Abstract

Background: Despite the progress in HIV care, adherence to follow up remains critical. Disengagement impairs the benefit of HIV care and the increasing number of data that associates failed retention with worse outcomes has led public health institutions to consider retention in care as a new tool to fight against HIV pandemic.

Objective: The aim of this retrospective, observational study was to estimate the burden of disengagement and reengagement in care in our HIV cohort and to identify the characteristics of our LTFU and reengaged patients. Moreover, we build our cascade of care to explore how closely our center aligned with the “90–90–90” targets.

Methods: From the local electronic database we extracted all HIV-infected patients with at least one contact with HIV Clinic between 2012 and 2018 excluding deceased and transferred patients.

Our definition of LTFU was based on the lack of any visit during at least 1 year after the last visit. Patients re-engaged were defined as those firstly considered as LTFU patients who subsequently were newly linked to HIV care.

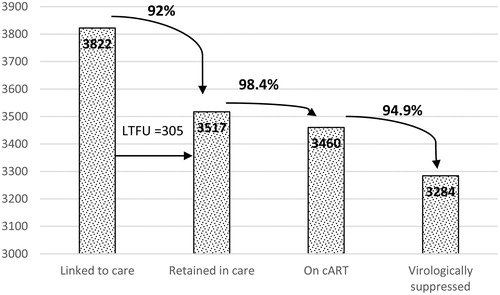

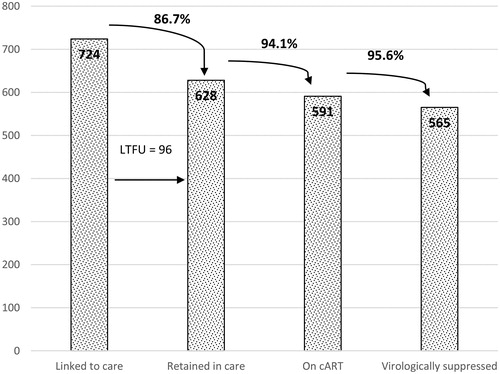

Results: About 8% of patients were lost to follow up during the period of study, with a rate of less than 2% per year and 14.1% of them were re-engaged in care. The cascade of care shows, among HIV cases diagnosed between 2011 and 2018, 86.7% patients retained in care, 94.1% of whom were on cART and 95.6% of whom were virologically suppressed.

A higher attrition was found among infections diagnosed since 2011 than before 2011, such as women, patients coming from foreign countries and those with poor virological control.

Conclusions: The retention rate found in our cohort is high and is in accordance with the 90–90–90 strategy. Nevertheless, understanding disengagement and re-engagement determinants is important to strengthen retention in care in the most fragile population.

Introduction

At the end of the nineties, the introduction of cART (combined antiretroviral therapy) led to improved survival in HIV-infected patients and decreased AIDS events.Citation1 cART is a lifelong treatment and retention in care is neither guaranteed nor easy to monitor. Loss to follow up (LTFU) impairs the benefit of early and effective HIV care whereas people living with HIV (PLHIV) with suppressed plasma HIV RNA are unlikely to contribute to HIV transmission with overall public health benefit.

The increasing number of studies that associate a failed retention with a worse outcome, including virological failure and increased mortalityCitation2–4 has led public health institutions to consider retention in care as a new and attractive tool to fight against the HIV pandemic.Citation5,Citation6

The “90–90–90” strategy promoted by UNAIDS is calling for a scaling up of HIV cascade of care to 90% of PLHIV diagnosed, 90% linked to cART and 90% of those patients that adhere to treatment achieving stable viral suppression.Citation5

The World Health Organization has included the HIV control project in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), calling health systems around the world to pursue the ambitious endpoint of successfully ending the HIV pandemic.Citation6 To reach these goals, enormous health service scale-up is needed focusing on community services such as community based (e.g. in schools, workplaces, religious institutions and by mobile services) HIV testing, education, and prevention. Treatment is to be offered promptly after diagnosis and support and monitoring of people on antiretroviral drugs is fundamental. With the same aim, the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) organized a meeting in 2016 on HIV standard of care proposing active tracing of LTFU patients by phone calls, text messages and inquiries in other services, health facilities or clinics to close monitoring the retention in care.Citation7

Nevertheless, no standard definition of retention in care exists. Usually, patients who regularly attend clinical assessments, lab exams and cART collection as scheduled by the internal or national protocols are defined as retained in care. Only recently, International HIV care guidelines have started to focus on retention in care but precise tools to evaluate this endpoint are still lacking.

In Europe, the proportion of LTFU patients in HIV clinical cohorts ranges from 13 to 19%.Citation8,Citation9 Retention in care in Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland has been estimated to be around 98% whereas data from Belgium and Ireland are slightly below, with retention rate around 89–92%.Citation10–14

These studies are widely heterogeneous in term of HIV care protocols, assessments’ frequency and retention in care definition than, the possibility to compare the estimates is limited.

In Italy, data on LTFU patients are scarce, probably due to the lack of a national database and the few published single center studies reported a dropped out rate of 12–33%.Citation15–18

Most Italian cohort studies identified foreign born people and intravenous drug users (IVDU) being most likely at risk of LTFU mainly for three reasons: socio-economic barriers, little awareness of infection risk, high mobility.Citation15,Citation19–21

The major bias of the data available consists in the definition of “retention in care” since some studies consider as retained who had one visit at least every 6 months and others every 12 months or other intervals.

Moreover, the term “lost to follow up” represents a catch-all that includes not only patients dropped out from HIV care but also self-transfers and undocumented deaths. This might underestimate the proportion of deaths and, by contrast, overestimate the LTFU rate.

In addition, there is a small rate of re-engaged patients after LTFU, but studies focused on those patients are lacking, despite patients who dropped out and later present again at HIV care could be severely immunosuppressed and then, they probably account for a high burden of AIDS morbidity and mortality.

Here, as recommended during last HIV conference in Glasgow,Citation22 we tried to accurately estimate the burden of disengagement and reengagement in care in our HIV cohort and to identify the characteristics of these patients, to tailor future targeted interventions that could improve retention in care of our HIV infected patients.

Finally we build our cascade of care to explore how closely our tertiary referral service aligned with the “90–90–90” targets.

Methods

The present retrospective, observational study was conducted at the University Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases of the Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale (ASST) Spedali Civili in Brescia, Northern Italy. The Spedali Civili General Hospital in Brescia is one of the largest hospitals in Italy, and it is also the reference hospital for the School of Medicine, University of Brescia. It represents the only tertiary referral center of infectious disease and HIV care of the Brescia province (about 1,200,000 inhabitants). We extracted the medical records from the clinical database of all HIV-infected patients with at least one contact with our Clinic between 2012 and 2018. We recorded age, gender, origin country, declared risk factor for HIV acquisition, HBV or HCV co-infection, cART, AIDS events, year of HIV diagnosis and of linkage to our Clinic and the day of last contact. CD4+ T-cells absolute count and HIV RNA load were collected at the time of diagnosis and at last contact. Virologic suppression was defined as HIV RNA <37 copies/ml according to our lab threshold (Siemens Versant HIV-1 RNA 1.5 Assay).

We excluded from the cohort those who died or moved to another center. The life status of all patients was determined on the basis of national mortality registry and they were defined as transferred when they moved to another center (verified by the presence of a letter to or from the other HIV Clinic) before or during the study period.

The observation period lasted from January 2012 to April 2018. We enrolled two cohorts of patients according to calendar year of HIV diagnosis a) since 2011 (“new” cases) and b) before 2011 (“old” cases). We included among the new cases all the patients with confirmed HIV diagnosis from 2011 until April 2017 to have at least 12 months of follow up to evaluate their retention in care during the observation period.

Our definition of LTFU (or dropped out) patients was based on the lack of any visit, lab exam or cART collection during at least 12 months after the last visit, between January 1, 2012 and April 30, 2018 for patients in care. By contrast, retention in care was considered as a regular access to HIV outpatient Clinic to collect cART and to perform blood exams and clinical assessment during an interval of 12 months.

Patients re-engaged were defined as those firstly considered as lost to follow up who subsequently were newly linked to HIV care (at least one clinical evaluation and laboratory test). CD4+ T-cells count, HIV RNA and AIDS events were recorded at time of re-engagement.

We constructed two cascades of care that included the following stages: 1) linkage to care, consisting in patients with at least one attendance to HIV Clinic, 2) prescription of cART to patients linked to care (at least two dispensations of cART every two months) and 3) viral suppression, defined by the most recent HIV RNA <37 copies/ml in patients linked to care and on cART.

The first cascade of care included only new HIV diagnosed patients (since 2011) during the observation (2012–2018) period and it was called “cascade of care”. The second one was referred to “old cases” (diagnosed before 2011) and we called it “continuum of care” because, compared to new diagnosis, we didn’t know exactly their clinical history before 2012.

Statistical analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the cohort. Categorical variables were described as frequencies and quantitative variables were expressed as mean, SD and range. The comparisons of means and proportions between LTFU patients with old and those with new HIV diagnosis were performed using the t-test and the chi-square, respectively, with a threshold of 0.05 for refusing the null hypothesis. All the computations were carried out using the STATA program for personal computer, version 14.0 (STATA Statistics/Data Analysis 12.0 – STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study population

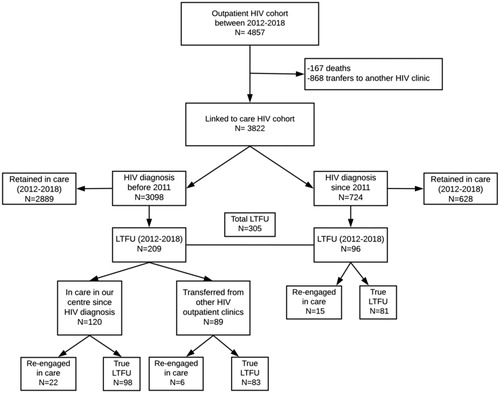

From a total of 11,493 HIV positive patients recorded in our departmental database from 1998, we extracted 4,857 patients who had at least one contact with our Outpatients Clinic between January 2012 to April 2018 (), including both HIV infected patients with old HIV diagnosis (before 2011) and those with new HIV diagnosis (since 2011). Among them, 167 patients died (3.4%) and 868 were transferred to another center for continuing the HIV care (17.9%). Old and new diagnosis accounted for 81.1% (n = 3098) and 18.9% (n = 724) of the HIV infected patients linked to care respectively.

Figure 1 Flow chart of patients in the HIV cohort, linked to care and with loss to follow-up (LTFU).

Among the 3,822 patients linked to care, the mean age was 50.1 years (±9.8) with 71.8% of patients in the range 41–60 years. 28.3% were females and almost half (42%) declared heterosexual HIV transmission risk. 85.1% of patients has CD4+ T-cells >350/µl (). Foreign people represented 18.3% of PLHIV and 7.1% of them had not regular identification documents (illegal migrants). 98.2% of patients were on cART, and 93.3% had undetectable HIV RNA.

Table 1 Characteristics of HIV patients with at least one visit between 2012 and 2018 (HIV cohort)

HIV cohort LTFU

The LTFU patients in the period of study (lack of any contact with the HIV Clinic during the follow-up for at least 12 months) were 209/3098 (6.7%) among old cases and 96/724 (13.3%) among new cases, providing a total of 305/3822 (8%) LTFU patients in our cohort. As shown in this proportion was stable under 2% per year, without significant variations in the study period.

Table 2 Distribution Number of HIV patients in follow-up and with new diagnosis and number and percentage of those with loss to follow-up (LTFU) of LTFU by observation year (2012–2018)

The proportion of LTFU patients was significantly higher among patients with new opposed to old diagnosis (13.3% vs 6.7%, p < 0.05).

The characteristics of those LTFU are described in . The mean age among LTFU patients was 40 years, with 38.1% women, and approximately half of them were Italians and declared heterosexual intercourses as risk factor for HIV acquisition.

Table 3 Characteristics of patients with loss to follow-up (LTFU): all (n = 305), old diagnosis (n = 209) or new diagnosis (n = 96) at the time of loss to follow up

In HIV cohort, women are 28.3% of PLHIV whereas they are significantly more represented among LTFU population (p < 0.0001). At the time of last contact, 85.6% (261/305) of patients were regularly on cART, the median CD4+ T-cells count was 549 cells/µl (85% had >200 CD4+ T-cells/µl) and HIV-RNA was undetectable in 159 (53.5%) patients. AIDS-defining events were reported in 16.1% of patients during their HIV infection history.

LTFU patients among new HIV diagnosis

A total of 760 patients were diagnosed with HIV in our Clinic since 2011. During the study period, 16 patients died and 20 were transferred. Among the remaining 724 individuals, 96 were LTFU (13.3%), representing the 31.4% (96/305) of the total LTFU patients in the study period.

None of them had had a previous contact with another HIV Clinic before. Three of them were LTFU just after a positive screening test, without undergoing further analysis (none of them was re-engaged in care later). Only 70 (73%) had started cART when they were lost to follow up. The median interval between diagnosis and last contact was 13 months (range 0–58 months). See for additional data.

LTFU patients among old HIV diagnosis

3,098/3,822 HIV infected patients received HIV diagnosis before 2011. Among them, 209 (6.7%) were LTFU between 2012 and 2018. The mean age was 42 years, 35.4% of them were females, and 44.5% were of foreign origin. Most of them (91.4%) were on cART and 56% had undetectable HIV RNA, when LTFU occurred.

More than half (57.4%) of them had been in care in our hospital since HIV diagnosis, with a median follow-up time of 82 months (range 16–367 months). On the other hand, 42.5% (89/209) arrived to our outpatient Clinic after receiving primary HIV care elsewhere, with a median time of follow-up after diagnosis of 158 months (we could not assess compliance before transfer). Their median follow-up in our Clinic was 17 months (range 0–226 months).

Comparing LTFU patients with old and those with new HIV diagnosis, LTFU with new diagnosis were younger (37 vs 42 years, p < 0.001), mainly non-Italians (65.6% vs 44.5%, p < 0.001), they referred in higher proportion heterosexual intercourses as risk factor (64.6% vs 40.7%, p < 0.001) and in a lower proportion intravenous drug use (7.3% vs 29.2%, p < 0.001). Among new cases we found fewer viro-suppressed patients (41.7% vs 56%, p < 0.05).

Considering together LTFU patients with new and old diagnosis who initiated the follow-up in our Clinic during the study period, almost half of them, (89/185 individuals, 48.1%) were loss to follow-up during the first year after linkage to our Clinic for HIV care (median time of follow-up of 100 days).

The number of cases with new diagnosis and the rate of LTFU by year (between 2011 and 2018) is shown in .

Re-engaged in care patients

During the study period, 22 patients with old HIV diagnosis and regularly followed by our hospital, 6 with old HIV diagnosis but initially followed in another center and 15 with new HIV diagnosis were re-engaged in care in our Clinic, proving a total of 43 LTFU patients re-engaged in care (14.1%) (). They missed visits for a median time of 28 months before re-engagement (range 12–67 months).

Among the 43 re-engaged patients, approximately half were Italians and heterosexual males, 81.4% were on cART at last contact, only 39.5% of patients had more than 200 CD4+ T-cells/µl at re-engagement with a median CD4+ T-cells count of 119.5 cells/µl, median viral load was >10,000 copies/ml (). The mean interval between the last contact and re-engagement was 28 months (range 12–67). Among these patients, 9 (20.9%) returned in care because of an AIDS event: six cases of P. jiroveci pneumonia associated in two cases with CMV disseminated disease, one disseminated CMV disease, one disseminated CMV disease associated with HIV-related encephalitis and disseminated mycobacteriosis, one neurotoxoplasmosis. 7 re-engaged patients (16.3% 7/43) had been previously diagnosed with another AIDS event before LTFU.

Table 4 Characteristics of LTFU patients re-engaged in care in comparison with LTFU patients

Continuum and cascade of care during 2012–2018

As regards the continuum of care, a total of 3517 of the 3822 patients (92%) linked to care between 2012 and 2018 were retained in care, 98.4% of whom were currently on cART and 94.9% were virologically suppressed (73.9% had viral load 0 copies/ml). See .

The “cascade of care” among the 724 patients with new HIV diagnosis during the study period showed that the patients retained in care were 86.7% (628/724), 94.1% of them (591/628) were regularly on cART, 95.6% of which (565/591) were virologically suppressed. See .

Discussion

Despite the progress in HIV care, therapies, survival perspectives and quality of life, some patients still drop out of HIV care and are lost to follow-up. In our study, LTFU patients were a small proportion of PLHIV (about 2% per year) and 14.1% of them were newly re-engaged in care after a mean of 2 years, mainly because of a serious immunological deterioration and/or clinical HIV progression.

Patients with recent HIV diagnosis, women and foreign people, mainly of African origin represent a population with high attrition rate.

We have also measured the effectiveness of the local HIV care in leading new HIV patients from diagnosis to viral suppression from 2012 to 2018. The cascade of care shows a rate of retention in care of 86.7%, and, among patients retained in care, more than 94% are regularly on cART and virologically suppressed (considering 37 copies/ml as cut off) .

A higher likelihood of disengagement among PLHIV during the first years after diagnosis has been previously described as well as the greater adherence to visit schedule is reported among older and more experienced patients.Citation2,Citation3,Citation23–25 Our findings show the same trends and they may reflect the level of HIV infection knowledge/acceptance among patients.

Our Clinic receives patients from a large province of nearly 1,200,000 inhabitants and this area is characterized by a significant flow of immigrants from countries with high prevalence of HIV.Citation26

In this context, the incidence of HIV infection is estimated to be one of the highest in Italy, 6.7/100,000 compared to 5.7/100,000 in the whole country.Citation27 From a public health perspective it is important to measure and improve retention in care to reduce HIV circulation and, consequently, occurrence of new cases.

In the present study, as in a couple of other reportsCitation9,Citation14 we accurately excluded from those LTFU, deceased patients and those transferred to other centers. By contrast, most Italian and European studies on this issue reported an unadjusted proportion of LTFU patients, which includes deceased and transferred individuals.Citation8,Citation10–13,Citation15–20

Conversely, the mortality rate recorded (3.4%) is similar to published dataCitation28,Citation29 and the number of patients with a documented transfer to another HIV Clinic was quite high (17.9%), but in line with other studies which carefully traced transferred patients.Citation9,Citation14

Migrants represent 51.1% of total LTFU patients and 65.6% of those LTFU with new diagnosis. Despite the fact that in Italy all immigrants, even if they are illegal, have free access to complete HIV care, including cART, the legal procedure is long, complex and foreign people are afraid of being reported as illegals or as HIV infected.Citation30 Undocumented migrants and IVDUs are fragile populations, susceptible to forced movement and with several socio-economic barriers.Citation14,Citation19,Citation21,Citation31–33 They are well-recognized as patients with low adherence to screening programs, low retention in care, low cART compliance, and consequently, reduced survival.Citation34–37 The relatively high proportion of foreign patients (18.3%) and IVDU (28.3%) in our HIV population could explain the remarkable number of LTFU patients and those transferred.

To strengthen our hypothesis of migrants’ mobility, between 2016 and 2017 in Brescia province the proportion of foreign inhabitants has decreased by 3.1% in metropolitan area and by 3.9% in the province, probably because of the economic crisis.Citation38

Our study has identified women as another fragile population. Women represent 28.3% of patients in our HIV cohort but their proportion reaches 38.1% among those LTFU (about half are of African origin, data not shown) and this number further increases among LTFU patients with new diagnoses (43.7%). Women are known to be underrepresented in HIV cohortsCitation39 and HIV diagnosis embodies a stigma difficult to overcome, mainly in African population.Citation40

As regards immuno-virological status of those LTFU, around 50% of them had a detectable HIV viral load at the last contact (both in new and old HIV diagnosed patients). Poor virological control before HIV care disengagement was also reported in another Italian studyCitation15 and these data suggest that a poor compliance to cART during follow-up could finally result in a definitive HIV care attrition.

We found some differences between LTFU patients with new and old HIV diagnoses during the study period. The rate of those LTFU was significantly higher in the former group and these patients were younger and mainly originate from foreign countries. By contrast, patients with old HIV diagnosis have largely passed the first year of linkage in care, that seems to be the more critical period for the retention and, as expected, they showed a higher rate of retention in care (92%) with more than 90% of patients on cART and with virological suppression.

Among new HIV diagnoses, only 73% had started cART when lost to follow up. Indeed, although it is recommended to start cART as soon as possible after diagnosis, some laboratory tests are usually needed before therapy prescription and patients are asked to certify their infection at a health care center to perform free of charge exams and both procedures need some time.Citation30

As recently demonstrated by several studies conducted in areas with high prevalence of HIV, the “test and treat strategy”, that consists in offering cART the same day of a positive HIV screening, appears to significantly increase linkage to care and HIV viral suppression.Citation41–43

Our data emphasize the need to detect populations at high risk of HIV care attrition and to implement effective retention tools. In our context, a simplification of bureaucratic procedures required to access HIV care and cART prescription, a more targeted counseling about the benefits of a regular follow up and an active tracing of LTFU patients might help the retention in care.

We also focused our study on reengagement in care which has been investigated by little researches, so far,Citation44,Citation45 whereas we found that they represent a not negligible proportion of LTFU patients (14.1%) and more than 20% of them presents again because of an AIDS event. The interval between the last contact and re-engagement was long, more than 2 years, and this prolonged break accounts for clinical and immunological deterioration and for possible HIV transmission.

Our study has several limitations. First, it describes a single center cohort over a 6-year period, thus, our findings might not be generalizable to other cohorts. Nevertheless, our HIV population belong to a national network, the Italian MASTER cohort,Citation18 and patients characteristics are roughly comparable. The Italian MASTER cohort is a hospital-based multicenter, open, dynamic HIV cohort which was set up to investigate mid and long-term clinical outcomes, the impact of therapeutic strategies and public health issues with a total of 24,672 HIV-infected patients from the eight Italian hospitals enrolled. Second, we have not measured the first stage of the cascade of care aimed to estimate undiagnosed HIV cases. Recently, by using surveillance data, it was estimated that there are about 12,000–18,000 people in Italy with undiagnosed HIV, corresponding to 11–13% of the overall population with HIV.Citation46 Third, the absence of data on outmigration and legal status of migrants presents a challenge in clearly understanding how many of them remain in the country without accessing care or if they moved abroad. Finally, we cannot be completely sure that patients who declared to transfer to another HIV Clinic were continuing cART and follow up.

Despite these limitations the present study has also strengths. We described the cascade of care of new HIV diagnosis and the longitudinal continuum of care of PLHIV with old diagnosis during the same period showing that a different performance of the two cascades exists. Moreover, this is one of the first studies comparing characteristics of LTFU patients with a recent diagnosis and those with an old one. Furthermore, the relatively large number of cases with new HIV diagnosis and the exclusion of deaths and transferred patients from those with LTFU provided more precise estimates than other ItalianCitation15 or EuropeanCitation8,Citation14 monocentric cohorts. Finally, we used a cut off of 37 copies/ml for the third goal of UNAIDS cascade of care, lower than most of published data, enabling us to deeper evaluate adherence to cART.

In conclusion, this study shows a very low rate of LTFU patients in our province. This population includes mainly new diagnosed HIV patients that are LTFU during the first year after diagnosis. HIV care cascade and longitudinal continuum of care offer useful information to ameliorate HIV care program quality. Furthermore, these findings highlight the importance of improving HIV counseling during the first year, with a focus on women, migrants, intravenous drug users and people who do not reach HIV undetectability to provide correct treatment and care to all PLHIV and reduce the virus transmission.

Finally, a focused study on the time to start cART maybe crucial to understand the real benefit of the “same day start” compared to the usual standard of care on retention in care.

To conclude, understanding patterns and determinants of both disengagement and reengagement in care and the role of migration is important to strengthen retention of individuals within the HIV care pathway.

Authors’ contribution

A.C., E.Q.R., I.I., and F.D. contributed to study design, analysis, and data interpretation. A.C. and E.Q.R. first drafted the article. E.Q.R., I.I., E.F., C.P., and A.C. contributed to data collection. E.Q.R. and F.C. contributed to critical reviewing of the article. All authors reviewed the article, read and approved the final article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who contributed to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Agnese Comelli

Agnese Comelli is a resident in infectious disease at University Department of Spedali Civili in Brescia since 2016. She received her degree in medicine and surgery at University of Pavia in July 2015. At the moment she is employed in HIV outpatient clinic and she works with particular focus on HIV care, migrant health and tropical diseases.

Ilaria Izzo

Ilaria Izzo is a medical doctor with expertise in infectious disease and HIV care. Besides receiving her MD degree from University of Brescia, she received her diploma in infectious diseases there, in 2011. She authored 31 publications in international peer-reviewed journals, mainly focusing on HIV infection.

Francesco Donato

Francesco Donato received his MD degree and also received his diplomas in hygiene, preventive medicine, and medical statistic in Milan. Currently, he is professor of medicine (Public Health) at University of Brescia. He authored more than 400 publications in international peer-reviewed journals and 15 scientific book chapters.

Anna Celotti

Anna Celotti is a resident in infectious disease at University Department of Spedali Civili in Brescia, Italy, since 2015. She received her degree in medicine and surgery at University of Naples in 2014. At the moment she is employed in viral hepatitis outpatient clinic but she works with particular focus on HIV care.

Emanuele Focà

Emanuele Focà is a medical doctor and a researcher at University of Brescia. He received his MD degree from University of Messina in 2005 and he specialized in infectious diseases at University of Brescia in 2010. He is one of the teachers of infectious diseases course at University of Brescia. He authored 65 publications in international peer-reviewed journals, mainly focusing on HIV infections. He currently works in HIV outpatient clinic at Spedali Civili General Hospital in Brescia.

Chiara Pezzoli

Maria Chiara Pezzoli is a medical doctor with expertise in infectious disease and HIV care. Besides receiving her MD degree from University of Brescia, she received her diploma in infectious diseases there, in 2004. She authored 19 publications in international peer-reviewed journals, mainly focusing on HIV infections.

Francesco Castelli

Francesco Castelli is a professor received his MD degree from University of Pavia, he received his diplomas in infectious diseases there, and a diploma in tropical medicine at the University of Milan. Currently he is professor of medicine (infectious diseases), director of the Department for Mother-and-Child Care and Medical Biotechnology and director of the Post-Graduate School in Tropical Medicine. He also is head of the 32-bed University Division of Infectious Diseases and of the 8-bed Tropical Unit at the Spedali Civili General Hospital in Brescia. And he has authored 337 publications in international peer-reviewed journals, mainly focusing on HIV infections and parasitic and tropical diseases. In addition, he has authored 175 articles in Italian journals or conference proceedings, contributed to over 300 abstracts for Italian and international congresses, written 91 chapters in books and manuals, and edited an Italian-language book on infectious and tropical diseases. He has been involved as an expert and manager in numerous long and short EU and WHO projects in dozens of African, Asian, and Latin American countries, many involving malaria, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection.

Eugenia Quiros-Roldan

Eugenia Quiros-Roldan is a professor received her MD degree from University of Granada in 1987 and in Brescia she specialized in Infectious diseases in 2001. Currently she is professor of medicine (infectious diseases) at University of Brescia. Professor Quiros-Roldan authored 240 publications in international peer-reviewed journals, mainly focusing on HIV infections. She currently works in HIV outpatient clinic at Spedali Civili General Hospital in Brescia.

References

- Mocroft A, Vella S, Benfield TL, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1725–1730.

- Mugavero MJ, Lin H-Y, Willig JH, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(2):248–256.

- Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(1):41–49.

- Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: What can we do? Top HIV Med. 2008;16:156–161.

- 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/90-90-90. Published 2014. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication. Published 2015. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- De Wit S, Battegay M, D’Arminio Monforte A, et al. European AIDS Clinical Society Second Standard of Care Meeting, Brussels 16–17 November 2016: A summary. HIV Med. 2017;19(2):77–80.

- Ndiaye B, Ould K, Salleron J, et al. Incidence rate and risk factors for loss to follow-up in HIV-infected patients from five French clinical centres in Northern France – January 1997 to December 2006. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:567–575.

- Jose S, Delpech V, Howarth A, et al. A continuum of HIV care describing mortality and loss to follow-up: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(6):e301–e308.

- Gisslén M, Svedhem V, Lindborg L, et al. Sweden, the first country to achieve the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)/World Health Organization (WHO) 90-90-90 continuum of HIV care targets. HIV Med. 2017;18(4):305–307.

- Helleberg M, Engsig FN, Kronborg G, et al. Retention in a public healthcare system with free access to treatment: A Danish nationwide HIV cohort study. AIDS. 2012;26(6):741–748.

- Kohler P, Schmidt AJ, Cavassini M, et al. The HIV care cascade in Switzerland: Reaching the UNAIDS/WHO targets for patients diagnosed with HIV. AIDS. 2015;29(18):2509–2515.

- Institut scientifique de Santé publique (WIV-ISP). Epidémiologie du SIDA et de l’infection à VIH en Belgique. Situation au 31 décembre 2016. https://epidemio.wiv-isp.be/ID/Pages/Publications.aspx. Published 2016. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- Mcgettrick P, Ghavami-Kia B, Tinago W, et al. The HIV care cascade and sub-analysis of those linked to but not retained in care: The experience from a tertiary HIV referral service in Dublin. HIV Clin Trials. 2017;18(3):93–99.

- Prinapori R, Giannini B, Riccardi N, et al. Predictors of retention in care in HIV-infected patients in a large hospital cohort in Italy. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(5):606–611.

- Lazzaretti C, Borghi V, Franceschini E, Guaraldi G, Mussini C. Engagement and retention in care of patients diagnosed with HIV infection and enrolled in the Modena HIV Surveillance Cohort. In: Elev Int Congr Drug Ther HIV Infect. International AIDS Society; November 2012; Glasgow, UK [P105].

- Fusco FM, Scappaticci L, Navarra A, et al. Factors determining the Retention in Care in 798 persons living with HIV newly diagnosed at National Institute for Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani”, Rome, in 2005–2011: A retrospective cohort study. In: Ital Conf AIDS Retrovirus. 2014; Rome, Italy [OC25].

- Torti C, Raffetti E, Donato F, et al. Cohort Profile: Standardized Management of Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort (MASTER Cohort). Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):e12(1–10).

- Saracino A, Tartaglia A, Trillo G, et al. Late presentation and loss to follow-up of immigrants newly diagnosed with HIV in the HAART era. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(4):751–755.

- Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Korthuis PT, Gebo KA, and for the HIV Research Network. Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(3):249–259.

- Thierfelder C, Weber R, Elzi L, et al. Participation, characteristics and retention rates of HIV-positive immigrants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2012;13(2):118–126.

- Burns F. Retention and re-engagement in care: a combination approach again required. In: Fourteenth Int Congr Drug Ther HIV Infect. International AIDS Society; November 2018 Glasgow, UK [O111].

- Mugavero MJ, Davila JA, Nevin CR, Giordano TP. From access to engagement: measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(10):607–613.

- Lee H, Wu XK, Genberg BL, et al. Beyond binary retention in HIV care: predictors of the dynamic processes of patient engagement, disengagement, and re-entry into care in a US clinical cohort. AIDS. 2018;32:2217–2225

- Althoff KN, Justice AC, Gange SJ, et al. Virologic and immunologic response to HAART, by age and regimen class. AIDS. 2010;24(16):2469–2479.

- Camoni L, Salfa MC, Regine V, et al. HIV incidence estimate among non-nationals in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(11):813–817.

- Regine V., Pugliese L., Boros S., Santaquilani M., Ferri M. Aggiornamento delle nuove diagnosi di infezione da HIV e dei casi di AIDS in Italia al 31 Dicembre 2016. Not dell’Istituto Super di sanità. 2017;30(Supplemento 1):9.

- Raffetti E, Postorino MC, Castelli F, et al. The risk of late or advanced presentation of HIV infected patients is still high, associated factors evolve but impact on overall mortality is vanishing over calendar years: Results from the Italian MASTER Cohort. BMC Public Health; 2016;16(1):878.

- Trickey A, May MT, Vehreschild J-J, et al. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e349–e356.

- Luzi AM, Pugliese L., Schwarz M. Access to treatment for immigrant: practical indications. Not dell’Istituto Super di sanità. 2015;28(Supplemento 1):11.

- Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Vandormael A, Dobra A. HIV treatment cascade in migrants and mobile populations. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015;10(6):430–438.

- Gabrielli C., Schiaroli E., De Socio G., Papalini C., Pasticci M.B., Baldelli F. Retention in care of HIV-positive patients from 2005 to 2014: comparison between Italian and non-Italian patients. In: Ital Conf AIDS Retrovirus. 2018; Rome Italy [P106].

- Kinoshita M, Oka S. Migrant patients living with HIV/AIDS in Japan: Review of factors associated with high dropout rate in a leading medical institution in Japan. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):1–12.

- Abgrall S, del Amo J. Effect of sociodemographic factors on survival of people living with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(5):501–506.

- Migrants Working Group on behalf of COHERE in EuroCoord. Mortality in migrants living with HIV in western Europe (1997–2013): a collaborative cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(12):e540–e549.

- The Socio-economic Inequalities and HIV Writing Group for Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research in Europe (COHERE) in EuroCoord. Delayed HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy: inequalities by educational level, COHERE in EuroCoord. AIDS. 2014;28:2297–2306.

- Saracino A, Zaccarelli M, Lorenzini P, et al. Impact of social determinants on antiretroviral therapy access and outcomes entering the era of universal treatment for people living with HIV in Italy. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–12.

- Colombo M. Immigrazione e contesti locali. In: Annuario CIRMib 2017. Brescia: Vita e Pensiero; 2017. 348 pp.

- Curno MJ, Rossi S, Hodges-Mameletzis I, Johnston R, Price MA, Heidari S. A systematic review of the inclusion (or exclusion) of women in HIV research: From clinical studies of antiretrovirals and vaccines to cure strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(2):181–188.

- Lekas H-M, Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. Continuities and discontinuities in the experiences of felt and enacted stigma among women with HIV/AIDS. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(9):1165–1190.

- Labhardt ND, Ringera I, Lejone TI, et al. Effect of offering same-day ART vs usual health facility referral during home-based HIV testing on linkage to care and viral suppression among adults with HIV in Lesotho: The CASCADE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1103–1112.

- Nguyen HH, Bui DD, Dinh TTT, et al. A prospective “test-and-treat” demonstration project among people who inject drugs in Vietnam. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(7):1–9.

- Ongwandee S, Lertpiriyasuwat C, Khawcharoenporn T, et al. Implementation of a test, treat, and prevent HIV program among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Thailand, 2015–2016. PLoS One; 2018;13(7):e0201171.

- Connors WJ, Krentz HB, Gill MJ. Healthcare contacts among patients lost to follow-up in HIV care: Review of a large regional cohort utilizing electronic health records. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(13):1275–1281.

- Udeagu C-CN, Shah S, Misra K, Sepkowitz KA, Braunstein SL. Where are they now? Assessing if persons returned to HIV care following loss to follow-up by public health case workers were engaged in care in follow-up years. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(5):181–190.

- Mammone A, Pezzotti P, Regine V, et al. How many people are living with undiagnosed HIV infection? An estimate for Italy, based on surveillance data. AIDS. 2016;30(7):1131–1136.