.

Ad Avoidance As a Reactive Activity

Speck and Elliott (Citation1997) drew on reactance theory in defining ad avoidance as “all actions by media users that differently reduce their exposure to ad content” (p. 61). Thus, ad avoidance is the process of visually screening out the advertisements embedded within the content of interest to a consumer or user. Such behavior may not be conscious. Because online news consumers are by definition goal oriented—their goal being the consumption of new information (You et al. Citation2013)—we expected that material unrelated to the content of news articles would elicit hostility and discomfort, hinder information consumption, and encourage ad avoidance.

Cho and Cheon (Citation2004), in assessing online consumers’ ad avoidance behaviors, coined the term “banner blindness” to describe those inclined to avoid directing their attention to any content related to banner advertisements on the visual periphery. Pop-up ads, as discussed, interrupt browsing by blocking content and so can be expected to elicit such behavior. Specific forms of ad avoidance include, in addition to banner blindness, automatically disregarding floating ads, installing ad-blocking software (Brinson, Eastin, and Cicchirillo Citation2018), and rapidly scrolling through sites. According to Cho and Cheon (Citation2004), users tend to avoid advertisements on the Internet for one of three reasons: because the ads impede their goals, because they cause clutter, and because of prior negative experiences. Taking these reasons in turn, as discussed, online advertisements impede information processing, which is a key part of online news consumption. Clutter, which relates in this context to the number of online advertisements displayed on a website, reinforces users’ perception that online advertisements are redundant (Speck and Elliott Citation1997). As for previous negative experiences, it is obvious that these directly impact individuals’ attitudes and behaviors, including marketing (Zanna, Olson, and Fazio Citation1981). Thus, those who visit websites, having learned from experience that clicking on the advertisements is dissatisfying, may intentionally avoid online advertisements and information sources.

Scholars explained advertisement avoidance with reference to consumers’ decision processes (Bettman and Park Citation1980; Cho and Cheon Citation2004): An individual response to an advertisement extends from cognition (C) through affect (A) to behavior (B). From this perspective, various types of ad avoidance can be distinguished: cognitive avoidance refers to negative evaluations of ads (e.g., ignoring ads); affective avoidance refers to emotional reactions to ads (e.g., feeling disgust toward ads), and behavioral avoidance refers to specific actions (e.g., clicking away from ads).

Previous studies of ad avoidance have taken into account a wide range of interruptive advertisement situations, including pop-up ads (Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002), online ads (Cho and Cheon Citation2004), and ads on Facebook (Youn and Kim Citation2019). We focused on online advertisements that accompanied articles posted on news sites on a mobile platform. Specifically, we investigated whether intrusive ads—in particular, pop-ups and ads with sexually provocative content—being incompatible with the news content, would elicit avoidance behaviors. Again, the pop-up ads elicit reactance because they interrupt users’ primary activity by visually hiding news content (Cho and Cheon Citation2004). Also, negative and obtrusive advertisements may raise concerns about online privacy (Goldfarb and Tucker Citation2011; van Doorn and Hoekstra Citation2013), with the unexpected appearance of intrusive advertisements suggesting to media consumers the possibility that their personal information is being tracked by online advertisers (Estrada-Jiménez et al. Citation2017). In addition, as noted, sexual advertisements are rarely relevant to news articles, so media consumers may be inclined to regard them as clutter and distractions from their primary activity (Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002; Tourangeau and Rasinski Citation1988) and to respond with reactance behavior. Furthermore, a synergistic interaction effect of ad avoidance on users may be likely to occur when sexually provocative ads appear in pop-up format. Specifically, because both pop-up and sexually provocative advertisements can hinder readers’ information processing, the combination of these two elements on news sites may amplify clutter and further lead to ad avoidance for consumers.

Based on these arguments, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H1(a): Media consumers are more likely to engage in ad avoidance when exposed to pop-up ads than when exposed to banner ads.

H1(b): The presence of sexual imagery in ads increases the likelihood that media consumers will engage in ad avoidance.

H2: The pop-up format and sexual imagery jointly show a positive interaction effect on media consumers’ likelihood of ad avoidance.

Ad Memory: Recall and Recognition

The hierarchy of effects model (Lavidge and Steiner Citation2000) distinguishes three stages of advertisement effects: cognitive, affective, and conative. Ad memory is one of the indicators that serves to measure the effects of advertisements in the cognitive stage (Barry and Howard Citation1990). Generally, ad memory consists of two subconstructs: recall and recognition. Recall memory is a less sensitive measure than recognition memory (Tulving Citation1979). In information retrieval, recall memory is operationalized as the ability to access relevant information unassisted and recognition memory as the ability to access information that matches a given stimulus (Wirtz, Sparks, and Zimbres Citation2018). Put another way, recall and recognition determine whether a given piece of information is stored in memory (Lang Citation2000). Therefore, recognition memory is generally measured using multiple-choice or true/false questions (e.g., Diao and Sundar Citation2004; McCoy et al. Citation2017).

McCoy et al. (Citation2017) hypothesized that when media users perceive online advertisements to be coercive or intrusive, they are more likely to recall the content than when presented with more bland appeals. Their rationale was that media users’ attention shifts from the original content (e.g., a news article) to the intrusive content (i.e., advertisements), but they did not consider the negative context effects of advertisements. In light of this consideration, we formed the opposite hypothesis, reasoning that the perceived distraction caused by a forced-exposure advertisement may cause individuals to perceive it as an impediment to their goal of consuming news content and, therefore, engagement in ad avoidance occurs, making it less likely that they will remember the advertisement’s content. In fact, some empirical evidence supporting this interpretation has already been provided by Diao and Sundar (Citation2004), who found that pop-up ads induced lower ad recognition memory than banner ads.

A meta-analysis by Wirtz, Sparks, and Zimbres (Citation2018) of research on the effects of exposure to sex appeals in advertisements on memory found different effects on brand memory and ad memory, the measures for which, they acknowledged, were almost the same. Other researchers have argued that brands may be remembered less accurately when they are featured in ads with sex appeal than when they are featured in ads without sex appeal (Bushman Citation2005; Parker and Furnham Citation2007). The rationale is that when individuals encounter an ad with sex appeal, their cognitive resources become more focused on the content than the brand being advertised (Reichert and Alvaro Citation2001). Also, advertisements with sex appeal tend to generate inappropriate schemas, especially when audiences are consuming complicated information. That is, though sexual content may initially attract users’ attention, the effect cannot be sustained because the perception that the schema is inappropriate causes them to ignore the stimulus. Specifically, the combination of pop-up (Diao and Sundar Citation2004) and sexually provocative (Bushman Citation2005; Parker and Furnham Citation2007) advertisements on news sites may severely interfere with consumers’ memory of advertisements.

Accordingly, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H3(a): The negative effect of the pop-up format on media consumers’ ad memory is greater than that of the banner format.

H3(b): The negative effect of sexual imagery on media consumers’ ad memory is greater than that of nonsexual imagery.

H4: The pop-up format and sexual imagery jointly have an interaction effect on ad memory.

Methodology

The purpose of the current study was to examine the mutual cognitive influence of advertisements and media content in a realistic context. To do so, we showed the participants in the main experiment news articles that we had fabricated and attributed to a real Korean news outlet, Yonhap News Agency, in association with advertisements. Prior to the main experiment, we conducted a focus-group interview with college students (N = 11) to learn about their experiences of consuming news articles in a mobile environment. Several members of the focus group expressed negative opinions about advertisements relating to volume, intrusiveness, and sexual content, and we chose to focus on the latter two of these issues.

Pilot Study

Also prior to the main study, we conducted a pilot test to evaluate intrusiveness and sexuality with respect to the types and contents of advertisements. For this purpose, we recruited 62 undergraduate students from a university in Seoul, of whom 54.8% were female and 45.2% were male; their average age was 21.3 years. We used a 2 × 2 factorial design, specifically, high intrusiveness versus low intrusiveness × sexuality versus no sexuality factorial. In manipulating the intrusiveness of the advertisements, we consulted the Better Ads Standards (betterads.org, 2017) for consumers’ least-preferred ad formats, which included, in addition to pop-ups, sticky ads and flashing animated ads. From among these, we chose a floating ad combining pop-up and sticky formats and a banner ad with a density of greater than 30% of the screen. The floating ads were one-third the size of the banner ads but obscured the content (i.e., the text of the associated news articles). We chose these types of ads because they were the most common in the Korean mobile Web environment at the time we conducted the study. The pop-up ads represented the high-intrusive condition and banner ads the low-intrusive condition.

To manipulate level of sexuality, we selected urology ads with a sensational image as the high-sexuality condition and a Korean mobile carrier’s rate plan ads as the no-sexuality condition. We assigned the participants randomly to one of four conditions and asked them to read an assigned news article carefully in which one of four manipulated ads appeared. Then, they answered questions concerning the advertisements’ levels of intrusiveness and sexuality on a 5-point scale. Finally, the participants responded to some demographic questions. The results of the pilot test confirmed that we successfully manipulated both intrusiveness level (floating [4.57] > banner [3.92], F = 7.03, df = 1, p < .01) and sexuality level (sexuality [4.7]) > no sexuality [2.0], F = 246.04, df = 1, p < .001).

Design and Participants

For the main experiment, we adopted the 2 × 2 full factorial experimental design described previously. We used three kinds of news articles to minimize the influence of the news content. Thus, we exposed each of the participants randomly to one of 12 conditions. A total of 480 adult respondents from across Korea participated in the online experiment. We recruited them through a specialized research institute using a quota-sampling method based on gender and age groups (i.e., ages 18–35, 35–50, and over 50 years). The criteria for participation limited the respondents to adults who regularly consumed news in the mobile environment. Among the 480 respondents, 16 did not complete their questionnaires, so we excluded them from the analysis. Thus, a total of 464 participated in the full experiment. The gender breakdown of the sample was 50.4% (N = 234) male and 49.6% (N = 230) female, while the age distribution ranged from 20 to 63 years, with an average of 40.73.

Experimental Stimuli

We created the experimental stimulus to mimic the experience of reading news articles in a real-world Korean mobile environment, designing the stimulus web page to resemble a typical mobile online news site. We sourced the articles from Yonhap News Agency because this news wire outlet tends to be considered fairly neutral politically (Lim Citation2011). The participants accessed the online experiments through their Web browsers, where experimental stimuli and questionnaires were distributed through a paid online survey platform. Thus, despite using Web browsers for the experiment, the participants consumed the news articles in a mobile format, with the stimuli closely resembling a real-world mobile news environment with respect to screen proportions and display of banner and pop-up advertisements.

To manipulate intrusiveness by types of ads, we used the floating format ad and banner format ad verified by the pilot test after a minor modification. Specifically, to clarify the difference in the intrusiveness of the two types of ads, we increased the size of the floating ad slightly while the size of the banner ad remained the same. The difference in invasiveness between the two types depended on whether the ads directly obscured the content of the news articles. For the sexuality condition, we used a rear view of a woman clad only in underwear. For the no-sexuality condition, the image was a mobile phone with the carrier’s logo. To control other variables, we restricted ad content to include only a slogan and the name of the advertiser. In addition, we used three up-to-date published news stories to control for other confounding variables, such as the participants’ commitment to the story. The topics were the minimum wage, conscientious objection to military service, and an act of violence committed by a company’s chief executive officer, all in Korean contexts and involving only objective reporting of the facts. We conducted a MANOVA to measure the main effects of the three news articles and the interaction effects on the dependent variables. As shown in , the results for the confounding effects of the three articles indicated that neither of the independent variables in this study (i.e., ad format or ad content) was significantly associated with the dependent variables (ad avoidance or ad memory) for any of the articles.

Table 1. Effects of news type on the dependent variables (confounding effects).

Procedure

We informed the participants that they would be involved in a survey of their perceptions of online news and news agencies. We then assigned them randomly to one of 12 research conditions to watch one of three news stories accompanied by one of the four versions of the ads. Before we exposed the participants to the research stimuli, we asked them to describe their attitudes toward Yonhap News Agency and the frequency of their media consumption. We designed the interface so that the participants could click on the ad after reading the news article with which it was associated or read a longer article without the ad. After viewing the advertisements, the participants rated the intrusiveness and sexuality of the ads. Finally, we asked them to answer questions designed to assess their memories of the ads.

Measures

We measured the perceived intrusiveness of the ads using three items (e.g., “I thought the ad was intrusive”) that Edwards, Li, and Lee (Citation2002) used in their study of ad intrusiveness. The participants assessed all of the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree (α = .897). We measured perceived sexuality using versions of three items that Brotto, Yule, and Gorzalka (Citation2015) developed after modifying them for the purposes of the current study (e.g., “I thought the ad was obscene”) and the same 5-point scale (α = .921). We used three items to measure avoidance behavior (e.g., “I purposely ignored the content of the ad”). Cho and Cheon (Citation2004) and Lee and Lyu (Citation2005) respectively developed a three-dimensional ad-avoidance scale including cognitive, physical, and mechanical dimensions, of which we used the first only. Finally, we measured the participants’ ad memory by assessing their ad recall and ad recognition. Diao and Sundar (Citation2004) measured ad memory based on free recall and recognition, operationalizing the former as a less sensitive measure than the latter. Accordingly, we measured ad recognition based on the answers to four yes/no questions. We added up the number of correct answers to calculate ad recognition scores. For ad recall, we asked participants to provide one keyword that they remembered from the ads, such as a brand name or slogan. We scored relevant keywords as 1 and irrelevant responses as 0.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Regarding invasiveness, we defined the floating ad as highly invasive and the banner ad as less invasive. Similarly, we categorized the advertisements based on whether they included sexual imagery. The checks indicated that we successfully manipulated ad invasiveness (F value = 8.482, df = 1, 462, p < .01). Cohen (Citation1988) provided general guidelines for evaluating the magnitudes of effect sizes, including eta squared in an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Based on these guidelines, we determined the effect size of the ad format on perceptions of invasiveness to have been moderate (η2 = .06). Importantly, the participants assigned to the floating type condition reported greater invasiveness (M = 13.92) than those in the banner type condition (M = 12.88).

We also successfully manipulated sex appeal in ads (F value = 311.805, df = 1, 462, p < .001). Moreover, the effect size of sex appeal in ads was significant (η2 = .40). As expected, the participants rated the ads featuring sexual imagery as more sexually appealing (M = 13.16) than the ads without sexual imagery (M = 9.06).

Ad Avoidance

Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b) predicted the main effects of ad format (pop-up compared with banner) and ad content (sexually appealing compared with not sexually appealing) on the likelihood of ad avoidance. Consistent with hypothesis 1(a), the ad format had a statistically significant main effect on ad avoidance (F value = 5.924, df = 1, 462, p < .01; η2 = .013), as shown in . Thus, the participants engaged in avoidance more frequently in response to the floating ad (M = 12.93) than the banner ad (M = 12.40). The invasiveness of the ads correlated with the participants’ desire to avoid them. The results did not, however, support hypothesis 1(b) (F value = 3.630, df = 1, 462, p = .057; η2 = .009) at the .05 probability level, meaning that there was no main effect of sexuality content on ad avoidance. Thus, contrary to our prediction, ads without sexual imagery were associated with marginally greater ad avoidance than ads that featured sexual images (M without s = 12.87, M with s = 12.45).

Table 2. Analysis of variance results for ad avoidance.

Hypothesis 2 tested the interaction effect of ad format and ad content on ad avoidance. ANOVA results indicated no interaction effect. Thus, hypothesis 2 was rejected (F value = 1.044, df = 1, 462, p = n.s., η2 = .010).

Ad Memory

Hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b) predicted a negative effect of pop-up and sexually provocative ads on media consumers’ ad memory, respectively. In particular, we anticipated that consumers exposed to a floating ad would have lower means for ad memory than those exposed to a banner ad per hypothesis 3(a). In addition, we predicted that an ad with a sexual image would generate less persistent ad memory than an ad without a sexual image per hypothesis 3(b). We used two variables, ad recognition and ad recall, to measure ad memory. We conducted a MANOVA to examine hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b) (). Though we found main effects of both ad content (F value = 13.742, df = 2, 459, p < .001) and ad format (F value = 5.185, df = 2, 459, p < .01) on the participants’ ad memory, the experimental data did not fully support hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b) because we also observed a significant interaction effect of ad format and ad content on ad memory (Wilks’s lambda = .980, F value = 4.624, p < .05; η2 = .020).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of the effects (ad memory) on ad format and ad content.

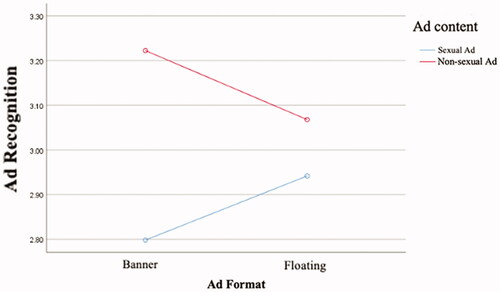

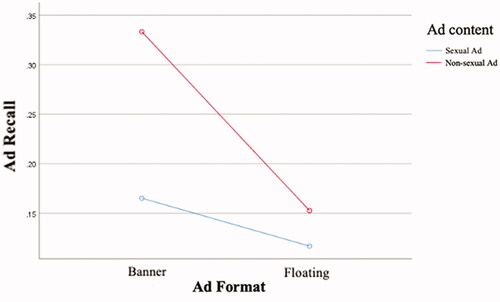

Hypothesis 4 predicted the interaction effect of ad content and ad format; to test this hypothesis, we conducted ANOVAs for ad recognition and ad recall (). In terms of ad recognition, we found a significant interaction effect of ad format and ad content (F value = 4.850, df = 1, 460, p < .05, η2 = .010). In addition, the main effect of ad content was significant (F value = 16.539, df = 1, 460, p < .001, η2 = .035), though the results did not show the main effect of ad format (F value = .007, df = 1, 460, n.s.). On the other hand, the interaction of ad format and ad content had no significant effect on ad recall (F value = 3.398, df = 1, 460, p = .066, η2 = .007). Consistent with hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b), we found significant main effects of ad format (F value = 10.200, df = 1, 460, p < .01, η2 = .022) and ad content (F value = 8.082, df = 1, 460, p < .01, η2 = .017) on ad recall.

Table 4. Analysis of variance results for ad recognition and ad recall.

The results also showed () that ads with sexual imagery (M = 2.80) affected the participants’ ad recognition more negatively than ads without sexual imagery (M = 3.22), but only in the case of the banner ad (mean difference = .44, p < .001). We found no significant difference in this regard between ads with and without sexual images in the floating format.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for Ad recognition and Ad recall.

and illustrate the interaction effects of ad format and ad content on ad recognition and ad recall, respectively. In sum, the experimental data supported hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b) only when we measured ad memory using ad recall.

Discussion

As the ability of various media to reach consumers has increased, so have consumers’ efforts to escape intrusive commercial information. We designed this study to test the assumption that consumers of news respond to pop-up advertisements and advertisements containing sexual imagery with more strenuous avoidance efforts compared with banner advertisements and advertisements without sexual imagery. We further hypothesized that these differences in format and the presence of sexual content would have similar effects on consumers’ memories of the advertisements. Accordingly, we conducted an experiment in which we exposed consumers of mobile news to ads while they read news articles online.

We found that pop-up advertisements did, indeed, elicit greater ad avoidance than banner ads, per hypothesis 1(a). This result has significant implications for marketers, as it calls into question the current orthodoxy that pop-up ads fulfill advertisers’ strategic desires to increase the exposure of products to consumers better than banner ads. In practice, advertisers’ desires are at odds with consumers’ hostility toward unexpected intrusive advertisements that hinder their information processing. Thus, exposure to intrusive advertising could lead to a general tendency on the part of consumers to avoid advertisements (Cho and Cheon Citation2004). However, the recent development of algorithms that utilize big data has raised expectations regarding new advertising techniques that leverage personalized and customized information so as to circumvent consumers’ efforts to avoid advertisements through such measures as paying fees for ad-blocking services.

The results did not, however, support hypothesis 1(b), for we observed no main effect of sexual imagery on ad avoidance. Unexpectedly, ads without such imagery elicited marginally greater ad avoidance than those with it. In attempting to account for this finding, we note first that, as the previous discussion of ad avoidance indicates, the presence or absence of sexual imagery may not, after all, influence consumers’ avoidance behaviors significantly. Moreover, though the treatment verification was successful, the image that we used as a treatment for this study may not have been sufficiently provocative to elicit reluctance among consumers who are constantly bombarded with sexually appealing advertisements in online environments (Bizwire Citation2016). If this interpretation is accurate, additional research could establish the external validity of the findings presented here regarding the role of sexual imagery in ad avoidance.

Our finding of significant main effects of ad format and ad content on consumers’ ad recall supported hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b). That is, the participants exposed to the banner advertisements recalled the content better than those exposed to the floating advertisements. Likewise, the participants exposed to the ads without sexual imagery recalled the ads better than those exposed to the ads with sexual imagery. The interaction of ad format and ad content had no significant effect on ad recall.

Our finding that media consumers had more difficulty recalling pop-up advertisements than banner advertisements is contrary to advertisers’ preference for the former over the latter. There is little evidence available relating the number of ad clicks directly to purchases, but researchers have shown that pop-up ads tend to generate more clicks than banner ads (Bae and Park Citation2018), and it is this latter tendency that has fostered advertisers’ preference in this regard: They value the short-term outcome of clicks on their advertisements more highly than consumers’ recall of the content therein. Nevertheless, because an increase in the number of ad clicks (including accidental ones) in the process of ad avoidance on one hand and the purchase behaviors of users who may access an ad with high purchase intention on the other are largely unrelated, advertisers need to think strategically about this issue.

In addition, our finding that the participants in our study showed better recall of the ads without sexual imagery than those with such imagery suggests that their recall of the advertised product was weak, presumably because the sexual imagery diverted their attention from the ad content. In the final analysis, sexual appeals may exert an initial attention effect but prove less effective with regard to recall because of their distracting nature, suggesting further that sexual imagery does not usually entice consumers to purchase advertised products or services.

Beyond the simple main effect analysis, we found an interaction effect in ad recognition. That is, while we found no significant differences in the participants’ responses to the floating advertisements based on sexual imagery, the banner ads without such imagery scored higher in ad recognition than the ads with it. These results suggest that consumers engage in more cognitive information processing when exposed to banner ads than when exposed to floating ads. More specifically, the finding that banner advertisements elicited lower recognition in the sexual image condition than floating advertisements suggests that banner ads tend to achieve much higher recognition than floating ads in the absence of sexual content.

These results suggest further that sexual advertisements activate news consumers’ reactance especially when they are unexpected. Information processing is, of course, limited by cognitive capacity (Lang Citation2000), and sexually provocative advertisements may arouse emotional responses (Lang et al. Citation1993). Thus, consumers could perceive such advertisements as unethical and offensive (LaTour and Henthorne Citation1994; Tai Citation1999), as well as contributing to clutter (Cho and Cheon Citation2004). In addition, because consumers of online news are goal oriented (You et al. Citation2013) they may tend to perceive as impediments any stimuli deemed irrelevant to their information-gathering goals. Also, when consumers encounter an article associated with a banner advertisement (a low-intrusive condition), they may skip any specifically sexual content and proceed directly with their information processing, whereas they may pause for a moment to consider nonsexual advertising content.

From a theoretical perspective, our finding that pop-up ads and ads with sexual content elicited ad avoidance and hindered recall of the content of ads is consistent with reactance theory. The participants in our study seem to have perceived that ad intrusiveness threatened their freedom to pursue their information-gathering goals in that the pop-up ads obscure the news content, resulting in frustration when consuming information online and, again, ad avoidance. Our results obtained in a mobile environment thus broaden the range of reactance theory and corroborate the finding by Youn and Kim (Citation2019) of a negative association between ad intrusiveness and ad avoidance on Facebook.

This study is not, of course, without limitations. First of all, we did not take into account the participants’ emotions toward intrusive or sexually appealing advertisements, though emotions triggered by such ads could mediate or moderate the observed association between the independent and dependent variables. In addition, in terms of sexually appealing ads, our use of two different brands as stimuli for the sexually appealing and nonsexual conditions was intended to mimic a real-world mobile advertisement setting for the sake of ecological validity, but future researchers could bolster the experimental rigor of such experiments by using the same brand for the two advertised products. Also, we focused on the mobile environment without considering the desktop environment, though resource-intensive information consumption that entails resource-intensive goals would be better suited to the latter than the former (Donner and Walton Citation2013) because of the relative screen and font sizes (Dunaway and Soroka Citation2021), which is a limitation that experiments comparing platform settings with the same news and advertising content could address. Finally, previous studies of sexually appealing advertisements have tended to concentrate on the recall of the brand and the content of the ads (Bushman Citation2005; Parker and Furnham Citation2007; Reichert and Alvaro Citation2001; Wirtz, Sparks, and Zimbres Citation2018). While we considered only ad memory in mobile news contexts, future studies could look for an association between brand memory and the information-processing styles and goals of the consumers of mobile news.

The implications of this study are significant. In particular, our results indicate that marketers should keep in mind the potential for intrusive advertisements to stimulate reactance behaviors and hinder consumers’ memories of the content of advertisements. The findings presented here deserve consideration during efforts to develop practical guidelines for advertising in mobile environments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joseph Yoo

Joseph Yoo (PhD, The University of Texas at Austin) is an assistant professor in the Communication and Information Science Department, University of Wisconsin–Green Bay.

DooHee Lee

DooHee Lee (MA, Kyung Hee University) is a PhD candidate in the Department of Media, Kyung Hee University.

Jongmin Park

Jongmin Park (PhD, The University of Missouri) is a professor in the Department of Media, Kyung Hee University.

References

- Amazeen, M. A. 2021. “Native Advertising in a Mobile Era: Effects of Ability and Motivation on Recognition in Digital News Contexts.” Digital Journalism 9 (1): 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1860783.

- Bae, S. D., and D. H. Park. 2018. “The Effect of Mobile Advertising Platform through Big Data Analytics: Focusing on Advertising and Media Characteristics.” Journal of Intelligence and Information Systems 24 (2): 37–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.13088/JIIS.2018.24.2.037.

- Barry, T. E., and D. J. Howard. 1990. “A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 9 (2): 121–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1990.11107138.

- Bettman, J. R., and C. W. Park. 1980. “Effects of Prior Knowledge and Experience and Phase of the Choice Process on Consumer Decision Processes: A Protocol Analysis.” Journal of Consumer Research 7 (3): 234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/208812.

- Bizwire. 2016. Internet Ads With Sexual Imagery at a Critical Level: Survey. http://koreabizwire.com/internet-ads-with-sexual-imagery-at-a-critical-levelsurvey/65968?platform=hootsuite.

- Brehm, J. W. 1966. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Brinson, N. H., M. S. Eastin, and V. J. Cicchirillo. 2018. “Reactance to Personalization: Understanding the Drivers behind the Growth of Ad Blocking.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 18 (2): 136–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1491350.

- Brotto, L. A., M. A. Yule, and B. B. Gorzalka. 2015. “Asexuality: An Extreme Variant of Sexual Desire Disorder?” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 12 (3): 646–660. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12806.

- Bushman, B. J. 2005. “Violence and Sex in Television Programs Do Not Sell Products in Advertisements.” Psychological Science 16 (9): 702–708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01599.x.

- Cho, Chang, and Hoan Cheon. 2004. “Why Do People Avoid Advertisements on the Internet.” Journal of Advertising 33 (4): 89–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2004.10639175.

- Clee, M. A., and R. A. Wicklund. 1980. “Consumer Behavior and Psychological Reactance.” Journal of Consumer Research 6 (4): 389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/208782.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Coursey, D. 2001. “Commentary: Pop-Up Ads are Driving Me Nuts! How About You?” ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/commentary-pop-up-ads-are-driving-me-nuts-how-about-you/.

- Danaher, P. J., and G. W. Mullarkey. 2003. “Factors Affecting Online Advertising Recall: A Study of Students.” Journal of Advertising Research 43 (3): 252–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-43-3-252-267.

- Diao, F., and S. S. Sundar. 2004. “Orienting Response and Memory for Web Advertisements.” Communication Research 31 (5): 537–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650204267932.

- Donner, J., and M. Walton. 2013. “Your Phone Has Internet—Why Are You at a Library PC? Re-Imagining Public Access in the Mobile Internet Era.” Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2013:347–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-40483-2_25.

- Dunaway, J., and S. Soroka. 2021. “Smartphone-Size Screens Constrain Cognitive Access to Video News Stories.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (1): 69–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1631367.

- Edwards, S. M., H. Li, and J.-H. Lee. 2002. “Forced Exposure and Psychological Reactance: Antecedents and Consequences of the Perceived Intrusiveness of Pop-up Ads.” Journal of Advertising 31 (3): 83–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673678.

- Estrada-Jiménez, J.,. J. Parra-Arnau, A. Rodríguez-Hoyos, and J. Forné. 2017. “Online Advertising: Analysis of Privacy Threats and Protection Approaches.” Computer Communications 100:32–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2016.12.016.

- Gardner, L., and G. Leshner. 2016. “The Role of Narrative and Other-Referencing in Attenuating Psychological Reactance to Diabetes Self-Care Messages.” Health Communication 31 (6): 738–751. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.993498.

- Goldfarb, A., and C. Tucker. 2011. “Online Display Advertising: Targeting and Obtrusiveness.” Marketing Science 30 (3): 389–404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1100.0583.

- Hannah, T. E., E. R. Hannah, and B. Wattie. 1975. “Arousal of Psychological Reactance as a Consequence of Predicting an Individual’s Behaviour.” Psychological Reports 37 (2): 411–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1975.37.2.411.

- Interworks. 2019. Interworks Media introduction. https://cdn.interworksmedia.co.kr/interview/interworksMedia.pdf.

- Jung, Y. 2011. “Understanding the Role of Sense of Presence and Perceived Autonomy in Users’ Continued Use of Social Virtual Worlds.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 16 (4): 492–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01540.x.

- Kim, S., T. R. Levine, and M. Allen. 2017. “The Intertwined Model of Reactance for Resistance and Persuasive Boomerang.” Communication Research 44 (7): 931–951. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214548575.

- Lang, A. 2000. “The Limited Capacity Model of Mediated Message Processing.” Journal of Communication 50 (1): 46–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x.

- Lang, P., M. Greenwald, M. Bradley, and A. Hamm. 1993. “Looking at Pictures: Affective, Facial, Visceral, and Behavioral Reactions.” Psychophysiology 30 (3): 261–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03352.x.

- LaTour, M. S., and T. L. Henthorne. 1994. “Female Nudity in Advertisements, Arousal and Response: A Parsimonious Extension.” Psychological Reports 75 (3 Pt 2): 1683–1690. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1994.75.3f.1683.

- Lavidge, R. J., and G. A. Steiner. 2000. “A Model for Predictive Measurements of Advertising Effectiveness.” Advertising & Society Review 1 (1): 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/asr.2000.0008.

- Lee, J. P., and J. Lyu. 2005. “A Study of Advertising Avoidance in Internet: Level of Advertising Avoidance and Predictors of Advertising Avoidance.” The Korean Journal of Advertising 16 (1): 203–223.

- Li, H., S. M. Edwards, and J. Lee. 2002. “Measuring the Intrusiveness of Advertisements: Scale Development and Validation.” Journal of Advertising 31 (2): 37–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673665.

- Lim, J. 2011. “First-Level and Second-Level Intermedia Agenda-Setting among Major News Websites.” Asian Journal of Communication 21 (2): 167–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2010.539300.

- Liu, F., H. Cheng, and J. Li. 2009. “Consumer Responses to Sex Appeal Advertising: A Cross‐Cultural Study.” International Marketing Review 26 (4/5): 501–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330910972002.

- Lombardot, É. 2007. “Nudity in Advertising: What Influence on Attention-Getting and Brand Recall?” Recherche et Applications en Marketing 22 (4): 23–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/205157070702200401.

- McCoy, S., A. Everard, D. F. Galletta, and G. D. Moody. 2017. “Here we Go Again! the Impact of Website Ad Repetition on Recall, Intrusiveness, Attitudes, and Site Revisit Intentions.” Information & Management 54 (1): 14–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.03.005.

- Metzger, M. J., A. J. Flanagin, and R. B. Medders. 2010. “Social and Heuristic Approaches to Credibility Evaluation Online.” Journal of Communication 60 (3): 413–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01488.x.

- Morimoto, M., and S. Chang. 2006. “Consumers’ Attitudes toward Unsolicited Commercial e-Mail and Postal Direct Mail Marketing Methods.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 7 (1): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2006.10722121.

- Newman, N.,. R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. Levy, and R. Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018. http://media.digitalnewsreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/digital-news-report-2018.pdf.

- Parker, E., and A. Furnham. 2007. “Does Sex Sell? The Effect of Sexual Programme Content on the Recall of Sexual and Non-Sexual Advertisements.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 21 (9): 1217–1228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1325.

- Reichert, T. 2002. “Sex in Advertising Research: A Review of Content, Effects, and Functions of Sexual Information in Consumer Advertising.” Annual Review of Sex Research 13:241–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.2002.10559806.

- Reichert, T. 2003. “The Prevalence of Sexual Imagery in Ads Targeted to Young Adults.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 37 (2): 403–412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2003.tb00460.x.

- Reichert, T., and E. Alvaro. 2001. “The Effects of Sexual Information on Ad and Brand Processing and Recall.” Southwestern Mass Communication Journal 17:9–17.

- Reichert, T., S. E. Heckler, and S. Jackson. 2001. “The Effects of Sexual Social Marketing Appeals on Cognitive Processing and Persuasion.” Journal of Advertising 30 (1): 13–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2001.10673628.

- Reid, L. N., and L. C. Soley. 1983. “Decorative Models and the Readership of Magazine Ads.” Journal of Advertising Research 23 (2): 27–32.

- Richmond, D., and T. P. Hartman. 1982. “Sex Appeal in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising Research 22 (5): 53–60.

- Riedel, A. S., C. S. Weeks, and A. T. Beatson. 2018. “Am I Intruding? Developing a Conceptualisation of Advertising Intrusiveness.” Journal of Marketing Management 34 (9–10): 750–774. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1496130.

- Samson, L. 2018. “The Effectiveness of Using Sexual Appeals in Advertising.” Journal of Media Psychology 30 (4): 184–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000194.

- Shimp, T. 2007. Advertising, Promotion, and Supplemented Aspects of Integrated Marketing Communications (7th ed.). Ohio: Thomson South-Western.

- Speck, P. S., and M. T. Elliott. 1997. “Predictors of Advertising Avoidance in Print and Broadcast Media.” Journal of Advertising 26 (3): 61–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1997.10673529.

- Steadman, M. 1969. “How Sexy Illustrations Affect Brand Recall.” Journal of Advertising Research 9 (1): 15–19.

- Tai, H. S. 1999. “Advertisement Ethics: The Use of Sexual Appeal in Chinese Advertisement.” Teaching Business Ethics 3 (1): 87–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009840623567.

- Tourangeau, R., and K. A. Rasinski. 1988. “Cognitive Processes Underlying Context Effects in Attitude Measurement.” Psychological Bulletin 103 (3): 299–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.299.

- Tulving, E. 1979. “Relations between Encoding Specificity and Levels of Processing.” In Levels of Processing in Human Memory (1st ed.), edited by L. S. Cermark & F. I. Craik, 405–428. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- van Doorn, J., and J. C. Hoekstra. 2013. “Customization of Online Advertising: The Role of Intrusiveness.” Marketing Letters 24 (4): 339–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-012-9222-1.

- Wirtz, J. G., J. V. Sparks, and T. M. Zimbres. 2018. “The Effect of Exposure to Sexual Appeals in Advertisements on Memory, Attitude, and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analytic Review.” International Journal of Advertising 37 (2): 168–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1334996.

- You, K. H., S. A. Lee, J. K. Lee, and H. Kang. 2013. “Why Read Online News? The Structural Relationships among Motivations, Behaviors, and Consumption in South Korea.” Information, Communication & Society 16 (10): 1574–1595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.724435.

- Youn, S., and S. Kim. 2019. “Understanding Ad Avoidance on Facebook: Antecedents and Outcomes of Psychological Reactance.” Computers in Human Behavior 98:232–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.025.

- Zanna, M. P., J. M. Olson, and R. H. Fazio. 1981. “Self-Perception and Attitude-Behavior Consistency.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 7 (2): 252–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014616728172011.