Abstract

Classic street-level bureaucracy literature has suggested that individual bureaucrats are shaped by their work group. Work group colleagues can impact how bureaucrats perceive clients and how they behave toward them. Building on theories of work group socialization, social representation, and social identification, we investigate if and how the attitude of individual street-level bureaucrats toward clients is shaped by the client-attitude of the bureaucrat’s work group colleagues. We also test whether this relation is dependent on conditions of attitudinal homogeneity and perceived cohesion of the work group. Results of a survey among street-level bureaucrats in the Dutch and Belgian tax administration (1245 respondents from 210 work groups) suggest that different mechanisms underlie the work group’s impact on the individual street-level bureaucrat in this specific attitude. The analysis furthermore reveals that work groups have a limited impact on the individual’s client-attitude. Theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

Street-level bureaucracies are largely bound by formal bureaucratic rules and regulations (Lipsky, Citation2010). Yet looking at small units of people within these bureaucracies reveals “patterns of activities and interactions that cannot be accounted for by the official structure” (Blau, Citation1956, p. 53; Moreland & Levine, Citation2006). These patterns result from normative standards that are constructed at the work group level and enforced on its group members (Blau, Citation1956; Barker, Citation1993; Wright & Barker, Citation2000). Such patterns can be so strong that it has led scholars like Herbert Simon (Citation1997) to hypothesize the existence of a “group mind.”

In his seminal work, Wilson (Citation1989, p. 33) claimed that “to understand a government bureaucracy one must understand how its front-line workers learn what to do.” What distinguishes these so-called street-level bureaucrats from other government workers is the ample discretion they exercise over their work (Henderson, Țiclău, & Balica, Citation2018; Zacka, Citation2017). Their discretion allows street-level bureaucrats’ personal attitudes and preferences to permeate and bias public service delivery (Keiser, Citation2010; Lipsky, Citation2010). As a result, understanding government bureaucracies require insight into how the personal dispositions that guide street-level bureaucrats in their professional operations come into being (Oberfield, Citation2014; Zacka, Citation2017).

The idea that work groups shape individuals in their attitudes and behaviors is now commonly accepted (e.g., Bettenhausen, Citation1991; Feldman, Citation1981; Moreland & Levine, Citation2006). At the frontlines, the work group level is crucial to unraveling how street-level modes of practice come into being (Foldy & Buckley, Citation2010). Although calls to include the work group in street-level bureaucracy research have been loudly voiced (Foldy & Buckley, Citation2010), this field still displays a tendency to focus on the individual bureaucrat or organizational-level influences (e.g., Gofen, Sella, & Gassner, Citation2019; Oberfield, Citation2014, Citation2019). Furthermore, studies of frontline group dynamics tend to explore peer relations in the social or professional network of the individual street-level bureaucrat (e.g., Maroulis, Citation2017; Siciliano, Citation2017; Zacka, Citation2017). This narrow focus neglects the boundaries the formal structure of the work group may impose on these spheres of influence (Foldy & Buckley, Citation2010; Moreland & Levine, Citation2006; Wright & Barker, Citation2000; Miller & Rice, Citation1967).

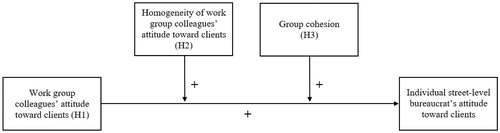

Building on a sample of Dutch and Belgian street-level tax administrators, this study examines how the work group affects a core attitude that informs street-level bureaucrats’ judgments and subsequent actions: their attitude toward clients (Baviskar & Winter, Citation2017; Keulemans & Groeneveld, Citation2019; Keulemans & Van de Walle, Citation2018; Lipsky, Citation2010; Oberfield, Citation2014). Drawing from theories on work group socialization, we explore the association between the client-attitudes held by one’s work group colleagues and the individual bureaucrat. Informed by theories of social representation and social identification, we expect this relation to be dependent on conditions of attitudinal homogeneity and group cohesion. As social representation theory posits that groups can differ in the uniformity with which patterns of thought are shared (Moscovici, Citation1988), we expect greater pressure on individuals to conform their client-attitude to that of their work group if one’s colleagues display attitudinal homogeneity. Group cohesion triggers a sense of social identification with the group that pressures the individual to conform to that group (Levi, Citation2011), leading us to speculate a stronger attitudinal link between the individual bureaucrat and her work group for cohesive work groups.

This paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we discuss the interrelations of discretion, attitudes, and work groups. We then develop a theoretical framework for work group influence and elaborate on the hypotheses of this study. After a description of the study sample, measures, and methods, the results are presented. We end with a discussion of the results, study limitations, and implications for the understanding of street-level practice and theory, as well as suggestions for future research.

Discretion, attitudes, and the work group

Street-level bureaucrats exercise wide discretion that opens up avenues for their personal preferences to protrude their work (e.g., Keulemans & Groeneveld, Citation2019; Lipsky, Citation2010; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2003; Zacka, Citation2017). Their attitude toward clients is a critical personal disposition that facilitates client-processing requirements and serves as a coping response to the strenuous job demands street-level bureaucrats face (Baviskar & Winter, Citation2017; Kallio, Blomberg, & Kroll, Citation2013; Lipsky, Citation2010).

As attitudes affect how we process information (Maio & Haddock, Citation2015), street-level bureaucrats’ client-attitude can bias public service delivery (Keiser, Citation2010). For instance, Kroeger (Citation1975) revealed that client-oriented street-level bureaucrats granted more benefits to clients than agency-oriented workers did. And Baviskar and Winter (Citation2017) found a stronger reliance on coping behaviors among street-level bureaucrats with an aversive attitude to clients. Stone (Citation1981, p. 45) suggested that a punitive outlook on clients is more common among bureaucrats with a “condemnatory moralistic view of clients.” Lastly, Keulemans and Van de Walle (Citation2018) forward that street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients forms an abstract disposition that guides more concrete client-categorizations that center on clients’ “worthiness,” “need,” or “deservingness” (Kroeger, Citation1975; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2003).

Scholarship on attitude formation and change predominantly build on studies of social influences and social context (e.g., Ottati, Edwards, & Krumdick, Citation2005). Groups provide a social context in which individuals express and merge their views, giving rise to group attitudes and altering individual members in the process (Ottati et al., Citation2005, pp. 724–725). Work groups form a pivotal social context in the organizational setting (Blair-Loy & Wharton, Citation2002). This suggests that studying the social spheres of influence in work groups is critical to understanding how the work group affects street-level bureaucrats in their attitude toward clients. In the next section, we construct a conceptual framework for work group influence.

Work group socialization and the “group mind”

Socialization theory is dominated by a focus on organizational socialization (Moreland & Levine, Citation2006). Organizational socialization is the process through which individuals acquire the attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge required to become successful members of an organization (Morrison, Citation1993; Van Maanen & Schein, Citation1979). Although socialization studies tend to focus on the organizational socialization of individuals (e.g., Oberfield, Citation2014; Wanberg, Citation2012), multiple scholars forward the critical role of work groups in socialization processes (e.g., Feldman, Citation1981; Barker, Citation1993; Wright & Barker, Citation2000; Moreland & Levine, Citation2006).

Work groups are organizational units that are “part of the organization’s hierarchical system;” led by “supervisors or managers who control the decision-making process;” whose “group members typically work on independent tasks that are linked by the supervisors or work system” (Levi, Citation2011, p. 7). Moreland and Levine (Citation2006, p. 480) attribute the importance of work group socialization to individuals’ stronger commitment to the work group. Moreover, individuals primarily interact with direct colleagues. This provides the work group with greater opportunities to control members. Also, individuals who do not adjust to the work group risk rejection by the other members, making them more prone to failing their task requirements. Consequential to their dominant position, work groups can dictate which attitudes and behaviors they expect from their members (Feldman, Citation1981; Miller & Rice, Citation1967; Morrison, Citation1993), more so than the organization (Moreland & Levine, Citation2006).

Knowledge of how these spheres of influences unfold at the frontlines is particularly scarce (Foldy & Buckley, Citation2010; Gofen, Citation2014). However, early studies of bureaucracy suggest that normative standards emerge at the work group level which are then enforced by the group (Blau, Citation1956, Citation1960). In his seminal works, Blau (Citation1956, pp. 55–56) concluded that nonconformity to work group norms could lead to ostracization and exclusion, providing the work group with a powerful tool to attitudinal assimilation since “the extremely disagreeable experience of feeling isolated while witnessing the solidarity of others constitutes a powerful incentive to abandon deviant practices lest this temporary state become a permanent one.” And in his 1960 inquiry of street-level bureaucrats’ orientation to clients, Blau found the work group to be a dominant factor in shaping individual bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients: more tenured bureaucrats generally had less considerate attitudes toward clients than their less seasoned group members did. These more tenured bureaucrats were often dominant work group members. Their dominant position put pressure on less tenured group members to also express anti-client sentiments in order to become accepted and integrated members of the work group (Blau, Citation1960, p. 357). This work is exemplary for how processes at the work group level can pressure individual bureaucrats into attitudinal adjustment to the work group.

Contemporary insights from related areas of research suggest that Blau’s conclusions still hold today. For instance, Sandfort (Citation2000) illustrates how social processes give rise to collectively held knowledge and beliefs among street-level bureaucrats. Gofen (Citation2014, p. 485) forwards that “street-level divergence may not stay on the individual level but may involve collective action that legitimizes and even encourages it,” while Maroulis (Citation2017) asserts that street-level bureaucrats rely on their subgroup of peers for social and emotional support. And Zacka (Citation2017, p. 187) elaborates that “peers observe, assess, and question each other’s perception of incoming clients, and […] intervene to shape the dispositional states that undergird such perception.” Although these inquiries do not take the boundaries of the work group into account, they subscribe to the idea that collective schemas arise among groups of street-level bureaucrats.

Summarizing, the socialization process equips street-level bureaucrats with what they need to function as bureaucrats (Oberfield, Citation2014); more in particular, their attitudes toward their clients and ways of behaving toward them. Socialization pressures at the work group level entice individual street-level bureaucrats to adjust their attitude toward clients to the client-attitude held by their work group colleagues. This expectation results in the first hypothesis of this paper:

H1: Individual bureaucrats whose work group colleagues have a more positive attitude toward clients are more likely to have a positive attitude toward clients themselves.

If we find evidence for mechanisms of attitudinal assimilation of the individual bureaucrat to the work group, it might indicate the existence of a group mind. A group mind refers to a group level mental state that is shared by its members and determines how information is represented in the minds of individual group members (Klimoski & Mohammed, Citation1994). In this paper, we focus on two group-defining processes that might bring about a group mind: social representation and social identification.

Social representation theory

Social representations “concern the contents of everyday thinking and the stock of ideas that gives coherence to our religious beliefs, political ideas and the connections we create” (Moscovici, Citation1988, p. 214). These contents are constructed through a process of collective meaning-making (Höijer, Citation2011). Consequently, social representations reflect perceptions of reality as they are shared by a group (Lahlou, Citation1996, p. 159). Attitudes are one of those elements of reality (Höijer, Citation2011).

At the frontlines, street-level bureaucrats are motivated to partake in sense-making processes with peers to reduce the uncertainty and complexity inherent to their job (Siciliano, Citation2017). According to Bruhn (Citation2009, pp. 08–09), social representations at the frontlines capture social knowledge on objects relevant to the street-level bureaucrats’ contextual setting. These representations result from the synergy of the individual bureaucrat, the group, and the practice of street-level work.

Social representations can differ in the extent to which they are collectively shared (Moscovici, Citation1988). The similarity of the schemas and beliefs held by individual group members directly impacts how a common understanding of reality emerges at the group level (Bettenhausen, Citation1991). Building on these insights, we expect that the extent to which bureaucrats’ social representations of clients are shared among work group members determines how much pressure one’s work group colleagues can impose on the individual bureaucrat to adjust her client-attitude to theirs. In other words, if a bureaucrat’s work group colleagues are not uniform in their social representation of clients, there will be no shared norm system on clients for them to pressure the individual bureaucrat to adjust her client-attitude to. That is why we expect the link between the individual bureaucrat’s attitude and that of her work group to be stronger for work groups in which the bureaucrat’s direct colleagues have a strong shared social representation of clients.

The extent to which work group members share a social representation of clients is reflected in the homogeneity of their attitudes toward clients. The more homogenous those attitudes are, the stronger the social representation that is shared by them. This brings us to the second hypothesis of this study:

H2: The relation between the individual bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients and that of their work group colleagues is stronger for bureaucrats whose work group colleagues have a more homogenous attitude toward clients.

Social identification theory

Social identity refers to “those aspects of an individual’s self-image that derive from social categories to which he perceives himself as belonging” (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986, p. 16). Although references to social identity theory are often implicit in bureaucracy scholarship, they can be found in institutional accounts of bureaucratic socialization (Oberfield, Citation2014). Social identity theory is often used as a denominator for two interlinked theories: social identity theory and self-categorization theory (Turner & Haslam, Citation2001). The emphasis of the former lies on intergroup relations; the latter is mainly concerned with in-group interpersonal relations, presenting the group as a psychological entity (Turner & Haslam, Citation2001). In this paper, both elements are addressed.

Core to social identity theory is how individuals classify themselves as belonging to different groups in society (Hogg, Citation2001). This process is referred to as social categorization (Turner & Haslam, Citation2001). A group consist of “individuals who perceive themselves to be members of the same social category, share some emotional involvement in this common definition of themselves, and achieve some degree of social consensus about the evaluation of their group and of their membership in it” (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986, p. 15). Groups derive their properties and meaning in relation to other groups (Hogg, Citation2001). This process gives rise to the notion of in-groups and out-groups (Stets & Burke, Citation2000). Categorizations of in-groups and out-groups evoke in-group bias, enabling group attitudes to emerge (Hogg, Citation2001; Turner & Haslam, Citation2001).

The main process that enables the emergence of group attitudes is that of self-categorization (Stets & Burke, Citation2000; Turner & Haslam, Citation2001). The extent to which individuals categorize themselves in terms of a social category varies along a continuum from personal identity to social identity. If self-categorization in terms of a specific social identity is dominant, individuals perceive themselves as representatives of that social category over being a unique individual (Turner & Haslam, Citation2001). Although organizations hold many social categories individuals can identify with, self-definitions in terms of the work group tend to be dominant due to group member proximity and interdependency (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989).

Group cohesion is indicative of a shared social identity among group members (Levi, Citation2011, p. 62). Cohesion is the “dynamic process that is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs” (Carron, Brawley, & Widmeyer, Citation1998, p. 213). Members of cohesive groups have been linked to efforts to seek consensus of in-group members’ views (Ottati et al., Citation2005). We view strong group cohesion as indicative of strong self-categorization in terms of work group membership.

Drawing from social identity theory, we expect a positive association between the extent to which individual bureaucrats categorize themselves in terms of their work group membership—and thus perceive their work group as cohesive—and the pressures they experience to adjust their client-attitude to that of their work group colleagues. These expectations are summarized in the third hypothesis of this study:

H3: The relation between the individual bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients and that of their work group colleagues is stronger for bureaucrats who belong to more cohesive work groups.

The three hypotheses are summarized in .

Methods

Research setting

For this study, survey data were collected among street-level tax bureaucrats who audit small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in the Dutch and Belgian tax administration. The bulk of the audits these street-level bureaucrats conduct are selected at the central level, where computerized risk-assessment models evaluate tax returns on a variety of indicators that may indicate noncompliance or fraud. Once a case is assigned to the auditors, they prepare their audit as much as possible using information on the enterprise that is available from the tax administration’s internal databases. This preparation phase serves to burden the auditee as little as possible (Belastingdienst, Citation2016). Thereafter, auditors commonly plan multiple on-site visits to audit the bookkeeping and operational practices of the enterprise. Their main task is to evaluate the acceptability of the entrepreneur’s tax return (Belastingdienst, Citation2016).

If the auditors encounter mistakes, they have to assess the intentions of the entrepreneur: are the mistakes intentional, the consequence of negligence, or plain ignorance (Raaphorst, Citation2017)? Their job can be quite individualistic in nature, but prior research has shown that case deliberations with colleagues play an important role in their work (Raaphorst, Citation2017).

These tax auditors are street-level bureaucrats in terms of Lipsky’s (Citation2010) classic work: they exercise extensive discretion and engage in face-to-face encounters with clients (Cohen & Gershgoren, Citation2016). Their decisions are made under constraints of time and resources (Cohen & Gershgoren, Citation2016) and greatly affect citizens’ lives (Raaphorst, Citation2017). Moreover, the regulatory nature of their job and the large stakes involved therein tend to amplify the street-level character of their work as these traits confront auditors with a relatively high degree of uncertainty in their professional operations (Raaphorst, Citation2017).

The Dutch and Belgian tax systems are fairly similar and the tax auditors within them perform analogous tasks. The main difference between these two administrations resided in their team make-up: Belgian work groups consisted of tax auditors. Dutch work groups also included desk auditors who lack face-to-face contact with clients. Even though these desk auditors were not invited to participate in this study, selecting administrations with a different work group composition allowed us to take task unity in work groups into account, which increased the validity of the analyses.

Both administrations experienced reorganizations in recent years. Consequently, the work group structures were relatively new at the time of data collection. In addition, most street-level tax auditors had been working for their administration for a long time, so their average organizational tenure was high. These conditions did not limit our opportunities to explore processes of work group socialization as organizational socialization is a continuous process that lasts for the duration of one’s career (Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007; Wanberg, Citation2012). Consequently, it applies to organizational newcomers and veterans alike (Ashforth et al., Citation2007). Moreover, socialization influences become particularly effective when individuals’ organizational roles change (Wanberg, Citation2012). This perspective resonates in bureaucratic socialization scholarship which tends to focus on the first 2 years of socialization processes only (e.g., Oberfield, Citation2019).

For this study, the entire population of SME tax auditors was invited to participate. They were identified using the tax administrations’ internal databases.1 As we targeted the entire population, no sampling procedure was necessary. In the Netherlands, this resulted in a sample of 2257 tax bureaucrats from 165 work groups. For Belgium, it was 2382 street-level tax bureaucrats from 172 work groups.

Data

An electronic survey was conducted in 2016. The response rate was 55.2% (n = 1245) for the Netherlands and 30.0% (n = 714) for Belgium. For the analysis, we only included those street-level tax bureaucrats who confirmed that they belonged to the sample population and had valid replies on key variables. Second, we only included respondents from work groups from which at least four tax auditors filled in the survey. This resulted in a final sample of 800 respondents for the Netherlands, from 123 work groups. For Belgium, 445 respondents from 87 work groups remained. Work group sizes varied from four to sixteen members in the Netherlands and four to nine members in Belgium. The mean sample age was 54 years in the Netherlands and 49 years in Belgium, indicative of an aging working population. Of the Belgian street-level bureaucrats, 84% had obtained a high level of education, versus 45% of the Dutch bureaucrats.

Measures

Dependent variable: street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients

We define street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients as their “summary evaluation of clients along a dimension ranging from positive to negative that is based on the street-level bureaucrats’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral information on clients” (Keulemans & Van de Walle, Citation2018, p. 5). This construct was assessed with Keulemans and Van de Walle’s (Citation2018) multicomponent model of street-level bureaucrats’ client-attitude; a measurement instrument that consists of four attitude components: the cognitive attitude component, the positive affective attitude component, the negative affective attitude component, and the behavioral attitude component.2

The cognitive component refers to the characteristics bureaucrats attribute to clients (Maio & Haddock, Citation2015). Affect refers to the emotional responses evoked in bureaucrats when they interact with clients (Breckler, Citation1984). The behavioral component refers to street-level bureaucrats’ past voluntary behaviors toward clients. These are believed to (subconsciously) communicate one’s client-attitude to the individual as individuals can infer their attitudes from past courses of action (Bem, Citation1972; Maio & Haddock, Citation2015). For the behavioral component it is critical to differentiate between behaviors that represent an attitude component and behaviors that are consequential to street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients (Keulemans & Van de Walle, Citation2018): the spectrum of potential behavioral consequences to an attitude are wide-ranging, while only behaviors with evaluative implications for the attitude object “clients” are potential attitudinal indicators (Himmelfarb, Citation1993).

For the Netherlands, a confirmatory factor analysis (performed in AMOS version 24) supported the fit of this model (CMIN/DF = 3.16, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05). For Belgium3, its fit (CMIN/DF = 3.86, CFI = 0.91, GFI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.08) was acceptable. All component measures demonstrated reliability (Field, Citation2013; ). Using the multicomponent model resulted in four separate attitude scores for each bureaucrat. All items were measured using seven-point Likert scales ranging from “never” to “always.”4

Table 1. Descriptives.

Independent variable: work group colleagues’ attitude toward clients

To compose a measure of the client-attitude held by a bureaucrat’s work group colleagues, we averaged the scores for all group members excluding the reference person, on each of the four attitude components. This resulted in a group-level score that differed for each individual work group member. For example, for a work group consisting of five members, the group score was calculated five times per component. For each individual group member, this score consisted of the average component score of the other four group members.

Moderating variables

Homogeneity of the work group colleagues’ attitude toward clients

To assess attitudinal homogeneity, we used the standard deviation of a bureaucrat’s work group colleagues’ attitude to clients—again by calculating a separate group-level score for each individual through exclusion of the reference person. This caused the homogeneity scores to also differ for each work group member. Here, a small standard deviation meant that one’s work group colleagues were homogenous in their client-attitude. These standard deviations were calculated separately for each of the attitude components.

Group cohesion

Group cohesion was assessed using the “social cohesion” and “individual attraction to the group” dimensions of Carless and De Paola’s (Citation2000) revised cohesion scale.5 Social cohesion refers to “the degree to which work group members like socializing together” (Carless & De Paola, Citation2000, p. 79). Individual attraction is “the extent to which individual work group members are attracted to the group” (ibid.).Citation Social cohesion was measured using three items (α = 0.75, 0.80, respectively).6 The individual attraction was inquired with two items (α = 0.63, 0.65, respectively). Both dimensions were measured at the individual level of analysis, using seven-point Likert scales ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree.”

Control variables

Time enables bureaucrats to learn and internalize organizational norms. Consequently, more tenured bureaucrats may be more strongly socialized into their client-attitude and organizational contexts than less tenured bureaucrats (e.g., Kallio et al., Citation2013). We controlled for two types of tenure that can differ in duration: average work group tenure and organizational tenure. If average work group tenure is short, group patterns might not yet have come into existence (e.g., Barker, Citation1993). To determine organizational tenure respondents were asked when they started working for the tax administration. Average work group tenure was assessed by averaging the self-reported work group tenure of all participating work group members.

Bureaucrats’ gender and education have been linked to street-level bureaucrats’ client-attitude and outcomes of organizational socialization (e.g., Kallio et al., Citation2013; Keulemans & Groeneveld, Citation2019; Oberfield, Citation2019). Level of education was inquired by having respondents indicate their highest completed level of education, which was recoded into low to mid-high education and high education due to a small portion of low educated street-level bureaucrats in the samples (14 and 0%, respectively). Gender categories were male and female. Lastly, as it may be indicative of different social dynamics in work groups, we controlled for the number of participating individuals from the same group.

Method of analysis

First, we assessed the descriptives and bivariate correlations of the study measures. Second, we addressed the issue of common method variance (CMV) using Harman’s one-factor test and the unmeasured latent method factor technique. Lastly, the hypotheses of this study were tested through a set of hierarchical multiple regressions (blockwise entry). In this type of regression, blocks of variables are entered in a predetermined order that is grounded in theoretical expectations on their respective contributions (Field, Citation2013). Even though we focus on work groups, we refrained from a multilevel analysis as the group context multilevel analyses serve to include was targeted by the main predictor of this study.

Three models were estimated for each attitude component, using SPSS version 25. First, we assessed the effects of the control variables. Second, we added the predictors of this study to explore their direct effects on street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients. Inquiring the relation of the work group’s client-attitude and that held by the individual enabled us to test hypothesis 1. Lastly, the moderation from homogeneity and group cohesion was added to test hypotheses 2 and 3. As our analyses included interaction effects all non-binary variables were mean-centered (Field, Citation2013). Since a cross-country comparison was not the purpose of this study, we treated the two tax administrations as separate cases and reported them accordingly.

Findings

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and common method variance

displays the descriptive statistics of the study variables. They show that street-level bureaucrats held a fairly positive attitude to clients: they often associated clients with positive attributes and clients regularly evoked positive affect in them. They rarely experienced client-induced negative affect and often displayed positive behaviors toward them on a voluntary basis. Across and within the two administrations street-level bureaucrats were relatively homogenous in their attitude to clients. They did not have a strong sense of group cohesion. The bivariate correlations provided in and show relatively weak associations between the variables of interest.

Table 2. Pearson’s Correlations, Dutch Tax Administration (n = 780).

Table 3. Pearson’s Correlations, Belgian Tax Administration (n = 427).

Building on survey data can result in a common source bias that may produce biased estimates (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Citation2012). We first reduced the risk of CMV by having different actors, that is, street-level bureaucrats and their colleagues, provide the data for the main predictor and dependent variables. Second, CMV was assessed using two tests. Harman’s one-factor test was performed on the cohesion measures and the dependent variables as these measures relied on survey responses provided by the same individual (Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986). The extracted factor accounted for a small portion of the total variance only (13.1 and 12.6%, respectively). Second, we controlled for CMV using the unmeasured latent method factor technique (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012), performed in AMOS. The common variance was low (0 and 2.3%, respectively). Both tests indicate that CMV was not substantial in this study.

Regressions

and present the findings of the hierarchical multiple regressions. Robust standard errors were obtained using the bootstrap procedure in SPSS.7 Columns 1, 4, 7, and 10 of these tables indicate that some control variables affected street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients in a similar way across both administrations. It shows that women were more likely to hold client-induced negative affect than men (β = 0.106, 0.216, p < 0.01, respectively). Also, higher educated street-level bureaucrats were less likely to display positive behaviors to clients than their less-educated colleagues (β = −0.170, −0.126, p < 0.01, p < 0.05, respectively).

Table 4. Hierarchical Regressions, Dutch Tax Administration (n = 742).

Table 5. Hierarchical Regressions, Belgian Tax Administration (n = 404).

Hypothesis 1 stated that individual bureaucrats whose work group colleagues have a more positive attitude toward clients are more likely to have a positive attitude toward clients themselves. After controlling for the effects of tenure, gender, education, and group size, columns 2, 5, 8, and 11 show that this hypothesis holds for the positive component of this attitude only (β = 0.065, 0.273, p < 0.10, p < 0.01, respectively). It shows that clients were more likely to induce positive affect in street-level bureaucrats when their work group colleagues held these sentiments more often. This positive association was stronger in the Belgian administration. In the Dutch sample, we additionally found a negative association between the street-level bureaucrat and work group colleagues’ negative affect (β = −0.060, p < 0.05). It shows a tendency to diverge from the work group: individual bureaucrats were less likely to experience client-induced negative affect when their colleagues experienced these sentiments with a higher frequency. Based on these findings, hypothesis 1 cannot be confirmed.

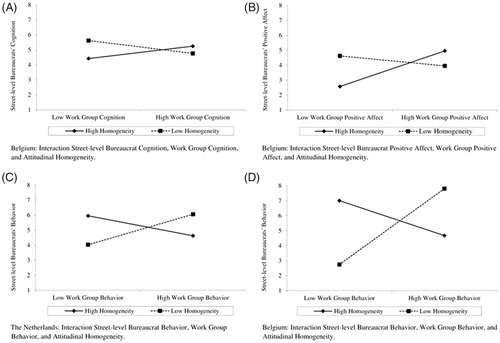

Hypothesis 2 predicted that attitudinal homogeneity moderates the association between the attitude toward clients held by street-level bureaucrats and their work group colleagues. Interpreting columns 3, 6, 9, and 12 of and , evidence supporting this hypothesis was only found in the Belgian sample, for the cognitive and positive affective attitude component (β = −0.075, −0.113, p < 0.10, p < 0.05, respectively). These effects are plotted in . In this figure, low values represent minimum values. High values represent maximum values. and show that street-level bureaucrats from homogeneous work groups were more likely to attribute positive traits to clients and experience positive affect toward clients when their work group colleagues held such positive cognitions and positive affect with a higher frequency, and vice versa.

Figure 2. Interaction effects between street-level bureaucrats’ client-attitude, the work group colleagues’ client-attitude, and attitudinal homogeneity.

For the behavioral attitude component, we found a positive moderation effect of attitudinal homogeneity in both administrations (β = 0.077, 0.199, p < 0.10, p < 0.01, respectively). As and illustrate, these effects go against hypothesis 2: homogeneity in client-oriented behaviors among one’s work group colleagues incentivized individual street-level bureaucrats to diverge from the behaviors of their group. Again, this association was stronger for the Belgian administration. These mixed findings lead us to reject hypothesis 2.

Lastly, hypothesis 3 postulated that the association between the street-level bureaucrats’ and their work group colleagues’ attitude toward clients is moderated by the cohesiveness of the work group. Columns 3, 6, 9, and 12 of and provide no evidence in support of this hypothesis. It is therefore rejected.

Discussion

This paper examined if and how the work group shapes the individual street-level bureaucrat in her attitude toward clients. Grounded in theories of work group socialization, social representation, and social identification, it explored the association between the work group colleagues’ attitude to clients and that of the individual, expecting assimilation of the individual to the group attitude. It furthermore inquired whether this relation is dependent on conditions of attitudinal homogeneity and group cohesion.

Before discussing the findings of this study, some study limitations require consideration. First, this study implicitly assumed that work group members were aware of each other’s client-attitude. Second, the street-level tax bureaucrats of this study did not share responsibility for team outcomes, while this trait may foster the formation of group-level normative frameworks (e.g., Barker, Citation1993; Wright & Barker, Citation2000). Future research is invited to target a frontline setting that includes this group feature. A third limitation pertains to the generalizability of this study. The Netherlands and Belgium were selected because their tax systems are relatively similar. They gradually moved from a vertical control philosophy to a practice of horizontal control, trust, and fostering compliance among clients (e.g., Belastingdienst, Citation2016). We cannot claim the empirical generalizability of this contextual setting to other tax systems. Consequently, we welcome future studies in tax regimes that are still orientated to deterrence and vertical control. Lastly, we examined attitudinal adjustment of the individual bureaucrat to the work group, while socialization refers to the mutual adjustment of actors (Moreland & Levine, Citation2006). To unravel the directionality of these influences, future research is welcomed that builds on a longitudinal research design.

To test its hypotheses, this study distinguished between four attitude components: the cognitive, positive affective, negative affective, and behavioral component (Keulemans & Van de Walle, Citation2018). Building on this multi-component model and a sample of Dutch and Belgian street-level tax bureaucrats, we could draw three main conclusions: first, the impact of the work group on the individual bureaucrat’s attitude toward clients is limited. Second, clients are more likely to evoke a positive affect in street-level bureaucrats when their work group colleagues hold these sentiments with a higher frequency. Third, conditions of group homogeneity trigger behavioral divergence from the work group, rather than assimilation. Stronger associations between the individual and the group were found in the Belgian sample. While Belgian work groups consisted of tax auditors only, Dutch groups held individuals with diverse functionalities. This suggests that task uniformity may function as a conduit for group influence (e.g., Campbell, Citation2016).

Our expectations of attitudinal assimilation of the individual to the work group were grounded in theories of the group mind. This paper shows little evidence for the existence of this group-level mental state among frontline tax bureaucrats. A possible explanation, therefore, resides in that the group mind has predominantly been linked to cognitive factors. For instance, Klimoski and Mohammed (Citation1994, p. 404) equal team mental models to a state of socially shared cognition. And both social representation theory and social identification theory build on cognitive elements (e.g., Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989; Höijer, Citation2011). Consolidating that our findings were differentiated by the four attitude components with the cognitive foundations of the group mind suggests that mechanisms other than the group mind underlie how the work group shapes the individual bureaucrat in her attitude toward clients.

One such alternative mechanism may reside in the social and emotional support systems that emerge among frontline peers (Maroulis, Citation2017) and work groups (Feldman, Citation1981). Such systems lessen the strains of frontline work on the street-level bureaucrat (Maroulis, Citation2017). From this perspective, the positive association of the individual and work group positive affect may be indicative of a functioning emotional support system at the work group level, rather than a group mind. This system may, then, simultaneously operate to protect the individual bureaucrat against the experience of negative affect, which could account for the low negative affect among the bureaucrats in this study.

This support system could simultaneously explain the behavioral divergence sparked by group homogeneity. Hurst, Kammeyer-Mueller, and Livingston (Citation2012, p. 130) suggest that conditions of poor social support and exclusion can make individuals feel like outsiders. These conditions can cause an individual to feel dissimilar to colleagues, motivating her to display behavioral divergence (ibid.). As a result, tendencies toward behavioral divergence under conditions of group homogeneity may reflect that an individual bureaucrat is declined social support from her colleagues, while this support system is in effect for other work group members. This process seemingly represents the ostracizing process that was described by Blau (Citation1956). Given the importance these explanations attach to work group support systems, we welcome future research efforts aimed at unraveling how such support systems affect the street-level bureaucrat client-attitude.

Alternatively, deviant behaviors could result from a refusal of group norms by the individual bureaucrat (Levi, Citation2011). Even if a bureaucrat self-categorizes herself in terms of the social category of the work group, she can still disagree with the attitudes held by that group (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989) and consequently refrain from behaviors that are in accordance with these attitudes. Attitudinal homogeneity, in turn, could be indicative of a strongly enforced norm system at the work group level. If these norms reflect the extremes of the attitudinal continuum, a bureaucrat could be more likely to disagree with and thus diverge from her work group’s client-attitude. More in-depth, qualitative inquiries of bureaucrats’ self-categorizations and group level norms are needed to advance our understanding of frontline divergence from the work group.

Lastly, the street-level bureaucrats of this study displayed considerable homogeneity in their attitude toward clients, within and between work groups. This suggests that the surveyed tax administrations are holographic organizations. In holographic organizations organizational identities are adopted and shared by all organizational units, causing work groups to be alike (Moreland & Levine, Citation2006). A holographic nature, however, does not imply that institutional forces are exempt from affecting street-level attitudes. For instance, Keulemans and Groeneveld (Citation2019) found that frontline supervisors function as attitudinal role models to street-level tax bureaucrats. Consequently, a holographic nature does not direct attention away from institutional explanations of street-level attitudes. Rather, it draws attention to the homogenizing effects of extra-organizational influences, such as attraction and selection processes (Moyson, Raaphorst, Groeneveld, & Van de Walle, Citation2018).

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the modest impact of the work group on street-level bureaucrats’ attitude toward clients. The impact the work group did have on the individual was differentiated by the four attitude components of this study. This suggested that different mechanisms underlie the association between the work group and the individual bureaucrat in this specific attitude; the emotional and social support systems that may arise within these groups providing the most prominent example. Although this research specifically targeted work group level dynamics, its findings of limited impact are congruent with evidence from studies of frontline organizational socialization (Moyson et al., Citation2018; Oberfield, Citation2014, Citation2019). For instance, a recent 10-year study of police socialization alludes that the attitudes of new recruits are hardly altered by post-entry organizational forces, directing attention to dispositional and pre-entry attitudinal influences (Oberfield, Citation2019)

Our study has multiple practical implications. First, it highlights the importance of a careful selection process of new employees. If bureaucratic dispositions are predominantly formed before entering the organization, recruiters should think about who they want as organizational members. Second, it suggests that individual bureaucrats’ client-attitude need not be a factor of major consideration to those actors charged with designing the formal structures of street-level work groups. Lastly, as our study suggests that the work group’s impact on street-level bureaucrats’ client-attitude originates from the social dynamics that unfold within these groups, frontline managers seeking to steer subordinate bureaucrats in this attitude should capitalize on these dynamics. In particular, the social and emotional support systems these work groups may give rise to.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shelena Keulemans

Shelena Keulemans is an assistant professor of public administration at the Institute for Management Research, Radboud University Nijmegen. Her research interests include street-level bureaucracy, citizen-state interactions, attitudes to citizens, and social psychological dynamics in bureaucracy.

Steven Van de Walle

Steven Van de Walle is professor of public management at the Public Governance Institute, KU Leuven, Belgium. His research focuses on public sector reform, interactions between public services and clients, and attitudes and behaviors of public officials. His most recent book is ‘Inspectors and enforcement at the front line of government’ (Palgrave, 2019, ed., with Nadine Raaphorst).

Notes

1 In the Netherlands, the survey was administered in four out of five tax regions. The fifth region was not included because a pilot survey had been conducted in this region (see Keulemans & Van de Walle, Citation2018).

2 Prior research showed the affective attitude component to represent two distinctive dimensions of affect, suggesting that affective items are unipolar in nature (see Keulemans & Van de Walle, Citation2018).

3 For Belgium, two items were omitted from the negative affective component (“nervous” and “upset”). These items stem from the PANAS-scales (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Citation1988) and have been translated differently for the Dutch context and Flemish context (Engelen, De Peuter, Victoir, Van Diest, & Van den Berg, Citation2006). Out of consistency considerations the Dutch translation was used in both settings. The analysis showed that these two Dutch negative affective items did not fit the Belgian tax administration.

4 All survey items are included in Appendix A.

5 The third dimension, “task cohesion”, implies a shared responsibility for a group task (see Carless & De Paola, Citation2000). This condition does not apply to work groups of street-level tax auditors. Hence, this dimension was unsuitable for our purposes and therefore omitted.

6 An exploratory factor analysis of the cohesion items showed that the social cohesion item “our team would like to spend time together outside of work hours” had more in common with the items assessing individual attraction to the group, indicating a lack of conceptual clarity. It was therefore removed.

7 All bootstrapped estimates were based on 500 bootstrap samples.

8 The cognitive attitude items are negatively framed (see Appendix A). To facilitate their interpretation, the direction of these items was reversed in all analyses.

References

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. doi:10.2307/258189

- Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., & Harrison, S. H. (2007). Socialization in organizational contexts. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 22, pp. 1–70). Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

- Barker, J. R. (1993). Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self-managing teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(3), 408–437. doi:10.2307/2393374

- Baviskar, S., & Winter, S. C. (2017). Street-level bureaucrats as individual policymakers: The relationship between attitudes and coping behavior toward vulnerable children and youth. International Public Management Journal, 20(2), 316–338. doi:10.1080/10967494.2016.1235641

- Belastingdienst. (2016). Controleaanpak Belastingdienst (CAB): De CAB en zijn modellen toegepast in toezicht. Retrieved from https://www.belastingdienst.nl/wps/wcm/connect/bldcontentnl/themaoverstijgend/brochures_en_publicaties/controleaanpak_belastingdienst

- Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1–62). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Bettenhausen, K. L. (1991). Five years of groups research: What we have learned and what needs to be addressed. Journal of Management, 17(2), 345–381. doi:10.1177/014920639101700205

- Blair-Loy, M., & Wharton, A. S. (2002). Employees’ use of work-family policies and the workplace social context. Social Forces, 80(3), 813–845. doi:10.1353/sof.2002.0002

- Blau, P. M. (1956). Bureaucracy in modern society. New York, NY: Random House.

- Blau, P. M. (1960). Orientation toward clients in a public welfare agency. Administrative Science Quarterly, 5(3), 341–361. doi:10.2307/2390661

- Breckler, S. J. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1191–1205. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1191

- Bruhn, A. (2009). Occupational unity or diversity in a changing work context? The case of Swedish labour inspectors. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 7(2), 31–23. doi:10.1080/14774003.2009.11667733

- Campbell, J. W. (2016). A collaboration-based model of work motivation and role-ambiguity in public organizations. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(3), 655–675. doi:10.1080/15309576.2015.1137763

- Carless, S. A., & De Paola, C. (2000). The measurement of cohesion in work teams. Small Group Research, 31(1), 71–88. doi:10.1177/104649640003100104

- Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R., & Widmeyer, W. N. (1998). The measurement of cohesiveness in sport groups. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 213–226). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Cohen, N., & Gershgoren, S. (2016). The incentives of street-level bureaucrats and inequality in tax assessments. Administration & Society, 48(3), 267–289. doi:10.1177/0095399712473984

- Engelen, U., De Peuter, S., Victoir, A., Van Diest, I., & Van den Bergh, O. (2006). Verdere validering van de Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) en vergelijking van twee Nederlandstalige versies. Gedrag en Gezondheid, 34(2), 61–70.

- Feldman, D. C. (1981). The multiple socialization of organization members. Academy of Management Review, 6(2), 309–318. doi:10.5465/amr.1981.4287859

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using SPSS: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n roll (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Foldy, E. G., & Buckley, T. R. (2010). Recreating street-level practice: The role of routines, work groups, and team learning. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(1), 23–52. doi:10.1093/jopart/mun034

- Gofen, A. (2014). Mind the gap: Dimensions and influence of street-level divergence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(2), 473–493. doi:10.1093/jopart/mut037

- Gofen, A., Sella, S., & Gassner, D. (2019). Levels of analysis in street-level bureaucracy research. In P. Hupe (Ed.), Research handbook on street-level bureaucracy: The ground floor of government in context (pp. 336–350). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Henderson, A., Țiclău, T., & Balica, D. (2018). Perceptions of discretion in street-level public service: Examining administrative governance in Romania. Public Performance & Management Review, 41(3), 620–647. doi:10.1080/15309576.2017.1400987

- Himmelfarb, S. (1993). The measurement of attitudes. In A. H. Eagly & Chaiken, S. (Eds.), The psychology of attitudes (pp. 23–88). Forth Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace & Company.

- Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 184–200. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_1

- Höijer, B. (2011). Social representation theory. Nordicom Review, 32(2), 3–16. doi:10.1515/nor-2017-0109

- Hurst, C., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., & Livingston, B. (2012). The odd one out: How newcomers who are different become adjusted. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization (pp. 115–138). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Kallio, J., Blomberg, H., & Kroll, C. (2013). Social workers’ attitudes towards the unemployed in the Nordic countries. International Journal of Social Welfare, 22(2), 219–229. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2012.00891.x

- Keiser, L. R. (2010). Understanding street-level bureaucrats’ decision making: Determining eligibility in the social security disability program. Public Administration Review, 70(2), 247–257. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02131.x

- Keulemans, S., & Groeneveld, S. (2019). Supervisory leadership at the frontlines: Street-level discretion, supervisor influence, and street-level bureaucrats’ attitude towards clients. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. Advance online publication. doi:10.1093/jopart/muz019

- Keulemans, S., & Van de Walle, S. (2018). Understanding street-level bureaucrats’ attitude towards clients: Towards a measurement instrument. Public Policy and Administration. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0952076718789749

- Klimoski, R., & Mohammed, S. (1994). Team mental model: Construct or metaphor? Journal of Management, 20(2), 403–437. doi:10.1177/014920639402000206

- Kroeger, N. (1975). Bureaucracy, social exchange, and benefits received in a public assistance agency. Social Problems, 23(2), 182–196. doi:10.2307/799655

- Lahlou, S. (1996). The propagation of social representations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 26(2), 157–175. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1996.tb00527.x

- Levi, D. (2011). Group dynamics for teams (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service (30th anniversary expanded ed.). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Maio, G. R., & Haddock, G. (2015). The psychology of attitudes and attitude change (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Maroulis, S. (2017). The role of social network structure in street-level innovation. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(4), 419–430. doi:10.1177/0275074015611745

- Maynard-Moody, S. W., & Musheno, M. C. (2003). Cops, teachers, counselors: Stories from the front lines of public service. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Miller, E. J., & Rice, A. K. (1967). Systems of organizations: The control of task and sentient boundaries. London, UK: Tavistock.

- Moreland, R. L., & Levine, J. M. (2006). Socialization in organizations and work groups. In R. L. Moreland & J. M. Levine (Eds.), Small groups. Key readings (pp. 469–498). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Morrison, E. W. (1993). Longitudinal study of the effects of information seeking on newcomer socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 173–183. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.173

- Moscovici, S. (1988). Notes toward a description of social representations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(3), 211–250. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420180303

- Moyson, S., Raaphorst, N., Groeneveld, S., & Van de Walle, S. (2018). Organizational socialization in public administration research: A systematic review and directions for future research. The American Review of Public Administration, 48(6), 610–627. doi:10.1177/0275074017696160

- Oberfield, Z. (2014). Becoming bureaucrats. Socialization at the front Lines of government service. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Oberfield, Z. (2019). Change and stability in public workforce development: A 10-year study of new officers in an urban police department. Public Management Review, 21(12), 1753. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1571276

- Ottati, V., Edwards, J., & Krumdick, N. D. (2005). Attitude theory and research: Intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary connections. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 707–742). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408

- Raaphorst, N. J. (2017). Uncertainty in bureaucracy: Toward a sociological understanding of frontline decision making (Doctoral dissertation). Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

- Sandfort, J. R. (2000). Moving beyond discretion and outcomes: Examining public management from the front lines of the welfare system. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(4), 729–756. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024289

- Siciliano, M. D. (2017). Professional networks and street-level performance: How public school teachers’ advice networks influence student performance. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(1), 79–101. doi:10.1177/0275074015577110

- Simon, H. A. (1997). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organizations (4th ed.). New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. doi:10.2307/2695870

- Stone, C. N. (1981). Attitudinal tendencies among officials. In C. T. Goodsell (Ed.), The public encounter: Where state and citizen meet (pp. 43–68). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). Social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

- Turner, J. C., & Haslam, S. A. (2001). Social identity, organizations, and leadership. In M. E. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Advances in theory and research (pp. 25–66). New York, NY: Erlbaum.

- Van Maanen, J. E., & Schein, E. H. (1979). Toward a theory of organizational socialization. In B. M. Staw (Ed.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 209–264). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Wanberg, C. R. (2012). Facilitating organizational socialization: An introduction. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 3–7). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Wilson, J. Q. (1989). Bureaucracy: What government agencies do and why they do it. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Wright, B. M., & Barker, J. R. (2000). Assessing concertive control in the term environment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 345–361. doi:10.1348/096317900167065

- Zacka, B. (2017). When the state meets the street: Public service and moral agency. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.